Abstract

Purpose

This study investigates long-term consequences of individual migration experience on later life health, specifically self-rated health and functional difficulty.

Design/methodology/approach

The study uses multiple community-, household-, and individual-level data sets from the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS) in Nepal. The CVFS selected a systematic probability sample of 151 neighborhoods in Western Chitwan and collected information on all households and individuals residing in the selected sample neighborhoods. This study uses data from multiple surveys featuring detailed migration histories of 1,373 older adults, and information on their health outcomes, households, and communities.

Findings

Results of the multi-level multivariate analysis show a negative association between number of years of migration experience and self-rated health, and a positive association between migration and functional difficulty. These findings suggest a negative relationship between migration experience and later life health.

Research limitations/implications

Although we collected health outcome measures after the measurement of explanatory and control measures—a unique strength of this study—we were unable to control for baseline health outcomes. Also, due to the lack of time-varying measures of household socioeconomic status in the survey, this investigation was unable to control for measures associated with the economic prosperity hypothesis. Future research is necessary to develop panel data with appropriately timed measures.

Practical implications

The findings provide important insights that may help shape individual's and their family's migration decisions.

Originality/value

This research provides important insight to individuals lured by potential short-term economic prospects in destination places, as well as to scholars and policy makers from migrant-sending settings that are grappling with skyrocketing medical expenses, rapid population aging, and old age security services.

Keywords: Migration, Later life health, Nepal

1. Introduction

This study1investigates the long-term consequences of migration on later life health, a pressing issue globally. This study is important because world population is more mobile today than at any other point in human history. Population mobility not only constitutes visitors making short trips for leisure and vacation, but also migrants who live for extended periods of time within and outside of their home country. Based on UN estimates, 258 million people (3.4 percent of the world population) were international migrants in 2017. Asians were among the largest group of international migrants (40.7 million in 2017) living outside their home country (United Nations, 2017). Additionally, domestic migrants constitute a significant proportion of the world's population. This unprecedented demographic phenomenon has received considerable attention both in the academic and policy arenas, resulting in a large number of studies, including some very prominent ones around the world. These studies have made tremendous advances in our understanding of the predictors and consequences of migration for communities, households, and families left behind, and for the migrants themselves.

On the other hand, it is well understood that the elderly population is increasing globally, particularly in Asia. In South Asia, the elderly population aged 65 and over is expected to rise by 393 percent—from 67,758,000 in 2000 to 334,280,000 by 2050 (Mason, 2006). In Nepal, the proportion of the elderly population is expected to continue rising, transitioning to an “aging society” by 2028 and to an “aged society” by 2054 (Amin et al., 2017). Moreover, as Nepal is also experiencing massive outmigration of young family members, the health concerns of the elderly population, who, until recently, have been primarily cared for by families, have been a major challenge to policy makers.

Given the potential for important consequences of migration on health, migration and health has been a significant element of scientific inquiry throughout the history of migration research (Ahmed, 2000; Cresswell, 2000; Kraut, 1995). Previous research on migration and health has primarily focused on migrants as “harbingers of disease” (Ahmed, 2000; Cresswell, 2000; Kraut, 1995; Dasgupta and Menzies, 2005; European Academics Science Advisory Council 2007). This trend continues with the study of a recent episode of the West Nile virus outbreak (Chevalier et al., 2013). On the other hand, other scholars have focused on health inequality. This line of research, also referred to as the healthy migrant hypothesis or Salmon bias, suggests that migrants are healthier (have a lower mortality rate) than their counterparts in destination societies (Kibele et al., 2008; Markides and Eschbach, 2005; Razum et al., 1998; Singh and Siahpush, 2001). Some scholars have attributed this finding to “selectivity of migration” (Kibele et al., 2008), while other scholars have focused on socio-cultural factors (Singh and Siahpush, 2001; Abraído-Lanza et al., 1999; Palloni et al., 2004), or even artifacts of data (Razum et al., 2000; Weitoft et al., 1999).

Despite the fact that migration experiences are likely to have important psychological and physical health consequences, little attention has been given to the impact of migratory behavior on the subsequent health of migrants themselves. This paper takes a step forward by comparing migrants with non-migrants.

We take advantage of the natural social laboratory setting, study design, and detailed measurement of the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS), to investigate the long-term influence of migration experience on health. CVFS, a panel study of communities, households, and individuals, features migration histories collected retrospectively using a Life History Calendar (LHC) and prospectively in household registration systems. Thus, CVFS provides uniquely detailed measures of migration experiences (Axinn et al., 2012; Axinn et al., 1999). The individual migration histories are supplemented with measures of self-rated health and functional difficulty, along with repeated panel measures of household economy and consumption. Additionally, the CVFS collected measures of community change using a Neighborhood History Calendar (NHC). Together, these measures provide a unique resource and opportunity to advance our understanding of the long-term consequences of migration, one of the most rapidly growing demographic phenomena of the century.

The findings of this study will be of great interest to a wide range of audiences. First, the findings on long-term consequences of migration will be of utmost importance to individuals from poor agricultural migrant-sending settings lured by glorifying stories of the economic prospects in urbanized areas or industrialized countries. Second, the findings from the study will be equally important to policy makers grappling with skyrocketing medical expenses, rapid population aging, and old age security services coupled with eroding historical family norms, values, and elderly care system. Finally, the findings of this study will be of great interest to scholars and will advance our understanding of the consequences of migration for later life health. Additionally, this study will encourage new studies designed to address the data limitations the scientific community continues to face, particularly the lack of pre-migration measures of health.

1.1. Migration and health: literature review and theoretical framework

Migration is perhaps one of the most investigated subjects and is studied both substantively and methodologically across many disciplines, including sociology, economics, political science, and epidemiology. Contemporary scholars have developed and extensively employed several theoretical and conceptual frameworks to understand migration (Massey et al., 1993). These frameworks have been highly successful in advancing our understanding of (1) predictors of migratory behaviors, (2) economic consequences to sending communities through cash remittances and loss of labor, (3) short-term health consequences such as transmission of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV/AIDS, (4) social consequences for left-behind women and children, and recently, (5) what is called social remittances (change in migrants’ values, beliefs, and skills). More recently, given the potential role of mobile populations in public health, migration research has focused attention on the interconnection between migration and health.

One line of research, which examines the link between migration and the spread of communicable diseases, has characterized migrants as “harbingers of disease” (Ahmed, 2000; Cresswell, 2000; Kraut, 1995), and is perhaps the most obvious way the public, policy makers, and academia link migration to health (Dasgupta and Menzies, 2005).

Another line of research, commonly known as the healthy migrant hypothesis or Salmon bias, suggests that migrants are healthier than their counterparts in the sending communities or those in the receiving communities (Abraído-Lanza et al., 1999; Bentham, 1982; Boyle et al., 2004; Lassetter and Callister, 2008; Lu, 2010; Marmot et al., 1984). Researchers have documented evidence to support this hypothesis from several migrant-receiving settings in Europe and the United States, where mortality rates among Hispanics are lower than those for the non-Hispanic white population (Kibele et al., 2008; Markides and Eschbach, 2005; Razum et al., 1998; Singh and Siahpush, 2001).

While the salmon bias hypothesis still predominates the field, another stream of research focuses on health inequality. These scholars focus on socio-cultural factors (Singh and Siahpush, 2001; Abraído-Lanza et al., 1999; Palloni et al., 2004) or even artifacts of data (Razum et al., 2000; Weitoft et al., 1999).

Another direction of research, also known as the economic prosperity hypothesis, suggests that the wage difference between the origin and destination substantially increases migrants’ earning potential and actual earnings (Stark and Taylor, 1989; Stark et al., 1986; Todaro, 1980; Zhao, 1999). This increased earning will then result in higher living standards, including more nutritious food and better medical care, helping the migrant to remain healthy in older age. Both the healthy migrant hypothesis and the economic prosperity hypothesis predict a positive relationship between migration experience and later life health outcomes.

However, we argue that both these hypotheses overstate the benefits of migration and overlook the potential hardship, deprivation, and abuse migrants may experience and underestimate the long-term consequences of migration on later life health. Indeed, we argue that the consequences of the hardship, deprivation, and abuse are so strong that the positive effects of early life health status and economic prosperity may be diminished by the effects of hardship, poor working conditions, deprivation, and abuse, resulting in a net negative effect on later life health. We believe that migration may negatively influence later life health through two potential mechanisms: (a) structural and (b) social psychological.

For our analysis, we developed a theoretical framework for our investigation of long-term consequences of migration on later life health. We argue that individual migration experience is likely to have important consequences on later life health, potentially through structural and social psychological mechanisms. Our theoretical framework draws heavily on the extensive literature on predictors of migratory behavior, as well as the short-term economic and social consequences, and long-term health outcomes of migration. Below we describe potential mechanisms through which individuals’ early life migration experiences are likely to influence later life health.

1.1.1. Structural mechanisms

Migration leads to a change in geographical location usually different from what the migrants are used to. This may expose migrants to physical and environmental conditions including topography, temperature, and working conditions to which adaptation is difficult. Additionally, most migrants are employed in occupations characterized by the ‘three Ds’: difficult, dirty, and dangerous (Joshi et al., 2011; Seddon et al., 2002; Taran, 2001; Thieme and Wyss, 2005). Exposure to adverse physical and environmental conditions coupled with little experience and few resources to facilitate adaptation, is likely to result in not only higher mortality rates, but also severe long-term health problems of the survivor. Thus, migrants usually go through a difficult process of geophysical and environmental adaptation, which we call a structural adaptation argument.

Additionally, migrants at their destination are typically deprived of several basic services and human rights and face discrimination. Migrants usually endure poor living conditions (crowding) and occupational environments (Joshi et al., 2011; Taran, 2001; Holmes, 2006), and are deprived of rights to basic services such as primary/emergency health care (Leclere et al., 1994; Lucas et al., 2003). Additionally, they are deprived of basic human rights such as the right to free movement and use of public services (Joshi et al., 2011; Seddon et al., 2002; Taran, 2001; Thieme and Wyss, 2005). These experiences may lead to negative health consequences in the long term.

1.1.2. Social psychological mechanisms

Stressful experiences and poor social relationships can increase the likelihood of developing physical and mental disorders and decrease resiliency or delay recovery (Aneshensel, 1992; Barnett et al., 1997; Bigbee, 1990; Collins et al., 1998; Ge et al., 1994; House et al., 1988; Lantz et al., 2005; Segerstrom and Miller, 2004; Selye, 1936; Selye, 1955). In general, both pre- and post-departure experiences are likely to produce significant anxiety and stress. The separation from family and loved ones, change in physical location, and exposure to new social and geophysical environmental conditions are all conceptualized as stressful experiences. Stressful life events are known to worsen health outcomes, especially in domains closely related to stress, such as substance use and mental health. Stressful life events increase substance use in the short term and substance dependence in the long term; stressful life events also increase post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), intermittent explosive disorder (IED), and panic disorder (PD) in the long term (Aseltine and Gore, 2000; Bruns and Geist, 1984; Kessler et al., 1995; Paykel et al., 1969; Piazza and Le Moal, 1998; Piazza and Le Moal, 1996). The Foreign Employment Promotion Board (FEPB) has reported many Nepalese migrant workers have committed suicide in destination countries (Shrestha, 2016). Shrestha (Shrestha, 2016) also reported another study by Pourakhi Nepal and SaMi HELVETAS that surveyed Nepali female migrants and found nearly three-fourths of the 151 female returnee migrants from various countries showed signs of depression. Migrants have also reported poor working conditions, abuse, and stress (Joshi et al., 2011) .

The literature repeatedly identifies separation from family, exposure to different geophysical and occupational environments, and discriminatory and abusive/hostile social environments at the destination (Hennig, 2014) as the most likely factors to produce significant personal stress.

Thus, we expect that compared to non-migrants or those who have short migration experiences, migrants who have longer migration experiences are more likely to self-rate their health poor and experience greater functional difficulties in later life.

1.2. Nepal and its historical background of migration

Nepal has a long history of migration through trade routes between the Himalayan regions and the Indian plains. While there was continuous low-level internal mobility throughout history, internal migration started increasing in the 1950s when the country's rapidly growing population in the hills experienced frequent and widespread food shortages resulting from devastating natural disasters such as floods and landslides (Kandel, 1996). As the cultivation of steeper slopes became less productive and infrastructure and economic opportunities in the developing Terai region (Southern plains) and urban areas flourished, migration from the mountains and hill areas to the Terai region and urban areas (rural to urban migration) became quite common. As a result of these pull factors, population in both urban centers (district headquarters and industrial areas) and the Terai region grew substantially.

International labor migration, on the other hand, formally began in 1815 CE with the recruitment of Nepalese youth in the British Brigade of Gurkha—units of the British Army that were composed of Nepalese soldiers (Rathaur, 2001; Gurung, 1983). However, it was not until the government of Nepal promulgated the Foreign Employment Act of 1985 that international labor migration to destinations other than India became a viable option for Nepalese migrants. The 1985 Foreign Employment Act licensed non-governmental institutions to export Nepalese workers abroad and legitimized certain labor contracting organizations. This ignited large streams of international migration to diverse destinations, a change from earlier international migration which had been primarily restricted to India (Thieme and Wyss, 2005; Kollmair et al., 2006).

Nepal has become one of the largest migrant-sending countries. Because of the historical and more recent migration experiences of the Nepalese, Nepal provides an ideal setting to study the influence of migration on later life health.

1.3. Study setting: the Chitwan Valley

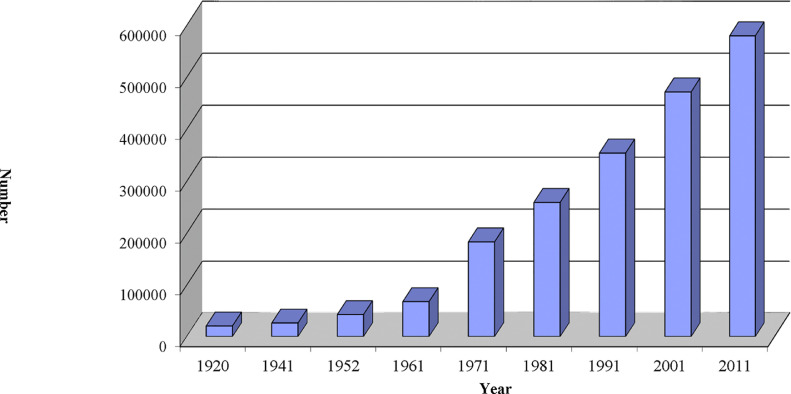

The Chitwan Valley lies in south central Nepal. In 1955, the government opened this valley for settlement and distributed land parcels to migrants from other parts of the country. Until the 1970s, the valley was isolated from the rest of the country. However, with the construction of all-weather roads in the 1970s, the valley became connected to the rest of the country and turned into one of the business hubs of Nepal (Shivakoti et al., 1999). This transformation, from an isolated valley to a busy business center with a massive expansion of community services, had tremendous impact on the daily lives of communities and individuals (Axinn and Yabiku, 2001). The population of the valley grew by more than fivefold—a once sparsely populated valley turned into a highly populated area (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Population in Chitwan Over Time. Sources of data for Figure 1: (His-Majesty's Government 1973, Sharma and Subedy, 1994, Central Bureau of Statistics 1995, Central Bureau of Statistics 2001, Central Bureau of Statistics 2011).

The fast-growing youth population resulted in a surplus labor force with exposure to schooling and international media that the country's slow-growing economy could hardly keep economically engaged in Nepal. As a result, the valley experienced unprecedented international labor out-migration, turning what was once a migrant-receiving valley into a migrant-sending valley.

2. Material and methods

This study uses multiple data sets from the Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS), a multilevel, mixed method panel study of communities, households, and individuals.

The CVFS selected a systematic probability sample of 151 neighborhoods in Western Chitwan and defined a neighborhood as a geographic cluster of five to fifteen households. Once a neighborhood was selected, all individuals aged 15–59 residing in the sampled neighborhood were interviewed. If any of the respondents had a spouse living elsewhere, that spouse was interviewed as well. A total of 4446 individuals were interviewed with a 97% response rate. This study provides rich retrospective measurement of the occurrence, timing, and characteristics of individual life events, including migration histories, collected using an LHC and accompanying structured questionnaire. The LHC method provides more accurate retrospective measurements of life events than alternative measurement techniques (Belli, 1998; Freedman et al., 1988). Moreover, the LHC used in the CVFS was specifically designed to use local events to help respondents recall the timing of personal events and to allow respondents to report their recall of marital events in a manner most consistent with local practices (Axinn et al., 1999). In addition, in 1996 the CVFS also collected detailed histories of community change since 1954 (1954–1996) and updated these histories in 2005 (1997–2005), using the NHC method (Axinn et al., 1997).

After the individual survey, the CVFS launched a Monthly Demographic Household Registry to track the individuals and their households over time and collect survey data on migration, marriage, childbearing, and mortality in their households. Beginning in February of 1997, interviewers visited each household monthly to update demographic events such as births, deaths, marriages, divorces, contraceptive use, pregnancies, and changes in living arrangements. All residents of these 1580 households were followed over time, including households and individuals from those households who moved out of the study area. This means that the prospective panel data were maintained for all those who were interviewed in the original study, regardless of their migration behavior.

In 2006, the CVFS collected detailed information about health and wellbeing from all elderly residents in 151 of the sample neighborhoods. We defined elderly as aged 45 and older, which is a lower threshold than that typically used in Western studies of aging. However, as in many other poor agricultural settings, many individuals in Chitwan were already experiencing physical and mental signs of aging by the age of 45. Work in Chitwan is generally very physically demanding and most people in their 40s have been participating in hard, physical labor for over 30 years. As a result, many people suffer debilitating physical impairments from relatively minor ailments. Therefore, we used age 45 as an appropriate minimum age for elderly classification. Using a younger age boundary to define our sample of interest was further supported by the fact that life expectancy in Nepal was only 62 years in 2006.

The 2006 elderly health and wellbeing survey resulted in a sample of 1373 individuals who were interviewed in the 1996 individual survey, followed in the household registry, and who were interviewed in the 2006 elderly health and wellbeing survey.

2.1. Measures

We focused on self-reported health and functional difficulty as our outcome measures. Our measures of self-reported health and functional difficulty come from responses to individual interviews in the 2006 elderly health and wellbeing survey.

2.1.1. Self-reported health

As in other major international surveys, we measured self-reported health by asking “Overall, would you say that your health is excellent, good, fair, or poor?” Responses were coded as a continuous measures where 1=poor; 2=fair; 3=good and 4=excellent. This measure is widely used to measure health inequalities in developed as well as developing countries (Balabanova and McKee, 2002; Carlson, 2001; Idler and Benyamini, 1997; Lindstrom et al., 2001; Rogers et al., 2000; Undén and Elofsson, 2006), and is considered a strong and independent predictor of mortality (Idler and Benyamini, 1997; Idler, 2003).

2.1.2. Functional difficulty

Our measure of functional difficulty comes from responses to a series of questions in the 2006 elderly health and wellbeing individual interview. We created an index of functional difficulty using eight items that measured activities of daily living (ADL). These items were dichotomously measured by asking whether a respondent has difficulty in (1) stooping, kneeling, or crouching; (2) finding a pin dropped on the ground; (3) getting in and out of bed without help; (4) bathing without help; (5) moving a 30 kg rice bag from one place to another; (6) difficulty getting water from a well; (7) continuously walking for one hour; and (8) doing farm activities such as plowing, hoeing, or planting. The ADL index was created by summing up the yes (=1) or no (=0) responses to these eight items, resulting in an index that ranges from 0 to 8. We use this index as a continuous measure in our analyses.

2.1.3. Migration

We used the number of years the respondent lived outside their birthplace as our measure of migration experience.2 As described above, the measure of migration experience was estimated by combining information from the 1996 LHC (respondent's birth to 1996) and the Household Registry system (1997–2006). On average, our respondents reported 30 years of migration experience. However, slightly over 16 percent of them reported no migration outside of their birthplace (results not shown).

2.2. Other factors associated with migration and later life health

Evidence indicates that a number of respondent's background characteristics and experiences (other than migration) as well as household and community characteristics may have important independent influences on later life health (Lu, 2010; Elo and Preston, 1992; Hayward and Gorman, 2004). Our models of migration and health also include measures of respondents’ backgrounds (birth cohort, ethnicity, gender, marital status, education, and employment); household wealth (land holding), and community characteristics (both during childhood and in the contemporary context) to help ensure the associations observed were not a product of these other factors.

2.2.1. Age

Population health and mortality is closely associated with age (Elo and Preston, 1992; Hayward and Gorman, 2004), and therefore ignoring age in an analysis of population health and mortality would introduce a major bias (Hummer et al., 1998). Intuitively, elderly people are more likely to report severity in terms of both of these health statuses: self-rated health and functional disability. Therefore, we grouped ages into three categories: age in years between 45 and 54, 55 and 64, and 65 years and over. We treated the oldest cohort—ages 65 and over—as the reference group.

2.2.2. Gender

Both morbidity and mortality are related to gender. Patterns of death between men and women vary due to different biological functions such as childbearing, adapting risky behaviors such as smoking and alcohol use, occupational hazards, etc. Other evidence suggests that women may be protected from a number of infectious and degenerative diseases because of the presence of reproductive physiology, protective hormones, and certain X-linked genes (Hummer et al., 1998; Gage, 1994). Evidence suggests that although women live longer than men, there is a paradox in self-reported health: women report worse self-rated health than their male counterparts (Case and Paxson, 2005). Due to the complex interactions between gender and health, we also controlled for gender in the analyses.

2.2.3. Marital status

Marital experiences have also been shown to affect health. The marital protection argument suggests that marriage protects individuals by encouraging healthy behaviors, reducing risky behaviors, and increasing compliance with medical treatments (Hummer et al., 1998; Gove, 1973; Trovato and Lauris, 1989). Another well-known argument theorizing the relationship between marriage and health is social integration (Durkheim, 1897). This argument hypothesizes that marriage is social integration that leads to social support, thus influencing individual health status. On the other hand, the marital selectivity argument focuses on morbidity and mortality difference in terms of marriage of healthy individuals (Lillard and Panis, 1996). Because marital status has been shown to affect health in various ways, we controlled for marital status, which we measured dichotomously as currently married (=1) or not (=0).

2.2.4. Education

Education has been shown to influence morbidity and mortality through altered health behaviors and indirectly through its effect on income and occupation (Ross and Wu, 1995; Elo and Preston, 1997). Education provides knowledge, skills, and information as well as increased access to health care, employment, and income. We controlled for education, using a continuous measure of the number of years of schooling.

2.2.5. Employment

Employment is another measure that may influence individual health status. Evidence suggests that employment has a beneficial effect on health and mortality through increased income or social relations with peers, as well as other benefits (Hummer et al., 1998; Ross and Mirowsky, 1995). Thus, we controlled for employment, using a continuous measure of the total number of years of non-family work.

2.2.6. Ethnicity

Nepali society consists of many ethnic groups (Bista, 1972) that are likely to have significantly different educational experiences and marital relationships. Scholars have often categorized these ethnicities into five major groups for analytical purposes: Brahmin/Chhetri (high caste Hindus), Dalit (low caste Hindus), Newar, Hill Janajati (Hill indigenous), and Terai Janajati (Terai indigenous) (Axinn and Yabiku, 2001). We coded individuals as “1″ if they are members of a specific group and “0″ if not, and treated Brahmin/Chhetri as the reference group.

2.2.7. Household land holding

Household wealth is closely linked with individual health and mortality. Land is the most important production resource in an agricultural setting. Therefore, private ownership of land is an important determinant of wealth (Datta, 1998; Findley, 1987; de Janvry, 1981). Thus, land ownership may be considered a proxy measure of economic resources. Moreover, access to land is one of the important determinants of food security or insecurity in developing countries, thus directly influencing individual health status. To take into account the economic prosperity hypothesis, we controlled for household land holding, which we measured as the total of bari and khet land cultivated by a farm household during the survey year. We measured land in the local units, bigha and kattha (1 hectare=1.5 bigha=30 kattha).

2.2.8. Childhood community context

Childhood community context has a strong influence on individual mortality, suggesting that access to community services such as schools and health services during childhood may reduce mortality (Hayward and Gorman, 2004; Wickrama and Noh, 2010). The CVFS collected information about access to schools, health services, employment, and bus services during the respondent's childhood through individual interviews. Respondents were asked, “Was there a school within a one-hour walk from your home at any time before you were 12 years old?” A positive response was coded as “1” and a negative responses was coded “0.” We collected information on health services, employment centers, bus stops and markets by asking similar questions. We created an index of the individual's childhood community context by summing up the responses, resulting in a continuous measure ranging from 0 to 4.

2.2.9. Access to contemporary community services

Contemporary access to community services such as schools and health services may influence individual health status. The CVFS measured access to community services within a given year as the time to walk (in minutes) to the nearest service (school or health service) from the neighborhood. Responses were coded as 1 if available within a 15 min walk in that year and 0 otherwise. We then added the number of years the service was available within a 15 min walk, resulting in two continuous measures of the total number of years a health service was available within a 15 min walk, and the total number of years a school was available within a 15 min walk. In the absence of baseline measures of individual health status, we use both childhood community context and access to contemporary community services as proxy measures of individual health (to take into account the migrant selectivity or healthy migrant hypothesis). Access to community services in childhood as well as access to contemporary community services may predict better individual later life health outcomes.

2.2.10. Distance to urban center

Proximity to an urban center is associated with information and opportunity for both migration and health, and therefore highly likely to influence migration experiences, health, and the association between the two. Narayangarh/Bharatpur is the largest urban center of the Chitwan Valley. Therefore, we included distance to Narayangarh/Bharatpur from the respondent's neighborhood (in miles) as a control.

2.3. Analytic strategy

We used a multi-step analytical strategy to estimate the relationship between migration experience and health status (self-reported health status and functional difficulty). First, we calculated the univariate distribution of all the measures used in the analysis. Next, multivariate models were estimated to examine the relationships between migration experience and health status, adjusting for the effects of other controls known to confound these relationships. Because we used continuous outcome measures of self-reported health status and functional difficulty, we employed the multi-level OLS regression as a multivariate tool to estimate our models of migration and later life health.

3. Results

3.1. Univariate analysis

Table 1 presents the coding, means or percent, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum values for all measures used in the analyses. As shown in the top panel of Table 1, the average self-rated health score of 2.13 suggests that, on average, respondents reported their health status as fair. Specifically, about 19% reported their health status as poor, 60% reported their health status as fair, about 10%% reported their health status as good, and 11% reported their health status as excellent.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Measures (N = 1373).

| Measures | Mean/Percent | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Measures | ||||

| Self-reported health (1=poor 4=excellent) | 2.13 | 0.39 | 1 | 4 |

| Poor | 19% | |||

| Fair | 60% | |||

| Good | 10% | |||

| Excellent | 11% | |||

| Index of functional difficulty (0=no functional difficulty to 8=8 functional difficulties) | 3.55 | 2.18 | 0 | 8 |

| Explanatory Measures | ||||

| Migration (number of years lived outside birthplace) | 29.32 | 16.44 | 0 | 65 |

| Controls | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Age cohort 1 (Ref: 65 and above) | 11% | 0.32 | 0 | 1 |

| Age cohort 2 (55–64) | 51% | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Age cohort 3 (45–54) | 37% | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Gender (female=1) | 53% | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Marital status (currently married=1) | 88% | 0.33 | 0 | 1 |

| Education (number of years of schooling) | 2.76 | 4.68 | 0 | 26 |

| Employment (number of years of non-family work) | 12.76 | 12.91 | 0 | 50 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Brahmin/Chhetri | 47% | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Dalit | 10% | 0.30 | 0 | 1 |

| Hill Janajati | 17% | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Newar | 7% | 0.26 | 0 | 1 |

| Terai Janajati | 19% | 0.39 | 0 | 1 |

| Household land holding (kattha) | 18.76 | 26.83 | 0 | 200 |

| Community-level Controls | ||||

| Childhood community context | 1.51 | 1.42 | 0 | 4 |

| Access to contemporary community services | ||||

| School within 15 min walk (number of years) | 8.82 | 6.45 | 0 | 30 |

| Health services within 15 min walk (number of years) | 19.83 | 17.73 | 0 | 90 |

| Distance to urban center (Miles) | 8.62 | 4.01 | .02 | 17.70 |

The index of functional difficulty ranges from 0 to 8 (0=no functional difficulty to 8 = 8 functional difficulties) with a mean of 3.55, which suggests that, on average, respondents experienced slightly over three functional difficulties. While only about 10% of the respondents reported no functional difficulty, about a quarter of them reported functional difficulty in doing 6 or more daily activities. In terms of migration experiences, on average, respondents lived over 29 years outside of their birth place, with a range of 0–65 years.

The middle panel shows descriptive statistics of respondents’ experiences and background. Of all respondents in the sample, 53% are female, 88% are currently married, 11% are aged 65 years or older, 51% are 55–64 years old, and the remaining 37% are 45–54 years old. Almost half of the sample (47%) are of Bhramin/Chhetri ethnicity, followed by 19% Terai Janajati, 17% Hill Janajati, 10% Dalit, and 7% Newar. Our sample has a mean of 2.76 years of schooling and 12.76 years of non-family work.

The bottom panel shows descriptive statistics for household and community context. On average, households in the sample owned 18.76 kattha (1 kathha=3645 sq. ft.) of land. The mean of 1.51 using the 0–4 scale of childhood community context suggests that respondents lived within one hour walk of 1.5 services before they were age 12. In terms of contemporary access to community services, on average, respondents lived 8.82 years within a 15 min walk from a school and 19.83 years within a 15 min walk from a health service. Finally, the distance to urban center from the respondent's neighborhood varied from 0.02 to 17.70 miles with a mean of 8.62 miles.

3.2. Multivariate analysis of migration experience and self-reported health

The results of our multivariate models investigating the association between migration experience and self-rated health suggest that number of migration years is negatively associated with later life self-rated health. The regression coefficient of −0.004 for migration experience suggests that on a 4-point self-rated health scale, a one-year increase in number of migration years reduces self-rated health by 0.004 points. This means, on average, a respondent who lived 10 years away from their birthplace is likely to rate their health 0.04 points lower than a respondent who never lived away from their birthplace. Although the magnitude of the effect seems small, the consequences of this could be more severe than one might think because respondents were constrained to rating their health on a very narrow scale (1–4 points). Moreover, this effect is robust against a wide range of other factors known to influence the relationship between migration and health (Tables 2)

Table 2.

Coefficients from Multilevel OLS Regression to Estimate the Relationships between Migration Experience and Self-reported Health (N = 1373).

| Measures | Self-rated Health |

|---|---|

| Migration Experience | |

| Number of years lived outside birthplace | −0.004* (1.95) |

| Controls | |

| Age | |

| Age cohort 1 (Ref: 65 and above) | – |

| Age cohort 2 (55–64) | 0.002 (0.02) |

| Age cohort 3 (45–54) | −0.033 (0.43) |

| Gender (female=1) | −0.139** (2.58) |

| Marital status (currently married=1) | −0.063 (0.88) |

| Number of years of schooling | 0.016** (2.76) |

| Number of years of non-family work | 0.001 (0.71) |

| Ethnicity (Brahmin/Chhetri, reference group) | – |

| Dalit | −0.072 (0.83) |

| Hill Janajati | 0.046 (0.67) |

| Newar | −0.085 (0.90) |

| Terai Janajati | −0.113 (1.19) |

| Household land holding (kattha) | 0.007 (1.61) |

| Childhood community context | 0.023 (1.19) |

| School within 15 min walk | 0.007+ (1.61) |

| Health service within 15 min walk | −0.007*** (3.96) |

| Distance to urban center | 0.017** (2.36) |

| Intercept | 2.237 ***(16.02) |

| -2 Res Log Likelihood | 3478.8 |

| ICC | 0.027 |

t-statistic *** = p<.001; ** = p<.01; * = p<.05; + = <0.10. Figures in parenthesis indicate t-values.

Additionally, the regression coefficient of −0.139 for females suggests that on a 4-point self-rated health scale, women, compared to men, report worse self-rated health by 0.139 points. Education, on the other hand, displayed a positive association with self-rated health; each year of schooling increased self-rated health by 0.016 points. The regression coefficient of −0.007 for health services suggests that on a 4-point self-rated health scale a one-year increase in the number of years living within a 15 min walk from a health service reduces self-rated health by 0.007 points. Finally, the regression coefficient of 0.017 for distance to urban center suggests that on a 4-point self-rated health scale, one mile increase in distance to urban center increases self-rated health by 0.017 points. We did not find evidence for a significant association between age, marital status, number of years of non-family work, ethnicity, household land holding, childhood community context, or schools within a 15 min walk and self-rated health.

3.3. Migration experience and functional difficulty

Similar to the self-rated health results, the findings from our multivariate model of migration and functional difficulty suggest a positive association between migration and greater functional difficulty. The regression coefficient of 0.013 for migration experience, on a 0–8 point functional difficulty scale, suggests that a one year increase in number of years of migration experience increases functional difficulty by 0.013 points. Moreover, this effect is independent of other factors known to influence later life health (Tables 3).

Table 3.

Coefficients from multilevel OLS regression to estimate the relationships between migration experience and functional difficulty (N = 1373).

| Measures | Functional Difficulty |

|---|---|

| Migration Experience | |

| Number of years lived outside birthplace | 0.013** (2.63) |

| Controls | |

| Age | |

| Age cohort 1 (Ref: 65 and above) | – |

| Age cohort 2 (55–64) | −0.609** (3.02) |

| Age cohort 3 (45–54) | −0.291 (1.52) |

| Gender (female=1) | 1.096*** (8.31) |

| Marital status (currently married=1) | −0.049 (0.28) |

| Number of years of schooling | −0.043** (2.99) |

| Number of years of non-family work | −0.001 (0.21) |

| Ethnicity (Brahmin/Chhetri, reference group) | – |

| Dalit | 0.385+ (1.81) |

| Hill Janajati | −0.474** (2.75) |

| Newar | −0.184 (0.78) |

| Terai Janajati | 0.442+ (1.88) |

| Household land holding (kattha) | −0.005* (2.00) |

| Childhood community context | −0.090* (2.04) |

| School within 15 min walk | 0.015 (1.50) |

| Health service within 15 min walk | −0.004 (0.93) |

| Distance to urban center | 0.004 (0.17) |

| Intercept | 3.279 *** (9.51) |

| -2 Res Log Likelihood | 5911.5 |

| ICC | 0.031 |

t-statistic *** = p<.001; ** = p<.01; * = p<.05; + = <0.10 Figures in parenthesis indicate t-values.

The regression coefficient of 1.096 for gender suggests that on a 0–8 functional difficulty scale, women reported increased functional difficulty compared to men by 1.096 points. More education, on the other hand, was negatively associated with functional difficulty. Each additional year of schooling decreased functional difficulty by 0.043 points. The regression coefficient of −0.474 for Hill Janajati suggests that on a 0–8 point functional difficulty scale, compared to Brahmin and Chhetri, Hill Janajati are less likely to report functional difficulty by 0.474 points. In terms of household wealth, individuals residing in households with larger land holdings were likely to report fewer functional difficulties. Likewise the regression coefficient −0.090 for childhood community context suggests that one point increase in childhood community context decreased functional difficulty by 0.09 points. Our results do not show evidence for a significant association between marital status, number of years of non-family work, schools or health services within a 15 min walk, or distance to urban center and functional difficulty.

4. Discussion

The relationship between migration and health has been an important element of scientific inquiry throughout the history of migration research. Previous studies on migration and health focused on the transmission of communicable diseases. This line of research suggests migrants are a source of transmission of communicable diseases. However, more recently, health consequences of migrants at their place of origin or destination have received attention in both academic and policy arenas. One group of scholars examining migrant health has suggested that migrants are healthier than non-migrants or are healthier than the population at the destination (healthy migrant hypothesis or salmon bias). Another line of research focuses on the wage difference between the place of origin and destination, which substantially increases migrants’ actual earnings. This research suggests that increased earnings allow higher living standards, including access to more nutritious food and better medical care, which helps migrants remain healthy in older age (economic prosperity hypothesis).

More recently, structural adaptation and social psychological mechanisms have received attention. According to the structural adaptation argument, migrants usually go through a difficult process of geophysical and environmental adaptation due to a change in geographical location that differs from migrants’ place of origin. This change in their environment requires migrants to adapt to unfamiliar topography, temperatures, and working conditions. These changes may also be coupled with stress due to separation from family and loved ones (social psychological mechanism). Both structural and social psychological mechanisms may negatively influence the long-term health outcomes of migrants. Although our data do not have direct measures of structural adaptation and social psychological mechanisms, we conceptualized a theoretical framework to empirically investigate the impact of migration on later life health considering the number of years of migration outside of the respondent's birth place as a proxy measure of both mechanisms. We hypothesized that an increased number of years of migration will negatively affect individuals’ later life health due to longer time of exposure to unfamiliar environments that may have required more structural adaptations and caused increased psychological stress among long-term migrants compared to short-term migrants or non-migrants. Specifically, we hypothesized that total number of migration years likely increases later life functional difficulty or negatively influences later life self-rated health, independent of aging and other factors that are known to influence individual health.

As we hypothesized, our findings show that migration adversely influenced both self-rated health and functional difficulty in later life, net of all other controls. These intriguing results provide insight for scholars and policy makers from migrant-sending settings who are grappling with rapid population aging coupled with minimal old age security services and eroding historical family norms, values, and elderly care systems.

As with any study, this study also has limitations. Although our health outcome measures were collected after the measurement of our explanatory and control measures—one of the unique strengths of this study—we were unable to control for baseline health outcomes. This limited our ability to empirically investigate the healthy migrant argument. Second, this investigation was also unable to control for time-varying measures of household socioeconomic status to control for appropriately time-ordered measures associated with the economic prosperity hypothesis. Although our survey lacks time-varying measures of socioeconomic status, we were able to include measures of household land holding as a proxy measure for household wealth. The strengths of this study—temporal ordering the of the measures and comprehensive sets of individual, household, and community measures—together with our findings, provide evidence that suggests extended periods of migration may have adverse consequences for later life health. To further investigate this relationship, future research efforts need to develop panel data with baseline measures of migrant health and appropriately timed measures of confounding factors.

4.1. Conclusions

Globally, migration has increased dramatically in recent decades, leading to an estimated 258 million domestic and 750 million international migrants today, or about 1/7 of the world's population (United Nations 2017; International Organization for Migration, 2018). This massive movement has innumerable effects on the health and well-being of migrants, their families, and origin and destination communities (Seddon et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2015; Taylor, 1999; Koc and Onan, 2004), on population growth and change at the origin and destination (Seddon et al., 2002; Thieme and Wyss, 2005; Taylor, 1999; Koc and Onan, 2004; World Bank Group 2017), on the flow of money, goods, and ideas (Thieme and Wyss, 2005; World Bank Group 2017; Levitt, 1998), and on political stability (Agadjanian and Gorina, 2019; Gebremedhin and Mavisakalyan, 2013). Given these widespread effects, it would be difficult to overestimate the impact of migration.

In this study we employed a unique data set available from the Chitwan Valley Family Study to investigate one of the many possible consequences of migration—the association between migration experiences and later life health. As hypothesized, our findings show that migration adversely influenced both self-rated health and functional difficulty in later life, net of all other controls. These intriguing results provide insight for scholars and policy makers from migrant-sending settings grappling with rapid population aging coupled with minimal old age security services and eroding historical family norms, values, and elderly care systems.

Although this study addresses gaps in previous research, it also raises theoretically relevant and pragmatic questions. Theoretically, without the measure of migrants’ baseline health outcomes, it is not clear whether the migrants spent more years outside of their homes because of their health or whether their health is poor due to periods of long migration (from structural adaptation as well as social psychological stress). We believe the latter is true because of the increasing number of migrant deaths due to suicide and stress at their destination, as well as migrant reports of degrading health conditions upon returning home. Given this limitation, replication of these results is an important next step.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This research was jointly supported by the Economic and Social Research Council and Department for International Development (ESRC-DFID, ESL0120651); the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, R01HD32912, R01HD33551); the Michigan Center on the Demography of Aging at the University of Michigan (U-M), which is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging, Centers on the Demography and Economics of Aging (P30AG012846); and the University of Michigan Population Studies Center (PSC) Small Grant program. The authors gratefully acknowledge use of the services and facilities of the PSC at U-M, funded by an NICHD Center Grant (P2CHD041028). The authors also gratefully acknowledge Cathy Sun for her assistance creating analysis files, constructing measures and conducting analyses; Jennifer Mamer, Adela Baker, and Faith Cole for their assistance preparing this manuscript; the staff of the Institute for Social and Environmental Research–Nepal (ISER–N) for data collection; and the residents of the Western Chitwan Valley for their contributions to the research reported here. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure of Interest

Dr. Ghimire is also the Director of the Institute for Social and Environmental Research in Nepal (ISER-N) that collected the data for the research reported here. Dr. Ghimire's conflict of interest management plan is approved and monitored by the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Footnotes

The following abbreviations are used throughout this paper: Chitwan Valley Family Study (CVFS); Life History Calendar (LHC); Neighborhood History Calendar (NHC).

We also used this measure as a natural log. The results, however, are consistent (results are not shown).

Contributor Information

Dirgha Ghimire, Email: nepdjg@umich.edu.

Prem Bhandari, Email: prembh@umich.edu.

References

- Abraído-Lanza A.F., Dohrenwend B.P., Ng-Mak D.S., Turner J.B. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am. J. Public Health. 1999;89:1543–1548. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V., Gorina E. Economic swings, political instability and migration in Kyrgyzstan. Eur. J. Popul. 2019;35:285–304. doi: 10.1007/s10680-018-9482-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S. Routledge; LondonNew York: 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. [Google Scholar]

- Amin S., Bajracharya A., Bongaarts J., Chau M., Melnikas A.J. Demographic Changes of Nepal: Trends and Policy Implications. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel C.S. Social stress: theory and research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1992;18:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Aseltine R.H., Gore S.L. The variable effects of stress on alcohol use from adolescence to early adulthood. Subst. Use Misuse. 2000;35:643–668. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn W.G., Barber J.S., Ghimire D.J. The neighborhood history calendar: a data collection method designed for dynamic multilevel modeling. Sociol. Methodol. 1997;27:355–392. doi: 10.1111/1467-9531.271031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn W.G., Ghimire D.J., Williams N.E. Collecting survey data during armed conflict. J. Off. Stat. 2012;28:153–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn W.G., Pearce L.D., Ghimire D.J. Innovations in life history calendar applications. Soc. Sci. Res. 1999;28:243–264. doi: 10.1006/ssre.1998.0641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn W.G., Yabiku S.T. Social change, the social organization of families, and fertility limitation. Am. J. Sociol. 2001;106:1219–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Balabanova D.C., McKee M. Self-reported health in Bulgaria: levels and determinants. Scand. J. Public Health. 2002;30:306–312. doi: 10.1080/14034940210164867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett P.A., Spence J.D., Manuck S.B., Jennings J.R. Psychological stress and the progression of carotid artery disease. J. Hypertens. 1997;15:49–55. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli R.F. The structure of autobiographical memory and the event history calendar: potential improvements in the quality of retrospective reports in surveys. Memory. 1998;6:383–406. doi: 10.1080/741942610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentham G. Migration and morbidity: implications for geographical studies of disease. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982;26(1988):49–54. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigbee J.L. Stressful life events and illness occurrence in rural versus urban women. J. Community Health Nurs. 1990;7:105–113. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn0702_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bista D.B. Ratna Pustak Bhandar; Kathmandu, Nepal: 1972. People of Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P., Exeter D., Flowerdew R. The role of population change in widening the mortality gap in Scotland. Area. 2004;36:164–173. doi: 10.1111/j.0004-0894.2004.00212.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns C., Geist C.S. Stressful life events and drug use among adolescents. J. Human Stress. 1984;10:135–139. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1984.9934967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson P. Risk behaviours and self rated health in Russia 1998. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2001;55:806–817. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.11.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A., Paxson C. Sex differences in morbidity and mortality. Demography. 2005;42:189–214. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics . Central Bureau of Statistics Ramshaha Path; Kathmandu, Nepal: 1995. Population Monograph of Nepal 1995, His Majesty's Govt., National Planning Commission Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics . Central Bureau of Statistics Ramshaha Path; Thapathali Kathmandu, Nepal: 2001. Statistical Year Book of Nepal 2001, His Majesty's Government, National Planning Commission Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics . Central Bureau of Statistics Ramshaha Path; Thapathali Kathmandu, Nepal: 2011. Statistical Year Book of Nepal 2011, His Majesty's Government, National Planning Commission Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Liu H., Vikram K., Guo Y. For better or worse: the health implications of marriage separation due to migration in rural china. Demography. 2015;52:1321–1343. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0399-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier V., Tran A., Durand B. Predictive modeling of West Nile virus transmission risk in the Mediterranean Basin: how far from landing? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2013;11:67–90. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110100067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J.W., Jr., David R.J., Symons R., Handler A., Wall S., Andes S. African-American mothers’ perception of their residential environment, stressful life events, and very low birthweight. Epidemiology. 1998;9:286–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell T. Mobility, syphilis, and democracy: pathologizing the mobile body. In: Wrigley R., Revill G., editors. Pathol. Travel, Brill; Rodopi, Amsterdam: 2000. pp. 261–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta K., Menzies D. Cost-effectiveness of tuberculosis control strategies among immigrants and refugees. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;25:1107–1116. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00074004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- P. Datta, Migration to India with special reference to Nepali migration, (1998).

- de Janvry A. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1981. The Agrarian Question and Reformism in Latin America. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim É. The Free Press; New York: 1897. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Elo I.T., Preston S.H. Effects of early-life conditions on adult mortality: a review. Popul. Index. 1992;58:186–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo I.T., Preston S.H. Racial and ethnic differences in mortality of older ages. In: Martin L.G., Soldo B.G., editors. Racial Ethn. Differ. Health Older Am. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 1997. pp. 10–42. [Google Scholar]

- European Academics Science Advisory Council . European Academics Science Advisory Council; 2007. Impact of Migration on Infectious Diseases in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Findley S.E. Westview Press; Boulder: 1987. Rural Development and Migration: A Study Of Family Choices In The Philippines. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D., Thornton A., Camburn D., Alwin D., Young-DeMarco L. The life history calendar: a technique for collecting retrospective data. Sociol. Methodol. 1988;18:37–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage T.B. Population variation in cause of death: level, gender, and period effects. Demography. 1994;31:271–296. doi: 10.2307/2061886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X., Conger R.D., Lorenz F.O., Simons R.L. Parents’ stressful life events and adolescent depressed mood. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1994;35:28–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebremedhin T.A., Mavisakalyan A. Immigration and political instability. Kyklos. 2013;66:317–341. [Google Scholar]

- Gove W.R. Sex, marital status, and mortality. Am. J. Sociol. 1973;79:45–67. doi: 10.1086/225505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung H.B. HMG Population Commission; Kathmandu: 1983. Internal and International Migration in Nepal [in Nepali] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward M.D., Gorman B.K. The long arm of childhood: the influence of early-life social conditions on men's mortality. Demography. 2004;41:87–107. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig C. Nepali Times; 2014. Workers in Exile. [Google Scholar]

- His Majesty's Government . Ministry of Communication; Kathmandu, Nepal: 1973. Mechi to Mahakali, Part 2, Midwestern Development Region, His Majesty's Government. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S.M. An ethnographic study of the social context of migrant health in the United States. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J.S., Landis K.R., Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer R.A., Rogers R.G., Eberstein I.W. Sociodemographic differentials in adult mortality: a review of analytical approaches. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1998;24:553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Idler E.L. Discussion: gender differences in self-rated health, in mortality, and in the relationship between the two. Gerontologist. 2003;43:372–375. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.3.372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E.L., Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997;38:21–37. doi: 10.2307/2955359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration, World Migration Report 2018, (2018). https://www.iom.int/wmr/world-migration-report-2018 (accessed September 25, 2018).

- Joshi S., Simkhada P., Prescott G.J. Health problems of Nepalese migrants working in three gulf countries. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights. 2011;11:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D.P. Chitwan Chamber of Commerce Industry. Narayangaht; 1996. A brief description of Chitwan. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Sonnega A., Bromet E., Hughes M., Nelson C.B. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibele E., Scholz R., Shkolnikov V.M. Low migrant mortality in germany for men aged 65 and older: fact or artifact? Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2008;23:389–393. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9247-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc I., Onan I. International migrants’ remittances and welfare status of the left‐behind families in Turkey. Int. Migr. Rev. 2004;38:78–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmair M., Manandhar S., Subedi B., Thieme S. New figures for old stories: migration and remittances in Nepal. Migr. Lett. 2006;3:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut A.M. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1995. Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the Immigrant Menace. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz P.M., House J.S., Mero R.P., Williams D.R. Stress, life events, and socioeconomic disparities in health: results from the Americans’ changing lives study. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005;46:274–288. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassetter J.H., Callister L.C. The impact of migration on the health of voluntary migrants in Western Societies: a review of the literature. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2008;20:93–104. doi: 10.1177/1043659608325841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclere F.B., Jensen L., Biddlecom A.E. Health care utilization, family context, and adaptation among immigrants to the United States. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1994;35:370–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt P. Social remittances: migration driven local-level forms of cultural diffusion. Int. Migr. Rev. 1998;32:926–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard L.A., Panis C.W.A. Marital status and mortality: the role of health. Demography. 1996;33:313–327. doi: 10.2307/2061764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom M., Sundquist J., Ostergren P. Ethnic differences in self reported health in Malmö in southern Sweden. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 2001;55:97–103. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. Rural-urban migration and health: evidence from longitudinal data in Indonesia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010;70:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas J.W., Barr-Anderson D.J., Kington R.S. Health status, health insurance, and health care utilization patterns of immigrant black men. Am. J. Public Health. 2003;93:1740–1747. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides K.S., Eschbach K. Aging, migration, and mortality: current status of research on the hispanic paradox. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2005;60:68–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M.G., Adelstein A.M., Bulusu L. Lessons from the study of immigrant mortality. Lancet. 1984;323:1455–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91943-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason A. Population ageing and demographic dividends: the time to act is now. Asia-Pac. Popul. J. 2006;21:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Massey D.S., Arango J., Hugo G., Kouaouci A., Pellegrino A., Taylor J.E. Theories of international migration: a review and appraisal. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1993;19:431–466. doi: 10.2307/2938462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A., Arias E., Lost Paradox. Explaining the hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography. 2004;41:385–415. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel E.S., Myers J.K., Dienelt M.N., Klerman G.L., Lindenthal J.J., Pepper M.P. Life events and depression: a controlled study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1969;21:753–760. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1969.01740240113014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza P.V., Le Moal M. Pathophysiological basis of vulnerability to drug abuse: role of an interaction between stress, glucocorticoids, and dopaminergic Neurons. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1996;36:359–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza P.V., Le Moal M.B. The role of stress in drug self-administration. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathaur K.R.S. British gurkha recruitment: a historical perspective. Voice Hist. 2001;16:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Razum O., Zeeb H., Akgün H.S., Yilmaz S. Low overall mortality of Turkish residents in germany persists and extends into a second generation: merely a healthy migrant effect? Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1998;3:297–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razum O., Zeeb H., Rohrmann S. The ’healthy migrant effect’–not merely a fallacy of inaccurate denominator figures. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2000;29:191–192. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R.G., Hummer R.A., Nam C.B. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. Living and Dying in the USA: Behavioral, Health, and Social Differentials of Adult Mortality. [Google Scholar]

- Ross C.E., Mirowsky J. Does employment affect health? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995;36:230–243. doi: 10.2307/2137340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C.E., Wu C. The links between education and health. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1995;60:719–745. doi: 10.2307/2096319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon D., Adhikari J., Gurung G. Foreign labor migration and the remittance economy of Nepal. Crit. Asian Stud. 2002;34:19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom S.C., Miller G.E. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol. Bull. 2004;130:601. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. Nature. 1936;138:32. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.2.230a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. Stress and disease. Science. 1955;122:625–631. doi: 10.1126/science.122.3171.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma H.B., Subedy T.R. Nepal District Profile. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Shivakoti G.P., Axinn W.G., Bhandari P., Chhetri N.B. The impact of community context on land use in an agricultural society. Popul. Environ. 1999;20:191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S. Nepali Times; 2016. Mental Cost of Migration. [Google Scholar]

- Singh G.K., Siahpush M. All-cause and cause-specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States. Am. J. Public Health. 2001;91:392–399. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark O., Taylor J.E. Relative deprivation and international migration. Demography. 1989;26:1–14. doi: 10.2307/2061490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark O., Taylor J.E., Yitzhaki S. Remittances and inequality. Econ. J. 1986;96:722–740. doi: 10.2307/2232987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taran P.A. Human rights of migrants: challenges of the new decade. Int. Migr. 2001;38:7–51. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J.E. The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. Int. Migr. 1999;37:63–88. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieme S., Wyss S. Migration patterns and remittance transfer in Nepal: a case study of sainik basti in western Nepal. Int. Migr. 2005;43:59–98. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro M. Internal Migration in developing countries: a survey. In: Easterlin R.A., editor. Popul. Econ. Change Dev. Ctries. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1980. pp. 361–402. [Google Scholar]

- Trovato F., Lauris G. Marital status and mortaily in Canada: 1951-1981, J. Marriage Fam. 1989;51:907–922. [Google Scholar]

- Undén A.-L., Elofsson S. Do different factors explain self-rated health in men and women? Gend. Med. 2006;3:295–308. doi: 10.1016/S1550-8579(06)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . International Migration Policies; 2017. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/policy/international_migration_policies_data_booklet.pdf Data Booklet (ST/ESA/SER.A/395) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, International Migration Report 2017: Highlights, United Nations, New York, 2017.

- Weitoft G.R., Gullberg A., Hjern A., Rosén M. Mortality statistics in immigrant research: method for adjusting underestimation of mortality. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1999;28:756–763. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.4.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama K.A.S., Noh S. The long arm of community: the influence of childhood community contexts across the early life course. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:894–910. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group . World Bank; Washington, DC: 2017. Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Labor Migration and earnings differences: the case of rural China. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change. 1999;47:767–782. doi: 10.1086/452431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]