ABSTRACT

Rhizobia are a phylogenetically diverse group of soil bacteria that engage in mutualistic interactions with legume plants. Although specifics of the symbioses differ between strains and plants, all symbioses ultimately result in the formation of specialized root nodule organs that host the nitrogen-fixing microsymbionts called bacteroids. Inside nodules, bacteroids encounter unique conditions that necessitate the global reprogramming of physiological processes and the rerouting of their metabolism. Decades of research have addressed these questions using genetics, omics approaches, and, more recently, computational modeling. Here, we discuss the common adaptations of rhizobia to the nodule environment that define the core principles of bacteroid functioning. All bacteroids are growth arrested and perform energy-intensive nitrogen fixation fueled by plant-provided C4-dicarboxylates at nanomolar oxygen levels. At the same time, bacteroids are subject to host control and sanctioning that ultimately determine their fitness and have fundamental importance for the evolution of a stable mutualistic relationship.

KEYWORDS: rhizobium-legume symbiosis, nitrogen fixation, root nodule, microaerobiosis, growth arrest, metabolism, modeling, host sanctioning

INTRODUCTION

Plants are dependent on nutrients such as phosphorus, nitrogen, and sulfur to be present in a bioavailable form, which often limits plant growth. To facilitate nutrient uptake, mutualistic symbioses between plants and root-associated microorganisms have evolved. The symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) originates back to the Devonian period more than 400 million years ago (1). The same signaling pathway that facilitated AM symbioses has since been adopted for other symbionts and is shared among all intracellular root symbionts (2, 3). This includes various root nodule symbioses (4, 5) that evolved around 110 million years ago (6), where the microsymbionts are either actinomycetes or rhizobia. These diazotrophic bacteria fix atmospheric N2 gas into bioavailable ammonia. Biological nitrogen fixation accounts for approximately 50% of the bioavailable nitrogen on earth (7) and is of great importance for sustainable agriculture and the protection of susceptible ecosystems from leached fertilizers (8, 9).

The lack of genetic tools for the microsymbiont has hampered the investigation of actinorhizal symbioses (10), making rhizobium-legume symbioses the most researched and best-understood interactions so far (11). The symbioses between rhizobia (belonging to alpha- and betaproteobacteria [12]) and legumes (Fabaceae) exist with a variety of different infection mechanisms and nodule morphologies (13–15). Although bacterial entry via cracks in the root epidermis and Nod factor-independent infection processes exist (16–19), the best-studied mechanism is root invasion through root hairs via infection threads (ITs). Most major crop legumes and many model plants such as Medicago spp., Pisum sativum (pea), Lotus japonicus, Phaseolus vulgaris (bean), and Glycine max (soybean) follow this type of infection (20–26). Soil-dwelling rhizobia sense flavonoids exuded by the plant (27), and compatible flavonoids trigger the production of Nod factors (lipochitooligosaccharides) (for reviews, see references 28 and 29). Nod factor signaling leads to the induction of nodule primordia in the root cortex and causes the root hairs to curl their tips, resulting in the characteristic shape called “shepherd’s crook.” Bacteria attached to root hairs may be entrapped by this curling and form a microcolony from which they enter the root hair via an IT that is formed by the inverted growth of the plant cell wall and membrane. Since the microcolony is derived from one or very few founder cells, ITs are a major bottleneck for bacteria during invasion (30, 31).

Inside ITs, bacteria are thought to move mainly by cell division and potentially some gliding motility (32, 33). Eventually, the ITs reach the preformed nodule primordia, and rhizobia are taken up into individual plant cells by endocytosis, enclosed by a symbiosome membrane of plant origin. There, they multiply until the plant cell is densely packed with bacteria, which differentiate into their nitrogen-fixing form called a bacteroid. Nodules usually have one of two distinctive morphologies, depending on the host plant (34, 35): (i) determinate nodules, lacking a persistent meristem, therefore ceasing to grow at some point and forming spherical nodules, or (ii) indeterminate nodules with a persistent meristem, resulting in indefinite growth, branching, or lobe formation of the nodule, giving rise to elongated or irregular shapes. The detailed infection processes and differences between determinate and indeterminate nodules have been extensively discussed elsewhere (36–39).

COMPETITIVENESS

Host plants can influence the composition of the root microbiome (40, 41), but rhizobia must compete with various other bacteria for root colonization and with other compatible rhizobial strains for nodulation. Competitiveness is a complex trait: different abiotic factors such as soil pH (42–44) or nutrient availability (45) have an impact on the outcome of symbioses. Biotic factors also affect competitiveness, for example, the host-symbiont pairing (46–48), plant- or strain-intrinsic factors such as type VI secretion systems (49, 50), exopolysaccharide (EPS) production (51), and catabolic capacity in rhizobia for various substrates such as myo-inositol (52–54), glycerol (55), arabinose, protocatechuate (56), rhamnose (57), homoserine (58), or erythritol (59). During the transition from a soil-dwelling bacterium to a nitrogen-fixing bacteroid, rhizobia encounter drastically changing conditions, but it has not always been addressed at which stage of symbiosis formation a mutant strain is affected. Competitiveness in the rhizosphere is largely determined by metabolic functions and motility (48). Transcriptomics and mutant studies have shown that Rhizobium leguminosarum depends on a variety of substrates such as C4-dicarboxylates, C2-organic acids, and aromatic compounds for growth in the rhizosphere. However, sugar and sugar alcohol transport systems were similarly induced, showing that metabolism in the rhizosphere is highly complex (60). It is well documented that strains and mutants can be competitive in rhizosphere colonization but nonetheless lack competitiveness for nodulation (52, 61, 62), highlighting the need for changing adaptations throughout the infection process.

Insertion sequencing (INSeq) experiments using saturated random transposon mutant libraries identified essential genes in R. leguminosarum during four distinct stages of the symbiosis: rhizosphere growth, root attachment, nodule bacteria (viable bacteria within nodules), and differentiated bacteroids (63). In these experiments, bacteria were under selective pressure by pea plants, and mutants lacking competitiveness were lost at the affected and subsequent stages. Interestingly, while several genes were associated with competitiveness in the rhizosphere and root attachment, they were not necessarily involved in competitive nodulation, further indicating that persistence on the root surface is a distinct trait. In total, 390 genes were associated with competitive nodulation. Among these, 146 were already needed in the rhizosphere, 33 were needed in the root-attached stage, and 211 were needed in ITs and predifferentiated bacteroids. Functions related to competitive nodulation from the rhizosphere onward include lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and EPS biosynthesis, the NtrBC system and the σ54 factor RpoN, and the stringent response. LPS and EPS modifications have a known role in evading the plant immune response during IT formation (64–70), and the stringent response has been shown to be involved at multiple stages during the Sinorhizobium-Medicago symbiosis (71–73). During later infection stages, allophanate, aldehyde, erythritol metabolism, and glycogen synthesis play important roles. Interestingly, in agreement with previous screens (48), almost all mutations causing auxotrophies lacked competitiveness, indicating that de novo synthesis of essential building blocks is crucial even when they are exogenously present in root exudates (74, 75).

The large number of genes associated with nodulation found outside the symbiotic plasmids in R. leguminosarum (63) is consistent with the findings for the chimeric Ralstonia solanacearum/Cupriavidus taiwanensis-Mimosa pudica experimental evolution of a symbiosis (76). Although the initial chimera was unable to form nodules, nodulation was achieved and competitiveness was gradually increased with repeated inoculation cycles on M. pudica seedlings. Strikingly, the ability to nodulate was directly linked with competitiveness (77). After initial infection was achieved by a loss of pathogenicity, a major improvement in competitiveness was seen when additional mutations in global transcriptional regulators enhanced intracellular colonization and persistence (78, 79), further highlighting that the ability to competitively nodulate legume plants heavily relies on the global rewiring of bacterial gene expression outside the acquired classical symbiosis genes (nod, nif, fix, etc.) found on mobile symbiotic plasmids or islands (80–84).

Notably, competitiveness for initial nodulation (but not persistence) is not affected by a strain’s efficiency in nitrogen fixation (85). Under field conditions, indigenous rhizobia with an inferior fixation capacity may outcompete the “elite” rhizobial strains inoculated on the legume seeds, resulting in suboptimal yields (86, 87). The dependence on environmental parameters and the overall complexity based on symbiotic and general-function genes (88) make competitive strains with high nitrogen fixation efficiencies difficult to identify. A recently reported barcoded and PnifH-driven superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP)-based toolkit allows the simultaneous high-throughput analysis of a strain’s competitiveness and nitrogen fixation rate (89). It enabled the identification of highly effective strains by measuring fixation rates of individual strains in single nodules. This approach facilitates the parallelized inoculation of multiple strains and the simultaneous assessment of their nodulation competitiveness and nitrogen fixation ability.

ADAPTATIONS TO NITROGEN FIXATION

Root nodules are de novo plant organs that share root- and stem-typical traits (90) and are formed only in the presence of compatible rhizobia. Their specialized function—to host intracellular bacteria for nitrogen fixation—makes the conditions inside nodules unique. Nodules are immunocompromised compartments with an immune response that differs from that of the rest of the plant, but they are also confined and insulated from the root, allowing them to host large numbers of intracellular bacteria (91). Despite some distinguishing properties specific to different rhizobia and their plant hosts, all rhizobium-legume symbioses share some universal characteristics. With the goal of highlighting these core changes defining the transition from free-living bacteria to nitrogen-fixing bacteroids, we performed a meta-analysis of 18 transcriptome and 1 proteome data sets published in 13 different studies on various symbioses (92–104) (Table 1). All genes/proteins were classified according to the Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) system (105) to enable interspecies comparisons.

TABLE 1.

Data sets used in the meta-analysisa

| Species (rhizobium strain-plant host) | Reference data set | Bacteroids terminally differentiated | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841-Pisum sativum | Bacteria grown in MM (mid-exponential phase) | Yes | 98 |

| Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841-Vicia cracca | Bacteria grown in MM (mid-exponential phase) | Yes | 98 |

| Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae A34-Pisum sativum | Bacteria grown in MM (mid- to late exponential phase) | Yes | 99 |

| Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. phaseoli 4292-Phaseolus vulgaris | Bacteria grown in MM (mid- to late exponential phase) | No | 99 |

| Rhizobium etli CFN42-Phaseolus vulgaris | Bacteria grown in MM (early exponential phase) | No | 92 |

| Rhizobium etli CFN42-Phaseolus vulgaris | Bacteria grown in MM (stationary phase) | No | 92 |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011-Medicago truncatula | FIId: distal fraction of ZII; contains cells during infection and differentiation | Yes | 102 |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021-Medicago truncatula | Bacteria grown in CM (mid-exponential phase) | Yes | 95 |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021-Medicago sativa cv. Europe | Bacteria grown in MM (mid-exponential phase) | Yes | 104 |

| Sinorhizobium medicae-Medicago truncatula | FI: nonfixing zone of the nodule | Yes | 97 |

| Sinorhizobium sp. strain NGR234-Vigna unguiculata | Bacteria grown in CM (mid-exponential phase) | No | 101 |

| Sinorhizobium sp. NGR234-Leucaena leucocephala | Bacteria grown in CM (mid-exponential phase) | No | 101 |

| Bradyrhizobium sp. ORS285-Aeschynomene afraspera | Bacteria grown in CM (mid-exponential phase) | Yes | 100 |

| Bradyrhizobium sp. ORS285-Aeschynomene indica | Bacteria grown in CM (mid-exponential phase) | Yes | 100 |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110-Glycine max | Bacteria grown in CM (mid-exponential phase) | No | 96 |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110-Vigna unguiculata | Bacteria grown in CM (mid-exponential phase) | No | 103 |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110-Macroptilium atropurpureum | Bacteria grown in CM (mid-exponential phase) | No | 103 |

| Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571-Sesbania rostrata | Bacteria grown in MM (mid- to late exponential phase) | No | 94 |

| Mesorhizobium huakuii 7653R-Astragalus sinicus | Bacteria grown in CM (late exponential phase) | Yes | 93 |

Transcriptome data were used in all cases apart from the Sinorhizobium medicae study, which is a proteome data set. All data sets compare bacteroids with the reference conditions described in the second column. MM, minimal medium; CM, complex medium.

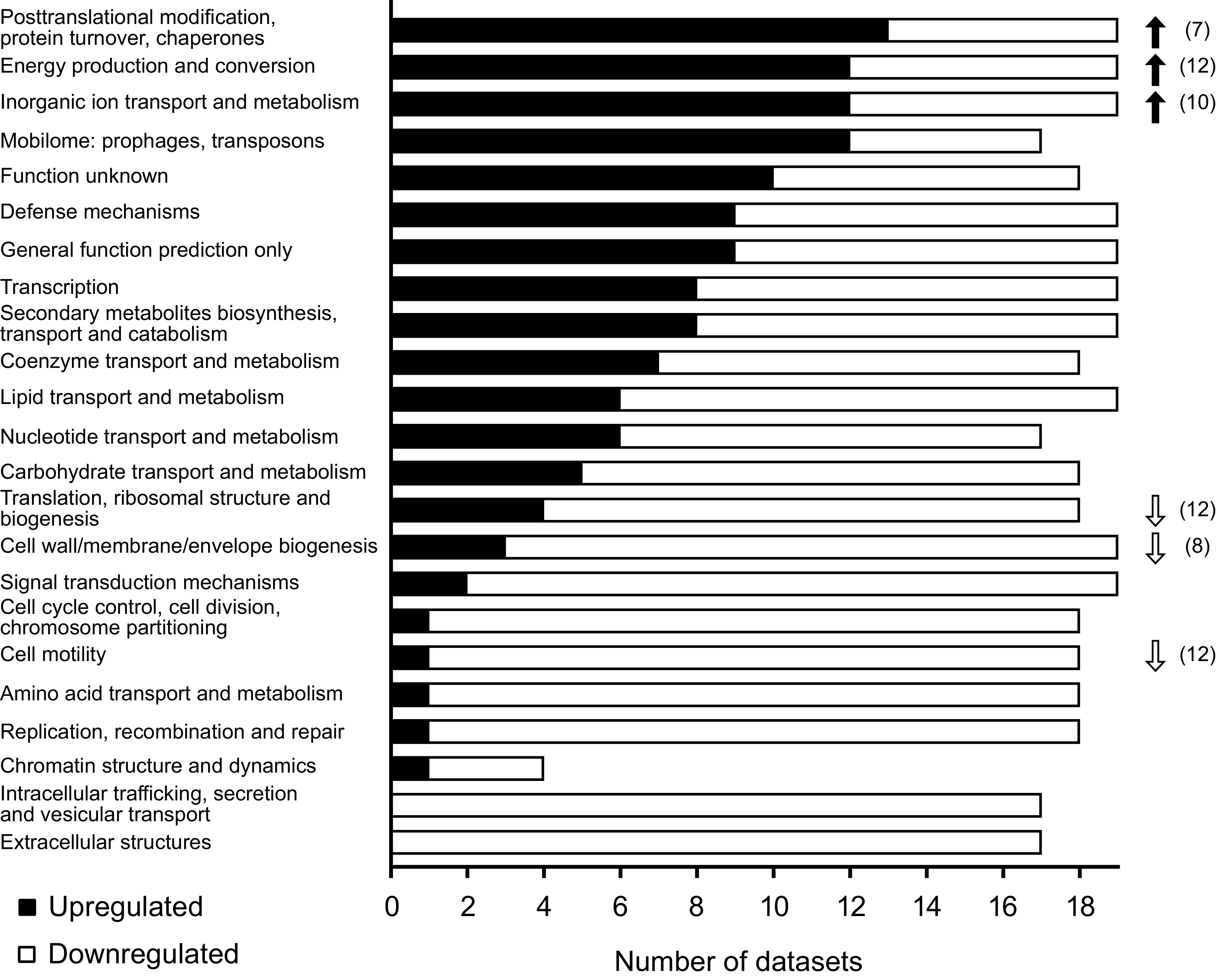

Overall, most of the subsystems contained more downregulated than upregulated genes, indicating a reduced physiological complexity in bacteroids (Fig. 1). Notable exceptions to the general downregulation were “energy production and conversion” and “inorganic ion transport and metabolism” (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Upregulated features in these subsystems comprised nitrogenase components (nif genes) and electron transfer proteins (including fix genes) such as ferredoxins, which act as electron donors for nitrogenase (106, 107) (Table S2). Free-living diazotrophs such as Klebsiella regulate nif gene expression in response to nitrogen starvation and low oxygen concentrations (108), whereas the nitrogen status in many bacteroids plays either no or only a minor role in nif gene activation, which is mainly induced by low oxygen concentrations (see Adaptations to Microaerobic Conditions, below). All rhizobia regulate nif and fix gene expression using similar sets of oxygen-responsive pathways (FixLJ or hFixL FxkR, FixK/Fnr, and NifA). The pathways differ in their sensitivities to oxygen (109), leading to staggered activation and thus a gradual adaptation of the invading rhizobia to the microoxic nodule environment (110). However, each species uses them in a slightly different way, and the interconnections between the pathways differ as well, a topic that has been discussed elsewhere (111–115). In addition to nif genes, the expression of iron and/or molybdenum transporters was increased across the various data sets, consistent with the requirement for these metals as cofactors of the nitrogenase enzyme (116).

FIG 1.

Central features of bacteroids determined from genome scale data sets. A meta-analysis of 18 transcriptome and 1 proteome data sets for bacteroids of various rhizobial strains was performed. The bar graph shows the number of data sets in which a COG category contained more upregulated than downregulated (black) or more downregulated than upregulated (white) genes/proteins. Where the total number is <19, some data sets contained either no differentially expressed genes/proteins or equal numbers of up- and downregulated genes/proteins in this category. Arrows indicate the 3 categories that were most often significantly enriched within upregulated (black) or downregulated (white) genes/proteins, with numbers in parentheses indicating the number of data sets for which significant up/downregulation was observed. P values were determined with a hypergeometric test followed by Bonferroni multiple-test correction, and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant. For the same analysis separated according to terminally differentiated and not terminally differentiated bacteroids, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

General upregulation was further found for chaperones, indicating a response to stress factors in nodules and restructuring of the bacteroid proteome. This agrees with the established importance of chaperones in bacteroids. Nodules formed by a clpB mutant of Mesorhizobium ciceri contained only a few bacteroids (117), and GroESL chaperones were found to be essential for symbiosis (118, 119) and to interact with nodule-specific cysteine-rich (NCR) peptides (120) (see Adaptations to a Nongrowing State, below). Further examples of stress responses include glutathione S-transferases, which were consistently upregulated in bacteroids. Mutants unable to produce glutathione, an important antioxidant molecule, showed reduced symbiotic efficiency (121, 122). Similarly, enzymes involved in the detoxification of reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide dismutases and catalases, were commonly upregulated, in agreement with the presence of reactive oxygen species due to auto-oxidation of leghemoglobin and ferredoxin (123).

ADAPTATIONS TO MICROAEROBIC CONDITIONS

The iron-sulfur clusters of the nitrogenase enzyme are highly susceptible to molecular oxygen (124), and the nodule cortex therefore contains an oxygen diffusion barrier. This limits the amount of free oxygen within the nodule, creating a microoxic environment of around 11 nM free oxygen (112, 125). For comparison, the freely diffused oxygen concentration in water at atmospheric oxygen levels is around 255 μM. Nitrogen fixation is an energy-intensive process, and energy in biological systems is most efficiently generated by respiratory chains with molecular oxygen as the final electron acceptor (126). To circumvent this apparent paradox, where oxygen is needed to energize nitrogen fixation and nitrogenase is sensitive to oxygen, rhizobia possess high-affinity terminal oxidases that allow respiration at low oxygen concentrations. Rhizobia can usually express a complex set of different respiratory oxygen reductases, reflecting their diverse lifestyles (127–130). Biochemical and genetic data show that a cytochrome c oxidase, encoded by fixNOQP, is a high-affinity cbb3-type oxidase responsible for respiration under microaerobic conditions in rhizobia. Biochemical assays revealed a Km value of 4 to 7 nM for oxygen bound to membranes of anaerobically grown bradyrhizobia, corresponding to the cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase FixNOQP (131). These values are compatible with the low oxygen concentrations in nodules. Mutants of fixNOQP in Bradyrhizobium japonicum had only marginal nitrogenase activity (132, 133), whereas multiple copies of fixNOQP are present in the genomes of Mesorhizobium loti, Sinorhizobium meliloti, Rhizobium etli, and R. leguminosarum. In S. meliloti and R. leguminosarum, the two copies are functionally redundant, but only one copy is functional during symbiosis in R. etli (134–136). Mutation of the (single-copy) cbb3-type oxidase in Azorhizobium caulinodans resulted in only a 50% reduction of nitrogenase activity in symbiosis (137). The remaining activity could be abolished by creating a double mutant with a bd-type quinol oxidase. This type of oxidase is crucial for nitrogen fixation in the free-living diazotrophs Klebsiella oxytoca (138) and Azotobacter vinelandii (139). Recently, genome sequences of betaproteobacterial rhizobia showed that Paraburkholderia strains lack fixNOQP but contain bd-type quinol oxidase genes. However, functional studies are missing (140). In accordance with the described adaptations to the microaerobic nodule environment, several cytochromes and high-affinity cytochrome oxidases showed upregulation in our meta-analysis. Interestingly, subunits of the ATP synthase were mostly downregulated, indicating that the overall energy demand in bacteroids is lower than that in exponentially growing cells.

Nodules have a characteristic red color due to the accumulation of leghemoglobins. These plant-derived proteins are found exclusively in the plant cytoplasm and provide buffering capacity for free oxygen as well as facilitating the diffusion of oxygen toward symbiosomes (141–144). Mutation or silencing of leghemoglobin biosynthesis resulted in inefficient symbioses (145, 146). The free oxygen concentration was, however, only marginally higher in mutant than in wild-type nodules. Although there was a slight increase in oxygen available for respiration, the ATP/ADP ratio dropped compared to the wild type (146). Thus, the main function of leghemoglobins is not to keep free oxygen concentrations low (which is achieved by the oxygen diffusion barrier) but rather to enhance the oxygen supply to symbiosomes, which is limiting because of the diffusion barrier. In this function, leghemoglobins are equivalent to myoglobins in animals.

ADAPTATIONS TO A NONGROWING STATE

In addition to changes induced by microoxic conditions, bacteroids are characterized by their nongrowing state. Growth arrest in free-living bacteria is usually induced by unfavorable conditions such as starvation, oxygen depletion, or antibiotic substances. Accordingly, the main adaptations to such conditions focus on persistence, i.e., maintaining low levels of proton motive force, synthesizing integral cell building blocks, slowing metabolism, and catabolizing nonessential endogenous compounds, which enables bacteria to stay viable for months or years (147).

Commonly downregulated traits in the analyzed data sets that are shared with growth-arrested cells (92) include translation (ribosomal proteins), cell envelope biogenesis (outer membrane proteins, peptidoglycan, and exopolysaccharide synthesis), intracellular trafficking, cell cycle control and DNA replication, signal transduction, motility, and the FoF1-type ATPase (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The ribosomal silencing factor RsfS, which inhibits the assembly of the 30S and 50S ribosomal subunits (148, 149), was generally upregulated, indicating additional downregulation of protein biosynthesis. Furthermore, ClpA, a subunit of the ClpAP protease, known for its role in cell cycle control and stationary-phase adaptation (150–152) but also potentially part of FixK regulation (153), was commonly upregulated in bacteroids. These findings suggest that a major adaptation to the nodule environment for bacteroids is related to growth arrest. Strikingly, the experimental evolution experiments described above found mutations in efpR to be associated with adaptation to intracellular colonization (78). EfpR was found to act as a positive regulator of several 30S ribosomal protein subunits and as a negative regulator of the adapter protein ClpS (78), which redirects protein aggregates to ClpAP (154), mimicking the bacteroid growth arrest adaptation.

In contrast to free-living growth-arrested bacteria, however, bacteroids are not nutrient starved, are well adapted for respiration under microoxic conditions, and retain high levels of metabolic activity to sustain nitrogen fixation. It thus remains unknown how and why bacteroids stop dividing. Some legumes induce terminal differentiation and chromosomal endoreduplication in bacteroids, meaning that the bacteroid is unable to dedifferentiate into a free-living bacterium (155, 156). Generally, hosts with determinate nodules (e.g., Lotus, soybean, and bean) harbor bacteroids that are similar to free-living bacteria, and differentiation is not terminal (U morphotype) (157). Legumes of the inverted-repeat-lacking clade and some Aeschynomene spp. contain enlarged and elongated bacteroids (E morphotype) that sometimes branch and become Y-shaped or irregularly shaped. Many legumes of the Dalbergioid cluster (e.g., peanut and Aeschynomene spp.) cause bacteroids to become enlarged and spherical (S morphotype). Rhizobia capable of nodulating different host plants will adopt the bacteroid morphotype of the respective host (31, 158, 159). Enlargement of the bacteroids in the case of E and S morphotypes is accompanied by endoreduplication. This differentiation leads to up to 24C (chromosomes) in E-morphotype S. meliloti bacteroids in symbiosis with Medicago (155). Similarly, Bradyrhizobium sp. strain ORS285 bacteroids reach 7C in Aeschynomene afraspera (E morphotype) and 16C in Aeschynomene indica (S morphotype) (160).

The key factor for bacterial endoreduplication is NCR peptides. These consist of 60 to 90 amino acids and display similarities with plant defensins (161, 162). NCR peptides are abundant in hosts harboring swollen bacteroids (around 700 are known in Medicago truncatula) but evolved independently in different clades (155, 156, 163). They are exclusively expressed in bacteroid-containing cells and are targeted to the bacteroid (164). Plant mutants with defects in the NCR peptide secretory pathway form ineffective nodules (164–166). Some NCR peptides have antimicrobial activities (167, 168), and rhizobia with increased sensitivity to NCR peptides form ineffective symbioses because they are rapidly killed after release from ITs into plant cells (160, 169–172). At the right dosage, however, NCR peptides will promote endoreduplication, even in free-living cultures (173), although the mechanisms by which they interfere with the bacterial cell cycle are not yet fully understood (167). The mode of action of some NCR peptides has been identified, for example, inhibition of FtsZ (the structural component of the Z ring involved in cell division) and ribosomal proteins (120). Moreover, rhizobia are successively exposed to different NCR peptides, suggesting that they act in an orchestrated manner, controlling various steps of rhizobial physiology (173–175). NCR peptide-mediated endoreduplication and terminal differentiation might contribute to the growth-arrested phenotype of bacteroids. However, NCR peptides are absent in hosts harboring unswollen (U morphotype) bacteroids (176), and endoreduplication and swelling of bacteroids happen only after bacteroids stop dividing (159), indicating the presence of other mechanisms that are yet to be discovered.

METABOLIC ADAPTATIONS

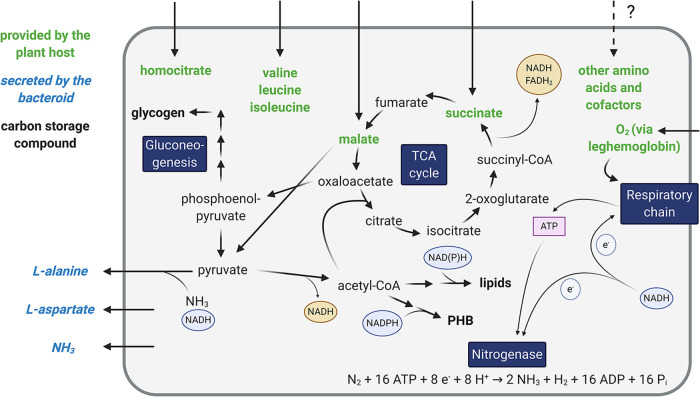

As a result of the adaptations required for symbiotic nitrogen fixation, bacteroid metabolism is unique in several respects: there is a strong downregulation of most biosynthetic functions compared to growth in the free-living state, while specialized enzymes for nitrogen fixation are highly induced (98, 177). In contrast to free-living bacteria in stationary phase, bacteroid metabolism is highly active due to the energy requirement of nitrogen fixation despite the microoxic environment. In addition, bacteroid metabolism is closely interdependent with the plant host because of bidirectional nutrient exchanges between the symbiotic partners (Fig. 2) (116, 178).

FIG 2.

Central metabolic and transport reactions in bacteroids. Shown is a schematic map of major metabolic pathways and transport reactions in bacteroids as well as important flows of electrons and ATP. This figure was created with BioRender.

An important implication of nutrient provision by the plant is that downregulation in biosynthetic pathways can occur either because a compound is required only in small quantities in bacteroids or because it is provided by the plant. Multiple auxotrophic rhizobial mutants with a Fix+ phenotype are known, indicating that plants provide the respective compounds to their bacteroids (179). A striking illustration of this concept is symbiotic auxotrophy: mutants lacking the general amino acid permeases Aap and Bra in R. leguminosarum were severely impaired in their symbiotic efficiency, indicating a requirement for plant supply of amino acids (180). While free-living rhizobia are capable of synthesizing all proteinogenic amino acids, downregulation in branched-chain amino acid synthesis occurs in bacteroids, making them dependent on the supply of branched-chain amino acids by their host plant (181, 182). A similar downregulation was observed in our meta-analysis for serine biosynthesis. Indeed, a serine auxotrophic mutant of R. etli was fully proficient in symbiosis (183). Yet cysteine biosynthesis, which requires serine as a precursor, was one of the few upregulated pathways for amino acid biosynthesis. This upregulation is likely related to the production of iron-sulfur clusters for the nitrogenase enzyme, which starts with cysteine as a sulfur donor (184). It is therefore possible that plant hosts supply serine to bacteroids to assist with cysteine biosynthesis for nitrogenase assembly. Experimental evidence also supports the provision of amino acids by the plant host that are nonessential for bacteroid functioning. In pea, enzymes catabolizing γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are highly induced in bacteroids, and labeling studies indicated that GABA is supplied by the plant, but mutants of R. leguminosarum unable to catabolize GABA differentiated into functional bacteroids (185).

Apart from amino acids, a different example of plant-derived metabolites essential for nitrogenase activity is homocitrate, a component of the iron-molybdenum cofactor. In contrast to free-living diazotrophs, most symbiotic rhizobia are unable to synthesize homocitrate, and a homocitrate synthase mutant (Fen1) of L. japonicus was incapable of forming effective nodules (186). These observations illustrate the intricate control that plants exercise over their bacterial symbiont.

Legumes provide bacteroids with C4-dicarboxylates as the main carbon source, primarily malate and succinate (187–189). Catabolism of C4-dicarboxylates requires their conversion to both oxaloacetate and acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which are condensed to form citrate in the first step of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. There are two pathways for generating acetyl-CoA from TCA cycle intermediates: (i) malate is oxidized to pyruvate by malic enzyme (ME), or (ii) phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK) converts oxaloacetate into phosphoenolpyruvate, which is converted into pyruvate by pyruvate kinase (PK). In both cases, acetyl-CoA is obtained from pyruvate via the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. While all bacteroids are required to convert TCA cycle intermediates into acetyl-CoA, the synthesis routes differ. Bacteroids of S. meliloti and A. caulinodans exclusively use ME (190, 191), whereas Sinorhizobium fredii and R. leguminosarum utilize both ME and PCK/PK (191, 192). In addition, the activity of PCK is important for bacteroids to sustain gluconeogenesis, which is essential for the production of precursors for various metabolites (63, 193). The TCA cycle is the main pathway for dicarboxylate metabolism in bacteroids, and at least some TCA cycle enzymes were upregulated in the transcriptome/proteome data sets across different rhizobial species. However, studies with individual mutants have produced contradictory evidence on which parts of the TCA cycle are required for nitrogen fixation. Mutants in different TCA cycle enzymes were Fix− in S. meliloti, S. fredii, Rhizobium tropici, and R. leguminosarum (194–198), but several TCA cycle mutants in B. japonicum still formed an efficient symbiosis (199–202). This may be explained by flux through anaplerotic reactions or the existence of uncharacterized isozymes (203). For example, an aconitase mutant of B. japonicum retained almost 30% of the aconitase activity (201). Additional mutant studies with careful evaluation of both enzyme activities and redirection of metabolic fluxes are therefore required to elucidate the essentiality of flux through different parts of the TCA cycle.

Dicarboxylate catabolism in the TCA cycle generates large amounts of reduced electron carriers (NADH and reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide [FADH2]) required for ATP synthesis and nitrogen fixation (116, 178). Due to the low oxygen levels in nodules, flux through the TCA cycle may become disadvantageous because the oxidation of electron carriers in the respiratory chain is restricted, and the accumulation of reducing equivalents inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (204–206). Bacteroids could therefore channel carbon into polymers such as polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), glycogen, and lipids (106, 207–209). Accumulation of these polymers is observed in bacteroids, although the nature of the compounds differs between symbioses (106, 210). In B. japonicum, the regulator of PHB synthesis, PhaR, has been shown to repress various gene targets, notably FixK2, a transcriptional regulator for adaptation to microoxic conditions (211, 212). This suggests a certain degree of coordination between PHB metabolism and symbiotic adaptation, at least in some rhizobial strains.

A fundamental requirement for rhizobium-legume symbioses is the secretion of fixed nitrogen to the plant instead of its assimilation by the bacteroid. Ammonia is the main secretion product, but the secretion of alanine and aspartate has also been reported (213–216). The glutamine synthetase-glutamate oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GS-GOGAT) system, which assimilates ammonia into glutamate in free-living rhizobia, appears to be largely downregulated in bacteroids (116, 217). Rhizobia usually possess two glutamine synthetases (GSI/GlnA and GSII/GlnII), with some strains encoding a third enzyme (GSIII/GlnT). In general, only GSI activity is present at low levels in bacteroids, and the deletion of any of the GS genes does not impair the symbiosis (217, 218). Mutant studies have further shown GOGAT to be dispensable in S. meliloti (219, 220), R. etli (221), and R. leguminosarum (222). Overall, these results indicate no need for ammonia assimilation by the bacteroid, which may be due to amino acid provision by the plant or reduced protein biosynthesis as a result of growth arrest.

A recent study showed that the nitrogen-related phosphotransferase system in R. leguminosarum controls central carbon metabolism in response to carbon and nitrogen availability, and mutation of this system caused an ineffective symbiosis (223). This highlights the complex interconnection between carbon and nitrogen metabolism in bacteroids, which must be finely tuned to enable a functional symbiosis. The complex regulatory systems underlying rhizobial nitrogen metabolism have been comprehensively discussed elsewhere (179, 217, 224).

MODELING BACTEROID METABOLISM

Bacteroid metabolism is difficult to investigate experimentally due to the challenge of measuring nutrient exchange with the plant host, the multiple lifestyle adaptations required during symbiosis formation (63), and the fragile nature of isolated bacteroids (178). In addition to various omics techniques, constraint-based metabolic models have therefore become a popular tool for investigating rhizobium-legume symbioses (225). Metabolic models are knowledgebases of the reactions catalyzed by enzymes encoded in an organism’s genome. By imposing an objective function and assuming a steady state of all metabolic reactions, flux distributions are calculated using flux balance analysis (FBA) (226, 227). Models with different scopes have been reconstructed for various rhizobial species (see Table S4 in the supplemental material), and studies have progressed from describing bacteroid metabolism (228–231) to integrating bacterial and plant models as well as models of nodule zone-specific metabolism (232, 233). Rhizobial genomes are large and may include secondary replicons encoding niche-specific functions (60, 234). Metabolic models specific to the nitrogen-fixing state must therefore be constrained using transcriptome and proteome data sets (228) and/or appropriate objective functions (231, 234). Since direct measurement of reaction rates and exchange fluxes with the plant is infeasible, FBA studies have mostly used objective functions composed of generally accepted features of bacteroid metabolism, such as nitrogen fixation, amino acid secretion, and the production of carbon polymers (229, 230, 235).

All models published to date are consistent with experimental evidence for the use of the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation as the main pathways fueling bacteroid metabolism. Similar to the disparities in experimental results, the operation of both a full and a partial TCA cycle during nitrogen fixation has been predicted. This may be due to strain-specific differences as well as the choice of constraints, in particular carbon and oxygen uptake rates. Synthesis of carbon polymers as well as amino acid exchange with the plant have also been investigated in silico. An increase in symbiotic efficiency was predicted for the deletion of glycogen or PHB synthesis in R. etli (229), which agrees with the enhanced symbiotic properties of a glycogen synthase mutant of R. tropici (236) but not with the phenotypes of mutants for PHB and glycogen synthases in R. leguminosarum and S. meliloti (207, 209). Most, but not all, models assume extensive amino acid cycling between the plant and bacteroid. This is based on early experimental studies suggesting glutamate supply by the plant (180), which, however, was later shown to be nonessential for bacteroids (181). With regard to amino acids secreted by the bacteroid, alanine has been predicted to be the main nitrogenous compound produced at low oxygen levels since it serves as a sink for both carbon and electrons (232).

A recent study of an integrated model for plant and bacteroid metabolism further addressed the question of why C4-dicarboxylates are supplied to bacteroids instead of sucrose, which is abundant in nodules. Rhizobia differentiating into bacteroids were predicted to catabolize sugars (233), which is supported by studies of mutants in dicarboxylate transport, which are able to nodulate and differentiate into bacteroids but fail to fix nitrogen (187, 188). Modeling results reported previously (233) indicated that sucrose catabolism in fully differentiated bacteroids would achieve higher yields of fixed nitrogen and that proton supply by the plant is required to support the catabolism of C4-dicarboxylates. The provision of C4-dicarboxylates was further predicted to be driven by oxygen limitation of the plant mitochondria (233). Experimental evidence has been found for oxygen limitation of both plant (106) and bacteroid (237, 238) fractions, highlighting this as an outstanding question for future studies.

It is important to note that carbon polymer synthesis and amino acid secretion are commonly included in the bacteroid objective function in addition to ammonia export. Since flux distributions calculated by FBA must produce all compounds that are part of the objective function, carbon and nitrogen allocations in metabolic models are constrained by forcing the stoichiometric production of these compounds. This was circumvented by an integrated model of plant and bacteroid metabolism and optimization for plant biomass production (233). In future studies, the application of comprehensive and unbiased modeling approaches, such as elementary flux mode enumeration (239), may be insightful to improve and expand our current understanding of bacteroid metabolism.

Apart from the direct characterization of bacteroid metabolism, the underlying gene-protein-reaction relationships in metabolic models are useful for guiding targeted investigation of gene essentiality. Seeing as symbiosis formation is a multistep process requiring various metabolic capabilities at different stages (63), it is difficult to distinguish between genes essential for infection and those for essential nitrogen fixation itself. Discrepancies between experimental and in silico gene essentiality can thus unravel metabolic requirements at different stages of symbiosis formation.

PLANT CONTROL AND METABOLIC SANCTIONING

Both computational and experimental studies have demonstrated how bacteroid metabolism can be modulated in response to nutrient supply by the plant, in particular carbon and oxygen (240, 241). Plant control over bacteroid metabolism is essential due to the high fitness cost of nodule formation and the maintenance of bacteroids. The plant host must therefore be capable of monitoring symbiotic performance and responding accordingly, which becomes even more important when considering that the efficiency of the symbiont cannot be evaluated prior to nodulation (85, 242). Mathematical models demonstrated that a substantial investment in nitrogen fixation will be advantageous for rhizobia only if the plant adjusts its resource allocation according to symbiotic performance (243). To maximize their fitness, reproductive bacteroids can divert some of the plant-supplied carbon into polymers and catabolize those after dedifferentiation into the free-living state. For nonreproductive bacteroids, the undifferentiated population in the nodule benefits from the carbon supply and will be released into the soil after nodule senescence (244). Thus, the rhizobium-legume symbioses seem prone to selecting for cheaters that fix no or little nitrogen. In fact, field isolates vary greatly in their nitrogen fixation efficiencies (89). Consequently, legumes must have the means to identify and punish inefficient strains to maximize the nitrogen return for their carbon investment. It is well established that Fix− strains do not persist within mature nodules (245), and when nodules are coinhabited with a fixing strain, the Fix− strain is sanctioned rapidly in a cell-autonomous way (246). Sanctioning results in a fitness increase of good symbionts since higher numbers will be released from nodules. Under experimental conditions, efficient symbionts will outcompete Fix− strains in a few plant generations (247, 248) since plants readily select the most efficient strain (249), even when the initial cell numbers are lower than those of the less efficient strain. Experimental data on carbon and oxygen supply to cheating strains (85, 240, 241) show that plants sense and integrate the nitrogen output from bacteroids and readjust carbon investment (250) or apply oxygen sanctioning in response to poorly performing strains.

FINAL CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The bacteroid stage in the rhizobial life cycle features a unique combination of traits. It is characterized by a nongrowing state in an oxygen-depleted environment. Despite the downregulation of many biosynthetic pathways, bacteroids maintain a highly active and specialized metabolism driven by the catabolism of C4-dicarboxylates. Rhizobia are equipped with specialized functions to cope with this environment, and global adjustments of cellular and metabolic processes must take place to ensure a successful transition to nitrogen-fixing bacteroids. Failure to do so is punished by the host plant and results in the reduced fitness of a rhizobial strain. Host plants impose control over their symbionts at multiple levels. Nutrient supply, mostly in the form of malate and succinate, can be reduced; the oxygen supply can be limited; or, in some cases, plants can target bacteroids directly with antimicrobial peptides to force them into terminal differentiation.

Despite major advances in our knowledge, the complex interactions in rhizobium-legume symbioses retain many unanswered questions. Modulation of the plant immune response by both the host and the symbiont to accommodate thousands of intracellular prokaryotes per cell, what it shares with the better-understood immune response during infection, and its interplay with host sanctioning and pathogens remain exciting research areas despite substantial published work (245, 251–253). Similarly, our understanding of nutrient supply to bacteroids beyond malate and branched-chain amino acids is fragmented, obscuring the stoichiometry of metabolic fluxes that drive nitrogen fixation. The rhizobium-legume symbioses are prime examples of biological systems whose complexity necessitates the combination of experimental and computational approaches. In silico modeling is a rapidly advancing field that will greatly contribute to our understanding of the symbioses and aid in advancing toward engineering synthetic symbioses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PostDoc.Mobility fellowship number 183901 to R.L.) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (grant number BB/M011224/1). C.C.M.S. is supported by the Clarendon Fund (Oxford University Press) and the Keble College De Breyne scholarship.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

jb.00539-20-s0001.pdf (560.9KB, pdf)

Contributor Information

Raphael Ledermann, Email: raphael.ledermann@plants.ox.ac.uk.

William Margolin, McGovern Medical School.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brundrett MC. 2002. Coevolution of roots and mycorrhizas of land plants. New Phytol 154:275–304. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radhakrishnan GV, Keller J, Rich MK, Vernie T, Mbadinga Mbadinga DL, Vigneron N, Cottret L, Clemente HS, Libourel C, Cheema J, Linde A-M, Eklund DM, Cheng S, Wong GKS, Lagercrantz U, Li F-W, Oldroyd GED, Delaux P-M. 2020. An ancestral signalling pathway is conserved in intracellular symbioses-forming plant lineages. Nat Plants 6:280–289. 10.1038/s41477-020-0613-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gherbi H, Markmann K, Svistoonoff S, Estevan J, Autran D, Giczey G, Auguy F, Peret B, Laplaze L, Franche C, Parniske M, Bogusz D. 2008. SymRK defines a common genetic basis for plant root endosymbioses with arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi, rhizobia, and Frankia bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:4928–4932. 10.1073/pnas.0710618105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Morgan DR, Swensen SM, Mullin BC, Dowd JM, Martin PG. 1995. Chloroplast gene sequence data suggest a single origin of the predisposition for symbiotic nitrogen fixation in angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:2647–2651. 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delaux PM, Radhakrishnan G, Oldroyd G. 2015. Tracing the evolutionary path to nitrogen-fixing crops. Curr Opin Plant Biol 26:95–99. 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griesmann M, Chang Y, Liu X, Song Y, Haberer G, Crook MB, Billault-Penneteau B, Lauressergues D, Keller J, Imanishi L, Roswanjaya YP, Kohlen W, Pujic P, Battenberg K, Alloisio N, Liang Y, Hilhorst H, Salgado MG, Hocher V, Gherbi H, Svistoonoff S, Doyle JJ, He S, Xu Y, Xu S, Qu J, Gao Q, Fang X, Fu Y, Normand P, Berry AM, Wall LG, Ane J-M, Pawlowski K, Xu X, Yang H, Spannagl M, Mayer KFX, Wong GK-S, Parniske M, Delaux P-M, Cheng S. 2018. Phylogenomics reveals multiple losses of nitrogen-fixing root nodule symbiosis. Science 361:eaat1743. 10.1126/science.aat1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herridge DF, Peoples MB, Boddey RM. 2008. Global inputs of biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Plant Soil 311:1–18. 10.1007/s11104-008-9668-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson BJ, Indrasumunar A, Hayashi S, Lin MH, Lin YH, Reid DE, Gresshoff PM. 2010. Molecular analysis of legume nodule development and autoregulation. J Integr Plant Biol 52:61–76. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler D, Coyle M, Skiba U, Sutton MA, Cape JN, Reis S, Sheppard LJ, Jenkins A, Grizzetti B, Galloway JN, Vitousek P, Leach A, Bouwman AF, Butterbach-Bahl K, Dentener F, Stevenson D, Amann M, Voss M. 2013. The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20130164. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pesce C, Oshone R, Hurst SG, IV, Kleiner VA, Tisa LS. 2019. Stable transformation of the actinobacteria Frankia spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e00957-19. 10.1128/AEM.00957-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward MH. 1887. On the tubular swellings on the root of Vicia faba. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 178:539–562. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masson-Boivin C, Giraud E, Perret X, Batut J. 2009. Establishing nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with legumes: how many Rhizobium recipes? Trends Microbiol 17:458–466. 10.1016/j.tim.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadri A-E, Spaink HP, Bisseling T, Brewin NJ. 1998. Diversity of root nodulation and rhizobial infection processes, p 347–360. In Spaink HP, Kondorosi A, Hooykaas PJJ (ed), The Rhizobiaceae. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 10.1007/978-94-011-5060-6_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sprent JI, Ardley J, James EK. 2017. Biogeography of nodulated legumes and their nitrogen-fixing symbionts. New Phytol 215:40–56. 10.1111/nph.14474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprent JI. 2009. Legume nodulation: a global perspective, p 1–33. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex, United Kingdom. 10.1002/9781444316384.ch1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alazard D, Duhoux E. 1990. Development of stem nodules in a tropical forage legume, Aeschynomene afraspera. J Exp Bot 41:1199–1206. 10.1093/jxb/41.9.1199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaintreuil C, Arrighi JF, Giraud E, Miche L, Moulin L, Dreyfus B, Munive-Hernandez JA, Villegas-Hernandez MD, Bena G. 2013. Evolution of symbiosis in the legume genus Aeschynomene. New Phytol 200:1247–1259. 10.1111/nph.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giraud E, Moulin L, Vallenet D, Barbe V, Cytryn E, Avarre JC, Jaubert M, Simon D, Cartieaux F, Prin Y, Bena G, Hannibal L, Fardoux J, Kojadinovic M, Vuillet L, Lajus A, Cruveiller S, Rouy Z, Mangenot S, Segurens B, Dossat C, Franck WL, Chang WS, Saunders E, Bruce D, Richardson P, Normand P, Dreyfus B, Pignol D, Stacey G, Emerich D, Vermeglio A, Medigue C, Sadowsky M. 2007. Legumes symbioses: absence of nod genes in photosynthetic bradyrhizobia. Science 316:1307–1312. 10.1126/science.1139548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okazaki S, Kaneko T, Sato S, Saeki K. 2013. Hijacking of leguminous nodulation signaling by the rhizobial type III secretion system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:17131–17136. 10.1073/pnas.1302360110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turgeon BG, Bauer WD. 1985. Ultrastructure of infection-thread development during the infection of soybean by Rhizobium japonicum. Planta 163:328–349. 10.1007/BF00395142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvert HE, Pence MK, Pierce M, Malik NSA, Bauer WD. 1984. Anatomical analysis of the development and distribution of Rhizobium infections in soybean roots. Can J Bot 62:2375–2384. 10.1139/b84-324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heron DS, Pueppke SG. 1984. Mode of infection, nodulation specificity, and indigenous plasmids of 11 fast-growing Rhizobium japonicum strains. J Bacteriol 160:1061–1066. 10.1128/JB.160.3.1061-1066.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pueppke SG. 1983. Rhizobium infection threads in root hairs of Glycine max (L.) Merr., Glycine soja Sieb. & Zucc, and Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. Can J Microbiol 29:69–76. 10.1139/m83-011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szczyglowski K, Shaw RS, Wopereis J, Copeland S, Hamburger D, Kasiborski B, Dazzo FB, de Bruijn FJ. 1998. Nodule organogenesis and symbiotic mutants of the model legume Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 11:684–697. 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.7.684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rae AL, Bonfante-Fasolo P, Brewin NJ. 1992. Structure and growth of infection threads in the legume symbiosis with Rhizobium leguminosarum. Plant J 2:385–395. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.1992.00385.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gage DJ, Bobo T, Long SR. 1996. Use of green fluorescent protein to visualize the early events of symbiosis between Rhizobium meliloti and alfalfa (Medicago sativa). J Bacteriol 178:7159–7166. 10.1128/jb.178.24.7159-7166.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper JE. 2004. Multiple responses of rhizobia to flavonoids during legume root infection. Adv Bot Res 41:1–62. 10.1016/S0065-2296(04)41001-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Haeze W, Holsters M. 2002. Nod factor structures, responses, and perception during initiation of nodule development. Glycobiology 12:79R–105R. 10.1093/glycob/12.6.79r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spaink HP. 2000. Root nodulation and infection factors produced by rhizobial bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 54:257–288. 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gage DJ. 2002. Analysis of infection thread development using Gfp- and DsRed-expressing Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 184:7042–7046. 10.1128/jb.184.24.7042-7046.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ledermann R, Bartsch I, Remus-Emsermann MN, Vorholt JA, Fischer HM. 2015. Stable fluorescent and enzymatic tagging of Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens to analyze host-plant infection and colonization. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 28:959–967. 10.1094/MPMI-03-15-0054-TA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fournier J, Timmers AC, Sieberer BJ, Jauneau A, Chabaud M, Barker DG. 2008. Mechanism of infection thread elongation in root hairs of Medicago truncatula and dynamic interplay with associated rhizobial colonization. Plant Physiol 148:1985–1995. 10.1104/pp.108.125674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewin NJ. 2004. Plant cell wall remodelling in the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Crit Rev Plant Sci 23:293–316. 10.1080/07352680490480734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson KJ, Anjaiah V, Nambiar PT, Ausubel FM. 1987. Isolation and characterization of symbiotic mutants of Bradyrhizobium sp. (Arachis) strain NC92: mutants with host-specific defects in nodulation and nitrogen fixation. J Bacteriol 169:2177–2186. 10.1128/jb.169.5.2177-2186.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pueppke SG, Broughton WJ. 1999. Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and R. fredii USDA257 share exceptionally broad, nested host ranges. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 12:293–318. 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newcomb W, Sippell D, Peterson RL. 1979. The early morphogenesis of Glycine max and Pisum sativum root nodules. Can J Bot 57:2603–2616. 10.1139/b79-309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newcomb W. 1981. Nodule morphogenesis and differentiation. Int Rev Cytol Suppl 13:247–298. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brewin NJ. 1991. Development of the legume root nodule. Annu Rev Cell Biol 7:191–226. 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirsch AM. 1992. Developmental biology of legume nodulation. New Phytol 122:211–237. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1992.tb04227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tkacz A, Cheema J, Chandra G, Grant A, Poole PS. 2015. Stability and succession of the rhizosphere microbiota depends upon plant type and soil composition. ISME J 9:2349–2359. 10.1038/ismej.2015.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zgadzaj R, Garrido-Oter R, Jensen DB, Koprivova A, Schulze-Lefert P, Radutoiu S. 2016. Root nodule symbiosis in Lotus japonicus drives the establishment of distinctive rhizosphere, root, and nodule bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E7996–E8005. 10.1073/pnas.1616564113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frey SD, Blum LK. 1994. Effect of pH on competition for nodule occupancy by type I and type II strains of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. phaseoli. Plant Soil 163:157–164. 10.1007/BF00007964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angus AA, Lee A, Lum MR, Shehayeb M, Hessabi R, Fujishige NA, Yerrapragada S, Kano S, Song N, Yang P, Estrada de los Santos P, de Faria SM, Dakora FD, Weinstock G, Hirsch AM. 2013. Nodulation and effective nitrogen fixation of Macroptilium atropurpureum (siratro) by Burkholderia tuberum, a nodulating and plant growth promoting β-proteobacterium, are influenced by environmental factors. Plant Soil 369:543–562. 10.1007/s11104-013-1590-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rathi S, Tak N, Bissa G, Chouhan B, Ojha A, Adhikari D, Barik SK, Satyawada RR, Sprent JI, James EK, Gehlot HS. 2018. Selection of Bradyrhizobium or Ensifer symbionts by the native Indian caesalpinioid legume Chamaecrista pumila depends on soil pH and other edaphic and climatic factors. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94:fiy180. 10.1093/femsec/fiy180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elliott GN, Chou JH, Chen WM, Bloemberg GV, Bontemps C, Martinez-Romero E, Velazquez E, Young JP, Sprent JI, James EK. 2009. Burkholderia spp. are the most competitive symbionts of Mimosa, particularly under N-limited conditions. Environ Microbiol 11:762–778. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lardi M, de Campos SB, Purtschert G, Eberl L, Pessi G. 2017. Competition experiments for legume infection identify Burkholderia phymatum as a highly competitive β-rhizobium. Front Microbiol 8:1527. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boivin S, Ait Lahmidi N, Sherlock D, Bonhomme M, Dijon D, Heulin-Gotty K, Le-Quere A, Pervent M, Tauzin M, Carlsson G, Jensen E, Journet EP, Lopez-Bellido R, Seidenglanz M, Marinkovic J, Colella S, Brunel B, Young P, Lepetit M. 2020. Host-specific competitiveness to form nodules in Rhizobium leguminosarum symbiovar viciae. New Phytol 226:555–568. 10.1111/nph.16392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salas ME, Lozano MJ, Lopez JL, Draghi WO, Serrania J, Torres Tejerizo GA, Albicoro FJ, Nilsson JF, Pistorio M, Del Papa MF, Parisi G, Becker A, Lagares A. 2017. Specificity traits consistent with legume-rhizobia coevolution displayed by Ensifer meliloti rhizosphere colonization. Environ Microbiol 19:3423–3438. 10.1111/1462-2920.13820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell AB, LeRoux M, Hathazi K, Agnello DM, Ishikawa T, Wiggins PA, Wai SN, Mougous JD. 2013. Diverse type VI secretion phospholipases are functionally plastic antibacterial effectors. Nature 496:508–512. 10.1038/nature12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Campos SB, Lardi M, Gandolfi A, Eberl L, Pessi G. 2017. Mutations in two Paraburkholderia phymatum type VI secretion systems cause reduced fitness in interbacterial competition. Front Microbiol 8:2473. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geddes BA, Gonzalez JE, Oresnik IJ. 2014. Exopolysaccharide production in response to medium acidification is correlated with an increase in competition for nodule occupancy. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 27:1307–1317. 10.1094/MPMI-06-14-0168-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fry J, Wood M, Poole PS. 2001. Investigation of myo-inositol catabolism in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae and its effect on nodulation competitiveness. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14:1016–1025. 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.8.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang G, Krishnan AH, Kim YW, Wacek TJ, Krishnan HB. 2001. A functional myo-inositol dehydrogenase gene is required for efficient nitrogen fixation and competitiveness of Sinorhizobium fredii USDA191 to nodulate soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). J Bacteriol 183:2595–2604. 10.1128/JB.183.8.2595-2604.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kohler PR, Zheng JY, Schoffers E, Rossbach S. 2010. Inositol catabolism, a key pathway in Sinorhizobium meliloti for competitive host nodulation. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:7972–7980. 10.1128/AEM.01972-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ding H, Yip CB, Geddes BA, Oresnik IJ, Hynes MF. 2012. Glycerol utilization by Rhizobium leguminosarum requires an ABC transporter and affects competition for nodulation. Microbiology (Reading) 158:1369–1378. 10.1099/mic.0.057281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garcia-Fraile P, Seaman JC, Karunakaran R, Edwards A, Poole PS, Downie JA. 2015. Arabinose and protocatechuate catabolism genes are important for growth of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae in the pea rhizosphere. Plant Soil 390:251–264. 10.1007/s11104-015-2389-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oresnik IJ, Pacarynuk LA, O’Brien SAP, Yost CK, Hynes MF. 1998. Plasmid-encoded catabolic genes in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii: evidence for a plant-inducible rhamnose locus involved in competition for nodulation. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 11:1175–1185. 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.12.1175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vanderlinde EM, Hynes MF, Yost CK. 2014. Homoserine catabolism by Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841 requires a plasmid-borne gene cluster that also affects competitiveness for nodulation. Environ Microbiol 16:205–217. 10.1111/1462-2920.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yost CK, Rath AM, Noel TC, Hynes MF. 2006. Characterization of genes involved in erythritol catabolism in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. Microbiology (Reading) 152:2061–2074. 10.1099/mic.0.28938-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramachandran VK, East AK, Karunakaran R, Downie JA, Poole PS. 2011. Adaptation of Rhizobium leguminosarum to pea, alfalfa and sugar beet rhizospheres investigated by comparative transcriptomics. Genome Biol 12:R106. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ledermann R, Bartsch I, Müller B, Wülser J, Fischer HM. 2018. A functional general stress response of Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens is required for early stages of host plant infection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 31:537–547. 10.1094/MPMI-11-17-0284-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moawad HA, Ellis WR, Schmidt EL. 1984. Rhizosphere response as a factor in competition among three serogroups of indigenous Rhizobium japonicum for nodulation of field-grown soybeans. Appl Environ Microbiol 47:607–612. 10.1128/AEM.47.4.607-612.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wheatley RM, Ford BL, Li L, Aroney STN, Knights HE, Ledermann R, East AK, Ramachandran VK, Poole PS. 2020. Lifestyle adaptations of Rhizobium from rhizosphere to symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117:23823–23834. 10.1073/pnas.2009094117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Noel KD, Vandenbosch KA, Kulpaca B. 1986. Mutations in Rhizobium phaseoli that lead to arrested development of infection threads. J Bacteriol 168:1392–1401. 10.1128/jb.168.3.1392-1401.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Finan TM, Hirsch AM, Leigh JA, Johansen E, Kuldau GA, Deegan S, Walker GC, Signer ER. 1985. Symbiotic mutants of Rhizobium meliloti that uncouple plant from bacterial differentiation. Cell 40:869–877. 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng HP, Walker GC. 1998. Succinoglycan is required for initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 180:5183–5191. 10.1128/JB.180.19.5183-5191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelly SJ, Muszyński A, Kawaharada Y, Hubber AM, Sullivan JT, Sandal N, Carlson RW, Stougaard J, Ronson CW. 2013. Conditional requirement for exopolysaccharide in the Mesorhizobium-Lotus symbiosis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 26:319–329. 10.1094/MPMI-09-12-0227-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scheidle H, Gross A, Niehaus K. 2005. The lipid A substructure of the Sinorhizobium meliloti lipopolysaccharides is sufficient to suppress the oxidative burst in host plants. New Phytol 165:559–565. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stacey G, So J-S, Roth EL, Lakshmi B, Carlson RW. 1991. A lipopolysaccharide mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum that uncouples plant from bacterial differentiation. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 4:332–340. 10.1094/mpmi-4-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jones KM, Sharopova N, Lohar DP, Zhang JQ, VandenBosch KA, Walker GC. 2008. Differential response of the plant Medicago truncatula to its symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti or an exopolysaccharide-deficient mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:704–709. 10.1073/pnas.0709338105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wells DH, Long SR. 2002. The Sinorhizobium meliloti stringent response affects multiple aspects of symbiosis. Mol Microbiol 43:1115–1127. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krol E, Becker A. 2011. ppGpp in Sinorhizobium meliloti: biosynthesis in response to sudden nutritional downshifts and modulation of the transcriptome. Mol Microbiol 81:1233–1254. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wippel K, Long SR. 2016. Contributions of Sinorhizobium meliloti transcriptional regulator DksA to bacterial growth and efficient symbiosis with Medicago sativa. J Bacteriol 198:1374–1383. 10.1128/JB.00013-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gaworzewska ET, Carlile MJ. 1982. Positive chemotaxis of Rhizobium leguminosarum and other bacteria towards root exudates from legumes and other plants. J Gen Microbiol 128:1179–1188. 10.1099/00221287-128-6-1179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haichar FEZ, Santaella C, Heulin T, Achouak W. 2014. Root exudates mediated interactions belowground. Soil Biol Biochem 77:69–80. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marchetti M, Capela D, Glew M, Cruveiller S, Chane-Woon-Ming B, Gris C, Timmers T, Poinsot V, Gilbert LB, Heeb P, Medigue C, Batut J, Masson-Boivin C. 2010. Experimental evolution of a plant pathogen into a legume symbiont. PLoS Biol 8:e1000280. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marchetti M, Jauneau A, Capela D, Remigi P, Gris C, Batut J, Masson-Boivin C. 2014. Shaping bacterial symbiosis with legumes by experimental evolution. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 27:956–964. 10.1094/MPMI-03-14-0083-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Capela D, Marchetti M, Clerissi C, Perrier A, Guetta D, Gris C, Valls M, Jauneau A, Cruveiller S, Rocha EPC, Masson-Boivin C. 2017. Recruitment of a lineage-specific virulence regulatory pathway promotes intracellular infection by a plant pathogen experimentally evolved into a legume symbiont. Mol Biol Evol 34:2503–2521. 10.1093/molbev/msx165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tang M, Bouchez O, Cruveiller S, Masson-Boivin C, Capela D. 2020. Modulation of quorum sensing as an adaptation to nodule cell infection during experimental evolution of legume symbionts. mBio 11:e03129-19. 10.1128/mBio.03129-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Andrews M, De Meyer S, James EK, Stępkowski T, Hodge S, Simon MF, Young JPW. 2018. Horizontal transfer of symbiosis genes within and between rhizobial genera: occurrence and importance. Genes (Basel) 9:321. 10.3390/genes9070321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sullivan JT, Patrick HN, Lowther WL, Scott DB, Ronson CW. 1995. Nodulating strains of Rhizobium loti arise through chromosomal symbiotic gene transfer in the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:8985–8989. 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sullivan JT, Ronson CW. 1998. Evolution of rhizobia by acquisition of a 500-kb symbiosis island that integrates into a phe-tRNA gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:5145–5149. 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haskett TL, Ramsay JP, Bekuma AA, Sullivan JT, O’Hara GW, Terpolilli JJ. 2017. Evolutionary persistence of tripartite integrative and conjugative elements. Plasmid 92:30–36. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.López-Guerrero MG, Ormeño-Orrillo E, Acosta JL, Mendoza-Vargas A, Rogel MA, Ramírez MA, Rosenblueth M, Martínez-Romero J, Martínez-Romero E. 2012. Rhizobial extrachromosomal replicon variability, stability and expression in natural niches. Plasmid 68:149–158. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Westhoek A, Field E, Rehling F, Mulley G, Webb I, Poole PS, Turnbull LA. 2017. Policing the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis: a critical test of partner choice. Sci Rep 7:1419. 10.1038/s41598-017-01634-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Checcucci A, DiCenzo GC, Bazzicalupo M, Mengoni A. 2017. Trade, diplomacy, and warfare: the quest for elite rhizobia inoculant strains. Front Microbiol 8:2207. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dwivedi SL, Sahrawat KL, Upadhyaya HD, Mengoni A, Galardini M, Bazzicalupo M, Biondi EG, Hungria M, Kaschuk G, Blair MW, Ortiz R. 2015. Advances in host plant and Rhizobium genomics to enhance symbiotic nitrogen fixation in grain legumes. Adv Agron 129:1–116. 10.1016/bs.agron.2014.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pastor-Bueis R, Sanchez-Canizares C, James EK, Gonzalez-Andres F. 2019. Formulation of a highly effective inoculant for common bean based on an autochthonous elite strain of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. phaseoli, and genomic-based insights into its agronomic performance. Front Microbiol 10:2724. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mendoza-Suárez MA, Geddes BA, Sanchez-Canizares C, Ramirez-Gonzalez RH, Kirchhelle C, Jorrin B, Poole PS. 2020. Optimizing Rhizobium-legume symbioses by simultaneous measurement of rhizobial competitiveness and N2 fixation in nodules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117:9822–9831. 10.1073/pnas.1921225117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Couzigou JM, Mondy S, Sahl L, Gourion B, Ratet P. 2013. To be or noot to be: evolutionary tinkering for symbiotic organ identity. Plant Signal Behav 8:e24969. 10.4161/psb.24969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Benezech C, Berrabah F, Jardinaud MF, Le Scornet A, Milhes M, Jiang G, George J, Ratet P, Vailleau F, Gourion B. 2020. Medicago-Sinorhizobium-Ralstonia co-infection reveals legume nodules as pathogen confined infection sites developing weak defenses. Curr Biol 30:351–358.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vercruysse M, Fauvart M, Beullens S, Braeken K, Cloots L, Engelen K, Marchal K, Michiels J. 2011. A comparative transcriptome analysis of Rhizobium etli bacteroids: specific gene expression during symbiotic nongrowth. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24:1553–1561. 10.1094/MPMI-05-11-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Peng J, Hao B, Liu L, Wang S, Ma B, Yang Y, Xie F, Li Y. 2014. RNA-Seq and microarrays analyses reveal global differential transcriptomes of Mesorhizobium huakuii 7653R between bacteroids and free-living cells. PLoS One 9:e93626. 10.1371/journal.pone.0093626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tsukada S, Aono T, Akiba N, Lee KB, Liu CT, Toyazaki H, Oyaizu H. 2009. Comparative genome-wide transcriptional profiling of Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 grown under free-living and symbiotic conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5037–5046. 10.1128/AEM.00398-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barnett MJ, Toman CJ, Fisher RF, Long SR. 2004. A dual-genome symbiosis chip for coordinate study of signal exchange and development in a prokaryote-host interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:16636–16641. 10.1073/pnas.0407269101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pessi G, Ahrens CH, Rehrauer H, Lindemann A, Hauser F, Fischer HM, Hennecke H. 2007. Genome-wide transcript analysis of Bradyrhizobium japonicum bacteroids in soybean root nodules. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20:1353–1363. 10.1094/MPMI-20-11-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ogden AJ, Gargouri M, Park J, Gang DR, Kahn ML. 2017. Integrated analysis of zone-specific protein and metabolite profiles within nitrogen-fixing Medicago truncatula-Sinorhizobium medicae nodules. PLoS One 12:e0180894. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karunakaran R, Ramachandran VK, Seaman JC, East AK, Mouhsine B, Mauchline TH, Prell J, Skeffington A, Poole PS. 2009. Transcriptomic analysis of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae in symbiosis with host plants Pisum sativum and Vicia cracca. J Bacteriol 191:4002–4014. 10.1128/JB.00165-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Green RT, East AK, Karunakaran R, Downie JA, Poole PS. 2019. Transcriptomic analysis of Rhizobium leguminosarum bacteroids in determinate and indeterminate nodules. Microb Genom 5:e000254. 10.1099/mgen.0.000254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lamouche F, Gully D, Chaumeret A, Nouwen N, Verly C, Pierre O, Sciallano C, Fardoux J, Jeudy C, Szücs A, Mondy S, Salon C, Nagy I, Kereszt A, Dessaux Y, Giraud E, Mergaert P, Alunni B. 2019. Transcriptomic dissection of Bradyrhizobium sp. strain ORS285 in symbiosis with Aeschynomene spp. inducing different bacteroid morphotypes with contrasted symbiotic efficiency. Environ Microbiol 21:3244–3258. 10.1111/1462-2920.14292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li Y, Tian CF, Chen WF, Wang L, Sui XH, Chen WX. 2013. High-resolution transcriptomic analyses of Sinorhizobium sp. NGR234 bacteroids in determinate nodules of Vigna unguiculata and indeterminate nodules of Leucaena leucocephala. PLoS One 8:e70531. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roux B, Rodde N, Jardinaud M-F, Timmers T, Sauviac L, Cottret L, Carrère S, Sallet E, Courcelle E, Moreau S, Debellé F, Capela D, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Gouzy J, Bruand C, Gamas P. 2014. An integrated analysis of plant and bacterial gene expression in symbiotic root nodules using laser-capture microdissection coupled to RNA sequencing. Plant J 77:817–837. 10.1111/tpj.12442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Koch M, Delmotte N, Rehrauer H, Vorholt JA, Pessi G, Hennecke H. 2010. Rhizobial adaptation to hosts, a new facet in the legume root-nodule symbiosis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 23:784–790. 10.1094/MPMI-23-6-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Capela D, Filipe C, Bobik C, Batut J, Bruand C. 2006. Sinorhizobium meliloti differentiation during symbiosis with alfalfa: a transcriptomic dissection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19:363–372. 10.1094/MPMI-19-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Galperin MY, Kristensen DM, Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. 2019. Microbial genome analysis: the COG approach. Brief Bioinform 20:1063–1070. 10.1093/bib/bbx117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Terpolilli JJ, Masakapalli SK, Karunakaran R, Webb IU, Green R, Watmough NJ, Kruger NJ, Ratcliffe RG, Poole PS. 2016. Lipogenesis and redox balance in nitrogen-fixing pea bacteroids. J Bacteriol 198:2864–2875. 10.1128/JB.00451-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hauser F, Pessi G, Friberg M, Weber C, Rusca N, Lindemann A, Fischer HM, Hennecke H. 2007. Dissection of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum NifA+s54 regulon, and identification of a ferredoxin gene (fdxN) for symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Mol Genet Genomics 278:255–271. 10.1007/s00438-007-0246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Glöer J, Thummer R, Ullrich H, Schmitz RA. 2008. Towards understanding the nitrogen signal transduction for nif gene expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. FEBS J 275:6281–6294. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sciotti MA, Chanfon A, Hennecke H, Fischer HM. 2003. Disparate oxygen responsiveness of two regulatory cascades that control expression of symbiotic genes in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol 185:5639–5642. 10.1128/JB.185.18.5639-5642.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rutten PJ, Steel H, Hood GA, McMurtry L, Geddes B, Papachristodoulou A, Poole PS. 2020. A multi-sensor system provides spatiotemporal oxygen regulation of gene expression in a Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.09.09.289140:2020.09.09.289140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Fischer HM. 1994. Genetic regulation of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microbiol Rev 58:352–386. 10.1128/MMBR.58.3.352-386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Batut J, Boistard P. 1994. Oxygen control in Rhizobium. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 66:129–150. 10.1007/BF00871636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Terpolilli JJ, Hood GA, Poole PS. 2012. What determines the efficiency of N2-fixing Rhizobium-legume symbioses? Adv Microb Physiol 60:325–389. 10.1016/B978-0-12-398264-3.00005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rutten PJ, Poole PS. 2019. Oxygen regulatory mechanisms of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Adv Microb Physiol 75:325–389. 10.1016/bs.ampbs.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sullivan JT, Brown SD, Ronson CW. 2013. The NifA-RpoN regulon of Mesorhizobium loti strain R7A and its symbiotic activation by a novel LacI/GalR-family regulator. PLoS One 8:e53762. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Udvardi M, Poole PS. 2013. Transport and metabolism in legume-rhizobia symbioses. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64:781–805. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Brigido C, Robledo M, Menendez E, Mateos PF, Oliveira S. 2012. A ClpB chaperone knockout mutant of Mesorhizobium ciceri shows a delay in the root nodulation of chickpea plants. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 25:1594–1604. 10.1094/MPMI-05-12-0140-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fischer HM, Schneider K, Babst M, Hennecke H. 1999. GroEL chaperonins are required for the formation of a functional nitrogenase in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Arch Microbiol 171:279–289. 10.1007/s002030050711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ogawa J, Long SR. 1995. The Rhizobium meliloti groELc locus is required for regulation of early nod genes by the transcription activator NodD. Genes Dev 9:714–729. 10.1101/gad.9.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]