ABSTRACT

Invasive yeast infections represent a major global public health issue, and only few antifungal agents are available. Azoles are one of the classes of antifungals used for treatment of invasive candidiasis. The determination of antifungal susceptibility profiles using standardized methods is important to identify resistant isolates and to uncover the potential emergence of intrinsically resistant species. Here, we report data on 9,319 clinical isolates belonging to 40 pathogenic yeast species recovered in France over 17 years. The antifungal susceptibility profiles were all determined at the National Reference Center for Invasive Mycoses and Antifungals based on the EUCAST broth microdilution method. The centralized collection and analysis allowed us to describe the trends of azole susceptibility of isolates belonging to common species, confirming the high susceptibility for Candida albicans (n = 3,295), Candida tropicalis (n = 641), and Candida parapsilosis (n = 820) and decreased susceptibility for Candida glabrata (n = 1,274) and Pichia kudriavzevii (n = 343). These profiles also provide interesting data concerning azole susceptibility of Cryptococcus neoformans species complex, showing comparable MIC distributions for the three species but lower MIC50s and MIC90s for serotype D (n = 208) compared to serotype A (n = 949) and AD hybrids (n = 177). Finally, these data provide useful information for rare and/or emerging species, such as Clavispora lusitaniae (n = 221), Saprochaete clavata (n = 184), Meyerozyma guilliermondii complex (n = 150), Candida haemulonii complex (n = 87), Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (n = 55), and Wickerhamomyces anomalus (n = 36).

KEYWORDS: EUCAST, antifungal susceptibility testing, azoles, candidemia, uncommon yeast

INTRODUCTION

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) represent a major worldwide public health issue, with an incidence of 5.9 to 20.3 cases/100,000 patients per year in France, up to 27.2/100,000 in the United States, and 14.1/100,000 in the United Kingdom (1–5). Despite treatment, mortality remains high, ranging from 7.5 to 27.6%, with an estimation of 1.5 million deaths annually (6). Yeasts are the main causative agents of these infections, and only a few antifungals are effective against the most common ascomycetous yeasts and even fewer against basidiomycetous yeasts. The azoles are the largest class of antifungal agents used for treatment of IFIs, especially fluconazole for treatment of candidemia (7, 8). Azoles inhibit the 14-α-lanosterol demethylase (Cyp51), resulting in depletion of ergosterol synthesis, a major component of the fungal cell wall and in accumulation of toxic 14-α-demethylated sterols in the membrane (9). The determination of in vitro antifungal susceptibility allows determination of the wild-type population and those fungi with acquired or mutational resistance to the drug. Therefore, epidemiological surveys and standardized methods of antifungal susceptibility testing are important to confirm or not that the antifungal susceptibility of a given species remains unchanged or stable. Among internationally recognized standards, two broth microdilution methods are well standardized by the EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) and the CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute) for determining MICs. Expert committees in both instances establish breakpoints (BPs) and epidemiological cutoff values (abbreviated “ECOFFs” for EUCAST and “ECVs” for CLSI) in order to easily distinguish between susceptible and resistant and wild-type and non-wild-type (NWT) isolates, respectively. BPs are defined for a limited number of species and antifungal agents based on MIC distributions, clinical data, and the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the drugs, while ECOFFs are determined based only on MIC distributions. An ECOFF corresponds to the MIC that separates a population of isolates into wild-type and non-wild type. Unlike the BP, the ECOFF does not necessarily predict clinical failure, but it can be helpful for clinical decisions (see SOP10.1 at https://eucast.org/documents/sops/) (10). The EUCAST Antifungal Susceptibility Testing subcommittee (EUCAST-AFST) regularly updates data concerning MIC distributions and ECOFFs for species frequently involved in human infections based on data generated by more than 15 European centers (http://www.eucast.org/astoffungi/clinicalbreakpointsforantifungals/) (11). Furthermore, all over the world, mono- or multicentric studies provide reports adding to the knowledge on antifungal susceptibility profiles—mostly of common yeast species (12–20). For rare species, however, obtaining robust data is difficult given the low number of reported cases (12). Centralized data are therefore important for these species to determine their normal susceptibility profiles (10).

The French National Reference Center for Invasive Fungal Infections and Antifungals (NRCMA) provides antifungal susceptibility testing results using the EUCAST method for all the isolates collected through its missions of expertise on pathogenic fungi and surveillance of IFIs in France. Here, we report the results obtained for azoles for more than 9,000 clinical isolates belonging to 40 different species collected nationwide in France between 2003 and 2019. These data provide an overview of the susceptibility to azoles of frequent and rare pathogenic yeast species in France.

RESULTS

A total of 9,319 yeast isolates were included in the analysis. These isolates, received at the NRCMA between 1 September 2003 and 31 December 2019, were mainly involved in IFIs (80.8%: 6,853 recovered from blood cultures and 679 from cerebrospinal fluids or brain abscess cultures). The isolates belonged to 40 different species: 32/40 were ascomycetes corresponding to 17 genera, and 8/40 were basidiomycetes belonging to 4 genera. Eleven species were represented by more than 100 isolates: Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Pichia kudriavzevii (syn. Candida krusei) and Cryptococcus neoformans complex followed by Clavispora lusitaniae, Kluyveromyces marxianus, Saprochaete clavata, Candida dubliniensis, and Meyerozyma guilliermondii (Table 1). MIC ranges, MIC50s, and MIC90s for fluconazole, voriconazole and posaconazole are listed in Table 1, while MIC distributions are presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Of note, while the median MIC values for each batch of quality control (QC) strains (ATCC 22019 and ATCC 6258) were always in the range of acceptable MICs defined by EUCAST-AFST for fluconazole and voriconazole, they were 1 dilution higher for posaconazole between 2011 and 2015. However, the proportion of posaconazole-resistant isolates (MIC > 0.06 mg/liter) was not higher at that time (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Azole susceptibility profiles of 9,319 clinical isolates recovered at the NRCMA between 1 September 2003 and 31 December 2019

| Speciesa | No. of isolates | Site of isolation (n)b |

Fluconazolec |

Posaconazolec |

Voriconazolec |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood culture | CSF | MIC (mg/liter) |

% (n) |

MIC (mg/liter) |

% (n) |

MIC (mg/liter) |

% (n) |

|||||||||||

| 50% | 90% | Range | R or NWT | S | 50% | 90% | Range | R | S | 50% | 90% | Range | R or NWT | S | ||||

| Candida albicans | 3,295 | 2,763 | 15 | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.125–≥64 | 2.1 (70) | 97.5 (3211) | 0.03 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–2 | 4.2 (140) | 95.8 (3155) | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015–≥8 | 1.9 (65) | 97.3 (3203) |

| Candida dubliniensis | 135 | 107 | 2 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 | ≤0.125–16 | 1.5 (2) | 98.5 (132) | 0.03 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.125 | 5.2 (7) | 94.2 (128) | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015–0.125 | 0 | 99.3 (134) |

| Candida tropicalis | 641 | 527 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | ≤0.125–≥64 | 7.3 (47) | 88.3 (566) | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–≥8 | 27.3 (175) | 72.7 (466) | 0.03 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–≥8 | 9.5 (61) | 87.7 (562) |

| Candida parapsilosis | 820 | 708 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.25–≥64 | 6.3 (52) | 90.1 (739) | 0.06 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 23.9 (196) | 76.1 (624) | ≤0.015 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–1 | 2.2 (18) | 95.5 (783) |

| Candida orthopsilosis | 49 | 39 | 0.5 | 8 | ≤0.125–32 | 12.2 (6) | 85.7 (42) | 0.06 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 0.03 | 1 | ≤0.015–4 | |||||

| Candida metapsilosis | 45 | 34 | 1 | 2 | 0.5–8 | 2.2 (1) | 95.6 (43) | 0.03 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.125 | 0.03 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.06 | |||||

| Lodderomyces elongisporus | 7 | 2 | ≤0.125–0.5 | 0.03–0.125 | ≤0.015–≤0.015 | |||||||||||||

| Candida glabrata | 1,274 | 1,050 | 1 | 16 | ≥64 | 1–≥64 | 32.4 (413) | 0.5 | 2 | 0.06–≥8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.03–≥8 | 9.6 (122) | NA | |||

| Candida nivariensis | 13 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 1–8 | 7.7 (1) | 38.5 (5) | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.06–0.5 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.03–0.25 | |||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 61 | 51 | 8 | 16 | ≤0.125–32 | 0.5 | 1 | ≤0.015–4 | 0.125 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–1 | |||||||

| Candida haemulonii | 43 | 20 | 1 | 32 | ≥64 | 4–≥64 | 95.3 (41) | 0 | 4 | ≥8 | 0.125–≥8 | ≥8 | ≥8 | 0.125–≥8 | ||||

| Candida duobushaemulonii | 44 | 19 | 32 | ≥64 | 2–≥64 | 97.7 (43) | 2.3 (4) | 1 | ≥8 | ≤0.015–≥8 | ≥8 | ≥8 | 0.06–≥8 | |||||

| Candida auris | 7 | 8–≥64 | 100 (7) | 0 | ≤0.015–0.125 | 0.06–2 | ||||||||||||

| Clavispora lusitaniae | 221 | 171 | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.125–32 | 0.03 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.25 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015–0.5 | 4.5 (10) | NA | |||||

| Debaryomyces hansenii | 5 | 1 | ≤0.125–8 | 0.06–0.25 | ≤0.015–0.03 | |||||||||||||

| Meyerozyma guilliermondii | 115 | 73 | 1 | 8 | ≥64 | 1–≥64 | 20 (23) | NA | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03–2 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.03–≥8 | 13.9 (16) | NA | ||

| Meyerozyma caribbica | 35 | 23 | 8 | ≥64 | 1–≥64 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03–≥8 | 0.125 | 2 | 0.03–≥8 | |||||||

| Candida palmioleophila | 20 | 8 | 8 | 32 | 0.5–≥64 | 90 (18) | 5 (1) | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.06–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–2 | |||||

| Pichia cactophila | 45 | 36 | 16 | 32 | 4–≥64 | 97.8 (44) | 0 | 0.125 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.5 | ≤0.015–1 | |||||

| Pichia kudriavzevii | 343 | 262 | 32 | ≥64 | 8–≥64 | 26.8 (92) | NA | 0.125 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06–4 | 2.6 (9) | NA | |||

| Pichia norvegensis | 19 | 7 | 32 | ≥64 | 8–≥64 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.03–0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06–0.5 | |||||||

| Kluyveromyces marxianus | 170 | 133 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.125–16 | 0.06 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.5 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015–0.25 | ||||||

| Wickerhamomyces anomalus | 36 | 22 | 2 | 4 | 0.5–8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06–1 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.03–1 | |||||||

| Wickerhamiella pararugosa | 9 | 5 | 4–16 | 0.06–0.125 | ≤0.015–0.25 | |||||||||||||

| Kodamaea ohmeri | 32 | 25 | 4 | 16 | 1–≥64 | 0.03 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 0.03 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.25 | |||||||

| Kazachstania bovina | 5 | 2 | 2–8 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 0.03–0.125 | |||||||||||||

| Cyberlindnera jadinii | 23 | 18 | 1 | 4 | 0.5–16 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.03–2 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.03–1 | |||||||

| Cyberlindnera fabianii | 10 | 5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25–2 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.03–0.25 | ≤0.015 | 0.03 | ≤0.015–0.03 | |||||||

| Saprochaete clavata | 184 | 101 | 2 | 16 | ≥64 | 0.25–≥64 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.03–≥8 | 0.5 | 1 | ≤0.015–≥8 | ||||||

| Magnusiomyces capitatus | 56 | 35 | 8 | 16 | ≤0.125–32 | 0.125 | 1 | ≤0.015–2 | 0.06 | 0.5 | ≤0.015–1 | |||||||

| Galactomyces candidus | 36 | 1 | 16 | ≥64 | 0.5–≥64 | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.015–≥8 | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.015–4 | |||||||

| Yarrowia lipolytica | 27 | 13 | 4 | 16 | ≤0.125–16 | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.015–1 | 0.06 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.25 | |||||||

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii (serotype A) | 949 | 363 | 479 | 4 | 8 | ≤0.125–≥64 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–0.5 | 0.03 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–1 | ||||||

| Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans (serotype D) | 208 | 67 | 80 | 1 | 4 | ≤0.125–16 | 0.03 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–0.5 | ≤0.015 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.25 | ||||||

| Cryptococcus neoformans AD | 177 | 61 | 78 | 4 | 8 | ≤0.125–≥64 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–1 | 0.03 | 0.125 | ≤0.015–1 | ||||||

| Cryptococcus gattii | 29 | 2 | 14 | 8 | 16 | 1–32 | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.015–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | ≤0.015–1 | ||||||

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | 55 | 47 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 1–≥64 | 1 | 2 | ≤0.015–≥8 | 2 | 4 | ≤0.015–≥8 | |||||||

| Trichosporon asahii | 59 | 35 | 1 | 4 | 16 | 0.25–≥64 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03–1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–1 | ||||||

| Trichosporon inkin | 10 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0.25–16 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ≤0.015–0.5 | ≤0.015 | 0.06 | ≤0.015–0.25 | |||||||

| Cutaneotrichosporon dermatis | 7 | 4 | 1–≥64 | ≤0.015–0.125 | ≤0.015–0.125 | |||||||||||||

| Total | 9319 | 6853 | 679 | |||||||||||||||

The ascomycetous species are first listed, with C. albicans in the first position because this is the species most frequently involved in invasive human infections. Then, all species belonging to the Candida albicans/Lodderomyces clade are listed, followed by clades from the same family, then other families, and finally the basidiomycetous species, starting with the species most frequently found in human infection (Cr. neoformans). This order was chosen rather than alphabetical order or ranking by number of isolates because phylogenetically related species are thus grouped. This allows better visual recognition that species of the same clade or “complex” have similar antifungal susceptibility.

Shown are the number of isolates obtained in blood culture and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

In the MIC columns, 50% and 90% represent the MIC50 and MIC90, respectively. Other abbreviations: R, resistant (isolate MIC is >MIC breakpoint [BP] value); S, susceptible (isolate MIC is ≤BP value); NWT, non-wild type (isolate MIC is >ECOFF value, available for C. glabrata, C. guilliermondii, C. krusei, and C. lusitaniae); NA, not applicable.

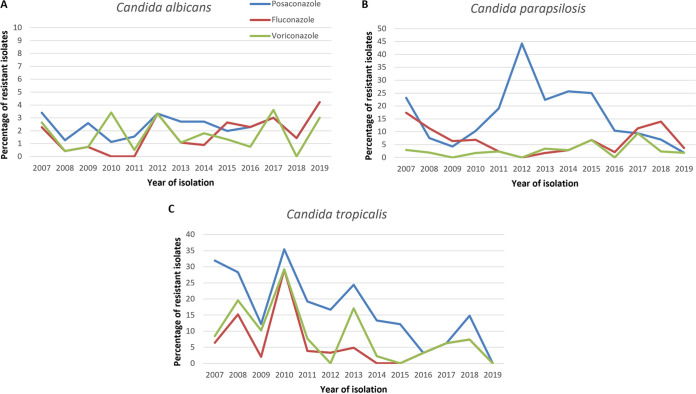

FIG 1.

Percentages of fluconazole-, voriconazole-, and posaconazole-resistant isolates, according to the year of isolation, for Candida albicans (A), Candida parapsilosis (B), and Candida tropicalis (C). For C. albicans, since the proportions of resistant isolates are similar for posaconazole and fluconazole between 2016 and 2019, the lines are overlaid. For C. parapsilosis (B) and C. tropicalis (C), the voriconazole and fluconazole lines between 2015 and 2019 are overlaid.

We first compared the MIC distributions recorded at the NRCMA to those available in the EUCAST data set. For fluconazole and voriconazole, MIC ranges were similar or with a maximum variation of 2 dilutions. Medians of MICs were equal or with a maximum of a 1-dilution difference for C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. glabrata, C parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, P. kudriavzevii, W. anomalus, K. marxianus, C. lusitaniae, and M. guilliermondii (data not shown). For posaconazole, MIC distributions were also similar, except for C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and M. guilliermondii (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), with a median MIC value for the NRCMA data set 2 dilutions higher than that for the EUCAST data set.

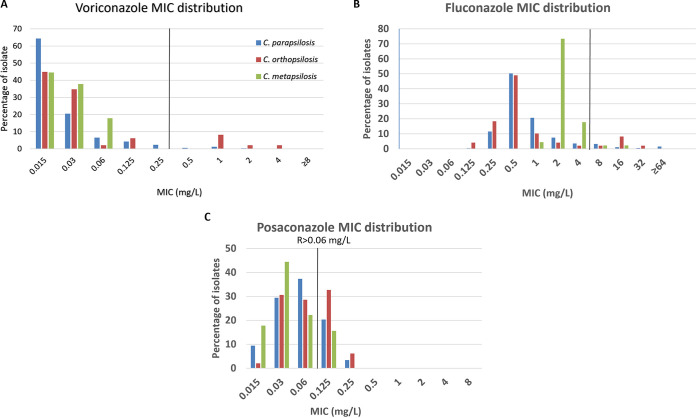

Among members of Candida parapsilosis complex, the three species had similar MIC distribution for posaconazole, while C. metapsilosis isolates had lower MICs for voriconazole and fluconazole but a higher MIC50 for fluconazole than C. parapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis. Using the EUCAST BP for fluconazole (resistant [R] > 4mg/liter), C. orthopsilosis has the highest number of resistant isolates (12.2%) (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

MIC distribution of Candida parapsilosis complex isolates for (A) voriconazole, (B) fluconazole, and (C) posaconazole. EUCAST breakpoint values for resistance (R) for C. parapsilosis sensu stricto are indicated in the graphs.

For Cr. neoformans, the MIC ranges, MIC50s, and MIC90s were determined for serotype A, serotype D, and AD hybrids. The distributions of MICs were comparable for the three species, but for the three azoles, serotype D isolates exhibited lower MIC50s and MIC90s than serotype A isolates and the AD hybrids (Table 1; Table S1).

Using the EUCAST breakpoints (BPs) for fluconazole, 32.4% of C. glabrata isolates were resistant (R > 16mg/liter), compared to less than 7.5% of the isolates for all of the other common species (R > 4 mg/liter) (Table 1). Using the non-species-related BP defined by EUCAST for fluconazole (R > 4 mg/liter), four species (C. haemulonii, C. duobushaemulonii, C. palmioleophila, and C. auris) had more than 90% of resistant isolates, while three others (C. metapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. nivariensis) had 2.2, 12.2, and 7.7% of fluconazole-resistant isolates, respectively. According to the BPs for posaconazole (R > 0.25 mg/liter) and voriconazole (R > 0.06 mg/liter), the percentages of resistant isolates were 23.9 and 2.2% for C. parapsilosis and 27.3 and 9.5% for C. tropicalis, respectively (Table 1).

According to the EUCAST ECOFF, 26.8% of P. kudriavzevii (ECOFF = 128 mg/liter) and 20% of M. guilliermondii (ECOFF = 16 mg/liter) isolates were considered non-wild type for fluconazole. Likewise, 9.6% of C. glabrata (ECOFF = 1 mg/liter), 4.5% of C. lusitaniae (ECOFF = 0.06 mg/liter), 13.9% of M. guilliermondii (ECOFF = 0.25 mg/liter), and 2.6% of P. kudriavzevii (ECOFF = 1 mg/liter) isolates were considered non-wild type for voriconazole (Table 1).

Among the population of C. glabrata isolates, 7.9% (101/1,274) were simultaneously resistant to fluconazole and considered non-wild type for voriconazole. Among the 155 C. albicans isolates resistant to at least one azole, 49 (31.6%) were resistant to the three azoles. Cross-resistance to the three azoles was found in 0/8 C. dubliniensis, 29/192 (15.1%) C. tropicalis, and 7/236 (3.0%) C. parapsilosis isolates (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The majority (>80%) of isolates resistant to at least one azole were resistant to posaconazole. The proportion of posaconazole-resistant isolates varied according to the year of isolation for C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis (Fig. 1). This variation was correlated with variation of voriconazole resistance for C. tropicalis.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report the azole susceptibility profiles for 40 yeast species involved in IFIs based on the MIC distribution of 9,319 clinical isolates recovered in France between 2003 and 2019. We provide azole profiles for common, emerging, and rare species thanks to our varied and important collection of isolates. Our results confirm that C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis complex, K. marxianus, and C. lusitaniae can be considered susceptible in vitro to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole (14, 16, 18, 19, 21), while (i) C. neoformans complex has decreased in vitro susceptibility to fluconazole, and (ii) P. kudriavzevii and the uncommon species C. haemulonii complex, M. guilliermondii complex, P. norvegensis, S. clavata, G. candidus, and R. mucilaginosa can be considered intrinsically resistant to fluconazole (MIC90 ≥ 64mg/liter) (17, 19, 20, 22–24). Of note, C. haemulonii and C. duobushaemulonii, which belong to the same species complex and are closely related to the emerging species C. auris, can also be considered intrinsically resistant to voriconazole and posaconazole (19, 25, 26). Other uncommon species, such as S. cerevisiae, K. ohmeri, C. palmioleophila, P. cactophila, M. capitatus, Y. lipolytica, Cr. gattii, and T. asahii should be considered less susceptible in vitro to fluconazole, with an “intermediate” MIC value (MIC90 ≥ 16mg/liter) (27, 28), while voriconazole seems to be the most potent azole in vitro, which is already known for Trichosporon spp. (7, 23). When considering the C. parapsilosis complex, C. metapsilosis was the species the most sensitive in vitro to azoles, with the lowest percentage of fluconazole-resistant isolates, while C. orthopsilosis seemed to be more resistant than the other species of the complex, with the highest percentage of fluconazole-resistant isolates and the highest MIC90s for fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole (12, 19). There may be a link between the low frequency of C. metapsilosis recovered from IFIs in the literature (29) and this highest azole sensitivity. Another hypothesis proposed by Gago et al. is that C. metapsilosis has a reduced ability to produce some of the known virulence factors (30). Finally, we confirmed that the very rare species L. elongisporus and Cy. fabianii were susceptible to the three azoles, while W. anomalus, K. ohmeri, and Cy. jadinii were less susceptible to fluconazole, with “intermediate” MICs (12, 31–38).

Despite reports of azole resistance acquired after treatment, in common and rare yeast species, and descriptions of an increasing percentage of resistant isolates (39), this phenomenon remains rare (1, 16, 40, 41) or has geographical specificity (42, 43) and seems to concern especially C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, and C. parapsilosis (17). In the present study, we observed a proportion of fluconazole-resistant isolates among C. albicans and C. parapsilosis isolates similar to that reported in international surveys (17, 19, 20, 28, 44). We observed posaconazole-resistant isolates of C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis complex (23.9 and 27.3%, respectively), with a variable proportion, according to the year of isolation. The increased proportion of posaconazole-resistant C. tropicalis isolates correlated with an increased proportion of voriconazole resistance of those isolates. This heterogeneous percentage of resistant isolates in our collection remained unexplained. Indeed, we raised a few hypotheses. (i) Technical issues related to the batch of antifungal powder or RPMI medium translated into a higher median posaconazole MIC but not the MICs for the other azoles for the QC strains, but this was not associated with an increase in the proportion of posaconazole-resistant isolates in the related series. (ii) Geographic specificity and/or local outbreak could be responsible, as described, for instance, in the multicentric CHIF-Net study (19) and in a national survey in Belgium (43), but none was reported to our knowledge. (iii) Bias related to the isolates analyzed could be a factor, knowing that 22% of the isolates were sent for expert analysis following therapeutic failure and were not part of the epidemiological surveys (2, 45). However, posaconazole resistance was not restricted to the isolates sent for expert analysis.

We also report an important percentage of C. glabrata isolates resistant to fluconazole (32.4%). The proportion of C. glabrata resistant to fluconazole seems to be very heterogeneous according to the country, the center, and the year of isolation. In fact, Xiao et al. reported 10.3 to 19% of isolates were resistant in China between 2009 and 2017 (19, 20, 23), based on the CHIF-Net study, while Pfaller et al. published 0 to 28.6%, according to the year of isolation in the SENTRY study (44), Bassetti et al. reported 0 to 21.2% in the SENTRY and ARTEMIS studies, depending on the continent (46), and Borman et al. and Trouvé et al. reported 12.7 and 11.3% resistance, respectively, in national studies (28, 43). Of note, the BP values for C. glabrata were modified by the EUCAST-AFST committee in 2020, from R > 32 mg/liter to R > 16 mg/liter (11). When using the previous BP (MIC > 32 mg/liter), 18.8% of C. glabrata isolates in our collection were identified as resistant to fluconazole, which is comparable to the studies published earlier before the change of the BP threshold.

Our data confirm azole susceptibility profiles for frequent species, and to our knowledge, our study is one of the only studies to assemble MIC data for more than 40 pathogenic yeast species, mainly involved in invasive infection, including large samples of isolates, even for rare and emerging species such as C. lusitaniae (n = 221), S. clavata (n = 184), M. guilliermondii complex (n = 150), C. haemulonii complex (n = 87), R. mucilaginosa (n = 55), and W. anomalus (n = 36) (12). This emphasizes the importance of centralization of isolates for collection and analysis by National Reference Centers. Our results confirm that an antifungal susceptibility profile is associated with each species and hence the importance of accurate yeast species identification as soon as possible to infer the susceptibility profile. Of course, it goes without saying that the determination of MICs, using standardized methods, remains important for rare species and the monitoring of potential emergence of resistance, including in the context of therapeutic failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

Between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2019, a total of 9,449 yeast isolates were sent to the National Reference Center for Mycosis and Antifungals (NRCMA). We analyzed MIC data for 9,319 isolates belonging to species for which at least 5 isolates were available. The majority of the isolates were sent for expert analysis (7,358/9,319 [78.8%]; i.e., species identification, antifungal susceptibility testing) and/or as participation in epidemiological surveys. For rare species represented by 10 or fewer isolates, all isolates were recovered from different patients.

Species identification.

For all isolates, purity was checked on chromogenic medium (BBL Chromagar Candida medium; BD, GmbH) or Niger seed agar for Cryptococcus spp. Phenotypic identification was performed using carbon assimilation profiles (ID32C; bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France) before 2014 and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (MALDI Biotyper; Bruker Daltonik, GmbH) since 2014. Duplex PCR was performed to differentiate Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans (47). For all isolates, PCR and sequencing of internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1)-5.8S-ITS2 and D1D2 regions were performed, except for C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, P. kudriavzevii, and K. marxianus, for which the V9D/LS266 (48, 49) and NL1/NL4 (50) primers, respectively, were used. In addition, part of the actin gene (for C. lusitaniae [51] and Debaryomyces species [52]), part of the RPBI gene (for M. guilliermondii, M. caribbica, and C. carpophila [53]), or the IGS1 region (for Trichosporon species [54]) was sequenced. Sequences were compared to sequences of the type strain of each species and of the closely related species. The serotype was determined for Cr. neoformans isolates by PCR amplification of part of the GPA1 and PAK1 genes using a triplex PCR with primers specific for the serotype previously described (55).

Antifungal susceptibility.

MICs were determined for all isolates for 3 antifungal agents: fluconazole, provided by Pfizer, Inc., (New York, USA), Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and Alsachim (Shimadzu Group Company, France); voriconazole, provided by Pfizer and Alsachim; and posaconazole provided by SheringPlough (Merck & Co., Inc., USA) and Alsachim. The MICs were determined by the standardized broth microdilution method of EUCAST following the procedure E.DEF 7.3.2 (https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/AFST/Files/EUCAST_E_Def_7.3.2_Yeast_testing_definitive_revised_2020.pdf) in 96-well, flat bottom, clear polystyrene, sterile tissue culture plates (product no. 92096; TPP Techno Plastic Products AG, Switzerland). The concentrations tested ranged between 0.0015 and 8 mg/liter for posaconazole and voriconazole and between 0.125 and 64 mg/liter for fluconazole. QC strains (ATCC 22019 and ATCC 6258) were included in each set. The concentrations corresponding to the MIC that inhibited 50% (MIC50) and 90% (MIC90) of the isolates were determined for species with 10 or more isolates.

Our data set (MIC distribution) was compared with that available on the EUCAST website (https://mic.eucast.org/Eucast2/SearchController/search.jsp?action=init; June 2020).

The BP or ECOFF values determined by EUCAST for some species and some antifungal agents (https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/AFST/Clinical_breakpoints/AFST_BP_v10.0_200204.pdf) were used to calculate the percentages of resistant (R) and non-wild-type (NWT) isolates, respectively. Non-species-related BPs for fluconazole, defined by EUCAST (MIC > 16 mg/liter) for Candida, were also used to calculate percentages of resistant isolates for C. orthopsilosis, C. metapsilosis, C. nivariensis, C. haemulonii, C. duobushaemulonii, and C. palmioleophila. Since not all isolates were collected through unbiased epidemiological survey (7,358/9,319 [78.8%]), we did not determine the local ECOFF and reported only the percentage of resistant or non-wild-type isolates in our collection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Members of the French Mycoses Study group who contributed to the data are presented in alphabetical order of the cities. Listed are all of the French microbiologists and mycologists who sent isolates for characterization of unusual antifungal susceptibility profiles or to contribute to the ongoing surveillance program on the epidemiology of invasive fungal infections in France (YEASTS and RESSIF programs): N. Brieu, CH, Aix; T. Chouaki, C. Damiani, and A. Totet, CHU, Amiens; J. P. Bouchara and M. Pihet, CHU, Angers; S. Bland, CH, Annecy; V. Blanc, CH, Antibes; S. Branger, CH, Avignon; A. P. Bellanger and L. Million, CHU, Besançon; C. Plassart, CH, Beauvais; I. Poilane, Hôpital Jean Verdier, Bondy; I. Accoceberry, L. Delhaes, and F. Gabriel, CH, Bordeaux; A. L. Roux and V. Sivadon-Tardy, Hôpital Ambroise Paré, Boulogne Billancourt; F. Laurent, CH, Bourg en Bresse; S. Legal, E. Moalic, G. Nevez, and D. Quinio, CHU, Brest; M. Cariou, CH, Bretagne Sud; J. Bonhomme, CHU, Caen; B. Podac, CH, Chalon sur Saône; S. Lechatch, CH, Charleville-Mézières; C. Soler, Hopital d’Instruction des Armées, Clamart; P. Poirier and C. Nourrisson, CHU, Clermont Ferrand; O. Augereau, CH, Colmar; N. Fauchet, CHIC, Créteil; F. Dalles, CHU, Dijon; P. Cahen, CMC, Foch; N. Desbois and C. Miossec, CHU, Fort de France; J. L. Hermann, Hôpital Raymond Poincaré, Garches; M. Cornet, D. Maubon, and H. Pelloux, CHU, Grenoble; M. Nicolas, CHU, Guadeloupe; C. Aznar, D. Blanchet, J. F. Carod, and M. Demar, CHU, Guyane; A. Angoulvant, Hôpital Bicêtre, le Kremlin Bicêtre; C. Ciupek, CH, Le Mans; A. Gigandon, Hôpital Marie Lannelongue, Le Plessis Robinson; B. Bouteille, CH, Limoges; E. Frealle and B. Sendid, CHU, Lille; D. Dupont, J. Menotti, F. Persat, and M. Wallon, CHU, Lyon; C. Cassagne and S. Ranque, CHU, Marseille; T. Benoit-Cattin and L. Collet, CH, Mayotte; A. Fiacre, CH, Meaux; N. Bourgeois and L. Lachaud, CHU, Montpellier; M. Machouart, CHU, Nancy; P. Lepape and F. Morio, CHU, Nantes; O. Moquet, CH, Nevers; S. Lefrançois, Hôpital Américain, Neuilly; M. Sasso, CHU, Nimes; F. Reibel, GH, Nord-Essone; M. Gari-Toussaint and L. Hasseine, CHU, Nice; L. Bret and D. Poisson, CHR, Orléans; S. Brun, Hôpital Avicenne, Paris; C. Bonnal and S. Houze, Hôpital Bichat, Paris; A. Paugam, Hôpital Cochin, Paris; E. Dannaoui, HEGP, Paris; N. Ait-Ammar, F. Botterel, and R. Chouk, CHU Henri Mondor, Paris; M. E. Bougnoux and E. Sitterle, Hôpital Necker, Paris; A. Fekkar and R. Piarroux, Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris; J. Guitard and C. Hennequin, Hôpital St Antoine, Paris; M. Gits-Muselli and S. Hamane, Hôpital Saint Louis, Paris; S. Bonacorsi and P. Mariani, Hôpital Robert Debré, Paris; D. Moissenet, Hôpital Trousseau, Paris; A. Minoza, E. Perraud, and M. H. Rodier, CHU, Poitiers; G. Colonna, CH, Porto Vecchio; D. Toubas, CHU, Reims; J. P. Gangneux and F. Robert-Gangneux, CHU, Rennes; O. Belmonte, G. Hoarau, M. C. Jaffar Bandjee, J. Jaubert, S. Picot, and N. Traversier, CHU, Réunion; L. Favennec and G. Gargala, CHU, Rouen; C. Tournus, CH, St Denis; H. Raberin, CHU, St Etienne; V. Letscher Bru, CHU, Strasbourg; S. Cassaing, CHU, Toulouse; P. Patoz, CH, Tourcoing; E. Bailly and G. Desoubeaux, CHU, Tours; F. Moreau, CH, Troyes; P. Munier, CH, Valence; E. Mazars, CH, Valenciennes; O. Eloy, CH, Versailles; and E. Chachaty, Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif. We thank the following members of the NRCMA (Institut Pasteur, Paris): A. Boullié, C. Gautier, V. Geolier, C. Blanc, D. Hoinard and D. Raoux-Barbot for technical help and K. Boukris-Sitbon, F. Lanternier, A. Alanio, and D. Garcia-Hermoso for their expertise and contribution to the surveillance programs.

Funding was provided by Institut Pasteur and Santé Publique France.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

aac.02615-20-s000s1.pdf (737.6KB, pdf)

REFERENCES

- 1.Lortholary O, Renaudat C, Sitbon K, Madec Y, Denoeud-Ndam L, Wolff M, Fontanet A, Bretagne S, Dromer F, French Mycosis Study Group . 2014. Worrisome trends in incidence and mortality of candidemia in intensive care units (Paris area, 2002–2010). Intensive Care Med 40:1303–1312. 10.1007/s00134-014-3408-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bitar D, Lortholary O, Le Strat Y, Nicolau J, Coignard B, Tattevin P, Che D, Dromer F. 2014. Population-based analysis of invasive fungal infections, France, 2001–2010. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1149–1155. 10.3201/eid2007.140087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gangneux JP, Bougnoux ME, Hennequin C, Godet C, Chandenier J, Denning DW, Dupont B, LIFE Program, Societe Francaise de Mycologie Medicale SFMM-Study Group . 2016. An estimation of burden of serious fungal infections in France. J Mycol Med 26:385–390. 10.1016/j.mycmed.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pegorie M, Denning DW, Welfare W. 2017. Estimating the burden of invasive and serious fungal disease in the United Kingdom. J Infect 74:60–71. 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb BJ, Ferraro JP, Rea S, Kaufusi S, Goodman BE, Spalding J. 2018. Epidemiology and clinical features of invasive fungal infection in a US health care network. Open Forum Infect Dis 5:ofy187. 10.1093/0fid/ofy187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. 2012. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 4:165rv13. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arendrup MC, Boekhout T, Akova M, Meis JF, Cornely OA, Lortholary O, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Fungal Infection Study Group, European Confederation of Medical Mycology . 2014. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of rare invasive yeast infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 20(Suppl 3):76–98. 10.1111/1469-0691.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Schuster MG, Vazquez JA, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE, Sobel JD. 2016. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 62:e1–e50. 10.1093/cid/civ933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattacharya S, Sae-Tia S, Fries BC. 2020. Candidiasis and mechanisms of antifungal resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 9:312. 10.3390/antibiotics9060312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkow EL, Lockhart SR, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. 2020. Antifungal susceptibility testing: current approaches. Clin Microbiol Rev 33. 10.1128/CMR.00069-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arendrup MC, Friberg N, Mares M, Kahlmeter G, Meletiadis J, Guinea J, Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of the EECfAST . 2020. How to interpret MICs of antifungal compounds according to the revised clinical breakpoints v.10.0 European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borman AM, Muller J, Walsh-Quantick J, Szekely A, Patterson Z, Palmer MD, Fraser M, Johnson EM. 2020. MIC distributions for amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, flucytosine and anidulafungin and 35 uncommon pathogenic yeast species from the UK determined using the CLSI broth microdilution method. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:1194–1205. 10.1093/jac/dkz568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz-Garcia J, Alcala L, Martin-Rabadan P, Mesquida A, Sanchez-Carrillo C, Reigadas E, Munoz P, Escribano P, Guinea J. 2019. Susceptibility of uncommon Candida species to systemic antifungals by the EUCAST methodology. Med Mycol 58:848–851. 10.1093/mmy/myz121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guinea J, Zaragoza O, Escribano P, Martin-Mazuelos E, Peman J, Sanchez-Reus F, Cuenca-Estrella M. 2014. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility of yeast isolates causing fungemia collected in a population-based study in Spain in 2010 and 2011. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1529–1537. 10.1128/AAC.02155-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung IY, Jeong SJ, Kim YK, Kim HY, Song YG, Kim JM, Choi JY. 2020. A multicenter retrospective analysis of the antifungal susceptibility patterns of Candida species and the predictive factors of mortality in South Korean patients with candidemia. Medicine 99:e19494. 10.1097/MD.0000000000019494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Messer SA, Jones RN. 2015. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of isolates of Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. from China to nine systemically active antifungal agents: data from the SENTRY antifungal surveillance program, 2010 through 2012. Mycoses 58:209–214. 10.1111/myc.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Turnidge JD, Castanheira M, Jones RN. 2019. Twenty years of the SENTRY antifungal surveillance program: results for Candida species from 1997–2016. Open Forum Infect Dis 6:S79–S94. 10.1093/ofid/ofy358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Jones RN, Castanheira M. 2015. Antifungal susceptibilities of Candida, Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus from the Asia and Western Pacific region: data from the SENTRY antifungal surveillance program (2010–2012). J Antibiot (Tokyo) 68:556–561. 10.1038/ja.2015.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao M, Chen SC, Kong F, Xu XL, Yan L, Kong HS, Fan X, Hou X, Cheng JW, Zhou ML, Li Y, Yu SY, Huang JJ, Zhang G, Yang Y, Zhang JJ, Duan SM, Kang W, Wang H, Xu YC. 2020. Distribution and antifungal susceptibility of Candida species causing candidemia in China: an update from the CHIF-NET study. J Infect Dis 221:S139–S147. 10.1093/infdis/jiz573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao M, Sun ZY, Kang M, Guo DW, Liao K, Chen SC, Kong F, Fan X, Cheng JW, Hou X, Zhou ML, Li Y, Yu SY, Huang JJ, Wang H, Xu YC, China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net Study Group . 2018. Five-year national surveillance of invasive candidiasis: species distribution and azole susceptibility from the China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net (CHIF-NET) study. J Clin Microbiol 56:e00577-18. 10.1128/JCM.00577-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Astvad KMT, Hare RK, Arendrup MC. 2017. Evaluation of the in vitro activity of isavuconazole and comparator voriconazole against 2635 contemporary clinical Candida and Aspergillus isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect 23:882–887. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Hansen A, Lass-Flörl C, Lackner M, Aigner M, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arikan-Akdagli S, Bader O, Becker K, Boekhout T, Buzina W, Cornely OA, Hamal P, Kidd SE, Kurzai O, Lagrou K, Lopes Colombo A, Mares M, Masoud H, Meis JF, Oliveri S, Rodloff AC, Orth-Höller D, Guerrero-Lozano I, Sanguinetti M, Segal E, Taj-Aldeen SJ, Tortorano AM, Trovato L, Walther G, Willinger B, Rare Yeast Study Group . 2019. Antifungal susceptibility profiles of rare ascomycetous yeasts. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:2649–2656. 10.1093/jac/dkz231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao M, Chen SC, Kong F, Fan X, Cheng JW, Hou X, Zhou ML, Wang H, Xu YC, China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net Study Group . 2018. Five-year China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net (CHIF-NET) study of invasive fungal infections caused by noncandidal yeasts: species distribution and azole susceptibility. IDR 11:1659–1667. 10.2147/IDR.S173805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamiu AT, Albertyn J, Sebolai OM, Pohl CH. 2020. Update on Candida krusei, a potential multidrug-resistant pathogen. Med Mycol 10.1093/mmy/myaa031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bretagne S, Renaudat C, Desnos-Ollivier M, Sitbon K, Lortholary O, Dromer F, French Mycosis Study Group . 2017. Predisposing factors and outcome of uncommon yeast species-related fungaemia based on an exhaustive surveillance programme (2002–14). J Antimicrob Chemother 72:1784–1793. 10.1093/jac/dkx045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desnos-Ollivier M, Robert V, Raoux-Barbot D, Groenewald M, Dromer F. 2012. Antifungal susceptibility profiles of 1698 yeast reference strains revealing potential emerging human pathogens. PLoS One 7:e32278. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez-Ruiz M, Guinea J, Puig-Asensio M, Zaragoza O, Almirante B, Cuenca-Estrella M, Aguado JM, CANDIPOP Project, GEIH-GEMICOMED (SEIMC), REIPI . 2017. Fungemia due to rare opportunistic yeasts: data from a population-based surveillance in Spain. Med Mycol 55:125–136. 10.1093/mmy/myw055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borman AM, Muller J, Walsh-Quantick J, Szekely A, Patterson Z, Palmer MD, Fraser M, Johnson EM. 2019. Fluconazole resistance in isolates of uncommon pathogenic yeast species from the United Kingdom. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e00211-19. 10.1128/AAC.00211-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canton E, Peman J, Quindos G, Eraso E, Miranda-Zapico I, Alvarez M, Merino P, Campos-Herrero I, Marco F, de la Pedrosa EG, Yague G, Guna R, Rubio C, Miranda C, Pazos C, Velasco D, FUNGEMYCA Study Group . 2011. Prospective multicenter study of the epidemiology, molecular identification, and antifungal susceptibility of Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis isolated from patients with candidemia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:5590–5596. 10.1128/AAC.00466-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gago S, Garcia-Rodas R, Cuesta I, Mellado E, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. 2014. Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis virulence in the non-conventional host Galleria mellonella. Virulence 5:278–285. 10.4161/viru.26973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Obaid K, Ahmad S, Joseph L, Khan Z. 2018. Lodderomyces elongisporus: a bloodstream pathogen of greater clinical significance. New Microbes New Infect 26:20–24. 10.1016/j.nmni.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Sweih N, Ahmad S, Khan S, Joseph L, Asadzadeh M, Khan Z. 2019. Cyberlindnera fabianii fungaemia outbreak in preterm neonates in Kuwait and literature review. Mycoses 62:51–61. 10.1111/myc.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bougnoux ME, Gueho E, Potocka AC. 1993. Resolutive Candida utilis fungemia in a nonneutropenic patient. J Clin Microbiol 31:1644–1645. 10.1128/JCM.31.6.1644-1645.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutra VR, Silva LF, Oliveira ANM, Beirigo EF, Arthur VM, Bernardes da Silva R, Ferreira TB, Andrade-Silva L, Silva MV, Fonseca FM, Silva-Vergara ML, Ferreira-Paim K. 2020. Fatal case of fungemia by Wickerhamomyces anomalus in a pediatric patient diagnosed in a teaching hospital from Brazil. J Fungi (Basel) 6:147. 10.3390/jof6030147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung J, Moon YS, Yoo JA, Lim JH, Jeong J, Jun JB. 2018. Investigation of a nosocomial outbreak of fungemia caused by Candida pelliculosa (Pichia anomala) in a Korean tertiary care center. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 51:794–801. 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin HC, Lin HY, Su BH, Ho MW, Ho CM, Lee CY, Lin MH, Hsieh HY, Lin HC, Li TC, Hwang KP, Lu JJ. 2013. Reporting an outbreak of Candida pelliculosa fungemia in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 46:456–462. 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park JH, Oh J, Sang H, Shrestha B, Lee H, Koo J, Cho SI, Choi JS, Lee MH, Kim J, Sung GH. 2019. Identification and antifungal susceptibility profiles of Cyberlindnera fabianii in Korea. Mycobiology 47:449–456. 10.1080/12298093.2019.1651592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou M, Yu S, Kudinha T, Xiao M, Wang H, Xu Y, Zhao H. 2019. Identification and antifungal susceptibility profiles of Kodamaea ohmeri based on a seven-year multicenter surveillance study. Infect Drug Resist 12:1657–1664. 10.2147/IDR.S211033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arastehfar A, Lass-Florl C, Garcia-Rubio R, Daneshnia F, Ilkit M, Boekhout T, Gabaldon T, Perlin DS. 2020. The quiet and underappreciated rise of drug-resistant invasive fungal pathogens. J Fungi (Basel) 6:138. 10.3390/jof6030138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Davis AP, Rhomberg PR, Pfaller MA. 2017. Monitoring antifungal resistance in a global collection of invasive yeasts and molds: application of CLSI epidemiological cutoff values and whole-genome sequencing analysis for detection of azole resistance in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00906-17. 10.1128/AAC.00906-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lass-Florl C, Mayr A, Aigner M, Lackner M, Orth-Holler D. 2018. A nationwide passive surveillance on fungal infections shows a low burden of azole resistance in molds and yeasts in Tyrol, Austria. Infection 46:701–704. 10.1007/s15010-018-1170-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tacconelli E, Sifakis F, Harbarth S, Schrijver R, van Mourik M, Voss A, Sharland M, Rajendran NB, Rodriguez-Bano J, EPI-Net COMBACTE-MAGNET Group . 2018. Surveillance for control of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect Dis 18:e99–e106. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trouve C, Blot S, Hayette MP, Jonckheere S, Patteet S, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Symoens F, Van Wijngaerden E, Lagrou K. 2017. Epidemiology and reporting of candidaemia in Belgium: a multi-centre study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36:649–655. 10.1007/s10096-016-2841-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfaller MA, Carvalhaes CG, Smith CJ, Diekema DJ, Castanheira M. 2020. Bacterial and fungal pathogens isolated from patients with bloodstream infection: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2012–2017). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 97:115016. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lortholary O, Renaudat C, Sitbon K, Desnos-Ollivier M, Bretagne S, Dromer F, French Mycoses Study Group . 2017. The risk and clinical outcome of candidemia depending on underlying malignancy. Intensive Care Med 43:652–662. 10.1007/s00134-017-4743-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bassetti M, Vena A, Bouza E, Peghin M, Muñoz P, Righi E, Pea F, Lackner M, Lass-Flörl C. 2020. Antifungal susceptibility testing in Candida, Aspergillus and Cryptococcus infections: are the MICs useful for clinicians? Clin Microbiol Infect 26:1024–1033. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donnelly SM, Sullivan DJ, Shanley DB, Coleman DC. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis and rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis based on analysis of ACT1 intron and exon sequences. Microbiology 145:1871–1882. 10.1099/13500872-145-8-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Hoog GS, van den Ende GAH. 1998. Molecular diagnostics of clinical strains of filamentous basidiomycetes. Mycoses 41:183–189. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masclaux F, Gueho E, de Hoog GS, Christen R. 1995. Phylogenetic relationships of human-pathogenic Cladosporium (Xylohypha) species inferred from partial LS rRNA sequences. J Med Vet Mycol 33:327–338. 10.1080/02681219580000651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Donnell K. 1993. Fusarium and its near relatives, p 225–233. In Reynolds DR, Taylor JW (ed), The fungal holomorph: mitotic, meiotic and pleomorphic speciation in fungal systematics. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guzman B, Lachance MA, Herrera CM. 2013. Phylogenetic analysis of the angiosperm-floricolous insect-yeast association: have yeast and angiosperm lineages co-diversified? Mol Phylogenet Evol 68:161–175. 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martorell P, Fernandez-Espinar MT, Querol A. 2005. Sequence-based identification of species belonging to the genus Debaryomyces. FEMS Yeast Res 5:1157–1165. 10.1016/j.femsyr.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Desnos-Ollivier M, Bretagne S, Boullie A, Gautier C, Dromer F, Lortholary O, French Mycoses Study Group . 2019. Isavuconazole MIC distribution of 29 yeast species responsible for invasive infections (2015–2017). Clin Microbiol Infect 25:634.e1–634.e4. 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sugita T, Nakajima M, Ikeda R, Matsushima T, Shinoda T. 2002. Sequence analysis of the ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer 1 regions of Trichosporon species. J Clin Microbiol 40:1826–1830. 10.1128/jcm.40.5.1826-1830.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lengeler KB, Cox GM, Heitman J. 2001. Serotype AD strains of Cryptococcus neoformans are diploid or aneuploid and are heterozygous at the mating-type locus. Infect Immun 69:115–122. 10.1128/IAI.69.1.115-122.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]