ABSTRACT

In vitro antifungal susceptibility profiling of 32 clinical and environmental Talaromyces marneffei isolates recovered from southern China was performed against olorofim and 7 other systemic antifungals, including amphotericin B, 5-flucytosine, posaconazole, voriconazole, caspofungin, and terbinafine, using CLSI methodology. In comparison, olorofim was the most active antifungal agent against both mold and yeast phases of all tested Talaromyces marneffei isolates, exhibiting an MIC range, MIC50, and MIC90 of 0.0005 to 0.002 μg/ml, 0.0005 μg/ml, and 0.0005 μg/ml, respectively.

KEYWORDS: Talaromyces marneffei, olorofim

INTRODUCTION

Talaromyces (formerly Penicillium) marneffei is the etiological agent of talaromycosis (1), a life-threatening disease that affects immunocompromised hosts, especially those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (2). The fungus is a thermal dimorphic microorganism exhibiting a mycelial form at 25°C and a yeast form at 37°C. It may have a natural habitat in soil in areas of southern China (3), and Southeast Asia (including India), where it is endemic (4), and is known to be associated with bamboo rats (5) and dogs (6). Notably, the risk of infection is not restricted to those living in areas where it is endemic. HIV-infected individuals traveling to areas of endemicity have also become infected by T. marneffei (7).

Treatment of talaromycosis is typically initiated with amphotericin B, but its use is limited due to toxic side effects and requires a prolonged hospital stay (8). After completing 2 weeks of amphotericin B, patients will be transitioned to consolidation therapy with itraconazole for 10 weeks. For those who cannot take amphotericin B or itraconazole, voriconazole is recommended (8). If untreated or if there is a delay in diagnosis, the mortality rate of T. marneffei infections in HIV-infected patients is up to 100% (9). Therefore, the need for new antifungals to treat talaromycosis is urgent.

Several investigational antifungals with novel mechanisms of action that may override both the low susceptibility and adverse side effects are currently under development (10, 11). Among them, ibrexafungerp (12) and fosmagepix (13) demonstrated good in vitro activity against the Scedosporium species complex and Lomentospora prolificans. The new triazole derivative albaconazole (ALBA) (UR-9825) also showed potent activity against these pathogens in both in vitro (14) and in vivo (15) studies. Olorofim (formerly F901318) is a novel fungicidal drug that selectively inhibits fungal dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), a key enzyme in the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway (16). Olorofim has shown potent in vitro inhibitory activity against isolates of Aspergillus spp., including azole-resistant isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus (17) and cryptic aspergilli (18); the Scedosporium/Pseudallescheria species complex and Lomentospora spp. (19, 20); Madurella mycetomatis (21); certain species of Fusarium and non-marneffei Talaromyces spp. (16); as well as the dimorphic human pathogen Coccidioides species (22) using both European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) methodologies (18). The potent activity of olorofim has also been demonstrated in experimental animal models of disseminated infections caused by A. fumigatus (23, 24), Aspergillus flavus (25), Aspergillus nidulans (23), Aspergillus tanneri (23), Scedosporium apiospermum, Pseudallescheria boydii, Lomentospora prolificans (26), and Coccidioides immitis (22).

The drug is currently being investigated in phase II clinical studies for the treatment of invasive mold infections (invasive fungal infections [IFIs]) (11). In November 2019, olorofim received breakthrough therapy designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of IFIs. Currently, a phase IIb clinical trial of oral olorofim is recruiting patients with IFIs and lacking treatment options (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03583164). The in vitro efficacy of olorofim against T. marneffei has not been extensively tested yet. We therefore aimed to evaluate the susceptibility of T. marneffei to olorofim and other currently available systemic antifungals in its yeast as well as mold phases.

(This study was partially presented at the 9th Advances against Aspergillosis and Mucormycosis Conference, Lugano, Switzerland, 27 to 29 February 2020 [www.AAAM2020.org] [27], and the 30th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases [ECCMID], Paris, France, 18 to 21 April 2020 [28]).

A collection of 32 T. marneffei strains recovered from southern China was investigated, including 17 isolates of human origin, 11 animal isolates, and 4 environmental strains (Table 1). The 17 clinical strains were isolated from patients who were admitted to Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (3,000 inpatient beds with over 3.02 million outpatient visits per year), Second Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (SYSU), Guangdong, China, from 1995 to 2014. The 11 animal isolates were obtained from bamboo rats captured in the Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong provinces of China. The 4 environmental strains were isolated from bamboo root and soil in the area where bamboo rats lived. The identity of each strain was confirmed at the species level via PCR amplification and sequence-based analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) region and β-tubulin gene, as described previously (29).

TABLE 1.

Talaromyces marneffei strains tested in this study

| Origin (no. of isolates) and strain no. | GenBank accession no. | Origin of isolationa | Source of isolation | Geographical origin of isolate | Yr of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human (17) | |||||

| SUMS0047 | AB353906 | AIDS patient | Skin lesion | Guangdong | 1995 |

| SUMS0174 | AB353915 | AIDS patient | Skin lesion | Guangdong | 2002 |

| SUMS0217 | JX036541 | AIDS patient | Stool | Guangdong | 2004 |

| SUMS0304 | KR902349 | SLE patient | Bone marrow | Guangdong | 2007 |

| SUMS0326 | MN700104 | AIDS patient | Skin lesion | Guangdong | 2007 |

| SUMS0486 | JQ585633 | MM patient | Skin lesion | Guangdong | 2010 |

| SUMS0565 | MN700095 | DM patient | Skin lesion | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0573 | MN700102 | TB patient | Sputum | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0579 | MN700101 | SLE patient | Skin lesion | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0590 | MN700100 | COPD patient | Sputum | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0598 | MN700096 | AIDS patient | Blood | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0687 | MN700099 | ALL patient | Blood | Guangdong | 2012 |

| SUMS0688 | MN700097 | SLE patient | Blood | Guangdong | 2012 |

| SUMS0743 | MN700103 | AIDS patient | Blood | Guangdong | 2013 |

| SUMS0751 | KT121405 | AIDS patient | Blood | Guangdong | 2013 |

| SUMS0765 | MN700105 | AIDS patient | Blood | Guangdong | 2014 |

| SUMS0766 | MN700106 | AIDS patient | Blood | Guangdong | 2014 |

| Animal (11) | |||||

| SUMS0265 | MN700098 | Bamboo rat | Liver | Jiangxi | 2006 |

| SUMS0272 | FJ009555 | Bamboo rat | Lung | Jiangxi | 2006 |

| SUMS0347 | FJ009564 | Bamboo rat | Liver | Fujian | 2007 |

| SUMS0349 | FJ009552 | Bamboo rat | Liver | Guangdong | 2007 |

| SUMS0547 | JN679219 | Bamboo rat | Liver | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0556 | JN679223 | Bamboo rat | Lung | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0603 | JQ910936 | Bamboo rat | Liver | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0608 | JQ910941 | Bamboo rat | Liver | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0612 | JQ910945 | Bamboo rat | Liver | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0623 | JQ912271 | Bamboo rat | Liver | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0629 | JQ912277 | Bamboo rat | Spleen | Guangdong | 2011 |

| Environmental (4) | |||||

| SUMS0602 | JQ910935 | Near the bamboo rat hole | Bamboo root | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0615 | JQ910948 | Far from the bamboo rat hole | Soil | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0624 | JQ912272 | Near the bamboo rat hole | Bamboo root | Guangdong | 2011 |

| SUMS0630 | JQ912278 | Bamboo rat hole | Soil | Guangdong | 2011 |

MM, multiple myeloma; DM, dermatomycosis; TB, tuberculosis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing was performed using CLSI broth microdilution M38-ED3:2017 and M27-ED4:2017 guidelines (33, 34) for mycelial and yeast growth forms, respectively. The mold conidial suspensions were obtained from T. marneffei strains cultured on malt extract agar for 7 to 14 days at 25°C. The yeast suspensions were obtained from T. marneffei strains cultured on brain heart infusion agar for 4 to 5 days at 37°C. The drugs were provided by F2G, Ltd., Eccles, Manchester, United Kingdom (olorofim), or purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO (all other agents). The final concentration ranges of antifungal agents were 0.0313 to 16 μg/ml for amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, and terbinafine; 0.031 to 32 μg/ml for 5-flucytosine and caspofungin; and 0.00025 to 0.25 μg/ml for olorofim. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibited growth as assessed by visual inspection in comparison with the control (drug-free well). For caspofungin in mycelial-form cultures of T. marneffei only, the MEC (minimum effective concentration) was defined as the lowest concentration in which abnormal, short, and branched hyphal clusters were observed, in contrast to the long, unbranched hyphal elements that were seen in the well.

A. flavus (ATCC 204304) and A. fumigatus (ATCC 204305) were used as quality control strains in all experiments.

All experiments on each strain were performed using two independent replicates on different days. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, version 9.0, for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The MIC/MEC distributions between the isolates originating from different locations were compared using Student’s t test and the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test; differences were considered statistically significant at a P value of ≤0.05 (two tailed).

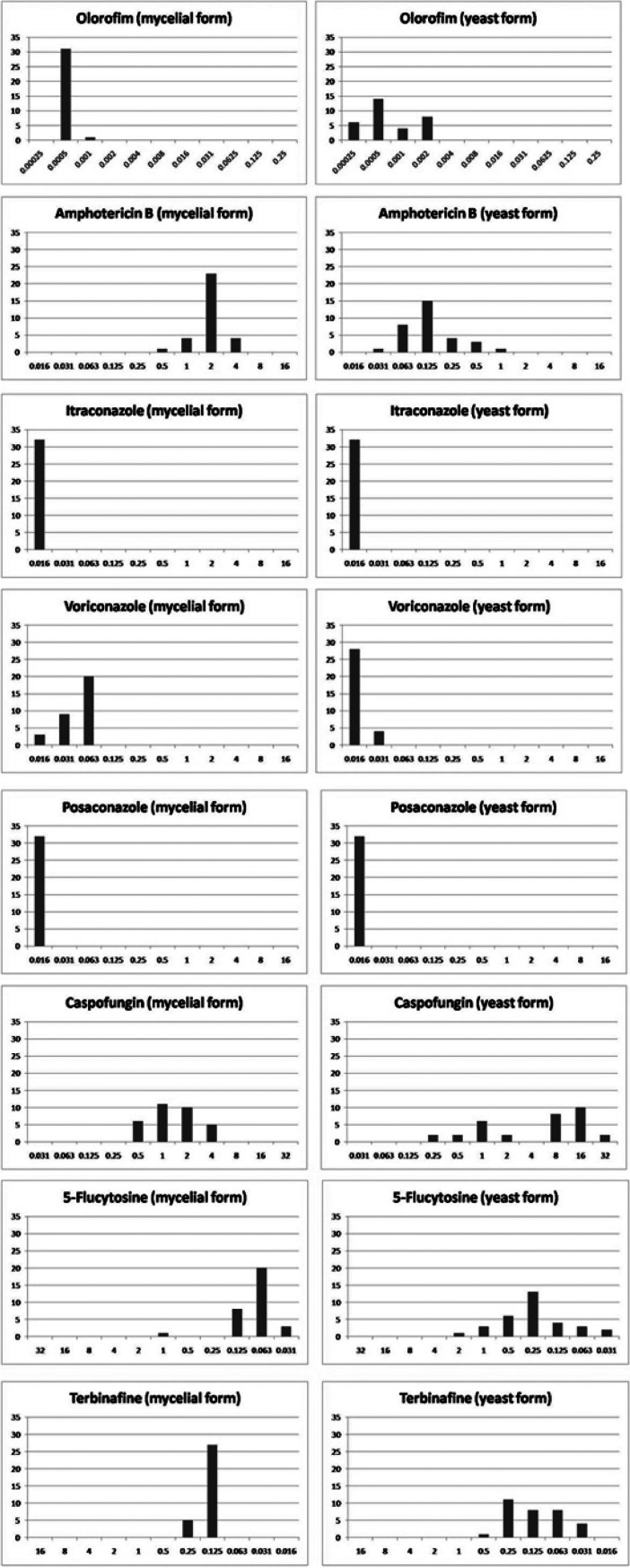

The geometric mean (GM) MICs/MECs, the MIC/MEC ranges, and the MIC50/MEC50 and MIC90/MEC90 distributions of the eight antifungals against 32 T. marneffei strains are listed in Table 2. The MIC/MEC distributions of all tested antifungals are presented in Fig. 1. In summary, the GM MICs/MECs of the antifungals against the mold growth form of all T. marneffei strains were as follows (in increasing order): 0.0005 μg/ml for olorofim, 0.016 μg/ml for itraconazole and posaconazole, 0.05 μg/ml for voriconazole, 0.08 μg/ml for 5-flucytosine, 0.1 μg/ml for terbinafine, 0.4 μg/ml for caspofungin, and 2 μg/ml for amphotericin B. The GM MICs/MECs against the yeast phase were as follows: 0.0007 μg/ml for olorofim, 0.016 μg/ml for posaconazole, 0.016 μg/ml for itraconazole, 0.017 μg/ml for voriconazole, 0.12 μg/ml for terbinafine, 0.13 μg/ml for amphotericin B, 0.25 μg/ml for 5-flucytosine, and 4.5 μg/ml for caspofungin.

TABLE 2.

In vitro susceptibility results for cultured mycelial and yeast forms of 32 Talaromyces marneffei strains against eight antifungal agents

| Strain type (no. of isolates) and drug | MIC/MEC (μg/ml)a in mycelial form |

MIC (μg/ml)a in yeast form |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC50/MEC50 | MIC90/MEC90 | Geometric mean | Range | MIC50/MEC50 | MIC90/ME90 | Geometric mean | |

| All strains (32) | ||||||||

| Olorofim | 0.0005–0.001 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.00025–0.002 | 0.0005 | 0.002 | 0.0007 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.5–4 | 2 | 4 | 1.9152 | 0.031–1 | 0.125 | 0.475 | 0.1331 |

| Itraconazole | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.0160 | ≤0.016–0.031 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.0163 |

| Voriconazole | ≤0.016–0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.0453 | ≤0.016–0.031 | 0.016 | 0.0295 | 0.0174 |

| Posaconazole | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.0160 | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.0160 |

| Caspofungin | 0.5–4 | 1 | 4 | 1.3543 | 0.25–32 | 8 | 16 | 4.5552 |

| 5-Flucytosine | 0.031–1 | 0.062 | 0.125 | 0.0755 | 0.031–2 | 0.25 | 0.95 | 0.2443 |

| Terbinafine | 0.125–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.1393 | 0.031–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.1168 |

| Clinical (17) | ||||||||

| Olorofim | 0.0005–0.001 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.00025–0.002 | 0.0005 | 0.02 | 0.0007 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.5–4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0.031–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.1252 |

| Itraconazole | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| Voriconazole | ≤0.016–0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.0419 | ≤0.016–0.031 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.0173 |

| Posaconazole | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| Caspofungin | 0.5–4 | 2 | 4 | 1.8434 | 0.25–32 | 2 | 16 | 2.6606 |

| 5-Flucytosine | 0.031–1 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.0834 | 0.031–2 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.2825 |

| Terbinafine | 0.125–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.1471 | 0.031–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.1252 |

| Animal (11) | ||||||||

| Olorofim | 0.0005–0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.00025–0.002 | 0.0005 | 0.002 | 0.0006 |

| Amphotericin B | 1–4 | 2 | 2 | 1.7631 | 0.063–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.1512 |

| Itraconazole | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | ≤0.016–0.031 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.017 |

| Voriconazole | 0.031–0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.0519 | ≤0.016–0.031 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.018 |

| Posaconazole | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| Caspofungin | 0.5–4 | 1 | 2 | 1.065 | 1–16 | 16 | 16 | 8.5203 |

| 5-Flucytosine | 0.063–0.125 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.0714 | 0.031–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.1714 |

| Terbinafine | 0.125–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.1331 | 0.031–0.25 | 0.063 | 0.25 | 0.0971 |

| Environmental (4) | ||||||||

| Olorofim | 0.0005–0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.0005–0.002 | 0.0008 | ||||

| Amphotericin B | 2–2 | 2 | 0.063–0.25 | 0.1252 | ||||

| Itraconazole | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | ||||

| Voriconazole | 0.031–0.063 | 0.0442 | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | ||||

| Posaconazole | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | ||||

| Caspofungin | 0.5–1 | 0.7071 | 2–32 | 8 | ||||

| 5-Flucytosine | 0.031–0.125 | 0.0626 | 0.125–1 | 0.3536 | ||||

| Terbinafine | 0.125–0.125 | 0.125 | 0.063–0.25 | 0.1489 | ||||

MEC, minimal effective concentration; MIC50/MEC50, minimal concentration that inhibits 50% of isolates; MIC90/MEC90, minimal concentration that inhibits 90% of isolates. MECs were used for caspofungin.

FIG 1.

MIC/MEC distributions for 32 Talaromyces marneffei strains of clinical and environmental origins. The x axis shows the MICs/MECs (in micrograms per milliliter), and the y axis shows the number of strains in the set with the given MIC/MEC.

Overall, olorofim showed the lowest MIC values among antifungals tested in both mold and yeast phases of all T. marneffei strains, independent of the source of isolation. No statistically significant differences in the olorofim susceptibility profiles were detected between the clinical and environmental isolates of T. marneffei. In several recent studies, a similar in vitro potency of olorofim was observed for several other molds (16, 17, 19–22), including non-marneffei Talaromyces species and multiazole-resistant Penicillium spp. (30). Consistent with previous reports, our study also showed that itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole were potent against all T. marneffei isolates, with higher MICs of fluconazole than other azoles (31). Caspofungin showed relatively high MICs (MIC ranges, 0.5 to 4 μg/ml and 0.25 to 32 μg/ml against mold and yeast forms, respectively) against all strains tested, which is in agreement with a previous report from China (32). For all tested strains, 5-flucytosine and terbinafine had low MIC values, whereas amphotericin B exhibited higher MIC values against the mycelial phase of all isolates (MIC range, 0.5 to 4 μg/ml). Our results agreed with a previous report (24) that the range of amphotericin B MICs for the mold phase was 0.5 to 4 μg/ml.

In conclusion, olorofim is an antimycotic that is potent against both growth phases of T. marneffei in vitro, and further studies are warranted to evaluate its in vivo efficacy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a research fund from the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and partly by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Clinical Center, Department of Laboratory Medicine.

Olorofim (F901318) powder was provided by F2G, Ltd.

We declare no conflicts of interest related to this publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

aac.00256-21-s0001.xlsx (13.6KB, xlsx)

REFERENCES

- 1.Seyedmousavi S, Guillot J, Tolooe A, Verweij PE, de Hoog GS. 2015. Neglected fungal zoonoses: hidden threats to man and animals. Clin Microbiol Infect 21:416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong SYN, Wong KF. 2011. Penicillium marneffei infection in AIDS. Patholog Res Int 2011:764293. doi: 10.4061/2011/764293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu Y, Zhang J, Li X, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Ma J, Xi L. 2013. Penicillium marneffei infection: an emerging disease in mainland China. Mycopathologia 175:57–67. doi: 10.1007/s11046-012-9577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranjana KH, Priyokumar K, Singh TJ, Gupta CC, Sharmila L, Singh PN, Chakrabarti A. 2002. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection among HIV-infected patients in Manipur state, India. J Infect 45:268–271. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanittanakom N, CooperCR, Jr, Fisher MC, Sirisanthana T. 2006. Penicillium marneffei infection and recent advances in the epidemiology and molecular biology aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev 19:95–110. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.95-110.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaiwun B, Vanittanakom N, Jiviriyawat Y, Rojanasthien S, Thorner P. 2011. Investigation of dogs as a reservoir of Penicillium marneffei in northern Thailand. Int J Infect Dis 15:e236–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Julander I, Petrini B. 1997. Penicillium marneffei infection in a Swedish HIV-infected immunodeficient narcotic addict. Scand J Infect Dis 29:320–322. doi: 10.3109/00365549709019055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sirisanthana T, Supparatpinyo K, Perriens J, Nelson KE. 1998. Amphotericin B and itraconazole for treatment of disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis 26:1107–1110. doi: 10.1086/520280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Supparatpinyo K, Nelson KE, Merz WG, Breslin BJ, CooperCR, Jr, Kamwan C, Sirisanthana T. 1993. Response to antifungal therapy by human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with disseminated Penicillium marneffei infections and in vitro susceptibilities of isolates from clinical specimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 37:2407–2411. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu Y, Albrecht K, Groll J, Beilhack A. 2020. Innovative therapies for invasive fungal infections in preclinical and clinical development. Expert Opin Invest Drugs 29:961–971. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2020.1791819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seyedmousavi S. 2021. Antifungal drugs. InAbraham DJ, Myers M (ed), Burger’s medicinal chemistry, drug discovery and development, 8th ed, vol 7, ch 7. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamoth F, Alexander BD. 2015. Antifungal activities of SCY-078 (MK-3118) and standard antifungal agents against clinical non-Aspergillus mold isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4308–4311. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00234-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfaller MA, Huband MD, Flamm RK, Bien PA, Castanheira M. 2019. In vitro activity of APX001A (manogepix) and comparator agents against 1,706 fungal isolates collected during an international surveillance program in 2017. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e00840-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00840-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrillo AJ, Guarro J. 2001. In vitro activities of four novel triazoles against Scedosporium spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:2151–2153. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.7.2151-2153.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capilla J, Yustes C, Mayayo E, Fernández B, Ortoneda M, Pastor FJ, Guarro J. 2003. Efficacy of albaconazole (UR-9825) in treatment of disseminated Scedosporium prolificans infection in rabbits. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:1948–1951. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.6.1948-1951.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver JD, Sibley GEM, Beckmann N, Dobb KS, Slater MJ, McEntee L, du Pre S, Livermore J, Bromley MJ, Wiederhold NP, Hope WW, Kennedy AJ, Law D, Birch M. 2016. F901318 represents a novel class of antifungal drug that inhibits dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:12809–12814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608304113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buil JB, Rijs A, Meis JF, Birch M, Law D, Melchers WJG, Verweij PE. 2017. In vitro activity of the novel antifungal compound F901318 against difficult-to-treat Aspergillus isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:2548–2552. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivero-Menendez O, Cuenca-Estrella M, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. 2019. In vitro activity of olorofim (F901318) against clinical isolates of cryptic species of Aspergillus by EUCAST and CLSI methodologies. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:1586–1590. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiederhold NP, Law D, Birch M. 2017. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor F901318 has potent in vitro activity against Scedosporium species and Lomentospora prolificans. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:1977–1980. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biswas C, Law D, Birch M, Halliday C, Sorrell TC, Rex J, Slavin M, Chen SC-A. 2018. In vitro activity of the novel antifungal compound F901318 against Australian Scedosporium and Lomentospora fungi. Med Mycol 56:1050–1054. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim W, Eadie K, Konings M, Rijnders B, Fahal AH, Oliver JD, Birch M, Verbon A, van de Sande W. 2020. Madurella mycetomatis, the main causative agent of eumycetoma, is highly susceptible to olorofim. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:936–941. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiederhold NP, Najvar LK, Jaramillo R, Olivo M, Birch M, Law D, Rex JH, Catano G, Patterson TF. 2018. The orotomide olorofim is efficacious in an experimental model of central nervous system coccidioidomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e00999-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00999-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seyedmousavi S, Chang YC, Law D, Birch M, Rex JH, Kwon-Chung KJ. 2019. Efficacy of olorofim (F901318) against Aspergillus fumigatus, A. nidulans, and A. tanneri in murine models of profound neutropenia and chronic granulomatous disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e00129-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00129-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hope WW, McEntee L, Livermore J, Whalley S, Johnson A, Farrington N, Kolamunnage-Dona R, Schwartz J, Kennedy A, Law D, Birch M, Rex JH. 2017. Pharmacodynamics of the orotomides against Aspergillus fumigatus: new opportunities for treatment of multidrug-resistant fungal disease. mBio 8:e01157-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01157-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Negri CE, Johnson A, McEntee L, Box H, Whalley S, Schwartz JA, Ramos-Martin V, Livermore J, Kolamunnage-Dona R, Colombo AL, Hope WW. 2018. Pharmacodynamics of the novel antifungal agent F901318 for acute sinopulmonary aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus flavus. J Infect Dis 217:1118–1127. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seyedmousavi S, Chang YC, Law D, Birch M, Rex J, Kwon-Chung KJ. 2019. In vivo efficacy of olorofim against systemic infection caused by Scedosporium apiospermum, Pseudallescheria boydii, and Lomentospora prolificans in neutropenic CD-1 mice, P415. 9th Trends in Medical Mycology held on 11–14 October 2019, Nice, France, organized under the auspices of EORTC-IDG and ECMM. J Fungi (Basel) 5:95. doi: 10.3390/jof5040095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Liu HF, Xi LY, Chang YC, Kwon-Chung KJ, Seyedmousavi S. 2020. Abstr 9th Adv Against Aspergillosis Mucormycosis Conf, Lugano, Switzerland, 27 to 29 February 2020, poster P32.

- 28.Zhang J, Liu HF, Xi LY, Chang YC, Kwon-Chung KJ, Seyedmousavi S. 2020. Abstr 30th Eur Congr Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, Paris, France, 18 to 21 April 2020, poster P1358.

- 29.Sun B-D, Chen AJ, Houbraken J, Frisvad JC, Wu W-P, Wei H-L, Zhou Y-G, Jiang X-Z, Samson RA. 2020. New section and species in Talaromyces. MycoKeys 68:75–113. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.68.52092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh A, Singh P, Meis JF, Chowdhary A. 9January2021. In vitro activity of the novel antifungal olorofim against dermatophytes and opportunistic moulds including Penicillium and Talaromyces species. J Antimicrob Chemother doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Lau SKP, Lo GCS, Lam CSK, Chow W-N, Ngan AHY, Wu AKL, Tsang DNC, Tse CWS, Que T-L, Tang BSF, Woo PCY. 2017. In vitro activity of posaconazole against Talaromyces marneffei by broth microdilution and Etest methods and comparison to itraconazole, voriconazole, and anidulafungin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01480-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01480-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lei HL, Li LH, Chen WS, Song WN, He Y, Hu FY, Chen XJ, Cai WP, Tang XP. 2018. Susceptibility profile of echinocandins, azoles and amphotericin B against yeast phase of Talaromyces marneffei isolated from HIV-infected patients in Guangdong, China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 37:1099–1102. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CLSI. 2017. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. CLSI M38-ED3, 3rd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), Wayne, PA.

- 34.CLSI. 2017. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. CLSI M27-ED4, 4th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), Wayne, PA.