ABSTRACT

It is known that the physiology of Methanosarcina species can differ significantly, but the ecological impact of these differences is unclear. We recovered two strains of Methanosarcina from two different ecosystems with a similar enrichment and isolation method. Both strains had the same ability to metabolize organic substrates and participate in direct interspecies electron transfer but also had major physiological differences. Strain DH-1, which was isolated from an anaerobic digester, used H2 as an electron donor. Genome analysis indicated that it lacks an Rnf complex and conserves energy from acetate metabolism via intracellular H2 cycling. In contrast, strain DH-2, a subsurface isolate, lacks hydrogenases required for H2 uptake and cycling and has an Rnf complex for energy conservation when growing on acetate. Further analysis of the genomes of previously described isolates, as well as phylogenetic and metagenomic data on uncultured Methanosarcina in anaerobic digesters and diverse soils and sediments, revealed a physiological dichotomy that corresponded with environment of origin. The physiology of type I Methanosarcina revolves around H2 production and consumption. In contrast, type II Methanosarcina species eschew H2 and have genes for an Rnf complex and the multiheme, membrane-bound c-type cytochrome MmcA, shown to be essential for extracellular electron transfer. The distribution of Methanosarcina species in diverse environments suggests that the type I H2-based physiology is well suited for high-energy environments, like anaerobic digesters, whereas type II Rnf/cytochrome-based physiology is an adaptation to the slower, steady-state carbon and electron fluxes common in organic-poor anaerobic soils and sediments.

IMPORTANCE Biogenic methane is a significant greenhouse gas, and the conversion of organic wastes to methane is an important bioenergy process. Methanosarcina species play an important role in methane production in many methanogenic soils and sediments as well as anaerobic waste digesters. The studies reported here emphasize that the genus Methanosarcina is composed of two physiologically distinct groups. This is important to recognize when interpreting the role of Methanosarcina in methanogenic environments, especially regarding H2 metabolism. Furthermore, the finding that type I Methanosarcina species predominate in environments with high rates of carbon and electron flux and that type II Methanosarcina species predominate in lower-energy environments suggests that evaluating the relative abundance of type I and type II Methanosarcina may provide further insights into rates of carbon and electron flux in methanogenic environments.

KEYWORDS: anaerobic respiration, extracellular electron transfer, Methanosarcina, direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET), Rnf complex, c-type cytochrome, methanogen, archaea

INTRODUCTION

The physiology and ecology of Methanosarcina species is of substantial interest because Methanosarcina plays a key role in anaerobic digestion, an important bioenergy strategy, and they contribute to methane production in soils and sediments that are an important source of atmospheric methane (1–3). Methanosarcina are unique among methanogens in their broad range of substrate utilization, which typically includes acetate and/or methylated compounds (methanol, methylamines) and, in some instances, H2 (2). All Methanosarcina species that have been evaluated can also accept electrons for the reduction of carbon dioxide to methane via direct interspecies electron transfer (4). In addition to producing methane, Methanosarcina may impact the biogeochemistry of anaerobic environments through the reduction of extracellular electron acceptors, such as Fe(III) and humic substances (5–7).

The two Methanosarcina species that have been studied in greatest detail are Methanosarcina barkeri and Methanosarcina acetivorans (3, 8). Remarkably, these two members of the same genus have distinct mechanisms for energy conservation (3, 9). M. barkeri physiology centers around H2 metabolism, even when acetate is provided as the substrate (10). M. barkeri requires three hydrogenases for growth on H2, Ech (energy converting), Frh (F420-reducing), and Vht (methanophenazine-linked) (3, 10, 11). Each hydrogenase interacts with different electron carriers that are important for the reduction of carbon dioxide to methane. During acetate metabolism, the Ech hydrogenase complex generates H2 in the cytoplasm, and the Vht complex reoxidizes this H2 after it diffuses across the cell membrane (3). This “intracellular H2 cycling” generates a proton gradient while coupling the electron transfer between oxidative and reductive components of the methane production pathway (3).

In contrast, M. acetivorans is unable to use H2 as an electron donor (12), and it does not employ H2 cycling in acetate metabolism (3, 8). M. acetivorans does have several gene clusters coding for Frh/Fre and Vht/Vhx hydrogenases, but it lacks genes for the Ech hydrogenase complex (11). Furthermore, no detectable hydrogenase enzyme activity has been detected in M. acetivorans (13). Instead, the six-subunit Rnf (Rhodobacter nitrogen fixation) complex serves as a membrane-bound electron transport chain that generates a sodium ion gradient that drives ATP production during acetoclastic methanogenesis (8, 9).

Cytochrome content is another major difference between M. barkeri and M. acetivorans. All Methanosarcina species contain b-type cytochromes that are essential components for methane formation (14). However, M. acetivorans also contains multiheme c-type cytochromes, whereas M. barkeri does not (15). Most notably, M. acetivorans, which is able to conserve energy to support growth from electron transfer to extracellular electron acceptors, requires a multiheme membrane-bound cytochrome A (MmcA) for extracellular electron transport (6, 7). In contrast, attempts to grow M. barkeri with extracellular electron acceptors were unsuccessful (5). M. mazei, which is similar to M. barkeri in lacking an Rnf complex and its ability to grow on H2 (16, 17) does contain a 5-heme c-type cytochrome, but it is of unknown function. Deletion of the gene for this in M. mazei, or its homolog in M. acetivorans, had no impact on methane production or extracellular electron exchange (7, 18).

We hypothesized that the physiological differences in Methanosarcina species could have ecological consequences. We combined isolation and characterization of new Methanosarcina strains with genomic analysis of previously described Methanosarcina isolates and molecular analyses of the distribution of Methanosarcina phyla and metabolic genes in diverse environments. The results suggest that Methanosarcina can be separated into two types that not only have distinct physiologies, but also preferred habitats.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Similar isolation methods but different environments yield Methanosarcina with distinct physiologies.

As detailed in Materials and Methods, strains DH-1 and DH-2 were enriched and isolated under similar conditions with the exception that temperatures for enrichment and isolation were environmentally appropriate. Strain DH-1 was recovered from anaerobic digester sludge and was enriched and isolated at 37°C, whereas strain DH-2 came from subsurface sediments and thus was enriched and isolated at 25°C.

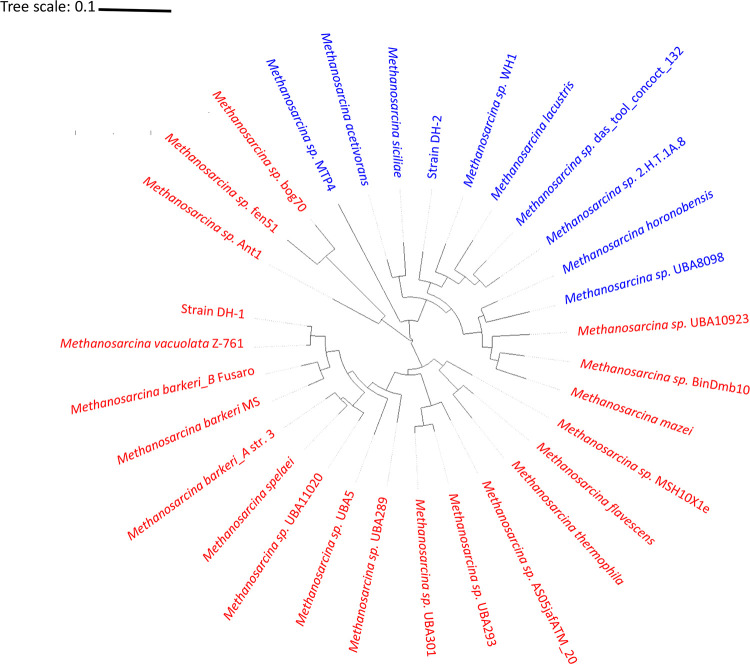

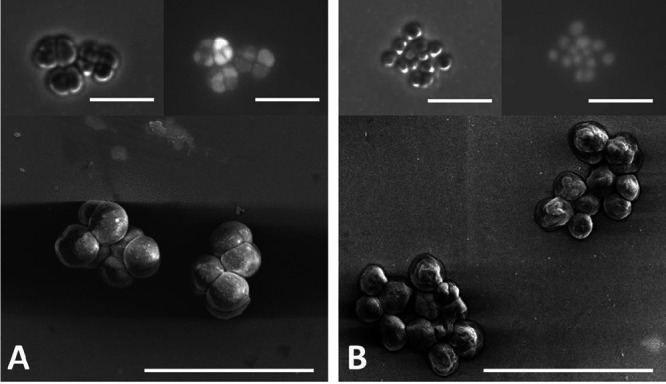

Both strain DH-1 and strain DH-2 are closely related to previously described Methanosarcina species (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The 16S rRNA and mcrA gene sequences from strain DH-1 are 99.59% and 95.29% identical, respectively, to M. vacuolata (Fig. S1). Genome analysis confirmed that DH-1 is most similar (97.73%) to M. vacuolata (Fig. 1), which was isolated from a mesophilic anaerobic digester (19). The 16S rRNA and mcrA gene sequences of strain DH-2 are 99.82% and 96% identical, respectively, to M. subterranea strain HC-2, which was isolated from groundwater in a deep subsurface diatomaceous shale formation (20). The genome of M. subterranea is currently not available; however, comparison of the strain DH-2 genome to other Methanosarcina genomes with the FastANI tool (average nucleotide identity [ANI], a measure of nucleotide-level genomic similarity between the coding regions of two genomes) (21) showed that DH-2 is most similar to M. lacustris (86.47%), which was isolated from anoxic lake sediments (22). Further phylogenetic comparisons of genomic data with Anvi’o software (23) indicated that strain DH-2 clustered with M. lacustris and Methanosarcina sp. strain WH1, which was isolated from sandy marsh sediments (24) (Fig. 1). Both DH-1 and DH-2 have a typical Methanosarcina coccoid morphology (Fig. 2).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree constructed from concatenated proteins from genomes of the 31 representative Methanosarcina species. Organisms highlighted in red represent type I Methanosarcina, while those highlighted in blue represent type II Methanosarcina species.

FIG 2.

(A and B) Images of strain DH-1 (A) and strain DH-2 (B) obtained with scanning electron microscopy (lower panels), phase contrast (upper left), and fluorescence microscopy (upper right). Bar, 10 μm.

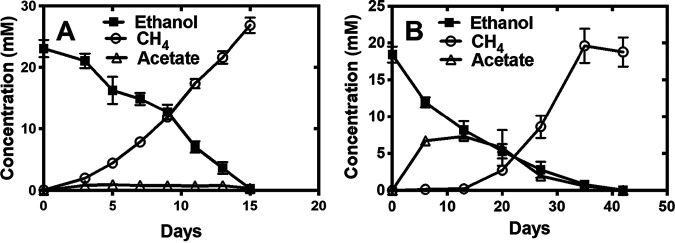

Both isolates were capable of acetotrophic growth and also utilized methanol, monomethylamine, dimethylamine, and trimethylamine as substrates for methanogenesis (Table 1). Neither species grew with formate, ethanol, or dimethyl sulfide (DMS) as substrates. Both DH-1 and DH-2 were capable of growing in coculture with Geobacter metallireducens converting ethanol to methane (Fig. 3). These findings are consistent with previous demonstrations that other Methanosarcina species can accept electrons for carbon dioxide reduction to methane from G. metallireducens via direct interspecies electron transfer because G. metallireducens is incapable of metabolizing ethanol with the production of H2 or formate (18, 25, 26). Both species grew optimally at 33°C (Fig. S2A) with only slight differences in salinity and pH optima (Fig. S2B and C).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Methanosarcina sp. DH-1 and DH-2 to other characterized Methanosarcina species

| Characteristic | Data for strain:a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Cell diameter (μm) | 2.0–2.8 | 1.3–2.4 | 1.5–2.0 | 2.9–3.9 | 0.9–1.4 | 1.0–2.0 |

| Temp range (°C) | 15–42 | 25–37 | 20–45 | 20–40 | 10–40 | 18–42 |

| Optimum temp (°C) | 33 | 33 | 40–42 | 35 | 35 | 37–40 |

| pH range | 3–6.8 | 6.3–8.0 | 5–7.5 | <5.0–7.5 | 5.9–7.4 | 6.0–8.0 |

| Optimum pH | 6.0 | 6.7–7.5 | 6–6.5 | 6.5 | 6.6–6.8 | 7.5 |

| Tolerance of NaCl (M) | 0–0.36 | 0 to >0.53 | 0–0.8 | 0 to >1 | 0–0.6 | 0.1–0.6 |

| Optimum NaCl (M) | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.2–0.6 | 0.1–0.2 | 0.1–0.2 |

| Utilization of:b | ||||||

| H2/CO2 | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| Methanol | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Acetate | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Formate | − | − | ND | − | − | − |

| Dimethyl sulfide | − | − | ND | + | ND | − |

| Monomethylamine | + | + | + | ND | + | + |

| Dimethylamine | + | + | + | ND | + | + |

| Trimethylamine | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ethanol | − | − | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Strain 1, Methanosarcina strain DH-1 (data from this study); strain 2, Methanosarcina strain DH-2 (data from this study); strain 3, Methanosarcina barkeri MST (90); strain 4, Methanosarcina siciliae C2J (91); strain 5, Methanosarcina subterranea HC-2T (20); strain 6, Methanosarcina vacuolata Z-761T (19).

+, positive result; −, negative result; ND, not determined.

FIG 3.

Ethanol consumption and methane and acetate production in defined cocultures established with G. metallireducens and either strain DH-1 (A) or DH-2 (B) on the fourth transfer of the cocultures. The mol CH4/mol ethanol yields of 1.2 and 1.0 mol CH4/mol for the cocultures with strains DH-1 and DH-2, respectively, are within the range of methane recoveries previously reported for G. metallireducens/Methanosarcina cocultures (18, 25, 26). Error bars represent triplicate samples.

The important physiological distinction between strains DH-1 and DH-2 revolved around H2. Strain DH-1 could grow with H2 as the electron donor and carbon dioxide as the electron acceptor, but strain DH-2 could not (Table 1). These results are consistent with genomic differences (Table S2). Strain DH-1 has all of the genes coding for the three hydrogenase complexes that M. barkeri requires for growth on H2. These include the Ech (energy converting) hydrogenase operon (echABCDEF), duplicate operons of the Frh (F420-reducing) hydrogenase (frhBGDA, freAEGB), and the Vht (methanophenazine-linked) hydrogenase (vhtDCAG, vhxGAC) (3, 10, 11, 27, 28). In contrast, strain DH-2 does not have Ech hydrogenase genes and only has a gene for the beta subunit of the Frh complex, eliminating the potential for growth on H2 or acetate metabolism via H2 cycling. Strain DH-2 does have all six of the genes coding for subunits of the Rnf complex (rnfABCDEG) necessary for energy conservation during acetate conversion to methane in M. acetivorans (3, 8, 9). Strain DH-1 lacks the Rnf genes, suggesting that it relies on H2 cycling during acetate metabolism, similar to M. barkeri (3, 27, 28).

The results demonstrated that strains DH-1 and DH-2 have substantially different physiologies, despite being enriched and isolated on the same medium. The primary difference between them was the environment from which they were recovered.

Environment of origin is predictive of physiological type for other Methanosarcina isolates.

In order to further evaluate whether the physiology of Methanosarcina isolates can be related to their environment of origin, we analyzed the genomes of previously described Methanosarcina isolates. This analysis further demonstrated that Methanosarcina species segregate into two physiological groups, which we designate type I and type II (Table 2). The primary physiological distinction between the type I Methanosarcina, of which M. barkeri is the most studied example, and type II Methanosarcina, exemplified by M. acetivorans, is the role of H2 in metabolism. The type I Methanosarcina species have the ability to consume H2 as an electron donor and possess the Ech hydrogenase necessary for metabolism of acetate via H2 cycling (10, 28) but lack an Rnf complex that is essential for energy conservation during acetate conversion to methane in the absence of H2 cycling (8, 29). In contrast, the type II Methanosarcina species possess an Rnf complex and typically do not grow on H2 (Table 2). The exception to this generalization is M. lacustris, which is reported to grow on H2 (22) but contains an Rnf complex as well as multiheme c-type cytochromes (NCBI GenBank accession number CP009515.1) that are characteristic of type II Methanosarcina, as discussed in detail below.

TABLE 2.

Genome and physiological characteristics of Methanosarcina strains available in pure culturea

| Methanosarcina strain | Rnf complex present? | Ech hydrogenase present? | No. of multiheme c-type cytochromes | MmcA present? | Utilization of H2-CO2 | Habitat | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanosarcina barkeri MS | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Anaerobic sewage sludge digester | 90, 92 |

| Methanosarcina barkeri 227 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Anaerobic sewage sludge digester | 93 |

| Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Bovine rumen | 94 |

| Methanosarcina barkeri JCM 10043 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Anaerobic sewage sludge digester | 95 |

| Methanosarcina barkeri_A strain 3 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Unknown | 96 |

| Methanosarcina barkeri_B Fusaro | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Mud from Lago del Fusaro Lake | 96, 97 |

| Methanosarcina barkeri_B Wiesmoor | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Peat bog | 98 |

| Methanosarcina flavescens E03.2 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Full-scale commercial biogas plant fed with maize silage, cattle manure, and dry poultry feces | 99 |

| Methanosarcina mazei Go1 | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Anaerobic sewage digester | 100 |

| Methanosarcina mazei 1.H.A.0.1 | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Sediment from the Columbia River Estuary | 31 |

| Methanosarcina mazei C16 | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Shoal mud of the southern North Sea | 101 |

| Methanosarcina mazei JCM 9314 | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Paddy field soil | 102 |

| Methanosarcina mazei JL01 | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Arctic permafrost | 103 |

| Methanosarcina mazei LYC | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Swamp mud | 104 |

| Methanosarcina mazei S-6 | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Wastewater treatment plant sludge | 90 |

| Methanosarcina mazei SarPi | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Rice paddy soil | 104 |

| Methanosarcina mazei SMA-21 | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Siberian permafrost-affected soil | 105 |

| Methanosarcina mazei Tuc01 | No | Yes | 1 | No | Yes | Sediment from hydropower station reservoir | 106 |

| Methanosarcina spelaei MC-15 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Floating biofilm on a sulfurous subsurface lake | 107 |

| Methanosarcina thermophila Ms 97 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Sheep rumen | DSM 11855 |

| Methanosarcina thermophila TM-1 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Thermophilic digester sludge | 108 |

| Methanosarcina vacuolata Z-761 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Mesophilic anaerobic digester | 90 |

| Strain DH-1 | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Sludge from anaerobic digester | This study |

| Methanosarcina vacuolata Kolksee | No | Yes | 0 | No | Yes | Lake Kolksee mud | 109 |

| Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A | Yes | No | 4 | MA0658 | No | Methane-evolving sediments of a marine canyon | 12 |

| Methanosarcina horonobensis HB-1 | Yes | No | 3 | Ga0072443_113899 | No | Groundwater sampled from a subsurface Miocene formation | 110 |

| Methanosarcina horonobensis JCM 15518 | Yes | No | 3 | Ga0128354_1005162 | No | Groundwater sampled from a subsurface Miocene formation | 110 |

| Methanosarcina lacustris Z-7289 | Yes | Yes | 2 | Ga0072454_11511 | Yes | Anoxic lake sediments | 22 |

| Methanosarcina siciliae C2J | Yes | No | 4 | Ga0072451_11663 | No | Submarine canyon sediments | 91 |

| Methanosarcina siciliae H1350 | Yes | No | 4 | Ga0072474_11601 | No | Production water from off shore oil well | 111 |

| Methanosarcina siciliae T4/M | Yes | No | 3 | Ga0072440_11646 | No | Pristine lake sediment | 111 |

| Methanosarcina sp. WH1 | Yes | No | 3 | Ga0072445_113060 | No | Anoxic sandy sediments | 24 |

| Strain DH-2 | Yes | No | 4 | Ga0399897_1739 | No | Subsurface aquifer sediments | This study |

| Methanosarcina sp. MTP4 | Yes | No | 2 | Ga0072449_113047 | No | Salt marsh sandy sediments | 112 |

Further details regarding substrate utilization are provided in Table S1. Methanosarcina with white background represent type I Methanosarcina, whereas those shaded in gray are type II Methanosarcina.

Previously, the physiological differences between M. barkeri and M. acetivorans were attributed to the difference between the marine environment of M. acetivorans and the less saline “freshwater” environments of M. barkeri and close relatives (30). However, the distinction between type I and type II Methanosarcina does not appear to be related to salinity. One notable difference is that many of the type I Methanosarcina species have been recovered from methanogenic digesters (Table 2). In contrast, none of the type II Methanosarcina species are digester isolates (Table 2). However, it must be recognized that isolate recovery may not always be a reliable indication of which types of Methanosarcina are most abundant in specific environments. For example, M. mazei (a type I species) was isolated from sediments collected from the Columbia River Estuary, but molecular analysis revealed that M. mazei was relatively rare in this environment and that type II Methanosarcina such as M. lacustris, M. acetivorans, and M. horonobensis were much more abundant (31).

Metagenomic and phylotype data also support specific physiology-environment associations.

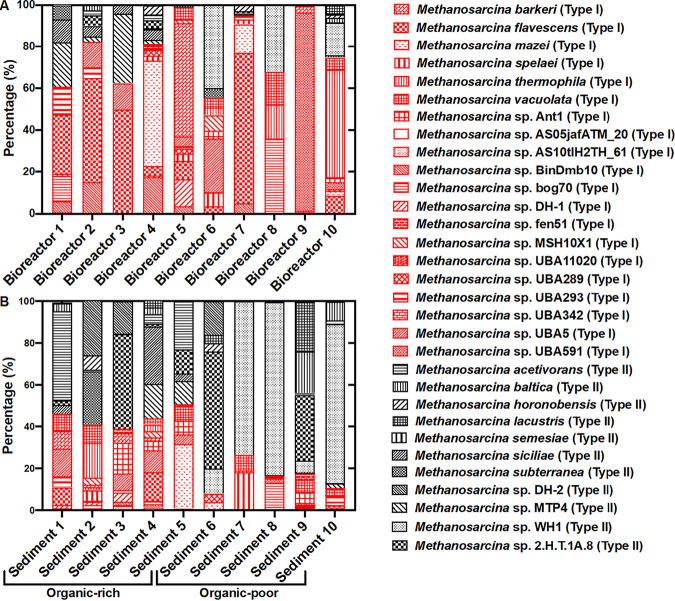

In order to evaluate the environmental distribution of Methanosarcina species without culture bias, previously published data on mcrA and 16S rRNA gene sequences from 20 different methanogenic environments (10 anaerobic digesters and 10 anoxic soils/sediments) were analyzed (Fig. 4). Type I species accounted for 78 ± 16.2% of the Methanosarcina isolates in the digester environments (Fig. 4A), and type II species accounted for 70 ± 15.9% of the Methanosarcina isolates in the sedimentary environments (Fig. 4B). A Chi-square test of independence and a Fisher’s exact test both confirmed that the sediment and digester Methanosarcina communities were significantly different (P < 0.0001, alpha = 0.05).

FIG 4.

Proportions of various Methanosarcina species based on mcrA, 16S rRNA, or both mcrA and 16S rRNA gene sequences from metagenomic libraries constructed from 20 different environments. Species were designated as type I or type II based on the physiology of pure culture isolates of the same species. Type I and type II species are designated with red and black symbols, respectively. All of the bioreactor environments had total organic carbon (TOC) concentrations of >5% (Table S3), while sediment TOC concentrations varied significantly. Bioreactor 1: low-salinity bioreactor (JGI GOLD IDs Ga0334882 to Ga0334890 mcrA); bioreactor 2: anaerobic solid waste digester (73, 74) (SRR8165483; mcrA); bioreactor 3: anaerobic digester in wastewater treatment plant (Gp0313021; mcrA); bioreactor 4: GAC-amended bioreactor treating municipal solid waste (MSW) (75) (SRR7687449 to SRR7687452; 16S rRNA and mcrA); bioreactor 5: bioreactor seeded with sewage sludge (76) (SRR5486931; mcrA); bioreactor 6: sewage sludge and household waste codigester (77) (ERR2586913 to ERR2586931; mcrA); bioreactor 7: cattle manure digester (78) (SRR3166092; mcrA); bioreactor 8: switchgrass digester (79) (JGI GOLD IDs Ga0134090 to Ga0134105; 16S rRNA and mcrA); bioreactor 9: bioreactor treating the dry organic fraction of MSW (80) (SRR5229592; 16S rRNA); bioreactor 10: anaerobic digester at WWTP (SRR3485656; 16S rRNA); sediment 1: mesotrophic meromictic freshwater lake, DOC ∼40 to 80 μM) (81) (IMG GOLD IDs Ga0247831 to Ga0247844); 16S rRNA and mcrA); sediment 2: paddy soil TOC 2.85% (82) (SRR11653212 to SRR11653222; 16S rRNA); sediment 3: estuary sediments, TOC >3.5% (31–33) (SRR1210425 to SRR1210426; mcrA); sediment 4: peat bog sediments, TOC 6 to 50% (36) (IMG GOLD ID Gp0348925; mcrA); sediment 5: mangrove sediment, TOC 0.7 to 11.4% (83, 84) (SRR3095812; mcrA); sediment 6: groundwater and sediments from uranium-contaminated aquifer, TOC <0.2% (38), mcrA (48); sediment 7: Amazon soil, TOC <2% (85) (SRR12110053 to SRR12110059; 16S rRNA); sediment 8: freshwater lake sediments, DOC ∼4 to 60 mg/liter) (86, 87) (IMG GOLD IDs Ga0031653 to Ga0031658; 16S rRNA); sediment 9: South Georgia marine sediments, TOC ∼0.65% (88) (SRR12815614 to SRR12815618; mcrA); sediment 10: Aarhus Bay marine sediments, TOC ∼2% (89) (SRR7119900 to SRR7119905; mcrA). Further details regarding organic carbon concentrations from various environments are available in Table S3 in the supplemental material.

The distribution of Methanosarcina in sediments was examined in more detail. Although all well-characterized type II isolates have been recovered from sediments, the molecular data demonstrated that the relative abundance of type II Methanosarcina was lower in sediments with higher organic content, such as estuaries, mangrove sediments, and peat bogs (sediments 1 to 5, Fig. 4B). Organic inputs into estuaries from agricultural and wastewater runoff promote algal blooms and enrich H2-producing fermentative Bacteroidetes species (32–34), which would provide an electron source for hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis by type I Methanosarcina. Peat, rice paddy, and mangrove sediments, which have high concentrations of partially degraded plant debris, are also organic content rich (35–37). Type II was much more abundant in sediments expected to have smaller amounts of organic matter, such as subsurface aquifer sediments and soils/sediments with high sand content (sediments 6 to 10, Fig. 4B), which tend to have low organic carbon content (38, 39).

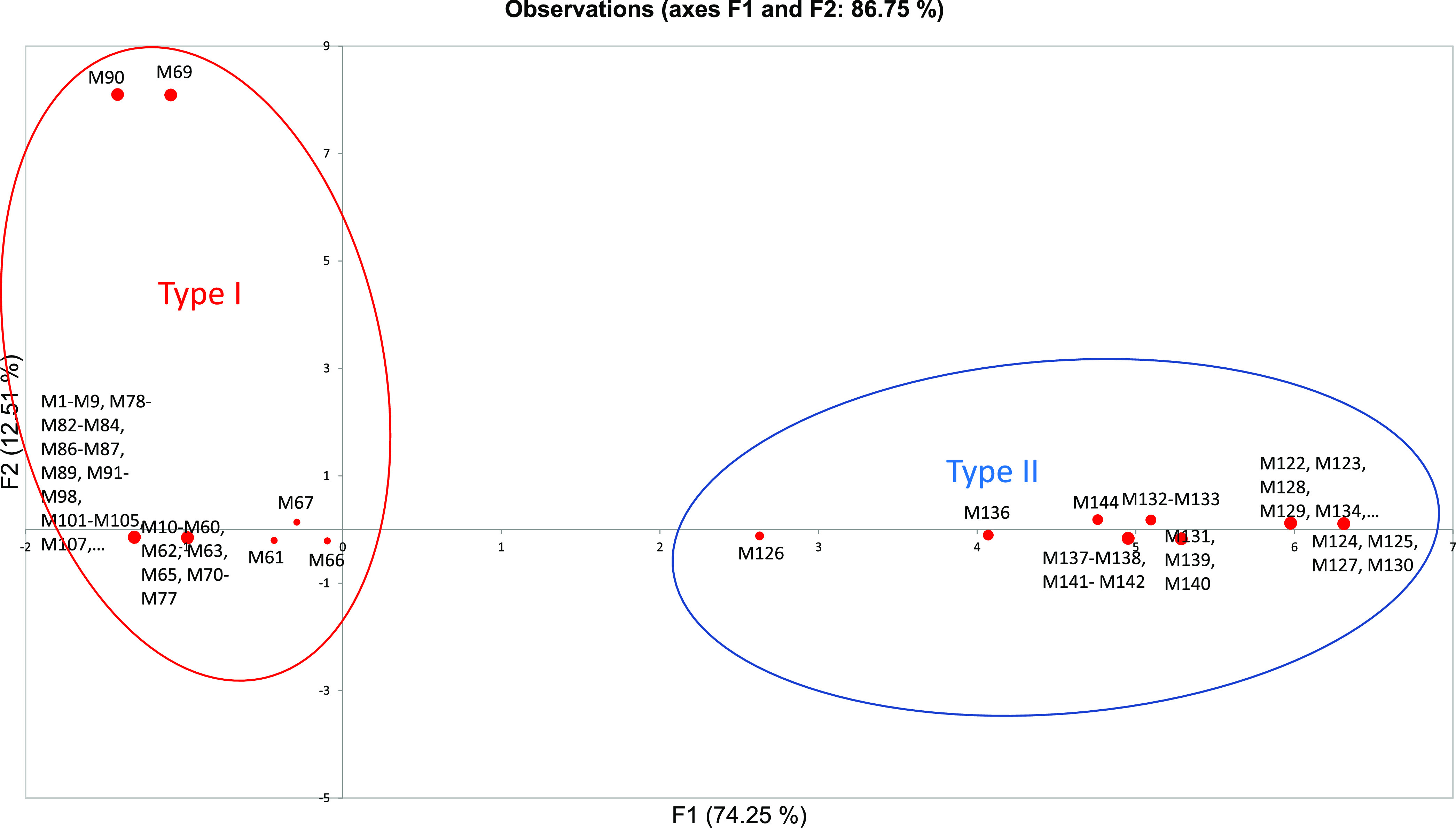

In order to further evaluate the possible correspondence between physiology and environment in Methanosarcina species, 144 assembled genomes from diverse environments were grouped into 32 different Methanosarcina species based on a 96% ANI cutoff value for species demarcation (Table S1). Type I or type II physiology was inferred from the presence or absence of Rnf and Ech and the ability to utilize H2 as the electron donor for CO2 reduction. Environments were characterized by their total organic content (TOC); those with TOC concentrations greater than 2% were considered high, and those below 2% were considered low (33, 36, 38–43) (Table S3). A mixed principal-component analysis comparing Methanosarcina strains with genomes that were at least 90% complete further confirmed that type I and type II Methanosarcina sort into two different groups based on genome characteristics, physiology, and habitat organic content (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

Results from mixed principal-component analysis of 144 different Methanosarcina strains using the following observations: quantitative (number of multiheme c-type cytochromes) and qualitative (type I or type II, presence/absence of Rnf complex, presence/absence of Ech hydrogenase complex, presence/absence of MmcA homolog, organic content of environment from which organism was isolated/detected [high (>2% TOC) or low (<2% TOC)]). M1-M144 specifies the Methanosarcina strain described in Table S1; organisms with CheckM genome completeness scores of <90% were not included in the analysis.

Differences in mode of extracellular electron exchange.

The different environmental niches of type I and type II Methanosarcina may also be reflected in their different strategies for extracellular electron transfer. These differences in electron transfer strategies are apparent when one focuses on the presence or absence of multiheme c-type cytochromes that are known to facilitate extracellular electron transfer in many other species. Analysis of all of the available Methanosarcina genomes revealed that only type II Methanosarcina species have genes for the seven-heme, membrane-associated, c-type cytochrome MmcA (Table 2, Table S1), shown to be essential for extracellular electron transfer in M. acetivorans (7). Notably, M. barkeri, which lacks MmcA, reduced extracellular electron acceptors, such as Fe(III) and the humics analog anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate, but unlike M. acetivorans, could not gain energy from the growth of these extracellular electron acceptors (5).

Other multiheme c-type cytochromes were detected in type II Methanosarcina but not in type I Methanosarcina, with the exception of one c-type cytochrome found in all type I M. mazei strains (Table S4). The function of this cytochrome, which is also present in type II Methanosarcina, is unknown. Gene deletion studies have indicated that this cytochrome is not involved in methane production or extracellular electron exchange (7, 18). The presence of this c-type cytochrome in M. mazei, but not other type I Methanosarcina species, and the fact that M. mazei appears to be one of three exceptions to type I and type II Methanosarcina aligning in distinct phylogenetic groups (Fig. 1), indicates that the evolution of type I and type II Methanosarcina physiologies warrants further study.

Implications.

In summary, the results of multiple lines of investigation, including both cultivation- and non-cultivation-based approaches, indicate that distinct differences in Methanosarcina physiology have ecological consequences. Type I Methanosarcina species are best suited for growth in environments with high rates of organic matter degradation, such as anaerobic digesters and organic-rich sediments. A physiology that revolves around H2 is probably sustainable in such environments because H2 is expected to be well above the nanomolar steady-state levels found in soils and sediments with lower energy input. However, in methanogenic soils and sediments, where steady-state H2 concentrations are only ca. 10 nM (44), methanogens that specialize in the use of H2 as an electron donor and have higher affinities for H2 uptake than Methanosarcina species (14) can be expected to outcompete Methanosarcina. It is also likely that the H2-utilizing specialists can consume H2 that type I Methanosarcina species produce during acetate metabolism. Type II Methanosarcina may save energy by not expressing hydrogenases that would be of little use for H2 uptake in organic-poor soils and sediments, but then require the Rnf-based alternative to intracellular H2 cycling to conserve energy from acetate metabolism. It is also more likely that alternative electron acceptors such as Fe(III) and oxidized humic substances will become intermittently available in soils and sediments with low organic content due to intermittent drying, oxygen inputs from animal burrowing and plants, or changes in oxygen availability in the overlying water. The expression of the multiheme c-type cytochrome MmcA, which enables growth via extracellular electron transfer, may confer an additional advantage to type II Methanosarcina in such environments.

Thus, the relative importance of type I and type II Methanosarcina may provide further insights into rates of carbon and electron flux in methanogenic environments. The important physiological differences in Methanosarcina should be recognized when interpreting their role in anaerobic environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture media and growth conditions.

Methanosarcina strains DH-1 and DH-2 were cultured under strictly anaerobic conditions in modified DSMZ 120 medium (https://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/medium/pdf/DSMZ_Medium120.pdf), in which concentrations of Na2S · 9H2O and l-cysteine · HCl were adjusted to 0.5 mM and 1 mM, respectively. Yeast extract, Casitone, and resazurin were not added to the medium (25), and all cultures were incubated in an oxygen-free 80:20 N2:CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3; 2 g/liter) was added to all cultures except when pH tolerance was being tested. Either acetate (40 mM) or methanol (100 mM) was used as the electron donors and carbon sources unless otherwise noted.

Geobacter metallireducens (ATCC 53774) was routinely cultured under strict anaerobic conditions with ethanol (20 mM) provided as the electron donor and Fe(III) citrate (55 mM) as the electron acceptor at 30°C under anaerobic conditions (N2:CO2, 80:20) as previously described (45).

For coculture experiments, G. metallireducens and either Methanosarcina strain DH-1 or DH-2 were anaerobically grown with ethanol (20 mM) provided as the sole electron donor and CO2 as the acceptor at 30°C as previously described (25, 26, 46).

Isolation of Methanosarcina strains.

Strain DH-1 (type I) was isolated from sludge collected from an anaerobic digester operating at a wastewater treatment plant located in Pittsfield, MA. Initial enrichment cultures were established by inoculating 0.1 g sludge into 156-ml serum bottles containing the modified DSMZ 120 medium described above, but with acetate (40 mM) provided as the electron donor. Enrichments were incubated under an 80:20 N2:CO2 atmosphere for 60 days at 37°C in the presence of antibiotics (kanamycin [200 μg/ml], erythromycin [200 μg/ml], and penicillin-G [50 μg/ml]).

Strain DH-2 (type II) was isolated from sediments and groundwater collected from a 24-acre experimental site located on the premises of an old uranium ore processing facility in Rifle, Colorado. This site has uranium concentrations in the water table that are 2 to 8 times higher than the water contamination limit established by UMTRA (Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action). Many in situ uranium bioremediation experiments have been conducted at this site (47). Sediments and groundwater for DH-2 methanogenic enrichments were collected in September 2011 from well CD-01, which was downgradient from the point of injection of ∼15 mM acetate into the subsurface to stimulate U(VI) reduction (48). Then, 5 g wet sediment and 5 ml aquifer groundwater were added to 40 ml modified DSMZ 120 medium with acetate (40 mM) in 156-ml serum bottles in an anaerobic chamber under an 80:20 N2:CO2 atmosphere. To reduce growth of bacteria, antibiotics (kanamycin [200 μg/ml], erythromycin [200 μg/ml], and penicillin-G [50 μg/ml]) were added to the enrichment cultures. All sediment enrichments were incubated for 60 days at 25°C.

After initial DH-1 and DH-2 methanogenic enrichments were established, serial dilutions to extinction were carried out at 37°C or 25°C, respectively, in 9 ml modified DSMZ 120 medium with acetate (40 mM) as the substrate for growth. Ampicillin (1 mg/ml), gentamicin (20 μg/ml), and tetracycline (10 μg/ml) were added to the media to suppress the growth of bacteria. The highest dilution that grew after the fourth serial transfer was then transferred to solidified modified DSMZ 120 medium (2% agar, wt/vol) in Hungate anaerobic roll tubes amended with 0.02% (wt/vol) yeast extract. Isolated single colonies were selected from each tube and resuspended in 2 ml of liquid medium and grown at 37°C or 25°C.

The purity of both strains was confirmed with microscopy and 16S rRNA gene sequencing with primers Arc344F (5′-ACGGGGYGCAGCAGGCGCGA-3′) and Arc915R (5′-GTGCTCCCCGCCAATTCCT-3′) (49). The PCR was also conducted with primers targeting bacterial 16S rRNA genes (49) to ensure that cultures were not contaminated with bacteria.

Metabolic and growth profile.

For determination of the pattern of substrate utilization, a sterile anoxic stock solution of each substrate was added to a final concentration of 10 to 50 mM in modified DMSZ 120 medium. Hydrogen as an electron donor was provided as an H2-CO2 mixture (80:20; at 105 pascals pressure). The ability to utilize various substrates was confirmed by growth at 37°C after at least four transfers with the substrate being investigated.

The effects of pH values, temperatures, and salt concentrations on the growth of both strains were tested with modified DMSZ 120 medium with methanol (100 mM) as the substrate. Specifically, optimal salt concentrations for both strains were evaluated at 37°C with the addition of appropriate volumes from a sterile anoxic stock solution (300 g/liter NaCl). Three different buffering systems were needed to adjust DSMZ 120 medium without NaHCO3 supplementation for pH optimum experiments. pH was adjusted with the addition of HCl or NaOH to the following buffering systems: for pH ≤ 5.0, no buffer additions were needed; for pH 5.0 to 7.0, 100 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES, pKa = 5.98) was added; for pH 6.5 to 8.0, 100 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS, pKa = 6.98) was added; for pH 8.0 to 8.5, 100 mM Tricine (pKa = 7.80) was added. After incubation at 37°C, all pHs remained within 0.1 unit of the original value.

Analytical techniques.

Methanosarcina cultures were monitored by changes in optical density measured in a split-beam, dual-detector spectrophotometer (Spectronic Genosys2; Thermo Electron Corp.) at an absorbance of 600 nm (7). Growth of G. metallireducens cultures on Fe(III) was monitored by the formation of Fe(II) over time with a ferrozine assay in the same spectrophotometer at an absorbance of 562 nm as previously described (50, 51).

Ethanol and methanol concentrations were monitored with a gas chromatograph equipped with a headspace sampler and a flame ionization detector (Clarus 600; PerkinElmer, Inc., California). Methane in the headspace was measured by gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector (GC-8A; Shimadzu) as previously described (52). Acetate concentrations were measured with a Shimadzu high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) with an Aminex HPX-87H ion exclusion column (300 mm by 7.8 mm) and an eluent of 8.0 mM sulfuric acid.

Microscopy.

Cells were routinely examined by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy (BV-2A filter set) with a Nikon E600 microscope. For scanning electron microscopy, cells were harvested during the late exponential phase of growth and fixed with 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) for 12 h at 4°C. Then, cell pellets were washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer and dehydrated with solutions of increasing ethanol concentrations (35%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100% [vol/vol]) and a hexamethyldisilazane/ethanol solution (1:1) as previously described (53). Cells were then immersed in pure hexamethyldisilazane and dried with a stream of high-purity nitrogen. Scanning electron microscopy was conducted with an ultrahigh-resolution field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Magellan 400; Nanolab Technologies, California, USA).

Genome extraction and analysis.

For extraction of genomic DNA, cultures (50 ml in 156-ml serum bottles) were divided into 50- ml conical tubes, and cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,500 rpm (Sorvall Heraeus 75006445 rotor) for 15 min. After centrifugation, cell pellets were resuspended in 10 ml TE sucrose buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, and 6.7% [wt/vol] sucrose), and DNA was extracted from the cell pellets as previously described (54). DNA concentrations were evaluated with the Qubit double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) high-sensitivity (HS) assay kit (Life Technologies) and sent for whole-genome sequencing by Molecular Research LP (MR DNA).

Initial raw nonfiltered DH-1 and DH-2 libraries contained 14,766,691 and 15,568,552 reads, respectively, that were ∼100 bp long. Reads were quality checked by visualization of base quality scores and nucleotide distributions with FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Sequences from all of the libraries were trimmed and filtered with Trimmomatic (55), resulting in an average of 14,585,756 and 15,342,415 quality reads for the DH-1 and DH-2 libraries, respectively. All paired-end reads were then merged with FLASH (56), resulting in 6,630,882 and 7,008,483 reads with an average read length of 152 bp. Contigs were then assembled from these quality control (QC)-filtered and merged reads with SeqMan NGen (DNAStar) and MEGAHIT software (57) with an overlapping base length of 50 bp and a minimum contig length of 500 bp.

These contigs were then submitted to Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes (IMG/MER) for preliminary annotation (img.jgi.doe.gov). The current Methanosarcina sp. DH-1 draft genome sequence contains 51 contigs with 4,061 total genes and 3,957 protein-coding genes. The draft genome sequence of strain DH-2 is composed of 37 contigs with 4,130 total genes and 4,043 protein-coding genes. The quality of the assembled genomes was determined using SeqMan NGen software (DNAStar) and the genome quality assessment program CheckM (58) on the KBase website (www.kbase.us) (Table S4).

Phylogenetic and statistical analyses.

Initial gene sequence analyses were done with tools available on the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) website (img.jgi.doe.gov) and through comparisons to GenBank nucleotide and protein databases with BLASTn and BLASTx algorithms (59, 60). Some protein domains were identified with NCBI conserved domain search (61) and Pfam search (62) functions. Transmembrane helices were predicted with TMpred (63) TMHMM (64) and HMMTOP (65), and protein localization and signal peptide predictions were made with PSORTb v. 3.0.2 (66), SOSUI (67) and SignalP v. 4.1 (68).

16S rRNA gene alignments were generated with MAFFT (69), and phylogenetic trees were constructed with MEGA7 software using the maximum likelihood method with 100 bootstrap replicates (70). Average nucleotide identities (ANI) for all Methanosarcina genomes were obtained with FastANI (21), and whole-genome-based phylogenetic trees were generated in Anvi’o (23). The Anvi’o output was then imported into iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/) and FigTree v.1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree).

All metagenomes and genomes analyzed for environmental comparisons were downloaded from the NCBI SRA database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) or from the JGI IMG Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes database (https://img.jgi.doe.gov). The software program Prodigal (71) was used to identify open reading frames in unassembled genomes. Databases with mcrA and 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences were built from the various Methanosarcina species with the makeblastdb function using NCBI BLAST-2.2.31+ standalone software (72). All statistical analyses were done with XLSTAT, Statistical Software for Excel.

Data availability.

Genome sequences for strains DH-1 and DH-2 have been submitted to the NCBI genome database under BioProject numbers PRJNA561374 and PRJNA561362 and BioSample numbers SAMN12616996 and SAMN12616828, respectively. The genomes have also been submitted to the IMG under IMG genome IDs 2835727744 and 2835723613.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the Army Research Office and was accomplished under grant number W911NF-17-1-0345. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. government.

The authors do not declare any conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Dawn E. Holmes, Email: dholmes@wne.edu.

Jeremy D. Semrau, University of Michigan–Ann Arbor

REFERENCES

- 1.De Vrieze J, Hennebel T, Boon N, Verstraete W. 2012. Methanosarcina: the rediscovered methanogen for heavy duty biomethanation. Bioresour Technol 112:1–9. 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boone D, Mah R. 2015. Methanosarcina. In Bergey’s manual of systematics of archaea and bacteria. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Hoboken, NJ. 10.1002/9781118960608.gbm00519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mand TD, Metcalf WW. 2019. Energy conservation and hydrogenase function in methanogenic archaea, in particular the genus Methanosarcina. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 83:e00020-19. 10.1128/MMBR.00020-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotaru AE, Yee MO, Musat F. 2021. Microbes trading electricity in consortia of environmental and biotechnological significance. Curr Opin Biotechnol 67:119–129. 10.1016/j.copbio.2021.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond DR, Lovley DR. 2002. Reduction of Fe(III) oxide by methanogens in the presence and absence of extracellular quinones. Environ Microbiol 4:115–124. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakash D, Chauhan SS, Ferry JG. 2019. Life on the thermodynamic edge: respiratory growth of an acetotrophic methanogen. Sci Adv 5:eaaw9059. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw9059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes DE, Ueki T, Tang HY, Zhou J, Smith JA, Chaput G, Lovley DR. 2019. A membrane-bound cytochrome enables Methanosarcina acetivorans to conserve energy from extracellular electron transfer. mBio 10:e00789-19. 10.1128/mBio.00789-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferry JG. 2020. Methanosarcina acetivorans: a model for mechanistic understanding of aceticlastic and reverse methanogenesis. Front Microbiol 11:1806. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welte C, Deppenmeier U. 2014. Bioenergetics and anaerobic respiratory chains of aceticlastic methanogens. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837:1130–1147. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulkarni G, Mand TD, Metcalf WW. 2018. Energy conservation via hydrogen cycling in the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri. mBio 9:e01256-18. 10.1128/mBio.01256-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guss AM, Kulkarni G, Metcalf WW. 2009. Differences in hydrogenase gene expression between Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina barkeri. J Bacteriol 191:2826–2833. 10.1128/JB.00563-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sowers KR, Baron SF, Ferry JG. 1984. Methanosarcina acetivorans sp. nov., an acetotrophic methane-producing bacterium isolated from marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 47:971–978. 10.1128/AEM.47.5.971-978.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guss AM, Mukhopadhyay B, Zhang JK, Metcalf WW. 2005. Genetic analysis of mch mutants in two Methanosarcina species demonstrates multiple roles for the methanopterin-dependent C-1 oxidation/reduction pathway and differences in H2 metabolism between closely related species. Mol Microbiol 55:1671–1680. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thauer RK, Kaster AK, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R. 2008. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:579–591. 10.1038/nrmicro1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kletzin A, Heimerl T, Flechsler J, van Niftrik L, Rachel R, Klingl A. 2015. Cytochromes c in Archaea: distribution, maturation, cell architecture, and the special case of Ignicoccus hospitalis. Front Microbiol 6:439. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deppenmeier U, Johann A, Hartsch T, Merkl R, Schmitz RA, Martinez-Arias R, Henne A, Wiezer A, Bäumer S, Jacobi C, Brüggemann H, Lienard T, Christmann A, Bömeke M, Steckel S, Bhattacharyya A, Lykidis A, Overbeek R, Klenk H-P, Gunsalus RP, Fritz H-J, Gottschalk G. 2002. The genome of Methanosarcina mazei: evidence for lateral gene transfer between bacteria and archaea. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 4:453–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mah R. 1980. Isolation and characterization of Methanococcus mazei. Curr Microbiol 3:321–325. 10.1007/BF02601895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yee MO, Rotaru AE. 2020. Extracellular electron uptake in Methanosarcinales is independent of multiheme c-type cytochromes. Sci Rep 10:372. 10.1038/s41598-019-57206-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhilina T, Zavarzin G. 1987. Methanosarcina vacuolata sp. nov., a vacuolated Methanosarcina. IJSEB 37:281–283. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimizu S, Ueno A, Naganuma T, Kaneko K. 2015. Methanosarcina subterranea sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from a deep subsurface diatomaceous shale formation. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 65:1167–1171. 10.1099/ijs.0.000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain C, Rodriguez RL, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. 2018. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun 9:5114. 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simankova MV, Parshina SN, Tourova TP, Kolganova TV, Zehnder AJ, Nozhevnikova AN. 2001. Methanosarcina lacustris sp. nov., a new psychrotolerant methanogenic archaeon from anoxic lake sediments. Syst Appl Microbiol 24:362–367. 10.1078/0723-2020-00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eren AM, Esen OC, Quince C, Vineis JH, Morrison HG, Sogin ML, Delmont TO. 2015. Anvi’o: an advanced analysis and visualization platform for ’omics data. PeerJ 3:e1319. 10.7717/peerj.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouviere P, Wolfe R. 1988. Observation of red fluorescence in a new marine Methanosarcina, abstr. 1-20, p 184. 88th Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotaru AE, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Markovaite B, Chen S, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2014. Direct interspecies electron transfer between Geobacter metallireducens and Methanosarcina barkeri. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:4599–4605. 10.1128/AEM.00895-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yee MO, Snoeyenbos-West OL, Thamdrup B, Ottosen LDM, Rotaru AE. 2019. Extracellular electron uptake by two Methanosarcina species. Front Energy Res 7. 10.3389/fenrg.2019.00029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulkarni G, Kridelbaugh DM, Guss AM, Metcalf WW. 2009. Hydrogen is a preferred intermediate in the energy-conserving electron transport chain of Methanosarcina barkeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:15915–15920. 10.1073/pnas.0905914106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mand T, Kulkarni G, Metcalf W. 2018. Genetic, biochemical, and molecular characterization of Methanosarcina barkeri mutants lacking three distinct classes of hydrogenase. J Bacteriol 200:e00342-18. 10.1128/JB.00342-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlegel K, Welte C, Deppenmeier U, Muller V. 2012. Electron transport during aceticlastic methanogenesis by Methanosarcina acetivorans involves a sodium-translocating Rnf complex. FEBS J 279:4444–4452. 10.1111/febs.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferry JG, Lessner DJ. 2008. Methanogenesis in marine sediments. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1125:147–157. 10.1196/annals.1419.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Youngblut N, Wirth J, Henriksen J, Smith M, Simon H, Metcalf W, Whitaker R. 2015. Genomic and phenotypic differentiation among Methanosarcina mazei populations from Columbia River sediment. ISME J 9:2191–2205. 10.1038/ismej.2015.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith MW, Davis RE, Youngblut ND, Karna T, Herfort L, Whitaker RJ, Metcalf WW, Tebo BM, Baptista AM, Simon HM. 2015. Metagenomic evidence for reciprocal particle exchange between the mainstem estuary and lateral bay sediments of the lower Columbia River. Front Microbiol 6:1074. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayslip G, Edmond L, Partridge V, Nelson W, Lee HJ, Cole F, Lamberson J, Caton L. 2007. Ecological condition of the Columbia River Estuary: an environmental monitoring and assessment program (EMAP) report. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10, Office of Environmental Assessment, Seattle, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilbert M, Needoba J, Koch C, Barnard A, Baptista A. 2013. Nutrient loading and transformations in the Columbia River Estuary determined by high-resolution in situ sensors. Estuaries Coasts 36:708–727. 10.1007/s12237-013-9597-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong T, Felix N, Mohd S, Sulaeman A. 2016. Characterization of soil organic matter in peat soil with different humification levels using FTIR. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 136:012010. 10.1088/1757-899X/136/1/012010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klingenfuß C, Roßkopf N, Walter J, Heller C, Zeitz J. 2014. Soil organic matter to soil organic carbon ratios of peatland soil substrates. Geoderma 235-236:410–417. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders C, Smoak J, Waters M, Sanders L, Brandini N, Patchineelam S. 2012. Organic matter content and particle size modifications in mangrove sediments as responses to sea level rise. Mar Env Res 77:150–155. 10.1016/j.marenvres.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox P, Nico P, Tfaily M, Heckman K, Davis J. 2017. Characterization of natural organic matter in low-carbon sediments: extraction and analytical approaches. Org Geochem 114:12–22. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yost J, Hartemink A. 2019. Soil organic carbon in sandy soils: a review. Adv Agron 158:217–310. 10.1016/bs.agron.2019.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arienzo M, Toscano F, Di Fraia M, Caputi L, Sordino P, Guida M, Aliberti F, Ferrara L. 2014. An assessment of contamination of the Fusaro Lagoon (Campania Province, southern Italy) by trace metals. Env Monitor Assess 186:217–310. 10.1007/s10661-014-3816-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Estes ER, Pockalny R, D’Hondt S, Inagaki F, Morono Y, Murray RW, Nordlund D, Spivack AJ, Wankel SD, Xiao N, Hansel CM. 2019. Persistent organic matter in oxic subseafloor sediment. Nat Geosci 12:126–131. 10.1038/s41561-018-0291-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Haas H, van Weering C, de Stigter H. 2002. Organic carbon in shelf seas: sinks or sources, processes and products. Cont Shelf Res 22:691–717. 10.1016/S0278-4343(01)00093-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ioka S, Sakai T, Igarashi T, Ishijima Y. 2010. Particulate organic carbon concentrations in anoxic groundwater in quaternary deposit of Horonobe town, Hokkaido, Japan. J Groundw Hydrol 52:205–210. 10.5917/jagh.52.205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovley DR, Goodwin S. 1988. Hydrogen concentrations as an indicator of the predominant terminal electron-accepting reactions in aquatic sediments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 52:2993–3003. 10.1016/0016-7037(88)90163-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lovley DR, Giovannoni SJ, White DC, Champine JE, Phillips EJ, Gorby YA, Goodwin S. 1993. Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals. Arch Microbiol 159:336–344. 10.1007/BF00290916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holmes DE, Rotaru AE, Ueki T, Shrestha PM, Ferry JG, Lovley DR. 2018. Electron and proton flux for carbon dioxide reduction in Methanosarcina barkeri during direct interspecies electron transfer. Front Microbiol 9:3109. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams KH, Bargar JR, Lloyd JR, Lovley DR. 2013. Bioremediation of uranium-contaminated groundwater: a systems approach to subsurface biogeochemistry. Curr Opin Biotechnol 24:489–497. 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holmes DE, Orelana R, Giloteaux L, Wang LY, Shrestha P, Williams K, Lovley DR, Rotaru AE. 2018. Potential for methanosarcina to contribute to uranium reduction during acetate-promoted groundwater bioremediation. Microb Ecol 76:660–667. 10.1007/s00248-018-1165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M, Glockner FO. 2013. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e1. 10.1093/nar/gks808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lovley DR, Phillips EJ. 1988. Novel mode of microbial energy metabolism: organic carbon oxidation coupled to dissimilatory reduction of iron or manganese. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:1472–1480. 10.1128/AEM.54.6.1472-1480.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lovley DR, Phillips EJ. 1987. Rapid assay for microbially reducible ferric iron in aquatic sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 53:1536–1540. 10.1128/AEM.53.7.1536-1540.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holmes DE, Giloteaux L, Orellana R, Williams KH, Robbins MJ, Lovley DR. 2014. Methane production from protozoan endosymbionts following stimulation of microbial metabolism within subsurface sediments. Front Microbiol 5:366. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang HY, Holmes DE, Ueki T, Palacios PA, Lovley DR. 2019. Iron corrosion via direct metal-microbe electron transfer. mBio 10:e00303-19. 10.1128/mBio.00303-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson I, Risso C, Holmes D, Lucas S, Copeland A, Lapidus A, Cheng JF, Bruce D, Goodwin L, Pitluck S, Saunders E, Brettin T, Detter JC, Han C, Tapia R, Larimer F, Land M, Hauser L, Woyke T, Lovley D, Kyrpides N, Ivanova N. 2011. Complete genome sequence of Ferroglobus placidus AEDII12DO. Stand Genomic Sci 5:50–60. 10.4056/sigs.2225018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Magoc T, Salzberg SL. 2011. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27:2957–2963. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li D, Liu CM, Luo R, Sadakane K, Lam TW. 2015. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31:1674–1676. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. 2015. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res 25:1043–1055. 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marchler-Bauer A, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Geer LY, Geer RC, He J, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lanczycki CJ, Lu F, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Wang Z, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zheng C, Bryant SH. 2015. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D222–D226. 10.1093/nar/gku1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, Salazar GA, Tate J, Bateman A. 2016. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D279–D285. 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hofmann K, Stoffel W. 1993. TMbase: a database of membrane spanning proteins segments. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler 374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 305:567–580. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tusnady GE, Simon I. 2001. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics 17:849–850. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu NY, Wagner JR, Laird MR, Melli G, Rey S, Lo R, Dao P, Sahinalp SC, Ester M, Foster LJ, Brinkman FS. 2010. PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics 26:1608–1615. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hirokawa T, Boon-Chieng S, Mitaku S. 1998. SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics 14:378–379. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods 8:785–786. 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. 2010. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11:119. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee H. 2018. Characterization of the microbial community in a sequentially fed anaerobic digester treating solid organic waste. MS thesis. University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kanger K, Guilford NGH, Lee H, Nesbo CL, Truu J, Edwards EA. 2020. Antibiotic resistome and microbial community structure during anaerobic co-digestion of food waste, paper and cardboard. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 96:fiaa006. 10.1093/femsec/fiaa006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lei Y, Sun D, Dang Y, Feng X, Huo D, Liu C, Zheng K, Holmes DE. 2019. Metagenomic analysis reveals that activated carbon aids anaerobic digestion of raw incineration leachate by promoting direct interspecies electron transfer. Water Res 161:570–580. 10.1016/j.watres.2019.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beller HR, Rodrigues AV, Zargar K, Wu YW, Saini AK, Saville RM, Pereira JH, Adams PD, Tringe SG, Petzold CJ, Keasling JD. 2018. Discovery of enzymes for toluene synthesis from anoxic microbial communities. Nat Chem Biol 14:451–457. 10.1038/s41589-018-0017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Westerholm M, Castillo MDP, Andersson AC, Nilsen PJ, Schnurer A. 2019. Effects of thermal hydrolytic pre-treatment on biogas process efficiency and microbial community structure in industrial- and laboratory-scale digesters. Waste Manag 95:150–160. 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bassani I, Kougias PG, Treu L, Angelidaki I. 2015. Biogas upgrading via hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in two-stage continuous stirred tank reactors at mesophilic and thermophilic conditions. Environ Sci Technol 49:12585–12593. 10.1021/acs.est.5b03451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liang XY, Whitham JM, Holwerda EK, Shao XJ, Tian L, Wu YW, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Klingeman DM, Yang ZMK, Podar M, Richard TL, Elkins JG, Brown SD, Lynd LR. 2018. Development and characterization of stable anaerobic thermophilic methanogenic microbiomes fermenting switchgrass at decreasing residence times. Biotechnol Biofuels 11:243. 10.1186/s13068-018-1238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dang Y, Sun D, Woodard T, Wang L, Nevin K, Holmes D. 2017. Stimulation of the anaerobic digestion of the dry organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW) with carbon-based conductive materials. Bioresour Technol 238:30–38. 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oswald K, Jegge C, Tischer J, Berg J, Brand A, Miracle MR, Soria X, Vicente E, Lehmann MF, Zopfi J, Schubert CJ. 2016. Methanotrophy under versatile conditions in the water column of the ferruginous meromictic Lake La Cruz (Spain). Front Microbiol 7:1762. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fan LC, Dippold MA, Ge TD, Wu JS, Thiel V, Kuzyakov Y, Dorodnikov M. 2020. Anaerobic oxidation of methane in paddy soil: role of electron acceptors and fertilization in mitigating CH4 fluxes. Soil Biol Biochem 141:107685. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.107685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Teo D, Tan H, Corlett R, Wong C, Lum S. 2003. Continental rain forest fragments in Singapore resist invasion by exotic plants. J Biogeogr 30:305–310. 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00813.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jing H, Cheung S, Zhou Z, Wu C, Nagarajan S, Liu H. 2016. Spatial variations of the methanogenic communities in the sediments of tropical mangroves. PLoS One 11:e0161065. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meyer KM, Morris AH, Webster K, Klein AM, Kroeger ME, Meredith LK, Brændholt A, Nakamura F, Venturini A, Fonseca de Souza L, Shek KL, Danielson R, van Haren J, Barbosa de Camargo P, Tsai SM, Dini-Andreote F, de Mauro JMS, Barlow J, Berenguer E, Nüsslein K, Saleska S, Rodrigues JLM, Bohannan BJM. 2020. Belowground changes to community structure alter methane-cycling dynamics in Amazonia. Environ Int 145:106131. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Docherty KM, Young KC, Maurice PA, Bridgham SD. 2006. Dissolved organic matter concentration and quality influences upon structure and function of freshwater microbial communities. Microb Ecol 52:378–388. 10.1007/s00248-006-9089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bertolet B, West W, Armitage D, Jones S. 2019. Organic matter supply and bacterial community composition predict methanogenesis rates in temperate lake sediments. Limnol Oceanogr 4:164–172. 10.1002/lol2.10114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Geprags P, Torres ME, Mau S, Kasten S, Romer M, Bohrmann G. 2016. Carbon cycling fed by methane seepage at the shallow Cumberland Bay, South Georgia, sub-Antarctic. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 17:1401–1418. 10.1002/2016GC006276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Beulig F, Roy H, McGlynn S, Jorgensen B. 2019. Cryptic CH4 cycling in the sulfate–methane transition of marine sediments apparently mediated by ANME-1 archaea. ISME J 13:250–262. 10.1038/s41396-018-0273-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maestrojuan G, Boone D. 1991. Characterization of Methanosarcina barkeri MST and 227, Methanosarcina mazei S-6T, and Methanosarcina vacuolata Z-761T. Int J Syst Bacteriol 41:267–274. 10.1099/00207713-41-2-267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Elberson M, Sowers K. 1997. Isolation of an aceticlastic strain of Methanosarcina siciliae from marine canyon sediments and emendation of the species description for Methanosarcina siciliae. Int J Syst Bacteriol 47:1258–1261. 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weimer P, Zeikus J. 1978. One carbon metabolism in methanogenic bacteria. Cellular characterization and growth of Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch Microbiol 119:49–57. 10.1007/BF00407927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mah R, Smith M, Baresi L. 1978. Studies on an acetate-fermenting strain of Methanosarcina. Appl Environ Microbiol 35:1174–1184. 10.1128/AEM.35.6.1174-1184.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jarvis G, Strömpl C, Burgess D, Skillman L, Moore E, Joblin K. 2000. Isolation and identification of ruminal methanogens from grazing cattle. Curr Microbiol 40:327–332. 10.1007/s002849910065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bryant M, Boone D. 1987. Emended description of strain MST (DSM 800T), the type strain of Methanosarcina barkeri. Int J Syst Bacteriol 37:169–170. 10.1099/00207713-37-2-169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kandler O, Hippe H. 1977. Lack of peptidoglycan in the cell walls of Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch Microbiol 113:57–60. 10.1007/BF00428580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maestrojuan G, Boone J, Mah R, Menaia J, Sachs M, Boone D. 1992. Taxonomy and halotolerance of mesophilic Methanosarcina strains, assignment of strains to species, and synonymy of Methanosarcina mazei and Methanosarcina frisia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 42:561–567. 10.1099/00207713-42-4-561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scherer P, Kneifel H. 1983. Distribution of polyamines in methanogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol 154:1315–1322. 10.1128/JB.154.3.1315-1322.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kern T, Fischer M, Deppenmeier U, Schmitz R, Rother M. 2016. Methanosarcina flavescens sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from a full-scale anaerobic digester. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:1533–1538. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jussofie A, Mayer F, Gottschalk G. 1986. Methane formation from methanol and molecular hydrogen by protoplasts of new methanogenic isolates and inhibition by dicyclohexylcarbodiimide. Arch Microbiol 146:245–249. 10.1007/BF00403224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Blotevogel K, Fischer U, Lupkes K. 1986. Methanococcus frisius sp. nov., a new methylotrophic marine methanogen. Can J Microbiol 32:127–131. 10.1139/m86-025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Watanabe T, Kimura M, Asakawa S. 2006. Community structure of methanogenic archaea in paddy field soil under double cropping (rice-wheat). Soil Biol Biochem 38:1264–1274. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Oshurkova V, Troshina O, Trubitsyn V, Ryzhmanova Y, Bochkareva O, Shcherbakova V. 2020. Characterization of Methanosarcina mazei JL01 isolated from Holocene arctic permafrost and study of the archaeon cooperation with bacterium Sphaerochaeta associata GLS2T. Proceedings 66:4. 10.3390/proceedings2020066004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu Y, Boone D, Sleat R, Mah R. 1985. Methanosarcina mazei LYC, a new methanogenic isolate which produces a disaggregating enzyme. Appl Environ Microbiol 49:608–613. 10.1128/AEM.49.3.608-613.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wagner D, Schirmack J, Ganzert L, Morozova D, Mangelsdorf K. 2013. Methanosarcina soligelidi sp. nov., a desiccation- and freeze-thaw-resistant methanogenic archaeon from a Siberian permafrost-affected soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 63:2986–2991. 10.1099/ijs.0.046565-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Barauna R, Gracas D, Ramos R, Carneiro A, Lopes T, Lima A, Zahlouth R, Pellizari V, Silva A. 2013. Genome sequencing of methanogenic Archaea Methanosarcina mazei TUC01 strain isolated from an Amazonian flooded area, abstr B43B-01. Abstr Am Geophy Union Spring Meet, Cancun, Mexico, 14 to 17 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ganzert L, Schirmack J, Alawi M, Mangelsdorf K, Sand W, Hillebrand-Voiculescu A, Wagner D. 2014. Methanosarcina spelaei sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from a floating biofilm of a subsurface sulphurous lake. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:3478–3484. 10.1099/ijs.0.064956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zinder SH, Sowers KR, Ferry JG. 1985. Methanosarcina thermophila sp. nov., a thermophilic, acetotrophic, methane-producing bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 35:522–523. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hippe H, Caspari D, Fiebig K, Gottschalk G. 1979. Utilization of trimethylamine and other N-methyl compounds for growth and methane formation by Methanosarcina barkeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:494–498. 10.1073/pnas.76.1.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shimizu S, Upadhye R, Ishijima Y, Naganuma T. 2011. Methanosarcina horonobensis sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from a deep subsurface Miocene formation. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 61:2503–2507. 10.1099/ijs.0.028548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ni S, Boone D. 1991. Isolation and characterization of a dimethyl sulfide-degrading methanogen, Methanolobus siciliae HI350, from an oil well, characterization of M. siciliae T4/MT, and emendation of M. siciliae. Int J Syst Bacteriol 41:410–416. 10.1099/00207713-41-3-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Finster K, Tanimoto Y, Bak F. 1992. Fermentation of methanethiol and dimethylsulfide by a newly isolated methanogenic bacterium. Arch Microbiol 157:425–430. 10.1007/BF00249099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1 and S2. Download AEM.00731-21-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.1 MB (138.3KB, pdf)

Table S1. Download AEM.00731-21-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.1 MB (89.2KB, xlsx)

Table S2. Download AEM.00731-21-s0003.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.1 MB (21.6KB, xlsx)

Table S3. Download AEM.00731-21-s0004.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.1 MB (15.5KB, xlsx)

Table S4. Download AEM.00731-21-s0005.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.1 MB (14KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

Genome sequences for strains DH-1 and DH-2 have been submitted to the NCBI genome database under BioProject numbers PRJNA561374 and PRJNA561362 and BioSample numbers SAMN12616996 and SAMN12616828, respectively. The genomes have also been submitted to the IMG under IMG genome IDs 2835727744 and 2835723613.