Abstract

Purpose of review:

In this review, we describe the biology of extracellular vesicles (EV) and how they contribute to bone-associated cancers.

Recent findings:

Crosstalk between tumor and bone have been demonstrated to promote tumor and metastatic progression. In addition to direct cell to cell contact and soluble factors, such as cytokines, EVs mediate crosstalk between tumor and bone. EVs are composed of a heterogenous group of membrane-delineated vesicles of varying size range, mechanisms of formation and content. These include apoptotic bodies, microvesicles, large oncosomes and exosomes. EVs derived from primary tumors have been shown to alter bone remodeling and create formation of a pre-metastatic niche that favors development of bone metastasis. Similarly, EVs from marrow stromal cells have been shown to promote tumor progression. Additionally, EVs can act as therapeutic delivery vehicles due to their low immunogenicity and targeting specificity.

Summary:

EVs play critical roles in intercellular communication. Multiple classes of EVs exist based on size on mechanism of formation. In addition to a role in pathophysiology, EVs can be exploited as therapeutic delivery vehicles.

Keywords: bone metastasis, tumor microenvironment, exosome, oncosomes, apoptosomes

Introduction

Extracellular vesicle biology

Communication between cells occurs through multiple mechanisms including directly through cell to cell contact and indirectly through soluble factors such as cytokines and hormones. In addition to these mechanisms, cells communicate both locally and at a distance through extracellular vesicles (EV). The mechanisms and resulting impact on function of cell to cell contact and soluble factor signaling have received much attention. In contrast, the role of EVs in intercellular signaling have recently been gaining in-depth understanding [1-3]. EVs contribute to a variety of physiological and pathological processes, including inflammation, coagulation, stem-cell biology, and tumor growth and metastasis [4].

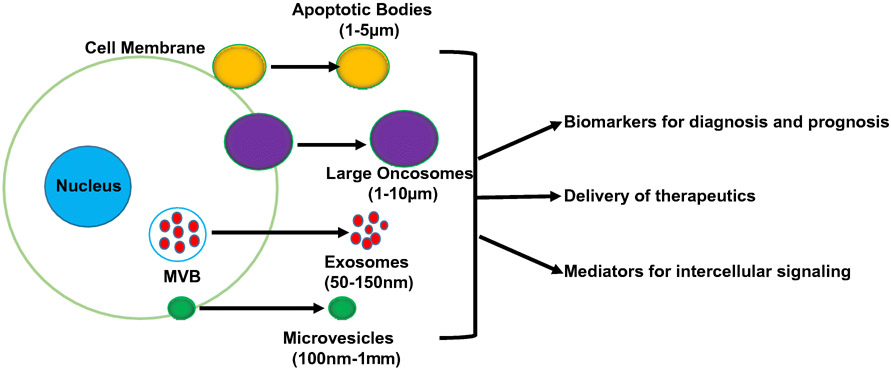

EVs are membrane delineated vesicles that are released from cells through both active and passive processes [5]. EVs represent a heterogenous group of vesicles whose size may vary range between nanometers through micrometers [6, 7] (Fig. 1). EV membranes may contain proteins and other biomolecules, and EV cargo contains multiple types of biomolecules including DNA, RNA, proteins and lipids [8-11]. EVs can be found in most bodily fluids including blood, urine, saliva, and breast milk [12]. EVs act as mediators of intercellular communication by transferring molecular cargo to a recipient cell, and also by transmitting signals at the recipient cell surface [13]. For example, it has been reported that EVs can act as intermediaries for cytokine signaling, and cytokines that are present on the EV surface can alter signaling in the recipient cell [14]. The classification of EVs is complicated and is constantly undergoing change. One popular classification system derives from the mechanism through which the EVs are formed. Based on this, EVs can be broadly classified into apoptotic bodies, large oncosomes, microvesicles, and exosomes [9].

Figure 1. Extracellular vesicle (EV) basic biology.

EVs are produced by many cell types. Multiple types of EVs are produced and range in size from nanometer through micrometer range. EVs promote indirect cell to cell communication and signaling both locally and at a distance from their origination. EVs’ membranes and cargo reflect their cell of origin which confers on them the ability to serve as biomarkers. Additionally, their ability to target cells with specificity and incorporate therapeutics enables them to serve as therapeutic delivery vehicles. MVB= multivesicular body.

Apoptotic bodies, also called apoptosomes, are extracellular vesicles released from apoptotic cells. The apoptotic process induces cell membrane blebs which progress to forming membrane-delineated vesicles that contain disintegrated cell components [15]. Apoptotic bodies range in size from 200 nm-5 μm, with a range of 50-500 nm range being the most commonly released [15, 16]. It has been reported that apoptotic bodies can transfer oncogenes to recipient cells. For example, Bergsmedh et al. found that uptake of apoptotic bodies produced by oncogene-expressing cells resulted in decreased contact inhibition and tumorigenicity of p53 knock out murine embryonic fibroblasts [17].

Microvesicles, like apoptotic bodies, are formed from the cell membrane. Also termed microparticles or ectosomes, microvesicles are a diverse population of vesicles formed through outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane and release [18]. They range in size from 100 nm to 1,000 nm [3]. Upon formation, microvesicles are composed of components of the cell membrane; whereas, their cargo is composed of intracellular components that were adjacent to the cell membrane during the microvesicle’s formation [19]. Microvesicle budding utilizes the ARF6 (ADPribosylation factor 6, a RAS-related GTPase) and the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) system [20]. Studies have identified ARF6 as integral to the regulation of selective protein recruitment into microvesicles, and of microvesicle shedding through its function in cell invasion, peripheral actin remodeling, and endocytic trafficking [21, 22].

In contrast to apoptotic bodies and microvesicles which are formed from cell membrane , exosomes originate in the endosomal system, and are typically smaller than 150 nm (30-150 nm) [3]. Exosomes, which are also known as small EVs, are formed through the process of endosome processing. Specifically, early endosomes mature into late endosomes, or multivesicular bodies (MVB). As this process occurs, the ESCRT machinery mediates the invagination of the endosomal membranes to form intraluminal vesicles (ILV), which are released as exosomes when the MVB fuse with the plasma membrane [17]. Through their ability to transfer a variety of biomolecules, exosomes perform a multitude of functions involved in cell-cell communication. Similar to the endosomal membranes from which they originate, exosomes consist of a lipid bilayer with high cholesterol and phosphatidylserine levels, which may facilitate internalization through endocytosis, phagocytosis, and fusion [38]. Within the categories of exosomes, there is further heterogeneity. Zhang et al. reported the presence of small exosomes (Exo-S; 60-80 nm) and large exosomes (Exo-L; 90-120 nm), which varied not only by size but also their mechanical properties and molecular composition [23].

In addition to these classical EVs, large oncosomes are another EV subtype recently characterized that are 1-10 μm in diameter. These were originally discovered to be produced by prostate cancer cells and were called prostasomes [7]. Furthermore, production of this unique EV subtype was found to be dependent on oncogenic transformation, and a switch to a highly metastatic cancer cell phenotype [7].

The presence of multiple subtypes of EVs also relates to their cargo and function. Comparison of different EV subtypes isolated from the same cell type reveal differences in function. For example, it was found that in glioblastoma, the large EVs (> 1 μm) are enriched for both wildtype and mutant (variant III) EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) protein compared to small EVs (50-300 nm), which may ultimately influence cancer progression [24]. The heterogenous properties among different sized EVs indicates it is fundamental to characterize both the content and function for each EV subtype when investigating and describing EV potential as biomarkers.

Extracellular vesicles in medicine

Due to their property of incorporating components from their cell of origin, EVs have the potential to serve as biomarkers for disease diagnosis, disease progression and therapeutic monitoring [25]. Their utility as biomarkers is further enhanced by their presence in many different body fluids [26-28]. In particular, it has been demonstrated that the cargo of the EV is representative of the cell of origin. In situations of disease, this then suggests that the content of EV cargo is reflective of that disease state. When compared to the use of body fluids, including blood and urine, which may have confounding components, EVs and their cargo may be more reflective of a disease state, and thus more specific biomarkers [29]. Moreover, due to their potential to reflect disease progression over time, EVs may serve as reliable diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers in many clinical settings, such as autoimmune disorders, coronary artery disease, renal disease, hepatic disease, and neurodegenerative disorders [29-33]. Additionally, their potential to serve as biomarkers has been demonstrated in a variety of cancers including prostate carcinoma, bladder cancer, breast cancer and hematologic cancers [12, 34-40].

In addition to serving as biomarkers, multiple investigators have explored EVs for their ability to deliver target payloads (i.e., therapeutics) to tissues [41, 42]. Current strategies use artificially synthesized nanoparticles and liposomes. However, EVs offer multiple improvements over these systems as they can target tissues with high specificity and produce limited toxic effects [43, 44]. Their ability to carry and deliver a wide variety of molecules including small interfering RNA (siRNA) or pharmacologically-active compounds further strengthens their utility as therapeutic delivery vehicles [45, 46]. In addition, EVs are highly stable which confers on them the ability to last for long periods of time in the circulation. As EVs are endogenous to the body, immune response to EVs is low to negligible. As a result, EVs are able to shield their cargo from immune cells [43]. Due to the benefits of utilizing EVs as therapeutic delivery vesicles, preclinical studies have demonstrated EV efficacy as therapeutic delivery vehicles for multiple diseases including cancers, neuropathies and immune disorders [47].

EV-mediated communication in the bone-tumor microenvironment:

Cancer cell-derived EVs:

It is well established that cellular crosstalk between cancer cells and stromal cells has an immense influence on cancer progression. EVs are crucial to this cellular crosstalk, and there have been several reports of cancer cell-derived EVs impacting the metastatic tumor microenvironment and shaping the metastatic niche. In the bone specifically, cancer cell-derived EVs have been shown to affect various cell types found in the bone microenvironment. In multiple cancer types, cancer cell-derived EVs have been reported to inhibit osteoblast differentiation, while increasing osteoclast formation [48-51]. In breast cancer specifically, it has been shown that cancer cell derived EVs decrease osteoblast production of type I procollagen. In turn, altered collagen deposition, which is crucial for bone formation, further promoted the formation of a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment [52]. In a separate study, breast cancer derived EVs were shown to stimulate osteoclast formation and bone resorption through L-plastin, which was present in breast cancer EVs [48].

Besides the effect of cancer cell-derived EVs on osteoblasts and osteoclasts, EVs produced by cancer cells have also been reported to alter the activity of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Raimondo et al. found that EVs produced by multiple myeloma cells suppressed MSC differentiation into osteoblasts [53]. Ultimately, the authors were able to attribute this suppression of MSC differentiation to EV-associated miR-129-5p, which targets several osteoblast differentiation markers including alkaline phosphatase [53]. A separate study by Nakata et al. looked at the effect of cancer cell-derived EVs on MSC cytokine production. They found that MSCs exposed to neuroblastoma-derived EVs produced inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, and VEGF (vascular endothelial cell growth factor), and MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1), which are known pro-tumorigenic factors [54].

In addition to the impact of cancer-derived EVs on MSC and bone cell functions and development, it has been demonstrated that EVs from primary tumors can educate the bone marrow to create a pre-metastatic niche that favors the development of metastasis. Peinado et al. demonstrated that melanomas produce exosomes that promoted bone metastasis through stimulating the receptor tyrosine kinase MET in the bone marrow stroma [55]. In the setting of prostate cancer, Dai et al. determined that prostate cancer-derived exosomes targeted and increases pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) in bone marrow stromal cells, that resulted in increasing bone marrow metastasis [56].

Stromal cell-derived EVs:

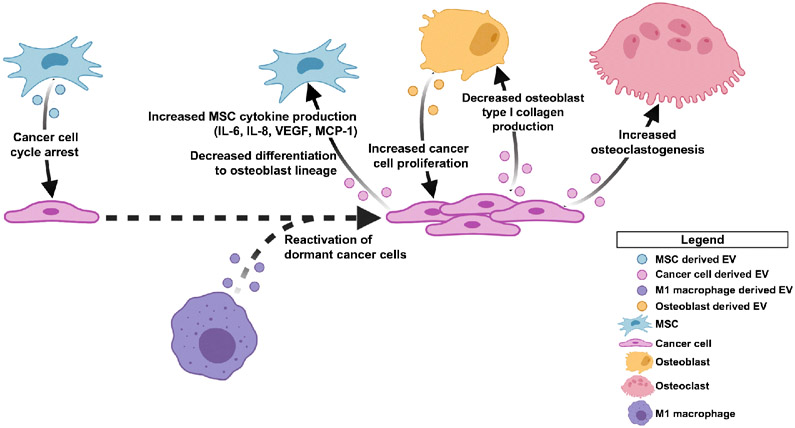

In addition to the effect of cancer cell-derived EVs on the surrounding microenvironment, stromal cell-derived EVs also have the ability to influence cancer progression by regulating cancer cell survival and proliferation. Interestingly, many studies that investigated MSC derived-EVs in bone metastasis found the EVs to have tumor-suppressive functions [57-59], MSC-derived EVs have been shown to suppress breast cancer metastasis to bone in parental, but not bone-seeking breast cancer cell lines [57]. In a separate study, Bliss et al. found that MSC-derived EVs induced cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells [58]. In this study, the authors investigated the effect of EVs from “primed” MSCs, i.e. MSCs that were cultured with breast cancer cells in a transwell system for 24 hr before MSC-derived EVs were isolated [58]. Interestingly, it was discovered that EVs from primed MSCs induced cell cycle arrest in a greater percentage of breast cancer cells compared to EVs from naive (i.e. not primed) MSCs [58]. It was found that primed MSCs produced EVs containing miR-222/223, which was responsible for inducing cell cycle arrest in cancer cells exposed to EVs from primed MSCs [58]. While MSC-derived EVs appear to suppress cancer progression, it has been shown that EVs from macrophages stimulate cancer proliferation. M1 macrophages, specifically, were found to reactivate dormant breast cancer cells through EV transfer [60].

Intercellular communication between cancer cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts is central to regulating cancer progression in bone. Much of the research on interactions between these cells types have looked at soluble proteins as mediators of intercellular communication, such as in the vicious cycle of bone metastases [61]. Despite the fact that many studies that have investigated soluble protein mediated communication between cancer cells, osteoblasts, and/or osteoclasts, there are limited studies that have examined the effect of osteoblast or osteoclast derived EVs on the activity of cancer cells in bone. One study by Morhayim et al. examined the effect of osteoblast EVs on prostate cancer progression and found that prostate cancer cells exposed to osteoblast derived EVs exhibited increased proliferation, however the effect of osteoblast EVs on tumor growth in vivo was not investigated [62].

When considering these studies together, it appears to be the case that EV-mediated crosstalk between cancer cells and the bone microenvironment evolves throughout the course of disease (Fig. 2). In early stages of disease, cancer cell-derived EVs have been shown to co-opt stromal cells and aid in creating a pre-metastatic niche. At the same time, during these early stages of disease, there is evidence that stroma-derived EVs suppress proliferation of disseminated tumor cells (DTCs), thereby suppressing cancer progression. Furthermore, in late stages of disease, when cancer cells are already present in the bone, data suggests that cancer-derived EVs can act on the stroma to suppress osteoblast function while promoting osteoclast activation. It is not yet known what role EVs play in the switch between early cancer cell dissemination to overt metastasis formation. Additionally, while it is evident that EVs are key mediators of communication, there are several modes of intercellular communication that occur in the tumor microenvironment that all contribute to the complexity of disease progression.

Figure 2. Extracellular vesicle (EV)-mediated crosstalk in the tumor microenvironment.

In early stages of disease, MSC derived EVs have been reported to induce cell cycle arrest in DTCs. M1 macrophage EVs have been shown to reactivate dormant DTCs. In later stages of disease, cancer cell derived EVs further promote a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment in the bone by inducing MSCs to produce inflammatory cytokines and decreasing MSC differentiation to osteoblasts. Cancer cell derived EVs have also been shown to alter osteoblast production of type I collagen and increase osteoclast formation. Additionally, osteoblast derived EVs have been shown to act on cancer cells to increase cancer cell proliferation. Figure created via BioRender.com.

Conclusions

EVs represent a highly heterogenous class of vesicles that are derived through different mechanisms. EVs and their cargo reflect the cellular content and membrane composition of their cell of origin. This property allows them to contribute to indirect cell-to-cell signaling both locally and distantly from their site of origin. Furthermore, EVs are potent biomarkers due to their cargo being representative of disease progression.

Crosstalk between bone-derived EVs and cancer cells and cancer-derived EVs and bone have been demonstrated to have important impacts in terms of cancer progression and bone remodeling. In addition to cancer-derived EVs impacting bone remodeling, EVs can promote the development of a pre-metastatic niche that subsequently promotes metastasis. Similarly, bone stromal-derived EVs have been demonstrated to promote cancer growth in bone.

While there have been recent gains in understanding the role of EVs in bone-associated cancer, there are many aspects that are yet to be uncovered. Elucidating the biology of EVs and their role in bone-associated cancers has the potential to foster development of therapeutics to diminish cancer in bone.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01093900 (ETK), and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Center K99/R00 Pathway to Independence Grant R00CA178177 (KMB) and Pennsylvania State Department of Health 4100072566 (KMB).

Footnotes

Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Raposo G, Stahl PD. Extracellular vesicles: a new communication paradigm? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(9):509–10. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Niel G, D'Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213–28. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(4):373–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gangoda L, Boukouris S, Liem M, Kalra H, Mathivanan S. Extracellular vesicles including exosomes are mediators of signal transduction: are they protective or pathogenic? Proteomics. 2015;15(2-3):260–71. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schorey JS, Cheng Y, Singh PP, Smith VL. Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(1):24–43. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. The Journal of cell biology. 2013;200(4):373–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minciacchi VR, You S, Spinelli C, Morley S, Zandian M, Aspuria PJ, et al. Large oncosomes contain distinct protein cargo and represent a separate functional class of tumor-derived extracellular vesicles. Oncotarget. 2015;6(13):11327–41. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson RJ, Lim JW, Moritz RL, Mathivanan S. Exosomes: proteomic insights and diagnostic potential. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2009;6(3):267–83. doi: 10.1586/epr.09.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christianson HC, Svensson KJ, Belting M. Exosome and microvesicle mediated phene transfer in mammalian cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;28:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajendran L, Bali J, Barr MM, Court FA, Kramer-Albers EM, Picou F, et al. Emerging roles of extracellular vesicles in the nervous system. J Neurosci. 2014;34(46):15482–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3258-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Admyre C, Johansson SM, Qazi KR, Filen JJ, Lahesmaa R, Norman M, et al. Exosomes with immune modulatory features are present in human breast milk. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1969–78. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.French KC, Antonyak MA, Cerione RA. Extracellular vesicle docking at the cellular port: Extracellular vesicle binding and uptake. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;67:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flemming JP, Hill BL, Haque MW, Raad J, Bonder CS, Harshyne LA, et al. miRNA- and cytokine-associated extracellular vesicles mediate squamous cell carcinomas. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9(1):1790159. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2020.1790159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26(4):239–57. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ihara T, Yamamoto T, Sugamata M, Okumura H, Ueno Y. The process of ultrastructural changes from nuclei to apoptotic body. Virchows Arch. 1998;433(5):443–7. doi: 10.1007/s004280050272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergsmedh A, Szeles A, Henriksson M, Bratt A, Folkman MJ, Spetz AL, et al. Horizontal transfer of oncogenes by uptake of apoptotic bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(11):6407–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101129998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muralidharan-Chari V, Clancy JW, Sedgwick A, D'Souza-Schorey C. Microvesicles: mediators of extracellular communication during cancer progression. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 10):1603–11. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozlov MM, Campelo F, Liska N, Chernomordik LV, Marrink SJ, McMahon HT. Mechanisms shaping cell membranes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;29:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nabhan JF, Hu R, Oh RS, Cohen SN, Lu Q. Formation and release of arrestin domain-containing protein 1-mediated microvesicles (ARMMs) at plasma membrane by recruitment of TSG101 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(11):4146–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200448109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellon-Cardenas O, Clancy J, Uwimpuhwe H, D'Souza-Schorey C. ARF6-regulated endocytosis of growth factor receptors links cadherin-based adhesion to canonical Wnt signaling in epithelia. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(15):2963–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01698-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P. ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(5):347–58. doi: 10.1038/nrm1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Freitas D, Kim HS, Fabijanic K, Li Z, Chen H, et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(3):332–43. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0040-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yekula A, Minciacchi VR, Morello M, Shao H, Park Y, Zhang X, et al. Large and small extracellular vesicles released by glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9(1):1689784. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1689784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapitz A, Arbelaiz A, Olaizola P, Aranburu A, Bujanda L, Perugorria MJ, et al. Extracellular Vesicles in Hepatobiliary Malignancies. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2270. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urabe F, Kosaka N, Ito K, Kimura T, Egawa S, Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicles as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancer. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2020;318(1):C29–C39. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00280.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahlert C, Melo SA, Protopopov A, Tang J, Seth S, Koch M, et al. Identification of double-stranded genomic DNA spanning all chromosomes with mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the serum exosomes of patients with pancreatic cancer. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(7):3869–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.532267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melo SA, Luecke LB, Kahlert C, Fernandez AF, Gammon ST, Kaye J, et al. Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;523(7559):177–82. doi: 10.1038/nature14581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson AG, Gray E, Heman-Ackah SM, Mager I, Talbot K, Andaloussi SE, et al. Extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative disease - pathogenesis to biomarkers. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(6):346–57. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boulanger CM, Loyer X, Rautou PE, Amabile N. Extracellular vesicles in coronary artery disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(5):259–72. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karpman D, Stahl AL, Arvidsson I. Extracellular vesicles in renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(9):545–62. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szabo G, Momen-Heravi F. Extracellular vesicles in liver disease and potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(8):455–66. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian J, Casella G, Zhang Y, Rostami A, Li X. Potential roles of extracellular vesicles in the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of autoimmune diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(4):620–32. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.39629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng J, Wang W, Hua S, Liu L. Roles of Extracellular Vesicles in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2018;12:1178223418767666. doi: 10.1177/1178223418767666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadota T, Yoshioka Y, Fujita Y, Kuwano K, Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicles in lung cancer-From bench to bedside. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;67:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu R, Rai A, Chen M, Suwakulsiri W, Greening DW, Simpson RJ. Extracellular vesicles in cancer - implications for future improvements in cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(10):617–38. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wermuth PJ, Piera-Velazquez S, Rosenbloom J, Jimenez SA. Existing and novel biomarkers for precision medicine in systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(7):421–32. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linxweiler J, Junker K. Extracellular vesicles in urological malignancies: an update. Nat Rev Urol. 2020;17(1):11–27. doi: 10.1038/s41585-019-0261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyiadzis M, Whiteside TL. The emerging roles of tumor-derived exosomes in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2017;31(6):1259–68. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang L, Ni J, Zhu Y, Pang B, Graham P, Zhang H, et al. Liquid biopsy in ovarian cancer: recent advances in circulating extracellular vesicle detection for early diagnosis and monitoring progression. Theranostics. 2019;9(14):4130–40. doi: 10.7150/thno.34692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villa F, Quarto R, Tasso R. Extracellular Vesicles as Natural, Safe and Efficient Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(11). doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turturici G, Tinnirello R, Sconzo G, Geraci F. Extracellular membrane vesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication: advantages and disadvantages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;306(7):C621–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ha D, Yang N, Nadithe V. Exosomes as therapeutic drug carriers and delivery vehicles across biological membranes: current perspectives and future challenges. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6(4):287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antimisiaris SG, Mourtas S, Marazioti A. Exosomes and Exosome-Inspired Vesicles for Targeted Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(4). doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10040218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aryani A, Denecke B. Exosomes as a Nanodelivery System: a Key to the Future of Neuromedicine? Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(2):818–34. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9054-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bunggulawa EJ, Wang W, Yin T, Wang N, Durkan C, Wang Y, et al. Recent advancements in the use of exosomes as drug delivery systems. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018;16(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0403-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li YJ, Wu JY, Hu XB, Wang JM, Xiang DX. Autologous cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles as drug-delivery systems: a systematic review of preclinical and clinical findings and translational implications. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2019;14(4):493–509. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2018-0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tiedemann K, Sadvakassova G, Mikolajewicz N, Juhas M, Sabirova Z, Tabaries S, et al. Exosomal Release of L-Plastin by Breast Cancer Cells Facilitates Metastatic Bone Osteolysis. Translational oncology. 2019;12(3):462–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raimondi L, De Luca A, Fontana S, Amodio N, Costa V, Carina V, et al. Multiple Myeloma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Induce Osteoclastogenesis through the Activation of the XBP1/IRE1α Axis. Cancers. 2020;12(8). doi: 10.3390/cancers12082167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faict S, Muller J, De Veirman K, De Bruyne E, Maes K, Vrancken L, et al. Exosomes play a role in multiple myeloma bone disease and tumor development by targeting osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8(11):105. doi: 10.1038/s41408-018-0139-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.*.Loftus A, Cappariello A, George C, Ucci A, Shefferd K, Green A, et al. Extracellular Vesicles From Osteotropic Breast Cancer Cells Affect Bone Resident Cells. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2020;35(2):396–412. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3891.This study demonstrates that cancer cells targeted to bone can impact bone remodeling.

- 52.Liu X, Cao M, Palomares M, Wu X, Li A, Yan W, et al. Metastatic breast cancer cells overexpress and secrete miR-218 to regulate type I collagen deposition by osteoblasts. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-1059-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raimondo S, Urzì O, Conigliaro A, Bosco GL, Parisi S, Carlisi M, et al. Extracellular Vesicle microRNAs Contribute to the Osteogenic Inhibition of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers. 2020;12(2). doi: 10.3390/cancers12020449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakata R, Shimada H, Fernandez GE, Fanter R, Fabbri M, Malvar J, et al. Contribution of neuroblastoma-derived exosomes to the production of pro-tumorigenic signals by bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. J Extracell Vesicles. 2017;6(1):1332941. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1332941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.**.Peinado H, Aleckovic M, Lavotshkin S, Matei I, Costa-Silva B, Moreno-Bueno G, et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med. 2012;18(6):883–91. doi: 10.1038/nm.2753nm.2753 [pii]. The first demonstration that exosomes from a primary tumor target bone marrow and establish a pre-metastatic niche that promotes metastatic growth.

- 56.Dai J, Escara-Wilke J, Keller JM, Jung Y, Taichman RS, Pienta KJ, et al. Primary prostate cancer educates bone stroma through exosomal pyruvate kinase M2 to promote bone metastasis. J Exp Med. 2019;216(12):2883–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vallabhaneni KC, Penfornis P, Xing F, Hassler Y, Adams KV, Mo YY, et al. Stromal cell extracellular vesicular cargo mediated regulation of breast cancer cell metastasis via ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 N pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(66):109861–76. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bliss SA, Sinha G, Sandiford OA, Williams LM, Engelberth DJ, Guiro K, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Stimulate Cycling Quiescence and Early Breast Cancer Dormancy in Bone Marrow. Cancer Res. 2016;76(19):5832–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-16-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ono M, Kosaka N, Tominaga N, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Takahashi RU, et al. Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells contain a microRNA that promotes dormancy in metastatic breast cancer cells. Sci Signal. 2014;7(332):ra63. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.*.Walker ND, Elias M, Guiro K, Bhatia R, Greco SJ, Bryan M, et al. Exosomes from differentially activated macrophages influence dormancy or resurgence of breast cancer cells within bone marrow stroma. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(2):59. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1304-z.Describes how exosome derived from immunce cells can influence the progresion of breast within the bone marrow.

- 61.Shupp AB, Kolb AD, Mukhopadhyay D, Bussard KM. Cancer Metastases to Bone: Concepts, Mechanisms, and Interactions with Bone Osteoblasts. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(6). doi: 10.3390/cancers10060182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morhayim J, van de Peppel J, Demmers JAA, Kocer G, Nigg AL, van Driel M, et al. Proteomic signatures of extracellular vesicles secreted by nonmineralizing and mineralizing human osteoblasts and stimulation of tumor cell growth. The FASEB Journal. 2015;29(1):274–85. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-261404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]