Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Mechanical thrombectomy helps prevent disability in patients with acute ischemic stroke involving occlusion of a large cerebral vessel. Thrombectomy requires procedural expertise and not all hospitals have the staff to perform this intervention. Few population-wide data exist regarding access to mechanical thrombectomy.

Methods:

We examined access to thrombectomy for ischemic stroke using discharge data from calendar years 2016–2018 from all nonfederal emergency departments and acute care hospitals across 11 U.S. states encompassing 80 million residents. Facilities were classified as hubs if they performed mechanical thrombectomy, gateways if they transferred patients who ultimately underwent mechanical thrombectomy, and gaps otherwise. We used standard descriptive statistics and unadjusted logistic regression models in our primary analyses.

Results:

Among 205,681 patients with ischemic stroke, 100,139 (48.7%; 95% CI, 48.5–48.9%) initially received care at a thrombectomy hub, 72,534 (35.3%; 95% CI, 35.1–35.5%) at a thrombectomy gateway, and 33,008 (16.0%; 95% CI, 15.9–16.2%) at a thrombectomy gap. Patients who initially received care at thrombectomy gateways were substantially less likely to ultimately undergo thrombectomy than patients who initially received care at thrombectomy hubs (odds ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.25–0.28). Rural patients had particularly limited access: 27.7% (95% CI, 26.9–28.6%) of such patients initially received care at hubs versus 69.5% (95% CI, 69.1–69.9%) of urban patients. For 93.8% (95% CI, 93.6–94.0%) of stroke patients at gateways, that initial facility was capable of delivering intravenous thrombolysis, compared with 76.3% (95% CI, 75.8–76.7%) of patients at gaps. Our findings were unchanged in models adjusted for demographics and comorbidities, and persisted across multiple sensitivity analyses, including analyses adjusting for estimated stroke severity.

Conclusions:

We found that a substantial proportion of ischemic stroke patients across the United States lacked access to thrombectomy even after accounting for interhospital transfers. U.S. systems of stroke care require further development to optimize thrombectomy access.

Beginning in late 2014, several randomized clinical trials demonstrated that mechanical thrombectomy helps restore brain perfusion and prevent disability in patients with acute ischemic stroke involving occlusion of a large cerebral vessel.1 On this basis, thrombectomy rapidly became part of the standard of care for ischemic stroke.2 Thrombectomy should be performed as rapidly as possible because delays in reperfusion generally result in less treatment benefit and recovery.3,4 However, thrombectomy requires procedural expertise and not all hospitals have the staff to perform this intervention. As a result, access to thrombectomy often requires systems of care that can appropriately route patients in the prehospital setting or transfer them between facilities.2 It is accepted that systems of care should provide broad and timely access to thrombectomy for patients with ischemic stroke and large-vessel occlusion.2 It is unclear whether current systems of care provide sufficient access to thrombectomy across the United States.

Using population-wide data from 11 geographically dispersed states, we sought to address the following questions: (1) What percent of U.S. stroke patients have access to thrombectomy? (2) What are the characteristics of U.S. stroke patients who lack access to thrombectomy? (3) What are the characteristics of U.S. medical facilities that lack access to stroke thrombectomy?

Methods

Design

To address these questions, we used all-payer claims data on all discharges from all nonfederal emergency departments and acute care hospitals in Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New York, Utah, Vermont, and Wisconsin. Trained analysts at each nonfederal acute care facility in these states used automated online reporting software to provide standardized discharge data to the respective state health department, which then performed a multistep quality assurance check to identify invalid or inconsistent records before making the data publicly available via the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.5 The states included in this analysis have a combined population of approximately 80 million residents, comprising 25% of the total U.S. population.6 Data were available from calendar year 2016 for all 11 states; 2017 for Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Utah, and Wisconsin; and 2018 for Iowa. We followed the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Data guidelines.7 The Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board certified our study as exempt from review and waived the requirement for informed consent. We will share our program code and other analytical methods upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. We cannot directly share our data under the terms of our data use agreement, but the data are publicly available from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

Patient Population

We used a previously validated International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) hospital discharge diagnosis code to identify adults hospitalized with ischemic stroke (Supplemental Table I).8 Multiple records from an interfacility transfer were considered part of the same event; records from transfers were probabilistically linked using variables for facility, visit date, length of stay, and discharge disposition. For patients with multiple events during the study period, we included only the first. Among cases of interfacility transfer, we excluded as mimics those with a stroke diagnosis at the initial facility but no such diagnosis at the receiving facility. We also excluded patients transferred to a hospital for which we had no linked records (i.e., transfers across state lines or to federal facilities such as Veterans Administration hospitals).

Patient Characteristics

We identified age, sex, race-ethnicity, and insurance status from standardized hospital discharge data. We used standard methods to calculate the Charlson comorbidity index.9 Patients’ urban-rural location of residence was categorized using their ZIP code and the classification scheme developed by the National Center for Health Statistics (Supplemental Table II).10 Using data from the American Community Survey and previously published methods,11 six variables related to wealth, income, education, and occupation were summarized into a single socioeconomic advantage score and aggregated at the level of localities defined by Federal Information Processing Standard codes.

Endovascular Treatments for Stroke

Endovascular treatments for stroke were ascertained using previously validated ICD-10-CM hospital procedure codes (Supplemental Table I).12 Our primary definition included only mechanical thrombectomy; in a sensitivity analysis, we used an expanded definition of endovascular stroke therapy that included intra-arterial thrombolysis and intracranial angioplasty/stenting.

Facility Characteristics

From the American Hospital Association’s annual survey files,13 we noted each facility’s name, address, total number of beds, whether it was a member of the Association of American Medical Colleges, and whether it had any residency programs approved by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Facility ownership was classified as government, private nonprofit, or private for-profit.

We calculated facilities’ volumes of ischemic stroke hospitalizations and stroke thrombectomies. We classified a facility as a thrombectomy hub if it performed mechanical thrombectomy in at least one stroke patient during the study period, a thrombectomy gateway if it did not perform any stroke thrombectomies but transferred out at least one stroke patient who received stroke thrombectomy at the receiving hospital, and a thrombectomy gap otherwise. We used this approach because, although it is difficult to gauge in retrospect which individual patients should have undergone thrombectomy, the initial facility’s thrombectomy status reflects whether thrombectomy was ultimately available in at least one instance if indicated.

Using facility addresses and a Google Maps application programming interface, we calculated the distance to the nearest thrombectomy hub for each thrombectomy gateway and gap. To assess the availability of other clinical services relevant to the acute care of ischemic stroke, we used ICD-10-CM procedure codes (Supplemental Table I) to determine whether facilities ever performed intravenous thrombolysis for ischemic stroke, mechanical ventilation for hospitalized patients, or any type of inpatient neurosurgical, cardiac, or vascular intervention.

Geographic Visualization

To visually assess thrombectomy access according to geography, we calculated the proportion of stroke patients residing within each ZIP code who were initially cared for at a stroke thrombectomy hub. We overlaid this proportion onto a U.S. map using the latitude and longitude of each ZIP code’s geographic center. For this analysis, we excluded ZIP codes with <11 stroke patients during the study period. To avoid misclassifying thrombectomy access in ZIP codes near state borders, we excluded ZIP codes in which any stroke patient had a possible transfer across state lines.

Statistical Analysis

In our primary analyses, we used standard descriptive statistics with binomial exact confidence intervals (CI) and performed unadjusted comparisons using the chi-square test or t-test. In secondary analyses, we used logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, race-ethnicity, insurance, socioeconomic status, urban-rural location of residence, and the Charlson comorbidity index. Multinomial logistic regression was used to analyze presentation to thrombectomy hubs versus gateways versus gaps. Multiple logistic regression was used to compare patients’ access to relevant clinical services at hubs versus gateways versus gaps, as well as to compare the odds of thrombectomy among patients presenting to hubs versus gateways. After fitting models, we calculated adjusted probabilities of the outcome for each level of a given variable of interest while holding covariates at their means. To assess trends from 2016 to 2018, we included an interaction term between the covariate of interest and calendar year. All hypothesis tests were 2-sided and the threshold of statistical significance was set at α = 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by H.K. and A.C. using Stata/MP v15, Exploratory v5.1.5.1, and Python v3.8.2.

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed several sensitivity analyses. First, we adjusted for estimated stroke severity using an adapted method for administrative data.14 Second, we limited the stroke population to those with a probable large-vessel occlusion, defined as a documented National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score ≥12, a threshold that has been shown to be 90% specific for identifying patients with large-vessel occlusion.15 To determine NIHSS scores, we abstracted all available ICD-10-CM encoding of NIHSS data, which have been previously validated.16 Third, we limited the stroke population to those who received intravenous thrombolysis. Fourth, we limited the stroke population to those presenting to facilities that cared for at least 30 strokes during the study period. Fifth, we excluded thrombectomy hubs that performed <10 thrombectomies during the study period. Sixth, we used an expanded definition of endovascular stroke therapy that included intra-arterial thrombolysis and intracranial angioplasty/stenting.

Results

Access to Mechanical Thrombectomy

Among 12,311,736 emergency department visits and hospitalizations involving 7,581,668 adults (Supplemental Figure I), we identified 205,681 patients with ischemic stroke, equating to an age-standardized incidence rate of 2.1 cases per 1,000 adults per year. Of these patients with ischemic stroke, 100,139 (48.7%; 95% CI, 48.5–48.9%) were initially cared for at a thrombectomy hub, 72,534 (35.3%; 95% CI, 35.1–35.5%) at a thrombectomy gateway, and 33,008 (16.0%; 95% CI, 15.9–16.2%) at a thrombectomy gap (Table 1). These proportions were not substantially different across sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Table III) and did not substantially change across study years (Supplemental Table IV). Of the 100,139 stroke patients who were initially cared for at a thrombectomy hub, 4,794 (4.8%) underwent thrombectomy. Of the 72,534 initially at a thrombectomy gateway, 956 (1.3%) were transferred and underwent thrombectomy at the receiving hospital. Patients presenting to thrombectomy gateways were substantially less likely to undergo thrombectomy than patients presenting to thrombectomy hubs (odds ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.25–0.28). This finding was unchanged after adjustment for demographics and comorbidities (odds ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.25–0.28) and persisted across all sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Table V).

Table 1.

Initial Presentation with Ischemic Stroke to Thrombectomy Hubs versus Gateways versus Gaps*.

| Facility Type† | All Patients (N = 205,681) | Thrombectomy Patients (N = 5,750) |

|---|---|---|

| Hub | 100,139 (48.7) | 4,794 (83.4) |

| Gateway | 72,534 (35.3) | 956 (16.6)‡ |

| Gap | 33,008 (16.0) | 0 |

We classified a facility as a thrombectomy hub if it performed stroke thrombectomy in at least one stroke patient during the study period, a thrombectomy gateway if it did not perform any stroke thrombectomies but transferred out at least one stroke patient who received stroke thrombectomy at the receiving hospital, and a thrombectomy gap otherwise.

Data are presented as number (%).

These patients underwent thrombectomy after transfer from the initial gateway facility to a hub.

Patient Characteristics and Access to Thrombectomy

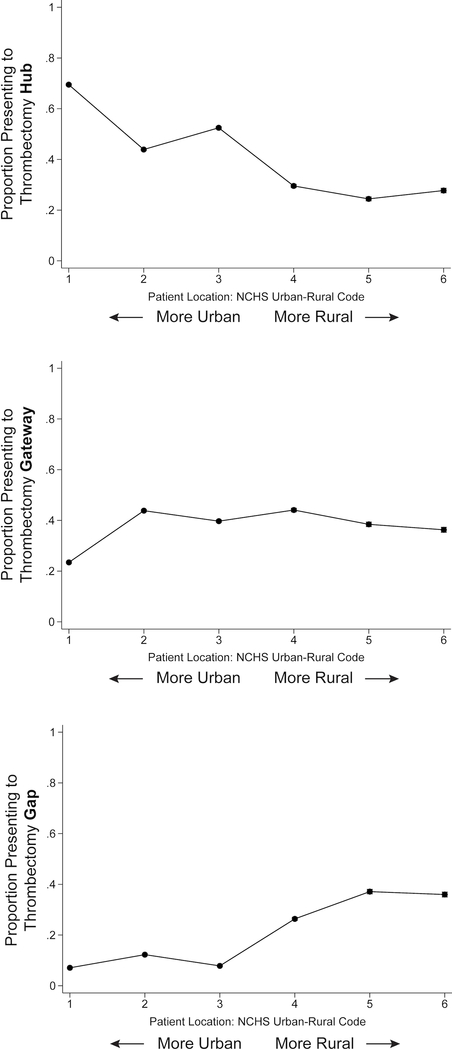

Ischemic stroke patients living in more rural locations were substantially more likely to initially receive care at thrombectomy gaps as opposed to hubs (P <0.001) (Figure 1) (Supplemental Table VI). For example, 36.0% (95% CI, 35.0–36.9%) of patients in the most rural counties presented to a thrombectomy gap versus 7.1% (95% CI, 6.9–7.3%) of patients residing in the most urban counties. Patients in the most urban counties were the most likely to initially receive care at a thrombectomy hub (69.5%; 95% CI, 69.1–69.9%), substantially more so than even the suburban counties slightly outside the urban core (43.9%; 95% CI, 43.5–44.3%). The geographic disparities in thrombectomy access persisted after adjustment for other demographics (Supplemental Figure II) and in all sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Figure III). These geographic disparities were also apparent when mapping the proportion of ischemic stroke patients within each ZIP code who were initially cared for at a thrombectomy hub (Figure 2; Supplemental Figure IV).

Figure 1.

Proportions of Patients with Ischemic Stroke Presenting to Thrombectomy Hubs, Gateways, and Gaps, by Urban-Rural Location of Residence.

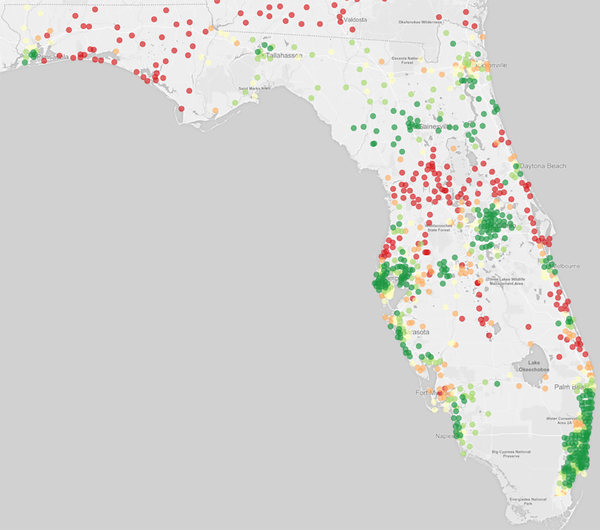

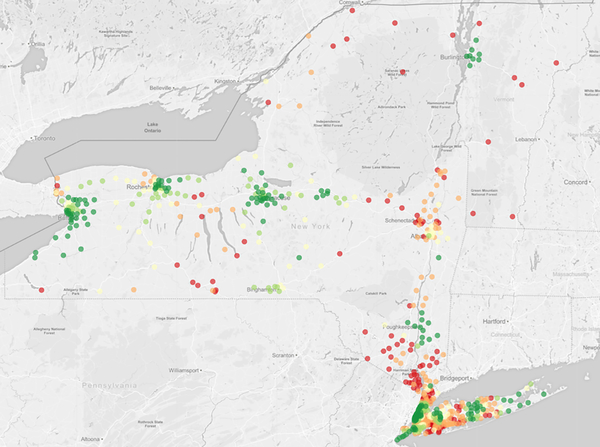

Figure 2. Proportion of Patients with Ischemic Stroke Presenting to a Thrombectomy Hub, by ZIP Code.

Maps from the two most populous states are shown: (2a) Florida and (2b) New York (along with Vermont adjacent). Maps from other states are shown in Supplemental Figure IV. Proportions are mapped according to the color scheme below:

81% - 100%

81% - 100%

61% - 80%

61% - 80%

41% - 60%

41% - 60%

21% - 40%

21% - 40%

0% - 20%

0% - 20%

Facility Characteristics and Access to Thrombectomy

The 205,681 ischemic stroke patients in our sample initially presented to 972 unique facilities, of which 148 (15.2%) could not be linked to the American Hospital Association’s annual survey files because the necessary linkage variable was not provided by the state of Georgia. Thrombectomy hubs had more beds and ischemic stroke cases than thrombectomy gateways, which in turn had greater capacity and volumes than thrombectomy gaps (Table 2). The mean distance to the nearest thrombectomy hub was shorter for thrombectomy gateways (30 ± 29 miles) than for gaps (53 ± 66 miles) (P <0.001). More ischemic stroke patients at thrombectomy gateways had access to clinical services potentially relevant to acute stroke care than did patients presenting to thrombectomy gaps, particularly intravenous thrombolysis (93.8% versus 76.3%; P <0.001) (Table 3); these differences were similar after adjustment for demographics and comorbidities (Supplemental Table VII).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Facilities Initially Receiving Patients with Ischemic Stroke, Stratified by Facilities’ Access to Thrombectomy*.

| Facility Characteristic† | Hub (N = 139) | Gateway (N = 241) | Gap (N = 444) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cases‡, median (IQR), no. | 581 (358–803) | 160 (72–321) | 18 (4–76) |

| Thrombectomy cases‡, median (IQR), no. | 20 (4–49) | - | - |

| Total beds, median (IQR), no. | 423 (280–644) | 147 (67–245) | 70 (25–149) |

| Facility control | |||

| Government | 16 (11.5) | 14 (5.8) | 60 (13.5) |

| Private nonprofit | 96 (69.1) | 179 (74.3) | 272 (61.3) |

| Private for-profit | 27 (19.4) | 48 (19.9) | 112 (25.2) |

| Member of AAMC | 44 (31.7) | 3 (1.2) | 13 (2.9) |

| ACGME-approved residency program | 107 (77.0) | 74 (30.7) | 114 (25.7) |

| Distance to nearest hub, mean (SD), miles | - | 30 (29) | 53 (66) |

| Clinical services available on site | |||

| Intravenous thrombolysis | 139 (100) | 177 (73.4) | 138 (31.1) |

| Mechanical ventilation§ | 139 (100) | 223 (92.5) | 312 (70.3) |

| Any neurosurgical intervention | 139 (100) | 221 (91.7) | 278 (62.6) |

| Any cardiac intervention | 139 (100) | 226 (93.8) | 314 (70.7) |

| Any vascular intervention | 139 (100) | 228 (94.6) | 341 (76.8) |

Abbreviations: AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

We classified a facility as a thrombectomy hub if it performed stroke thrombectomy in at least one stroke patient during the study period, a thrombectomy gateway if it did not perform any stroke thrombectomies but transferred out at least one stroke patient who received stroke thrombectomy at the receiving hospital, and a thrombectomy gap otherwise.

Data are presented as number (%) unless otherwise specified.

Cases during entire study period.

For patients admitted to the hospital, not patients in the emergency department.

Table 3.

Relevant Clinical Services Available to Ischemic Stroke Patients at Initial Facility*.

| Clinical Service† | Thrombectomy Gateway (N = 72,534) | Thrombectomy Gap (N = 33,008) |

|---|---|---|

| Intravenous thrombolysis | 68,027 (93.8) | 25,179 (76.3) |

| Mechanical ventilation‡ | 71,942 (99.2) | 31,722 (96.1) |

| Any neurosurgical intervention | 71,731 (98.9) | 31,143 (94.4) |

| Any cardiac intervention | 72,074 (99.4) | 31,585 (95.7) |

| Any vascular intervention | 72,262 (99.6) | 31,987 (96.9) |

We classified a facility as a thrombectomy hub for ischemic stroke if it performed stroke thrombectomy in at least one stroke patient during the study period, a thrombectomy gateway if it did not perform any stroke thrombectomies but transferred out at least one stroke patient who received stroke thrombectomy at the receiving hospital, and a thrombectomy gap otherwise. Proportions between thrombectomy gateways and gaps were significantly different for all clinical services (P <0.001).

A clinical service was considered to be available if any procedure within that broad category was performed at a site at least once during the study period. Data are presented as number (%).

For patients admitted to the hospital, not patients in the emergency department.

Discussion

Using comprehensive population-wide data from 11 U.S. states with 80 million residents, we found that fewer than 50% of patients with ischemic stroke initially received care at facilities capable of mechanical thrombectomy. Non-urban patients were less likely to initially receive care at thrombectomy hubs than residents of urban cores, and rural patients were particularly likely to present to thrombectomy gaps that did not offer transfer to a thrombectomy-capable hospital. Intravenous thrombolysis was available to approximately 95% of patients presenting to thrombectomy gateways and 75% of patients presenting to thrombectomy gaps.

Prior studies have used modeling to indirectly estimate access to stroke thrombectomy.17–25 Other studies have assessed patients transferred in for thrombectomy26–28 but did not include patients who remained at gateway or gap facilities or those facilities’ characteristics. Few data exist on the actual state of access to thrombectomy across broad populations in the United States and the characteristics of patients and facilities lacking access to thrombectomy. Given this uncertainty, our findings may inform the active debate29–32 about how to optimize systems of care for thrombectomy.

Our findings have two potential implications. First, population-wide access to stroke thrombectomy in the United States appears broadly suboptimal as of the end of 2018. Even in urban cores, only two-thirds of patients had rapid access to thrombectomy. These findings highlight the urgency of continuing to refine systems of care to optimize thrombectomy access at a broad level. Second, non-urban residents are the most affected by a lack of thrombectomy access. Suburban patients who did not present to thrombectomy hubs mostly presented to gateway facilities, and almost all of these patients were at facilities that appeared to have basic infrastructure for the acute care of arterial ischemic disease, especially in regards to intravenous thrombolysis. It may be possible to convert some of these facilities into thrombectomy hubs. Expansion efforts should be mindful of the need for sufficient training and procedural volumes to maintain skills and ensure good outcomes.28 In some cases, these constraints may be partly addressable by traveling teams of interventionalists33 or systems for remote operation of catheters or remote supervision of procedures by experts.34 In other cases, it may be better to work on improving accurate diagnosis of large-vessel occlusion and protocols to transfer those with a high likelihood of large-vessel occlusion directly to larger-volume hubs. Attempts to improve systems of care should be mindful of the importance of not only more widespread access but also faster access to thrombectomy.4 Further away from urban cores, approximately one-third of rural patients presented to thrombectomy gaps and thus appeared to have no access to thrombectomy even after accounting for interhospital transfer. Many of these patients were at low-volume facilities without basic infrastructural elements for acute stroke care—a quarter of these patients were at facilities that did not provide intravenous thrombolysis. Such patients may benefit from bypassing these thrombectomy gaps altogether by means of improved prehospital triage systems to identify those with a large-vessel occlusion and reroute them to thrombectomy hubs or at least gateways.35 Such efforts should be mindful of the benefit of rapid intravenous thrombolysis at the nearest capable hospital for the majority of stroke patients who do not have a large-vessel occlusion.21 Regardless of the approach, the challenges are acute, given the supply of trained neurointerventionalists, the clinical heterogeneity of ischemic stroke, and the low proportion of ischemic stroke patients who qualify for thrombectomy. The optimal system of care will vary by location and will need to be determined by local stakeholders.

Our study should be considered in light of its limitations. First, we lacked data from the entire United States, particularly from Western states. On the other hand, we had comprehensive data from 11 heterogeneous, geographically dispersed states encompassing 80 million residents. Second, we analyzed administrative data rather than review medical records or prospectively ascertain events. However, a comprehensive, population-based analysis across the United States is not possible without administrative data. To mitigate misclassification, we used validated codes to define key variables. Third, we lacked data on the availability of certain important clinical services such as telestroke consultation, and we lacked data on the numbers of interventionalists and the times during the week when interventional treatments were available at each hospital. Fourth, our latest data were from the end of 2018 and thrombectomy access may have improved in the last 2 years. The all-payer claims data we used are released with a lag time of several years, and we used the latest available data, so periodic analyses will be required to assess trends in thrombectomy access.

Our findings pertain to a major medical and public health problem, given that stroke is a leading cause of disability and death.36 Randomized clinical trials have proven that thrombectomy reduces disability in the most severe cases of ischemic stroke.1 There is widespread agreement that systems of care should provide equitable access to thrombectomy.2 We found that a substantial proportion of ischemic stroke patients across the United States lacked access to thrombectomy even after accounting for interhospital transfers. Our study suggests that systems of stroke care in the United States require substantial further development to optimize access to thrombectomy, and our data may inform efforts to improve access to this proven therapy.

Supplementary Material

Sources of Funding:

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant R01NS097443 to Kamel and R01NS104143 to Pandya).

Disclosures: Dr. Kamel serves as co-PI for the NIH-funded ARCADIA trial which receives in-kind study drug from the BMS-Pfizer Alliance and in-kind study assays from Roche Diagnostics, serves as a steering committee member of Medtronic’s Stroke AF trial (uncompensated), serves as Deputy Editor for JAMA Neurology, serves on an endpoint adjudication committee for a trial of empagliflozin for Boehringer-Ingelheim, and has served on an advisory board for Roivant Sciences related to Factor XI inhibition. Dr Parikh reports grants from Florence Gould Foundation during the conduct of the study; grants from Leon Levy Foundation Fellowship in Neuroscience and grants from NY State Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program outside the submitted work. Dr. Schwamm reports grants from NINDS and grants from PCORI outside the submitted work; chairmanship of the GWTG-Stroke Systems of Care Advisory Group and the American Stroke Association Advisory Committee; and the following relationships of research grants or consulting to companies that manufacture products for thrombolysis or thrombectomy (even when the interaction involves non-thrombolysis products): scientific consultant regarding trial design and conduct to Genentech (late window thrombolysis) and member of steering committee (TIMELESS NCT03785678); user interface design and usability to LifeImage; stroke systems of care to the Massachusetts Dept of Public Health; member of a Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) for Penumbra (MIND NCT03342664, CURRENT); Diffusion Pharma PHAST-TSC NCT03763929,); National PI or member of National Steering Committee for Medtronic (Stroke AF NCT02700945); PI, late window thrombolysis trial, NINDS (P50NS051343, MR WITNESS NCT01282242; last payment 2017); PI, StrokeNet Network NINDS (New England Regional Coordinating Center U24NS107243). Dr. Zachrison reports grants from Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality during the conduct of the study; grants from NIH/NINDS and grants from American College of Emergency Physicians outside the submitted work. Dr. Adeoye serves as founder and equity holder for Sense Diagnostics, Inc. Dr. Saver has received funding for services as a scientific consultant regarding rigorous trial design and conduct to Medtronic, Stryker, Cerenovus, and Boehringer Ingelheim (prevention only), and stock options for services as a scientific consultant regarding rigorous trial design and conduct to Rapid Medical. Dr. Nogueira reports consulting fees for advisory roles with Medtronic, Stryker Neurovascular, and stock options for advisory roles with Cerebrotech, and Perfuze. Dr. Nogueira has received personal compensation for serving as a principal investigator for Cerenovus/Neuravi Ltd, Imperative Care Inc, and Phenox, Inc; on the physician advisory board for Anaconda Biomed SL, Genentech, Inc, and Prolong Pharmaceuticals; and on a steering committee for Biogen. Dr. Nogueira has received grants/research support from Koninklijke Philips NV, the Ministry of Health (Brazil), and Sensome and has held stock options in Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals Inc, Brainomix, Ceretrieve Ltd, Corindus, Inc, Vesalio, LLC, and Viz.ai, Inc. Dr. Navi serves on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board for the PCORI-funded TRAVERSE trial and has received personal compensation for medical-legal consulting on stroke.

Abbreviations

- ICD-10-CM

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification

- NIHSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Footnotes

References

- 1.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DWJ, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, Dávalos A, Majoie CBLM, van der Lugt A, de Miquel MA, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. The Lancet. 2016;387:1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, Coffey CS, Hoh BL, Jauch EC, Johnston KC, Johnston SC, Khalessi AA, Kidwell CS, et al. 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Focused Update of the 2013 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Regarding Endovascular Treatment: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46:3020–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahan R, Saver JL, Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC, Liang L, Matsouaka RA, Xian Y, Holmes DN, Peterson ED, Yavagal D, et al. Association Between Time to Treatment With Endovascular Reperfusion Therapy and Outcomes in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated in Clinical Practice. JAMA. 2019;322:252–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunz WG, Hunink MG, Almekhlafi MA, Menon BK, Saver JL, Dippel DWJ, Majoie C, Jovin TG, Davalos A, Bracard S, et al. Public health and cost consequences of time delays to thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2020;95:e2465–e2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov. Accessed February 13, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Census QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219. Accessed March 29, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, Sorensen HT, von Elm E, Langan SM. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang TE, Tong X, George MG, Coleman King SM, Yin X, O’Brien S, Ibrahim G, Liskay A, Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Program t, Wiltz JL. Trends and Factors Associated With Concordance Between International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification Codes and Stroke Clinical Diagnoses. Stroke. 2019;50:1959–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, by Ingram Deborah D. and Franco Sheila. National Center for Health Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/CMF/Urbanization-Methodology.html. Accessed February 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto FJ, Sorlie P, Szklo M, Tyroler HA, Watson RL. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Coster C, Li B, Quan H. Comparison and validity of procedures coded With ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CA/CCI. Med Care. 2008;46:627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annual Survey. American Hospital Association. https://www.ahadata.com/academics-researchers. Accessed March 29, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu AYX, Austin PC, Rashid M, Fang J, Porter J, Hill MD, Kapral MK. Deriving a Passive Surveillance Stroke Severity Indicator From Routinely Collected Administrative Data: The PaSSV Indicator. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e006269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maas MB, Furie KL, Lev MH, Ay H, Singhal AB, Greer DM, Harris GJ, Halpern E, Koroshetz WJ, Smith WS. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score is poorly predictive of proximal occlusion in acute cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2009;40:2988–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saber H, Saver JL. Distributional Validity and Prognostic Power of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale in US Administrative Claims Data. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:606–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holodinsky JK, Williamson TS, Demchuk AM, Zhao H, Zhu L, Francis MJ, Goyal M, Hill MD, Kamal N. Modeling Stroke Patient Transport for All Patients With Suspected Large-Vessel Occlusion. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1477–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali A, Zachrison KS, Eschenfeldt PC, Schwamm LH, Hur C. Optimization of Prehospital Triage of Patients With Suspected Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:2532–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh NS, Chatterjee A, Diaz I, Pandya A, Merkler AE, Gialdini G, Kummer BR, Mir SA, Lerario MP, Fink ME, et al. Modeling the Impact of Interhospital Transfer Network Design on Stroke Outcomes in a Large City. Stroke. 2018;49:370–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullen MT, Branas CC, Kasner SE, Wolff C, Williams JC, Albright KC, Carr BG. Optimization modeling to maximize population access to comprehensive stroke centers. Neurology. 2015;84:1196–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milne MS, Holodinsky JK, Hill MD, Nygren A, Qiu C, Goyal M, Kamal N. Drip ‘n Ship Versus Mothership for Endovascular Treatment: Modeling the Best Transportation Options for Optimal Outcomes. Stroke. 2017;48:791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarraj A, Savitz S, Pujara D, Kamal H, Carroll K, Shaker F, Reddy S, Parsha K, Fournier LE, Jones EM, et al. Endovascular Thrombectomy for Acute Ischemic Strokes: Current US Access Paradigms and Optimization Methodology. Stroke. 2020;51:1207–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosson N, Gausche-Hill M, Saver JL, Sanossian N, Tadeo R, Clare C, Perez L, Williams M, Rasnake S, Nguyen PL, et al. Increased Access to and Use of Endovascular Therapy Following Implementation of a 2-Tiered Regional Stroke System. Stroke. 2020;51:908–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen M, Pearn K, James M, Ford GA, White P, Rudd AG, McMeekin P, Stein K. Maximising access to thrombectomy services for stroke in England: A modelling study. Eur Stroke J. 2019;4:39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venema E, Burke JF, Roozenbeek B, Nelson J, Lingsma HF, Dippel DWJ, Kent DM. Prehospital Triage Strategies for the Transportation of Suspected Stroke Patients in the United States. Stroke. 2020;51:3310–3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rinaldo L, Rabinstein AA, Cloft H, Knudsen JM, Castilla LR, Brinjikji W. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Utilization of Thrombectomy for Acute Stroke. Stroke. 2019;50:2428–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah S, Xian Y, Sheng S, Zachrison KS, Saver JL, Sheth KN, Fonarow GC, Schwamm LH, Smith EE. Use, Temporal Trends, and Outcomes of Endovascular Therapy After Interhospital Transfer in the United States. Circulation. 2019;139:1568–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saber H, Navi BB, Grotta JC, Kamel H, Bambhroliya A, Vahidy FS, Chen PR, Blackburn S, Savitz SI, McCullough L, et al. Real-World Treatment Trends in Endovascular Stroke Therapy. Stroke. 2019;50:683–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis SM, Campbell BCV, Donnan GA. Endovascular thrombectomy and stroke physicians: equity, access, and standards. Stroke. 2017;48:2042–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grotta JC, Lyden P, Brott T. Rethinking training and distribution of vascular neurology interventionists in the era of thrombectomy. Stroke. 2017;48:2313–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopkins LN, Holmes DR, Jr. Public health urgency created by the success of mechanical thrombectomy studies in stroke. Circulation. 2017;135:1188–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussain S, Fiorella D, Mocco J, Arthur A, Linfante I, Zipfel G, Woo H, Frei D, Nogueira R, Albuquerque FC. In defense of our patients. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9:525–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei D, Oxley TJ, Nistal DA, Mascitelli JR, Wilson N, Stein L, Liang J, Turkheimer LM, Morey JR, Schwegel C, et al. Mobile Interventional Stroke Teams Lead to Faster Treatment Times for Thrombectomy in Large Vessel Occlusion. Stroke. 2017;48:3295–3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panesar SS, Volpi JJ, Lumsden A, Desai V, Kleiman NS, Sample TL, Elkins E, Britz GW. Telerobotic stroke intervention: a novel solution to the care dissemination dilemma. J Neurosurg 2019;132:971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazya MV, Berglund A, Ahmed N, von Euler M, Holmin S, Laska AC, Mathe JM, Sjostrand C, Eriksson EE. Implementation of a Prehospital Stroke Triage System Using Symptom Severity and Teleconsultation in the Stockholm Stroke Triage Study. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:691–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.