Abstract

Approximately half of melanoma tumors lack a “druggable” target and are unresponsive to current targeted therapeutics. One proposed approach for treating these therapeutically-orphaned tumors is by targeting transcriptional dependencies (“oncogene starvation”), whereby survival factors are depleted through inhibition of transcriptional regulators. A drug screen identified a cyclin-dependent kinase 9(CDK9) inhibitor (SNS-032) to have therapeutic selectivity against BRAFwt/NRASwt melanomas compared to BRAFmut/NRASmut melanomas. We then used two strategies to inhibit CDK9 in vitro- a CDK9 degrader (TS-032) and a selective CDK9 kinase inhibitor (NVP-2). At 500 nM, both TS-032 and NVP-2 demonstrated greater suppression of BRAFwt/NRASwt/NF1wt cutaneous and uveal melanomas (BNFwt) than mutant melanomas (BNFmut). RNAseq analysis of 8 melanoma lines with NVP-2 treatment demonstrated that the context of this vulnerability appears to converge on a cell cycle network which includes many transcriptional regulators such as the E2F family members. Human TCGA melanoma tumor data further supported a potential oncogenic role for E2F1/E2F2 in BRAFwt/NRASwt/NF1wt tumors and a direct link to CDK9. Our results suggest that transcriptional blockade through selective targeting of CDK9 is an effective method of suppressing therapeutically-orphaned BRAF/NRAS/NF1 wild-type melanomas.

INTRODUCTION

Extraordinary progress has been made along therapeutic fronts for advanced melanoma. Small molecule inhibitors of oncogenic signaling(Chapman et al., 2011, Flaherty et al., 2012, Sosman et al., 2012) and humanized antibodies against immune checkpoint constituents(Brahmer et al., 2010, Brahmer et al., 2012, Topalian et al., 2012, Topalian et al., 2014) have both been shown to prolong survival. Even so, the long-term control achieved with these agents is far from universal. For tumors that harbor a BRAFV600E mutation, the dabrafenib+trametinib combination confers 5-year 13% progression-free and 28% overall survival rates among patients with advanced melanoma(Long et al., 2018). For checkpoint inhibitors, overall survival at 5 years still hovers around 50% even with the most effective nivolumab+ipilimumab combination(Wolchok et al., 2017). Thus, newer approaches are urgently needed for patients who are still innately resistant to these treatments.

Deep dissections of the melanoma genome have revealed that reciprocal BRAF and NRAS mutations occur in approximately 50% and 20–30% of melanomas, respectively (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga). The NF1 gene is also inactivated in about 10–15% of melanomas but not in exclusion to BRAF and NRAS alterations. There is thus a balance of about 20% of tumors which lack oncogenic variants in BRAF or NRAS but are driven by less common activating mutations in GNAQ, GNA11, KIT or other undiscovered oncogenes. These tumors have markedly fewer mutations than BRAF, NRAS, and NF1-mutant melanomas which correlates with far lower likelihood of responding to checkpoint inhibitors. We hypothesized that there may be targets or biological pathways that are differentially utilized by BRAFwt/NRASwt cells which provide to our knowledge previously unreported points of vulnerability for these treatment-resistant subgroups and thus set out to identify agents which may selectively target BRAFwt/NRASwt melanomas.

RESULTS

CDK9 abrogation preferentially inhibits BRAFwt/NRASwt melanomas

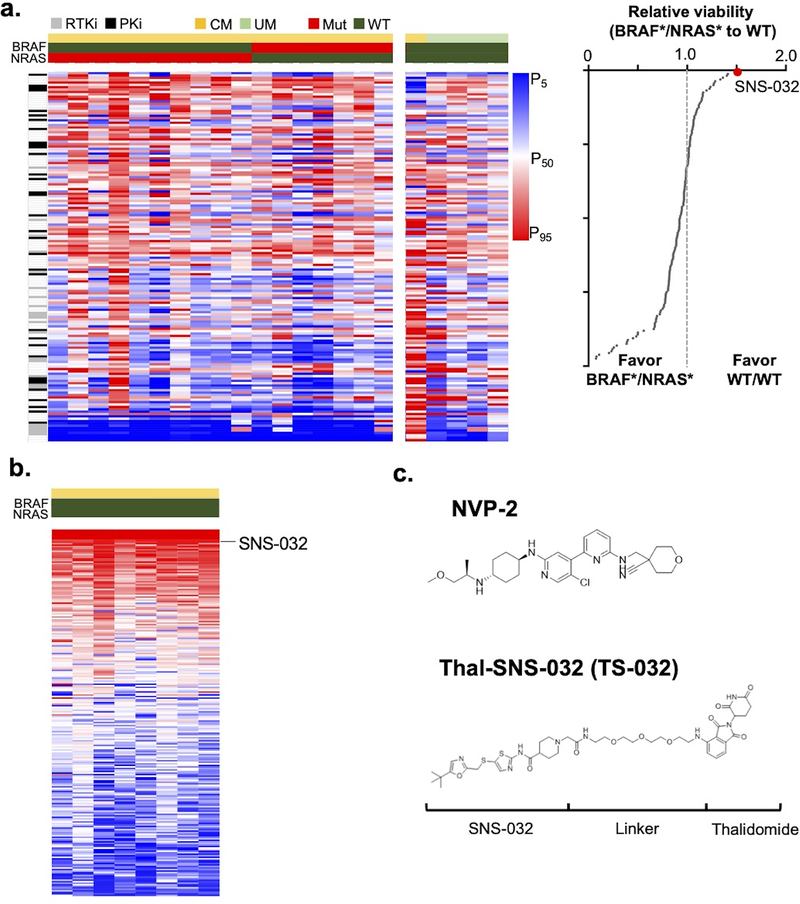

To discover drugs which preferentially inhibit BRAFwt/NRASwt melanoma cells, we performed a comparative genotype drug screen(CGDS). Seven BRAFV600E-mutated lines(BRAFmut), 11 NRAS-mutated lines (NRASmut;10 NRASQ61R and 1 NRASG12V mutations) and 5 BRAFwt/NRASwt (4 uveal and 1 cutaneous melanoma line) lines were tested against a panel of 158 targeted agents (Fig 1a, upper panel) at a single dose point of 10 μM (Table S1) in the CGDS. Overall, the CDK9 inhibitor, SNS-032, showed the greatest selectivity for BRAFwt/NRASwt lines (Fig 1a, lower panel). In an effort to replicate these findings, we interrogated a published drug screen of 240 drugs(Verduzco et al., 2018) against 8 BRAFwt/NRASwt lines. SNS-032 ranked 15th out of the 240 agents in terms of in vitro response (Fig 1b). These pilot results suggested that BRAFwt/NRASwt melanoma lines may be selectively vulnerable to CDK9 inhibition.

Figure 1: Comparative Genotype Drug Screen.

(a) Left panel, heatmap of viability for 23 melanoma lines (7 BRAF(V600E)-mutated lines, 11 NRAS-mutated lines (10 NRAS(Q61) and 1 NRAS(G12V) mutations), and 5 BRAFwt/NRASwt (4 uveal and 1 cutaneous melanoma line) screened against 158 Target Agents (10 μM; Table S1); Right panel, ratio of BRAF*/NRAS* lines to double WT lines. (b) Heat map of drug screen response in BRAFwt/NRASwt lines from Zhang et al. designating position of SNS-032. (c) Structures of a competitive CDK9 inhibitor (NVP-2) and the CDK9 degrader (TS-032). BRAF*, BRAF(V600E) mutated; NRAS*, NRAS mutated.

As SNS-032 is not completely selective for CDK9 and has documented activity against CDK2 and CDK7(Heath et al., 2008), we advanced our studies using two selective CDK9 inhibitors with complementary mechanisms of action - a CDK9 degrader based on SNS-032(Thal-SNS-032, TS-032) and a potent ATP-competitive CDK9 inhibitor, NVP-2(IC50 = 0.5 nM), which shows selectivity for CDK9 over a panel of 468 kinases (Fig 1c)(Olson et al., 2018).

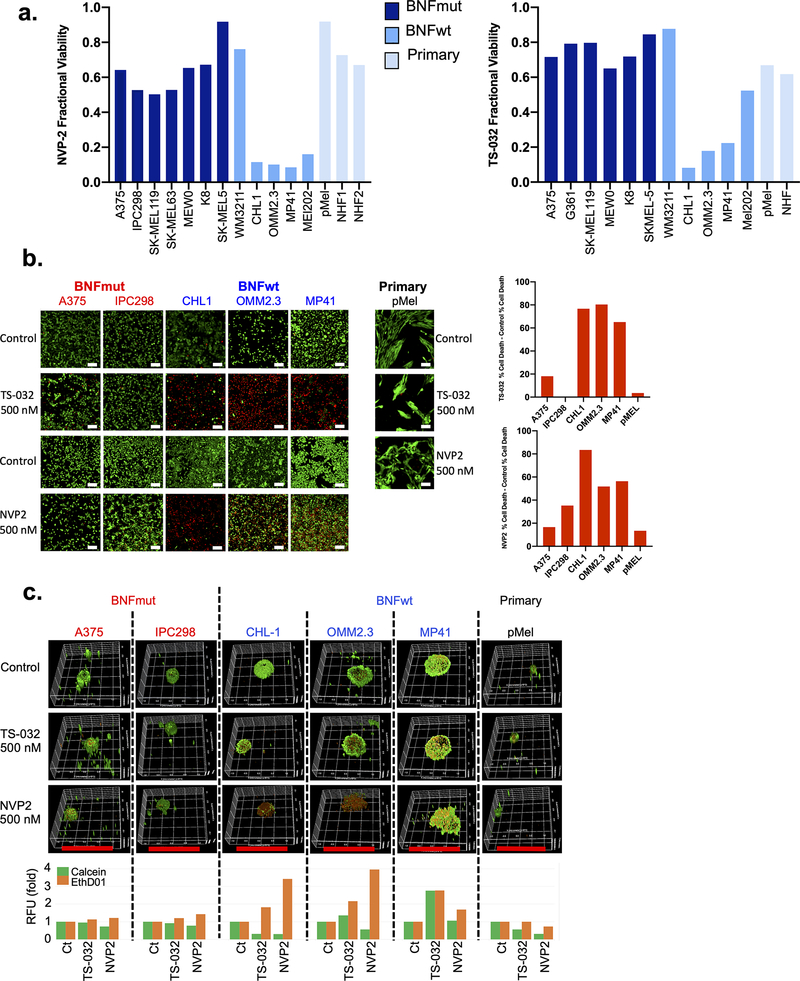

We performed viability studies using both TS-032(500 nM) and NVP-2(500 nM; Fig 2a) on a collection of melanoma lines, an immortalized non-transformed melanocyte line(pMel), and normal human fibroblasts (NHF). BRAFwt/NRASwt/NF1wt (BNFwt) lines included cutaneous melanoma lines (CHL1 and WM3211) and uveal melanoma lines (OMM2.3, MP41, MEL202). BRAFmut/NRASmut/NF1mut (BNFmut) lines included A375, IPC298, SK-MEL119, SK-MEL63, MEWO, K8, and SK-MEL5. For both agents, the BNFwt lines were apparently more sensitive than either the BNFmut or primary cell lines with the exception of WM3211, which is known to harbor a KITL576P mutation. In the case of NVP-2, the median fraction viabilities (MFVs) were 0.64, 0.12, and 0.73 for the BNFmut, BNFwt, and primary lines, respectively, while for TS-032, the MFVs were 0.76, 0.22, and 0.64 for the 3 groups, respectively. Comparison between the BNFwt vs BNFmut melanoma groups reveals consistent trends towards increased sensitivity among the BNFwt cells (MFVNVP-2: 0.64 vs 0.12, p=0.073 and MFVTS-032: 0.76 vs 0.22, p=0.13, both Mann-Whitney test).

Figure 2: CDK9 Suppression Preferentially Targets Triple WT Melanomas.

(a) Cell viability of BNFmut (dark blue bars), BNFwt (medium blue bars), and primary cells (light blue bars; immortalized melanocytes, pMEL or normal human fibroblasts, NHF) after 24 hours of treatment with 500 nm TS-032 (left panel) or NVP-2 (right panel). Live(green)/dead (red) imaging and quantification of melanoma lines after 24 hours of 500 nm TS-032 and NVP-2 treatment in (b) 2D cultures (scale bar = 100 micrometers) or (c) 3D spheroid cultures (scare bar = 2 millimeters or 2000 micrometers). BNFwt, BRAF/NRAS/NF1 wildtype; BNFmut, BRAF/NRAS/NF1 mutated.

To determine the cellular response, we performed live/dead assays on 2D and 3D spheroid cultures. For BNFmut lines, there appeared to be some cytostasis on 2D plate cultures for both TS-032 and NVP-2 (Fig 2b), which is consistent with the 20–40% lower cell numbers observed in Figure 2a. Despite the reduction in cell numbers, there was only minimal background cell death(red cells, Fig 2b). In contrast, there was a dramatic increase in the number of dead cells among the BNFwt cells with both agents (Fig 2b). Cell cycle profiling of 5 cell lines (Fig S1, three BNFmut and two BNFwt lines) at 8 hrs showed significant increases in G1 in BNFwt lines with both TS-032 and NVP-2 but only a slight increase in G2/M in 1 of 3 BNFmut lines (A375). No significant pattern was observed

The cell death from treatment was even more notable in 3D spheroids at 24 hrs. The BNFwt lines exhibited massive cell death through the entire cell sphere while the BNFmut cells only harbored a few dead cells predominantly at the core (Fig 2c). The immortalized melanocyte cells (pMel) exhibited a relative absence of detectable cell death. Taken together, these cellular studies confirm the preferential sensitivity and increased cell death of BNFwt cells to CDK9 suppression compared to BNFmut cells, as identified in the initial drug screen.

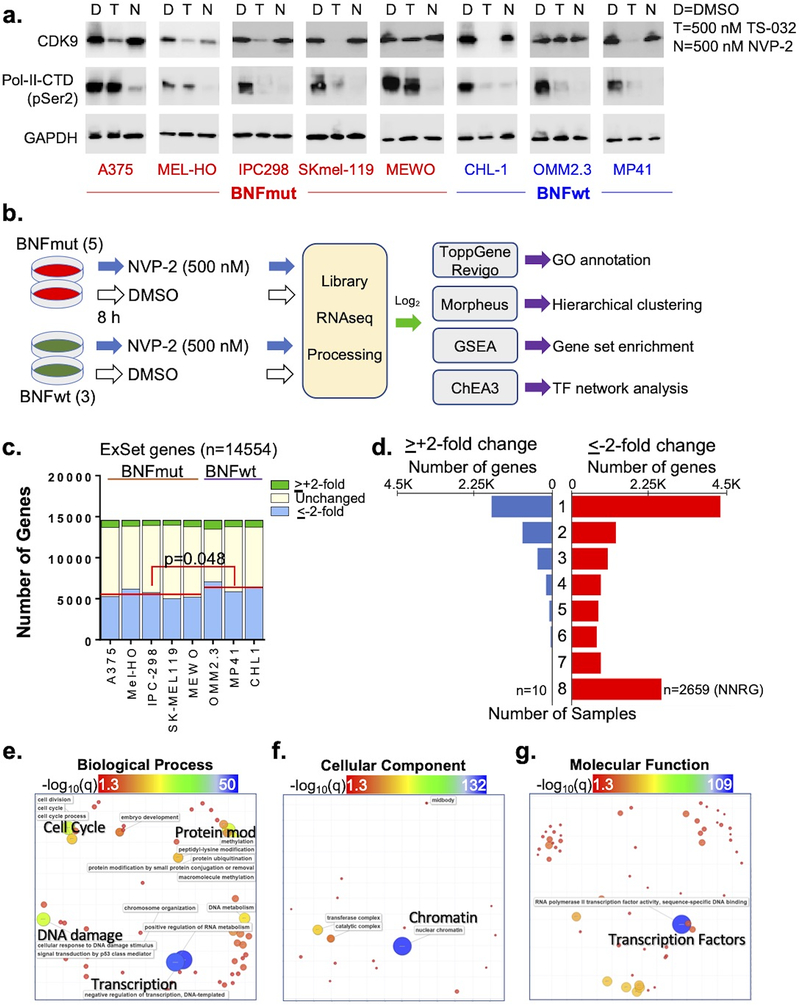

BNFwt melanomas are more susceptible to cell cycle “exhaustion”

We next sought to uncover possible mechanisms that could explain this selective targeting. In order to enrich for primary transcripts and network changes induced by these agents, we selected an early 8-hour time point to minimize later effects observed from secondary reprogramming. To first ensure appropriate intracellular targeting, we treated five BNFmut lines (A375:BRAFV600E, Mel-HO:BRAFV600E, SK-MEL-119:NRASQ61R, IPC-298:NRASQ61L and MeWO:NF1Q1336X) and three BNFwt lines(CHL-1, OMM2.3:GNAQQ209L, MP41:GNA11Q209L) with 500 nM TS-032 or 500 nM NVP-2. Western blotting demonstrated successful ablation of CDK9 by TS-032, but not NVP-2, within 8 hours. Interestingly, NVP-2 exposure led to more consistent abrogation of pSer-2-CTD (Fig 3a, S2), a known target of CDK9, than TS-032, which exhibited more variable effects. The mechanism(s) explaining the uneven effects of TS-032 remain unknown and may be explained by cell-to-cell variability in CDK9 degradation rate, enzymatic activity, and amount of CDK9 protein needed to harbor sufficient pSer-2-CTD phosphorylation. Since NVP-2 showed a more consistent biochemical effect at the 8-hr time-point, we decided to employ NVP-2 for the molecular analysis.

Figure 3. Identification of common NVP-2 response pathways.

(a) Western blots showing CDK9, RNA-Pol-II CTD-Ser phosphorylation and GAPDH 8 hrs after exposure to DMSO (D), 500 nMTS-032 (T) and 500 nM NVP-2. (b) Schematic of workflow for molecular analysis. (c) Changes in gene expression across 8 cell lines. Red line shown shows average number of genes that decreased by ≤−2x in BNFmut vs BNFwt lines. (d) Number of upregulated (blue, >+2x) or downregulated (red, <−2x) genes that are shared by 1–8 samples. GO annotations for 2659 NNRGs as computed by ToppGene and semantically trimmed by Revigo for Biological Processes (e), Cellular Component (f) and Molecular Function (g). Heatmap and size of circles are proportional to –log(q) of association. NNRG, NVP-2 negative response gene.

Using RNAseq, we examined changes in response to NVP-2 in the 5 BNFmut lines and 3 BNFwt lines(Fig 3b). Unsupervised clustering of all 16 samples showed that there were two large branches defined by DMSO control and NVP-2(Fig S3). Figure 3b diagrams the experimental flow and Figure 3c shows the unfiltered and filtered dynamic profiles of each cell line. For filtering, we excluded genes which were expressed in less than half the samples thereby leaving 14554 in the “expression set”(ExSet, Table S2).

A priori, CDK9 inhibition leads to transcriptional pause which triggers a stochastic loss of RNA species that vary from line to line. Alternatively, there may also be a more coordinated attrition if there is a shared set of strong transcriptional dependencies or labile mRNA transcripts. We thus sought to determine if there is a coordinated NVP-2 response across all 8 cell lines. While there were only 10 genes which increased ≥2-fold, 2659 genes decreased ≥2-fold in all the lines thereby defining a set of NVP-2 negative response genes (Fig 3d; NNRGs). Gene Ontology(GO) analysis and semantic trimming of these 2659 NNRGs revealed biologically-linked GO “clusters”(Table S3). The most significant GO Biological Process (GO-BioP) terms (FDR<0.05) condensed around RNA metabolism, transcription, protein modification, cell cycle and DNA damage/p53(Fig 3e) while NUCLEAR CHROMATIN (FDR=2.82E-133) was the single most dominant GO Cellular Component term (Fig 3f). In terms of GO Molecular Functions (Fig 3g), there was a highly significant enrichment for transcription factors (TFs, DNA-BINDING TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR ACTIVITY, RNA POLYMERASE II-SPECIFIC(FDR=4.29E-110) with 556 of the 1614 ToppGene TFs in the database (34.4%) represented in the NNRG (Table S3; χ2 =554.94; p<0.00001). Of note, these included “master” lineage oncogenes, MITF (avg(log2)FC: −2.92) and SOX10 (avg(log2)FC: −3.83) along with 305 of the 581 “ZNF”-related zinc-finger TFs. The top pathways(Fig S4) identified were TRANSCRIPTION (FDR=1.50E-72) and GENE EXPRESSION (FDR=8.28E-64). These results indicate that CDK9 inhibition leads to the rapid depletion of a core set of genes (i.e. NNRG) which is significantly enriched for transcription factors.

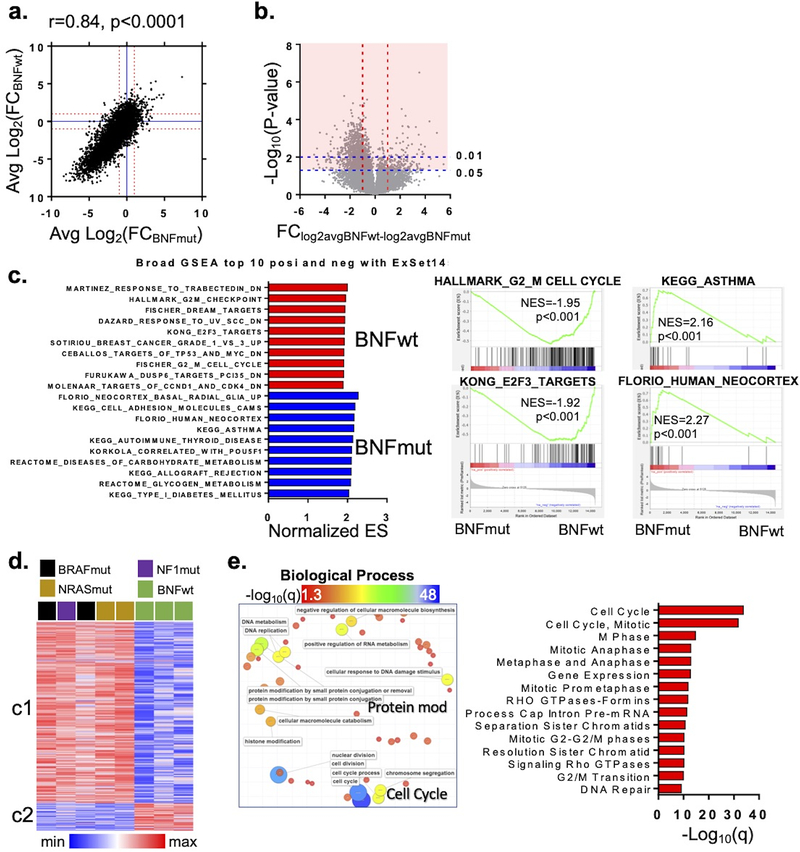

Next, we set out to better understand the preferential sensitivity of BNFwt lines to NVP-2. Overall, there was a strong correlation between average log2-fold changes(NVP-2–DMSO; Table S2) among BNFmut and BNFwt cells (Fig 4a, r=0.84, p<0.0001) which is consistent with the large number of shared NNRGs. To tease out differences between BNFmut and BNFwt, we subjected a pre-ranked “ΔΔ” list (avg Log2FC(NVP-DMSO)BNFwt- AvgLog2FC(NVP-DMSO)BNFmut) of the 14554 ExSet genes to gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA; Fig 4c; Table S4). The top gene sets associated with NVP-2 sensitivity(BNFwt) included multiple cell cycle elements such as FISCHER_G2_M_CELL CYCLE (NES=−1.91, q= 0.012) and HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT(NES=−1.95, q= 0.012). The highest-ranking transcription factor target gene set belonged to a member of the E2F family (i.e. E2F3; KONG_E2F3_TARGETS, NES: −1.92, q=0.012).

Figure 4. Distinct molecular pathways distinguish BNFwt from BNFmut lines.

(a) Scatterplot of log2FC’s for NVP-2-DMSO in BNFwt vs BNFmut cell lines. (b) Volcano plot of average Log2 fold changes ((avg log2 BNFwt) - (avg log2 BNFmut)) and –log10(p value). Red shading highlights n=2029 genes whose response to NVP-2 were significantly (p<0.05) different between BNFmut and BNFwt cells (c) Left panel, gene set enrichment analysis of all 14554 ExSet genes pre-ranked log2FC(NVP-DMSO) for BNFwt and BNFmut; right panel, representative graphs. (d) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of 2029 genes into BNFmut vs BNFwt branches and c1 vs c2 clusters. c1 cluster genes strongly mapped to cell cycle (e) GO terms and (f) pathways.

To further refine the pathways of NVP-2 vulnerability, we identified genes with the most significant differential response to NVP-2. Among the ExSet, there were 2029 genes whose average change due to the drug was significantly different(Fig 4b- red shaded region; Table S3) between the 5 BNFmut and 3 BNFwt lines. Unsupervised clustering using log2(NVP-2-DMSO) levels for these 2029 genes effectively partitioned the sample space into BNFmut and BNFwt arms and 2 ostensible clusters (Fig 4d; Table S5). Cluster 1 (c1) encompassed genes which were more significantly depleted in the BNFwt lines compared to BNFmut lines and cluster 2 (c2) represented the inverse. Meta-analysis of elements in c1 (Fig 4e, Table S5) mapped to multiple “cell cycle”-related GO terms in both Biological Processes (CELL CYCLE, q=6.327E-49) and Reactome Pathways (Fig S5; CELL CYCLE, q=1.708E-34). There were no significant pathways associated with c2. This indicates that there is significantly greater depletion of cell cycle components in the BNFwt lines compared to the BNFmut thereby raising the possibility that some form of “cell cycle exhaustion” might play a role during CDK9 inhibition.

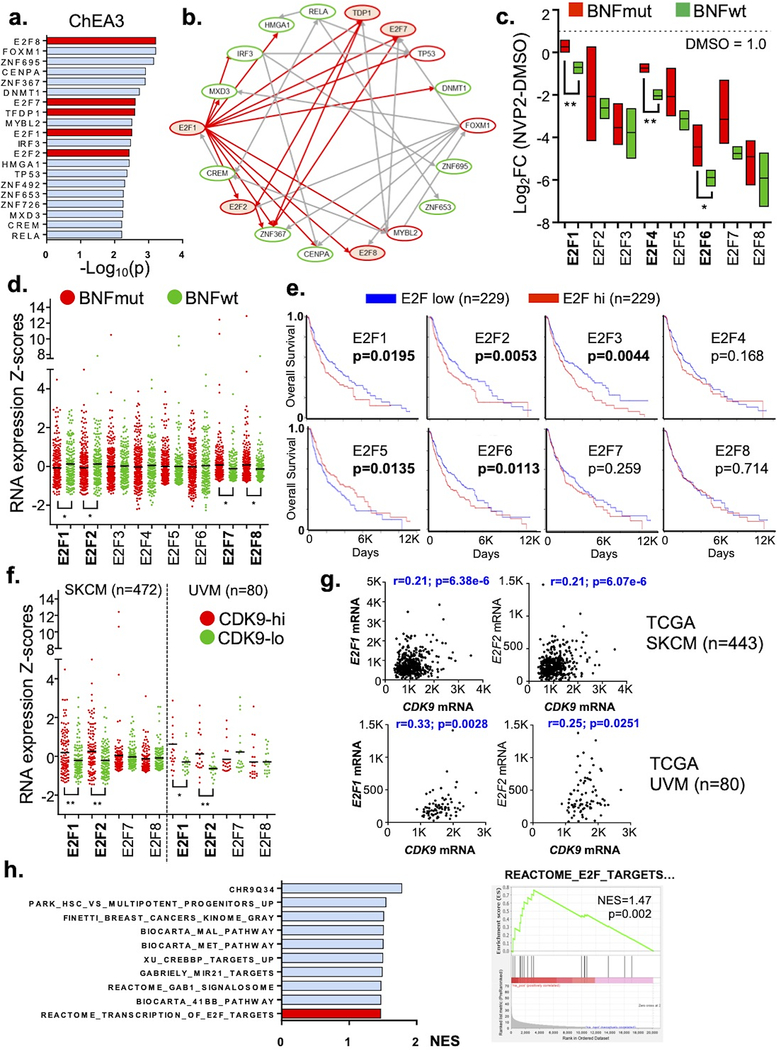

To uncover latent transcriptional networks which may explain the preferential vulnerability of BNFwt cells to NVP-2, we subjected the c1 genes to TF target enrichment and network analyses with ChEA3. The top TF target association was E2F8 (Fig 5a; p=6.14E-04; Table S6) though there were other E2F family members (E2F1,p=0.0033; E2F2,p=0.0037; E2F7,p=0.0025;TFDP1,p=0.0025) ranking among the top 20. Other transcriptional footprints included known cell cycle regulators such as TP53 (p=0.0043), MYBL2 (p=0.0031) and FOXM1 (p=6.22E-04). With the top 20 TFs, the c1 “interactome” converged on E2F1 as 12 of 18 of the mapped TFs (Fig 5b) are ChIP-seq-verified targets of E2F1. We also used the ToppGene transcription factor algorithm and found E2F1 (Table S5; p=4.31E-04) and E2F4 (p= 1.37E-05) to be significantly associated with the c1 cluster. Lastly, if the E2F network is more depressed by NVP-2 in BNFwt cells compared to BNFmut ones, we would also expect that the E2F levels would be more greatly suppressed by the drug in the BNFwt cells. As shown in Figure 5c, all eight E2F factors exhibited greater decrements in the BNFwt than BNFmut lines with E2F1, E2F4 and E2F6 showing significant differences. These results suggest that BNFwt cells may be more selectively dependent on a E2F transcriptional network than BNFmut cells.

Figure 5. Transcriptional Networks Associated with BNFwt cells.

(a) ChEA3 analysis of top ranking DNA binding proteins using 2029 cluster 1 (c1) genes. E2F family members highlighted in red. (b) TF interactome of top 20 DNA binding proteins. Red ovals indicate known cell cycle regulators; Arrows indicate evidence of TF binding at target as determined by ChIP-seq data, red arrows indicate known E2F TF targets. (c) Decrease in E2F transcription factors with NVP-2 among BNFmut and BNFwt cell lines. (d) Normalized RNA expression levels from TCGA SKCM cohort as stratified by BNFmut vs BNFwt samples. BNFmut tumors were defined as BRAF(V600E) + NRAS(G12–13, Q61) + all NF1 mutations. BNFwt tumors are all other samples. (e) Overall survival as determined by EF2-hi vs EF2-low samples (cut at median expression). (f) Normalized RNA expression in TCGA SKCM and UVM specimens as stratified by CDK9-hi vs CDK9-low samples (cut at 25th percentile (low) and 75th percentile (hi)). (g) Correlation between CDK9 and E2F1 and E2F2 in SKCM and UVM samples. (h) GSEA of pre-ranked TCGA SKCM samples (from most highly correlated to least). * p<0.05; ** p<0.01

To establish human tumor relevance, we conjectured that levels of E2F TF members may be differentially expressed between BNFmut and BNFwt specimens. We first examined the expression levels of all E2F members among 472 TCGA SKCM BNFmut (i.e. BRAFV600E, NRASQ61/G12/13, NF1deleterious) and BNFwt SKCM tumors (Table S7). As shown in Figure 5d, BNFwt melanomas had significantly higher expression levels of E2F1 and E2F2, which are known to be “transcriptional activators”, while having significantly lower expression of “transcriptional repressors” E2F7 and E2F8 (Attwooll et al., 2004). These results are consistent with a greater dependency on E2F1 and E2F2 for the BNFwt cells. Of note, these 4 differentially expressed E2F transcription factors (E2F1, E2F2, E2F7 and E2F8) were also the ones identified in our NVP-2 network analysis (Fig 5a). The pattern of elevated E2F1/E2F2 and depressed E2F7/E2F8 expression in BNFwt compared to BNFmut cell lines was also confirmed in our RNAseq analysis, although the differences did not reach significance. Second, among the SKCM cohort(Fig 5e), higher expression of E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, and E2F6 and lower expression of E2F5 were all significantly associated with worsened survival indicating that E2F family members may underpin a more aggressive oncogenic network. Third, if CDK9 suppression leads to an extinction of an E2F-based network, then the levels of E2F1, E2F2, E2F7 and E2F8 may be related to the levels of CDK9 in human specimens. We stratified the TCGA SKCM (n=472) and UVM (n=80) samples into CDK9-hi (75th percentile expression) and CDK9-lo (25th percentile expression) tumors and examined levels of E2F network genes (E2F1, E2F2, E2F7 and E2F8;Fig 5f;Table S8). In both melanoma tumor sets, CDK9-hi melanomas had significantly higher levels of E2F1 and E2F2 compared to CDK9-lo melanomas. Across all specimens, levels of both E2F1 and E2F2 were significantly correlated with CDK9 in both SKCM and UVM cohorts (Fig 5g). We also performed CDK9 co-expression analysis across all specimens in the TCGA SKCM and subjected a pre-ranked correlation list (by q-value) to GSEA (Table S9). As shown in Figure 5h, among the pathways most correlated with CDK9 levels among the SKCM samples, a Reactome E2F transcription target gene set ranked among the top 10 (p=0.002). These human tumor studies indicate that the E2F network may be differentially supervised by BNF status, associated with a worsened outcome, correlate with intracellular CDK9 levels and may thus contribute, in part, to the observed difference in response to NVP-2.

DISCUSSION

In the realm of molecular therapies, only BRAF(V600)-mutated tumors have enjoyed sustained benefit with targeted agents(Robert et al., 2019). While receptor tyrosine kinase(RTK) inhibitors have been used against KIT-driven tumors, clinical trial experience documents only moderate successes as progression-free survival is usually less than 6 months(Meng and Carvajal, 2019). Numerous studies in melanoma have implicated additional functionally validated oncogenes that have traditionally been considered “undruggable” because of enzymatic or structural privileges. Previous studies have shown that cancer cells can become “addicted” to high-level production of survival or proliferation genes(Eliades et al., 2018, Loven et al., 2013, Rusan et al., 2018). Thus, in the absence of a well-defined molecular target, one potential strategy is to pharmacologically deplete these oncogenic factors by interrupting their transcription rather than direct inhibition of their enzymatic function(i.e. “oncogene starvation”).

Among the array of transcriptional components, the CDK family of serine/threonine kinases are critical regulators of both cell cycle progression and gene transcription. CDK1, 2, 4, and 6 are canonical cell cycle CDKs, and CDK7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 19 are transcription-regulating CDKs(Bartkowiak et al., 2010, Malumbres and Barbacid, 2005). For cells that are reliant on high-level oncogene production, CDK9 has emerged as an attractive target(Sonawane et al., 2016, Wu et al., 2012, Xie et al., 2014). CDK9 forms a complex with T-and K cyclins and phosphorylates the Pol-II CTD domain at Ser2(Sonawane et al., 2016) thereby priming Pol-II for transcriptional elongation(Fisher, 2012). As a proof-of-concept, we recently showed that transcription attenuation with a covalent CDK7 inhibitor led to broad toxicity against all genotypic classes of melanoma(Eliades et al., 2018). From a therapeutic perspective, effective CTD kinase inhibition, such as CDK7/9 suppression, represents a transcriptional “off” switch and a possible means of oncogene deprivation.

Since the transcriptional apparatus is universal, it was surprising to uncover genotype selectivity with SNS-032, a competitive CDK9 inhibitor. While SNS-032 has been reported to be effective against cutaneous(Verduzco et al., 2018) and uveal(Zhang et al., 2019) melanoma lines both in vitro and in animals, no CDK9 inhibitor so far has been FDA-approved for clinical use(Whittaker et al., 2017). One limitation of these first generation CDK9 inhibitors is their lack of specificity. We attempted to overcome this barrier by using a highly selective ATP competitive inhibitor, NVP-2, and a thalidomide-based degrader, TS-032, to functionally probe the phenotypic and molecular effects of CDK9 suppression. TS-032 is entirely dependent on the CRBN and proteasome pathway, and selectively degrades CDK9 with over 100-fold greater ablation than other CDKs(Olson et al., 2018). With these two agents, this is the first report, to the best of our knowledge, of a targeting strategy that differentiates between the more prevalent genotypic classes(i.e. BNFmut) from the rarer and heterogeneous BNFwt group. Our results indicate that CDK9 depletion potently and preferentially reduced cell viability of BNFwt melanoma cells in vitro, and induced cell death in 2D/3D cell models. While the precise mechanism by which this genotypic selectivity is conferred is still a matter of investigation, our study did uncover several intriguing findings.

The recovery of a relatively large set of shared NVP-2 depleted genes(n=2659) suggests that early transcript decay from CDK9 suppression is somewhat coherent and appears to favor transcription factors. Among the genes in the coordinated NVP-2 response, “master” lineage oncogenes MITF and SOX10 are consistently downregulated which could contribute to melanoma growth inhibition and death. The molecular context of BNFwt vulnerability to NVP-2 appears to converge on a differential cell cycle response perhaps controlled by a network of TFs (Fig 5b) anchored by E2F transcription factors. Our findings that the E2F network is more profoundly diminished by NVP-2 in BNFwt cells compared to BNFmut cells and that E2F1 and E2F2 levels are significantly higher in BNFwt and CDK9-hi tumors suggest that the transcriptional motor to fuel E2F production may be greater in BNFwt melanomas. An oncogenic role is further supported by the association of high E2F expression with worsened melanoma survival in the SKCM cohort (Fig 5d). These results raise the possibility that BNFwt cells are more dependent on high-level production of these oncogenic transcription factors such as E2F1 and E2F2 for survival and are thus more vulnerable to “cell cycle exhaustion” upon CDK9 inhibition.

The E2F family of transcription factors have been extensively studied in cancer and exhibit paradoxical features of tumor suppressors and oncogenes(Kent and Leone, 2019). Several groups have characterized E2F1 as an oncogene in melanoma as E2F1 is highly expressed in many lines and suppression of E2F1 leads to decreased invasiveness, growth inhibition, or cell death(Alla et al., 2010, Meng et al., 2019, Rouaud et al., 2018). E2F members have been studied as possible therapeutic targets for melanoma in the past(Alla et al., 2010, Kent and Leone, 2019, Meng et al., 2019, Rouaud et al., 2018).

The first limitation of our study is the small sample size of BNFwt tumors. Within the TCGA cutaneous melanoma cohort, BNFwt tumors are mutationally heterogeneous, with oncogenic alterations in KIT(7%), GNAQ(<5%) and GNA11(<5%). Our study included only small representation of this tumor class. Second, our RNAseq experiment demonstrated the differential consequences of NVP-2 inhibition and not the mechanism(s) of action. Furthermore, this experiment, albeit coordinated across 8 cell lines, was limited by a single time point and dose point. We intentionally chose an earlier 8-hour post-exposure point to maximize capture of early transcriptional effects rather than delayed secondary effects. Fourth, while we have substantially characterized both NVP-2 and TS-032 in 3D spheroid models, we do not present animal data. Both agents represent newer generations of CDK9 inhibitors and thus lack large scale experience in vivo. SNS-032 has already been shown to suppress the growth of xenografted MP41- a uveal melanoma line(Zhang et al., 2019). However, comparative pharmacophenotyping of distinct BNFmut and BNFwt lines in vivo using genetically disparate cells that exhibit variable tumorigenic trajectories remains an ongoing effort. Finally, due to the small number of in vivo analyses, this study is also limited by a lack of toxicity and safety profiles of TS-032 and NVP-2.

In summary, our observations show that CDK9 inhibition preferentially devitalizes BNFwt cells compared to BNFmut cells. The context of this vulnerability appears to converge on a cell cycle network which includes many transcriptional regulators such as the E2F family members. Human TCGA melanoma tumor data further support a potential oncogenic role for E2F1/E2F2 in BNFwt tumors and a direct link to CDK9. These studies further support the concept of oncogene starvation in cancers without readily druggable targets, such as triple wild-type melanomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

See supplementary files for full methods.

Reagents and Cell Lines

TS- 032 and NVP-2 were synthesized and provided by the Nathanael Gray Laboratory (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). BNFmut lines included A375BRAF-V600E, Mel-HOBRAF-V600E, SK-MEL-5BRAF-V600E/CDKN2Adeletion, SK-MEL-119NRAS-Q61R, IPC-298NRAS-Q61L, SK-MEL-63NRAS-Q61R, K8NF1-R681*, MeWONF1-Q1336X. BNFwt lines included CHL-1, WM3211KIT-L576P, OMM2.3GNAQ-Q209L, MP41GNA11-Q209L, and MEL202GNAQ-Q209L.

Small molecule screening

Small molecule library of 153 inhibitors was obtained from Selleck Chemicals(Houston, TX). Compounds were diluted to 10 micromole/liter. Cell viability was measured using alamar blue assay 72 hours later.

Cell Viability and Live/Dead Studies

Cells were exposed to 24 hours of 500 nm of TS-032 and 500 nm NVP-2. CellTiter-Glo(Promega, Madison, WI) was used to measure cell viability. Live/Dead assay was conducted using standard protocol(cat no.MP-03224; Life Technologies™). 2D Live/Dead were imaged via confocal imaging and 3D were imaged via Operetta high content imaging system. Quantification is outlined in Full Materials and Methods.

Western Blots

Cell lines were exposed to 8 hours of 500 nm of TS-032 and NVP-2. Probing antibodies included: rabbit antibodies against CDK9(Cell Signaling cat. no. 2316), rat antibodies against pSer-2-CTD(Millipore cat. no. 04–1571), and mouse antibodies against GAPDH as a loading control(cat. no. ab8245; Abcam). See supplemental methods for full details.

RNASeq

Total cell RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent(Invitrogen; Thermo fisher Scientific, Inc.) and RNeasy Mini kit(Qiagen). RNA quality was examined by Qubit 3(Thermo fisher Scientific, Inc.) and Fragment Analysis(Whitehead Institute Genome Technology Core, MIT, Cambridge, MA). Total RNA was sent to BGIseq-500(Shenzhen, China) for library preparation, sequencing and analysis.

Bioinformatics

DATA AVAILABILITY

Datasets related to this article can be found at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/hknwy2nggg/1, hosted at Mendeley (Guhan, Samantha (2020), “The molecular context of vulnerability for CDK9 suppression in triple wild-type melanoma: Supplemental Datasets ”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/hknwy2nggg.1).

FULL MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

TS- 032 was invented, synthesized, and provided by the Nathanael Gray Laboratory (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). NVP-2 was synthesized and provided gratis by the Nathanael Gray Laboratory (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA).

Cell Lines and Culture

BNFmut lines included A375BRAF-V600E, Mel-HOBRAF-V600E, SK-MEL-5BRAF-V600E/CDKN2Adeletion, SK-MEL-119NRAS-Q61R, IPC-298NRAS-Q61L, SK-MEL-63 NRAS-Q61R, K8NF1-R681*, MeWONF1-Q1336X. BNFwt lines included CHL-1, WM3211KIT-L576P, OMM2.3GNAQ-Q209L, MP41GNA11-Q209L, and MEL202GNAQ-Q209L. STR genotyping was used to confirm the identity of A375, Mel-HO, SK-MEL-5, MeWO, CHL-1, WM3211 and IPC-298. SK-MEL-63 and SK-MEL-119 did not exist in the STR database but have genotypes consistent with those reported in the COSMIC database. OMM2.3 and MEL-202 were gifts from Dr. B. Ksander (Schepens) and have genotypes consistent with those published in the literature. K8 is a line derived from a patient with documented metastatic melanoma and has an MITF RNA Z score=+1.45 among 84 cell lines and is thus compatible with a melanoma. MP41 was purchased directly from the ATCC.

Immortalized melanocytes and melanoma cell lines were cultured using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA), 100 units/mL penicillin (Life Technologies) and 100 ug/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies). Uveal melanoma cell lines were cultured using Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) (Lonza, cat. no. 12–702f), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA), 1% HEPES (Lonza, cat. no.17–373E), 1% L-glutamine (Life Technologies), 0.1% 2-ME (Gibco-ThermoFisher Scientific), 100 units/mL penicillin (Life Technologies) and 100 ug/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies). Human fibroblast lines were cultured using Medium 106 (Life Technologies), supplemented with 100 units/mL penicillin (Life Technologies) and 100 ug/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies), and 1% low serum growth supplement (Life Technologies). BJ Fibroblasts were grown in ATCC-formulated Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (catalog no. 30–2003) and Fetal bovine serum to a final concentration of 10%. All cells were grown at 37C in incubators with 95% room air and 5% CO2.

Small molecule screening

A medium-throughput cellular assay was set up to identify melanoma inhibitory compounds. Small molecule library of 153 inhibitors with known intracellular targets was obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX). Compounds were diluted to 10 micromole per liter in 96 well plates, which were plated with melanoma cells at a density of 2000 per well in 100 microliter media. 72 hours later, cell viability was measured using alamar blue assay. Briefly, 10ul of Alamar blue cell viability reagent (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) was added to each well in 96 well plates. The plates were then incubated in 37-degree cell culture incubator for another 2 hours. Viable cells will then modify the reagent and increase fluorescence, which was then measured by a SpectroMax M5 spectrometer (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) using an excitation between 530 and an emission at 590 nm. Cell viability was determined by subtracting background reading from medium only wells. Relative cell viability was determined by dividing reading from treated well by reading from DMSO treated well.

2D Cell Viability Studies

Melanoma cell lines were plated in a white-walled 96 well plate. 3.0×103 cells were plated per well, with each treatment performed in triplicate. Cells were exposed to 24 hours of 500 nm of TS-032 and 500 nm NVP-2, beginning 24 hours after the cells were plated. CellTiter-Glo luminescence assay (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to measure cell viability. To summarize, 20 ul of reconstituted reagent was added to each well, and cells were incubated in the dark with gentle shaking for 15 minutes at room temperature. A Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA) Spectramax M5 or Spectramax Plus 384 plate reader was used to measure luminescence (total light emission) via the CellTiter-Glo protocol. DMSO- treated controls were used for normalization. Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad.

2D Live/Dead Studies

Melanoma cell lines were plated in a 12 well glass bottom plate. 1.0 X × 105 cells were plated per well, with each treatment performed in triplicate per cell line. Cells were exposed to 24 hours of 500 nm of TS-032 and 500 nm NVP-2, beginning 24 hours after the cells were plated. Live/Dead assay dyes were added from the assay kit (cat no. MP-03224; Life Technologies™), directions were followed using standard protocol, and were imaged via confocal imaging. Quantification of relative LIVE/DEAD imaging was conducted using Image J.

3D Live/Dead Studies

Live/Dead assays were repeated in a 3D model to evaluate the ability of TS-032 and NVP-2 to penetrate a tumor-shaped spheroid. Cells were plated per well to a 96-well plate (A375 cells, 1500 cells/well; IPC-298 cells, 2000 cells/well; MEWO cells, 1500 cells/well; CHL-1 cells, 750 cells/well; MP41 cells, 1,500 cells/well; OMM2.3 cells, 2000 cells/well, pMEL cells, 2000 cells/well) with each treatment performed in triplicate per cell line. After 24 hr of incubation, cells were chilled on ice for 5 minutes before chilled 50 ul Matrigel® was added to each plate. Cells were incubated for 3 days at 37°C before drug treatment (Control DMSO, 500 nm TS-032 and 500 nm NVP-2). The cells were incubated with 100 μL/well of Calcein AM Green/Ethidium homodimer-1 dye-working solution for 1 hr at 37 °C. The fluorescence intensity was measured at Ex/Em = 490/525 nm (Calcein) and 540/650(EthD-1) nm with bottom read mode using Operetta CLS™ (PerkinElmer). The fluorescence intensity ratio of live (490/525 nm) to dead (540/650 nm) cells were analyzed by Harmony 4.5 software, as indicated.

Western Blots

Cell lines were grown on 60 mm plates, and were exposed to 8 hours of 500 nm of TS-032 and 500 nm NVP-2, beginning 24 hours after the cells were plated. Protein extraction was conducted using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS; Boston Bioproducts). Protein quantification was determined via a Lowry assay, and sample concentrations were adjusted accordingly. Samples were run through a 4–12% SDS-PAGE gel before being transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Cells were incubated at room temperature for one hour with 5% non-fat milk in TBST, washed with TBST, and probed with rabbit antibodies against CDK9 (Cell Signaling cat. no. 2316), rat antibodies against pSer-2-CTD (Millipore cat. no. 04–1571), and mouse antibodies against GAPDH (cat. no. ab8245; Abcam). TBST was used to wash the blots which were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (cat. no. 7074s; Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-mouse antibodies (cat. no. 7076s; Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-rat IgG(Cell Signaling; cat.no. 04–1571). After another TBST wash, Clarity Western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad laboratories) was used for development.

RNASeq

Total cell RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo fisher Scientific, Inc.) and RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). RNA quality was examined by Qubit 3 (Thermo fisher Scientific, Inc.) and Fragment Analysis (Whitehead Institute Genome Technology Core, MIT, Cambridge, MA). For High-through-put library preparation, sequencing and analysis total RNA was sent to BGIseq-500 (Shenzhen, China).

Bioinformatics

Excel was used to calculate the averages and differences of raw FPKM data provided by BGIseq-500. The number of genes expressed in each sample, the genes expressed in at least 8 cell lines (ExSet 8), and a basic student t test (between BNFwt and BNFmut data) was also calculated using Excel. The Bioinformatics and Evolutionary Genomics Venn Diagram Software was used to calculate shared upregulated and downregulated genes between cell lines.

Gene Ontology analysis was conducted using ToppGene. For GO biological processes, molecular function and cellular components, all terms with q<0.05 from ToppGene were then submitted to Revigo for semantic trimming and diagramming with −log(q) as both size and color coding in the diagrams.

Unsupervised clustering of the 2029 significant genes of Exset8 was conducted using Morpheus software (hierarchical clustering; metric= Euclidean distance; Linkage method= complete; Cluster= Columns and rows).

Gene Set Expression analysis of entire ExSet (n=14554) pre-ranked was conducted using a pre-ranked list of log2 Fold Changes(μBNFwt(NVP-2-DMSO) – μBNFmut(NVP-2-DMSO) using GSEA PreRanked(Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA) software.

Transcription factor network analysis was performed using the ChEA3 online software.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database was interrogated for Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (SKCM) cases(n=472) and uveal melanoma (UVM) cases (n=80) using cBioPortal. The mutational status for BRAF (only V600 mutations), NRAS (G12/13, Q61 mutations), and NF1 was recorded for each patient, as well as the expression levels for E2F1-E2F8. Statistics (student’s t-test) and graphs were created using Graph Pad.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the American Skin Association’s J.T. Tai & Co. Foundation Medical Student Grants Targeting Melanoma and Skin Cancer Research (to SG), the NIH K24-CA149202 grant (to HT), the Melanoma Research Alliance (to HT), and the generous donors to the MGH on behalf of melanoma research. We also want to thank the Gray lab for synthesizing and providing us with NVP-2 and TS-032. Lastly, this work is dedicated to all those who have perished from melanoma.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Flaherty has served on the Board of Directors of Clovis Oncology, Strata Oncology, Loxo Oncology, and Checkmate Pharmaceuticals; Scientific Advisory Boards of X4 Pharmaceuticals, PIC Therapeutics, Sanofi, Amgen, Asana, Adaptimmune, Fount, Aeglea, Shattuck Labs, Tolero, Apricity, Oncoceutics, Fog Pharma, Neon, Tvardi, xCures, Monopteros, and Vibliome; consultant to Lilly, Novartis, Genentech, BMS, Merck, Takeda, Verastem, Boston Biomedical, Pierre Fabre, and Debiopharm; and research funding from Novartis and Sanofi. The remaining authors state no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations:

- CDK9

cyclin-dependent kinase 9

- BNFwt

BRAFwt/NRASwt/NF1wt cutaneous and uveal melanomas

- BNFmut

BRAFmut/NRASmut/NF1mut melanomas

- MFV

mean fractional viability

- pSer-2-CTD

phosphorylated serine-2 carboxy-terminal domain

- Pol-II

polymerase II

- ChIP

seq=chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- SKCM

skin cutaneous melanoma

- CDK9-hi

75th percentile CDK9 expression level

- CDK9-lo

25th percentile CDK9 expression level

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Alla V, Engelmann D, Niemetz A, Pahnke J, Schmidt A, Kunz M, et al. E2F1 in melanoma progression and metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102(2):127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwooll C, Lazzerini Denchi E, Helin K. The E2F family: specific functions and overlapping interests. EMBO J 2004;23(24):4709–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowiak B, Liu P, Phatnani HP, Fuda NJ, Cooper JJ, Price DH, et al. CDK12 is a transcription elongation-associated CTD kinase, the metazoan ortholog of yeast Ctk1. Genes & development 2010;24(20):2303–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2010;28(19):3167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2012;366(26):2455–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. The New England journal of medicine 2011;364(26):2507–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliades P, Abraham BJ, Ji Z, Miller DM, Christensen CL, Kwiatkowski N, et al. High MITF Expression Is Associated with Super-Enhancers and Suppressed by CDK7 Inhibition in Melanoma. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2018;138(7):1582–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RP. The CDK Network: Linking Cycles of Cell Division and Gene Expression. Genes & cancer 2012;3(11–12):731–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. The New England journal of medicine 2012;367(18):1694–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath EI, Bible K, Martell RE, Adelman DC, Lorusso PM. A phase 1 study of SNS-032 (formerly BMS-387032), a potent inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases 2, 7 and 9 administered as a single oral dose and weekly infusion in patients with metastatic refractory solid tumors. Investigational new drugs 2008;26(1):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent LN, Leone G. The broken cycle: E2F dysfunction in cancer. Nature reviews Cancer 2019;19(6):326–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GV, Eroglu Z, Infante J, Patel S, Daud A, Johnson DB, et al. Long-Term Outcomes in Patients With BRAF V600-Mutant Metastatic Melanoma Who Received Dabrafenib Combined With Trametinib. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2018;36(7):667–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loven J, Hoke HA, Lin CY, Lau A, Orlando DA, Vakoc CR, et al. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell 2013;153(2):320–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Mammalian cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends in biochemical sciences 2005;30(11):630–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng D, Carvajal RD. KIT as an Oncogenic Driver in Melanoma: An Update on Clinical Development. American journal of clinical dermatology 2019;20(3):315–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng P, Bedolla RG, Yun H, Fitzpatrick JE, Kumar AP, Ghosh R. Contextual role of E2F1 in suppression of melanoma cell motility and invasiveness. Mol Carcinog 2019;58(9):1701–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson CM, Jiang B, Erb MA, Liang Y, Doctor ZM, Zhang Z, et al. Pharmacological perturbation of CDK9 using selective CDK9 inhibition or degradation. Nat Chem Biol 2018;14(2):163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert C, Grob JJ, Stroyakovskiy D, Karaszewska B, Hauschild A, Levchenko E, et al. Five-Year Outcomes with Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Metastatic Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019;381(7):626–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouaud F, Hamouda-Tekaya N, Cerezo M, Abbe P, Zangari J, Hofman V, et al. E2F1 inhibition mediates cell death of metastatic melanoma. Cell death & disease 2018;9(5):527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusan M, Li K, Li Y, Christensen CL, Abraham BJ, Kwiatkowski N, et al. Suppression of Adaptive Responses to Targeted Cancer Therapy by Transcriptional Repression. Cancer discovery 2018;8(1):59–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonawane YA, Taylor MA, Napoleon JV, Rana S, Contreras JI, Natarajan A. Cyclin Dependent Kinase 9 Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2016;59(19):8667–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber JS, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. The New England journal of medicine 2012;366(8):707–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2012;366(26):2443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, Kluger HM, Carvajal RD, Sharfman WH, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2014;32(10):1020–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduzco D, Kuenzi BM, Kinose F, Sondak VK, Eroglu Z, Rix U, et al. Ceritinib Enhances the Efficacy of Trametinib in BRAF/NRAS-Wild-Type Melanoma Cell Lines. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2018;17(1):73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker SR, Mallinger A, Workman P, Clarke PA. Inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases as cancer therapeutics. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2017;173:83–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine 2017;377(14):1345–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Chen C, Sun X, Shi X, Jin B, Ding K, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 7/9 inhibitor SNS-032 abrogates FIP1-like-1 platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha and bcr-abl oncogene addiction in malignant hematologic cells. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2012;18(7):1966–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie G, Tang H, Wu S, Chen J, Liu J, Liao C. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor SNS-032 induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells via depletion of Mcl-1 and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein and displays antitumor activity in vivo. International journal of oncology 2014;45(2):804–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Liu S, Ye Q, Pan J. Transcriptional inhibition by CDK7/9 inhibitor SNS-032 abrogates oncogene addiction and reduces liver metastasis in uveal melanoma. Molecular cancer 2019;18(1):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Datasets related to this article can be found at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/hknwy2nggg/1, hosted at Mendeley (Guhan, Samantha (2020), “The molecular context of vulnerability for CDK9 suppression in triple wild-type melanoma: Supplemental Datasets ”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/hknwy2nggg.1).