Abstract

Purpose:

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed almost every aspect of our lives. Young adults are vulnerable to pandemic-related adverse mental health outcomes, but little is known about the impact on adolescents. We examined factors associated with perceived changes in mood and anxiety among male youth in urban and Appalachian Ohio.

Methods:

In June 2020, participants in an ongoing male youth cohort study were invited to participate in an online survey that included questions about changes in mood, anxiety, closeness to friends and family, and the major impacts of the pandemic. Weighted log-binomial regression models were used to assess the risk of worsened mood and increased anxiety. Chi-square tests were used to examine the association between perceived changes in mood and anxiety and perceived changes in closeness to friends and family and open-ended responses to a question about how COVID-19’s impact on participants.

Results:

Perceived worsened mood and increased anxiety during the pandemic were associated with higher household SES, older age, feeling less close to friends and family, and reporting that COVID-19 negatively affected mental health. A perceived increase in anxiety was also associated with a history of symptoms of depression or anxiety.

Conclusions:

Specific subgroups of male youth may be at heightened risk of worsening mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interventions should target vulnerable adolescents and seek to increase closeness to social contacts. Such efforts could involve novel programs that allow youth to stay connected to friends, which might mitigate the negative impact on mental health.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, youth

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has changed almost every aspect of young people’s lives due to stay-at-home orders and the continued restrictions on gatherings, in-person schooling, athletics, extra-curricular activities, and some travel. In combination with pandemic-related fear and worry, these changes to daily life have the potential to negatively affect a young person’s mental health, leading to increases in anxiety and depression.1 In June 2020 in the United States (US), past 30-day suicidal ideation was highest (25%) among young adults aged 18–24 years and declined considerably with increasing age.2 Moreover, 25% of young adults used substances to deal with the stress of the pandemic and 75% had at least one mental or behavioral health symptom during the past 30 days. Young adults in other countries are also experiencing the greatest levels of mental distress during this pandemic.3,4 Adolescents in the US5,6 and in other countries7–9 have also experienced deteriorations in mental health, happiness, and life satisfaction.

Physical distancing measures, which reduce coronavirus transmission, have led to feelings of isolation during the pandemic,10,11 which is concerning because studies conducted over the past 70 years suggest that loneliness and isolation increase the risk of depression and possibly anxiety among previously healthy children and adolescents.12 A longitudinal study conducted with Australian youth found that maintaining social connections protected adolescents from feelings of depression and anxiety, and improved satisfaction with life.9 Whom adolescents are connected to appears to be related to changes in mental health. For example, depressive symptoms were higher among Canadian adolescents who spent more time with friends and less time with family, but spending more time with both groups protected against loneliness.13

Existing health disparities have been exacerbated during the pandemic, as higher rates of COVID-19 related infections and deaths have been consistently reported in Black, Hispanic, and low-income communities.14–16 Mental health among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults has been negatively impacted by COVID-19;2 however, one study reported no association between race and ethnicity and symptoms of depression and anxiety among low-income college students during the pandemic.17 Other research has shown that students who reported lower socioeconomic status experienced more anxiety than those with more resources during the pandemic, which is consistent with the results from studies among college students in other countries.18,19

The type of community in which adolescents and young adults reside during the COVID-19 pandemic, i.e., urban or rural, might also affect their mental health outcomes. Though stay-at-home orders were often mandated statewide, those living in urban areas may have experienced more disruptions to their daily routines and may have had more COVID-19-related health concerns early in the pandemic due to infection rates being higher in cities. However, people living in Appalachian counties, most of which are rural, experience additional inequities due to high rates of tobacco use20 and opioid addiction21 that were present before the COVID-19 pandemic. These substance use behaviors could exacerbate existing negative mental health outcomes due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Important gaps remain in our understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the mental health of young people in the US and whether changes in mental health vary by race, income, and rural vs. urban residence. To address some of these gaps, we conducted a survey with participants in our ongoing cohort of adolescent and young adult males in Ohio to investigate whether the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in perceived changes in mood and anxiety among adolescent and young adult males and whether these perceived changes were consistent across age, region of residence, race, and household socioeconomic status (SES). Our aims were to: (1) identify youth who were most likely to perceive worsening mood and anxiety; (2) evaluate associations between two modifiable risk factors, closeness to family and closeness to friends, and perceived changes in mood and anxiety; and (3) use qualitative data to describe experiences of participants who perceived changes in mood and anxiety. We hypothesized that the participants most vulnerable to COVID-19, that is, those living in urban areas, older youth, non-White, and those with a lower household SES, would perceive worsening mood and anxiety. We also hypothesized that youth who perceived worsening mood and anxiety would also experience negative changes in their relationships with family and friends.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The Buckeye Teen Health Study (BTHS) COVID Supplemental Survey was designed to investigate how adolescent males in urban and Appalachian regions of Ohio have been impacted by COVID-19. The original BTHS cohort participants were recruited between January 2015 and June 2016 using probability address-based sampling and convenience sampling. Participants were between ages 11 and 16 and resided either in an urban Central Ohio county or one of nine Appalachian counties in Ohio.

The Institutional Review Board at our University approved the protocol. Among 1,220 adolescents surveyed at baseline, 989 participants who remained active within the BTHS cohort were eligible to participate in the COVID-19 Supplemental Survey in June 2020. Each participant received a postcard in the mail informing them of the supplemental survey and an incentive ($10 gift card) for their participation. Participants 18 and older received an email about the survey with a link to the 10-minute online questionnaire. For participants under the age of 18, parental or guardian permission was first obtained over the phone. Once parental permission was received, a survey link was emailed to the minor participant. Two reminders were sent after the initial survey. If the participant did not respond to the survey via email, they were then contacted via phone by an interviewer.

Measures

Primary Variables of Interest:

The two mental health variables were measures of perceived changes in mood and anxiety. Participants were asked to consider the date March 15, which is when bars and restaurants closed in Ohio. The statewide stay-at-home order was issued on March 22 and remained in effect until May 19. Mood was asked: “What is your general mood now compared to before March 15th?” with options to respond as “better,” “worse,” or “stayed the same.” Anxiety was similarly assessed with: “What are your anxiety levels like now compared to before March 15th” with answer options “increased,” “decreased,” or “stayed the same.”

Participants were also asked to report how their relationships with family and friends changed: “What are your feelings of closeness to your family [friends] like now compared to before March 15th?” Response options included “increased,” “decreased,” or “stayed the same.”

Finally, participants were asked one open-ended question, “In one sentence, describe how COVID-19 has affected you.” The research team reviewed the statements, double-coded each response for common themes, and revised the codebook as emergent themes occurred. Multiple codes could be indicated for each quote. Themes included negative mental health effects, social isolation, disruption to daily routine, negative financial impact, and education changes (see Table 1 for all themes, definitions, and sample quotes). An “other” code included reasons not related to the other categories or quotes that were not specific enough to be coded in other categories. Inter-rater agreement was excellent (Krippendorff’s alpha > 0.80 for all items).

Table 1:

Themes, Definitions, and Example Quotes from Open-Ended Question about the Impact of COVID-19

| Theme | Definition | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Job change/finances | Strain on finances or losing a job / income / work hours | “It’s kept me from being able to work as a musician or seasonal employee during the summer and has caused me a lot of personal financial issues.” |

| Mental health | Negative effect on mental health | “A return to a much more introverted, anxious, and sedentary lifestyle, after recently making attempts to become more social, outgoing, and level- headed.” |

| Social isolation, missing family or friends | Minimized social contact with friends and family, loneliness, isolation | “Covid-19 has taken away my life as I knew it before. I have become fearful around everyone. I feel isolated and I just want my life back.” |

| Change to daily routine | Unable to do normal daily activities, feeling bored at home, feeling shut in | “I’m inside all the time and not doing anything productive, which has started to get very boring and frustrating.” |

| Education changes or school event cancelations | Negative impact on education | “I hate not being in school and seeing all my friends every day. I’m having a difficult time doing the homework and keeping up with my studies in general.” |

| Something positive or selfgrowth | Mention of positive outcomes, self-growth | “Staying home because of COVID-19 has given me a lot of time to think about my life which has allowed me to make breakthroughs on my mental health.” |

| Health behavior change | Changes in health behavior due to COVID-19 | “It has made me more aware of personal space and how to decrease the spread of germs to my family and others” |

| No effect | No effect | “Due to where I live, COVID-19 really did not effect [sic] how I live. The rural aspects of my area allow for a social distance that has always been present.” |

| General Negative | Any negative comments without specific details | “It ruined what was supposed to be one of the most exciting and fun years of my life.” |

| General change | Any change-related comments without specific details | “It’s made my whole life weird” |

| Political statement | Comments questioning the existence COVID-19 or government/media mistrust | “Media propaganda” |

| Other | Anything not covered by other themes | “It’s made me feel confused about how everything will play out” |

Independent variables:

Age, region of residence at baseline, race and ethnicity, and household SES indicators were the independent variables of interest. Date of birth, region of residence, race, and ethnicity were assessed at baseline. From these data, age was calculated from participants’ reported date of birth and race and ethnicity were combined to create one race/ethnicity variable. For this analysis, we categorized the sample as non-Hispanic White vs. other race/ethnicity. Nearly all participants (95%) still lived in the same study county at follow-up and thus their classification as urban vs. Appalachian did not change. Household SES was assessed with two parent-reported variables from baseline: parent education (highest in the household, modeled as a college degree or higher vs. less) and household income (modeled as $50,000 or higher vs. less). An average Z-score was calculated and included in the models.18 Because a prior history of experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression could be associated with increases in these feelings during COVID-19, we also included baseline reporting of feelings of depression or anxiety during the past year (vs. never or more than a year ago).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize the sample that completed the COVID-19 supplemental survey. We also compared those who completed the supplemental survey to the non-responders among those who were invited to participate in the supplemental survey, as well as the non-responders and withdrawals from the original BTHS participants (Supplemental Table 1).

We used inverse-probability-of-attrition weights (IPAW) to control for a potential selection bias due to differences between survey respondents and non-respondents.22 This procedure assigned larger weights to participants who had lower probabilities of responding to the COVID-19 supplemental survey. To determine the factors associated with perceived changes in mood and anxiety, weighted log-binomial regression models were fit. Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated from the models. The reference group included both “stayed the same” or “improved mood / decreased anxiety” allowing us to determine RRs for perceived worsening mood or increased anxiety. The models were adjusted for age, region, race/ethnicity, the SES Z-score, history of depression or anxiety symptoms, and an indicator for the number of days since the start of the COVID-19 supplemental survey to control for time effects and the changing trend of the pandemic.

Chi-square tests were used to examine the association between perceived changes in mood and anxiety and changes in closeness to family and friends. Two-sided p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

For the open-ended responses, we explored how adolescents were impacted by COVID-19. Frequency distributions and chi-square tests were performed to assess distributions of themes, overall and by perceived changes in mood and anxiety. The Bonferroni-Holm method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons with the overall alpha set to 0.05. The open-ended responses were organized and coded using Microsoft Excel. All statistical analyses were conducted in R software (version 4.0).23

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Of the 989 participants invited to complete the supplemental survey, 571 responded, 7 refused to complete the survey, 101 did not receive parental permission, and 309 could not be reached. Compared to non-respondents, those who responded were younger and more likely to live in the urban county, be non-Hispanic White, have a parent with a college or higher education, and have a higher household income (Supplemental Table 1).

Approximately two-thirds of respondents lived in the urban county at baseline and the average age of the sample was 18.5 years (Table 2). Close to 80% of the sample reported being non-Hispanic White and 8.8% reported being non-Hispanic Black. With respect to household SES, about three-quarters had a household income over $50,000 and over half lived with a parent that had a college degree or higher level of education. Nearly one-third of participants reported that their mood had worsened (31.7%) or that their anxiety had increased (32.6%) since March 15, 2020 (Table 1).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 571 Adolescent and Young Adult Males Who Completed the COVID-19 Supplemental Survey, Ohio, June 2020

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Participant Characteristics | |

| Age – mean (SD) | 18.5 (1.6) |

| Region – n (%) | |

| Urban | 362 (63.4) |

| Appalachian | 209 (36.6) |

| Race/Ethnicity – n (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 456 (79.9) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 50 (8.8) |

| Other | 65 (11.4) |

| Household income | |

| $50,000 or more | 408 (74.3) |

| Less than $50,000 | 141 (25.7) |

| Parental education | |

| College degree or above | 321 (56.9) |

| No college degree | 243 (43.1) |

| Tested for COVID-19 – n (%) | |

| Yes | 38 (6.7) |

| No | 528 (93.3) |

| Mental Health Indicators | |

| History of depressive or anxiety symptoms - n (%) | 333 (64.8) |

| Mood changes during pandemic – n (%) | |

| Improved/stayed the same | 369 (65.2) |

| Worsened | 179 (31.6) |

| Don’t know | 18 (3.2) |

| Anxiety changes during pandemic – n (%) | |

| Decreased/stayed the same | 358 (63.3) |

| Increased | 183 (32.3) |

| Don’t know | 25 (4.4) |

Factors Associated to Changes in Mood and Anxiety

Higher SES was associated with an increased risk of perceived worsened mood (RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.08–1.57; Table 3). Age and race/ethnicity were not significantly associated with perceived worsened mood, but there was suggestion of perceived worsened mood for older age (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.99–1.16) and Other race/ethnicity (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.98–1.72). Neither place of residence nor history of symptoms of depression or anxiety were significantly associated with perceived worsened mood.

Table 3.

Weighted log-binomial regression model for changes in mood and anxiety between March 15, 2020 and time of survey

| Baseline characteristics | Worse mood* | Increased anxiety† | ||

| RR (95% CI) | p-value | RR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 0.084 | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) | 0.030 |

| Urban region (Ref: Appalachia) | 0.98 (0.75–1.16) | 0.877 | 0.80 (0.64–1.00) | 0.054 |

| Other Race/Ethnicity (Ref: NH White) | 1.30 (0.98–1.72) | 0.066 | 1.21 (0.95–1.54) | 0.131 |

| SES | 1.30 (1.08–1.57) | 0.006 | 1.15 (1.01–1.33) | 0.048 |

| History of depressive or anxiety symptoms (Ref: No) | 1.20 (0.91–1.58) | 0.191 | 1.64 (1.22–2.20) | <0.001 |

Model adjusted for an indicator time trend (days since baseline COVID-19 supplemental survey)

Referent: Unchanged or better mood

Referent: Unchanged or decreased anxiety

SES, age, and region of residence were significantly associated with perceived increased anxiety (Table 4). Higher SES was associated with perceived increased anxiety compared to unchanged or decreased anxiety (RR 1.15, 95% 1.01–1.33). Both older age (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01–1.33) and a history of depression or anxiety symptoms (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.22–2.20) were associated with perceived increased anxiety. Urban residence was associated with a lower risk of perceived increased anxiety compared to Appalachian residents, but this difference was only marginally significant (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.64–1.00). Race/ethnicity was not significantly associated with perceived increased anxiety (RR: 1.21 (0.95–1.54, 95% CI 0.131).

Table 4.

Frequencies of Themes about the Impact of COVID-19 on Adolescent and Young Adult Males in Ohio in June-August, 2020 (n=566)a

| Theme | Total n(%) | Perceived Change in Mood n (%) | Perceived Change in Anxiety n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worse | Same/Better | Increased | Same/Decreased | ||

| Change to routine or boredom | 137 (24.2) | 57 (31.8) | 76 (20.6)c | 45 (24.6) | 85 (23.7) |

| Education changes or school event cancelations | 105 (18.6) | 25 (14.0) | 80 (21.7) | 30 (16.4) | 71 (19.8) |

| Social isolation or mention of family | 96 (17.0) | 43 (24.0) | 48 (13.0)c | 35 (19.1) | 58 (16.2) |

| Something positive or self-awareness | 79 (14.0) | 18 (10.1) | 60 (16.3) | 25 (13.7) | 52 (14.5) |

| Mental health | 73 (12.9) | 45 (25.1) | 25 (6.8)d | 45 (24.6) | 24 (6.7)d |

| No effect | 71 (12.5) | 6 (3.4) | 62 (16.8)d | 9 (4.9) | 58 (16.2)d |

| Job change/Finances | 53 (9.4) | 22 (12.3) | 30 (8.1) | 21 (11.5) | 30 (8.4) |

| Health behavior change | 32 (5.7) | 8 (4.5) | 24 (6.5) | 6 (3.3) | 22 (6.1) |

| General negative | 31 (5.5) | 14 (7.8) | 15 (4.1) | 14 (7.7) | 17 (4.7) |

| General change | 20 (3.5) | 6 (3.4) | 12 (3.3) | 7 (3.8) | 12 (3.4) |

| Political | 11 (1.9) | 2 (1.1) | 9 (2.4) | 1 (0.5) | 9 (2.5) |

| Physical health | 6 (1.1) | 5 (2.8) | 1 (0.3) | 5 (2.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.1) |

p-values adjusted using the Bonferroni-Holm method for multiple comparisons

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Association Between Changes in Mood/Anxiety and Closeness to Family/Friends and Other Impacts

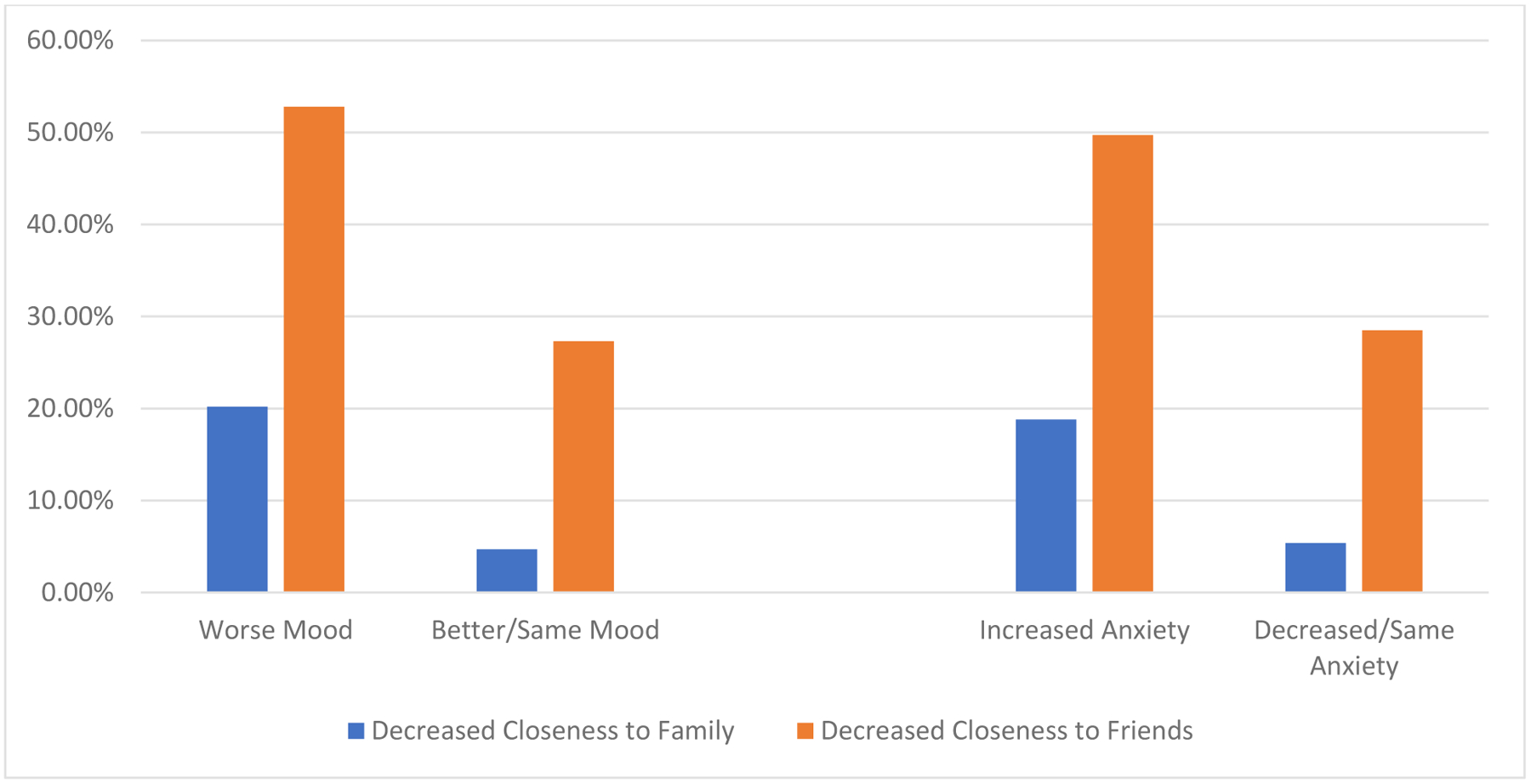

A greater percentage of participants reported decreased closeness to friends (35.7%) than decreased closeness to family (9.7%) (Figure 1). Changes in perceived mood and anxiety were associated with changes in closeness to friends and family. Compared to those whose perceived mood did not change or improved, respondents with perceived worsened mood had a higher prevalence of reporting decreased closeness to friends (52.8% v 27.3%, p < 0.001) or family (20.7% vs. 4.7%, p < 0.001). Similar associations were noted for perceived increased anxiety: compared to those whose perceived anxiety did not change or decreased, respondents with perceived increased anxiety had a higher prevalence of reporting decreased closeness to friends (49.7% vs. 28.5%, p < 0.001) or family (18.8% vs. 5.4%, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Changes in closeness to family and friends by perceived changes in mood and anxiety* *All p-values from chi-square tests were < 0.001

Association Between Changes in Mood/Anxiety and Open-Ended COVID-19 Impacts

Perceived changes in mood and anxiety were associated with some of the themes from the open-ended responses to the question about the impact of COVID-19 (Table 4). Participants who perceived worsened mood or increased anxiety had a higher prevalence of reporting an impact related to poor mental health compared to those whose mood or anxiety improved or stayed the same (25.1% vs. 6.8% and 24.6% vs. 6.7% for mood and anxiety, respectively; p < 0.001). The prevalence or reporting no impact of the pandemic was lower among participants who perceived worsened mood (3.4% vs. 16.8%, p < 0.001) or increased anxiety (4.9% vs. 16.2%, p < 0.001). Finally, participants who perceived worsened mood reported a higher prevalence of social isolation (24.0% vs. 13.0%, p < 0.01) and change to routine (31.8% vs. 20.6%, p < 0.01).

Discussion

Although young people generally do not suffer the greatest physical health impacts of COVID-19, the pandemic has nonetheless contributed to worsening mental health in this group. We found that perceived worsened mood and increased anxiety during the pandemic were associated with higher household SES, older age, and having a history of either anxiety and/or depression. These perceived changes were also associated with decreased feelings of closeness to friends and family. The open-ended responses provided additional support to the survey findings, as participants who perceived worsened mood or increased anxiety also, in their own words, reported that COVID-19 most impacted their mental health negatively. Perceived increased anxiety was also associated with increased reporting of social isolation and more changes to one’s daily routine.

Youth who perceived worsened mood and increased anxiety reported feeling less close to friends and family.24 This suggests that strong social relationships might be a protective factor during the pandemic. Our findings are consistent with studies of adolescents and college students in other countries that have reported an association between social isolation and symptoms of depression or anxiety during the pandemic.9,18,19 It is important to note that not all social interactions are equal, as one study reported that virtual connections were associated with increased feelings of depression.13 Future programming, through schools or the community, should focus on ways to promote meaningful, and safe, interactions between youth and their friends. Within the family, parents should seek appropriate counseling if their child is experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression.25

Both perceived worsened mood and increased anxiety were associated with SES, but not in the way we had hypothesized or that is consistent with other literature published during the COVID-19 pandemic. Shevlin et al., for example, reported that symptoms of anxiety and depression were associated with a loss of income or living in a low-income household pre-pandemic.3 Our observed association between higher SES and perceived worsened mood or increased anxiety might be because adolescents who live in higher SES households experienced more disruptions in everyday life, as well as school and extracurricular activities, which have been shown to increase symptoms of anxiety and depression.18 Those in higher SES households are also more likely to have one or more parents working from home, which has been linked to increased anxiety and stress during the pandemic.9 With more family members at home, there are more changes to the family’s daily routine, possibly leading to more stress in the household. Such disruptions could lead to exaggerated responses among youth if the parents themselves have anxiety surrounding the pandemic.26 Further research is needed to explore these possible connections since our finding are inconsistent with other current research.

The limitations of this study are important to consider when interpreting the findings. First, our cohort consists only of male youth, and it is possible that COVID-19 has had a more negative impact on females, as noted in at least one study of college students.19 Second, parental income was assessed at baseline, thus not reflecting any loss of income or unemployment that occurred due to the pandemic. Third, the assessments of how COVID-19 has impacted mental health and other behaviors occurred at the same time, limiting our ability to fully examine the direction of the association between worsened mood, increased anxiety, and feelings of being less connected to friends and family. Similarly, we conducted the survey at one point during the pandemic. It is quite possible that perceived mood and anxiety changes were different while the stay-at-home order was in place or later in the pandemic, when surges in cases occurred at the end of 2020.27 Through ongoing surveys in this cohort, we will have the opportunity to survey participants again about their mental health. Another limitation is that mood and anxiety were not measured using established scales; rather, participants were simply asked about perceived changes since March 15, 2020. Though there is not any supporting literature, it is possible that variations in how adolescents answer such a question may be related to some of the variables under study. For example, adolescents from higher SES households may perceive greater changes in mood and anxiety because their parents are home more often and are thus inquiring more frequently about changes in mental health.

Two key strengths of the study include the ability to leverage the ongoing cohort study to assess adolescents’ experiences at a critical time during the pandemic, and the use of data that had been collected before the start of the pandemic. Moreover, the cohort participants reside in different parts of the state, which allowed us to capture differing experiences in Appalachian and urban Ohio.

Conclusions

Youth who live in higher SES households, have a history of anxiety and/or depression, and are older perceived worsened mood and increased anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Importantly, there was a significant association between feeling less close to friends and friends and these perceived negative mental health symptoms. Parents, schools, and community organizations should focus on strategies to improve the mental health and wellbeing of youth, particularly those youth who appear to be at highest risk of worsened mental health. Such efforts could involve novel programs that allow youth to stay close with friends. In family environments, activities to improve closeness should be encouraged—both to buffer youth from worsening mental health and to potentially facilitate conversations about mental health outcomes. These strategies include counseling parents and other caregivers to use the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to model healthy coping.25 When we reach the other side of this global pandemic, researchers should examine the factors that promoted resilience among youth and develop interventions to strengthen their ability to cope with stressful and uncertain situations.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contributions.

Male youth who perceived increased anxiety and worsened mood during the COVID-19 pandemic tended to be older, from higher income households, and had a history of symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. Because there was a significant association between mental health deterioration and feeling less close to family and friends, strategies to strengthen youths’ social connections should be explored.

Funding:

This project was supported by:

The National Institutes of Health, grant P50CA180908

The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presentation:

Eleanor Tetreault gave a presentation titled “COVID-19 impact on mental health, lifestyle, and substance use behaviors in cohort of adolescent boys in Ohio” at the 10th Annual Health Summit- Community-engaged Research in Translational Science: Innovations to Improve Health in Appalachia. September 21, 2020.

References

- 1.Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czeisler MÉ. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shevlin M, McBride O, Murphy J, et al. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open. 2020;6(6). doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pieh C, Budimir S, Probst T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. J Psychosom Res. 2020;136:110186. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuine TA, Biese K, Hetzel SJ, et al. Changes in the Health of Adolescent Athletes: A Comparison of Health Measures Collected Before and During the CoVID-19 Pandemic. J Athl Train. Published online April 22, 2021. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0739.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazmararian J, Weingart R, Campbell K, Cronin T, Ashta J. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Students From 2 Semi-Rural High Schools in Georgia. J Sch Health. 2021;91(5):356–369. doi: 10.1111/josh.13007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawke LD, Barbic SP, Voineskos A, et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on Youth Mental Health, Substance Use, and Well-being: A Rapid Survey of Clinical and Community Samples: Répercussions de la COVID-19 sur la santé mentale, l’utilisation de substances et le bienêtre des adolescents : un sondage rapide d’échantillons cliniques et communautaires. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(10):701–709. doi: 10.1177/0706743720940562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munasinghe S, Sperandei S, Freebairn L, et al. The Impact of Physical Distancing Policies During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health and Well-Being Among Australian Adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(5):653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(1):44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Double Pandemic Of Social Isolation And COVID-19: Cross-Sector Policy Must Address Both. HealthCare Dynamics International. Published June 30, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.hcdi.com/the-double-pandemic-of-social-isolation-and-covid-19-cross-sector-policy-must-address-both/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cudjoe T, Kotwal A. “Social Distancing” Amid a Crisis in Social Isolation and Loneliness - Cudjoe - 2020 - Journal of the American Geriatrics Society - Wiley Online Library. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jgs.16527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218–1239.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement. 2020;52(3):177–187. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

- 15.Ogedegbe G, Ravenell J, Adhikari S, et al. Assessment of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hospitalization and Mortality in Patients With COVID-19 in New York City | Health Disparities | JAMA Network Open | JAMA Network. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2773538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Oppel R, Gebeloff R, Lai K, Wright W, Smith M. The Fullest Look Yet at the Racial Inequity of Coronavirus - The New York Times. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/05/us/coronavirus-latinos-african-americans-cdc-data.html

- 17.Rudenstine S, McNeal K, Schulder T, et al. Depression and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic in an Urban, Low- Income Public University Sample. J Trauma Stress. Published online October 12, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jts.22600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wathelet Marielle; Duhem Stéphane; Vaiva Guillaume; Baubet Thierry; Habran Enguerrand; Veerapa Emilie;, Debien Christophe; Molenda Sylvie; Horn Mathilde; Grandgenèvre Pierre; Notredame Charles-Edouard; D’Hondt Fabien. Factors Associated With Mental Health Disorders Among University Students in France Confined During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Published online September 17, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mattingly DT, Tompkins LK, Rai J, Sears CG, Walker KL, Hart JL. Tobacco use and harm perceptions among Appalachian youth. Prev Med Rep. 2020;18. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schalkoff CA, Lancaster KE, Gaynes BN, et al. The opioid and related drug epidemics in rural Appalachia: A systematic review of populations affected, risk factors, and infectious diseases. Subst Abus. 2020;41(1):35–69. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1635555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):119–128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318230e861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Core Team (2020). R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/oxygen-consuming-substances-in-rivers/r-development-core-team-2006

- 24.Rogers AA, Ha T, Ockey S. Adolescents’ Perceived Socio-Emotional Impact of COVID-19 and Implications for Mental Health: Results From a U.S.-Based Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2021;68(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courtney D, Watson P, Battaglia M, Mulsant BH, Szatmari P. COVID-19 Impacts on Child and Youth Anxiety and Depression: Challenges and Opportunities. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(10):688–691. doi: 10.1177/0706743720935646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whittle S, Bray K, Lin S, Schwartz O. Parenting and child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Published online August 5, 2020. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/ag2r7 [DOI]

- 27.Leidman E COVID-19 Trends Among Persons Aged 0–24 Years — United States, March 1–December 12, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.