Abstract

Purpose

We examined the combined influences of race/ethnicity and neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) on long-term survival among patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

Methods

Data from the 2000–2015 NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER-18) were used. Census tract-level SES index was assessed in tertiles (low, medium, high SES). Competing-risk modeling was used to estimate sub-hazard ratios (SHR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for SES tertile adjusted for sex and age at diagnosis and stratified by race/ethnicity.

Results

Overall, living in a low SES neighborhood was associated with worse MM survival. However, we observed some variation in the association by racial/ethnic group. Living in a low versus a high SES neighborhood was associated with a 35% (95% CI = 1.16–1.57) increase in MM-specific mortality risk among Asian/Pacific Islander cases, a 17% (95% CI = 1.12–1.22) increase among White cases, a 14% (95% CI = 1.04–1.23) increase among Black cases, and a 7% (95% CI = 0.96–1.19) increase among Hispanic cases.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the influence of both SES and race/ethnicity should be considered when considering interventions to remedy disparities in MM survival.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Socioeconomic status, Race/ethnicity, Survival

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most commonly diagnosed hematological malignancy in the United States [1]. Recent advances in treatment and supportive care have improved the long-term outcomes for MM [2, 3]. However, this improvement has not been equal across racial/ethnic groups [4]. For example, patients of minority racial or ethnic backgrounds, particularly non-Hispanic Black patients, continue to have lower survival rates than non-Hispanic White patients [5, 6].

The underlying causes of these racial/ethnic differences in survival in patients with MM are not well understood. These disparities in survival may be attributed, in part, to differences in neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) [7]. Family SES, neighborhood SES, and race/ethnicity are robust predictors of health and health care utilization variations but are usually considered separately. However, it is increasingly recognized that race/ethnicity and family SES likely have synergistic impacts on health-related outcomes, given complex social, political, and historical factors that structure economic opportunities and their advantages differentially across racial/ethnic groups [8, 9]. A comprehensive understanding of the patterns and determinants of health disparities requires that these dimensions of social identity and position are studied together [10–12].

Few studies on MM survival have adopted this approach. A previous study examining the association between SES and MM cancer mortality between non-Hispanic White and Black Americans [13] found that patients with low SES had an increased mortality rate compared with patients with high SES. However, the authors did not examine whether the magnitude of the association between SES and mortality differed across racial/ethnic groups. Furthermore, little is known about the effects of SES on MM survival among Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander patients. To address this gap, we evaluated the effect of neighborhood SES on the survival of adults with MM by race/ethnicity.

Methods

Study population and data sources

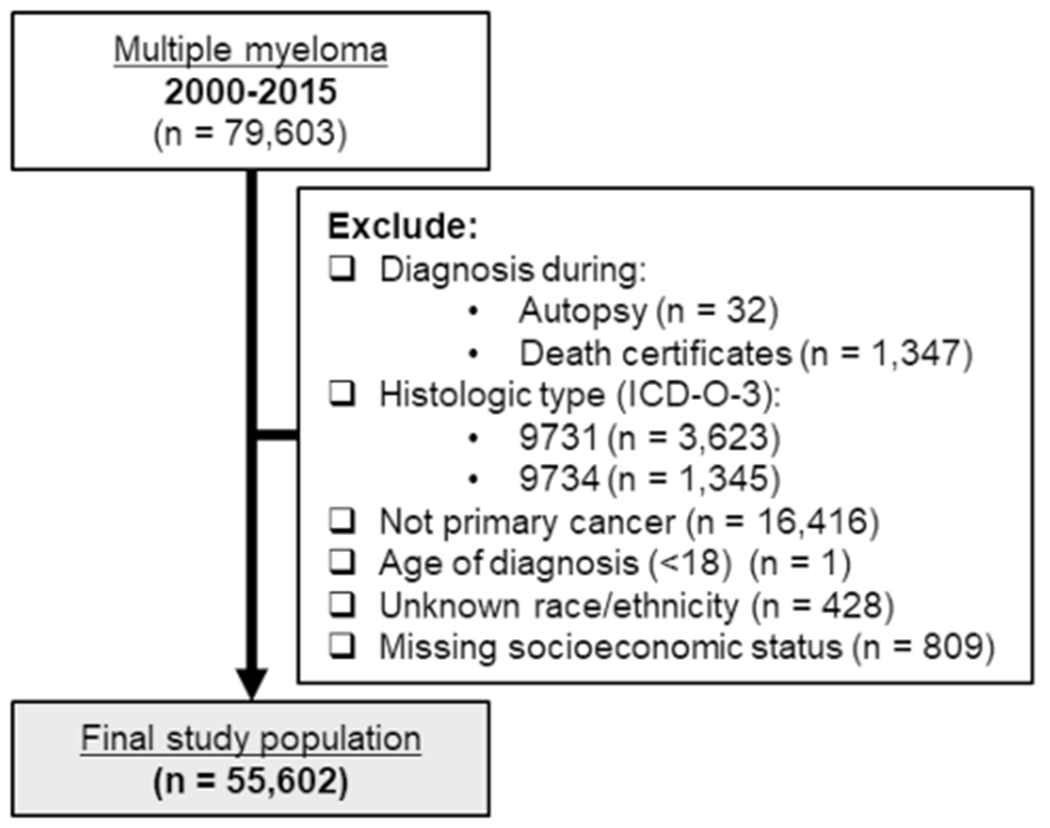

This study was a secondary analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) of the National Cancer Institute (https://seer.cancer.gov/). Data came from the SEER-18 registries excluding Alaska [14] and were linked to census tract attributes (2000–2015), including the SES index described below. We included all MM diagnoses reported to the SEER Program between 2000 and 2015, as defined by ICD-O-3 morphology code 9732. The US SEER Program data were extracted using SEER*Stat’s client-server mode [14]. We excluded cases diagnosed during autopsy or on death certificates (n = 1,379), diagnoses of plasmacytoma (ICD-O-3 morphology codes 9731 and 9734; n = 4,968), cases where MM was not the first diagnosed cancer (n = 16,416), cases where the age of diagnosis was < 18 years old (n = 1), and cases with unknown race/ethnicity (n = 428) or missing neighborhood SES (n = 809).

Neighborhood socioeconomic status

The National Cancer Institute’s census tract-level SES index is a time-dependent composite score, which has been described in detail elsewhere [15]. In brief, the index was constructed using factor analysis of median household income, median house value, median rent, percentage of the population living below 150% of the poverty line, education index, percent working class, and percent unemployed. This index is estimated using data from the US Decennial Census long form survey and a series of American Community Surveys (ACS). The SES index is linked to cancer cases at the census tract level by matching the survey year with the patient’s address during the year of the cancer diagnosis. Census tract SES index values were provided as tertiles, with the first tertile corresponding to low neighborhood SES, the second as medium neighborhood SES, and the third as high neighborhood SES [15].

Other covariates

SEER registries collect information on sex, year of birth, year of cancer diagnosis, the patient’s marital status at diagnosis, and first-line treatment (radiation, chemotherapy, surgery). Years of diagnosis and birth were used to calculate age at MM diagnosis. The race/ethnicity categories evaluated in this analysis are Hispanic, non-Hispanic White (White), non-Hispanic Black (Black), and non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islanders (API). We excluded 272 cases with other racial/ethnic groups from the stratified analysis.

Statistical analysis

Categorical characteristics were summarized as percentages and compared across categories of neighborhood SES and race/ethnicity with Chi-square tests, while between-group differences in continuous variables were compared by t tests. Follow-up time was defined as the date of diagnosis until death, or end of follow-up, December 31, 2015. As defined by the SEER data, participants who died from other non-MM causes were considered having a competing risk. Participants who were alive as of 31 December 2015 were censored. Survival differences were compared according to tertile of neighborhood SES using cumulative incidence curves and Pepe and Mori tests [16]. Interaction between SES and race was evaluated using a likelihood ratio test. Multivariable competing risks models using Fine and Gray’s proportional subhazard models were used to assess the association of neighborhood SES and MM mortality risk, stratified by race/ethnicity [16]. The final set of covariates included in the models were sex and age at diagnosis, selected based on clinical judgment and the 10% change-inestimate criterion. We used a complete case analysis.

Results

During the period of 2000–2015, a total of 79,603 cases were diagnosed with MM. In this analysis, we included a total of 55,602 cases of MM after applying the exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of those included in the analysis, 12% were Hispanic participants, 64% white participants, 18% Black participants, and 6% API participants. Among the cases included in this analysis, 31% lived in neighborhoods with low SES. Higher proportions of cases diagnosed with MM who lived in neighborhoods with high SES were White or API (76% and 8%) cases than the proportion of cases from low SES neighborhoods (46% and 3%). In contrast, lower proportions of cases diagnosed with MM who lived in a neighborhood with high SES were Hispanics or Blacks (7% and 8%) cases than the proportion of cases from low SES neighborhoods (17.5% and 32%). Slightly more men were diagnosed with MM than women. By the end of the study period, 41% of MM cases living in high SES neighborhoods were still alive, while only 34% of MM cases living in low SES neighborhoods were still alive. Follow-up time was slightly longer for cases in high SES neighborhoods (3 years) than for cases in lower SES (2 years) neighborhoods (Table 1). In high SES neighborhoods, the mean age at diagnosis was lowest among Black adults (64 years) and Hispanic adults (65 years) compared to API adults (68 years) and White adults (69 years) (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study population of multiple myeloma cases diagnosed between 2000 and 2015 in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Registry

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and pathological characteristics of adults with multiple myeloma by neighborhood SES (n = 55,602) from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Registry, 2000–2015

| Neighborhood SES |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | |

| N | 19,998 | 18,460 | 17,144 |

| Race/ethnicity, %* | |||

| Hispanics | 7.4 | 11.9 | 17.5 |

| Whites | 76.0 | 66.0 | 46.3 |

| Blacks | 8.4 | 15.5 | 32.0 |

| Asian or Pacific Islanders | 8.0 | 6.1 | 3.5 |

| Other | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Men, %* | 55.6 | 53.4 | 51.3 |

| Married, %a,* | 67.2 | 59.5 | 50.7 |

| Age at diagnosis* | |||

| 18–49 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 8.7 |

| 50–69 | 45.5 | 44.3 | 44.9 |

| ≥ 70 | 46.9 | 48.0 | 46.5 |

| Mean (SD), years | 68.0 ± 12.6 | 68.1 ± 12.6 | 67.5 ± 12.7 |

| Radiation treatment, %b,* | 18.2 | 19.2 | 17.8 |

| Chemotherapy, %b,* | 61.3 | 60.3 | 57.6 |

| Deaths, %* | |||

| Alivec | 41.3 | 36.7 | 34.3 |

| Multiple myeloma | 42.7 | 46.1 | 45.4 |

| Any other cause | 16.0 | 17.3 | 20.4 |

| Follow-up time* | |||

| Mean (± SD), years | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 3.0 ± 3.1 | 2.7 ± 2.9 |

Statistically significant difference between neighborhood groups (p value < 0.05)

Missing values: Marital status (n = 3,633)

among those receiving treatment versus none/unknown

Alive as of December 2015

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical, and pathological characteristics of adults with multiple myeloma by categories jointly defined by race/ethnicity and neighborhood SES (n = 55,602), from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Registry, 2000–2015

| Hispanics Neighborhood SES |

Whites Neighborhood SES |

Blacks Neighborhood SES |

Asian or Pacific Islanders Neighborhood SES |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | High | Medium | Low | High | Medium | Low | High | Medium | Low | |

| N | 1,469 | 2,193 | 3,001 | 15,205 | 12,177 | 7,932 | 1,679 | 2,856 | 5,488 | 1,599 | 1,134 | 597 |

| Men, % | 52.6 | 53.9 | 53.3 | 56.7 | 54.9 | 54.4 | 50.6 | 48 | 45.7 | 52.8 | 50.7 | 53.1 |

| Married, %a | 64.3 | 61.8 | 54.7 | 68.2 | 61.9 | 56.8 | 54.3 | 44.7 | 38.4 | 73.4 | 67.6 | 64.3 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| 18–49 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 13.1 | 12.1 | 11.0 | 9.2 | 7.1 | 5.7 |

| 50–69 | 49.3 | 47.2 | 48.8 | 44.2 | 41.4 | 39.7 | 53.2 | 53.6 | 50.3 | 45.3 | 45.9 | 43.0 |

| ≥70 | 38.3 | 39.9 | 37.8 | 49.4 | 52.8 | 54.8 | 33.6 | 34.2 | 38.7 | 45.5 | 46.9 | 51.3 |

| Mean (SD), years | 65.1 ± 13.0 | 65.0 ± 13.0 | 64.5 ± 12.9 | 68.8 ± 12.4 | 69.7 ± 12.2 | 70.1 ± 12.1 | 63.8 ± 12.6 | 64.2 ± 12.5 | 65.4 ± 12.6 | 67.1 ± 12.6 | 67.5 ± 12.1 | 69.1 ± 12.1 |

| Radiation, %b | 18.9 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 18.4 | 19.3 | 17.7 | 16.1 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 17.2 | 19.0 | 16.4 |

| Chemotherapy, %b | 65.1 | 62.9 | 61.2 | 60.6 | 59.8 | 56.5 | 63.6 | 60.4 | 57.8 | 62.1 | 59.8 | 53.6 |

| Deaths, % | ||||||||||||

| Alivec | 43.8 | 44.1 | 41.0 | 39.7 | 33.4 | 29.7 | 46.5 | 43.9 | 37.0 | 48.3 | 39.4 | 35.7 |

| Multiple myeloma | 42.3 | 41.6 | 41.8 | 43.9 | 49.0 | 49.8 | 37.5 | 38.9 | 40.9 | 36.8 | 42.2 | 45.9 |

| Any other cause | 13.9 | 14.3 | 17.2 | 16.4 | 17.6 | 20.5 | 16.1 | 17.2 | 22.1 | 14.8 | 18.3 | 18.4 |

| Follow-up time | ||||||||||||

| Mean (± SD), years | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 2.9 ± 3.2 | 2.6 ± 2.9 | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 2.9 ± 3.1 | 2.6 ± 2.9 | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 3.2 ± 3.2 | 2.9 ± 3.0 | 3.2 ± 3.2 | 2.8 ± 2.9 | 2.5 ± 2.7 |

Missing values: Marital status (n = 3,633)

Among those receiving treatment versus none/unknown

Alive as of December 2015

Association between neighborhood SES and multiple myeloma survival

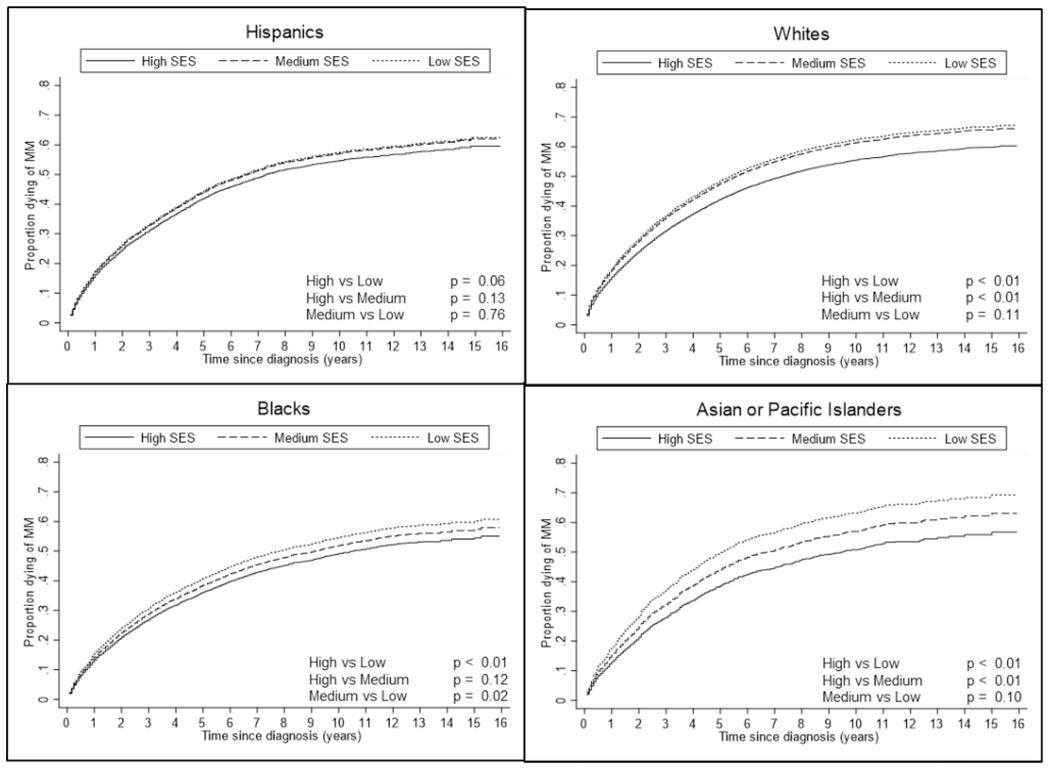

Cumulative incidence curves by neighborhood SES, stratified by race/ethnicity, showed that high SES was associated with better cancer-specific survival, particularly among White, Black, and API adults diagnosed with MM. Among Hispanic adults diagnosed with MM, there was not a large difference in cancer-specific survival between SES categories (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative Incidence Curves of multiple myeloma-specific death by Race/Ethnicity and Neighborhood SES, among the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Registry, 2000–2015

After adjusting for sex and age at diagnosis, API adults living in low SES neighborhoods were 35% (95% CI = 1.16–1.57) more likely to die from MM than API adults living in high SES neighborhoods. White and Black adults living in low SES neighborhoods were approximately 17% (95% CI = 1.12–1.22) and 14% (95% CI = 1.04–1.23) more likely to die from MM than White and Black adults living in high SES neighborhoods, respectively. Hispanic adults living in low SES neighborhoods were 9% (95% CI = 0.96–1.19) more likely to die from MM than Hispanic adults living in high SES neighborhoods. However, this estimate was not statistically significant (Table 3). Overall, we observed a statistically significant interaction between SES and race/ethnicity (p value = 0.04).

Table 3.

Association between neighborhood SES and multiple myeloma-specific mortality risk by race/ethnicity, from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Registry, 2000–2015

| Crude SHR (95% CI) | Age and sex-adjusted SHR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic whites | ||

| Low | 1.20 (1.16–1.26) | 1.17 (1.12–1.22) |

| Medium | 1.17 (1.13–1.22) | 1.15 (1.11–1.19) |

| High | (ref) | (ref) |

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | ||

| Low | 1.17 (1.07–1.28) | 1.14 (1.04–1.23) |

| Medium | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) |

| High | (ref) | (ref) |

| Hispanic | ||

| Low | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) | 1.09 (0.98–1.20) |

| Medium | 1.07 (0.96–1.18) | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) |

| High | (ref) | (ref) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islanders | ||

| Low | 1.41 (1.22–1.64) | 1.35 (1.16–1.57) |

| Medium | 1.19 (1.05–1.35) | 1.18 (1.04–1.33) |

| High | (ref) | (ref) |

(SHR) Subhazard ratio, calculated using competing risks regression, stratified by race/ethnicity

Discussion

In this study, adults with MM who lived in neighborhoods with high SES at diagnosis experienced better survival than adults with MM who lived in middle or low SES neighborhoods after adjusting for sex and age at diagnosis. In an analysis stratified by race/ethnicity, the association between mortality risks among high SES versus low SES was statistically significant in API, White, and Black populations; however, estimates for Hispanic adults were weaker and did not reach statistical significance.

Racial/ethnic disparities in MM survival are well documented; however, research on SES disparities has been less consistent [13, 17]. Similar to our findings, previous studies evaluating the association between MM mortality and SES have found that individuals with low SES have an increased mortality rate than individuals with high SES among Black and White populations. [13]. However, other studies have found an elevated risk of MM mortality among high neighborhood SES relative to low SES individuals [17], while some have observed similar MM mortality across neighborhood SES categories [18]. Our findings suggest that these disparate findings may be due to the fact that these studies did not consider how the association between SES and MM survival differs across racial/ethnic groups. Thus, we provide a more nuanced picture of the SES-MM survival relationship.

Various biologic factors, including cytogenetic or molecular mutations, could contribute to the observed differences in MM mortality. [19] However, attributing observed racial/ethnic differences to inherent biological factors is inconsistent with a growing understanding of the role of social environment in shaping biology, including the molecular processes linked to disease. [20] There are also factors related to access to treatment and novel therapies that could be contributing to the MM mortality differences observed in our findings. [21] These factors likely differ across racial/ethnic groups in how they shape health. Recent data suggest that disparities exist in the use of novel myeloma therapies and suggest that a lack of access to treatment could result in poorer patient outcomes. [22] In one study, receipt of autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) was associated with improved overall survival among patients with MM; this increased survival was notably higher among White patients compared with Black patients, and adults with higher SES compared to adults with lower SES [23].

Health disparity researchers are increasingly drawing on intersectionality theory from Black feminist scholarship, which focuses on the interconnected nature of social identities and positions to understand how health outcomes are patterned across social groups [24–26]. Intersectionality theory posits that dimensions of structural inequality such as racism, classism, etc., are mutually constitutive (i.e., intersectional), and thus, social groups at the nexus of more than one marginalized identity experience unique forms of disadvantage [24–26]. Such forms of disadvantage are hypothesized to shape lived experiences and life chances, thus, also shaping exposure to health risk factors and health care access [24–26]. In terms of MM survivorship, an intersectional perspective suggests that the material and social resources that economic advantage confers differ in meaningful ways across racial/ethnic groups, which can help explain our findings in several ways.

First, the lower cancer survival rates observed among low as compared with high SES cases may reflect less access to cancer treatment or medical care [27]. Rather than conceptualizing these factors as independent, interpersonal-level determinants, however, intersectionality theory helps situate them as interconnected downstream effects of experiencing both classism/poverty and systemic racism [28]. Second, the differences within racial/ethnic minority groups in MM-related mortality could be understood in part as stemming from unique social factors, including those that relate to neighborhood context, which can influence their lifestyle and risk factors (including environmental exposures, housing quality, etc.), as well as their individual SES and access to healthcare. For this reason, results may differ among the subgroups making up these heterogeneous populations; further research with more detailed data on race/ethnicity is required to explore this possibility. This also underscores the importance of moving beyond the use of overly simplistic “racial/ethnic minority” umbrella groups in epidemiologic research. Finally, intersectionality theory can help inform the implications of our findings. Neighborhood SES likely operates at multiple levels to shape MM-related mortality, including but not limited to environmental exposures, access to care and other resources, and the ability to engage in health-promoting behaviors.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including evaluating both race/ethnicity and neighborhood SES together to better understand the patterning of disparities in MM survival. Along these lines, our findings highlight the need for interventions to address disparities in both race/ethnicity and neighborhood SES related to MM prognosis. This analysis was conducted using data from the NCI SEER Program, which collects population-based data on cancer diagnoses, treatment, and survival from approximately 30% of the US population [29]. Although the lack of individual SES information in SEER registry data necessitated the use of area-based measures, the census tract-based SES index used in this analysis provides a valuable tool for monitoring the disparities in cancer burdens [15]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the role of SES on the neighborhood level with survival in participants with MM across race/ethnicity.

Limitations to this work include those inherent to the study of large population-based registry data, including the potential for unmeasured and residual confounding. In addition, treatment-related variables had a high percentage of missing data, and thus, we were unable to completely assess the impact of treatment on mortality [30]. We were also unable to adjust for co-morbid diagnoses, which may influence a case’s treatment course as well as their likelihood of survival following a MM diagnosis. Future studies should evaluate the roles of treatment and co-morbid diagnoses on the associations observed in our analysis since they are important predictors of cancer survival and maybe unequally distributed among SES and race/ethnic groups. While it may be tempting to interpret these results to indicate that neighborhood SES is least influential for Hispanic adults, and most influential for API MM survivors, these results should be interpreted with caution since the magnitude of the associations was not different between the race/ethnic groups. In addition, giving that we only had access to a neighborhood-level measure of SES and no individual or family indicators of SES, we are unable to distinguish between neighborhood effects and the correlation of neighborhood SES with more proximal measures of SES. It is also possible that unmeasured factors, such as being able to access health services, including factors related to language and transportation, affect MM survival in different racial/ethnic groups in ways that may be confounded with neighborhood SES in this analysis.

Conclusions

Low neighborhood SES was associated with worse MM survival across all racial/ethnic groups examined; however, the magnitude of the association may vary somewhat between racial/ethnic groups. Our findings suggest that neighborhood SES and race/ethnicity may together play important roles in the prognosis of adults diagnosed with MM and that future research investigating disparities in MM survival should consider the contextual effects of both dimensions of social identity and position. In conclusion, our findings suggest that the combined influences of SES and race/ethnicity should be considered when developing interventions to remedy disparities in MM survival.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR001454 (MME), TL1TR01454 (MACA), and F31 CA24710501A1 (MACA).

Footnotes

Code availability NA

Conflict of interest The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released June 2018, based on the November 2017 submission.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2020) Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 70(1):7–30. 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, Zeldenrust SR, Dingli D, Russell SJ, Lust JA, Greipp PR, Kyle RA, Gertz MA (2008) Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood 111(5):2516–2520. 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa LJ, Brill IK, Omel J, Godby K, Kumar SK, Brown EE (2017) Recent trends in multiple myeloma incidence and survival by age, race, and ethnicity in the United States. Blood Adv 1(4):282–287. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016002493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulte D, Redaniel MT, Brenner H, Jansen L, Jeffreys M (2014) Recent improvement in survival of patients with multiple myeloma: Variation by ethnicity. Leuk Lymphoma 55(5):1083–1089. 10.3109/10428194.2013.827188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaya H, Peressini B, Jawed I, Martincic D, Elaimy AL, Lamoreaux WT, Fairbanks RK, Weeks KA, Lee CM (2012) Impact of age, race and decade of treatment on overall survival in a critical population analysis of 40,000 multiple myeloma patients. Int J Hematol 95:64–70. 10.1007/s12185-011-0971-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ailawadhi S, Aldoss IT, Yang D, Razavi P, Cozen W, Sher T, Chanan-Khan A (2012) Outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: A SEER-based comparative analysis of ethnic subgroups. Br J Haematol 158(1):91–98. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ailawadhi S, Parikh K, Abouzaid S, Zhou Z, Tang W, Clancy Z, Cheung C, Zhou ZY, Jipan Xie J (2019) Racial disparities in treatment patterns and outcomes among patients with multiple myeloma: A SEER-Medicare analysis. Blood Adv 3(20):2986–2994. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B (2004) National research council (US) panel on race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, and health in later life. Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. National Academies Press (US), Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C (2010) Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1186:69–101. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams DR, Kontos EZ, Viswanath K, Haas JS, Lathan CS, MacConaill LE, Chen J, Ayanian JZ (2012) Integrating multiple social statuses in health disparities research: The case of lung cancer. Health Serv Res 47(3 Pt 2):1255–1277. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01404.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB (2016) Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychol 35(4):407–411. 10.1037/hea0000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowleg L (2012) The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health 102(7):1267–1273. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baris D, Brown LM, Silverman DT, Hayes R, Hoover RN, Swanson GM, Dosemeci M, Schwartz AG, Liff JM, Schoenberg JB, Pottern LM, Lubin J, Greenberg RS, Fraumeni JF Jr (2000) Socioeconomic status and multiple myeloma among US Blacks and Whites. Am J Public Health 90(8):1277–1281. 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs excluding AK (with additional treatment fields), Nov 2017 Sub (2000–2015) <Vintage 2015 Pops by Race/Origin Tract 2000/2010 Mixed Geographies> - Linked To Census Tract Attributes - Time Dependent (2000–2015) - SEER 18 (excl AK) Census 2000/2010 Geographies with Index Field Quantiles, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released June 2018, based on the November 2017 submission. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu M, Tatalovich Z, Gibson JT, Cronin KA (2014) Using a composite index of socioeconomic status to investigate health disparities while protecting the confidentiality of cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control 25(1):81–92. 10.1007/s10552-013-0310-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen BE, Kramer JL, Greene MH, Rosenberg PS (2008) Competing risks analysis of correlated failure time data. Biometrics 64(1):172–179. 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00868.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiala MA, Finney JD, Liu J, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Tomasson MH, Vij R, Wildes TM (2015) Socioeconomic status is independently associated with overall survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma 56(9):2643–2649. 10.3109/10428194.2015.1011156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abou-Jawde RM, Baz R, Walker E, Choueiri TK, Karam MA, Reed J, Faiman B, Hussein M (2006) The role of race, socioeconomic status, and distance traveled on the outcome of African-American patients with multiple myeloma. Haematologica 91(10):1410–1413. 10.3324/%x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manojlovic Z, Christofferson A, Liang WS, Aldrich J, Washington M, Wong S, Rohrer D, Jewell S, Kittles RA, Derome M, Auclair D, Craig DW, Keats J, Carpten JD (2017) Comprehensive molecular profiling of 718 Multiple Myelomas reveals significant differences in mutation frequencies between African and European descent cases. PLOS Genet. 13(11):e1007087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DR, Sternthal M (2010) Understanding Racial-ethnic Disparities in Health: Sociological Contributions. J Health Soc Behav 51(1):S15–S27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdallah SN, Rajkumar V, Greipp P, Kapoor P, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Baughn LB, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, Dingli D, Go RS, Hwa YL, Fonder A, Hobbs M, Lin Y, Leung N, Kourelis T, Warsame R, Siddiqui M, Lust J, Kyle RA, Bergsagel L, Ketterling R, Kumar SK (2020) Cytogenetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma: association with disease characteristics and treatment response. Blood Cancer J 10.1038/s41408-020-00348-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derman BA, Jasielec J, Langerman SS, Zhang W, Jakubowiak AJ, Chiu BC (2020) Racial differences in treatment and outcomes in multiple myeloma: a multiple myeloma research foundation analysis”. Blood Cancer J 10.1038/s41408-020-00347-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiala MA, Keller J, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Tomasson MH, Vij R, Wildes TM (2014) Treatment advances for multiple myeloma have disproportionally benefited patients Who are young, white, and have higher socioeconomic status. Blood 124(21):555–55524928860 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crenshaw K (1989) Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum 140:139–167 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins PH (1990) Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge, New York [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer GR (2014) Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med 110:10–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL (2019) Siegel RL (2019) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 69(5):363–385. 10.3322/caac.21565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stepanikova I, Oates GR (2017) Perceived discrimination and privilege in health care: the role of socioeconomic status and race. Am J Prev Med 52(1):S86–S94. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (2020) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gliklich R, Dreyer N, Leavy M (2014) Analysis, Interpretation, and Reporting of Registry Data To Evaluate Outcomes. In: Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB (eds) Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), Rockville, MD, pp 1–25 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released June 2018, based on the November 2017 submission.