Abstract

Objective

Exposure to the herbicide glyphosate during pregnancy and lactation may increase the risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in offspring. Recently, we reported that maternal exposure of formulated glyphosate caused ASD-like behaviors in juvenile offspring. Here, we investigated whether maternal exposure of pure glyphosate could cause ASD-like behaviors in juvenile offspring.

Methods

Water or 0.098% glyphosate was administered as drinking water from E5 to P21 (weaning). Behavioral tests such as grooming test and three-chamber social interaction test in male offspring were performed from P28 to P35.

Results

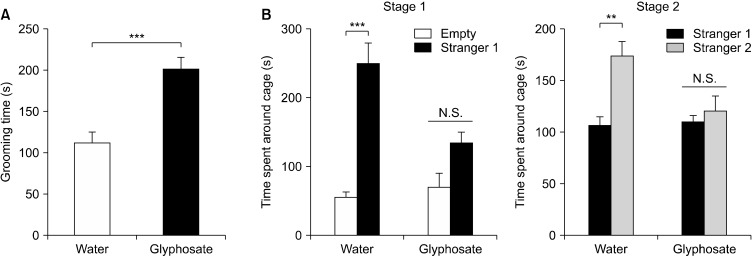

Male offspring showed ASD-like behavioral abnormalities (i.e., increasing grooming behavior and social interaction deficit) after maternal exposure of glyphosate.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that the exposure of glyphosate during pregnancy and lactation may cause ASD-like behavioral abnormalities in male juvenile offspring. It is likely that glyphosate itself, but not the other ingredients, may contribute to ASD-like behavioral abnormalities in juvenile offspring.

Keywords: Autistic disorder, Ingredient, Glyphosate, Maternal exposure, Offspring

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by repetitive and characteristic patterns of behaviors and difficulties with social communications [1,2]. However, the detailed mechanisms underlying ASD etiology remain unknown. Growing evidence support a significant interaction of genetic and environmental factors in ASD etiology [1-4]. Environmental factors, including exposures to synthetic chemicals (i.e., herbicides) during pregnancy, may play a role in the etiology of ASD [4,5].

Glyphosate [N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine], the active ingredient in RoundupⓇ and other herbicides, is the most widely used herbicide in the world since it has excellent environmental profile and low toxicity [6,7]. A population-based study in California of the United State (US) demonstrated that the risk of ASD might be associated with exposure of glyphosate during pregnancy and early childhood [8], suggesting a possible relationship between maternal glyphosate exposure and ASD in offspring [9,10]. A recent systemic review shows that glyphosate showed a “moderate level of evidence” in their association with ASD in children [11]. In a rodent study, we recently reported that maternal exposure to high dose of formulated glyphosate (RoundupⓇ Maxload) caused ASD-like behavioral abnormalities in male juvenile offspring [12]. The surfactant, polyethoxylated tallow amine, contained in the formulated glyphosate such as Roundup [13]. However, how glyphosate or other ingredients in the RoundupⓇ Maxload contribute to ASD-like behaviors in offspring is unknown.

Here, we investigated whether maternal exposure of pure glyphosate causes ASD-like behaviors in male juvenile offspring.

METHODS

Animals

Pregnant ddY mice (embryo at the 5th day [E5], 9−10 weeks old) were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). Each pregnant mouse was housed singly in clear polycarbonate cage (22.5 × 33.8 × 14.0 cm) under controlled temperatures and 12 hour light/dark cycles (lights on between 07:00−19:00 h), with ad libitum food (CE-2; CLEA Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and water. This study was approved by the Chiba University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (permission number: 30-352 and 1-135).

Treatment of Glyphosate in Drinking Water into Pregnant Mice

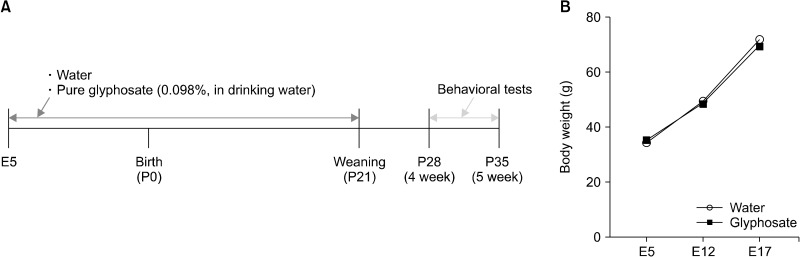

The commercially available glyphosate (Lot number: MKCK2795; Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used. Previously, we used 0.098% formulated glyphosate (expressed as 0.025% RoundupⓇ Maxload [48% (w/v) glyphosate potassium salt, 52% other ingredients such as water and surfactant])[12,14]. Therefore, pregnant mice were treated with water or 0.098% pure glyphosate from E5 to P21 (weaning) (Fig. 1A). The male offspring were isolated from their mothers at weaning (P21), and the mice were caged each three-five in the groups in clear polycarbonate cage (22.5 × 33.8 × 14.0 cm). Mice were housed under controlled temperatures and 12 hour light/dark cycles (lights on between 07:00−19:00 h), with ad libitum food and water.

Fig. 1.

Treatment schedule and body weight changes of mothers. (A) Schedule of treatment, and behavioral tests of offspring. (B) Change of body weight of pregnant mothers. Repeated measure one-way ANOVA (F1,9 = 0.246, p = 0.632). Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 5 or 6).

Behavioral Analysis

Behavioral tests of male offspring were performed from P28 to P35 (Fig. 1A). The grooming test was performed as previously described [12]. Each mouse was put in a clean standard mouse cage separately and allowed to adjust for 10 minutes. A video camera (C920r HD Pro; Logitech International SA, Tokyo, Japan) was fixed two meters in front of the cage to record the mice behavior for the next 10 minutes, following the habituation time. After the experiment, the total self-grooming time of each subject mouse was counted by an experimenter through watching these videos. A timer was prepared for scoring cumulative time spent grooming during the 10 minutes test session.

The three-chamber social interaction test was performed as reported previously [12]. The testing apparatus consisted of a clear rectangular box and a lid with a video camera. Two clear plastic dividers with a small square opening (5 × 8 cm) divided the box into three equal chambers (20 × 40 × 20 cm). Also, an empty wire cage (10 cm in diameter, 17.5 cm in height, with vertical bars 0.3 cm apart) was put in the center of each left and right chamber. First, each test mouse was placed in the chamber and allowed to explore the entire box for 10 minutes to habituate the environment. Next, a ddY male mouse (stranger 1) that never meet the test mouse before was put into a wire cage that was located into one of the side chambers. To evaluate sociability, the test mouse was allowed to explore the box for an additional 10 minutes. Last, to assess social novelty, a second stranger male mouse (stranger 2) was placed into the wire cage that had been empty during the first 10 minutes, and the test mouse was allowed another 10 minutes to interact with the strangers and to explore the box. Thus, the subject mouse had a choice between the first, non-familiar mouse (stranger 1) and the novel unfamiliar mouse (stranger 2). The time spent in each chamber and the interaction time spent around each cage was recorded on video.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism ver. 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The data of body weight changes were analyzed using the repeated measure one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc Bonferroni test. Comparisons between two groups were performed using Student ttest. The data of three-chamber social interaction test were analyzed using two-way ANOVA, followed by post-hoc Bonferroni test. The pvalues of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Behavioral Abnormalities in Juvenile Offspring after Maternal Glyphosate Exposure

There were no changes in body weight of glyphosate-treated mothers and water-treated mothers (Fig. 1B). In the grooming test, male juvenile offspring after maternal glyphosate exposure showed increased grooming time compared to the water-treated group (Fig. 2A). In the three-chamber social interaction test, male juvenile offspring after maternal glyphosate exposure showed social interaction deficits compared to the water-treated group (Fig. 2B). The data suggest that the exposure to pure glyphosate during pregnancy and lactation causes ASD-like behavioral abnormalities in male juvenile offspring.

Fig. 2.

Autism spectrum disorder-like behavioral abnormalities in male juvenile offspring. (A) Grooming test. Male juvenile offspring after maternal glyphosate exposure showed the increased grooming time compared to control group. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 8). ***p < 0.01 compared to control group (Student t test). (B) Three chamber social interaction test. Left: Two-way ANOVA (glyphosate: F1,28 = 6.929, p = 0.014; stranger: F1,28 = 46.21, p < 0.001; interaction: F1,28 = 11.89, p = 0.002). Right: Two-way ANOVA (glyphosate: F1,28 = 5.098, p = 0.032; stranger: F1,28 = 12.36, p = 0.002; interaction: F1,28 = 6.609, p = 0.016). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 8). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to control group. N.S., not significant.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the exposure to high levels (0.098%) glyphosate during pregnancy and lactation caused ASD-like behaviors in male juvenile offspring. These findings are consistent with previous report [12] using formulated glyphosate (0.098%). Previously, we used the commercially available RoundupⓇ Maxload, although the detailed information of surfactant was not disclosed. The current data using pure glyphosate (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) are similar to the results of the previous report using RoundupⓇ Maxload [12]. Collectively, it is likely that glyphosate itself, but not ingredient, might contribute to ASD-like behavioral abnormalities in offspring after maternal exposure.

In this study, we did not find the body weight changes between two groups, inconsistent with the previous data using formulated glyphosate [12]. Thus, it is likely that the ingredients in the RoundupⓇ Maxload contribute to decreased body weight of pregnant mice after formulated glyphosate exposure. In addition, the reduction of body weight of pregnant mice might not contribute to ASD-like behaviors in male offspring after maternal glyphosate exposure.

Maternal exposure to 0.098% glyphosate might cause ASD-like behaviors in juvenile offspring, although it is exceptionally unlikely that such exposure could be reached during human pregnancy [12,15]. A prospective birth cohort study in Central Indiana of US demonstrated that > 90% of pregnant women had detectable levels of glyphosate (0.1 mg/L) in the urine [16]. Furthermore, higher urine levels of glyphosate were significantly correlated with shortened pregnancy lengths (r = −0.28, p = 0.02) [16]. A recent review shows the detection of urine levels of glyphosate in individuals exposed occupationally, para-occupationally, or environmentally to the herbicide [17]. There-fore, it is of great interest to investigate a cohort study on measurement of blood (or urine) levels of glyphosate and its metabolite aminomethylphosphonic acid in pregnant mothers who have their offspring with or without ASD.

This paper has limitation. In this study, we used male offspring after maternal glyphosate exposure since the prevalence of ASD in male subjects is higher than that in female subjects [18]. Nonetheless, it is also of interest to examine whether maternal glyphosate exposure could cause ASD-like phenotypes in female offspring.

In conclusion, this study suggests that the exposure to pure glyphosate during pregnancy and lactation might play a role in the etiology of ASD-like behaviors in male juvenile offspring. Therefore, it is likely that glyphosate itself, but not the other ingredients, may contribute to ASD-like behavioral abnormalities in male juvenile offspring although further detailed study is needed.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (to K.H., 17H04243), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) River Award R35 ES030443-01 (to B.D.H.), NIEHS Superfund Program P42 ES004699 (to B.D.H.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Yaoyu Pu, Bruce D. Hammock, Kenji Hashimoto. Data acquisition: Yaoyu Pu, Li Ma, Jiajing Shan, Xiayuan Wan. Formal analysis: Yaoyu Pu, Li Ma, Jiajing Shan, Xiayuan Wan. Supervision: Kenji Hashimoto. Writing−original draft: Yaoyu Pu, Kenji Hashimoto. Writing−review & editing: Yaoyu Pu, Bruce D. Hammock, Kenji Hashimoto.

References

- 1.Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Baron-Cohen S. Autism. Lancet. 2014;383:896–910. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet. 2018;392:508–520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, Phillips J, Cohen B, Torigoe T, et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sealey LA, Hughes BW, Sriskanda AN, Guest JR, Gibson AD, Johnson-Williams L, et al. Environmental factors in the development of autism spectrum disorders. Environ Int. 2016;88:288–298. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JY, Son MJ, Son CY, Radua J, Eisenhut M, Gressier F, et al. Environmental risk factors and biomarkers for autism spectrum disorder: an umbrella review of the evidence. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:590–600. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradberry SM, Proudfoot AT, Vale JA. Glyphosate poisoning. Toxicol Rev. 2004;23:159–167. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200423030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kier LD, Kirkland DJ. Review of genotoxicity studies of glyphosate and glyphosate-based formulations. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2013;43:283–315. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2013.770820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Ehrenstein OS, Ling C, Cui X, Cockburn M, Park AS, Yu F, et al. Prenatal and infant exposure to ambient pesticides and autism spectrum disorder in children: population based case- control study. BMJ. 2019;364:l962. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakian AV, VanDerslice JA. Pesticides and autism. BMJ. 2019;364:l1149. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rueda-Ruzafa L, Cruz F, Roman P, Cardona D. Gut microbiota and neurological effects of glyphosate. Neurotoxicology. 2019;75:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ongono JS, Béranger R, Baghdadli A, Mortamais M. Pesticides used in Europe and autism spectrum disorder risk: can novel exposure hypotheses be formulated beyond organophos-phates, organochlorines, pyrethroids and carbamates? - a systematic review. Environ Res. 2020;187:109646. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pu Y, Yang J, Chang L, Qu Y, Wang S, Zhang K, et al. Maternal glyphosate exposure causes autism-like behaviors in offspring through increased expression of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:11753–11759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922287117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meftaul IM, Venkateswarlu K, Dharmarajan R, Annamalai P, Asaduzzaman M, Parven A, et al. Controversies over human health and ecological impacts of glyphosate: is it to be banned in modern agriculture? Environ Pollut. 2020;263(Pt A):114372. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pu Y, Chang L, Qu Y, Wang S, Tan Y, Wang X, et al. Glyphosate exposure exacerbates the dopaminergic neurotoxicity in the mouse brain after repeated administration of MPTP. Neurosci Lett. 2020;730:135032. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomon KR. Estimated exposure to glyphosate in humans via environmental, occupational, and dietary pathways: an updated review of the scientific literature. Pest Manag Sci. 2019;76:2878–2885. doi: 10.1002/ps.5717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parvez S, Gerona RR, Proctor C, Friesen M, Ashby JL, Reiter JL, et al. Glyphosate exposure in pregnancy and shortened gestational length: a prospective Indiana birth cohort study. Environ Health. 2018;17:23. doi: 10.1186/s12940-018-0367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillezeau C, van Gerwen M, Shaffer RM, Rana I, Zhang L, Sheppard L, et al. The evidence of human exposure to glyphosate: a review. Environ Health. 2019;18:2. doi: 10.1186/s12940-018-0435-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werling DM, Geschwind DH. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2013;26:146–153. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32835ee548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]