Abstract

Background:

Despite advances in the first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), effective options are needed to address disease progression during or following treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Thus, we aimed to evaluate lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in these patients.

Methods:

We report results of the mRCC cohort from an open-label phase 1b/2 study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients at least 18 years old with selected solid tumors and an ECOG PS of 0–1. Oral lenvatinib 20 mg was given daily along with intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg once every three weeks. Efficacy was analyzed in patients with clear cell mRCC receiving study drug by prior therapy grouping: treatment-naïve, previously treated ICI-naïve, and ICI-pretreated patients. Safety was analyzed in all patients. The primary endpoint was objective response rate at week 24 (ORRwk24) per immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (irRECIST) by investigator assessment. Tumor assessments occurred every six weeks until week 24, then every nine weeks. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov(NCT02501096); the final analysis is reported here.

Findings:

The study enrolled 145 patients (efficacy analysis, n=143; safety analysis, n=145) from July 21, 2015-October 16, 2019; median follow-up was 19·8 months (interquartile range: 14·3–28·4). The ORRwk24 by irRECIST was 72·7% (95% CI 49·8–89·3) for treatment-naïve patients (16/22), 41·2% (95% CI 18·4–67·1) for previously treated ICI-naïve patients (7/ 17), and 55·8% (95% CI 45·7–65·5) for ICI-pretreated patients (58/104). The most common grade 3 treatment-related adverse event (AE) was hypertension (treatment-naïve: 23%, 5/22; previously treated ICI-naïve: 18%, 3/17; ICI-pretreated: 21%, 22/104). Treatment-related serious AEs occurred in 36 patients; three had treatment-related deaths (gastrointestinal hemorrhage, sudden death, and pneumonia).

Interpretation:

Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab showed encouraging antitumor activity and a manageable safety profile and may be an option for post-ICI treatment of mRCC.

Funding:

Eisai Inc.; Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 70–75% of patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) have clear cell RCC.1,2 Until recently, monotherapy with sunitinib or pazopanib comprised standard first-line therapies for metastatic clear cell RCC.1,3 Patients progressing on these agents were treated sequentially with targeted therapies including cabozantinib monotherapy, nivolumab monotherapy, axitinib monotherapy, or lenvatinib-plus-everolimus combination therapy.3 Recently, phase 3 trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in combination with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; pembrolizumab in combination with lenvatinib; pembrolizumab or avelumab in combination with axitinib; cabozantinib in combination with nivolumab), and dual ICI-combination therapy (ie, nivolumab plus ipilimumab) have shown superior outcomes to single-agent sunitinib as first-line therapy for patients with advanced/metastatic clear cell RCC.4–9 As such, ICI-based regimens are now standard first-line therapy.3 However, there is a need to re-evaluate the efficacy of subsequent treatment options in patients previously treated with ICI therapy.

The combination of lenvatinib with pembrolizumab is of specific interest as each monotherapy has shown efficacy in patients with advanced RCC: pembrolizumab has shown an objective response rate (ORR) of 36·4%10 and lenvatinib achieved an ORR of 27%.11 Additionally, preclinical studies have demonstrated that lenvatinib plus an anti-programmed cell death receptor (PD)-1 inhibitor resulted in enhanced antitumor activity greater than that observed with either agent alone,12,13 and that lenvatinib improved survival when administered with sensitized lymphocytes.14 Lenvatinib is a multitargeted TKI of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors 1–3, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors 1–4, platelet-derived growth factor receptor α, RET, and KIT.15 The potent activity against FGF receptors 1–4 is a unique characteristic of lenvatinib compared with sorafenib, axitinib, cabozantinib, and sunitinib.16,17 Additionally, studies of murine tumor isograft models have demonstrated the immunomodulatory activity of lenvatinib in the tumor microenvironment; decreases in immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages, activated cytotoxic T cell increases, and activation of interferon gamma signaling were observed.12,13

A phase 1b/2 multicenter, open-label, clinical study (Study 111/KEYNOTE-146) assessed lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with selected advanced solid tumors.18 The first interim report of this study (all cohorts, n=137), which included 30 ICI-naïve patients with metastatic RCC, determined the recommended phase 2 dose of the study drugs to be lenvatinib 20 mg orally once daily plus pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously every three weeks.18 Ten patients with various tumor types were treated with this regimen in the phase 1 dose-finding portion; none had dose-limiting toxicities.18 Of note, the initial 30 patients with ICI-naïve metastatic RCC had an ORR at week 24 (ORRwk24) of 63% by investigator review using immune-related (ir) Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST).

Herein, we report results from 145 patients with metastatic RCC who were enrolled in Study 111/KEYNOTE-146.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Study 111/KEYNOTE-146 is an open-label, single-arm, phase 1b/2 study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with selected solid tumors. This study was conducted at 27 sites in the United States and Europe (appendix p12). Data from patients with RCC who participated in the phase 1b dose-finding portion or the phase 2 and expansion parts and received the recommended phase 2 dose of the study drugs are reported.

Eligible patients were at least 18 years old, had metastatic RCC (specified as “predominantly clear cell” by a protocol amendment on March 30, 2016, shortly following the phase 1b dose-finding portion of this study) with measurable disease defined by irRECIST,19 irrespective of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) status. Eligible patients also had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1 and an estimated life expectancy of ≥12 weeks. Initially, patients with up to two prior lines of systemic therapy were eligible. Later amendments (on July 31, 2018, and April 19, 2019) required patients to have had disease progression with an anti-programmed cell death receptor-1 (PD-1)/PD-L1-based regimen. Additional criteria are available in the appendix (p1).

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice (defined by the International Council on Harmonization) and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review boards or ethics committees approved the protocol at each participating center and all patients provided written informed consent.

The three patient groups comprised treatment-naïve patients, patients previously treated without an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy (defined herein as ‘previously treated ICI-naïve’), and patients previously treated with at least one prior anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy (defined herein as ‘ICI-pretreated’).

Procedures

All patients were treated with lenvatinib 20 mg orally once daily plus pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously once every 3 weeks. Patients remained on study-drug treatment until disease progression, development of unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. Patients who discontinued pembrolizumab after a maximum of 35 treatments could continue lenvatinib; procedures regarding dose delays and reductions are available in the appendix (p1–2).

Tumor assessments were based on computerized tomography/magnetic resonance imaging scans of chest, abdomen, pelvis, and of other known sites of disease. Imaging scans were obtained at screening (within 28 days prior to cycle 1/day 1), and every six weeks until week 24, then every nine weeks thereafter; and as clinically necessary. All tumor assessment time points were assessed by both investigator assessment and independent review committee (IRC).

Adverse events (AEs) were monitored and recorded using the Common Terminology Criteria for AEs version 4·03. Patients were also monitored via regular performance of physical examinations and laboratory evaluation for hematology, blood chemistry, and urine values every three weeks (more frequently as clinically indicated for patients with hypertension or proteinuria); as well as periodic measurement of vital signs and electrocardiograms. The presence of AEs was continually assessed during the study and recorded for 30 days after the last dose of study treatment.

Outcomes

The primary study endpoint was the ORR at week 24 (ORRwk24) per irRECIST, by investigator assessment. ORRwk24 was defined as the proportion of patients who had a best overall response of confirmed complete response (CR) or confirmed partial response (PR) as of the week 24 tumor assessment time point. Week 24 was chosen as a reasonable “early” timepoint in the phase 2 part of the study to assess efficacy in patients with a variety of tumor types and, hence, to determine which cohorts should be expanded. The secondary study endpoints included ORR, duration of response (DOR), disease control rate (DCR), clinical benefit rate (CBR which included durable stable disease rate), and progression-free survival (PFS) assessed by the investigator per irRECIST, as well as overall survival (OS) and safety and tolerability. An additional secondary endpoint was pharmacokinetics, which will be reported later. Exploratory endpoints included tumor responses per irRECIST and RECIST version (v)1·1 assessed by IRC.

Statistical Analysis

The phase 1b analysis has been previously reported.18 The RCC cohort size in phase 2 was expanded to approximately 145 patients to allow evaluation of approximately 100 patients in the RCC cohort who had received prior anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment. To determine the sample size, two-sided 95% confidence intervals were calculated for a range of observed ORRs from 25% to 45% in patients previously treated with an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy with a sample size of 100 patients. If the observed ORR is 35%, the sample size of 100 patients provides a 95% confidence interval with a lower bound excluding 25%, indicating with 95% confidence that the ORR in the combination of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab is greater than 25%. A corresponding table and details on the cohort expansion are available in the appendix (p1). The primary efficacy analysis for the RCC cohort was conducted when enrolled patients with clear cell RCC had either completed eight cycles (24 weeks) of treatment or discontinued treatment. Enrolled patients with non-clear cell RCC were excluded from this efficacy analysis. The data cutoff date was determined to provide a sufficient follow-up period, which included a median follow-up of ≥12 months in all patients and approximately six months of follow-up in responders following initial objective response. Safety analyses were performed on all enrolled patients who received study drug. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS/Stat version 14·1. Patients without an evaluable tumor assessment were included in the denominator for the calculation of ORR. The exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for ORRwk24, ORR, DCR, and CBR were calculated with the Clopper-Pearson method. Median PFS, OS, and DOR were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and 95% CIs were calculated with a generalized Brookmeyer-Crowley method. The median and 95% CI from post-hoc analyses of time to response and follow-up time for OS were calculated similarly.

The ICI-pretreated group was further assessed according to three subgroups defined by prior ICI therapy: nivolumab plus ipilimumab; anti-VEGF therapy in combination with an ICI; ICI monotherapies (most commonly, nivolumab) or other ICI-combination therapies (this subgroup is labeled as “ICI with or without other”). Subgroup analyses were also performed among patients who received prior anti-VEGF therapy in combination, regardless if it was given with an ICI in combination or given sequentially.

This study is registered with www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02501096) and with www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu (EudraCT:2017–000300-26).

Role of the funding source

This study was funded by Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Both sponsors offered input towards the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. The authors had full access to the data and control of the final approval and decision to submit the manuscript.

Results

This study enrolled 145 patients in the RCC cohort from July 21, 2015 to October 16, 2019; overall, 143 patients had clear cell RCC, two patients enrolled with non-clear cell RCC (one prior to a protocol amendment on March 30, 2016 limiting enrollment to patients with clear cell RCC and the second as a protocol deviation; appendix p11). The two patients with non-clear cell RCC received treatment and were included in the overall population for safety; however, they were not analyzed for efficacy, which was based on clear cell histology.

Among enrolled patients with clear cell RCC, there were 22 patients in the treatment-naïve group, 17 patients in the previously-treated ICI-naïve group (16 patients had prior anti-VEGF therapy; one patient was retrospectively found to have been treated for another malignancy, but was treatment-naïve for RCC), and 104 patients in the ICI-pretreated (ie, anti-PD-1/PD-L1) group. The 104 ICI-pretreated patients received two or more doses of an ICI and progressed on or after treatment with an ICI. Of the 104 patients, 96 (92·3%) had an ICI (anti-PD-1/PD-L1) as their most recent therapy; median duration of treatment with prior ICI therapy was 6·8 months (interquartile range [IQR]: 3·1–13·2) and the median time from the end of their most recent ICI regimen to first dose was 1·6 months (IQR: 1·2–2·2). Almost all (100/104) patients had a second scan during or following treatment with an ICI-based therapy that confirmed radiographic progression before initiation of treatment with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab. While the groups were generally similar in baseline characteristics, a greater proportion of ICI-pretreated patients had two or more metastatic sites compared with the other groups. Moreover, ICI-pretreated patients had more bone metastases. Greater proportions of treatment-naïve and ICI-naïve patients had favorable risk disease. Patient demographic and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

| Treatment-naïvea (n=22) | Previously treated ICI-naïveb (n=17) | ICI-pretreatedc (n=104) | All patientsd (N=145) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (IQR) | 55 (49–68) | 66 (60–68) | 60 (54–67) | 60 (52–68) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 18 (82) | 13 (76) | 80 (77) | 113 (78) |

| Female | 4 (18) | 4 (24) | 24 (23) | 32 (22) |

| Prior nephrectomy, n (%) | 18 (82) | 17 (100) | 79 (76) | 115 (79) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 13 (59) | 13 (76) | 47 (45) | 74 (51) |

| 1 | 9 (41) | 4 (24) | 57 (55) | 71 (49) |

| MSKCC risk groupe, n (%) | ||||

| Favorable | 9 (41) | 9 (53) | 37 (36) | 56 (39) |

| Intermediate | 10 (45) | 6 (35) | 44 (42) | 60 (41) |

| Poor | 3 (14) | 2 (12) | 23 (22) | 29 (20) |

| IMDC risk group, n (%) | ||||

| Favorable | 9 (41) | 5 (29) | 18 (17) | 32 (22) |

| Intermediate | 10 (45) | 10 (59) | 61 (59) | 83 (57) |

| Poor | 3 (14) | 2 (12) | 25 (24) | 30 (21) |

| PD-L1 statusf, n (%) | ||||

| Positive | 12 (55) | 7 (41) | 46 (44) | 66 (46) |

| Negative | 9 (41) | 8 (47) | 45 (43) | 62 (43) |

| Not available | 1 (5) | 2 (12) | 13 (13) | 17 (12) |

| Number of metastatic sites, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| 1 | 11 (50) | 7 (41) | 18 (17) | 36 (25) |

| ≥ 2 | 11 (50) | 9 (53) | 85 (82) | 107 (74) |

| Metastatic sites, n (%) | ||||

| Lung | 16 (73) | 14 (82) | 62 (60) | 93 (64) |

| Liver | 2 (9) | 3 (18) | 25 (24) | 31 (21) |

| Bone | 3 (14) | 2 (12) | 32 (31) | 39 (27) |

| Brain | 0 | 1 (6) | 8 (8) | 9 (6) |

| Number of prior anticancer regimens, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 22 (100) | 0 | 0 | 23 (16) |

| 1 | NA | 11 (65) | 41 (39) | 52 (36) |

| 2 | NA | 6 (35)g | 63 (61)h | 70 (48) |

| Number of prior anti-VEGF therapies, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | NA | 10 (59) | 60 (58) | 70 (48) |

| 2i | NA | 6 (35) | 7 (8) | 15 (10) |

| Prior anti-VEGF, n (%)j | NA | 16 (94) | 68 (65) | 85 (59) |

| Sunitinib | NA | 9 (53) | 23 (22) | 32 (22) |

| Pazopanib | NA | 8 (47) | 25 (24) | 33 (23) |

| Axitinib | NA | 4 (24) | 11 (11) | 16 (11) |

| Cabozantinib | NA | 1 (6) | 10 (10) | 12 (8) |

| Otherk | NA | 1 (6) | 7 (7) | 8 (6) |

Treatment-naïve patients received the study drugs as their first-line therapy; excludes one patient with non-clear cell RCC.

Previously treated ICI-naïve group consists of patients with one or more prior lines of therapy that do not include PD-1/PD-L1 ICIs; one patient was retrospectively found to be treatment-naïve for RCC.

ICI-pretreated group consists of patients with one or more prior lines of therapy that includes PD-1/PD-L1 ICIs; Progression was required to be confirmed no less than four weeks after initial assessment in the absence of rapid clinical progression; all patients were to have received at least two doses of an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibody; excludes one patient with non-clear cell RCC.

Two patients with non-clear cell RCC (treatment-naïve, n=1; ICI-pretreated, n=1) were included in the “All patients” population, but not in individual groups.

MSKCC risk group was defined based on five-factor criteria for treatment-naïve patients and based on three-factor criteria for patients previously treated.

PD-L1 expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry, in tumor tissue samples, using DAKO PD-L1 22C3 PharmDx assay. PD-L1 positivity was defined as a combined positive score of 1 or more.

Three patients in the ICI-naïve group had received three prior lines of anticancer therapy.

One patient in the ICI-pretreated group had received two prior lines of ICI therapy.

Two patients (previously treated ICI-naïve, n=1; ICI-pretreated, n=1) had received three prior anti-VEGF-therapies.

Patients could have received more than one prior anti-VEGF therapy.

“Other” includes five patients who received bevacizumab, two patients who received sitravatinib, and one patient who received sorafenib.

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IMDC, International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database; IQR, interquartile range; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; NA, not applicable; PD-1, programmed cell death receptor-1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

At the data cutoff date (August 18, 2020), 92 patients remained in study follow-up (58 patients continued receiving study treatment); 44 patients had died, eight had withdrawn consent (five withdrew from survival follow-up; three withdrew from treatment), and one patient had been lost to follow-up. The median follow-up time among the overall population was 19·8 months (IQR: 14·3−28·4). The most common therapies received among patients who discontinued study drug were cabozantinib (25/87; 29%), axitinib (8/87; 9%), and nivolumab (8/87; 9%; appendix p3).

The primary endpoint—ORRwk24 by investigator assessment per irRECIST—was 72·7% (16/22; 95% CI 49·8–89·3) for treatment-naïve patients, 41·2% (7/17; 95% CI 18·4–67·1) for previously treated ICI-naïve patients, and 55·8% (58/104; 95% CI 45·7–65·5) for ICI-pretreated patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy Responses by Investigator Assessment per irRECIST

| Tumor response at week 24 | Lenvatinib 20 mg + pembrolizumab 200 mg | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment-naïvea (n=22) | Previously treated ICI-naïveb (n=17) | ICI-pretreatedc (n=104) | |

| ORRweek24, n (%) | 16 (72·7) | 7 (41·2) | 58 (55·8) |

| (95% CI) | (49·8–89·3) | (18·4–67·1) | (45·7–65·5) |

| Overall tumor response | |||

| BOR, n (%) | |||

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 17 (77·3) | 9 (52·9) | 65 (62·5) |

| SD | 5 (22·7) | 7 (41·2) | 31 (29·8) |

| PD | 0 | 1 (5·9) | 4 (3·8) |

| NE | 0 | 0 | 4 (3·8) |

| ORR, n (%)d | 17 (77·3) | 9 (52·9) | 65 (62·5) |

| (95% CI)e | (54·6–92·2) | (27·8–77·0) | (52·5–71·8) |

| mDOR, monthsf | 24·2 | 9·0 | 12·5 |

| (95% CI) | (10·3–37·7) | (3·5-NR) | (9·1–17·5) |

| DCR, n (%)g | 22 (100) | 16 (94·1) | 96 (92·3) |

| (95% CI)e | (84·6–100·0) | (71·3–99·9) | (85·4–96·6) |

| CBR, n (%)h | 20 (90·9) | 13 (76·5) | 81 (77·9) |

| (95% CI)e | (70·8–98·9) | (50·1–93·2) | (68·7–85·4) |

| mTTR, monthsf | 1·4 | 2·8 | 2·7 |

| (95% CI) | (1·3–2·6) | (1·2–7·4) | (1·5–3·1) |

Treatment-naïve patients received the study drugs as their first-line therapy; excludes one patient with non-clear cell RCC.

Previously treated ICI-naïve group consists of patients with one or more prior lines of therapy that do not include PD-1/ PD-L1 ICIs.

ICI-pretreated group consists of patients with one or more prior lines of therapy that includes PD-1/PD-L1 ICIs; Progression was required to be confirmed at least four weeks after initial assessment in the absence of rapid clinical progression; all patients were to have received at least two doses of an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibody; excludes one patient with non-clear cell RCC.

ORR is equal to the proportion of patients with a CR + PR; the percentages are calculated based on the total number of patients in the relevant column.

95% confidence interval was calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method.

Median DOR and median TTR for responders were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the 95% CI was constructed using a generalized Brookmeyer-Crowley method.

DCR is the proportion of patients with a CR + PR + SD for at least 5 weeks.

CBR is equal to the proportion of patients with a CR + PR + Durable SD for at least 23 weeks.

BOR, best overall response; CBR, clinical benefit rate; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; CBR, clinical benefit rate; DCR, disease control rate; DOR, duration of response; IQR, interquartile range; irRECIST, immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; m, median; NE, not evaluable; NR, not reached; ORR, objective response rate; PD, progressive disease; PD-1, programmed cell death receptor-1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; PR, partial response; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; SD, stable disease; TTR, time to response.

The overall ORR by investigator assessment per irRECIST was 77·3% (17/22; 95% CI 54·6–92·2) for treatment-naïve patients, 52·9% (9/17; 95% CI 27·8–77·0) for previously treated ICI-naïve patients, and 62·5% (65/104; 95% CI 52·5–71·8) for ICI-pretreated patients; the median DOR was 24·2 months (95% CI 10·3–37·7), 9·0 months (95% CI 3·5-not reached [NR]), and 12·5 months (95% CI 9·1–17·5), respectively (Table 2). ORR by investigator assessment per irRECIST was comparable to results by IRC per RECIST v1·1 for the groups (81·8% [18/22; 95% CI 59·7–94·8]; 47·1% [8/17; 95% CI 23·0–72·2]; 55·8% [58/104; 95% CI 45·7–65·5], respectively), but variation in DOR was seen (18·3 months [95% CI 6·9–35·1], 18·8 months [95% CI 6·9-NR], and 10·6 months [95% CI 8·2–16·6], respectively; appendix p3–4).

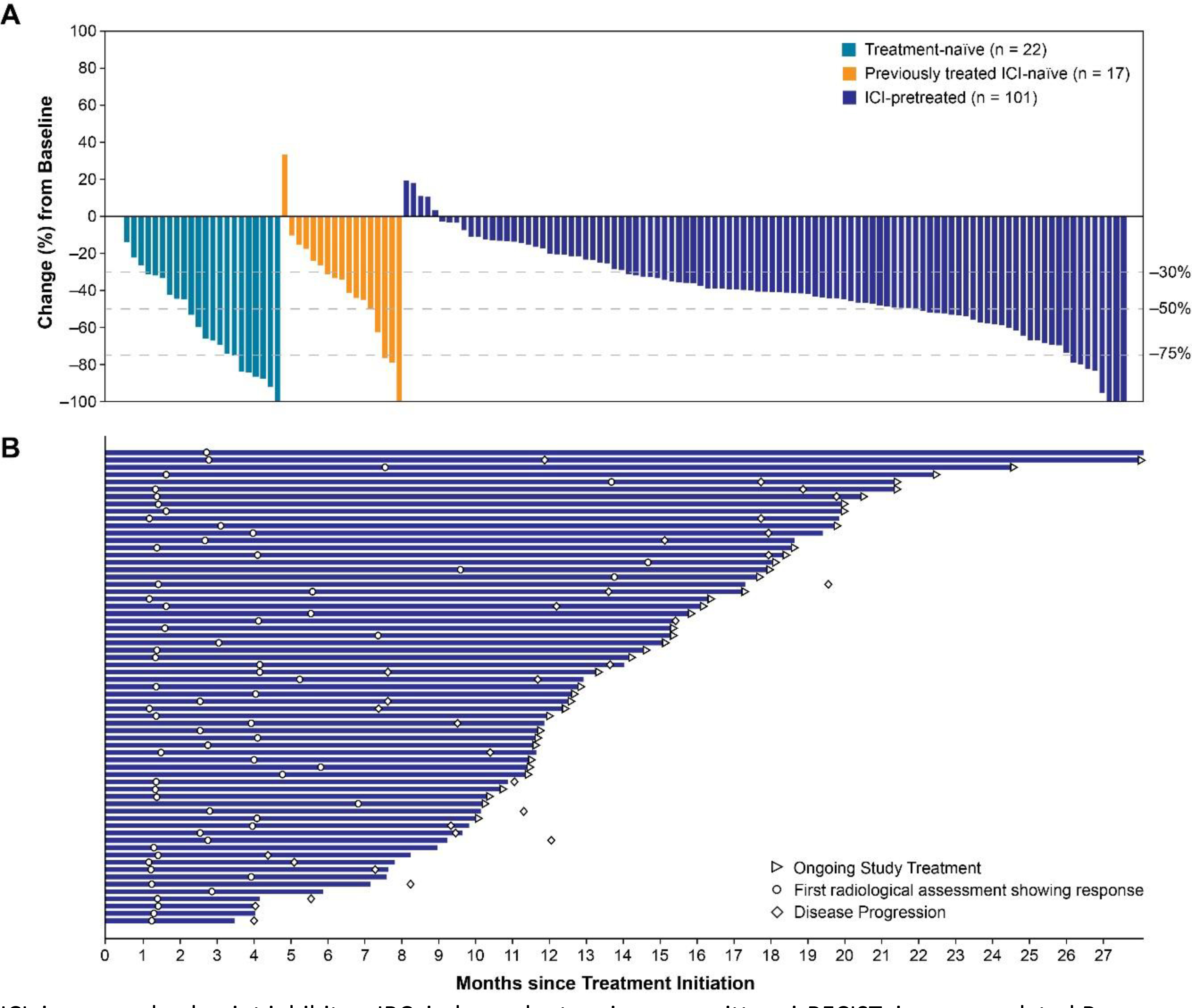

Most patients (irrespective of previous treatment) had a decrease in tumor size and at least one-quarter of each group had a maximum decrease in tumor size of ≥50% by investigator assessment per irRECIST (Figure 1). Particularly, one patient each in the treatment-naïve and ICI-naïve groups, and three patients in the ICI-pretreated group, had a 100% reduction in target lesions.

Figure 1.

Percentage Change in Sums of Diameters of Target Lesions From Baseline to Nadir (A) and Treatment Durations in ICI-Pretreated Patients Achieving an Objective Response (B) by Investigator Assessment per irRECIST

ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IRC, independent review committee; irRECIST, immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; n, number of patients who had baseline target lesion measurement and at least one postbaseline target lesion measurement by investigator assessment per irRECIST.

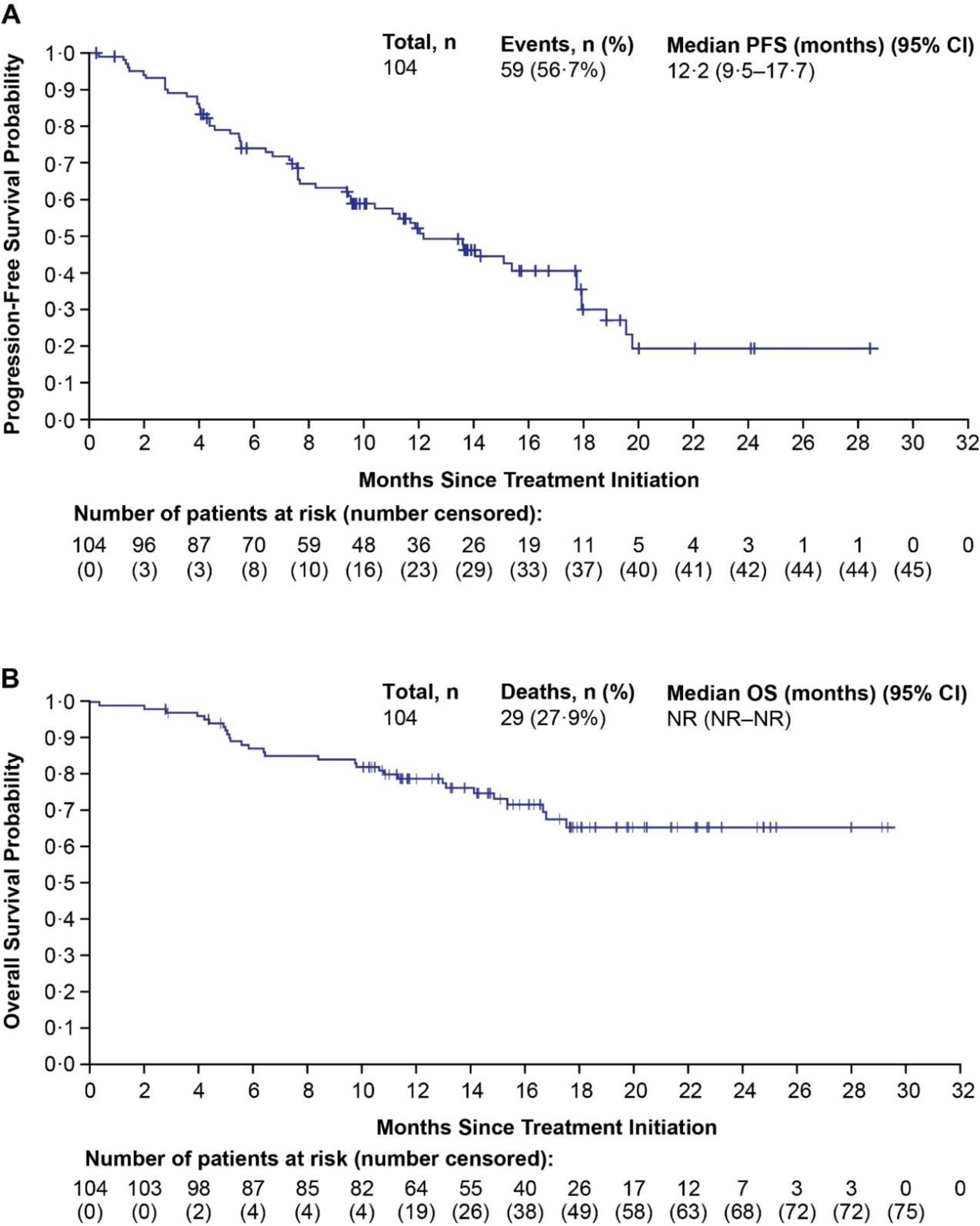

The median PFS by investigator assessment per irRECIST was 24·1 months (95% CI 11·7–31·7) for treatment-naïve patients and 11·8 months (95% CI 5·5–21·9) for previously treated ICI-naïve patients. Among ICI-pretreated patients, median PFS was comparable regardless of analysis (Figure 2A; appendix p4,11). The median OS was not reached in treatment-naïve patients (median follow-up: 29·5 months; IQR 26·4–53·1) and was 30·3 months (95% CI 28·7-not estimable; median follow-up: 50·8 months; IQR 49·2–52·5) in previously treated ICI-naïve patients. In ICI-pretreated patients, median OS was not reached (Figure 2B), and the median follow-up for OS was 16·6 months (IQR 12·8–20·0).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Estimates of PFS by Investigator Assessment per irRECIST for ICI-Pretreated Patients (A)a and OS for ICI-Pretreated Patients (B)b

aFor PFS, if patients had not experienced disease progression or death, their data was censored at the date of the last available tumor assessment.

bFor OS, patients who were lost to follow-up or who were alive at the date of data cutoff were censored at the date the patient was last known alive.

CI, confidence interval; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; irRECIST, immune Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

The ICI-pretreated group consisted of 39 patients who had previously received nivolumab plus ipilimumab, 18 patients who received anti-VEGF therapy in combination with ICI therapy, and 47 patients who received an ICI with or without other treatment. The ORR was 61·5% (24/39; 95% CI 44·6–76·6) in the nivolumab plus ipilimumab subgroup, 38·9% (7/18; 95% CI 17·3-─64·3) in the anti-VEGF in combination with ICI subgroup, and 57·4% (27/47; 95% CI 42·2–71·7) in the ICI with or without other treatment subgroup by IRC per RECIST v1·1; the median DOR ranged from 10·2 to 13·9 months across these subgroups (appendix p4). Median PFS was 11·1 months (95% CI 6·4-NR) in the nivolumab plus ipilimumab, 9·7 months (95% CI 4·0–15·8) in the anti-VEGF in combination with ICI subgroup, and 10·8 months (95% CI 7·8–17·7) in the ICI with or without other treatment subgroup (appendix p4). Additionally, analyses of OS at 15 months demonstrated OS rates of 63·6% (95% CI 44·9–77·4), 76·0% (95% CI 48·0–90·3), and 81·0% (95% CI 65·3–90·1) in the nivolumab plus ipilimumab, anti-VEGF in combination with ICI, and ICI with or without other treatment subgroups, respectively.

In total, the ICI-pretreated group included 68 patients who received anti-VEGF therapy (either in combination with an ICI [n=18] or sequentially [n=50]). The ORR for these patients was 52·9% (36/68; 95% CI 40·4–65·2) by IRC per RECIST v1·1. The median DOR was 10·6 months (95% CI 7·4–14·0) by IRC per RECIST v1·1.

Most (99%; 144/145) patients in this study experienced at least one treatment-related AE, and 57% (82/145) and 7% (10/145) of patients had grade 3 and 4 treatment-related AEs, respectively (Table 3). The most common treatment-related AEs were fatigue, diarrhea, and hypertension. The most common grade 3 treatment-related AE was hypertension (treatment-naïve: 23%, 5/22; previously treated ICI-naïve: 18%, 3/17; ICI-pretreated: 21%, 22/104; appendix p5). Similar AEs (both in number and preferred term) occurred among all patients and in the ICI-pretreated group of patients. Overall, 25% (36/145 of patients had treatment-related serious AEs (appendix p8) and there were three treatment-related deaths: one treatment-naïve patient had grade 5 pneumonia, and among the ICI-pretreated group, one patient had a grade 5 gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and another experienced sudden death (not otherwise specified) (Table 3). Rates of immune-mediated AEs were comparable between the ICI-pretreated group (42%; 44/104) and all patients (54%; 78/145). Hypothyroidism, the most common immune-mediated AE (Table 4), was somewhat less prevalent in the ICI-pretreated group (30%; 31/104) compared to all patients (40%; 58/145). The proportion of patients whose immune-mediated AE had been treated with high-dose steroids (≥40 mg prednisone or equivalent) was 6% (6/104) in the ICI-pretreated population and 8% (12/145) in all patients.

Table 3.

Treatment-related AEs (>10%) and All Treatment-related AEs of Grade ≥3 Severity for ICI-Pretreated Patients and All Patients

| Preferred Term, n (%) | ICI-pretreateda (n=104) | All patientsb (N=145) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1–2 | Grade3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5c | |

| Patients with any related TEAEsd | 37 (36) | 59 (57) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 49 (34) | 82 (57) | 10 (7) | 3 (2) |

| Fatigue | 53 (51) | 6 (6) | 0 | 0 | 77 (53) | 8 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 43 (41) | 8 (8) | 0 | 0 | 70 (48) | 10 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphonia | 38 (37) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 (34) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 35 (34) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54 (37) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 34 (33) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 50 (34) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 32 (31) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 47 (32) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 30 (29) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 46 (32) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Proteinuria | 29 (28) | 10 (10) | 0 | 0 | 43 (30) | 13 (9) | 0 | 0 |

| PPES | 28 (27) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 42 (29) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypothyroidisme | 26 (25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51 (35) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 24 (23) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 (19) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Weight decreased | 20 (19) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 28 (19) | 5 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 18 (17) | 22 (21) | 0 | 0 | 28 (19) | 30 (21) | 0 | 0 |

| Cough | 18 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 (18) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 18 (17) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 22 (15) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 17 (16) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 23 (16) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Rash, maculopapular | 16 (15) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 20 (14) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 14 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 (14) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 14 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blood creatinine increased | 13 (13) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 14 (10) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Dry skin | 13 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 13 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 13 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 13 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ALT increased | 12 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 14 (10) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| AST increased | 12 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 13 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 12 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 11 (11) | 5 (5) | 0 | 0 | 13 (9) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Blood TSH increased | 11 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhinorrhea | 10 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Edema, peripheral | 10 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 10 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 9 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 14 (10) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Rash | 9 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 8 (8) | 9 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 | 9 (6) | 12 (8) | 4 (3) | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 8 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Amylase increased | 8 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (7) | 4 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 7 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Epistaxis | 6 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 6 (4) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Adrenal insufficiencye | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 7 (5) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Blood cholesterol increased | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperkalemia | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Dehydration | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1)f |

| Colitise | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Diverticulitis | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Muscular weakness | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Glycosuria | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Rash, pustular | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Arthritis | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Abscess limb | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Cachexia | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Chondrocalcinosis pyrophosphate | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Dermatitis bullous | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Embolism, arterial | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Encephalopathy | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| INR increased | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Immune-mediated hepatitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Large intestine perforation | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Systolic hypertension | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Upper GI hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1)g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Sudden death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1)h | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Pharyngeal inflammation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Immune-mediated enterocolitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Anal fistula | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Intracardiac thrombus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Myositise | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

ICI-pretreated group consists of patients with one or more prior lines of therapy that includes PD-1/PD-L1 ICIs; progression was required to be confirmed at least four weeks after initial assessment in the absence of rapid clinical progression; all patients were to have received at least two doses of an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibody; excludes one patient with non-clear cell RCC.

Two patients with non-clear cell RCC (treatment-naïve, n=1; ICI-pretreated, n=1) were included in the “all patients” population; the ICI-naïve and previously treated ICI-naïve treatment groups are included in the appendix (p5–8).

Forty-four deaths occurred in the study; 28 occurred during the survival follow-up and 16 were attributed to TEAEs (six deaths were due to malignant neoplasm progression [n=5 in ICI-pretreated; n=1 in previously treated ICI-naïve]; ten patients had TEAE[s] with a fatal outcome which occurred regardless of relation to study drug: eight in the ICI-pretreated group (one case of cardiac arrest, one case of upper GI hemorrhage, one case of sudden death, one case of infection and hepatic failure, one case of sepsis [occurred after having received post-treatment anticancer medication], one case of hypoxia, and one case of cardiac arrest and pulmonary embolism), one case of intracranial tumor hemorrhage in the previously treated ICI-naïve group, and one case of pneumonia in the treatment-naïve group).

Notably, in the overall population, blood bilirubin increased in 3% of patients, gamma-glutamyltransferase increased in 1% of patients, and neutropenia occurred in 1% of patients.

Also considered an immune-mediated AE; additional information regarding immune-mediated AEs is provided in Table 4.

Occurred in a treatment-naïve patient on day 317.

Occurred in an ICI-pretreated patient on day 11.

Occurred in an ICI-pretreated patient on day 299, reason for death not otherwise specified.

AEs were graded by preferred term as specified according to the Medical Dictionary for Drug Regulatory Affairs version 23·0; patients with two or more of the same events were counted only once for the worst grade.

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GI, gastrointestinal; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor, INR, international normalized ratio; PD-1, programmed cell death receptor-1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; PPES, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Table 4.

Immune-mediated Adverse Events in ICI-Pretreated Patients and All Patients

| ICI-pretreateda (n=104) | All patientsb (N=145) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Patients with any event, n (%)c | 34 (33) | 9 (9) | 1 (1) | 60 (41) | 17 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Hypothyroidism | 31 (30) | 0 | 0 | 58 (40) | 0 | 0 |

| Infusion reactions | 5 (5) | 0 | 0 | 5 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Adrenal insufficiency | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 0 | 7 (5) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 6 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Severe skin reactions | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 | 2 (1) | 5 (3) | 0 |

| Colitis | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 3 (2) | 5 (3) | 0 |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Hepatitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Nephritis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Myasthenic Syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Myositis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

ICI-Pretreated group consists of patients with one or more prior lines of therapy that includes PD-1/PD-L1 ICIs; progression was required to be confirmed at least four weeks after initial assessment in the absence of rapid clinical progression; all patients were to have received at least two doses of an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibody; excludes one patient with non-clear cell RCC.

Two patients with non-clear cell RCC (treatment-naïve, n=1; ICI-pretreated, n=1) were included in the “all patients” population; the ICI-naïve and previously treated ICI-naïve treatment groups are included in the appendix (p9).

Patients with two or more of the same events would be counted only once for the worst grade; no immune-mediated grade 5 adverse events occurred.

ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; PD-1, programmed cell death receptor-1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

In total, 28/145 (19%) patients discontinued lenvatinib, pembrolizumab, or both because of treatment-related AEs (19/145 [13%] discontinued lenvatinib and 21/145 [14%] discontinued pembrolizumab; 10/145 [7%] discontinued both). No treatment-related AEs led to discontinuation of both study drugs in more than one patient. Treatment-related AEs led to dose interruptions of lenvatinib and/or pembrolizumab in 76% (110/145) of patients and dose reductions of lenvatinib in 65% (94/145) of patients. The most common treatment-related AEs (>10%) leading to dose reductions of lenvatinib were fatigue (18%; 26/145) and diarrhea (13%; 19/145. The frequency of dose reductions (and associated lenvatinib dose level) irrespective of causality are reported in the appendix (p10). The median dose intensity of lenvatinib was 14·0 mg/day (IQR 12·3–18·3), and the median relative dose intensity was 70·2% (IQR 61·3–91·6). Per protocol, no dose reductions of pembrolizumab were allowed. The median number of administrations of pembrolizumab was 15·0 (IQR 7·0–24·0). Median duration of treatment with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab among all patients was 11·6 months ([IQR 6·2–17·9]; lenvatinib, 11·4 months [IQR 6·2–17·9]; pembrolizumab, 11·0 months [IQR 4·8–17·3]).

DISCUSSION

The primary endpoint demonstrated a high ORRwk24 by investigator assessment per irRECIST in all three groups. irRECIST was chosen as it was thought to be the most representative criteria for ICI therapy at the time of protocol development. ORRs were generally similar regardless of response criteria, while PFS and DOR varied (potentially due to unconfirmed progression). Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab resulted in promising overall ORRs irrespective of prior treatment regimens.

Despite the small sample size of the treatment-naïve group, this study demonstrated that these patients had an overall ORR consistent with published results of ICI-TKI combinations (lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab (71·0%; 95% CI 66·3–75·7); pembrolizumab plus axitinib [59·3%; 95% CI 54·5–63·9] and nivolumab plus cabozantinib [ORR 55·7%; 95% CI 50·1–61·2]) from large-scale, randomized, phase 3 studies.5,8,9 Overall, patients achieving 100% reduction in target lesions without a CR suggests that non-target lesions are still present.

The safety profile observed for this combination was generally consistent with that of each agent15,20 and the combination as previously reported,18,21 with no unexpected AEs. Notably, low rates of liver enzyme elevation, neutropenia, and high-grade hand-foot syndrome were observed in this study, though high rates of low-grade hypothyroidism were observed. Treatment-related AEs resulted in dose reductions for lenvatinib in most patients. The median time to dose reduction for lenvatinib was 2·2 months (IQR: 1·4–5·2). Importantly, 69% (100/145) of patients remained at the starting dose of lenvatinib or were reduced by a single dose level (to lenvatinib 14 mg) throughout treatment. Reducing lenvatinib after initial dosing at the recommended dose is a strategy used across lenvatinib indications to provide patients with maximum therapeutic benefit while ameliorating toxicities.15 Timely identification of treatment-related AEs and management with supportive therapy as well as lenvatinib dose reductions, as needed, may have facilitated treatment continuation as a minority of patients discontinued either lenvatinib treatment or both study drugs. Pembrolizumab and lenvatinib have some known risks in common (hypothyroidism, pancreatitis); and other risks that, while different, may present similarly (immune-mediated colitis may present with diarrhea, immune-related pancreatitis may initially present with elevated amylase and lipase). Thus, evaluating attribution is important for determining appropriate clinical management. The timing of AE onset should be considered as lenvatinib is dosed daily and has a relatively short half-life (~28 hours), whereas pembrolizumab is dosed every three weeks and has a longer half-life (22 days).15,20 Severe AEs may require interrupting both drugs and prompt treatment with a corticosteroid (with the exception of hypothyroidism and type 1 diabetes) and other supportive care. Overall, AEs were generally manageable with supportive care therapies, treatment interruptions, and lenvatinib dose reductions.

The paradigm for treatment of metastatic clear cell RCC has recently changed to include combination therapies with ICI-containing regimens in the first-line setting.3 This is evidenced by the regulatory approvals20,22,23 of the following regimens based on large phase 3 trials in which the efficacy of these regimens was evaluated versus sunitinib: nivolumab plus ipilimumab,6 nivolumab plus cabozantinib,9 axitinib plus pembrolizumab,5 and axitinib plus avelumab.4 Of note, the current subsequent therapies available as second and third-line treatment options for patients with metastatic RCC have been established based on clinical trials in which patients progressed following first-line TKI monotherapy.3 Data from prospective trials in patients who have progressed on ICI-containing regimens are lacking, though very recently retrospective studies have shown some promise with ICI rechallenging in RCC.24,25 As a result, there exists a notable unmet need to identify effective therapy in patients who have progressed on treatment with an ICI-containing therapy.

To address this need, this study evaluated a large group of patients who had progressed on or following treatment with ICI-based regimens. Importantly, the efficacy results of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in ICI-pretreated patients were encouraging. Moreover, less than 5% (4/104) experienced progressive disease as their best overall response per irRECIST by investigator assessment. Notably, 38% (39/104) of the ICI-pretreated group had received prior nivolumab plus ipilimumab therapy and 65% (68/104) had received anti-VEGF therapy in combination with an ICI or sequentially; the ORRs in these two subgroups per RECIST v1.1 by IRC were comparable to the ORR of the entire ICI-pretreated group. However, there is a need to further explore the role of maintaining ICI-combination treatment as second-line treatment for metastatic RCC.

This study was limited by its nonrandomized nature and the relatively heterogeneous patient population which consisted of patients who were treatment naïve, and patients who received various prior therapies (including TKIs and prior PD-1/PD-L1 therapies−in combination or sequentially). A relatively small number of patients who were treatment naïve or previously treated ICI-naïve were enrolled, thereby limiting what efficacy-related conclusions can be drawn for patients who were ICI-naïve. Nonetheless, this large TKI-ICI combination trial of lenvatinib in combination with pembrolizumab demonstrated encouraging antitumor activity with a manageable safety profile, irrespective of prior therapies. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab may be a future potential standard-of-care treatment for patients with metastatic clear cell RCC following disease progression with ICI therapy.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed on November 12, 2020, with the terms “renal cell carcinoma” [Title/abstract] AND “advanced” [Title/abstract] AND “second line” [Title/abstract] for phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials published over the past ten years, with no restriction on language. Of the 13 reports yielded by this search, we manually excluded four articles primarily due to the enrollment of treatment-naïve patients. The nine remaining reports assessed the following in a second-line setting: tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) monotherapies, VEGF inhibitors (TKIs or bevacizumab) in combination with mTOR kinase inhibitors, bevacizumab monotherapy, mTOR kinase inhibitor monotherapy, and a novel Akt inhibitor.

Added value of this study

The combination of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab demonstrated encouraging antitumor activity in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma who received prior immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy along with previously treated patients who did not receive ICI therapy, and treatment naïve patients. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date with a TKI plus ICI in the metastatic renal cell carcinoma therapeutic setting following disease progression with prior ICI (ie, anti-PD-1/PD-L1) therapy. Notably, the safety profile of the combination was consistent with the safety profiles of each agent.

Implications of all the available evidence

The results from this study provide evidence of preliminary efficacy and safety of lenvatinib in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma, irrespective of prior therapies. This combination is being further investigated in phase 3 trials involving patients with various tumor types along with advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma (NCT02811861).

Acknowledgements:

Funding: This study was sponsored by Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co. Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Medical writing support was provided by Jessica Pannu, PharmD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc., Newtown, PA, USA, and was funded by Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. The authors would like to acknowledge Harshad Vithalbhai Amin for his contribution to this study.

Declaration of interests:

Chung-Han Lee: Support for the present manuscript: Eisai, Merck; Grants or contracts (to institution): Eisai, Merck; Consulting fees (to self): Eisai, Merck; Support for attending meetings and/or travel: Eisai; Participation in a Scientific Advisory Committee: Merck.

Amishi Yogesh Shah: Participation on an Advisory Board: Eisai, Exelixis, Pfizer, Roche; Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, EMD Serono.

Drew Rasco: Support for the present manuscript: Eisai; nothing else to disclose.

Arpit Rao: Grants or contracts (to institution): Eisai, Merck; Consulting fees (to institution): Eli Lilly & Company; Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events (self): Bayer, Cardinal Health, Eli Lilly & Company, Sanofi; Research funding (institutional): Clovis Oncology, Eli Lilly & Company; Research funding (to institution): Clovis Oncology, Eli Lilly & Company, Pfizer/Astellas, Seattle Genetics/Astellas.

Matthew H. Taylor: Clinical research funding for the present work (to institution): Eisai Inc; Honoraria for participation in Advisory Boards and speakers’ bureaus: Eisai Inc.

Christopher Di Simone: Nothing to disclose.

James J. Hsieh: Grants or contracts: Merck; Consulting fees: BostonGene, Eisai; Support for attending meetings and/or travel: Elsevier; Stock or stock options; BostonGene.

Alvaro Pinto: Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events: Bristol Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Pfizer; Support for attending meetings and/or travel: Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer.

David R. Shaffer: Nothing to disclose.

Regina Girones Sarrio: Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events: Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Roche; Support for attending meetings and/or travel: MSD-Merck, Pfizer; Participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board: Bristol Myers Squibb.

Allen Lee Cohn: Consulting fees (to self): Amgen; Payment for expert testimony (to self): Department of Justice.

Nicholas J. Vogelzang: Support for the present manuscript including provision of study patients, payments to institution, medical writing, and article writing changes; Consulting fees: Eisai, Merck; Payment for legal testimony: Merck.

Mehmet Asim Bilen: Grants or contracts (to institution): AAA, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Genome & Company, Incyte, Nektar, Peloton Therapeutics, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Tricon Pharmaceuticals, Xencor; Participation in a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board: AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Calithera Biosciences, Eisai, Exelixis, Genomic Health, Janssen, Nektar, Pfizer, Sanofi.

Sara Gunnestad Ribe: Nothing to disclose.

Musaberk Goksel: Nothing to disclose.

Øyvind Krohn Tennøe: Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events: Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb; Participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board: Bayer.

Donald Richards: Nothing to disclose.

Randy F. Sweis: Grants or contracts (to institution): AbbVie, Aduro, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, CytomX, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Genentech/Roche, Immunocore, Merck, Mirati, Moderna, Novartis, QED therapeutics; Consulting fees: Aduro, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, EMD Serono, Exelixis, Janssen, Mirati, Pfizer, Puma, and Seattle Genetics; Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events: Astellas, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Exelixis, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics. Support for attending meetings and/or travel: AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Exelixis, Mirati; Patents planned, issued or pending: PCT/US2020/031357 “Neoantigens in Cancer.”

Harshad Vithalbhai Amin: Nothing to disclose.

Jay Courtright: Nothing to disclose.

Daniel Heinrich: Support for the present manuscript (to institution): Eisai; Consulting fees: Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Ipsen, Janssen-Cilag, Roche; Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events: AAA, a Novartis company, Astellas, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Sanofi; Participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board: Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Ipsen, Janssen-Cilag, Roche; Chairman of the board: Norwegian Association of Oncology.

Sharad Jain: Stock or stock options: Merck.

Jane Wu: Employment: Eisai Inc.

Emmett V. Schmidt: Employment: Merck and Co; Stock or stock options: Merck and Co.

Rodolfo Perini: Employment: Merck and Co; Stock or stock options: Merck and Co.

Peter Kubiak: Employment: Eisai Inc.

Chinyere E. Okpara: Employment: Eisai Europe Ltd.

Alan D. Smith: Employment: Eisai Europe Ltd.

Robert J. Motzer: Support for the present manuscript: Eisai, Merck; Grants or contracts: Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche; Consulting fees: AstraZeneca, Aveo Pharmaceuticals, EMD Serono, Exelixis, Genentech, Incyte, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche; Support for attending meetings and/or travel: Bristol Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Data-sharing statement: The data are commercially confidential and will not be available for sharing at this time. However, Eisai will consider written requests to share the data on a case-by-case basis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Chung-Han Lee, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Amishi Yogesh Shah, Department of Genitourinary Medical Oncology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas, Houston, TX, USA.

Drew Rasco, Department of Clinical Research, South Texas Accelerated Research Therapeutics, San Antonio, TX, USA.

Arpit Rao, Division of Hematology, Oncology, and Transplantation, Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Matthew H. Taylor, Earle A. Chiles Research Institute, Providence Portland Medical Center, Portland, OR, USA

Christopher Di Simone, Medical Oncology/Hematology, Arizona Oncology Associates, Tucson, AZ, USA.

James J. Hsieh, Department of Medicine, Oncology Division, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA

Alvaro Pinto, Servicio de Oncología, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain.

David R. Shaffer, Medical Oncology, US Oncology Research, New York Oncology Hematology, Albany, NY, USA

Regina Girones Sarrio, Medical Oncology Service, Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La FE, Valencia, Spain.

Allen Lee Cohn, Medical Oncology, US Oncology Research, Rocky Mountain Cancer Center, Denver, CO, USA.

Nicholas J. Vogelzang, Department of Medical Oncology, US Oncology Research, US Oncology Comprehensive Cancer Centers of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA

Mehmet Asim Bilen, Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Sara Gunnestad Ribe, Medical Oncology, Sorlandet Hospital Kristiansand, Kristiansand, Norway.

Musaberk Goksel, Medical Oncology, Alaska Clinical Research Center, Anchorage, Alaska, USA.

Øyvind Krohn Tennøe, Sykehuset Østfold, Sarpsborg, Norway.

Donald Richards, Department of Oncology, US Oncology Research, Texas Oncology-Tyler, Tyler, TX, USA.

Randy F. Sweis, Section of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Jay Courtright, Department of Oncology, US Oncology Research, Texas Oncology, Dallas, TX, USA.

Daniel Heinrich, Department of Oncology, Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog, Norway.

Sharad Jain, Department of Oncology, US Oncology Research, Texas Oncology-Denton, Denton, TX, USA.

Jane Wu, Biostatistics, Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA.

Emmett V. Schmidt, Clinical Research, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA

Rodolfo F. Perini, Clinical Research, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA

Peter Kubiak, Clinical Research, Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA.

Chinyere E. Okpara, Clinical Research, Eisai Ltd., Hatfield, UK

Alan D. Smith, Clinical Research, Eisai Ltd., Hatfield, UK

Robert J. Motzer, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

References

- 1.Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ. Systemic therapy for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 354–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh JJ, Purdue MP, Signoretti S, et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017; 3: 17009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association of Urology. Renal Cell Carcinoma Guidelines 2020. Summary of Changes. https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma/?type=summary-of-changes (accessed 3 Mar 2021).

- 4.Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J, et al. Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1103–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1116–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1277–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rassy E, Flippot R, Albiges L. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immunotherapy combinations in renal cell carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2020; 12: 1758835920907504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motzer M, Alekseev B, Rha S-Y, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021: doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035716 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 829–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott DF, Lee JL, Ziobro M, et al. Open-label, single-arm, phase II study of pembrolizumab monotherapy as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2021; 39: 1029–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Glen H, et al. Lenvatinib, everolimus, and the combination in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, phase 2, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 1473–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato Y, Tabata K, Kimura T, et al. Lenvatinib plus anti-PD-1 antibody combination treatment activates CD8+ T cells through reduction of tumor-associated macrophage and activation of the interferon pathway. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0212513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura T, Kato Y, Ozawa Y, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of lenvatinib contributes to antitumor activity in the Hepa1–6 hepatocellular carcinoma model. Cancer Sci 2018; 109: 3993–4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai C, Tang J, Shen B, et al. Preclinical trial of the multi-targeted lenvatinib in combination with cellular immunotherapy for treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Exp Ther Med 2017; 14: 3221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenvima (lenvatinib) [prescribing information]. Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA: Eisai Inc.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuki M, Hoshi T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Lenvatinib inhibits angiogenesis and tumor fibroblast growth factor signaling pathways in human hepatocellular carcinoma models. Cancer Med 2018; 7: 2641–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roskoski R Jr. Classification of small molecule protein kinase inhibitors based upon the structures of their drug-enzyme complexes. Pharmacol Res 2016; 103: 26–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor MH, Lee CH, Makker V, et al. Phase IB/II trial of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, endometrial cancer, and other selected advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 1154–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: e143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keytruda (pembrolizumab) [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makker V, Taylor MH, Aghajanian C, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 2981–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inlyta (axitinib) [prescribing information]. New York, NY, USA: Pfizer Inc.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opdivo (nivolumab) [prescribing information]. Princeton, NJ, USA: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravi P, Mantia C, Su C, et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of immunotherapy rechallenge in patients with renal cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6: 1606–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gul A, Stewart TF, Mantia CM, et al. Salvage ipilimumab and nivolumab in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma after prior immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 3088–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.