Abstract

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, there were many changes in the provision of healthcare as well as home and educational environments for children. We noted an apparent increase in the number of children presenting with ingested foreign bodies and due to the potential impact of injury from this, further investigated this phenomenon.

Method

Using a prospective electronic record, data were retrospectively collected for patients referred to our institution with foreign body ingestion from March 2020 to September 2020 and compared with the same period the year prior as a control.

Results

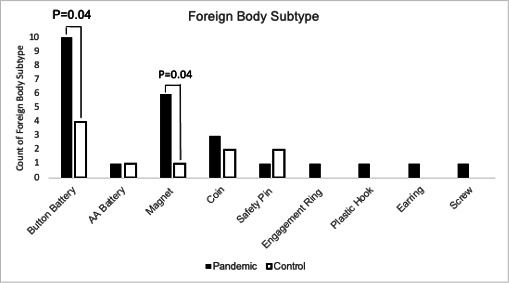

During the 6-month pandemic period of review, it was observed that 2.5 times more children were referred with foreign body ingestion (n=25) in comparison to the control period (n=10). There was also a significant increase in the proportion of button battery and magnet ingestions during the COVID-19 pandemic (p 0.04).

Conclusion

These findings raise concerns of both increased frequency of foreign body ingestion during the COVID-19 pandemic and the nature of ingested foreign bodies linked with significant morbidity. This may relate to the disruption of home and work environments and carries implications for ongoing restrictions. Further awareness of the danger of foreign body ingestion, especially batteries and magnets, is necessary (project ID: 2956).

Keywords: COVID-19

What is already known?

Foreign body ingestions, specifically button batteries and magnets, are associated with mortality and morbidity.

Cases of button battery ingestions are an increasingly concerning cause of fatality in the paediatric population over the past decade.

During the coronavirus pandemic, the home and work environment underwent significant disruption, with many children unable to attend school or nursery and caregivers working from home.

What this study adds?

This study demonstrates an increase in paediatric foreign body ingestions during the COVID-19 pandemic in North London.

This supports literature from other countries reporting an increase in foreign body ingestion in children during the pandemic.

There was an increase in the percentage of button battery and magnets ingested which is of significant concern for potential morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic started in December 2019 with the WHO declaring the outbreak as a public health emergency in January 2020.1 The first cases of coronavirus arrived in the UK at the end of January 2020. On the 3 April 2020, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health issued a position statement on delayed access to medical care during the pandemic.2 The college set out clear guidelines to reassure the general population that paediatric patients will continue to receive the care they need during this international crisis and that timely access to healthcare should continue to be sought.

It has previously been reported that 50–60 deaths per year in the UK are secondary to foreign body ingestion, with the most common foreign bodies encountered in the paediatric population being button batteries, coins and high-powered magnets.3 Notably, Litovitz et al reported 12.6% of children who ingested a 20-mm button battery suffered severe or fatal injuries.4 In addition, a more recent study in France investigated an increasing trend of urgent endoscopies in children over a 6-month period (February–July 2017). With a total of 237 referrals, 68% were found to be associated with foreign body ingestions. Of those, 25.2% had ingested a battery and 26.4% had ingested coins.5 Such findings add further weight to an evolving picture of an increase in foreign body ingestion and associated mortality in the paediatric population.

While the paediatric population has largely been protected from COVID-19-related illness, children and their caregivers have been significantly impacted by closure of schools, nurseries and enforcement of social distancing.6 7 Moreover, a wide variability in the degree to which students returned to school following the UK’s first national lockdown has been observed, which may be a result of parental preferences or requirements to self-isolate.8 With this in mind and seeing an apparent increase in presentation of children with foreign body ingestion, we sought to review the incidence, management and outcomes of referrals to our institution during the early months of the national lockdown compared with our experience before the pandemic.

Methodology

An observational, cross-sectional study design was employed. A prospective electronic data record was reviewed retrospectively to collect all patients referred with foreign body ingestion during a 6-month period of the COVID-19 pandemic and the same time period a year prior. The study was conducted in a single institution Department of Specialist Neonatal and Paediatric Surgery, Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) and registered within the trust as an audit (project ID: 2956).

Patients were identified if coded as ‘foreign body ingestion’. The inclusion/exclusion criteria for this study are as follows in table 1. No patients were actively recruited to the study; therefore, no patients required assignment for intervention and there was no requirement to individually disseminate findings.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Paediatric population: 0–16 years Admitted or referred under GOSH General surgical and/or shared with the ENT department Surgical or conservative management |

Adults Admissions under ENT Trichobezoar PICA (compulsive ingestion of nonfood articles) Food bolus impaction Fish bones History of foreign body but no foreign body identified Caustic ingestion |

ENT, Ear, Nose and Throat; GOSH, Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Risk of confirmation bias was minimised by collecting all patients with foreign body ingestion in the first instance and subsequently allocating into pandemic and control populations.

Patients were assigned to the ‘pandemic’ group if referred between March 2020 and September 2020, which encompasses the dates of school closure from 20 March 2020 to September 2020. The control group was defined as cases referred between the period of March 2019 and September 2019, 1 year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The data collected included basic epidemiology, foreign body type, time to referral, location of foreign body and management type. Both need for admission and conservative or surgical management were recorded, as well as associated complications. Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical analysis with p<0.05 considered to be significant.

Results

During the pandemic 6-month period, 25 patients were referred with foreign body ingestion compared with only 10 patients in the pre-pandemic control group. This represented a 2.5 times rise in cases. In the pandemic group, four patients were referred from outside the usual referral area but when accounting for this, a significant increase in referrals with foreign body ingestion was still noted (2.1 times greater).

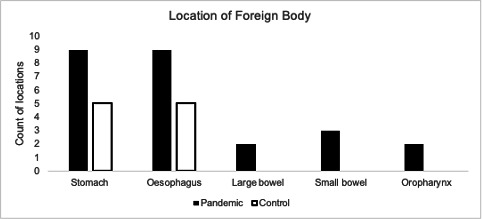

The demographics and average time to presentation are summarised in table 2. All patients were previously fit and well excluding one patient in the pandemic group with mild developmental delay and one in the control group with congenital heart disease. The most common foreign bodies encountered during the pandemic were button batteries (10), magnets (6) and coins (3). Notably, a significant increase in the number of button batteries (p=0.04) and magnets (p=0.04) was observed in the pandemic group compared with controls (figure 1). The majority of these foreign bodies during the pandemic were found within the stomach (9) followed by the oesophagus (9) (figure 2).

Table 2.

Demographic data of foreign body ingestion during coronavirus pandemic

| Pandemic (n=25) | Control (n=10) | |

| Male | 14 (56%) | 5 (50%) |

| Age, years (median, range) | 3 (10 months–14 years) | 3 (1–14 years) |

| Median days prior to presentation (range) | 0* (0–56) | 0* (0–3) |

*Days refers to immediate presentation to medical professional following foreign body ingestion.

Figure 1.

Type of foreign body ingested.

Figure 2.

Location of identified foreign body.

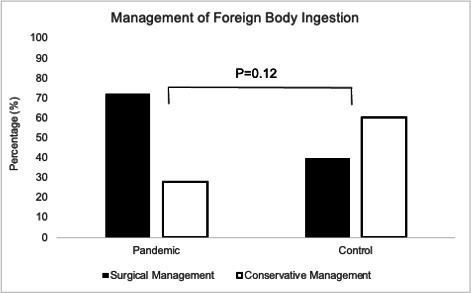

Management varied as per the type of foreign body, location and clinical picture. Surgical management included endoscopic retrieval, laparoscopy and/or laparotomy. Conservative management was based on active observation of the patient either clinically and/or with serial X-ray imaging. During the pandemic, 73% of patients required admission to GOSH compared with 40% in the control period and two-thirds of patients required surgical retrieval compared with only one-third of patients during the control period (p=0.12; figure 3). During the COVID-19 pandemic, a greater range in time to referral from time of foreign body ingestion, when known, was observed (0–56 days) compared with controls (0–3 days), but this did not reach statistical significance (table 2). We assumed that referral was made the same day as presentation to the local hospital in both groups as would be in keeping with standard practice. Three patients during the pandemic developed significant complications following their foreign body ingestion. One patient had a complex tracheobronchial injury with two subsequent reconstructive operations and a prolonged paediatric intensive care unit admission following ingestion of a button battery and delay to presentation. Two other patients had bowel perforations following ingestion of magnets and required prolonged surgical admissions and intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Figure 3.

Management of foreign body ingestion.

Discussion

We observed an increase in the number of paediatric referrals to our institution for foreign body ingestion during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hospitalisation in the paediatric population has faced different challenges in comparison to the adult population during the COVID-19 pandemic. There has been a significant reduction in paediatric admissions across European countries during the coronavirus pandemic.9 10 As part of North Central London’s regional response to COVID-19, paediatric patients were redirected to our institution directly from local emergency departments to provide capacity for local adult hospitalisation. The catchment area for referral to GOSH, however, remained the same and we would not expect foreign body ingestions to have been affected by this change, as they would ordinarily be referred to our centre at time of presentation for management even prior to COVID-19 provision restructuring. During the COVID-19 period, a notable increase of more than double the number of foreign body ingestions was observed even considering the small number of additional out of area referrals during this time.

During the COVID-19 pandemic period, we also saw a significant increase in the proportion of button batteries and magnets ingested. Both button batteries and magnet ingestion are recognised to be associated with increased mortality and poorer outcomes leading to prolonged paediatric intensive care admissions in previously fit and healthy children.11 12 These findings raise concerns regarding increased frequency and potential severity in outcomes of foreign body ingestion during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The demographic features of this study are in line with previous studies of foreign body ingestion in paediatrics. The median age of referral with foreign body ingestion in this study was between 3 years and 4 years, in keeping with the literature showing that children aged 2–4 years are most at risk of ingesting foreign bodies.13–15 In our study, the stomach and oesophagus were the most frequently referred location of foreign body, which is also in line with previous studies.16

The association between the COVID-19 pandemic and an increased trend in paediatric foreign body ingestion has been witnessed nationally and internationally. Recent evidence, in keeping with our data, shows that ingestion of magnets has increased in the UK.17 In addition, a study in Italy reviewed attendances to emergency department due to foreign body ingestion from February 2020 to April 2020 compared with 4 years prior. A statistically significant increase in button battery ingestions was noted during the pandemic.18 Furthermore, a study investigating ear, nose and throat (ENT) emergency admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic found that while attendances for ENT symptoms showed a statistically significant reduction, attendances for foreign body ingestions continued to remain high.19 The findings from our study echo this trend and thus highlight the importance of raising awareness to increasing rates of foreign body ingestion.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a greater range in time to referral from ingestion of foreign body was observed in our study compared with the control period. This difference, however, did not reach statistical significance, although our patient with the most significant morbidity had the longest delay in referral time

Households during the COVID-19 pandemic have experienced significant disruption. UNESCO states that during the COVID-19 pandemic, 1.37 billion students globally have been unable to attend school resulting in an abrupt change in family lifestyle.20 Pizzol et al 18 studied 101 cases of foreign body ingestion and found nearly all happened at home. The relationship between foreign body ingestion and the home environment has been previously explored. Litovitz et al 21 reviewed 8648 cases of battery ingestions in the paediatric population and found 61.8% of battery ingestions were obtained from household products. Therefore, the disruption of the home environment during the COVID-19 pandemic should be considered a potential factor contributing to the increase of foreign body ingestion.

This study cannot account for foreign body ingestions in North London, which were not referred to our institution during the pandemic. Subsequently, the true number may be even higher than we observed; however, this number is likely to be small as both before and during COVID-19 these patients would usually be referred to our tertiary centre. It is also important to note the relatively small sample size of patients in this study. Future research should consider a national data collection on foreign body ingestion during the COVID-19 pandemic to improve generalisability of results.

Our study highlights a concerning overall increase in foreign body ingestion with an increased proportion of button battery and magnets seen. Public health campaigning has previously resulted in successful behavioural changes and resulted in positive outcomes in reducing foreign body ingestions globally.22–24 We support ongoing campaigns to advocate for increased awareness of risks and medical emergencies associated with foreign body ingestion especially in light of the ongoing disruption due to the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

On behalf of the GOSH Team: Giuliani S, Mullassery DM, Jones C, Butler C, Blackburn S and Curry JI. All research at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health is made possible by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Twitter: @paolodecoppi

Collaborators: Giuliani S, Mullassery DM, Jones C, Blackburn S and Curry JI, Department of Specialist Neonatal and Paediatric Surgery, Great Ormond Street Hospital For Children NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom; Butler C, Department of Otolaryngology, Great Ormond Street Hospital For Children NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom.

Contributors: PDC, HT, KC and NTF designed the concept, analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in data acquisition and critically reviewing the manuscript for intellectual contents.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: No, there are no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

GOSH Team:

Giuliani S, Mullassery DM, Jones C, Butler C, Blackburn S, and Curry JI

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All individual participant data collected during the study will be made available upon request after deidentification. All statistical analysis and data collection codes will will be made available upon request. Data will be available immediately following publication with no end date. Proposals should be directed to naomi.festa@GOSH.nhs.uk. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Research ethics approval was not obtained as no human participants were actively involved in the study. Information was collected retrospectively on patients referred with foreign body ingestion. Patients were not recruited to a control or ‘treatment’ group as the control group was defined by time specific dates outside of the pandemic. There was no active treatment or intervention in this study. The group of interest were patients admitted during specified dates within the coronavirus pandemic. Therefore, research ethics approval was not required.

References

- 1. WHO . WHO timeline, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline/#!

- 2. RCPCH . Delayed access to care for children during COVID-19: our role as paediatricians – position, 2020. Available: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/delayed-presentation-during-covid-19

- 3. Avery JG, Jackson RH. Children and their accidents. BMJ 1994;308:604. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Litovitz TL, Holm KC, Clancy C. Annual report of the American association of poison control centers toxic exposure surveillance system. Am J Emerg Med 1992;1993:494–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Norsa L, Ferrari A, Mosca A. Urgent endoscopy in children: epidemiology in a large region of France. Endosc Int Open 2020;8:e969–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoffman JA, Miller EA. Addressing the consequences of school closure due to covid‐19 on children’s physical and mental well‐being. World Med Health Policy 2020;12:300–10. 10.1002/wmh3.365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Unicef . Children in Lockdown: what coronavirus means for UK children – UNICEF UK, 2020. Available: www.unicef.org.uk/coronavirus-children-in-lockdown/

- 8. Ofsted . Covid-19 series: briefing on schools, October 2020, 2020. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933490/COVID-19_series_briefing_on_schools_October_2020.pdf

- 9. Degiorgio S, Grech N, Dimech YM, et al. Withdrawn: COVID-19 related acute decline in paediatric admissions in Malta, a population-based study. Early Hum Dev 2020;9:105251. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scaramuzza A, Tagliaferri F, Bonetti L, et al. Changing admission patterns in paediatric emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:704.2–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McConnell MK. When button batteries become breakfast: the hidden dangers of button battery ingestion. J Pediatr Nurs 2013;28:e42–9. 10.1016/j.pedn.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jatana KR, Litovitz T, Reilly JS, et al. Pediatric button battery injuries: 2013 Task force update. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2013;77:1392–9. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aydoğdu S Arıkan Ç, Çakır M, et al. Foreign body ingestion in Turkish children. Turk J Pediatr 2009;51:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wai Pak M, Chung Lee W, Kwok Fung H, Pak MW, Lee WC, Fung HK, et al. A prospective study of foreign-body ingestion in 311 children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2001;58:37–45. 10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00464-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chan YL, Chang SS, Kao KL. Button battery ingestion: an analysis of 25 cases. Chang Gung Med J 2002;25:169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jayachandra S, Eslick GD. A systematic review of paediatric foreign body ingestion: presentation, complications, and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2013;77:311–7. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thakkar H, Burnand KM, Healy C, et al. Foreign body ingestion in children: a magnet epidemic within a pandemic. Arch Dis Child 2021;322106. 10.1136/archdischild-2021-322106. [Epub ahead of print: 11 May 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pizzol A, Rigazio C, Calvo PL, et al. Foreign-Body ingestions in children during COVID-19 pandemic in a pediatric referral center. JPGN Rep 2020;1:e018. 10.1097/PG9.0000000000000018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sapountzi M, Sideris G, Boumpa E. Variation in volumes and characteristics of ENT emergency visits during COVID-19 pandemic. where are the patients? Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2021;21:00002–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. UNESCO . 1.37 billion students now home as COVID-19 school closures expand, ministers scale up multimedia approaches to ensure learning continuity. Available: https://en.unesco.org/news/137-billion-students-now-home-covid-19-school-closures-expand-ministers-scale-multimedia

- 21. Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L. Preventing battery ingestions: an analysis of 8648 cases. Pediatrics 2010;125:1178–83. 10.1542/peds.2009-3038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abroms LC, Maibach EW. The effectiveness of mass communication to change public behavior. Annu Rev Public Health 2008;29:219–34. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karatzanis AD, Vardouniotis A, Moschandreas J, et al. The risk of foreign body aspiration in children can be reduced with proper education of the general population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007;71:311–5. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sadan N, Raz A, Wolach B. Impact of community educational programmes on foreign body aspiration in Israel. Eur J Pediatr 1995;154:859–62. 10.1007/BF01959798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All individual participant data collected during the study will be made available upon request after deidentification. All statistical analysis and data collection codes will will be made available upon request. Data will be available immediately following publication with no end date. Proposals should be directed to naomi.festa@GOSH.nhs.uk. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.