Abstract

Current methods used for measuring amino acid side-chain reactivity lack the throughput needed to screen large chemical libraries for interactions across the proteome. Here we redesigned the workflow for activity-based protein profiling of reactive cysteine residues by using a smaller desthiobiotin-based probe, sample multiplexing, reduced protein starting amounts and software to boost data acquisition in real time on the mass spectrometer. Our method, streamlined cysteine activity-based protein profiling (SLC-ABPP), achieved a 42-fold improvement in sample throughput, corresponding to profiling library members at a depth of >8,000 reactive cysteine sites at 18 min per compound. We applied it to identify proteome-wide targets of covalent inhibitors to mutant Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS)G12C and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK). In addition, we created a resource of cysteine reactivity to 285 electrophiles in three human cell lines, which includes >20,000 cysteines from >6,000 proteins per line. The goal of proteome-wide profiling of cysteine reactivity across thousand-member libraries under several cellular contexts is now within reach.

Considerable efforts have been devoted to analyzing amino acid side-chain reactivity in complex biological systems for drug development and discovery1–5. Among protein-encoded amino acids, cysteine merits special emphasis due to its intrinsically high nucleophilicity and sensitivity to oxidizing agents6,7. In addition, cysteine residues have been the main focus of fragment-based drug discovery8 due to their relatively well-understood reactivity at physiological pH and prevalence within active sites in diverse families of enzymes such as kinases, tyrosine phosphatases, proteases, deubiquitinating enzymes, oxidoreductases and acyltransferases9–11.

Methods used to measure the reactivity of cysteine side chains toward electrophilic fragments using mass spectrometry range from simple analyses in mass shifts of a few target proteins12 to more complex quantitative measurements of the entire proteome using stable isotopes13. However, one technique, isoTOP-ABPP14,15, has become the standard in the chemical biology field16,17. isoTOP-ABPP operates by labeling cysteine residues using an iodoacetamide probe that contains an alkyne handle for enrichment using click chemistry, an azide functionalized biotin probe containing a cleavable tag and an isotopically labeled valine residue used for relative quantification by mass spectrometry15. isoTOP-ABPP has been successfully applied to profiling of >50 electrophile fragments using cell lysates, and it has been adapted to study reversible interactions with cysteines18–22. Despite these achievements, the method requires large amounts of starting material (500 μg per electrophile) and a substantial instrument time burden results from profiling even dozens of electrophilic compounds.

Attempts to address some of the most critical steps have been made. Chemically cleavable biotin linkers have been utilized to isolate conjugated cysteine-containing peptides, bypassing on-bead digestion23–26. In addition, desthiobiotin-containing enrichment probes have recently been shown to be more efficient at recovering conjugated peptides from avidin, simplifying workflows27–29. To address throughput, tandem mass tags (TMT), which can quantify 11 samples simultaneously, have been reported26,30–32 but are not yet fully optimized for profiling of reactive cysteine sites. However, the most significant bottlenecks, including excessive instrumentation analysis times and starting materials, remain unexplored.

Here we present an optimized assay using mass spectrometry for profiling reactive cysteine sites, SLC-ABPP. SLC-ABPP was built with the goal of enabling screening of large, fragment-based libraries in a high-throughput fashion by minimizing the instrument time and sample input needed to screen each fragment without sacrificing quantitative depth. Additionally, SLC-ABPP was optimized to allow for screening in cells using multi-well plates, where the amount of material is often limited. We demonstrate that SLC-ABPP can screen effectively using five- to 20-fold lower starting protein material amounts than isoTOP-ABPP, and simultaneously reduce mass spectrometry analysis time. Using SLC-ABPP, the total analysis time needed to screen each electrophile fragment was reduced 42-fold18 by combining TMT with intelligent data acquisition using real-time searching (RTS)33,34. Finally, we demonstrate the utility of SLC-ABPP for screening of large libraries by profiling 285 small-molecule fragments in three genetically distinct cell lines in replicates at <6 d of total instrument time per line. To our knowledge, this study presents a resource that represents, to date, the largest mass spectrometry-based electrophile fragment library screen used in cells or lysates.

Results

The SLC-ABPP approach.

The workflow for SLC-ABPP is shown in Fig. 1a. Reactive cysteine sites are profiled using small-molecule electrophiles that engage cysteine side-chain thiolates by creating a covalent bond. A generalized iodoacetamide-based probe is used to differentiate and enrich conjugated cysteine-containing peptides not bound by electrophiles. Mass spectrometry is used to quantify cysteine levels after probe alkylation. The final output is displayed as competition ratios (CR) for each compound, where a ratio of ≥4 represents >75% attenuation of cysteine probe alkylation at that site (Fig. 1a). Several improvements to existing mass spectrometry-based methods15,18 were made with an eye toward increasing throughput. These included the following. First, we synthesized a new desthiobiotin iodoacetamide (DBIA) with a smaller mass than commercially available (ΔM = −158 Da) for improved enrichment and replacement of alkyne-iodoacetamide (Fig. 1b). Second, sample multiplexing was embraced with TMT11- and TMTpro16-plex reagents for both accurate quantification35–37 and a ten- to 15-fold increase in throughput (Fig. 1c). Third, the starting protein input material was initially reduced by fivefold to 100 μg (Fig. 1d). In addition, SLC-ABPP was found to be viable with even less sample input (for example, 50 or 25 μg per TMT channel) while still retaining quantitative cysteine depth (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Fourth, throughput was improved by combining RTS34 with single-shot 3-h analyses in lieu of fractionation (Fig. 1e). Fifth, the depth of analysis was extended to a depth of >8,000 cysteine sites per run, profiled across 10 to 15 samples within a single TMT-plex (three-cell-line example is given in Supplementary Fig. 1b). In combination with standard TMT labeling (ten small-molecule electrophiles per experiment) and 3-h gradients, SLC-ABPP reduced the total instrument time needed per electrophile to 18 min, representing a 42-fold improvement in acquisition speed (Fig. 1e)18. SLC-ABPP is also scalable. If greater quantitative depth is desired, the gradient length used to separate cysteine-containing peptides can be increased per TMT experiment or the sample can undergo fractionation. For example, starting with 100 μg of sample input per TMT channel and increasing the gradient time resulted in >10,000 quantified cysteine sites, while with small-scale fractionation, the quantitative depth was further increased (>12,000 sites) but at the cost of throughput (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1 |. SLC-ABPP using minimal sample input, reduced instrument time and TMT sample multiplexing.

a, Overview of the SLC-ABPP method based on TMT11- or TMTpro16-plex sample multiplexing. Steps include treatment of lysate or cells with compounds (blue circles), treatment with DBIA probe (red circles), trypsin digestion, TMT labeling, combination, avidin enrichment for biotinylated cysteine-containing peptides and analysis of CR by real-time, search-enabled, MS3-based mass spectrometry (RTS-SPS-MS3). b-d, Multiple technical improvements were made and compared to existing ABPP mass spectrometry-based methods18, which included cysteine enrichment using a custom, smaller DBIA (ΔM = 239 Da) (b), sample multiplexing using TMT reagents (c) and a fivefold reduction in total input material needed for screening each fragment (d). e, Cysteine profiling from a single 3-h gradient, resulting in fourfold less instrument time needed per experiment. In combination with 11-plex TMT labeling, SLC-ABPP reduced the average instrument time needed to profile each small-molecule fragment to 18 min, a 42-fold improvement. MudPIT, multidimensional protein identification technology.

Real-time database searching is a means of increasing the number of spectra matched without sacrificing the instrument speed characteristic of TMT-based methods38. The RTS strategy that we implemented in SLC-ABPP, termed Orbiter34, employed an analytical pipeline comprising monoisotopic peak refinement, full human database searching and filtering criteria on the fly to prioritize only matched peptides for quantification (Fig. 1). The analysis was focused on cysteine-containing peptides modified by DBIA. In real time, fast MS2 spectra acquired on the instrument were passed on to Orbiter and prompted the priority insertion of optimized quantification SPS-MS3 scans for matched peptides, eliminating nonmatching spectra that generate time-consuming MS3 scans, all on millisecond time scales. Orbiter RTS enabled SLC-ABPP to delve deeper into each sample, acquiring more cysteine-modified peptides while reducing gradient lengths (Fig. 1e).

Benchmarking SLC-ABPP using cysteine-reactive lead compounds.

To assess the proteome-wide depth of analysis from reduced starting amounts, three commercially available, cysteine-reactive lead compounds were profiled at multiple concentrations with replicates to identify both their known targets and potentially undiscovered off-targets. First, the covalent GTPase KRAS inhibitor ARS-1620, which is specific to the cysteine-12 mutant form of KRASG12C, was tested using HCC44 cells39,40. HCC44 cells carrying the G12C mutation were treated for 4 h with increasing concentrations of ARS-1620 in triplicate. Cells were harvested, and 50 μg of protein was analyzed by SLC-ABPP using a single 3-h run with RTS (Fig. 2a). Following treatment with 1 or 5 μM of ARS-1620, we identified cysteine-12 on KRASG12C as the most significantly liganded out of ~8,200 quantified cysteine sites (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 1). SLC-ABPP also identified previously reported40 (FAM213BC85) and unreported (EIF2AK4C1255) off-target sites with dose-dependent engagement in two independent SLC-APP experiments (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a,b).

Fig. 2 |. Benchmarking proteome-wide SLC-ABPP using lead compounds with known targets.

a, The SLC-ABPP experimental design facilitates the profiling of multiple concentrations with replicates within the same experiment. b, Mutant KRAS-specific G12C inhibitor ARS-1620 was profiled at three concentrations in intact HCC44 cells (4-h treatment), and SLC-ABPP quantified >8,000 cysteine sites within 3 h. Cysteine-12 of KRASG12C was the most significantly liganded site, and ARS-1620 showed dose dependence toward KRASG12C cysteine-12. c, SLC-ABPP profiling of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor THZ1 in HCT116 cell lysates using multiple concentrations quantified >8,500 cysteine sites. Target cysteine-312 on CDK7 was quantified as the most liganded cysteine. d, Ligandable proteome from spleen tissue extracted from C57BL/6 mice treated intraperitoneally with increasing concentrations of ibrutinib for 1 h. BTK cysteine-481 was identified as significantly liganded from >9,000 quantified cysteine sites. All experiments were performed with the following biological replicates: n = 2 DMSO, n = 3 for compound treatments. Data are represented as means ± s.d. Dotted lines represent a CR threshold of 4 (75% reduction in probe binding). IAA, iodoacetic acid.

To further demonstrate SLC-ABPP as a method for target engagement and off-target discovery, we profiled the ligandable landscape of the covalent cy clin-dependent kinase inhibitor THZ1 (ref.41). Following treatment with 0.2, 1 or 5 μM THZ1 using HCT116 cell lysates in triplicate, we identified cysteine-312 on CDK7 as the most significantly liganded cysteine out of ~8,600 cysteine sites (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 2). SLC-ABPP also identified cysteine-137 on immediate early response 5-like protein (IER5L), as well as cysteine-159 on ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein 6-interacting protein 4 (ARL6IP4), with dose-dependent engagement by THZ1 (Supplementary Fig. 2c,d). Neither had been reported among other off-target cysteine sites using the recently published covalent inhibitor target-site identification42.

SLC-ABPP was further used to profile the ligandable proteome of spleen tissue extracted from C57BL/6 mice treated intraperitoneally with 10 or 20 mg kg−1 ibrutinib in biological duplicate. Mice were treated for 1 h, after which splenocytes were isolated and 50 μg of protein was subjected to cysteine profiling. Following treatment with 10 or 20 mg kg−1 ibrutinib, we identified BTK cysteine-481 as one of the most significantly liganded cysteines out of ~9,200 cysteine sites (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 3). In addition, we found cysteine-313 on BLK, which contains a cysteine within the ATP binding pocket analogous to BTK43, as a target of ibrutinib (Supplementary Fig. 2e).

In summary, SLC-ABBP quantified target engagement using electrophile-containing lead compounds with unmatched sample input, speed and depth, while enabling discovery of candidate off-target proteins from compounds being considered for clinical use. In addition, these data show that SLC-ABPP is amenable to working directly with intact cells, lysates and even tissues harvested from in vivo-treated mice, with minimal changes to the workflow or decreases in quantitative cysteine depth.

Benchmarking SLC-ABPP with three scout fragment electrophiles.

Fragment-based drug discovery has become a staple of most pharmaceutical pipelines. To further test SLC-ABPP and its ability to quantify ligandable cysteine sites, three broadly reactive cysteine compounds (KB02, KB03 and KB05), referred to as scout fragments21,30, were profiled using HCT116 cell lysates (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Each scout fragment was analyzed in triplicate using a single 3-h run with RTS. Ligandable cysteine sites were defined as those showing ≥75% reduction in abundance (CR ≥ 4) compared to DMSO-treated controls as previously described18,21. SLC-ABPP quantified >8,800 cysteine sites with, on average, 1,200 ligandable sites per scout fragment, representing a twofold increase in the total number of sites compared to previously published data (Supplementary Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Table 4)18. The ligandability rate (14%) was similar in both studies, suggesting that the increase in total number of ligandable sites was the result of higher cysteineome depth achieved by SLC-ABPP. Replicate measurements showed excellent reproducibility and overlap between ligandable cysteine sites of each scout fragment, providing insights into the reactivity of three different small recognition elements (Supplementary Fig. 3c–e).

Application of SLC-ABPP to fragment-based screening of electrophile libraries.

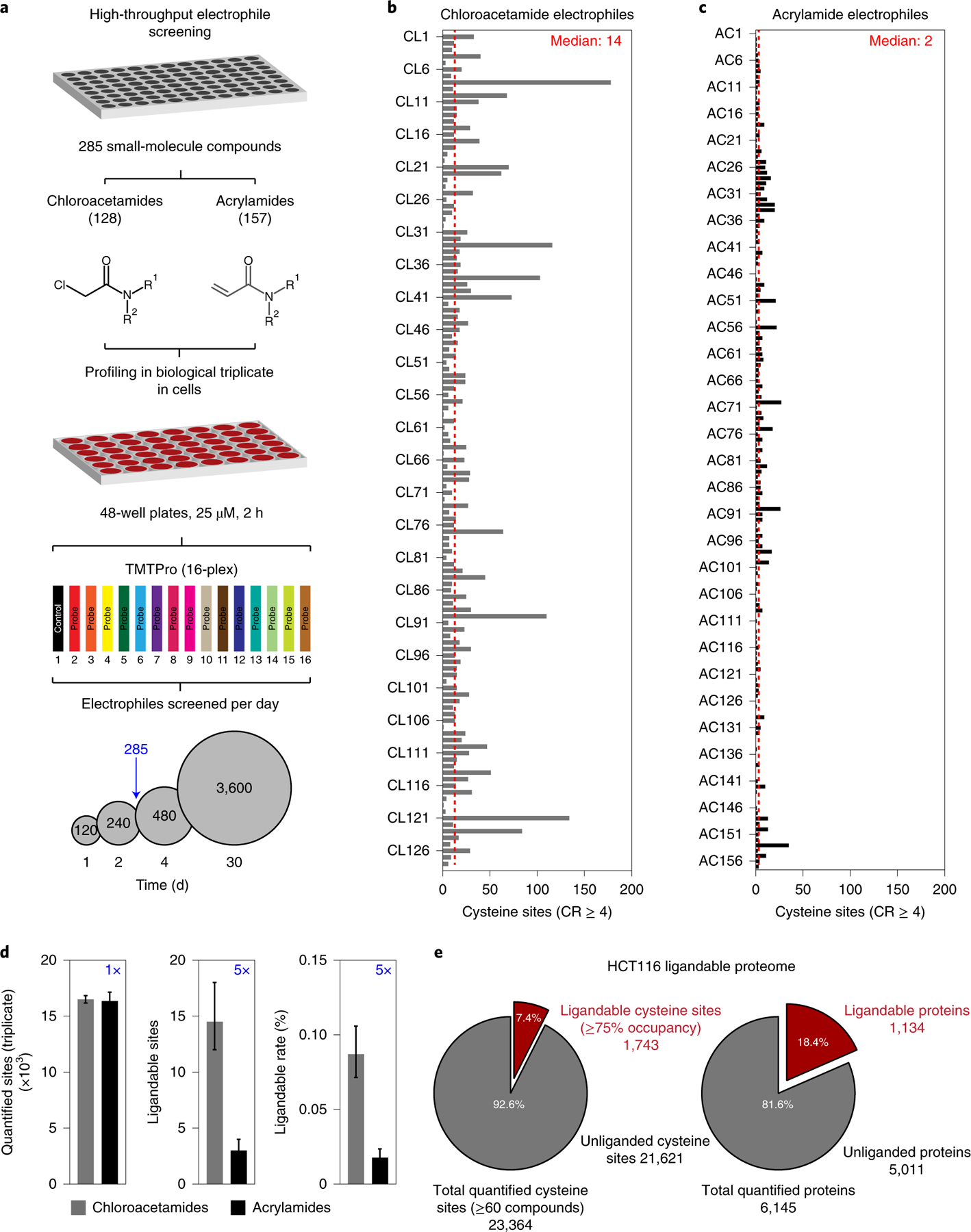

To demonstrate the feasibility of large-scale, fragment-library screening using SLC-ABPP, we purchased a cysteine-focused compound library (Fig. 3a). Our library consisted of 285 compounds arrayed in three 96-well plates. These included chloroacetamide- (128) and acrylamide-based (157) warheads with average molecular weight of 233 and 230 Da, respectively (Supplementary Table 5). Encouraged by the low input material needed for SLC-ABPP (Supplementary Fig. 1), our goal was to screen all 285 electrophiles with replicates using intact HCT116 cells. HCT116 cells were grown using 48-well plates and were treated with 25 μM of each electrophile for 2 h, generating ~30 μg of total protein material per TMT channel. Using TMTpro16-plex reagents and SLC-ABPP, 285 electrophiles were screened with replicates using ~6 d of instrument time, representing the largest global cellular mass spectrometry-based cysteine screen to date (Fig. 3a). We required cysteine sites to be quantified across ≥60 different compounds and, with the reduced starting amount of 30 μg, we achieved a quantitative depth of 16,426 ± 623 unique cysteine sites per electrophile across triplicates. Most chloroacetamide-containing electrophiles showed tempered reactivity, with a median ligandable (R ≥ 4) cysteine rate of 0.09% (~14 cysteine sites per electrophile), while acrylamides showed aproximately fivefold less reactivity with median ligandable rates of 0.018% (~2 cysteine sites per electrophile; Fig. 3b,c and Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). Substantial differences in the reactivity rates of chloroacetamides were observed, ranging from 0 to 178 (0–1.07%) ligandable cysteines per compound, while acrylamides ranged from 0 to 35 (0–0.21%), again illustrating the influence of the electrophilic warhead toward overall reactivity (Fig. 3b–d).

Fig. 3 |. High-throughput screening of a small-molecule, fragment-based electrophilic library using SLC-ABPP.

a, Library compounds (285 electrophiles), consisting of 128 chloroacetamide- and 157 acrylamide-containing fragment electrophiles, were screened at 25 μM using HCT116 cells grown in 48-well plates generating ~30 μg of protein per TMT channel. In total, 285 small-molecule fragments were screened in triplicate (n = 3 biological replicates) in HCT116 cells, in <3 d of acquisition time per replicate. With the current methodology, it is possible to screen 3,600 electrophiles with 30 d of total instrument time. b, Chloroacetamide-containing fragments showed variable reactivity across the cysteineome, with a median of 14 ligandable (CR ≥ 4) cysteines per fragment. c, Acrylamide-containing fragments displayed lower reactivity, with a median of ~2 ligandable cysteines per fragment. d, No difference in quantitative depth for cysteine measurements was observed between chloroacetamide- (n = 128 compounds) and acrylamide-containing fragments (n = 157 compounds). However, chloroacetamides liganded fivefold more sites and showed fivefold increased reactivity rates compared to acrylamide-containing fragments. e, In sum, 23,364 unique cysteine sites were quantified across 6,145 protein groups, of which 1,743 were ligandable by at least one fragment on 1,134 proteins. Data are represented as means ± s.d.

Combining data across triplicate runs and across all 285 electrophiles, we quantified 23,364 total cysteine sites from 6,145 unique protein groups, of which 1,743 (~7%) sites from 1,134 proteins were significantly liganded by at least one electrophile (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Table 6). Each cysteine site was quantified on average across 195 compounds. Finally, 62% of all liganded sites were significantly engaged by a single compound from the library, yet were quantified on average across 225 (79%) of all electrophiles.

To visualize the magnitude and organization of the ligandability data obtained from our cellular screen, we calculated the degree of specificity for each electrophile toward cysteine sites and proteins across different protein classes (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4c,d). Data distribution skewness for both the small-molecule electrophilic fragments and cysteine sites was calculated and compared to their maximum CR. Skewness values, which represent the third moment of a normal distribution, provide a measure of specificity such that higher skewness suggests greater specificity, meaning that only a few compounds hit that particular target while the maximum CR, capped at 20 (≥95% ligandable), give a measure of the strongest quantified ligandable event by any electrophile fragment (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Distribution of both small-molecule electrophiles and ligandable cysteine data showed a strong positive skew, meaning that the majority of compounds liganded cysteine sites with high specificity, and that cysteines were mostly liganded by a small number of compounds or even a single compound (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Protein kinases were well represented within the dataset and also showed a strong positive skew, with examples that included Src family kinases SRC and YES1 as well as serine/threonine kinases such as PLK1 (Fig. 4a). Other protein classes showing high representation included transcription factors and ubiquitin E3 ligases that could serve as novel sites for the design of specific tool compounds in the form of proteolysis targeting chimera warheads (PROTAC) (Fig. 4b,c)30. Surprisingly, deubiquitylases (DUBs) were under-represented with only a handful of proteins displaying high skewness, even though these require cysteines for enzymatic activity (Fig. 4d). These data further illustrate that SLC-ABPP is capable of quantifying reactive cysteine sites for many protein classes throughout the global proteome.

Fig. 4 |. Small-molecule electrophiles can display high specificity for their protein targets.

a–d, Data distribution skewness (x axis) for global cysteine sites by protein class versus maximum CR (y axis). The distribution skewness value provides a measure of the specificity of each cysteine site’s ligandability. The maximum CR, capped at 20, is the strongest detected ligandable event for each cysteine site across all 285 small-molecule electrophiles. Examples of cysteine sites across protein kinases (a), transcription factors (b), ubiquitin ligases (E3s) (c) and DUBs (d) are labeled with both maximum CR and skewness. e-g, Examples of protein-focused cysteine-reactivity maps showing the results for hundreds of compounds across all reactive cysteines for a single protein. e, Protein-focused map of the ribosomal kinase RPS6KA1 showed cysteine-441, adjacent to the ATP binding pocket, as the most ligandable among four total cysteine sites. f, Protein-focused map of specific active site cysteine ligandability of ubiquitin ligase UBE3A by chloroacetamide CL123. g, Protein-focused cysteine map for the highly reactive protein ACAT1 showing four reactive cysteine sites liganded by 24 different fragments. PDB structure of ACAT1 (2IB8) showing the structural position of each reactive cysteine (red). A highly reactive cysteine pocket containing both active site cysteines (−413 and −126) is shown. h, Paired active site ligandability for cysteines-126 (orange) and −413 (teal) displays many compounds that preferentially bind one cysteine over the other within the same binding pocket.

Protein-focused, cysteine-reactivity maps.

Using data from our cellular SLC-ABPP screen, we can visualize complete reactive-cysteine, protein-focused maps with ligandable information across 285 unique small-molecule electrophiles, serving as a resource of potential starting points for optimal probe design. We generated reactive cysteine maps for ~6,000 different proteins, of which ~1,100 contained at least one highly ligandable (R ≥ 4) cysteine using the electrophiles present within our library (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5). We chose to highlight three different protein-focused maps across different protein classes that contained many reactive cysteine sites and also included ligandable sites across hundreds of compounds (Fig. 4e–g). First, the ribosomal-related kinase RPS6KA1 was shown to contain four reactive cysteine sites, of which two were significantly liganded by at least one compound. Cysteine-441, which is adjacent to the ATP binding site, was liganded by many compounds—for example, CL8 and CL94 that could serve to sterically disrupt ATP binding (Fig. 4e). Second, the data also contained ligandable information for various catalytic cysteines that included cysteine-843 on the ubiquitin ligase UBE3A, which was quantified across all compounds but was only significantly liganded by CL123 (Fig. 4f). Although not investigated, CL123 could have the potential to block UBE3A activity. Third, we highlight how cysteine-reactivity maps in combination with structural information can lead toward multisite engagement for inhibition of enzyme activity. The mitochondrial enzyme ACAT1 has three reactive cysteines within the same pocket (Fig. 4g). These included the active site cysteine-126 and the proton donor/acceptor cysteine-413 (ref.44). We observed many fragment pairs showing high reactivity and preference for one cysteine site over the other within the same binding pocket, although on average cysteine-413 was more reactive than −126 (Fig. 4h). Using this information, two fragment compounds—for example, CL95, which shows high reactivity with cysteine-126 and CL74, which shows high reactivity with cysteine-413—might be combined using a linker, as proposed at the inception of fragment-based drug discovery,45,46 to create a potent modulator of ACAT1 activity.

Potent and selective inhibitors of enzyme activity.

In addition to screening HCT116 cells, we profiled the entire library against two additional cell lines, HEK293T and PaTu-8988T, in biological duplicate. Quantified sites showed good reproducibility, as 72% of all sites were found in at least two of three cell lines (Fig. 5a). Combining data across all three cell lines resulted in a total of 29,603 quantified cysteine sites found on 6,903 protein groups, of which 3,688 were liganded by at least one compound from 2,071 protein groups (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). The additional data generated from HEK293T and PaTu-8988T cells were used to supplement and triage hits found within our HCT116 dataset for further validation.

Fig. 5 |. Proof-of-concept rescreening of 285 compound electrophiles in two additional cell lines.

a-e, SLC-ABPP was used to profile the entire 285-compound library in two additional cell lines (HEK293T and PaTu-8988T at 25 μM in duplicate). a, Reproducibility of reactive cysteine proteome (>70% of all cysteine sites were measured in two of three cell lines). b, In total, 29,603 unique sites were quantified across 6,903 unique protein groups, of which 3,688 were ligandable by at least one fragment on 2,071 proteins in at least one cell line. c, Heatmap displaying cysteine-145 reactivity across chloroacetamide-containing electrophiles in HCT116, PaTu-8988T and HEK239T cells. MGMT cysteine-145 was significantly liganded by 66 and 67 unique electrophiles in HCT116 and PaTu-8988T cells, respectively, and showed excellent reproducibility with a rehit rate of ~80% across compounds. Note that no sites for MGMT were quantified in HEK293T cells, due to low/absent expression. d, Structure of MGMT (Protein Databank (PDB): 1QNT) showing catalytic cysteine-145 (blue). e, Cell-line-averaged, protein-focused, cysteine-reactivity map for MGMT shows preferential binding and ligandability to cysteine-145 for all chloroacetamides over two additional cysteine sites. f,g, Correlation between MGMT activity as measured using the DNA-based chemosenor NR-1 and the CR for cysteine-145 for chloroacetamides using ligandable information generated from HCT116 (f) and PaTu-8988T cells (g). Dotted lines indicate the linear equation used to determine the correlation coefficient. Compounds with high CRs showed decreased MGMT activity. h, Example workflow toward selection of the optimal starting point for synthesis of a covalent MGMT inhibitor. Fragment CL59 was found to be highly potent (inhibited >90% of MGMT activity), significantly liganded MGMT in both HCT116 and PaTu-8988T cells and was highly selective. i, Fragment CL59’s ligandable cysteine map shows remarkable specificity toward MGMT cysteine-145. Dotted lines in b represent a CR of 4, which was used to determine ligandable cysteine sites. Data are represented as means of triplicate measurements (n = 3 biological replicates). ND, not determined.

We selected 6-O-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), which was liganded by many electrophiles, as an example of how these data can be used to inform decisions surrounding enzyme activity inhibitor development. Concomitantly, the results were also dependent on the cell line studied. MGMT is a cancer driver that repairs methylated nucleobases in DNA by transferring the methyl group onto its catalytic cysteine-145 (Fig. 5c,d), rendering the enzyme irreversibly inactive47,48. Cysteine-145 reactivity on MGMT was measured across 285 and 270 electrophiles in HCT116 and PaTu-8988T cells, respectively. No cysteine sites on MGMT were quantified using HEK293T cells, presumably due to large protein expression differences (~fivefold less) compared to HCT116 cells, further illustrating the importance of screening in multiple cell lines33. MGMT cysteine-145 was significantly liganded by 66 and 67 chloroacetamide-containing electrophiles in HCT116 and PaTu-8988T cells, respectively, and it showed excellent reproducibility with a rehit rate of ~80% across compounds (Fig. 5c). Using averaged data across both cell lines, we constructed a protein-focused, cysteine-reactive map for MGMT, illustrating that cysteine-145 was significantly more reactive than two additional cysteines quantified across chloroacetamide-containing electrophiles (Fig. 5e). The recently developed DNA-based chemosenor NR-1 (refs.49,50) allowed us to confirm that chloroacetamide CR correlated with a reduction in MGMT activity, with correlation coefficients (r) of −0.715 and −0.651 for HCT116 and PaTu-8988T cells, respectively (Fig. 5f,g). As expected, fragments showing the highest CR for cysteine-145 on MGMT also displayed the lowest MGMT activity. These experiments also confirmed that no acrylamide-containing electrophile inhibited MGMT activity for HCT116 and PaTu-8988T (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). Furthermore, engagement of nearby cysteine-150 was poorly correlated with a decrease in MGMT activity, unless compounds also scored as hits for cysteine-145 on MGMT (Supplementary Fig. 6d,e).

In an effort to discover fragments that could serve as starting points toward designing a potent inhibitor of MGMT, we ranked compounds by their inhibition of MGMT and considered only those that inhibited ≥90% of its activity (19 electrophiles) while also liganding cysteine-145 in both HCT116 and PaTu-8988T cell lines (15 electrophiles) (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. 6f). Fragment CL54 was the most potent, inhibiting ~99% of MGMT activity. Nevertheless, MGMT cysteine-145 ranked only seventh out of 33 total ligandable sites (Supplementary Fig. 6g). The equally potent fragment CL59 was uniquely specific to cysteine-145 on MGMT out of >16,000 quantified sites, probably representing a better starting point for synthesis of a new inhibitor of MGMT (Fig. 5i). A molecular similarity search revealed two additional fragments that showed ~90% similarity toward fragment CL59 but possessed acrylamide warheads (AC144) and a fluorinated chromane-ring (AC22; Supplementary Fig. 6h,i). However, neither fragment was able to inhibit MGMT activity and both returned low overall proteome reactivity in all three cell lines.

These examples demonstrate how SLC-ABPP can quickly and efficiently be deployed to identify candidates for inhibitors of enzyme activity. In addition, these data demonstrate that SLC-ABPP can be used to profile large, fragment-based libraries directly in cells with high coverage and accuracy, leading to efficient design of inhibitors toward many protein classes and enzyme active sites.

Specific protein target engagement and SAR.

With our diverse pool of small-molecule fragments, we set out to find and validate examples of specific compound-cysteine engagements and how structural activity relationships (SAR) impacted the number of ligandable sites and target engagement. We focused our attention on protein kinases as an example to illustrate both inter- and intracompound specificity toward a single target. We selected cysteine-280, found on the p-loop of SRC kinase, which was quantified across 285, 270 and 285 compounds in HCT116, HEK293T and PaTu-8988T cells, respectively. Notably, only a single fragment (CL126) liganded cysteine-280 on SRC in all three cell lines (Fig. 6a). CL126 also engaged cysteine-287 on YES1, another family member of the Src kinases, which possess a near-identical ATP binding region (Fig. 6b). Both interactions were highly reproducible across cell lines (Fig. 6c) and showed high intercompound specificity for both SRC and YES1, always ranking among the top hits for CL126 (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). Treating HCT116 cells with increasing concentrations of CL126 confirmed that this interaction was significant at 50 or 25 μM, and showed ~50% occupancy at 10 and 1 μM. (Supplementary Fig. 7c). To confirm CL126 as a specific SRC binder, we used the nanoBRET assay and overexpressed SRC-luciferase fusion in HEK293T cells (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Cells treated with CL126 showed a modest ability to compete for the active site of SRC, with a decrease of ~15% in BRET signal (Fig. 6d). We posited that this was due to the size of the electrophile (~300 Da), such that it occupied only a fraction of the active site. To test this hypothesis, we competed SM-71, a recently published covalent SRC inhibitor51,52, with CL126 and measured the BRET signal (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Cells treated with CL126 showed a concentration-dependent decrease in SM-71 binding and subsequent increase in BRET signal, suggesting that both compounds compete for the same cysteine site located on the p-loop of SRC kinase (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Furthermore, in-cell target engagement was validated using pulldown assays in which CL126 was used to outcompete TL13–68, a biotin-tagged derivative of SM-71, for SRC kinase (Supplementary Fig. 6e). These data demonstrate on-target engagement of SRC cysteine-280 by CL126.

Fig. 6 |. Selective and specific SRC engagement of p-loop cysteine (C-280) by a small-molecule electrophile.

a, P-loop cysteine-280 ligandability on SRC kinase was measured across 285, 270 and 285 compounds in HCT116, HEK293T and PaTu-8988T cells, respectively. Only one chloroacetamide compound, CL126, significantly liganded cysteine-280. b, Heatmap showing all significantly liganded cysteine targets of CL126 across the three cell lines from Fig. 5, with high reproducibility between cell lines. CL126 also significantly engaged YES1, another Src family kinase, with an identical ATP binding region. c, Quantitative reproducibility between replicates for each cell line shows high reproducibility, with >90% occupancy of SRC cysteine-280 (n = 3 HCT116, n = 2 HEK293T, n = 2 PaTu-8988T biological replicates). CL126 showed tenfold higher specificity compared to the average of all other compounds. d, Cellular engagement assay by NanoBRET in HEK293T cells expressing SRC-Nluceferase and treated by either CL126 at 50 and 25 μM (n = 4 replicates) or the covalent SRC inhibitor SM-71 (n = 5 replicates) for 2 h. CL126 significantly decreased the ability of SM-71 to inhibit BRET at both 50 and 25 μM (P = 1.40−7 and P = 1.28−6). e, Representative immunoblot (n = 2 replicates) for the specified proteins after streptavidin enrichment, examining target engagement of SRC in three cell lines treated with CL126 and SM-71 for 2 h followed by incubation with 5 μM TL13–68 (biotin-containing SM-71). f,g, The library screens revealed a class of compounds containing a common cyclic sulfone core that significantly engaged cysteine-113 on the PIN1 PPIase active sites with CR values ≥ 4 in all three cell lines, suggesting SAR (f). Structure of cyclic sulfone core containing fragments with highlighted similar features (g). h, Example of CL71 ligandability map in HCT116 cells showing targeting of PIN1 cysteine-113. i, Heatmap showing all targets with hits to compounds containing a cyclic sulfone in HCT116 cells. j, PIN1 cysteine-113 is one of four targets hit by CL71 in all three cell lines. k, Example proteins from proteome-wide TMT-based expression profiling in HCT116 cells treated with CL71 at three doses for 24 h (n = 3 DMSO, n = 3 for 25 or 10 μM, n = 2 for 1 μM biological replicates). CL71 affects the stability of MYC as well as two MYC pathway proteins, PDE4B and ODC1. Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance. Data are represented as means ± s.d. ***P < 0.001. ND, not determined; NS, not significant.

Finally, we focused on proteins where the engaging small molecules contained similar structural features. Cysteine-113, found within the PPIase active site of PIN1, was reproducibly and significantly liganded by three compounds, CL41, CL71 and CL74, all of which contained a central cyclic sulfone core (Fig. 6f,g and Supplementary Fig. 7e). PIN1 enzyme isomerizes only phospho-serine/threonine-proline motifs and has therapeutic implications in cancer53. Cyclic sulfone-containing compounds were recently described as engaging cysteine-113 on PIN1 using the recombinant PIN1 PPIase domain with intact mass spectrometry methods, and SLC-ABPP was able to recapitulate these findings54. Advantageously, SLC-ABPP allowed us to assess the intercompound specificity of each cyclic sulfone compound without additional experiments. Our data demonstrated that CL71, which was the top hit for PIN1, showed good intercompound specificity, ranking PIN1 in the top five hits in all three cell lines (Figs. 6h and Supplementary Fig. 7f). All three compounds also showed similar proteome reactivity, with 12/18 total targets shared, suggesting that SAR related to the central cyclic sulfone core was responsible for overall reactivity and specificity (Fig. 6i,j). To confirm on-target engagement of PIN1 by CL71, we treated HCT116 cells for 24 h with increasing concentrations of CL71 and quantified proteome-wide changes, including those for known targets of PIN1 (Fig. 6k, Supplementary Fig. 7g–i and Supplementary Table 9). We observed a twofold downregulation of c-MYC, which is known to be regulated by PIN1 (ref.55), as well as that of additional downstream c-MYC targets (PDE3B and ODC1) (Fig. 6k)56. These effects were observed with no decrease in PIN1 protein abundance, suggesting that CL71 can inhibit PIN1 catalytic activity (Supplementary Fig. 7g). Notably, for this same compound, we did observe twofold decreases in the protein levels of several other CL71 targets after 24 h of treatment, including MGMT, PTGES2 and KEAP1, all of which were engaged on catalytic cysteines (Supplementary Fig. 7g–i). These data demonstrate on-target engagement of PIN1 by CL71.

Discussion

To fully understand the cellular role of every human protein, new tools in the form of protein-specific small-molecule binders are needed. A worldwide initiative, Target 2035, seeks to generate cell-active, potent and well characterized probes for nearly all human proteins by the year 2035 (refs.57,58). ABPP is an attractive strategy for discovering interactions between proteins and small molecules, due to its unbiased nature and inherent ability to pinpoint precise sites of protein modification.

To facilitate the screening of large compound libraries, we addressed the key rate-limiting steps in existing ABPP workflows. The resulting method, SLC-ABPP, reduced starting material amounts, incorporated sample multiplexing and utilized new enrichment steps and new software to control data acquisition, leading to shortened analysis times at increased depths. Screening time per compound was reduced by 42-fold compared to the standard in the field. When applied to known cysteine-reactive lead compounds (ARS-1620, THZ1 and ibrutinib), SLC-ABPP profiled >8,000 reactive cysteine sites in 3 h at up to three different doses in triplicate and identified KRASG12C, CDK7C312 and BTKC481 as the most ligandable cysteines, respectively. Incorporating several doses and replicates within the same 11-plex elevates the SLC-ABPP method to a true proteome-scale biological assay with no missing values.

To profile cysteine reactivity for a library with hundreds of compounds required critical changes to the entire workflow. First, quantitative precision was improved by performing a single avidin purification of cysteine-reactive peptides after combining all samples, rather than 15 individual ones. In addition, reduced sample amounts also decreased the total amount of TMT reagent necessary for screening of large libraries. The use of lower starting amounts has additional benefits, such as facilitating previously unexplored biology from sample-limited sources that could include rare cell types isolated using fluorescent activated cell sorting or patient-derived organoids, both of which have hitherto been inaccessible.

Second, switching to a desthiobiotin-based probe obviated the need for the click chemistry used to incorporate a cleavable, biotin-based enrichment handle. The DBIA probe used here was synthesized to be smaller (by 158 Da) than a commercially available reagent, making it more favorable for mass spectrometry-based experiments. The change in mass due to the modification of cysteines by this reagent is significantly smaller (by 225 Da) than the current isoTOP probe (239 versus 464 Da)14,15. The DBIA probe can be quantitatively released from avidin at low pH in organic solvent (0.1% trifluoracetic acid (TCA) in acetonitrile).

Third, to acquire the CR, we created software to control the collection of quantification scans on the mass spectrometer34. A real-time database search (RTS) using the open-source Comet algorithm59,60 identified eluting peptides. Peptides harboring a cysteine modified by the DBIA probe prompted the priority insertion of the quantification (MS3) scan. In this way, the analyses ran deeper with reduced gradient times. Without RTS, longer gradients would have been needed to achieve the same depth. Finally, the RTS strategy employed here using the Comet algorithm is now a standard feature on the Orbitrap Eclipse platform61.

Looking forward, the SLC-ABPP method could be improved further in several ways. The DBIA reagent could be added directly to growing cells, obviating the need for gentle lysis at physiological pH62. In addition, we have synthesized both heavy (+6 Da) and light (+0 Da) versions of the DBIA probe (data not shown), which provide the potential for hyperplexing up to 32 samples in the same analysis, thereby improving throughput63. Finally, the method could be adapted to accommodate profiling of compound reactivity toward additional amino acids such as lysine64 and tyrosine65.

In conclusion, we have improved multiplexed chemical proteomics to enable screening of large libraries of electrophiles, and present comprehensive reactive cysteine maps for ~6,000 proteins and ligandability information across 285 unique electrophiles in cells at low micromolar concentrations. Our results indicate that the human proteome contains a myriad of reactive cysteine sites that may act as pressure points to inhibit or alter a protein’s activity, disrupt its homeostasis by triggering its degradation or remodel its protein-protein interactions. We envision that these cysteine-reactive maps will inform future design of probes targeted toward enzyme active sites and as starting points for the design of covalent warheads for targeted protein degradation30. Our future endeavors using SLC-ABPP will now focus on profiling libraries containing thousands of electrophiles to further extend this large ligandable chemical biology resource.

Methods

Materials.

Isobaric TMT reagents and the BCA protein concentration assay kit were sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Empore-C18 material for in-house StageTips was acquired from 3 M and Sep-Pak cartridges (100 mg) were purchased from Waters. All solvents used for liquid chromatography were purchased from J.T. Baker. Mass spectrometry-grade trypsin and Lys-C protease were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific and Wako, respectively, and the SRC NanoBRET assay was purchased from Promega. Unless otherwise noted, all other chemicals were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Cell culture.

HCT116, HEK293T and HCC44 cells used in the SLC-ABPP experiments were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, and PaTu-8988T cells were purchased from DSMZ. For lysate analysis, HEK293T and HCT116 cells were expanded using DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 U ml−1 streptomycin. Cells were grown at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator until ~80% confluent, after which they were harvested using 0.05% trypsin. The cells were pelleted with centrifugation and washed once with PBS before storage at −80 °C until future use. RAMOS and HCC44 cells were cultured and harvested as described above using RPMI-1640 medium.

For in-cell labeling with cysteine-reactive electrophiles, HCT116, HEK293T and PaTu-8988T cells were seeded at ~100,000 cells per well in a 48-well plate in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 U ml−1 streptomycin. Cell were grown at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24 h. Compounds were added to cells as 2× DMSO stocks (25 μM final concentration) and mixed well, before incubation for 2 h. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (300g, 4 min at 4 °C), washed twice with PBS and transferred to 1-ml low-retention Eppendorf tubes. Cells were immediately lysed using lysis buffer or stored at −80 °C until future use.

Synthesis and purification of the DBIA probe.

Reactions for DBIA were monitored by proton and carbon NMR and high-resolution mass spectrometry, and were purified using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to >95% purity (Supplementary Data 1).

To create DBIA, to a solution of desthiobiotin NHS-ester (100 mg, 0.32 mmol) in dichloromethane were added N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.32 mmol) and n-boc ethylenediamine (0.32 mmol), and the reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere. The solvent was then removed in vacuo and the resulting oil was dispersed in 20% TFA in dichloromethane (DCM) and stirred for 3 h at room temperature. The TFA and DCM were removed in vacuo to yield a yellow oil, which was dispersed in 15 ml of DMF (dimethylformamide)/ DCM (1:2 v/v), to which was added N,N-diisopropylethylamine (1.6 mmol) and iodoacetic anhydride (250 mg, 0.71 mmol). The reaction was stirred in the dark for 2 h at room temperature before quenching with 10 ml of water. The aqueous layer was isolated and lyophilized before purification by reversed-phase HPLC (20–75% acetonitrile in H2O with 0.1% formic acid (FA)). Fractions containing product were lyophilized to yield the final product compound (109 mg, 80% yield) as a white solid.

In vivo ibrutinib treatment.

In vivo studies were performed according to a protocol adapted from Lanning et al.43. All mouse studies were performed following protocols that received approval from The Scripps Research Institute-Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee office. Briefly, C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with either ibrutinib (10 and 20 mg kg−1 mouse body weight) or vehicle (DMSO) as a 17:1:1:1 (v/v/v/v) solution of saline/EtOH/DMSO/ Cremophor EL at 10 μl g−1 mouse body weight. The treatment was performed for 1 h, after which mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The spleens were harvested and washed with cold PBS (2 × 5 ml). Total splenocytes were isolated by grinding the spleens with a syringe plunger and passage through a 70-μm cell strainer with cold buffer containing FBS (2%) and EDTA (1 mM). Splenocytes from each treatment were transfered to low-retention Eppendorf tubes for subsequent mass-spectrometry-based analysis of proteome-wide ibrutinib target landscape (140–185 × 106 cells). The cells were pelleted (600g, 8 min), washed with cold PBS and flash-frozen until further analysis.

Cell growth for electrophilic global proteomics analysis.

HCT116 cells were plated at 300,000 cells per well in a 12-well plate in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 U ml−1 streptomycin. Cell were grown at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24 h. The next day, cells were treated with increasing concentrations of each compound and resuspended in culture medium at 2× DMSO stocks (1, 10 and 25 μM final concentration) for 24 h in the incubator. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (300g, 4 min at 4 °C), washed twice with PBS and transferred to 1-ml low-retention Eppendorf tubes. Cells were immediately lysed with lysis buffer or stored at −80 °C until future use.

Sample preparation for SLC-ABPP.

Frozen cell pellets for lysate, cell analyses or mouse tissue were lysed using PBS (pH 7.4). Samples were further homogenized, and DNA was sheared using sonication with a probe sonicator (20 × 0.5-s pulses) at 4 °C. Total protein was determined using a BCA assay and cell lysates were used immediately for each experiment. Depending on the experiment, 25–100 μg of total cell extract was aliquoted for each TMT channel for further downstream processing. To determine the quantitative depth that could be achieved using SLC-ABPP, each TMT channel containing 100 μg of cell extract was treated with 500 μM DBIA for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. Excess DBIA, along with disulfide bonds, were quenched and reduced using 5 mM dithiothreitol for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Subsequently reduced cysteine residues were alkylated using 20 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. To facilitate removal of quenched DBIA and incompatible reagents, proteins were precipitated using chloroform/methanol. Briefly, to 100 μl of each sample, 400 μl of methanol was added followed by 100 μl of chloroform with thorough vortexing. Next, 300 μl of HPLC-grade water was added and the samples were mixed to facilitate precipitation. Samples were centrifuged at maximum speed (14,000 r.p.m.) for 3 min at room temperature, the aqueous top layer was removed and the samples were washed twice additionally with 500 μl of methanol. Protein pellets were resolubilized in 200 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid (EPPS) at pH 8.5 and digested using LysC and trypsin (1:100 enzyme/protein ratio) overnight at 37 °C using a ThermoMixer set to 1,200 r.p.m. The next day, samples were labeled with TMT reagents or stored at −80 °C until further use.

Sample preparation for whole-proteome analysis.

Frozen cell pellets from HCT116 cells were lysed using 8 M urea and 200 mM EPPS at pH 8.5 with protease inhibitors. Samples were further homogenized, and DNA was sheared via sonication using a probe sonicator (20 × 0.5-s pulses, level 3). Total protein was determined using a BCA assay and cell lysates were used immediately or stored at −80 °C until future use. A total of 50 μg of protein was aliquoted for each TMT channel for further downstream processing. Protein extracts were reduced using 5-Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, reduced cysteine residues were alkylated using 10 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Samples were precipitated using chloroform/methanol as previously described and digested using LysC and trypsin (1:100 enzyme/protein ratio) overnight at 37 °C using a ThermoMixer set to 1,200 r.p.m. The next day, samples were labeled with TMT reagents or stored at −80 °C until further use.

TMT labeling.

Digested peptides containing DBIA-conjugated cysteines or peptides generated for whole-proteome analysis were labeled using TMT11- or TMTpro16-plex reagents as previously described37,66. Briefly, peptides were labeled in a 1:2 ratio by mass (peptides/TMT reagents) for 1 h with shaking at 1,200 rp.m.. To equalize protein loading, ~2 μg of each sample was aliquoted and a 60-min quality control analysis (ratio check) was performed using SPS-MS3. Excess TMT reagent was quenched with hydroxylamine (0.3% final concentration) for 15 min at room temperature. Next, samples were mixed 1:1 across all TMT channels and the pooled sample was dried using a Speedvac to ensure that all acetonitrile was removed.

Cysteine peptide enrichment using streptavidin.

Pierce streptavidin magnetic beads were washed with PBS pH 7.4 before use. To each TMT-labeled pooled sample, 70 μl of a 50% slurry of streptavidin beads was added. Samples were further topped up with 1 ml of PBS in a 2-ml Eppendorf tube. Samples and beads were allowed to mix by rotating end-over-end for 4 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C to enrich for TMT-labeled, DBIA-conjugated cysteine peptides. Following enrichment, the beads were placed on a magnetic rack and allowed to equilibrate for 5 min. Beads were washed to remove nonspecific binding using the following procedure: 3 ×1 ml of PBS pH 7.4, 2 × 1 ml of PBS with 0.1% SDS pH 7.4 and, finally, 3 × 1 ml of HPLC-grade water. Beads were resuspended using a pipette between washes and placed on the magnet between each wash. To elute cysteine-containing peptides, 500 μl of 50% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA was added and the beads were mixed at 1,000 r.p.m. for 10 min at room temperature. Eluted peptides were transferred to a new tube, and the beads were additionally washed with 200 μl of 50% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA and combined. Cysteine-containing peptides were dried to completion using a Speedvac and were stored at −80 °C.

Desalting of cysteine-containing peptides.

TMT-labeled, cysteine-containing peptides were resuspended using 200 μl of 1% FA and were desalted using StageTips as previously described66. Briefly, eight 18-guage cores were packed into a 200-μl pipette tip and were passivated and equilibrated using the following solutions: 100 μl of 100% methanol, 70% acetonitrile 1% FA and 5% acetonitrile 5% FA. Peptides were loaded and washed with 1% FA, eluted using 150 μl of 70% acetonitrile 1% FA and dried to completion using a Speedvac. Enriched peptide samples were next resuspended in 5–10 μl of 5% acetonitrile 5% FA, and 50–100% of the sample was injected for analysis using real-time, search-enabled, MS3-based mass spectrometry-liquid chromatography (LC-RTS-SPS-MS3).

Basic pH reversed-phase StageTips fractionation for cysteine peptides.

Regarding the data shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, peptides for fractionation were enriched as described above but were resuspended in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) pH 8.0. Peptides were fractionated using a 10, 18-gauge core packed 200-μl pipette tip that was passivated and equilibrated using the following solutions: 100 μl of 100% methanol, 50% acetonitrile 10 mM ABC pH 8.0 and 10 mM ABC pH 8.0. Peptides were loaded and eluted in sample vials using three acetonitrile bumps: 10% acetonitrile 10 mM ABC pH 8.0, 20% acetonitrile 10 mM ABC pH 8.0 and, finally, 50% acetonitrile 10 mM ABC pH 8.0. Fractionated peptides were dried to completion using a Speedvac, resuspended with 100 μl of HPLC-grade water and dried again to evaporate any remaining ABC. Fractionated peptides were resuspended in 5–10 μl of 5% acetonitrile 5% FA, and 50–100% of the sample was analyzed using LC-RTS-SPS-MS3.

Basic pH reversed-phase fractionation for whole-proteome analysis.

Pooled peptide samples from the whole-proteome analyses of electrophile-treated HCT116 cells were first desalted using a 100-mg Sep-Pak solid-phase extraction cartridge as described previously66. After drying the sample in the Speedvac, peptides were resuspended in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 5% acetonitrile, pH 8.0 buffer, fractionated with basic pH reversed-phase HPLC using an Agilent 300 extend C18 column and collected into a 96-deep-well plate. Peptides were subjected to a 50-min linear gradient in 13–43% buffer B (10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 90% acetonitrile, pH 8.0) at a flow rate of 0.250 ml min−1. Samples were consolidated into 24 fractions as previously described, and 12 nonadjacent fractions were desalted using StageTips before analysis. Fractionated peptides were resuspended in 5–10 μl of of 5% acetonitrile 5% FA, and 50% of the sample was analyzed using LC-RTS-SPS-MS3.

Mass spectrometry and real-time searching.

All mass spectrometry data were acquired using an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer in-line with a Proxeon NanoLC-1200 UPLC system. Peptides were separated using an in-house 100-μm capillary column packed with 35 cm of Accucore 150 resin (2.6 μm, 150 Å; Thermo Fisher Scientific) using either 120 (whole proteome), 180 (lead compounds) or 210 (electrophile screen) min gradients of 4–24% acetonitrile in 0.125% FA per run, unless otherwise noted. Eluted peptides were quantified using the synchronous precursor selection (SPS-MS3) method for TMT quantification. Briefly, MS1 spectra were acquired at 120-K resolving power with a maximum of 50-ms ion injection in the Orbitrap. MS2 spectra were acquired by selection of the top ten most abundant features via collisional induced dissociation in the ion trap using an automatic gain control (AGC) setting of 15 K, quadrupole isolation width of 0.5 m/z and a maximum ion accumulation time of 50 ms. These spectra were passed in real time to the external computer for online database searching.

Intelligent data acquisition using real-time searching (RTS) was performed using Orbiter34. Cysteine-containing peptides or whole-proteome peptide spectral matches were analyzed using the Comet search algorithm (release_2019010) designed for spectral acquisition speed59,60. The same forward- and reversed-sequence human protein databases were used for both the RTS search and the final search (Uniprot). The RTS Comet functionality has been released and is available at http://comet-ms.sourceforge.net/. Real-time access to spectral data was enabled by the Thermo Scientific Fusion API (https://github.com/thermofisherlsms/iapi). The core search functionalities demonstrated here have also been incorporated into the latest version of the Thermo Scientific instrument control software (Tune 3.3 on Orbitrap Eclipse)61. Next, peptides were filtered using simple initial filters that included the following: not a match to a reversed-sequence, maximum PPM error <50, minimum cross-correlation 0.5, minimum deltaCorr 0.10 and minimum peptide length 7. If peptide spectra matched those above, an SPS-MS3 scan was performed using up to 10 b- and y-type fragment ions as precursors with an AGC of 200 K for a maximum of 200 ms, with a normalized collision energy setting of 65 (TMT11) or 55 (TMTPro16)37.

Mass spectrometry data analysis.

All acquired data were searched utilizing the open-source Comet algorithm (release_2019010) using a previously described informatics pipeline67–70. Spectral searches were performed using a custom FASTA-formatted database that included common contaminants, reversed sequences (Uniprot Human, 2014) and the following parameters: 50 PPM precursor tolerance, fully tryptic peptides, fragment ion tolerance of 0.9 Da and a static modification by TMT11 (+229.1629 Da) or TMTPro16 (+304.2071 Da) on lysine and peptide N-termini. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.0214 Da) was set as a static modification, while oxidation of methionine residues (+15.9949 Da) and DBIA on cysteine residues (+239.1628) were set as variable modifications. Peptide spectral matches were filtered to a peptide false discovery rate (FDR) of <1% using linear discriminant analysis employing a target-decoy strategy. Resulting peptides were further filtered to obtain a 1% protein FDR at the entire dataset level (including all plexes per cell line), and proteins were collapsed into groups. Cysteine-modified peptides were further filtered for site localization using the AScore algorithm with a cutoff of 13 (P < 0.05) as previously described68. Overlapping peptide sequences generated from different charge states, elution times and tryptic termini were grouped together into a single entry. A single quantitative value was reported, and only unique peptides were reported. Reporter ion intensities were adjusted to correct for impurities during synthesis of different TMT reagents according to the manufacturer’s specifications. For quantification of each MS3 spectrum, a total sum signal-to-noise of all reporter ions of 100 (TMT11-plex) or 160 (TMTPro16-plex) was required. Lastly, peptide quantitative values generated from the in-cell screens or whole-proteome analyses were normalized so that the sum of the signal for all proteins in each channel was equal, to account for sample loading differences (column normalization). This normalization was not performed for scout fragment data (Supplementary Fig. 3), since the total change in TMT channel intensity was expected to be large.

SLC-ABPP CR calculation.

Cysteine-site-specific engagement was assessed by the blockage of DBIA probe labeling. Peptides showing >95% reduction in TMT intensities in electrophile-treated samples were assigned a maximum ratio of 20 for graphing purposes with preserved ranking. Peptides containing multiple cysteines with highly confident localization scores (AScore >50) were designated as separate entries. TMT reporter ion sum-signal-to-noise for each SLC-ABPP experiment was used to calculate CRs by dividing the control channel (DMSO) by the electrophile-treated channel. Replicate measurements were averaged and reported as a single entry. To avoid false positives, sites with large coefficients of variation had the highest replicate CR values removed before averaging, as previously described18.

In vitro MGMT activity assay.

The DNA chemosenor NR-1 was synthesized and used to determine MGMT activity as previously described49,50. Briefly, purified NR-1 was dissolved in water and the concentration was confirmed by measuring absorbance at 500 nm and using the extinction coefficient 95,600 M−1 m−1. Purified recombinant human MGMT was purchased from Abcam. All assays were carried out at 37 °C in 70 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 5 mM EDTA and 1 mM TCEP. To assess inhibition, 60 nM of MGMT was spiked into 9 μg μl−1 of HCT116 cell lysate and preincubated with 25 μM of each electrophile for 30 min at 37 °C in a 384-well plate in triplicate. Chemosenor NR-1 was added at a final concentration of 35 nM and was incubated until a plateau in fluorescence was observed (~10 min). Fluorescence was measured at an excitation of 485 nm and emission of 538 nm using a plate reader. All readings were normalized to those obtained after the addition of the probe alone.

SRC NanoBRET assay.

HEK293T assays were performed in 96-well format and cells were transiently transfected using SRC-NanoLuc Fusion Vector (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HEK293T cells were prepared in DMEM/F12 medium at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well. DNA mixtures were prepared in the following ratios in 1 ml of Opti-MEM without serum or phenol red: 1.0 μg ml−1 SRC-NanoLuc Fusion vector and 25 μl of PEI were added to the DNA mixture to form lipid-DNA complexes, mixed by inversion and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Lipid-DNA complexes were then combined with the cell suspension at a 1:20 ratio and 100 μl of the final mixture was added to white 96-well culture plates (Corning). Transfected cells were incubated in a humidified, 37 °C, 5% CO2 tissue culture incubator for 20 h.

Tracer and NanoBRET reagents were prepared as working solutions according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following 20 h of incubation, cells were treated with either 50 or 25 μM (final concentration) CL126 prepared in Opti-MEM for 1 h. After 1 h, 5 μM SM-71 and 1 μM tracer were added for an additional 1 h. Each sample was treated in at least triplicate. To measure BRET, nanoBRET NanoGlo Substrate (Promega) and Extracellular NanoLuc Inhibitor (Promega) were added according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol, and filtered luminescence was measured on a Envision plate reader equipped with 460-nm BP filter (donor) and 590-nm LP filter (acceptor), using 1.0 s of integration time. Milli-BRET units (mBU) are calculated by multiplying the raw BRET values by 1,000.

SRC IP engagement assay.

For cellular target engagement analysis, HCT116, HEK293T and PaTu-8988T cells were grown in 24-well plates and treated with either 25 μM CL126 or 2 μM SM-71 for 2 h, followed by rinsing twice with PBS, harvesting and lysing with sonication in PBS (pH 7.4). Cell lysates were incubated with 5 μM TL13–68 with constant rocking at room temperature for 4 h, followed by pulldown using streptavidin beads overnight at 4 °C. Proteins pulled down on beads were rigorously washed using 3 ml of PBS and 3 ml of PBS + 0.5% SDS. Proteins were eluted using hexafluoro-2-propanol and were fully dried using a Speedvac. Proteins were resuspended in loading buffer, separated using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized using immunoblotting. Proteins of interest were detected using the following antibodies from Cell Signaling Technologies at a dilution of 1:5,000: SRC (36D10, rabbit) and GAPDH (D16H11 XP, rabbit).

Skewness plots.

Mean CR from the data were partitioned by site, protein and small-molecule fragment. The maximum CR for each partition were calculated, and the skewness of the distribution of nonmissing values for each was computed using the skewness function from the moments R package (v.0.14)71. Skewness versus maximum CR was plotted using ggplot2 (v.3.2.1)72. All above analyses were performed using R (v.3.5.2)73.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was measured using one-way analysis of variance in Graphpad Prism (v.8.2.1). Whole-proteome analysis was performed in R (v.3.5.2), and P values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method and filtered at q < 0.05. Other data analyses were also conducted in R (v.3.5.2). Please refer to the Nature Research Reporting Summary for additional information.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry data have been deposited at the ProteomeXchange Consortium with the dataset identifier PXD022511. Source data are provided with this paper. SLCAPP data generated during this study are also avaliable using the viewer on the Gygi lab website (https://gygi.hms.harvard.edu/resources.html).

Code availability

The RTS Comet functionality has been released and is available at http://comet-ms.sourceforge.net/. Real-time access to spectral data was enabled by the Thermo Scientific Fusion API (https://github.com/thermofisherlsms/iapi).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Gygi laboratory for fruitful discussions about this work. We thank A. Reed for assistance with mouse experiments. We thank F. Ferguson, G. Du and N. Gray for providing SM-71 and TL13-68 for SRC experiments. This work was supported in part through a sponsored research agreement with Google Ventures and Third Rock Ventures and grants from the NIH (nos. GM67945 to S.P.G., CA231991 to B.F.C. and CA217809 to E.T.K.), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Claudia Adams Barr Program for Innovative Cancer Research Award and the Hale Family Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research (to J.D.M.).

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-00778-3.

Competing interests

B.F.C. is a founder and scientific advisor of Vividion Therapeutics. S.P.G. is a member of the scientific advisory boards of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cell Signaling Technology and Casma Therapeutics. S.P.G. is a founder of Cedilla Therapeutics and a scientific advisor to Third Rock Ventures. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-00778-3.

References

- 1.Long MJC & Aye Y Privileged electrophile sensors: a resource for covalent drug development. Cell Chem. Biol 24, 787–800 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurais AJ & Weerapana E Reactive-cysteine profiling for drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 50, 29–36 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gehringer M & Laufer SA Emerging and re-emerging warheads for targeted covalent inhibitors: applications in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. J. Med. Chem 62, 5673–5724 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang T, Hatcher JM, Teng M, Gray NS & Kostic M Recent advances in selective and irreversible covalent ligand development and validation. Cell Chem. Biol 26, 1486–1500 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts AM, Ward CC & Nomura DK Activity-based protein profiling for mapping and pharmacologically interrogating proteome-wide ligandable hotspots. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 43, 25–33 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cravatt BF, Wright AT & Kozarich JW Activity-based protein profiling: from enzyme chemistry to proteomic chemistry. Annu. Rev. Biochem 77, 383–414 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pace NJ & Weerapana E Diverse functional roles of reactive cysteines. ACS Chem. Biol 8, 283–296 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray CW & Rees DC The rise of fragment-based drug discovery. Nat. Chem 1, 187–192 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giles NM, Giles GI & Jacob C Multiple roles of cysteine in biocatalysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 300, 1–4 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulaj G, Kortemme T & Goldenberg DP Ionization-reactivity relationships for cysteine thiols in polypeptides. Biochemistry 37, 8965–8972 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddie KG & Carroll KS Expanding the functional diversity of proteins through cysteine oxidation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 12, 746–754 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnick E et al. Rapid covalent-probe discovery by electrophile-fragment screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 8951–8968 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gygi SP et al. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat. Biotechnol 17, 994–999 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weerapana E, Speers AE & Cravatt BF Tandem orthogonal proteolysis-activity-based protein profiling (TOP-ABPP) - a general method for mapping sites of probe modification in proteomes. Nat. Protoc 2, 1414–1425 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weerapana E et al. Quantitative reactivity profiling predicts functional cysteines in proteomes. Nature 468, 790–797 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martell J & Weerapana E Applications of copper-catalyzed click chemistry in activity-based protein profiling. Molecules 19, 1378–1393 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weerapana E, Simon GM & Cravatt BF Disparate proteome reactivity profiles of carbon electrophiles. Nat. Chem. Biol 4, 405–407 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Backus KM et al. Proteome-wide covalent ligand discovery in native biological systems. Nature 534, 570–574 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grüner BM et al. An in vivo multiplexed small-molecule screening platform. Nat. Methods 13, 883–889 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews ML et al. Chemoproteomic profiling and discovery of protein electrophiles in human cells. Nat. Chem 9, 234–243 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bar-Peled L et al. Chemical proteomics identifies druggable vulnerabilities in a genetically defined cancer. Cell 171, 696–709 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senkane K et al. The proteome-wide potential for reversible covalency at cysteine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 58, 11385–11389 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Hahne H, Kuster B & Verhelst SHL A simple and effective cleavable linker for chemical proteomics applications. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 237–244 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian Y et al. An isotopically tagged azobenzene-based cleavable linker for quantitative proteomics. ChemBioChem 14, 1410–1414 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nessen MA et al. Selective enrichment of azide-containing peptides from complex mixtures. J. Proteome Res 8, 3702–3711 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabalski AJ, Bogdan AR & Baranczak A Evaluation of chemically-cleavable linkers for quantitative mapping of small molecule-cysteinome reactivity. ACS Chem. Biol 14, 1940–1950 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okerberg ES et al. Identification of a tumor specific, active-site mutation in casein kinase 1α by chemical proteomics. PLoS ONE 11, e0152934 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao S et al. Leveraging compound promiscuity to identify targetable cysteines within the kinome. Cell Chem. Biol 26, 818–829 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanon PRA, Lewald L & Hacker SM Isotopically labeled desthiobiotin azide (isoDTB) tags enable global profiling of the bacterial cysteinome. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 59, 2829–2836 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Crowley VM, Wucherpfennig TG, Dix MM & Cravatt BF Electrophilic PROTACs that degrade nuclear proteins by engaging DCAF16. Nat. Chem. Biol 15, 737–746 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rauniyar N & Yates JR Isobaric labeling-based relative quantification in shotgun proteomics. J. Proteome Res 13, 5293–5309 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vinogradova EV et al. An activity-guided map of electrophile-cysteine interactions in primary human T cells. Cell 182, 1009–1026 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erickson BK et al. Active instrument engagement combined with a real-time database search for improved performance of sample multiplexing workflows. J. Proteome Res 18, 1299–1306 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweppe DK et al. Full-featured, real-time database searching platform enables fast and accurate multiplexed quantitative proteomics. J. Proteome Res 19, 2026–2034 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauniyar N & Yates JR Isobaric labeling-based relative quantification in shotgun proteomics. J. Proteome Res 13, 5293–5309 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Connell JD, Paulo JA, O’Brien JJ & Gygi SP Proteome-wide evaluation of two common protein quantification methods. J. Proteome Res 17, 1934–1942 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J et al. TMTpro reagents: a set of isobaric labeling mass tags enables simultaneous proteome-wide measurements across 16 samples. Nat. Methods 17, 399–404 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erickson BK et al. Active instrument engagement combined with a real-time database search for improved performance of sample multiplexing workflows. J. Proteome Res 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00899 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lito P, Solomon M, Li L-S, Hansen R & Rosen N Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science 351, 604–608 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janes MR et al. Targeting KRAS mutant cancers with a covalent G12C-specific inhibitor. Cell 172, 578–589 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwiatkowski N et al. Targeting transcription regulation in cancer with a covalent CDK7 inhibitor. Nature 511, 616–620 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Browne CM et al. A chemoproteomic strategy for direct and proteome-wide covalent inhibitor target-site identification. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 191–203 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lanning BR et al. A road map to evaluate the proteome-wide selectivity of covalent kinase inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol 10, 760–767 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haapalainen AM et al. Crystallographic and kinetic studies of human mitochondrial acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase: the importance of potassium and chloride ions for its structure and function. Biochemistry 46, 4305–4321 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davies TG & Hyvönen M Fragment-based Drug Discovery and X-ray Crystallography (Springer, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erlanson DA, Davis BJ & Jahnke W Fragment-based drug discovery: advancing fragments in the absence of crystal structures. Cell Chem. Biol 26, 9–15 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fan CH et al. O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase as a promising target for the treatment of temozolomide-resistant gliomas. Cell Death Dis. 4, e876 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma S et al. Role of MGMT in tumor development, progression, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Anticancer Res. 29, 3759–3768 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagel ZD et al. Fluorescent reporter assays provide direct, accurate, quantitative measurements of MGMT status in human cells. PLoS ONE 14, e0208341 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beharry AA, Nagel ZD, Samson LD & Kool ETK Fluorogenic real-time reporters of DNA repair by MGMT, a clinical predictor of antitumor drug response. PLoS ONE 11, e0152684 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Du G et al. Structure-based design of a potent and selective covalent inhibitor for SRC kinase that targets a P-loop cysteine. J. Med. Chem 63, 1624–1641 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gurbani D et al. Structure and characterization of a covalent inhibitor of Src kinase. Front. Mol. Biosci 7, 81 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campaner E et al. A covalent PIN1 inhibitor selectively targets cancer cells by a dual mechanism of action. Nat. Commun 8, 15772 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dubiella C et al. Sulfopin, a selective covalent inhibitor of Pin1, blocks Myc-driven tumor initiation and growth in vivo. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.03.20.998443 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sears RC The life cycle of c-Myc: from synthesis to degradation. Cell Cycle 3, 1131–1135 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nam J et al. Disruption of the Myc-PDE4B regulatory circuitry impairs B-cell lymphoma survival. Leukemia 33, 2912–2923 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carter AJ et al. Target 2035: probing the human proteome. Drug Discov. Today 24, 2111–2115 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]