Key Points

Question

What have been the range of concerns and the sources of distress among health care workers in Canada as the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved?

Findings

In this qualitative study of a public online COVID-19 forum available for 21 555 employees in a university health network, common concerns relating to the pandemic included risks of contamination, appropriate personal protective equipment, and worker safety. Although these concerns manifested as individual distress, they also intersected with and were reflective of concerns relating to health care institutions’ policies, communication practices, and politics.

Meaning

The findings suggest that a mismatch between institutional sources of concern and individual-level interventions may affect the uptake of mental health supports even as the level of distress remains high.

Abstract

Importance

Mental health and coping difficulties among health care workers (HCWs) have been reported during pandemics and particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective

To examine sources of distress and concern for HCWs in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this qualitative study, a critical discourse analysis was performed of questions posed by HCWs to hospital senior leadership between March 16, 2020, and December 1, 2020, through an online employee forum as part of a larger mixed-methods evaluation of a stepped-care mental health support program for HCWs at 1 of Canada’s largest health care institutions. Questions could be submitted online anonymously in advance of the virtual forums on COVID-19 by any of the University Health Network’s 21 555 employees, and staff members were able to anonymously endorse questions by upvoting, indicating that an already posed question was of interest.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Themes, text structure, and rhetorical devices used within the questions were analyzed, taking into consideration their larger institutional and societal context.

Results

Unique individual views of the forums ranged from 2062 to 7213 during the study period. Major individual-level concerns related to risks of contamination and challenges coping with increased workloads as a result of the pandemic intersected with institutional-level challenges, such as feeling or being valued within the health care setting and long-standing stratifications between types of HCWs. Concerns were frequently reported in terms of calls for clarity or demands for transparency from the institutional leadership.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this qualitative study suggest that larger institutional-level and structural concerns need to be addressed if HCWs are to be engaged in support and coping programs. Potential service users may be dissuaded from seeing their needs as being met by workplace mental health interventions that solely relate to individual-level concerns.

This qualitative analysis uses an online COVID-19 forum available to employees at a large health care institution to examine sources of distress and concern for health care workers in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

With ongoing social and economic restrictions, stay-at-home orders, and an increasingly burdened health care system, the COVID-19 pandemic has been an affront to the mental well-being of many individuals.1,2 Among health care workers (HCWs), adverse psychological outcomes, including anxiety, depression, insomnia, and burnout, have been widely reported.3,4 In areas with high COVID-19 exposure and case volume, HCWs are especially likely to experience distress.5 Extensive pandemic media coverage and the widespread use of social media may also contribute to perceptions of risk and difficulties coping.6 Despite this, the uptake of supports by HCWs has remained limited even when these are offered at no or low cost.7 Moreover, to our knowledge, no evidence-based interventions for HCWs during pandemic events were evaluated before the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent Cochrane review8 suggests that, in general, resilience-promoting training programs for HCWs have little or no effect on anxiety, well-being, or quality of life and provide only low-certainty evidence for subjective improvements in perceptions of resilience and depression. A consistent mismatch remains between high levels of distress among HCWs and low-quality evidence for how to manage this situation.7 During the second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, contending with the range of perpetuating factors that contributed to mental distress among HCWs became a challenge. In this qualitative study, we sought to understand the range of concerns and sources of distress among HCWs at the University Health Network (UHN) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, as the COVID-19 pandemic evolved and asked how these concerns might intersect with one another in the institutional context.

Methods

Overview

In this qualitative study, as 1 component of a mixed-methods evaluation of an internal HCW mental health support program at UHN (the UHN COVID CARES program), we conducted a critical discourse analysis (CDA) of a series of online open forums (virtual forums) hosted by senior hospital leadership. The eMethods in the Supplement gives additional details. The study was approved by the UHN Quality Improvement Review Committee and received a formal waiver from research ethics board review because this study was undertaken for the purposes of program evaluation and quality improvement. A written informed consent process was still performed for all interviews. Data were deidentified at the time of transcription (eTable in the Supplement). This study followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) reporting guideline.9

Critical discourse analysis is a qualitative method that enables analysis of associations among language, text, talk, power, and culture; it examines vocabulary, grammar, rhetoric, and text structure within a particular social context.10 The method is used to evaluate how text and talk are produced, circulated, distributed, and consumed.11 The function of language to shape public perceptions of issues is recognized and the discourse is considered as both constitutive of and constituted by social practices.12 Although communicative expression is generated at an individual level, CDA can be used to evaluate this within a larger social, cultural, and political context.

The virtual forums that we examined have been hosted regularly during the COVID-19 pandemic as part of an ongoing communication tool between senior leadership and the 21 555 staff members who work at UHN, a large, multisite health care setting (Table 1). Any staff member can submit a question or concern related to the COVID-19 pandemic through an online platform (slido.com). Staff may submit as many questions to as many forums as they desire, although each question is not read aloud at a virtual forum. Questions submitted in advance of the live-streamed event are reviewed and prioritized by leadership and responded to on camera through a live-streamed video posted to a YouTube channel and maintained for later viewing. One feature of the forums has been upvoting: questions can be endorsed anonymously by other staff through online voting. We tracked the upvotes as an indicator of support for a given question because upvotes were used by the leadership team to prioritize questions for response and the process required engagement by staff in advance of a given forum to cast an upvote.

Table 1. Characteristics of University Health Network Staff and Employees.

| Characteristic | Staff and employees, No. |

|---|---|

| Paid employees | 16 978 |

| Administrative or clerical | 2253 |

| Allied health or health professions | 2922 |

| Information technology | 574 |

| Management | 923 |

| Medical professionals | 474 |

| Ontario Nurses' Association nurse | 3360 |

| Professional administrative | 1518 |

| Scientific | 589 |

| Support services | 2636 |

| Technologists or technicians | 1729 |

| Unpaid staff | 2897 |

| Administration | 255 |

| Technologists or technicians | 28 |

| Allied health or health professions | 85 |

| Scientific | 238 |

| Other | 2291 |

| Physicians | 1680 |

| Total staff and employeesa | 21 555 |

Excludes learners and volunteers.

This CDA was embedded within the needs assessment component of the UHN COVID CARES program evaluation. In brief, UHN is a large, publicly funded hospital network that provides tertiary and quaternary care in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The UHN COVID CARES program was developed as the first wave of the pandemic emerged in Canada (March to April 2020) and consists of (1) UHN CARES, a modified stepped-care model13 of individual mental health supports for HCWs; (2) Team CARES, proactive outreach that provides support to clinical areas affected by COVID-19; and (3) the provision of support to those working in support roles (wellness leads, social work staff, and spiritual care services). The qualitative needs assessment consisted of the CDA as well as interviews with a range of hospital staff, managers, and senior leadership team members. An ongoing mixed-methods program evaluation has also been performed. Findings have been reported through leadership channels in addition to contributing to changes within the UHN COVID CARES program.

Analysis

We examined all questions selected by leadership for the virtual forums from March 16 to December 1, 2020, and tracked the upvotes each question received. Themes were developed through an iterative close reading14 of the forum questions and their prioritization. We attended to the word choice, syntax and sentence structure, rhetorical style, and text features (such as bolded or words placed in all capital letters by the writer for emphasis). We paid particular attention to when questions were identified by the author as having been previously submitted to earlier forums. We also situated the forum questions within a broader institutional and societal context; at the start of each forum, the hospital chief executive officer provided a preamble, which we annotated. Comments relating to internal institutional events or external societal issues were cross-referenced with public sources of information, and on 2 occasions, the forums were reported by public media15,16 and included in our analysis.

At each iteration of our analysis, annotation was used to refine and link themes. In total, 4 iterations of thematic coding were performed, 2 of which entailed discussions among the authors regarding theme accuracy and completeness. The process concluded once no further modifications to the coding scheme were deemed necessary. Research memos and reflexive notes were tracked by one of us (S.G.B.). Forum questions were triangulated with the UHN COVID CARES needs assessment interviews.

Results

Forum Participants

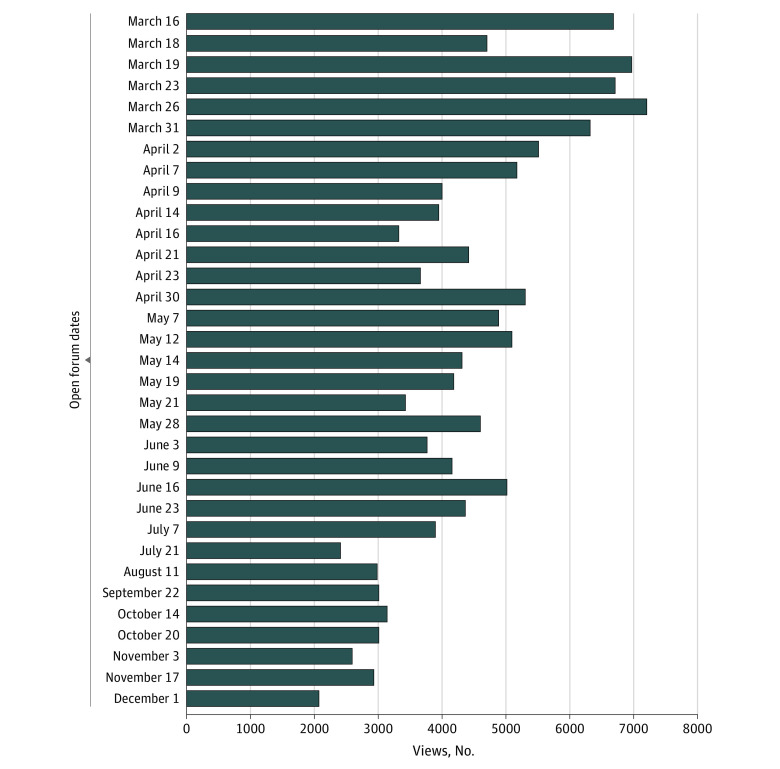

The virtual forum comments revealed that the forums were experienced by staff as an important communication tool and were widely viewed throughout the pandemic (Figure 1). Unique views of the forums (calculated for each forum on the day the data were extracted for analysis) ranged from 2062 to 7213 individuals. This range likely underestimates the total number of individuals viewing at least some part of each forum because these forums were sometimes viewed live by multiple individuals using a single computer (eg, in a nursing station). During the study period, forum questions were submitted and upvoted anonymously; thus, data on the writer of the question were not available unless this information was included in the submission.

Figure 1. Weekly Virtual Forum Views From March 16 to December 1, 2020.

Intersections of Individual-Level Concerns With Structural Issues and Institutional Transparency

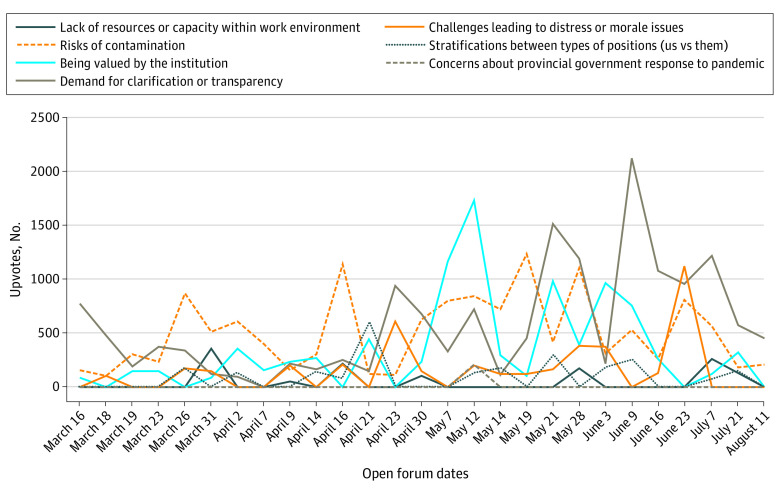

The tenor of early pandemic-related distress, as demonstrated through questions that used terms such as worried, fear, nervous, and anxious, simultaneously revealed fears relating to risks of infection or contamination with SARS-CoV-2 and concerns about a lack of transparency within the institution. The perceived risk to HCW safety was shown by individual concerns about COVID-19 infection that intersected with a broader context of structural and institutional concerns, including supply chain limitations, rapidly changing infection control policies, and increased workflow with a smaller number of HCWs. Requests for information regarding structural and institutional issues frequently engaged language relating to clarity vs perplexity and at times implied that information might have been withheld from staff (Figure 2). As elective and nonemergency procedures were halted and clinics shut down, patients in stable condition were moved to increase bed capacity, and staff redeployment was initiated as the UHN became involved with supporting long-term care facilities in the greater Toronto area, where most COVID-related deaths occurred during the first wave of the pandemic. These scenarios were sources of uncertainty and change that challenged HCWs’ ability to cope and subsequently became central topics in the forums (Table 2). Forum contributors asked explicitly how the institution would support the mental health of HCWs, framing conventional responses such as employee assistance programs, corporate wellness initiatives, and mindfulness practices (which were demonstrated on some virtual forums) as inadequate for meeting HCWs’ needs.

Figure 2. Discourse Analysis Themes and Upvotes by Week During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Toronto, Ontario, From March to August 2020.

Upvotes were defined as anonymous endorsement of questions and concerns by other staff through online voting. The first outbreak of COVID-19 occurred at Toronto Western Hospital in April; redeployment, April 23; pandemic pay (financial bonus to frontline, essential workers) removed from certain groups, May; redeployment and long-term care report, from May 14 to June 3; essential care partner policy introduction, June 9; and policies and statements regarding long-term care and Black Lives Matter, from June 23 to August 11.

Table 2. Qualitative Themes and Selected Virtual Forum Questions.

| Theme | Quotations (upvotes, No.) |

|---|---|

| Risk of contamination or safety concerns |

|

| Being valued by the institution |

|

| Stratifications between roles or positions (us vs them) |

|

| Demand for transparency or clarification |

|

| Explicit issues of mental distress or morale issues |

|

| Lack of resources or capacity in clinical environment |

|

Abbreviations: EAP, employee assistance program; HCW, health care worker; PPE, personal protective equipment; TGH, Toronto General Hospital; TTC, Toronto Transit Commission; TWH, Toronto Western Hospital; UHN, University Health Network.

Early concerns about the risks of contamination were also framed in relation to concerns about transparency. Such questions typically had an assertive, interrogative rhetorical style and were often contextualized in relation to competing interpretations of the scientific evidence regarding the pandemic. Subsequent concerns about redeployment, workloads, and patient movement were also framed by explicit demands for transparency from senior hospital leadership or had implicit suggestions that information was being withheld from HCWs in the institution (Table 2). Individual-level concerns about safety, risk, and contamination intersected with institutional-level issues about workflow, staffing levels, and a perception that the pandemic was being used to push through larger, often unpalatable institutional changes that would have otherwise been subject to greater consultation and bidirectional input.

Concerns During the Second Wave of the Pandemic

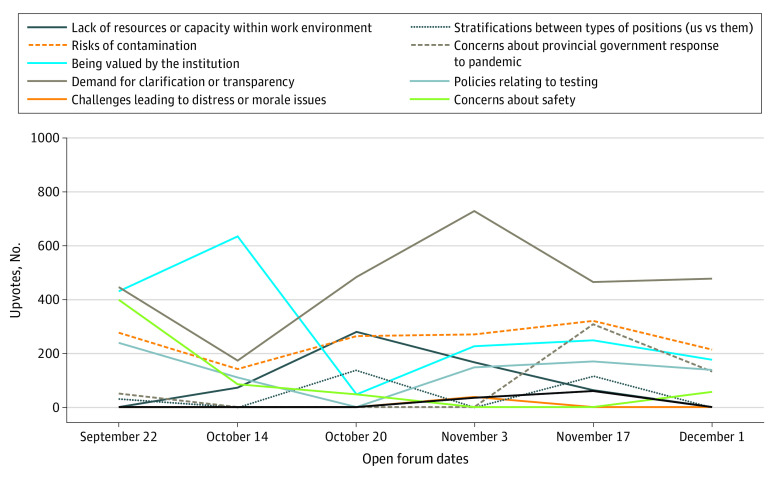

Intersecting fears about contamination and a perceived lack of transparency led to a broader set of concerns regarding the institutional context and culture, particularly regarding whether and how HCWs were valued within the institutions (Figure 3). As the pandemic evolved, sick leave policies, employee benefits, donations of food and free parking for hospital workers, and which groups of HCWs were eligible for pandemic pay (financial bonus to frontline, essential workers) from the provincial government were addressed in the virtual forums. These topics reflected a broader set of concerns regarding the institutional culture and the valuing of HCWs. Of interest, a practice of providing a “shout-out” to team members or colleagues who were believed to deserve praise had been a practice early in the forums and then ceased to occur for a period. These shout-outs were reintroduced as the second wave progressed.

Figure 3. Discourse Analysis Themes and Upvotes by Week During the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Toronto, Ontario, From September to December 2020.

Upvotes were defined as anonymous endorsement of questions and concerns by other staff through online voting. Redeployment to long-term care was flagged from September 22 to October 24; vacation carryover policy announced, October; and Public Health Agency of Canada identified aerosols as transmission, November 3.

The forums decreased in frequency through fall 2020 as a second-wave surge of infections affected the region. Demands for clarification or concerns about transparent communication remained consistent, continuing to overlap with themes of risk, safety, and being valued within the institution. Explicit mental health concerns were flagged less frequently during the second wave, although when they were flagged, these concerns were placed in the context of workloads, burnout, and a perception of mismatch between corporate priorities and the demands of care provision placed on frontline workers.

Social and Structural Context and Expression of Concerns

Concerns reported by staff were further shaped by events both inside and outside the health care network. Early during the forum implementation, these expressions of concern related to social media representations of the pandemic, hospital disclosures about unit outbreaks, and external reports about infection and mortality rates in long-term care. Through June and July 2020, in line with world events, transparency concerns and how HCWs were valued mapped onto larger societal issues, such as anti-Black racism and the health care system’s role in this racism.17 In the second-wave forums beginning in September 2020, an increasingly broad set of themes intersected with HCW concerns about transparency and being valued, including how the hospital system interfaced with governmental policy, particularly as the provincial government was seen to be failing to follow the suggestions of its medical advisers.18 Procedures relating to prioritization of COVID-19 vaccination eligibility at the provincial level became prominent, as did comments and criticisms regarding the enforcement of public restrictions, which arose in relation to challenges regarding workloads, fatigue, and burnout.

Discussion

In this qualitative study, similar to the published literature,19 early themes of distress in the UHN’s open forums were reported regarding personal protective equipment and worker safety. These concerns were not only associated with individual anxieties about contamination. High levels of concern involved uncertainties about viral transmission because of overstretched hospital capacities and excessive workloads, disrupted personal protective equipment supply chains, and how these disruptions would be managed in the context of a rollout of widespread social and economic restrictions.1,20 Also similar to the published literature21 was the evolution of these concerns as the pandemic evolved; sources of distress shifted to include burnout, fatigue, and moral injury associated with the conditions under which care was being provided. During each wave, forum contributors made reference to the limitations of typical or conventional approaches to HCW support, such as employee assistance programs and the promotion of mindfulness practices through wellness initiatives. The perception of these as stopgap measures and inappropriate to the nature of many HCW concerns was echoed in the qualitative interviews conducted as part of the UHN COVID CARES needs assessment and program evaluation.

In both the COVID-19 pandemic and previous pandemics, such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic, transparency and trust in the institutional setting were identified as key elements to managing fear and uncertainty.21 Trust in leadership has also been identified as a component of organizational culture that contributes to mental health outcomes among HCWs.22 Of importance, institutional sources of distress for HCWs at the UHN occurred in the context of a hospital-wide move to an incident management system. Sometimes referred to as a command and control approach, the incident management system is a top-down decision model with limited opportunities for feedback.23 At the UHN, this model was implemented within a larger context of executive leadership restructuring, which may have enhanced the scale of concerns about transparency and trust. Despite the forums being implemented to increase 2-way communication between leadership and staff, decisions about the forums (eg, changes in format) remained opaque, such that tensions surrounding transparency and trust were understood as important and central themes modeled within the forums’ processes and content.

Topics raised in the virtual forums reflected HCWs’ sense of how they were valued. The sense of being valued likewise intersected with concerns regarding transparency and trust in the institution. As indicated in the virtual forums, distress relating to these intersecting issues may have contributed to burnout and the loss of meaning within one’s work during the pandemic. This finding is similar to that reported in the literature24 on the interrelations among moral injury, self-efficacy, and loss of trust in health care institutions. This finding also reflects the ways in which distress and coping can be hindered or facilitated within a given organizational culture, particularly through leadership practices, group behaviors and relationships, and communication and participation.22 Notably, the virtual forums not only provided information about the institutional culture through the themes but also contributed to how that culture was shaped.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has strengths. The analysis provided a novel way of understanding the intersections of individual- and institutional-level challenges experienced by HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach allowed the exploration of topics of concern not easily captured by the validated scales and quantitative measures typically used to survey HCWs’ mental health and coping. A strength of the CDA method was the capacity for making conclusions about the relationships between institutional actors and HCWs. The virtual forums were part of the way in which these relationships were structured.

This study also has limitations. Certain groups of employees may not have had access to technology in their work environment, which may have curtailed their ability to engage with the virtual forums. Although the virtual forums were available for viewing and questions could be submitted to slido.com through the external (public-facing) institutional website, this process would require time, computer literacy, and access to technology at home to be used by those without access in their work role. Moreover, many other aspects of the forums (eg, links, summaries of responses, and discussion of the forum content) were often performed by internal all-user emails. During at least some of the study period, not all employees had an institutional email address. The disparities in access to the virtual forums as a communication tool may demonstrate reliability with regard to the themes of stratifications in types of positions (us vs them) and being valued in the institution.

This analysis was also limited by a lack of knowledge about the individuals who posed questions to the forum. Therefore, how this analysis might inform supports for particular populations of HCWs should not be overstated, and generalizations should not be made about the experience of distress by any given type of HCW. The use of methods such as CDA in concert with other approaches (quantitative or qualitative) when applying a CDA to program development would be valuable.

Qualitative research is marked by its inductive analytic practices and by the way in which multiple layers of meaning and interpretation can be explored in a single data set.25 The themes described in this article are not the only possible interpretation of the CDA data. Approaching the data set with a different research question would likely yield different themes. However, this study provided an analysis of 1 layer of meaning. At this stage, the analysis only briefly considered the response of leadership to questions. An analysis of the dynamics of question and response would be a valuable subject of further study and would likely yield further findings on the role of leadership and communication in organizational culture.

Conclusions

Supports for HCWs are typically designed as individual-level interventions; however, in this study, institutional-level stressors also affected HCW distress and coping and intersected with individual-level concerns. The most notable concerns included the ways in which institutional practices conferred or denied value to HCWs and the intersection of fears about worker safety with broader concerns regarding institutional transparency. When staff are using all their waning energy to perform their duties,26 reaching out for support may seem like another untenable task, and accessing services is less likely to occur if supports appear as though they fail to align with the source of concern.7,27 Maintaining the well-being of a dedicated, effective, and energetic health care workforce may involve addressing institutional challenges in addition to individual symptoms.

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable. Breakdown of Qualitative Interview Participants within the UHN COVID CARES Program Evaluation

References

- 1.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510-512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Usher K, Durkin J, Bhullar N. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(3):315-318. doi: 10.1111/inm.12726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsamakis K, Rizos E, Manolis AJ, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on mental health of healthcare professionals. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19(6):3451-3453. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vizheh M, Qorbani M, Arzaghi SM, Muhidin S, Javanmard Z, Esmaeili M. The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;1-12. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00643-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spoorthy MS, Pratapa SK, Mahant S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102119. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller AE, Hafstad EV, Himmels JPW, et al. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113441. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunzler AM, Helmreich I, Chmitorz A, et al. Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7(7):CD012527. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012527.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245-1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dijk TA. Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse Soc. 1993;4(2):249-283. doi: 10.1177/0957926593004002006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blommaert J, Bulcaen C. Critical discourse analysis. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2000;29:447-466.

- 12.Smith JL. Critical discourse analysis for nursing research. Nurs Inq. 2007;14(1):60-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2007.00355.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards DA. Stepped care: a method to deliver increased access to psychological therapies. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(4):210-215. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culler J. The closeness of close reading. ADE Bull. 2010;149:20. doi: 10.1632/ade.149.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser T. Anonymous online forum reveals Toronto hospital workers’ fears, grievances. Published March 29, 2020. Accessed May 2, 2021. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2020/03/29/anonymous-online-forum-reveals-toronto-hospital-workers-fears-grievances.html

- 16.Power L. Toronto healthcare workers are still paying for parking at local hospitals. Published March 30, 2020. Accessed May 2, 2021. https://www.blogto.com/city/2020/03/toronto-healthcare-workers-paying-for-parking-hospitals/

- 17.Paul DW Jr, Knight KR, Campbell A, Aronson L. Beyond a moment: reckoning with our history and embracing antiracism in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1404-1406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herhalt C. Ford denies not listening to health officials who called for stricter restrictions. Published November 12, 2020. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/ford-denies-not-listening-to-health-officials-who-called-for-stricter-restrictions-1.5185803

- 19.Rosenbaum L. Facing COVID-19 in Italy: ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1873-1875. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williamson V, Murphy D, Greenberg N. COVID-19 and experiences of moral injury in front-line key workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2020;70(5):317-319. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spalluto LB, Planz VB, Stokes LS, et al. Transparency and trust during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(7):909-912. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bronkhorst B, Tummers L, Steijn B, Vijverberg D. Organizational climate and employee mental health outcomes: a systematic review of studies in health care organizations. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(3):254-271. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Londorf D. Hospital application of the incident management system. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1995;10(3):184-188. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00041984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borges LM, Barnes SM, Farnsworth JK, Bahraini NH, Brenner LA. A commentary on moral injury among health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S138-S140. doi: 10.1037/tra0000698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mason J. Qualitative Researching. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trappey BE. Running on fumes. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1157-1158. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e15-e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable. Breakdown of Qualitative Interview Participants within the UHN COVID CARES Program Evaluation