Abstract

There has been little published literature examining the unique communication challenges older adults pose for health care providers. Using an explanatory mixed-methods design, this study explored patients’ and their family/caregivers’ experiences communicating with health care providers on a Canadian tertiary care, inpatient Geriatric unit between March and September 2018. In part 1, the modified patient–health care provider communication scale was used and responses scored using a 5-point scale. In part 2, one-on-one telephone interviews were conducted and responses transcribed, coded, and thematically analyzed. Thirteen patients and 7 family/caregivers completed part 1. Both groups scored items pertaining to adequacy of information sharing and involvement in decision-making in the lowest 25th percentile. Two patients and 4 family/caregivers participated in telephone interviews in part 2. Interview transcript analysis resulted in key themes that fit into the “How, When, and What” framework outlining the aspects of communication most important to the participants. Patients and family/caregivers identified strategic use of written information and predischarge family meetings as potentially valuable tools to improve communication and shared decision-making.

Keywords: communication, geriatrics, patient perspectives/narratives, patient satisfaction

Introduction

The past 20 years have seen the emergence of patient and family centered care (PFCC) in both academic literature and medical training programs (1 –4). In the PFCC approach, patients and families are considered partners in their care and work with the health care professional team to develop care plans specific to their needs. Effective communications are essential to the PFCC–health care provider team partnership.

The literature examining the role of communication in health care suggests it is fundamental to successful clinical encounters and is the number one driver of patient experience (5 –8). Additionally, this research suggests the quality of communication between patients and physicians/nurses can improve adherence to recommended treatment, patient safety, and quality of care (9 –11). As evidence mounts for improving communication practices in health care encounters, it could be argued that nowhere is it more important than in the interaction between physicians/nurses and geriatric patients and their families.

Currently, 6.4 million Canadians are older than 65 years, and this age-group will represent 1 in 5 Canadians by 2030 (12,13). The complexity of health care needs in an aging population demands that physicians and nurses have appropriate communication skills geared toward working with older adults and their families. Reports show that communication between older adults and their health care providers is often negatively impacted by factors including provider ageism attitudes, cognitive impairment or limited physical function of the patient, and the absence of an accompanying relative or caregiver at most appointments (14). It is therefore not surprising that research examining older adults’ perceptions of communication with physicians and nurses documents their dissatisfaction (7,14,15). This dissatisfaction highlights a striking need for studies to examine how communication between older adults and their health care providers can be optimized to improve the delivery of PFCC.

Aim and Objectives

Our aim was to study how patients and their family/caregivers perceive health care providers’ communication skills on our acute care inpatient Geriatric Medicine Unit (GMU), in order to continuously improve and to provide better PFCC. The objectives of the study were to (1) better understand patients’ and families’ experiences of current communication practices with physicians and nurses, (2) identify which aspects of communication are most important to them and influence their satisfaction with care received, and (3) determine ways of improving communication from their perspectives.

Methods

Design

This was a cohort observational study and used an explanatory mixed-methods approach with 2 cohorts. In the quantitative part of the study (part 1) with cohort 1, patients and family/caregivers completed surveys to gauge their perception of communication experiences with physicians and nurses on the GMU (16). These results guided the development of interview questions, included in Supplemental Appendix 1, to address objectives (2) and (3). In the qualitative part of the study (part 2) with cohort 2, patients and family/caregivers participated in guided interviews to determine which aspects of communication were most important to them, and how they felt communication practices could be improved.

Setting

The study took place on the GMU, which is a 24-bed acute care service in an urban academic health center in Canada. All patients admitted to this unit were identified by the inpatient Geriatrics consult service and were transferred from other services for a comprehensive geriatric assessment. The patients commonly have baseline multimorbidity, including cognitive impairment and mobility issues. The research team consisted of 2 occupational therapists (OTs), a physiotherapist, a social worker (who is also the research assistant), and a clinical nurse manager, all with specialized geriatrics training, led by 2 staff geriatricians.

Participants

Participants were purposefully recruited from the GMU between March and September 2018 and included 2 sources: patients and family/caregivers. Eligible patients had been admitted to the GMU for at least 5 days. Each patient’s cognitive status was screened using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test, administered by an OT or a medical resident as part of the patient’s routine care. Patients were excluded if they could not speak English, scored less than 20/30 on the MoCA, or did not have the capacity to make their own health care decisions as determined by the clinical judgment of the medical team. In instances where patients were deemed ineligible to participate, family/caregivers were invited to participate.

During part 1 (quantitative study), potential participants were identified by OTs within the patients’ circle of care, and verbal consent was obtained to be approached about the project at time of discharge by the clinical manager. The clinical manager on the GMU is not involved in the clinical care of the patients. During the manager’s routine visit with each patient on the day of discharge from the hospital, she presented more details about the study to consenting participants, answered questions, and obtained formal consent to participate. Those who consented to participate completed a short online survey prior to leaving hospital.

In part 2 (qualitative study), potential participants were identified by OTs within the patient’s circle of care and verbal consent was obtained to be contacted by the research assistant. The research assistant presented more details about this part of the study, answered questions, and obtained written consent to participate prior to the patient’s hospital discharge. Consented participants were contacted by the research assistant by telephone 4 weeks after discharge and if they were still interested, they were scheduled for a telephone interview. Only 2 attempts were made to reach any potential participants, leaving messages each time.

Surveys

Surveys were based on a modified version of the Patient-Healthcare Provider Communication Scale (PHCPCS), which was validated by Salt et al in 2012 (16). This 21-item survey measures participant perception of communication between patients and health care providers and was adapted, with permission, to allow for use in both patients and family/caregivers. Participants responded to each item in the survey by rating the frequency with which they experienced the attribute as Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Very Often, or Always. Additionally, an open-ended question was added as the last item in the survey for family/caregivers allowing them to address any additional concerns. The survey responses addressed participants’ experience communicating with health care providers on GMU.

Participants in part 1 completed an online survey using a wireless tablet computer with assistance from the clinical manager prior to discharge. The clinical manager read the survey items to each consented participant and entered the participant’s responses into the tablet computer. Responses were collected anonymously using the Survey Monkey platform (SurveyMonkey Canada Inc), and all data were subsequently exported into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Canada) for analysis. Analysis of survey results yielded the themes used to guide development of part 2 interview questions.

Interviews

Semistructured telephone interviews were conducted by the research assistant. Interview questions explored patients’ and family/caregivers’ experiences of communication practices on the GMU, aspects of communication most important to their overall satisfaction with the care, and ways to improve communication practices from their perspective (Supplemental Appendix 1). The research assistant used the guiding questions (Supplemental Appendix 1) to conduct the interviews but was allowed to ask additional clarifying questions of the participants depending on participant responses. Interviews lasted between 20 and 120 minutes, were audio-recorded, anonymized, and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The survey results were summarized using descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations (SD), in Microsoft Excel. Survey items were scored using a 5-point scale: 0 (Never), 1 (Rarely), 2 (Sometimes), 3 (Very Often) to 4 (Always). Some items were reverse scored to ensure that higher scores indicated better patient- or family/caregiver-provider communication. The total score for each survey was calculated and then mean scores (and SD) presented, with a higher score indicating a better perception of the quality of patient- or family/caregiver-health care provider communication as per Salt et al (17). The mean scores and SDs for each survey item for the patient surveys and family/caregivers surveys were calculated. Survey items scored at or below the lowest 25th percentile were identified for each group of participants to indicate possible areas of communication experiences requiring improvement.

Two investigators (SH and VP) independently coded 2 interview transcripts and then met to discuss codes and develop a coding strategy. The remainder of the interviews were coded by VP and reviewed by SH. Following coding of the interviews, SH and VP met to categorize codes into emerging themes. The final themes were reviewed by the research team for agreement.

Results

During the 2018 to 2019 fiscal year, the average length of patient stay on the GMU was around 16 days and the average age of patients was 83.5 years. Between March 1 and September 30, 2018, of the roughly 266 patient admissions/discharges that occurred on the GMU, a total of 33 patients and family/caregivers were enrolled in the study (20 participants for part 1 and 13 participants for part 2). Thirteen patients and 7 family/caregivers completed the part 1 surveys. The mean total survey score for patients was 68.62 of 88 (SD 10.87), and the mean total survey score for family/caregivers was 75.14 of 84 (SD 8.80), possibly indicating a better perception of the communication experience by family/caregivers although this cannot be said with certainty due to the small and unequal sample size between the 2 groups of participants. With regard to the patient surveys, the items scored at or below the lowest 25th percentile were “The physician and nurses are in a hurry when they see me,” “The physician and nurses present me with all of the treatment options,” “The physician and nurses explain my health condition in detail,” “The physician and nurses involved me in decisions about my care,” “The physician and nurses answer my questions about my health,” and “I am able to make health related decisions because of the information provided by my physician and nurses” (Table 1.1). With regard to the family/caregivers surveys, the items scored at or below the lowest 25th percentile were “My loved one is able to make health related decisions because of the information provided by their physician and nurses,” “The physician and nurses present my loved one with all of the treatment options,” “The physician and nurses involve my loved one in decisions about their care,” “The physician and nurses are in a hurry when they are with my loved one,” and “The physician and nurses are knowledgeable about my loved one’s health condition” (Table 1.2). As indicated by these results, similar areas of the communication experiences with the health care providers on our unit were perceived by both groups of respondents as poorer and possibly requiring improvement. The respondents perceived that their communication experience with the health care providers felt hurried, the amount of information shared with the patients regarding treatment options and nature of health conditions were suboptimal, as was the degree of patient involvement in shared decision-making.

Table 1.1.

Patient Survey Items With Mean Score and Standard Deviation.

| Item | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| The physician and nurses try to find answers to my health problems. | 3.23 (0.60) |

| The physician and nurses take my health concerns seriously. | 3.46 (0.66) |

| The physician and nurses explain my health condition in detail. | 2.77 (0.93) |

| The physician and nurses pay attention to what I say about my health. | 3.08 (1.12) |

| The physician and nurses ask me questions so that he/she understands my health problems. | 3.15 (0.90) |

| The physician and nurses present me with all of the treatment options. | 2.31 (0.95) |

| The physician and nurses are concerned about my understanding of my health. | 3.08 (0.76) |

| The physician and nurses approach my treatment with a positive attitude. | 3.23 (0.73) |

| The physician and nurses are knowledgeable about my health condition. | 3.08 (0.95) |

| The physician and nurses answer my questions about my health. | 2.92 (0.95) |

| I am able to make health-related decisions because of the information provided by my physician and nurses. | 3.00 (0.71) |

| The physician and nurses are honest with me about my health. | 3.23 (0.73) |

| The physician and nurses understand my concerns about my health condition. | 3.00 (0.82) |

| The physician and nurses are patient. | 3.54 (0.78) |

| The physician and nurses treat me the way they would want to be treated. | 3.31 (0.75) |

| The physician and nurses treat me with kindness. | 3.62 (0.65) |

| I feel comfortable telling my physician and nurses about my health concerns. | 3.54 (0.66) |

| The physician and nurses involved me in decisions about my care. | 2.85 (0.80) |

| The physician and nurses are in a hurry when they see me.a | 2.15 (1.07) |

| The physician and nurses have been rude to me.a | 3.54 (0.66) |

| The physician and nurses make me feel that I am bothering him/her with my medical concerns.a | 3.08 (0.86) |

| I have avoided telling my physician and nurses about my health concerns because I am afraid of what they will think or say.a | 3.46 (0.88) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Questions that were reverse scored.

Table 1.2.

Caregiver Survey Items With Mean Score and Standard Deviation.

| Item | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| The physician and nurses try to find answers to my loved one’s health problems. | 3.71 (0.49) |

| The physician and nurses take my loved one’s health concerns seriously. | 3.86 (0.38) |

| The physician and nurses explain my loved one’s health condition in detail. | 3.57 (0.79) |

| The physician and nurses pay attention to what my loved one says about their health. | 3.71 (0.76) |

| The physician and nurses ask my loved one questions so that he/she understands their health problems. | 3.57 (0.79) |

| The physician and nurses present my loved one with all of the treatment options. | 3.00 (1.00) |

| The physician and nurses are concerned about my loved one’s understanding of their health. | 3.86 (0.38) |

| The physician and nurses approach my loved one’s treatment with a positive attitude. | 4.00 (0) |

| The physician and nurses are knowledgeable about my loved one’s health condition. | 3.43 (0.79) |

| The physician and nurses answer my loved one’s questions about their health. | 3.57 (0.79) |

| My loved one is able to make health-related decisions because of the information provided by their physician and nurses. | 2.43 (1.81) |

| The physician and nurses are honest with my loved one about their health. | 3.71 (0.76) |

| The physician and nurses understand my loved one’s concerns about their health condition. | 3.57 (0.79) |

| The physician and nurses are patient with my loved one. | 4.00 (0) |

| The physician and nurses treat my loved one as they would want to be treated. | 3.57 (0.79) |

| The physician and nurses treat my loved one with kindness. | 4.00 (0) |

| The physician and nurses feel comfortable about telling my loved one’s health care provider about their health concerns. | 3.71 (0.49) |

| The physician and nurses involve my loved one in decisions about their care. | 3.00 (1.53) |

| The physician and nurses are in a hurry when they are with my loved one.a | 3.14 (1.21) |

| The physician and nurses have been rude to my loved one.a | 4.00 (0) |

| The physician and nurses make my loved one feel that they are bothering him/her with their medical concerns.a | 3.71 (0.76) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Questions that were reverse scored.

Open-ended family/caregivers’ responses at the end of the survey yielded mixed results. Two caregivers stated they had no concerns over health care provider communication practices. Three caregivers voiced concerns about communication practices. One listed limited physician availability as a barrier to communication, while the other 2 caregivers cited concerns of receiving mixed messages or incomplete information from health care providers.

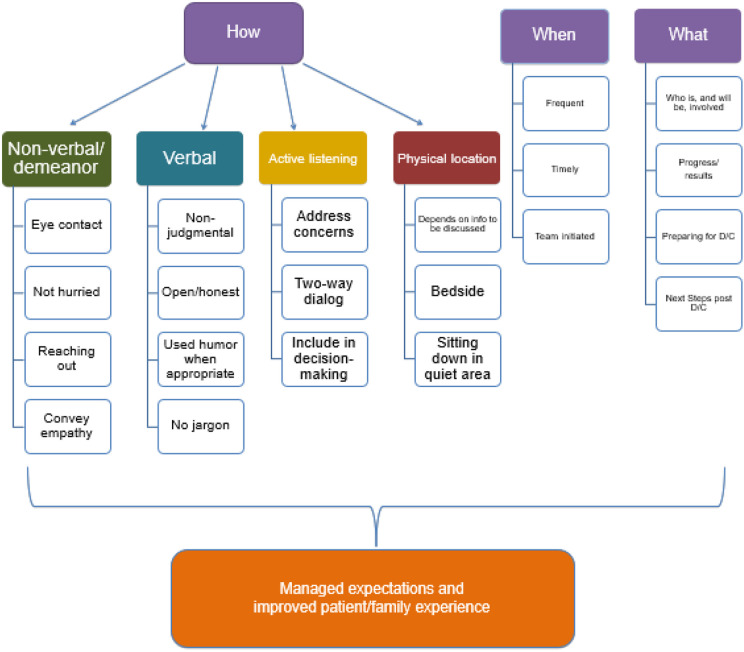

Thirteen people consented to be contacted for the part 2 telephone interviews and only 6 successfully participated. The reasons for nonparticipation in the interviews included inability to be reached for the interview and withdrawal of consent. Two participants were patients and 4 were family/caregivers. Results from thematic analysis of interview transcripts are summarized in Figure 1, and sample quotations from the interviews illustrating key themes are presented in Tables 2 to 4. Themes identified by participants as important aspects of communication impacting satisfaction with care included “How” the healthcare team communicated, “When” they communicated, and “What” they communicated with patients and family/caregivers.

Figure 1.

Flowchart summarizing the aspects of communication important to patients and caregivers and influenced overall satisfaction with care.

Table 2.

Themes Relating to “How” Participants Want to be Communicated With.

| Theme | Example |

|---|---|

| Nonverbal | Positive: “Let’s just say his bedside manner and his openness were conducive to asking questions and getting really good responses.” “Well she sat down and looked right at me, she reached out to me a couple of times to reassure me or to communicate compassion about how I was feeling, she just listened really intently and responded to specific questions that I asked.” Negative: “My dad was always aware of this was that they’re rushed.” |

| Verbal | Positive: “So he shared his own personal experience with his father being in a similar situation so there was an immediate trust and empathy…” “He did not appear to be judgmental, I think he was gentle and used humor well and I enjoyed that.” “They spoke to you. They didn’t speak down to you, they spoke directly about the problem.” |

| Active listening | Positive: “I’m not quite sure how to explain this but definitely more of an empathetic approach and again part of that is listening and the dialogue what have you.” “I mean where you’re not just giving results but you’re really trying to help the patient and their family [understand] what is going on and what are the different factors involved.” |

| Location | Negative: “I don’t think you should ever tell somebody that their mother is dying standing in a hall corridor.” |

Table 3.

Themes Relating to “When” Participants Feel Communication Is Important.

| Theme | Example |

|---|---|

| Frequent | Positive: “We generally saw the doctors at least once a day if not more and obviously the nurses were coming in every hour. There was always communication with the doctors for sure.” “But I do recall having a very good rapport, a lot of discussions with the doctor…” |

| Timely | Positive: “They were really good with my mother. If we needed to speak with them, they were always available.” Negative: “My dad always talked about having to wait, to wait for everything.” |

| Team initiated | Positive: “Even just stopping me in the hall when I was in visiting my mom. Just having a quick chat, talking about progress, her current state and talking about his insight into the day’s activities and sort of what the next steps were going to be.” Negative: “I would say taking more initiative to share information with us…” “The issue that I had was that really nobody came to us with the information…the concern is, is that if there is someone there without other family members advocating for them or people who are confident enough to go and ask all of the hard questions I don’t know if the information would be offered if that makes sense.” |

Table 4.

Themes Relating to “What” Participants Want Communicated.

| Theme | Example |

|---|---|

| Who is and will be involved in care | Positive: “We would always see who was on staff every day, the name would be posted which was great.” Negative: “Maybe introducing the replacement nurses that type of thing. That’s a really personal thing because I was really there a lot and I wanted to know who was taking care of my mom and who I could go to for help if needed.” |

| Progress and results | Positive: “There was a lot of one-on-one explanations of the care that was being received by my mom and a lot of stuff sort of outside of that that provided more general information about the path that I was going to be going down with my mom. That was useful, I don’t know how I would have started this process without having that information.” Negative: “It would have just been nice to get an overview of exactly…well when you’re living it, it’s a blur. So three weeks later it would have been kind of good to review from the beginning to the end, a quick synopsis of what exactly they found, how you can move forward.” |

| Discharge plan | Positive: “…leading into a final wrap-up/discharge, hey these are the things you should do like contact [homecare services] or have you made follow-up doctor appointments with x, or the sort of things that we may not remember to do. That’s the kind of stuff I was looking for and I got a lot of it.” Negative: “To be honest it would have been the final meeting just to have an overview of everything. I think honestly that would have made the experience a 10 [out of 10].” |

In terms of the “How” (examples in Table 2), participants identified verbal and nonverbal cues, active listening behaviors, and appropriate physical location as key components of good communication practices that they valued. They appreciated clinicians who made good eye contact, had an unhurried and empathic manner, and who used nonjudgmental, honest language that was easy to understand. Use of humor or appropriately reaching out with hand gestures helped convey empathy and sense of connection with the listener. They appreciated clinicians who asked questions to check for understanding and included them in decision-making. Physical environment where communication with health care providers took place was important to them as well, especially when disclosing bad news.

In terms of the “When” (Table 3), patients and family/caregivers indicated overwhelmingly that they want frequent and timely communication, especially when there is a test result to convey, a change in treatment plan, or a change in clinical status of the patient. Some participants felt they had to request information and wished that the health care providers would share information more proactively.

Regarding the “What” (Table 4), patients and family/caregivers appreciated knowing who would be involved in patient care, receiving regular updates of medical progress of the patient, and explanations of any test results and treatment options while being given clinical context. They wanted to be involved in discharge and follow-up planning. Use of written communication and family meetings were 2 modalities of information sharing that patients and family/caregivers found particularly beneficial to improving their understanding of what is happening.

Discussion

This observational study provides a novel description and understanding of the patients’ and family/caregivers’ perception of the communication practices on an acute care GMU. To our knowledge, this is the first study seeking to understand patients’ and family/caregivers’ perspectives and expectations of communication practices in this setting. Study part 1 results may be consistent with previous literature (7,14,15), in which family/caregivers perceive communication experiences with health care providers more positively than patients do generally but due to the small and unequal sample sizes of the 2 respondent groups, we cannot say this with certainty. Looking at the survey items scored in the lowest quartile (indicating perceived poorer communication areas), the similarities between how these items were scored by the 2 respondent groups indicate that these items likely reliably reflect the communication experiences with the health care providers on our unit despite the small sample size. These results showed that patients and family/caregivers alike perceived that the providers did not convey all the information that they needed or include the patients as partners in shared decision-making. Therefore, in order to improve their communication experience with health care providers on our unit, it is important for the health care providers to explicitly address adequacy of information sharing and ways to facilitate joint decision-making in the communication practices on our unit in order to provide high-quality PFCC. This finding is in line with two of the four core concepts of PFCC outlined by the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, namely Information sharing and Participation (18).

Study part 2 produced a key outcome of this study, namely the emergence and development of the “How, When, and What” thematic framework (Figure 1), which summarizes the aspects of high-quality communication most important to patients and family/caregivers in the acute care inpatient geriatric setting. This framework can be used by our program and other services as a potential starting point to evaluate and improve the delivery of PFCC. Increased patient satisfaction with care can be achieved by establishing clear patient and family expectations through open patient/caregiver–provider communication (6). Therefore, managing expectations plays a central role in successful use of the “How, When, and What” thematic framework.

The first theme that emerged from our study is the “How” to communicate with patients and family/caregivers. Participants felt that effective communication requires the provision of clear, accurate, and comprehensive information in an open and honest way, without the use of jargon. They also felt that it was acceptable for health care providers to use humor when appropriate to help alleviate their fear and anxiety. Finally, patients emphasized that it is the simple gestures of kindness and compassion, unhurried approach, and empathy that can most profoundly transform a stressful time.

The second theme is the importance of the “When” to communicate with patients and family/caregivers. Participants wanted frequent, timely, and proactive communication to keep them informed of their illness, progress, future care plans, and posthospital care. The importance of team-initiated, proactive communication was highlighted as being integral to patient involvement in decision-making. This is especially true because patients and family/caregivers may have difficulty advocating for themselves at times when they do not feel included in decision-making. Having health care providers they can trust to keep them informed, communicate information at a level they can understand, and explain to them all options of care clearly make them feel at ease and comfortable asking questions. These characteristics help to foster a collaborative environment where everyone’s contribution is valued and respected.

The third theme is “What” to communicate with patients and their family/caregivers. Participants indicated that they wanted to know who was going to be involved in their care, especially the allied health professionals beyond the nurses and physicians. This additional information helps them know who to potentially ask for help if they have a concern, which in turn may allow them to gain a sense of control over what happens to them in the hospital and help them improve connections and rapport with the care team. Patients and family/caregivers wanted timely information regarding their progress in hospital and test results, to start discussions around discharge planning early during the hospital admission, and be involved with care decision-making at all stages of hospitalization. All this information contributes to a better understanding of the care received by the patients during the hospitalization and better prepares them and their family/caregivers for a smoother transition from hospital to home on discharge. An analogy can be found on commercial airlines, where the availability of in-flight real-time display maps can improve a traveler’s understanding of where they are during their journey and contribute to their satisfaction with the travel experience (19).

Our study provided us with valuable insight into patient/caregiver-inspired ways to improve our current communication practices. Patients and family/caregivers consistently expressed the desire for more written and/or printed information to help improve retention of a communication session (Supplemental Appendix 2). For example, printed summaries would be useful to patients and family/caregivers in that they may help keep all parties on the same page, especially when the patients themselves may be unable to convey information to family/caregivers due to cognitive and physical or health challenges; all common scenarios in the geriatric inpatient setting. Written communication could also be used to aid patients and family/caregivers when conveying complex concepts to other family members and as a reference to clarify missed or misunderstood discussion points. Used appropriately, written information could help prepare patients or family/caregivers for what is to come (eg, agenda for a scheduled meeting, information regarding discharge preparation, educational material on advanced care planning before discussions with health care providers) in order to manage expectations and anxiety. Patients and family/caregivers also wanted a planned family meeting with the care team prior to discharge to review the hospital course and to learn what to expect afterward. They felt that this would provide an opportunity to fill information gaps, to verify their understanding of what happened during the hospital course, and to become aware of any remaining issues requiring action. This opportunity to allow patients and family/caregivers to ask any further questions can also improve patient experience. In the words of one participant referring to having such a meeting, “I think honestly that would have made the experience a 10 [out of 10].”

Future studies could consider the development of written communication tools to address patient/caregiver knowledge gaps, to help demystify the health care experience (eg, orientation to the inpatient ward, roles of different health care team members, etc) and to facilitate shared decision-making (eg, a 2-way bedside health care “diary,” where patients and family/caregivers could write down their questions for the health care providers, allowing health care providers to reply to their questions or indicate when they are available to speak to them). Another action item would be to develop a process that identifies which patients and their family/caregivers would benefit from a predischarge family meeting.

Limitations

This study was limited by a small sample size. The reasons for this are manifold, mostly owing to the acute care hospital environment and the nature of the patient population on our unit and partly due to study execution. As mentioned previously, the majority of the patients admitted on our unit have baseline multimorbidity, including cognitive impairment and mobility issues. They are admitted in hospital often due to a combination of new health problems and acute exacerbation of chronic conditions. Between the medical complexity of the patients and associated longer average length of stay, this is a stressful time for patients and their families/caregivers. The high proportion of patients with exclusion criteria, including cognitive impairment, as well as caregiving burnout among the family/caregivers are common barriers to research participation in this population and certainly affected our ability to recruit participants despite our best efforts. The entire project team was composed of clinical care providers who were trying to conduct the study while concurrently carrying out their clinical duties. These competing interests likely also negatively affected our ability to recruit more participants. The study was only carried out between March and September 2018 because these are the months when the physicians in the project team were not working on the GMU, thereby reducing potential bias and change in communication practices that may influence the objectivity of the outcome of the study. Due to these unique limitations of the study, the data collected may not reflect the opinions in the general geriatric patient population and limit its generalizability. However, the patterns of responses to the part 1 surveys were similar and the responses from the part 2 interview participants resulted in recurrent and actionable themes. In the absence of new participants and data, we are unable to comment on whether data saturation was reached. Another limitation is in the choice of the survey. The modified PHCPCS was originally validated in the rheumatoid arthritis population and has not been validated for use in the context of Geriatric Medicine patients. However, there are few validated tools measuring patient–health care provider communication and none that are specific to the perspectives of inpatient geriatric patients. Given that the PHCPCS was developed in an older population (average age 54 ± 13.9; range 21-83) living with chronic disease (16), we felt this tool was a reasonable option.

Conclusion

A key novel outcome of this study is the “How, When, and What” framework, which describes what patients and their family/caregivers consider as important aspects of communication with the health care providers in an acute care geriatric inpatient setting. Action items can be taken from the framework to improve communication and affect the delivery of PFCC. We showed that patients and family/caregivers are attuned to variations in the communication styles of health care providers and this impacts their experience of care quality. Furthermore, patients and family/caregivers identified the need to more actively involve them in the medical decision-making process. Strategic use of written information and predischarge family meetings may improve communication and shared decision-making.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735211034047 for Improving Communications With Patients and Families in Geriatric Care. The How, When, and What by Shirley Chien-Chieh Huang, Alden Morgan, Vanessa Peck and Lara Khoury in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-jpx-10.1177_23743735211034047 for Improving Communications With Patients and Families in Geriatric Care. The How, When, and What by Shirley Chien-Chieh Huang, Alden Morgan, Vanessa Peck and Lara Khoury in Journal of Patient Experience

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sylvia Pearce, Ashlee Barbeau, Vicki Thomson, and Eric Gervais for their support in project planning and participant recruitment.

Authors’ Note: This study was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board. Verbal and written informed consent were obtained from participants according to the study protocol approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board. All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the study protocol approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Quality & Patient Safety grant of The Ottawa Hospital Academic Medical Organization [grant number 2016-0763].

ORCID iDs: Shirley Chien-Chieh Huang, MD, MSc, MScHQ  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8196-911X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8196-911X

Lara Khoury, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0150-840X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0150-840X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Constand MK, Macdermid JC, Bello-haas VD, Law M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deen TL, Fortney JC, Pyne JM. Relationship between satisfaction, patient-centered care, adherence and outcomes among patients in a collaborative care trial for depression. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2011;38:345–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grob R. The heart of patient-centered care. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2013;38:457–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient-centered medicine. JAMA. 1996;275:152–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc SciMed. 2000;51:1087–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Street RL, Jr, Epstein RM. Key interpersonal functions and health outcomes: lessons from theory and research on clinician-patient communication. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; 2008:237–63. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peck BM. Age-related differences in doctor-patient interaction and patient satisfaction. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2011;2011:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ong LML, de Haes JCJM, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:903–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1516–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zolnierek KBH, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Statistics Canada. Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex. 2020. Accessed June 22, 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501

- 13. Government of Canada—Action for Seniors report - Canada.ca. 2014. Accessed June 22, 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/seniors-action-report.html#tc2a

- 14. Adelman RD, Greene MG, Marcia Ory DG. Communication between older patients and their physicians. Clin Geriatr Med. 2000;16:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans K, Robertson S. “Dr. Right”: Elderly women in pursuit of negotiated health care and mutual decision making. Qual Rep. 2009;14:409–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salt E, Crofford LJ, Studts JL, Lightfoot R, Hall LA. Development of a quality of patient-health care provider communication scale from the perspective of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Chronic Illn. 2012;9:103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salt E, Rayens MK, Frazier SK. Predictors of perceived higher quality patient-provider communication in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014;26:681–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson B, Abraham M, Conway J, Simmons L, Edgman-Levitan S, Sodomka P. Partnering with patients and families to design a patient-and family-centered health care system recommendations and promising practices. 2008. Accessed June 22, 2019. https://www.ipfcc.org/resources/PartneringwithPatientsandFamilies.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19. Torkashvand G, Stephane L, Vink P. Aircraft interior design and satisfaction for different activities; a new approach toward understanding passenger experience. Int J Aviat Aeronaut Aerosp. 2019;6:Art. 5. doi:10.15394/ijaaa.2019.1290 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735211034047 for Improving Communications With Patients and Families in Geriatric Care. The How, When, and What by Shirley Chien-Chieh Huang, Alden Morgan, Vanessa Peck and Lara Khoury in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-jpx-10.1177_23743735211034047 for Improving Communications With Patients and Families in Geriatric Care. The How, When, and What by Shirley Chien-Chieh Huang, Alden Morgan, Vanessa Peck and Lara Khoury in Journal of Patient Experience