Abstract

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are a rapidly developing class of materials that has been of immense research interest during the last ten years. Numerous reviews have been devoted to summarizing the synthesis and applications of COFs. However, the underlying dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC), which is the foundation of COFs synthesis, has never been systematically reviewed in this context. Dynamic covalent chemistry is the practice of using thermodynamic equilibriums to molecular assemblies. This Critical Review will cover the state-of-the-art use of DCC to both synthesize COFs and expand the applications of COFs. Five synthetic strategies for COF synthesis are rationalized, namely: modulation, mixed linker/linkage, sub-stoichiometric reaction, framework isomerism, and linker exchange, which highlight the dynamic covalent chemistry to regulate the growth and to modify the properties of COFs. Furthermore, the challenges in these approaches and potential future perspectives in the field of COF chemistry are also provided.

Keywords: covalent organic frameworks (COFs), dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC), modulation, mixed linker, sub-stoichiometric reaction, isomerism, linker exchange

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The concept of dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC) where reversible chemical reactions are carried out under thermodynamic control was proposed in the context of supramolecular chemistry and polymer chemistry two decades ago.1–4 The reversible nature of the reactions permits “error checking” and “proof-reading” in the generated dynamic combinatorial library (DCL) of interconverting components to give the thermodynamically most stable product under given conditions.5–8 In other words, in a reaction where DCC operates (Figure 1), it is the relative stability of the products (i.e. thermodynamic parameters) that decides the product distribution rather than the relative magnitudes of energy barriers of each pathway (i.e. kinetic parameters). Since both the thermodynamic and the kinetic parameters are the functions of a set of reaction factors, the reaction outcome is thus highly dependent on and also being controlled by the reaction conditions, such as temperature, pressure, concentration, catalyst, light, and other external stimuli. Besides, time is also an important factor as the kinetic parameters determine how long it would take for an equilibrium to be reached. The covalent bond formation and breaking typically show slow kinetics. These fascinating features make DCC play an important role in the synthesis of complex discrete molecular architectures like macrocycles and cage compounds.3

Figure 1.

Free energy profile illustrating thermodynamically (blue zone) and kinetically (green zone) controlled reactions. Double ended black arrows represent reversible reactions. Subscript K and T denotes the activation energy (ΔG‡) and the change of Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the kinetic and thermodynamic product formation reaction, respectively.

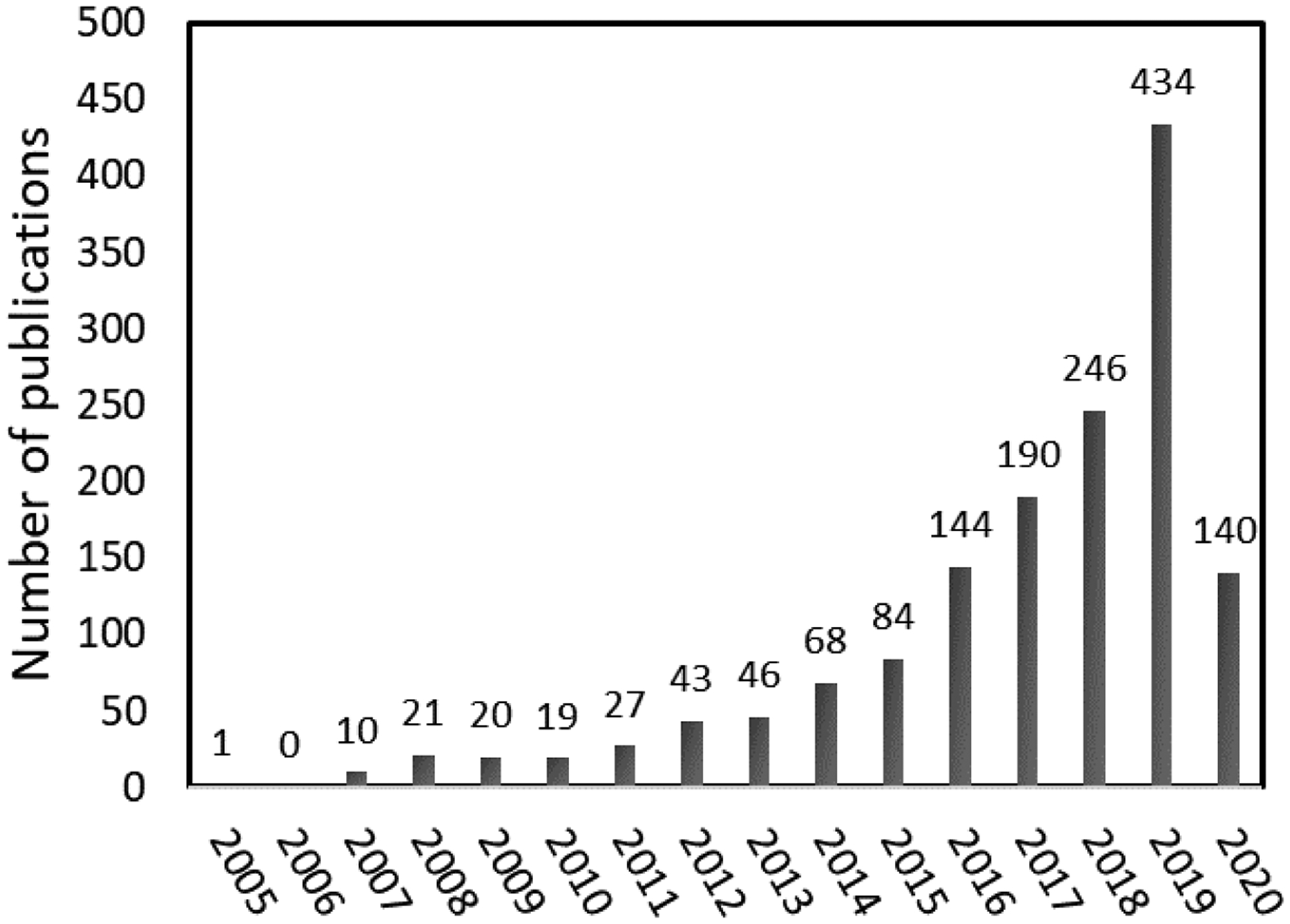

Expansion of the DCC concept to extended two dimensional (2D) and three dimensional (3D) frameworks, built on relatively rigid monomers with a predesigned topology diagram, led to the birth of covalent organic frameworks (COFs) pioneered by Yaghi and co-workers in 2005.9 This emerging class of crystalline porous materials has been continuously drawing the attention of researchers since. The increasing number of publications on COFs year by year is summarized in Figure 2. This rapidly growing field has been the subject of excellent review papers on the fundamental design and synthesis of COFs10–26 and there have been a number of more specialized reviews on COFs applications including catalysis,27–32 separation,33–35 sensing,36 energy storage,37–41 and biomedical42–46 among others47,48. Reversible reactions such as boronic acid trimerization,9 boronic acid and catechol condensation,9 imine condensation,49 hydrazone formation,50 azine formation,51 and imide formation52 among others are the first and also the most frequently used reactions to construct COFs; although more recently, irreversible reactions have been used to form COFs53–59. It is the reversible nature of the coupling reactions that allows a dynamic breaking and reformation of covalent bonds within the lattice at equilibrium which achieves the thermodynamic minima of the system. Thus, the network undergoes error checking and proof-reading to approach a crystalline structure which is the thermodynamically most stable product, instead of an amorphous polymer. This review does not intend to be comprehensive, and we focus on the dynamic aspects underlying the structure of COFs that have not been a fundamental clue for any of the published COF reviews, to the best of our knowledge. Following this basic idea, various synthetic strategies developed to regulate the growth and to modify the properties of COFs, including modulation to increase framework crystallinity, mixed linker/linkage to engineer structural complexity and functionality, sub-stoichiometric reaction to form unexpected topologies, framework isomerism in COFs, and post-synthetically linker exchange to de novo inaccessible COFs, will be discussed in detail in this review.

Figure 2.

Publications on COFs as of April 2020 (Data taken from Web of Science that used “covalent organic framework” or “covalent organic frameworks” in the title as the searching criteria).

1. Modulation approach

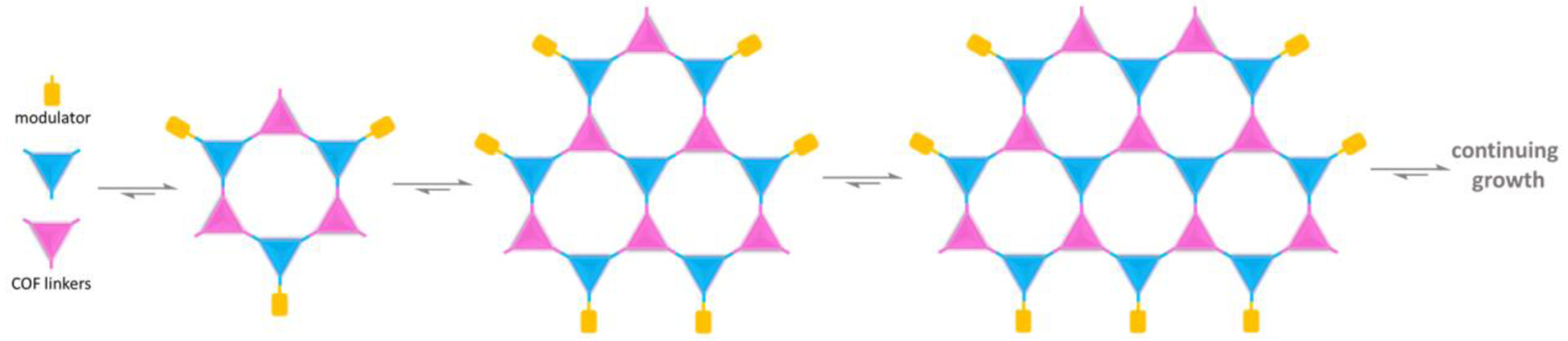

COFs are distinct among porous organic polymers due to their highly ordered crystalline structures. The dynamic nature of reversible reactions enables self-correction of defects in the polymerization process of COF synthesis thus crystallization becomes feasible. For example, the careful control of water formation during condensation reactions, e.g. imine condensation, boronic acid self-condensation, boronate ester formation, via solvent polarity and headspace of the sealed reaction tube modulates the reversibility of the reaction and ultimately crystallizes the COF.12 Nevertheless, the crystallization issue is still the biggest hurdle in COF chemistry and can only be overcome through a time-consuming extensive empirical screening of synthetic parameters. Even then, COFs are usually isolated as microcrystalline powders composed of aggregated nanometer-scale crystallites. The concept of modulation has proved to be an effective method in metal-organic framework (MOF) synthesis to control the crystallinity, size, defects, and morphology of the MOFs. Modulation is carried out by introducing mono-functionalized terminating ligands to the synthetic mixture that will compete with the more symmetric bridging ligands for coordination to the metal centers of the MOF.60–64 The analogous strategy for regulating COF crystallization had not appeared until a better understanding of the growth mechanism of COF crystals was gained (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of modulated synthesis of COFs.

The first COF growth mechanism studies were performed on a 2D boronic ester COF (COF-5)65–68 and imine COFs69,70 by the Dichtel group. In a typical COF synthesis, fast precipitation of amorphous solid initially occurred; this amorphous solid transformed into microcrystalline powders overtime (usually on a time scale of days), implying uncontrolled nucleation and growth process.65,69–71 Combined experimental and theoretical studies on the kinetics of COF-5 formation disclosed that nucleation and growth were second-order and first-order dependent on the monomer concentrations, respectively. This means a threshold monomer concentration exists; below which, growth dominates over nucleation (Figure 4A),68 thus temporarily resolving the nucleation and the growth is feasible. Based on this, controlling the monomer concentration via slow addition to preformed nanoparticle seeds of boronate COFs, Dichtel and coworkers successfully synthesized micrometer-sized single-crystalline 2D boronate ester−linked COFs colloids (Figure 4B).72 Prior research into 2D boronate COF synthesis determined that a solvent mixture of 1,4-dioxane and mesitylene prevented aggregation and precipitation, but Dichtel and coworkers found that the addition of CH3CN as another co-solvent was necessary to acquire single crystals and claimed that CH3CN stabilized the COF seed crystals and the subsequently grown COFs. Though not related to the concept of modulation, limiting the monomer concentration to increase the COF crystallinity could also be realized by other methods such as in situ release of a protected monomer. This has been exclusively applied to 2D imine linked COF synthesis including the use of protected monomers such as, tert-butyloxycarbonyl group protected amine monomer,73 N-aryl benzophenone imines as a masked amine monomer,74 protonated amine salt monomer,75 imine protected aldehyde monomer,76 and acetal protected aldehyde monomer77,78.

Figure 4.

(A) Comparison of the dynamics of nucleation and growth in seeded growth of COF-5. Reprinted with permission from ref 68. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society; (B) Seeded growth approach towards 2D boronate COF single crystals. Reprinted with permission from ref 72. Copyright 2018 The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Dichtel and coworkers firstly employed monofunctional 4-tert-butylcatechol (TCAT) as a competitor in COF-5 synthesis.65 The results showed that the COF formation was slowed down and the average crystalline domain size was slightly increased from 23 nm to maximum 32 nm. The presence of water almost doubled the average domain diameter to 40 nm. TCAT had a more pronounced modulation effect when combined with the seeded growth method.79 Ultimately, using a large excess of TCAT (≥ 10 equiv. to 1,4-benzenediboronic acid) enabled the formation of crystals with an average size of 450 nm (Figure 5A). TCAT functioned as a nucleation inhibitor and induced the particles to grow anisotropically in the out-of-plane direction. Almost no TCAT was incorporated into the final COF product.

Figure 5.

TEM characterization of COF-5 particles modulated by (A) TCAT with varied amounts of monomers. Reprinted with permission from ref 79. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society; and (B) by different content of MPBA. Reprinted with permission from ref 80 (https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.5b10708). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society, respectively. Note: further permissions related to the material excerpted should be directed to the ACS. (C) Post-modification of COF-5.

On the other hand, Bein and coworkers demonstrated monoboronic acids to be more effective modulators in conventional solvothermal synthesis for COF-5 to increase the domain sizes reaching several hundreds of nanometers (Figure 5B).80 The effect of the amount of modulator on the crystallinity and porosity exhibited a volcano type. An optimum of 10% 4-mercaptophenylboronic acid (MPBA) (substituted fraction of BDBA while keeping the total amount of boric acid groups constant) gave the best results with a surface area of 2100 m2 g−1 and a pore volume of 1.14 cm3 g−1, compared to 1200 m2 g−1 and 0.64 cm3 g−1 of the unmodulated COF. On the contrary to the TCAT modulator, the monoboronic acids modulators were incorporated in the COF structure at the grain boundaries. The modulator was believed to slow down the COF formation by repetitive attachment and detachment to the terminal ends of the 2D sheets, thus facilitating the healing of defects to form large crystalline domains. Taking advantage of the incorporation of the modulator, methoxypolyethylene glycol maleimide was successfully coated on the COF via a Michael-type addition (Figure 5C). This modification significantly increased the stability of COF-5 towards alcohol solvents. When 4-carboxyphenyl boronic acid (CPBA) as the modulating agent was used, an amino-functionalized dye ATTO 633 was covalently attached to the COF via amide condensation (Figure 5C).

Further slowing down the imine condensation reaction by using a large excess of aniline as modulator and reaction times as long as 80 days allowed Wang, Sun, Yaghi and their colleagues to grow micrometer-sized 3D imine COFs of high quality suitable for single crystal x-ray diffraction characterization with standard laboratory equipment for the first time (Figure 6).81 It should be noted that only limited single crystal COFs are known to date.72,77,82,83 For example, in the presence of 15 equiv. aniline, single crystals of COF-300 slowly crystallized out with a size of ~60 μm within 30 to 40 days and ~100 μm in 80 days at ambient temperature. Anisotropic refinement with resolutions of up to 0.83 Å could be achieved thanks to the exceptional crystal quality. Thus the degree of interpenetration, structural distortions, the interactions of guest molecules with the host framework and subtle conformational differences can be unambiguously determined which is impossible by means of other indirect structure determination techniques.84,85 The reactivity of the modulator, hence the reversibility of the formed imine bond, is critical for the successful growing of COF single crystals. The authors screened a series of monodentate amines and aldehydes, only aniline was able to modulate the crystallization.

Figure 6.

SEM and optical microscopy images of single-crystalline COFs modulated by aniline. Reprinted with permission from ref 81. Copyright 2018 The American Association for the Advancement of Science

Jiang and co-workers proved that the modulation strategy is also applicable to the synthesis of imine based 2D COF nanosheet (NS).86 In the presence of large excess amounts of 2,4,6-trimethylbenzaldehyde (TBA), a set of micrometers sized ultrathin (< 2.1 nm) imine-based 2D COF NSs were isolated in large scale (> 100 mg) and high yield (> 55%) under solvothermal conditions (Figure 7). The high crystallinity and ultrathin nature of the 2D COF NSs can even be directly observed by scanning tunneling microscope (STM). The growth mechanism study revealed that TBA bonded at the edge of both the oligomers and the COF NSs and the dynamically reversible nature of the lateral imine bond was critical to the lateral growth via imine exchange. Other benzaldehydes with larger substituted groups at the o-positions of the aldehyde group such as 3,5-di-tert-butylbenzaldehyde, 2,6-dimethoxybenzaldehyde, and 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)-benzaldehyde disfavored the nucleophilic attack to the imine bond by amine monomers thus only led to the formation of some soluble oligomers. Bonded TBA took an almost perpendicular conformation to the surface during the reaction, therefore limiting the axial π−π stacking to nanosheets. The COF-367-Co NSs exhibited excellent photocatalytic activity towards CO2-to-CO conversion with a rate of 10162 μmol g−1 h−1 and selectivity of ca. 78% in the presence of Ru(bpy)32+ as photosensitizer. The results were far superior to that of the bulk COF-367-Co (rate: 124 μmol g−1 h−1, selectivity: ca. 13%) under the same experimental conditions.

Figure 7.

TEM (a, c, e, g) and AFM (b, d, f, h) images of COF-367-Co NSs (a, b), COF-366 NSs (c, d), TAPB-BPDA COF NSs (e, f), and TAPB-BDA COF NSs (g, h) modulated by TBA. Reprinted with permission from ref 86. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

Wang, Liu, and coworkers uncovered that when both mono-functional benzaldehyde and aniline modulators were applied simultaneously, controlled morphology of 2D imine COFs could be achieved.87 Depending on the monomer concentrations and the solvent compositions, highly ordered spherical, short-tubular, hollow-fibroid COFs consisting of nano-flakes and irregular COF particles were selectively produced in Sc(OTf)3 catalyzed condensation of 1,3,5-triformybenzene (TFB) and 1,3,5-Tris(4-aminophenyl)benzene (TAPB) (Figure 8A) in the presence of 12 equiv. benzaldehyde and 12 equiv. aniline. On the contrary, without any modulator irregular aggregates consisting of small nanoparticles were obtained. If only benzaldehyde or only aniline was applied, naked spheres without nanoflakes (Figure 8B) or bare short rods (Figure 8C) were produced, respectively. The morphology control seems unique to Sc(OTf)3; using acetic acid as the catalyst the researchers were not able to control the morphology. The BET surface area value of 882 m2g−1 is much higher than 432 m2g−1 of the control sample synthesized without adding competitors. However, the crystallite size was only slightly increased to 17.6 nm from 10.7 nm of the control sample. Time-course PXRD study revealed that COF crystal generated at the initial stages of the reaction and continued as the reaction progresses, in contrast to the amorphous-to-crystalline phase transition in unmodulated imine COF synthesis65,69–71. This approach also allowed the production of thin films on different substrates up to centimeter size. Post-synthetic modulation treatment was shown to be effective in morphology control as well. A flow microreactor made from the COF films deposited with palladium nanoparticles had much improved performance than that made from the control COF in the reduction of p-nitrophenol and hydrogen-generation from methanolysis of ammonia. However, whether the incorporation of the competitors into the COFs occurred was not elucidated.

Figure 8.

(A) Phase diagram of COF morphologies dependent on monomer concentration and solvent compositions and the corresponding SEM images (catalyst and modulators concentration are the same). SEM images of COFs synthesized with 12 equiv. benzaldehyde only (B), with 12 equiv. aniline only (C). Reprinted with permission from ref 87. Copyright 2019 Elsevier Ltd.

2. Mixed linker/linkage approach

To date, the majority of COFs are made either from self-condensation or two-component condensation reactions. Therefore, developing COFs with new topologies and higher complexity relies on novel monomer synthesis which is inherently limited by the need for complex organic synthesis. Employing multiple monomers in one pot provides an opportunity to access frameworks with new structures and functions, a strategy that has been widely used in MOF chemistry.88–92 Depending on the structure of the resulting framework, we could categorize mixed linker approach into two groups: isostructural mixed linker (IML) approach where the mixed linkers give the same structure as the single type of linker does and heterostructural mixed linker (HML) strategy where the delivered network adopts a different structure than that from a single type of linker (Figure 9). The IML approach is used to install linkers with different compositions but analogous topologies so that multiple COFs with the same topology but different functions can be synthesized. Whereas HML strategy might synthesize a COF with a new topology.

Figure 9.

Topology diagrams for the IML (left) and HML (right) approaches using self-condensation of a trifunctional linker (in black) as an example. A regular hexagon for IML (condensation with a symmetry-identical linker in red) and a stretched hexagon for HML (condensation with a desymmetric linker in green) are generated, respectively.

2.1. isostructural mixed linker (IML) approach

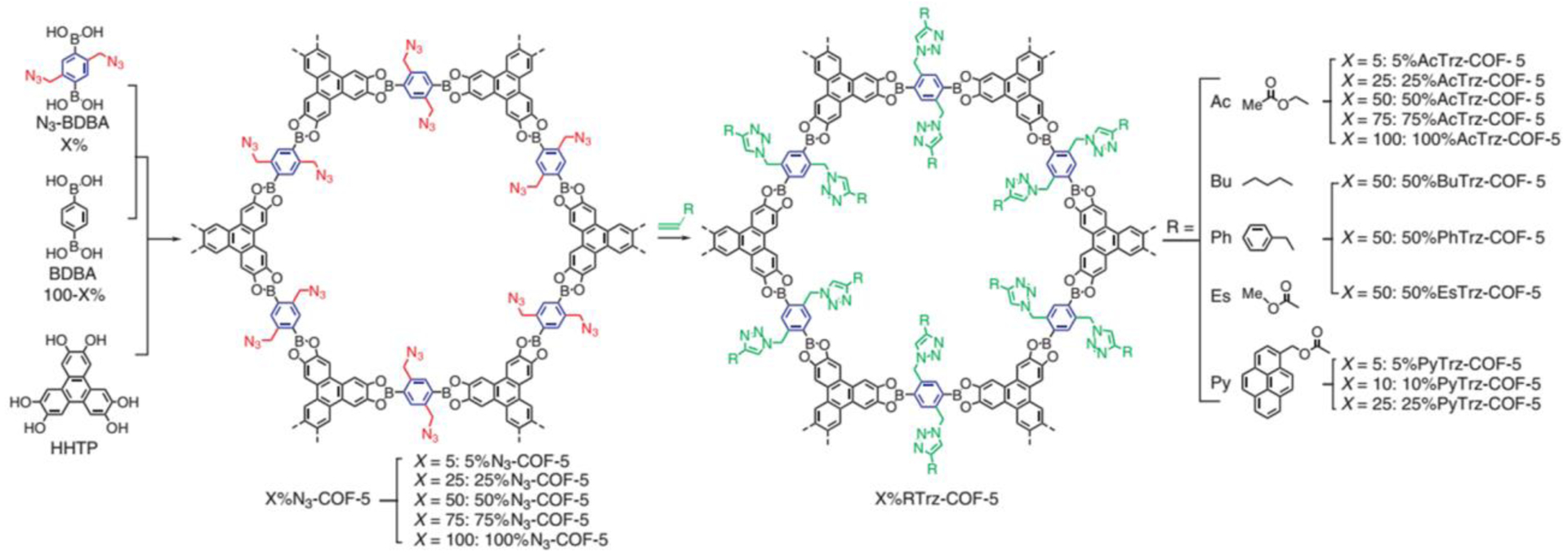

In the IML approach, distinct COFs with similar topologies are synthesized by using multiple monomers which are similar in connection geometry but have different secondary functionalities (e.g. side groups) between them. So far 2D COFs have been the main subject of this approach, resulting in the rapid synthesis of multiple COFs with analogous topology but each with customized pore environments. Jiang and coworkers have demonstrated IML to be a general strategy for incorporating various organic functionalities onto the channel walls of 2D COFs.93–101 For example, condensation of 2,3,6,7,10,11-Hexahydroxytriphenylene (HHTP), 1,4-benzenediboronic acid (BDBA) and azide-appended BDBA (N3-BDBA) resulted in a series of COFs with a tunable amount of azide groups anchored on the hexagonal skeleton identical to that of COF-5 (Figure 10).93 A gradual decrease of the BET surface areas, pore volumes and pore sizes was observed as the azide content increases. More importantly, post-synthetical click reaction with alkynes produced alkyl chain, acetyl, aromatic unit, ester, and chromophoric unit decorated COF walls. For example, the functionalized 100%AcTrz-COF-5 was 16-fold more selective to CO2 over N2 when compared to COF-5. This strategy is operationally simple and universal regardless of the shape of the pore93,102 and the linkage type94–99. The tailor-made COF pore environment provides the foundation for the engineering of COFs to realize a variety of applications such as chiral catalysis,97,101,103 energy storage,98,100 and gas adsorption96,99.

Figure 10.

COFs bearing varied amounts of azide units on the walls synthesized by the condensation reaction of HHTP, BDBA and N3-BDBA and followed second step modification via click reaction. Reproduced with permission from ref 93. Copyright 2011 Springer Nature.

Furthermore, a linker with a reduced number of functional groups, which is so called truncated monomer, could also be employed in IML approach. Depending on the kinetics of the framework crystallization, the truncated linker will either be distributed as a minor component throughout a defective lattice of the whole network or act as a capping agent that bonds at the boundary of the crystallite. The later situation is strongly related to the concept of modulation. Not to be confused with the modulator which undergoes extensive exchange reactions with the monomers, oligomers, and COF crystallites in the system, truncated monomer in the IML approach has limited reversibility and does not promote the COF crystal growth.

Dichtel and co-workers found that both tri- and mono-functional boronic acids can be doped into 3D boroxine-linked COF-102, without changing the parent network structure constructed from the tetrahedral monomer (Figure 11).104–106 The truncated monomer was able to replace the tetrahedral building blocks up to ca. 30%. While higher loading ratio of truncated monomer leads to lower surface area and smaller pore volume, all the COF materials retained high surface areas above 2000 m2 g−1 and large pore volumes exceeding 1.1 cm3 g−1 that were capable of hosting guest molecules such as pyridinium iodide.104 Moreover, the allyl groups on the truncated motif in COF-102-allyl readily underwent thiol–ene coupling reaction with propanethiol quantitatively, affording a thiol-modified COF.105 The crystallinity and microporosity of the resulting COF-102-SPr were well preserved and the COF had a high BET surface area of 1424 m2 g−1.

Figure 11.

Co-condensation of tetra(4-dihydroxyborylphenyl)methane with truncated monomers produces internally functionalized COF-102. Reproduced from ref 105. with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry and from ref 106. Copyright 2013 Elsevier Ltd.

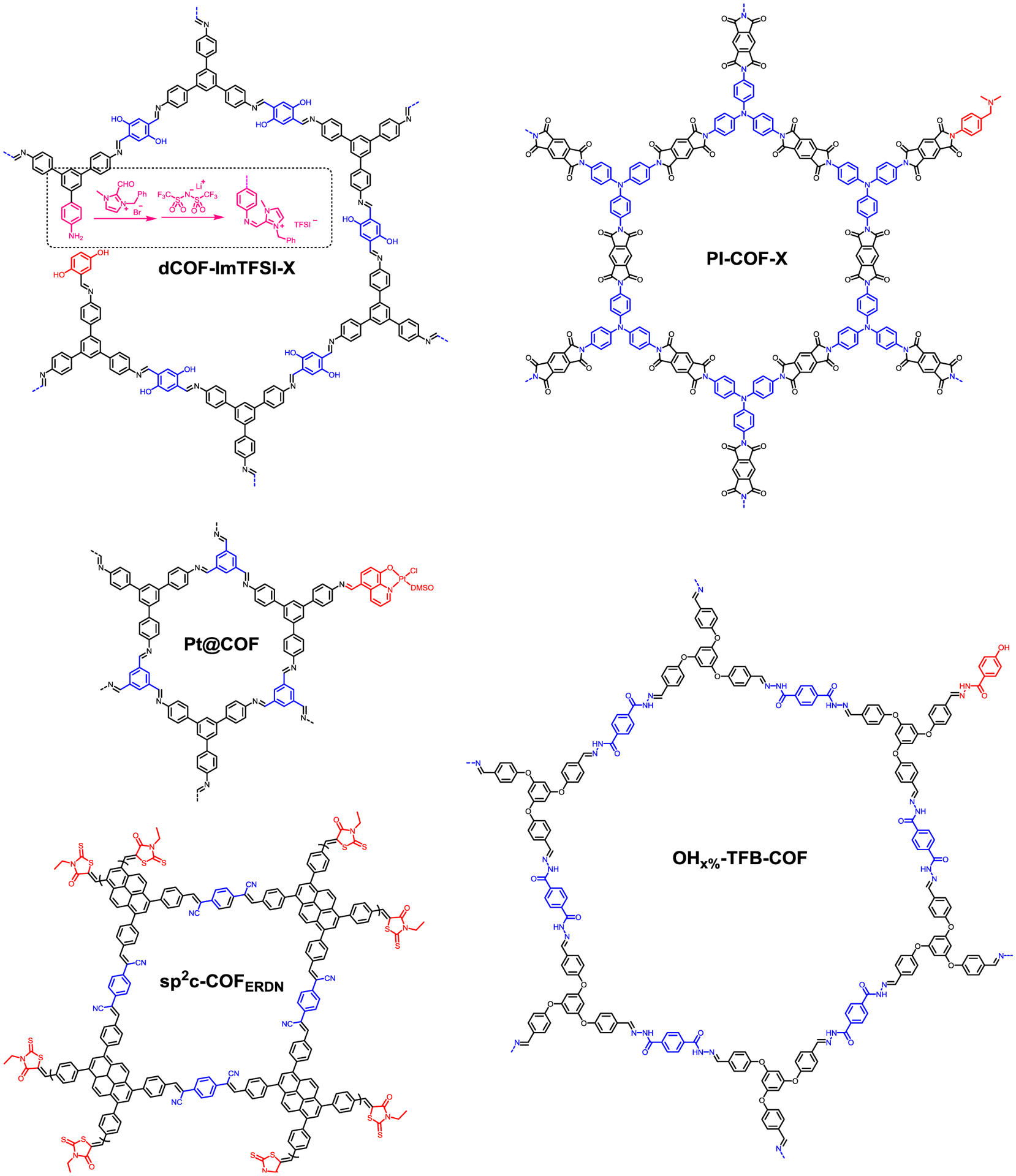

Han et al. partially substituted the 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalaldehyde linker with monotopic 2,5-dihydroxybenzaldehyde in a 2D imine COF with free amine site for post-synthetic modification (Figure 12).107 The Schiff-base reaction on the free amine sites afterwards introduced imidazolium functional groups onto the pore walls of COFs. The functionalized material dCOF-ImTFSI-X was employed as all-solid-state electrolytes for lithium-ion conduction and the ion conductivity reached as high as 7.05 × 10−3 S cm−1 at 423 K. Lee, Park, and coworkers reported an imide-linked COF, PI-COF-X, that incorporates 4-[(dimethylamino)methyl]aniline (DMMA) via a microwave-assisted reaction (Figure 12).108 The dimethyl amine functional groups of DMMA act as interaction sites with SO2 and the SO2 sorption capacity was recorded up to 40 wt%. Moreover, sorption was completely reversible for SO2 and the COF was highly stable on repeated sorption–desorption cycles. Cabrera, Alemán, and coworkers encapsulated a Pt (II) hydroxyquinoline fragment in a 2D imine COF.109 The synthesized Pt@COF displayed excellent photocatalytic efficiency in sulfide oxidation (TON up to 25000) and hydrodebromination (TON up to 7313) reactions. Jiang and coworkers integrated an electron-deficient 3-ethylrhodanine (ERDN) unit as an end-capping group to the periphery of a 2D sp2 conjugated COF, sp2c-COFERDN (Figure 12).110 The absorbance and band-gap structures had nearly 60% improvement of photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance than the unmodified COF under identical conditions. Jia et al. reported that 4-hydroxybenzhydrazide modulator enhanced the crystallinity of a hydrazone linked COF and its extraction efficiency for phthalate esters as solid-phase microextraction coatings.111

Figure 12.

Structures of mono-functional truncated monomer modified 2D COFs (truncated monomer and the corresponding multi-topic monomer are in red and blue respectively).

2.2. Heterostructural mixed linker (HML) approach

Concurrently, the research groups of Jiang and Zhao introduced the heterostructural mixed linker strategy into 2D boronic ester COF112 and imine COF113 respectively via multiple-component condensation in 2016. This could largely expand the structural diversity of COFs from a combinatorial analysis and allows access to novel topologies and structural complexity for COFs from relatively simple building blocks. As such, a total number of 44 three-component hexagonal COFs with HHTP knot, six four-component hexagonal COFs with HHTP knot, and one three-component tetragonal COFs with phthalocyanine NiPc knot were successfully prepared by Jiang and co-authors. (Figure 13).112 Out of the many dynamic combinatorial possibilities such as mixtures of self-sorted COFs with only one type of linker incorporation, only the pure phase of mixed linker COFs were isolated. The synthesized COFs showed high crystallinity and porosity with BET surface area ranging between 512–2054 m2g−1 and pore size between 2.7–4.8 nm. By varying the relative ratio, the charge-transferring capability of electron-donor type COFs constructed from the co-condensation of electron-donating NiPc with electron-accepting linkers and electron-donating linkers was nearly enhanced 180,000%.

Figure 13.

(A) Heterostructural multicomponent [1+2] or [1+3] condensation strategy for the synthesis of hexagonal and tetragonal COFs. Reproduced with permission from ref 112. Copyright 2016 Springer Nature. (B) the knots and linkers used in the study.

By mixing a D2h symmetric tetraamine with a 1:1 ratio of two distinct C2-symmetric dialdehydes of different lengths, Zhao and coworkers were able to make a 2D imine linked COFs with three different pore sizes in the same COF. (Figure 14).113 The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of the two new COFs (SIOC-COF-1 and SIOC-COF-2) confirmed the presence of three different-sized pores in both COFs. SIOC-COF-1 had a BET surface area of 478.41 m2g−1 while SIOC-COF-2 had a lower value of 46.13 m2g−1. The heterostructural mixed linker strategy could be a complementary approach towards 2D hierarchical COF structures to the desymmetric knot approach.16,114–118

Figure 14.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis of triple-pore from a D2h and two linear C2 symmetrical monomers.

Lotsch and coworkers reported an unprecedented bex net topology from a three component imine condensation of linear, triangular and tetratopic linkers which are of different topicity (Figure 15).119 The structures of PT2B-COF and PY2B-COF can be deconstructed as benzidine cross-linked 1D ribbon formed from tetrakis(p-aminophenyl)pyrene (TAPPy) and 4,4’,4”-(1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triyl)tribenzaldehyde/5,5’,5”-(benzene-1,3,5-triyl)tripicolinaldehyde. PT2B-COF and PY2B-COF were synthesized with high enough crystallinity that TEM analysis was able to identify lattice spacings. The BET surface area for the PT2B and PY2B-COFs was 2367 m2g−1 and 1984 m2g−1 deduced from Argon sorption isotherms. The dual pore structure was also clearly seen from pore size distribution analysis at ~1.83 nm and 2.37 nm, respectively. Similar structured COF-77 made from tetrakis(p-formylphenyl)pyrene (TFPPy), tris(4-aminophenyl)amine (TAA) and benzene-1,4-dialdehyde (BDA) was later reported by Yaghi and coworkers.120

Figure 15.

PT2B-COF and PY2B -COF synthesized from three-component condensations with a bex network topology.

2.3. Mixed linkage approach

Zhao and coworkers showed that the orthogonal reactions between imine condensation and boronic acid trimerization/boronate ester formation could be applied to construct 2D COFs bearing two types of linkages.121 A binary COF (NTU-COF-1) was produced from 4-formylphenylboronic acid (FPBA) and 1,3,5-tris(4-aminophenyl)-benzene (TAPB) through the formations of imine and boroxine linkages simultaneously. Additionally, a ternary COF was built from FPBA, TAPB, and HHTP with simultaneous imine bond and C2O2B boronate ring formation (NTU-COF-2, Figure 16). Interestingly a stepwise approach involving IM-1 or IM-2 to synthesize the two COFs failed suggesting a parallel two types of linkages formation instead of a tandem process. The parallel mechanism was also supported by the constant ratio of the monomers during the reaction. The BET surface area was quite small for NTU-COF-1 (41 m2 g−1) but large for NTU-COF-2 (1619 m2 g−1). NTU-COF-2 displayed a high H2 uptake of 174 cm3 g−1 (1.55 wt %) at 1.0 bar and 77 K. The orthogonal crystallization strategy has since become a more general method and to date, a large library of 2D COFs have been obtained with tailored π-lattice, pore size and pore shape, holding great promise for various applications.122–124

Figure 16.

Syntheses of mixed linkage COFs (i) NTU-COF-1 and (ii) NTU-COF-2 involving the orthogonal imine condensation and boronic acid trimerization/boronate ester formation reactions. Reprinted with permission from ref 121 (https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ja510926w). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. Note: further permissions related to the material excerpted should be directed to the ACS.

Fang, Qiu, and coworkers demonstrated that the mixed linkage strategy can be implemented into 3D COFs as well.125 The condensation of tetrahedral linker, 1,3,5,7-tetraaminoadamantane (TAA), and 4-formylphenylboronic acid or 2-fluoro-4-formylphenylboronic acid (FFPBA) produces two 3D framework structures connected by imine and boroxine ring, DL-COF-1 and DLCOF-2, respectively (Figure 17). DL-COF-1 and DLCOF-2 showed high BET surface area of 2259 m2 g−1 and 2071 m2 g−1, respectively. The dual linkages provide both acidic (boroxine ring) and basic sites (imine group) in proximity in the 3D structure. Thus, a cascade reaction involving acidic sites catalyzed hydrolysis of the acetal followed by basic sites catalyzed Knoevenagel condensation was developed using DL-COF-1 and DLCOF-2 as bifunctional catalysts.

Figure 17.

Synthesis of imine/boroxine dual-linked 3D COFs.

By taking advantage of the difference in the chemical stability of boroxine and hydrazone linkages, Zhao et al. developed a novel method to fabricate organic nanotubes via selective disassembly of a 2D mixed linkage COF (COF-OEt, Figure 18).126 While hydrazone linkage is resistant against hydrolysis, boroxine is vulnerable towards moisture. Thus, upon suspending in an aqueous hydrochloric acid solution for several days at room temperature, COF-OEt readily disengaged to intertwined nanotubes with an average diameter of 5.5 ± 0.6 nm. This work opens a new application for COFs and may inspire new synthetic methods for macrocycle compounds.

Figure 18.

Schematic illustration for the fabrication of nanotubes through selectively hydrolyzing a 2D mixed linkage COF. Top-left shows the TEM images of COF before and after hydrolysis. Adapted with permission from ref 126. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Yaghi and coworkers reported that imine and imide linkages can be implemented into one network, both of which are more stable than B-O linkage. COF-78 was constructed from simple aldehyde, amine, and anhydride monomers directly, unlike the previous two cases that require a monomer having two different functionalities (Figure 19). The imine based 1D ribbon COF-76, produced from partial condensation of TFPPy and TAA, was found to be an intermediate to COF-78. Reticulating COF-76 and pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) can be finished either in a one-pot two-step manner or stepwise with isolated COF-76. However, when TFPPy, TAA, and PMDA were co-condensed at the same time, only the formation of COF-76 was observed. COF-78 synthesized from both methods had high BET surface areas (>1000 m2g−1). Pore size distribution confirmed the dual pore structure of COF-78 at 11 and 19 Å, respectively. It should be noted that COF-76 can also be linked to 2D COF-77 with all imine linkages via condensation with BDA.

Figure 19.

Synthesis of imine and imide co-linked COF-78.

3. Sub-stoichiometric Approach

In a conventional COF synthesis, a stoichiometric reaction between the complimentary linkers is performed and expected to provide a periodic network structure. Ideally, a fully bonded network is formed with a boundary of unreacted functionalities at the crystallite peripheral. Under this stereotype, choosing a potential COF building block is typically limited to simply selecting the geometry of the monomers to give the most regular frameworks. Accordingly, the vast majority of 2D COFs are represented by five simple topologies hcb, hxl, kgm, sql, and kgd with one or two kinds of vertices and one kind of edge and are therefore edge-transitive (Figure 20A).127–129 For this reason, the combination of triangular tritopic and rectangular tetratopic linkers was seldom considered for 2D COF construction because of the seeming mismatch of symmetry. However, when full condensation was not required as a guideline, for example, the reticulation of a triangular tritopic and rectangular tetratopic linkers would generate four new possible crystalline nets, i.e. tth-defect, bex, mtf, and 1D ribbon.130 The tth-defect, bex and 1D ribbon nets feature frustrated network bonding with unreacted functionalities on the backbone (Figure 20 B). Thanks to the dynamic nature of the reversible bonds and the sub-stoichiometric reaction conditions between the monomers the formation of these highly ordered frustrated nets is possible. Without reversibility induced error-correction, randomly cross-linked structures are most likely to be produced. For the tth-defect net, there are three kinds of vertices and two kinds of edges. All the tetratopic linkers behave as genuine tetratopic building blocks with all the functionalities being reacted, while one-third of the tritopic linkers behave as ditopic linkers with only two functionalities on each being used for network connection and the other two-thirds as normal tritopic linkers. For the bex net, there are three kinds of vertices and two kinds of edges as well. All the functionalities of the tritopic linkers are fully reacted while the tetratopic linkers sit in two different environments as bi- and tetratopic linkers simultaneously. For the 1D ribbons, there are two kinds of vertices and one kind of edges. The tritopic linker behaves as a ditopic linker and leaves one of its functionalities unreacted on the backbone, whereas all the functionalities of the tetratopic linker are reacted.

Figure 20.

(A) The most common five topologies for 2D COFs. (B) Possible topologies via reticulation of a triangular tritopic and a rectangular tetratopic linker. Reprinted with permission from ref 129 and ref 130. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Loh and coworkers firstly observed the frustrated bonding phenomenon in the imine condensation of two tetratopic tetraphenylethylene (TPE)-based complementary linkers.131 When two topologically identical but complementary tetratopic tetraphenylethylene (TPE)-based building blocks, ETTA and 4,4’,4”,4”’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl) tetrabenzaldehyde (ETTB) were reacted in o-dichlorobenzene/n-butanol/acetic acid mixture, the fully condensed imine COF, TPE-COF-I was formed, by following a [4+4] condensation pathway (Figure 21). However, when the same building blocks were reacted in 1,4-dioxane/ acetic acid mixture, the sub-stoichiometrically condensed frustrated imine network, TPE-COF-II, was formed by following a [2+4] condensation pathway. The unusual frustrated bonding structure was found not to be affected by the feeding ratio of the two linkers (ETTA/ETTB = 1/1 or 1/2), thus implying the different thermodynamics arising from the solvent mixtures. Both the COFs are highly crystalline with BET surface areas of 1535 m2 g−1for TPE-COF-I and 2168 m2 g−1 for TPECOF-II. Interestingly, TPE-COF-II showed enhanced CO2 adsorption performance of 118.8 cm3 g−1 (1 atm, 273 K) and 60.5 cm3 g−1 (1 atm, 298 K) than its fully condensed counterpart TPE-COF-I of 68.6 cm3 g−1 (1 atm, 273 K) and 37.8 cm3 g−1 (1 atm, 298 K).

Figure 21.

Synthesis of fully condensed TPE-COF-I and partially condensed TPE-COF-II.

Moving forward from reaction conditions control to rational topology design, Banerjee, Lotsch, and coworkers investigated the reticulation of tritopic and tetratopic linkers.119 They found that the reaction of a triangular tritopic linker, 4,4’,4”-(1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triyl)tribenzaldehyde (for PT-COF) or 5,5’,5”-(benzene-1,3,5-triyl)tripicolinaldehyde (for PY-COF) with TAPPy, resulted into the formation of sub-stoichiometric dual pore 2D COFs of bex topology (Figure 22). TAPPy was found to be behaving concurrently as a bi- and a tetradentate linker in two distinct network environments. Both the PT-COF and PY-COF were employed as heterogeneous organocatalysts to obtain substituted chromenes via cyclization–substitution cascade reaction of 2-hydroxylcinnamaldehyde with trimethylsilyl enol ether. Moreover, post-synthetic functional group transformation of free amine groups to isothiocyanates by reacting with CS2 in presence of cyanuric chloride was also reported.

Figure 22.

Synthesis PT-COF and PY-COF with partially condensed frustrated networks.

In line with acquiring diverse and complex structural topologies in COFs, Yaghi and coworkers reported a 2D imine-linked COF with the tth-defect topology from the combination of a tritopic and a tetratopic linker.129 The reaction of 1,3,5-tris(p-formylphenyl)benzene (TFPB) with ETTA in o-dichlorobenzene/n-butanol/aqueous acetic acid mixture resulted in the formation of COF-340. (Figure 23).129 The presence of free formyl groups on the backbone was confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy. 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the digested sample confirmed the 3:2 ratio of TFPB and ETTA, expected stoichiometry for the tth-defect topology.

Figure 23.

Synthesis of partially condensed COF-340 under solvothermal conditions.

Xi, Xie, and coworkers reported the synthesis of three sub-stoichiometric 2D COFs and their applications in photocatalysis (Figure 24).132 TTCOF-1 and TTCOF-2 opted bex topology, having free amine functional groups on their backbones whereas TTCOF-3 adopted a tth-defect topology with free formyl functional groups on its backbone. TTCOF-2 exhibited good performance in promoting aerobic cross-dehydrogenative coupling reactions between 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives and nitromethane, acetone, and TMSCN as well as in catalyzing arylboronic acid oxidation under blue light irradiation.132 Moreover, TTCOF-2 was recently used to fabricate a COF-graphene heterostructure as ultrasensitive photodetector. A photoresponsivity of ≈3.2 × 107 A W−1 at 473 nm and time response of ≈1.14 ms was achieved on the photodetector.133

Figure 24.

Construction of TTCOF-1, TTCOF-2, and TTCOF-3 with partially condensed frustrated networks.

Finally, Yaghi and coworkers reported a 1D ribbon structure by reticulating tri- and tetra-topic monomers. Interestingly, 1D ribbons could be further reticulated into 2D COFs by reacting with a linear complementary linker (Figure 25).120 Teteratopic TFPPy, and tritopic TAA were reacted in a 1:2 stoichiometric ratio to form COF-76 with unreacted free -NH2 functionalities on the backbone of the 1D ribbon. This 1D ribbon COF showed a BET surface area of 860 m2 g−1with type I isotherm. Thereafter, COF-76 was reticulated to 2D COFs, COF-77 and COF-78, by reacting with benzene-1,4-dialdehyde (BDA) and PMDA respectively (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

Formation of 1D ribbon COF-76 and its subsequent conversion to 2D COFs. Reprinted with permission from ref 120. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Sun, Loh, and coworkers reported a single crystal 1D metallo-COF, mCOF-Ag with free amine functionalities on the backbone.77 The COF was obtained under solvothermal conditions by reacting 4,4’-(1,10-phenanthroline-2,9-diyl)dianiline (PDA) and 2,9-bis(4-(dimethoxymethyl)phenyl)-1,10-phenanthroline (PDB-OMe) in 1:3 ratio in the presence of silver salt. Without silver as a template, only an amorphous polymer was obtained (Figure 26). The crystal structure analysis revealed that the 1D zigzag chains were packed to corrugated 2D layers by the π–π stacking of interlayer phenanthroline rings and the hydrogen bonding of free amines with tetrafluoroborate anions. Later, mCOF-Ag was converted to a cross-linked woven network, wCOF-Ag, by reacting the free amino functionality of mCOF-Ag with glyoxal. The similar copper analogue mCOF-Cu was reported by the same group very recently starting from the preassembled copper complex Cu(PDA)2(BF4) (Figure 26).134 However, the reaction of Cu(PDA)2(BF4) and PDB-OMe firstly went through a dynamic ligand exchange on copper to give the heteroleptic complex which was then linked by PDA to give mCOF-Cu. As the presence of two metals holds great potential for catalysis, the free NH2 groups were tested to stabilize Pt2+ions. Interestingly an immobilization of 0.47% Pt content was achieved, close to the theoretical value of 0.50%.

Figure 26.

Synthesis of mCOF-Ag, wCOF-Ag, and mCOF-Cu. Reprinted with permission from ref 77. Copyright 2011 Springer Nature and ref 134. Copyright 2020 Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

4. Framework Isomerism

Isomerism is a very common phenomenon in organic chemistry where compounds have the same molecular formula but different chemical structures thus displaying distinct physical and chemical properties. “Framework isomers” has been defined in MOF chemistry by Zhou et al. as “MOFs constructed from the same ligand and metal species that display different network structures”.135 Similarly, we can define “COF isomers” as “COFs constructed from the same monomers that display different network structures” accordingly. Following this definition, TPE-COF-I and TPE-COF-II in Section 3 are a pair of framework isomers. Although not being well studied and understood for COFs because of the limited examples, framework isomerization has started to draw the attention of researchers. The pore structure of COFs can be designed by using linkers with desirable symmetry. For example, reticulation of a C3 and a C2 symmetric linker would generate a uniform hexagonal pore. However, it is not always unambiguous, and one such example is the reticulation of a D2h symmetric building block and a C2 symmetric monomer. Theoretically, a uniform rhombus, a parallelogram network, and a Kagome lattice, are all possible topologies. Besides, tiling a D2h symmetric and a C3 symmetric monomer also has the potential to generate a bex, a tth-defect, a mtf or a 1D ribbon framework (See Section 3).

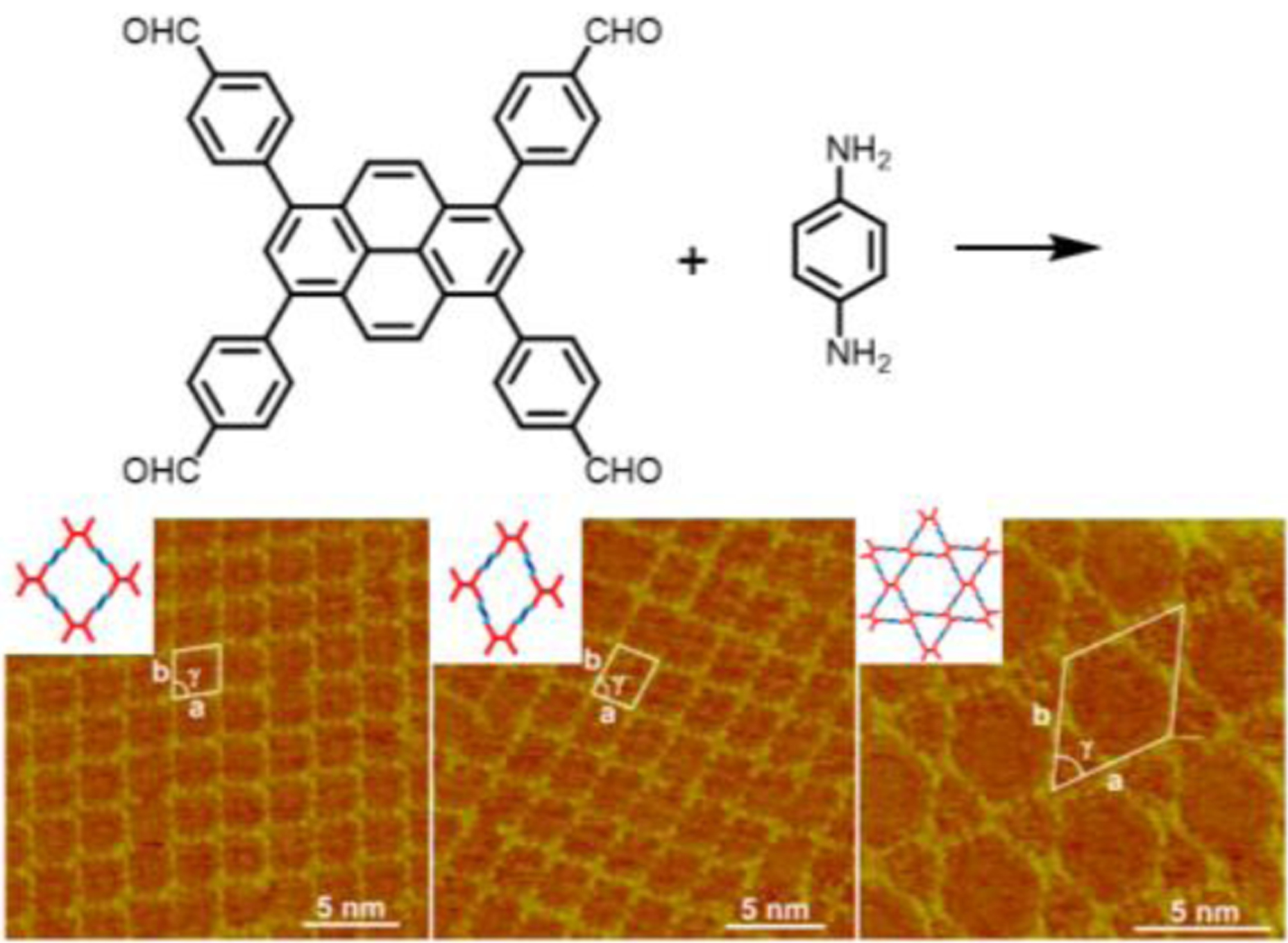

Wang and coworkers observed the formation of three different morphologies via surface condensation of TFPPy and linear diamines on highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) by STM (Figure 27).136 The well-defined phase separation observed in the single-layered COFs in the STM images implied a self-sorting growth process where the attached monomers on the three different nuclei adjust themselves to form the corresponding morphological COFs exclusively. Moreover, the distribution of the three species can be tuned by changing the monomer concentrations where the two quadrate networks are preferred at high concentrations.

Figure 27.

High-resolution STM images of the rhombus, parallelogram, and Kagome morphological networks formed from surface condensation of TFPPy and 1,4-phenylenediamine. Reprinted with permission from ref 136. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

By controlling the solvothermal reaction solvents, Zhao and coworkers successfully acquired both the rhombus and Kagome topologies in bulk microcrystalline COFs from 4’,4”’,4””’,4”””’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carbaldehyde]) (ETTBC) and 2,5-diaminotoluene (DAT).137 The rhombus network SP-COF-ED was generated from mesitylene/1,4-dioxane solvent mixtures, while the Kagome form DP-COF-ED was obtained in nBuOH/o-DCB and can be transformed to SP-COF-ED when subjected to the synthesis conditions as used for SP-COF-ED (Figure 28). The BET surface area was found to be 360 m2g−1 for SP-COF-ED and 559 m2g−1 for DP-COF-ED, respectively. Pore size distribution analysis clearly revealed the single pore nature of SP-COF-ED with a pore size of 21.9 Å and the dual-pore of DP-COF-ED with two pore sizes of 12.0 and 42.2 Å corresponding to the triangular and hexagonal pores respectively. Interestingly, the two COF isomers displayed distinct solvent stabilities. A stability order of THF > CHCl3 > 1,4-dioxane > DMF > H2O was observed for SP-COF-ED while the order was CHCl3 > THF >DMF > 1,4-dioxane > H2O for DP-COF-ED. In addition, n-hexane vapor led to a complete loss of the crystallinity of SP-COF-ED, but a reversible structural deformation of DP-COF-ED as evidenced by the shifts of PXRD patterns.

Figure 28.

Controlling the topology of COFs constructed from D2h and C2 symmetrical linkers via solvothermal solvent or non-covalent interactions.

Though not to be considered as constitution isomers, isoreticular synthesis of COFs was shown to have substituent dependent topologies under the same solvothermal conditions. Zhao and co-workers reported that the condensation of ETTA and ortho-substituted terephthalaldehyde gave a single-pore COF with larger alkyl chain groups, likely to reduce the steric repulsion between the substituents and formed dual-pore COF with small H groups respectively (Figure 28).138,139 Kuo and coworkers discovered that stitching a bicarbazole tetraformyl building block with either benzidine (BD) or 1,4-dihydroxybenzidine (DHBD) linker resulted in two distinct topologies; a uniform tetragonal pore structure for BD and a Kagome structure for the DHBD linker (Figure 28).140 The authors ascribed this selectivity to the hydrogen bonding stabilizing effect for the Kagome structure. Therefore manipulation of non-covalent interactions opens up a new route to regulate the topologies, properties, and functions of COFs.141–143

Perepichka, Rosei, Clair, and coworkers observed polymorphism during the on-surface trimerization of low-symmetry 1,3-benzenediboronic acid.144 Two distinct polymorphs; a honeycomb network and Sierpiński triangles (ST), are formed (Figure 29). Monomer concentration is a factor to influence the polymorphism in that high-concentration conditions favor 2D honeycomb-like networks while low-concentration conditions favor ST polymorphs.

Figure 29.

Formation of homotactic 2D COF or Sierpiński triangle (ST) from on surface self-condensation of D1 symmetrical 1,3-benzenediboronic acid. (a) STM image of extended honeycomb-like 2D COFs; (b) Schematic representation of the honeycomb network; (c) STM image of a ST-3 pattern; (d) Schematic representation of ST-3. Reprinted from ref. 144 with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

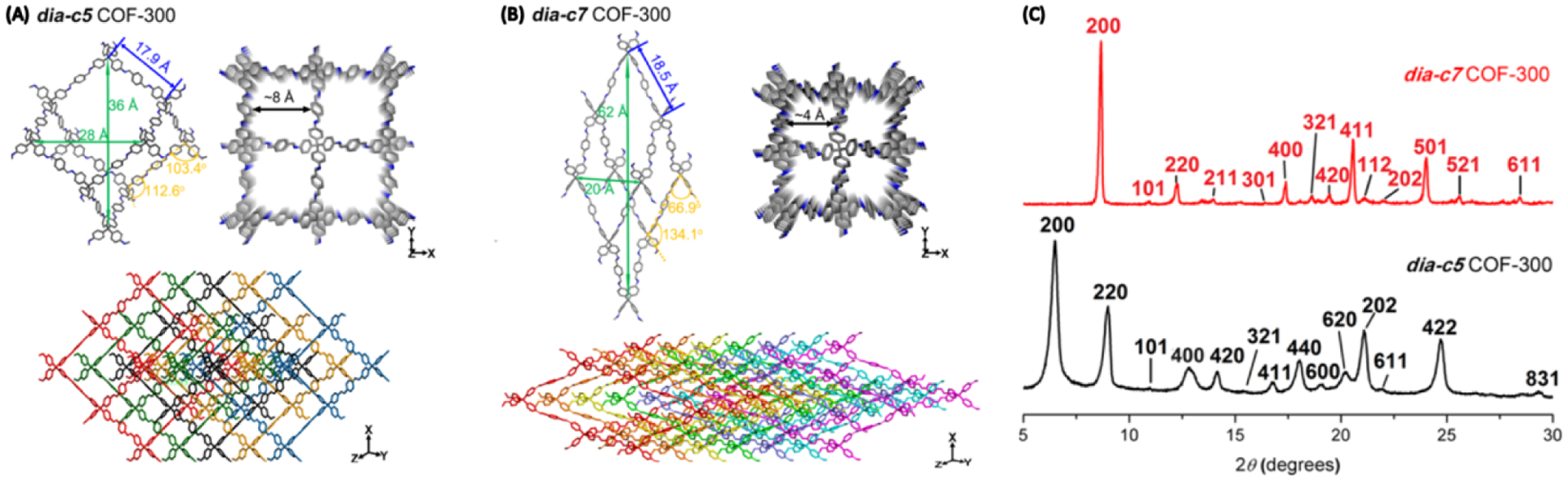

3D COFs usually are crystallized with different degrees of interpenetration but interpenetration is difficult to control.142 Wang and coworkers reported a rare example of interpenetration isomerism in 3D COFs.145 COF-300 was first reported in 2009 by Yaghi et al. as a 5-fold interpenetrated diamond structure (dia-c5 topology).49 By holding the reaction mixture at room temperature for 72 h and then 50 °C for 72 h, prior to the original procedure (120 °C for 72 h), a 7-fold interpenetrated diamond structure was formed (dia-c7 COF-300) (Figure 30). The proposed structure was supported by PXRD analysis and rotation electron diffraction (RED) measurements. The increased degree of interpenetration narrows the pore size from ~8 to ~4 Å.

Figure 30.

Crystal structures of COF-300 with (A) 5- and (B) 7-fold interpenetration and (C) the comparison of the PXRD patterns. Adapted with permission from ref 145. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

In addition to the reaction conditions-controlled synthesis, COF isomers can be also generated by external stimulus post-synthetically, as a result of the structure dynamics. Zhang and coworkers observed guest molecule induced framework expansion/contraction of 3D imine COFs.84,146,147 For example, COF-300 adopts a contracted structure upon exposure to moisture via hydrogen bonding interactions (Figure 31). The unit cell volume of COF-300-H2O was reduced by ~6% compared to the activated form COF-300-V. On the other hand, the inclusion of organic solvents led to a large crystal expansion. The COF-300-THF with tetrahydrofuran (THF) inclusion resulted in ~50% increment of the cell volume compared to COF-300-V. Such dynamic behaviors of COF-300 were attributed to the flexibility of the node geometry and the configuration of the organic linkers, and displacement between frameworks (Figure 31). A similar phenomenon was also observed on another 3D COF, LZU-301.146

Figure 31.

Guest-dependent structure dynamics of COF-300. Adapted with permission from ref 147. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

In the case of 2D COFs, guest molecules are able to switch on/off the interlayer correlations. Such an example was first reported by Bein, Medina, and coworkers on TAPB based COFs.148 TAPB-COFs constructed from unsubstituted linear monomers instantly lose crystallinity and porosity upon exposure to solvents or solvents vapors (1,4-dixoane, toluene, acetone, etc.) due to the weak interlayer π−π interactions. The crystallinity and long-range order can be completely restored by applying supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO2) activation (Figure 32). The interlayer on/off correlation switching cycle can be repeated many times. A higher CO2 to N2 uptake ratio for adsorption was observed on a 1,4-dioxane-treated COF in comparison to the crystalline counterpart. A reversible interlayer sliding in an imine-linked tetrathiafulvalene (TTF)-based COF induced by solvent treatment was reported by Zhang, Liu, and coworkers recently.149

Figure 32.

Schematic model showing the effect of solvent molecules on the layer stacking of TAPB-COFs. Adapted with permission from ref 148. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

5. Linker Exchange Approach

The dynamic covalent chemistry of reversible covalent bonds not only allows the aforementioned four strategies to tailor COFs during the crystallization process but also provides the chance to post synthetically modify the structure and functions via linker exchange. For MOFs, solvent assisted linker exchange, known as SALE, has been shown to be an important synthetic strategy to access novel MOFs that are not attainable via de novo synthesis. This heterogeneous chemical reaction process involves linker replacement via breaking and remaking the dynamic coordinate bonds within the parent MOF. Crystallization issues in direct synthesis associated with the incoming linkers because of the low solubility, poor chemical/thermal stability, functionality incompatibility, and undesirable topology can be circumvented by taking advantage of the crystalline structure of the parent MOF.150,151 Implementation of a similar idea in COF chemistry is expected to greatly expand the library of desirable function–property combined COFs (Figure 33). Despite the fundamental role of DCC in COF synthesis; it was not until recently that DCC was used to exchange linkers within COF. The scarcity of research featuring post-synthetic linker exchange within COFs when compared to the number of such examples in MOFs might be due to the fact that the covalent interactions in the former are more inert than the coordinate interactions in MOFs which makes the linker exchange in COFs more difficult.

Figure 33.

General representation of linker exchange.

The first successful example of COF to COF transformation via DCC-induced linker exchange was reported by Zhao and coworkers in 2017.115 They found that TP-COF-BZ can be converted to TP-COF-DAB in the presence of 10 equivalents of diaminobenzene in dimethylacetamide/mesitylene/3M AcOH mixture (1/21/2.2, v/v) at 120 °C for 72 h (Figure 34). The incorporation of 1,4-diaminobenzene in the modified COF was found to be 97.23% determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the digested sample. Both the high concentration and the electron-rich property of phenylenediamine were assumed to be the key factors in driving the conversion of TP-COF-BZ to TP-COF-DAB nearly quantitative yields.

Figure 34.

Transformation of TP-COF-BZ to TP-COF-DAB. Reprinted with permission from ref 115. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

Yan and coworkers reported the construction of an amino-functionalized imine-linked covalent organic frameworks via linker exchange.152 The transformation of mother COF PTPA to daughter COF PTBD-NH2 required 10 equivalents of 3,3ʹ-diaminobenzidine (BD-NH2) whereas only one equivalent of 1,2,4-benzenetriamine (PA-NH2) was sufficient to promote the conversion of mother COF PTBD to daughter COF PTPA-NH2 (Figure 35). The use of a higher amount of BD-NH2 (10 equiv.) to achieve the COF transformation was attributed to the higher activity of PA-NH2 than that of BD-NH2. It is noteworthy to mention that these amino-functionalized COFs were unobtainable by de nova synthesis where only amorphous materials were obtained.

Figure 35.

Construction of amino-functionalized COFs through linker exchange strategy. Reprinted from ref 153 with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

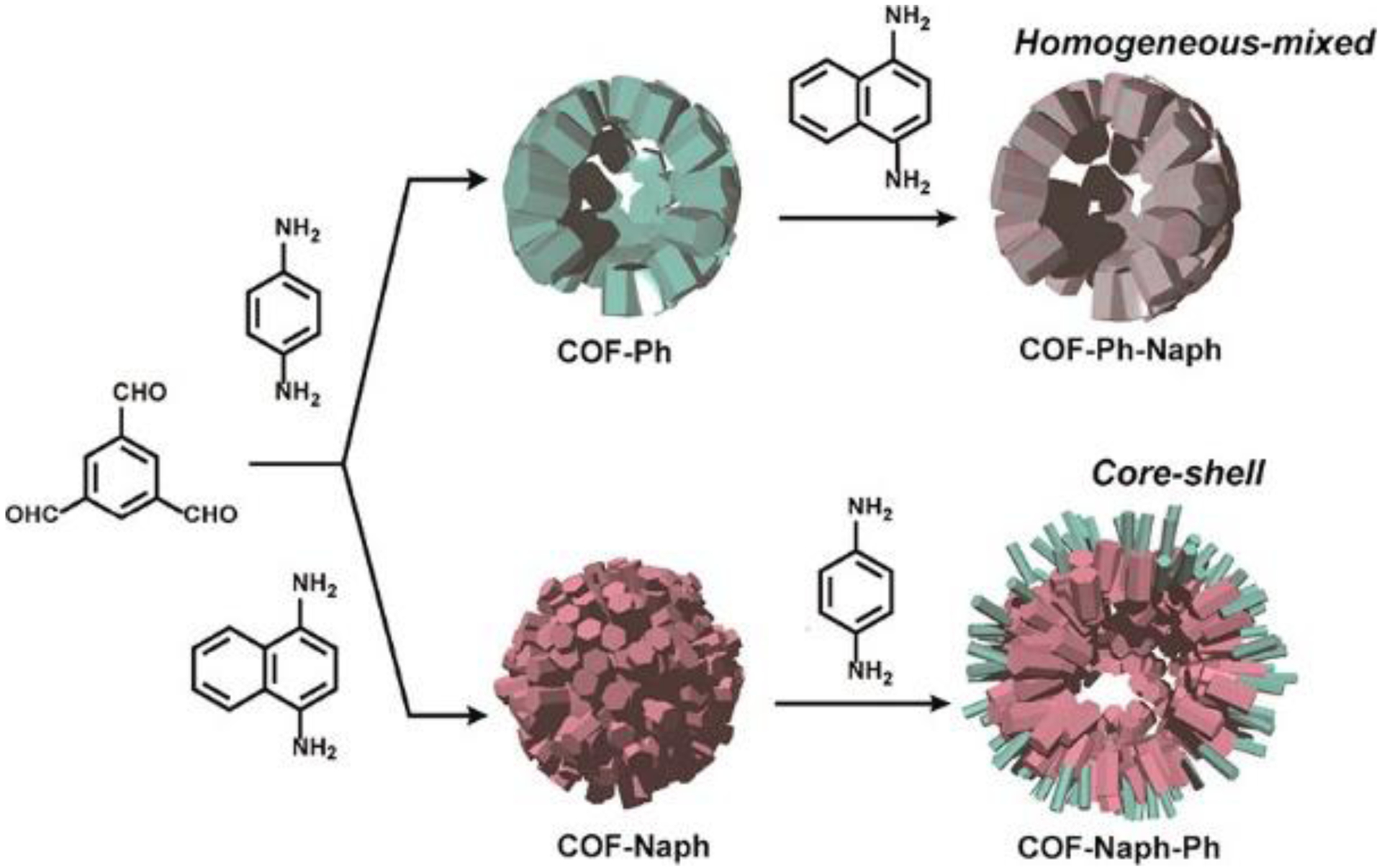

Another fascinating example of DCC guided linker exchange in COFs was demonstrated by Kitagawa, Horike, and coworkers.153 Unlike the full replacement in the previous two examples, partial linker exchange was shown to give two hierarchical structures: homogeneously mixed-linker structured COF-Ph-Naph and heterogeneously core–shell hollow structured COF-Naph-Ph (Figure 36). The second linker was incorporated into the parent COFs in a controllable manner by varying the linker feeding concentrations. The incorporation of phenylenediamine was found to be 20%, 26%, and 36%, of the total amine linkers in COF-Naph-Ph, when 1, 2, and 4 equivalents of this monomer were used for exchange, respectively. 1,4-diaminonaphthalene was shown to be incorporated in COF-Ph-Naph in a higher ratio of 37%, 58%, 73% when 1, 2, and 4 equivalents of it were applied, respectively. The formation of a core-shell hollow structure was accredited to the partial dissolution of the COF-Naph followed by the recrystallization of COF-Ph on the surface of the hollow structure. Delightedly, the BET surface areas of both the tailored materials were 2-fold greater than their parent COFs because of improved crystallinity. Moreover, the core-shell structured COF-Naph-Ph exhibited a two-step adsorption isotherm for H2O, distinct from the sigmoidal isotherms of COF-Ph, COF-Naph, COF-Ph-Naph and the physical mixture of COF-Ph and COF-Naph.

Figure 36.

The construction of homogeneous mixed-linker structured COF-Ph-Naph and core-shell hollow structured COF-Naph-Ph. Reprinted with permission from ref 154. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

Later, Zhao, Zeng, and coworkers demonstrated that DCC induced linker exchange can convert nonporous covalent organic polymers (COPs) to crystalline COFs.154 By reacting imine linked COP-1 with an excess of substituted terephthalaldehydes in o-dichlorobenzene/n-butanol/6M AcOH, four imine-linked COFs were produced (Figure 37). COP-1 exhibited a low surface area of 13.8 m2 g−1. Whereas all the four COFs showed very high surface areas ranging from 1862 to 2536 m2 g−1.

Figure 37.

Transformation of COPs to COFs. Reprinted with permission from ref 155. Copyright 2019 Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Apart from the simple linkage-conservative paradigm, linkage transformation upon linker replacement are also possible in COFs. Yaghi and coworkers reported the first example of such transformations by converting an imine linked COF to benzoxazole and benzothiazole linked COFs (Figure 38).155 The reaction of imine linked ILCOF-1 with 2,5 diaminobenzene-1,4-dithiol dihydrochloride under an oxygen environment afforded benzothiazole linked COF-921. Similarly, the reaction of ILCOF-1 with 2,5-diaminohydroquinone dihydrochloride led to the formation of benzoxazole linked LZU-192. The overall framework structure of the material was maintained after the transformation. A moderate drop in surface area from 2050 m2 g−1 for the original ILCOF-1 to 1550 m2 g−1 for COF-921 and 1770 m2 g−1 for LZU-192 was observed, respectively. Nevertheless, greatly improved chemical stability was observed for COF-921 and LZU-192 than for ILCOF-1. For example, both COF-921 and LZU-192 were stable towards strong base (10 M NaOH) and acids (18 M H2SO4, 14.8 M H3PO4) while ILCOF-1 was hydrolyzed significantly. The presence of both water and oxygen were found to be crucial for the linkage transformation. Water promoted the hydrolysis, and oxygen forced the subsequent oxidative cyclization to obtain the transformed COFs.

Figure 38.

Transformation of an imine linked COF to benzoxazole and benzothiazole linked COFs. Reprinted with permission from ref 156. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

Banerjee’s group introduced β-ketoenamine-linked COFs which have since drawn great attention because of the much improved stability compared to imine linked COFs.156 However, the irreversible tautomerism limits the error correction in the crystallization process thus compromising crystallinity and porosity. Dichtel and coworkers reported an upgraded synthesis of β-ketoenamine-linked COFs via monomer exchange of 1,3,5-triformylbenzene (TFB) in pre-synthesized imine COFs to triformylphloroglucinol (TFP).157 Five β-ketoenamine-linked COFs were successfully made from this approach with both C2 and C3 symmetrical amine linkers, demonstrating the generality of this method (Figure 39). With DAFL-TFP-COF being the only exception, all the COFs made by linker exchange had higher surface areas than the directly synthesized COFs. The most dramatic example was BND-TFP-COF which had a surface area increase from 492 m2 g−1 to 1536 m2 g−1.

Figure 39.

DCC induced upgraded synthesis of β-ketoenamine-linked COFs.

Later, Zhao, Zeng, and coworkers reported the conversion of an imine-linked COP to an imide-linked COF.158 Imine linked COP-1was converted into two imide-linked COFs: NaTAn-TTA-COF when reacted with 1,4,5,8-naphthalenetetracarboxylic anhydride (NaTAn) or PmDAn-TTA-COF when reacted with pyromellitic dianhydride (Figure 40). The obtained COFs showed a surface area of 1089 m2 g−1 for NaTAn-TTA-COF and 1026 m2 g−1 for PmDAn-TTA-COF, respectively. Similarly, imide-linked COP-2 was converted to two imine-linked COFs, 2,3-Dha-TTA-COF and 2,5-Dha-TTA-COF with a surface area of 1654 m2g−1 and 2597 m2g−1, respectively.

Figure 40.

Transformation of imine-linked COP to imide-linked COFs and imide-linked COP to imine-linked COFs.

Very recently, Cai, Feyter, and coworkers reported a rare mechanistic study of the linkage transformation process.159 By applying an oriented external electric field (EEF); in situ and real-time monitoring of the surface reaction dynamics with STM became possible. The STM analysis showed that the mixture of 1,3,5-tris(4-biphenylboronic acid)benzene (TBPBA) and HHTP first formed the kinetic product boroxine linked sCOFs-1 under a negative sample bias between STM tip and the sample (−0.2 to −0.7 V ). Then, sCOFs-1 slowly converted to the thermodynamic product sCOFs-2 via linker exchange with continuously applied negative sample bias. When a positive sample bias (0.2 to 0.7 V) was applied, depolymerization of the COFs to self-assembled molecular networks occurred (Figure 41).

Figure 41.

(A) Schematic illustration of external electric field triggered network switching among the self-assembled molecular network, sCOFs-1 and sCOFs-2; (B)-(F) STM images showing the time-dependent conversion process from sCOFs-1 to sCOFs-2 with Vbias = −0.3 V (green and blue hexagons represents the porous structures of sCOFs-1 and sCOFs-2, respectively); (G) Plot of the coverages of sCOFs-1 and sCOFs-2 against time. Reprinted with permission from ref 160. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

DCC induced linker exchange strategy to achieve modified COFs was not limited to 2D-COFs but was also applicable in 3D-COFs (Figure 42).160 For instance, it is possible to convert COF-320 into COF-300 by replacing the 4,4’-dicarbaldehyde in COF-320 with terephthaldehyde. Moreover, the dimensional transformation 3D to 2D was also achieved where the tetrahedral linker 4,4’,4”,4”’-methanetetrayltetraaniline in COF-301 was replaced by a trigonal C3 linker, TAPB, to furnish the 2D TPB-DHTP-COF.

Figure 42.

Linker exchange in 3D COFs and dimensionality transformation from 3D COF to 2D COF. Reprinted with permission from ref 161. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

Conclusion

The field of COF chemistry was developed only in the past decade but immense interest in the field has garnered a renewed focus on DCC. The fascinating crystallinity, porosity, and functionality of COFs offer them great potential in broad applications. The dynamic reversibility which manifests as a structural error-checking process during COF synthesis is essential for a successful COF synthesis. This same dynamic reversibility that enables COF synthesis can be further utilized to add structural and functional motifs through both in situ and post-synthetic modifications. The repetitive attaching and de-attaching of a monodentate modulator on the COF crystallite boundary slows down the crystal growth and strengthens the dynamic error checking, to the point that COF single crystals can be grown (section 1 modulation approach). Monomers with similar reactivity yet various functionalities or topologies can be incorporated into complex frameworks with attributes such as mixed linkers, built-in functions, or unprecedented pore structures (section 2 mixed linker/linkage approach). Unusual partial condensation reactions permit the formation of ordered networks with frustrated bonding that are not accessible via full condensation (section 3 sub-stoichiometric approach). Different COF framework isomers can be synthesized from the same starting materials by altering the experimental parameters and tuning reaction thermodynamics (section 4 isomerism). Post-synthetic linker exchange allows more opportunities to add functions or reinforce framework stability after the initial COF synthesis (section 5 linker exchange approach).

The exciting research field of COFs is still developing and facing a lot of challenges as well as opportunities. The research community has developed reliable methodologies for making polycrystalline or even single crystal COFs, yet the time, space, and energy efficiency of the synthesis needs improvement. For COFs to be used in trying industrial applications more efficient and sustainable synthetic procedures that produce highly uniform COFs must be developed.18,161 Mechanical force,162 microwaves,163 and electron beams164 are potential driving forces that might be more efficient than conventional solvothermal synthesis. Novel crystallization techniques such as polyelectrolyte solutions and shear flow enhanced crystal growth can also be a solution.165 Mixed linker COFs are usually synthesized through one-pot multi-component reactions and are assumed to have a homogenous distribution of the different linkers; however, it is not possible to confirm this based on the indirect characterization techniques such as PXRD, gas adsorption, TEM and simulation. Improving the crystallinity of mixed linker COFs via modulation would solve this question directly via electron diffraction tomography85 or single crystal X-ray diffraction. It is also of great interest to construct hierarchal architectures in a controllable fashion with a high level of linker mixing. Anisotropic epitaxial growth techniques could enable researchers to program such tailor-made novel COFs with nano-patterned structures, yet to be explored.166,167 Experiments with COF isomers would be an ideal way to explore structure-property relationships but better protocols must be developed for the selective synthesis of different COF isomers. On surface synthesis has been instrumental in confirming the fundamental models of DCC (e.g. optimal monomer concentration) and will continue providing more hints regarding the reaction thermodynamics and kinetics. Future studies should place emphasis on probing for new framework isomers (e.g. combination of tritopic and tetratopic linkers can form both 2D119,129,130 and 3D COFs168,169) and sub-stoichiometric polymerization (e.g. combination of tetratopic and hexatopic linkers). Work in these two areas will enrich the topological diversities of COFs.119 A detailed understanding of linker exchange mechanisms should be developed with both stepwise replacement and dissolution-recrystallization considered. The kinetics of diffusion, dissolution, and nucleation during COF synthesis are essential in this regard, hopefully a better understanding of these kinetics can help in the discovery of COFs with tunable composition and spatial distribution of linkers. The five DCC-based strategies laid out in this article should be used to discover COF synthesis protocols that expand the structural possibilities especially in the direction of new 3D topologies.24

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

M.H.B. gratefully acknowledges the financial support through the startup funds from the University of Arkansas and the NIH-NIGMS (GM132906).

REFERENCES

- (1).Rowan SJ; Cantrill SJ; Cousins GRL; Sanders JKM; Stoddart JF Dynamic Covalent Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2002, 41, 898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Jin Y; Yu C; Denman RJ; Zhang W Recent Advances in Dynamic Covalent Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 6634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Jin Y; Wang Q; Taynton P; Zhang W Dynamic Covalent Chemistry Approaches toward Macrocycles, Molecular Cages, and Polymers. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhang W; Jin Y Dynamic Covalent Chemistry: Principles, Reactions, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lehn J-M Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry and Virtual Combinatorial Libraries. Chem. Eur. J 1999, 5, 2455. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lehn J-M; Eliseev AV Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry. Science 2001, 291, 2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Corbett PT; Leclaire J; Vial L; West KR; Wietor J-L; Sanders JKM; Otto S Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry. Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cougnon FBL; Sanders JKM Evolution of Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res 2012, 45, 2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Côté AP; Benin AI; Ockwig NW; O’Keeffe M; Matzger AJ; Yaghi OM Porous, Crystalline, Covalent Organic Frameworks. Science 2005, 310, 1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Feng X; Ding X; Jiang D Covalent Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev 2012, 41, 6010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ding S-Y; Wang W Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs): From Design to Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Waller PJ; Gándara F; Yaghi OM Chemistry of Covalent Organic Frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Segura JL; Mancheño MJ; Zamora F Covalent Organic Frameworks Based on Schiff-Base Chemistry: Synthesis, Properties and Potential Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45, 5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Huang N; Wang P; Jiang D Covalent Organic Frameworks: A Materials Platform for Structural and Functional Designs. Nat. Rev. Mater 2016, 1, 16068. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Diercks CS; Yaghi OM The Atom, the Molecule, and the Covalent Organic Framework. Science 2017, 355, eaal1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jin YH; Hu YM; Zhang W Tessellated Multiporous Two-Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks. Nat. Rev. Chem 2017, 1, 11. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lohse MS; Bein T Covalent Organic Frameworks: Structures, Synthesis, and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater 2018, 28, 1705553. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Peh SB; Wang Y; Zhao D Scalable and Sustainable Synthesis of Advanced Porous Materials. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng 2019, 7, 3647. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Segura JL; Royuela S; Mar Ramos M Post-Synthetic Modification of Covalent Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev 2019, 48, 3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wang H; Zeng ZT; Xu P; Li LS; Zeng GM; Xiao R; Tang ZY; Huang DL; Tang L; Lai C; Jiang DN; Liu Y; Yi H; Qin L; Ye SJ; Ren XY; Tang WW Recent Progress in Covalent Organic Framework Thin Films: Fabrications, Applications and Perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev 2019, 48, 488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kandambeth S; Dey K; Banerjee R Covalent Organic Frameworks: Chemistry Beyond the Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Chen X; Geng K; Liu R; Tan KT; Gong Y; Li Z; Tao S; Jiang Q; Jiang D Covalent Organic Frameworks: Chemical Approaches to Designer Structures and Built-in Functions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Alahakoon SBB; Diwakara SDD; Thompson CMM; Smaldone RAA Supramolecular Design in 2D Covalent Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev 2020, 49, 1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Guan X; Chen F; Fang Q; Qiu S Design and Applications of Three Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev 2020, 49, 1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Geng K; He T; Liu R; Dalapati S; Tan KT; Li Z; Tao S; Gong Y; Jiang Q; Jiang D Covalent Organic Frameworks: Design, Synthesis, and Functions. Chem. Rev 2020, 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rodríguez-San-Miguel D; Montoro C; Zamora F Covalent Organic Framework Nanosheets: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2020, 49, 2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rogge SMJ; Bavykina A; Hajek J; Garcia H; Olivos-Suarez AI; Sepúlveda-Escribano A; Vimont A; Clet G; Bazin P; Kapteijn F; Daturi M; Ramos-Fernandez EV; Llabrés i Xamena FX; Van Speybroeck V; Gascon J Metal–Organic and Covalent Organic Frameworks as Single-Site Catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hu H; Yan Q; Ge R; Gao Y Covalent Organic Frameworks as Heterogeneous Catalysts. Chin. J. Catal 2018, 39, 1167. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Guo LP; Jin SB Stable Covalent Organic Frameworks for Photochemical Applications. ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 973. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Zhang T; Xing G; Chen W; Chen L Porous Organic Polymers: A Promising Platform for Efficient Photocatalysis. Mater. Chem. Front 2020, 4, 332. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Liu JG; Wang N; Ma LL Recent Advances in Covalent Organic Frameworks for Catalysis. Chem. Asian J 2020, 15, 338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ozdemir J; Mosleh I; Abolhassani M; Greenlee LF; Beitle RR; Beyzavi MH Covalent Organic Frameworks for the Capture, Fixation, or Reduction of CO2. Front. Energy Res 2019, 7, 77. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Qian HL; Yang CX; Wang WL; Yang C; Yan XP Advances in Covalent Organic Frameworks in Separation Science. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1542, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Yuan SS; Li X; Zhu JY; Zhang G; Van Puyvelde P; Van der Bruggen B Covalent Organic Frameworks for Membrane Separation. Chem. Soc. Rev 2019, 48, 2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wang ZF; Zhang SN; Chen Y; Zhang ZJ; Ma SQ Covalent Organic Frameworks for Separation Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2020, 49, 708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Zhang XL; Li GL; Wu D; Zhang B; Hu N; Wang HL; Liu JH; Wu YN Recent Advances in the Construction of Functionalized Covalent Organic Frameworks and Their Applications to Sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron 2019, 145, 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Zhang YE; Riduan SN; Wang JQ Redox Active Metal- and Covalent Organic Frameworks for Energy Storage: Balancing Porosity and Electrical Conductivity. Chem. Eur. J 2017, 23, 16419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Miner EM; Dincă M Metal- and Covalent-Organic Frameworks as Solid-State Electrolytes for Metal-Ion Batteries. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2019, 377, 20180225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Cao S; Li B; Zhu RM; Pang H Design and Synthesis of Covalent Organic Frameworks Towards Energy and Environment Fields. Chem. Eng. J 2019, 355, 602. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Zheng WR; Tsang CS; Lee LYS; Wong KY Two-Dimensional Metal-Organic Framework and Covalent-Organic Framework: Synthesis and Their Energy-Related Applications. Mater. Today Chem 2019, 12, 34. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kong L; Zhong M; Shuang W; Xu Y; Bu X-H Electrochemically Active Sites inside Crystalline Porous Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev 2020, 49, 2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Zhao FL; Liu HM; Mathe SDR; Dong AJ; Zhang JH Covalent Organic Frameworks: From Materials Design to Biomedical Application. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Sakamaki Y; Ozdemir J; Heidrick Z; Watson O; Shahsavari HR; Fereidoonnezhad M; Khosropour AR; Beyzavi MH Metal-Organic Frameworks and Covalent Organic Frameworks as Platforms for Photodynamic Therapy. Comments Inorg. Chem 2018, 38, 238. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Chedid G; Yassin A Recent Trends in Covalent and Metal Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Scicluna MC; Vella-Zarb L Evolution of Nanocarrier Drug-Delivery Systems and Recent Advancements in Covalent Organic Framework–Drug Systems. ACS Appl. Nano Mater 2020, 3, 3097. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Guan Q; Zhou L-L; Li W-Y; Li Y-A; Dong Y-B Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) for Cancer Therapeutics. Chem. Eur. J 2020, 26, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Rodriguez-San-Miguel D; Zamora F Processing of Covalent Organic Frameworks: An Ingredient for a Material to Succeed. Chem. Soc. Rev 2019, 48, 4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Song Y; Sun Q; Aguila B; Ma S Opportunities of Covalent Organic Frameworks for Advanced Applications. Adv. Sci 2019, 6, 1801410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Uribe-Romo FJ; Hunt JR; Furukawa H; Klöck C; O’Keeffe M; Yaghi OM A Crystalline Imine-Linked 3-D Porous Covalent Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 4570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Uribe-Romo FJ; Doonan CJ; Furukawa H; Oisaki K; Yaghi OM Crystalline Covalent Organic Frameworks with Hydrazone Linkages. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 11478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Dalapati S; Jin S; Gao J; Xu Y; Nagai A; Jiang D An Azine-Linked Covalent Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 17310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Fang Q; Zhuang Z; Gu S; Kaspar RB; Zheng J; Wang J; Qiu S; Yan Y Designed Synthesis of Large-Pore Crystalline Polyimide Covalent Organic Frameworks. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Jin E; Asada M; Xu Q; Dalapati S; Addicoat MA; Brady MA; Xu H; Nakamura T; Heine T; Chen Q; Jiang D Two-Dimensional sp2 Carbon–Conjugated Covalent Organic Frameworks. Science 2017, 357, 673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Guan X; Li H; Ma Y; Xue M; Fang Q; Yan Y; Valtchev V; Qiu S Chemically Stable Polyarylether-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks. Nat. Chem 2019, 11, 587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Zhang B; Wei M; Mao H; Pei X; Alshmimri SA; Reimer JA; Yaghi OM Crystalline Dioxin-Linked Covalent Organic Frameworks from Irreversible Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 12715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Lyu H; Diercks CS; Zhu C; Yaghi OM Porous Crystalline Olefin-Linked Covalent Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 6848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Acharjya A; Pachfule P; Roeser J; Schmitt F-J; Thomas A Vinylene-Linked Covalent Organic Frameworks by Base-Catalyzed Aldol Condensation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 14865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Wei S; Zhang F; Zhang W; Qiang P; Yu K; Fu X; Wu D; Bi S; Zhang F Semiconducting 2D Triazine-Cored Covalent Organic Frameworks with Unsubstituted Olefin Linkages. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 14272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Jadhav T; Fang Y; Patterson W; Liu C-H; Hamzehpoor E; Perepichka DF 2D Poly(Arylene Vinylene) Covalent Organic Frameworks via Aldol Condensation of Trimethyltriazine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 13753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Hermes S; Witte T; Hikov T; Zacher D; Bahnmüller S; Langstein G; Huber K; Fischer RA Trapping Metal-Organic Framework Nanocrystals: An in-Situ Time-Resolved Light Scattering Study on the Crystal Growth of MOF-5 in Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 5324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Tsuruoka T; Furukawa S; Takashima Y; Yoshida K; Isoda S; Kitagawa S Nanoporous Nanorods Fabricated by Coordination Modulation and Oriented Attachment Growth. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 4739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Diring S; Furukawa S; Takashima Y; Tsuruoka T; Kitagawa S Controlled Multiscale Synthesis of Porous Coordination Polymer in Nano/Micro Regimes. Chem. Mater 2010, 22, 4531. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Schaate A; Roy P; Godt A; Lippke J; Waltz F; Wiebcke M; Behrens P Modulated Synthesis of Zr-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks: From Nano to Single Crystals. Chem. Eur. J 2011, 17, 6643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Stock N; Biswas S Synthesis of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Routes to Various MOF Topologies, Morphologies, and Composites. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Smith BJ; Dichtel WR Mechanistic Studies of Two-Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks Rapidly Polymerized from Initially Homogenous Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 8783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]