Abstract

γ-Secretase is one of two proteases directly involved in the production of the amyloid β-peptide, (Aβ) which is pathogenic in Alzheimer’s disease. Inhibition of γ-secretase to suppress the production of Aβ should not block processing of one of its alternative substrates, Notch1 receptors, as interference with Notch1 signaling leads to severe toxic effects. In the course of our studies to identify γ-secretase inhibitors with selectivity for APP over Notch, 1 [3-(benzyl(isopropyl)amino)-1-(naphthalen-2-yl)propan-1-one] was found to inhibit γ-secretase-mediated Aβ production without interfering with γ-secretase-mediated Notch processing in purified enzyme assays. As 1 is chemically unstable, efforts to increase the stability of this compound led to the identification of 2 [naphthalene-2-carboxylic acid benzyl-isopropyl-amide] which showed similar biological activity to compound 1. Synthesis and evaluation of a series of amide analogs resulted in benzofuranoyl amide analogs that showed promising Notch-sparing γ-secretase inhibitory effects. This class of compounds may serve as a novel lead series for further study in the development of γ-secretase inhibitors.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, γ-secretase inhibitors, Naphthyl amides, Notch processing, Aβ production

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by neurodegeneration and progressive deterioration of memory and cognitive abilities. At present, there is no cure or effective treatment for this disease, only several approved drugs for alleviating certain AD symptoms. Over the past 20 years, advances in deciphering AD pathology have revealed that AD is a protein-misfolding disorder,1 as aggregation of the amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) in the brain is a central event in AD pathology.2 Aβ proteins are produced naturally inside the human brain as proteolytic products of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) through sequential cleavages mediated by β- and γ-secretases. Secreted Aβ varies in length ranging from 37-43 amino acids,3 of which the 42 amino acid peptide (Aβ42) is especially prone to aggregation when over-produced or normal clearance is interrupted.2 Aβ dimers and higher order assemblies can initiate a series of cellular events that can ultimately cause neuronal dysfunctions and the onset and progression of AD.4 Based on the Aβ hypothesis of AD-pathogenesis, several disease-modifying approaches have been proposed, including suppression of Aβ production, prevention of Aβ aggregation and promotion of Aβ clearance.5

Suppressing Aβ production through inhibition of γ-secretase has been aggressively pursued as a potential disease-modifying approach. However, γ-secretase is a multifunctional protease with many substrates including the essential cell-signaling Notch receptors.6 Hence, identification of γ-secretase inhibitors or modulators that can lower Aβ production in general or Aβ42 in particular with minimal effects on Notch signaling (particularly that of Notch1) has become one of the most prominent challenges in the pursuit of AD therapeutics.3 While much progress has been made toward Aβ42-lowering γ-secretase modulators,7-9 various ‘Notch-sparing’ γ-secretase inhibitors have been reported,8,10-13 and even for these the degree of selectivity for APP versus Notch1 is often unclear. Thus, there is a keen need to identify new structures with this important substrate-selective inhibitory property as demonstrated in comparable biochemical assays.

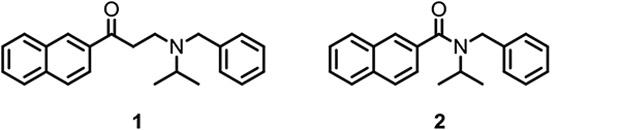

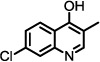

In search of such compounds, one of our earliest hits was naphthylaminoalkyl ketone 1.14 Unfortunately, 1 is unstable and subject to degradation by a retro-Michael-addition to give the corresponding naphthyl vinyl ketone and N-benzylisopropylamine. One attempt to seek more stable analogs of 1 was to generate its amide counterpart 2 (Figure 1), with the ethylene linker between the carbonyl and amine nitrogen removed. This compound 2 showed similar biological activity to 1. Evaluation of various drug-like properties (e.g., solubility, LogD, plasma protein binding, permeability, and human and rodent microsomal stability – See Supplemental Data) of 2 was completed and the results indicated a reasonable profile to begin synthesizing analogs. A series of these amide analogs were synthesized as illustrated in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 1.

Naphthyl aminoalkyl ketone 1 and naphthyl amide 2

Table 1.

Naphthyl amides

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | Aβ40 (%) Inhibition a |

Notch1 Processing b |

| 2 | i-Pr | 58 | No change |

| 3 | H | 0 | n.t. |

| 4 | CH3 | 15 | n.t. |

| 5 | t-Bu | 52 | No change |

| 6 | cyclic-Pr | 37 | No change |

n.t. = not tested

See References and Notes sections for assay descriptions

Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Inhibitory effects on Aβ40 production were recorded as a percentage in comparison with DMSO control.

Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Effects on Notch processing were recorded (Western Blot) in comparison with DMSO control.

Table 2.

Aryl amide analogs replacing the 2-naphthyl group

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ar | Aβ40 (%) Inhibitiona |

Notch1 Processing b |

| 2 | 58 | No change | |

| 7 |  |

67 | No change |

| 8 | 10 | n.t. | |

| 9 |  |

85 | Inhibition |

| 10 |  |

27 | n.t. |

| 11 | 14 | n.t. | |

| 12 | 40 | No change | |

| 13 |  |

0 | n.t. |

| 14 | 50 | Inhibition | |

| 15 |  |

33 | No change |

| 16 | 50 | Inhibition | |

See Table 1 notes, n.t. = not tested.

Table 3.

Naphthyl amide analogs with substituted phenyl rings

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | Aβ40 (%) Inhibitiona |

Notch1 Processing b |

| 17 | H | H | Cl | Cl | 58 | No change |

| 18 | OH | H | Cl | Cl | 41 | No change |

| 19 | H | H | F | F | 34 | No change |

| 20 | OH | H | F | F | 49 | No change |

| 21 | H | F | H | F | 21 | n.t. |

| 22 | OH | F | H | F | 27 | n.t. |

| 23 | H | H | OMe | H | 47 | Inhibition |

| 24 | OH | H | OMe | H | 33 | No change |

| 25 | H | CN | H | H | 31 | n.t. |

| 26 | H | H | CN | H | 31 | n.t. |

| 27 | H | OMe | H | OMe | 35 | No change |

| 28 | H | OMe | H | H | 19 | No change |

| 29 | H | H | H | 38 | Inhibition | |

See Table 1 notes, n.t. = not tested.

Table 4.

Benzofuranoyl amide analogs

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R7 | R8 | R9 | R’° | Αβ40 (%) Inhibitiona |

Notch 1 Processing b |

| 30 | H | H | H | H | 40 | No change |

| 31 | H | H | Cl | Cl | 51 | No change |

| 32 | H | Me | Cl | Cl | 0 | n.t. |

| 33 | OMe | H | Cl | Cl | 75 | No change |

| 34 | OMe | H | Cl | F | 49 | No change |

| 35 | OMe | H | F | Cl | 23 | No change |

| 36 | OEt | H | Cl | Cl | 58 | No change |

See Table 1 notes, n.t. = not tested.

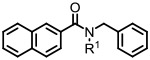

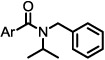

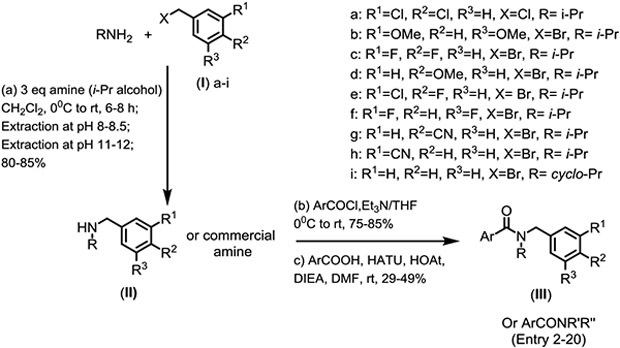

These aryl amides were synthesized by the methods illustrated in Scheme 1. Alkylation of readily available amines (i.e., isopropyl or cyclopropyl amine) with various substituted benzyl halides was carried out at 0°C to room temperature for 6-8 h. Excess amine was then removed in vacuo. The crude product contained ~10-15% of the undesired dialkylated product which was easily removed by an aqueous-organic partitioning at pH 8-8.5. The desired mono-alkylated amine (II) was obtained by subsequent extraction at pH 11-12. Coupling of amine (II) or commercially available amine with either acyl chlorides or aryl acids yielded the desired target amide analogs (III).

Scheme 1.

Preparation of aryl amides

These amides were then evaluated for their inhibitory effects on Aβ40 production from purified human γ-secretase15 and a recombinant APP-based substrate using a specific ELISA.16,17,18 Effects on γ-secretase processing of a comparable recombinant Notch1-based substrate were examined by Western blot.14 Compounds with >50% inhibition in the Aβ40 ELISA were typically evaluated for their effects on Notch processing. Since our goal in the early stages of our program was to identify viable chemical leads, testing our new analogs at a high concentration in search for at least 50% inhibition of Aβ production without effect on Notch1 cleavage led to some novel compounds and chemical series that are now being presented here and in subsequent manuscripts.

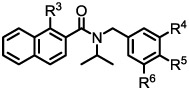

Initial variations of the isopropyl group of 1 revealed that substitution on this nitrogen is essential for activity (e.g., 3 vs. 2; Table 1) Moreover, the size of this R1 seems important since 5 (t-butyl) and 6 (cyclopropyl) maintained inhibition of Aβ40 production (52% and 37%, respectively) while a methyl-substituted analog (4) was less active (15%).

These preliminary modifications suggested that at least the size of an iso-propyl group is preferred for the inhibition of Aβ40 production. Analogs 2, 5, and 6 also showed no effect on Notch processing. This was encouraging data and convinced us to then turn our attention to replacing the naphthyl group with other aryl groups (Table 2) and investigating various substitution patterns on the phenyl ring (Table 3)

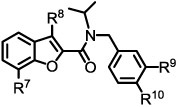

The results suggested some structural features that may be necessary for exhibiting Notch 1-sparing properties and inhibition of Aβ40 production. Notably, when the naphthyl group was replaced with a phenyl ring, activity was markedly reduced (8, 10%; Table 2). However, when a 4-t-butyl group was introduced on the phenyl ring, activity on the inhibition of APP processing was enhanced (9, 85%), but the desired Notch1-sparing property was lost. These results suggest that a bulky group or larger ring system may be needed to make a tight interaction with the binding site. Introducing a hydroxyl group on aromatic rings adjacent to the amide carbonyl group (e.g., 7 and 15) likely leads to the formation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the hydroxyl and the amide carbonyl, a notion supported by 1 H NMR. Two sets of signals were seen for compounds without the OH, consistent with two amide rotomeric forms, as typically observed by NMR. In contrast, only one set of signals was observed for those analogs with the OH, consistent with conformation restriction due to H-bonding.

From the data shown in Table 2, it appeared that better activity was observed when the aryl (Ar) group was larger in size consisting of two fused rings or had larger substituents on a ring. And, in general, fused bicyclic aryl groups appear to be preferred for selectivity versus Notch1-processing.

Analogs with various substitution patterns (R4, R5, and R6) on the phenyl group were studied and the results are shown in Table 3. Maintaining a di-chloro substitution pattern at R9 and R10 with R8 equal to hydrogen seemed to yield the better activity profile.

The findings from the above studies were incorporated into some of the benzofuranyl analogs shown in Table 4.

In this group of compounds, 3,4-dihalogenated analogs also exhibited good inhibitory effects on Aβ production. Interestingly, introducing a methyl group at the 3-position (R8) on the benzofuran ring completely abolished the activity (32 vs 31). This observation could suggest that the orientation of the amide bound with respect to the benzofuran ring may be critical for activity. Additionally, replacing a chlorine substituent with a fluorine substituent (35) for R9 reduced activity (33 vs 35). It is encouraging to note that benzofuranyl amides consistently exhibited Notch-sparing properties while displaying promising inhibitory effects on γ-secretase-mediated Aβ production.

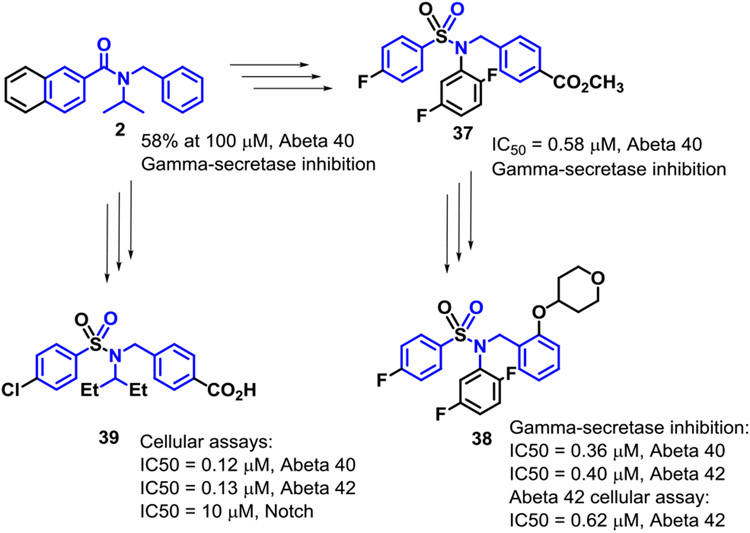

This early-stage SAR study of naphthyl and benzofuranyl amide analogs led to diaryl amides that were found to inhibit Aβ40 production mediated by γ-secretase. In particular, the naphthalene-2-yl and benzofuran-2-yl amides displayed Notch 1-sparing properties. Additional Abeta 42 cellular data was obtained for many of the compounds that exhibited >50% inhibition in the gamma secretase assay (See Supplemental Data). Showing weak activity allowed us to search diligently for a modified diaryl amide core that exhibited increased potency. Thus, converting the amide to a sulfonamide and exploring various substation patterns gave analogs such as 37, 38, and 39, just a few of the examples synthesized (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Evolution of Amide 2

In summary, it was from the discovery of this amide series that led to sulfonamide analogs (that were potent against gamma-secretase as well as in cells against Abeta 40 and Abeta 42). Some of these analogs (e.g., 39) were later tested in vivo in animals from which these results will be reported. These findings have the potential to lead to a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease that ultimately may show differentiation from previously failed clinical candidates.

The results reported here were generated while our laboratories continued to search for additional templates that could be used for developing Notch1-sparing γ-secretase inhibitors. Findings of additional identified templates of chemical series are reported in subsequent manuscripts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jian Chen and Katherine M. Brogan for their assistance with the biological testing. We acknowledge the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, the Harvard NeuroDiscovery Center and members of the Center for Neurologic Diseases for funding support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In Vitro γ-Secretase Activity Assay. Human γ-secretase complex was purified from Chinese Hamster ovary cells stably overexpressing all four components.15 APP-based γ-secretase substrate (C100-Flag) and Notch-based substrate (N100-Flag) was expressed in E. coli and purified as previously described.16,17 The tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO, and then prepared with the final concentration of 100 μM in the reaction buffer of 0.2% CHAPSO/HEPES (pH 7.0) with final DMSO concentration less than 1%. The proteolytic reaction mixtures containing purified γ-secretase complex, 0.08% phosphatidylcholine, 0.02% phosphatidylethanol-amine, tested compounds, and substrate C100-Flag or N100-Flag were then incubated at 37°C for 4 h. All reactions were stopped by adding SDS to a final concentration of 0.5%. The reactions employing the substrate of C100-Flag were evaluated for inhibition of Aβ40 production by ELISA using commercial human Aβ40 antibodies (Invitrogen),18 whereas the reactions using the substrate of N100-Flag were analyzed by Western blots for effects on Notch1 processing as previously reported.14

References

- 1.Selkoe DJ Cold Spring Harbor: Perspectives in Biology 2011, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karran E; Mercken M; De Strooper B Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe MS Neurotherapeutics 2008, 5, 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galimberti D; Scarpini E Front Biosci. (School Ed.) 2011, 3,252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangialasche F; Solomon A; Winblad B; Mecocci P; Kivipelto M Lancet Neurology 2010, 9, 702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfe MS Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2009, 20,219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pettersson M; Kauffman GW; am Ende CW; Patel NC; Stiff C; Tran TP; Johnson DS Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2011, 21, 205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imbimbo BP; Giardina GA Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2011, 11, 1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oehlrich D; Berthelot DJ; Gijsen HJ J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreft AF; Martone R; Porte AJ Med. Chem 2009, 52, 6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson RE; Albright CF Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2008, 8, 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pissarnitski D Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel 2007, 10, 392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imbimbo BP Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2008, 8, 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraering PC; Ye W; LaVoie MJ; Ostaszewski BL; Selkoe DJ; Wolfe MS J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 41987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraering PC; Ye W; Strub JM; Dolios G; LaVoie MJ; Ostaszewski BL; van Dorsselaer A; Wang R; Selkoe DJ; Wolfe MS Biochemistry 2004, 43, 9774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esler WP; Kimberly WT; Ostaszewski BL; Ye W; Diehl TS; Selkoe DJ; Wolfe MS Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2002, 99, 2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimberly WT; Esler WP; Ye W; Ostaszewski BL; Gao J; Diehl T; Selkoe DJ; Wolfe MS Biochemistry 2003, 42, 137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia W; Zhang J; Ostaszewski BL; Kimberly WT; Seubert P; Koo EH; Shen J; Selkoe DJ Biochemistry 1998, 37, 16465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.