Abstract

In clinical trials in populations with Mild Cognitive Impairment, it is common for participants to initiate concurrent symptomatic medications for Alzheimer’s after randomization to the experimental therapy. One strategy for dealing with this occurrence is to censor any observations that occur after the concurrent medication is initiated. The rationale for this approach is that these observations might reflect a symptomatic benefit of the concurrent medication that would adversely bias efficacy estimates for an effective experimental therapy. We interrogate the assumptions underlying such an approach by estimating the effect of newly prescribed concurrent medications in an observational study, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

Keywords: clinical trials, Alzheimer’s, intercurrent events, concurrent medication, symptomatic medication

The draft ICH E9 (R1) addendum on estimands and sensitivity analysis in clinical trials to the guideline on statistical principles for clinical trials1 recently published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as well as the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has sparked much debate among Alzheimer’s clinical trialists on the appropriate handling of intercurrent events, such as initiation of concurrent medications. This is a common event in clinical trials in populations with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in which many subjects are naïve to approved symptomatic Alzheimer’s drugs at randomization. Many patients will typically start concomitant symptomatic treatment after randomization. For example in a recently reported Phase 3 study of 799 prodromal Alzheimer’s patients 46 (5.8%) patients had initiated an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChEI) or memantine treatment at the time of futility analysis2. If the study had completed 2-year follow-up as planned, we would expect up to 10% of placebo patients to have initiated symptomatic treatment during the trial. Symptomatic drugs used in clinical practice include donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine, aricept, namenda, razadyne, and exelon.

The currently approved symptomatic drugs have demonstrated modest clinical efficacy in moderate to severe stages of AD dementia3. Prior studies in populations with mild-to-moderate or severe dementia have demonstrated that participants on the combination of AChEIs and memantine experience lesser decline on cognitive and functional measures than those on either AChEIs alone or neither medication4,5. In a randomized trial of donepezil over 24 weeks in N=262 participants with MCI, a mean benefit compared to placebo of about 1.4 points (p<0.05) on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) was observed6. However in a larger 3 year trial of donepezil, no effects on ADAS-Cog, Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), or Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) persisted beyond 18 months7. Given the potential short-term cognitive benefits, it remains unclear whether allowing the use of AChEIs, memantine, or combined therapy in randomized clinical trials can affect the assessment of efficacy of novel therapeutic agents.

The ICH E9 (R1) addendum discusses the handling of intercurrent events in the context of the construction of estimands, or targets of estimation. For example, under the “treatment policy strategy”, we would attempt to collect and analyze data until the end of the planned observation period, irrespective of intercurrent events. But under a “hypothetical strategy”, we might censor, or ignore, data collected after the event to attempt to estimate what the effect might have been in absence of the intercurrent event.

One important intercurrent event in clinical trials in MCI populations is the initiation of symptomatic drugs. Historically, patients were often asked to discontinue from the study if they started a symptomatic treatment, censoring all post-intercurrent event observations and yielding a hypothetical estimand. The alternative treatment policy approach would include data after initiation of symptomatic drugs. One might be concerned that more subjects randomized to placebo might initiation symptomatic drugs compared to those randomized to an effective experimental therapy. And with the benefit of symptomatic drugs, the placebo group might appear closer to the active group, and power to detect the effect of the experimental drug will be reduced compared to a hypothetical strategy. For this reason, the EMA Guideline on the clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease8 concedes that an appropriate target of estimation with regard to new or modified concomitant medication could be based on a hypothetical strategy, despite generally recommending a “treatment-policy” strategy for other intercurrent events.

We demonstrate, using data from an observational study, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)9, that this concern might be unwarranted. While symptomatic drugs have demonstrated their modest benefits in randomized trials7,10, it is unclear how this benefit compares to the decline that precipitates their prescription in the course of typical clinical care. Schneider et al.11 observed that use of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine was associated with greater decline in ADNI. We further interrogate this observation using updated data from ADNI and consider implications in the context of a treatment policy estimand.

Methods

Data

We use natural history data from the prospective observational cohort study Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)12. The inclusion and exclusion criteria, schedule of assessments, and other details can be found at adni.loni.usc.edu. Data for this analysis were downloaded from adni.loni.usc.edu on April 8, 2019. We include all ADNI participants who began ADNI diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), including Early MCI (EMCI). Symptomatic medications include any reported prescriptions of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine, or tacrine. For longitudinal outcome measures, we considered the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog)13,14 (including Delayed Word Recall and Number Cancellation), Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB)15, and Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE)16.

Statistical Methods

We summarize the baseline characteristics of ADNI MCI participants who never initiated, and those who did initiate symptomatic therapy with means, standard deviations, counts, and percentages. The two groups are compared at baseline using Pearson’s χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test. Longitudinal data for those who were prescribed symptomatic medication are summarized with spaghetti plots with Locally Estimated Scatter Plot Smoothing in which the horizontal axis is the time since initiation of symptomatic medication in years (i.e. time of first reported of the use of a symptomatic drug is time 0).

We apply the Mixed Model of Repeated Measures (MMRM)17 to change scores with baseline score, APOEε4 status (0 if no ε4 alleles, 1 otherwise), and age as covariates. Prior to fitting the models, we apply one of two censoring rules: (1) no censoring (consistent with a “treatment policy” approach), or (2) censoring all data after the initiation of symptomatic medication (consistent with a “hypothetical approach”). While the data analyzed under these two rules is largely overlapping, it provides a clear comparison of the two approaches and allows us to assess the effect that censoring post-symptomatic medication observations has on estimates of placebo group change. We apply a compound symmetric correlation structure with heterogeneous variance with respect to study visit.

We also apply a linear mixed effect model treating time as continuous. Fixed effects in this model include time (in years) since ADNI baseline, age at baseline, APOEε4 status, an indicator for initiation of symptomatic medications at any time during follow-up (0 if never on symptomatic medications, 1 otherwise), years on symptomatic medication (0 until initiation of symptomatic medication), the interaction between time and APOEε4, the interaction between time and the indicator for symptomatic medication use, and the interaction between APOEε4 and years on symptomatic medication. Random effects included subject-specific random intercepts and slopes. We repeat all of the above analyses on the subgroup of participants who are deemed amyloid beta positive (“Aβ+”) at baseline using florbetapir PET cutoff of 1.10 SUVR units, and a Roche Elecsys CSF Aβ1–42 cutoff of 1065 pg/ml. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.218.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive summaries of the ADNI population grouped according to when they were prescribed symptomatic medications: prior to ADNI baseline, during the course of ADNI follow-up, or never. The groups were different at the time of the participants’ first ADNI visit in many respects. The group that initiated symptomatic medications prior to, or during, the course of ADNI were more advanced in terms of the diagnosis of LMCI versus EMCI, cognitive assessments, and hippocampal volume. Those that received symptomatic medications exhibited a greater degree of amyloid pathology; and a greater rate of APOEε4 carriage. Those that never initiated symptomatic medications were younger.

Table 1.

Definitions of key clinical trial terminology.

| Terminology | Definition |

|---|---|

| Estimand | The true target of an estimate for a particular clinical trial objective. It is defined by the subject population, the outcome, the handling of intercurrent events, and the statistical summary measure of effect. Estimates are produced by statistical estimation procedures applied to data and might depend on a variety of assumptions if the estimand of interest is not directly observable, e.g. due to imperfect adherence of subjects to the protocol. |

| Treatment-policy estimand | The effectiveness of an intervention regardless of events that occur after intervention is administered (e.g. compliance to intervention regime or attrition). The intention-to-treat principle (analyzing all available data from all randomized subjects) is applied when the treatment-policy estimand is desired. If all subjects are followed until the end of the trial the treatment-policy estimand can be estimated without assumptions. |

| Intercurrent event | An event which occurs after randomization to an intervention which might interfere with the estimation or interpretation of the effect of the intervention (e.g. initiation of a rescue therapy). |

| Hypothetical estimand | An alternative to the treatment-policy estimand under a particular hypothetical scenario (e.g., the efficacy of an intervention had an intercurrent event, such as initiation of rescue therapy, not occurred). Estimation of hypothetical estimands generally relies on untestable assumptions. |

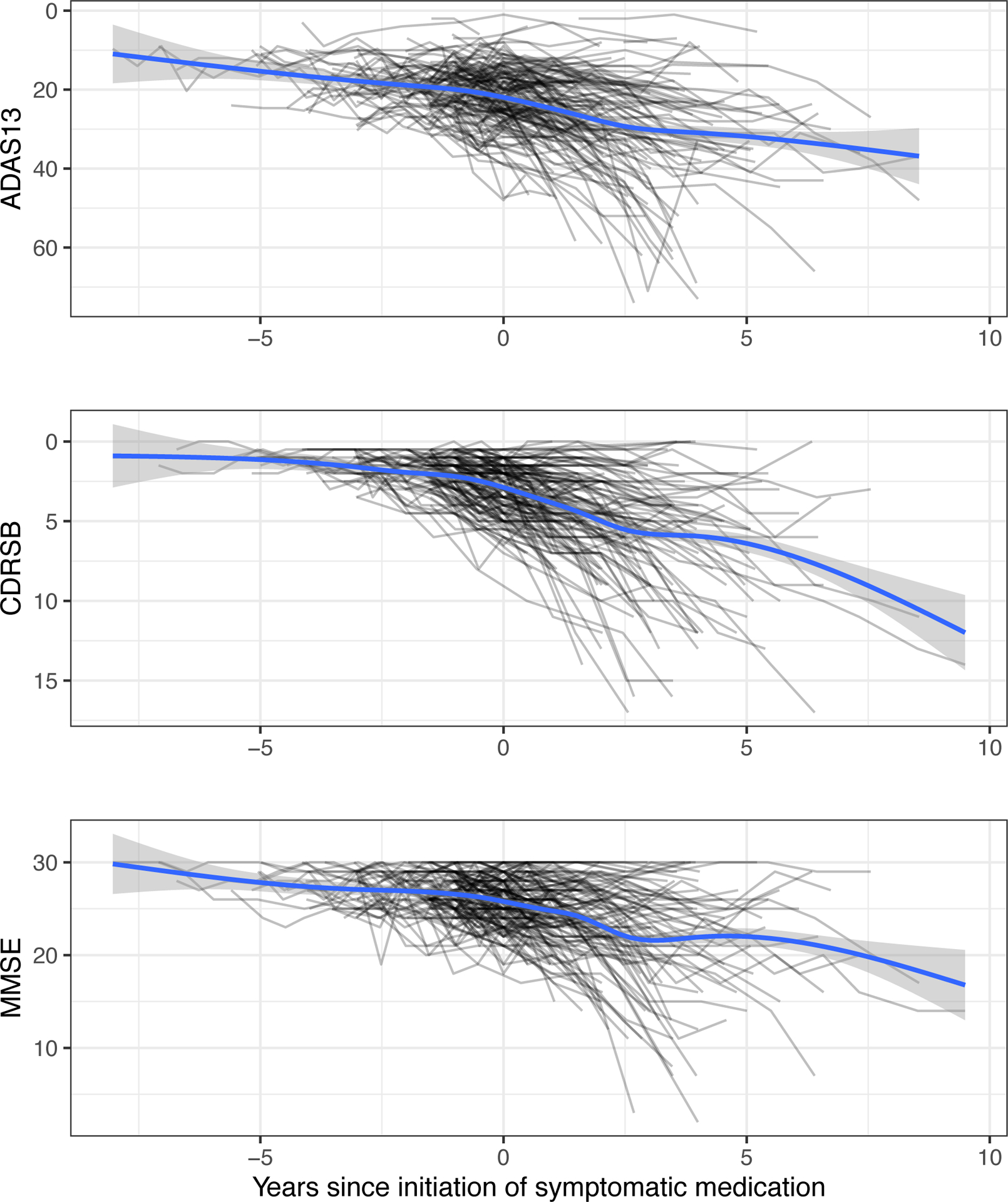

Figure 1 shows spaghetti plots of ADAS, CDR-SB, and MMSE relative to the time of initiation of symptomatic medication (time 0). The average trend shows decline occurring in advance of the initiation of treatment (−2.5 to 0 years), as one might expect. However, this decline trend continues, rather than reverses as one might expect, in the time period after the initiation of symptomatic treatment. It is likely that the trend would show a greater degree of decline had participants not been prescribed symptomatic treatment, but the decline continued on average, nonetheless.

Figure 1.

Spaghetti plots of ADAS13, CDRSB, and MMSE relative to time of initiation of symptomatic medication for ADNI participants who initiated symptomatic medication. The blue trend lines estimated by LOESS do not demonstrate a cognitive improvement soon after time 0, even though a benefit relative to no treatment cannot be ruled out. Shaded regions depict 95% confidence intervals, not accounting for repeated measures.

Abbreviations: ADAS13, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale - 13 item cognitive subscale; CDRSB, Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes; MMSE, Mini Mental State Exam; LOESS, LOcally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing.

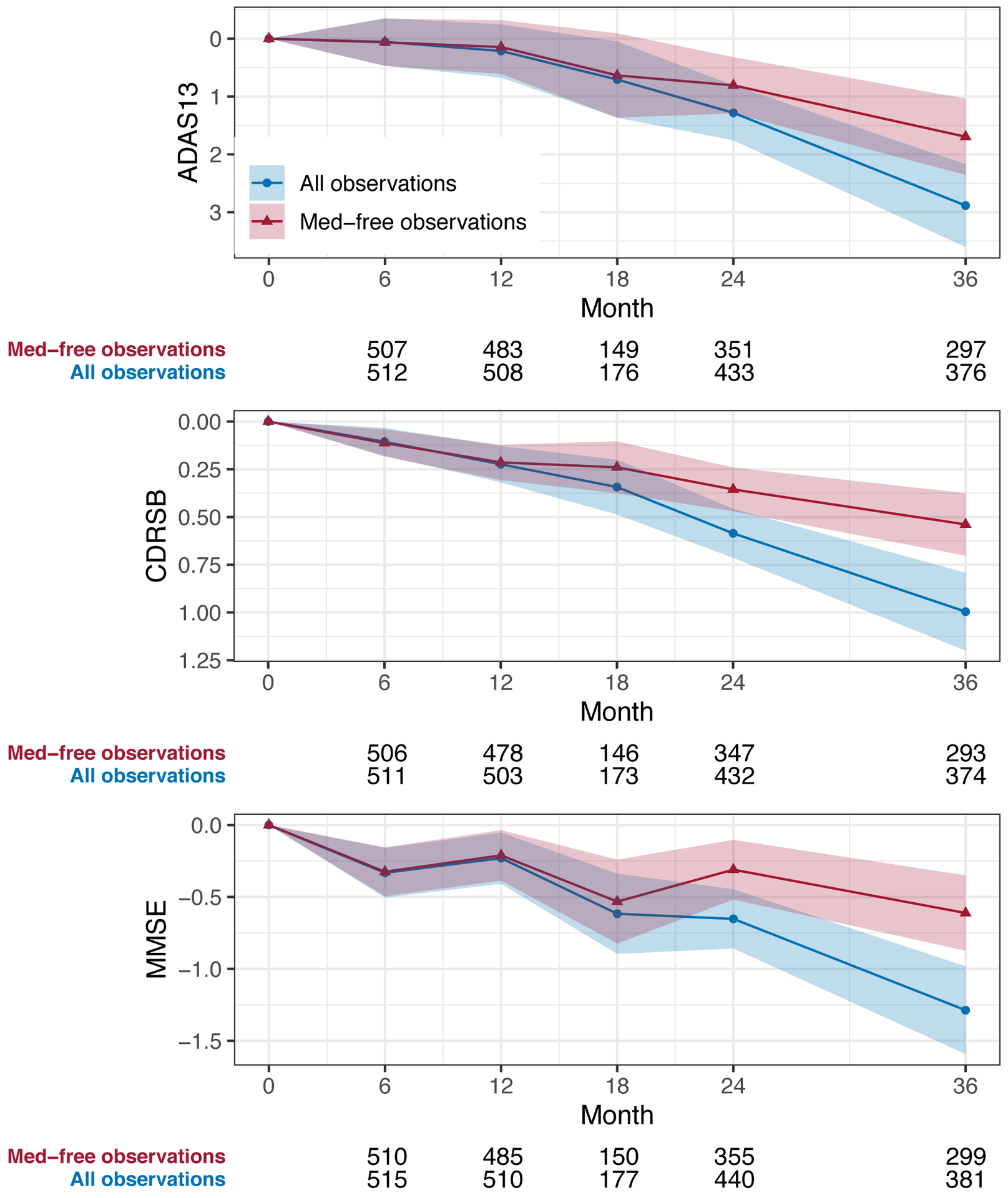

Similarly, Figure 2 demonstrates that MMRM estimates of the mean change from baseline in ADAS, CDR-SB, and MMSE that include post-symptomatic treatment observations (blue circles) are worse than estimates that censor this data and are based on medication naïve observations only (red triangles). This suggests that a placebo group trend estimated under a treatment policy approach would be worse than a placebo group trend estimated under a hypothetical approach. Analyses restricted to the Aβ+ Prodromal population were similar, but with a greater degree of decline under either rule (Supplemental Figure A2).

Figure 2.

Plots of mean change in ADAS13, CDRSB, and MMSE among ADNI MCI participants estimated by including all observations (blue circles) or excluding observations after the initiation of symptomatic medication (red triangles) over the first 36 months of follow-up. Covariates include baseline score, APOEe4 carriage, and age. Shaded regions depict 95% confidence intervals. Numbers below each plot are observation counts at each timepoint.

Abbreviations: ADAS13, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale - 13 item cognitive subscale; CDRSB, Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes; MMSE, Mini Mental State Exam; MMRM, Mixed Model of Repeated Measures.

The linear mixed effect model results were consistent with the MMRM. These models confirmed that those who eventually were prescribed medication, versus not, performed worse at baseline on the ADAS (4.35 points, standard error [SE] 0.586, p<0.001), CDRSB (0.475 points, SE=0.0813, p<0.001), and MMSE (−0.92 points, SE=0.0087, p<0.001); and decline more after initiation of medication on the ADAS (2.41 points per year on medication, SE=0.302, p<0.001), CDRSB (0.642 points per year on medication, SE=0.0704, p<0.001), and MMSE (–0.91 points per year on medication, SE=0.1269, p<0.001).

Discussion

Our goal was to assess the effect of concurrent symptomatic medications, when prescribed by physicians during a clinical trial, on likely placebo group trajectories. Counter to intuition fueled by an optimistic impression of symptomatic effects, placebo group trajectories estimated under a hypothetical approach, censoring post-symptomatic treatment observations, might show less decline in cognitive and functional outcomes than trajectories estimated under a treatment policy approach including observations during newly initiated symptomatic treatment. The implication is that the power to detect experimental treatment effects is likely improved, rather than diminished, by taking a treatment policy approach that aims to collect and analyze data observed after the initiation of symptomatic drugs rather than a hypothetical approach.

Hypothetical estimands are meant to capture the effect of an intervention in absence of intercurrent events. Treatment policy estimands are meant to incorporate other effects than the intervention of interest alone. This research shed lights on the limitation of censoring post-rescue data. While data after intercurrent events is often censored or excluded under a hypothetical estimand, including these observations may result in better power and more appropriate estimates of treatment effect.

Consistent with prior findings11, our analysis suggests that the effects of symptomatic drugs are not as strong as we might hope, and are not able to compensate for the worsening cognition and function that triggered the treatment initiation. The reported results do not contradict the modest benefit symptomatic treatments have demonstrated in randomized clinical trials, particularly in later, more symptomatic stages of AD. However, they underscore the need for more efficacious treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Characteristics of ADNI MCI participants grouped by whether or not the participant initiated a symptomatic medication during the course of follow-up. P-values are from Pearson’s χ2 test or Kruskal-Wallis test.

| N | On symptomatic medication at baseline (N=351) | Initiated symptomatic medication (N=147) | Never Initiated symptomatic medication (N=479) | Combined (N=977) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eMCI at baseline | 977 | 74 (21%) | 41 (28%) | 240 (50%) | 355 (36%) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 977 | 73.19 (7.18) | 74.23 (6.98) | 72.36 (8.12) | 72.94 (7.65) | 0.015 |

| Sex (female) | 977 | 129 (37%) | 58 (39%) | 214 (45%) | 401 (41%) | 0.066 |

| Education (years) | 977 | 15.91 (2.81) | 15.80 (2.82) | 16.03 (2.80) | 15.95 (2.80) | 0.607 |

| Ethnicity | 977 | 0.534 | ||||

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 338 (96%) | 144 (98%) | 457 (95%) | 939 (96%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 12 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 18 (4%) | 33 (3%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (1%) | ||

| Race | 977 | 0.046 | ||||

| Am. Indian/Alaskan | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) | 2 (0%) | ||

| Asian | 5 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 16 (2%) | ||

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) | 2 (0%) | ||

| Black | 5 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 27 (6%) | 35 (4%) | ||

| White | 339 (97%) | 139 (95%) | 430 (90%) | 908 (93%) | ||

| More than one | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 11 (1%) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (0%) | ||

| Marital status | 977 | 0.008 | ||||

| Divorced | 19 (5%) | 14 (10%) | 57 (12%) | 90 (9%) | ||

| Married | 294 (84%) | 116 (79%) | 345 (72%) | 755 (77%) | ||

| Never married | 7 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 18 (4%) | 26 (3%) | ||

| Widowed | 30 (9%) | 15 (10%) | 55 (11%) | 100 (10%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| APOEε4 alleles | 603 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 136 (41%) | 62 (42%) | 272 (60%) | 470 (50%) | ||

| 1 | 147 (44%) | 67 (46%) | 151 (33%) | 365 (39%) | ||

| 2 | 52 (16%) | 18 (12%) | 32 (7%) | 102 (11%) | ||

| CSF Aβ1–42 (pg/ml) | 619 | 796 (372) | 799 (375) | 1145 (431) | 961 (437) | <0.001 |

| Florbetapir PET (SUVR) | 488 | 1.313 (0.236) | 1.295 (0.215) | 1.150 (0.203) | 1.215 (0.227) | <0.001 |

| Amyloid positive | 743 | 154 (59%) | 75 (64%) | 204 (56%) | 433 (58%) | 0.300 |

| CDR Sum of Boxes | 977 | 1.822 (0.944) | 1.561 (0.817) | 1.261 (0.768) | 1.508 (0.880) | <0.001 |

| ADAS-Cog 13 | 970 | 19.60 (6.47) | 18.93 (6.19) | 14.11 (5.98) | 16.80 (6.73) | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 977 | 27.15 (1.84) | 27.33 (1.80) | 28.03 (1.71) | 27.61 (1.82) | <0.001 |

| Hippocampus (/ICVx1,000) | 744 | 4.179 (0.736) | 4.164 (0.746) | 4.738 (0.772) | 4.444 (0.805) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up (years) | 977 | 3.42 (2.68) | 4.85 (2.15) | 3.45 (2.94) | 3.65 (2.78) | <0.001 |

| Exposure to symptomatic medication (years) | 977 | - | 2.913 (1.803) | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: eMCI, Early Mild Cognitive Impairment; PET, positron emission tomography; SUVR, standard uptake value ratio; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive subscale; MMSE, Mini Mental State Exam; ICV, Intracranial Volume

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging grant R01-AG049750.

References

- 1.Committee for Human Medicinal Products. ICH E9 (R1) addendum on estimands and sensitivity analysis in clinical trials to the guideline on statistical principles for clinical trials, Step 2b. In:2017.

- 2.Ostrowitzki S, Lasser RA, Dorflinger E, et al. A phase III randomized trial of gantenerumab in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):379–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gauthier S, Molinuevo JL. Benefits of combined cholinesterase inhibitor and memantine treatment in moderate-severe Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(3):326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atri A, Hendrix SB, Pejovic V, et al. Cumulative, additive benefits of memantine-donepezil combination over component monotherapies in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s dementia: a pooled area under the curve analysis. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salloway S, Ferris S, Kluger A, et al. Efficacy of donepezil in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2004;63(4):651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352(23):2379–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Medicines Agency. Draft guideline on the clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia. In: (CHMP) CfMPfHU, ed. Vol EMA/CHMP/539931/2014. London, United KIngdom: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74(3):201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tariot PN, Solomon P, Morris J, et al. A 5-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of galantamine in AD. Neurology. 2000;54(12):2269–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider LS, Insel PS, Weiner MW. Treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine of patients in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Archives of neurology. 2011;68(1):58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74(3):201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohs RC, Knopman D, Petersen RC, et al. Development of cognitive instruments for use in clinical trials of antidementia drugs: additions to the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale that broaden its scope. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 1997;11 Suppl 2:S13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;141(11):1356–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallinckrodt CH, Clark WS, David SR. Accounting for dropout bias using mixed-effects models. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics. 2001;11(1–2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program]. Version 3.5.2. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.