Abstract

Background

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) remains undertreated despite multiple potentially curative options. Both radical cystectomy (RC) with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy and trimodal therapy (TMT), including transurethral resection of bladder tumor followed by chemoradiotherapy, are standard treatments.

Objective

To evaluate real-world clinical outcomes of RC with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (RC-NAC), RC without NAC, TMT with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline–preferred radiosensitizing chemotherapy including cisplatin or mitomycin-C and 5-fluorouracil (pTMT), and TMT with nonpreferred chemotherapy (npTMT).

Design, setting, and participants

US veterans with nonmetastatic MIBC (T2-4aN0-3M0) were studied.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

Overall mortality (OM) was evaluated with multivariable Cox proportional hazard model. Bladder cancer-specific mortality (BCSM) was evaluated with multivariable Fine-Gray regression. Salvage cystectomy rates were obtained by chart review.

Results and limitations

Overall 2306 patients were included: 1472 (64%) with RC without NAC, 506 (22%) with RC-NAC, 163 (7%) with pTMT, and 165 (7%) with npTMT. On multivariable analysis, pTMT was associated with similar OM (hazard ratio [HR] 1.19; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.94–1.50; p = 0.15) and BCSM (HR 1.34; 95% CI 0.99–1.83; p = 0.06) to RC-NAC; npTMT was associated with worse OM (HR 1.30; 95% CI 1.04–1.61; p = 0.02) and BCSM (HR 1.45; 95% CI 1.09–1.94; p = 0.01). RC without NAC was associated with similar OM (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.95–1.24; p = 0.24) and BCSM (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.86–1.21; p = 0.79). When stratified by age, among patients ≥65 yr of age, treatment with pTMT was associated with similar OM (HR 1.14; 95% CI 0.87–1.50; p = 0.35) and BCSM (HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.76–1.62; p = 0.60). Among patients <65 yr of age, pTMT was associated with worse OM (HR 1.82; 95% CI 1.14–2.91; p = 0.01) and BCSM (HR 2.51; 95% CI 1.52–4.13; p < 0.01). The 5-yr cumulative incidence of salvage cystectomy in the TMT group was 3.6%.

Conclusions

In MIBC, patients receiving pTMT have comparable survival in RC-NAC patients ≥65 yr and inferior survival in RC-NAC patients <65 yr. Salvage cystectomy rates were low.

Patient summary

Management of muscle-invasive bladder cancer is a multidisciplinary effort requiring thoughtful discussions with patients about treatment options, including trimodal therapy, which is an effective treatment option.

Keywords: Muscle-invasive bladder cancer, Radical cystectomy, Trimodal therapy, Bladder preservation, Chemoradiotherapy, Treatment

Take Home Message

In muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), patients receiving trimodal therapy with preferred chemotherapy have similar survival to those receiving radical cystectomy with low salvage cystectomy rates. Management of MIBC is a multidisciplinary effort requiring thoughtful discussions with patients about treatment options.

1. Introduction

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is common and deadly, but potentially curable if treated promptly. Evidence-supported guidelines recommend two broad categories of primary definitive treatment for MIBC: radical cystectomy (RC) and trimodal therapy (TMT). RC is an effective treatment option for MIBC, but comes with significant perioperative risk, along with quality of life concerns [1], [2], [3], [4]. TMT, which involves maximal transurethral resection of the tumor followed by concurrent radiosensitizing chemotherapy and radiotherapy, is a treatment option for those refusing or deemed not candidates for cystectomy [5].

Despite recommendations for either RC or TMT, close to 50% of patients with MIBC in the USA receive no definitive therapy [6], [7], [8]. This discrepancy is possibly a result of the advanced age and comorbid illnesses in many patients with bladder cancer, the perception of the high risk of cystectomy, and a lack of information on the value of TMT. As such, there is a critical need for more research on the efficacy of noncystectomy options such as TMT to expand the utilization of curative therapy and to enable informed decision-making for all patients. There is a growing body of observational national registry data comparing TMT with RC [9], [10]. However, due to limitations of the data, the existing retrospective literature often cannot account for important confounders such as type of chemotherapy or baseline renal function [11], [12]. In some analyses, palliative radiotherapy and definitive radiotherapy are grouped together.

The Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System is a system that reduces financial barriers to medical care resulting in relatively equal access. The VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) is a comprehensive informatics platform with access to patient-level electronic health record information and administrative data for all veterans within the Veterans Health Administration. This detailed patient information allows for the analysis of important confounders not addressed in previous studies. The objective of our analysis was to describe overall, bladder cancer, and noncancer mortality in patients with MIBC treated with RC and TMT, using a detailed national cancer registry linked to patient electronic medical records.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Data source

We extracted data from VINCI, which incorporates tumor registry data gathered at individual VA medical centers according to the protocols issued from the American College of Surgeons. We linked VINCI with the National Death Index and used the VINCI registry data to obtain cause-specific mortality information (ICD-10 code C67 for BC), and with the American Community Survey to obtain zip-code–level income and education. This study was approved by the San Diego VA Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Study population

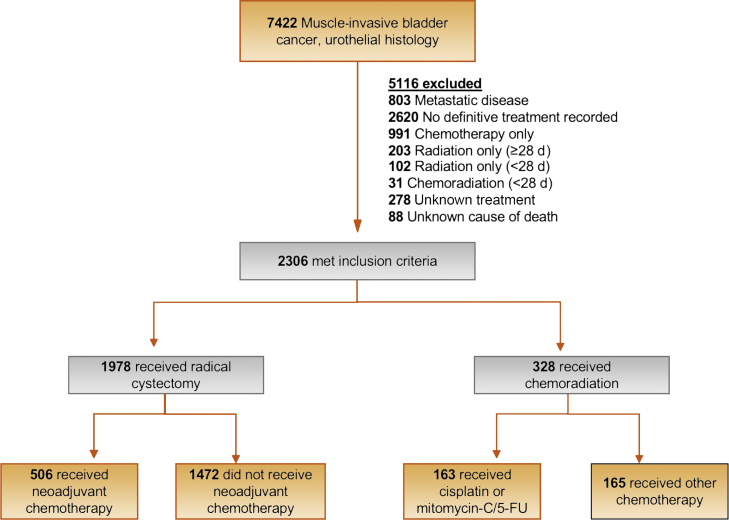

We identified 2306 patients with localized muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma (T2-T4a, N1-3, M0) without prior malignancies from 114 VA centers diagnosed between 2000 and 2017, who received RC or TMT (Fig. 1). Definitive radiation dose consists of 55 Gy over 4 wk or 64 Gy over 6.5 wk [1]. In VINCI, radiation fractionation information is sometimes missing since many patients receive radiation outside the VA, but the radiation start and end dates are present. To this end, we defined definitive radiation a priori as radiation lasting at least 28 d from radiation start date to end date. Concurrent chemotherapy was defined as chemotherapy prescribed within 14 d of the radiation start date.

Fig. 1.

Patient selection process. 5-FU = 5-fluorouracil.

We manually reviewed charts of all TMT patients with at least 28 d between radiation start and end dates to ascertain reasons why they received TMT (Supplementary Table 1) and radiation dosage received (if available; Supplementary Table 2), specific concurrent chemotherapeutic agents prescribed, and documentation of salvage cystectomy. We grouped patients receiving National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)-“preferred” regimens (cisplatin alone, cisplatin and fluorouracil, cisplatin and paclitaxel, mitomycin, and fluorouracil) as pTMT [1]. Any other concurrent chemotherapy was considered nonpreferred, that is, npTMT.

We extracted the following patient-level variables: age, year of diagnosis, marital status, race, tobacco history, body mass index (BMI), zip-code income education, and creatinine. We used previously described methods to determine Charlson comorbidity index score from comorbid conditions that patients had in the year prior to diagnosis. All patients were followed until death or the last follow-up with a VA provider with the latest possible follow-up on December 31, 2017, which was the last day of follow-up in the registry at the time of analysis.

2.3. Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome of our study was overall mortality (OM), defined as the date of diagnosis to date of death from any cause. The secondary outcomes were bladder cancer–specific mortality (BCSM) and non–cancer-specific mortality (NCSM), defined as the date of diagnosis to the date of death from bladder cancer and from unrelated causes, respectively, and the rate of salvage cystectomy. Ascertainment of salvage cystectomy is explained in the Supplementary material. Patients alive at the date of last follow-up were censored on that date.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Unadjusted analysis survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared statistically using the log rank test. Multivariable analysis for OM was performed with a Cox regression model including age, race, BMI, creatinine clearance, Charlson comorbidity score, clinical T stage, and clinical N stage. Carcinoma in situ and hydronephrosis were not included since these were not collected in the structured dataset. Since previous studies have noted an interaction between treatment regimen and age, we added an interaction term and also evaluated survival outcomes in patients aged 65 yr or older in a sensitivity analysis [13]. We modeled BCSM and NCSM using competing events of cancer versus noncancer death with a Fine-Gray regression and reported hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used the same covariates from the multivariable Cox regression analysis in the Fine-Gray regression analyses. Missing data were imputed using the Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) R package [14]. The base analyses were conducted using imputed data, and a complete case analysis was also conducted as a sensitivity analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), with two-sided p values of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics and treatment

Overall 2306 patients with clinically localized MIBC in 114 sites were included in our cohort, of whom 1978 (86%) had RC and 328 (14%) had TMT. Of the TMT patients, 163 (50%) received NCCN guidelines-preferred chemotherapy classified as pTMT (cisplatin group 80% and mitomycin/5-fluorouracil 20%) while 165 (50%) received npTMT (carboplatin 62%, paclitaxel 16%, gemcitabine 10%, and other 12%). Of the 1978 patients with RC, 506 (26%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). Between 2000 and 2017, the median number of patients treated with RC per site was 13 (95% CI 1–60) and the median number of patients treated with TMT per site was 3 (95% CI 1–10).

Compared with patients with TMT, those receiving RC were nearly 10 yr younger (median age: RC 66, TMT 75; p < 0.01), more likely to have a creatinine clearance of >50 (RC 76%, TMT 61%; p < 0.01), and more likely to have a Charlson comorbidity index of 0 (RC 61%, TMT 52%; p < 0.01). Compared with patients who had npTMT, patients with pTMT were younger (median age: pTMT 73, npTMT 78; p < 0.01), more likely to have a creatinine clearance of >50 (pTMT 68%, npTMT 53%; p < 0.01), and more likely to have a Charlson comorbidity index of 0 (pTMT 58%, npTMT 45%; p = 0.03). Reasons why patients received TMT included not being a surgical candidate due to comorbidities (pTMT 50%, npTMT 65%), being a surgical candidate but refusing cystectomy (pTMT 42%, npTMT 22%), and palliation (pTMT 7%, npTMT 12%; Supplementary Table 1). Radiation dosages for patients receiving TMT are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Trimodal therapy |

Radical cystectomy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred chemotherapy | Nonpreferred chemotherapy | No neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| All patients, no. | 163 | 165 | 1472 | 506 | |

| Age, median (95% CI) | 73 (57–89) | 78 (60–89) | 67 (52–81) | 65 (52–81) | |

| Age groups, no. (%) | |||||

| <55 | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 87 (6) | 25 (5) | |

| 55–64 | 31 (19) | 22 (13) | 503 (34) | 215 (42) | |

| 65–74 | 55 (34) | 37 (22) | 529 (36) | 204 (40) | |

| 75–84 | 57 (35) | 81 (49) | 315 (21) | 61 (12) | |

| ≥85 | 17 (10) | 25 (15) | 38 (3) | 1 (0) | |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||||

| Male | 160 (98) | 165 (100) | 1465 (99) | 504 (99) | |

| Female | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 7 (0) | 2 (0) | |

| Race, no. (%) | |||||

| White | 151 (93) | 147 (89) | 1309 (89) | 442 (87) | |

| Black | 10 (6) | 12 (7) | 118 (8) | 47 (9) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 15 (1) | 6 (1) | |

| Missing | 2 (1) | 5 (3) | 30 (2) | 11 (2) | |

| Married, no. (%) | 83 (50) | 93 (55) | 705 (48) | 242 (48) | |

| Year of diagnosis, no. (%) | |||||

| 2000–2005 | 28 (17) | 27 (16) | 569 (39) | 55 (11) | |

| 2006–2011 | 63 (39) | 66 (40) | 651 (44) | 241 (48) | |

| 2012–2017 | 72 (44) | 72 (44) | 252 (17) | 210 (42) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, no. (%) | |||||

| 0 | 95 (58) | 74 (45) | 873 (59) | 333 (66) | |

| 1 | 45 (28) | 57 (35) | 270 (18) | 87 (17) | |

| ≥2 | 16 (10) | 23 (14) | 82 (6) | 14 (3) | |

| Missing | 7 (4) | 11 (7) | 247 (17) | 72 (14) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (95% CI) | 26 (16–42) | 26 (16–42) | 25 (16–39) | 26 (16–39) | |

| Creatinine, median (95% CI) | 1.1 (0.7–2.6) | 1.3 (0.70–3.9) | 1.1 (0.6–34.1 | 1.1 (0.6–2.6) | |

| Creatinine, no. (%) | |||||

| <1.5 | 127 (76) | 90 (61) | 1094 (74) | 391 (77) | |

| ≥1.5 | 30 (20) | 53 (36) | 322 (22) | 97 (19) | |

| Missing | 6 (4) | 5 (3) | 56 (4) | 18 (4) | |

| Creatinine clearance, median (95% CI) | 61 (25–388) | 51 (16–170) | 70 (18–281) | 74 (30 – 208) | |

| Creatinine clearance a, no. (%) | |||||

| ≥50 | 113 (68) | 87 (53) | 1068 (73) | 402 (79) | |

| <50 | 44 (28) | 72 (44) | 348 (24) | 86 (17) | |

| Missing | 6 (4) | 6 (4) | 56 (4) | 18 (4) | |

| Current tobacco use, no. (%) | |||||

| Yes | 57 (35) | 50 (30) | 729 (50) | 244 (48) | |

| No | 106 (65) | 115 (70) | 743 (50) | 262 (52) | |

| Zip-code–level income (dollars in thousands), median (95% CI) | 46.2 (26.8–87.6) | 49.6 (26.7–95.5) | 46.5 (26.0–102.4) | 48.2 (25.9–96.5) | |

| Clinical T stage, no. (%) | |||||

| T2 | 138 (85) | 141 (85) | 1175 (78) | 389 (77) | |

| T3 | 12 (7) | 17 (10) | 190 (13) | 82 (16) | |

| T4A | 13 (8) | 7 (4) | 142 (9) | 35 (7) | |

| Clinical N stage, no. (%) | |||||

| N0 | 153 (94) | 152 (92) | 1319 (90) | 447 (88) | |

| N1 | 4 (2) | 5 (3) | 48 (3) | 24 (5) | |

| N2 | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | 53 (4) | 25 (5) | |

| N3 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 4 (0) | 3 (0) | |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 48 (3) | 7 (1) | |

BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval.

Calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault formula.

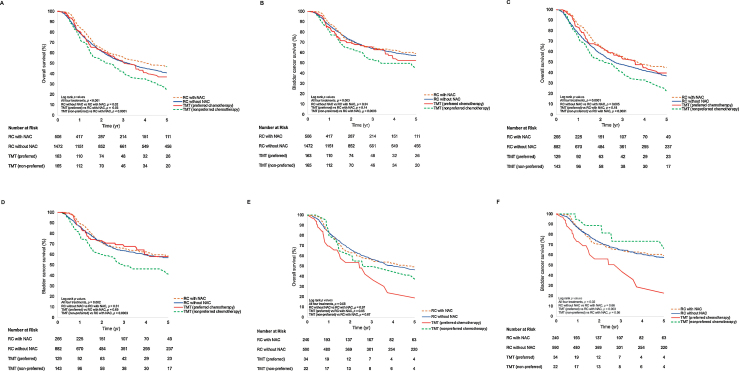

3.2. Survival

The median follow-up time for patients alive at the last follow-up was 4.7 yr (95% CI 0.5–15 yr). There were 1449 deaths, of which 872 (60%) were from bladder cancer. The 5-yr cumulative incidence of death from bladder cancer and that from any cause were 39% (95% CI 37–41%) and 59% (95% CI 57–61%), respectively. The median overall survival (OS) times for RC with NAC (RC-NAC), RC without NAC, pTMT, and npTMT were 4.1 (95% CI 3.1–5.5), 3.2 (95% CI 2.8–3.6), 3.1 (95% CI 2.3–3.9), and 2.4 (95% CI 1.6–3.0) yr, respectively. OS data by treatment modality at time points 1, 3, and 5 yr are included in Table 2. Survival curves for OS and bladder cancer–specific survival are shown in Figure 2. Non–cancer-specific survival curves are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Table 2.

Survival results at different time points for treatment groups

| Cohort | Treatment | N | 1-yr overall survival (95% CI) | 3-yr overall survival (95% CI) | 5-yr overall survival (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | RC with NAC | 506 | 85% (81–87%) | 56% (51–60%) | 46% (41–51%) |

| RC without NAC | 1472 | 79% (77–81%) | 51% (49–54%) | 41% (38–43%) | |

| TMT with preferred chemotherapy | 163 | 81% (73–86%) | 51% (42–59%) | 37% (28–46%) | |

| TMT with nonpreferred chemotherapy | 165 | 75% (67–81%) | 41% (32–49%) | 24% (16–32%) | |

| Patient age ≥65 yr | RC with NAC | 266 | 86% (81–89%) | 55% (48–61%) | 44% (37–50%) |

| RC without NAC | 882 | 77% (74–80%) | 47% (44–51%) | 37% (34–40%) | |

| TMT with preferred chemotherapy | 129 | 83% (74–88%) | 53% (43–62%) | 40% (29–50%) | |

| TMT with nonpreferred chemotherapy | 143 | 73% (65–80%) | 39% (30–48%) | 22% (14–30%) | |

| Patient age <65 yr | RC with NAC | 240 | 83% (78–87%) | 56% (49–62%) | 49% (41–55%) |

| RC without NAC | 590 | 83% (80–86%) | 57% (52–61%) | 46% (42–51%) | |

| TMT with preferred chemotherapy | 34 | 70% (50–83%) | 37% (17–56%) | 18% (5–38%) | |

| TMT with nonpreferred chemotherapy | 22 | 80% (55–92%) | 50% (27–69%) | 31% (10–55%) |

CI = confidence interval; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC = radical cystectomy; TMT = trimodal therapy.

Preferred chemotherapy includes cisplatin or mitomycin-C/5-fluorouracil.

Fig. 2.

Overall and bladder cancer–specific survival curves by treatment for (A and B) all ages, (C and D) ages ≥ 65 yr, and (E and F) ages <65 yr. Preferred chemotherapy includes cisplatin or mitomycin-C/5-fluorouracil. NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC = radical cystectomy; TMT = trimodal therapy.

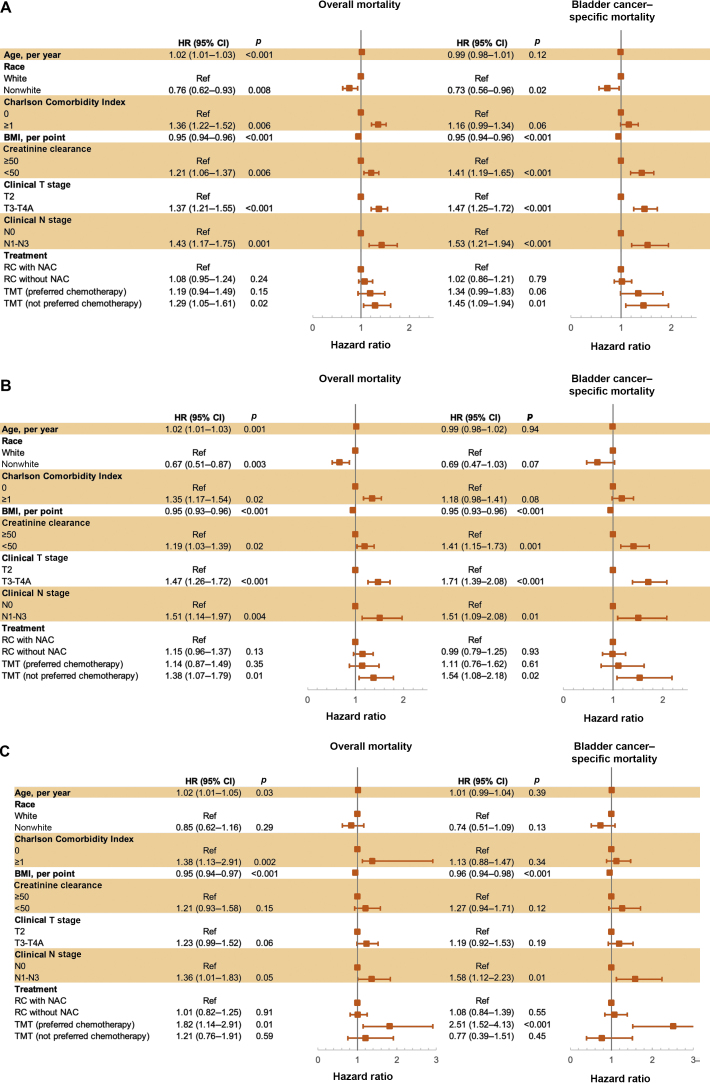

A multivariable analysis that adjusted for clinical tumor and nodal staging, age, race, BMI, Charlson comorbidity index, and creatinine clearance did not reveal significant differences between RC-NAC and pTMT in OM (HR 1.19; 95% CI 0.94–1.50; p = 0.15), BCSM (HR 1.34; 95% CI 0.99–1.83; p = 0.06), or NCSM (HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.64–1.46; p = 0.86). The multivariable analysis revealed that compared with RC-NAC, npTMT was associated with inferior OM (HR 1.30; 95% CI 1.05–1.61; p = 0.02) and BCSM (HR 1.45; 95% CI 1.09–1.94; p = 0.01), but similar NCSM (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.73–1.59; p = 0.71). On multivariable analysis, compared with RC-NAC, RC without NAC was associated with similar OM (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.95–1.24; p = 0.24) and BCSM (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.86–1.21; p = 0.79), but inferior NCSM (HR 1.37; 95% CI 1.09–1.73; p = 0.01). Detailed results for the multivariable analyses for OM and BCSM are shown in Figure 3. Of note, on univariable analysis, year of diagnosis was not statistically associated with OM (p = 0.35) or BCSM (p = 0.42). Interaction terms indicated that a beneficial treatment effect of pTMT on OM compared with RC-NAC increased with age, per year (HR 0.97; 95% CI 0.94–0.99; p = 0.03), while no statistically significant interaction was observed with age and RC without NAC (p = 0.61) or npTMT (p = 0.38). There were no statistically significant interactions between age and any treatment on BCSM (p = 0.55) or NCSM (p = 0.08).

Fig. 3.

Association of patient characteristics with overall and bladder cancer–specific mortality in multivariable models for patients of (A) all ages, (B) ages ≥65 yr, and (C) ages <65 yr. Preferred chemotherapy includes cisplatin or mitomycin-C/5-fluorouracil. BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC = radical cystectomy; Ref = reference; TMT = trimodal therapy.

In the multivariable analysis for the entire cohort, low creatinine clearance (OM HR 1.21; p = 0.01; BCSM HR 1.40; p < 0.001), more advanced tumor stage (OM HR 1.37; p < 0.001; BCSM HR 1.47; p < 0.001), and more advanced nodal stage (OM HR 1.43; p = 0.001; BCSM HR 1.53; p < 0.001) were associated with inferior survival. Nonwhite race (OM HR 0.76; p = 0.008; BCSM HR 0.73; p = 0.02) and increased BMI (OM HR 0.95; p < 0.0001; BCSM HR 0.95; p < 0.001) were associated with improved survival.

In a sensitivity analysis including patients 65 yr and older (RC without NAC 60%, RC-NAC 62%, pTMT 79%, and npTMT 87%), on multivariable analysis, pTMT yielded similar survival outcomes to RC-NAC for OM (HR 1.14, 95% CI 0.87–1.50; p = 0.35), BCSM (HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.76–1.62; p = 0.60), and NCSM (HR 1.18; 95% CI 0.73–1.90; p = 0.51); npTMT in patients older than 65 yr was associated with worse outcomes for OM (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.07–1.79; p = 0.01) and BCSM (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.08–2.18; p = 0.02), but not NCSM (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.69–1.71; p = 0.73; Table 3). Multivariable regression results for other age groups are included in Supplementary Table 3. In patients younger than 65 yr, pTMT was associated with inferior OM (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.08–2.18; p = 0.02) and BCSM (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.08–2.18; p = 0.02) compared to RC-NAC. Multivariable regression results for clinical N0 patients only are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 3.

Summary of multivariable regression results

| Outcome | TMT, preferred chemotherapy Reference: RC-NAC |

TMT, nonpreferred chemotherapy Reference: RC-NAC |

RC without NAC Reference: RC-NAC |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| All ages | |||||||||

| Overall mortality | 1.19 | 0.94–1.50 | 0.15 | 1.30 | 1.04–1.61 | 0.02 | 1.08 | 0.95–1.24 | 0.24 |

| Bladder cancer–specific mortality | 1.34 | 0.99–1.83 | 0.06 | 1.45 | 1.09–1.94 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 0.86–1.21 | 0.79 |

| Non–cancer-specific mortality | 0.96 | 0.64–1.46 | 0.86 | 1.08 | 0.73–1.59 | 0.71 | 1.37 | 1.09–1.73 | 0.008 |

| Age ≥65 yr | |||||||||

| Overall mortality | 1.14 | 0.87–1.50 | 0.35 | 1.38 | 1.07–1.79 | 0.01 | 1.15 | 0.96–1.37 | 0.13 |

| Bladder cancer–specific mortality | 1.11 | 0.76–1.62 | 0.60 | 1.54 | 1.08–2.18 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.25 | 0.93 |

| Non–cancer-specific mortality | 1.18 | 0.73–1.90 | 0.51 | 1.08 | 0.69–1.71 | 0.73 | 1.58 | 1.16–2.15 | 0.004 |

| Age <65 yr | |||||||||

| Overall mortality | 1.82 | 1.14–2.91 | 0.01 | 1.20 | 0.76–1.90 | 0.44 | 1.01 | 0.82–1.25 | 0.90 |

| Bladder cancer–specific mortality | 2.51 | 1.52–4.13 | <0.01 | 0.77 | 0.40–1.50 | 0.45 | 1.08 | 0.84–1.39 | 0.55 |

| Non–cancer-specific mortality | 0.39 | 0.09–1.65 | 0.20 | 2.48 | 1.08–5.69 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 0.75–1.56 | 0.66 |

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC = radical cystectomy; RC-NAC = RC with NAC; TMT = trimodal therapy.

Results of multivariable Cox regression analysis for overall mortality, and Fine-Gray regression for bladder cancer–specific mortality and non–cancer-specific mortality. Multivariable analyses controlled for age, race, comorbidities, body mass index, creatinine clearance, tumor stage, and nodal stage.

Of 2306 patients, 1646 (71%) had complete data, and multivariable results for these complete cases are presented in Supplementary Table 5, with results generally consistent with those of imputed cohort.

3.3. Salvage cystectomy

Twelve (3.7%) patients in the TMT group received a salvage cystectomy. The 1- and 5-yr cumulative incidences of salvage cystectomy were 1.6% (95% CI 0.6–3.6%) and 3.6% (95% CI 1.8–6.4%), respectively. There were no differences in salvage rates between pTMT and npTMT (p = 0.65).

4. Discussion

In this large national cohort of patients with MIBC, we aimed to describe survival outcomes for definitive treatments of MIBC. We found similar survival outcomes following RC or TMT with NCCN-preferred chemotherapy regimens, but poorer outcomes after TMT with nonpreferred chemotherapy regimens. When stratified by age, among patients 65 yr or older, those receiving TMT with a preferred chemotherapy (N = 129, 79%) continued to have similar outcomes to those receiving RC-NAC (N = 266, 53%). Among patients younger than 65 yr, TMT with preferred chemotherapy (N = 34, 21%) was associated with inferior survival to RC-NAC (N = 240, 47%). The beneficial effect of TMT with preferred chemotherapy compared with RC-NAC increased with age. As such, patients who refuse cystectomy, or those who are considered ineligible or at a high risk for cystectomy should be offered TMT with preferred chemotherapy, particularly for those 65 yr or older.

The strengths of our study include drawing from 114 VA sites representing diverse practice patterns across the USA. Furthermore, because VINCI includes granular, patient-level electronic health record information, we were able to consider important covariates such as creatinine clearance, smoking status, BMI, and type of radiosensitizing chemotherapy received, and we could also assess cancer-specific survival. In our study, we observed that across our entire cohort, worse creatinine clearance, more advanced tumor stage, and more advanced nodal stage were associated with worse OM and BCSM, while higher BMI and nonwhite race/ethnicity—contrary to national trends—were associated with decreased mortality regardless of treatment modality. This is consistent with other evidence that racial disparities in health outcomes are diminished within the VA system, although the specific reasons why nonwhite veterans with MIBC treated with RC or TMT have improved survival warrants further study [15], [16].

Observational studies using national registry data have previously compared outcomes between RC and TMT in MIBC with mixed results. A recent study by Seisen et al [9] examined data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB), and showed that RC and TMT yielded similar outcomes in the first 25 mo of diagnosis in part because of the perioperative mortality of RC but worse outcomes thereafter. However, the NCDB cannot account for important confounders such as type of chemotherapeutic agent, BMI, or creatinine clearance. Another study by Williams et al [10] reviewed Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data and showed that patients aged 65 yr and older receiving TMT had worse OS and cancer-specific survival than patients receiving RC. Notably, in the SEER study, nearly half of the patients in the TMT group received <18 fractions of radiation treatment. This falls outside the expected dose range given in definitive treatment (typically 20–33 fractions). It is possible that these patients began definitive TMT but had to terminate radiation prematurely due to complications, but TMT is typically well tolerated. Data from the BC2001 trial showed that 95% of patients tolerated definitive dosages of radiation [5]. It may be the case that a substantial portion of TMT patients in the SEER study who received fewer fractions were receiving palliative rather than definitive treatment. A study by Kulkarni et al [17] that included cisplatin-based TMT with definitive dosages showed results similar to ours, albeit with a smaller cohort from a single institution. Systematic reviews have shown that the published studies comparing TMT and RC are observational and at a high risk of bias [18], [19]. The mixed picture presented by these nonrandomized studies cannot be the basis for an assessment of superiority of treatment modalities, but rather supports a balanced discussion with patients of two treatment approaches with comparable outcomes in appropriately selected patients.

Previous studies have shown that rates of salvage cystectomy in patients with TMT range from 10.7% to 14.7% [5], [20]. Interestingly, in our study, we observed that only 3.6% of TMT patients received a salvage cystectomy. This lower rate in the VA may bias our data toward an under-representation of survival potential for patients who have received TMT and develop recurrent disease. However, it may reflect inherent selection bias more accurately, where patients selected for TMT were not candidates for or refused cystectomy. Furthermore, it may also reflect a relatively short follow-up time. With longer follow-up, it is possible that we would observe more salvage cystectomies. It is plausible that patients fit for cystectomy but choosing TMT may have improved outcomes with increased salvage cystectomy rates.

It is important to note the relatively low number of patients with MIBC treated at each VA health site over the 18-yr period (RC median 13, TMT median 3). Outcomes may differ at centers based on volume. Notably, among patients with RC, addition of NAC was not associated with decreased mortality on multivariable analysis, contrary to a recent meta-analysis showing an 18% reduced risk of OM (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71–0.95; p < 0.01) [21]. The differing results may reflect the lower case volumes observed per site in the VA, as many previous studies are from high-volume academic centers.

Our study has limitations based on its retrospective nature and patient population. Although bladder cancer is more prevalent in men than in women, due to patterns of enlistment in US armed forces, our cohort is almost entirely male. Further, in assessing whether patients had received a definitive course of radiotherapy, we relied on the duration of treatment—at least 4 wk—rather than on exact dosage and fractions. Given the utility of TMT as a palliative treatment for MIBC patients, lack of radiation dose information makes it difficult to distinguish definitive from palliative therapy. However, misclassification of definitive radiation dosage would only bias our results away from equivalence of the two treatment modalities. Furthermore, we could not assess the extent of the transurethral resection of bladder tumor prior to TMT. Similarly, our study does not assess the size of tumor, presence or extent of concurrent carcinoma in situ, or hydronephrosis, all of which may have impacted outcomes and decisions to pursue a specific treatment modality. Our study also shares some limitations with previous analyses of RC and TMT for MIBC [9], [13], [22]. We could not ascertain quality-of-life information. Similar to earlier studies, this study does not consider variability in perioperative chemotherapy regimens among RC patients. Interestingly, more patients with RC received NAC in our VA cohort (21%) than in the SEER cohort (14%), which may reflect different practice patterns and time periods of cohorts [10]. Another limitation is that veterans older than 65 yr can qualify for Medicare and may have treatment outside the VA. Therefore, the average age of the study cohort may be younger than that of the general population. Furthermore, patients treated in the VA health system may not necessarily reflect the general population. Finally, our study, similar to others presenting outcomes in RC and bladder-sparing definitive therapy, is retrospective and nonrandomized. It is therefore similarly vulnerable to the selection bias resulting from a historic preference for RC in the youngest and fittest patients. This residual selection bias is expected to favor RC over TMT. Comparable outcomes for TMT with preferred chemotherapy in the presence of these selection biases is further evidence of the effectiveness of TMT.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrate that for patients with MIBC, TMT using an NCCN-preferred chemotherapy is associated with similar outcomes to cystectomy, particularly for patients age 65 yr and older, whereas TMT in patients younger than 65 yr or in combination with a chemotherapy regimen not preferred by the NCCN is associated with poorer survival. Stronger conclusions regarding comparisons of TMT and RC can be drawn only from randomized clinical trials, which are unlikely to occur. Nonetheless, our data highlight that TMT is an effective treatment option and should be considered for patients who are unable or unwilling to pursue cystectomy. Our study highlights the need for multidisciplinary clinics in which patients with MIBC may be managed optimally, considering patients’ comorbidities and perioperative risks as well as their personal values regarding quality of life. This is especially relevant as approximately 50% of patients with MIBC—even in recent years—do not receive any definitive treatment at all.

Author contributions: Tyler F. Stewart had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kumar, Kader, Cherry, Efstathiou, Rose, Stewart.

Acquisition of data: Kumar, Kader, Cherry, Courtney, Kotha, Nalawade, Rose.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kumar, Kader, Cherry, Riviere, Kotha, Rose, Stewart.

Drafting of the manuscript: Kumar, Kader, Cherry, Rose, Stewart.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kumar, Kader, McKay, Riviere, Kotha, Efstathiou.

Statistical analysis: Kumar, Kader, Nalawade, Riviere.

Obtaining funding: Rose.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Rose, Nalawade.

Supervision: Rose, Stewart.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Tyler F. Stewart certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Abhishek Kumar has equity stake in Sympto Health, unrelated to this work.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: Funding for this work was provided through National Institutes of Health, grant TL1TR001443(Abhishek Kumar, Daniel R. Cherry, Paul J. Riviere, and Patrick T. Courtney).

Associate Editor: Guillaume Ploussard

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2021.05.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Flaig T.W., Spiess P.E., Chair V. NCCN Evidence Blocks. 2020. NCCN guidelines version 3.2020 bladder cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gakis G., Efstathiou J., Lerner S.P. ICUD-EAU international consultation on bladder cancer 2012: Radical cystectomy and bladder preservation for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol. 2013;63:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hautmann R.E., Gschwend J.E., de Petriconi R.C., Kron M., Volkmer B.G. Cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: results of a surgery only series in the neobladder era. J Urol. 2006;176:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donat S.M., Shabsigh A., Savage C. Potential impact of postoperative early complications on the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients undergoing radical cystectomy: a high-volume tertiary cancer center experience. Eur Urol. 2009;55:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James N.D., Hussain S.A., Hall E. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1477–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park J., Jeong H. Bladder cancer. Elsevier Inc.; 2018. Morbidity, mortality, and survival for radical cystectomy; pp. 439–449. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamie K., Saigal C.S., Lai J. Compliance with guidelines for patients with bladder cancer: Variation in the delivery of care. Cancer. 2011;117:5392–5401. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray P.J., Fedewa S.A., Shipley W.U. Use of potentially curative therapies for muscle-invasive bladder cancer in the United States: results from the National Cancer Data Base. Eur Urol. 2013;63:823–829. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seisen T., Sun M., Lipsitz S.R. Comparative effectiveness of trimodal therapy versus radical cystectomy for localized muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol. 2017;72:483–487. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams S.B., Shan Y., Jazzar U. Comparing survival outcomes and costs associated with radical cystectomy and trimodal therapy for older adults with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:881–889. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efstathiou J.A., Choudhury A., Kiltie A.E. Utility of bladder-sparing therapy vs radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:185–186. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulkarni G.S., Klaassen Z. Trimodal therapy is inferior to radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer using population-level data: is there evidence in the (lack of) details? Eur Urol. 2017;72:488–489. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith A.B., Deal A.M., Woods M.E. Muscle-invasive bladder cancer: evaluating treatment and survival in the National Cancer Data Base. BJU Int. 2014;114:719–726. doi: 10.1111/bju.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Utrecht University Repository MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/44635

- 15.Dess R.T., Hartman H.E., Mahal B.A. Association of black race with prostate cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:975–983. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riviere P., Luterstein E., Kumar A. Survival of African American and non-Hispanic white men with prostate cancer in an equal-access health care system. Cancer. 2020;126:1683–1690. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulkarni G.S., Hermanns T., Wei Y. Propensity score analysis of radical cystectomy versus bladder-sparing trimodal therapy in the setting of a multidisciplinary bladder cancer clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2299–2305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wettstein M.S., Rooprai J.K., Pazhepurackel C. Systematic review and meta-analysis on trimodal therapy versus radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: does the current quality of evidence justify definitive conclusions? PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ploussard G., Daneshmand S., Efstathiou J.A. Critical analysis of bladder sparing with trimodal therapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2014;66:120–137. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giacalone N.J., Shipley W.U., Clayman R.H. Long-term outcomes after bladder-preserving tri-modality therapy for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: an updated analysis of the Massachusetts General Hospital Experience. Eur Urol. 2017;71:952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamid A.R.A.H., Ridwan F.R., Parikesit D., Widia F., Mochtar C.A., Umbas R. Meta-analysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared to radical cystectomy alone in improving overall survival of muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients. BMC Urol. 2020;20:158. doi: 10.1186/s12894-020-00733-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritch C.R., Balise R., Prakash N.S. Propensity matched comparative analysis of survival following chemoradiation or radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121:745–751. doi: 10.1111/bju.14109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.