ABSTRACT

Aging well is a priority in Canada and globally, particularly for older Indigenous adults experiencing an increased risk of chronic conditions. Little is known about health promotion interventions for older Indigenous adults and most literature is framed within Eurocentric paradigms that are not always relevant to Indigenous populations. This scoping review, guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s framework and the PRISMA-ScR Checklist, explores the literature on Indigenous health promoting interventions across the lifespan, with specific attention to Indigenous worldview and the role of older Indigenous adults within these interventions. To ensure respectful and meaningful engagement of Indigenous peoples, articles were included in the Collaborate or Shared Leadership categories on the Continuum of Engagement. Fifteen articles used Indigenous theories and frameworks in the study design. Several articles highlighted engaging Elders as advisors in the design and/or delivery of programs however only five indicated Elders were active participants. In this scoping review, we suggest integrating a high level of community engagement and augmenting intergenerational approaches are essential to promoting health among Indigenous populations and communities. Indigenous older adults are keepers of essential knowledge and must be engaged (as advisors and participants) in intergenerational health promotion interventions to support the health of all generations.

KEYWORDS: Indigenous health, healthy ageing, health promotion/intervention research, culture-based, community engaged, role of elders

Introduction

Ageing well, in place, is a priority topic in Canada as the proportion of older adults increases. Statistics Canada data indicate that Aboriginal1 [1] people are ageing faster than the general Canadian population and are reporting more chronic conditions earlier in life [2–4]. Population projections indicate that the proportion of Aboriginal peoples in Canada could increase from 4.4% of the population in Canada (2011) to up to 6.1% by 2036 [5]. Furthermore, although the Aboriginal population is on average younger than the general Canadian population, there is a more rapid ageing trend among Aboriginal older adults (the median age is predicted to increase from 27.7 years in 2011 to between 34.7 and 36.6 years by 2036) [5]. Evidence suggests that as we age, we are at greater risk of developing chronic health conditions that negatively impact health, wellness, and quality of life [6–9]. In fact, Indigenous populations have higher rates of chronic conditions, at an earlier age, compared with the general population in Canada [10–13]. These health disparities place Aboriginal older adults among Canada’s most vulnerable [4,8]. Despite this trend towards ageing and the increased risk of developing chronic health conditions among older Indigenous adults (OIA), little is currently known about health promotion intervention design and implementation processes that support healthy ageing for OIA. Rehabilitation specialists, researchers, health care providers, community stakeholders, and clinicians are keenly committed to narrowing health disparities and promoting healthy ageing across the lifespan. Presently, we are at a critical time to meaningfully engage Indigenous communities, and OIA specifically, in designing, implementing, and participating in intergenerational health promotion interventions [14–16]. This scoping review explores the literature on health promoting interventions that support Indigenous ageing well across the lifespan, how they locate Indigenous worldview, and how OIA are included in intervention design and implementation.

Ageing well for many older adults in Canada consists of ageing in place, in contexts where individuals can live independently and safely in “one’s own home”, surrounded by diverse supports and social networks, regardless of their function, age, and income [17–19]. Evidence indicates that rural older adults want to age in ways that nurture wholistic health which is inclusive of social interactions and maintenance of positive mental and cognitive wellness [17]. These priorities are also aligned with ageing well among OIA, who desire to “age in place”, in their communities, surrounded by their family, culture, language, and proximity to the land [9,16,18–28]. OIA are also considered keepers of essential knowledge [29]. Therefore as older adults pass this knowledge to younger generations they are also contributing to their own wholistic wellness by fulfiling their ageing responsibilities. Although evidence suggests that Indigenous health promoting intervention research must create space for a community-engaged approach to the design, implementation, and evaluation of health promoting interventions [24–26], this scoping review will clarify whether these important considerations are explicitly applied and described within the Indigenous health intervention research literature.

Much of the health promotion intervention literature that is focused on Indigenous health and wellness promotion, and prevention/management of chronic conditions, consists of a body of knowledge that is primarily based on Eurocentric ontology, epistemology, and axiology [30]. This approach may consider diverse paradigms and perspectives, such as those maintained among Indigenous worldview, but often does so in a superficial way that is layered over pre-existing Eurocentric frameworks. This superficial overlay generally translates to material and social representations that are distanced from their ontological and axiological underpinnings therefore rendering interventions potentially ineffective and unsustainable. Eurocentric, biomedical approaches to designing and implementing health promotion interventions support a standardisation of practice that often dissociates the human body from the reality of peoples’ daily lived experiences [14,30–32]. This Eurocentric approach focuses on binaries of “normal/not normal” and “well/not well” in ways that silence diverse social, cultural, and political factors that strongly influence health and wellness across an individual’s lifetime. Considering the historical and contemporary sociopolitical colonisation context of Indigenous peoples living in Canada, implementing health promoting interventions that are designed primarily from Eurocentric and biomedical approaches/perspectives will not redress colonisation, racism, and discrimination. Indigenous populations nationally and globally require that research, including health promotion and intervention implementation science, be “re-centred” on Indigenous knowledge systems, frameworks, and practices to ensure they account for sociopolitical, cultural, and historical contexts [33–37]. Furthermore, by privileging Indigenous knowledge and practices, interventions are more likely to be meaningful and relevant to Indigenous individuals and communities [33,38,39]. Privileging an Indigenous approach can create opportunities for transforming health promotion practice by bringing Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars, community members, and stakeholders to move beyond the binaries of Eurocentric practice. Building these spaces of mutual dialogue and action will simultaneously support healthy ageing across the lifespan among Indigenous peoples and communities [34,38–41].

Blackstock’s Breath of Life Theory and ecological framework [29] suggests that Indigenous peoples are trustees of knowledge and they rely on essential ancestral (historical) knowledge to be passed forward from past generations to future generations [29]. This passing of knowledge necessitates intergenerational interactions, engagement, and knowledge sharing between and among older adults and younger generations [29]. Furthermore, interactions and connections to the land and water are highlighted among OIA as key elements to maintaining/reclaiming Indigenous identity and promoting healing and wholistic health across the life trajectory [25,32,37,42]. One way in which to privilege Indigenous theories and frameworks in health promotion intervention design is to employ a Community-Based Participatory Action Research (CBPAR) approach to working in partnership with Indigenous communities [43]. CBPAR is an approach to conducting research by actively engaging community members as equal partners across all stages of the research process from design, implementation, analysis, and knowledge dissemination phases. Community perspectives are thus woven throughout and creating space for actionable change that is directly relevant to community experiences.

In this scoping review, we identify current health promotion interventions being implemented with (and among) Indigenous populations nationally and globally. We are interested in clarifying the role of OIA in health promotion programming, and in highlighting the health priorities and intervention activities within these health promotion programs. The findings in this paper will be relevant to Indigenous communities designing and implementing health promotion interventions and programs prioritising ageing well among OIA in Canada and across the globe.

Materials & methods

We focus our review on Indigenous community-engaged health promoting interventions described in the literature. These are defined broadly as community-based initiatives designed to prevent and manage chronic conditions (and their secondary and tertiary complications) and support healthy ageing across the lifespan. This scoping review applies Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework [44] with the aim of mapping the extent, range, and nature of relevant literature in the area of health promotion and intervention science specific to Indigenous populations. The steps included identification of the research question(s); defining and clarifying “community-based” and “community-engaged” terminology for inclusion/exclusion criteria; charting the data; summarising, collating, and reporting findings; and facilitating consensus among the co-authors of this manuscript. This scoping review followed the recommended process via the PRISMA-ScR Checklist [45].

Research questions

The research team consists of a Ph.D. candidate and physical therapist, a research coordinator and dietitian, an Associate Professor and medical anthropologist in the Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, and an Associate Professor and physical therapist in the School of Rehabilitation Science. The team collaboratively formulated the research questions and guided the study protocol and associated selection criteria. The questions that informed the scoping review included: What (and how many) health promotion interventions focus on supporting ageing well among OIA, particularly interventions focused on chronic disease management? Of these interventions, what level of community-engagement and inclusion of Indigenous perspectives were applied throughout the intervention design, implementation, and evaluation? Also, of these identified interventions, how are OIA engaged in the design and implementation of health promoting interventions? Lastly, what gaps exist in Indigenous health promotion interventions and programming that support intergenerational healthy ageing in the literature?

Defining & clarifying “community-based” and “community-engaged” terminology

Involving community members as partners in health promotion design from inception is a critical step to ensure the interventions are relevant, meaningful, and beneficial to community members. This is particularly important when working with Indigenous populations as it is a way to recognise and mitigate power imbalances that can often exist between researchers and Indigenous participants/community members, which are grounded in the historical context of colonisation and racism in Canada and other countries. Although community engagement is recommended (and often required) when working with First Nation, Inuit, and Métis peoples, the level of engagement may vary from project to project. Community engagement has been defined as “a process that establishes interaction between researcher (or research team), and the Indigenous community relevant to the research project” [43]. Further to this, the intent of community engagement is to create opportunities for community to decide upon the degree of collaboration they are interested in [43]. Therefore the level of community engagement may vary from acknowledgement (minimal to no engagement), to information sharing, to active participation, to empowerment, and to shared leadership of the research project [43]. It is for this reason that having one “gold standard” definition of community engagement is not possible and is contingent on the community’s choice regarding the level of engagement they are willing and able to do. Furthermore, there are other terms that are used interchangeably with “community engagement” such as “community-based”. With so many differing terms and levels of engagement that take place across a spectrum, we have chosen to use the Community Engagement Continuum [46,47] to inform our “community engagement” inclusion and exclusion criteria for this scoping review. Manuscripts were included if they described engagement at the levels of Collaborate, or Shared Leadership thus representing CBPAR and respectful and meaningful engagement [46]. We excluded the Outreach, Consult, and Involve categories as they did not meet our threshold of meaningful community engagement. Manuscripts were excluded if the research approach did not engage Indigenous peoples in the research process.

Data sources & search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was designed with the assistance of a university associate librarian. The search strategy included relevant keywords related to chronic conditions, Indigenous peoples, and population health interventions (Appendix I). Development of the search strategy began 21 October 2019 with the final search carried out 21 November 2019. Electronic databases covering a wide range of disciplines were used including Medline (OVID, 1946-Nov 2019), CINAHL (EbscoHost, 1937-Nov 2019), Embase (OVID 1947-Nov 2019), Web of Science, and SocINDEX (EbscoHost, 1908-Nov 2019). We limited the search to the most recent ten years (2009–2019) and the English language. Reference lists of articles included in our review were also scanned and relevant journals hand-searched to identify any additional articles for inclusion in the scoping review. This snowball technique was applied as one way to ensure a comprehensive search. All citations, including abstracts, were imported into reference management software, Endnote X9 [48] where duplicates were removed according to the technique by Bramer et al. [2016, 49].

Eligibility criteria & study selection

We limited the scoping selection to peer-reviewed papers that were subject to six main inclusion criteria (keywords and MeSH terms; timeframe of publication; level of community engagement; English only; chronic conditions; intervention and implementation science). The first criterion for inclusion was based on the search strategy (Appendix I). The second criterion was the timeline of publication, where only papers published between 2009 and 2019 were selected. The third criterion was based on the level of community engagement identified by the researchers, based on the Community Engagement Continuum (described previously). Papers that described a level of engagement equivalent to the definitions of Collaborate and Shared Leadership were selected. Those papers that did not describe engagement with Indigenous communities or fell within the Outreach, Consult, and Involve categories were not selected. The fourth inclusion criterion included papers written only in English. Studies focused on health promotion and/or prevention of chronic conditions (the fifth criterion) were selected for inclusion while those studies that examined acute illness were excluded. Last, manuscripts that focused on intervention and implementation science (the sixth criterion) were included while studies that primarily described or compared an intervention, or did not have an evaluative component, were excluded.

Relevance of articles identified from the search was then assessed using a three-stage process after undergoing initial article collation and deduplication. First, articles were manually screened by checking their titles and abstracts for identified keywords. One author screened all articles to make sure they were with Indigenous populations and included an evaluation of a health promotion intervention. Then, two authors went through selected articles and screened further for articles that included some level of engagement. A third author was consulted when consensus could not be reached by authors. We then read each full-text article (FTA) to clarify the level of engagement with Indigenous people in the research process (using the Community Engagement Continuum described above). The third stage involved reading all FTA’s retrieved from the first 2 screenings to identify articles that discussed issues related to health promotion intervention research design and implementation, interventions focused on supporting ageing well and managing chronic conditions among OIA, intergenerational approaches to health promotion, the role of OIA in the intervention research process, and other research gaps related to Indigenous health promotion supporting intergenerational healthy ageing in the literature.

Data charting & summary

Studies that were identified as Collaborate or Shared Leadership along the Community Engagement Continuum were included in a Microsoft Excel database (n = 46) for data entry, validation and coding. Data extracted from the selected articles included author(s), year of publication, study location, title, intervention type, duration of the intervention, identity of the Indigenous community and/or participants, and age groups, including the number of school-based studies. Other information was extracted from the selected articles including aims of the intervention study, targeted health priorities, methodology, intervention activities and design elements, outcome measures, and summary of the findings. We also identified the extent of older adult engagement in the design, delivery and active participation in health promotion research studies. Finally, we considered the various frameworks underpinning the health promoting interventions, clarifying whether Western or Indigenous frameworks were applied. Data charting was done independently with consultation among authors.

Consensus exercises

Consensus building among the co-authors was achieved through team meetings and discussion at several intervals during the search and data inclusion stages. Co-authors provided input on keyword selection, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and relevance of selections for each search strategy during face-to-face, video conference, and email communication. Clarification on methodological approaches were discussed as a team.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

The initial search in this review identified 5484 articles after duplicates were removed. This includes peer-reviewed articles from electronic databases, a search of relevant journals, and the reference lists of our included articles. Screening the titles and abstracts according to our predetermined eligibility criteria left 237 articles. The full texts were reviewed to identify those articles (125) that could be categorised as Consult, Involve, Collaborate, or Shared Leadership along the Community Engagement Continuum. According to our inclusion criteria, only those articles that met a certain standard of community engagement, that of Collaborate or Shared Leadership, were included in our final results for a total of 46 articles (Figure 1). See summary table (Table 1) of included articles stating the first author, year of publication, location, study design, framework, duration, ages and numbers of participants, evaluation, and outcomes.

Figure 1.

Article distribution by geographic location

Table 1.

Summary of articles in scoping review (n = 46)

| First author, year of publication, location | Study Design, framework, duration, participant ages and n | Evaluation & Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Adams, 2014 [54], USA | Healthy Children, Strong Families, 5-year randomised intervention using community-based participatory research (CBPR) and American Indian model of Elders teaching life-skills to the next generation. Qualitative. Children aged 2 to 5 years and their families, n = 1070. |

Successful interventions included community gardens and orchards, gardening and canning workshops, food-related policies and dog control regulations, an environmentally friendly playground, and providing access to recreational facilities. |

| Arellano, 2018 [55], Canada | Promoting Life Skills for Aboriginal Youth (PLAY) Utilisation-Focused Evaluation. 4 core components: after-school program, youth leadership program, sport for development programs, and diabetes prevention program. Qualitative. Intervention: youth; n = 88 communities. Evaluation: n = 9 interviews with PLAY project coordinators. |

Program was flexible and adaptable for individual communities, allowed meaningful youth contributions and leadership skills, and staff was passionate and committed. Recommendations: maintain flexibility, include Indigenous staff, ensure community-centred and owned, improve cultural sensitivity training |

| Bains, 2014 [56], Canada | Healthy Foods North, Community based intervention trial using social cognitive theory (SCT) and social ecological models (SEM). Quantitative. Women 19–44 years. Intervention: n = 79. Control: n = 57. |

> 70% did not meet recommended daily intake of fibre and vitamins D and E. Intervention: % with intakes < EAR or AI increased pre- to post- for all nutrients except vitamin B12, vitamin D, and zinc. Control: pre- to post-intervention situation of adherence to nutrient recommendations did not change for vitamins B12 and E, iron and zinc; and the proportion of people with fibre intake < AI decreased post-intervention. The intervention increased the overall intake of vitamins A and D, possibly due to promotion of traditional foods in the intervention group. |

| Brown, 2013 [57], USA | Journey Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach using Transtheoretical Model-Stages of Change and Social Cognitive Theory; adapted for Native youth. An intervention and comparison group pre- post- design. 9 sessions were taught over 3 months. Quantitative. Youth 10–14 years, n = 64. |

95% of participants said they would recommend the program No significant changes in nutrition according to diet recall data. The Journey DPP group increased their overall nutrition KAB (knowledge, attitudes and beliefs) score by 8%, whereas the comparison group score did not change. Accelerometer data worsened for both groups. Daily self-reported screen time decreased by 0.4 hours in the Journey DPP group and increased by 1.1 hours in the comparison group. Both groups showed small increases in BMI. |

| Bruss, 2010 [58], Other Oceania | Project Familia Giya Marianas. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) and quasi-experimental crossover design using curriculum development and ROPES (review, overview, presentation, exercise, and summary). Quantitative. 3rd grade children and their caregivers (ages not specified), n = 407 children. |

The study showed program-dependent effects on BMI z-score influenced by baseline BMI and degree of participation. Students in the healthy weight group, whose caregivers did not attend showed increased BMI z-scores, while those whose caregivers attended 5–8 sessions showed no change in BMI z-score. Subjects who were overweight or at risk of overweight and whose caregivers completed 1–4 and 5–8 sessions had a significant drop in BMI z-score, while those whose caregivers did not attend had no significant change. “At baseline, 90% of caregivers thought their children would grow up to have healthy weights. |

| Carlson, 2019 [59], New Zealand | Cardiovascular Disease Medicines Health Literacy Intervention with pre- and post-session data collection using a Kaupapa Māori evaluation (KME). Qualitative. Intervention: 3 sessions 30–75 mins. The 1st 2 sessions were 1 week apart and the 3rd a month later. n = 56 Evaluation: 3 interviews 60–120 mins. The 1st 2 sessions were 2 weeks apart and the 3rd 6–7 months later. Weekly telephone calls conducted for the 1st month lasting 10–30 mins. Adults (ages not specified), n = 6 and 3 health professionals. |

Participants outlined benefits: gained knowledge of medications and a sense of relief having questions answered. They also talked about medications with family, and shared knowledge with others. Health professionals indicated patients’ improved knowledge made it easier to confirm what medications they were taking and allowed patients to be more involved in self-care. Although, medication knowledge decreased over time. The most effective feature of the intervention was that it supported relationship building to overcome changing health professionals. |

| Carlson, 2016 [60], New Zealand | Cardiovascular Disease Medicines Health Literacy Intervention with pre- and post-session data collection using a Kaupapa Māori evaluation (KME). Qualitative. Intervention: 3 sessions 30–75 mins. The 1st 2 sessions were 1 week apart and the 3rd a month later. n = 56 Evaluation: 3 interviews 60–120 mins. The 1st 2 sessions were 2 weeks apart and the 3rd 6–7 months later. Weekly telephone calls conducted for the 1st month lasting 10–30 mins. Adults ≥20 years, n = 6 and 3 health professionals. |

The whānau (family group) is important to patients. They have responsibility to their whānau and their health and wellbeing is interwoven with that of their whānau. Connection between patients and health professionals was very important to patients. Patients gained a sense of wellbeing, security, and peace of mind. |

| Crengle, 2018 [61], International (Australia, Canada, New Zealand) | A multisite pre–post design with multiple measurement points using education sessions with tablets, content adapted for different cultures. 3 education sessions delivered over 1 month. Quantitative. Adults ≥20 years (mean = 62), n = 171 |

Outcome measures differed across sites. The intervention resulted in significant increases in knowledge that were highest after the first session, still observed in others, and maintained between sessions, indicating participants were able to retain and recall information. |

| Dodge Francis, 2012 [62], USA | Development of the Diabetes Education in Tribal Schools (DETS) based on the Diabetes Prevention Program adapting a curriculum for American Indian children and youth. Children and youth K-12; evaluation: n = schools in 14 states |

Teachers rated all Native American content areas of the DETS curriculum as “strong” or “very strong”. Students demonstrated statistically significant knowledge gains across all content areas and grades. |

| Dreger, 2015a [63], Canada | 2nd part of a 2-phase, sequential mixed-method design using a Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction with modifications for Indigenous; framework analytic approach. Qualitative. Intervention: 8 weekly, 2-h group sessions with home practice of 20–30 mins/day, 5 days/ week. Evaluation: 2–6 weeks following program, interviews lasted 40–65 mins. Adults ≥18 years, intervention: n = 12. Evaluation: n = 11 (mean age = 60 years, majority were female). |

Participants attended 6.8 sessions on average. Participation resulted in increased awareness, improved health awareness and well-being, changes to behaviour and attitude, and positive regard for the program. For example, participants became aware of reaching for snacks when bored. Participants reported lower blood glucose, better sleep, more energy, fewer headaches, better control over emotions, less worrying, less stress, improved relaxation, and better self-regard. “After the first session, I realized I was just kinda walking a lot softer on the planet”. Participants did not have a preference for an Indigenous instructor, but instead emphasised the importance of a connection to community and interactions that are kind, open, nonjudgmental, genuine, and trustworthy. |

| Dreger, 2015b [64], Canada | Quasi-experimental design using Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction with modifications for Indigenous; framework analytic approach. Baseline (within 1 week prior to the start of the intervention), post-intervention (within 1 week of the final session), and follow-up (approx. 2 months after the completion of the program). 8 weekly, 2-h group sessions with home practice of 20–30 mins/day, 5 days/ week. Quantitative. Adults ≥18 years (mean = 60), n = 11, majority female. |

HbA1c significantly decreased by .43% from baseline to post-intervention. Less life stress at baseline was associated with significantly greater decreases in HbA1c at post-intervention. Significantly greater changes in HbA1c were observed for those living off-reserve than on-reserve both at post-intervention and follow-up. There were significant changes seen over time in mean arterial pressure, yet no significant changes were seen in weight. Significant improvements were seen on the general health and emotional well-being scales. Participants who had diabetes longer saw a larger decrease in symptoms. |

| Englberger, 2011 [65], Micronesia | An island state’s community, inter-agency, participatory programme and awareness campaign using an ethnographic multiple-methodology to develop education and media campaigns; inter-agency community based collaboration, advocacy, participatory activities and social marketing; formation of an NGO. Project duration = 10 years. Mixed methods. All ages, n = the island state of Pohnpei. |

Banana market studies: Inexpensive, nutrient rich banana varietals grown on the island, but not previously consumed by citizens, now sold in up to 8 of 14 markets across the island. KI interviews indicated eating more bananas due to messaging around ‘happiness’ (many youth did not respond to health messaging, but instead ‘happiness’) and promotional film. |

| Fanian, 2015 [66], Canada | The Kὸts’iὶhtła (“We Light the Fire”) project; a 5-day creative arts and music workshop developed using their own evaluation framework. Qualitative. Youth 13–22 years. Intervention: n = 9 youth. Evaluation: n = 4 youth and 5 facilitators |

Facilitators thought youth developed new skills, had positive interactions, enjoyed the workshop and found it culturally relevant and used the arts to talk about community concerns (alcohol, cyber bullying, and suicide) and ideas for change. Several of the youth showed a noticeable increase in confidence, going from very shy to confident by the end of the week. |

| Harder, 2015 [67], Canada | Community-based participatory approach and interpretive phenomenology and decolonising and critical Indigenous methods. Mixed methods. Youth, mean age = 14.85 years. Intervention: n = 130 (62 males and 68 females) attended 9 cultural camps. Evaluation: n = 58 |

Youth noted the following improvements: knowledge of the Carrier language (87%), knowledge of their traditional culture (96%), connection to Elders (92%), opinion of themselves (90%). Risk taking behaviours decreased: desire to drink alcohol (55%) and desire to take illegal drugs (58%). Acquiring new culturally relevant skills and making interpersonal connections resulted in personal growth, self-awareness, positive development, and identity. |

| Hibbert, 2018 [68], Canada | This project used a community-based participatory approach and adapted version of Donnon and Hammond’s (2007a) Youth Resiliency: Assessing Developmental Strengths Questionnaire. Quantitative. Youth 7–14 years (mean for 7–10 group = 8.43, mean for 11–14 group = 12.26). Pre-program survey: n = 175 (110 aged 7–10 and 65 aged 11–14). Post-program survey: n = 119 (68 aged 7–10 and 51 aged 11–14). |

Significant positive changes were observed in both age groups: self-esteem, drug resistance, planning and decision-making, risk factor statements, and external family support. Negative changes were observed in reported sense of empowerment and safety, external support from peers, learning and achievement, and self-actualisation. |

| Ing, 2018 [69], USA | Partnership for Improving Lifestyle Intervention (PILI) Lifestyle Program (PLP) at work (PILI@Work) using behavioural change principles from the social cognitive theory and motivational interviewing. PILI@Work = adaptation of PLP to worksites with many NHOPI employees. 3-month weight loss phase: 4 lessons every other week for 2 months. 9-month weight loss maintenance phase: 7 monthly lessons. Quantitative. Adults ≥18 years. FFG group: mean = 48.2 years. DVD group: mean = 43.7 years. 3-months: n = 217 employees (15 worksites). 9-months: n = 156 |

Significant increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (bp), and decrease in exercise frequency and a more internal locus of weight control. 60% successfully maintained their weight loss at 12 months. The number of lessons attended in Phase 1 was a significant predictor of % weight loss at 12 months. Systolic bp at baseline also predicted % weight loss at 12 months. No difference was observed between delivery methods (face-to-face vs. DVD) on weight loss maintenance. |

| Janssen, 2014 [51], New Zealand | Te Hauora O Ngāti Rārua programme using a Kaupapa Māori approach. One-on-one education and case management, a 6-week group education course, and an on-going diabetes support group. An embedded case study evaluation. Mixed methods. Adults 17–75 years (ages 17–30, n = 1; 31–45, n = 1; 46–65, n = 4; 65–75, n = 1) n = 7 clients and n = 5 health practitioners. |

Co-morbidities affected clients’ diabetes self-management. All clients showed improved knowledge and awareness related to diabetes and how to make personal changes while 4 clients saw short term improvements in health outcomes, but did not maintain them when support decreased. Health literacy improvements included better knowledge about food and exercise and maintaining overall wellness. |

| Jeffries-Stokes, 2015 [70], Australia | Western Desert Kidney Health Project used community arts centred on community consultation, participation and dialogue. Qualitative. All ages. 38% of the total population in the study communities in Western Australia’s Goldfields, including 80% of the Aboriginal population (n = 1115). > 2000 people, including all children in 10 community schools (n = 1300), attended activities as participants or audience. |

Art was an important way to promote health and joy in communities. Only positive feedback from the community was received. Communities use the health information, knowledge and support provided to advocate and achieve change in their communities: all 5 towns (previously 3) now have a grocery store that focuses on fresh food, 2 towns and 2 communities also planted fruit trees in public gardens, and all remote community schools and most town schools have new fruit and vegetable gardens. |

| Kaholokula, 2012 [71], USA | Partnership to Improve Lifestyle Interventions (PILI) ‘Ohana Project; an adaptation of the Diabetes Prevention Program Lifestyle Intervention (DPP-LI). A family and community weight loss maintenance program using a community-based participatory approach. PILI Lifestyle Program (PLP), 6 monthly sessions, 1.5 hrs each in groups (6–10 people); and standard behavioural weight loss maintenance program (SBP), 6 monthly phone call follow-ups 15–30 mins each. Quantitative. Adults ≥18 years. PLP group: mean = 50 years, n = 72. SBP group: mean = 49 years, n = 72. |

Retention was 68% in PLP and 71% in SBP. Older participants completed more sessions than younger participants. Statistically significant weight loss maintenance was observed in both interventions. The PLP group was 2.5 times more likely to maintain pre-intervention weight than SBP. Among the 76 of 144 participants who completed ≥3 of 6 lessons, PLP participants were 5.1 times more likely to maintain pre-intervention weight compared to the SBP group. |

| Kaholokula, 2014 [72], USA | Translated Diabetes Prevention Program Lifestyle Intervention (DPP-LI) using a fully engaged a community-based participatory approach and a pre- post-intervention evaluation. Lessons were 1–1.5hrs, delivered in groups (10–20 people) with the 1st 4 lessons delivered weekly and the 2nd 4 delivered every other week for 8 weeks. Quantitative. Adults ≥18 years (mean = 51), n = 239; 71% Native Hawaiian and 84% female. |

Significant improvements: weight loss (in comparison to pilot testing), systolic and diastolic BP, physical functioning and activity level, and dietary fat intake. However, results differed across the different types of community-based organisations (CBOs) where delivered. One CBO was in one neighbourhood so more likely to form community walking/fitness/dance groups due to social networks. They also demonstrated one of the highest mean weight losses and they were the only CBO that yielded significant improvements on all clinical and behavioural measures. |

| Kakekagumick, 2013 [73], Canada | The Sandy Lake Health and Diabetes Project (SLHDP); a modification of a curriculum developed by Kahnawake Mohawk community in Quebec and the CATCH curriculum; a model of culturally appropriate participatory research. Quantitative. All ages (ages not specified). Home visit program had 5 visits per family (n = 115), the diabetes radio show airs once/week, the school-based diabetes curriculum, school program evaluation (n = 122). |

The home visit program was deemed unsustainable (lack of funding, labour-intensive, and lack of community interest) and discontinued after the 1-year trial period. The school program evaluation indicated improvements in diet intention, diet preference, and knowledge of curriculum, diet self-efficacy, dietary fibre intake, and screen time. The 2nd school evaluation showed significant improvements in self-efficacy and knowledge of health, nutrition, and screen time. However, these did not translate into direct physical activity improvements. |

| Kaufer, 2010 [74], Micronesia | Participatory, food-based approach. Quantitative. Adult women (ages not specified), n = 40 households completed diet records. |

Average daily energy and carbohydrate intake decreased significantly while protein and fat did not change. Average BCE intake increased significantly. Consumption of giant swamp taro, all banana types, local vegetables, all fruit, local drinks, snacks, chicken eggs, liver, and imported meat increased significantly. The frequency of sugar consumption (from imported foods such as well as sugar added to local foods or drinks) decreased significantly. However, consumption of imported drinks with sugar increased significantly. Diet diversity significantly increased. Awareness of a variety of community groups was > 80% with ≥ 50% of households having participated. Participants learned the connection of local food to health, of adding home-grown vegetables to meals, of physical activity and health, and the transfer of information from youth to adults. |

| Kolahdooz, 2014 [75], Canada | A community-based, multi-institutional nutrition intervention program using a quasi-experimental intervention evaluation with a pre- post- design. Intervention occurred at the community level. Quantitative. Adults ≥19 years. Intervention group: mean = 45.5 years, n = 221. Control group: mean = 41.9 years, n = 111. |

Consumption of de-promoted foods and the utilisation of unhealthy cooking decreased. The intervention group reduced their intake of de-promoted high-fat meats, high-fat dairy, refined grain products, and unhealthy drinks by more than the control group. There was a reduction in energy, protein, and carbohydrate intake, and overall Body Mass Index (BMI) as well as an increase in vitamin A and D intake. |

| Mau, 2010 [76], USA | Used CBPR and a new conceptual model of weight loss based on focus groups and key informant interviews using social action theory of behaviour change, using a thematic data analysis approach to culturally adapt the DPP-LI. Qualitative for adaptation of program. Quantitative to evaluate intervention. Intervention: 8 lessons, 1.5 hrs each over 12 weeks in groups (6–12 people) in community settings. Adults ≥18 years (mean = 49), n = 239; 83% female 52% self-identified as Native Hawaiian and 27% Chuukese; and key informants. |

All clinical and behavioural measures (weight, BMI, bp, 6-min walk test, dietary fat intake, and physical activity) significantly improved at the 12-week follow-up. Participants who completed all 8 lessons lost significantly more weight than those who completed <8 lessons. |

| McShane, 2013 [77], Canada | A community-based participatory approach using oral and visual media in a CD-Rom presented by an Inuk Elder in Inuktitut. Pre- post-design used to evaluate expectations vs. delivery. Follow-up was 3 months following the intervention. Mixed methods. Mean age = 39.2 years, n = 40 (9 males and 31 females) |

Results indicated overall satisfaction with the intervention and many were likely to recommend the CD-Rom to others. Following the intervention, people were more likely to think the CD-Rom was similar to an in-person conversation. With a facilitator present, feedback indicated the tool was easy to navigate. Community members thought the technology was a practical and cost-effective way to connect those in urban areas with Elders in the north. Participants requested more information on health promotion topics, particularly around parenting young children. |

| Mead, 2013 [78], Canada | A multilevel, multi-institutional nutritional and physical activity intervention developed using formative research, a community based participatory approach, and behavioural change strategy drawn from social cognitive theory and social ecological models. A quasi-experimental pre- post-evaluation. Quantitative. Mean age = 42.4 years. Intervention: n = 246 (199 women, 47 men). Comparison: n = 133 (112 women, 21 men). |

The average frequency of unhealthy food acquisition significantly decreased in the intervention compared to comparison groups. The intervention did not impact BMI, although results did differ by weight. The intervention was associated with improved self-efficacy, and more improvements were observed in the psychosocial and knowledge variables among those with higher SES. All psychosocial variables significantly improved from baseline after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, and BMI variables. |

| Mendenhall, 2010 [79], USA | The Family Education Diabetes Series (FEDS) using CBPR and The Citizen Health Care Model. Baseline, 3 and 6 months. Quantitative. Intervention: 3 hrs every other week for 6 months. Adults 22–80 years (mean = 55), n = 36 (79% female). |

Blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) and HbA1c significantly decreased from baseline to 3-month follow-up, although they did not improve further at the 6-month follow-up. Average weight loss significantly improved at the 6-month follow-up. |

| Mia, 2017 [50], Australia | The Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing program using Participatory Action Research and conceptual framework by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal psychologists as a decolonising strategy to promote wellbeing and an Aboriginal Knowledge Framework. Mixed methods. Intervention: 12 months and is delivered as three, six week long, blocks. Adults: men and women; diversity across age groups (ages not specified). Intervention: n = 159 (53 men and 106 women). Evaluation: n = 30 |

Allowed to more positively and constructively focus on their own needs resulting in individual healing, and their family’s needs, which strengthened both family and community relationships. Overall, participants are now more confident, empowered, have a stronger sense of cultural identity and pride, and greater appreciation for health and wellbeing. |

| Micikas, 2015 [80], Guatemala | Development of Caminemos Juntos (Let’s Walk Together) using Stages of Change Theory, and Health Belief Model. Weekly diabetes club meetings in groups of 15–20 and weekly home visits and preconsults in clinic for a duration of 7 months. Quantitative. Adults ≥18 years (ages not specified). Pre- post- design (baseline and 4 months). Intervention: n = 104; evaluation: n = 52. |

Barriers to insulin use in this setting include lack of access, cost, lack of refrigeration, and insufficient nursing experience in managing complications with insulin. Knowledge of recommended levels of HbA1c and fasting glucose, and that food increases blood glucose significantly increased at 4-month follow-up as did actual mean HbA1c levels. No significant change in mean BMI was observed. The health beliefs and practices survey did not produce significant results. |

| Mills, 2017 [81], Australia | The Work It Out program developed their own conceptual framework and a quasi-experimental, pre-post-test design. ≥2 sessions (45 mins ‘yarning’ and 1 hr exercise) per week for 12 weeks. Quantitative. Adults ≥18 years (mean = 55.26). Intervention: n = 315. Follow-up: n = 85 (72% female). |

6MWT significantly increased at follow-up. Those in the extremely obese group (BMI) significantly reduced their weight. Blood pressure (bp) significantly increased in those with normal bp at baseline. Those who had high systolic bp at baseline showed significant decreases at follow-up. After adjusting for baseline diastolic bp and age, those with one cardiovascular condition had a greater average decrease in diastolic bp at follow-up than those without a cardiovascular condition. |

| Murdoch-Flowers, 2019 [14], Canada | Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project (KSDPP). Using a CBPR approach, interventions developed by community member/traditional healer/traditional knowledge holder using a holistic Haudenosaunee perspective. Naturalistic and interpretative inquiry and grounded theory. Qualitative. Adults 25–69 years (mean = 47); and 1 key informant. |

Participants reported improvements to perceived mental, physical, spiritual and social health through activities such as cooking, physical activity (strength, balance, flexibility, weight-loss, and pain relief), stress relief, learning Mohawk spirituality, and making social connections. |

| Nagel, 2009 [82], Australia | RCT using a participatory action research model with framework to guide practitioners in culturally adapted treatment. Baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months. 2, one-hour sessions 2–6 weeks apart. Mixed methods. Adults ≥18 years (mean = 33), n = 49 patients and n = 37 carers. |

3 patients withdrew consent and 2 committed suicide during the 18 months. The intervention improved mental health ratings using standardised tool Greater improvements were seen in the motivational care planning group, particularly around well-being, life skills, and alcohol dependence, compared to the treatment as usual group, and improvements were sustained over time. |

| Pakseresht, 2015 [83], Canada | Healthy Foods North, designed using CBPR and evaluated using a quasi-experimental study design. Duration 14 months. Quantitative. Adults ≥19 years. Intervention: mean age = 47.14 years. Control: mean age = 42.77 years. Evaluation: n = 378 (majority female). |

Energy intake decreased while intake of vitamins A and D increased, the primary source of which was traditional foods, which were promoted in the intervention. Consumption of traditional foods increased by 21% in the intervention group compared to 3% in the control group. |

| Payne, 2013 [52], Australia | A holistic style and a pragmatic method, allowed participants a key role in their self-management plan. 8 weekly sessions. Evaluation used a pre- post-design. Mixed methods. Elders with diabetes or family members with diabetes. Women and their children (ages not specified). |

Technical knowledge of diabetes management saw slight improvements. Improvements were made regarding diet and exercise, and physical activity was seen as an important part of an integrated self-management plan. Women’s awareness increased around the symptoms and impact of depression and the intervention fostered open communication about this illness among them. At the time of the report, the group had continued to connect for > 2 years. |

| Rolleston, 2017 [84], New Zealand | Used a Kaupapa Māori methodology to develop a 12-week exercise program, including attending clinic 3x/week. Aerobic-only program for 1st 6 weeks and aerobic and resistance training for next 6 weeks. Mixed methods. n = 9 (6 male, 3 female). Mean age = 51.5 years. |

SBP, Waist and hip circumference significantly decreased while HDL-C increased during the 12-week programme. Quality of life also improved. |

| Seear, 2019 [85], Australia | ‘Maboo wirriya, be healthy’, a diabetes prevention program was adapted locally and led by community. 8 weekly sessions, 1.5 hrs each for 2–3 months. Mixed methods. Adults 18–38 years. Intervention: n = 10 (7 women and 3 men), majority ≤25 years. Post-program: n = 6 (3 women, 3 men). 6-month follow-up: n = 4. |

Participants reported gaining new knowledge and changing their behaviours, particularly those around food shopping and portioning and soft drink intake. |

| Sinclair, 2013 [86], USA | Partners in Care curriculum was designed and evaluated with African Americans and Latinos and then adapted for Indigenous using social cognitive theory. This study used a two-arm RCT with follow-up at 3 months. Quantitative. Adults ≥18 years. Intervention: n = 48, mean age = 53 years. Control: n = 34, mean age = 55 years (majority female). 3-month assessment: Intervention: n = 34; control: n = 31. |

Significant changes were observed from baseline to 3 months between the intervention and control groups for HbA1c and understanding and performance of diabetes self-care. When analysed separately, significant differences were noted in the mean baseline diabetes-related distress score for Filipinos compared to Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. |

| Smylie, 2018 [87], Canada | International Assessment of Literacy Skills (IALS): a single arm pre-post trial with multiple measurement points. 3 education sessions. The 2nd session after 1 week and the 3rd session after another 4 weeks. Quantitative. Adults ≥20 years (mean = 58.7), n = 47. |

Unadjusted mean knowledge scores of all 4 medications were significantly higher after attending 3 education sessions. Improvements in health literacy decreased the likelihood of risk of medication error with participants having near-perfect medication knowledge scores following the intervention and improved the likelihood of them sharing CVD knowledge. 91% referred to the program medication booklet and 45% used their customised pill card. |

| Stewart, 2015 [88], Canada | This multisite, interdisciplinary study used a multimethod participatory research design for psychosocial interventions. Parents of children with asthma and children/adolescents with asthma. (ages not specified). Mixed methods. Alberta: 8 support group sessions through Telehealth for rural participants with face-to-face support, and in-person for urban participants. n = 20 parents/caregivers (n = 8 on reserve and n = 12 urban). Manitoba: face-to-face support groups, n = 3 parents. Nova Scotia: 2-day asthma camp; n = 17 rural parents with their children. |

Loneliness mean scores decreased significantly at post-test. Parents thought the intervention improved awareness of asthma in their community. Participants learned from others in the support group. Manitoba: Parents thought the intervention was interactive, engaging, cultural, and community driven and they appreciated that information was presented within the context of traditional practices Nova Scotia: Caregivers appreciated that the asthma camp connected them with their peers and thought the camp reduced their loneliness, improved asthma support and education, enabled social learning, and enhanced communication strategies. |

| Teufel-Shone, 2014 [89], USA | Youth Wellness Program, a 2-year intervention 2x/week 45–60 mins each. Quantitative. Children in grades 3–8, n = 109 (60 male and 49 female). After 2 years, 138 students participated in ≥1 assessment session and 71 students participated in ≥3 assessment sessions. |

Following the intervention, more participants were overweight and obese, had normal fasting blood glucose, had prediabetes and fewer had diabetes. Girls showed significant improvements in curl-ups, push-ups, and the PACER (Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run) while boys had significant improvements in push-ups. |

| Tomayko, 2016 [90], USA | Healthy Children, Strong Families, an American Indian model of Elders teaching life-skills to the next generation developed using a CBPR process. Mixed methods. 12 monthly in-home sessions, 1 hr each vs. monthly mailed information and group meetings. Baseline, year 1 and maintenance over year 2. Children 2–5 years and caregivers, n = 150 child–caregiver dyads (n = 67 in the mentored group and n = 83 in the mail group); 25 caregivers participated in focus-groups after year 2. |

The method of toolkit delivery had no effect. Overall, mean BMI percentiles decreased in overweight and obese children post-intervention and the weight trajectory of adult participants improved compared to the control group. Consumption of vegetables and fruit significantly increased among children and screen time decreased in children and adults despite no changes in activity or sedentary time resulted from accelerometry data. Time spent together as a family increased, particularly around family meals and reading together with children often motivating families. |

| Tomayko, 2019 [91], USA | Healthy Children, Strong Families 2, an American Indian model of Elders teaching life-skills to the next generation, using a randomised controlled trial with modified crossover design to an obesity prevention intervention (Wellness Journey) or a control group on child safety (Safety Journey). Baseline and year 1. Mixed methods. Wellness: 12 monthly mailed healthy lifestyle lessons, items, and children’s books, to address 6 intervention objectives. Safety: 12 monthly mailed safety newsletters and related materials. Adults (mean age = 31.4 years, 95% female) and a dependent child 2–5 years (mean age = 3.3 years). 25 caregivers participated in focus-groups after year 1. n = 450 adult/child dyads with a 16% drop-out rate at year 1. |

Adults and children in the Wellness Journey group had a greater improvement in healthy diet pattern post-intervention compared to the Safety Journey group. Adults in the Wellness group had a significant increase in servings/wk of vegetables and fruit and 15-min periods of moderate to vigorous physical activity compared to those in the Safety group. No differences resulted between either intervention group for adult or child BMI. Adults in the Wellness group had significant increases in readiness to change when it came to physical activity, vegetable and fruit consumption, screen time, and sleep compared with the Safety group. Families were highly satisfied with the intervention and spend more time together reading and doing activities. Children were excited to receive materials by mail, which facilitated their participation and allowed them to work at their own pace. Receiving a book with each lesson was particularly appreciated. Many families indicated wanting to connect with other families in a “real world” setting”. |

| Townsend, 2016 [92], USA | PILI@Work, adapted Diabetes Prevention Program DPP-LI based on social cognitive theory. 8 interactive 1-hr lessons over 12 weeks including 10–20 people per group. Quantitative. Adults ≥18 years (mean = 46.2), majority female, n = 275. At a 3-month assessment, n = 217. |

Participants lost 1.2 kg on average and had significant improvements in fat intake, eating self-efficacy, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. For each kg of weight lost, risk of T2DM reduced by 13%. Results did not indicate any differences across ethnic groups, although results did vary by worksite. |

| Tracey, 2013 [93], Australia | The Goldfields Kidney Disease Nursing Management Program (GKDNMP) used a framework developed by the Western Australia Renal Disease Health Network. Delivery of renal clinics, nurse clinics, using videoconferencing when necessary. Quantitative. Details on ages and n not provided. |

The program resulted in improved access and delivery of culturally sensitive renal health care services. The community renal nurse role allowed for more consultations and outpatient renal clinics and decreased the number of transfers needed. This was possible due to engagement with communities to identify Aboriginal people who may be unable to attend clinics and require extra support (transport and accommodation) and assisting them. Improvements to health service delivery has been demonstrated by requests from Aboriginal communities for more clinics and visits, and improved attendance at clinic and dialysis. |

| Wakani, 2013 [94], Canada | This project followed Turton’s (1997) health world view framework using participatory research. Piloted a Bingo intervention on one night. Qualitative. Adults in their mid-20s to early 50s, n = 17 (majority female) plus clinic staff. |

The intervention was reported to be fun, informative, and educational. Participants suggested further hands on activities, expanded community outreach, and providing pamphlets on diabetes. At the time of this report, the intervention was scheduled monthly at the clinic. As a result of this project, the “Health and Diabetes Workshop Series” was developed and was to be delivered 4 times/year at the clinic. |

| Ziabakhsh, 2016 [53], Canada | The Seven Sisters project was informed by Indigenous healing perspectives, transcultural nursing, and feminist theories of health and illness. It was piloted as a gender- and culturally responsive model to promote activities for heart-health using a holistic approach. A 2-hr weekly women only group over 8 weeks. Women attended an average of 7 sessions. Mixed methods. Adult women: mean age = 58 years, n = 8. |

Following the intervention, women reported healthier eating including consuming more vegetables and fruit. Some women improved their level of participation in fitness activities. All were more mindful of the importance of activity for physical and mental wellness and many changed their emotional health. One of four smokers decided to try to quit. The integration of Indigenous culture was valued by participants as was the emphasis on relationships and promoting positive messages around self-care. The talking Circle was identified as the best part of the group experience and participants felt safer sharing and discussing sensitive issues in a women-only group. Participants did not like being weighed, wanted the intervention to last longer, and thought there was too much paperwork/forms. |

Age distribution

When examining age groups included in interventions, the majority of articles described interventions for adults [29] while five targeted children (2–8 years), four were for youth (6–25 years) and two for both children and youth (5–14 years). There were six articles whose interventions targeted all age groups. Very few articles gave the age range and instead reported the mean, making it difficult to categorise studies according to targeted age group. Although this should be interpreted with caution, based on reported mean ages, we can further break down the adult age group into 16 articles on young adults younger than 55 years, 8 articles on older adults 55 years of age and older, and 5 articles that did not specify the ages of the adults who participated. Three of the articles examining children and/or youth interventions were located in schools while another four articles included some sort of school-based initiative or after-school programme.

Study characteristics

Study characteristics include geographical location, ethnicity, level of community engagement, framework applied, health priority, intervention focus, and whether health promotion interventions were intergenerational (Table 2).

Table 2.

Indigenous and community engagement details of articles (n = 46)

| First author, Year of publication | Location, Ethnicity | Level of Community Engagement | Framework | Health priority | Intervention Activities & Elements | Intergenerational |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams, 2014 [54] | USA, American Indians | Shared Leadership | Indigenous: AI model of Elders teaching life-skills to younger generation and reinforce cultural values of family and traditional food and activity | Obesity | Mixed: healthy eating, physical activity | Not specified |

| Arellano, 2018 [55] | Canada, Indigenous (Ontario, Manitoba, British Columbia, Alberta) | Shared Leadership | Western: Utilisation-Focused Evaluation | Diabetes | Mixed (diabetes prevention, leadership, physical activity, nutrition, health and wellness) | Advisor: design and delivery |

| Bains, 2014 [56] | Canada, Inuit and Inuvialuit (Nunavut and Northwest Territories) | Collaborate | Western: Social Cognitive Theory and Social Ecological Models | Chronic disease | Healthy Eating | Not specified |

| Brown, 2013 [57] | USA, Northern Plains Indians (Montana) | Collaborate | Adaptation: Transtheoretical Model-Stages of Change and Social Cognitive Theory, adapted for Indigenous youth | Diabetes | Mixed (Diabetes prevention, healthy eating, physical activity) | Advisors: delivery only |

| Bruss, 2010 [58] | Other Oceania (Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands) | Collaborate | Western: curriculum development and ROPES (Review, Overview, Presentation, Exercise, Summary) | Obesity | Mixed (physical activity, healthy eating, self-esteem) | Not specified |

| Carlson, 2019 [59] | New Zealand, Māori | Collaborate | Indigenous: Kaupapa Māori | Cardiovascular Disease | Health Literacy | Advisors: design only |

| Carlson, 2016 [60] | New Zealand, Māori | Collaborate | Indigenous: Kaupapa Māori | Cardiovascular Disease | Health Literacy | Not specified |

| Crengle, 2018 [61] | International (Australia, Canada, New Zealand) | Collaborate | Adaptation: education sessions with tablets, content adapted for different cultures | Cardiovascular Disease | Health Literacy | Not specified |

| Dodge Francis, 2012 [62] | USA, American Indians/Alaska Natives | Collaborate | Adaptation: curriculum for AI/AN children and youth | Diabetes | Mixed (Knowledge of health and diabetes; school-based) | Not specified |

| Dreger, 2015a [63] | Canada, First Nations and Métis (Manitoba) | Collaborate | Adaptation: mindfulness practices based on Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) guidelines with modifications to tailor the program to Aboriginal peoples | Diabetes | Quality of Life | Advisors: design and delivery |

| Dreger, 2015b [64] | Canada, First Nations and Métis (Manitoba) | Collaborate | Adaptation: mindfulness practices based on Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) guidelines with modifications to tailor the program to Aboriginal peoples | Diabetes | Quality of Life | Advisors: design and delivery |

| Englberger, 2011 [65] | Micronesia, Pohnpei | Shared Leadership | Western: education and media campaigns | Obesity | Healthy Eating | Not specified |

| Fanian, 2015 [66] | Canada, First Nations (Behchokὸ, Northwest Territories) | Shared Leadership | Indigenous: developed their own framework | Mental Health | Empowerment and Resiliency: healthy minds, bodies and spirits | Advisors: design only |

| Harder, 2015 [67] | Canada, First Nations (Carrier Sekani communities) | Collaborate | Adaptation: both interpretive phenomenology and decolonising and critical Indigenous methodologies | Mental Health | Mixed: traditional food gathering, language, survival techniques, clan affiliation, the bah’lats system; connection to Elders, opinion of self, reducing alcohol and drugs | Advisors: design and participative implementation |

| Hibbert, 2018 [68] | Canada, Métis (Alberta) | Collaborate | Adaptation: Donnon and Hammond’s Youth Resiliency: Assessing Developmental Strengths Questionnaire (YR:ADS) | Mental Health | Life skills and Resiliency: self-esteem, communication, neighbourliness, kinship, grief and loss, and hopes and dreams | Advisors: design only |

| Ing, 2018 [69] | USA, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders (NHOPI) (Hawaii’) | Collaborate | Adaptation: behavioural change principles from Social Cognitive Theory and motivational interviewing, adapted for Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islanders | Diabetes | Mixed: healthy eating, physical activity, weight loss, self-efficacy, social support, locus of weight control | Not specified |

| Janssen, 2014 [51] | New Zealand, Māori | Collaborate | Indigenous: Kaupapa Māori | Diabetes | Mixed: healthy eating and physical activity | Participants |

| Jeffries-Stokes, 2015 [70] | Australia | Shared Leadership | Indigenous: Indigenous methods through community consultation, but not specified | Diabetes | Mixed: community arts for knowledge, capacity building, stress | Advisors: design only |

| Kaholokula, 2012 [71] | USA, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders (Hawaii’) | Collaborate | Adaptation: The Diabetes Prevention Program, adapted for Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders | Diabetes | Mixed: weight loss, healthy eating, physical activity, stress control | Not specified |

| Kaholokula, 2014 [72] | USA, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders (Hawaii’) | Collaborate | Adaptation: The Diabetes Prevention Program, adapted for Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders | Diabetes | Mixed: weight loss, healthy eating, physical activity, stress control | Not specified |

| Kakekagumick, 2013 [73] | Canada, First Nations (Sandy Lake, Ontario) | Shared Leadership | Adaptation: modifications to a curriculum already developed by Kahnawake Mohawk community in Quebec | Diabetes | Mixed: healthy eating and physical activity (includes school curriculum) | Advisors: design only |

| Kaufer, 2010 [74] | Micronesia, Pohnpei | Shared Leadership | Western: 24hour recalls and food frequency questionnaires | Chronic disease | Healthy Eating | Not specified |

| Kolahdooz, 2014 [75] | Canada, Inuit and Inuvialuit (Kitikmeot region in Nunavut and Beaufort Delta region in the Northwest Territories) | Collaborate | Western: food frequency questionnaires | Chronic disease | Healthy Eating | Advisors: design only |

| Mau, 2010 [76] | USA, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders (Hawaii’) | Collaborate | Adaptation: social action theory of behaviour change | Diabetes | Mixed: physical activity, healthy eating, weight loss | Advisors: design only |

| McShane, 2013 [77] | Canada, Inuit | Collaborate | Adaptation: CD-Rom developed with an Inuk Elder in Inuktitut and in collaboration with a Tungasuvvingat Inuit Family Health Team using oral and visual media to match Inuit learning styles | Chronic disease | Pregnancy and family health | Advisors: design and delivery |

| Mead, 2013 [78] | Canada, Inuit and Inuvialuit | Collaborate | Western: Social Cognitive Theory and Social Ecological Models | Chronic disease | Mixed: healthy eating, physical activity. | Not specified |

| Mendenhall, 2010 [79] | USA, American Indians (Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota) | Shared Leadership | Western: designed purposefully as a CBPR method for medical and mental health professionals | Diabetes | Mixed: Healthy eating, healthy weight, wellness. | Advisors: design and delivery |

| Mia, 2017 [50] | Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Queensland) | Collaborate | Indigenous: Social and emotional wellbeing conceptual framework | Mental Health | Empowerment and Resiliency | Participants |

| Micikas, 2015 [80] | Guatemala, Mayan (San Juan and San Pablo La Laguna, Sololá) | Shared Leadership | Western: Stages of Change Theory and Health Belief Model | Diabetes | Mixed: physical activity and social support | Not specified |

| Mills, 2017 [81] | Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (South-east Queensland) | Collaborate | Indigenous: designed own framework underpinned by conceptual framework based on the principle of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community control | Cardiovascular Disease | Physical activity | Not specified |

| Murdoch-Flowers, 2019 [14] | Canada, First Nations-Kanien’keha:ka (Mohawk), Montreal | Shared Leadership | Indigenous: designed own by a lay health worker from Kahnawake who designed interventions to address health holistically from a Haudenosaunee perspective | Diabetes | Mixed: physical activity, healthy eating, wellbeing. | Advisors: design only |

| Nagel, 2009 [82] | Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Top End of the North Territory) | Collaborate | Adaptation: framework not specified, but states culturally adapted | Mental Health | Mixed: well-being, life skills, stress, family support, substance dependence, self-management | Not specified |

| Pakseresht, 2015 [83] | Canada, Inuit and Inuvialuit | Collaborate | Western: food frequency questionnaires | Chronic disease | Healthy Eating | Not specified |

| Payne, 2013 [52] | Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders-Nywaigi (Queensland) | Shared Leadership | Indigenous: unclear, self-management by participants themselves | Diabetes | Mixed: Self-management, knowledge, health, change, mental health | Participants |

| Rolleston, 2017 [84] | New Zealand, Māori | Collaborate | Indigenous: Kaupapa Māori | Cardiovascular Disease | Mixed: healthy eating, physical activity, QOL, stress management | Not specified |

| Seear, 2019 [85] | Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Derby) | Collaborate | Adaptation: a locally adapted community-led diabetes prevention program | Diabetes | Mixed: healthy eating, physical activity, stress | Not specified |

| Sinclair, 2013 [86] | USA, Native Hawaiian and Pacific People (Hawaii’) | Collaborate | Adaptation: Social Cognitive Theory; The Partners in Care curriculum (originally designed and evaluated with African Americans and Latinxs was adapted for this intervention | Diabetes | Mixed: diabetes self-care (meds, glucose, healthy eating, physical activity, foot checks, smoking) | Not specified |

| Smylie, 2018 [87] | Canada, Indigenous (Brantford and Hamilton, Ontario) | Collaborate | Western: International Assessment of Literacy Skills Scores | Cardiovascular Disease | Health literacy | Not specified |

| Stewart, 2015 [88] | Canada, First Nations and Métis (Alberta, Manitoba-Dakota Tipi tribe, Nova Scotia-Mi’kmaq) | Collaborate | Adaptation: unclear, but used Indigenous ceremonies and activities | Asthma | Mixed: asthma education; traditional medicine, support | Advisors: design and delivery |

| Teufel-Shone, 2014 [89] | USA, Hualapai Indian Community (Arizona) | Shared Leadership | Adaptation: not specified but indicated use of measures that would be appreciate by tribal and research communities and locally acceptable | Diabetes | Physical activity (school-based) | Not specified |

| Tomayko, 2016 [90] | USA, American Indians (Wisconsin) | Shared Leadership | Indigenous: AI model of Elders teaching life-skills to younger generation and reinforce cultural values of family and traditional food and activity | Obesity | Mixed: healthy eating, physical activity | Advisors: design only |

| Tomayko, 2019 [91] | USA, American Indians (Wisconsin) | Collaborate | Indigenous: AI model of Elders teaching life-skills to younger generation and reinforce cultural values of family and traditional food and activity | Obesity | Mixed: healthy eating, physical activity, stress, sleep | Advisors: design only |

| Townsend, 2016 [92] | USA, Native Hawaiians, other Pacific Islanders or Filipinos (Hawaii’) | Collaborate | Adaptation: Social Cognitive Theory with adaptations based on a community needs assessment | Diabetes | Mixed: weight loss, healthy eating, physical activity, stress control | Not specified |

| Tracey, 2013 [93] | Australia, Aboriginal (Goldfields region of Western Australia) | Collaborate | Western: used a framework developed by the Western Australia Renal Disease Health Network | Renal Care | Mixed: medication management, healthy eating | Advisors: design and delivery |

| Wakani, 2013 [94] | Canada, First Nations (Algonquin of Rapid Lake) | Shared Leadership | Indigenous: Turton’s health world view framework | Diabetes | Mixed: diabetes management | Advisors: design only |

| Ziabakhsh, 2016 [53] | Canada, First Nations (Coast Salish, Haida, and Cree) | Collaborate | Indigenous: informed by Indigenous healing perspectives, transcultural nursing, and feminist theories of health and illness | Cardiovascular Disease | Quality of Life | Participants |

Geographical location and ethnicity

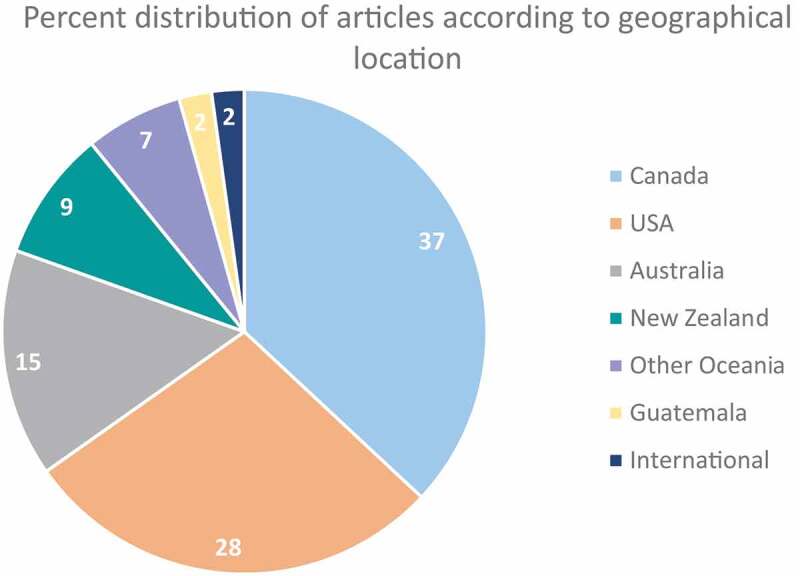

The majority of included articles were from Canada [17] and the USA [13], followed by smaller numbers from Australia [7], New Zealand [4], Other Oceania [3], Guatemala [1], and one that was an international partnership between Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Out of the studies conducted in Canada, six included solely First Nations participants while five were conducted with Inuit, three were with First Nations and Métis (combined) while only one article focused solely on Métis peoples (Figure 2). Two articles did not specify which Indigenous groups they included, but rather referred to Indigenous peoples as a whole.

Figure 2.

Canadian article distribution by Indigenous groups

Level of community engagement and framework

All included articles either fell into the Collaborate [32] or Shared Leadership [14] categories on the Community Engagement Continuum. There were another 36 articles that fell into the Consult category and 43 in the Involve category. Although all articles that engaged communities on some level had to be reviewed in detail to classify them along the Community Engagement Continuum, ultimately, the Consult and Involve categories did not meet our criteria for CBPAR. Even though all included articles [46] engaged Indigenous peoples at the two highest levels of the Community Engagement Continuum (Collaborate and Shared Leadership), 12 used Western-based methods in designing and informing the intervention while an additional 19 articles described Indigenous cultural adaptations to pre-existing Western-designed interventions. Only 15 articles applied Indigenous theories and frameworks in the design of their intervention. It is important to note that categorising articles according to different intervention levels (such as at the government versus community versus school levels) was not a focus of this paper and goes beyond the scope of this review.

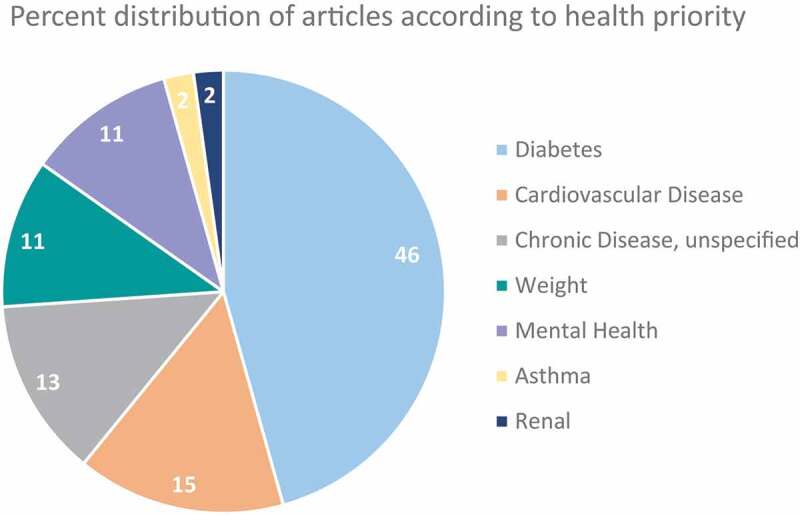

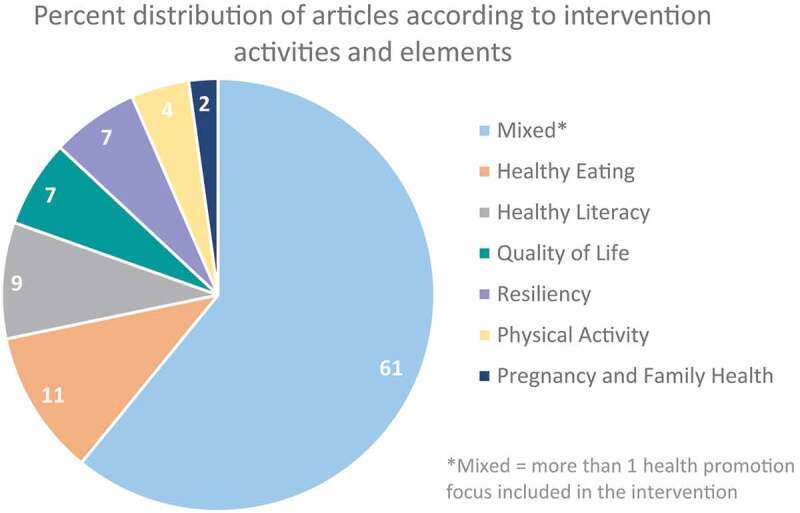

Health priority and intervention focus

We categorised interventions according to the health priorities that were the rationale and drivers of the health promoting projects (Figures 3–4). We found diabetes to be the health priority for 21 studies while seven focused on cardiovascular diseases, six on chronic disease prevention in general, and five prioritised mental health (Figure 3). There was also one intervention each targeting asthma and renal care (Figure 3). We also categorised the various intervention activities and elements that highlighted the main focus of each intervention being implemented (Figure 4). For example, five interventions focused on health eating, four on health literacy, three each on quality of life and resiliency, two on physical activity, and one on pregnancy/family health. The large majority of interventions [28] combined a mixture of more than 1 activity/element such that physical activity and healthy eating, for example, were integrated throughout an intervention. There were seven articles that highlighted interventions that integrated four health promoting elements (quality of life, resiliency, life skills, empowerment). These seven articles that describing a wholistic approach to intervention design and implementation were all informed by Indigenous worldview, or an Indigenous adaptation of a Western intervention design.

Figure 3.

Article distribution by health priority

Figure 4.

Article distribution by study intervention activities and elements

Intergenerational

Considering the important role Elders play in Indigenous cultures, it was surprising to see that 22 articles made no mention of engaging OIA and/or Elders in the intervention process. We found that 11 articles described engaging Elders in the design/development of the health promoting program. In addition, one intervention engaged Elders solely in the delivery of the program and another seven engaged Elders in both the design and delivery. Articles reporting interventions that engaged Elders as advisors in the design and/or delivery of programs provided very few details on their involvement. Only one intervention engaged Elders as both advisors and active participants in an active on-the-land initiative. There were only four articles (Mia, Janssen, Payne, Ziabakhsh) that indicated the purposeful inclusion of Elders as active participants [50–53]. Although the study by Janssen (2014) did not mention Elders specifically, it was intergenerational in nature as it discussed the incorporation of Māori cultural values by encouraging participants to walk with their grandchildren [51]. Although we cannot ignore the possibility that some studies may have engaged Elders and simply not reported it. However, we would argue that due to the esteemed role of Elders in these communities that had they been engaged, their important roles/involvement would have been reported. All four articles that included Elders as active participants also used Indigenous approaches when designing and informing the intervention as opposed to Western or adaptations of Western frameworks.

Appendix I-Sample search strategy from OVID medline

chronic disease/ or multiple chronic conditions/ or noncommunicable diseases/

obesity/ or obesity, abdominal/ or obesity, morbid/ or paediatric obesity/

hypertension/

cardiovascular diseases/ or heart diseases/ or arrhythmias, cardiac/ or tachycardia/ or cardiomyopathies/ or diabetic cardiomyopathies/ or heart arrest/ or heart failure/ or myocardial ischemia/ or coronary disease/ or vascular diseases/

kidney diseases/ or “chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder”/ or diabetic nephropathies/ or renal insufficiency/ or kidney failure, chronic/