Abstract

Introduction:

Baccalaureate nursing students develop cultural competence through curricula of theories and frameworks which evolve to reflect new knowledge, but their synthesis and impact upon health quality outcomes is not known.

Methods:

A cross-platform literature review was conducted to identify innovation and use of cultural competency theories and frameworks in nursing. Optimal literature included a formal theory, pedagogy, measures, and outcomes, which were then classified and evaluated. Additional perspectives and interventions were reviewed for potential influence on curricula and impact through the lens of integrative review.

Results:

A shift in theory from essentialism to constructivism has occurred in undergraduate curricula. Challenges to measuring outcomes have been noted. All studies reported positive outcomes but suffer from self-selection, unvalidated instruments, and little to no longitudinal data.

Conclusions:

Nursing students are exposed to culturally competent care via several validated and canonical frameworks, but self-efficacy and long-term impact have not been assessed.

Keywords: Nursing, Nursing baccalaureate curricula, Nursing cultural competence, Cultural competence framework, Cultural competence conceptual model, Cultural competence theory, Cultural competence evolution, United States nursing curricula, Cultural awareness in nursing students, Cultural sensitivity in nursing students

1. Introduction

1.1. History

The Nursing Code of Ethics[1] emphasizes the “inherent dignity, worth and unique attributes” of every person, the protection of human rights, and the reduction of health disparities. Pre-licensure education is critical in preparing the nursing workforce to uphold this code. Accordingly, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing developed a framework for addressing cultural competence in nursing baccalaureate studies, designed to combat disparities in health and health car. Meeting the Standards of Practice for Culturally Competent Nursing Care has become an accreditation requirement.[2] This position paper stipulated using “integrative learning strategies,” but did not propose or endorse particular models or theories. Nursing theories and the concepts, relationships, and assumptions or propositions derived from nursing models are necessary to purposefully explain, predict, or describe a phenomenon such as cultural competence.[3]

1.2. Exploring the underpinnings of culturally competent care

Beginning with Madeleine Leininger in the 1960s, nursing theorists have recognized that a patient’s experience of care is subjective and individual. It is influenced, among other things, by his or her cultural background.[4] Over the course of more than fifty years, however, Dr. Leininger’s Sunrise Model has been joined by additional models and pedagogical frameworks by which nurse educators hope to instill a sense of awareness and empathy in nursing students. Several models have withstood the test of time with few modifications, whereas new developments in behavioral science have informed and reinvented others.[5] The goal remains: to provide care that is culturally competent—that is, care which is aligned with cultural beliefs, is aware of historical animus, and is sensitive to stigmatized groups or communities.

1.3. Shifting demographics

A 2017 report from the United States Census Bureau estimated that 13.2% of the population was born outside the U.S., and 21.1% speak a language other than English at home. The same data predicts a shift for non-Hispanic white populations from majority to minority status by 2045, with over 15% of the population comprised of foreign-born citizens.[6] The Williams Institute at UCLA estimates the LGBTQ population at 4.5% of the United States population, with a mean age younger than the national average. This indicates a growing momentum in acknowledging additional categories of sexual orientation and gender identity.[7]

1.4. Composition of nursing population

The current Registered Nurse (RN) workforce, the nurse faculty population, and the pre-licensure nursing student population do not reflect the country’s changing demographics, as the majority continue to be white, non-Hispanic female.[8] While more newly licensed nurses are increasingly non-white, diversity remains lacking in the workforce. More than ever, nursing practice, education, and research must demonstrate empathic, responsive, patient-centered care.

1.5. Defining diversity and cultural competence

In addition to ethnicity and national origin, the American Academy of Nursing defines diversity in terms of “ability/disability, social and economic status or class, education, occupation, religious orientation, marital or parental status, gender orientation, and other related attributes of groups of people in society.[9]” Culturally competent nursing care integrates cultural values and beliefs of diverse individuals, families, groups, communities, and global society.

Corey et al categorize care delivery and influences on its quality by the 1) individual level (knowledge, skills, values, attitudes and behaviors of the individual clinician); 2) service level of an organization (vision statements and operational policies); and 3) system level (how care delivery respects the larger community).[10]

1.5.1. Individual level outcomes

At the individual level, cultural competence improves communication between providers and patients, families, and communities, which is also associated with improved care outcomes and patient satisfaction.[11] Medication adherence is improved when healthcare providers understand the cultural importance of complementary and alternative medicine traditions.[12] Behavior and lifestyle changes impacting chronic diseases are more likely to be adopted when traditional foods and activities are considered and accommodated by providers.[13]

1.5.2. Service level outcomes

At the service level of an organization, culturally competent care may decrease the risk of litigation and promote cost containment as well as ensure regulatory compliance.[14] For example, the Joint Commission requires that organizations integrate culturally competent practices in their assessments, dietary practices, staff education and language services.[15]

1.5.3. System level outcomes

At the system level of care, community education programs which considered the values and traditions of a community regarding preventive health measures (such as mammograms, cancer screenings, diabetes screening and prevention, and hypertension screening) had more positive outcomes in areas of patient participation, appointment attendance, and communication with all members of the community. Programs which bring along providers, such as community health workers and mobile clinics, show improvements in self-efficacy, self-management, and health.[13]

Outcomes of culturally competent care are expected to include the reduction of health disparities through earlier access and treatment which respects patient preferences, and improved adherence through patient engagement in decision-making.[16] Conversely, groups of people for whom access to health care that is perceived as incompatible with cultural norms may have adverse outcomes. Minority groups experience greater rates of morbidity and mortality. It is understood this is due in large part to differences of access, quality of available service, and provider prejudice.[17] However, even when research has adjusted for confounding factors such as access to care, type of care, comorbidities, severity, and prevalence, studies reflect that racial and ethnic differences in care still exist.[17] It is impossible to ignore the consequences of care delivered inappropriately to minority populations.

In recognition of these concerns, the impact of pedagogical frameworks and methods of imparting cultural competence to nursing students deserves critical scrutiny.

1.6. Problem formulation

Thus, the question: how are nursing students exposed to cultural competence in their formal education? That is to say: which theories, models, and frameworks are used, and how does the exposure to cultural competence in the curricula impact their self-awareness and eventual practices? Further, are there any measures in use to examine the longitudinal impact of the education? Table 1 demonstrates the evolution of the review.

Table 1.

Developing the research statement: what problem was being addressed through the intervention, and what was the sought outcome?

| Problem | Developing cultural awareness and sensitivity within undergraduate nursing students |

| Intervention | Education of undergraduate nursing students |

| Outcome | Ideal versus real: improved quality of care, improved patient and nurse outcomes |

To that end, this review proposes to:

Identify the current state of the science in the use of theories, models, and frameworks of cultural competence currently used in nursing education,

Identify outcomes of the exposure to cultural competence education and determine the merits and strengths of programs thereby, and

Identify gaps in the knowledge base, including a lack of standardized reporting measures, a lack of program evaluation, a need for longitudinal study to follow graduates into their professional settings, and the challenges posed to educators.

2. Methods

This study used an integrative review methodology, including a literature review and analysis, to identify the utilization of theories and frameworks of cultural competence in undergraduate nursing curricula, and its impact upon nurse and patient outcomes. A literature search was completed using CINAHL, PubMed, GoogleScholar, and other EBSCO databases. An initial pass using the search phrase “cultural competence models in nursing” generated 163 records; an expanded query was required.

Between November 2018 and January 2019, searches were performed through CINAHL, EbscoHost, and PubMed. The key words included the following and their various configurations: cultural competence, cultural awareness, cultural competency, cultural competence, cultural sensitivity, cultural humility, nursing education, curriculum, and pedagogy. Limiters included that all manuscripts must be peer reviewed, written in English, and published within the period of 2010-2019. In order to capture the greatest number of records, different search strings were used (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Strings and results for searches

| November 2018 EbscoHost | (cultural competence OR cultural awareness OR cultural competency OR cultural sensitivity) AND (nursing education); 2010-2018 Full text, academic journals, USA, English | 150 records returned |

| January 2019 CINAHL | (cultural awareness OR cultural competency OR cultural sensitivity OR cultural humility OR cultural competence) AND (nursing education) AND (curriculum) AND (undergraduate) Full text, references available, year 2010-2018 Peer reviewed, USA, English |

3 records returned |

| (cultural awareness OR cultural competency OR cultural sensitivity OR cultural humility OR cultural competence) AND (nursing education) AND (curriculum) removed (undergraduate) Full text, references available, year 2010-2018 Peer reviewed, USA, English |

20 records returned | |

| (cultural awareness OR cultural competency OR cultural sensitivity OR cultural humility OR cultural competence) AND (nursing education) AND (pedagogy) Full text, references available, year 2010-2018 Peer reviewed, USA, English |

2 records returned | |

| (cultural awareness OR cultural competency OR cultural sensitivity OR cultural humility OR cultural competence) AND (nursing education) (removed pedagogy) Full text, references available, year 2010-2018 Peer reviewed, USA, English |

83 records returned | |

| Pubmed | (cultural awareness OR cultural competency OR cultural sensitivity OR cultural humility OR cultural competence) AND (nursing education) Full text, ten years |

158 records returned, 154 duplicates |

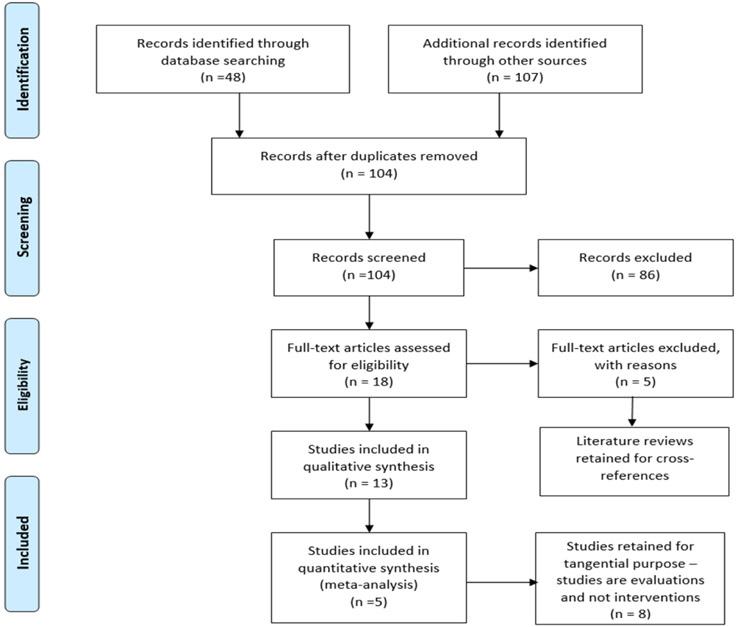

All records were then evaluated using PRISMA screening (see Figure 1). To qualify, a paper was required to inform undergraduate nursing education with curricula interventions or evaluations within the last ten years. From there, a hand search was conducted to identify studies which measured pre-and post- self-efficacy with validated instruments. Once studies were identified, they were evaluated against the research question: how are nursing students exposed to cultural competence education, how is the result of exposure measured, and optimally – how will this impact the way they treat patients and the members of their patients’ circle of care?

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram of combined records search

3. Results

Table 2 provides a chronology of searches performed, with the variety of search strings used to comprehensively seek out studies and how the strings were modified with each iteration. The final search returned 154 duplicate records out of 158 records, indicating a comprehensive mining of the literature.

The records were then audited for adherence to the stated criteria – a cohort of undergraduate nursing students in the United States, a study versus an editorial, commentary, or report, and a formal framework or pedagogy. Additionally, studies of the same population authored by a member of the investigation team were rejected if a study by the principal investigator was included (represented in Table 3 by “Duplicates Found”).

Table 3.

Disposition of records

| Total records retained | 155 | |

| Duplicate authors found | −51 | |

| Excluded | −50 | (not USA, op ed, textbook, study abroad) |

| Disqualified | −36 | (not a study, not undergrad) |

| Total Assessed | 18 | |

| Literature reviews | −5 | Retained for reference and cross-check |

| Intervention | 5 | |

| Evaluation | 8 |

Of the records examined, 18 were retained for assessment (Table 4 identifies methodology and level of evidence[18]).

Table 4.

Levels of evidence

| Reviews of cohort studies | Level V | 5 |

| Cohort studies | Level VI | 12 |

| Research/Best Practices | Level VII | 1 |

There were no randomized controlled trials, nor cohort studies that examined the impact of cultural competence pedagogy post-graduation; one study did measure the difference between first and second-year students’ TSET scores[19] but the others took place over a single year or class interval.

From the cohort studies, three primary models or frameworks were identified (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Frameworks or models identified in cohort studies

| Model or Framework | Instrument | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Jeffreys’ Cultural Competence & Confidence Model | TSET | 3 |

| Campinha-Bacote | IAPCC | 3 |

| Sunrise Model | 1 | |

| Custom | varied | 3 |

4. Analysis

4.1. Frameworks and theories

In the studies evaluated, three frameworks were dominant – Leininger’s Sunrise Model,[20] Campinha-Bacote’s body of work,[21-24] and Jeffreys’ Cultural Competency and Confidence model.[19,25,26]

4.2. Data collection and evaluation

Data collection, instrument validation, and outcomes analysis remain inconsistent between studies. Statistical analyses primarily define association between an intervention and a student’s self-reported improved cultural awareness (see Table 4).

There exist no longitudinal studies which follow baccalaureate nurses from NCLEX to career; should they exist, the problem of determining how to avoid bias in measuring cultural competence remains. Current studies rely on the measurement of self-efficacy through a variety of instruments measuring students’ responses against a scale, which may not be validated for every population group,[27,28] which may rely on self-selected participants,[20,24,29,30] and which may (as the authors note) produce results that are an artifact of knowing what answers are sought to demonstrate competence.[22]

4.3. Interpretation

This integrative review began in a previous incarnation as an examination of the theories, models, and frameworks currently used in pedagogy to bring cultural competence education to the baccalaureate nursing program, with the expectation of finding a sufficient quantity of pre- and post-intervention longitudinal studies to develop statistical significance in favor of particular theories, models, and frameworks. This was not the case. The studies examined ran the gamut between:

descriptions of traditional models still in use

proposals of new models and/or frameworks based on adaptations of existing theory

proposed curricula changes to include emerging models

onsite or professional programs for practitioners already in the field

validation of self-efficacy survey instruments, and

pre/post-intervention studies which provided data on the immediate result of the intervention selected (as documented in Table 6, which is included before the references).

Table 6.

Pre-post studies with instruments and outcomes.

| Lead name | Date | Instrument | Pre/ post |

Stat Analysis | Intervention Description | Model/Framework | Notes about results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtis | 2010 | focus group interviews | y | confluent-centered pilot curriculum | self-reported improvement | ||

| Halter | 2015 | TSET | y | univariate analysis with t test | curriculum evaluation | Jeffreys' CCC | |

| Jeffreys | 2012 | TSET | y | ANOVA/ANCOVA | Novice students vs 2nd+ years in CC curriculum | Jeffreys' CCC | |

| Kamau-Small | 2015 | surveys + clinical application report (CAR) | y | qualitative | educational theater wkshop | Stages of Change | Self-reported improvement |

| Kardong-Edgren | 2010 | IAPCC-RA | post | ANOVA + univariate | multi-curricula evaluation | Campinha-Bacote | No curriculum appears superior for teaching cultural content. |

| Mayo | 2014 | unique survey designed for population | post | multivariate regression | multi-curricula evaluation | N/A | |

| Riley | 2012 | IAPCC-R | ANOVA | Comparison of age and experience | Campinha-Bacote | ||

| Riner | 2013 | no formal instrument used | y | community health nursing practicum course | GENE framework - Sunrise Model | Self-selected | |

| Sanner | 2010 | ODCS (Pascarella) | y | Univariate + Wilcoxin signed-ranks | Annual Cultural Diversity Forum plus small group | ||

| Shattell | 2013 | TSET, BICCC | Content analysis | cross-sectional evaluation of curriculum | Jeffreys' CCC | demanding curriculum and time constraints inhibit education | |

| Strong | 2015 | ATLG Scale modified | y | Paired sample t-tests | four hourlong seminars | Custom | |

| Dunagan | 2014 | PCE Questionnaire (designed by author), ICCNE, GRISMS | multiple linear regression | multi-curricula online survey | N/A |

During this review, trends in paradigm shift were identified. The earliest literature on cultural competence recommended a familiarization with static traditions based on race and geographic culture, defined as an “essentialist” perspective.[31] A transition to more modern theories of pedagogy espouses interpersonal constructivism within ecological frameworks, as represented by the frameworks defined in Table 4.

More recent views from social work and LGBT studies are encouragingly included in pilot programs to expand awareness of cultural diversity beyond ethnicity.[28,30,32,33] An exciting new category of study – the multi-curricula evaluation[22,27,34] – has begun to surface, providing a body of transnational data from diverse geography and environment.

Further challenges to the categorization of effective cultural competence pedagogy stem from the evolution of defining cultural competence. As noted previously, culture is no longer viewed as a static construct based on geographic history and gender place, but a dynamic and fluid identity affected by acculturation, power relations, and broader context.[35] Therefore, defining cultural competence is akin to chasing a moving target; the chasing is performed by researchers and educators evaluating the fit of various paradigms in order to reject, expand, or modify nursing education to provide “care that is sensitive to issues related to culture, race, gender, and sexual orientation”.[36]

Thus upon reflection (and peer review), the question originally asked by the author was wrong: it is not the superiority of a given theory or framework currently informing cultural competence education that is important – it is whether or not the efforts of researchers, educators, and mentors provide nursing students with a real sense of the importance of cultural awareness, with which they tend to their patients and the circles of care surrounding them.

4.4. Limitations of the research

Literature reviews by Shen (2015) and Truong et al. (2014) note that there are several limitations to studying the uptake and impact of cultural competency training in nurses.[37,38] First, Shen makes a distinction between theoretical and methodological models of cultural competence, with the former including domains of sensitivity, knowledge, and skills and the latter including domains of biology, sociology, environment, and temporality. There is, at present, no way to quantify the superiority of either type of model.

Secondly, there are challenges to data collection. Shen notes a dearth of psychometrically valid instruments to measure pre- and post-intervention outcomes, and of the validated designs, none have recorded patient outcomes. Truong et al performed a “review of reviews” of studies pertaining to the entire health care workforce, and in models where patient outcomes could be recorded, there were challenges to specificity, permanence of effect, and dose-response. However, the study notes that “multicultural education interventions that were explicitly based on theory and research yielded outcomes nearly twice as beneficial as those that were not.” Finally, there is no currently known study that has captured self-efficacy reporting from nurses at the beginning of their careers post-intervention and after an interval in a professional setting. Without an assessment of continued cultural competence, it is impossible to determine whether patient outcomes in culturally vulnerable groups have been impacted by the interventions of revised nursing curricula, worksite training, or immersive experience.

5. Discussion

5.1. Dynamic curricula

The theoretical underpinnings that guide pedagogical approaches to promoting cultural competence in baccalaureate nursing programs are in constant flux, as curricula are reviewed, and educators seek to improve their delivery. Multiple theories and models have been utilized; heterogeneity in conceptualization, design, and measurement makes it difficult to evaluate and prioritize their use. Results do suggest that nursing students are engaged in learning activities that promote culturally competent care. Additionally, cultural competence training of practicing clinicians has received increased attention in the clinical setting.[39] However, it is not clear how these activities shape future clinical practice and patient outcomes.

5.2. Challenges

Nurses have a long-standing tradition of caring for underserved and vulnerable populations; however, health care disparities still exist for patients, families, and for communities.[40] Lack of consistent and psychometrically sound measurement is a readily-apparent challenge in developing and evaluating culturally competent care. Participatory research that engages patients, families, and community stakeholders in the development of conceptually sound assessment tools is needed.

5.3. Opportunities

Measures derived from conceptual models that can be operationalized in quantitative research will advance the science of cultural competence. The metrics can also be used by organizations to evaluate the delivery of culturally competent care. Drevdahl recommends that new theoretical approaches emphasizing social determinants of health, fundamental causes theory, ecological theories, and the health impact pyramid be more fully utilized in nursing.[41]

The engagement of relevant stakeholders in mixed methodological studies is also necessary to develop clinical strategies and programs that reflect cultural fluency and competence across a variety of settings.[42-44]

But perhaps most importantly, it would behoove educational institutions to solicit longitudinal participation in self-assessment studies, in order to determine whether the cultural competence informed by education can be sustained in a career setting; whether employers are invested in continuing cultural awareness training, and how to improve education for the generations of nurses to come.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This review was funded in part by the National Institute of Aging (NIA), Grant: R01AG054425. The contents of the article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH/NIA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].American Nurses Association: Ethics and Human Rights Statement. 2015; 1. [Google Scholar]

- [2].AACN. Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice [Internet]. 2008. [cited 2019 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Education-Resources/AACN-Essentials [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dickson VV, Wright F. Nursing Theorists and Their Work (7th ed.) by Alligood MR and Tomey AM (Eds.) (Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier, 2010). Nurs Sci Q. 2012 April 1; 25(2): 203–4. 10.1177/0894318412437963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].de Melo LP. The Sunrise Model: a Contribution to the Teaching of Nursing Consultation in Collective Health. American Journal of Nursing Research. 2013. January 23; 1(1): 20–3. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Canales MK, Bowers BJ. Expanding conceptualizations of culturally competent care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001. October; 36(1): 102–11. PMid:11555054 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01947.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].U.S. Census Bureau. 2017. National Population Projections Tables [Internet]. 2017 Population Projections. [cited 2018 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html [Google Scholar]

- [7].LGBT Data & Demographics – The Williams Institute; [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 17]. Available from: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-stats/?topic=LGBT#density [Google Scholar]

- [8].National Nursing Workforce Study [Internet]. NCSBN. [cited 2018 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.ncsbn.org/workforce.htm [Google Scholar]

- [9].Giger J, Purnell L, Davidhizar RE, et al. (PDF) American Academy of Nursing Expert Panel Report. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007. May; 18(2): 95–102. PMid:17416710 10.1177/1043659606298618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Corey G, Corey MS, Corey C. AE Issues and Ethics in the Helping Professions [Internet]. Cengage;2014. [cited 2019 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.cengageasia.com/en/browse/higher_education/humanities_and_social_sciences/counseling/ethics__legal_issues/ethics__legal_issues/2018/8/30/9789814834728 [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hyun I Clinical cultural competence and the threat of ethical relativism. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2008; 17(2): 154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McQuaid EL, Landier W. Cultural Issues in Medication Adherence: Disparities and Directions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018. February; 33(2): 200–6. PMid:29204971 10.1007/s11606-017-4199-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Henderson S, Kendall E, See L. The effectiveness of culturally appropriate interventions to manage or prevent chronic disease in culturally and linguistically diverse communities: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community. 2011. May; 19(3): 225–49. PMid:21208326 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Betancourt JR. Commentary on “Current approaches to integrating elements of cultural competence in nursing education”. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007. January 2; 18: 25S–7S. 10.1177/1043659606296120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].The Joint Commission. Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient-and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals [Internet]. Oakbrook Terrace, IL; 2010. [cited 2019 Mar 19] p. 102. Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/roadmap_for_hospitals/ [Google Scholar]

- [16].Alexander R. Diversity, cultural competence and the nursing student. Imprint. 2006. March; 53(2): 43–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care [Internet]. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US);2003. [cited 2019 Aug 27]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220358/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk BM, Stillwell SB, et al. Evidence-based practice, step by step: Critical appraisal of the evidence: part III. Am J Nurs. 2010. November; 110(11): 43–51. PMid:20980899 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000390523.99066.b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jeffreys MR, Dogan E. Evaluating the Influence of Cultural Competence Education on Students’ Transcultural Self-Efficacy Perceptions. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2012. April; 23(2): 188–97. PMid:22052092 10.1177/1043659611423836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Riner ME. Globally Engaged Nursing Education with Local Immigrant Populations. Public Health Nursing. 2013. June 5;30(3): 246–53. PMid:23586769 10.1111/phn.12026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Campinha-Bacote J Cultural competence in nursing curricula: how are we doing 20 years later? Journal of Nursing Education. 2006. July; 45(7): 243–4. PMid:16863103 10.3928/01484834-20060701-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kardong-Edgren S, Cason Cl, Brennan Amw, et al. Cultural competency of graduating baccaleaureate nursing students. Nursing Education Perspectives (National League for Nursing). 2010. October 9; 31(5): 278–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Riley D, Smyer T, York N. Cultural Competence of Practicing Nurses Entering an RN-BSN Program. Nursing Education Perspectives (National League for Nursing). 2012. November; 33(6): 381–5. PMid:23346786 10.5480/1536-5026-33.6.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wilson AH, Sanner S, McAllister LE. An evaluation study of a mentoring program to increase the diversity of the nursing workforce. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2010; 17(4): 144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Halter M, Grund F, Fridline M, et al. Transcultural Self-Efficacy Perceptions of Baccalaureate Nursing Students. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2015. May; 26(3): 327–35. PMid:24841469 10.1177/1043659614526253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shattell MM, Nemitz EA, Crosson N (Pam), et al. Culturally Competent Practice in a Pre-Licensure Baccalaureate Nursing Program in the United States: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nursing Education Perspectives (National League for Nursing). 2013. November; 34(6): 383–9. PMid:24475599 10.5480/11-574.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mayo RM, Sherrill WW, Truong KD, et al. Preparing for Patient-Centered Care: Assessing Nursing Student Knowledge, Comfort, and Cultural Competence Toward the Latino Population. Journal of Nursing Education. 2014. June; 53(6): 305–12. PMid:24766083 10.3928/01484834-20140428-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Strong KL, Folse VN. Assessing Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Cultural Competence in Caring for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients. Journal of Nursing Education. 2015. January; 54(1): 45–9. PMid:25535762 10.3928/01484834-20141224-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kamau-Small S, Joyce B, Bermingham N, et al. The Impact of the Care Equity Project with Community/Public Health Nursing Students. Public Health Nursing. 2015. April 3; 32(2): 169–76. PMid:24850360 10.1111/phn.12131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sanner S, Baldwin D, Cannella KAS, et al. The impact of cultural diversity forum on students’ openness to diversity. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2010; 17(2): 56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Garneau AB, Pepin J. Cultural Competence: A Constructivist Definition. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2015. January; 26(1): 9–15. PMid:25037305 10.1177/1043659614541294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Curtis MP, Jensen A. A descriptive study of learning through confluent education: an opportunity to enhance nursing students’ caring, empathy, and presence with clients from different cultures. International Journal for Human Caring. 2010. September; 14(3): 49–53. 10.20467/1091-5710.14.3.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lim FA, Brown Jr Donald V, et al. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health: Fundamentals for Nursing Education. Journal of Nursing Education. 2013. April; 52(4): 198–203. PMid:23471873 10.3928/01484834-20130311-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dunagan PB, Kimble LP, Sweat Gunby S, et al. Attitudes of Prejudice as a Predictor of Cultural Competence Among Baccalaureate Nursing Students. Journal of Nursing Education. 2014. June; 53(6): 320–8. PMid:25033489 10.3928/01484834-20140521-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Racher FE, Annis RC. Respecting culture and honoring diversity in community practice. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal. 2007; 21(4): 255–70. PMid:18236770 10.1891/088971807782427985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].AAN Expert Panel Report. Culturally competent health care. Nurs Outlook. 1992. December; 40(6): 277–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shen Z Cultural competence models and cultural competence assessment instruments in nursing: a literature review. J Transcult Nurs. 2015. May; 26(3): 308–21. PMid:24817206 10.1177/1043659614524790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Truong M, Paradies Y, Priest N. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Services Research. 2014. March 3; 14(1): 99. PMid:24589335 10.1186/1472-6963-14-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Govere L, Govere EM. How Effective is Cultural Competence Training of Healthcare Providers on Improving Patient Satisfaction of Minority Groups? A Systematic Review of Literature. World-views Evid Based Nurs. 2016. December; 13(6): 402–10. PMid:27779817 10.1111/wvn.12176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, et al. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003. August; 118(4): 293–302. 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Drevdahl DJ. Culture Shifts: From Cultural to Structural Theorizing in Nursing. Nurs Res. 2018. April; 67(2): 146–60. PMid:29489635 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].McMillan LR. Exploring the world outside to increase the cultural competence of the educator within. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2012; 19(1): 23–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Miner S, Liebel DV, Wilde MH, et al. Using a Clinical Out-reach Project to Foster a Community-Engaged Research Partnership With Somali Families. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2017. June 6; 11(1): 53–9. PMid:28603151 10.1353/cpr.2017.0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Siegrist BC. Partnering with public health: a model for baccalaureate nursing education. Family & Community Health. 2004. October; 27(4): 316–25. PMid:15602322 10.1097/00003727-200410000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]