Abstract

Background:

Polypharmacy is associated with dyspnea in cross-sectional studies, but associations have not been determined in longitudinal analyses. Statins are commonly prescribed but their contribution to dyspnea is unknown. We determined whether polypharmacy was associated with dyspnea trajectory over time in adults with advanced illness enrolled in a statin discontinuation trial, overall, and in models stratified by statin discontinuation.

Methods:

Using data from a parallel-group unblinded pragmatic clinical trial (patients on statins ≥3 months with life expectancy of 1 month to 1 year, enrolled in the parent study between June 3, 2011, and May 2, 2013, n = 308/381 [81%]), we restricted analyses to patients with available baseline medication count and ≥1 dyspnea score. Polypharmacy was assessed by self-reported chronic medication count. Dyspnea trajectory group, our primary outcome, was determined over 24 weeks using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System.

Results:

The mean age of the patients was 73.8 years (standard deviation [SD]: ± 11.0) and the mean medication count was 11.6 (SD: ± 5.0). We identified 3 dyspnea trajectory groups: none (n = 108), mild (n = 130), and moderate–severe (n = 70). Statins were discontinued in 51.8%, 48.5%, and 42.9% of patients, respectively. In multivariable models adjusting for age, sex, diagnosis, and statin discontinuation, each additional medication was associated with 8% (odds ratio [OR] = 1.08 [1.01–1.14]) and 16% (OR = 1.16 [1.08–1.25]) increased risk for mild and moderate–severe dyspnea, respectively. In stratified models, polypharmacy was associated with dyspnea in the statin continuation group only (mild OR = 1.12 [1.01–1.24], moderate–severe OR = 1.24 [1.11–1.39]) versus statin discontinuation (mild OR = 1.03 [0.95–1.12], and moderate–severe OR = 1.09 [0.98–1.22]).

Conclusion:

Polypharmacy was strongly associated with dyspnea. Prospective interventions to decrease polypharmacy may impact dyspnea symptoms, especially for statins.

Keywords: dyspnea, polypharmacy, trajectory, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), statins

Introduction

Dyspnea is common among patients with serious, life-limiting medical conditions including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disease.1–3 One quarter of patients with advanced cancer have moderate-to-severe dyspnea during their last 6 months of life, and in one series, episodic dyspnea crises affected up to 70% of patients with cancer.4,5 Refractory dyspnea is one of the indications for palliative care referral according to the most recent heart failure guidelines.6 Among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 27% to 61% experience moderate-to-severe dyspnea.7 In addition to the distress experienced during episodes of acute or chronic dyspnea for patients living with serious medical conditions, dyspnea also exacerbates other symptoms such as pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression.8,9

Polypharmacy is defined as concurrent prescription of 5 or more chronic medications.10 In aging adults and among recently hospitalized patients, average medication count can far exceed this number.11,12 On average, older adults hospitalized during their last year of life were prescribed 24 chronic medications.13 Not all of these medications are medically appropriate and some may even contribute to harm. Up to 80% of recently hospitalized patients in their last year of life were discharged on at least one potentially inappropriate medication and one-third were on 3 or more potentially inappropriate medications.13 Notably, dyspnea prevalence increases with polypharmacy,14 and it is independently associated with polypharmacy in prior cross-sectional studies,15,16 but there are limited data regarding these associations in longitudinal studies.

The therapeutic effects of certain medications may wane with multimorbidity and frailty and may warrant reassessment of potential benefits compared with their harms. Statins are commonly prescribed for persons with cardiovascular conditions or cardiovascular risk factors. In 2011 to 2012, 23.2% of adults aged 40 years and older were prescribed statins in the United States.17 The use of statins increases with age, with prescriptions for 17.4% of individuals aged 40–59 years compared with 47.6% of individuals aged 75 years and older. Importantly, statins have been associated with muscle inflammation, aching, and pain, which may become more relevant in older persons, particularly in the setting of polypharmacy. Mouse models suggest that statins could accelerate aging-related decline in the diaphragmatic mitochondria.18,19 At least one case report in humans reported diaphragmatic paralysis leading to restrictive pulmonary disease and dyspnea from statin use but the examination of statin use and dyspnea in humans remains limited.20

Reducing polypharmacy may be one approach to relieve dyspnea. Identification of medications to prioritize for deprescribing, or deimplementing, could be an opportunity to relieve symptoms and improve patient-centered care in older individuals living with multiple chronic conditions.21,22 To address these gaps, we characterized dyspnea trajectories for adults enrolled in a randomized clinical trial of discontinuation of statin medications. We then evaluated associations between polypharmacy (medication count as a continuous variable), with and without concurrent statin use, and dyspnea trajectory group membership.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a secondary analysis of patients enrolled in a randomized clinical trial of statin discontinuation who had a self-reported chronic medication history completed (n = 372 [97.6%] of 381) between 2011 and 2013.23 In brief, this study included patients enrolled from 15 Palliative Care Research Cooperative sites and randomized to statin discontinuation or usual care. Participating institutions enrolled patients only after relevant institutional review board approval. Eligible study participants included English-speaking patients aged 18 years and older who had a life-limiting disease as determined by (1) the “surprise” question asked of their physician (“Would you be surprised if your patient died in the next year?”), (2) minimum life expectancy of at least 1 month, (3) functional decline in the previous 3 months and (4) who received a statin for primary or secondary prevention for at least 3 months prior to study enrollment. Study participants were randomized to either statin discontinuation or continuation of statin therapy after providing written informed consent for the parent trial. We report here a secondary analysis of deidentified data from this parent trial, and institutional review board approval from Yale School of Medicine was waived.

Polypharmacy

The parent study recorded nonstatin medications as (1) regularly scheduled, (2) used as needed but at least 50% of the days in the prior week, and (3) medications used less than 50% of the days the prior week and quantified medication count from these measures.23 Of note, medication count may have included over-the-counter medications, but participants were specifically asked not to include vitamins, minerals, or herbal supplements. We determined polypharmacy as a categorical and a continuous variable based on the number of patient-reported, nonstatin medications prescribed. However, because the average medication count was at least 10 at baseline, and during most of the follow-up evaluations, prior categorical cutoffs of 5 or more medications were not used.24,25 We defined 3 levels of polypharmacy: 10 to 15 chronic medications and more than 15 medications (reference category ≤9 chronic medications).

Outcome (Dyspnea Trajectories)

Our primary outcome was dyspnea trajectory group assignment. To determine trajectory groups, we used data collected from the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) item that explores dyspnea symptoms at the time of the interview. We included patients with at least 1 dyspnea measurement. Patient-reported dyspnea was gauged as 0 = no shortness of breath and 10 = worst possible shortness of breath at the time the assessment was completed. The ESAS was administered up to 8 times (enrollment and then weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24). Group-based trajectory modeling (PROC TRAJ in SAS) was used to develop dyspnea trajectories in the 24 weeks following randomization. This approach estimates each patient’s probability of membership in multiple trajectories and then assigns the patient to the trajectory with the highest probability of membership. We used a censored normal model for the dyspnea score (maximum score = 10).

As a first step, models were estimated between 2 and 6 groups with a quadratic order. The optimal number of trajectories was picked using a combination of Bayesian Information Criterion values as well as the smallest number of classes that retained >10% of the cases. We then tested orders (linear, quadratic, cubic, and quartic) to estimate the best fit based on the observed versus estimated trajectories. To define trajectories, we used semiparametric, group-based modeling as described by Jones et al.26 We evaluated trajectories to minimize variance within each group while maintaining group distinction.

Baseline Covariates

We included age, sex, obesity defined as body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, and primary diagnostic group categories as covariates. Diagnostic group categories included all cancers (combined) and pulmonary, cardiovascular, and liver/kidney conditions. All other diagnostic group categories were called “other.” For modeling purposes, we combined pulmonary and cardiovascular groups as cardiopulmonary diagnoses category and included liver/kidney into the “other” category.

Statistical Analysis

We described trajectories as the primary outcomes. Categorical variables were described using frequency distributions, and continuous variables were described using appropriate summary statistics for central tendency (mean, median) and variability. After the best trajectory model was determined, descriptive and clinical characteristics were used to describe each trajectory group. For descriptive and modeling purposes, we treated dyspnea scores as a 3-level categorical variable based on the trajectory scores. Categories were defined as no dyspnea (ESAS9 = 0), mild dyspnea (ESAS9 = 1–3), or moderate–severe (ESAS9 ≥4). We then used multinomial logistic regression to evaluate the association between polypharmacy and dyspnea trajectories overall and stratified by statin discontinuation arm of the parent study. All analyses were done in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Of the patients enrolled in the parent study, most (95%) were on at least 5 medications at study enrollment. The mean medication count was 11.6 (standard deviation ± 5.0) and did not differ with statin discontinuation. Because of the high number of medications used chronically, we categorized medication count as ≤9 (n = 141; 37.9%), 10 to 15 (n = 155; 41.7%), and >15 (n = 76; 20.4%) chronic medications. Average age was 73.8 years and was similar across medication count categories (Table 1). More than half were men in each medication count group (53.2%, 57.4%, and 56.6%, respectively), and a similar majority proportion of participants were white race, regardless of medication count category. Body mass index at baseline was similar among the groups, with the majority of patients being normal weight or overweight; 24.4% of patients were obese. Cancer-related diagnoses were most common (51.9% of all participants) and were present in 60.3% of participants on ≤9 chronic medications compared with 43.4% of those on >15 medications. Pulmonary conditions were next most frequent, affecting 12.4% of patients overall and increasing from 6.4% of participants on ≤9 medications compared with 19.7% of those on >15 medications.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants in Statin Discontinuation Study Stratified by Chronic Medication Categories.a

| Chronic Medications Categories | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤9 (n = 141) | 10–15 (n = 155) | >15(n = 76) | |

| Mean age (baseline), years (SD) | 75.0 (10.7) | 72.9 (11.6) | 73.2 (10.2) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 75 (53.2) | 89 (57.4) | 43 (56.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 111 (78.7) | 126 (81.3) | 62 (82.6) |

| Black | 21 (14.9) | 21 (13.6) | 11 (14.5) |

| Others | 9 (6.4) | 8 (5.2) | 3 (3.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25 (21–29) | 26 (23–31) | 27 (23–31) |

| Obese, n (%)b | 30 (21.3) | 40 (25.8) | 21 (27.6) |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Cancer (leukemia, malignancy) | 85 (60.3) | 75 (48.4) | 33 (43.4) |

| Pulmonary | 9 (6.4) | 22 (14.2) | 15 (19.7) |

| Cardiovascular | 8 (5.7) | 15 (9.7) | 9 (11.8) |

| Liver/kidney | 7 (5.0) | 6 (3.9) | 4 (5.3) |

| Others (include AIDS, dementia, cerebrovascular) | 32 (22.7) | 37 (23.9) | 15 (19.7) |

| Duration of statin use (years), n (%) | |||

| <1 | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (1.4) |

| 1–5 | 45 (29.4) | 45 (29.4) | 15 (20.6) |

| >5 | 95 (69.9) | 104 (68.0) | 57 (78.1) |

| Statin discontinuation, n (%) | 67 (47.5) | 80 (51.6) | 37 (48.7) |

| Dyspnea category at baseline (ESAS 9), n (%) | |||

| No dyspnea (ESAS = 0) | 60 (42.6) | 56 (36.1) | 18 (23.7) |

| Mild dyspnea (ESAS 1–3) | 17 (12.1) | 20 (12.9) | 10 (13.2) |

| Moderate–severe dyspnea (ESAS ≥4) | 32 (22.7) | 46 (29.7) | 24 (31.6) |

| Missing dyspnea | 32 (22.7) | 33 (21.3) | 24 (31.6) |

| Died within 24 weeks, n (%) | 54 (38.3) | 62 (40.0) | 27 (35.5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

n = 372; 9 patients from parent study missing medication count at baseline.

Data missing for 20 participants enrolled in parent study.

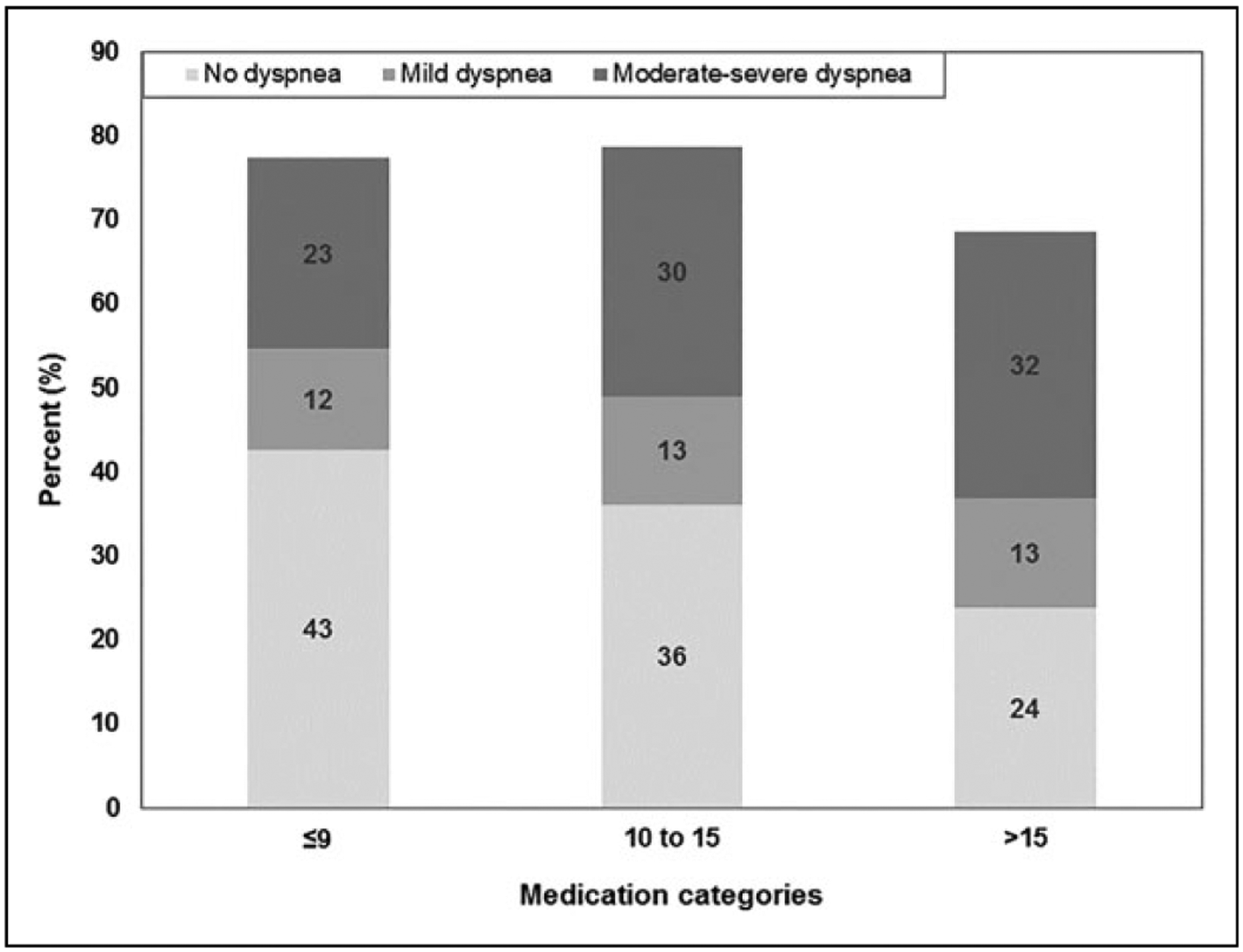

Median dyspnea score at study enrollment was 1.5 (0, 5) overall (data not otherwise shown). Dyspnea prevalence and severity at baseline increased with increased medication count (Figure 1). Among patients on ≤9 medications, 43% had no dyspnea, whereas among patients with >15 medications, 24% had no dyspnea. Moderate–severe dyspnea was reported for 23% of patients on 9 or fewer medications compared with 32% of patients on more than 15 medications.

Figure 1.

Relationship between medication count and dyspnea score (ESAS 9) at baseline (n = 283 among patients with dyspnea score and medication count at baseline). Numbers do not add up to 100% due to missing medication count and/or dyspnea. ESAS indicates Edmonton Symptom Assessment System.

Dyspnea Trajectories and Associated Outcomes

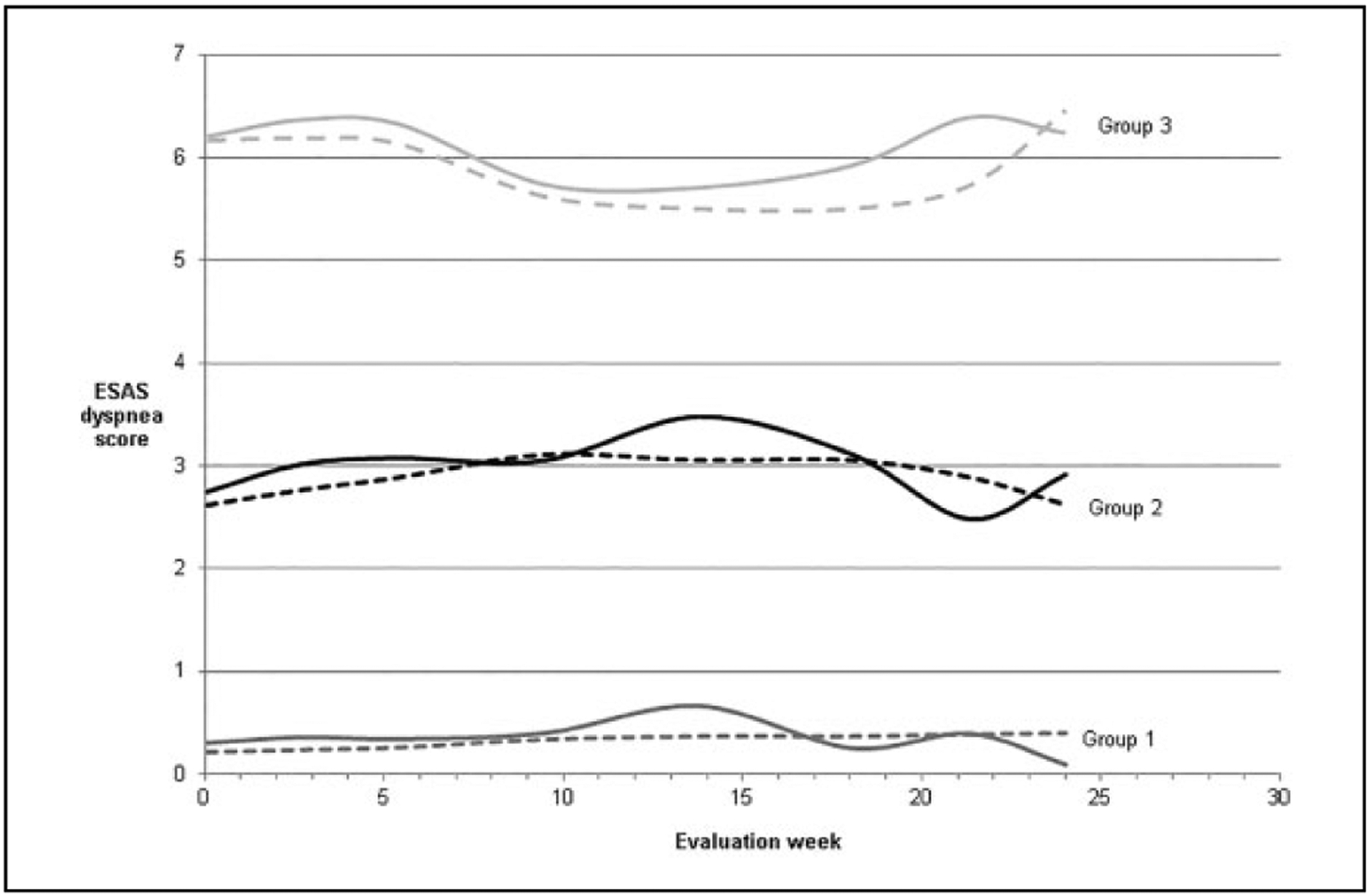

Three hundred eight participants (81% of those enrolled) completed at least 1 ESAS; only 25 (6%) participants completed all 8 ESAS surveys. We identified 3 trajectory groups: (1) no dyspnea (n = 108), (2) mild (n = 130), and (3) moderate–severe (n = 70; Table 2). Mean probability of group memberships was 84%, 72%, and 82%, respectively. Within trajectory groups, dyspnea scores remained similar throughout follow-up (eg, patients with minimal dyspnea tended to remain in that group throughout the follow-up; Figure 2). Mean age and gender were similar across the 3 trajectories. Pulmonary diagnoses increased with dyspnea group severity (1.9% of patients in group 1, 10.8% of patients in group 2, and 35.7% of patients in group 3). Among patients in group 1 (no dyspnea), 56 (51.8%) of 108 were assigned to the statin discontinuation arm of the parent study compared with 63 (48.5%) of 130 patients in group 2 (mild), and 30 (42.9%) of 70 patients in group 3 (moderate–severe dyspnea; P = .5).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients by Dyspnea Trajectory Group Membership.a

| Group 1, No Dyspnea (n = 108) |

Group 2, Mild Dyspnea (n = 130) |

Group 3, Moderate-Severe Dyspnea (n = 70) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (baseline), years (SD) | 71.5 (11.3) | 72.7 (11.1) | 72.0 (9.9) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 61 (56.5) | 72 (55.4) | 41 (58.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 82 (76.0) | 108 (83.1) | 57 (81.4) |

| Black | 21 (19.4) | 14 (10.8) | 10 (14.3) |

| Others | 5 (4,6) | 8 (6.2) | 3 (4.3) |

| BMI at baseline | |||

| Mean (SD) in kg/m2 | 27.4 (7.0) | 27.3 (7.3) | 27.7 (8.1) |

| Obese, n (%) | 28 (25.9) | 33 (25.4) | 20 (28.6) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||

| Cancer (leukemia, malignancy) | 69 (63.9) | 80 (61.5) | 33 (47.1) |

| Pulmonary | 2 (1.9) | 14 (10.8) | 25 (35.7) |

| Cardiovascular | 9 (8.3) | 10 (7.7) | 5 (7.1) |

| Liver/kidney | 9 (8.3) | 5 (3.9) | 0 |

| Others (include AIDS, dementia, cerebrovascular) | 19 (17.6) | 21 (16.2) | 7 (10.0) |

| Medication count (baseline) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 9 (6,14) | II (8, 14) | 13 (10, 16) |

| Statin discontinuation arm, n (%) | 56 (51.8) | 63 (48.5) | 30 (42.9) |

| Duration of statin use (years) | |||

| <1 | 3 (2.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.4) |

| 1–5 | 30 (28.9) | 44 (33.8) | 17 (24.3) |

| >5 | 71 (65.7) | 83 (63.8) | 52 (74.3) |

| Died within 24 weeks, n (%) | 42 (38.9) | 52 (40.0) | 29 (41.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

n = 308 With at Least One Dyspnea Score.

Figure 2.

Dyspnea score trajectories over 24 weeks among 308 participants following randomization in the Statin Discontinuation trial. Dashed lines represent predicted values and solid lines represent empirical averages.

In multivariable models adjusting for age, sex, obesity, diagnosis category, and statin discontinuation group, polypharmacy was significantly associated with dyspnea group membership. Relative to the no dyspnea group (reference, group 1), each additional medication was associated with 8% increased risk of mild dyspnea group membership (group 2; odds ratio [OR] = 1.08 [1.01–1.14]) and 16% risk for membership in the moderate–severe dyspnea group (group 3; OR = 1.16 [1.08–1.25]; Table 3). Cardiopulmonary conditions were the only other variable associated with group membership (moderate–severe dyspnea only) relative to the “other” diagnosis category group (OR for mild = 2.29 [0.92–5.74]); moderate–severe OR = 11.17 [3.58–34.87]). There was no association between obesity and dyspnea group membership. Statin discontinuation was not associated with dyspnea trajectory group membership (group 2 OR = 0.88 [0.52–1.49]; group 3 OR = 0.65 [0.33–1.26]).

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression of Medication Count and Dyspnea Trajectory Group Membership.

| Dyspnea Trajectory Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Mild Dyspnea | Moderate–Severe Dyspnea | |

| Medication count | Per 1 additional medication | 1.08 (1.01, 1.14) | 1.16 (1.08, 1.25) |

| Age (years) | Per 1 year | 1.00 (0.99, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) |

| Female sex | 1.05 (0.62, 1.79) | 0.90 (0.46, 1.76) | |

| Statin discontinuation | 0.88 (0.52, 1.49) | 0.65 (0.33, 1.26) | |

| Primary diagnosis category | Others | ||

| Cardiopulmonary | 2.29 (0.92, 5.74) | 11.17 (3.58,34.87) | |

| Cancer | 1.52 (0.77, 2.98) | 2.54 (0.92, 6.98) | |

| Obesity | 0.81 (0.43, 1.51) | 0.67 (0.30, 1.47) | |

In stratified models by statin discontinuation and adjusted for covariates, participants who continued statins had a 12% increased risk for mild dyspnea associated with each additional medication (group 2; OR = 1.12 [1.01–1.24]) and 24% increased risk for moderate–severe dyspnea (group 3 OR = 1.24 [1.11–1.39]). Among participants randomized to statin discontinuation, there was no association between medication count and dyspnea group membership (group 2 OR = 1.03 [0.95–1.12]); group 3 OR = 1.09 [0.98–1.22]).

Discussion

Dyspnea is common in multiple chronic conditions and may increase in severity toward the end of life. We showed that dyspnea trajectories can be identified among patients living with serious medical illnesses and dyspnea remained essentially unchanged over at least 6 months of observation. Increasing medication count was a strong predictor for dyspnea group membership, with dyspnea risk increasing 8% to 16% for each increase in the number of chronic medications. Given the prevalence of dyspnea and its associated impact on quality of life, identifying effective strategies to improve symptom management could relieve suffering for broad populations of patients. These results suggest that future studies examining whether deimplementation of medications may be effective to improve dyspnea in patients with serious illnesses are warranted.

Our results illustrate the relationship between increasing medication count (leading to polypharmacy with, in this population, translation to a medication count of 11 chronic medications) and dyspnea and further describe associations between polypharmacy and dyspnea in longitudinal analyses. In a prospective cohort of older patients transitioning from acute to community-based home care in Australia, dyspnea was reported in 17% of patients on less than 5 medications compared with 63% of patients on 10 or more medications.14 In a cross-sectional European study including 4000 nursing home patients from 6 different countries, dyspnea was associated with 10 or more chronic medications (referred to as “excessive polypharmacy”) by more than 2-fold compared with nonpolypharmacy patients.15,16 Similar associations were identified for European patients receiving home care, although the effect was attenuated, likely reflecting less medically complex patients who were able to receive home care compared with nursing home patients.27

These observations raise questions over whether associations between polypharmacy and dyspnea are explained by reverse causality. Patients with more severe disease and multimorbidity undoubtedly receive more complex medication regimens in efforts to control their medical problems that contribute to dyspnea.28 It is also possible that patients with more significant dyspnea are seeking symptom relief from their clinical providers who, in turn, prescribe more medications in attempts to control dyspnea. Future studies on polypharmacy and patient-centered outcomes may benefit from recruiting patients with one principal diagnosis and with similar baseline level of severity of illness and comorbidity burden. In our study, mortality was similar across medication count categories for patients included, suggesting that patients with polypharmacy were not substantially more complex than those prescribed fewer medications. Future clinical trials should more rigorously examine the directionality of polypharmacy and dyspnea.

To date, interventions to relieve dyspnea focused on pharmacologic prescriptions including corticosteroids and opioids.29–32 A pilot study including 35 patients with cancer randomized to either 7 days of dexamethasone or placebo showed that dexamethasone significantly reduced dyspnea scores by up to 2 points on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale.29 The same group also used prophylactic opioids (buccal tablets of fentanyl or nasal spray in pilot studies including approximately 20 patients each) for patients with exertion-related dyspnea. The results suggested that prophylactic opioids decreased dyspnea following exertion during a 6-minute walk test.30,31 While these interventions warrant more rigorous evaluation in larger clinical trials, there are potential hazards to adding medications to alleviate dyspnea. Increased polypharmacy, especially using corticosteroid and opioid drug classes, could contribute to worsening quality of life through adverse neuro-cognitive effects, drug interactions, and immune impairment leading to important and harmful clinical events such as pneumonia.33 As the safety of deprescribing interventions is established, next steps should explore how deimplementing other medications affects dyspnea and other physical symptoms and health-related quality of life for patients with serious life-limiting conditions. Symptom-specific approaches to improving dyspnea may be able to identify whether tailored deimplementation would improve dyspnea symptoms.

Deimplementation strategies remain in their infancy. Clinical trials testing optimal approaches to deimplement medications are needed to determine efficacy of different strategies. In a pragmatic cluster randomized noninferiority trial in the Netherlands, deimplementing antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs in low-cardiovascular risk adults was found to be safe over a 2-year follow-up period.34 In a cluster randomized trial of pharmacies in Quebec, Canada, a pharmacist-led intervention provided evidence-based brochures about deprescribing to older patients and their physicians in the outpatient setting. The intervention was associated with substantially higher rates of medication deprescribing at 6 months without increasing hospitalization rates compared with usual care.35 Given the hazards of overprescribing following a hospitalization, inpatient events are additional opportunities to review medications lists and could be important to reduce incident and increasing polypharmacy.14 Hospital-based interventions may be effective, although the quality of the evidence is still lacking, with little evidence to support any significant changes in patient-centered outcomes.36 A single-site study of deprescribing rounds prior to hospital discharge also showed significant promise in reducing medications compared with a control group without any increase in emergency department visits or hospital readmissions.37 As the clinical outcomes suggest safety for deimplementing potentially nonbeneficial medications, patient-level outcomes such as symptoms are required to further understand the potential impact of these strategies on patients’ experiences.

Reducing the harms of polypharmacy requires weighing the effectiveness of pharmacologic management for chronic medical conditions compared with the potential burden of additional medications and drug interactions. Cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation are among the strongest predictors of polypharmacy.38 Our regression models suggest similar findings, with combined cardiopulmonary diagnoses associated with an estimated 11-fold increase in odds for moderate–severe dyspnea group membership. Clusters of drug prescribing patterns for specific conditions such as cardiovascular conditions, depression–anxiety, or pulmonary conditions may be able to inform optimal approaches to deimplement medications in older adults.39 It is likely that, between the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease and their associated treatments, cardiovascular medications may be reasonable first targets for deimplementing in different populations of patients with chronic dyspnea. In addition, evaluation of dyspnea using a pulmonary-specific survey instruments and functional measures such as 6-minute walk test could give more granular assessments of dyspnea burden for these patients.

We found a nonsignificant association between statin discontinuation and dyspnea severity (52% of patients in no dyspnea group compared with 43% of patients in the moderate–severe dyspnea group). While we did not find associations between statin discontinuation and dyspnea group membership in the overall models, the stratified models suggest there may be a differential effect on dyspnea severity according to continued statin prescription. Stratified analyses were likely under-powered to detect a significant difference in stratified models but may warrant further examination. Larger observational studies may further elucidate the relationship between statin use and dyspnea severity, particularly in populations enriched with dyspnea such as patients with chronic pulmonary or cardiac diseases, especially given the high prevalence of cancer-related conditions in this study population.

Our study has several limitations. First, dyspnea measurement relied on self-reported symptoms using the ESAS, without using a pulmonary-specific symptom measurement tool. This could limit our ability to detect substantial changes in dyspnea and related symptoms in this analysis. Similarly, the number of symptom assessments diminished over time, with 73 (19%) of 381 participants not completing any symptom assessments, approximately half of patients (200/381 [52%]) completing 4 of fewer assessments, and only 25 (6%) of 381 of participants completing all 8 dyspnea assessments. In addition, study patients were relatively heterogeneous in terms of primary medical diagnosis, with the majority having cancer-related diagnoses. It is possible that polypharmacy in general and statin use, specifically, may have different effects in patients with more chronic cardiopulmonary causes of dyspnea. We also did not include prescription of other medications such as opioids and benzodiazepines that may be used to relieve dyspnea to determine their association with dyspnea severity.

Conclusion

Dyspnea trajectory group membership remains relatively stable over a 6-month follow-up of patients with serious medical conditions. Polypharmacy was associated with greater dyspnea severity. Statin discontinuation was not statistically significantly associated with dyspnea group membership in overall models, although stratified models suggest that polypharmacy has a more potent effect with ongoing statin use compared with statin discontinuation. Interventions to deimplement ineffective and/or potentially inappropriate medications for patients with serious medical conditions with and without cardiopulmonary conditions, especially among those toward end of life, should be evaluated in prospective clinical trials.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project is supported by the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group funded by National Institute of Nursing Research U24NR014637 and 1UC4NR12584-01. This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [R01 HL090342 to KC]. The PCRC (sponsor) performed subject recruitment and data collections. The sponsor was not directly involved in the design, methods, analysis, and preparation of paper.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Mercadante S, Fusco F, Caruselli A, et al. Background and episodic breathlessness in advanced cancer patients followed at home. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(1):155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weingaertner V, Scheve C, Gerdes V, et al. Breathlessness, functional status, distress, and palliative care needs over time in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or lung cancer: a cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014; 48(4):569–581, e561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon ST, Higginson IJ, Benalia H, et al. Episodes of breathlessness: types and patterns—a qualitative study exploring experiences of patients with advanced diseases. Palliat Med. 2013; 27(6):524–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seow H, Barbera L, Sutradhar R, et al. Trajectory of performance status and symptom scores for patients with cancer during the last six months of life. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1151–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercadante S, Aielli F, Adile C, et al. Epidemiology and characteristics of episodic breathlessness in advanced cancer patients: an observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadoud A, Jenkins SM, Hogg KJ. Palliative care for people with heart failure: summary of current evidence and future direction. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landis SH, Muellerova H, Mannino DM, et al. Continuing to confront COPD international patient survey: methods, COPD prevalence, and disease burden in 2012–2013. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:597–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer AE, Meeker D, Teno JM, Lynn J, Lunney JR, Lorenz KA. Factors associated with family reports of pain, dyspnea, and depression in the last year of life. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(10): 1066–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark N, Fan VS, Slatore CG, et al. Dyspnea and pain frequently co-occur among medicare managed care recipients. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(6):890–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlesworth CJ, Smit E, Lee DS, Alramadhan F, Odden MC. Polypharmacy among adults aged 65 years and older in the United States: 1988–2010. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(8): 989–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onatade R, Auyeung V, Scutt G, Fernando J. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in patients on admission and discharge from an older peoples’ unit of an acute UK hospital. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(9):729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtin D, O’Mahony D, Gallagher P. Drug consumption and futile medication prescribing in the last year of life: an observational study. Age Ageing. 2018;47(5):749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Runganga M, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Multiple medication use in older patients in post-acute transitional care: a prospective cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1453–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onder G, Liperoti R, Fialova D, et al. Polypharmacy in nursing home in Europe: results from the SHELTER study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(6):698–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vetrano DL, Tosato M, Colloca G, et al. Polypharmacy in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment: results from the SHELTER study. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Burt VL, Kit BK. Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2014; (177):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiyama S HMG CoA reductase inhibitor accelerates aging effect on diaphragm mitochondrial respiratory function in rats. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1998;46(5):923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golomb BA, Evans MA. Statin adverse effects: a review of the literature and evidence for a mitochondrial mechanism. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2008;8(6):373–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatham K, Gelder CM, Lines TA, Cahalin LP. Suspected statin-induced respiratory muscle myopathy during long-term inspira-tory muscle training in a patient with diaphragmatic paralysis. Phys Ther. 2009;89(3):257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linsky A, Meterko M, Stolzmann K, Simon SR. Supporting medication discontinuation: provider preferences for interventions to facilitate deprescribing. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson W, Lundby C, Graabaek T, et al. Tools for deprescribing in frail older persons and those with limited life expectancy: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;67(1):172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH Jr, et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George C, Verghese J. Polypharmacy and gait performance in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017; 65(9):2082–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones BLN, Jones DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29(3):374–393. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giovannini S, van der Roest HG, Carfi A, et al. Polypharmacy in home care in Europe: cross-sectional data from the IBenC study. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(2):145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Negewo NA, Gibson PG, Wark PA, Simpson JL, McDonald VM. Treatment burden, clinical outcomes, and comorbidities in COPD: an examination of the utility of medication regimen complexity index in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017; 12:2929–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui D, Kilgore K, Frisbee-Hume S, et al. Dexamethasone for dyspnea in cancer patients: a pilot double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(1):8–16, e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hui D, Kilgore K, Frisbee-Hume S, et al. Effect of prophylactic fentanyl buccal tablet on episodic exertional dyspnea: a pilot double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(6):798–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hui D, Kilgore K, Park M, Williams J, Liu D, Bruera E. Impact of prophylactic fentanyl pectin nasal spray on exercise-induced episodic dyspnea in cancer patients: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(4):459–468, e451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 148(2):141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edelman EJ, Gordon KS, Crothers K, et al. Association of prescribed opioids with increased risk of community-acquired pneumonia among patients with and without HIV. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luymes CH, Poortvliet RKE, van Geloven N, et al. Deprescribing preventive cardiovascular medication in patients with predicted low cardiovascular disease risk in general practice - the ECSTATIC study: a cluster randomised non-inferiority trial. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S, Tannenbaum C. Effect of a pharmacist-led educational intervention on inappropriate medication prescriptions in older adults: the D-prescribe randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1889–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, Hilmer SN. Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(4):303–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edey R, Edwards N, Von Sychowski J, Bains A, Spence J, Martinusen D. Impact of deprescribing rounds on discharge prescriptions: an interventional trial. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018; 41(1):159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vrettos I, Voukelatou P, Katsoras A, Theotoka D, Kalliakmanis A. Diseases linked to polypharmacy in elderly patients. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2017;2017:4276047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calderon-Larranaga A, Gimeno-Feliu LA, Gonzalez-Rubio F, et al. Polypharmacy patterns: unravelling systematic associations between prescribed medications. Plos One. 2013;8(12):e84967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]