Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Among sarcomas, which are rare cancers, many types are exceedingly rare; however, a definition of ultra-rare cancers has not been established. The problem of ultra-rare sarcomas is particularly relevant because they represent unique diseases, and their rarity poses major challenges for diagnosis, understanding disease biology, generating clinical evidence to support new drug development, and achieving formal authorization for novel therapies.

METHODS:

The Connective Tissue Oncology Society promoted a consensus effort in November 2019 to establish how to define ultra-rare sarcomas through expert consensus and epidemiologic data and to work out a comprehensive list of these diseases. The list of ultra-rare sarcomas was based on the 2020 World Health Organization classification, The incidence rates were estimated using the Information Network on Rare Cancers (RARECARENet) database and NETSARC (the French Sarcoma Network’s clinical-pathologic registry). Incidence rates were further validated in collaboration with the Asian cancer registries of Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.

RESULTS:

It was agreed that the best criterion for a definition of ultra-rare sarcomas would be incidence. Ultra-rare sarcomas were defined as those with an incidence of approximately ≤1 per 1,000,000, to include those entities whose rarity renders them extremely difficult to conduct well powered, prospective clinical studies. On the basis of this threshold, a list of ultra-rare sarcomas was defined, which comprised 56 soft tissue sarcoma types and 21 bone sarcoma types.

CONCLUSIONS:

Altogether, the incidence of ultra-rare sarcomas accounts for roughly 20% of all soft tissue and bone sarcomas. This confirms that the challenges inherent in ultra-rare sarcomas affect large numbers of patients.

Keywords: drug development, incidence, rarity, registry, sarcoma, ultra-rare

INTRODUCTION

Rare cancers are defined as malignancies with an incidence of <6 per 100,000 per year.1–5 This definition is the result of a consensus effort within the European oncology community that took place in the context of a project funded by the European Union entitled Surveillance of Rare Cancers in Europe (RARECARE).

The definition of rare cancers is based on incidence, and not on prevalence, because it is in rare non-neoplastic diseases.1,6 The incidence-based criterion for defining rare cancers has been internationally recognized and is currently used in Europe, the United States, and Eastern Asian countries.5,7,8 In Europe, 12 families of rare cancers were identified with a wide consensus in the context of the Joint Action on Rare Cancers, launched by the European Union.6 Sarcomas are 1 of the rare cancer families with an incidence of <6 per 100,000.6

Among sarcomas, many types are exceedingly rare. They could be labeled as ultra-rare, as in the EU Clinical Trials Regulation (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2014). This regulation identifies ultra-rare diseases as having a prevalence of <2 per 100,000. However, a definition of ultra-rare cancers has yet to be established.

Within the sarcoma community, the problem of ultra-rare types is particularly relevant. The 2020 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of bone sarcoma (BS) and soft tissue sarcoma (STS) listed approximately 100 different sarcomas and mesenchymal tumors of intermediate malignancy.9 Most of these entities, representing unique diseases, are ultra-rare. Rarity poses major challenges for diagnosis, with approximately 20% of all sarcomas being misclassified when diagnosed outside reference centers,10 for understanding disease biology, and for generating clinical evidence to support new drug discovery and development. This also leads to a specific problem in the regulatory setting because formal authorization for novel therapies by regulatory agencies is difficult to achieve. Consequently, off-label use of medication, when affordable, is frequently the only way to access active treatments for those patients.

With this background, a representative, multidisciplinary group of experts from the global sarcoma community convened at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Connective Tissue Oncology Society (CTOS) and initiated a process to reach a definition and a list of ultra-rare sarcomas. This list was intended to increase awareness of the wide variety of histologic types with limited incidence in the sarcoma family of tumors, to direct efforts to describe their natural history, and to develop novel ways to evaluate therapies in these malignancies, thus paving the way for discussion with academia, pharma, and regulatory bodies regarding the optimal method to facilitate the correct development and approval of novel therapeutics for patients with ultra-rare sarcoma.

Here, we provide a summary of the consensus process that led to the definition of ultra-rare sarcomas and, accordingly, the list of ultra-rare sarcomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A consensus meeting was organized under the umbrella of CTOS (Tokyo, November 13, 2019). Representatives from 30 sarcoma reference centers in the European Union, the United States, Canada, Asia, and Australia, covering all disciplines involved in the research and care of patients with sarcoma (epidemiology, pathology, molecular biology, radiology, surgery, radiation therapy, medical oncology) attended the meeting.

Before the meeting, a list of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), STS, and BS entities was circulated, using the 2013 WHO classification of soft tissue and bone tumors as a backbone.11 Mesenchymal neoplasms included in the WHO classification of tumors of the breast,12 head and neck,13 female genital organs,14 central nervous system,15 and hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues were added.16 Only histologies with metastatic potential were included.

In the identification and definition of each specific entity, it was decided not to take into account criteria beyond the WHO classification, such as molecular subtypes within each histology, specific anatomic locations, disease extent, age, or atypical presentations.

For those entities with data already available in population-based cancer registries (CRs), incidence rates were estimated through the Information Network on Rare Cancers (RARECARENet) project database (www.rarecarenet.eu). This database is drawn from EUROCARE-5, the widest collaborative study on the survival of patients with cancer in Europe (www.eurocare.it). Data on incidence (years of diagnosis, 2000-2007) estimated through RARECARENet were subsequently compared with those extracted by the NETSARC registry (the clinical-pathologic registry of the French Sarcoma Network).17 Given the centralized histologic review of all cases performed within NETSARC, the risk of misclassification inevitably implicit in CRs, which are constructed on community-based pathologic diagnoses, was minimized. Second, it allowed for the inclusion of diagnoses described in the 2013 WHO classification for which CR data are not yet available. Incidence rates were further validated in collaboration with the Asian CRs of Japan, Korea, and Taiwan (years of diagnosis, 2011-2015), all of which contribute to the RARECARENet Asia project.8 Supporting Tables 1 and 2 summarize the list of entities for which the estimation of incidence was possible.

The CTOS panel of experts was provided with the incidence data for all STS and BS entities and was asked to: 1) agree about the best indicator for defining ultra-rare sarcomas, 2) identify those sarcomas for which undertaking prospective large clinical studies (eg, statistically powered randomized trials) is a major challenge, and 3) agree on the incidence cutoff to distinguish ultra-rare sarcomas (ie, the entities for which undertaking large prospective studies is a major challenge) from other sarcomas.

Once the fifth edition of the WHO soft tissue and bone classification6 became available in 2020, the list of ultra-rare sarcomas already agreed by the authors on the basis of incidence was enriched with some of the newest entities introduced for the first time in the last WHO classification but whose incidence could not be estimated by either RARECARENet (data refer to 2000-2007) or NETSARC (2013-2016). The selection of entities to be added to the ultra-rare group was made based on expert opinions. Through the same process, new entities introduced in the latest edition of the WHO classification of female genital organ tumors14 and head and neck tumors13 were added if they met the criteria for classification as ultra-rare.

The final list of ultra-rare sarcomas also was shared with all CTOS ultra-rare sarcoma consensus effort members who could not attend the consensus meeting.

RESULTS

An agreement was confirmed to base the definition of ultra-rare sarcomas on incidence. It is notable that the precise incidence of ultra-rare cancers is often difficult to estimate, both because of rarity and, in some cases, recency of definition.

Supporting Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the incidence rate of GIST and of STS and BS, respectively, ranked by declining incidence rate. The list of entities and their incidence indicate that the group reached a consensus about an incidence threshold of approximately ≥1 per 1,000,000 per year as the cutoff for identifying ultra-rare sarcomas.

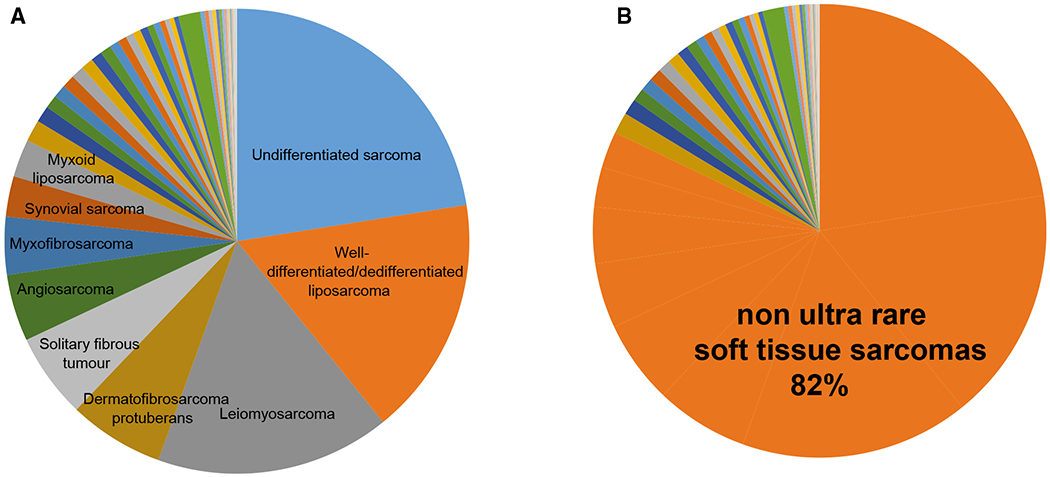

The CTOS panel of experts perceived that conventional approaches to clinical studies are feasible for STS with an annual incidence >1 per 1,000,000 (ie, GIST, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, well differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, der-matofibrosarcoma protuberans, solitary fibrous tumor, angiosarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and myxoid liposarcoma), which account for approximately 80% of all STS (Fig. 1A,B). The remaining 20% represent the group of ultra-rare STS (Fig. 1A,B). Table 1 lists the ultra-rare STS identified by consensus on the basis of incidence together with the ultra-rare STS identified by consensus only. Overall, ultra-rare STS include 56 different soft tissue sarcoma types.

Figure 1.

Ultra-rare soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are compared with non-ultra-rare STS, illustrating (A) nonultra-rare STS types and (B) the percentage of nonultra-rare STS among all STS.

TABLE 1.

List of Ultra-Rare Soft Tissue Sarcomas Identified Based on Incidence and of Ultra-Rare Soft Tissue Sarcomas Identified on Expert Consensus Only

| Incidence Based on Population-Based Registries (RARECARENet EU, Asia, NETSARC) | WHO (Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors, Gynecologic, Head and Neck, Hematologic)a |

|---|---|

| Adult fibrosarcoma Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma Alveolar soft part sarcoma Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma Clear cell sarcoma Desmoplastic small round cell tumor Ectomesenchymoma Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma Embryonal sarcoma of the liver Endometrial stromal sarcoma |

High-grade BCOR-rearranged endometrial stromal sarcoma High-grade YWHAE-rearranged endometrial stromal sarcoma |

| Endometrial stromal sarcoma, low grade Epithelioid sarcoma Extrarenal malignant rhabdoid tumor Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma Extraskeletal osteosarcoma Fibroblastic reticular cell tumor Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma Giant cell tumor of soft tissues Hemangioendothelioma, composite Hemangioendothelioma, epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma, pseudomyogenic Hemangioendothelioma, retiform Histiocytic sarcoma Infantile fibrosarcoma Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma |

Indeterminate dendritic cell tumor Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma |

| Intimal sarcoma Langerhans cell sarcoma Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma Low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma Malignant glomus tumor Malignant granular cell tumor Malignant myoepithelioma/myoepithelial carcinoma Malignant tenosynovial giant cell tumor Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor, malignant Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma PEComa, excluding nonepithelioid angiomyolipoma Phyllodes tumor, malignant Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor, malignant Pleomorphic liposarcoma Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma Round cell sarcoma/Ewing-like sarcoma |

CIC-rearranged sarcoma Round cell sarcoma with EWSR1-non-ETS fusions Sarcoma with BCOR genetic alterations |

| Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma Spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma |

Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma Inflammatory leiomyosarcoma Malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumor Metastasizing leiomyoma Myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma NTRK-rearranged spindle cell sarcoma (emerging) |

Abbreviations: EU, European Union; NETSARC, French clinical reference network for soft tissue and visceral sarcomas; PEComa, perivascular epithelial cell tumor; RARECARENet, Information Network on Rare Cancers; WHO, World Health Organization.

This column includes soft tissue sarcoma histologic types not found in the population registries according to the 2020 WHO classifications of soft tissue and bone tumors.

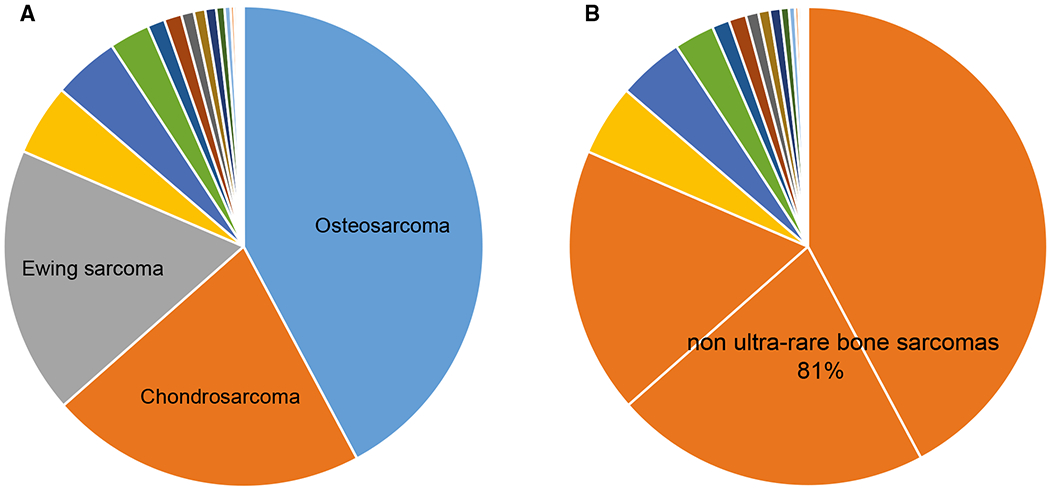

Table 2 lists the ultra-rare BS identified by consensus on the basis of incidence together with the ultra-rare BS identified by consensus only. Osteosarcoma, conventional chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma each have an annual incidence of >1 per 1,000,000, accounting for 80% of all BS. The remaining 20% of BS consist of ultra-rare BS (Fig. 2A,B). Of all BS, those that are ultra-rare comprise 22 different bone sarcoma types.

TABLE 2.

List of Ultra-Rare Bone Sarcomas Identified Based on Incidence and Based on Expert Consensus Only

| Incidence Based on Population-Based Registries (RARECARENet EU, Asia, NETSARC) | WHOa |

|---|---|

| Adamantinoma Angiosarcoma of bone Chondrosarcoma, clear ceil Chondrosarcoma, dedifferentiated |

Chondrosarcoma, periosteal |

| Chordoma, conventional Chordoma, dedifferentiated |

Chordoma, poorly-differentiated |

| Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of bone Fibrosarcoma of bone Leiomyosarcoma of bone Low-grade central osteosarcoma Malignancy in giant ceil tumor of bone/giant ceil tumor of bone, malignant Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma Osteosarcoma, parosteal Osteosarcoma, periosteal Osteosarcoma, high-grade surface Undifferentiated high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma of the bone |

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the bone CIC-rearranged sarcoma Round cell sarcoma with EWSR1–non-ETS fusions Sarcoma with BCOR genetic alterations |

Abbreviations: EU, European Union; NETSARC, the French clinical reference network for soft tissue and visceral sarcomas; RARECARENet, Information Network on Rare Cancers; WHO, World Health Organization.

This column includes only bone sarcoma histologic types not found in the population registries according to the 2020 WHO classifications of soft tissue and bone tumors.

Figure 2.

Ultra-rare bone sarcomas (BS) are compared with non-ultra-rare BS, illustrating (A) nonultra-rare BS types and (B) the percentage of nonultra-rare BS among all BS.

DISCUSSION

BS and STS include roughly 100 different pathologic entities, as described in the 2020 WHO sarcoma classification,9 many of which are ultra-rare. Each of these entities is marked by a specific morphology, biology, natural history, sensitivity to medical agents, and prognosis.18 Their number increases every year, as new molecular markers are identified. Research and care in ultra-rare tumors are major challenges, with major consequences for patients. To overcome these hurdles, there is an urgent need to improve patient centralization as well as the interactions of researchers and patients, on one side, and regulators, on the other. With this background, a representative group of the global sarcoma community, under the umbrella of the CTOS, met together to agree on how to define ultra-rare sarcomas through expert consensus and epidemiologic data and to work out a comprehensive list of these diseases.

By consensus, it was agreed that the best criterion for a definition of rare cancers and thus ultra-rare cancers is incidence rather than prevalence. Ultra-rare sarcomas were defined as those sarcomas with an annual incidence of approximately ≥1 per 1,000,000, to include sarcoma entities whose rarity makes it extremely difficult to conduct well powered prospective clinical studies. On the basis of this threshold, it was determined that ultra-rare sarcomas comprise 56 STS and 21 BS types, each of which deserves to be specifically investigated and treated. Altogether, the incidence of ultra-rare sarcomas accounts for roughly 20% of all STS and BS. This demonstrates that challenges inherent to being a patient who develops an ultra-rare sarcoma affect large numbers of patients overall. The consensus group eventually agreed that this list of ultra-rare entities needs to be revised on a regular basis as new sarcoma entities are identified and updated incidence data become available.

The incidence of the various ultra-rare sarcomas was consistently low across Asia and Europe. The only 2 exceptions were phyllodes tumor and low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, the incidence of which in Europe/RARECARENet as well as in Asia was slightly greater than 1 per 1,000,000. However, these 2 entities had a much lower incidence in the NETSARC database, most probably because of diagnostic quality issues. On this basis, by expert consensus, phyllodes tumor and low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma were included among the ultra-rare sarcomas.

Similar to the process used for developing the list of rare cancers by EUROCARE, we agreed to base the list of ultra-rare sarcomas on the WHO classification, which, in turn, uses a combination of anatomy and histology and molecular biologic features to distinguish sarcoma types. Histopathologic features are just 1 of the attributes that single out any clinical presentation. In addition to being affected by a given histologic sarcoma type, a patient obviously presents with a spectrum of clinical features, which may be rare and ultra-rare as well, such as a rare anatomic location or an unusual age, sex, etc. Although clinical presentations can affect prognosis and dictate treatment, the WHO classification was chosen because it is the list of cancer entities currently used to define and stratify diseases. Obviously, any clinical decision will be based on several factors, ie, clinical characteristics of the individual presentation as well as molecular features (namely, when a treatment may be molecularly targeted, a molecular marker is relevant from the prognostic point of view, etc).

The proposal of a threshold for defining ultra-rare sarcomas was also intended to help regulatory agencies to single out specific entities that are particularly challenging from a research standpoint. Ultimately, this means preventing patients who have ultra-rare sarcoma from missing opportunities for the identification and approval of effective therapies. Compared with more common entities, ultra-rare sarcomas are often poorly characterized with regard to their epidemiology, biology, natural history, prognostic and predictive factors, and sensitivity to standard treatments. Currently, there is no mechanism for bidirectional communication between clinicians, researchers, and regulatory bodies. We suggest that this could be achieved through regular mutual updates between the ultra-rare disease communities and regulators. In ultra-rare sarcomas, large studies are only possible with either long study durations and/or the involvement of a very large number of study sites (with corresponding quality-control issues). This invariably decreases the interests of pharmaceutical companies to invest in and develop new agents in these tumors, even when an agent may be available for other indications. Therefore, methodological issues add to the typical challenge of orphan drugs: ie, the limited market. Large randomized clinical studies have not been undertaken for most ultra-rare sarcomas.17 Exceptions include 2 randomized trials in alveolar soft part sarcoma, which is an ultra-rare STS. One of these studies was launched by the National Cancer Institute in 2011 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01391962) and is still open to recruitment. The second trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01337401) took 5 years to enroll 48 patients in 3 countries and met the primary end point, but there was no submission for regulatory approval. Another recent example was a novel agent with positive outcomes for epithelioid sarcoma, requiring a confirmatory randomized trial versus placebo in Europe before any approval and in the United States for anything beyond conditional approval.

Currently, there is only 1 drug specifically approved for 1 of the 56 ultra-rare STS entities on the list, and it is only approved by the US Food and Drug Administration: tazemetostat in epithelioid sarcoma.19 By contrast, although pexidartinb could be investigated in a randomized study in localized tenosynovial giant cell tumor, leading to its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019, this is not feasible in the ultra-rare malignant tenosynovial giant cell tumor subtype.20

Most potentially active new and old drugs in ultra-rare sarcomas are often used as off-label treatments. Interestingly, off-label agents in ultra-rare sarcomas are often suggested, even as first-line therapy, by US, EU, and Japanese clinical practice guidelines.21–24 The main barrier to label extension for drugs already on the market is that the initiative to file for approval can only be taken by pharmaceutical companies, whose interest is usually low when a drug is almost off-patent or is already available as a generic agent. Clearly, this results in discrepancies across countries and discrimination against patients affected by ultra-rare sarcomas.

To improve this situation, new study designs need to be conceived, adopted, and endorsed, particularly from the regulatory standpoint. In the area of ultra-r are sarcomas, disease-based discussions with regulatory agencies need to be planned on a regular basis, before embarking on the assessment of specific agents, including the incorporation of expert scientific advice, which affects the type of study protocol proposed for development. If an internal control arm is not feasible, optimizing the collection of external high-quality data by clinical registries should be encouraged. In the European Union, an opportunity not to miss is the involvement of the European reference networks: ie, networks of cancer centers appointed by their governments to treat and research rare cancers. When label extension is not feasible, centralizing the use of selected off-label agents in sarcoma networks would be a way to guarantee appropriateness. Current patients would benefit from new treatments that are likely to be effective, and future patients would benefit from additional knowledge gathered by expert centers. Adaptive regulatory pathways could be instrumental in this regard.

All this requires a sustainable global collaborative effort. Therefore, the sarcoma research community should be able to collaborate on a global scale. Pharmaceutical companies should value partnerships with academia. Regulatory bodies should listen to the disease-based communities, involving researchers and patient advocates. Ultimately, this will involve close scrutiny and knowledge of each type of ultra-rare sarcoma. This is easy when dealing with common cancers. It may be exceedingly difficult when dealing with rare cancers. It may be almost impossible unless a concerted effort is made when dealing with ultra-rare cancers, such as the one-fifth of patients who have sarcomas that belong to the rare family of sarcomas.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to Barbara Rapp from the Connective Tissue Oncology Society for her invaluable support in organizing the consensus meeting.

FUNDING SUPPORT

Jean-Yves Blay was supported by grants from LYon Recherche Innovation contre le CANcer (LYRICAN) (Institut National du Cancer [INCa] and Ministry of Health [Direction gènèrale de l’offre de soins [DGOS]-Institute National de la Santè et de la recherche medicale [INSERM] 12563), French Clinical Reference Network for Soft Tissue and Visceral Sarcoma (NETSARC) (INCa and DGOS), InterSARC (INCa), DEvweCAN (ANR-10-LABX-0061), PIA Institut Convergence Francois Rabelais PLAsCAN (PLASCAN, 17-CONV-0002), RHU4 DEPGYN (ANR-18-RHUS-0009), and European Reference Network for Rare Adult Solid Cancer (EURACAN) (EC 739521). Inga-Marie Schaefer was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (K08 CA241085).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Silvia Stacchiotti reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from Adaptimmune Therapeutics, Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Deciphera, Epizyme, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Immune Design, Karyopharm, Maxivax, Novartis, and PharmaMar outside the submitted work and institutional financial interest in Advenchen, Amgen-Dompe, Bayer, Epizyme, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Karyopharm, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar, and Spring Works Therapeutics. Anna Maria Frezza reports institutional financial interest in Advenchen, Amgen-Dompe, Bayer, Epizyme, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Karyopharm, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar, and SpringWorks Therapeutics. Jean-Yves Blay reports research support and honoraria from Roche, Bayer, PharmaMar, Deciphera, and Merck Sharpe & Dohme outside the submitted work. Judith V. M. G. Bovee reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from PharmaMar, Eli Lilly, Bayer, and Eisai; research grants from PharmaMar, Eisai, Immix-BioPharma, and Novartis; and institutional research funding from PharmaMar, Eli Lilly, Adaptimmune Therapeutics, AROG, Bayer, Eisai, Lixte, Karyopharm, Deciphera, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Blueprint, Nektar, Forma, Amgen, and Daiichi outside the submitted work. Paolo G. Casali reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from Bayer, Deciphera, Eisai, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer outside the submitted work and institutional financial interest in Advenchen Laboratories, Amgen Dompe, AROG Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi-Sankyo, Deciphera, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Epizyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Karyopharm, Novartis, Pfizer, and PharmaMar. George D. Demetri reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from GlaxoSmithKline, EMD-Serono, Sanofi, ICON plc, MEDSCAPE, Mirati, WCG/Arsenal Capital, Polaris, MJ Hennessey/OncLive, C4 Therapeutics, Synlogic, and McCann Health outside the submitted work; is a consultant with minor equity holdings in G1 Therapeutics, Caris Life Sciences, Erasca Pharmaceuticals, RELAY Therapeutics, Bessor Pharmaceuticals, Champions Biotechnology, Caprion/HistoGeneX, and Ikena Oncology; is a member of the board of directors and a consultant with minor equity holdings in Blueprint and Translate BIO; holds patents/royalties from Novartis (to Dana-Farber Cancer Institute); and is a scientific consultant with sponsored research to Dana-Farber from Bayer, Pfizer, Novartis, Epizyme, Roche/ Genentech, Epizyme, LOXO Oncology, AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, PharmaMar, Daiichi-Sankyo, and AdaptImmune Therapeutics outside the submitted work. Jayesh Desai reports research support from Roche/Genentech, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and GlaxoSmithKline and personal fees from Amgen, Eisai, and Pierre-Fabre outside the submitted work. Suzanne George reports institutional research support from Novartis, Bayer, Pfizer, Blueprint, Deciphera, Daiichi-Sankyo and personal fees from Bayer, Blueprint, Deciphera, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Eli Lilly outside the submitted work. Mrinal M. Gounder reports research grants and personal fees from Karyopharm; and honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from Bayer, SpringWorks Therapeutics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Epizyme, Amgen, TRACON, Flatiron, Medscape, Physicians Education Resource, Guidepoint, GLG, and UpToDate outside the submitted work. Robin L. Jones reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from Adaptimmune Therapeutics, Athenex, Blueprint, Clinigen, Eisai, Epizyme, Daichii, Deciphera, Immune Design, Lilly, Merck, PharmaMar, Tracon, and UpToDate and grants or research support from Merck Sharp & Dohme and GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. David G. Kirsch is cofounder of XRad Therapeutics, serves on the Lumicell Scientific Advisory Board, and reports research funding from Merck, XRad Therapeutics, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Varian Medical Systems outside the submitted work. Axel Le Cesne reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from PharmaMar, Bayer, Lilly, and Deciphera outside the submitted work. Shreyaskumar R. Patel reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from Immune Design, Epizyme, Daiichi-Sankyo, Dova, Deciphera, and Bayer and research grants from Blueprint, and Hutchison MediPharma outside the submitted work. Albiruni R. A. Razak reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from Eli Lilly, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Merck, Adaptimmune Therapeutics, and GlaxoSmithKline and institutional research support from Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Karyopharm, Boston Biochemical, Deciphera, Genentech, Roche, Pfizer, Medimmune, Eli Lilly, Boehringer-Ingleheim, Entremed/CASI Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Champions Oncology, Iterion, and Blueprint outside the submitted work. Damon R. Reed reports travel funding from Salarius Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Piotr Rutowski reports honoraria and consultancy or advisory fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pierre-Fabre, Sanofi, Merck, and Blueprint outside the submitted work. Roberta G. Sanfilippo reports institutional financial interests in Advenchen, Amgen-Dompe, AROG Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Blueprint, Daiichi-Sankyo, Deciphera, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Epizyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Karyopharm, Novartis, Pfizer, and PharmaMar and honoraria/travel grants from PharmaMar outside the submitted work. Marta Sbaraglia reports travel grants from PharmMar outside the submitted work. William D. Tap reports personal fees from Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Eisai, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi-Sankyo, Blueprint, Loxo, GlaxoSmithKline, Agios Pharmaceuticals, NanoCarrier, Deciphera, and C4 Therapeutics outside the submitted work; has a patent pending to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center/Sloan Kettering Institute for “Companion Diagnostic for CDK4 inhibitors-14/854,329”; reports personal fees from Certis Oncology Solutions outside the submitted work; and is co-founder of Atropos Therapeutics and owns stock in the company. David M. Thomas reports consultancy or advisory fees from Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Bayer and research support from Roche, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Eisai, Bayer, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Elevation Oncology, and Seattle Genetics outside the submitted work. Winette van der Graff reports advisory fees from Bayer and GlaxoSmithKline, consultant fees from SpringWorks Therapeutics, and research grants from Novartis outside the submitted work. Margaret von Mehren reports honoraria from Novartis, Deciphera, and GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. Andrew J. Wagner reports consulting fees from Daiichi-Sankyo and Deciphera outside the submitted work and institutional financial interests in Aadi Biosciences, Daiichi-Sankyo, Deciphera, Karyopharm, and Plexxikon. Angelo P. Dei Tos reports honoraria from Roche, Bayer, PharmaMar, and Merck Sharp & Dohme outside the submitted work. The other authors had no disclosures.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gatta G, van der Zwan JM, Casali PG, et al. Rare cancers are not so rare: the rare cancer burden in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2493–2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures, 2017. American Cancer Society; 2017. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-special-section-rare-cancers-in-adults.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bustamante-Teixeira MT, Latorre MDRDO, Guerra MR, et al. Incidence of rare cancers in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Tumori. 2019;105:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeSantis CE, Kramer JL, Jemal A. The burden of rare cancers in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:261–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botta L, Gatta G, Trama A, et al. RARECARENet Working Group. Incidence and survival of rare cancers in the US and Europe. Cancer Med. 2020;9:5632–5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casali PG, Trama A. Rationale of the rare cancer list: a consensus paper from the Joint Action on Rare Cancers (JARC) of the European Union (EU). ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Botta L, et al. Burden and centralised treatment in Europe of rare tumours: results of RARECARENet—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1022e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuda T, Won YJ, Chun-Ju Chiang R, et al. Rare cancers are not rare in Asia as well: the rare cancer burden in East Asia. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;67:101702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO Classification of Tumours. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors. 5th ed, Vol 3. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://publications.iarc.fr/588 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perrier L, Rascle P, Morelle M, et al. The cost-saving effect of centralized histological reviews with soft tissue and visceral sarcomas, GIST, and desmoid tumors: the experiences of the pathologists of the French Sarcoma Group. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. WHO Classification of Tumors. 4th ed, Vol 5. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldblum JR, Lazar AJ, Schnitt SJ, et al. Chapter 5: Mesenchymal tumours of the breast. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. WHO Classification of Tumours. Breast Tumours. 5 th ed, Vol 2. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019:187–230. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://publications.iarc.fr/581 [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, eds. WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours. WHO Classification of Tumors. 4th ed, Vol 9. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim KR, Lax SF, Lazar AJ, et al. Chapter 6: Tumours of the uterine corpus. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. WHO Classification of Tumours. Female Genital Tumors. 5th ed, Vol 4. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020:272–300. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://publications.iarc.fr/592 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. , eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. WHO Classification of Tumors. Revised 4th ed, Vol 1. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. , eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. WHO Classification of Tumors. Revised 4th ed, Vol 2. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Pinieux G, Karanian M, Le Loarer F, et al. Nationwide incidence of sarcomas and connective tissue tumors of intermediate malignancy over four years using an expert pathology review network. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246958. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.19.20135467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casali PG, Dei Tos AP, Gronchi A. When does a new sarcoma exist? Clin Sarcoma Res. 2020;10:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gounder M, Schoffski P, Jones RL, et al. Tazemetostat in advanced epithelioid sarcoma with INI1/SMARCB1 loss: results from an international, open-label, phase 2 basket study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;911:1423–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tap WD, Gelderblom H, Palmerini E, et al. ; ENLIVEN Investigators. Pexidartinib versus placebo for advanced tenosynovial giant cell tumour (ENLIVEN): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394:478–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casali PG, Bielack S, Abecassis N, et al. Bone sarcomas: ESMO-PaedCan-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 4):iv79–iv95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, et al. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 4):iv268–iv269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, et al. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, version 2.2018. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:536–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Japanese Orthopaedic Association Soft Tissue Tumor Guideline Committee. Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Soft Tissue Tumors. 3rd ed. Nankodo; 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.