Abstract

Poxviruses have been long regarded as potent inhibitors of apoptotic cell death. More recently they have been shown to inhibit necroptotic cell death through two distinct strategies. These strategies involve either blocking virus sensing by the host pattern recognition receptor, DAI/ZBP1, or alternatively blocking a later stage in necroptosis by inhibition of activation of the executioner of necroptosis, MLKL. The former, specifically blocks DAI/ZBP1-dependent necroptosis, leaving viruses susceptible to the death-receptor, and potentially TRIF-dependent necroptosis. The latter likely inhibits all modes of necroptotic cell death. As with inhibition of apoptosis, the evolution of potentially redundant viral mechanisms to inhibit programmed necroptotic cell death emphasizes the importance of this pathway in the arms race between hosts and pathogens.

Keywords: Programed cell death, apoptosis, Necroptosis, Poxviruses, E3L, Interferon, Z-nucleic acid binding protein

INTRODUCTION

Viruses and their hosts have co-evolved in an obligate relationship that has driven development strategies employed by both organisms to circumvent the defense systems of one another. Viruses exist and propagate as obligate intracellular parasitesd due to their dependency on the host’s cellular machinery, which places a large burden on the host. Due to this pressure, hosts have developed multiple mechanisms to recognize and eliminate viruses. In turn, viruses have evolved strategies to subvert the host’s antiviral defense mechanism to ensure propagation. Pathogenicity of a virus is heavily dependent on its ability to evade the host’s innate defense, largely driven by the antiviral state generated through the action of interferon (IFN) as well as other pro-inflammatory cytokines(Bowie and Unterholzner, 2008). This state is achieved through the upregulation of pathogen pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and their effectors including several proteins involved in programed cell death pathways. Programmed cell death of infected cells is a highly effective mechanism to contain pathogens by limiting replication in order to prevent the spread of a virus. The critical role that this process plays in a host’s defense against pathogens is exemplified by the presence of an abundance of inhibitors encoded by different pathogens to suppress programmed cell death (Cho et al., 2009; Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2010; Mocarski et al., 2015; Omoto et al., 2015; Upton et al., 2008, 2010). Here we discuss the various strategies poxviruses use to thwart the potent host defense mechanisms of different forms of programed cell death.

Interferon and the antiviral state that contribute to cell death

IFNs are a group of secreted cytokines that elicit an antiviral state in cells, altering the ability of viruses to survive and propagate (Isaacs and Lindenmann, 1957). They are systematically classified into three distinct groups. Of these groups, type I IFNs (IFN-α/β) have been the best characterized for their role of inhibiting viral replication through the innate immune system (Alsharifi et al., 2008; Bonjardim et al., 2009). Within the innate immune system, IFN-α/β act as a first line defense against viral infections (Samuel, 2001; Sen, 2001).

An antiviral state is initiated when type I IFNs bind to their ubiquitously expressed surface receptor proteins. This subsequently results in the activation of multiple signaling cascades that induce transcription of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) (Der et al., 1998). These ISGs are responsible for establishing an anti-viral state within cells through a multifaceted approach that not only includes regulating the machinery required for viral replication, but also enhances production of viral detection systems and increases local signaling, including IFN production, in order to prepare neighboring cells for an impending infection. The pleiotropic effects of IFN coordinate to heighten early pathogen detection systems and eliminate infected cells through programed cell death. This limits the replication and spread of viral infections (Bowie and Unterholzner, 2008).

The production of IFN and subsequent activation of ISGs are regulated by host-encoded PRRs capable of initiating multiple signaling cascades upon activation. These PRRs comprise a diverse group of receptors that recognize distinct pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). PAMPs sensed by PRRs are produced when viral infections generate foreign nucleic acids including viral genomic deoxy-ribose nucleic acid (DNA), single-stranded ribose nucleic acid (ssRNA), and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (Akira et al., 2006). This early detection process is critical for inducing IFN and subsequent upregulation of host proteins essential for generating a systematic antiviral state (Fu et al., 1999; Hough and Bass, 1994; Kim et al., 1994; Liu et al., 2011; Nishikura et al., 1991; O'Connell and Keller, 1994; Patterson and Samuel, 1995; Patterson et al., 1995).

Following its production, IFN is secreted into the extracellular environment where it can implement both autocrine and paracrine signaling patterns by binding to IFN-α/βRs on cell surfaces. IFN-α/βRs are composed of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits (Novick et al., 1994; Stark, 2007; Uze et al., 1990). The binding of IFN to its receptor induces a signal cascade involving Janus kinase (JAK), signal transducers, and the activation of transcription (STAT) pathways (Leung et al., 1995; Stark, 2007). This results in the formation of the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex (Bluyssen et al., 1996; Darnell et al., 1994). ISGF3 then translocates into the nucleus where it binds to IFN-stimulated response elements (ISREs) inducing the transcription of ISGs (de Veer et al., 2001; Stark, 2007).

ISGs that encode proteins with direct antiviral activity have a diverse range of functions including cytoskeletal remodeling, post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression, and the induction of cell death machinery such as caspases. Examples of these ISGs include IFN-stimulated protein of 15 kDa (ISG15), the GTPase myxovirus resistance 1 protein (Mx1), 2’,5’ oligoadenylate synthetases (OASs) and RNA-activated protein kinase, PKR (de Veer et al., 2001). Initiation of an antiviral state results from the complex interaction of multiple ISGs where no single gene has been shown to be absolutely essential for every virus.

One of the most effective consequences of these complex interactions involves priming cells to undergo programmed cell death (Best, 2008). This decreases the time needed to eliminate infected cells (Brierley and Fish, 2002; Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2010; Wenzel and Tuting, 2008) and is often faster than viruses can replicate. Of the many potential pathways utilized for priming, some of the more well-characterized include the induction of procaspase genes (de Veer et al., 2001), PKR (Sadler and Williams, 2008), and OAS (Kerr et al., 1977; Rebouillat and Hovanessian, 1999). Additionally, inactive pro-proteins are up-regulated and capable of inducing apoptosis upon activation by PAMPs such as dsRNA (Rebouillat and Hovanessian, 1999).

POXVIRUSES

Poxviruses are masters of evading innate immunity (Johnston and McFadden, 2003; Shisler and Moss, 2001). The Poxviridade family is composed of a unique cluster of large brick-shaped, enveloped viruses whose genome is composed of dsDNA. This family has a broad host range, infecting both vertebrates and invertebrates (Moss, 2007; Moss and Shisler, 2001). Of the eight genera belonging to the Poxviridade family, the Orthopoxvirus genus is the most well-characterized due to notorious members including variola virus (VARV), the causative agent of smallpox, as well as vaccinia virus (VACV), which is the prototypic poxvirus utilized to study both poxviruses and multiple facets of viral host interactions. Additionally, the genus includes monkeypox virus (MPXV), a recently emerging human pathogen that caused an outbreak in the United States in 2003 and continues to cause outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa (Reed et al., 2004).

Nearly a third of the poxvirus genome is devoted to genes that are not essential for replication in cell culture systems(Jacobs et al., 2009). They instead contribute to pathogenesis observed in animals by other means. Known as “accessory genes”, they work to modulate host immune mechanisms including IFN and consequences such as cell death.

Innate immune evasion by VACV E3L

E3L is one of the most critical and well-studied innate immune evasion genes (Brandt and Jacobs, 2001; Chang et al., 1992). It encodes an inhibitor of the host anti-viral interferon system known as the E3 protein. Until recently, the primary function of this protein has been ascribed to binding dsRNA produced by the virus, inhibition of dsRNA-mediated induction of IFN, and inhibition of IFN-induced dsRNA-dependent antiviral enzymes such as PKR and OAS (Beattie et al., 1995; Chang et al., 1995; Watson et al., 1991; White and Jacobs, 2012). Recently, however, it has been suggested that E3 can inhibit IFN-inducible necroptotic cell death (Koehler et al., 2017). Investigations utilizing vaccinia virus (VACV) have demonstrated that the gene encodes two forms of E3; a full length p25 form and a p20 form of the protein that lacks 37 N-terminal amino acids; initiating at an internal ATG codon (Chang and Jacobs, 1993; Yuwen et al., 1993). In an evolutionary sense, the gene was acquired by the chordopoxviruses after the split of the avipox/molluscipox/crocodillepox virus lineage from the parapox/orthopox virus lineage(Knapp et al., 2011). Both proteins encoded by E3L homologues in chordopoxviruses contain two well conserved nucleic acid-binding domains; a N-terminal Z-NA-binding domain (Zα) (Kim et al., 2003) and a C-terminal dsRNA-binding domain (Chang and Jacobs, 1993). Of these domains, the C-terminal dsRNA binding domain is well conserved amongst all poxviruses that encode E3 homologs. Additionally, the residues important for dsRNA-binding are conserved within cellular dsRNA-binding proteins such as PKR (Chang and Jacobs, 1993). The N-terminal Zα domain, on the other hand, is not as highly conserved in poxviruses due to an evolutionary loss of the N-terminal Zα within the leporipox viruses (Cameron et al., 1999; Willer et al., 1999) and in monkeypox viruses (MPXVs), where a truncated version of the N-terminal Zα encodes for a p20 E3 homologue that is lacking 37 N-terminal amino acids (Shchelkunov et al., 2002). This loss of the full-length Zα domain appears to be a relatively recent evolutionary event. In the case of the truncations observed, the region encoding these 37 amino acids is intact and well-conserved, but the ATG codon where translation normally initiates has been mutated due to downstream ATT shifting so that only a p20-like protein is produced (Arndt et al., 2015).

E3 is an essential and potent innate immune evasion protein. E3L-deficient VACV is both unable to replicate in most cell cultures (Beattie et al., 1996) and highly attenuated in animal models (Brandt and Jacobs, 2001). While wtVACV has a very broad host range allowing it to infect most mammalian and avian cells in culture, replication of E3L-deficient VACV mutants (VACVΔE3L) appears to be restricted (Chang et al., 1995). Even in cells that VACVΔE3L does replicate in, such as rabbit kidney, RK-13 cells virus replication is IFN sensitive, unlike wtVACV which is IFN resistant (Beattie et al., 1995; Shors et al., 1998). Both the narrow host range of VACVΔE3L and the IFN sensitivity observed when infecting RK-13 cells has been attributed to the C-terminal dsRNA-binding domain (Beattie et al., 1995; Beattie et al., 1996); although recent experiments suggest functions in addition to dsRNA-binding may be involved with the C-terminus (Dueck et al., 2015). Binding of the E3 protein C-terminus to dsRNA appears to sequester viral dsRNA (Arndt et al., 2016) which prevents the activation of the IFN-inducible host dsRNA-dependent antiviral proteins PKR and OAS along with the subsequent induction of apoptosis (Liu and Moss, 2016). Infections with VACVΔE3L or VACV encoding a truncated E3 lacking a dsRNA-binding domain result in the activation of PKR and subsequent phosphorylation of eIF2α. This causes an arrest of translation (Lee and Esteban, 1994) or activation of the OAS-RNase L pathway leading to the degradation of ribosomal RNA (Beattie et al., 1995). Failure to block either the PKR or OAS-RNase L pathways results in the dsRNA-mediated induction of type I IFN gene expression typically inhibited in wt VACV (Xiang et al., 2002).

Zα of E3

The Zα domain found within the N-terminus of E3 shares sequence similarity with the Z-DNA binding family of proteins. Prominent examples of proteins within this family include ZBP1 (aka DAI or DLM1), ADAR-1 (Kim et al., 2003) and PKZ (Rothenburg et al., 2005). Comparisons of these proteins to yatapoxvirus E3 homologues have found significant crystal structure homologies with the retention of Z-DNA oligonucleotide binding capabilities (Ha et al., 2008). Additionally, other viruses, such as the cyprinid herpesvirus ORF112, have been found to encode Zα-containing proteins (Kus et al., 2015) while host-encoded proteins such as ZBP1 and ADAR-1 have been found to be virus and/or IFN-inducible. It appears that from both a viral and host perspective, amino acids of Zα domains that contact Z-NA and are well conserved (Kim et al., 2003; Tome et al., 2013). This conservation suggests that these domains may play a key role in sensing of virus infection by host PRRs, as well as inhibiting sensing by PRRs. An example of this interaction has been observed with the cyprinid herpesvirus ORF112 protein which has been found to compete with PKZ for Z-NA binding through its Zα domain (Tome et al., 2013).

Investigations looking into E3’s two domains have found the function of the N-terminal Zα-binding domain to be more enigmatic when compared to the C-terminal dsRNA binding domain. This domain has been shown to be dispensable for replication in most cultured cells and does not contribute to IFN resistance in HeLa, RK-13, COS, CV-1 or BSC-40 cells (Chang et al., 1995). However, the domain is still required for full inhibition of the dsRNA sensor PKR in VACV-infected cells that lack necroptosis machinery. While the C-terminal dsRNA binding domain has been well characterized for its role in this inhibition, the N-terminal Zα domain’s role is less well understood (Langland and Jacobs, 2004).

PKR activation can be seen in VACVΔE3L-infected cells at the onset of intermediate gene expression, usually occurring by 2-3 hours post infection (hpi) (Chang and Jacobs, 1993). In contrast activation of PKR and OAS is only detectable at late times post infection (9 hpi) in cells infected with VACV-E3LΔ83N. The delayed activation of PKR and OAS appears to be due to an accumulation of free dsRNA in VACV-E3LΔ83N-infected cells at very late times post-infection (unpublished observations) despite the ability of E3Δ83N protein to bind to dsRNA with wt affinity and its accumulation to similar levels as wtE3 protein (Chang and Jacobs, 1993). Despite leading to activation of PKR and OAS in infected HeLa cells, VACV-E3LΔ83N replicates normally in these cells and is IFN resistant (Langland and Jacobs, 2004). Through the use of a yeast ectopic expression it was shown that inhibition of human PKR by the N-terminus of the variola virus E3 homologue maps to PKR binding sites that are distinct from the amino acid residues that confer binding to Z-NA (Thakur et al., 2014). Thus, Z-NA binding and PKR inhibition map to different locations suggesting two distinct functions of the N-terminus that act independently to either bind PKR or Z-NA.

Despite being non-essential for replication or IFN resistance in most cells in culture, the N-terminus of VACV E3L is essential for pathogenesis in mouse models (Brandt and Jacobs, 2001),. E3LΔ83N in the mouse adapted neurovirulent Western Reserve (WR) strain of VACV is significantly attenuated in mice infected either intra-nasally or intra-cranially in contrast to the wtVACV-WR. VACV-WR-E3LΔ83N replicates well at the initial site of inoculation but disseminates poorly to distal locations (Brandt et al., 2005). The N-terminal domain of the vaccinia virus E3L-protein is required for neurovirulence, but not for an induction of a protective immune response (Brandt et al., 2005).Pathogenesis has been found to be fully restored in Ifnar1−/− mice infected with VACV-WR-E3LΔ83N (White and Jacobs, 2012) which indicates that the N-terminus likely acts to inhibit the host anti-viral IFN system. Amongst mutants of E3L, pathogenesis correlates with binding affinity to Z-NA (Kim et al., 2003). The N-terminus of E3 can be functionally replaced with the Zα domains of either mouse ZBP1 or human ADAR-1, despite limited sequence identity (Kim et al., 2003). Among these domains, conservation is limited to the residues shown in crystal structures that interact with Z-NA or form the hydrophobic core of the domains. For a chimeric virus with the Zα of E3 substituted with the Zα of ADAR-1, pathogenesis correlates with the measured affinity for Z-NA amongst ADAR-1 Zα mutants. Notably, ADAR-1 contains a second Zβ domain with homology to Zα, but which contains an isoleucine (I335) at the position of a key tyrosine residue critical for binding Z-NA that interrupts binding to Z-NA. An ADAR-1 Zβ domain:E3 dsRNA binding domain chimeric virus is apathogenic in mice, but an I335Y mutation partially restores Z-NA binding while also partially restoring pathogenesis (Kim et al., 2003). For a wtVACV E3 protein, mutations of residues homologous to those that interact with Z-NA in the yatavirus E3 homologue crystal structure reduces pathogenesis (Ha et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2003). Thus, there is an excellent correlation between binding to Z-NA in vitro and pathogenesis in mice.

CASPASE DEPENDENT PROGRAMED CELL DEATH PATHWAYS

Caspases are classified as a family of ten or twelve cysteine proteases in mice and humans respectively. Caspases are present in all metazoans, including C. elegans, Drosophila, mouse and humans (Lamkanfi et al., 2002). These proteases are best known for their ability to dictate cell fate during development or infection by driving programed cell death and inflammation (Lamkanfi et al., 2002; Thornberry and Lazebnik, 1998). Caspases are maintained in the cell as inactive procaspases. Upon activation macromolecular signaling complexes drive aggregation of procaspases, promoting proximity mediated autoactivation and proteolytic processing. The consequence of caspase activation and signaling ultimately depends on the specific caspases involved. In general caspases are divided into functional categories of inflammation (Caspase-1, −4, −5, −11, and −12 ) (Kesavardhana and Kanneganti, 2017) or apoptosis mediators (Caspase-2, −3,−6,−7,−8, −9, and −10). Caspase-2, −6, −12, and −14 are poorly characterized and their function remains unclear(Kesavardhana et al., 2020).

Apoptosis overview

Apoptosis is a conserved form of caspase-dependent programmed cell death that consists of two main pathways that are dictated by the source of stimuli initiating the process; extrinsic or intrinsic stimuli. Regardless of the stimuli both activation of apoptotic pathways leads to the accumulation active caspases. These apoptotic caspases are grouped as either initiator and effector caspases based on their function in the apoptosis pathways. Initiator caspases (caspase-2, −8, −9, and −10) function as signal amplifiers used to activate the effector group of caspases. Effector caspases (caspase-3, −6, and −7) serve to proteolytically cleave numerous crucial cellular target proteins which eventually mediates apoptosis. In general, apoptosis is considered non-immunogenic, based on retention of all the cellular content within the apoptotic bodies, resulting in minimal inflammatory effects upon death. Both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways lead to activation of the Bcl-2 homology domain 3 (BH3)-only protein, Bid (Saelens et al., 2004). The extrinsic pathway is triggered by the binding of extracellular death receptor ligands such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), Fas ligand (FasL), and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) to their respective transmembrane receptors (Duprez et al., 2009). The intrinsic pathway is initiated when proteins such as cytochrome c, SMAC/Diablo, and HtrA2/Omi are released from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol in response to a variety of stresses such as chemotherapeutic drugs, UV irradiation, and microbial infection (Saelens et al., 2004)

Pyroptosis overview

Pyroptosis is a caspase-dependent and gasdermin-mediated programmed cell death. Pyroptosis is thought to play a key role in the clearance of various bacterial and viral infections by removing intracellular replication niches and enhancing the host's defensive responses(Bergsbaken et al., 2009; Jorgensen and Miao, 2015). This is an immunogenic form of programed cell death that is characterized by cell membrane pore formation, cytoplasmic swelling, membrane rupture and release of cytosolic contents such as activated IL-1β into the extracellular environment (Fink et al., 2008; Fink and Cookson, 2007). The canonical form of pyroptosis is initiated when damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) or PAMPs, including bacterial peptidoglycans, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), viral dsRNA, and intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Hornung et al., 2008; Kanneganti et al., 2006a; Kanneganti et al., 2006b; Latz et al., 2013; Mariathasan et al., 2006; Martinon et al., 2004; Martinon et al., 2006; Schroder and Tschopp, 2010), are sensed. Sensing of these molecular patterns leads to the activation of inflammasomes containing effector proteins including absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) (Rathinam et al., 2010), Pyrin(Heilig and Broz, 2018), and the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor (NLR) family (Fink et al., 2008; Gross et al., 2009; Malireddi et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2017). Activated inflammasomes recruit the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck like proteins (ASC). ASC contains a caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) that recruits caspase 1 leading to caspase 1 activation (Boucher et al., 2018). Active caspase-1 can cleave Gasdermin D (GSDMD). The N-terminal fragment of GSDMD mediates cell death though the formation of membrane pores, resulting in pyroptosis. Caspase-1 also promotes the maturation and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 during the pyroptosis. Non-canonical pyroptosis is mediated by caspases-4/5 in human cells and caspase-11 in mouse cells and is initiated by either direct activation of pro-caspases through direct recognition of cytosolic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) via a CARD domain (Kayagaki et al., 2011; Kovacs and Miao, 2017; Shi et al., 2014) or through mitochondrial and death receptor pathway mediated by caspase-3/Gasdermin E (GSDME) (Wang et al., 2017)

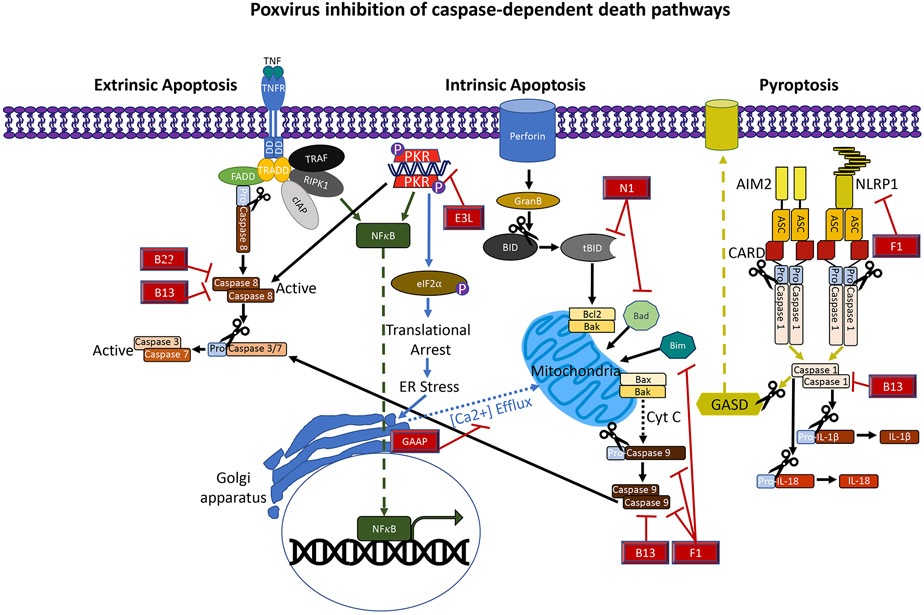

Poxvirus inhibition of caspase dependent cell death

Poxviruses are masters at evading programmed cell death both through direct inhibition of cell death machinery but also by blocking host recognition of infection. While this review has an emphasis on VACV-induced necroptosis it also highlights the multifaceted approach to restricting other forms of cell death (recently reviewed (Veyer et al., 2017)).

E3 was first identified as an inhibitor of apoptosis (Kibler et al., 1997). VACVΔE3L induces apoptosis in infected cells. Induction of apoptosis maps to the C-terminal dsRNA-binding domain of E3 protein. Inhibition of dsRNA synthesis in VACVΔE3L infected cells ablates induction of apoptosis, while synthesis of excess dsRNA in wtVACV-infected cells induces apoptosis. Induction of apoptosis is dependent on PKR (Zhang et al., 2008). In fact, this was some of the early evidence that activation of PKR could lead to apoptotic cell death. However, more recently, deletion of the E3L gene was shown to lead to reduced synthesis of another vaccinia virus inhibitor of apoptosis, F1 (Mehta et al., 2018). Again, inhibition of F1 translation is PKR dependent. This is somewhat surprising, since early gene expression is thought to proceed normally in VACVΔE3L infected cells and F1 is an early gene product. Nonetheless, it appears that the lack of expression of the apoptosis inhibitor, F1, sensitizes VACVΔE3L-infected cells to apoptosis. It has been suggested that vaccinia virus may have evolved to induce apoptosis in cells expressing excess dsRNA, by minimizing expression of F1, to minimize the pro-inflammatory effects of the potent PAMP, dsRNA (Mehta et al., 2018).

Inhibition of intrinsic apoptotic factors

VACV F1 protein is a potent inhibitor of intrinsic apoptosis (Wasilenko et al., 2003). F1 adopts a Bcl-2-fold and can interact with the Bcl-2-like pore-forming protein Bak and prevent Bak oligomerization (Wasilenko et al., 2005). F1 can also bind to BH3-domain only pro-apoptotic proteins Bim and Noxa and indirectly prevent activation of Bax (Eitz Ferrer et al., 2011; Wasilenko et al., 2005). The end result is an inhibition of release of cytochrome c through Bak/Bax mitochondrial pores (Stewart et al., 2005). In addition to the BCL-2-like domain, F1 contains an N-terminal extension that can bind to the key inflammasome initiator, NLRP1, and prevent inflammasome activation. Thus, F1 is a broad inhibitor of caspase-dependent death. A second VACV protein, N1, can also interact with BH3 domain containing proteins, and is a weak inhibitor of apoptosis (Cooray et al., 2007).The cytoplasmic poxvirus inhibitor of apoptosis is viral Golgi anti-apoptotic protein, vGAAP (Gubser et al., 2007). vGAAP contains a transmembrane Bax inhibitor-1 motif (TMBIM). vGAAP contains 6 transmembrane helices (Carrara et al., 2012), and inserts in the membranes of the Golgi apparatus and ER, where it acts as an ion channel and regulates Ca+2 flux, suppressing intrinsic and perhaps extrinsic apoptosis.

Inhibition of caspases

The poxvirus serpin protease inhibitors (serpins), SPI1 and SPI2, can inhibit caspase driven cell death (Veyer et al., 2017). SPI2, encoded by the vaccinia virus B13R gene, is the most potent of the vaccinia virus apoptosis inhibitors (Veyer et al., 2014). SPI2 has an aspartic acid at the cleavage site in its reactive site loop. For serpins, cleavage at in the reactive site loop, by an active protease leads to a covalent bond between the cleaved serpin and the protease, leading to suicide inhibition of that protease molecule (Bao et al., 2018). SPI2 was first shown to inhibit caspase 1, and thus, can likely inhibit pyroptosis. SPI2 has broad caspase inhibitory activity, inhibiting caspases-1, −3, −4, −5, −8, −9 and −10 (Veyer et al., 2017), and is a potent inhibitor of both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis (Veyer et al., 2014). Since active caspase-8 can cleave RIPK3 and inhibit necroptosis, SPI2 is necessary for TNF induction of necrotic death in VACV-infected cells, presumably by inhibiting caspase-8 cleavage of RIPK3 (Li and Beg, 2000).

SPI1, encoded by the vaccinia virus B22R gene, has also been reported to inhibit apoptosis (Ali et al., 1994; Brooks et al., 1995).This is somewhat surprising since the cleavage site in the reactive site loop is asparagine rather than aspartic acid. Thus, it is unclear if SPI1 can be cleaved non-specifically by some caspases, or if inhibition of apoptosis is indirect, after inhibiting of an asparagine specific protease, such as asparagine endoprotease. Nonetheless, SPI1 has been reported to be necessary to inhibit apoptosis in vaccinia virus-infected pig kidney PK-15 cells and human lung carcinoma A549 cells (Brooks et al., 1995).

Inhibition of secreted factors

In addition to the direct inhibitors of cell death, poxviruses encode numerous secreted cytokine binding proteins that can affect death, including IL-1b-, IL-18-, TNF- and IFN-binding proteins (Smith et al., 2013). Soluble TNF-binding proteins can inhibit death-receptor mediated apoptosis and necroptosis. Soluble IL-1b-and IL-18-binding proteins can modulate the effects of pyroptosis by sequestering IL-1b and IL-18 released from pyroptotic cells. Many poxviruses also encode soluble type I and type II IFN-binding proteins. Since several components of cell death pathways are IFN-inducible, including ZBP1, inhibition of IFN-induced pathways likely prevents up-regulation of pathway components needed for initiation of cell death.

The plethora of inhibitors of cell death encoded by poxviruses often makes study of cell death difficult in poxvirus-infected cells. Mutation of individual anti-apoptotic genes often yields viruses with little to no phenotype. Use of a synthetic virus, vv811, deleted of 55 vaccinia virus genes, including B13R, F1L and N1L, has allowed analysis of the role of these genes and vGAAP, which is naturally missing in the parent of this virus, in inhibition of apoptosis (Veyer et al., 2014). Despite this redundancy mutation of single genes can at times lead to induction of cell death. Perhaps the most relevant of these is VACVΔE3L, which induces apoptosis (Kibler et al., 1997), despite encoding functional B13R, B22R, F1L, and N1L genes, and VACV-E3LΔ83N, which alone induces necroptosis (Koehler et al., 2017). This suggests that while the anti-death genes of poxviruses are formidable, they can be overcome, presumably if the death inducing signal is strong enough.

NECROPTOSIS

Overview

For many years, programmed cell death was synonymous with apoptosis, but recently alternative programmed cell death pathways have been identified as important regulators of the innate immune response to viral infections. These alternative forms may be essential for host inhibition of viruses that encode anti-apoptotic genes (Cho et al., 2009). The field of virus-induced, programmed cellular death is rapidly evolving with apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis representing the key pathways involved in innate response to pathogens

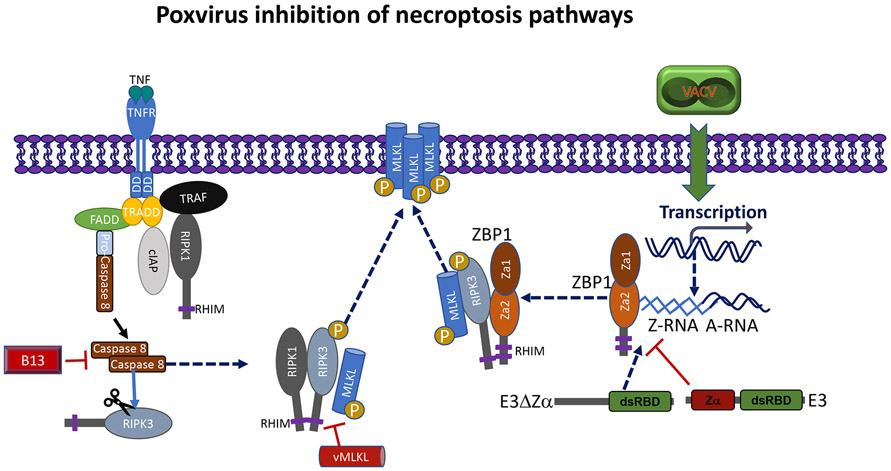

Necroptosis is an inflammatory form of programmed cell death that is an alternative host defense pathway initiated during the course of some viral infections when caspases are inhibited (Kaiser et al., 2013; Nogusa et al., 2016; Upton and Chan, 2014). Activation of necroptosis leads to a signal cascade that is dependent on the serine/threonine kinase receptor interacting protein kinase (RIPK) 3 and the downstream pseudokinase executer, mixed lineage kinase-like protein (MLKL) (Sun et al., 2012). RIPK3 is a serine/threonine kinase contains a “RIP homotypic interaction motif (RHIM). The RHIM is used to mediate interactions with the other RHIM-containing signal adaptors RIPK1, TRIF and ZBP1 (Sun et al., 2002). Necroptosis can be is initiated in response to multiple stimuli through signaling pathways including tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily via RIPK1, TLR3 or TLR4 via TRIF and through cytoplasmic sensing of nucleic acids via ZBP1. Regardless of the trigger, activation of RIPK3 and subsequent MLKL phosphorylation and agitation lead to membrane pore formation leading to rupture of the plasma membrane and release of pro-inflammatory DAMPs (Holler et al., 2000; Li and Beg, 2000).

Poxviruses like many large DNA viruses encode caspase inhibitors that allow the virus to circumvent apoptosis and other effects of caspases allowing for viral persistence and immune evasion as discussed above (Zhou et al., 1997). While this provides a strategic advantage against caspase dependent pathways it also sensitizes infected cells to RIKP3 dependent signaling including necroptosis. Necroptosis is now recognized as an important response against many viruses. Necroptosis has been recognized as an important response against poxviruses that is initiated both by TNF(Chan et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2009; Li and Beg, 2000) and ZBP1(Koehler et al., 2017). These two distinct necroptosis pathways both contribute to the host control of VACV and are mechanisms of restricting viral pathogenesis.

Caspase inhibitor encoded by VACV promotes TNF-α-mediate necroptosis

Conditions in which caspases are inhibited sensitizes cells to necroptosis which is now recognized as an important mechanism to limit viruses(Chan et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2009; Li and Beg, 2000). Some the early evidence of this came when the VACV-encoded SPI-2 inhibitor of caspases was shown to sensitize mouse 3T3 cells to TNF-α-induced cell death (Li and Beg, 2000). The 3T3 fibroblasts utilized in these experiments were resistant to TNF-α-mediated apoptosis but when infected with VACV and subsequently treated with TNF-α there was a significant loss in viability. This cell death was not associated with hallmarks of apoptosis such as cleaved PARP but was associated with increased levels of reactive oxygen species production. Importantly, the death did not occur when a non-functional SPI-2 was encoded by a mutant B13R gene. These results implicated the putative caspase inhibitor SPI2 in a viral enhancement of TNF-α-induced cytotoxicity (Li and Beg, 2000). Furthermore, this TNF-α-mediated “necrotic-like cell death” of the 3T3 fibroblasts was recapitulated in cells treated with peptidyl caspase inhibitors such as zVAD-fmk. While not clearly identified as the same molecular mechanism, a phenotypically similar death was seen in the presence of caspase inhibitors and dsRNA or interferonγ.

Following the identification of the specific mechanism of RIPK1-dependent necroptosis mediated by TNF-α via the TNFR superfamily (Holler et al., 2000) it was shown that TNFR-2 signaling can potentiate RIPK1-dependent necroptosis via TNFR-1 in VACV infected cells (Chan et al., 2003). Because TNF-α -induced necroptosis is blocked by caspase-8 cleavage of RIPK1, virus-encoded inhibitors of caspases brought to light the physiological significance of RIPK1 and necroptosis as a host defense mechanism against VACV. VACV infected Jurkat cells were highly sensitive to necroptosis which was reduced in RIPK1 deficient cells. More significantly VACV-infected Tnfr-2−/− mice had reduced inflammatory markers in the liver but had impaired viral clearance and higher viral titers at 4 dpi in the spleen and liver when compared to mice with functional TNF signaling. Notably, it was identified that not all caspase inhibitors sensitize cells to necroptosis. The expression of caspase inhibitors that contain death effector domain-containing such as MC159 gene from the poxvirus Molluscum contagiosum suppressed necroptosis, unlike the VACV SPI2 (Huttmann et al., 2015).

With the understanding that VACV-infected cells become sensitized to TNF-α -induced necrosis as a consequence of SPI2 and the use of an RNA interference screen RIPK3 was identified as a crucial regulator of necroptosis (Cho et al., 2009). The significate role that RIPK3 plays in necroptosis was the validated by examining the rate of cell death in activated wt and Ripk3−/− jurkat or MEF cells that we were infected with VACV and subsequently stimulated with TNF-α. The VACV-infected Ripk3−/− cells were resistant to TNF-α -induced necroptosis. Importantly, RIPK3 was required for protection against VACV. Ripk3−/− mice had significantly reduced tissue necrosis and inflammation resulting from VACV infection compared to wt mice. The Ripk3−/− mice also resulted in poor control of viral replication and had increased mortality. Together these results clearly implicated necroptosis as a potent host defense mechanism against VACV necessary to circumvent the viral suppression of the apoptosis machinery

ZBP1-mediated necroptosis in VACV and the Zα domain of E3L

The IFN response is a powerful host response against pathogens. VACV encodes many immune evasion genes including those that neutralize the cell death pathways (Holler et al., 2000). E3 is a well-established immune modulator that restricts IFN-driven host detection of viral PAMPs. E3 contains a Z-NA binding domain (Zα) that is homologues to the one found in the mammalian RHIM adaptor DAI/ZBP1. VACV that encodes E3 truncation mutants that lack the Zα (VACV-E3LΔ83N) are highly attenuated. In vivo VACV-E3LΔ83N fails to replicate or spread in wt mice. The Zα truncation is complemented in Ifnar−/− mice(White and Jacobs, 2012). VACV-E3LΔ83N is also IFN sensitive in mouse L929 cells (Koehler et al., 2017) and fails to replicate in mouse JC cells (Arndt et al., 2015). IFN sensitivity of VACV-E3LΔ83N in L929 cells and replication in JC cells correlates with loss of Z-NA binding in vitro (Koehler et al., 2017). Similarly, loss of pathogenesis in mice amongst N-terminal mutants of E3 correlates with loss of Z-NA binding (Kim et al., 2003). These findings show that the two cell culture models appear to mimic pathogenesis in mice, as opposed to the transformed 129 MEF model (White and Jacobs, 2012), where IFN-sensitivity is PKR-dependent. In the L929 cells, E3LΔ83N plaque formation is inhibited by 3-10 IU/ml of type I IFN which corresponds to the sensitivity of the most IFN sensitive viruses. IFN-primed L929 cells infected with E3LΔ83N have been observed to round-up, swell and burst between 3 to 6 hpi. Cell death is not reversed by the pan-caspase inhibitor, z-VAD, but is fully reversed by the RIPK3 inhibitor, GSK872. This finding suggests that the death induced by E3LΔ83N in IFN-treated cells is not apoptosis or pyroptosis, which are both caspase dependent, but likely through RIPK3-dependent necropstosis. Consistent with RIP3-dependent necroptotic cell death, VACV-E3LΔ83N infection of IFN-treated cells leads to MLKL phosphorylation and aggregation. This finding along with pathogenesis being fully restored in Ripk3−/− mice shows that an inhibition of necroptosis in mice is likely necessary for VACV pathogenesis.

Of the three known adaptor proteins that can activate RIPK3; TRIF, RIPK1 and ZBP1 only ZBP1 shares homology with E3 (Ha et al., 2008). VACV-induced necroptosis that is primed by IFN was shown to be independent of small molecule RIPK1-specific protein kinase inhibitors such as necrostatins and GSK’963. ZBP1 is not constitutively expressed in L929 cells from ATCC, but is highly IFN-inducible which implicated it as a candidate RIPK3 adaptor and mediator of virus-induced necroptosis (Guo et al., 2018; Sridharan et al., 2017; Thapa et al., 2016; Upton et al., 2012). This was further supported by the restoration of pathogenicity of E3LΔ83N in Zbp1−/− mice (Koehler et al., 2017). Prior work investigating the function of the VACV E3 demonstrate that the Zα of ZBP1 or ADAR-1 can functionally replace the Zα of E3 for pathogenesis in mice (Kim et al., 2003). Pathogenesis in mice correlates with Z-NA binding in vitro, suggesting that the Zα of ZBP1 and E3 can bind to same nucleic acids in infected cells which indicates that ZBP1 and E3 may be competing for binding to the same nucleic acids. Consistent with the hypothesis that E3 and ZBP1 are completing to bind to Z-NA and dictate cell fates, it has recently been shown that VACV-infection leads to the accumulation Z-RNA in the cytosol and coprecipitates with Za-deficient E3 protein. The presence of this Z-RNA is dependent on translation and temporally corresponds with ZBP1-mediated necroptosis in E3LΔ83N infected cells (Manuscript in prep, Koehler, 2020). We hypothesize that in the presence of a fully functional E3 protein, virus-induced Z-form nucleic acid binds to the N-terminus E3 protein to prevent the binding and activation of ZBP1. In E3LΔ83N-infected cells, the proposed mutant E3 protein-RNA complex allows for Z-RNA to associate with the Zα domain of ZBP1 which leads to the activation of this protein. This activation, in turn, leads to the RHIM-dependent binding of ZBP1 to RIPK3 and subsequent phosphorylation/aggregation of MLKL. Consistent with this model, it has been shown that the Zα of either ZBP1 or ADAR1 can replace the Zα of E3 to inhibit necroptosis in IFN-treated infected cells consistent with in vivo work demonstrating rescue of pathogenesis by the Zα domains of either ZBP1 or ADAR1 ((Kim et al., 2003) Manuscript in prep, Koehler, 2020). Inhibition of necroptosis amongst Zα N-terminal alanine substitution point mutants of E3 correlates with the presumed Z-NA binding in vitro (Manuscript in prep, Koehler, 2020). This suggests that VACV must express a functional Zα in order to fully inhibit the induction of necroptosis. In a similar manner, the Zα of ZBP1 appears to be critical for ZBP1-mediated induction of cell death in E3LΔ83N-infected ZBP1 transduced SVECs. This shows that necroptosis induction correlates with a loss of Z-NA binding amongst mutants of E3 as well as Z-NA binding retention in ZBP1 mutants.

While TNF-α-induced, RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis confers protection to the host. E3L Zα prohibits ZBP1 and thereby blocks ZBP1/RIPK3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis. A functioning Zα on E3 is necessary to evade the anti-viral effects of IFNs that promote ZBP1-mediated necroptosis. These two distinct RIPK3-driven responses implicate necroptosis as a critical host defense against VACV that influences viral growth and dissemination in the host.

Poxvirus encoded MLKL homologues inhibit necroptosis

Necroptosis has been suggested to have arisen as an innate immune defense mechanism in response to inhibition of apoptosis by pathogens (Nailwal and Chan, 2019). The significance of necroptosis in the host defense is demonstrated by the conservation of the E3 N-terminal Zα in VACV and the E3 homologues through much of the chordopoxviruses and is further supported by the identification of variety of virus-encoded inhibitors of necroptosis that confer an advantage against host defense (Guo et al., 2018; Koehler et al., 2017; Upton et al., 2010). While necroptosis can be mediated by multiple RHIM contain adaptors, at the core this form of cell death is dependence on two key effectors: RIPK3 and the executioner of necroptosis, MLKL. Most virus-encoded inhibitors of necroptosis target the RHIM containing proteins either by direct RHIM inhibition or sequestering of PAMPs. However, recently several poxviruses have been shown to encode a truncated homolog of MLKL(Petrie et al., 2019). These virus-encoded proteins have sequence similarity to the pseudokinase domain of mammalian MLKL. These viral MLKL (vMLKL) proteins lack the N-terminal 4HB domain that is necessary for pore formation and only encode the pseudokinase domain. This truncation allows the vMLKLs to function as dominant-negative mimics of host MLKL thereby prohibiting necroptosis by sequestering RIPK3. The necroptosis suppression activity of the vMLKLs was identified by the expression these homologs from of BeAn 58058 poxvirus (BAV) and Cotia poxvirus (COTV). Notably this function appears be species specific and has evolved to target precise hosts. Species specificity was observed by the expression of swinepox vMLKL which was unable to inhibit necroptosis in human or mouse cells.

These vMLKLs were identified in several clades of poxvirus, including the avipoxviruses and leporipoxviruses, which lack an E3-like inhibitor of necroptosis, as well as in clades that contain an E3-like inhibitor of necroptosis, including the suipoxvuses and and capripoxviruses that infect deer, goats, pigs, and sheep. Notably these vMLKLs are absent in many poxviruses that encode E3-like proteins including VACV and variola viruses, and the parapox and yatapoxviruses. They are also absent in entomopox viruses (insect infecting poxviuses).

VACV-induced necroptosis and host range

E3LΔ83N has a highly restricted phenotype in IFN-treated L929 cells and in mouse JC cells, however this virus replicates well and is IFN resistant in most human cells in culture. We now know that this is likely due to the lack of RIPK3 expression in many cells including the majority of human cell lines and several mouse cells in culture (Morgan and Kim, 2015). This lack of expression leads to a resistance to the induction of necroptotic cell death. The down-regulation of RIPK3 in these human cell lines may either be a consequence of the lines having been derived from tumors that have evolved resistance to necroptotic cell death (Koo et al., 2015), or have induces as a consequence of maintaining cells in culture conditions. Thus, viruses like E3LΔ83N which replicate only in cells deficient of necroptotic pathways may have promise as oncolytic viruses. In many cell lines, the down-regulation of RIPK3 appears to be due to the methylation of RIPK3 promoters and can be reversed through treatments with agents that lead to the demethylation of DNA (Koo et al., 2015). Likewise, E3LΔ83N infected SV-40 transformed 129 MEFs which are necroptosis-insufficient undergo a PKR-mediated apoptotic pathways (White and Jacobs, 2012) whereas primary MEFs that express both RIPK3 and ZBP1 die by necroptosis independent of PKR. Thus, the outcomes of E3LΔ83N infection are dependent on the phenotype of the cells infected. These outcomes include replication similar to wtVACV (Langland and Jacobs, 2004), the activation of PKR and subsequent inhibition of viral protein synthesis (White and Jacobs, 2012), and the induction of rapid necroptotic cell death (Koehler et al., 2017). Despite the variability in the consequences of E3LΔ83N-infection in culture cells, pathogenesis due to E3LΔ83N infection in mice is fully restored in Ripk3−/− and Zbp1−/− mice (Koehler et al., 2017), which indicates that the players shown to be important for induction of VACV-induced necroptosis in vitro are also important in decreasing E3LΔ83N pathogenesis in mice.

CONCLUSION

Poxviruses have invested substantial resources in the inhibition of programmed cell death by the host, highlighting the importance of cell death in the arms race between hosts and pathogens. Caspase-dependent cell death appears to be the default host cell death pathway, and numerous poxviral genes have been identified that inhibit caspase-dependent cell death. However, inhibition of caspase-dependent cell death sensitizes cells to MLKL-dependent necroptotic cell death. Thus, poxviruses have evolved at least two mechanisms to inhibit necroptotic cell death, encoding a DAI/ZBP1 antagonist, E3 protein, and/or an MLKL antagonist. For at least E3, antagonism of necroptosis is important for poxviral resistance to interferon, both in cells in culture and in animal models, and for pathogenesis in animal models. Thus, inhibition of necroptosis appears to be an important means for viruses to maintain an edge in the arms race between viruses and their hosts.

Figure. 1.

Inhibition of caspase-dependent cell death by VACV proteins. The apoptosome that contains pro-caspase-9 is formed in response to cytochrome c signal from the mitochondrion and subsequently activates the executioner caspases 3 and 7. Activation of the BH3 such as Bid and Bad proteins leads to a conformational change in the effectors Bax and Bak ultimately resulting in mitochondrial membrane permeability. VACV protein F1 blocks this by blocking Bim, Bak and caspase-9. The VACV N1 bocks the intrinsic death by blocking Bad and Bid. Intrinsic death can also be mediated by the mitochondrion independent of the BH3 proteins due to environmental changes such as increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+ release from the ER and Golgi apparatus. These changes lead to Bax/Bak activation. Some VACV strains regulate this by expressing a channel-like protein vGAAP that depletes intracellular stores of Ca2+. Extrinsic signals also trigger the activation of caspase-3 and −7 via the death receptor signaling leading to the activation of caspase-8 . VACV proteins B13 and B22 restrict caspase-8 by acting as a pan caspase inhibitor. Viral infections can also activate inflammasomes and activation of caspase-1. VACV can block pyroptosis by B13 that acts as a pan-caspase inhibitor and counter the action of caspase-1. F1 can also inhibit the the NLRP1 inflammasome blocking the upstream activation of caspase-1.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of necroptosis cell death by poxvirus proteins. Necroptosis is known to occur following extracellular signaling through death domain containing receptors or by intracellular sensing or PAMPS or DAMPS. Activation of either extracellular and intracellular necroptosis pathways restrict VACV. Under normal conditions necroptosis is kept in check by caspsase-8 cleavage of RIPK3. Cytokine-mediated necroptosis occurs in VACV infected cells that express the pan-caspase inhibitor B13. Signaling then leads to activation of RIPK1 which acts as a RHIM containing adaptor for the downstream activation of RIPK3 and subsequent activation of the necroptosis executer, MLKL. This activation then leads to oligomerization and transmigration of MLKL to the membrane forming pores. Necroptosis can also be unleashed by the pathogen sensor ZBP1. VACV transcription leads to the accumulation of cytoplasmic Z-RNA that is sensed by ZBP1. The virulence factor, E3 blocks this sensing when the VACV-E3Zα is present. In the absence of the VACV-E3Zα (E3ΔZα) exposes the Z-RNA. Sensing by ZBP1 results in the activation of RIPK3 and MLKL. Some poxvirus strains encode a truncated viral homologue of the host MLKL that competitively blocks that activation of MLKL and subsequently inhibits death.

Abbreviations:

- AIM2

absent in melanoma 2

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- ASC

apoptosis-associated speck like proteins

- BH3

Bcl-2 homology domain 3

- CARD

caspase activation and recruitment domain

- DAMPs

damage associate molecular patterns

- DNA

deoxy-ribose nucleic acid

- dsRNA

double-stranded RNA

- PKR

double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase

- eIF2α

eukaryotic initiation factor 2

- GSDM

gasdermin

- vGAAP

golgi anti-apoptotic protein

- Mx1

GTPase myxovirus resistance 1

- hpi

hours post infection

- ISG

IFN-stimulated gene

- ISGF3

IFN-stimulated gene factor 3

- ISG15

IFN-stimulated protein of 15 kDa

- IL

Interleukin

- JAK

Janus kinase

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MLKL

mixed lineage kinase-like

- MEF

Mouse embryo fibroblasts

- NLR

NOD-like receptor

- NOD

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- PAMPs

pathogen associated molecular patterns

- PRRs

pattern recognition receptors

- PK

protein kinase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RIPK

receptor interacting protein kinase

- RNase

ribonuclease

- RHIM

RIP homotypic interaction motif

- Serpins

serine protease inhibitors

- ssRNA

single-stranded ribose nucleic acid

- TMBIM

transmembrane Bax inhibitor-1 motif

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- IFN

type-I interferon

- VACV

Vaccinia virus

- Wt

Wild type

- Z-NA

Z-form nucleic acid

- Zα

Z-nucleic acid binding domain

- ZBP1

Z-nucleic acid binding protein 1

References

- Akira S, Uematsu S, and Takeuchi O (2006). Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124, 783–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali AN, Turner PC, Brooks MA, and Moyer RW (1994). The SPI-1 gene of rabbitpox virus determines host range and is required for hemorrhagic pock formation. Virology 202, 305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsharifi M, Mullbacher A, and Regner M (2008). Interferon type I responses in primary and secondary infections. Immunol Cell Biol 86, 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt WD, Cotsmire S, Trainor K, Harrington H, Hauns K, Kibler KV, Huynh TP, and Jacobs BL (2015). Evasion of the Innate Immune Type I Interferon System by Monkeypox Virus. J Virol 89, 10489–10499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt WD, White SD, Johnson BP, Huynh T, Liao J, Harrington H, Cotsmire S, Kibler KV, Langland J, and Jacobs BL (2016). Monkeypox virus induces the synthesis of less dsRNA than vaccinia virus, and is more resistant to the anti-poxvirus drug, IBT, than vaccinia virus. Virology 497, 125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J, Pan G, Poncz M, Wei J, Ran M, and Zhou Z (2018). Serpin functions in host-pathogen interactions. PeerJ 6, e4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie E, Denzler KL, Tartaglia J, Perkus ME, Paoletti E, and Jacobs BL (1995). Reversal of the interferon-sensitive phenotype of a vaccinia virus lacking E3L by expression of the reovirus S4 gene. J Virol 69, 499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie E, Kauffman EB, Martinez H, Perkus ME, Jacobs BL, Paoletti E, and Tartaglia J (1996). Host-range restriction of vaccinia virus E3L-specific deletion mutants. Virus Genes 12, 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, and Cookson BT (2009). Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol 7, 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best SM (2008). Viral subversion of apoptotic enzymes: escape from death row. Annu Rev Microbiol 62, 171–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluyssen AR, Durbin JE, and Levy DE (1996). ISGF3 gamma p48, a specificity switch for interferon activated transcription factors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 7, 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonjardim CA, Ferreira PC, and Kroon EG (2009). Interferons: signaling, antiviral and viral evasion. Immunol Lett 122, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher D, Monteleone M, Coll RC, Chen KW, Ross CM, Teo JL, Gomez GA, Holley CL, Bierschenk D, Stacey KJ, et al. (2018). Caspase-1 self-cleavage is an intrinsic mechanism to terminate inflammasome activity. J Exp Med 215, 827–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie AG, and Unterholzner L (2008). Viral evasion and subversion of pattern-recognition receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 8, 911–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt T, Heck MC, Vijaysri S, Jentarra GM, Cameron JM, and Jacobs BL (2005). The N-terminal domain of the vaccinia virus E3L-protein is required for neurovirulence, but not induction of a protective immune response. Virology 333, 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt TA, and Jacobs BL (2001). Both carboxy- and amino-terminal domains of the vaccinia virus interferon resistance gene, E3L, are required for pathogenesis in a mouse model. J Virol 75, 850–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley MM, and Fish EN (2002). Review: IFN-alpha/beta receptor interactions to biologic outcomes: understanding the circuitry. J Interferon Cytokine Res 22, 835–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks MA, Ali AN, Turner PC, and Moyer RW (1995). A rabbitpox virus serpin gene controls host range by inhibiting apoptosis in restrictive cells. J Virol 69, 7688–7698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron C, Hota-Mitchell S, Chen L, Barrett J, Cao JX, Macaulay C, Willer D, Evans D, and McFadden G (1999). The complete DNA sequence of myxoma virus. Virology 264, 298–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrara G, Saraiva N, Gubser C, Johnson BF, and Smith GL (2012). Six-transmembrane topology for Golgi anti-apoptotic protein (GAAP) and Bax inhibitor 1 (BI-1) provides model for the transmembrane Bax inhibitor-containing motif (TMBIM) family. J Biol Chem 287, 15896–15905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan FK, Shisler J, Bixby JG, Felices M, Zheng L, Appel M, Orenstein J, Moss B, and Lenardo MJ (2003). A role for tumor necrosis factor receptor-2 and receptor-interacting protein in programmed necrosis and antiviral responses. J Biol Chem 278, 51613–51621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HW, and Jacobs BL (1993). Identification of a conserved motif that is necessary for binding of the vaccinia virus E3L gene products to double-stranded RNA. Virology 194, 537–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HW, Uribe LH, and Jacobs BL (1995). Rescue of vaccinia virus lacking the E3L gene by mutants of E3L. J Virol 69, 6605–6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HW, Watson JC, and Jacobs BL (1992). The E3L gene of vaccinia virus encodes an inhibitor of the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89, 4825–4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M, and Chan FK (2009). Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137, 1112–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooray S, Bahar MW, Abrescia NG, McVey CE, Bartlett NW, Chen RA, Stuart DI, Grimes JM, and Smith GL (2007). Functional and structural studies of the vaccinia virus virulence factor N1 reveal a Bcl-2-like anti-apoptotic protein. J Gen Virol 88, 1656–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JE Jr., Kerr IM, and Stark GR (1994). Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264, 1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Veer MJ, Holko M, Frevel M, Walker E, Der S, Paranjape JM, Silverman RH, and Williams BR (2001). Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays. J Leukoc Biol 69, 912–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der SD, Zhou A, Williams BR, and Silverman RH (1998). Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 15623–15628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueck KJ, Hu YS, Chen P, Deschambault Y, Lee J, Varga J, and Cao J (2015). Mutational analysis of vaccinia virus E3 protein: the biological functions do not correlate with its biochemical capacity to bind double-stranded RNA. J Virol 89, 5382–5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprez L, Wirawan E, Vanden Berghe T, and Vandenabeele P (2009). Major cell death pathways at a glance. Microbes Infect 11, 1050–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitz Ferrer P, Potthoff S, Kirschnek S, Gasteiger G, Kastenmuller W, Ludwig H, Paschen SA, Villunger A, Sutter G, Drexler I, et al. (2011). Induction of Noxa-mediated apoptosis by modified vaccinia virus Ankara depends on viral recognition by cytosolic helicases, leading to IRF-3/IFN-beta-dependent induction of pro-apoptotic Noxa. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink SL, Bergsbaken T, and Cookson BT (2008). Anthrax lethal toxin and Salmonella elicit the common cell death pathway of caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis via distinct mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 4312–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink SL, and Cookson BT (2007). Pyroptosis and host cell death responses during Salmonella infection. Cell Microbiol 9, 2562–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Comella N, Tognazzi K, Brown LF, Dvorak HF, and Kocher O (1999). Cloning of DLM-1, a novel gene that is up-regulated in activated macrophages, using RNA differential display. Gene 240, 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Dostert C, Hannesschlager N, Endres S, Hartmann G, Tardivel A, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, et al. (2009). Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature 459, 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubser C, Bergamaschi D, Hollinshead M, Lu X, van Kuppeveld FJ, and Smith GL (2007). A new inhibitor of apoptosis from vaccinia virus and eukaryotes. PLoS Pathog 3, e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Gilley RP, Fisher A, Lane R, Landsteiner VJ, Ragan KB, Dovey CM, Carette JE, Upton JW, Mocarski ES, et al. (2018). Species-independent contribution of ZBP1/DAI/DLM-1-triggered necroptosis in host defense against HSV1. Cell Death Dis 9, 816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha SC, Kim D, Hwang HY, Rich A, Kim YG, and Kim KK (2008). The crystal structure of the second Z-DNA binding domain of human DAI (ZBP1) in complex with Z-DNA reveals an unusual binding mode to Z-DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 20671–20676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig R, and Broz P (2018). Function and mechanism of the pyrin inflammasome. Eur J Immunol 48, 230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, Thome M, Attinger A, Valitutti S, Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Seed B, and Tschopp J (2000). Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol 1, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, and Latz E (2008). Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol 9, 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough RF, and Bass BL (1994). Purification of the Xenopus laevis double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase. J Biol Chem 269, 9933–9939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttmann J, Krause E, Schommartz T, and Brune W (2015). Functional Comparison of Molluscum Contagiosum Virus vFLIP MC159 with Murine Cytomegalovirus M36/vICA and M45/vIRA Proteins. J Virol 90, 2895–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs A, and Lindenmann J (1957). Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 147, 258–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Langland JO, Kibler KV, Denzler KL, White SD, Holechek SA, Wong S, Huynh T, and Baskin CR (2009). Vaccinia virus vaccines: past, present and future. Antiviral Res 84, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JB, and McFadden G (2003). Poxvirus immunomodulatory strategies: current perspectives. J Virol 77, 6093–6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen I, and Miao EA (2015). Pyroptotic cell death defends against intracellular pathogens. Immunol Rev 265, 130–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, and Mocarski ES (2013). Viral modulation of programmed necrosis. Curr Opin Virol 3, 296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti TD, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Whitfield J, Franchi L, Taraporewala ZF, Miller D, Patton JT, Inohara N, et al. (2006a). Critical role for Cryopyrin/Nalp3 in activation of caspase-1 in response to viral infection and double-stranded RNA. J Biol Chem 281, 36560–36568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Franchi L, Whitfield J, Barchet W, Colonna M, Vandenabeele P, et al. (2006b). Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature 440, 233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande Walle L, Louie S, Dong J, Newton K, Qu Y, Liu J, Heldens S, et al. (2011). Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479, 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr IM, Brown RE, and Hovanessian AG (1977). Nature of inhibitor of cell-free protein synthesis formed in response to interferon and double-stranded RNA. Nature 268, 540–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavardhana S, and Kanneganti TD (2017). Mechanisms governing inflammasome activation, assembly and pyroptosis induction. Int Immunol 29, 201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavardhana S, Malireddi RKS, and Kanneganti TD (2020). Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Pyroptosis. Annu Rev Immunol 38, 567–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibler KV, Shors T, Perkins KB, Zeman CC, Banaszak MP, Biesterfeldt J, Langland JO, and Jacobs BL (1997). Double-stranded RNA is a trigger for apoptosis in vaccinia virus-infected cells. J Virol 71, 1992–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U, Garner TL, Sanford T, Speicher D, Murray JM, and Nishikura K (1994). Purification and characterization of double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase from bovine nuclear extracts. J Biol Chem 269, 13480–13489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YG, Muralinath M, Brandt T, Pearcy M, Hauns K, Lowenhaupt K, Jacobs BL, and Rich A (2003). A role for Z-DNA binding in vaccinia virus pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 6974–6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp EW, Irausquin SJ, Friedman R, and Hughes AL (2011). PolyAna: analyzing synonymous and nonsynonymous polymorphic sites. Conserv Genet Resour 3, 429–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler H, Cotsmire S, Langland J, Kibler KV, Kalman D, Upton JW, Mocarski ES, and Jacobs BL (2017). Inhibition of DAI-dependent necroptosis by the Z-DNA binding domain of the vaccinia virus innate immune evasion protein, E3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 11506–11511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo GB, Morgan MJ, Lee DG, Kim WJ, Yoon JH, Koo JS, Kim SI, Kim SJ, Son MK, Hong SS, et al. (2015). Methylation-dependent loss of RIP3 expression in cancer represses programmed necrosis in response to chemotherapeutics. Cell Res 25, 707–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs SB, and Miao EA (2017). Gasdermins: Effectors of Pyroptosis. Trends Cell Biol 27, 673–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kus K, Rakus K, Boutier M, Tsigkri T, Gabriel L, Vanderplasschen A, and Athanasiadis A (2015). The Structure of the Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 ORF112-Zalpha.Z-DNA Complex Reveals a Mechanism of Nucleic Acids Recognition Conserved with E3L, a Poxvirus Inhibitor of Interferon Response. J Biol Chem 290, 30713–30725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Declercq W, Kalai M, Saelens X, and Vandenabeele P (2002). Alice in caspase land. A phylogenetic analysis of caspases from worm to man. Cell Death Differ 9, 358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, and Dixit VM (2010). Manipulation of host cell death pathways during microbial infections. Cell Host Microbe 8, 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langland JO, and Jacobs BL (2004). Inhibition of PKR by vaccinia virus: role of the N- and C-terminal domains of E3L. Virology 324, 419–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latz E, Xiao TS, and Stutz A (2013). Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SB, and Esteban M (1994). The interferon-induced double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase induces apoptosis. Virology 199, 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung S, Qureshi SA, Kerr IM, Darnell JE Jr., and Stark GR (1995). Role of STAT2 in the alpha interferon signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol 15, 1312–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, and Beg AA (2000). Induction of necrotic-like cell death by tumor necrosis factor alpha and caspase inhibitors: novel mechanism for killing virus-infected cells. J Virol 74, 7470–7477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, and Moss B (2016). Opposing Roles of Double-Stranded RNA Effector Pathways and Viral Defense Proteins Revealed with CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Cell Lines and Vaccinia Virus Mutants. J Virol 90, 7864–7879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TK, Zhang YB, Liu Y, Sun F, and Gui JF (2011). Cooperative roles of fish protein kinase containing Z-DNA binding domains and double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase in interferon-mediated antiviral response. J Virol 85, 12769–12780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malireddi RK, Ippagunta S, Lamkanfi M, and Kanneganti TD (2010). Cutting edge: proteolytic inactivation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 by the Nlrp3 and Nlrc4 inflammasomes. J Immunol 185, 3127–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O'Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, Lee WP, Weinrauch Y, Monack DM, and Dixit VM (2006). Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature 440, 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Agostini L, Meylan E, and Tschopp J (2004). Identification of bacterial muramyl dipeptide as activator of the NALP3/cryopyrin inflammasome. Curr Biol 14, 1929–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, and Tschopp J (2006). Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440, 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta N, Enwere EK, Santos TD, Saffran HA, Hazes B, Evans D, Barry M, and Smiley JR (2018). Expression of the Vaccinia Virus Antiapoptotic F1 Protein Is Blocked by Protein Kinase R in the Absence of the Viral E3 Protein. J Virol 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocarski ES, Guo H, and Kaiser WJ (2015). Necroptosis: The Trojan horse in cell autonomous antiviral host defense. Virology 479-480, 160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MJ, and Kim YS (2015). The serine threonine kinase RIP3: lost and found. BMB Rep 48, 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss B (2007). Poxviridade: The viruses and their replication, Vol 2, 5 edn. [Google Scholar]

- Moss B, and Shisler JL (2001). Immunology 101 at poxvirus U: immune evasion genes. Seminars in immunology 13, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nailwal H, and Chan FK (2019). Necroptosis in anti-viral inflammation. Cell Death Differ 26, 4–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikura K, Yoo C, Kim U, Murray JM, Estes PA, Cash FE, and Liebhaber SA (1991). Substrate specificity of the dsRNA unwinding/modifying activity. EMBO J 10, 3523–3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogusa S, Thapa RJ, Dillon CP, Liedmann S, Oguin TH 3rd, Ingram JP, Rodriguez DA, Kosoff R, Sharma S, Sturm O, et al. (2016). RIPK3 Activates Parallel Pathways of MLKL-Driven Necroptosis and FADD-Mediated Apoptosis to Protect against Influenza A Virus. Cell Host Microbe 20, 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick D, Cohen B, and Rubinstein M (1994). The human interferon alpha/beta receptor: characterization and molecular cloning. Cell 77, 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell MA, and Keller W (1994). Purification and properties of double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from calf thymus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91, 10596–10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto S, Guo H, Talekar GR, Roback L, Kaiser WJ, and Mocarski ES (2015). Suppression of RIP3-dependent necroptosis by human cytomegalovirus. J Biol Chem 290, 11635–11648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JB, and Samuel CE (1995). Expression and regulation by interferon of a double-stranded-RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from human cells: evidence for two forms of the deaminase. Mol Cell Biol 15, 5376–5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JB, Thomis DC, Hans SL, and Samuel CE (1995). Mechanism of interferon action: double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from human cells is inducible by alpha and gamma interferons. Virology 210, 508–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie EJ, Sandow JJ, Lehmann WIL, Liang LY, Coursier D, Young SN, Kersten WJA, Fitzgibbon C, Samson AL, Jacobsen AV, et al. (2019). Viral MLKL Homologs Subvert Necroptotic Cell Death by Sequestering Cellular RIPK3. Cell Rep 28, 3309–3319 e3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam VA, Jiang Z, Waggoner SN, Sharma S, Cole LE, Waggoner L, Vanaja SK, Monks BG, Ganesan S, Latz E, et al. (2010). The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat Immunol 11, 395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebouillat D, and Hovanessian AG (1999). The human 2',5'-oligoadenylate synthetase family: interferon-induced proteins with unique enzymatic properties. J Interferon Cytokine Res 19, 295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed KD, Melski JW, Graham MB, Regnery RL, Sotir MJ, Wegner MV, Kazmierczak JJ, Stratman EJ, Li Y, Fairley JA, et al. (2004). The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere. N Engl J Med 350, 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenburg S, Deigendesch N, Dittmar K, Koch-Nolte F, Haag F, Lowenhaupt K, and Rich A (2005). A PKR-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha kinase from zebrafish contains Z-DNA binding domains instead of dsRNA binding domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 1602–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler AJ, and Williams BR (2008). Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol 8, 559–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens X, Festjens N, Vande Walle L, van Gurp M, van Loo G, and Vandenabeele P (2004). Toxic proteins released from mitochondria in cell death. Oncogene 23, 2861–2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CE (2001). Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin Microbiol Rev 14, 778–809, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, and Tschopp J (2010). The inflammasomes. Cell 140, 821–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen GC (2001). Viruses and interferons. Annu Rev Microbiol 55, 255–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchelkunov SN, Totmenin AV, Safronov PF, Mikheev MV, Gutorov VV, Ryazankina OI, Petrov NA, Babkin IV, Uvarova EA, Sandakhchiev LS, et al. (2002). Analysis of the monkeypox virus genome. Virology 297, 172–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Gao W, Ding J, Li P, Hu L, and Shao F (2014). Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature 514, 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisler JL, and Moss B (2001). Immunology 102 at poxvirus U: avoiding apoptosis. Semin Immunol 13, 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors ST, Beattie E, Paoletti E, Tartaglia J, and Jacobs BL (1998). Role of the vaccinia virus E3L and K3L gene products in rescue of VSV and EMCV from the effects of IFN-alpha. J Interferon Cytokine Res 18, 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GL, Benfield CTO, Maluquer de Motes C, Mazzon M, Ember SWJ, Ferguson BJ, and Sumner RP (2013). Vaccinia virus immune evasion: mechanisms, virulence and immunogenicity. J Gen Virol 94, 2367–2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan H, Ragan KB, Guo H, Gilley RP, Landsteiner VJ, Kaiser WJ, and Upton JW (2017). Murine cytomegalovirus IE3-dependent transcription is required for DAI/ZBP1-mediated necroptosis. EMBO Rep 18, 1429–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR (2007). How cells respond to interferons revisited: from early history to current complexity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 18, 419–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart TL, Wasilenko ST, and Barry M (2005). Vaccinia virus F1L protein is a tail-anchored protein that functions at the mitochondria to inhibit apoptosis. J Virol 79, 1084–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X, et al. (2012). Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148, 213–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Yin J, Starovasnik MA, Fairbrother WJ, and Dixit VM (2002). Identification of a novel homotypic interaction motif required for the phosphorylation of receptor-interacting protein (RIP) by RIP3. J Biol Chem 277, 9505–9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur M, Seo EJ, and Dever TE (2014). Variola virus E3L Zalpha domain, but not its Z-DNA binding activity, is required for PKR inhibition. RNA 20, 214–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa RJ, Ingram JP, Ragan KB, Nogusa S, Boyd DF, Benitez AA, Sridharan H, Kosoff R, Shubina M, Landsteiner VJ, et al. (2016). DAI Senses Influenza A Virus Genomic RNA and Activates RIPK3-Dependent Cell Death. Cell Host Microbe 20, 674–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry NA, and Lazebnik Y (1998). Caspases: enemies within. Science 281, 1312–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tome AR, Kus K, Correia S, Paulo LM, Zacarias S, de Rosa M, Figueiredo D, Parkhouse RM, and Athanasiadis A (2013). Crystal structure of a poxvirus-like zalpha domain from cyprinid herpesvirus 3. J Virol 87, 3998–4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, and Chan FK (2014). Staying alive: cell death in antiviral immunity. Mol Cell 54, 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, and Mocarski ES (2008). Cytomegalovirus M45 cell death suppression requires receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic interaction motif (RHIM)-dependent interaction with RIP1. J Biol Chem 283, 16966–16970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, and Mocarski ES (2010). Virus inhibition of RIP3-dependent necrosis. Cell Host Microbe 7, 302–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, and Mocarski ES (2012). DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe 11, 290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uze G, Lutfalla G, and Gresser I (1990). Genetic transfer of a functional human interferon alpha receptor into mouse cells: cloning and expression of its cDNA. Cell 60, 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyer DL, Carrara G, Maluquer de Motes C, and Smith GL (2017). Vaccinia virus evasion of regulated cell death. Immunol Lett 186, 68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyer DL, Maluquer de Motes C, Sumner RP, Ludwig L, Johnson BF, and Smith GL (2014). Analysis of the anti-apoptotic activity of four vaccinia virus proteins demonstrates that B13 is the most potent inhibitor in isolation and during viral infection. J Gen Virol 95, 2757–2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H, Wang K, and Shao F (2017). Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature 547, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasilenko ST, Banadyga L, Bond D, and Barry M (2005). The vaccinia virus F1L protein interacts with the proapoptotic protein Bak and inhibits Bak activation. J Virol 79, 14031–14043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]