Abstract

Recent studies have characterized a dominant clone (Clone 1) of Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense (M. massiliense) associated with high prevalence in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients, pulmonary outbreaks in the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK), and a Brazilian epidemic of skin infections. The prevalence of Clone 1 in non-CF patients in the US and the relationship of sporadic US isolates to outbreak clones are not known. We surveyed a reference US Mycobacteria Laboratory and a US biorepository of CF-associated Mycobacteria isolates for Clone 1. We then compared genomic variation and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mutations between sporadic non-CF, CF, and outbreak Clone 1 isolates. Among reference lab samples, 57/147 (39%) of patients with M. massiliense had Clone 1, including pulmonary and extrapulmonary infections, compared to 11/64 (17%) in the CF isolate biorepository. Core and pan genome analyses revealed that outbreak isolates had similar numbers of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and accessory genes as sporadic US Clone 1 isolates. However, pulmonary outbreak isolates were more likely to have AMR mutations compared to sporadic isolates. Clone 1 isolates are present among non-CF and CF patients across the US, but additional studies will be needed to resolve potential routes of transmission and spread.

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Evolution, Genetics, Microbiology, Diseases

Introduction

Mycobacterium abscessus is currently divided into three subspecies including subsp. abscessus, subsp. massiliense and subsp. bolletii1. Closely related strains of Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense (hereafter M. massiliense) were identified from three widely separated outbreaks by comparative genomics2. The outbreaks included cystic fibrosis (CF) related pulmonary isolates from a hospital in the United Kingdom (UK)3, CF pulmonary isolates from a United States (US) clinic4,5, and isolates associated with an epidemic of soft tissue infections in Brazil6,7. Very few non-outbreak related strains were identified in the study. The authors recommended screening all CF isolates for relatedness to these outbreak strains and suggested a multi locus sequence typing (MLST) method including two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the rpoB gene and a SNP in the secA1 gene.

A subsequent global population study using whole genome sequencing (WGS) revealed that the genetic subtype described among the widely separated outbreaks2 (hereafter called Clone 1) was the most prevalent M. massiliense genotype, or dominant circulating clone, among CF patients across several countries in Europe, Australia and one site in the US8. Dominant clones were found to have higher proportions of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mutations to amikacin and clarithromycin compared to diverse, unclustered isolates. In contrast, a population genomics study by the Colorado Research and Development Program (CO-RDP) of M. massiliense isolates from US CF centers across 14 states showed that Clone 1 was not the most prevalent genotype (in only 17% of subjects) and that AMR mutations were relatively rare9. A genomic analysis of 188 M. massiliense isolates from soft tissue infections across 10 Brazilian states confirmed that the Brazilian strains are closely related to Clone 1 strains from the UK pulmonary outbreak10. However, they appeared to be a unique lineage with smaller genomes than other M. massiliense and contained distinct plasmids called pMAB0111 and pMAB0210. It is currently unknown if Clone 1 is present among non-CF pulmonary isolates or extrapulmonary infections outside of Brazil.

For this study, consecutive non-CF and CF clinical isolates of M. abscessus, including subsp. abscessus, subsp. massiliense and subsp. bolletii, were identified over a 3-year period at the Mycobacteria/Nocardia Research Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler (UTHSCT), a national reference laboratory for nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Isolates of M. massiliense were screened by MLST for sequence characteristics of the Clone 1 genotype, and selected isolates were analyzed by WGS. Non-CF and CF M. massiliense isolates with the MLST profile from a second US site, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center, were also analyzed by WGS. Isolates sequenced for this study (n = 34) were analyzed along with previously sequenced US CF isolates from the CO-RDP (n = 41) and isolates from 11 published studies (n = 25) to compare sporadic US isolates from various clinical settings to known outbreak isolates. Our objectives were to (1) test whether Clone 1 isolates exist in non-CF populations in the US and (2) compare the prevalence of Clone 1 between the UTHSCT and CO-RDP isolate cohorts. Moreover, we hypothesize that sporadic US Clone 1 isolates will differ from previously identified outbreak isolates of M. massiliense in terms of genomic similarity and antimicrobial resistance.

Materials and methods

Study population

For the UTHSCT samples, the study protocol was submitted to the human subjects committee at the UTHSCT and was deemed exempt from patient informed consent given the de-identification of all isolates in the study. For NIH samples, patients were enrolled in Institutional Review Board-approved protocols at the National Institutes of Health. For CO-RDP samples, the study was reviewed and approved by the National Jewish Health (NJH) Institutional Review Board (HB-0063). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Species identification and subtyping of M. massiliense isolates at the UTHSCT

The Mycobacteria/Nocardia Research Laboratory at the UTHSCT is a national reference laboratory for adult and pediatric isolates of NTM. Consecutive isolates submitted between November 2014 and August 2017 for identification to species were screened for isolates of M. massiliense. Isolates of M. abscessus (including subspecies M. massiliense) were first identified to species and subspecies levels by rpoB partial gene sequencing12 and/or erm(41) gene sequencing13,14. Isolates of M. massiliense were further screened as Clone 1 using the SNP signature described previously including the two base pair (bp) substitution of the region 5 rpoB gene sequence of the type strain of M. abscessus ATCC 19977T2. MLST was performed by sequencing the region 5 rpoB gene12, the erm(41) gene14, and the secA1 gene15. A subset of 30 isolates from 25 patients was sent to NJH for WGS including 23 isolates from 23 patients (using the first isolate collected in the 2014–2017 study period). Also included among WGS samples were two longitudinal isolates from one patient, and a set of five longitudinal isolates from one patient. Inclusion criteria for WGS were two SNPs in the rpoB gene (2569 C/T and 2670 T/C) and one SNP in the secA1 gene (821 G/T).

Patients at the UTHSCT

Details of the patients and their isolates were obtained from information provided with laboratory submission. These included age, sex, presence or absence of a diagnosis of CF, underlying disease including nodular bronchiectasis, specimen source, geographical location, and date of isolation. A checkbox for the presence or absence of CF was on the sheet, although the details of their CFTR mutations were not requested.

Subtyping of M. massiliense isolates from the NIH mycobacteriology laboratory

Strains were identified as M. massiliense and further subtyped by partial sequencing of rpoB, hsp65 and secA1 genes16 and a M. abscessus subspecies PCR identification scheme17. A subset of MLST-identified Clone 1 and non-Clone 1 isolates (n = 4) was sent to NJH for WGS. Two were pulmonary isolates from persons with CF. The other two were pulmonary and extrapulmonary isolates from non-CF patients.

Whole genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from bacterial pellets using a method described previously18. Sequencing libraries were prepared with 5 ng of genomic DNA and the Nextera XT Library Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego CA). Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq using 2 × 300 bp paired-end sequencing chemistry. A total of 34 sporadic M. massiliense isolates were sequenced in this study, including 30 isolates from 25 patients at UTHSCT, and 4 isolates from 4 patients at the NIH (Table 1). The sequencing cohort includes pulmonary isolates from patients with and without a CF diagnosis, and extrapulmonary isolates cultured from blood, ear and wounds. The patients resided in 11 states across the US and are not associated with any known outbreaks. Thus, these cases are considered to be sporadic (i.e. epidemiologically unrelated).

Table 1.

M. massiliense isolate cohort for genomic analyses.

| Mycobacteria laboratory | Source, disease | No. isolates (No. patients) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sporadic Clone 1 isolates | |||

| UTHSCT | Pulmonary, CF | 12 (8) | This study |

| UTHSCT | Pulmonary, non-CF | 9 (9) | This study |

| UTHSCT | Extrapulmonary | 4 (4) | This study |

| NIH | Pulmonary, non-CF | 1 | This study |

| NIH | Extrapulmonary | 1 | This study |

| Published Clone 1 isolates | |||

| Papworth, UK, outbreak | Pulmonary, CF | 8 (5) | 3 |

| Seattle, WA, outbreak | Pulmonary, CF | 3 (3) | 2 |

| Global study (UK, Australia, US) | Pulmonary, CF | 6 (6) | 8 |

| Great Ormand Hospital, UK | Pulmonary, CF | 1 | 19 |

| Birmingham, UK | Pulmonary, CF | 1 | 20 |

| CO-RDP | Pulmonary, CF | 12 (9) | 9,21 |

| Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, epidemic | Extrapulmonary | 1 | 22 |

| Para, Brazil, epidemic | Extrapulmonary | 1 | 10 |

| Non-Clone 1 control isolates | |||

| UTHSCT | Pulmonary, CF | 3 (2) | This study |

| UTHSCT | Pulmonary, non-CF | 2 (2) | This study |

| NIH | Pulmonary, CF | 2 (2) | This study |

| CO-RDP | Pulmonary, CF | 29 (25) | 9,21 |

| 5S-0304 | Unknown | 1 | Unpublished |

| Marseille, France—CCUG48898T | Pulmonary, non-CF | 1 | 23 |

| University Malaya, Malaysia—M154 | Pulmonary | 1 | 24 |

| Seoul University, Korea—ASAN50594 | Pulmonary | 1 | 25 |

| Total | 100 (84) | ||

M. massiliense Clone 1 isolates from the CO-RDP CF-NTM collection

A total of 107 M. massiliense isolates from 64 patients were previously analyzed by WGS in a population genomics study by the CO-RDP9. Isolates were collected between 2013 and 2018, and patients were associated with CF facilities in 14 US states. Based on phylogenomic analyses, only 11 of 64 (17%) patients with M. massiliense had Clone 1 isolates in the previous study9. WGS data for a subset of 41 CO-RDP isolates, including Clone1 and non-Clone 1, were included in the current study (Table 1). Clone 1 isolates in the current study include 6 isolates from 6 patients (one isolate per patient) and two isolates per patient from three unique patients. Non-Clone 1 isolates in the current study include 21 isolates from 21 patients (one isolate per patient) and two isolates per patient from four unique patients.

Genomic isolate cohort

In addition to isolates sequenced for this study, existing WGS data for Clone 1 and non-Clone 1 M. massiliense isolates were included in the analysis cohort. These include Clone 1 and non-Clone 1 isolates from 12 previously published studies (Table 1). Clone 1 isolates from known outbreaks include eight isolates from five CF patients at the Papworth Hospital, UK3, three isolates from three CF patients treated at a lung transplant and CF center in Seattle, WA2,4 and two isolates from an epidemic of soft tissue infections in Brazil from Rio de Janeiro6,7,22 and Para10. Clone 1 isolates not related to known outbreaks were included from CF patients in two locations in the UK19,20, three countries from the global M. abscessus population study8, and from US CF centers across 14 states9. Non-Clone 1 M. massiliense isolates with WGS, including the M. massiliense type strain CCUG48898T23, two Asian isolates, and 29 CO-RDP isolates, were added as study controls.

Genomic variant and phylogenetic analyses

M. massiliense genomes (n = 100; Table 1) were compared using a reference based mapping and variant calling approach described previously26 with a few modifications. Raw sequence reads were trimmed using Skewer27. For publicly available assembled genomes, in silico generated reads were created for mapping. Trimmed and in silico-generated reads were mapped to the complete reference M. abscessus genome ATCC19977T28 using Bowtie229. SNPs relative to the reference genome were called with samtools mpileup v1.5 and bcftools v1.3.130. Base calls were filtered based on mapping quality ≥ 20, a minimum read depth of 4× and a minimum of 75% of reads supporting the base. Only genomic positions with complete genotype data for all isolates in the study were included in downstream analyses. A multifasta sequence alignment was created from concatenated base calls and phylogenetic trees were generated using the neighbor joining method and 100 bootstrap replicates with Seaview31. Phylogenetic tree visualizations were created with ggtree32. Pairwise distances of core genome SNPs were estimated between isolates using MEGA33.

AMR SNPs in the 16S rRNA gene for aminoglycoside (amikacin) resistance34 and the 23S rRNA gene for macrolide (clarithromycin) resistance35 were extracted from the genome-wide genotype matrix based on genomic coordinates in the ATCC19977T genome The 16S rRNA A1408G mutation corresponds to genomic position 1,463,772, and 23S mutations 2058/2059 correspond to genomic positions 1,466,477 and 1,466,478. M. massiliense AMR mutation genotypes were compared using Fisher’s exact tests in R 3.4.336.

Pan genome analyses

Trimmed reads were assembled into draft genomes using Unicycler37, and genes were predicted and annotated using Prokka38. For publicly available assembled genomes, genes were also analyzed with the Prokka pipeline to enable consistent gene prediction across all genomes in the dataset. To ensure consistent quality of genome assemblies included in the pan genome analyses, assemblies were compared for overall genome size and number of predicted genes. Genomes with more than two standard deviations from the mean for at least one variable were declared outliers and removed from the analysis. Genome sizes were compared with a t-test in R 3.4.336. Pan genome analyses were performed with Roary39.

Results

Prevalence of the M. massiliense Clone 1 in a mycobacteriology reference laboratory

Between November 2014 and August 2017, a total of 147 patients with isolates of M. massiliense were identified at the UTHSCT. Based on the presence of the two characteristic rpoB mutations and the secA1 mutation previously described2, a total of 114 isolates obtained from 57 patients (22 males, 38.6% and 35 females, 61.4%) belonged to Clone 1. A total of 132 isolates from 90 patients did not have the characteristic mutations in rpoB and secA1 and were classified as non-Clone 1.

Clone 1 isolates were from respiratory sites (50, 87.7%), wounds (6, 10.5%), and blood (1, 1.8%) from 11 states. Of the 50 respiratory isolates, 10 were bronchoscopy samples, three were tracheal aspirates, and one was a lung biopsy. The remaining 36 samples were sputum cultures. Eighteen of the 50 patients submitting respiratory samples (36%) were identified as having CF. The mean age of the 18 confirmed CF patients was 22.5 years (range 10–44 years) while the mean age of the 17 non-confirmed CF (no diagnostic information was available) patients under age 50 was 31.3 years (range 6–49 years). However, based on their age (under age 50), the 17 patients were considered to have a presumptive (non-confirmed) CF diagnosis. The mean age of all respiratory patients over age 50 was 67.6 years (range 52–89 years).

Genomic relationships of M. massiliense isolates

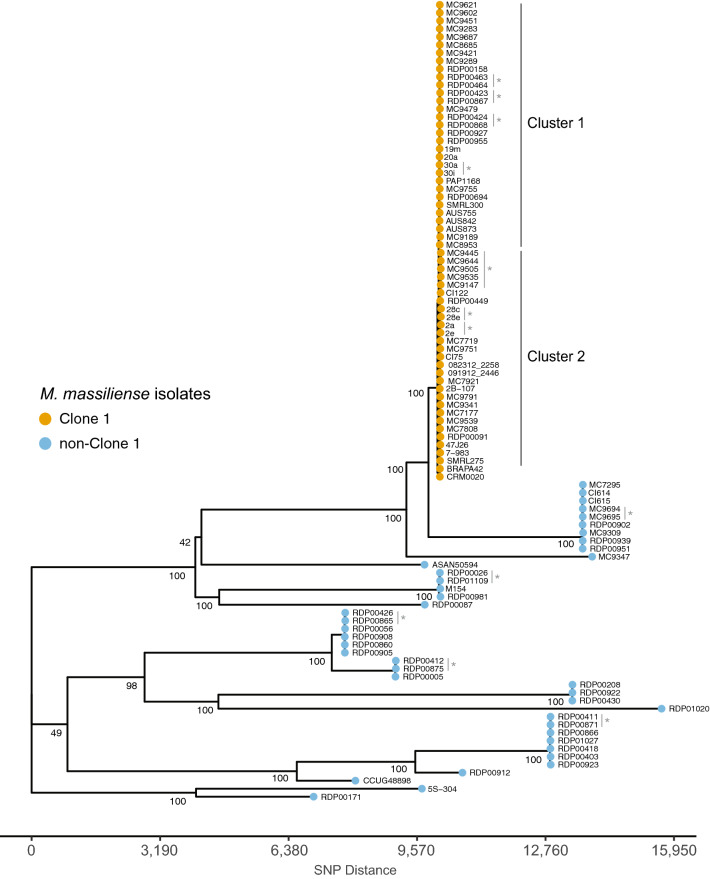

Phylogenomic analyses of all 100 isolates in the study cohort were performed to confirm previously observed relationships of M. massiliense. A phylogenomic tree, derived from 63,841 genome-wide SNP positions, showed a tightly clustered clade of Clone 1 isolates along with several other clades of genetically diverse M. massiliense (Fig. 1). Longitudinal isolates clustered with each other suggesting clonal infections. The placement of the known respiratory outbreak isolates and Brazilian epidemic extrapulmonary strains within the Clone 1 group, and the locations of the type strain, CCUG48898T along with previously described isolates (i.e. ASAN50594 and M154) as more distantly related from Clone 1 suggest a robust phylogeny consistent with previous studies2,3,26,40.

Figure 1.

Phylogenomic analysis of M. massiliense isolates in the study (n = 100). Genome-wide SNP data at 63,841 positions was analyzed using the neighbor-joining algorithm. Bootstrap support values for the basal nodes are shown. The M. massiliense type strain CCUG48898T is included among non-Clone 1 isolates. Longitudinal isolates are shown with grey bars and asterisks. Clusters within the Clone 1 clade are labeled on the right.

Population structure of M. massiliense Clone 1 isolates

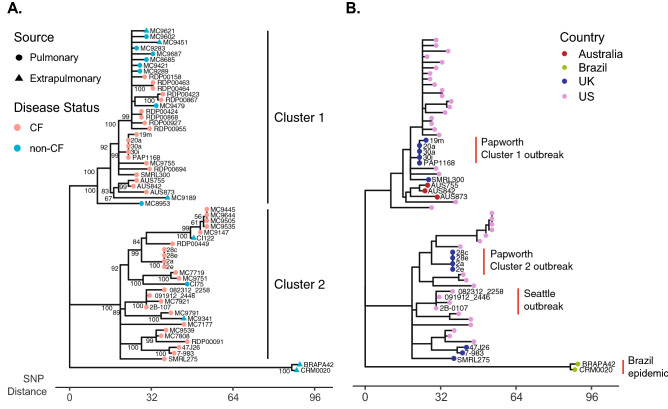

Of the 63,841 variant genomic positions in the full dataset, 564 positions vary among Clone 1 isolates including the two Brazilian isolates. When excluding the Brazilian isolates, only 472 positions vary among Clone 1 isolates (n = 58). A phylogenetic reconstruction of the Clone 1 subgroup shows two distinct lineages, including Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 observed previously in a single-center study from the Papworth Hospital in the UK3 and a subsequent study of the Seattle outbreak2 (Fig. 2A). Isolates from known outbreaks are in the expected clusters including Papworth isolates (19m, 20a, 30a, 30m) in Cluster 13, and Papworth isolates (2a, 2e, 28c, 28e) and Seattle outbreak isolates (2B-0107, 082312_2258, 091912_2446) in Cluster 22 (Fig. 2B). Both clusters include sporadic isolates sequenced in the current study including CF, non-CF and extrapulmonary isolates. Geographically, Cluster 1 includes isolates from the UK, Australia and six US states. Cluster 2 includes isolates from three locations in the UK and eight US states. Temporally, isolates in Cluster 1 were collected between 2001 and 2017, and isolates in cluster 2 were collected between 2005 and 2017. The Brazilian soft tissue isolates group outside of the two Clusters by more than 100 SNPs, and no similar isolates were identified in this study.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of Clone 1 isolates. (A) Phylogenetic reconstruction of Clone 1 isolates (n = 58) and two Brazilian epidemic isolates (n = 2) was generated using core genome SNP data and the neighbor-joining method. Bootstrap support values (> 50%) after 100 replicate searches are shown. Isolates are labeled by sample source and patient disease status. (B) The same phylogeny is labeled by isolate country of origin and previously studied outbreaks are labeled with red bars.

Antimicrobial resistance mutations in M. massiliense and Clone 1 isolates

To assess the prevalence of drug resistance mutations among subgroups of M. massiliense isolates, we evaluated known mutations in the 16S rRNA conferring amikacin resistance and the 23S rRNA for clarithromycin resistance in our genomic isolate cohort. Using one isolate per patient, we first compared Clone 1 (n = 46) vs. non-Clone 1 isolates (n = 38). While we observed higher proportions of AMR mutations in the 16S and 23S rRNAs in Clone 1 compared to non-Clone 1 isolates, they were not statistically significant; amikacin resistance mutation (p = 0.21) and clarithromycin resistance mutations (p = 0.06) (Supplementary Figure 1A).

Next, we compared the prevalence of drug resistance mutations within the Clone 1 subgroup, between isolates from patients associated with pulmonary outbreaks (n = 7) and sporadic isolates (n = 39) and found that drug resistance mutations were significantly higher among outbreak isolates for both amikacin (p = 0.0016) and clarithromycin (p < 0.0001) compared to non-outbreak strains (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Brazilian epidemic isolates do not have these AMR mutations.

Pan genome of M. massiliense Clone 1 isolates

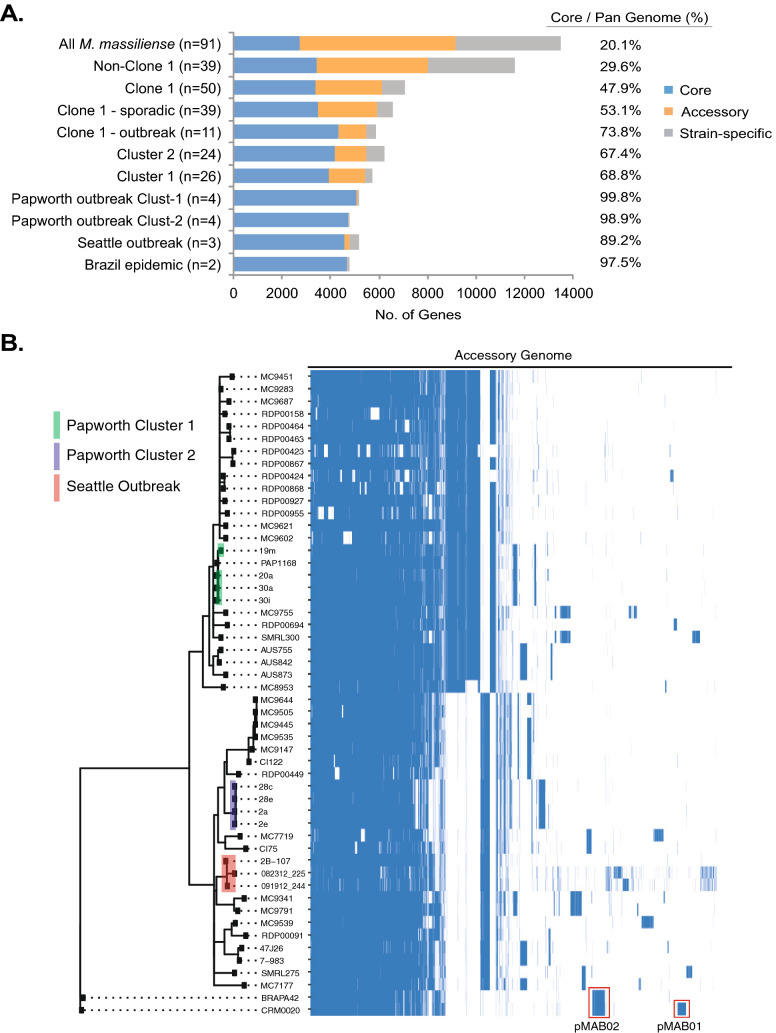

To explore genomic variation beyond the core genome, we performed pan genome comparisons for all M. massiliense that met our genome assembly quality criteria (n = 91). Among the entire genomic dataset, M. massiliense genomes were, on average, 4.98 Mb in size (range 4.7–5.4 Mb) similar to previous studies10,40, with an average of 5011 predicted genes per genome (range 4609–5517). There was no significant difference in average genome size between Clone 1 and non-Clone 1 isolates (t-test, p = 0.68). Using predicted protein coding genes for each genome, we identified gene presence/absence variation among the entire dataset and subsets of isolate genomes (Fig. 3A). Among all isolates (n = 91), the pan genome included 13,460 unique genes of which only 2715 genes made up the core genome shared by all isolates, consistent with previous findings in M. massiliense40. Among the genetically diverse non-Clone 1 isolates (n = 39), the pan genome included 11,583 unique genes with a core genome of 3430 genes (30% core genes). In contrast, the genetically similar Clone 1 isolates (n = 50) had a smaller pan genome of 7041 unique genes and a core genome of 3375 genes (48% core genes).

Figure 3.

Pan genome of M. massiliense. Pan genome analyses were performed for M. massiliense isolates that passed genome assembly quality filters (see “Methods”; n = 91). (A) Pan genome results for all isolates in the dataset and various isolate subgroups are shown as numbers of core genes, accessory genes and strain-specific genes. Percent of core genes for each group is shown (core genes/ total genes in pan genome). (B) Visualization of the accessory genome for Clone 1 M. massiliense isolates. Accessory genes for Clone 1 isolates (n = 50) and Brazilian epidemic isolates (n = 2) are shown as a presence or absence heatmap (blue means presence of a gene). Samples are ordered based on the core genome phylogenetic tree (left side). Known outbreak isolate clades are color coded for reference, and plasmids are indicated with red boxes.

Within Clone 1, isolates in Cluster 1 (n = 26) and Cluster 2 (n = 24) showed pan genomes of 6193 and 5707 genes, with core genomes of 3929 and 4175 genes (69% and 67%), respectively. Clone 1 sporadic isolates (n = 39) had a smaller core genome (53.1%) compared to Clone 1 outbreak isolates (n = 11; 73.8%). Finally, isolate subsets from known pulmonary outbreaks showed highly similar genomes with core genes ranging from 89% (Seattle) to 99% (Papworth Cluster 2). The two Brazilian epidemic isolates had highly similar genomes (97% core genes) and differed only by the presence or absence of the pMAB01 plasmid.

A heatmap of the accessory genome (Fig. 3B) for Clone 1 isolates (n = 50) and Brazilian epidemic isolates (n = 2) revealed the gene presence/absence variation among highly similar isolates by the core genome. The heatmap shows clusters of genes that are specific to Cluster 1 or Cluster 2, in addition to strain-specific genes in various isolates within the clusters. The analysis also identified two plasmids among the Brazilian epidemic isolates, pMAB0111 and pMAB0210, which were absent in the genomes of all other isolates in our study in contrast to a previous study that identified pMAB02 in a small proportion of CF-related pulmonary isolates10.

Outbreak versus sporadic Clone 1 isolates

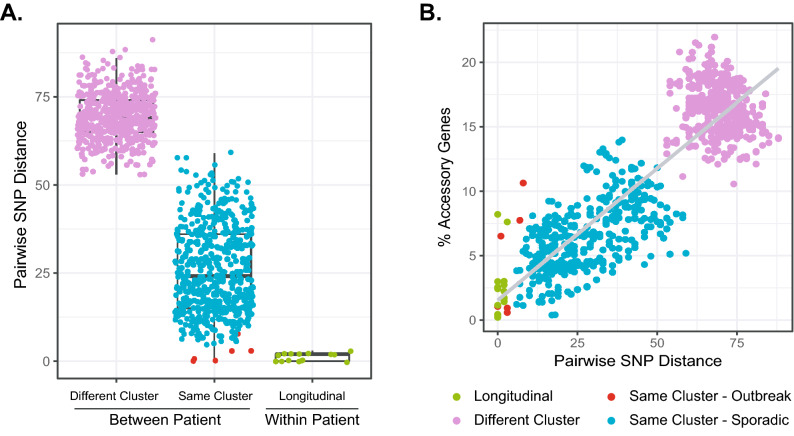

We evaluated thresholds of genomic variation between patient isolates associated with previous outbreaks (one isolate per patient including Brazilian strains; n = 10) versus those classified as sporadic Clone 1 isolates (one isolate per patient; n = 31). As a reference point, pairwise SNP distances between longitudinal same-patient isolate pairs (n = 8 patients) were also calculated (Fig. 4A). Pairwise SNP distances ranged from 0 to 3 SNPs for same-patient isolates, 0–8 SNPs between patients in known outbreaks (Papworth, Seattle and Brazil), 6–59 SNPs between sporadic isolate pairs in the same cluster (Cluster 1 or Cluster 2 as in Fig. 2), and 51–91 SNPs between patient isolates in different clusters (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Pairwise genomic variation among Clone 1 M. massiliense isolates. Pairwise SNP distances were calculated for all Clone 1 isolates in the study (n = 58). (A) Isolate pairs are categorized as between-patient or within-patient. Between patient isolates in the same cluster (Cluster 1 or Cluster 2) are further categorized as belonging to known outbreaks (red) or as sporadic, unrelated isolates (blue). (B) The relationship between accessory gene content for Clone 1 isolate pairs, measured as % accessory genes for each isolate pair (# accessory genes/# of genes in pan genome) and core genome similarity (shown as pairwise SNP distance) is shown as a scatter plot.

To understand the relationship between the core genome (measured by SNPs) and accessory genome variation (measured by gene presence/absence) among highly similar Clone 1 isolates, we compared pairwise SNP distances (Fig. 4A) and % accessory genome variation for all isolate pairs (Fig. 4B). While there is an overall positive relationship between SNP distance and % accessory genome in the population, there is substantial variation in the accessory genome among isolate pairs that are highly similar in the core genome. For example, longitudinal, same-patient isolate pairs had an average of 2.5% accessory genome variation (range 0.2–8.2%; time span range: 2–246 days). Papworth pulmonary outbreak isolates were highly similar and showed 0.6–1.1% accessory genome variation between patients, while the Seattle outbreak isolates showed 6.5–10.6% accessory genome variation between patients. Sporadic isolate pairs that were highly similar at the core genome level (less than 10 SNPs) included CF/CF and non-CF/CF pairs, and showed accessory genome variation of 1.1–6.2% which was well within the range of longitudinal and outbreak isolate thresholds in our study.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the M. massiliense dominant Clone 1 is not limited to the respiratory tract of patients with CF, but is also found in sporadic wound infections, blood stream infections, and the respiratory tract of primarily older women. Clone 1 was identified in multiple states across the US, in two clinical mycobacteriology laboratories, and in a nationwide CF-NTM biorepository9. At the UTHSCT, the prevalence of Clone 1 among all isolates of M. massiliense was surprisingly high compared to the CO-RDP (39% vs. 17%). The difference in prevalence between patient isolates sent to the UTHSCT and CF isolates sent to the CO-RDP may reflect differences in disease states (non-CF vs. CF), geographic distribution of isolates, suspicion of outbreaks, or other sampling biases.

Pan genome analyses showed that M. massiliense has broad diversity in gene content similar to previous studies of M. abscessus40. We observed genes that vary within the Clone 1 lineages, Clusters 1 and 2 (Fig. 3B), illustrating that isolates which appear ‘clonal’ by MLST or core genome analysis also have underlying genomic variation through gene loss and gain26,41. This is consistent with previous observations among highly similar M. abscessus clusters42. While accessory genome variation broadly tracks with core genome (SNP) variation (Fig. 4B), it can vary widely among isolates with highly similar core genomes. For instance, the Papworth outbreak clusters showed very little accessory genome variation (< 2%) while the Seattle outbreak isolates showed more diversity between the index case and other cases (~ 10%). The contrast in genomic variation between outbreak scenarios may reflect in vivo diversification of sublineages in the index case that were subsequently transmitted to other patients. Clonal sublineages within patients have been observed in long-term Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections43,44, and one longitudinal patient in our sample set showed similar accessory genome variation (Fig. 4B). Our results suggest that the pan genome offers additional and useful information for deconstructing relationships between highly similar isolate clusters.

Through this study, we identified highly similar sporadic isolate pairs (< 10 SNPs between patients) including those between CF and non-CF patients and between pulmonary and extrapulmonary isolates. Many of these pairs do not have obvious connections or opportunities for cross infection as patients were from different states and/or separated by months or years of time. This corresponds to findings from the CO-RDP where CF patients from widely separated geographic regions shared highly similar M. abscessus isolates9,21. Genomic studies within single CF centers have largely corroborated these findings through lack of epidemiological evidence for healthcare associated transmission among highly similar isolate clusters19,42,45. This underscores the uncertainty of using genetic similarities alone to presume person-to-person transmission. Epidemiological investigations including environmental sampling are needed in parallel to identify inoculum sources and rule out patient cross transmission.

The rarity of acquired AMR mutations among sporadic US Clone 1 isolates in our study suggests that they could be useful indicators of cross transmission between patients. One interesting observation in our study is a CF patient from the Seattle, WA area that presented to the University of Washington CF Center for the first time in 2012 with an amikacin and clarithromycin resistant isolate. The 2012 isolate clustered with the Seattle CF outbreak cluster by core genome similarity (Fig. 2; MC7921) but the patient had no known contact with the Seattle outbreak cases diagnosed in 2004 and 20054. This suggests the outbreak clone may still exist, perhaps in the local environment, though no additional cases have been identified. The high proportion of AMR mutations observed among outbreak isolates compared to sporadic isolates suggests that they may be fitness factors promoting long term infection and opportunities for cross-infection between patients8. However, additional outbreak isolates would be needed to validate this hypothesis.

While many insights have been gained from our analysis of sporadic US M. massiliense isolates, there are limitations to the study. First, we have a low sample size of known outbreak isolates to compare with sporadic isolates. Second, we have incomplete knowledge of residential history and initial NTM acquisition for patients in the study, and therefore cannot fully evaluate the potential for shared exposure or cross infection. That the dominant clone is found in non-CF and CF settings across the US suggests that it is not specific to CF centers and may be widespread in the environment or man-made systems. Complementary environmental studies are needed to identify precise locations of M. massiliense and other rapidly-growing NTM in the environment.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

RMD was supported by NIH-NIAID K01-AI125726. RMD, NAH, LEE, JAN, CLD and MS were supported by a US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) Research & Development Program Grant (NICK15RO) and CFF National Resource Center Grants (NICK20Y2-SVC, NICK20Y2-OUT). This study was funded in part by the intramural research programs of the NHLBI (KNO) and the Clinical Center (AMZ), NIH. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, writing the manuscript, or decision to publish.

Author contributions

R.M.D., N.A.H., J.A.N., K.N.O., A.M.Z., C.L.D., M.S., R.J.W. conceived and designed the project. N.A.H., S.M.K., L.E.E., T.S., S.V., B.A.B., K.N.O., A.M.Z. acquired the data. R.M.D., J.B.B., S.M.K., N.A.H., T.S., S.V., R.J.W. analyzed the data. R.M.D. and R.J.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Data availability

WGS data generated for this study are available at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under BioProject PRJNA691364.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-94789-y.

References

- 1.Tortoli E, et al. Emended description of Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus and Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii and designation of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. massiliense comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66:4471–4479. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tettelin H, et al. High-level relatedness among Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. massiliense strains from widely separated outbreaks. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:364–371. doi: 10.3201/eid2003.131106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant JM, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2013;381:1551–1560. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60632-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aitken ML, et al. Respiratory outbreak of Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense in a lung transplant and cystic fibrosis center. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012;185:231–232. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.185.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapnadak SG, Hisert KB, Pottinger PS, Limaye AP, Aitken ML. Infection control strategies that successfully controlled an outbreak of Mycobacterium abscessus at a cystic fibrosis center. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016;44:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duarte RS, et al. Epidemic of postsurgical infections caused by Mycobacterium massiliense. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:2149–2155. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00027-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson RM, et al. Phylogenomics of Brazilian epidemic isolates of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii reveals relationships of global outbreak strains. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2013;20:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant JM, et al. Emergence and spread of a human-transmissible multidrug-resistant nontuberculous mycobacterium. Science. 2016;354:751–757. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson RM, et al. Population genomics of Mycobacterium abscessus from United States Cystic Fibrosis Care Centers. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1214OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everall I, et al. Genomic epidemiology of a national outbreak of post-surgical Mycobacterium abscessus wound infections in Brazil. Microb. Genom. 2017;3:e000111. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leao SC, et al. The detection and sequencing of a broad-host-range conjugative IncP-1beta plasmid in an epidemic strain of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adekambi T, Berger P, Raoult D, Drancourt M. rpoB gene sequence-based characterization of emerging non-tuberculous mycobacteria with descriptions of Mycobacterium bolletii sp. nov., Mycobacterium phocaicum sp. nov. and Mycobacterium aubagnense sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006;56:133–143. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nash KA, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ., Jr A novel gene, erm(41), confers inducible macrolide resistance to clinical isolates of Mycobacterium abscessus but is absent from Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1367–1376. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01275-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown-Elliott BA, et al. Utility of sequencing the erm(41) gene in isolates of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus with low and intermediate clarithromycin MICs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:1211–1215. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02950-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zelazny AM, Calhoun LB, Li L, Shea YR, Fischer SH. Identification of Mycobacterium species by secA1 sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:1051–1058. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1051-1058.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zelazny AM, et al. Cohort study of molecular identification and typing of Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium massiliense, and Mycobacterium bolletii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:1985–1995. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01688-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shallom SJ, et al. New rapid scheme for distinguishing the subspecies of the Mycobacterium abscessus group and identifying Mycobacterium massiliense isolates with inducible clarithromycin resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:2943–2949. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01132-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epperson LE, Strong M. A scalable, efficient, and safe method to prepare high quality DNA from mycobacteria and other challenging cells. J Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2020;19:100150. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2020.100150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris KA, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analysis do not provide evidence for cross-transmission of mycobacterium abscessus in a cohort of pediatric cystic fibrosis patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015;60:1007–1016. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan J, Halachev M, Yates E, Smith G, Pallen M. Whole-genome sequence of the emerging pathogen Mycobacterium abscessus strain 47J26. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:549. doi: 10.1128/JB.06440-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasan NA, et al. Population genomics of nontuberculous mycobacteria recovered from United States cystic fibrosis patients. bioRxiv. 2019;6:210. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidson RM, et al. Genome sequence of an epidemic isolate of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00617–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00617-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tettelin H, et al. Genomic insights into the emerging human pathogen Mycobacterium massiliense. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:5450. doi: 10.1128/JB.01200-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choo SW, et al. Annotated genome sequence of Mycobacterium massiliense strain M154, belonging to the recently created taxon Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii comb. nov. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:4778. doi: 10.1128/JB.01043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim B-J, Kim B-R, Hong S-H, Seok S-H, Kook Y-H. Complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium massiliense clinical strain Asan 505945, belonging to the type II genotype. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00429–e513. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00429-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidson RM, et al. Genome sequencing of Mycobacterium abscessus isolates from patients in the United States and comparisons to globally diverse clinical strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:3573–3582. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01144-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang H, Lei R, Ding SW, Zhu S. Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinform. 2014;15:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ripoll F, et al. Non mycobacterial virulence genes in the genome of the emerging pathogen Mycobacterium abscessus. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langmead B, Salzberg S. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map (SAM) format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:221–224. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu G, Smith DK, Zhu H, Guan Y, Lam TTY. ggtree: An R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2017;8:28–36. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prammananan T, et al. A single 16S ribosomal RNA substitution is responsible for resistance to amikacin and other 2-deoxystreptamine aminoglycosides in Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium chelonae. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;177:1573–1581. doi: 10.1086/515328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace RJ, Jr, et al. Genetic basis for clarithromycin resistance among isolates of Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1676–1681. doi: 10.1128/AAC.40.7.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2011).

- 37.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Page AJ, et al. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choo SW, et al. Genomic reconnaissance of clinical isolates of emerging human pathogen Mycobacterium abscessus reveals high evolutionary potential. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4061. doi: 10.1038/srep04061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidson RM. A closer look at the genomic variation of geographically diverse Mycobacterium abscessus clones that cause human infection and disease. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2988. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doyle RM, et al. Cross-transmission is not the source of new Mycobacterium abscessus infections in a multicenter cohort of cystic fibrosis patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;70:1855–1864. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markussen T, et al. Environmental heterogeneity drives within-host diversification and evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MBio. 2014;5:e01592–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01592-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feliziani S, et al. Coexistence and within-host evolution of diversified lineages of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in long-term cystic fibrosis infections. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tortoli E, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus in patients with cystic fibrosis: Low impact of inter-human transmission in Italy. Eur. Respir. J. 2017;50:1602525. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02525-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

WGS data generated for this study are available at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under BioProject PRJNA691364.