Abstract

Background

Osteoporosis affects over half of adults over 50 years worldwide. With an ageing population, osteoporosis, fractures and their associated costs are increasing. Unfortunately, despite effective therapies, many with osteoporosis remain undiagnosed and untreated. Models of care (MoC) to improve outcomes include fracture liaison services, screening, education, and exercise programs, however efficacy for these is mixed. The aim of this study is to summarise MoC in osteoporosis and describe implementation characteristics and evidence for improving outcomes.

Methods

This systematic scoping review identified articles via Ovid Medline and Embase, published in English between 01/01/2009 and 15/06/2021, describing MoC for adults aged ≥18 years with, or at risk of, osteoporosis and / or health professionals caring for this group. All included at least one of clinical, consumer or clinician outcomes, with fractures and bone mineral density (BMD) change the primary clinical outcomes. Exclusion criteria were studies assessing pharmaceuticals or procedures without other interventions, or insufficient operational details. All study designs were included, with no comparator necessary. Title and abstract were reviewed by two reviewers. Full text review and data extraction was performed by these reviewers for 20% of article and, thereafter by a single author. As the review was predominantly descriptive, no comparator statistics were used.

Findings

314 articles were identified describing 289 MoC with fracture liaison services (n=89) and education programs (n=86) predominating. The population had prior fragility fracture in 77 studies, the median (IQR) patient number was 210 (87, 667) and the median (IQR) follow-up duration for outcome assessment was 12 (6, 12·5) months. Fracture reduction was reported by 65 studies, with 16 (37%) graded as high quality, and 19 / 47 studies with a comparator group found a reduction in fractures. BMD change was reported by 73 studies, with 41 finding improved BMD. Implementation characteristics including reach, fidelity and loss to follow-up were under-reported, and consumer and clinician perspectives rare.

Interpretation

This comprehensive review of MoC for osteoporosis demonstrated inconsistent evidence for improving outcomes despite similar types of models. Future studies should include implementation outcomes, consumer and clinician perspectives, and fracture or BMD outcomes with sufficient duration of follow-up. Authors should consider pragmatic trial designs and co-design with clinicians and consumers.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Models of care for improving outcomes for people with, or at risk of, osteoporosis include fracture liaison, screening, education and exercise programs. However, the evidence for improving clinical outcomes is mixed, and there is a paucity of data on the most critical outcome of fracture reduction. We performed a systematic scoping review of models of care for adults with or at risk of osteoporosis, using Ovid Medline and Ovid Embase, of articles published between 01/01/2009–15/06/2021.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the largest review of models of care in osteoporosis. We have provided a comprehensive summary of published evidence and have used a validated system for classifying models of care, which can be replicated in other studies.

Implications of all the available evidence

We suggest future reports on models of care for osteoporosis consider the study design, and inclusion of an appropriate comparison group, provide longitudinal follow-up to allow assessment of fracture reduction, or consider using bone mineral density changes as a surrogate marker for this, and include details of delivery and implementation characteristics, which may assist in scaling models to other settings. Lastly, we suggest the inclusion of consumer or clinician perspectives, as key to the success of complex interventions.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis and low bone mass (osteopenia) is estimated to effect more than 50% of adults aged over 50 years [1,2]. Osteoporosis causes minimal symptoms prior to a fracture, and, in older adults, most fractures are the result of osteoporosis [3,4]. In 2000, 9 million osteoporotic fractures occurred worldwide; the lifetime risk of hip fracture for adults aged 50 years is equivalent to the risk of stroke, and the risk of any major osteoporotic fracture is similar to the risk of cardiovascular disease [5,6]. Morbidity and mortality following fracture is substantial, and recent evidence suggests the burden from osteoporotic fractures is greater than many other non-communicable diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and stroke [5]. The cost to the healthcare system for fractures is large; among six European countries, expenditure on osteoporotic fractures was €37.5 billion in 2017, or up to 6.4% of healthcare expenditure [5].

With an ageing population worldwide, the prevalence of osteoporosis, low bone mass, and osteoporotic fractures is predicted to increase, and by 2040 it is expected that over 300 million people will be at high risk for osteoporotic fracture [7]. Therefore, it is critical that measures are taken to prevent fractures, and ensure that people who suffer a fracture receive appropriate care to prevent recurrent fractures. Unfortunately, a treatment gap exists in osteoporosis, with low screening and treatment rates, and poor adherence to treatment [5,[8], [9], [10]]. Models of care (MoC) can be defined as operationalising how specific care should be delivered to a group of people at a disease, service or systems level [11]. MoC for primary fracture prevention include screening, education initiatives for clinicians and / or consumers, and exercise programs [12–14]. The efficacy of these initiatives is unclear, and may be related to differences in program characteristics, the population studied, and control group used [13,15,16]. The gold standard MoC for secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures is a fracture liaison service (FLS). An FLS employs a dedicated coordinator to identify, inform and assess all patients with an osteoporotic fracture within a health system. Different FLS have been classified as Type A (identify patients, investigate for secondary causes of osteoporosis and initiate appropriate treatment), Type B (identify and investigate, but refer to primary care physician for treatment), Type C (identify and inform patient and their primary care physician) and Type D (identify and inform the patient only) [17]. Reviews of FLS have shown an improvement in dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) screening and treatment rates, which vary by the type of FLS model, being highest for the Type A FLS model [16], [17], [18], [19]. Whilst increased treatment may be presumed to lead to a reduction in refractures due to the known benefits of antiresorptive therapy, adherence to treatment started in an FLS is variable, ranging between 34 and 95% [17]. Indeed, evidence for fracture reduction using an FLS is unclear, limited by study size, an appropriate control group and duration of follow-up [17]. Recently, changes in bone mineral density (BMD) has been proposed as a surrogate marker for fractures for therapeutic trials in osteoporosis, and this may also prove useful for more complex interventions such as FLS [20].

A limitation of published research on osteoporosis MoC is failure to include delivery and implementation characteristics. Operational characteristics for delivery include the frequency, duration and method of contact, the setting, and whether participants are seen individually or in a group. Implementation characteristics include factors such as acceptability, uptake, fidelity, cost and sustainability [21]. Studies of osteoporosis MoC can be viewed as hybrid effectiveness-implementation trials, as they use a targeted implementation strategy (such as education or coordination of care) to try to change behaviour (such as medication initiation, DXA screening) and ultimately improve bone health (reduce fractures or increase BMD). Guidelines exist on designing and reporting on implementation trials, and frameworks such as RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) can be used to assess and compare implementation characteristics in real-world interventions [22], [23], [24]. Differences in implementation characteristics may contribute to variable outcomes between similar MoC, and impact the ability to scale up MoC to other settings.

Despite advances in screening and treatment for osteoporosis, a global increase in fractures in the coming years due to populations ageing is predicted, and so implementing effective models of care is essential [5,25,26]. The aims of this review are to: (i) summarise MoC for people with or at risk of osteoporosis; (ii) outline and compare the implementation characteristics of different MoC; and (iii) compare whether different MoC improve a variety of outcomes including reductions in fractures and increases in BMD. We hope this will assist those people planning, implementing and reporting on osteoporosis interventions in the future.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

A scoping review methodology was chosen to enable a broad overview of MoC that have been trialled in osteoporosis, and to describe the evidence for each of these. The scoping review protocol adhered to the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines for scoping reviews [27]. Inclusion criteria were English language publications, published between 01/01/2009 and 15/06/2021. This date range was chosen to include the most contemporary MoC using currently available technology and therapeutics. All study designs were included. The population was defined as either (i) adults aged ≥18 years with, or at risk of, low bone mineral density with or without fracture; and / or (ii) any health professional, including allied health. The intervention comprised any MoC for osteoporosis. No comparator was necessary for inclusion. Outcomes needed to include at least one of clinical, consumer or clinician outcomes. The primary clinical outcome was fractures; the secondary clinical outcome was increase in BMD. Other outcomes included consumer (medication use and adherence, calcium supplement use / calcium intake, vitamin D supplement use, DXA rates, osteoporosis knowledge, osteoporosis self-efficacy, osteoporosis health beliefs), clinician (prescribing rates for medications and vitamin D, screening rates for DXA, osteoporosis knowledge), health service satisfaction, implementation characteristics and cost. Implementation characteristics were broadly based on the RE-AIM framework [24]-Reach (the proportion of people who participated in the MoC, of those eligible), Effectiveness (outcomes as mentioned), Adoption (where applicable, the proportion of settings / institutions who participated in the MoC, of those invited), Implementation (fidelity to the intervention) and Maintenance (the longest time point reported was included in results). Exclusion criteria were studies assessing individual or combination pharmaceuticals or procedures without other interventions, or insufficient detail provided to specify operational characteristics of the MoC.

A systematic search, based on the selection criteria and combining MeSH terms and text words, was developed for Ovid Medline and translated to Embase (Supplement 1). Hand searching of included articles’ reference lists was also performed. Authors were contacted directly where full-text article could not be retrieved, or to clarify study details. Covidence (www.covidence.org) was used to manage search results, and for abstract and full text review. Two reviewers (AJ, MH) independently reviewed the titles, abstracts and keywords of every article retrieved by the search strategy according to the selection criteria. Full text of the articles were retrieved for further assessment if the information given suggests that the study meets the selection criteria or if there is any doubt regarding eligibility of the article based on the information given in the title and abstract. Full text review and data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers for 20% of articles, to achieve 100% agreement, thereafter performed by a single author (AJ). The study protocol was registered with Joanna Briggs Scoping reviews on 13/11/2019 (Supplement 2), and reporting adhered to the PRISMA-scoping review extension checklist.

2.2. Data analysis

Data extraction was performed in Microsoft Excel 2016. We adapted our data extraction table from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) framework for describing interventions, and a previously published scoping review on low-cost MoC [28,29]. Information collected included general details (title, authors, country, year of publication), participants and number, the MoC implemented, delivery characteristics [28] (contact method, frequency, setting, individual vs group care) and clinical outcomes as mentioned. MoC were categorized according to the Cochrane EPOC taxonomy of delivery arrangements and implementation strategies for health system interventions [30]. We also classified MoC by the primary type of activity, such as fracture liaison services (further classified into Types A to D as per Ganda [17], education, exercise, screening, orthogeriatric services (OGS), or specialist review. Where models were multi-component, the primary activity was listed, followed by the other types. Where a single model, with the same participants, was described by different papers (Eg. different time points or outcomes), results were summarised together. The longest follow up time point reported was included in result tables. Where studies included a comparison group, p values for between groups, was included in results tables. Due to the number of studies included in our review, risk of bias assessment using the SIGN proforma [31], was performed for papers reporting fractures, our primary clinical outcome, only.

Given the primary aim of this review was descriptive, no comparative statistics were used. Categorical data are described as number (percentage, %). Continuous data are described as mean (standard deviation) where normally distributed, and median (interquartile range, IQR) when non-parametric. Studies were summarised (i) overall, and then by outcomes of (ii) fractures and (iii) BMD change.

2.3. Role of the funding source

This study received no direct funding. All authors had full access to the data in the study and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

3. Results

3.1. Overall

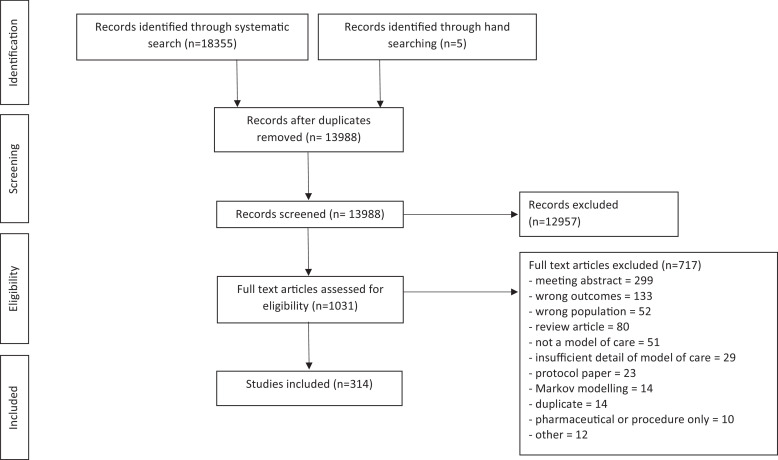

Fig. 1 and Supplement 3 summarises our search strategy, which resulted in 314 articles included which reported on 289 models of care (25 articles were additional follow-up of the same model and participants). The majority of excluded studies at the title and abstract stage reported only on pharmaceuticals / surgical procedures, and at the full text review stage because they were an abstract only or reported the wrong outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Study selection.

Summary data for included studies are shown in Table 1, with complete study details shown in Table S1 and implementation characteristics are in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of included studies.

| Study design n(%) | Randomised trial | 117 (40·5) | |

| Non-randomised trial | 16 (5·5) | ||

| Cohort study | 80 (27·7) | ||

| Case study / series | 38 (13·1) | ||

| Pre-test post-test | 23 (8·0) | ||

| Other | 15 (5·2) | ||

| Type of model of care n(%) | Education | 86 (29·8) | |

| Fracture liaison service | 89 (30·8) | ||

| Type A | 54 (18·7) | ||

| Type B | 13 (4·5) | ||

| Type C | 15 (5·2) | ||

| Type D | 4 (1·4) | ||

| Combination | 3 (1·0) | ||

| Exercise | 68 (23·5) | ||

| Screening | 18 (6·2) | ||

| Orthogeriatric service | 11 (3·8) | ||

| Other | 17 (5·9) | ||

| Target Population n(%) |

Patient (n=290) | Prior fragility fracture (any) | 77 (26·6) |

| Post-menopausal women | 44 (15·2) | ||

| Prior hip fracture | 38 (13·1) | ||

| Older adults | 30 (10·4) | ||

| Postmenopausal women with low BMD | 27 (9·3) | ||

| Known low BMD | 18 (6·2) | ||

| Females with cancer | 9 (3·1) | ||

| Prior radius fracture | 7 (2·4) | ||

| Males with prostate cancer | 6 (2·1) | ||

| Other | 33 (11·4) | ||

| Clinician (n=42) | Primary care physicians | 23 (54·8) | |

| Specialist physicians | 4 (9·5) | ||

| orthopaedic surgeons | 4 (9·5) | ||

| Junior doctors | 4 (9·5) | ||

| Other | 7 (16·7) | ||

| Outcomes n(%)* | Patient level | Fractures | 65 (22·5) |

| BMD | 73 (25·3) | ||

| DXA | 87 (30·1) | ||

| Treatment (antiresorptive / anabolic) | 113 (39·1) | ||

| Vitamin D | 38 (13·1) | ||

| Calcium intake (supplement+/- diet) | 56 (19·4) | ||

| Osteoporosis knowledge | 32 (11·1) | ||

| Osteoporosis self-efficacy | 14 (4·8) | ||

| Osteoporosis health beliefs | 9 (3·1) | ||

| Clinician level | Ordering DXA | 21 (7·3) | |

| Prescribing (antiresorptive / anabolic) | 48 (16·6) | ||

| Prescribing Vitamin D | 7 (2·4) | ||

| Osteoporosis knowledge | 1 (0·3) |

Footnote: BMD: bone mineral density; DXA: dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; *n>289 and percentages add to >100% as studies may have more than one outcome.

Table 2.

Summary implementation characteristics of included studies.

| Category | Sub-category | n(%) of studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPOC Delivery arrangement n(%)* | How and when care delivered | Group vs individual care | 10 (3·4) |

| Where care is provided | Outreach services | 11 (3·9) | |

| Site of service delivery | 23 (7·9) | ||

| Who provides care | Role expansion or task shifting | 21 (7·6) | |

| Self-management | 48 (16·6) | ||

| Coordination of care | Care pathways | 17 (5·9) | |

| Case management | 2 (0·7) | ||

| Communication between providers | 20 (6·2) | ||

| Disease management | 27 (9·3) | ||

| Integration | 1 (0·3) | ||

| Packages of care | 110 (37·9) | ||

| Teams | 4 (1·4) | ||

| Information and communication technology | Health information systems | 5 (1·7) | |

| The use of information and communication technology | 10 (3·4) | ||

| Telemedicine | 1 (0·3) | ||

| EPOC implementation strategy n(%)* | Targeted at healthcare workers | Audit and feedback | 8 (2·8) |

| Educational materials | 15 (5·2) | ||

| Educational meetings | 8 (2·8) | ||

| Educational outreach visits, or academic detailing | 5 (1·7) | ||

| Clinical Practice Guidelines | 5 (1·7) | ||

| Inter-professional education | 4 (1·4) | ||

| Local consensus processes | 14 (4·8) | ||

| Local opinion leaders | 1 (0·3) | ||

| Patient-mediated interventions | 46 (15·9) | ||

| Reminders | 23 (8·0) | ||

| Tailored interventions | 1 (0·3) | ||

| Targeted at specific types of practice, conditions or settings | Health conditions | 198 (68·5) | |

| Delivery characteristics n(%) | Contact method (n=285) | Face to face | 212 (74·4) |

| Written | 37 (13) | ||

| Telephone | 16 (5·6) | ||

| Electronic | 15 (5·3) | ||

| Other | 5 (1·8) | ||

| Frequency of contact (n=227) | Once | 78 (34·4) | |

| More than once but less than 3 monthly | 42 (18·5) | ||

| 2-3 monthly | 11 (4·8) | ||

| < weekly to monthly | 8 (3·5) | ||

| Weekly | 82 (36·1) | ||

| daily | 6 (2·6) | ||

| Contact location (n=264) | Medical practice / hospital | 163 (61·7) | |

| University / research facility | 12 (4·5) | ||

| Community facility | 30 (11·4) | ||

| Home | 59 (22·3) | ||

| Group vs individual care (n=260) | Individual | 195 (75) | |

| Group | 29 (11·2) | ||

| Both | 36 (13·8) | ||

| Implementation summary statistics | Reach (n=12), mean (SD) | 62,8% (23) | |

| Fidelity (n=77), mean (SD) | 75% (19.2) | ||

| Drop-out (n=155), median (IQR) | 15.4% (8.2, 27) |

Footnote: EPOC: Effective practice and organisation of care; *n>289 and percentages add to >100% as studies may have more than one classification.

3.2. MoC classification

The majority of studies used the EPOC delivery arrangement ‘coordination of care and management of care processes’ (n=177, 61·2%, Table 2), 15 studies compared different delivery arrangements and four studies included more than one subcategory. The most common EPOC implementation strategy was ‘interventions targeted at specific types of practice, conditions or settings’, observed in 198 studies (68·5%), all of which targeted specific conditions, eight studies compared different implementation strategies, and 25 included more than one subcategory. Classifying MoC by activity, the most common MoC was FLS (n=89, 30·8%), of which the majority (n=54) were classified as a Type A (Table 1). The second most common activity was education (n=86, 29·8%), of these 52 targeted patients with eight also sending written communication to a clinician, 24 targeted clinicians only, and 27 targeted both patients and clinicians. In addition, 17 studies included an educational component within another MoC. 32 studies were multi-component (included more than one type of MoC), most commonly screening with education (n=8, 2·8%).

3.3. Study characteristics (Tables 1 and S1)

Most studies were from North America (n=123, 42·6%) or Europe (n=77, 26·6%) (Table S1). Study designs varied with randomised trials predominating (Table 1), however 30 of these did not report the randomisation method used. All studies targeted a patient population. The median (IQR) number of participants was 210 (87, 667), ranging from 13 to 650,000. While 42 studies targeted clinicians, only 14 (33·3%) of studies reported the number of clinicians involved. The median (IQR) number of clinicians was 57 (24, 327), ranging from 5 to 31,459. The median (IQR) follow-up duration for outcome assessment was 12 (6, 12·5) months, and 130 (45%) of studies had follow-up of ≤6 months.

3.4. Implementation characteristics (Table 2)

The majority of studies delivered the MoC in a face-to-face format (n=212, 74·4%), in a medical setting (n=163, 61·7%), with 130 (44·8%) of studies using >one method of delivering care and 34 (11·7%) using >one setting for delivery. Program reach was reported by 120 (41·4%) studies, fidelity by 77 (26·6%) studies, and loss to follow-up was reported by 155 (53.6%) studies (Table 2). Frequency of care contact varied between models and within the same model (Table S1). Of primary exercise studies, 62 studies included at least weekly (48 ≥3 times weekly) contacts, and five were daily. Exercise duration was reported for 64 studies, with a mean (SD) of 53·9 (24·1) min. Education study contact frequency varied with 34 once only, 13 more than once but less than three-monthly, six less than weekly up to monthly, 18 weekly and one daily. The duration of each education session was reported for 30 studies, with a median (IQR) of 52·5 (26·3, 60) min.

3.5. Study outcomes (Table S1)

Overall, 156 (52·2%) of studies reported a significant improvement in one or more of their outcomes (Table S1). The most common outcomes reported were specific osteoporosis treatment rates (antiresorptive / anabolic agents, n=113, 39·1%), followed by DXA rates (n=87, 30·1%). Provider outcomes, including prescribing and investigation ordering, were assessed in only 58 (20·1%) studies, of which 18/48 (37·5%) studies reported a significant increase in prescribing rates. Of the MoC reporting treatment rates, the majority used the EPOC delivery arrangement ‘coordination of care’ (n=80, 70·8%), followed by ‘who provides care’ (n=30, 26·5 %), with the most common subcategory being ‘packages of care’ (n=47, 41·6%) (Table S1). The most common implementation strategy was ‘targeted at healthcare workers’ (n=59, 52·2%), followed by ‘targeted at a disease’ (n=57, 50·4%). Only 38 (33·6%) studies found a significant increase in rates of treatment, including 30 studies classified as ‘coordination of care’, and using the implementation strategy of ‘targeting a disease’ in 20 and ‘targeting healthcare workers’ in 19. Of the MoC reporting DXA rates, most were classified as ‘coordination of care’ (n=63, 72·4%), followed by ‘who provides care’ (n=25, 28·7%), with the most common subcategory of ‘packages of care’ (n=40, 46%). The most common implementation strategy was ‘targeted at a specific disease’ (n=49, 56·3%), followed by ‘targeted at healthcare workers’ (n=41, 47·1%). Most studies [45 (51·7%)] found a significant increase in DXA completion rates, including 30 studies classified as ‘coordination of care’, and using the implementation strategy of ‘targeting healthcare workers’ in 25 and ‘targeting a disease’ in 21 (Table S1).

3.6. Fracture outcomes (Tables 3, S2, S4)

Fracture outcomes were reported for 66 (22·8%) MoC, for 31 (47·7%) of these fracture was the primary outcome (Tables 3 and S2). Risk of bias assessment was performed for 43 studies (controlled trials, cohort studies and controlled before and after studies), with only 17 (38·6%) graded as high quality.

Table 3.

Summary of studies reporting significant reduction in fractures.

| Author (year) | Study design | Type of MoC | Population and sample size (n) | Follow-up months | Delivery of MoC |

EPOC taxonomy |

Clinical outcomes |

Program reach and loss to follow-up | Risk of Bias | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of contact | Contact method | Contact location | Group vs individual care | Delivery arrangement | Implementation strategy | Primary outcome? | Fracture outcomes | |||||||

| FLS | ||||||||||||||

| Amphansap (2016)[37] Thailand |

Cohort study | FLS type A | >50 yr inpatient with MTF 75 |

12 | More than once, but less than 3monthly | Face to face | Hospital Home |

Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture |

0 (0%) MTF vs 36 (30%) in prior cohort, p<0·001 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: intervention 15·7%; control not reported |

+ |

| Bachour (2017)[38] Lebanon |

Cohort study | FLS type A | >50 yr ED patient with MTF 250 |

24 | Not reported | Face to face | Hospital | Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture | 8 (8·2%) total fractures vs 18 (18%) in prior cohort, p=0·004 | Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 81·7%; Control 23·1% |

+ |

| Davidson (2017)[39] Australia |

Cohort study | FLS type C | >45 yr inpatient with MTF 140 |

36 | Once | Not reported | Not reported | Individual | Communication between providers | Educational materials; Patient-mediated interventions | Investigation and treatment |

34 (10·5%) MTF vs 25 (19·1) in prior cohort, p<0·05 13 (8·3%) hip fractures vs 16 (23·2%) in prior cohort, p<0·01 |

Not reported | + |

| Huntjens (2011)[40] Netherlands |

Cohort study | FLS type A | ≥50 yr outpatient or ED patient with non-VF 3255 |

26 | More than once, but less than 3monthly | Face to face | Hospital | Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture | 89 (6·7%) total fractures vs 191 (9·9%) in prior cohort, p=0·001 | Reach: 68·4% Loss to follow-up: not reported |

+ |

| Inderjeeth (2018)[41] Australia |

Cohort study | FLS type A | ≥50 yr ED patient with MTF 339 |

12 | Not reported | Face to face | Hospital Home |

Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture | MTF 17 (8·1%) vs 17 (18·3%) in prior cohort and 8 (17·3%) in usual care, p<0·05 vs prior cohort only | Reach: 64·1% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 16·2%; Usual care 18·2%; Prior cohort 12·4% |

++ |

| Lih (2011)[42] | Cohort study | FLS type A | ≥45 yr outpatient with non-VF 403 |

48 | More than once, but less than 3monthly | Face to face | Hospital | Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture |

10 (4·1%) MTF vs 31 (19·7%) in usual care, p<0·01 1 (0·4%) hip fracture vs 8 (5·1%) in usual care |

Reach: 41·5% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 14·6%; Usual care 36·2% |

0 |

| Nakayama (2016)[43] Australia |

Cohort study | FLS type A | ≥50 yr ED patient with MTF 931 |

36 | Not reported | Face to face | Hospital | Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture | 63 (12·2%) total fractures vs 70 (16·8%) in usual care, p=0·025 | Reach: 20% Loss to follow-up: not reported |

+ |

| Van der Kallen (2014)[44] Australia |

Cohort study | FLS type A | ≥50 yr ED patient with MTF 434 |

12 | More than once, but less than 3monthly | Face to face Telephone |

Hospital Home |

Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture |

11 (6·5%) total fractures vs 36 (18·6%) in usual care, p<0·001 3 (1·4%) VF vs 4 (1·8%) in usual care |

Reach 14% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 27·2%; Usual care 45·5% |

+ |

| Wasfie (2019)[45] United States |

Cohort study | FLS type A | ≥50yr outpatient with VF treated surgically 365 |

26 | 2-3 monthly | Face to face | Hospital | Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture |

78 (37%) total fractures vs 84 (56%) in prior cohort, p=0·01 46 (22%) VF vs 47 (31%) in prior cohort, p=0·29 |

Not reported | 0 |

| Education | ||||||||||||||

| Becker (2011)[46], Heinrich (2013)[47] Germany |

Controlled before after | Education – patient & clinician Exercise |

≥65yr in nursing home Clinicians: not reported Patients: 45321 |

12 | Education: not reported Exercise: 60min 2x per wk for 52wk |

Face to face Written Video |

Home | Group | Disease management | Local opinion leaders | Fracture | 331 (2·4%) hip fractures vs 917 (2·9%) in usual care, p<0·05 | Not reported | + |

| Pekkarinen (2013)[48] Finland |

Non-randomised study | Education – patient | 60–70 yr post-menopausal women 2178 |

120 | 150min 5x per wk for 1 wk | Face to face Written |

Medical Centre | Both | Self-management | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture |

59 (5·9%) MTF vs 95 (8·1%) in usual care, p=0·045 12 (1·2%) hip fractures vs 29 (2·5%) in usual care, p=0·039 |

Reach: 39·4% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 28·7%; Control 37·6% |

- |

| Sorbi (2016)[49] Iran |

Cohort study | Education - clinician | Orthopedic surgeons ≥60 yr inpatient with MTF Clinicians: 30 Patients: 515 |

24 | 15min 2x per wk for 13 wk | Face to face | Hospital | Group | Disease management | Educational materials | Treatment | 0·8 total fractures per person per year vs 1·6 in previous cohort, p<0·05 | Not reported | 0 |

| Screening | ||||||||||||||

| Harness (2012)[50] United States |

Cohort study | Screening – DXA | ≥65 yr female, ≥70 yr male, or ≥50 yr at risk of OP 524612 |

72 | Not reported | Face to face Written |

GP practice | Individual |

Disease management | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture | 2595 (1·5%) DR fractures vs 6063 (1·7%) in usual care, p<0·05 | Not reported | + |

| Parsons (2019)[51], Shepstone (2018)[12] United Kingdom |

RCT | Screening – DXA, FRAX | 70–85 yr women 12483 |

60 | Once | Written | GP practice | Individual | Disease management | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture | 951 (15·3%) total fractures vs 1002 (16%) in usual care, p=0·183 805 (12·9%) MTF vs 852 (13·6%) in usual care, p=0·178 164 (2·6%) hip fractures vs 218 (3·5%) in usual care, p =0·002 |

Reach: 95·6% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 14·4%; Control 14·8% |

++ |

| Zhumk-hawala (2013)[52] United States |

Cohort | Screening – DXA | ≥50 yr males w prostate cancer on leuprolide 1482 |

36 | Once | Face to face Written |

GP practice | Individual | Disease management | Patient-mediated interventions Reminders |

Fracture | 18 (1·68%) hip fractures vs 17 (4·14%) in usual care, p<0·001 | Not reported | + |

| Exercise | ||||||||||||||

| Kemmler (2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2016,2017)[53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58] Germany |

Controlled before and after study | Exercise | Post-menopausal women with osteopenia 137 |

192 | 40min 4x per wk for 800 wk | Face to face Written |

Home Other not reported |

Both | Self-management | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture |

17 (28·8%) total fractures vs 28 (60·9%) in usual care, p=0·03 13 (22%) MTF vs 24 (52·2%) in usual care, p=0·046 |

Reach: 53·3% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 31·4%; Control 10·9% |

++ |

| Korpe-lainen (2010)[59] Finland |

RCT | Exercise | 70–73 yr women with low BMD 160 |

85 (fractures) 72 (BMD) |

25min daily | Face to face |

Home Other not specified |

Both | Group vs individual care | Targeted at specific health conditions | BMD | 17 (20·2%) total fractures vs 23 (30·3%) in usual care, p=0·22 0 hip fractures vs 5 (6·6%) in usual care, p=0·02 1 (1·2%) VF vs 1 (1·3%) in usual care |

Reach: 25·5% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 34·5%; Control 40·8% |

++ |

| OGS | ||||||||||||||

| Cheung (2018)[60] Hong Kong |

Cohort | OGS Specialist review Education – patient Exercise Patient support |

≥65 yr w hip fracture 153 |

18 | Exercise: 60min weekly Vibration: 20min 3x per wk Education 3-monthly |

Face to face |

Community Hospital |

Both | Disease management | Targeted at specific health conditions | Fracture | 1 (1·3%) total fractures vs 8 (10·4%) in usual care, p=0·034 | Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 28·3%; Control 25·2% |

+ |

| Specialist review | ||||||||||||||

| Gomez (2019)[61] Australia |

Pre-test post-test study | Specialist review | ≥65 yr referred to falls and fracture clinic 106 |

6 | Once | Face to face | Hospital | Individual | Disease management | Targeted at specific health condition | Fractures | 8·6% total fractures, p<0·001 vs baseline | Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: 10·9% |

n/a |

Footnote: p values are between groups unless otherwise specified. Risk of bias: ++ (high quality), + (acceptable), - (low quality), 0 (unacceptable). MoC: model of care; EPOC: effective practice and organisation of care; FLS: fracture liaison service; yr: year; MTF: minimal trauma fracture; ED: emergency department; VF: vertebral fracture; min: minutes; wk: week; DXA: dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; OP: osteoporosis; GP: general practitioner; DR: distal radius; RCT: randomised controlled trial; BMD: bone mineral density; OGS: orthogeriatric service.

47 (72·3%) studies had a comparator group for fracture outcomes, of these, 19 (40·4%) found a significant reduction in fractures (Tables 3 and S4). The majority of studies that found a significant fracture reduction had this as a primary outcome (n=16, 84·2%), however only four (21·1%) studies were graded as high quality. Studies that found a significant fracture reduction had median (IQR) follow-up duration of 24 (15, 36·9) months, median (IQR) patient number of 403 (157, 1830), median (IQR) reach of 41·5% (25·5, 61·4) and median (IQR) loss to follow-up of 27·8% (15·8, 30·7). Of the 28 studies which did not find a significant reduction in fractures, 13 (46·4%) were graded as high quality. These studies had a shorter median (IQR) follow-up duration of 12 (12, 25·8) months, median (IQR) patient number of 724 (305, 4326), median (IQR) reach of 67·7% (40·4, 78·3) and median (IQR) loss to follow-up of 14·4% (5·4, 25).

3.7. BMD outcomes

73 (25·3%) MoC reported BMD outcomes, for 66 (90·4 %) of these BMD was the primary outcome (Tables 4 and S3). The majority of these were exercise MoC (n=65, 89·0%). 41 (56·2%) studies found a significant improvement in BMD with the MoC. This significant improvement in BMD was seen at the lumbar spine in 27 studies, femoral neck in 18 studies and total hip in 17 studies. 21 studies found an improvement in BMD at >one region of interest.

Table 4.

Summary of studies reporting significant improvement in BMD.

| Author (year) | Study design | Type of MoC | Population and sample size (n) | Follow-up months | Delivery of MoC |

EPOC taxonomy |

Clinical outcomes |

Program reach and loss to follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of contact | Contact method | Contact location | Group vs individual care | Delivery arrangement | Implementation strategy | Primary outcome? | BMD change | ||||||

| FLS | |||||||||||||

| Chandran (2013)[62] Singapore |

Case study | FLS type A | ≥50 yr inpatient, outpatient or ED patient with MTF 287 |

24 | More than once, but less than 3monthly | Face to face Telephone |

Hospital Home |

Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Treatment |

LS: +4·4%, p<0·01 vs baseline TH +2·7%, p<0·01 vs baseline |

Not reported |

| Eekman (2014)[63] Netherlands |

Case study | FLS type A | ≥50 yr ED patient with MTF 1116 |

12 | 2-3 monthly | Face to face Telephone |

Hospital Home |

Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | Reasons for not attending FLS and adherence |

LS: +3·9%, p<0·001 vs baseline TH: +2·3%, p<0·001 vs baseline |

Reach: 50·6% Loss to follow-up: 74·9% |

| Education | |||||||||||||

| Hien (2009)[64] Vietnam |

Non-randomised trial | Education – patient | Postmenopausal women with low calcium intake 140 |

18 | Daily | Face to face Written Video |

Home Community |

Both | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | Calcium intake |

Calcaneal*: 0%; control -0·5%, p<0·05 *calcaneal US |

Reach not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 18·6%; Control 31·7% |

| Wang (2016)[65] China |

RCT | Education – patient Exercise Patient support |

Known OP 436 |

48 |

Monthly | Face to face Written |

Community | Both | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | Multiple outcomes including BMD |

Females: LS: +10·4% vs control +2·19%, p<0·01 FN: +14·1% vs control +2·7%, p<0·01 Males: LS: +10·5% vs control +1·06%, p<0·01 FN: +11·1% vs control +1·14%, p<0·01 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 6·4%; Control 13·8% |

| Exercise | |||||||||||||

| Aboarrage (2018)[66] Brazil |

RCT | Exercise | Postmenopausal women 25 |

6 | 30 min 3x per wk for 24 wk | Not reported | Community | Not reported | Site of service delivery | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS +3·7% vs control +0·88%, p<0·01 TF +6·5% vs control -1·38%, p<0·01 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: 0% |

| Alayat (2018)[67] Saudi Arabia |

RCT | Exercise Laser Group 1 laser Group 2 exercise Group 3 laser & exercise |

Men with low BMD 100 |

12 | 20 min exercise ± 18min laser 3x per wk for 24 wk | Face to face | Not reported | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: Group 1 -1%, Group 2 +10·1%, Group 3 +13% vs control -1·5%, p<0·001 Group 3 vs control TH: Group 1 0%; Group 2 +3·3%; Group 3 +2·2% vs control-1·1%, p<0·001 Group 3 vs control or Group 1 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Group 1 16%; Group 2 12%; Group 3 12%; Control 20% |

| Almstedt (2016)[68] United States |

Pre-test post-test | Exercise | Female cancer survivors 26 |

7 | 60 min 3x per wk for 26 wk | Face to face | University | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS +2·5% vs baseline, p=0·012 TH +1·7% vs baseline, p=0·048 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: 23·1% |

| Angin (2015)[69] Turkey |

RCT | Exercise | Post-menopausal women with low BMD 44 |

6 | 60 min 3x per wk for 24 wk | Face to face | Not reported | Group | Group vs individual care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | LS +6·5% vs control-3·3%, p<0·001 | Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: not reported |

| Astorino (2013)[70] United States |

Pre-test post-test | Exercise | Spinal cord injury 13 |

6 | 150 min 2x per wk for 26 wk | Face to face | Rehab centre | Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: +4·7% vs baseline, p<0·05 TH: -7% vs baseline, p<0·05 FN -4% vs baseline, p<0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: 23·1% |

| Basat (2013)[71] Turkey |

RCT | Exercise Group 1 strength exercise Group 2 high-impact exercise |

Postmenopausal women with low BMD 42 |

6 | 60 min 3x per wk for 26 wk | Face to face | Hospital | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: Group 1 +1·3%; Group 2 +0·5% vs control-2·5%, p=·006 Group 2 vs control FN: Group 1 +1·6%; Group 2 1·2% vs control -1%, p=0·006 Group 2 vs control |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Group 1 21·4%; Group 2 14·3%; Control 14·3% |

| Beavers (2014)[72] United States |

RCT | Exercise Education – patient Group 1: Diet plan Group 2: Exercise Group 3: Diet plan & exercise |

≥55 yr, BMI 27-40 and osteoarthritis of knees 392 |

18 | Exercise: 60 min 3x per wk Education: 1-2 weekly |

Face to face | Community Home |

Both | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | LS: Group 1 +0·3%; Group 2 +0·5% vs Group 3 -0·1%; p=0·47 TH: Group 1 -2·5%; Group 2 -0·2% vs Group 3 -2%, p<0·01 Group 1 vs Group 3 FN: Group 1 -1·9%; Group 2 -0·3% vs Group 3 -1·8%, p<0·01 Group 1 vs Group 3 |

Reach: 86·3% Loss to follow-up: Group 1 31%; Group 2 26·4%; Group 3 25% |

| Bergstrom (2012)[73] Sweden |

RCT | Exercise | Postmenopausal women with low BMD and DR fracture 112 |

12 | 40 min 3-4x wk for 52 wk | Face to face | Community | Not reported | Site of service delivery | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | TH: +0·7% vs control -0·9%, p=0·04 | Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 20%; Control 15·4% |

| Bocalini (2009)[74] Brazil |

RCT | Exercise | Postmenopausal women 35 |

6 | 60 min weekly for 24 wk | Face to face | Community | Not reported | Site of service delivery | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: -0·1% vs control -1%, p<0·05 FN: -0·14% vs control -1·6%, p<0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 13%; Control, 16·7% |

| Bolton (2012)[75] Australia |

RCT | Exercise | Postmenopausal women with low BMD 39 |

12 | 60 min 3x per wk for 52 wk | Face to face | Community | Not reported | Site of service delivery | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | LS: -0·3% vs control -0·9% p>0·05 TH: +0·5% vs control -0·9%, p=0·02 |

Reach :34·5% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 0%; Control 10% |

| Borba-Pinheiro (2016)[76] Brazil |

RCT | Exercise Group 1: 3x per wk Group 2: 2x per wk |

Postmenopausal women with low BMD 60 |

13 | 60 min for 56wk | Face to face | Not reported | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | Absolute change not reported. p<0·05 Group 1 vs control for TH, FN p<0·05 Group 1 vs Group 2 for LS, TH and FN |

Reach: 96·8% Loss to follow-up: Group 1 0%; Group 2 20%; Control 20% |

| Chuin (2009)[77] Canada |

RCT | Exercise Antioxidants Group 1: antioxidants Group 2: exercise Group 3: Antioxidants & exercise |

Postmenopausal women 34 |

6 | Exercise: 60 min 3x per wk for 26 wk | Face to face | Not reported | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: Group 1 0·1%; group 2 -0·1%; Group 3 -0·3% vs control -1·5%, p<0·05 all groups vs control FN: Group 1 +0·9%; Group 2 -0·3%; Group 3-1·4% vs control +0·2%, p>0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: not reported |

| Daly (2019)[78], Gianoudis (2014)[79] Australia |

RCT | Exercise Education – patient & clinician Patient support |

≥60 yr Clinicians: not reported Patients: 162 |

18 | 60 min 3x per wk for 78 wk | Face to face Telephone Written |

Community | Both | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health conditions | BMD | LS: +1·49% vs control +0·76%, p=0·125 TH: +0·61% vs control +0·32%, p>0·05 FN: +0·6% vs control -1·33%, p<0·001 |

Reach: not specified Loss to follow-up: Intervention 4·9%; Control 12·3% |

| deMatos (2009)[80] Portugal |

Non-randomised trial | Exercise | Postmenopausal women with low BMD 59 |

12 | 45 min, frequency not reported, for 52 wk | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS +1·17% vs control -2·26% p<0·013 TH: -0·71%; control -0·6%, p>0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: not reported |

| El-Kader (2016)[81] Saudi Arabia |

RCT | Exercise | COPD on inhaled glucocorticoids 60 |

6 | 30 min 3x per wk for 26 wk | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: +20·8% vs control -1·1%, p<0·04 DR: +25·8% vs control -1·71%, p<0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: not reported |

| Elsisi (2015)[82] Egypt |

RCT | Exercise Group 1: exercise Group 2: electromagnetic field |

Postmenopausal women, sedentary 30 |

3 | 30 min (electromagnetic field) or 60min (exercise) 3x per wk for 12 wk | Face to face | Hospital | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: exercise 2·18% vs electromagnetic field +29%, p<0·01 FN: exercise +2·7% vs electromagnetic field +16·9%, p=0·002 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: 0% |

| Garcia-Gomariz (2018)[83] Spain |

RCT | Exercise | Postmenopausal women 36 |

24 | 60 min 2x per wk for 92 wk | Face to face | Hospital | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | LS: +24·3% vs control +14·7%, p=0·4 FN: +36·8%; vs control -4·7% p<0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 5·6%; Control 5·6% |

| Hojan (2013, 2013)[84],[85] |

Pre-test post-test | Exercise Phase 1 (control): no exercise Phase 2: aerobic exercise Phase 3: resistance exercise |

Pre-menopausal women with breast cancer receiving endocrine therapy 41 |

18 | 45 min daily for 26 wk for each phase | Written Face to face |

Home | Individual | Self-management | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | 6 month change,: LS: Phase 2 -3·6%; Phase 3 +1·9% vs control -8·9%, p<0·05 phase 2 vs control, p<0·01 control vs baseline TH: Phase 2 -1%; Phase 3 +1·1% vs control -6·8%, p<0·01 control vs baseline FN: Phase 2 -1·1%; Phase 3 -6·8%, p not reported Change from baseline: LS: -10·6% TH: -6·8% |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: 22·6% |

| Kemmler (2013)[86] Germany |

RCT | Exercise | Postmenopausal women 85 |

12 | 60 min 3sx per wk for 52 wk | Face to face | Not reported | Group | Group vs individual care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: -0·1% vs control -2%, p=0·002 TH: -0·4% vs control -0·8%, p=0·152 |

Reach: 81% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 16·3%; Control 28·6% |

| Kemmler (2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2016,2017)[53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58] Germany |

Controlled before and after study | Exercise | Post-menopausal women with osteopenia 137 |

192 | 40 min 4x per wk for 800 wk | Face to face Written |

Home Other not reported |

Both | Self-management | Targeted at specific health conditions | BMD |

LS: -1·5% vs control -5·8%, p<0·001 TH: -5·7% vs control -9·7% p<0·01 FN: -6·5% vs control -9·6%, p=0·001 |

Reach: 53·3% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 31·4%; Control 10·9% |

| Kukuljan (2009, 2011)[87],[88] Australia |

RCT | Exercise Fortified milk Group 1: Exercise Group 2: Fortified milk Group 3: Exercise & fortified milk |

Older males 180 |

18 | 60 min 3x per wk for78 wk | Face to face | Community | Group | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

Absolute change not reported LS: p<0·01, all groups increased vs control FN: effect of exercise 1·9%, p<0·001 |

Reach: 98·9% Loss to follow-up: Group 1 2·2%; Group 2 2·2%; Group 3 2·2%; Control 4·5% |

| LeBlanc, (2013)[89], Sibonga (2019)[90] United States |

Controlled before and after study | Exercise Alendronate Group 1: exercise Group 2: exercise & alendronate |

Astronauts 35 |

12 | 150 min 6x per wk for 24 wk | Face to face | Home | Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | Absolute change not reported p<0·05 Group 2 vs Group 1 at LS and TH |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Group 1 0%; Group 2 42·9% |

| Liu (2015)[91] China |

RCT | Exercise Group 1: Tai Chi Group 2: Calcium & Vitamin D Group 3: Tai Chi, Calcium & Vitamin D |

Postmenopausal women with low BMD 198 |

12 | 3 min daily for 52 wk | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | Absolute change not reported LS: p<0·05 all groups improved vs control FN: Group 1 1·9% higher BMD than control, p<0·001; Group 3 2·3% higher BMD than control, p<0·001 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Group 1 4%; Group 2 10%; Group 3 2%; Control 12·5% |

| Marchese (2012)[92] Italy |

RCT | Exercise | Women with low BMD 22 |

6 | 60 min 3x per wk for 24 wk | Face to face | Not reported | Group | Group vs individual care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: +14·9% vs control -6·6%, p<0·001 TH: +5·06% vs control -8·6%, p=0·026 FN: +10·39% vs control -4·63%, p=0·002 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: not reported |

| Marques (2011)[93] Portugal |

RCT | Exercise Group 1: resistance exercise Group 2: aerobic exercise |

Postmenopausal women 71 |

8 | 60 min 3x per wk for 32 wk | Face to face | University campus | Group | Group vs individual care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

TH: Group 1 +1·6%; Group 2 +0·12% vs control -0·84%, p=0·034 Group 1 vs other groups FN: Group 1 -1·6%; Group 2 +0·46% vs control -0·29%, p>0·05 |

Reach: 86·6% Loss to follow-up: Group 1 34·8%; Group 2 20·8%; Control 16·7% |

| Morse (2019)[94] United States |

RCT | Exercise Zoledronic acid Group 1: exercise & zoledronic acid Group 2: exercise |

Non-ambulatory spinal cord injury 20 |

12 | 30 min 3x per wk for 52 wk | Face to face | Not reported | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | HRQCT |

Tibia CTI Group 1 +0·04% vs Group 2 -6·96%, p=0·013 Tibia CBV: Group 1 +0·06% vs Group 2 -5·73%, p<0·05 Distal femur CTI: Group 1 +0·25% vs Group 2 -1·02%, p<0·05 Distal femur CBV: Group 1 +1·67% vs Group 2 +1·44%, p<0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Group 1 70·6%; Group 2 71·4% |

| Murai (2019)[95] Brazil |

RCT | Exercise | Bariatric surgery 70 |

6 | 75 min 3x per wk for 26 wk | Face to face | Hospital | Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | LS: -0·52% vs control -1·43%, p>0·05 TH: -5% vs control -7·26%, p=0·009 FN -4·41% vs control -7·33%, p=0·007 |

Reach: 53·8% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 21·9%; Control 22·6% |

| Murtezani (2014)[96] Kosova |

RCT | Exercise Group 1: land exercise Group 2: aquatic exercise |

Postmenopausal women with low BMD 64 |

10 | 35–55min 3x per wk for 43 wk | Face to face | Not reported | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | LS: Group 1 +5·53% vs Group 2 +3·92%, p<0·001 | Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Group 1 6·1%; Group 2 3·2% |

| Nicholson (2015)[97] Australia |

RCT | Exercise | Postmenopausal women 57 |

6 | 50 min 2x per wk for 26 wk | Face to face | Community | Group | Site of service delivery | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: +1·01% vs control -2·09%, p=0·005 group x time TH: -0·21% vs control -2·99%, p>0·05 FN: +0·11% vs control -1·5% p>0·05 |

Reach: 96·6% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 14·3%; Control 10·3% |

| Saarto (2012)[98] Finland |

RCT | Exercise | Women with breast cancer 573 |

12 | 60 min 3x per wk for 52 wk | Face to face | Home | Both | Site of service delivery | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | Premenopausal subgroup: LS: -1·9%; control -2·2%, p>0·05 FN: -0·2%; control -1·4%, p=0·01 Postmenopausal subgroup: LS: -1·6%; control -2·1%, p>0·05 FN: -1·1%; control -1·1%, p=0·99 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 7·3%; Control 6·3% |

| Sen (2020)[99] Turkey |

RCT | Exercise Vibration Group 1: High impact exercise Group 2: Exercise & vibration |

40–65 yr postmenopausal women with low BMD 49 |

6 | 60 min 3x per wk for 24 wk | Face to face | Research facility | Not reported | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: Group 1 -0·7%; Group 2 +1·3% vs control -1·9%, p=0·005 Group 2 vs control FN: Group 1 +1·9%; Group 2 +5% vs control -2·9%, p=0·003 Group 2 vs control TH: Group 1 -0·6%; Group 2 +1·9% vs control -1·3%, p=0·031 Group 2 vs control |

Reach: Not reported Loss to follow-up: Group 1 15·8%; Group 2 21·1%; Control 10% |

| Silverman (2009)[100] United States |

Non-randomised trial | Exercise | Postmenopausal women with BMI 25–40, sedentary 86 |

6 | 52 min 3x per wk for 26 wk | Face to face | Community Home |

Individual | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD | LS: +0·42% vs control +0·18%, p>0·05 FN: +1·86% vs control -0·87%, p<0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: not reported |

| Villareal (2017)[101] United States |

RCT | Exercise Specialist review Group 1: diet & aerobic exercise Group 2: diet & resistance exercise Group 3: diet & combined exercise |

≥65 yr, BMI >29, sedentary 160 |

6 | Exercise: 60 min 4x per wk for 26 wk Dietician review: weekly |

Face to face | University campus | Both | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | Physical performance test. Secondary: BMD |

LS: Group 1 +0·18%; Group 2 +0·7%; Group 3 +0·69% vs control +0·88%, p>0·05 TH: Group 1 -2·6%; group 2 -0·57%; Group 3 -1·1% vs control +0·04%, p<0·05 Group 1 vs all other groups |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Group 1 12·5%; Group 2 12·5%; Group 3 12·5%; Control 10% |

| von Stengel (2011)[102] Germany |

RCT | Exercise Vibration Group 1: exercise Group 2: exercise & vibration |

Postmenopausal women 151 |

18 | 40 min 4x per wk for 78 wk | Face to face | University Home |

Both | Packages of care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: Group 1 +2·05%; Group 2 +1·49% vs control +0·42%, p<0·05 Group 1 vs control TH: Group 1 +0·12%; group 2 +0·12% vs control -0·12%, p>0·05 |

Reach: 80·3% Loss to follow-up: Group 1 10%; Group 2 14%; Control 7·8% |

| Watson (2015, 2018)[103],[104] Australia |

RCT | Exercise | Postmenopausal women 101 |

8 | 30 min 2x per wk for 35 wk | Face to face | University campus | Group | Group vs individual care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: +2·9% vs control -1·2%, p<0·001 FN: +0·1% vs control -1·8%, p=0·001 |

Reach: 48·3% Loss to follow-up: Intervention 12·2%; Control 17·3% |

| Winters-Stone (2011)[105] United States |

RCT | Exercise | ≥50yr postmenopausal women with breast cancer 106 |

12 | 60 min 3x per wk for 52 wk | Face to face Written |

University | Both | Group vs individual care | Targeted at specific health condition | BMD |

LS: +0·41% vs control -2·27%, p=0·013 TH: -0·35% vs control -0·83%, p>0·05 FN: -1·37% vs control -2·06%, p>0·05 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: Intervention 30·8%; Control 42·6% |

| Specialist Review | |||||||||||||

| Cheung (2013)[106] Australia |

Pre-test post-test | Specialist review | Men with prostate cancer on ADT 113 |

24 | 2-3 monthly | Face to face | Hospital | Individual | Packages of care | Clinical practice guidelines | BMD | LS: -1·2% vs baseline, p=0·66 TH: -2·1% vs baseline, p<0·001 |

Reach: not reported Loss to follow-up: 26·1% |

Footnote: p values are between groups unless otherwise specified. MoC: model of care; EPOC: effective practice and organisation of care; BMD: bone mineral density; FLS: fracture liaison service; yr: year; ED: emergency department; MTF: minimal trauma fracture; LS: lumbar spine; TH: total hip; US: ultrasound; RCT: randomised controlled trial; OP: osteoporosis; FN: femoral neck; min: minutes; wk: week; TF: total femur; BMI: body mass index; DR: distal radius; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HRQCT: high resolution quantitative computer tomography; CTI: cortical thickness index; CBV: cortical bone volume.

Studies that found a significant improvement in BMD had median (IQR) follow-up duration of 12 (6, 18) months, median (IQR) patient number of 70 (39, 140), median (IQR) reach of 80·7% (52·6, 89·1) and median (IQR) loss to follow-up of 13·7% (6·2, 22·1). The setting for delivering care was mostly in the community (n=10, 24·4%), medical centre (n=8, 19·5%) or research facility (n=7, 17·1%). Studies that did not find a significant improvement in BMD had median (IQR) follow-up duration of 12 (5·9, 12) months, median (IQR) patient number of 84 (41, 146), median (IQR) reach of 55·8% (50·4, 70·3) and median (IQR) loss to follow-up of 13% (9·1, 26·2). The setting for delivering care for these studies was mostly in the community (n=12, 37·5%) or home (n=9, 28·1%).

3.8. Gaps in reporting

Only 20 (6·9%) studies reported on consumer satisfaction, seven (2·4%) reported on clinician satisfaction, and 17 (5·9%) reported on cost. Adverse outcomes were reported by 37 (12.8%) of studies and 29 of these were exercise studies. Of these, 17 studies reported musculoskeletal adverse effects, and 16 reported no adverse effects.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest comprehensive review of both primary and secondary MoC for osteoporosis. The most common MoC for osteoporosis were classified as ‘coordination of care’, with the subcategory of ‘packages of care’, and used the implementation strategy of ‘targeting a specific disease’. The most common activities are FLS and education. Few studies report on implementation characteristics of the model, such as reach, fidelity, and loss to follow-up, which may limit the ability for the MoC to be adapted to other settings and affect the rigour of the results. The majority of models showed an improvement in their primary outcome, although within each outcome, there were mixed results for similar types of models.

It is critical to recognise that implementation characteristics of MoC can influence outcomes [32]. Yet no previous reviews have assessed delivery and implementation characteristics of MoC for osteoporosis, and studies often omit these key details from publications. For example, a FLS may involve face-to-face, telephone or written contact, and may occur on the hospital ward, in a designated clinic or remotely, and each of these approaches may lead to different results. Furthermore, the ability of staff to screen all eligible patients, uptake of FLS by invited patients, fidelity to standardised investigations, and dropout rates, will influence the efficacy of the program. Less than half of included studies reported the reach of the MoC or fidelity to the program, and only half reported loss to follow-up. Where studies have high dropout rates or low reach or fidelity, consumer and clinician feedback may help to explain reasons for this, including the acceptability of the MoC, burden or perceived lack of efficacy, however this was rarely reported by studies. Co-design is now considered standard practice for developing MoC, and consumer and clinician perspectives should be included routinely when reporting MoC [33,34].

We are not the first group to attempt to summarise clinical outcomes of MoC for osteoporosis. Three recent systematic reviews analysed DXA and treatment rates among adults at risk of, or with prior, fragility fracture [15,16,35]. Two included only randomised controlled trials, while one also included quasi-experimental studies with a control group. All used different classification systems for MoC, with one classifying by activities (such as screening, education, feedback) [15], one broadly grouping MoC (FLS, case management, orthopaedic / fracture clinic) [16], and one classifying as structural, healthcare provider- or patient-focussed [35]. Results were mixed. While one study found a significant increase in treatment and DXA rates in a pooled analysis of all types of models [15], another found this benefit for structural and patient-focussed interventions [35], and another only found evidence for benefit in the population who had a prior fracture [16]. In a sub-analysis of studies including only people without prior fracture, the only intervention with benefit was self-scheduling of DXA with education, which increased DXA rates [16]. Several previous reviews have also focussed only on secondary prevention after a fracture [17], [18], [19]. One review included only RCTs, while others included additional study types. Again, different classification systems were used to group MoC, with one study not grouping models at all, one classifying models of care as FLS Types A-D, and the other classifying models based on the presence or absence of dedicated personnel, whether BMD was ordered or treatment initiated within model, and whether the model was “intensive” (both of the former criteria) [17], [18], [19]. These reviews suggested improvement in treatment rates overall, with a trend towards increased efficacy for more intensive MoC, while results for increased DXA rates were mixed. These mixed results between reviews may relate to inclusion criteria, differences in classifying models of care or implementation characteristics not reported in these reviews. We have attempted to use a validated system for classifying models of care, that can be replicated by other studies, and to include detail on implementation characteristics which may explain differences between trial results.

Although treatment rates are an important outcome for MoC for osteoporosis, it is important to understand that not all patients in primary prevention studies require treatment. The proportion who require treatment will depend on the population and risk of re-fracture, and the success of this treatment depends on patient adherence [36]. Fracture outcomes have been included in two previous reviews, one focussed on secondary prevention after fracture, and the other including both primary and secondary prevention [15,17]. One study including only RCTs performed a meta-analysis of 10 studies, which demonstrated no fracture reduction overall, or when analysed separately for models grouped by activity [15]. The other study included all study designs, but due to the small number of studies, lack of control group and lack of power, no statement could be made about the efficacy for fracture reduction [17]. It is important to note that we have reported fracture outcomes in any study reporting this, whether or not it was the primary outcome. We would like to highlight that many studies were not powered for fracture outcomes and did not include follow-up of sufficient duration to find a meaningful difference in fracture rates. Many studies also did not include a comparison group due to the study design. Of those that did compare fracture rates, less than half found a significant reduction in fractures, and few of these studies were graded as high quality. As a reduction in fractures is the most important outcome for any osteoporosis MoC, we hope that studies continue to follow up and report on fractures over time. More recently, BMD has been suggested as a surrogate marker for osteoporosis therapeutic trials. Few MoC other than exercise studies have reported this outcome, but it could be considered by investigators in the future.

There are several limitations to our study. The study is descriptive only and does not include comparative statistics due to the broad inclusion criteria in our search. In describing our primary clinical outcomes of fractures and BMD change, we included studies with these as both primary or secondary outcomes. Given this, studies may have been underpowered for these specific outcomes. Strengths of our study include summarising delivery and implementation characteristics of studies, and using the validated EPOC classification system to categorise MoC, which can be applied to a broad variety of different interventions, and reproduced in future studies. We have also included all types of study designs, reflecting the fact that RCTs are not always appropriate for reporting complex interventions, and making this review a comprehensive summary of MoC worldwide.

This comprehensive scoping review in a vital area of rising morbidity and mortality reveals a wide variety of MoC for people with or at risk of osteoporosis. A minority of studies reports delivery and implementation characteristics, and this may influence the efficacy of these models, and the ability to translate them to real-world practice. Results of the MoC demonstrate mixed efficacy for fracture reduction, increases in BMD, and other outcomes such as treatment and DXA rates, and these disparities may be explained by exploring implementation characteristics. We suggest that future studies should include implementation outcomes in their reports, consider a pragmatic trial or effectiveness implementation hybrid trial study design, and report on fractures, or BMD increases as a surrogate marker for this. Lastly, co-design, and the perspectives of clinicians and consumers, is vital to implementation. It is important that researchers recognise this and ensure that these perspectives are included in future studies.

Funding

None.

Data sharing statement

Data dictionary, data collection table, list of excluded studies provided on request to AJ, at alicia.jones@monash.edu.

Declaration of Competing Interest

AJ is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council postgraduate research scholarship (Grant No. 1169192) and has received a travel grant from the Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society.

MH is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council postgraduate research scholarship (Grant No. 2002671).

PE has received institutional grants or contracts from Amgen, the National Health and Medical Research Council, Alexion and Eli-Lilly; payments to institution from Amgen, is a participant on Celltrion Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board, and has a leadership or fiduciary role on the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research executive, International Osteoporosis Foundation board and Healthy Bones Australia board.

HT is the recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship Grant.

AV reports no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101022.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Wright N.C., Looker A.C., Saag K.G. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts JJ, Abimanyi-Ochom J, Sanders KM, Osteoporosis costing all Australians a new burden of disease analysis-2012 to 2022. Melbourne, Vic: Osteoporosis Australia; 2013.

- 3.Warriner A.H., Patkar N.M., Curtis J.R. Which fractures are most attributable to osteoporosis? J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amin S., Achenbach S.J., Atkinson E.J., Khosla S., Melton L.J., 3rd. Trends in fracture incidence: a population-based study over 20 years. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(3):581–589. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borgström F., Karlsson L., Ortsäter G. Fragility fractures in Europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15(1):59. doi: 10.1007/s11657-020-0706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnell O., Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1726–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odén A., McCloskey E.V., Kanis J.A., Harvey N.C., Johansson H. Burden of high fracture probability worldwide: secular increases 2010–2040. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(9):2243–2248. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cehic M., Lerner R.G., Achten J., Griffin X.L., Costa M.L., Prieto-Alhambra D. Prescribing and adherence to bone protection medications following hip fracture in the United Kingdom: results from the world hip trauma evaluation (WHiTE) cohort study. Bone Jt J. 2019;101-B(11):1402–1407. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B11.BJJ-2019-0387.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen D, Bazell C, Pelizzari P, Pyenson B. Medicare cost of osteoporotic fractures. The clinical and cost burden of an important consequence of osteoporosis. Milliman Research Report For the National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2019. Accessible at: https://assets.milliman.com/ektron/Medicare_cost_of_osteoporotic_fractures.pdf.

- 10.Gillespie C.W., Morin P.E. Trends and disparities in osteoporosis screening among women in the United States, 2008–2014. Am J Med. 2017;130(3):306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones A.R., Tay C.T., Melder A., Vincent A.J., Teede H. What are models of care? a systematic search and narrative review to guide development of care models for premature ovarian insufficiency. Semin Reprod Med. 2021 doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1726131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepstone L., Lenaghan E., Cooper C. Screening in the community to reduce fractures in older women (SCOOP): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):741–747. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32640-5. (London, England) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burch J, Tort S, (on behalf of Cochrane Clinical Answers Editors). What are the effects of professional interventions for general practitioners aimed at improving management of osteoporosis? Cochrane Clinical Answers. 2017.

- 14.Shojaa M., von Stengel S., Kohl M., Schoene D., Kemmler W. Effects of dynamic resistance exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis with special emphasis on exercise parameters. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(8):1427–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05441-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastner M., Perrier L., Munce S.E.P. Complex interventions can increase osteoporosis investigations and treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(1):5–17. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nayak S., Greenspan S.L. How can we improve osteoporosis care? a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of quality improvement strategies for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(9):1585–1594. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganda K., Puech M., Chen J.S. Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(2):393–406. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2090-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sale J.E.M., Beaton D., Posen J., Elliot-Gibson V., Bogoch E. Systematic review on interventions to improve osteoporosis investigation and treatment in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(7):2067–2082. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1544-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Little E.A., Eccles M.P. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to improve post-fracture investigation and management of patients at risk of osteoporosis. Implement Sci. 2010;5:80. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Black D.M., Bauer D.C., Vittinghoff E. Treatment-related changes in bone mineral density as a surrogate biomarker for fracture risk reduction: meta-regression analyses of individual patient data from multiple randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(8):672–682. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfenden L., Foy R., Presseau J. Designing and undertaking randomised implementation trials: guide for researchers. BMJ. 2021;372:m3721. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinnock H., Barwick M., Carpenter C.R. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glasgow R.E., Vogt T.M., Boles S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper C., Cole Z.A., Holroyd C.R. Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(5):1277–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1601-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mithal A, Dhingra V, Lau E. The Asian Audit: Epidemiology, costs and burden of osteoporosis in Asia 2009. Switzerland: International Osteoporosis Foundation; 2009.

- 27.Peters M., Godfrey C., McInerney P., C BaldiniSoares, Khalil H., Parker D. Chapter 11: scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. Joanna briggs institute reviewer's manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. In. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Describing interventions in EPOC reviews. EPOC resources for review authors 2017 [Available from: epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed 1 April 2020]

- 29.Jessup R.L., O'Connor D.A., Putrik P. Alternative service models for delivery of healthcare services in high-income countries: a scoping review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC taxonomy 2015 [Available from: epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy. Accessed 29 Aug 2019]

- 31.Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Scottish intercollegiate guidelines network (SIGN) methodology checklists 2012 [Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/what-we-do/methodology/checklists/. Accessed 5th October 2020]

- 32.Durlak J.A., DuPre E.P. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):327. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Public Participation Team . NHS; England: 2017. Patient and public participation policy. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore G.F., Audrey S., Barker M. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1258. h1258. https://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin J., Viprey M., Castagne B. Interventions to improve osteoporosis care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(3):429–446. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisman J.A., Bogoch E.R., Dell R. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(10):2039–2046. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amphansap T., Stitkitti N., Dumrongwanich P. Evaluation of police general hospital's fracture liaison service (PGH's FLS): the first study of a fracture liaison service in Thailand. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2016;2(4):238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bachour F., Rizkallah M., Sebaaly A. Fracture liaison service: report on the first successful experience from the Middle East. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12(1):79. doi: 10.1007/s11657-017-0372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidson E., Seal A., Doyle Z., Fielding K., McGirr J. Prevention of osteoporotic refractures in regional Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2017;25(6):362–368. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huntjens K.M.B., van Geel T.C.M., Geusens P.P. Impact of guideline implementation by a fracture nurse on subsequent fractures and mortality in patients presenting with non-vertebral fractures. Injury. 2011;42(Suppl 4):S39–S43. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(11)70011-0. 0226040, gon. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inderjeeth C.A., Raymond W.D., Briggs A.M., Geelhoed E., Oldham D., Mountain D. Implementation of the Western Australian osteoporosis model of care: a fracture liaison service utilising emergency department information systems to identify patients with fragility fracture to improve current practice and reduce re-fracture rates: a 12-month analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(8):1759–1770. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lih A., Nandapalan H., Kim M. Targeted intervention reduces refracture rates in patients with incident non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures: a 4-year prospective controlled study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(3):849–858. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]