To the Editor:

The DNA polymerase delta (Pol δ) complex, comprising the POLD1, POLD2, POLD3, and POLD4 subunits, is essential for leading and lagging DNA strand synthesis [1, 2]. The catalytic POLD1 subunit carries both polymerase and exonuclease activities and plays a crucial role in DNA replication and repair. Heterozygous POLD1 pathogenic variants have been associated with inherited colorectal cancer and mandibular hypoplasia, deafness, progeroid features, and lipodystrophy (MDPL) syndrome [3]. Recently, biallelic loss-of-function mutations in POLD1 impairing the stability of the POLδ complex have been reported in 4 subjects with recurrent infections, deafness, and combined immunodeficiency (CID) from two unrelated families [2, 4]. Here, we present a case of a patient with a novel homozygous POLD1 missense variant in POLD1 whose clinical presentation is consistent with previously described cases. We performed protein expression analysis, structural modeling, bone marrow flow cytometry, analysis of T cell development in vitro in an artificial thymic organoid (ATO) system [5], and cell cycle and DNA repair studies, revealing novel roles of POLD1 in lymphoid cell development and survival.

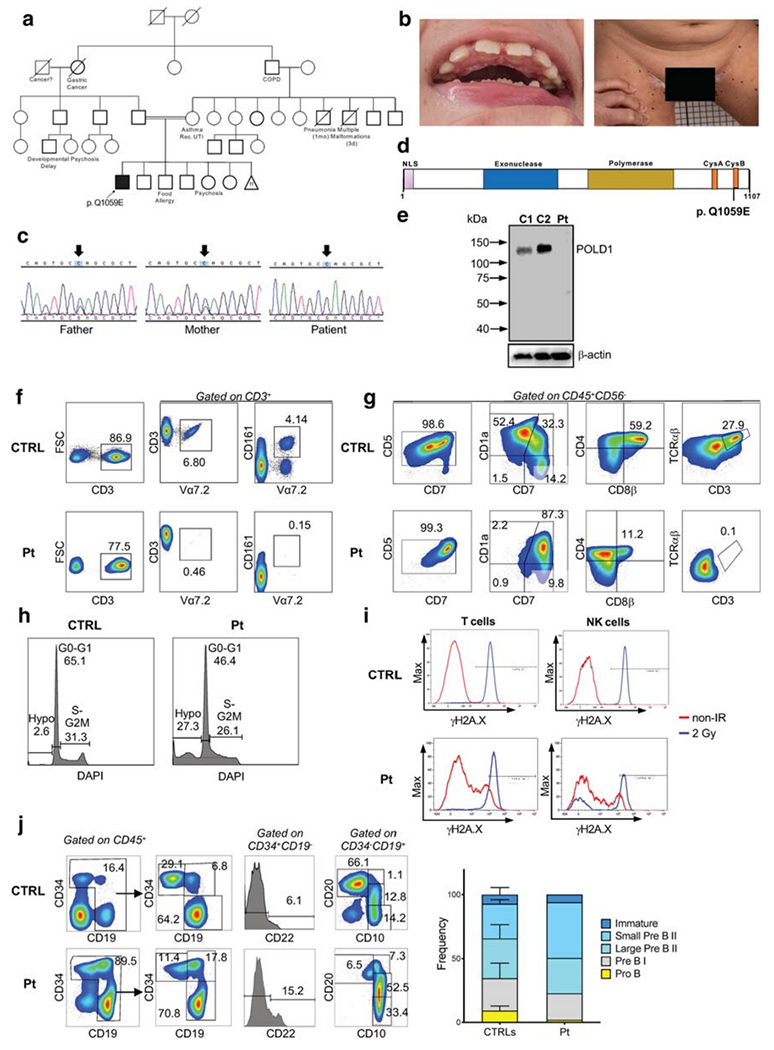

The patient is a 9-year-old boy born at term to consanguineous Pakistani parents (Fig. 1A). The patient passed his newborn hearing screening and was sent home without complications. However, since infancy, he has suffered from recurrent infections, including 5 episodes of pneumonias, multiple otitis media, sinusitis, BK viruria, one episode of shingles, and recurrent cellulitis at the G tube site (required because of failure to thrive with weight at 3rd percentile and height < 3rd percentile). Live and killed vaccines were well tolerated. At 2 years of age, profound leukopenia (absolute neutrophil count: 260 cell/μl, absolute lymphocyte count: 680 cells/μl) and hypogammaglobulinemia (420 mg/dL) were demonstrated. At 3 years of age, sensorineural hearing loss and developmental delay were diagnosed. At age 6, during hospital admission for pneumonia, immune workup revealed decreased percentage and absolute number of T cells. Although antibody titers were protective to diphtheria, tetanus, HiB, varicella, rubella, and to 8/13 pneumococcal serotypes, his infection history and previous demonstration of hypogammaglobulinemia prompted initiation of IVIG replacement therapy and antimicrobial prophylaxis. During the 2 years in which the patient was lost to follow-up, he received IVIG irregularly (every 3–6 months), prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole at suboptimal dosage, and experienced three episodes of uncomplicated pneumonias treated with oral antibiotics. He re-established clinical care, medications were appropriately adjusted, and he did not have further recurrent or severe infections. To better characterize his condition, the patient was enrolled in a research protocol (18-I-0041) approved by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) IRB. During his first visit at the NIH at age 9, short stature (height: 119.3 cm; 1st percentile), global severe developmental delay (non-verbal), teeth abnormalities, and multiple acquired nevi in the groin area were noticed (Fig. 1B). His complete blood cell count was normal except for decreased absolute lymphocyte count. Immunophenotyping showed severe T, B, and NK cell lymphopenia and hypogammaglobulinemia (Table 1). EBV viremia was detected (4.18 log10 IU/mL).

Fig. 1.

Genetic, biochemical, and functional studies in a patient with POLD1 deficiency. (A) Family pedigree. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Rec. UTI, recurrent urinary tract infections. Mother had 11 miscarriages. (B) Dental abnormalities and multiple black, flat nevi on the patient’s inner thigh surface. (C) Sanger sequencing confirmation of the POLD1 variant. Arrows designate the mutated nucleotide. (D) Domain structure of POLD1 showing the nuclear localization signal (NLS), the exonuclease domain, the polymerase domain, the cysteine-rich, metal-binding domains CysA and CysB, and location of the Q1059E mutation site. (E) Immunoblotting of POLD1 and β-actin protein expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cell lysates from the patient (Pt) and two healthy controls (C1, C2). (F) Representative FACS plot from a healthy control (CTRL) and patient (P), showing the frequency of Vα7.2 and MAIT (Vα7.2+CD161+) cells upon gating on CD3+ cells. (G) In vitro T cell differentiation of bone marrow–derived CD34+ CD3− cells from a healthy control (CTRL) and the patient (Pt) after 6 weeks of culture in an artificial thymic organoid (ATO) system. FACS plots show expression of early and late T cell differentiation markers CD7, CD5, CD1a, CD4, CD8β, TCRαβ, and CD3 upon gating on LIVE/DEAD− CD45+ CD56− cells. (H) The histograms show the distribution of cells in the different phases of cell cycle after cell staining for DNA content (DAPI) in a healthy control (CTRL) and in the patient (Pt), upon gating on total CD45+ CD56− cells during differentiation in the ATO system. (I) Flow cytometric analysis showing γH2AX expression in unirradiated conditions and at 1-h post irradiation (2Gy) in rested PBMCs from a healthy control (CTRL) and the patient (Pt). Gating was done on CD3+ T cells (left panels) and on CD56/CD16+ CD3− NK cells (right panels) (J) Flow cytometric analysis of the distribution of cells at various stages of B cell differentiation in the bone marrow aspirate from a healthy control (CTRL) and the patient (Pt). Upon gating on CD45+ cells, pro-B cells were identified as CD34+ CD19− CD22+, and pre-BI cells were identified as CD34+ CD19+ cells. Expression of CD10 and CD20 upon gating on CD45+ CD34− CD19+ cells identifies small pre-BII (CD10+ CD20), Urge pre-BII (CD10+ CD20dim), and immature (CD 10+ CD20+) B cells. (L) Bar graphs show cumulative frequency of B cell developmental stages in 3 healthy controls (CTRLs) and in the patient (Pt). Bars identify standard deviation

Table 1.

Immunological parameters

| Parameter | Patient (9 years) | Normal reference values |

|---|---|---|

| WBC (cells/μL) | 2.41 | 4.31–11.00 |

| ANC (cells/μL) | 1.72 | 1.63–7.55 |

| ALC (cells/μL) | 0.29 | 0.97–3.96 |

| CD3+ (cells/μL) | 122 | 651–2804 |

| CD4+ (cells/μL) | 68 | 370–1336 |

| Naïve CD4+ CD45RA+ CD62L+ (cells/μL) | 20 | 87–796 |

| CM CD4+ CD45RA− CD62L+ (cells/μL) | 35 | 166–544 |

| EM CD4+ CD45RA− CD62L− (cells/μL) | 13 | 80–262 |

| CD8+ (cells/μL) | 39 | 185–1024 |

| Naïve CD8+ CD45RA+ CD62L+ (cells/μL) | 18 | 37–484 |

| CM CD8+ CD45RA− CD62L+ (cells/μL) | 4 | 19–175 |

| EM CD8+ CD45RA− CD62L− (cells/μL) | 14 | 47–383 |

| TEMRA CD8+ CD45RA+ CD62L− (cells/μL) | 2 | 17–274 |

| Treg (CD4+ CD25hi FOXP3+) (cells/μL) | 13 | 27–122 |

| CD20+ (cells/μL) | 143 | 79–399 |

| CD3− CD16/56+ (cells/μL) | 24 | 126–481 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 742* | 572–1474 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 19 | 34–305 |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 12 | 32–208 |

| IgE (IU/mL) | 3.8 | 1.18–5.33 |

ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CM, central memory; EM, effector memory, TEMRA, effector memory CD45RA+ T cells; WBC, white blood cell count

On IVIG replacement therapy

Abnormal values are indicated in italics

To search for a possible inborn error of immunity, whole exome sequencing (WES) was ordered for the patient and his biological parents. A homozygous POLD1 missense variant was identified in the patient (NM_001256849 c.3175C>G, p.Q1059E), which is absent in public databases (gnomAD, ExAC, dbSNO, or 1000 Genomes Project databases). Sanger sequencing confirmed that the patient is homozygous, and both healthy parents are heterozygous for the POLD1 variant (Fig. 1C). The p.Q1059E variant is located in the conserved CysB motif, spanning amino acids 1058 to 1076 in the C-terminal region (Fig. 1D). This motif coordinates a [4Fe-4S] cluster with roles in recruitment of accessory subunits (Fig. S1) [6]. We used a 3D model of the POLD1 complex [PMID 32111820] in stability [7] and electrostatic [8] calculations. The Q1059E variant changes the POLD2 surface from neutral to electronegative (Fig. S2) and destabilizes the complex interface according to our structure-based calculation (ΔΔG = 1.79 kcal/mol). The Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score of the POLD1 variant is 24, higher than the Mutation Significance Cut-off (MSC) score, which for the POLD1 gene is 23.1 (Fig. S3). Immunoblot analysis revealed normal POLD1 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy controls, but no protein expression was detected in the patient, suggesting that the variant affects protein stability (Fig. 1E).

Similar to previously published cases, our patient manifested profound T cell lymphopenia (Table 1). In order to investigate whether this is contributed by impaired thymic T cell development, we stained CD3+ T cells with the monoclonal Vα7.2 antibody, recognizing the very upstream TRAV1-2 gene. DNA rearrangements at the T cell receptor α (TRA) locus occur sequentially, and only thymocytes that survive long enough are able to rearrange the most upstream TRAV genes [9, 10]. The proportion of T cells expressing Vα7.2 was markedly reduced (0.3%) in the patient as compared to 32 healthy controls (mean ± s.d., 4.4 ± 2.1), consistent with defective thymocyte survival (Fig. 1F). To further investigate whether POLD1 deficiency affects T cell development and/or survival, we differentiated CD34+CD3− bone marrow cells from the patient and a healthy control into T cells in the ATO system [5]. A block in T cell differentiation at the CD1a+ stage was observed in the patient, resulting in a reduced number of double-positive CD4+CD8+ cells and almost complete absence of TCRαβ+CD3+ cells generated after 6 weeks of culture (Fig. 1G). This defect was associated with increased apoptosis, as shown by an increased proportion of DAPIlow hypodiploid cells among total CD45+CD56− cells (Fig. 1H), indicating the presence of impaired DNA repair, consistent with POLD1 function [2, 11]. To assess whether replication stress in patient’s cells would lead to double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs), we analyzed phosphorylation of histone H2AX (γH2AX) by flow cytometry, in the presence or absence of induced DNA DSBs, in individual lymphocyte subsets [12]. Increased spontaneous γH2AX expression was observed in T and NK cells after 1 h of culture in unirradiated conditions, indicating constitutive DNA damage (Fig. 1I). Furthermore, 1 h after irradiation (2Gy), a subset of the patient’s NK cells showed defective γH2AX expression, indicative of impaired DNA damage response (Fig. 1I), in contrast to the healthy experimental control. The patient’s B cells also showed a small subset, which are unable to phosphorylate ATM, a key DNA DSB sensor and transducer, or H2AX (data not shown).

Similar to previously reported cases of POLD1 deficiency [2, 4], our patient had a normal number of circulating B cells (Table 1). However, flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow [13] showed an increased proportion of small pre-B II cells (Fig. 1J). This feature has not been described before and suggests a possible role of POLD1 also in B cell maturation.

In summary, we report a new case of autosomal recessive POLD1 combined immunodeficiency. The studies performed have broadened the understanding of the mechanisms underlying the immune defects in this disease to include impaired T cell development and survival, resulting in a restricted TCR repertoire, and a subtle defect in B cell differentiation. While the DNA repair defect observed in this and previous patients may predispose to increased risk of malignancy, the natural history of the disease is still incompletely characterized and will need to be resolved in future case series.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient and his parents, and healthy volunteers, participating in this work.

Funding

This study was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-020-00903-6.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Donnianni RA, Zhou ZX, Lujan SA, Al-Zain A, Garcia V, Glancy E, et al. DNA polymerase delta synthesizes both strands during break-induced replication. Mol Cell. 2019;76(3):371–81 e4. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conde CD, Petronczki OY, Baris S, Willmann KL, Girardi E, Salzer E, et al. Polymerase delta deficiency causes syndromic immunodeficiency with replicative stress. J Clin Invest. 2019; 129(10): 4194–206. 10.1172/JCI128903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elouej S, Beleza-Meireles A, Caswell R, Colclough K, Ellard S, Desvignes JP, et al. Exome sequencing reveals a de novo POLD1 mutation causing phenotypic variability in mandibular hypoplasia, deafness, progeroid features, and lipodystrophy syndrome (MDPL). Metabolism. 2017;71:213–25. 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui Y, Keles S, Charbonnier LM, Jule AM, Henderson L, Celik SC, et al. Combined immunodeficiency caused by a loss-of-function mutation in DNA polymerase delta 1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020; 145(1):391–401 e8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosticardo M, Pala F, Calzoni E, Delmonte OM, Dobbs K, Gardner CL, et al. Artificial thymic organoids represent a reliable tool to study T-cell differentiation in patients with severe T-cell lymphopenia. Blood Adv. 2020;4(12):2611–6. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Netz DJ, Stith CM, Stumpfig M, Kopf G, Vogel D, Genau HM, et al. Eukaryotic DNA polymerases require an iron-sulfur cluster for the formation of active complexes. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;8(1):125–32. 10.1038/nchembio.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schymkowitz J, Borg J, Stricher F, Nys R, Rousseau F, Serrano L. The FoldX web server: an online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W382–8. 10.1093/nar/gki387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10037–41. 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berland A, Rosain J, Kaltenbach S, Allain V, Mahlaoui N, Melki I, et al. PROMIDISalpha: a T-cell receptor alpha signature associated with immunodeficiencies caused by V(D)J recombination defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019; 143(1):325–34 e2. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo J, Hawwari A, Li H, Sun Z, Mahanta SK, Littman DR, et al. Regulation of the TCRalpha repertoire by the survival window of CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocytes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(5):469–76. 10.1038/ni791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brocas C, Charbonnier JB, Dherin C, Gangloff S, Maloisel L. Stable interactions between DNA polymerase delta catalytic and structural subunits are essential for efficient DNA repair. DNA Repair (Amst). 2010;9(10): 1098–111. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cousin MA, Smith MJ, Sigafoos AN, Jin JJ, Murphree MI, Boczek NJ, et al. Utility of DNA, RNA, protein, and functional approaches to solve cryptic immunodeficiencies. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38(3): 307–19. 10.1007/s10875-018-0499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noordzij JG, de Bruin-Versteeg S, Comans-Bitter WB, Hartwig NG, Hendriks RW, de Groot R, et al. Composition of precursor B-cell compartment in bone marrow from patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia compared with healthy children. Pediatr Res. 2002;51(2): 159–68. 10.1203/00006450-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.