Key Points

Question

What genetic loci are associated with acute appendicitis (AA)?

Findings

In this genome-wide association study, a genetic locus at chromosome 18q was found to be associated with AA, located in the NEDD4L gene. NEDD4L was also among the top differentially expressed genes in appendiceal tissue between AA patients and controls.

Meaning

This study suggests that NEDD4L variations are associated with the development of AA; these findings can improve understanding of the genetic predisposition to and pathogenesis of AA.

Abstract

Importance

The familial aspect of acute appendicitis (AA) has been proposed, but its hereditary basis remains undetermined.

Objective

To identify genomic variants associated with AA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This genome-wide association study, conducted from June 21, 2019, to February 4, 2020, used a multi-institutional biobank to retrospectively identify patients with AA across 8 single-nucleotide variation (SNV) genotyping batches. The study also examined differential gene expression in appendiceal tissue samples between patients with AA and controls using the GSE9579 data set in the National Institutes of Health’s Gene Expression Omnibus repository. Statistical analysis was conducted from October 1, 2019, to February 4, 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Single-nucleotide variations with a minor allele frequency of 5% or higher were tested for association with AA using a linear mixed model. The significance threshold was set at P = 5 × 10−8.

Results

A total of 29 706 patients (15 088 women [50.8%]; mean [SD] age at enrollment, 60.1 [17.0] years) were included, 1743 of whom had a history of AA. The genomic inflation factor for the cohort was 1.003. A previously unknown SNV at chromosome 18q was found to be associated with AA (rs9953918: odds ratio, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.00; P = 4.48 × 10−8). This SNV is located in an intron of the NEDD4L gene. The heritability of appendicitis was estimated at 30.1%. Gene expression data from appendiceal tissue donors identified NEDD4L to be among the most differentially expressed genes (14 of 22 216 genes; β [SE] = −2.71 [0.44]; log fold change = −1.69; adjusted P = .04).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study identified SNVs within the NEDD4L gene as being associated with AA. Nedd4l is involved in the ubiquitination of intestinal ion channels and decreased Nedd4l activity may be implicated in the pathogenesis of AA. These findings can improve the understanding of the genetic predisposition to and pathogenesis of AA.

This genome-wide association study examines genomic variants associated with acute appendicitis.

Introduction

Acute appendicitis (AA) is a common disease, affecting nearly 7% of the population in the United States.1 The cause of AA remains unclear, with traditional hypotheses suggesting that luminal obstruction from fecaliths or lymphoid hyperplasia is the inciting factor.2 When pathologic specimens are examined, obstructed lumen and fecaliths are not routinely found.3,4,5 Alternative pathogenetic theories have focused on the role of the intestinal microbiome6,7,8,9 and dietary habits10,11 as factors associated with the occurrence of AA.

Genetics is believed to also play a role in the pathogenesis of AA, with a family history of AA increasing the odds of AA 2- to 3-fold.12,13 Families with exceptionally high incidence and clustering of AA have also been described, further indicating a potential genetic component.14 More recently, 3 independent genome-wide association studies (GWASs) of AA were performed.15,16 An association between PITX2 (OMIM 601542) and AA was present in the 23andMe16 and Icelandic15 cohorts but not the Dutch cohort,15 suggesting that inheritance is complex or multifactorial. Studies so far suggest that data from different populations are needed to validate previous associations and identify additional loci because, in populations such as the Dutch cohort, loci other than chromosome 4q25 may play an important role in the development of AA. In addition, the precise mechanism that associates PITX2 variations with the pathogenesis of AA remains unclear, and studies are needed to help us better understand AA pathogenesis. We aimed to identify genetic loci associated with the development of AA in a US cohort.

Methods

Setting

This GWAS was conducted from June 21, 2019, to February 4, 2020. Participants were prospectively enrolled in the Partners Healthcare Biobank Project, a repository of biological samples from patients admitted to any of the institutions of the Mass General Brigham integrated health care network. The purpose of the Biobank is to study the association between genetic factors and human disease.17 To date, 117 490 participants have enrolled in the Biobank, after voluntarily signing a written informed consent form, and 36 423 have been genotyped. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mass General Brigham health care network.

Genotyping of Participants

Participants were genotyped at facilities of the Mass General Brigham integrated health care network using 3 different versions of Illumina’s Multi-Ethnic Global arrays (Illumina Inc). More details on the genotyping of participants can be found in the eMethods in the Supplement. The participants from each batch were analyzed separately to minimize batch effects. Imputation was performed using the Michigan Imputation server18 and the algorithm Minimac3. The HRC (Haplotype Reference Consortium), version r1.1 2016 reference panel was used for imputation, and haplotype phasing was implemented using SHAPEIT19 (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Phenotype Data

A history of AA was retrospectively assessed based on information from the electronic medical record. Inpatient and outpatient notes that matched the key words “appendectomy,” “appendicitis,” or “appy” were evaluated manually for a history of AA or appendectomy. Appendectomies that were performed for an indication other than AA (eg, appendiceal cancer) and those performed incidentally during other abdominal operations were excluded. There were no missing data regarding the phenotype; no participants were lost to follow-up. Case selection can be viewed in eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Quality Control

Preimputation quality control steps involved the filtering out of single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) with low call rates (<99%); allele mismatch; or duplicate, monomorphic, or invalid alleles. Duplicated participants and participants with discordant sex information were also filtered out. Related individuals were identified based on a genetic relationship greater than 0.1875, which corresponds to halfway between second- and third-degree relatives. After imputation, 1 individual from each pair of related individuals was excluded using GCTA (Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis), version 1.91.1. To assess whether the identified region deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, which could be associated with genotyping errors, we performed the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test using PLINK, version 1.90.20

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted from October 1, 2019, to February 4, 2020. Quality control was performed using PLINK, version 1.90.20 The minor allele frequency was set at 5%. Plots were generated on R, version 3.4 (R Group for Statistical Computing) with qqman21 and LocusZoom.22 Mixed linear model–based association analysis (eMethods in the Supplement) was performed to identify genomic regions associated with AA using GCTA, version 1.91.1.23,24 Population stratification was adjusted for using principal component analysis. The first 10 eigenvectors were included as covariates in the mixed-linear model. Control for residual population structure was accounted for in the mixed-linear model. To assess whether differences in ethnicity between the 2 groups were associated with our results, a separate analysis was performed that was restricted to patients of European descent. European descent was assessed by the investigators after superimposition of our cohort on a population of known ethnic ancestry (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Sufficient control for population stratification was confirmed by evaluating the Q-Q plot and the genomic inflation factor. Other covariates included in the model were age, sex, smoking status, obesity, and alcohol use. Meta-analysis was performed on PLINK, version 1.07 using both fixed-effects and random-effects models, in which the results of association analysis from each individual batch were combined. Only SNVs that were present in all 8 batches were examined. The threshold of significance was set at P = 5 × 10−8, which is the commonly accepted threshold used in GWASs.25,26,27 Positions in chromosomes for genomic regions are denoted based on the hg19 assembly (GRCh37.p13). Heterogeneity for the meta-analysis results was assessed with the I2 statistic.28

The proportion of variance explained by the genetics of AA was estimated using restricted maximum likelihood analysis, which is based on the genetic relationship matrix for each batch. Single-nucleotide variations with a minor allele frequency of 1% or higher were considered for this analysis. The prevalence of AA in the general population was considered at 7%, based on epidemiologic studies in the US population1 (eMethods in the Supplement).

Differentially Expressed Genes Between Patients With AA and Controls

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were assessed in the appendiceal tissue, as well as the sera, of patients with AA (Gene Expression Omnibus repository: GSE95799,29) and controls (Gene Expression Omnibus repository: GSE8309130,31). The GSE9579 data were derived by analyzing the appendiceal gene expression of 9 patients with AA and 4 controls using the Affymetrix Human Genome U133A 2.0 Array (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The 4 controls underwent resection of the appendix for indications other than AA (3 patients underwent the Ladd procedure for intestinal malrotation; 1 patient received a cecal conduit for refractory constipation).9 The GSE83091 data were derived by analyzing peripheral serum RNA of 21 patients with AA and 19 controls using the Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 expression beadchip (Illumina Inc). The 19 controls had pneumonias or other intra-abdominal processes (eg, acute pancreatitis, small-bowel obstruction, urolithiasis, diverticulitis, or abdominal wall hernias). Data from each set were collected in the same batch, and gene expression profiles were assessed using the same array. Differentially expressed genes were assessed the using GEO2R platform32 (eMethods in the Supplement). For this analysis, correction for multiple comparisons was performed using the false discovery rate method as executed in GEO2R using a 5% false discovery rate.

Results

Characteristics of Participants

A total of 29 706 participants (15 088 women [50.8%]; mean [SD] age at enrollment, 60.1 [17.0] years) were included in the study, among whom 1743 had an AA history and 27 963 were used as controls (Table 1). The mean (SD) age at enrollment was 64.5 (15.4) years for the AA group and 59.6 (16.9) years for the control group (P < .001). Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the patients with AA as well as the control group. The sex distribution was similar in the 2 groups (872 female participants [50.0%] and 871 male participants [50.0%] in the AA group vs 14 216 female participants [50.8%] and 13 747 male participants [49.2%] in the control group; P = .51). The participants in the AA group were more likely to be smokers (426 [24.4%] vs 6131 [21.9%]; P = .01) and have obesity compared with the participants in the control group (281 [16.1%] vs 3589 [12.8%]; P < .001). The characteristics of the cohort after restriction to those of European descent can be found in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Cohort Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute appendicitis (n = 1743) | Controls (n = 27 963) | ||

| Age at enrollment, mean (SD), y | 64.5 (15.4) | 59.6 (16.9) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 872 (50.0) | 14 216 (50.8) | .51 |

| Male | 871 (50.0) | 13 747 (49.2) | |

| Smoking | 426 (24.4) | 6131 (21.9) | .01 |

| Obesity | 281 (16.1) | 3589 (12.8) | <.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 41 (2.4) | 596 (2.1) | .54 |

Results of Association Analysis for AA

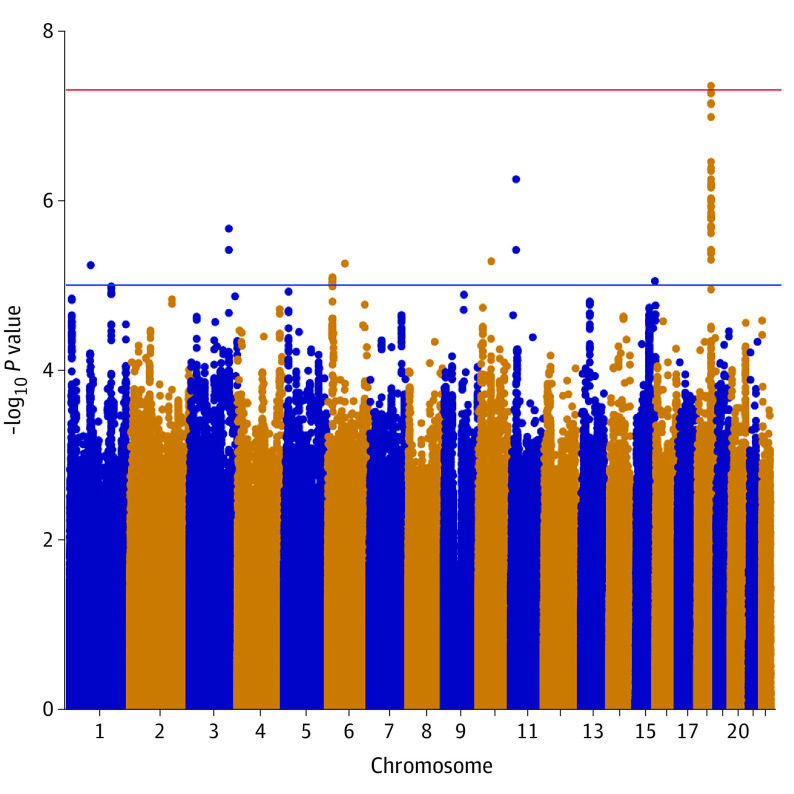

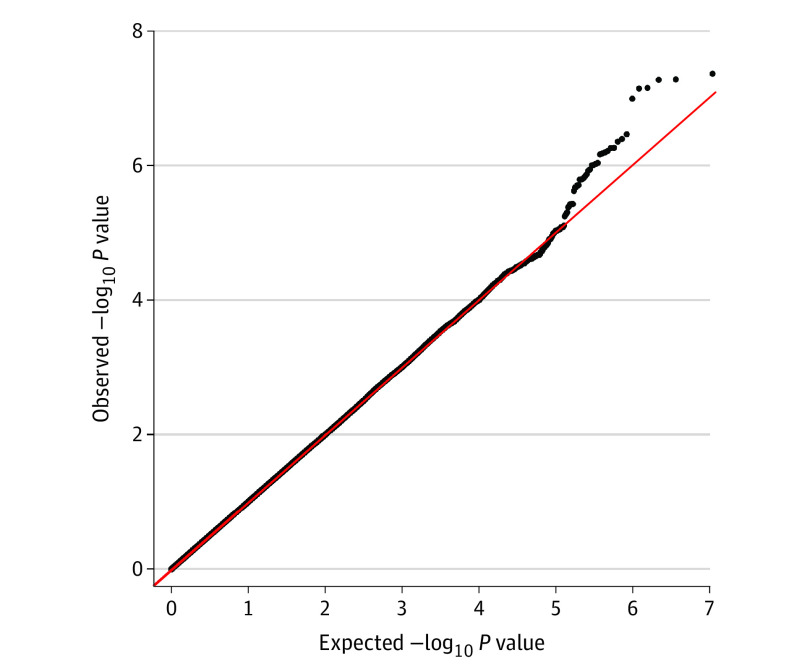

An area in the coding region of the NEDD4L gene (OMIM 606384) (chromosome 18q) was identified to be associated with AA (rs9953918: odds ratio [OR], 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.00; fixed-effects meta-analysis P = 4.48 × 10−8, random-effects meta-analysis P = 4.48 × 10−8; I2 = 0) (Table 2). The genomic inflation factor for the cohort was 1.003. All SNVs in the identified region that had a P < 1 × 10−5 had a minor allele frequency higher than 5% in all 8 batches. All SNVs with P < 1 × 10−8 are located in introns of NEDD4L (Table 2; eTable 3 in the Supplement). The Manhattan plot is displayed in Figure 1, and the Q-Q plot in Figure 2. A locus plot of the identified region and the corresponding genes is displayed in eFigure 3 in the Supplement. The same results were observed in a subanalysis of participants of European ancestry (eFigures 4, 5, and 6 in the Supplement). The proportion of phenotypic variance explained by genetics was calculated at 30.1%. A logistic regression model incorporating all covariates of the association analysis had a pseudo-R2 of 0.0120. All identified SNVs passed the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test (P > .40).

Table 2. Results of Association Analysis for Variants.

| Chromosome | Position (based on hg19 assembly) | SNV | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | OR (95% CI) | P value | I2, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | Random effects | |||||||

| 18 | 56005645 | rs9953918 | G | A | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 4.48 × 10−8 | 4.48 × 10−8 | 0 |

| 18 | 56000724 | rs8089678 | G | A | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 5.50 × 10−8 | 5.50 × 10−8 | 0 |

| 18 | 55999499 | rs9944723 | A | G | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 5.44 × 10−8 | 5.44 × 10−8 | 0 |

| 18 | 56004914 | rs9962106 | T | C | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 7.39 × 10−8 | 7.39 × 10−8 | 0 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; SNV, single-nucleotide variation.

Figure 1. Manhattan Plot Demonstrating a Region Associated With Acute Appendicitis at Chromosome 18q.

Each chromosome is displayed on the x-axis, and the −log10 P value for the association of each single-nucleotide variation with acute appendicitis is displayed on the y-axis.

Figure 2. Q-Q Plot Demonstrating Uniform Distribution of Observed and Expected P Values.

The upper tail represents the identified single-nucleotide variations of chromosome 18q that deviate from the expected null distribution. The diagonal red line indicates the normal distribution.

Analysis of several large cohorts showed that rs9953918 is a relatively common variation that is present across multiple populations (eMethods in the Supplement). Data on the frequencies of rs9953918 across different populations are shown in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

The previously identified region at chromosome 4q25 did not exceed the threshold of significance (rs2129979: OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01; P = .04), but the P value was comparable to that described in the Dutch cohort.15 We also used a standard logistic regression model as implemented in PLINK to investigate the same loci. The P values were similar, but, as expected, the ORs were more pronounced with this method (rs2129979: OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.94-1.21; P = .07; rs9953918: OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.72-0.92; P = 4.54 × 10−8).

NEDD4L Expressed in Human Appendiceal Tissue

Analysis of 6 samples (3 female participants and 3 male participants) from the GSE1133, GSE2109, and GSE5791 data sets demonstrated that NEDD4L is expressed in the appendix at the messenger RNA (mRNA) level (eMethods in the Supplement). The mean (SD) signal among the 6 samples was 577.1 (259.4) (range, 354.7-1066.5) (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Data from the Human Protein Atlas demonstrated that the Nedd4l protein is present in glandular cells of the appendix.

Appendiceal NEDD4L mRNA Differentially Expressed Between Patients With AA and Controls

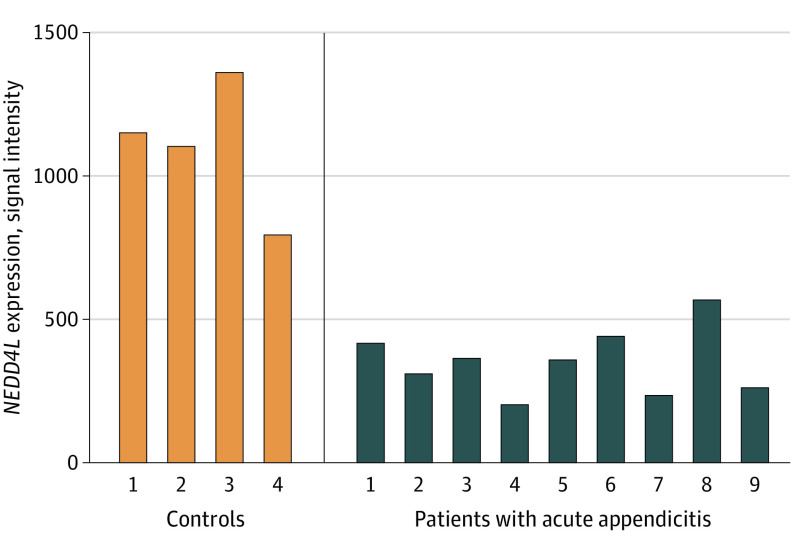

An analysis to identify DEGs between patients with AA and controls was performed. First, we identified DEGs in the appendiceal tissues of 9 patients with AA (3 male patients and 6 female patients) and 4 controls (3 male controls and 1 female control). NEDD4L was among the top DEGs (14 of 22 216 genes; β [SE] = 2.71 [0.44]; log fold change = −1.69; adjusted P = .04; Figure 3; eTable 6 in the Supplement). All 9 patients with AA had lower NEDD4L mRNA expression compared with the 4 controls (eTable 7 in the Supplement). PITX2, which has been found to be associated with AA, was not among the top DEGs (β [SE] = −1.78 [0.51]; log fold change = −1.62; adjusted P = .15).

Figure 3. Appendiceal NEDD4L Messenger RNA Expression in Individual Samples of Patients With Acute Appendicitis and Controls.

Finally, we assessed DEGs from peripheral blood RNA of 21 patients with AA (13 female patients and 8 male patients) and 19 controls (8 female controls and 11 male controls). NEDD4L was not differentially expressed among the 2 groups (β [SE] = −4.63 [249.14]; log fold change = 0.003; adjusted P ≥ .99; eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This study identified a new locus at chromosome 18q, in the intronic region of the NEDD4L gene, associated with AA. The heritability of AA was estimated at 30.1%. Analysis of differential gene expression from appendiceal RNA sequencing of patients with AA and controls showed that NEDD4L is among the top DEGs, which further supports a role for NEDD4L in AA. These findings are important because they may help us better understand the heritability and pathogenesis of AA.

The NEDD4L locus has not been described previously in association with AA, to our knowledge. Two previous GWASs have been conducted to identify genetic loci for AA in different populations. Kristjansson and colleagues15 performed a GWAS in Icelandic and Dutch populations and identified a locus in a noncoding region close to PITX2 on chromosome 4q25. This region was significant in the Icelandic cohort but not the Dutch cohort. This signal was later validated in a study by Orlova and colleagues16 using the 23andMe cohort. The authors of the latter study also conducted an RNA sequencing analysis, in which they demonstrated that PITX2, UBA7 (OMIM 191325), CD53 (OMIM 151525), and RHOA (OMIM 165390) are differentially expressed across uninflamed, mildly inflamed, severely inflamed, and perforated appendicitis in pediatric patients.16 Although PITX2 had differential expression among these 4 groups, there were no differences between the groups with uninflamed and inflamed appendicitis, a finding that was also validated in our analysis of appendiceal DEGs.

Our findings regarding chromosome 4q45 are comparable to those described for the Dutch cohort, in which the P value for rs2129979 was less than .05 but did not exceed the genome-wide threshold of significance.15 This finding shows that, in populations such as the Dutch cohort and our own, genetic loci other than chromosome 4q25 may play a more important role in the development of AA compared with the 23andMe and Icelandic populations, where chromosome 4q25 appears to play a major role. The relatively small ORs of our study are associated with our use of mixed linear model–based association analysis. After using a standard logistic regression model, our ORs are similar to those previously reported for chromosome 4q25, whereas the effect size for chromosome 18q is also more pronounced with this approach. These observations are explained by the fact that mixed linear model–based association analysis takes into consideration the entire genome, so the observed effect sizes are expected to be smaller. The heritability of AA is estimated to be high at 30.1%, in agreement with previous twin studies, which had estimated the heritability of AA to be between 21% and 56%.33,34,35 The SNVs that we associate here with AA are common in the general population. This observation, along with the small effect sizes, suggests that AA has a complex inheritance. In the future, whole-genome sequencing studies may reveal more rare variants with larger effect sizes associated with AA or higher penetrance.

The identification of the role of NEDD4L in AA may provide valuable insights into the pathogenesis of AA. The protein product of NEDD4L, Nedd4l, functions as an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, which ubiquinates various targets for proteasomal degradation. The Nedd4l enzyme targets several ion channels for degradation, including ENaC36 and the Na/K/2Cl co-transporter (or NKCC1),37 as well as aquaporins.38 It consists of a C2 domain (Ca2+ and lipid binding), 4 WW domains (substrate binding), and a HECT domain (ligase activity).39 The identified SNV, rs9953918, is located between exons 12 and 13 of NEDD4L, while SNVs rs9953918 and rs9953918, which had a statistical significance of P < 1 × 10−8, are located between exons 11 and 12. Exons 11, 12, and 13 code the proline-binding WW domains, whose primary function is to bind protein substrates.40 Alternative splicing of these domains has been shown to reduce binding capacity to ENaC and is associated with higher ENaC activity.41

These findings suggest that the identified genetic variations may be associated with higher activity of ion channels, such as ENaC and NKCC1, which may then generate greater luminal reabsorption of Na+ and water down the osmotic gradient. This mechanism has previously been described in colon-specific NEDD4L conditional knockout mice; knockout mice manifested greater ENaC- and NKCC1-dependent luminal Na+ reabsorption compared with wild-type mice.37 Decreased luminal Na+ and water concentrations may result in thickening of the luminal contents and subsequent obstruction. Luminal content thickening and obstruction have been observed in lung-specific NEDD4L-conditional knockout mice, in which no Nedd4l activity is associated with thickened lung secretions and a cystic fibrosis–like pulmonary disease.42 Bacterial superinfection of the obstructed appendix may eventually instigate AA.

These observations suggest a biologically plausible mechanism underlying the genetic predisposition to AA. This raises the question of what may serve as a secondary environmental insult in these individuals to trigger the acute onset of appendicitis. Important clues can be derived from colon-specific NEDD4L knockout mice. A low-salt diet induces equal elevations of NKCC1 mRNA in both knockout and wild-type mice but a much higher concentration of NKCC1 protein in knockout compared with wild-type mice.37 A higher concentration of NKCC1 protein may result in greater luminal ion and water reabsorption, which may represent an evolutionary mechanism to maintain electrolyte reabsorption during periods of low intake. A low-salt diet may be associated with higher luminal Na+ reabsorption in genetically predisposed individuals compared with controls and a higher likelihood for luminal obstruction.

Future studies are needed to further characterize the association between a low-salt diet and AA in genetically predisposed individuals. In addition, future studies are needed to better understand environmental factors associated with AA because they accounted for 70% of phenotypic variance in our study. Our analysis accounted for several environmental factors, but the environmental risk factors for AA are largely unknown.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. It is a meta-analysis of 8 separate cohorts, and replication in an independent cohort might be needed to further validate our findings. Different SNV arrays were used to genotype our patients, which may introduce batch effects, but we used a meta-analysis to address this possibility. Our analysis also did not include loci in sex chromosomes. Furthermore, our study was not able to validate an association between chromosome 4q25 and AA, and previous GWASs have not reported a signal at chromosome 18q associated with AA. However, our findings were validated with RNA sequencing of appendiceal tissue because NEDD4L was among the top DEGs between patients with AA and controls.

Nevertheless, more studies are needed to better define the genomic landscape of AA. In particular, future studies for individuals of non-European ethnic ancestry are needed to better characterize the genomic landscape of AA in these populations, which are often underrepresented in GWASs. Age at enrollment, instead of age at diagnosis, was used as a covariate in the association analysis because the latter was not available for most patients through retrospective medical record review. Finally, several environmental covariates included in the analysis were based on information collected at the time of biobank enrollment, and these factors (eg, smoking) may not have been associated with the development of AA, especially among patients who developed AA during childhood.

Conclusions

We have identified a locus at chromosome 18q that is associated with AA, with an estimated heritability of 30.1%. The identified genetic locus is located in the introns of NEDD4L, which was among the top DEGs in an analysis of RNA sequencing data from appendiceal tissue of patients with AA and controls. Nedd4l is involved in the ubiquitination of intestinal ion channels, and decreased Nedd4l activity may be implicated in the pathogenesis of AA. Future studies are needed to further characterize the genomic landscape and pathogenesis of AA.

eMethods.

eReferences.

eTable 1. Detailed Information on Individual Genotyping Batches

eTable 2. Characteristics of Subjects of European Descent

eTable 3. Results of Association Analysis for rs9953918 for Individual Batches

eTable 4. Frequency of rs9953918 in Various Populations

eTable 5. Expression of NEDD4L in Human Appendix

eTable 6. Results of Association Analysis for Top DEGs Between AA Patients and Controls

eTable 7. Differential Expression of NEDD4L in Appendiceal Tissue of Patients With AA and Controls

eTable 8. Top DEGs From Peripheral Blood RNA Between AA Patients and Controls

eFigure 1. Detailed Inclusion-Exclusion Information

eFigure 2. Plot for MDS (Multidiamensional Scaling) Demonstrating Restriction to European Ancestry

eFigure 3. Locus Plot of the Identified Region at 18q

eFigure 4. Manhattan Plot Region Showing the Region at Chromosome 18q to be Associated With Acute Appendicitis Among Subjects of European Ancestry

eFigure 5. QQ Plot for the Analysis Among Subjects of European Descent Demonstrating Uniform Distribution of Observed and Expected P Values

eFigure 6. Locus Plot for the Analysis Among Subjects of European Descent

References

- 1.Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910-925. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holcomb GW, Murphy JP. Ashcraft’s Pediatric Surgery. Saunders/Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JP, Mariadason JG. Role of the faecolith in modern-day appendicitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(1):48-51. doi: 10.1308/003588413X13511609954851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandrasegaram MD, Rothwell LA, An EI, Miller RJ. Pathologies of the appendix: a 10-year review of 4670 appendicectomy specimens. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82(11):844-847. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr NJ. The pathology of acute appendicitis. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4(1):46-58. doi: 10.1016/S1092-9134(00)90011-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swidsinski A, Dörffel Y, Loening-Baucke V, et al. Acute appendicitis is characterised by local invasion with Fusobacterium nucleatum/necrophorum. Gut. 2011;60(1):34-40. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.191320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson HT, Mongodin EF, Davenport KP, Fraser CM, Sandler AD, Zeichner SL. Culture-independent evaluation of the appendix and rectum microbiomes in children with and without appendicitis. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong D, Brower-Sinning R, Firek B, Morowitz MJ. Acute appendicitis in children is associated with an abundance of bacteria from the phylum Fusobacteria. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(3):441-446. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy CG, Glickman JN, Tomczak K, et al. Acute appendicitis is characterized by a uniform and highly selective pattern of inflammatory gene expression. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(4):297-308. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adamidis D, Roma-Giannikou E, Karamolegou K, Tselalidou E, Constantopoulos A. Fiber intake and childhood appendicitis. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2000;51(3):153-157. doi: 10.1080/09637480050029647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnbjörnsson E. Acute appendicitis and dietary fiber. Arch Surg. 1983;118(7):868-870. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390070076015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ergul E. Heredity and familial tendency of acute appendicitis. Scand J Surg. 2007;96(4):290-292. doi: 10.1177/145749690709600405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauderer MW, Crane MM, Green JA, DeCou JM, Abrams RS. Acute appendicitis in children: the importance of family history. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(8):1214-1217. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.25765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simó Alari F, Gutierrez I, Gimenéz Pérez J. Familial history aggregation on acute appendicitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr-2016-218838. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-218838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristjansson RP, Benonisdottir S, Oddsson A, et al. Sequence variant at 4q25 near PITX2 associates with appendicitis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3119. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03353-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orlova E, Yeh A, Shi M, et al. ; 23andMe Research Team . Genetic association and differential expression of PITX2 with acute appendicitis. Hum Genet. 2019;138(1):37-47. doi: 10.1007/s00439-018-1956-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gainer VS, Cagan A, Castro VM, et al. The Biobank Portal for Partners Personalized Medicine: a query tool for working with consented Biobank samples, genotypes, and phenotypes using i2b2. J Pers Med. 2016;6(1):11. doi: 10.3390/jpm6010011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michigan Imputation Server. Free next-generation genotype imputation service. Accessed June 14, 2021. https://imputationserver.sph.umich.edu/index.html

- 19.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2011;9(2):179-181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559-575. doi: 10.1086/519795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner SD. qqman: An R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and Manhattan plots. bioRxiv. May 2014:005165. doi: 10.1101/005165 [DOI]

- 22.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(18):2336-2337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Zaitlen NA, Goddard ME, Visscher PM, Price AL. Advantages and pitfalls in the application of mixed-model association methods. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):100-106. doi: 10.1038/ng.2876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudbridge F, Gusnanto A. Estimation of significance thresholds for genomewide association scans. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32(3):227-234. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pe’er I, Yelensky R, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32(4):381-385. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duggal P, Gillanders EM, Holmes TN, Bailey-Wilson JE. Establishing an adjusted p-value threshold to control the family-wide type 1 error in genome wide association studies. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:516. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gene Expression Omnibus. Gene expression in acute appendicitis. Accessed June 14, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE9579

- 30.Chawla LS, Toma I, Davison D, et al. Acute appendicitis: transcript profiling of blood identifies promising biomarkers and potential underlying processes. BMC Med Genomics. 2016;9(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12920-016-0200-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gene Expression Omnibus. Acute appendicitis: transcript profiling of blood identifies promising biomarkers and potential underlying processes. Accessed June 14, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE83091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Gene Expression Omnibus. GEO2R. Accessed June 14, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/

- 33.Duffy DL, Martin NG, Mathews JD. Appendectomy in Australian twins. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;47(3):590-592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basta M, Morton NE, Mulvihill JJ, Radovanović Z, Radojicić C, Marinković D. Inheritance of acute appendicitis: familial aggregation and evidence of polygenic transmission. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46(2):377-382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oldmeadow C, Mengersen K, Martin N, Duffy DL. Heritability and linkage analysis of appendicitis utilizing age at onset. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12(2):150-157. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.2.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itani OA, Stokes JB, Thomas CP. Nedd4-2 isoforms differentially associate with ENaC and regulate its activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289(2):F334-F346. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00394.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang C, Kawabe H, Rotin D. The ubiquitin ligase Nedd4L Regulates the Na/K/2Cl co-transporter NKCC1/SLC12A2 in the colon. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(8):3137-3145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.770065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trimpert C, Wesche D, de Groot T, et al. NDFIP allows NEDD4/NEDD4L-induced AQP2 ubiquitination and degradation. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0183774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen H, Ross CA, Wang N, et al. NEDD4L on human chromosome 18q21 has multiple forms of transcripts and is a homologue of the mouse Nedd4-2 gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9(12):922-930. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snyder PM, Olson DR, McDonald FJ, Bucher DB. Multiple WW domains, but not the C2 domain, are required for inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel by human Nedd4. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(30):28321-28326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011487200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Itani OA, Campbell JR, Herrero J, Snyder PM, Thomas CP. Alternate promoters and variable splicing lead to hNedd4–2 isoforms with a C2 domain and varying number of WW domains. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285(5):F916-F929. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00203.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimura T, Kawabe H, Jiang C, et al. Deletion of the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4L in lung epithelia causes cystic fibrosis-like disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(8):3216-3221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010334108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eReferences.

eTable 1. Detailed Information on Individual Genotyping Batches

eTable 2. Characteristics of Subjects of European Descent

eTable 3. Results of Association Analysis for rs9953918 for Individual Batches

eTable 4. Frequency of rs9953918 in Various Populations

eTable 5. Expression of NEDD4L in Human Appendix

eTable 6. Results of Association Analysis for Top DEGs Between AA Patients and Controls

eTable 7. Differential Expression of NEDD4L in Appendiceal Tissue of Patients With AA and Controls

eTable 8. Top DEGs From Peripheral Blood RNA Between AA Patients and Controls

eFigure 1. Detailed Inclusion-Exclusion Information

eFigure 2. Plot for MDS (Multidiamensional Scaling) Demonstrating Restriction to European Ancestry

eFigure 3. Locus Plot of the Identified Region at 18q

eFigure 4. Manhattan Plot Region Showing the Region at Chromosome 18q to be Associated With Acute Appendicitis Among Subjects of European Ancestry

eFigure 5. QQ Plot for the Analysis Among Subjects of European Descent Demonstrating Uniform Distribution of Observed and Expected P Values

eFigure 6. Locus Plot for the Analysis Among Subjects of European Descent