Abstract

Direct methanol fuel cell technology implementation mainly depends on the development of non-platinum catalysts with good CO tolerance. Among the widely studied transition-metal catalysts, cobalt oxide with distinctively higher catalytic efficiency is highly desirable. Here, we have evolved a simple method of synthesizing cobalt tungsten oxide hydroxide hydrate nanowires with DNA (CTOOH/DNA) and without incorporating DNA (CTOOH) by microwave irradiation and subsequently employed them as electrocatalysts for methanol oxidation. Following this, we examined the influence of incorporating DNA into CTOOH by cyclic voltammetry, chronoamperometry, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. The enhanced electrochemical surface area of CTOOH offered readily available electroactive sites and resulted in a higher oxidation current at a lower onset potential for methanol oxidation. On the other hand, CTOOH/DNA exhibited improved CO tolerance and it was evident from the chronoamperometric studies. Herein, we noticed only a 2.5 and 1.8% drop at CTOOH- and CTOOH/DNA-modified electrodes, respectively, after 30 min. Overall, from the results, it was evident that the presence of DNA in CTOOH played an important role in the rapid removal of adsorbed intermediates and regenerated active catalyst centers possibly by creating high density surface defects around the nanochains than bare CTOOH.

Introduction

The growing energy demand has compelled interest in the design and development of innovative electrocatalysts for energy conversion and storage. The two important requirements for such an electrocatalyst are as follows: (i) it should be naturally abundant and (ii) affordable. In these lines, inexpensive transition metals have been investigated to replace noble metal-based materials that are expensive and scarce in order to render the technology economically viable.1 Direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs) are one of the foremost developed fuel cells and serve as low-temperature energy conversion devices operating via electrochemical principles.2−5 Therefore, DMFCs are appropriate for automobile and portable power applications.6,7 The methanol oxidation process proceeds via O–H bond cleavage, and a subsequent sequential dehydrogenation to formaldehyde and then to CO or CO2 has been widely explored as it plays a key role in determining DMFCs’ performance.8

In order to replace less abundant metals such as Pt, transition metals and their oxides have been widely studied.9 More specifically, transition-metal oxides such as NiO, Co3O4, and CuO were studied for the methanol oxidation reaction (MOR) owing to their high activities. Moreover, to increase the CO tolerance, bi-metallic catalysts such as Ni–Co oxides and their hydroxides were investigated to minimize the overpotential of the MOR.10,11 The advantages with wide oxidation states (such as +2, +3, and +4) for cobalt and its hydroxides were studied extensively due to their excellent electrocatalytic activity.12 Electrodeposited Co-W alloy (partially amorphous) was demonstrated to be a promising anodic catalyst for methanol oxidation in highly corrosive acidic and alkaline media.13 Co-W was found to be an excellent electrocatalyst with very high mechanical, tribological, magnetic, and anticorrosion properties for alkaline water electrolysis. In view of the considerably higher activity of tungsten-based alloy towards methanol oxidation, we intended to prepare CTOOH using deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

Methods such as hydrothermal treatment, microwave heating, wet-chemical, sol–gel method, and electrochemical depositions are well-known or the synthesis of cobalt-based nanomaterials including CoO, Co2O3, Co3O4, and Co(OH)2, respectively. Of these methods, microwave heating is a facile strategy to prepare uniform nanomaterials with minimal heat loss in a large scale. In other methods, the heat transfer steps involve transfer of heat from the mantle to the reactant through the reaction beaker containing a solvent; therefore, this is considered as an inefficient process for the synthesis of uniform morphological nanomaterials with high energy loss. In particular, the lack of proper nucleation is the major issue in conventional nanomaterial synthesis. Therefore, achieving uniform heat transfer via the collision of ions in the solution using microwave heating is considered as a facile approach.14,15 The microwave heating strategy is mainly used in organic reactions to achieve high selectivity and enhance the reaction rate. Thus, microwave heating for the synthesis of cobalt hydroxides is preferred. For example, Dhawale et al. developed Co(OH)2 nanorods by a fast microwave irradiation of the mixture containing urea, CTAB and Co(NO3)2·6H2O at 120 °C for 4 h and employed as an electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER).12 Co-W was found to be an excellent electrocatalyst with very high mechanical, tribological, and anticorrosion properties for alkaline water electrolysis. Considering the merits of transition metal-based catalysts and microwave heating, herein, CTOOH nanochains were prepared for MOR. So far, several strategies have been put forth by various researchers to design high-performance Pt and non-Pt-based electrocatalysts to improve methanol oxidation activity and CO tolerance that are very essential for DMFCs’ performance.16−20 Extensive research has been conducted to incorporate advanced supporting materials such as nanocarbons, conducting polymers, carbides, nitrides, and bimetals that can significantly minimize CO adsorption while resulting in a high catalyst utilization efficiency.21,22 Recently, a simple strategy was reported to design cobalt nanocrystal/nitrogen-doped carbon composite as an efficient and CO-resistant electrocatalyst.23

In order to appropriately tune the structural and morphological characteristics of CTOOH nanowires, DNA was incorporated during the synthesis. This resulted in the formation of CTOOH/DNA electrocatalyst. Recent studies on single-stranded DNA/reduced graphene oxide/Pt composite demonstrated superior electrocatalytic activity and antipoisoning ability that mainly originated from the functional groups present in DNA.24,25 Motivated by these works, we incorporated DNA to create high density surface defects by creating cracks around CTOOH catalysts that could possibly improve both electrochemical activity and CO tolerance for MOR.

Experimental Methods

Reagents and Instruments Used

Cobalt acetate (Co(Ac)2) (99.99%) and sodium tungstate (99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Herring Testes double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) with a base pair of around 50 k was also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) and used as received. Initially, the stock solutions of DNA was prepared by mixing (0.12 M) DNA powder in DI water and stirred for 12 h. The solid DNA powder was uniformly dispersed upon rigorous stirring over 12 h and resulted in a clear solution. Methanol (Qualigen) and sodium hydroxide (Qualigen) was used as received. XRD was performed at a scan rate of 1° min–1 with the 2θ range 10–90° using a Bruker X-ray powder diffractometer (XRD) that employed Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm). The morphological analysis of CTOOH samples were studied using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), (TecnaiTM G2TF20) working at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) was performed in a SUPRA 55VP Gemini Column (Carl Zeiss, Germany) with an air lock system. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a Tescan VEGA 3 SBH instrument with a BrukerEasy EDS attached setup.

General Procedure for Electrochemical Studies

Experiments were performed using a standard three-electrode electrochemical borosilicate glass cell. The catalyst-modified glassy carbon electrode was employed as a working electrode, a platinum wire as a counter electrode, and a saturated Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode. All the electrochemical studies were performed in 0.1 M NaOH.

Synthesis of Cobalt Tungsten Oxide Hydroxide Hydrate (CTOOH) (with and without DNA)

The synthesis was performed by simple microwave heating. Initially, DNA stock solution was prepared by dispersing 0.12 g of DNA powder in 100 mL DI water and stirred for 12 h to obtain a clear solution (Scheme 1). Typically, 0.1 M cobalt acetate was dissolved in 50 mL DI water and to this 25 mL of DNA stock (0.12 M) solution was added. Later, the solution was stirred for 30 min to ensure surface modification of CTOOH by DNA through electrostatic interactions between the cobalt ions and the aromatic moieties of DNA. Now, the beaker containing solution was subjected to microwave heating along with the dropwise addition of 50 mL (0.1 M) of sodium tungstate (Na2WO4·2H2O).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Cobalt Tungsten Oxide Hydroxide Hydrate (with DNA and without DNA).

For every 10 s, the above solution was taken out for the addition of Na2WO4·2H2O and stirred for a few minutes. Upon repeating this protocol, all the 50 mL of Na2WO4·2H2O was added to the cobalt acetate-containing DNA mixture. To complete the formation of cobalt tungsten oxide hydroxide hydrate DNA, it requires only 8 min of microwave heating and the initial pink color observed for the solution turned purple at the end of the reaction. Following the same procedure, cobalt tungsten oxide hydroxide hydrate was prepared in the absence of DNA intended for comparative study. Here, the same 8 min of microwave heating was carried out to form CTOOH (without DNA). After the sample formation, centrifugation was carried out with ethanol/water and dried overnight at 70 °C.

Interaction of CTOOH with DNA

DNA is a polymeric biomolecule that was found to be well suitable for nanomaterial synthesis toward various applications. In Watson and Crick’s model, the double helical structure of DNA have aromatic bases such as adenine (A), guanine (G), thymine (T), and cytosine (C) linked via hydrogen bonding.26 The side chains of this DNA ladder have sugar-phosphate backbones full of negative moieties. The first stage of DNA metallization is the activation stage such as interaction of the precursor with the negative moieties of DNA. The presence of such negative moieties facilitates electrostatic attraction of metal ions over the surface of DNA. As a result, a perfect chain-like nano-self-assembly of CTOOH is formed with more active sites. Recently, our group reported the advantages of DNA-based nanomaterials for an enhanced electrocatalytic water splitting reaction.27 The nanomaterials modified with DNA is highly stable in various environments such as acidic and alkaline conditions and sustainable for applications including electrocatalytic water splitting, sensors, and biomass conversions.28−31

Results and Discussion

The successful formation of cobalt tungsten oxide hydroxide hydrate (CTOOH) was confirmed using powder X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD). The stacked XRD pattern of the sample with DNA and the absence of DNA CTOOH perfectly matched with the reference JCPDS file no. 00-047-0142. The diffraction planes identified were (222), (330), (510), (530), and (642) corresponding to 23.8, 29.4, 35.5, 40.8, and 53.1°, respectively for CTOOH and CTOOH/DNA (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

XRD pattern for CTOOH with and without DNA modification.

The XRD pattern of the microwave-synthesized room-temperature samples confirmed the polycrystalline nature of CTOOH. Further, morphological analysis of the CTOOH samples was performed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM). Figure 2a shows the morphological outcome of the DNA-modified sample, where we can see the chain-like assembly of CTOOH. The perfect nanoflower assembly over the chains of DNA was clearly visible in the TEM images. The observed chain structure was further magnified with a high-resolution TEM image, as shown in Figure 2b,c. The selected area diffraction pattern (SAED) studied for CTOOH/DNA evidenced the polycrystalline nature of the sample and was in excellent agreement with XRD results (Figure 2d). Furthermore, the morphological outcome of the unmodified CTOOH was also studied using TEM. From Figure 3a, it was evident that the absence of DNA results in the formation of aggregated CTOOH. Such agglomeration in the absence of DNA was clearly noticed in the high-magnification images (Figure 3b,c). From SAED, the polycrystalline nature of CTOOH was confirmed (Figure 3d). Moreover, the surface morphology of both DNA-modified and unmodified CTOOH samples was confirmed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) (Figure 4). Results confirmed that the DNA-modified sample exhibits a perfect chain-like morphology (Figure 4a,) and in the absence of DNA, agglomeration of CTOOH was noticed, as shown in Figure 4c,d.

Figure 2.

(a) Low-magnification TEM images of CTOOH with DNA; (b, c) high-magnification TEM image of CTOOH with the DNA sample, and (d) SAED pattern of CTOOH with DNA

Figure 3.

(a) Low-magnification TEM images of CTOOH without DNA; (b, c) high-magnification TEM image of CTOOH without DNA, and (d) SAED pattern of CTOOH with DNA.

Figure 4.

(a, b) FE-SEM images of CTOOH with DNA and (c, d) CTOOH without DNA.

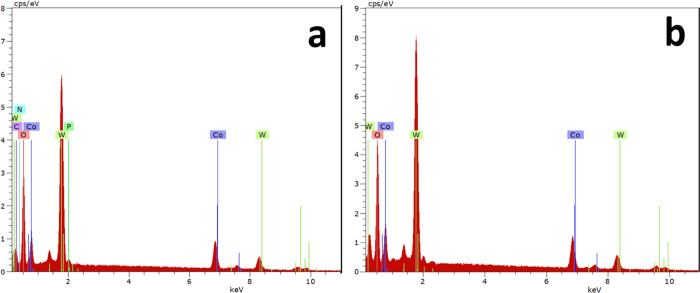

From FE-SEM images, the average chain diameter was calculated to be 110–120 nm for CTOOH/DNA. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopic analysis (EDS) was carried out to show the elemental presence and the purity of the sample (Figure 5). The sample modified with DNA (CTOOH/DNA) shows the elemental presence of Co, W, O, P, C, and N (Figure 5a). The presence of P, C, O, and N is from the aromatic base pairs and sugar moieties of DNA. The observed EDS spectrum for CTOOH/DNA confirms the strong interaction of CTOOH with DNA. Further, results confirmed that CTOOH without DNA contain only Co, W, and O (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

EDS analysis of CTOOH with (a) and without (b) DNA.

Electrocatalytic Methanol Oxidation Reaction

Electrocatalytic performance of the prepared catalysts was investigated by cyclic voltammetry, electrochemical impedance analysis, and chronoamperometry. Figure 6a,b is the comparative cyclic voltammetric profile of CTOOH and CTOOH/DNA in 1.0 M NaOH with the addition of 1.0 M methanol when the potential is swept from −0.6 to 1.0 V at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. Though bare and DNA-modified CTOOH exhibited a similar voltammetric feature, the current density and onset potential of the methanol oxidation reaction are different for CTOOH and CTOOH/DNA catalysts. Current density associated with methanol oxidation is higher for CTOOH than CTOOH/DNA. Further, the onset potential for the methanol oxidation is more negative for the CTOOH catalyst. A similar trend is observed with the catalysts previously studied for methanol electro-oxidation.

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms of (a) CTOOH and (b) CTOOH/DNA in 1.0 M NaOH with the addition of 1.0 M methanol (scan rate of 50 mV/s).

Methanol oxidation begins at 0.27 V at the CTOOH catalyst, but onset potential is shifted to 0.2 V when CTOOH/DNA was used as a catalyst. The readily available electroactive sites at CTOOH than CTOOH/DNA are responsible for the earlier onset for methanol oxidation. Table 1 reveals onset potential for methanol oxidation associated with a diverse range of catalysts studied under various electrolytes and scan rates. It could be noticed that methanol oxidation over the CTOOH/DNA surface was facile and comparable with previously reported data. Further, the forward peak potentials corresponding to methanol oxidation at CTOOH and CTOOH/DNA were found to be 0.37 and 0.39 V, respectively. From the results, it was evident that the presence of DNA hindered the redox-mediated oxidation of methanol due to the blockage of the hot spots at CTOOH responsible for methanol oxidation and therefore CTOOH exhibited a higher methanol oxidation activity.

Table 1. Comparison of the Onset Potential of the Developed Catalyst with Other Reports toward Methanol Oxidation.

| S. no. | catalyst studied | methanol/electrolyte | scan rate (mV/s) | Eon, onset potential for methanol oxidation (V) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nickel-cobalt oxides nanocomposites | 1.0 M methanol/1 M KOH | 50 | 0.386 | (32) |

| 2 | Co9S8@MoS2 nanohybrids | 0.5 M methanol/1.0 M KOH | 50 | 0.903 | (33) |

| 3 | Pt/CoPt/MWNT composite | 1.0 M methanol / 0.5 M H2SO4 | 50 | 0.29 | (34) |

| 4 | Pt – Co/Carbon nanocrystals | 1.0 M methanol/0.1 M HClO4 | 50 | 0.303 | (35) |

| 5 | jagged Pd/Co nanowires | 1.0 M methanol/1.0 M KOH | 50 | 0.343 | (36) |

| 6 | titanium cobalt nitride nanotubes | 1.0 M methanol + 0.5 M H2SO4 | 50 | 0.21 | (37) |

| 7 | core–shell polypyrrole/Co3O4 | 1.0 M methanol/1.0 M KOH | 50 | 0.28 | (38) |

| 8 | nickel–cobalt layered double hydroxide nanoarray | 0.5 M methanol/0.1 M NaOH | 50 | 0.49 | (16) |

| 9 | Ni–B nanoparticles doped with cobalt | 1.0 M methanol/1.0 M NaOH | 10 | 0.43 | (39) |

| 10 | hollow cobalt phosphide nanoparticles | 1.0 M methanol/1.0 M KOH | 5 | 0.29 | (40) |

| 11 | CoCr layered double hydroxide | 3.0 M methanol/1.0 M KOH | 60 | 0.37 | (41) |

| 12 | NiCoCr-layered double hydroxide | 3.0 M methanol/1.0 M KOH | 60 | 0.35 | (41) |

| 13 | three-dimensional (3D) platinum–cobalt alloy | 0.5 M methanol/0.5 M H2SO4 | 50 | 0.264 | (42) |

| 14 | Co/Cu-decorated carbon nanofibers | 2.0 M methanol/1.0 M KOH | 50 | 0.34 | (43) |

| 15 | cobalt tungsten oxide hydroxide hydrate nanochains/DNA | 1.0 M methanol/1.0 M NaOH | 50 | 0.21 | this work |

More importantly, the anodic peak potential corresponding to methanol oxidation associated with CTOOH/DNA is more positive than that of CTOOH, indicating facile electron transfer over CTOOH under low overpotential. However, the ratio of forward (Ifc) to backward (Ibc) peak current density, which is an approximate measure of the antipoisoning ability of the catalyst, is more for CTOOH/DNA, demonstrating its improved CO tolerance. Methanol oxidation results in the accumulation of CO over the catalyst surface. Moreover, the efficiency of the catalyst is determined by the rate of removal of adsorbed CO to regenerate active catalyst centers. It is well established that Ifc arises due to oxidation of methanol and Ibc is caused by the oxidation of surface-adsorbed intermediates (CO, CHxO, HCOO–, etc.).44 Since the (Ifc)/(Ibc) value for CTOOH/DNA is higher, we predict that the presence of DNA facilitates removal of surface poisoning species over the catalyst surface.

Catalytic efficiency can be predicated based on the rate of reaction and degree of CO tolerance. Therefore, based on our results it was evident that CTOOH/DNA was a suitable electrocatalyst for methanol oxidation. The enhanced CO tolerance observed with CTOOH/DNA stems from the weak chemisorption of COads. From these studies, it was evident that the incorporation of DNA increases the tolerance of the catalyst toward poisoning. EIS studies were performed at a 500 mV dc-offset potential in 0.1 M NaOH and 1.0 M methanol with CTOOH and CTOOH/DNA as the catalyst, as shown in Figure 7. Results indicated that the Nyquist plots remain unchanged, confirming that the mechanism of methanol oxidation was not affected by the nature of the catalyst. Upon fitting the EIS data with an appropriate equivalent circuit model comprising solution resistance (Rs), double layer capacitance (Cdl), and charge transfer resistance (Rct), the values of the quantitative parameters were calculated and tabulated in Table 2.

Figure 7.

EIS at a 500 mV dc-offset potential in 0.1 M NaOH upon the addition of 1.0 M methanol with CTOOH and CTOOH/DNA as catalysts.

Table 2. Quantitative Parameters Determined by Fitting the Experimental EIS Data.

| samples | electrolytic resistance Rs (Ohm/cm2) | double layer capacitance Cdl (F/cm2) | charge transfer resistance Rct (Ohm/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTOOH | 12.37 | 3.34 × 10–6 | 83.63 |

| CTOOH/DNA | 14.51 | 3.14 × 10–6 | 876 |

Steady-state current responses of CTOOH and CTOOH/DNA were examined to assess the long-term activity of the catalyst. Figure 8 is the representative chronoamperogram recorded at 0.4 V in 1.0 M NaOH in the presence of 0.1 M methanol (recorded for 2000s). Initially, a rapid current decay (up to 200 s) was witnessed due to double layer capacitance at both catalysts. A steady-state current response due to methanol oxidation is attained after 220 and 280 s with CTOOH and CTOOH/DNA electrodes, respectively, thereby demonstrating the better catalytic performance of the former. However, this faradaic current due to methanol oxidation was found to decline with time and after 1800 s, a drop of 2.5 and 1.8% in the current was noticed due to adsorption of accumulated carbon intermediates, particularly CO, at CTOOH than CTOOH/DNA. respectively. Resistance to CO adsorption as well as oxidation of this intermediate was facilitated by the presence of DNA. Such a resistance to CO adsorption can be attributed to the presence of phosphate and sugar backbones present in DNA. In addition, the wettable surface area was further enhanced due to DNA incorporation that improved the contact between electrode/electrolyte interfaces. A similar result was observed earlier when nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers/Co is investigated for methanol electro-oxidation under alkaline conditions.45 Therefore, increased accessibility of uninterrupted binding sites for C–H bond cleavage with enhanced accessible active catalytic sites for the removal of adsorbed CO with CTOOH/DNA is highly desirable.

Figure 8.

(a) Chronoamperogram of [i] the CTOOH catalyst in 1.0 M NaOH and [ii] the CTOOH catalyst in 1.0 M NaOH/0.1 M methanol. (b) Chronoamperogram of [i] the CTOOH/DNA catalyst in 1.0 M NaOH and [ii] the CTOOH/DNA catalyst in 1.0 M NaOH/0.1 M methanol performed at 0.4 V.

Conclusions

We successfully employed a microwave-assisted strategy to synthesize cobalt tungsten oxide hydroxide hydrate with and without DNA incorporation. Although CTOOH with readily available electroactive sites exhibits higher oxidation current and lower onset for methanol oxidation, DNA-modified CTOOH showed the advantage of inhibiting CO poisoning at higher rates. The presence of DNA facilitated the quick removal of adsorbed intermediates and regenerated the active catalyst centers.

Acknowledgments

S.M. is grateful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India, for providing funding under the scheme of “CSIR-SRA” (Ref: No. CSIR Award letter B-12496 dated 13.2.2019). S.A. and S.K. thank CIF, CSIR-CECRI for the support rendered during materials characterization.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

CSIR-CECRI Manuscript Communication Number: CECRI/PESVC/Pubs./2020-045.

References

- Antolini E.; Salgado J. R. C.; Gonzalez E. R. The Methanol Oxidation Reaction on Platinum Alloys with the First Row Transition Metals The Case of Pt–Co and −Ni Alloy Electrocatalysts for DMFCs: A Short Review. Appl Catal B Environ 2006, 63, 137–149. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanapriya S.; Rambabu G.; Suganthi S.; Bhat S. D.; Vasanthkumar V.; Anbarasu V.; Raj V. Bio-functionalized hybrid nanocomposite Membranes for Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. RSC Adv. 2016, 57709–57721. 10.1039/C6RA04098E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian M.; Suganthi S.; Raj V.; Baghavathy S.; Alwarappan S. Methodical Exploration on Silicotungstic Acid Tailored Hybrid Bio- Polymeric Proton-Exchange Membrane Electrolytes : Correlating Positron Annihilation Characteristics with Electrochemical Selectivity for Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 064511 10.1149/1945-7111/ab7bd9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz J.; Lefe M.; Dodelet J.; Kramm U. I.; Herrmann I.; Bogdanoff P.; Maruyama J.; Nagaoka T.; Garsuch A.; Dahn J. R.; Olson T.; Pylypenko S.; Atanassov P.; Ustinov E. A. Cross-Laboratory Experimental Study of Non-Noble-Metal Electrocatalysts for The oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2009, 167, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Huang L.; Zhang P.; Qiu Y.; Sheng T.; Zhou Z.; Wang G.; Liu J.; Rauf M.; Gu Z.; Wu W. T.; Sun S. G. Constructing a triple-phase interface in micropores to boost performance of Fe/N/C Catalysts for Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 645. 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanapriya S.; Bhat S. D.; Sahu A. K.; Pitchumani S.; Sridhar P.; Shukla A. K. A New Mixed-Matrix Membrane for DMFCs. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 1210–1216. 10.1039/b909451b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grindley T. B. Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 776–778. 10.1021/ja076948b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanapriya S.; Suganthi S.; Raj V. Mesoporous Pt – Ni Catalyst and Their Electro Catalytic Activity towards Methanol Oxidation. J. Porous Mater. 2017, 24, 355–365. 10.1007/s10934-016-0268-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan U. S.; Kueller R. F.; Moctezuma E. Methanol Oxidation over Nonprecious Transition Metal Oxide Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1990, 29, 1136–1142. 10.1021/ie00103a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z.-H.; Zhu Y.-J.; Cheng G.-F.; Huang Y.-H. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of β-Co(OH)2 and Co3O4 Nanosheets via a Layered Precursor Conversion Method. Can. J. Chem. 2006, 84, 1050–1053. 10.1139/v06-134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.; Xu Z. J. Composition Dependence of Methanol Oxidation Activity in Nickel-Cobalt Hydroxides and Oxides: An Optimization toward Highly Active Electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 165, 56–66. 10.1016/j.electacta.2015.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawale D. S.; Bodhankar P.; Sonawane N.; Sarawade P. B. Fast Microwave-Induced Synthesis of Solid Cobalt Hydroxide Nanorods and Their Thermal Conversion into Porous Cobalt Oxide Nanorods for efficient Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 1713–1719. 10.1039/C9SE00208A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vernickaite E.; Tsyntsaru N.; Cesiulis H. Electrodeposited Co-W Alloys and Their Prospects as Effective Anode for Methanol Oxidation in Acidic Media. Surf Coat Technol 2016, 307, 1322–1328. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.07.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbec J. A.; Magana D.; Washington A.; Strouse G. F. Microwave-Enhanced Reaction Rates for Nanoparticle Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15791–15800. 10.1021/ja052463g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahal N.; García S.; Zhou J.; Humphrey S. M. Beneficial Effects of Microwave-Assisted Heating versus Conventional Heating in Noble Metal Nanoparticle Synthesis. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 9433–9446. 10.1021/nn3038918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Wang Z.; Qizhou K.; Xia J.; Liu Q.; Wang Z. Highly Dispersed Ultrafine Pt Nanoparticles on Nickel-Cobalt Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoarray for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Methanol Oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 1–16310. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.07.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Wei Y.; Yang Y.; Yan M.; He H.; Jiang Q.; Yang X.; Zhu J. Controllable Synthesis of Grain Boundary-Enriched Pt Nanoworms Decorated on Graphitic Carbon Nanosheets for Ultrahigh Methanol. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 57, 601–609. 10.1016/j.jechem.2020.08.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.; Huang H.; He H.; Yang L.; Jiang Q.; Li W. Recent Advances in MXene-Based Nanoarchitectures as Electrode Materials for Future Energy Generation and Conversion Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 435, 213806. 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.213806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. S.; Hong Y.; Kim H. C.; Choi S.-I.; Hong J. W. Ultrathin-Polyaniline-Coated Pt-Ni Alloy Nanooctahedra for the Electrochemical Methanol Oxidation Reaction. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 7185–7190. 10.1002/chem.201900238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D.; Zeng C.; Xu C.; Cheng N.; Li H.; Mu S.; Pan M. Polyaniline-Functionalized Carbon Nanotube Supported Platinum Catalysts. Langmuir 2011, 27, 5582–5588. 10.1021/la2003589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K.-H.; Cheng C.-K.; Lin J.-Y.; Huang C.-H.; Yeh T.-K.; Hsieh C.-K. Highly-Porous Hierarchically Microstructure of Graphene-Decorated Nickel Foam Supported Two-Dimensional Quadrilateral Shapes of Cobalt Sulfide Nanosheets as efficient Electrode for Methanol Oxidation. Surf. Coat Technol. 2020, 393, 125850. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.125850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taha E.; Ali M.; Alawadhi H.; Salameh T. Facile and Low-Cost Synthesis Route for Graphene Deposition over Cobalt Dendrites for Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Applications. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 115, 321–330. 10.1016/j.jtice.2020.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari N.; Srirapu V. K. V. P.; Kumar A.; Singh R. N. Investigation of Mixed Molybdates of Cobalt and Nickel for Use as Electrode Materials in Alkaline Solution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 11040–11051. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Pan Y.; Guo X.; Liang Y.; Wu Y.; Wen Y.; Yang H. Pt/Single-Stranded DNA/Graphene Nanocomposite with Improved Catalytic Activity and CO Tolerance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 10353–10359. 10.1039/C5TA00891C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaravel S.; Karthick K.; Sankar S. S.; Karmakar A.; Madhu R.; Kundu S. Prospects in Interfaces of Biomolecule DNA and Nanomaterials as an Effective Way for Improvising Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering : A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 291, 102399. 10.1016/j.cis.2021.102399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Liu C.; Cao F.; Ren J.; Qu X. DNA Metallization: Principles, Methods, Structures, and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4017–4072. 10.1039/C8CS00011E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthick K.; Anantharaj S.; Ede S. R.; Sankar S. S.; Kumaravel S.; Karmakar A.; Kundu S. Developments in DNA Metallization Strategies for Water Splitting Electrocatalysis: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 282, 102205. 10.1016/j.cis.2020.102205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaravel S.; Thiruvengetam P.; Karthick K.; Sankar S. S.; Kundu S. Detection of Lignin Motifs with RuO2-DNA as an Active Catalyst via Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Studies. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 18463–18475. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b04414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaj S.; Jayachandran M.; Kundu S. Unprotected and Interconnected Ru0 Nano-Chain Networks: Advantages of Unprotected Surfaces in Catalysis and Electrocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 3188–3205. 10.1039/C5SC04714E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storhoff J. J.; Mirkin C. A. Programmed Materials Synthesis with DNA. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 1849–1862. 10.1021/cr970071p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilner O. I.; Willner I. Functionalized DNA Nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2528–2556. 10.1021/cr200104q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam P.; Ghanem M. A.; Al-mayouf A. M.; Al-shalwi M. Enhanced Electrocatalytic Performance of Mesoporous Nickel-Cobalt Oxide Electrode for Methanol Oxidation in Alkaline Solution. Mater. Lett. 2017, 196, 365–368. 10.1016/j.matlet.2017.03.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He L.; Huang S.; Liu Y.; Wang M.; Cui B.; Wu S.; Liu J.; Zhang Z.; Du M. Multicomponent Co9S8 @ MoS2 Nanohybrids as a Novel Trifunctional Electrocatalyst for Efficient Methanol Electrooxidation and Overall Water Splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 586, 538–550. 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.10.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Hu X.; Zhang J.; Su N.; Cheng J. Facile Fabrication of Platinum- Cobalt Alloy Nanoparticles with Enhanced Electrocatalytic Activity for a Methanol Oxidation Reaction. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9. 10.1038/srep45555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Yin L.; Yang T.; Huang Q.; He M.; Zhao H.; Zhang D.; Wang M.; Tong Z. One-Pot Synthesis of Concave Platinum – Cobalt Nanocrystals and Their Superior Catalytic Performances for Methanol Electrochemical Oxidation and Oxygen Electrochemical Reduction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 36164–36172. 10.1021/acsami.7b10209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Zheng L.; Chang R.; Du L.; Zhu C.; Geng D.; Yang D. Palladium – Cobalt Nanowires Decorated with Jagged Appearance for Efficient Methanol Electro-Oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 29965–29971. 10.1021/acsami.8b06851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Li W.; Pan Z.; Xu Y.; Liu G.; Hu G.; Wu S.; Li J.; Chen C.; Lin Y. Non-Carbon Titanium Cobalt Nitride Nanotubes Supported Platinum Catalyst with High Activity and Durability for Methanol Oxidation Reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 440, 193–201. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.01.151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalafallah D.; Alothman O. Y.; Fouad H.; Abdelrazek K. Hierarchical Co3O4 Decorated PPy Nanocasting Core- Shell Nanospheres as a High Performance Electrocatalysts for Methanol Oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 1–2753. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.12.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F.; Zhang Z.; Zhang F.; Duan D.; Li Y.; Liu S.; Yuan Q.; Wang E.; Hao X.; Zhang Z.; et al. Exploring the Role of Cobalt in Promoting the Electroactivity of Amorphous Ni-B Nanoparticles toward Methanol Oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 287, 115–123. 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.07.106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Liu Y.; Li J.; Amorim I.; Zhang B.; Xiong D.; Zhang N.; Thalluri S. M.; Sousa J. P. S.; Liu L. Hollow Cobalt Phosphide Octahedral Pre-Catalysts with Exceptionally High Intrinsic Catalytic Activity for Electro-Oxidation of Water and Methanol. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 20646–20652. 10.1039/C8TA07958G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamil S.; El Rouby W. M.; Antuch M.; Zedan I. T. Nanohybrid Layered Double Hydroxide Materials as Efficient Catalysts for Methanol Electrooxidation. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13503–13514. 10.1039/C9RA01270B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat N. A.; El-Newehy M.; Al-Deyab S. S.; Kim H. Y. Cobalt/Copper-Decorated Carbon Nanofibers as Novel Non-Precious Electrocatalyst for Methanol Electrooxidation. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 1–10. 10.1186/1556-276X-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Liu X.; Chen Y.; Zhou Y.; Lu T.; Tang Y. Platinum – Cobalt Alloy Networks for Methanol Oxidation Electrocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 23659–23667. 10.1039/c2jm35649j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrin P.; Mavrikakis M. Structure Sensitivity of Methanol Electrooxidation on Transition Metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14381–14389. 10.1021/ja904010u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamer B. M.; El-Newehy M. H.; Al-Deyab S. S.; Ali M.; Yong H.; Barakat N. A. M. Cobalt-Incorporated, Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanofibers as Effective Non-Precious Catalyst for Methanol Electrooxidation in Alkaline Medium. Appl. Catal., A 2015, 498, 230–240. 10.1016/j.apcata.2015.03.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]