Abstract

Objective

In Spring 2020, South Korea applied non-lockdown social distancing (avoiding mass gathering and non-essential social engagement, without restricting the movement of people who were not patients or contacts), testing-and-isolation (testing), and tracing-and-quarantine the contacts (contact tracing) to successfully control the first large-scale COVID-19 outbreak outside China. However, the relative contributions of these two interventions remain uncertain.

Methods

We constructed an SEIR model of SARS-CoV-2 transmission (disproportionately through superspreading events) and fit the model to outbreak data in Daegu, South Korea, from February to April 2020. We assessed the effect of non-lockdown social distancing (population-wide control measures) and/or testing-contact tracing (individual-specific control measures), alone or combined, in terms of the basic reproductive number (R0) and the trajectory of the epidemic.

Results

The point estimate for baseline R0 is 3.6 (sensitivity analyses range: 2.3 to 5.6). Combined interventions of non-lockdown social distancing and testing-contact tracing can suppress R0 to less than one and rapidly contain the epidemic, even under the worst scenario with a high baseline R0 of 5.6. In contrast, either intervention alone will fail to suppress R0. Non-lockdown social distancing alone just postpones the peak of the epidemic, while testing-contact tracing alone only flattens the curve but does not contain the outbreak.

Conclusions

To successfully control a large-scale COVID-19 outbreak, both non-lockdown social distancing and testing-contact tracing must be implemented. The two interventions are synergistic.

Introduction

By July 19, 2021, there were more than 188 million confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and 4 million deaths globally (World Health Organization 2021). Strict lockdown (confining people at home or shelter) has been widely enforced to limit the spread of its etiological agent, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Kraemer et al., 2020), but remains highly controversial due to the profound negative impacts on the society (The Great Barrington Declaration 2021). There is an urgent need for alternative strategies to control this pandemic.

On February 18, 2020, the authority detected a cluster of COVID-19 cases in Daegu, South Korea, which rapidly escalated to the first large-scale outbreak outside of China (Kim et al., 2020). Instead of lockdown, South Korea used non-lockdown social distancing (avoiding mass gathering and non-essential social engagement, without restricting the movement of people who are not patients or contacts) combined with quarantining infectious individuals through testing-and-isolation (testing) and tracing-and-quarantine the contacts (contact tracing) and controlled the outbreak rapidly within 4 weeks (Ryu et al., 2020, Korea Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2021, Park et al., 2020). However, non-lockdown social distancing yielded mixed results elsewhere (World Health Organization 2021), for which the causes remain unsettled.

We hypothesize that prompt quarantining of infectious persons is a prerequisite for the success of a less strict policy on social activities. This modeling study aimed to examine this hypothesis by assessing the effects of non-lockdown social distancing and testing-contact tracing, alone or combined, on the basic reproductive number (R0) of SARS-CoV-2 and the trajectory of the COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu, South Korea, February to April 2020.

This work was initiated, upon request, on February 25, 2020, to help South Korea to control the COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu. Preliminary results had been presented in special meetings with the Korean Mission in Taipei on February 25 and March 6, 2020, and the meeting report had been delivered to the South Korean government. This work had been presented as an oral abstract INT4622 at the International AIDS Society COVID-19 Conference: Prevention (Virtual) on February 2, 2021.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

This is a modeling study based on Korean Centers for Disease Control (KCDC) daily statistics without identifiable individual data, and therefore, does not require ethical review and approval.

SEIR Model

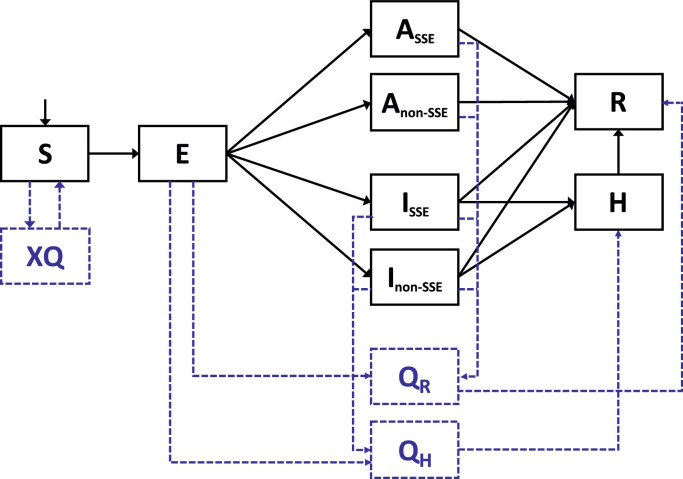

We constructed a dynamic model of SARS-CoV-2 transmission disproportionately through superspreading events (SSEs) (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005, 'Superspreader' in South Korea infects nearly 40 people with coronavirus, 2021) and fit the model to outbreak data in Daegu, South Korea, from February to April 2020. An earlier version of our model, specifically adapted to inform Taiwan's national policymaking, had been published (Chen and Fang, 2021). The SEIR model (Figure 1 ) includes key features in the natural history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, including an incubation period of 3.0 days (Lee et al., 2020), a presymptomatic infectious period of 2.5 days (He et al., 2020, Slifka and Gao, 2020, Wei et al., 2020), and an infectious duration of 8.5 days (up to 6.0 days after illness onset) (Cheng et al., 2020) (all values are mean duration). The model considers a very high heterogeneity in SARS-CoV-2 transmission (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005, 'Superspreader' in South Korea infects nearly 40 people with coronavirus, 2021, Lim et al., 2021), with 14.7% of infected individuals as superspreaders who caused 80% of new secondary infections (Lim et al., 2021). Infectious individuals, superspreaders or non-superspreaders, can be asymptomatic throughout the course (10%) (Chang, 2021, Wong et al., 2020, Arons et al., 2020). Infectiousness of asymptomatic infection is 30% lower than that of symptomatic infections (Chaw et al., 2020, Hu et al., 2021). Model parameters are listed in Table 1 . Model equations are available in Supplementary Material 1.

Figure 1.

Model structure

S: Susceptible; E: Latent (Infected but not yet infectious); ISSE: Infectious and symptomatic superspreaders; Inon-SSE: Infectious and symptomatic non-superspreaders; ASSE: Infectious but asymptomatic superspreaders; Anon-SSE: Infectious but asymptomatic non-superspreaders; H: Hospitalized due to severe/critical COVID-19; R: Recovered; XQ: Quarantine of uninfected contacts; QR: Isolation/quarantine of infected patients/contacts who either develop a mild illness or remain asymptomatic. QH: Isolation/quarantine of infected patients/contacts who develop severe/critical illnesses.

Table 1.

Model parameters

| Parameters | Value | Derivation and Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission probability per contact () | 0.0437 (Daegu, South Korea) | 1. The point estimates for baseline R0 and the transmission probability per contact (b) in Wuhan, China, were 3.6 and 0.04405, respectively, by fitting the model to the slope of the exponential phase, January 6 to January 22, 2020, Wuhan, China. (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2020).2. Based on a baseline R0 of 3.6 for the SARS-CoV-2 strain (imported from Wuhan, China) which initiated the Daegu outbreak, the point estimate for the transmission probability per contact (b) in Daegu, South Korea is 0.0437, by solving the Equation (1) (see Method section). |

| The proportion of superspreaders among infectious patients () | 14.7% | Based on South Korean data (Lim et al., 2021) |

| Contact rate in SSE group () | 54.4/day (mean) | Based on (1) an average contact rate of 10/day (Wallinga et al., 2006); and(2) a ratio of 23.13 (estimated by South Korean data: 14.7% superspreaders caused 80% secondary infections) (Lim et al., 2021) |

| Contact rate in the non-SSE group () | 2.4/day (mean) | Based on (1) an average contact rate of 10/day (Wallinga et al., 2006), and (2) a ratio of 23.13 (estimated by South Korean data: 14.7% of the superspreaders caused 80% of the secondary infections) (Lim et al., 2021) |

| The incubation period (from infection to the onset of illnesses) | 3.0 days (Daegu, South Korea) (mean) | The incubation period can be varied by the different settings and different periods of the COVID-19 pandemic (Xin et al., 2021)1. The point estimate for the incubation period in Wuhan, China, was 5.5 days (mean) (Lauer et al., 2020).2. The point estimate for the incubation period in Daegu, South Korea, was 3.0 days (median) (Lee et al., 2020) |

| Presymptomatic infectious period before the onset of illnesses | 2.5 days (mean) | (He et al., 2020, Slifka and Gao, 2020, Wei et al., 2020) |

| The latency period (infected but non-infectious) () | 0.5 days (Daegu, South Korea) (mean) | 1. The point estimate for the bvlatency period in Wuhan, China was 3.0 days, i.e.5.5 days (incubation period) (Lauer et al., 2020) minus 2.5 days (pre-symptomatic infectious period before the onset of illnesses) (He et al., 2020, Slifka and Gao, 2020, Wei et al., 2020) (the uncertainty range: 0–5 days)2. The point estimate for the latency period in Daegu, South Korea was 0.5 days, i.e., 3.0 days (incubation period) (Lee et al., 2020) minus 2.5 days (the presymptomatic infectious period before the onset of illnesses) (He et al., 2020, Slifka and Gao, 2020, Wei et al., 2020) |

| The infectious duration after the onset of illnesses | 6.0 days (mean)(uncertainty range: 4.6 to 9.1 days). | The point estimate is based on Taiwan contact-tracing data (Cheng et al., 2020) and is in line with Chinese clinical study data:4.6 days (onset to first medical visit (Li et al., 2020))to 9.1 days (onset to hospitalization (Li et al., 2020))(assume that patients were isolated after medical visits or hospitalization). |

| The infectious period () | 8.5 days (mean) (uncertainty range: 7.1 to 11.6 days, i.e., 4.6 to 9.1 days plus 2.5 days, respectively) | 2.5 infectious days before the onset of symptoms plus 6.0 infectious days after the onset of symptoms.We assume that asymptomatic infections have the same total infectious period. |

| Infection-related mortality among severe/critical cases () | 12% | (The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team, 2020) |

| The infection-related mortality rate in those who were hospitalized () | 0.0097 /day | Calculated by the formula (Keeling and Rohani, 2008)m = () |

| The natural-causes mortality rate () | 1/78.5 years | (The World Bank 2021) |

| The birth rate () | 1/78.5 years | We assume a stable population size (birth rate identical to natural-cause death rate). |

| The proportion of asymptomatic infection () | 10% | (Chang, 2021, Wong et al., 2020), (Arons et al., 2020) |

| The ratio of transmission probability of asymptomatic patients versus symptomatic patients () | 0.7 | (Chaw et al., 2020, Hu et al., 2021) |

| The proportion of severe/ critical cases () | 19% | (The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team, 2020) |

| Time from hospitalization to recovery among severe/critical patients () | 14 days (mean) | (Huang et al., 2020). |

| Time from onset of symptoms to laboratory confirmation | 5.3 days | For the Shincheonji religious group (Kim et al., 2020) |

| Time from the onset of infectiousness to quarantine () | 7.8 days (mean) | 5.3 days plus 2.5 days (the presymptomatic infectious period) before the onset of illnesses (He et al., 2020, Slifka and Gao, 2020, Wei et al., 2020) |

| The proportion of contact tracing () | 0% to 90% | Intervention scenarios |

| The duration of quarantine among mild cases () | 14 days | Intervention scenario, based on current standard practice |

| The duration from quarantine to hospitalization among severe/critical patients () | 3 days (mean) | 7 days (mean duration from the onset of symptom to the onset of severe disease (Huang et al., 2020)), minus 4 days (mean duration from the onset of symptom to diagnosis in the intervention scenario). |

| The fraction of the contact rate () rendered less effective under social distancing | 0% to 90% | Intervention scenarios |

| The proportion () of decrease in transmission probability per contact () under social distancing | 90% | (Chu et al., 2020) |

| The population size () | 30,000 (10,000 to 50,000) | The estimated number of Shincheonji Church members and their associates in Daegu, South Korea |

| Initial infectious population | 5 | Initial condition of simulation. |

Estimating the Baseline R0

Since the epidemic at Daegu, South Korea, was initiated by COVID-19 cases imported from Wuhan, China, we used publicly available epidemiological data from Wuhan to estimate the baseline (before intervention) R0 (the average number of secondary cases generated by an infectious individual in a non-immune, all susceptible population) of the SARS-CoV-2 strain in this outbreak. China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released the COVID-19 epidemic curve in Wuhan, by illness onset date, in an epidemic situation report on January 28, 2020 (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2020). An exponential growth of the COVID-19 epidemic occurred during the period from January 6, 2020, to January 22, 2020, with a linear R-square reaching 98% in regressing natural logarithm of numbers of incident cases (including both laboratory-confirmed and suspected cases, since numbers of the former were limited by diagnostic capacity) on the calendar date. We estimated the transmission probability per contact, b, in the following formula of baseline R0 (Keeling and Rohani, 2008), by fitting our model to the slope of exponential phase (January 6 to January 22, 2020) (Supplementary Material 2) with a numerical method:

| (1) |

Here, and : transmission probability per contact (with infected individuals who are symptomatic or asymptomatic, respectively); : proportion of infectious individuals who are asymptomatic; : proportion of superspreaders; and : contact rate of superspreaders and non-superspreaders, respectively; : average duration of latency period (infected but non-infectious state); : average duration of infectiousness; : natural-causes mortality rate. (see Table 1. for referenced details)

Simulating the Daegu Outbreak

We used the numbers of Shincheonji church members and their close contacts in Daegu, the predominantly affected group (Kim et al., 2020), to estimate the effective population size of this outbreak. We calibrated the onset date of the epidemic in the model to fit it to the cumulative curve of official statistics on confirmed COVID-19 cases in Daegu (Supplementary Material 2) (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021), taking into account the 10-day time lag from SARS-CoV-2 transmission to being listed in KCDC daily reports. This time lag comprises an incubation period (from transmission to onset of illness) of 3.0 days (Lauer et al., 2020), a patient delay (from illness onset to laboratory confirmation) of 5.3 days (Kim et al., 2020), and an administrative delay (from laboratory confirmation to being listed in the official statistics) of 2 days (all values are estimated mean duration).

Impact of Interventions

After validation of the model, we examined the effect of non-lockdown social distancing and testing-contact tracing, alone or combined, on R0 and trajectory of the COVID-19 epidemic:

Non-lockdown Social Distancing

Non-lockdown social distancing decreases transmission by rendering a fraction (50% to 75%) of the contact rate between susceptible and infectious individuals, or , less effective due to physical distancing between people. For this fraction , we assume that the probability of transmission per contact, , decreases by a proportion () of 90% (Chu et al., 2020). We model the overall effect of non-lockdown social distancing on the average probability of transmission by the following formula:

| (2) |

Testing-Contact Tracing

Testing-and-isolation detects and quarantines infectious individuals who are symptomatic by a rate of (Figure 1). Shincheonji religious group members in the Daegu outbreak took an average of 5.3 days from the onset of symptom to laboratory confirmation (Kim et al., 2020) before quarantine, equivalent to days (after adding the 2.5-day presymptomatic infectious period). Tracing contacts of detected infected individuals allows early quarantine of infected persons (Figure 1) by a proportion of ranging from 0% to 90%. The overall effect of test-contact tracing on R0 is given by the formula below: (Keeling and Rohani, 2008)

| (3) |

(R0 of supersupreaders under testing-contact tracing)

| (4) |

(R0 of non-superspreaders under testing-contact tracing)

Here, is the proportion of symptomatic infectious individuals whose diagnosis is delayed till hospitalization due to severe/critical COVID-19.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted two-way sensitivity analyses on the estimated baseline for R0 across uncertainty ranges of latency period and infectious period (Table 1 for details). We assess the impact of interventions on R0 and epidemic trajectory across different levels of social distancing or testing-contact tracing, alone or combined.

Results

The point estimate for baseline R0 is 3.6 (95% confidence interval: 3.4-3.9). The two-way sensitivity analyses (sensitivity analyses range: 2.3 to 5.6) show that the maximum estimate at the worst-case scenario is 5.6 when the latent period is five days and the infectious period is 11.6 days (Supplementary Figure 1).

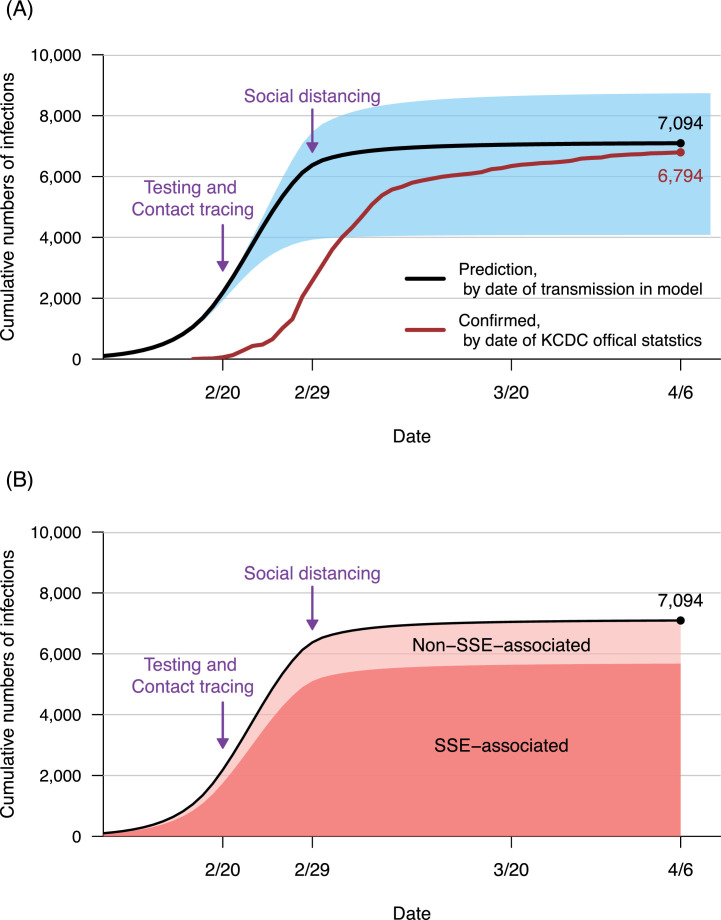

Figure 2 shows the validation of the model. Based on the point estimate for baseline R0 in the Wuhan outbreak, 3.6, and the number of Shincheonji members and their associates in Daegu, 30,000 (range: 10,000 to 50,000), the model predicts that cumulative numbers of all infected individuals (including those asymptomatic and undiagnosed) will reach 7,094 (range: 4,082 to 8,732) by April 6, 2020 (Figure 2, Panel A). The model-predicted curve parallels the actually observed curve, with a 10-day time lag from incubation period, laboratory confirmation, and statistic administration. The actual cumulative numbers of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases in KCDC statistics reached 6,794 by April 6, 2020 (red line), within the predicted range (blue shadow). The model simulation results affirm that an overwhelming majority (80%) of infections in this outbreak are associated with SSEs (Figure 2, Panel B).

Figure 2.

Simulating the Daegu outbreak

Simulations were conducted under a baseline primary reproductive number (R0) of 3.6 (point estimate, based on epidemiological data from Wuhan, China, January 6 to January 20, 2020).

Panel A: Black line shows predicted cumulative numbers of infections in Daegu (by date of transmission in the model) with testing (mean duration from illness onset to confirmation before quarantine: 5.3 days) and 50% contact tracing, started on February 20, 2020, as well as 50% non-lockdown social distancing, started on February 29, 2020 (purple arrows, respectively). To smooth the curve, testing-contact tracing and non-lockdown social distancing started from zero and gradually increased to the targeted level over a period of 10 days and 3 days, respectively. The population size of Shincheonji members and their close contacts in Daegu was assumed as 30,000. Blue shadow shows the sensitivity analysis on outbreak size by the uncertainty range of the Shincheonji population (range: 10,000 to 50,000). The Red line shows the number of cumulative confirmed cases by date from the Korean Center for Disease Control (KCDC) statistics.

Panel B: Dark red shadow shows the cumulative numbers of superspreading events (SSEs)-associated infection. Light red shadow shows cumulative numbers of infections that were not associated with SSEs.

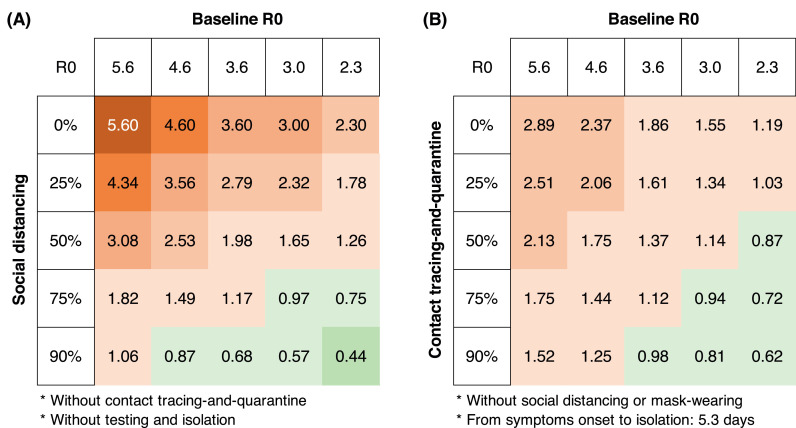

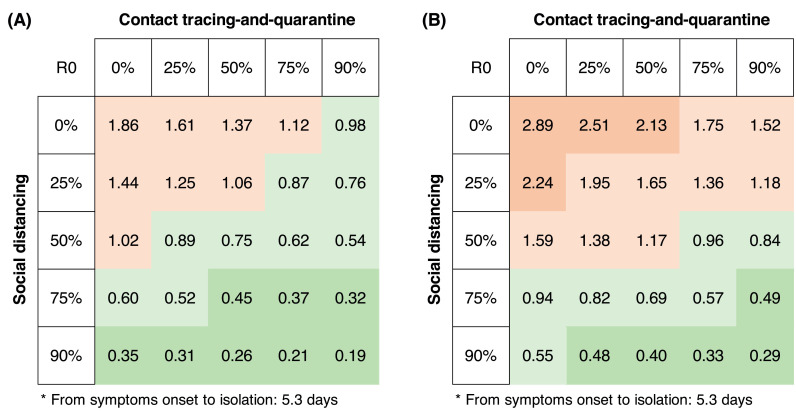

We examined the effect of the single intervention on R0. Either non-lockdown social distancing or testing-contact tracing decreases R0 (Figure 3). However, in the absence of testing-contact tracing, non-lockdown (50% to 75%) social distancing measures alone would not suppress R0 to less than 1 when baseline R0 is 3.6 (point estimate) or higher (Figure 3, Panel A). On the other hand, without social distancing measures, feasible testing-contact tracing (with a mean interval from illness onset to isolation of four days, and tracing 50% to 75% contacts) alone would also fail to suppress R0 to less than 1 when baseline R0 is 3.6 (point estimate) or higher (Figure 3, Panel B).

Figure 3.

Reproductive number (R0) under social distancing alone (A) or testing-contact tracing alone (B)

If the R0 is more than one (red color), then the disease will continue to spread. On the other hand, if the R0 is less than 1 (green color), the epidemic can be controlled.

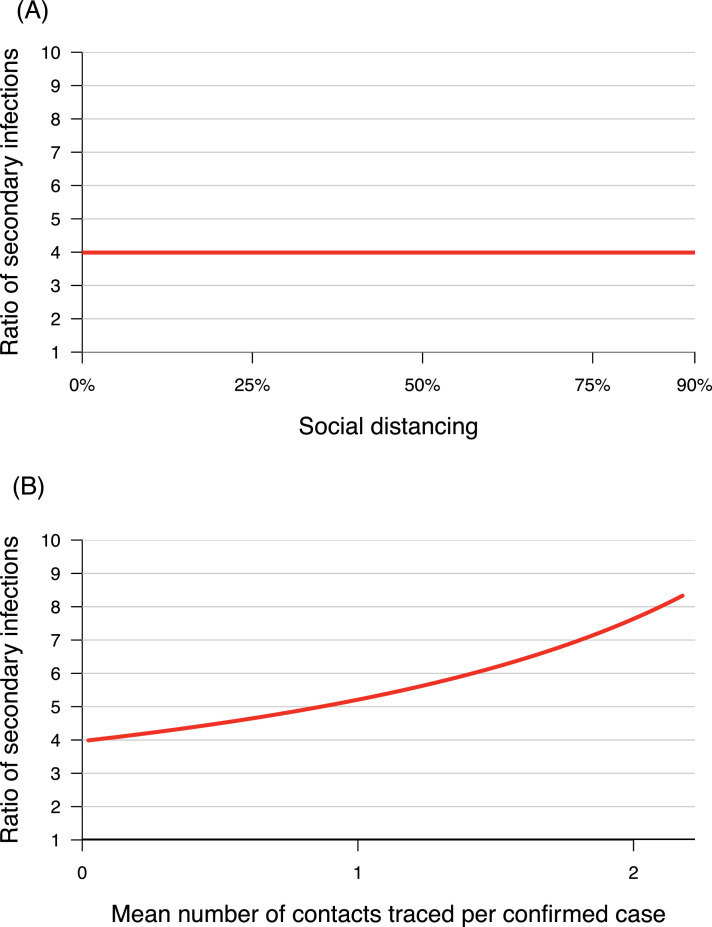

Consistent with the known pattern of epidemics spreading predominantly through SSEs (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005), our model indicates that non-lockdown social distancing (population-wide control measures) does not alter the ratio between the number of secondary infections from superspreaders and that from non-superspreaders (Figure 4, Panel A). This is in contrast to testing-contact tracing (individual-specific control measures), which sharply increases heterogeneity in infectiousness per individual between these two groups (Figure 4, Panel B), which favors epidemic control (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005).

Figure 4.

Heterogeneity in infectiousness per individual: (A) Effect of social distancing (population-wide interventions); (B) Effect of testing-contact tracing (individual-specific interventions)

Heterogeneity in infectiousness per individual is defined by the ratio between the numbers of secondary infections from superspreaders (ISSE and ASSE) and that from non-superspreaders (INon-SSE and ANon-SSE).

In contrast to single interventions, combined interventions with non-lockdown (50%) social distancing and test-contact tracing (50%) decrease the R0 to less than 1 when the baseline R0 is 3.6 (Figure 5, Panel A). Even under the worst scenario (a baseline R0 of 5.6), combined interventions with non-lockdown (75%), social distancing, and test-contact tracing (75%) still decrease the R0 to less than one (Figure 5, Panel B).

Figure 5.

Reproductive number (R0) under combined interventions

Panel A: Under a baseline R0 of 3.6, combined interventions with 50% non-lockdown social distancing and testing-contact tracing (50%) suppress the R0 to less than 1. Panel B: under a baseline R0 of 5.6, combined interventions with 75% non-lockdown social distancing and testing-contact tracing (75%) suppress the R0 to less than 1.

Targeting non-lockdown (50% to 75%) social distancing to superspreaders alone, without any restrictive public health measures on non-superspreaders, does not alter the effectiveness of combined interventions in suppressing R0 to below one (Supplementary Figure 2).

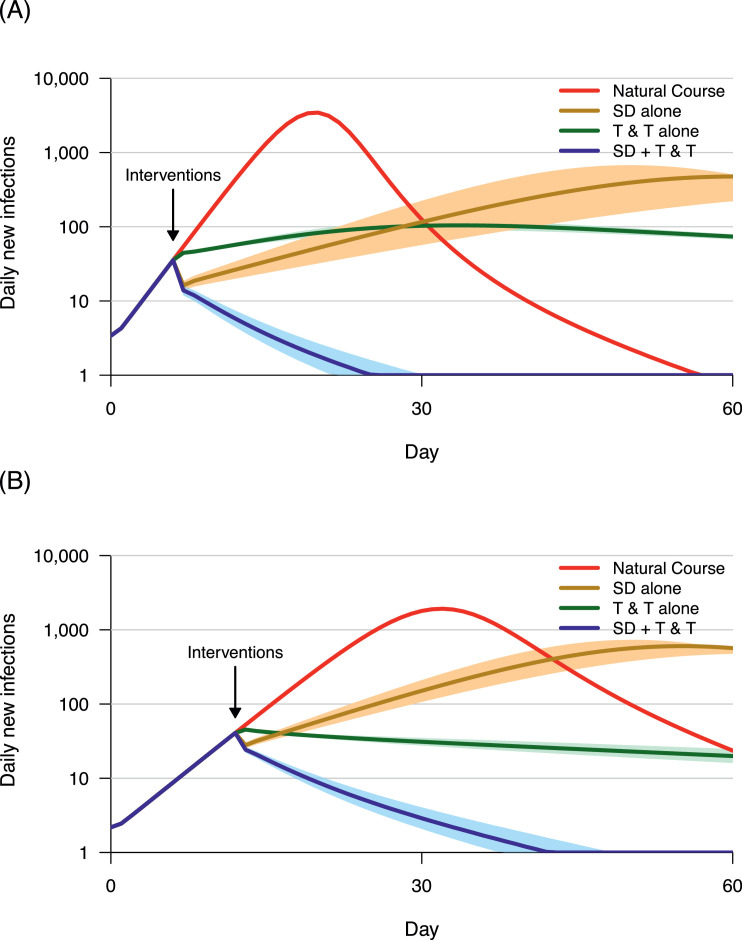

Figure 6 further shows the effects of interventions on the epidemic trajectory. Under a baseline R0 of 3.6 (Figure 6, Panel A) or 5.6 (Figure 6, Panel B), non-lockdown social distancing (50% or 75%) alone just postpones the peak of the epidemic (brown lines), while testing-contact tracing (50% or 75%) alone only flattens the curve but does not contain the outbreak (green lines). In contrast, combined interventions effectively suppress the incidence of new COVID-19 infections to zero (blue lines).

Figure 6.

Trajectories of COVID-19 epidemic under different scenarios

Red line: natural course of the epidemic, without interventions. Brown line: non-lockdown social distancing (SD) alone. Green line: testing (with a mean time of 5.3 days from illness onset to confirmation) and contact-tracing (T & T) alone. Blue line: Combined intervention (SD + T & T). All interventions were started when the number of new infections reaches 50 per day (marked by black arrow) in a 30,000 population. The color shadows show sensitivity analyses, ranging from -5% to +5% of the interventions. Panel A: Under a baseline R0 of 3.6, effects of SD 50% alone (brown line), T & T 50% alone (green line), and SD 50% + T &T 50% (blue line). Panel B: Under a baseline R0 of 5.6, effects of SD 75% alone (brown line), T & T 75% alone (green line), and SD 75% + T &T 75% (blue line).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that the presence of testing-contact tracing is required to ensure the success of non-lockdown social distancing (not restricting the movement of people who are not patients or contacts) to control a large-scale COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu, South Korea, 2020, in term of R0 and epidemic trajectory. Both interventions are necessary for the successful containment of a large-scale COVID-19 outbreak.

Previous studies showed that non-pharmacological interventions (testing-contact tracing and social distancing) effectively reduced SARS-CoV-2 transmission in South Korea (Ryu et al., 2020, Park et al., 2020, Park et al., 2020), but it is difficult for empirical studies to separately measure the respective effects of these two almost simultaneously implemented interventions. Using a mathematical modeling approach to examine hypothetical scenarios, our study provided new insight on the necessary conditions for effective SARS-CoV-2 epidemic control.

SARS-CoV-2 spreads predominantly through SSEs, in which a small number of infectious individuals are associated with the vast majority of secondary infections (Lim et al., 2021, Adam et al., 2020, Miller et al., 2020, Bi et al., 2020, Endo et al., 2020, Hamner et al., 2020). This suggests that early quarantine of a few superspreaders may yield an out-of-proportion effect to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005, Althouse et al., 2020, Superspreading drives the COVID pandemic — and could help to tame it 2021). Althouse et al. suggested that eliminate SSEs through extensive testing, and contact tracing might make it possible to contain the epidemic without strict lockdown (Althouse et al., 2020). Based on the empirical data from the Daegu outbreak in 2020, the present work is the first study to demonstrate that testing-contact tracing does have an essential role in South Korea's successful control of a large-scale COVID-19 outbreak using a non-lockdown approach.

An important unsettled question is whether targeting the control effort in "problem places," where SSEs occur, can suppress SARS-CoV-2 transmission to allow the lifting of restrictive public health measures such as physical distancing and mask mandate elsewhere (Althouse et al., 2020, Superspreading drives the COVID pandemic — and could help to tame it 2021). Our modeling results show that, theoretically, this “target control” approach is indeed capable of suppressing R0 to less than 1 when simultaneously implemented with testing-contact tracing (50% to 75%) (Supplementary Figure 2). Nevertheless, practically, it might be challenging to preemptively identify all such places before SSEs occur.

Previous modeling studies show that, when superspreading is the predominant transmission pattern, individual-specific control measures (testing-contact tracing) outperform population-wide control measures (social distancing) (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005). In keeping with this general rule, the present modeling work in analyzing the Daegu outbreak shows that testing-contact tracing alone will outperform social distancing alone in suppressing the R0 of SARTS-CoV-2 (Figure 5) and controlling the COVID-19 outbreak (Figure 6). However, delay in laboratory confirmation is the Achilles' heel of SARS-CoV-2 testing (Althouse et al., 2020, Superspreading drives the COVID pandemic — and could help to tame it 2021, Park et al., 2020). Studies showed that it took up to 3 days (average) from symptom onset to quarantine in Seoul, Korea (Park et al., 2020) because initial symptoms are often non-specific (Huang et al., 2020). For less cooperative Shincheonji religious group members who avoided epidemiological investigation, there was an even longer delay (5.3 days) between illness onset and laboratory confirmation (Kim et al., 2020). Furthermore, transmission frequently occurs before the onset of illness (He et al., 2020, Slifka and Gao, 2020, Wei et al., 2020, Chang, 2021, Wong et al., 2020, Chaw et al., 2020, Hu et al., 2021). Therefore, population-wide control measures (social distancing or mask), which universally decrease transmission probability for all individuals, including undetected superspreaders, are essential for combined interventions to successfully control a COVID-19 outbreak.

We did not consider a separate category for imported cases in outbreak scenarios to avoid unnecessary model complexity. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency official statistics showed that, by April 6, 2020, only 12 (0.18%) of the 6,794 COVID-19 cases diagnosed in Daegu were imported cases. While the local outbreak was initiated by imported cases (Kim et al., 2020, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021, Ki, 2020), the number of imported cases becomes negligible soon after a dramatic increase in locally acquired cases.

In non-outbreak scenarios, however, imported cases carry the risk of initiating new outbreaks. Even though testing-contact tracing and social distancing can keep local transmission levels from escalating to large-scale outbreaks, burdens on medical/public health systems will soon exceed the capacity limit in the absence of strict border control (Chen and Fang, 2021). Our previous modeling work showed that, when the number of escaped imported cases (not detected and quarantined at entry, due to false-negative testing results, and not adhered to 14-days quarantine after entry) increases from one to ten per day, the 90-day cumulative number needed to hospitalize and quarantine will jump from 349 and 4,092 to 3,483 and 40,810, respectively (Chen and Fang, 2021). Once medical and public health systems are overburdened and collapsing, testing-contact tracing will not be timely performed, with the risk of losing epidemic control. Therefore, strict restriction of travel from high-risk areas is needed to prevent new outbreaks.

Our finding has an important implication––adopting a non-lockdown approach to control a large-scale COVID-19 outbreak is feasible but needs to be accompanied by a robust testing-contact tracing mechanism to promptly identify and break chains of transmission. The lack of effective contact tracing thus may explain the unprecedented massive surge of COVID-19 epidemic in Europe after lifting lockdown in 2020 autumn/winter (World Health Organization 2021).

Allowing people to freely go outside to receive testing and care, non-lockdown social distancing facilitates early detection/isolation of infected persons and subsequent contact tracing, ensuring the feasibility of a non-lockdown social policy to control an outbreak. Therefore, non-lockdown social distancing and testing-contact tracing not only have an epidemiological synergism in breaking the chains of SARS-CoV-2 transmission but also reinforce each other in practical implementation.

The successful control of the COVID-19 outbreak at Daegu, South Korea, is a public health triumph. This success highlights that a democratic and humane strategy to contain a highly contagious disease is feasible and highly effective.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (Taipei, Taiwan) (MOHW-109-CDC-ZH108028, MOHW-110-CDC-ZH109031). The publication fee was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and National Taiwan University Infectious Diseases Research and Education Center (Taipei, Taiwan). Funders have no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have an association that might pose a conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

YHC and CTF designed the study; YHC searched the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency website for publicly available epidemiological data on the Daegu outbreak and conducted infectious diseases modeling; YLH communicated with Korean Mission in Taipei; YHC and CTF wrote the manuscript; CTF and YHC contributed equally.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.058.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Adam DC, Wu P, Wong JY, Lau EHY, Tsang TK, Cauchemez S, et al. Clustering and superspreading potential of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Hong Kong. Nat Med. 2020;26(11):1714–1719. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althouse BM, Wenger EA, Miller JC, Scarpino SV, Allard A, Hébert-Dufresne L, et al. Superspreading events in the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2: Opportunities for interventions and control. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, Kimball A, James A, Jacobs JR, et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(22):2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, Ye C, Zou X, Zhang Z, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(8):911–919. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SC. Proportion of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections among 398 laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2-infected patients in Taiwan [in traditional Chinese]. Available from: https://news.ltn.com.tw/news/life/breakingnews/3137967. Accessed on: 2020-04-18 2021.

- Chaw L, Koh WC, Jamaludin SA, Naing L, Alikhan MF, Wong J. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in different settings. Brunei. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(11):2598–2606. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.202263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Fang CT. Combined interventions to suppress R0 and border quarantine to contain COVID-19 in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120(2):903–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HY, Jian SW, Liu DP, Ng TC, Huang WT, Lin HH. Contact tracing assessment of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in Taiwan and risk at different exposure periods before and after symptom onset. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemic update and risk assessment of 2019 Novel Coronavirus. 2020.

- Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo A, Abbott S, Kucharski AJ, Funk S. Estimating the overdispersion in COVID-19 transmission using outbreak sizes outside China. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:67. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamner L, Dubbel P, Capron I, Ross A, Jordan A, Lee J, et al. High SARS-CoV-2 attack rate following exposure at a choir practice - Skagit County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):606–610. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Wang W, Wang Y, Litvinova M, Luo K, Ren L, et al. Infectivity, susceptibility, and risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 transmission under intensive contact tracing in Hunan, China. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1533. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21710-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling MJ, Rohani P. Princeton University Press; 2008. Modeling Infectious Diseases in Humans and Animals. [Google Scholar]

- Ki M. Epidemiologic characteristics of early cases with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) disease in Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2020;42 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Hwang HS, Choi YH, Song HY, Park JS, Yun CY, et al. The delay in confirming COVID-19 cases linked to a religious group in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020;53(3):164–167. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Jeong YD, Byun JH, Cho G, Park A, Jung JH, et al. Evaluation of COVID-19 epidemic outbreak caused by temporal contact-increase in South Korea. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Press Release. Available from: https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a30402000000&bid=0030. 2021

- Korea Ministry of Foreign Affairs. COVID-19 in Korea: An Update. Available from: http://overseas.mofa.go.kr/nl-en/brd/m_6988/view.do?seq=759032&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&multi_itm_seq=0&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&company_cd=&company_nm=. 2021

- Kraemer MUG, Yang CH, Gutierrez B, Wu CH, Klein B, Pigott DM, et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6490):493–497. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, Meredith HR, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Kim K, Choi K, Hong S, Son H, Ryu S. Incubation period of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Busan, South Korea. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26(9):1011–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J-S, Noh E, Shim E, Ryu S. Open Forum Infectious Diseases; 2021. Temporal changes in the risk of superspreading events of coronavirus disease 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, Getz WM. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature. 2005;438(7066):355–359. doi: 10.1038/nature04153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Martin MA, Harel N, Tirosh O, Kustin T, Meir M, et al. Full genome viral sequences inform patterns of SARS-CoV-2 spread into and within Israel. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5518. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19248-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SW, Sun K, Viboud C, Grenfell BT, Dushoff J. Potential role of social distancing in mitigating spread of coronavirus disease. South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(11):2697–2700. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.201099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Huh IS, Lee J, Kang CR, Cho SI, Ham HJ, et al. application of testing-tracing-treatment strategy in response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Seoul. Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(45):e396. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Choe YJ, Park O, Park SY, Kim YM, Kim J, et al. contact Tracing during Coronavirus Disease Outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10):2465–2468. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S, Ali ST, Jang C, Kim B, Cowling BJ. Effect of nonpharmaceutical interventions on transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10):2406–2410. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifka MK, Gao L. Is presymptomatic spread a major contributor to COVID-19 transmission? Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1531–1533. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 'Superspreader' in South Korea infects nearly 40 people with coronavirus. Available from: https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-superspreader-south-korea-church.html. 2021

- Superspreading drives the COVID pandemic — and could help to tame it. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00460-x. 2021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- The Great Barrington Declaration. The Great Barrington Declaration.; 2021. Contract No.: 2021-03-02.

- The World Bank. Life expectancy at birth - United States. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=US. 2021

- The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) China CDC Weekly. 2020;2:113–122. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2020.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallinga J, Teunis P, Kretzschmar M. Using data on social contacts to estimate age-specific transmission parameters for respiratory-spread infectious agents. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(10):936–944. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei WE, Li Z, Chiew CJ, Yong SE, Toh MP, Lee VJ. Presymptomatic Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 - Singapore, January 23-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):411–415. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J, Abdul Aziz ABZ, Chaw L, Mahamud A, Griffith MM, Lo Y-R, et al. High proportion of asymptomatic and presymptomatic COVID-19 infections in air passengers to Brunei. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2020;27(5) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed on: July 19, 2021.

- Xin H, Wong JY, Murphy C, Yeung A, Ali ST, Wu P, et al. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America; 2021. The incubation period distribution of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.