Abstract

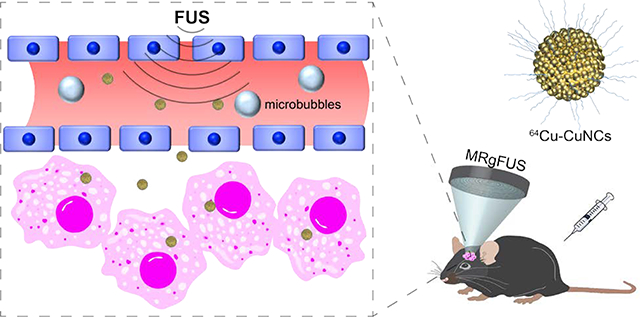

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is an invasive pediatric brainstem malignancy exclusively in children without effective treatment due to the often-intact blood-brain tumor barrier (BBTB), an impediment to the delivery of therapeutics. Herein, we used focused ultrasound (FUS) to transiently open BBTB and delivered radiolabeled nanoclusters (64Cu-CuNCs) to tumors for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and quantification in a mouse DIPG model. First, we optimized FUS acoustic pressure to open the blood-brain barrier (BBB) for effective delivery of 64Cu-CuNCs to pons in wildtype mice. Then the optimized FUS pressure was used to deliver radiolabeled agents in DIPG mouse. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided FUS-induced BBTB opening was demonstrated using a low molecular weight, short-lived 68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i radiotracer and PET/CT before and after treatment. We then compared the delivery efficiency of 64Cu-CuNCs to DIPG tumor with and without FUS treatment and demonstrated the FUS-enhanced delivery and time-dependent diffusion of 64Cu-CuNCs within the tumor.

Keywords: diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, positron emission tomography, focused ultrasound, nanoclusters, magnetic resonance imaging

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) arises in the pons and is a leading cause of pediatric brain tumor death. At diagnosis, the majority of patients are between 5 and 10 years old and have a median survival of less than 1 year.1–2 Resection is not an option because of the diffuse nature of the tumor and the critical function of the pons. Focal radiation is the standard of care treatment for children with DIPG, and the addition of chemotherapeutic agents or small molecule inhibitors has failed to show an improvement in survival over radiation alone in numerous clinical trials conducted over the past several decades.3–4 This may be due to ineffective drug delivery to DIPG, which often has an intact blood-brain tumor barrier (BBTB), and other potential obstacles, such as the restricted diffusion of drugs through the brain parenchyma.5 Many methods have been developed to overcome the obstacles presented by the BBTB and increase drug penetration, such as intra-arterial administration of osmotic agents enabling temporary disruption of BBTB,6 convection-enhanced delivery that interstitially infuses drugs under a constant pressure gradient,7 and laser interstitial thermotherapy that allows laser ablation of a tumor via insertion of an optical fiber.8 These techniques either lead to BBTB disruption in the whole brain, or are detrimentally invasive. The combination of focused ultrasound (FUS) and microbubbles (MBs), which enhances the BBTB permeability, has drawn great attention due to its non-invasive and localized delivery abilities and minimal neuronal damage.9 FUS non-invasively penetrates the skull and focuses energy on a small region of millimeter-scale dimensions. MBs, which have been used in the clinic as ultrasound contrast agents for imaging, are administered by intravenous (IV) injection. Following injection, their relatively large size (1–10 μm) confines them to the vasculature instead of naturally penetrating the BBTB. MBs amplify and localize FUS-mediated mechanical effects on the vasculature through FUS-induced cavitation (microbubble expansion, contraction, and collapse), which generates mechanical forces on the vasculature and transiently increases the BBTB permeability. To better localize the FUS treatment, magnetic resonance imaging-guided FUS (MRgFUS) treatment enables precise targeting and treatment planning, and allows targeted delivery of various therapeutics without damaging surrounding healthy structures.10–13 This integrated technology has progressed rapidly and led to numerous ongoing clinical trials in brain cancer patients due to the feasibility and safety of FUS.9, 14–17

Nanostructures have been widely used for cancer research due to the versatile physicochemical properties and multifunctionality for diagnosis, drug delivery and treatment.18–20 Through the combination with FUS to break BBTB, a variety of nanostructures have been used for brain tumor imaging and treatment with proven advantages in terms of local targeting and multifunctional theranostics.21–24 However, there are no applications in DIPG. Previously, we reported the trans-blood brain barrier (BBB) delivery of an ultrasmall gold nanocluster (64Cu-AuNCs) to the pons of wildtype mice following FUS treatment,25–27 which paved a path for imaging and treatment of DIPG. Herein, we first optimized the acoustic pressure for effective and safe BBB opening. Following MRgFUS, we precisely targeted DIPG tumor in pons at early stage and validated the BBTB opening using positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). Using an ultrasmall and biodegradable copper nanocluster intrinsically radiolabeled with 64Cu (64Cu-CuNC) as a model-drug,28 we studied the tumor delivery efficiency, intratumoral diffusion and retention in a mouse DIPG tumor model and laid the foundation for potential early diagnosis and treatment of DIPG (Figure S1).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

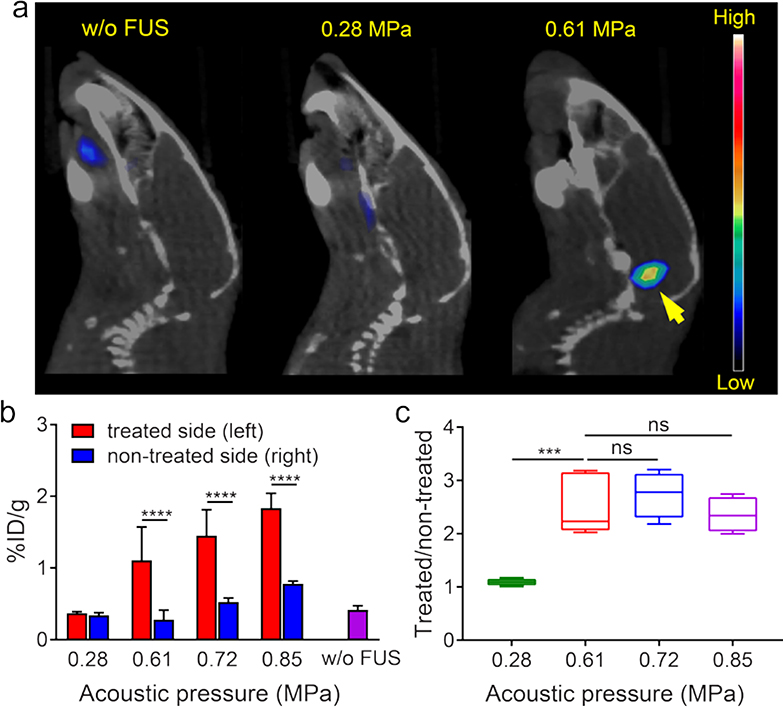

The effective trans-BBTB delivery of nanoclusters is mainly affected by both physicochemical properties of nanoclusters and FUS parameters for BBTB opening. Based on our previous report and optimized procedures,25,28 we synthesized 64Cu-CuNCs with ultrasmall hydrodynamic sizes (5.6 ± 1.5 nm) and neutral charge (zeta potential= −0.04 ± 0.12 mV) for effective renal clearance and optimal biodistribution (Figure S2 and Table S1). In vivo pharmacokinetic evaluation of 64Cu-CuNCs showed rapid systemic clearance with little retention in any major organs at 48 h post injection.28 Furthermore, cytotoxicity assay in U87 cells showed that the IC50 values for CuNC and Cu2+ were 18.6 μg/mL and 5.1 μg/mL, respectively, indicating the advantage of nanostructure relative to Cu2+ cation alone. We next studied the effect of varying FUS acoustic pressures on BBB opening by PET imaging of 64Cu-CuNCs in wildtype mice. Based on our previous report,29 we targeted FUS on the left pons of C57BL/6 mice (n = 4 – 5) with FUS pressures of 0.28, 0.61, 0.72 and 0.85 MPa prior to intravenous injection of 64Cu-CuNCs. PET/CT images demonstrated clear radioactive signals at the left pons for 0.61, 0.72 and 0.85 MPa at 24 h post-injection, while there was negligible uptake of 64Cu-CuNCs at pons treated with 0.28 MPa FUS pressure (Figure 1 and S3). Quantitative analysis at 24 h in mice treated with 0.28 MPa FUS pressure showed 64Cu-CuNCs uptake of 0.37 ± 0.02 percent injection dose per gram (%ID/g) (n = 4) at the treated left pons and 0.34 ± 0.04 %ID/g at the non-treated right pons, while the background blood retention in the pons of mice without FUS treatment was 0.42 ± 0.06 %ID/g (n = 4), demonstrating the ineffectiveness of BBB opening under 0.28 MPa FUS treatment. However, mice treated with 0.61, 0.72 and 0.85 MPa FUS showed significantly increased pons uptakes of 1.11 ± 0.46%ID/g (n = 5, P<0.01), 1.45 ± 0.36 (n = 4, P<0.0001), and 1.84 ± 0.21 %ID/g (n = 4, P<0.0001), respectively, at the treated left pons. Interestingly, we also observed increased 64Cu-CuNCs uptake at the non-treated right pons in mice treated with 0.72 MPa and 0.85 MPa pressures, suggesting a higher level of BBB disruption by elevated FUS pressure, which was consistent with our previous report (Figure 1b).26 However, there was no significant difference in the treated/non-treated uptake ratios for the three FUS pressure settings (0.61, 0.72 and 0.85 MPa) (Figure 1c), indicating the effectiveness of these three FUS pressures to open BBB for contrast imaging. Moreover, histopathological examination showed no damage to brain tissue at 0.61 and 0.72 MPa but some hemorrhage at 0.85 MPa pressure (Figure S4). Therefore, to minimize safety concerns while still obtaining sufficient delivery efficiency, we opted to use 0.61 MPa FUS pressure as optimal for DIPG tumor imaging in this study. In addition, our previous studies have verified that 0.61 MPa FUS pressure resulted in no tissue damage in the brain.25–27

Figure 1.

(a) In vivo PET/CT images of 64Cu-CuNCs without FUS treatment and under 0.28 and 0.61 MPa FUS pressure in WT mice at 24 h post IV injection. (b) Quantitative analysis of 64Cu-CuNCs uptake in FUS treated left pons and non-treated right pons of WT mice under 0.28, 0.61, 0.72, and 0.85 MPa FUS pressures and the pons without FUS treatment in WT mice. (c) the uptake ratios of treated sites vs non-treated sites of the FUS treated mice under different pressures (*** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, n = 4–5).

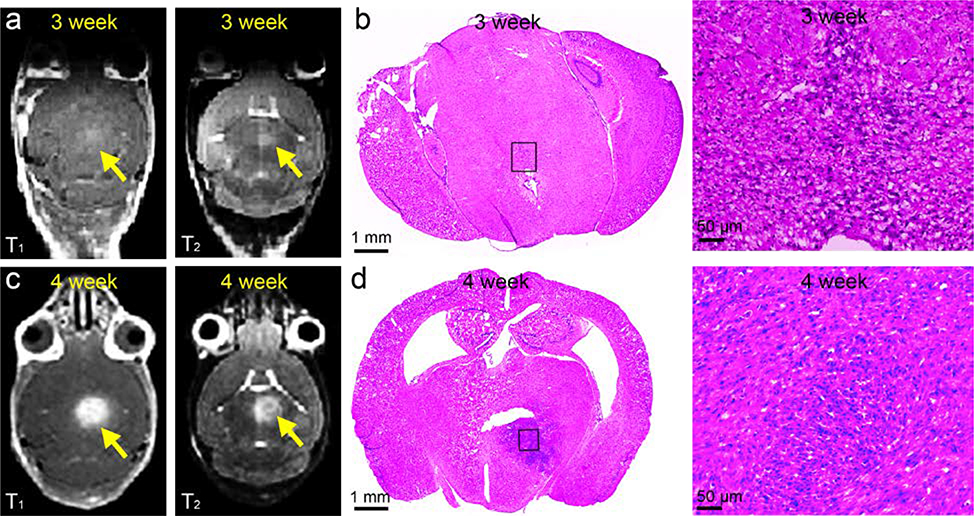

Next, we applied FUS to an established RCAS/TVA mouse DIPG model. Briefly, nestin-expressing brainstem progenitors of Nestin TVA; p53 floxed mice were infected at postnatal day 4–5 by the injection of virus producing cells (DF1s) expressing PDGF-B, H3.3K27M, and Cre (to delete p53 specifically in the tumor cells) at a ratio of 1:1:1. The cells were injected slowly over 2 minutes into the posterior fossa at 3 mm deep to lambda, into the brainstem of post-natal day 7 pups.1, 30 The anatomic characterization of tumor progression was characterized by MRI and histological variation was assessed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. At 3 weeks, MRI showed nearly undetectable signal in both T1-weighted and T2-weighted contrast enhanced images (Figure 2a). However, H&E staining of collected specimens revealed the presence of tumor cells within pons indicating the development of early tumors (Figure 2b).31 In comparison, contrast enhanced T1-weighted and T2-weighted images demonstrated significant hyperintensity in the pons of both 4-week-old and 5-week-old mice (Figure 2c and S5), indicating the significant invasion of tumors which was confirmed by the H&E staining of pons sectioned from 4-week-old mice (Figure 2b and 2d). Importantly, after MRgFUS treatment at the 3-week-old DIPG mice, enhanced signal was observed at the position of tumors in contrast enhanced MR images, which indicated the precise FUS targeting of the tumors that allowed the penetration of contrast agent through the disrupted BBTB (Figure S6). This demonstrated the efficiency and potential of MRgFUS to deliver reagents for early diagnosis and treatment of DIPG.

Figure 2.

Comparison of contrast enhanced T1 and T2 weighted MRI images of (a) 3-week-old DIPG mouse and related (b) H&E staining with MRI images at (c) 4-week-old DIPG mice and (d) H&E staining.

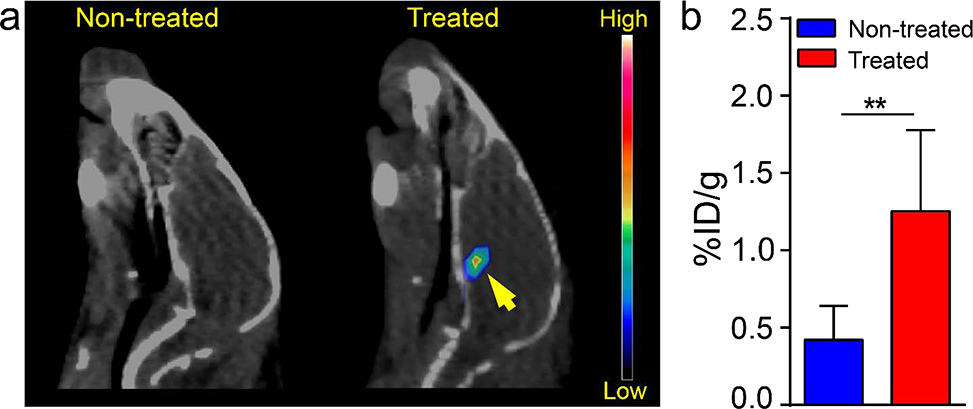

To further confirm the opening of BBTB for early detection and treatment of DIPG, PET/CT evaluation with/without FUS in the same mice was conducted using a short-lived radioisotope 68Ga (T1/2 = 67.7 mins) labeled hydrophilic radiotracer, 68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i (MW=1375.7 Da), in DIPG mice.32 The rapid decay of 68Ga enabled the comparison of the FUS treatment effect in the same mouse in a span of 2 days. Specifically, three-week-old DIPG mice without FUS treatment were injected intravenously with 7.4 MBq 68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i via tail vein and scanned with PET/CT at 1 h post injection, which showed no tracer uptake within pons (Figure 3a). After the decay of 68Ga, the same mice were treated with MRgFUS the next day prior to a second 68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i PET/CT scan. As shown in Figure 3a, significant PET signals were determined in the pons of mice with FUS treatment. Quantification showed that 68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i uptake in pons of treated mice (1.25 ± 0.53 %ID/g, n = 4) was approximately 2-fold higher than that acquired in non-treated mice (0.42 ± 0.22 %ID/g, n = 4, p<0.01), which demonstrated the effectiveness of MRgFUS for opening the BBTB in the setting of DIPG (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) In vivo PET/CT images and (b) the quantitative tumor uptake of 68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i in 3-week-old DIPG tumor mice with and without FUS treatment at 1 h post IV injection (** p<0.01, n = 4).

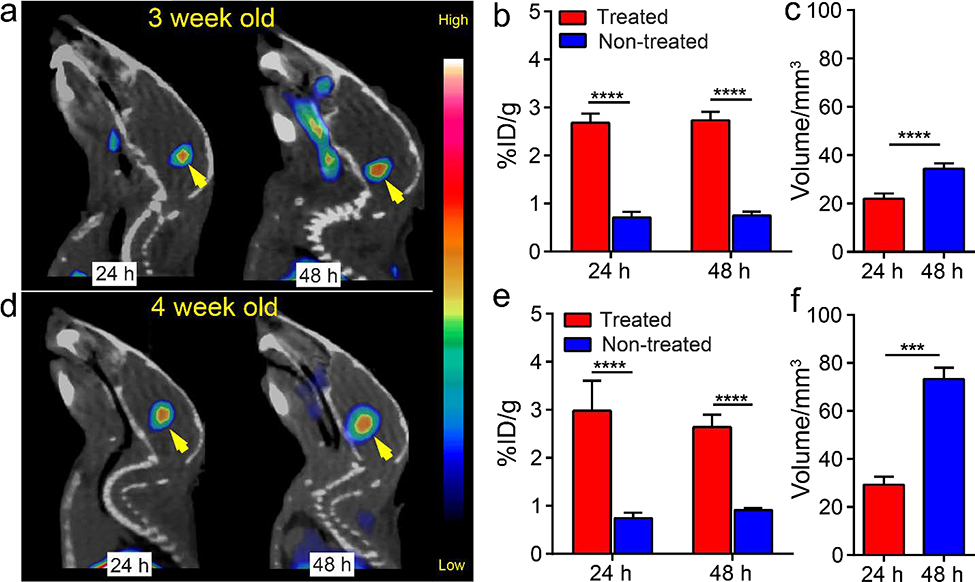

We next analyzed the effect of FUS on 64Cu-CuNCs accumulation and distribution within pons in 3 and 4-week old DIPG mice using PET/CT imaging. Mice were randomized into FUS treated and non-treated groups. As shown in Figure 4a, a strong PET signal was evident in the pons of both 3 and 4-week-old DIPG mice at 24 and 48 h post injection of 64Cu-CuNCs. Quantitative analysis showed similar tumor uptakes of 2.68 ± 0.20 %ID/g (n = 5) and 2.73 ± 0.18 %ID/g (n = 5) at 24 and 48 h post injection for FUS treated 3-week-old mice, values which were significantly higher than those in untreated mice (Figures 4b and S7, p<0.0001, n = 6). Additionally, the distribution volume of radioactive signal in the pons increased from 21.90 ± 2.24 mm3 to 34.4 ±2.22 mm3 between 24 and 48 hours (Figure 4c, p<0.01, n = 5 for both), suggesting the dynamic diffusion of 64Cu-CuNCs within tumors, consistent with our previous report.25 Furthermore, ex vivo autoradiography performed immediately after PET/CT imaging clearly showed distribution of 64Cu-CuNCs within the tumor in the FUS treated mice while minimal retention was observed in the pons of mice without FUS treatment. Quantification of the radioactivity within the pons revealed 2-fold higher counts in the treated mice than the non-treated mice, confirming the PET data (Figure S8). The similar tumor uptakes between the 24 and 48 h time points may be attributed to the closing of the transiently disrupted BBTB within a few hours of treatment.33 The prolonged intra-tumoral retention and dynamic diffusion of nanoclusters could have therapeutic benefit if they were loaded with anti-tumor agents.

Figure 4.

In vivo PET/CT images, quantification of tumor uptake and intra-tumoral distribution volumes of 64Cu-CuNCs at 24 h and 48 h post IV injection in (a, b, and c) 3-week-old and (d, e, and f) 4-week-old DIPG mice. (*** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, n = 3–6).

In the 4-week-old tumor mice, tumor uptakes showed similar profiles to those at 3 weeks with 2.98 ± 0.62 %ID/g and 2.64 ± 0.26 %ID/g determined in the pons at 24 and 48 h post injection (Figure 4d and 4e, p<0.0001, n = 3, Figure S9). However, the diffusion of the nanoclusters showed approximately two-fold increase from 24 h (29.3 ± 3.32 mm3, n=3) to 48 h (73.27 ± 4.74 mm, n=3, p<0.001) (Figures 4f). This could be a result of diminishing tumor integrity over time, resulting in a leakier tumor structure compared to DIPG tumors at 3 weeks, while still maintaining BBTB integrity that excludes the permeation of the nanoclusters. This retaining integrity of BBTB in 4-week-old mice was confirmed by the low signal in the non-treated mice, whose tumor uptake was comparable to the blood retention of circulating 64Cu-CuNCs in non-treated 3-week-old DIPG mice. Moreover, at late stage of this DIPG model (5-week-old), due to the deterioration of BBTB,34 64Cu-CuNCs accumulation was observed even without FUS treatment (Figure S10), which was further confirmed by T1 and T2 weighted MR images (Figure S5). Interestingly, in contrast to the reported low tumor uptake of 89Zr-bevacizumab in DIPG mice with disrupted BBTB,35 our combined strategy demonstrated significantly enhanced tumor delivery, diffusion and retention of 64Cu-CuNCs as a model-drug in DIPG mice, indicating the unique advantages of our ultrasmall nanoclusters.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we examined the optimal FUS pressure to open BBB of naive mice for effective delivery of 64Cu-CuNCs to pons. Using a hydrophilic, short-lived PET tracer, 68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i, we demonstrated the effectiveness of MRgFUS to precisely target the pons and open the BBTB for potential drug delivery. Following MRgFUS treatment, 64Cu-CuNCs exhibited significant tumor uptake, dynamic distribution within tumors, and prolonged intra-tumoral retention within DIPG tumors. Together, these findings suggest that FUS-enhanced delivery of biodegradable nanoclusters may provide a much-needed advancement in the treatment of DIPG.

Comparing to other trans-BBB strategies,5, 36 our MRgFUS strategy demonstrated effective disruption of BBTB and delivery of radiolabeled 64Cu-CuNCs to the DIPG tumor with little normal tissue damage.25–26 The use of ultrasmall 64Cu-CuNCs could facilitate the tumor penetration, as well as the rapid renal clearance to further reduce in vivo toxicity. In future studies, once drug is loaded onto CuNCs, the biodegradability of CuNCs could promote rapid in situ drug release upon tumor entry to make it a better treatment for diffused tumor cells.24 However, there are also some limitations in our studies. The safety evaluation of MRgFUS has only been assessed by histology.25–26 Future studies are needed to carefully evaluate the inflammatory response and chronic effect due to the FUS disruption of BBTB. The 64Cu-CuNC used for this proof-of-concept study was a non-targeted nanocluster. Future studies need to focus on targeted approach based on the specific expression of certain biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All animal experiments were carried out in compliance with the institutional animal care and usage committee (IACUC) guidelines of Washington University. This work is supported by Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital (MC-II-2017-661, YL), The Children’s Hospital Foundation (JBR). NIH (R01EB027223 and R01MH116981, HC).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.0c02297

Experimental methods, including the synthesis of 68Ga-DOTA-ECL1i and 64Cu-CuNCs, characterization, cytotoxicity assay, animal model, MRgFUS, micro-PET/CT, autoradiography, histology of tumor tissues, and statistical analysis. Flowcharts of the study groups (S1); characterization of CuNCs (S2 and Table S1); PET/CT images of 64Cu-CuNCs in WT mice under 0.72 and 0.85 MPa FUS pressure (S3); H&E images of FUS non-treated and treated sides of mouse pons under different FUS pressure (S4); MR images of 5-week-old DIPG mice (S5); MRI images of 3-week-old DIPG mice before and after FUS (S6); PET/CT images of 64Cu-CuNCs in DIPG mice without FUS treatment (S7); autoradiography of 3-week-old DIPG mouse slides (S8); quantification of tumor uptake of 64Cu-CuNCs showing in standard uptake value (S9); and PET/CT images of 5-week-old DIPG mice (S10).

REFERENCES

- (1).Misuraca KL; Cordero FJ; Becher OJ Pre-Clinical Models of Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Front. Oncol 2015, 5, 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Xu C; Liu X; Geng Y; Bai Q; Pan C; Sun Y; Chen X; Yu H; Wu Y; Zhang P; Wu W; Wang Y; Wu Z; Zhang J; Wang Z; Yang R; Lewis J; Bigner D; Zhao F; He Y; et al. Patient-Derived DIPG Cells Preserve Stem-Like Characteristics and Generate Orthotopic Tumors. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 76644–76655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Vanan MI; Eisenstat DD DIPG in Children - What Can We Learn from the Past? Front. Oncol 2015, 5, 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Becher OJ; Millard NE; Modak S; Kushner BH; Haque S; Spasojevic I; Trippett TM; Gilheeney SW; Khakoo Y; Lyden DC; De Braganca KC; Kolesar JM; Huse JT; Kramer K; Cheung NV; Dunkel IJ A Phase I Study of Single-Agent Perifosine for Recurrent or Refractory Pediatric CNS and Solid Tumors. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0178593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Warren KE Beyond the Blood:Brain Barrier: The Importance of Central Nervous System (CNS) Pharmacokinetics for the Treatment of CNS Tumors, Including Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Front. Oncol 2018, 8, 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gumerlock MK; Belshe BD; Madsen R; Watts C Osmotic Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and Chemotherapy in the Treatment of High Grade Malignant Glioma: Patient Series and Literature Review. J. Neurooncol 1992, 12, 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Mehta AM; Sonabend AM; Bruce JN Convection-Enhanced Delivery. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 358–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lee Titsworth W; Murad GJ; Hoh BL; Rahman M Fighting Fire with Fire: The Revival of Thermotherapy for Gliomas. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 565–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Chen KT; Wei KC; Liu HL Theranostic Strategy of Focused Ultrasound Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening for CNS Disease Treatment. Front. Pharmacol 2019, 10, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Konofagou EE; Tung YS; Choi J; Deffieux T; Baseri B; Vlachos F Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol 2012, 13, 1332–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fan C-H; Yeh C-K Microbubble-Enhanced Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood–Brain Barrier Opening for Local and Transient Drug Delivery in Central Nervous System Disease. J. Med. Ultrasound 2014, 22, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Sun T; Zhang Y; Power C; Alexander PM; Sutton JT; Aryal M; Vykhodtseva N; Miller EL; McDannold NJ Closed-Loop Control of Targeted Ultrasound Drug Delivery across the Blood-Brain/Tumor Barriers in a Rat Glioma Model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114, E10281–E10290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Alli S; Figueiredo CA; Golbourn B; Sabha N; Wu MY; Bondoc A; Luck A; Coluccia D; Maslink C; Smith C; Wurdak H; Hynynen K; O’Reilly M; Rutka JT Brainstem Blood Brain Barrier Disruption Using Focused Ultrasound: A Demonstration of Feasibility and Enhanced Doxorubicin Delivery. J. Control. Release 2018, 281, 29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bretsztajn L; Gedroyc W Brain-Focussed Ultrasound: What’s the “FUS” All About? A Review of Current and Emerging Neurological Applications. Br. J. Radiol 2018, 91, 20170481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Park SH; Kim MJ; Jung HH; Chang WS; Choi HS; Rachmilevitch I; Zadicario E; Chang JW Safety and Feasibility of Multiple Blood-Brain Barrier Disruptions for the Treatment of Glioblastoma in Patients Undergoing Standard Adjuvant Chemotherapy. J. Neurosurg 2020, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lipsman N; Meng Y; Bethune AJ; Huang Y; Lam B; Masellis M; Herrmann N; Heyn C; Aubert I; Boutet A; Smith GS; Hynynen K; Black SE Blood–Brain Barrier Opening in Alzheimer’s Disease Using MR-Guided Focused Ultrasound. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Carpentier A; Canney M; Vignot A; Reina V; Beccaria K; Horodyckid C; Karachi C; Leclercq D; Lafon C; Chapelon JY; Capelle L; Cornu P; Sanson M; Hoang-Xuan K; Delattre JY; Idbaih A Clinical Trial of Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption by Pulsed Ultrasound. Sci. Transl. Med 2016, 8, 343re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Long W; Yi Y; Chen S; Cao Q; Zhao W; Liu Q Potential New Therapies for Pediatric Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Front. Pharmacol 2017, 8, 495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bredlau AL; Dixit S; Chen C; Broome AM Nanotechnology Applications for Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Curr. Neuropharmacol 2017, 15, 104–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Khan AR; Yang X; Fu M; Zhai G Recent Progress of Drug Nanoformulations Targeting to Brain. J. Control. Release 2018, 291, 37–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Erel-Akbaba G; Carvalho LA; Tian T; Zinter M; Akbaba H; Obeid PJ; Chiocca EA; Weissleder R; Kantarci AG; Tannous BA Radiation-Induced Targeted Nanoparticle-Based Gene Delivery for Brain Tumor Therapy. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 4028–4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tang W; Fan W; Lau J; Deng L; Shen Z; Chen X Emerging Blood-Brain-Barrier-Crossing Nanotechnology for Brain Cancer Theranostics. Chem. Soc. Rev 2019, 48, 2967–3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rozhkova EA; Ulasov I; Lai B; Dimitrijevic NM; Lesniak MS; Rajh T A High-Performance Nanobio Photocatalyst for Targeted Brain Cancer Therapy. Nano Lett 2009, 9, 3337–3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wu M; Chen W; Chen Y; Zhang H; Liu C; Deng Z; Sheng Z; Chen J; Liu X; Yan F; Zheng H Focused Ultrasound-Augmented Delivery of Biodegradable Multifunctional Nanoplatforms for Imaging-Guided Brain Tumor Treatment. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 2018, 5, 1700474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Sultan D; Ye D; Heo GS; Zhang X; Luehmann H; Yue Y; Detering L; Komarov S; Taylor S; Tai YC; Rubin JB; Chen H; Liu Y Focused Ultrasound Enabled Trans-Blood Brain Barrier Delivery of Gold Nanoclusters: Effect of Surface Charges and Quantification Using Positron Emission Tomography. Small 2018, 14, 1703115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ye D; Sultan D; Zhang X; Yue Y; Heo GS; Kothapalli S; Luehmann H; Tai YC; Rubin JB; Liu Y; Chen H Focused Ultrasound-Enabled Delivery of Radiolabeled Nanoclusters to the Pons. J. Control. Release 2018, 283, 143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ye D; Zhang X; Yue Y; Raliya R; Biswas P; Taylor S; Tai YC; Rubin JB; Liu Y; Chen H Focused Ultrasound Combined with Microbubble-Mediated Intranasal Delivery of Gold Nanoclusters to the Brain. J. Control. Release 2018, 286, 145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Heo GS; Zhao Y; Sultan D; Zhang X; Detering L; Luehmann HP; Zhang X; Li R; Choksi A; Sharp S; Levingston S; Primeau T; Reichert DE; Sun G; Razani B; Li S; Weilbaecher KN; Dehdashti F; Wooley KL; Liu Y Assessment of Copper Nanoclusters for Accurate in vivo Tumor Imaging and Potential for Translation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 19669–19678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Chen H; Konofagou EE The Size of Blood-Brain Barrier Opening Induced by Focused Ultrasound Is Dictated by the Acoustic Pressure. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 2014, 34, 1197–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Misuraca KL; Hu G; Barton KL; Chung A; Becher OJ A Novel Mouse Model of Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Initiated in Pax3-Expressing Cells. Neoplasia 2016, 18, 60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Caretti V; Zondervan I; Meijer DH; Idema S; Vos W; Hamans B; Bugiani M; Hulleman E; Wesseling P; Vandertop WP; Noske DP; Kaspers G; Molthoff CF; Wurdinger T Monitoring of Tumor Growth and Post-Irradiation Recurrence in a Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Mouse Model. Brain Pathol. 2011, 21, 441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Heo GS; Kopecky B; Sultan D; Ou M; Feng G; Bajpai G; Zhang X; Luehmann H; Detering L; Su Y; Leuschner F; Combadiere C; Kreisel D; Gropler RJ; Brody SL; Liu Y; Lavine KJ Molecular Imaging Visualizes Recruitment of Inflammatory Monocytes and Macrophages to the Injured Heart. Circ. Res 2019, 124, 881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Samiotaki G; Konofagou EE Dependence of the Reversibility of Focused- Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening on Pressure and Pulse Length in vivo. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2013, 60, 2257–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kossatz S; Carney B; Schweitzer M; Carlucci G; Miloushev VZ; Maachani UB; Rajappa P; Keshari KR; Pisapia D; Weber WA; Souweidane MM; Reiner T Biomarker-Based PET Imaging of Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma in Mouse Models. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2112–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Jansen MH; Lagerweij T; Sewing AC; Vugts DJ; van Vuurden DG; Molthoff CF; Caretti V; Veringa SJ; Petersen N; Carcaboso AM; Noske DP; Vandertop WP; Wesseling P; van Dongen GA; Kaspers GJ; Hulleman E Bevacizumab Targeting Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma: Results of 89Zr-Bevacizumab PET Imaging in Brain Tumor Models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 2166–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Patel MM; Patel BM Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier: Recent Advances in Drug Delivery to the Brain. CNS Drugs 2017, 31, 109–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.