Abstract

Although best practice recommendations exist regarding school-based healthy eating and physical activity policies, practices, and programs, research indicates that implementation is poor. As the field of implementation science is rapidly evolving, an update of the recent review of strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating and physical activity interventions in schools published in the Cochrane Library in 2017 was required. The primary aim of this review was to examine the effectiveness of strategies that aim to improve the implementation of school‐based policies, practices, or programs to address child diet, physical activity, or obesity. A systematic review of articles published between August 31, 2016 and April 10, 2019 utilizing Cochrane methodology was conducted. In addition to the 22 studies included in the original review, eight further studies were identified as eligible. The 30 studies sought to improve the implementation of healthy eating (n = 16), physical activity (n = 11), or both healthy eating and physical activity (n = 3). The narrative synthesis indicated that effect sizes of strategies to improve implementation were highly variable across studies. For example, among 10 studies reporting the proportion of schools implementing a targeted policy, practice, or program versus a minimal or usual practice control, the median unadjusted effect size was 16.2%, ranging from –0.2% to 66.6%. Findings provide some evidence to support the effectiveness of strategies in enhancing the nutritional quality of foods served at schools, the implementation of canteen policies, and the time scheduled for physical education.

Keywords: School, Implementation, Nutrition, Physical activity, Policy

Implications.

Practice: Findings of the review provide guidance for health promotion practitioners and jurisdictions working within school-based settings to implement World Health Organization obesity-prevention recommendations

Policy: The review identified that the implementation of several policies have facilitated improvements in the availability of healthy foods in schools, of magnitudes that could lead to substantial improvements in public health nutrition.

Research: The review builds on current literature to provide greater clarity on the effect of strategies to support the implementation of evidence-based healthy eating, physical activity, and obesity-prevention policies and practices, a critical component to achieve the public health benefits of such policies and practices.

INTRODUCTION

An unhealthy diet, inadequate physical activity, and excessive weight gain are independent risk factors for the leading causes of death and disability globally, including cancer and cardiovascular disease [1]. In childhood and adolescents, a healthy diet [2, 3], physical activity [4–6], and healthy weight [7] have also been found to be independently associated with immediate positive health outcomes, including improved mental health and academic performance. Additionally, as health behaviors developed during childhood have been found to track into adulthood [8], interventions to address these risk factors are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and governments internationally as part of population health and chronic disease prevention strategies [9].

Schools represent an attractive and important setting for health promotion initiatives as they provide continual access to children during a critical period of their development [10, 11]. Systematic reviews have identified well over 100 randomized trials of school-based interventions targeting student diet, physical activity, or obesity and have demonstrated that such interventions can be effective in reducing associated health risks [12–14]. On the basis of such evidence, national and international best-practice guidelines have been established acknowledging the potential for school-based settings to influence the development of children’s healthy eating and physical activity behaviors [15–18]. These evidence-based guidelines recommend schools adopt a range of policies, practices, and programs, such as the scheduling and provision of physical activity and active play opportunities, reducing the availability of unhealthy foods for sale at schools and alignment of foods services with national dietary guidelines [15, 18, 19].

Despite the existence of these best-practice guidelines, research suggests that schools fail to routinely implement evidence-based policies, practices, and programs. For example, the 2014 report card of physical activity in Ireland found that only 17% of primary schools were providing the mandated 2 hr of compulsory physical education per week [20]. Similarly, studies of Australian primary schools have found that only 5%–35% of Australian schools comply with mandated school canteen policies regarding the availability of unhealthy foods and beverages [21], whilst just 10% of middle and high schools within the USA prohibit the sale of sugar-sweetened beverages other than soda [22]. Without routine implementation, the public health benefits of such policies and practices promoting healthy eating and physical activity will not be fully achieved.

The field of implementation science seeks to address this issue through the generation of evidence to facilitate the use of evidence-based policies, practices, and programs [23]. Implementation science research seeks to identify effective strategies, such as educational outreach visits, reminders, or audit and feedback, which best support the integration of evidence-based practices into a specific setting [23, 24]. Implementation trials seek to assess the impact of such implementation strategies on the measures of the implementation of an evidence-based policy, practice, or program [23, 24]. Relative to trials testing the efficacy of behavioral interventions, few implementation trials have been conducted examining strategies to best implement evidence-based healthy eating, physical activity, or obesity-prevention interventions in the school setting [25].

We conducted a comprehensive Cochrane review on the topic in 2017, which included studies (randomized and nonrandomized) published until August 2016 [25]. The review identified 27 studies, 15 of which aimed to improve the implementation of healthy eating practices, and 6 studies targeted physical activity (the remaining studies pertained to alcohol and tobacco prevention) [25]. Findings of the review was mixed, with inconsistent improvements in the implementation of policies, practices, or programs reported across studies. Additionally, considerable clinical heterogeneity in the type of implementation strategies tested, policies, practices, and programs targeted, and outcomes assessed across the included studies was evident within the review [25]. Overall, the impact of strategies on the implementation of physical activity and healthy eating policies, practices, and programs was unclear, and the certainty of the evidence was low [25].

We are not aware of any review of school-based implementation interventions undertaken since that review. The field of implementation science, however, is rapidly evolving and a number of implementation studies targeting healthy eating and physical activity policies, practices, and programs have been published in recent years [26–28]. The addition of new studies may provide greater clarity regarding the effect of such strategies on the implementation of evidence-based policies, programs, and practices in schools given variable and inconclusive findings from the previous review. The aim of this review, therefore, was to update our previous review by Wolfenden et al. to reflect the current state of the evidence.

OBJECTIVES

The primary aim of this review was to examine the effectiveness of strategies that aim to improve the implementation of school‐based policies, practices, or programs to address child diet, physical activity, or obesity.

METHODS

This review aligns with the reporting guidelines specified within the 2009 PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews [29] (Supplementary File I) and utilized Cochrane methodology to replicate the previous review by Wolfenden et al. [25].

Selection criteria

Types of studies

“Implementation” was defined as the use of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence‐based health interventions and to change practice patterns within specific settings [30]. Any study (randomized or nonrandomized) conducted at any scale with a parallel control group that compared a strategy to implement school-based policies, practices, or programs to address child diet, physical activity, overweight, or obesity by school staff to “no intervention,” “usual” practice, or a different implementation strategy was eligible for inclusion. Unlike the original review, we excluded studies solely targeting the implementation of tobacco or alcohol use prevention policies, practices, or programs as these were not the focus of this review update.

Types of interventions

Studies employing any strategy with the primary aim of improving implementation of healthy eating, physical activity, or obesity prevention policies, practices, or programs in schools were eligible. Strategies must have aimed to improve the implementation of policies, practices, or programs by usual school staff. Strategies could include quality improvement initiatives, education and training, performance feedback, prompts and reminders, implementation resources (e.g., manuals), financial incentives, penalties, communication and social marketing strategies, professional networking, the use of opinion leaders, implementation consensus processes, or other strategies [25].

Types of participants

Eligible studies were set in schools (e.g., primary, elementary, middle, and secondary) where the age of students is predominately between 5 and 18 years [31]. Study participants could be any stakeholders who may influence the uptake, implementation, or sustainability of the target health promoting policy, practice, or program in schools, including teachers, managers, cooks/catering staff, or other staff of schools and education departments.

Types of outcome measures

Studies with any objectively or subjectively (self‐reported) assessed measure of school policy, practice, or program implementation—including uptake, partial/complete uptake (e.g., consistent with protocol/design), or routine use—were included. Implementation could have occurred at any scale (e.g., local, national, or international). Implementation outcomes (e.g., frequency of practice implementation by teachers) must have been undertaken by a school or routine school personnel and not those undertaken by paid research personnel. Child-level outcomes (e.g., child diet and physical activity) were not considered as implementation outcomes. Studies collecting outcome data at follow-up only for an implementation outcome were included for randomized trial designs only (i.e., equivalent baseline values assumed or differ only by chance) or if baseline values were assumed to be zero (i.e., a school policy did not exist at baseline). Implementation outcome data may have been obtained from audits of school records, questionnaires or surveys of staff, direct observation or recordings, examination of routinely collected information from government departments (such as compliance with food standards or breaches of department regulations), or other sources.

Search strategy

The original search by Wolfenden et al. was undertaken for studies published up to August 31, 2016 [25]. Small amendments were made to the original search strategy to improve the sensitivity of the search, which was conducted by an experienced research librarian. This updated review included eligible studies published up until April 10, 2019, from a search of the following electronic databases: Cochrane Library, including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE; MEDLINE InProcess & Other Non‐Indexed Citations; Embase Classic and Embase; PsycINFO; Education Resource Information Center; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; Dissertations and Theses; and SCOPUS (Appendix II Medline search strategy). Additionally, a search of the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) conducted by Wolfenden et al. was replicated for this review. The “Characteristics of Ongoing Studies” section of the original review was also searched for potentially eligible studies that were unpublished at the time of the first review [25].

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

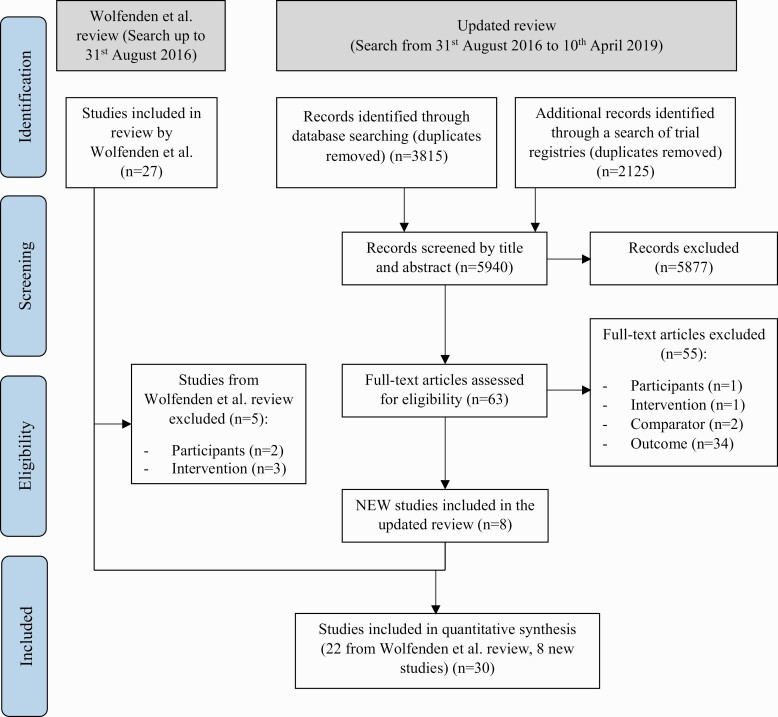

Title and abstract screening for eligible studies was performed independently by review authors in pairs. Authors were not blind to author or journal information. For potentially eligible studies, full texts of manuscripts were examined for eligibility by a pair of review authors independently. Reasons for exclusion were documented for all studies and recorded in Fig. 1. Disagreements between review authors were resolved via consensus or, when required, by a third author.

Fig 1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was completed independently by two authors unblinded to author and journal information. Discrepancies between review authors were resolved via consensus or by a third author when required. Information extracted from eligible studies included: study eligibility and design; date of publication; country and demographic characteristics of participants; number of experimental conditions; characteristics of employed implementation strategies; study outcomes of interest and information to allow the assessment of risk of bias. Implementation strategies were classified according to the Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) taxonomy [32] (Appendix III).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors independently assessed risk of bias within each included study using the “Risk of Bias” tool described within the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [33]. The following domains were assessed for individual studies and outcomes to determine an overall risk of bias: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and “other” potential sources of bias. For nonrandomized trials, an additional “potential confounding” domain was also assessed, defined as the risk that an unmeasured characteristic shared by those allocated to receive the implementation intervention (or strategy), rather than the intervention itself, was responsible for reported outcomes [34]. Additional domains were also used to assess cluster-randomized controlled trials, including: recruitment to cluster, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis, and compatibility with individually randomized controlled trials [33]. Disagreements between review authors were resolved via consensus or, when required, by a third author.

Measurement of treatment effect

Substantial study heterogeneity in outcomes and measures used to assess implementation precluded meta‐analysis and presented considerable synthesis challenges. As such, a narrative synthesis was conducted collectively with studies from the original and updated review. First, we summarized the characteristics of included studies based on population, and “intervention” (implementation strategy categorized based on EPOC taxonomy [32]) characteristics. Second, to provide a high-level summary of findings, we described the effect size of the primary policy, practice, or program implementation outcome measure for each study and summarized this across studies for each broad category of implementation outcomes (e.g., score-based measures, proportion of time implementing a practice, or frequency of implementation) [25, 35]. Effect sizes were calculated by subtracting the change from baseline on the primary implementation outcome for the control (or comparison) group from the change from baseline in the experimental or intervention group. We reverse-scored implementation measures that did not represent an improvement (e.g., proportion of schools serving unhealthy food items) [25, 35]. For studies with multiple follow‐up periods, data from the final follow‐up period reported was extracted and subtracted from baseline [25, 35, 36]. If data to enable the calculation of change from baseline were unavailable, the differences between groups postintervention were used. Where there were two or more primary implementation outcome measures, standardized measures of effect size were calculated for each outcome, measures were ranked based on their size of effect, and the median measure was used (and range reported) [35, 36].

Where the primary outcome measure was not identified by the study authors in the published manuscripts, the implementation outcome on which the study sample size calculation was based was used or, in its absence, the median effect size of all measures judged to be implementation outcomes reported in a manuscript was calculated and the range reported [25, 35, 36]. The inclusion of such effect sizes is for descriptive purposes and should not be considered as pooled estimates of effect as they do not weigh study effects by the inverse of their variance, nor do they consider study issues of study quality or design. Finally, we present a narrative synthesis of all studies, followed by a narrative synthesis of individual studies by the risk factor (physical activity or diet) targeted by the intervention.

RESULTS

The updated search (August 31, 2016 to April 10, 2019) identified 3,815 unique records of which 62 full-text records and one unpublished study (identified via the trial registry search, findings have since been published [37]) were assessed for eligibility (see Fig. 1). Fifty-five records were excluded following full-text screening for the following reasons: wrong participants (n = 1); wrong intervention (n = 1); no comparator (n = 2); and inappropriate outcomes (n = 34). Studies were excluded based on “inappropriate outcomes” if it did not measure implementation of a policy, practice, or program.

In this review update, seven new published studies [26–28, 38–42] and one unpublished study were identified for inclusion (see Fig. 1). Of the 27 studies included in the original Cochrane review covering multiple health risks, 22 studies [43–64] examining healthy eating, physical activity, or obesity prevention policy or practice implemented were included in this review update (see Fig. 1 for reasons for exclusion). In total, 30 studies were included in this review update. See Appendix I for characteristics of included studies.

Types of studies

Collectively from the 30 studies included from the original and updated review, 19 were conducted in the USA, 7 in Australia, 2 in Canada, and 1 each in New Zealand and the Netherlands. Nineteen included studies employed randomized designs (including 15 cluster randomized) and the remaining 11 studies were nonrandomized with a parallel control group. Studies were conducted between 1985 [59] and 2018 [65], with the duration of the studies varying from 20 weeks [26] to 4 years [49]. Twenty-six of the 30 included studies compared an implementation strategy to a control group or usual practice, whilst the remaining four studies directly compared different implementation strategies [39, 40, 46, 49].

Participants

The number of schools participating in the studies included in the review varied. The largest study recruited 828 schools [52], whilst the smallest study recruited two schools. The majority of studies (n = 22) were conducted within primary (or elementary) schools, which cater for children aged 5–12 years. The remaining studies were conducted in middle schools (n = 5) catering for children aged 11–14 years and secondary schools (n = 3) catering for children aged 13–18 years. All included studies were conducted within high-income countries.

Interventions

Sixteen studies tested strategies to implement healthy eating policies, practices, or programs, 11 tested strategies targeting physical activity policies or practices, and 3 tested strategies targeting both healthy eating and physical activity. A comprehensive description of the existing studies in the Cochrane Review are available in the “Characteristics of Included Studies” table of the manuscript [25], whilst a summary of all included 30 studies is provided in Appendix I.

All studies examined multistrategy implementation interventions. The number of implementation strategies, as characterized by the EPOC Taxonomy [32] (see Appendix III), ranged from two to nine (mean number of strategies = 6.5). While there was considerable heterogeneity in the strategies tested, 21 studies tested educational materials and educational meetings in combination with other strategies. Of those other strategies tested, educational outreach visits or academic detailing (n = 10) and audit with feedback (n = 4) were the most common. No study tested the effectiveness of just one implementation strategy and only two studies [26, 38] tested the same combination of strategies. A summary of the implementation strategies and effects of all included studies is provided in Appendix I.

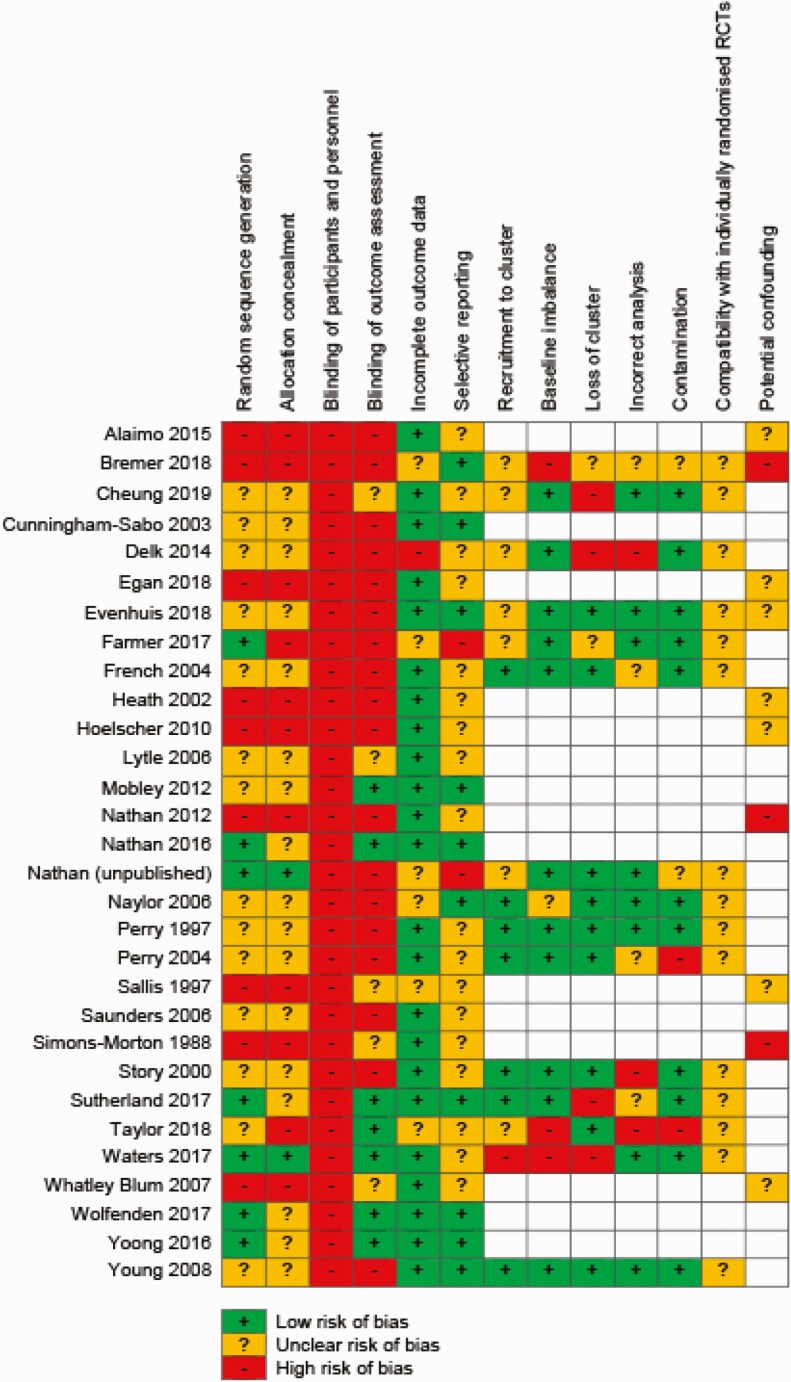

Assessment of risk of bias of included studies

The “Risk of Bias” assessment for the included studies for each domain is presented in Fig. 2 and described below.

Fig 2.

Risk of bias summary.

Allocation

Risk of bias varied across studies. Nine studies, including eight with nonrandomized designs, were assessed as high risk of selection bias [26, 39, 43, 48, 49, 51, 52, 57, 61]. Thirteen studies, including four RCTs were assessed as unclear risk of selection bias as methods of sequence generation and allocation were not reported [44, 46, 47, 50, 51, 54–56, 58, 64, 66, 67]. While four studies were assessed as low risk of bias for random sequence generation, the method of allocation concealment was unclear [53, 60, 62, 63]. Two studies were assessed as low risk for both sequence generation and allocation concealment [27, 37].

Blinding

All studies were assessed as high risk of performance bias as study participants and personnel (e.g., school staff) were not blinded to group allocation. Detection bias varied across studies depending on whether implementation was assessed via self-report (high risk) or objective measures (low risk). Seventeen of the included studies were assessed as high risk [26, 28, 37, 41, 43, 44, 46–49, 52, 54–56, 58, 66, 67] and seven studies were assessed as low risk of detection bias [27, 42, 51, 53, 60, 62, 63]. The remaining five studies were assessed as unclear risk of detection bias due to insufficient information regarding the blinding of data collection staff provided [38, 50, 57, 59, 61].

Incomplete outcome data

The majority of studies (n = 23) were assessed as low risk of bias as either all or most participating schools were present at follow-up and/or sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of missing data. The risk of attrition was assessed as unclear in six studies, as insufficient information regarding the loss of schools and treatment of missing data were provided [26, 37, 41, 42, 54, 57]. One study was assessed as high risk of attrition due to untreated missing data at follow-up [46].

Selective reporting

Ten studies were assessed as low risk of selective reporting as a trial registration or a published protocol paper was identified and all a priori determined outcomes were reported [26, 44, 51, 53, 54, 60, 62–64, 67]. Two studies were classified as high risk for selective reporting as the implementation outcome was not previously registered in the available protocol or trial registration [37, 41]. For the remaining studies (n = 18), the risk of reporting bias was deemed unclear as a published protocol or trial registration was not identified.

Other potential sources of bias

For studies using a cluster-RCT design (n = 15), additional risk of bias domains were assessed. Potential risk of recruitment (to cluster) was assessed as low for seven studies as randomization occurred either postrecruitment or postbaseline data collection [47, 54–56, 58, 60, 64]. Seven studies were assessed as unclear [26, 37, 38, 41, 42, 46, 67], whilst the remaining study [27] was assessed as high risk of bias due to randomization occurring prior to recruitment and a lack of blinding of recruiters. For risk of bias due to baseline imbalances, the majority of studies (n = 11) were assessed as low risk as studies accounted for imbalances by making adjustments for baseline differences during analyses, stratifying by school characteristics or through random allocation of schools to experimental groups [37, 38, 41, 46, 47, 55, 56, 58, 60, 64, 67]. Three studies were assessed as high risk [26, 27, 42], while the remaining study [54] was at unclear risk of bias due to baseline imbalance. Four studies were assessed as high risk for loss of clusters [27, 38, 46, 60]. Three studies were high risk of bias due to incorrect analysis [42, 46, 58], while eight studies were assessed as low risk [27, 37, 38, 41, 54, 56, 64, 67] and the remaining studies (n = 4) at unclear risk [26, 47, 55, 60]. Risk of contamination was assessed as low for the majority of clustered studies (n = 11), with only two studies assessed as high [42, 55] and the remaining two studies unclear [26, 37].

The potential of confounding factors was assessed as an additional risk of bias domain for nonrandomized trial designs. Of the seven nonrandomized studies, three were considered as high risk of confounding [26, 52, 59], while it was unclear in the remaining five studies whether confounders had been sufficiently adjusted for [39, 43, 57, 61, 67].

Overall effect of implementation support on policy, practice, or program implementation

Of the 30 included studies, 19 reported significant improvements in at least one implementation outcome (including the one unpublished study) [44, 46–50, 52–58, 60–62, 64, 68]; 3 studies did not report any significant improvements in implementation [26, 43, 63] and 8 did not report any significance tests on such outcomes [27, 38, 39, 42, 51, 59, 66, 67].

Among 10 studies reporting dichotomous implementation strategy outcomes—the proportion of schools or school staff (e.g., classes) implementing a targeted policy, practice, or program—versus a minimal or usual practice control, the median unadjusted (improvement) effect size was 16.2% and ranged from –0.2% to 66.6% [27, 41, 50–53, 60, 62–64].

Six studies reported the percentage of an intervention program or program content that had been implemented, the effects of which were mixed [47, 55, 56, 58, 60, 61]. The unadjusted median effect, relative to the control in the proportion of program or program content implemented, was 23.65% (range –8% to 43%) [47, 55, 56, 58, 60, 61].

Four studies reported the impact of implementation strategies on the time per week that teachers spent implementing physical activity or physical education (PE) lessons, with improvements, relative to control ranging from 5.7 to 54.9 min per week (median = 36.6 min per week; including the one unpublished study) [38, 54, 57].

Among studies reporting other continuous implementation outcomes (e.g., quantity of physical activity lessons), findings were mixed [43, 44, 46, 48, 49, 59, 64, 66]. For example, across the three studies assessing the availability of fruit and vegetables within schools, the median effect size was 1.15 and ranged from 0.64 to 1.23 [42, 55, 58].

Substantial variability in the type of implementation strategies employed in the included studies prevented the impact of specific implementation support strategies, or combinations thereof, from being examined. However, most studies included educational meetings, educational materials in addition to other strategies. The effectiveness of such strategies to achieve improvements in measures of implementation were mixed.

Implementation of healthy eating policies, practices, and programs

Nineteen of the 30 included studies targeted the implementation of healthy eating practices (13 studies in primary, 4 in middle, and 2 in secondary schools). Studies to improve the implementation of healthy eating policies and practices were dominated by studies to improve the nutritional content or availability of healthy foods as part of U.S. school food services (n = 13). In general, such studies reported small improvements in food provision. For example, Cunningham et al. reported reductions in the percentage of energy from fat provided at school breakfast and lunch from –3.3% to –2.7% [44]. Percentage of fat in school meals was reported as reduced by up to 4% in the study by Heath and Coleman [48]. Similarly, in the study by Perry et al., modest although significant reductions were reported in the percentage of kilocalories from fat (–4.3%) and milligrams of sodium (–100.5) in school lunches [56].

Significant improvements were also reported across a range of measures of the percentage of food and beverage items meeting nutrient and portion criteria in a study by Whatley Blum et al. [61]. U.S. studies targeting improvements in the availability of fruits and vegetables in à la carte lines typically significantly increased the mean number of fruit and vegetables options available by between 0.5 to 1.37 [58] or the proportion of schools selling such foods by between 4% and 12% [50]. There was consistent evidence of large effects from Australian randomized trials demonstrating improvement in the availability of healthy foods at school canteens [53, 62, 63]. Three trials demonstrated a dose–response relationship between the intensity of implementation support and school compliance with canteen policies. In the trial by Wolfenden et al., assessing the most intensive implementation strategy—comprised of nine implementation strategies—more than 70% of schools that received multicomponent implementation support (vs. 3% in the control) did not regularly sell foods that were restricted or banned from sale by healthy canteen guidelines, and more than 80% (versus 27% in the control) had more than half of all foods for sale as healthy (“green”) products [62]. An Australian study also reported significant improvement relative to control (16%) in the implementation of fruit and vegetable breaks during class time [52]. Large changes were also reported in a small randomized trial (12 schools per group), in the presence of a written school nutrition or policy, but not canteen policy, in a trial by Waters et al. [27].

Implementation of physical activity policies, practices, and programs

Fourteen of the 30 included studies targeted the implementation of physical activity policies and practices (nine studies in primary, four in middle, and one in secondary school). Studies testing strategies to improve the implementation of physical activity policies and practices focused on measures of time that classroom teachers spent delivering PE or structured physical activity each week, the quality of PE lessons (e.g., lesson time allocated to children engaging in physical activity), or the implementation of specific elements of physical activity interventions [26, 27, 38, 39, 41, 46, 49, 54, 56, 57, 60, 64, 66]. Studies targeting the time spent on PE typically saw significant improvements following multistrategy implementation support [38, 54, 57]. For example, in their Canadian study, Naylor et al. reported significant improvements in classroom time spent on PE relative to control of up to 1 hr per week [54]. Similarly, one study by Nathan et al. found significant improvements in the minutes per day that teachers scheduled physical activity relative to control [37]. Sallis et al. found significant increases in the duration per week of PE lessons relative to control of 26.6 min and significant increases in the frequency of PE lessons a week [57]. However, Cheung et al. found far smaller changes in the mean minutes of physical activity offered per week, ranging from −2.4 to 13 min (significance not reported) [38].

Three studies compared implementation strategies to a usual care or minimal support control on measures of lesson quality [26, 56, 60]. Perry et al. reported a significant increase of 14% relative to control, in the proportion of quality activities observed, relative to control in PE lessons following implementation support [56]. Significant improvements were also reported in physical activity program quality score in an Australian randomized trial by Sutherland et al. [60] but not in measures of quality of PE lessons in a more recent study by Bremer et al. [26] among schools receiving implementation support. Among studies that assessed changes in the implementation of a physical activity policy, practice, or program [27, 41, 60, 64], effects were modest with median effect sizes ranging from no change (–0.2%) in the study by Farmer et al. [41] to a change of almost 20% in the Australian randomized trial by Sutherland et al. [60].

DISCUSSION

This review aimed to examine the impact of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices, and programs to promote healthy eating, physical activity, or prevent obesity within school-based settings. Despite the substantial number of efficacious school-based behavioral interventions published in the last 10 years [13, 69], and the increase in implementation science research during the same period, this review only identified an additional eight studies since the publication of the original review in 2017 [25]. Collectively, from the newly included studies and the 22 studies included in the original review by Wolfenden et al. [25], most studies employed randomized controlled trial designs to test multicomponent implementation support strategies. Despite considerable heterogeneity in the effects of implementation strategies, the findings provide some evidence to support the effectiveness of strategies in enhancing the nutritional quality of foods served at schools [61], implementation of canteen nutrition policies [62], improvements in the time scheduled for PE [57], and the quality of PE lessons [54]. Such evidence could provide some guidance for school-based settings and jurisdictions seeking to implement recommendations within the WHO Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity Report [11] and the WHO Health Promoting Schools Framework [70].

The median effect size of the primary implementation outcomes reported in this review (16.5%, range 0.2% to 66.6%) are comparable with implementation efforts in other community settings. For example, in a recent review of implementation strategies to improve healthy eating and physical activity promoting policies and practices in childcare, the median effect size in the proportion of staff implementing a policy or practice was 11% (range 2.5 to 33%) [35]. Similarly, in a review of strategies to improve healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices in workplaces, the median effect size in the proportion of workplaces implementing a policy or practice was 13.4% (range 10.9%–39.6%) [36]. Effect sizes and range of effects reported across these reviews suggests that implementation strategies typically yield modest but highly variable improvements in implementation. Such findings indicate that while it is possible to result in large improvements (up to 66.6% in this instance) in the implementation of policies and practices, the effects of implementation strategies are likely dependent on context, the factors impeding implementation, and the extent to which the selected implementation strategies adequately address these. Research to better identify the most potent mix of implementation supports given barriers and context, therefore, should be a priority for future research in the field.

While limited, there is an accumulating body of evidence to suggest that implementation strategies have resulted in small improvements in the availability and provision of healthy foods in schools [40, 44, 52]. Given that food consumed at school contributes to an estimated 40% of a child’s daily energy intake [71], small improvements in consumption could lead to important improvement in public health nutrition. For example, studies modeling the impact of reductions in energy intake have found a small decrease in energy intake of 290 kJ per day could be sufficient in preventing excessive weight gain in children [72]. Several studies within the review found significant reductions in energy from fat [44, 48, 56] and total energy [59] provided by lunch meals, in magnitudes exceeding 200 kJ, that could make a meaningful contribution to such reductions. The potential benefit of such improvements, however, is maximized when implementation occurs at scale. Disappointingly, just 5 of the 30 studies included in this review (including three targeting implementation of nutrition interventions) examined the impact of implementation occurring “at scale,” defined as 50 or more schools [37, 43, 52, 56, 73]. Effects were mixed among these studies, with three reporting significant improvements in the majority of implementation outcomes [37, 52, 56], whilst the remaining two studies reporting no improvement [38, 43]. As the effects of interventions may attenuate when delivered on a larger scale, the potential benefit of strategies to improve population-wide implementation of school health initiatives remains uncertain.

LIMITATIONS

Substantial variation across included studies in the implementation strategies employed, policies, practices, and programs targeted and measures used to assess implementation resulted in considerable challenges during data synthesis and interpretation of findings. Studies tested a range of multicomponent implementation strategies, with only two studies testing the same combination [26, 38]. As such, the impact of specific implementation support strategies or combinations thereof were unable to be examined. In contrast to a similar review conducted within the childcare setting [35] where a number of studies used similar score-based measures of implementation, enabling the pooling of studies for meta-analysis, such homogeneity in outcomes and measures was not evident within this review. Due to this, synthesizing the data and drawing comparisons between outcomes within this review was difficult. Additionally, with 18 studies recruiting a sample of less than 30 schools, 19 studies using nonvalidated self-reported measures of implementation, and all but 2 studies assessed as high risk of bias in multiple domains, the true improvements in policy and practice implementation may be unable to be detected. Finally, a lack of consistent terminology and inadequate reporting of employed implementation strategies across studies is an important limitation of this review.

Despite best efforts from the authors, the review process was not without its limitations. A search of international implementation journals and a hand search of reference lists of included studies was not conducted, which may have identified additional eligible studies to contribute to the findings of this review. Finally, the review extracted a limited range of the many trial characteristics, outcomes, and other structural or contextual factors that may influence implementation. Greater extraction and reporting of a broader range of such characteristics would improve the external validity and utility of the findings by the end user. As such, future reviews should consider coding and reporting studies using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework [74, 75].

CONCLUSION

Despite the field of implementation science rapidly evolving and a considerable amount of research being conducted in the schools setting, a lack of strong and consistent evidence remains to support the selection of strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity, and obesity-prevention policies, practices, and programs. In the absence of clear evidence from empirical studies, researchers, and practitioners responsible for health promotion in school-based settings may have to rely on considerable formative research (e.g., consultation with schools to identify barriers and enablers) and theory to guide implementation. Future research calls for studies of high methodological quality using validated and consistent measures of implementation whilst adequately reporting employed implementation strategies using taxonomies, such as the EPOC [32] or Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change [76] taxonomies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions made by Debbie Booth in refining the search strategy and conducting the search. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the coauthors of the original review, Rebecca Wyse, Tessa Delaney, Alison Fielding, Flora Tzelepis, Tara Clinton-McHarg, Benjamin Parmenter, Peter Butler, John Wiggers, Adrian Bauman, Andrew Milat, and Christopher Williams.

Appendix A1

Summary of intervention, measures, and absolute intervention effect size in included studies

| Study | Targeted risk factor | Implementation strategies | Comparison | Primary implementation outcome and measures |

Effect size | Number of measures with significant result (p < .05) favoring the intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaimo et al. [43] | N | Clinical practice guidelines, educational materials, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, external funding, local consensus processes, tailored interventions | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous: Nutrition policy score and nutrition education and/or practice score (two measures) |

Median (range): 0.65 (0.2 to 1.1) |

0/2 |

| Cunningham- Sabo et al. [44] |

N | Clinical practice guidelines, educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing | Usual practice | Continuous: Nutrient content of school meals % of calories from fat breakfast/lunch (two measures) |

Median (range): −3% (−3.3% to −2.7%) |

1/2 |

| Delk et al. [46] | PA | Local consensus process, educational meetings, clinical practice guidelines, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, tailored interventions, other | Different implementation strategy |

Continuous: % of teachers that conducted activity breaks weekly (one measure, two comparisons) Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (two measures, four comparisons) |

Median (range): 13.3% (11.1% to 15.4%) Median (range): 26.5% (19.4% to 31.9%) |

6/6 |

| French et al. [47] | N | Local consensus processes, tailored intervention, educational meetings, pay for performance |

Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous % of program implementation (five measures) |

Median (range): 33% (11% to 41%) |

5/5 |

| Heath and Coleman [48] | N | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing | Usual practice | Continuous: % fat in school meal (two measures) Sodium of school meals (two measures) |

Median (range): −1.7% (−4.4% to 1%) Median (range): −29.5 (−48 to −11) |

1/4 |

| Hoelscher et al. [49] |

N/PA | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, pay for performance, other, the use of information and communication technology, local consensus process | Different implementation strategy |

Continuous: Mean number of lessons/or activities (five measures) Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (two measures) |

Median (range): 0.8 (−0.4 to 1. 2) Median (range): 4.4% (3.6% to 5.2%) |

4/7 |

| Lytle et al. [50] | N | Educational materials, educational meetings, local opinion leaders, local consensus processes | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Dichotomous: % of schools offering or selling targeted foods (four measures) |

Median (range): 8.5% (4% to 12%) |

2/4 |

| Mobley et al. [51] | N | Educational games, educational meetings, external funding, tailored intervention, educational materials, educational outreach or academic detailing, other, the use of information and communication technology |

Usual practice or waitlist control |

Dichotomous: % schools meeting various nutrition goals (12 measures) |

Median (range): 15.5% (0% to 88%) |

NR |

| Nathan et al. [52] | N | Educational materials, educational meetings, local consensus processes, local opinion leaders, other, monitoring the performance of the delivery of the healthcare, tailored interventions | Minimal support control |

Dichotomous: % Schools implementing a vegetable and fruit break (one measure) |

Mean difference (95% CI): 16.2% (5.6% to 26.8%) |

1/1 |

| Nathan et al. [53] | N | Audit and feedback, continuous quality improvement, education materials, education meeting, local consensus process, local opinion leader, tailored intervention, other | Usual practice | Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (two measures) |

Median (range): 35.5% (30.0% to 41.1%) |

2/2 |

| Naylor et al. [54] | PA | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach meetings or academic detailing, local consensus process, other, tailored interventions | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous: Minutes per week of physical activity implemented in the classroom (one measure, two comparisons) |

Median (range): 54.9 min (46.4 to 63.4) |

2/2 |

| Perry et al. [56] | N/PA | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, other | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous: % of kilocalories from fat in school lunch (one measure) Mean milligrams of sodium in lunches (one measure) Cholesterol milligrams in lunches (one measure) Quality of PE lesson % of seven activities observed (one measure) |

Mean difference (95%CI): −4.3% (−5.8% to −2.8%) Mean difference (95% CI): −100.5 (−167.6 to −33.4) Mean difference (95% CI): −8.3 (−16.7 to 0.1) Mean difference (95% CI): 14.3% (11.6% to 17.0%) |

3/4 |

| Perry et al. [55] | N | Educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, educational materials, local consensus processes, other | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous: % of program implementation (two measures) Mean number of fruit and vegetables available (two measures) |

Median (range): 14% (−2% to 30%) Median (range): 0.64 (0.48 to 0.80) |

2/4 |

| Sallis et al. [57] | PA | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, length of consultation, other | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous: Duration (minutes) per week of physical education lessons (one measure) Frequency (per week) of physical education lessons (one measures) |

Mean difference (95% CI): 26.6 (15.3 to 37.9) Mean difference (95% CI): 0.8 (0.3 to 1.3) |

2/2 |

| Saunders et al. [66] | PA | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, local consensus processes, local opinion leaders, other | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous: School level policy and practice related to physical activity (nine measures) |

N/A | NR |

| Simons- Morton et al. [59] |

N | Educational materials, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, local consensus processes, local opinion leaders, managerial supervision, monitoring of performance, other | Usual practice | Continuous: Macronutrient content of school meals (two measures) |

N/A | NR |

| Story et al. [58] | N | Educational meetings, other | Usual practice | Continuous: Mean number of fruit and vegetables available (two measures) % of guidelines implemented and % of promotions held (four measures) |

Median (range): 1.15 (1 to 1.3) Median (range): 38.4% (28.5% to 43.8%) |

6/6 |

| Sutherland et al. [60] | PA | Audit and feedback, education materials, education meeting, education outreach visits or academic detailing, local opinion leader, other | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (two measures) Continuous: Physical education lesson quality score (one measures) % of program implementation (four measures) |

Median (range): 19% (16% to 22%) Mean difference: 21.5 Median (range): −8% (−18% to 2%) |

0/2 1/1 0/4 |

| Whatley Blum et al. [61] | N | Clinical practice guidelines, educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, external funding, distribution of supplies, local consensus process, other | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous: % of food and beverage items meeting guideline nutrient and portion criteria (six measures) |

Median (range): 42.95% (15.7% to 60.6%) |

5/6 |

| Wolfenden et al. [62] | N | Audit and feedback, continuous quality improvement, external funding, education materials, education meeting, education outreach visits or academic detailing, local consensus process, local opinion leader, tailored intervention | Usual practice | Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (two measures) |

Median (range): 66.6% (60.5% to 72.6%) |

2/2 |

| Yoong et al. [63] | N | Audit and feedback, continuous quality improvement, education materials, tailored intervention | Usual practice | Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (two measures) |

Median (range): 21.6% (15.6% to 27.5%) |

0/2 |

| Young et al. [64] | PA | Education materials, education meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing, interprofessional education, local consensus processes, local opinion leaders | Usual practice | Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (seven measures) Continuous: Average number of physical activity programs taught (one measure) |

Median (range): 9.3% (−6.8% to 55.5%) Effect size (95% CI): 5.1 (−0.4 to 10.6) |

1/8 |

| New studies identified in this review | ||||||

| Bremer et al. [26] | PA | Educational meetings, educational materials | Usual practice | Continuous: Quantity of physical education lessons (one measure) |

Mean difference: t(27) = −0.23, |

0/1 |

| Cheung et al. [38] | PA | Educational meeting, educational materials | Usual practice | Continuous: Mean minutes of physical activity offered per week (three measures) |

Median (range): 5.7 (−2.4 to 13) |

NR |

| Egan et al. [39] |

PA | Educational materials; educational outreach visit or academic detailing, tailored intervention, audit, and feedback | Alternate intervention or usual practice | Continuous:Mean implementation score for components of movement integration (five measures) | Median (range): −2.79 (−4.92 to 3.66) |

NR |

| Evenhuis et al. [40] | N | Educational materials, educational meeting, audit with feedback, educational outreach visit or academic detailing | Educational materials | Continuous: Availability of healthier food products on display (one measure) Healthier product accessibility (one measure) |

Mean difference: 16.79 Mean difference: 9 |

NR |

| Farmer et al. [41] | PA | Incentives, local consensus approach, tailored interventions | Usual practice | Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (one measure) Continuous: Provision of play opportunities (one measure) |

Mean difference (95% CI): −0.20 (−11.46 to 11.06) Mean difference (95% CI): 4.50 (1.82 to 7.18) |

0/1 1/1 |

| Nathan, unpublished data | PA | Educational outreach visits, centralized technical support, mandate change, identify and prepare champions, provide ongoing consultation, educational material | Usual practice | Continuous: Mean minutes of teacher’s scheduled PA per day |

Mean difference (95% CI): 36.60 (2.68 to 70.51) | 1/1 |

| Taylor et al. [42] | N | Incentives, educational materials, educational outreach visits, or academic detailing | Usual practice or waitlist control |

Continuous: Quantity of fruit and vegetables available (two measures) |

Median (range): 1.23 (−0.79 to 3.26) |

NR |

| Waters et al. [27] | N/PA | Educational materials, educational outreach visits or academic detailing; local consensus approach, tailored interventions | Usual practice | Dichotomous: % implementing a variety of policies and practices (three measures) |

Median (range): 7% (−11.7% to 15%) |

NR |

CI confidence interval; N nutrition; NR not reported; PA physical activity.

Appendix A2

Search StrategyDatabase(s): Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub ahead of print, in-process and other nonindexed citations and daily 1946 to April 10, 2019 Search strategy:

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | schools/ | 34,641 |

| 2 | ((primary or elementary or middle or junior or high or secondary) adj (school* or student*)).mp. | 61,499 |

| 3 | kinder*.mp. | 22,544 |

| 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 | 106,292 |

| 5 | implement*.tw. | 427,155 |

| 6 | Health Promotion/mt [Methods] | 19,229 |

| 7 | “Outcome and Process Assessment (Health Care)”/ | 25,691 |

| 8 | “Process Assessment (Health Care)”/ | 4,389 |

| 9 | “Outcome Assessment (Health Care)”/ | 67,208 |

| 10 | Program Evaluation/ | 59,115 |

| 11 | Interrupted Time Series Analysis/ | 553 |

| 12 | dissemin*.tw. | 115,236 |

| 13 | adopt*.tw. | 220,568 |

| 14 | practice.tw. | 634,669 |

| 15 | organi?ational change*.tw. | 2,613 |

| 16 | diffus*.tw. | 353,856 |

| 17 | (system* adj2 change*).tw. | 15,325 |

| 18 | quality improvement*.tw. | 30,437 |

| 19 | transform*.tw. | 452,648 |

| 20 | translat*.tw. | 283,791 |

| 21 | transfer*.tw. | 594,534 |

| 22 | uptake*.tw. | 335,586 |

| 23 | sustainab*.tw. | 55,964 |

| 24 | institutionali*.tw. | 14,726 |

| 25 | routin*.tw. | 355,436 |

| 26 | maintenance.tw. | 254,465 |

| 27 | capacity.tw. | 460,913 |

| 28 | incorporat*.tw. | 395,520 |

| 29 | adher*.tw. | 172,945 |

| 30 | ((polic* or practice* or program* or innovation*) adj5 (performance or feedback or prompt* or reminder* or incentive* or penalt* or communicat* or social market* or professional development or network* or leadership or opinion leader* or consensus process* or change manage* or train* or audit*)).tw. | 103,076 |

| 31 | integrat*.tw. | 460,724 |

| 32 | scal* up.tw. | 16,615 |

| 33 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 | 4,833,658 |

| 34 | exp Obesity/ | 195,8011 |

| 35 | Weight Gain/ | 29,698 |

| 36 | exp Weight Loss/ | 38,540 |

| 37 | obes*.tw. | 269,101 |

| 38 | (weight gain or weight loss).tw. | 130,488 |

| 39 | (overweight or over weight or overeat* or over eat*).tw. | 64,358 |

| 40 | weight change*.tw. | 10,275 |

| 41 | ((bmi or body mass index) adj2 (gain or loss or change)).tw. | 4,130 |

| 42 | exp Primary Prevention/ | 143,568 |

| 43 | (primary prevention or secondary prevention).tw. | 30,738 |

| 44 | (preventive measure* or preventative measure*).tw. | 22,909 |

| 45 | (preventive care or preventative care).tw. | 5,038 |

| 46 | (obes* adj2 (prevent* or treat*)).tw. | 19,978 |

| 47 | 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 | 633,369 |

| 48 | exp Exercise/ | 176,978 |

| 49 | physical activity.tw. | 94,644 |

| 50 | physical inactivity.tw. | 6,883 |

| 51 | Motor Activity/ | 94,188 |

| 52 | (“physical education” or “physical training”).tw. | 9,495 |

| 53 | “Physical Education and Training”/ | 13,213 |

| 54 | Physical Fitness/ | 26,208 |

| 55 | sedentary.tw. | 27,694 |

| 56 | exp Life Style/ | 85,835 |

| 57 | exp Leisure Activities/ | 220,470 |

| 58 | Dancing/ | 2,669 |

| 59 | dancing.tw. | 1,576 |

| 60 | (exercise* adj aerobic*).tw. | 186 |

| 61 | sport*.tw. | 66,644 |

| 62 | ((lifestyle* or life style*) adj5 activ*).tw. | 6,082 |

| 63 | 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 | 547,175 |

| 64 | exp Diet/ | 261,598 |

| 65 | nutrition*.tw. | 248,427 |

| 66 | healthy eating.tw. | 5,898 |

| 67 | Child Nutrition Sciences/ | 1,075 |

| 68 | fruit*.tw. | 95,658 |

| 69 | vegetable*.tw. | 49,588 |

| 70 | “Fruit and Vegetable Juices”/ | 1,248 |

| 71 | canteen*.tw. | 589 |

| 72 | food service*.tw. | 1,810 |

| 73 | menu*.tw. | 4,561 |

| 74 | calorie*.tw. | 24,033 |

| 75 | Energy Intake/ | 38,728 |

| 76 | energy density.tw. | 8,494 |

| 77 | Eating/ | 50,500 |

| 78 | Feeding Behavior/ or feeding behavio?r*.tw. | 81,927 |

| 79 | dietary intake.tw. | 21,918 |

| 80 | Food Habits/ | 77,114 |

| 81 | Food/ | 31,390 |

| 82 | Carbonated Beverages/ or soft drink*.mp. | 5,116 |

| 83 | soda.tw. | 3,799 |

| 84 | sweetened drink*.tw. | 262 |

| 85 | Dietary Fats, Unsaturated/ or Dietary Fats/ | 51,350 |

| 86 | confectionar*.tw. | 240 |

| 87 | (school adj (lunch* or meal*)).tw. | 1,439 |

| 88 | menu plan*.tw. | 184 |

| 89 | ((feeding or food or nutrition*) adj program*).tw. | 4,133 |

| 90 | cafeteria*.tw. | 1,848 |

| 91 | Nutritional Status/ | 40,791 |

| 92 | 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74 or 75 or 76 or 77 or 78 or 79 or 80 or 81 or 82 or 83 or 84 or 85 or 86 or 87 or 88 or 89 or 90 or 91 | 741,173 |

| 93 | exp Smoking/ | 140,042 |

| 94 | exp “Tobacco Use Cessation”/ | 1,064 |

| 95 | smok*.tw. | 258,516 |

| 96 | Nicotine/ | 24,526 |

| 97 | Tobacco/ or “Tobacco Use”/ | 30,560 |

| 98 | ((ceas* or cess* or prevent* or stop* or quit* or abstin* or abstain* or reduc*) adj5 (smok* or tobacco or nicotine)).tw. | 51,511 |

| 99 | “Tobacco Use Disorder”/ | 10,617 |

| 100 | ex-smoker*.tw. | 3,769 |

| 101 | anti-smok*.tw. | 1,225 |

| 102 | 93 or 94 or 95 or 96 or 97 or 98 or 99 or 100 or 101 | 335,144 |

| 103 | alcohol drinking/ or binge drinking/ | 64,411 |

| 104 | alcohol*.tw. | 308,065 |

| 105 | Alcoholic Intoxication/ or Alcoholism/ | 82,939 |

| 106 | drink*.tw. | 128,749 |

| 107 | liquor*.tw. | 7,780 |

| 108 | beer*.tw. | 9,611 |

| 109 | wine*.tw. | 18,647 |

| 110 | spirit*.tw. | 24,880 |

| 111 | drunk*.tw. | 4,203 |

| 112 | intoxicat*.tw. | 44,075 |

| 113 | binge.tw. | 11,829 |

| 114 | 103 or 104 or 105 or 106 or 107 or 108 or 109 or 110 or 111 or 112 or 113 | 508,479 |

| 115 | 47 or 63 or 92 or 102 or 114 | 2,374,155 |

| 116 | Randomized Controlled Trial/ | 479,844 |

| 117 | clinical trial/ or controlled clinical trial/ | 537,645 |

| 118 | random allocation/ | 98,475 |

| 119 | Double-Blind Method/ | 150,664 |

| 120 | Single-Blind Method/ | 26,573 |

| 121 | placebos/ | 34,301 |

| 122 | Research Design/ | 100,656 |

| 123 | Evaluation Studies/ | 242,326 |

| 124 | Comparative Study/ | 1,826,707 |

| 125 | exp Longitudinal Studies/ | 1,22,430 |

| 126 | Cross-Over Studies/ | 45,007 |

| 127 | exp Cohort studies/ | 1,844,224 |

| 128 | Controlled Before-After Studies/ | 383 |

| 129 | Interrupted Time Series Analysis/ | 553 |

| 130 | comparative study.pt. | 1,826,707 |

| 131 | clinical trial.tw. | 125,184 |

| 132 | latin square.tw. | 4,495 |

| 133 | (time adj series).tw. | 26,782 |

| 134 | (before adj2 after adj3 (stud* or trial* or design*)).tw. | 12,708 |

| 135 | ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj5 (blind* or mark)).tw. | 160,930 |

| 136 | placebo*.tw. | 202,959 |

| 137 | random*.tw. | 1,038,274 |

| 138 | (matched adj (communit* or school* or population*)).tw. | 2,305 |

| 139 | control*.tw. | 3,546,542 |

| 140 | (comparison group* or control group*).tw. | 434,335 |

| 141 | matched pairs.tw. | 5,809 |

| 142 | outcome stud*.tw. | 7,564 |

| 143 | (qua?iexperimental or qua?i experimental or pseudo experimental).tw. | 11,696 |

| 144 | (nonrandomi?ed or non randomi?ed or psuedo randomi?ed or quasi randomi?ed).tw. | 26,473 |

| 145 | prospectiv*.tw. | 638,036 |

| 146 | volunteer*.tw. | 182,708 |

| 147 | 116 or 117 or 118 or 119 or 120 or 121 or 122 or 123 or 124 or 125 or 126 or 127 or 128 or 129 or 130 or 131 or 132 or 133 or 134 or 135 or 136 or 137 or 138 or 139 or 140 or 141 or 142 or 143 or 144 or 145 or 146 | 7,432,338 |

| 148 | exp adolescent/ or child/ | 2,671,427 |

| 149 | (child or children or adolescen* or teen*).tw. | 1,276,835 |

| 150 | 148 or 149 | 3,119,058 |

| 151 | 4 and 33 and 115 and 147 and 150 | 4,111 |

| 152 | limit 151 to ed=20160901-20190412 | 823 |

DATABASE(S): EMBASE 1947 TO PRESENT SEARCH STRATEGY:

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | schools/ | 63,598 |

| 2 | ((primary or elementary or middle or junior or high or secondary) adj (school* or student*)).mp. | 83,026 |

| 3 | kinder*.mp. | 32,382 |

| 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 | 166,381 |

| 5 | implement*.tw. | 557,138 |

| 6 | dissemin*.tw. | 158,810 |

| 7 | adopt*.tw. | 281,184 |

| 8 | practice.tw. | 870,432 |

| 9 | organi?ational change*.tw. | 3,193 |

| 10 | diffus*.tw. | 478,311 |

| 11 | system* change*.tw. | 8,902 |

| 12 | quality improvement*.tw. | 46,116 |

| 13 | transform*.tw. | 535,815 |

| 14 | translat*.tw. | 350,917 |

| 15 | transfer*.tw. | 714,912 |

| 16 | uptake*.tw. | 442,073 |

| 17 | sustainab*.tw. | 67,481 |

| 18 | institutionali*.tw. | 19,660 |

| 19 | routin*.tw. | 539,589 |

| 20 | maintenance.tw. | 351,213 |

| 21 | capacity.tw. | 602,641 |

| 22 | incorporat*.tw. | 494,048 |

| 23 | adher*.tw. | 252,374 |

| 24 | ((polic* or practice* or program* or innovation*) adj5 (performance or feedback or prompt* or reminder* or incentive* or penalt* or communicat* or social market* or professional development or network* or leadership or opinion leader* or consensus process* or change manage* or train* or audit*)).tw. | 141,527 |

| 25 | integrat*.tw. | 561,121 |

| 26 | scal* up.tw. | 20,866 |

| 27 | health care quality/ | 231,534 |

| 28 | quality control/ | 170,122 |

| 29 | program evaluation/ | 12,357 |

| 30 | total quality management/ | 55,032 |

| 31 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 | 6,381,792 |

| 32 | exp Obesity/ | 482,160 |

| 33 | Weight Gain/ | 91,702 |

| 34 | Weight Loss.tw. or exp weight reduction/ | 135,406 |

| 35 | obes*.tw. | 406,493 |

| 36 | (weight gain or weight loss).tw. | 200,827 |

| 37 | (overweight or over weight or overeat* or over eat*).tw. | 97,808 |

| 38 | weight change*.tw. | 15,239 |

| 39 | ((bmi or body mass index) adj2 (gain or loss or change)).tw. | 6,986 |

| 40 | exp Primary Prevention/ | 37,972 |

| 41 | (primary prevention or secondary prevention).tw. | 46,930 |

| 42 | (preventive measure* or preventative measure*).tw. | 32,787 |

| 43 | (preventive care or preventative care).tw. | 6,298 |

| 44 | (obes* adj2 (prevent* or treat*)).tw. | 28,499 |

| 45 | 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 | 850,700 |

| 46 | exp Exercise/ | 336,319 |

| 47 | physical activity.tw. or exp physical activity/ | 433,582 |

| 48 | physical inactivity.tw. | 9,388 |

| 49 | exp Motor Activity/ | 536,018 |

| 50 | (“physical education” or “physical training”).tw. | 13,789 |

| 51 | physical education/ | 13,316 |

| 52 | physical fitness.tw. or fitness/ | 41,592 |

| 53 | sedentary.tw. | 37,170 |

| 54 | lifestyle/ | 104,759 |

| 55 | Leisure Activit*.tw. or leisure/ | 34,038 |

| 56 | exp Sports/ | 157,505 |

| 57 | Dancing/ | 4,479 |

| 58 | (dance* or dancing).tw. | 8,367 |

| 59 | (exercise* adj2 aerobic*).tw. | 12,926 |

| 60 | sport*.tw. | 91,539 |

| 61 | ((lifestyle* or life style*) adj5 activ*).tw. | 8,789 |

| 62 | 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 | 1,385,883 |

| 63 | exp Diet/ | 340,795 |

| 64 | nutrition*.tw. or nutrition/ | 386,929 |

| 65 | (health* adj2 eat*).tw. | 10,407 |

| 66 | nutritional science/ | 5,719 |

| 67 | fruit*.mp. or fruit/ or “fruit and vegetable juice”/ | 143,342 |

| 68 | vegetable*.tw. or vegetable/ | 76,624 |

| 69 | canteen*.tw. | 978 |

| 70 | Food Services.tw. or catering service/ | 18,558 |

| 71 | menu*.tw. | 5,961 |

| 72 | (calorie or calories or kilojoule*).tw. | 36,880 |

| 73 | Energy Intake.tw. or caloric intake/ | 64,139 |

| 74 | energy density.tw. | 6,365 |

| 75 | Eating/ | 35,119 |

| 76 | Feeding Behavior/ or feeding behavio?r*.tw. | 86,486 |

| 77 | dietary intake.tw. or dietary intake/ | 86,822 |

| 78 | Food Habits/ | 67,209 |

| 79 | Food/ | 91,993 |

| 80 | Carbonated Beverages/ or soft drink*.mp. | 6,974 |

| 81 | soda.tw. | 5,149 |

| 82 | sweetened drink*.tw. | 360 |

| 83 | Dietary Fats, Unsaturated/ or Dietary Fats/ | 48,641 |

| 84 | confectionar*.tw. | 341 |

| 85 | (school adj (lunch* or meal*)).tw. | 1,836 |

| 86 | ((feeding or food or nutrition*) adj program*).tw. | 5,015 |

| 87 | cafeteria*.tw. | 2,308 |

| 88 | Nutritional Status/ | 62,601 |

| 89 | 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74 or 75 or 76 or 77 or 78 or 79 or 80 or 81 or 82 or 83 or 84 or 85 or 86 or 87 or 88 | 1,089,562 |

| 90 | exp Smoking/ | 368,685 |

| 91 | exp “Tobacco Use Cessation”/ | 54,469 |

| 92 | smok*.tw. | 382,866 |

| 93 | Nicotine/ | 47,085 |

| 94 | Tobacco/ or “Tobacco Use”/ | 54,004 |

| 95 | ((ceas* or cess* or prevent* or stop* or quit* or abstin* or abstain* or reduc*) adj5 (smok* or tobacco or nicotine)).tw. | 66,147 |

| 96 | “Tobacco Use Disorder”/ | 7,394 |

| 97 | ex-smoker*.tw. | 6,694 |

| 98 | anti-smok*.tw. | 1,588 |

| 99 | 90 or 91 or 92 or 93 or 94 or 95 or 96 or 97 or 98 | 545,883 |

| 100 | alcohol drinking/ or binge drinking/ | 40,705 |

| 101 | alcohol*.tw. | 442,943 |

| 102 | Alcoholic Intoxication/ or Alcoholism/ | 133,150 |

| 103 | drink*.tw. | 178,445 |

| 104 | liquor*.tw. | 12,281 |

| 105 | beer*.tw. | 13,964 |

| 106 | wine*.tw. | 23,346 |

| 107 | spirit*.tw. | 32,568 |

| 108 | drunk*.tw. | 6,026 |

| 109 | intoxicat*.tw. | 66,687 |

| 110 | binge.tw. | 16,608 |

| 111 | 100 or 101 or 102 or 103 or 104 or 105 or 106 or 107 or 108 or 109 or 110 | 716,291 |

| 112 | 45 or 62 or 89 or 99 or 111 | 3,879,229 |

| 113 | Randomized Controlled Trial/ | 544,426 |

| 114 | clinical trial/ or controlled clinical trial/ | 1,037,260 |

| 115 | random allocation/ | 78,229 |

| 116 | Double-Blind Method/ | 126,778 |

| 117 | Single-Blind Method/ | 32,642 |

| 118 | placebos/ | 285,441 |

| 119 | Research Design/ | 1,626,031 |

| 120 | Intervention Studies/ | 31,912 |

| 121 | Evaluation Studies/ | 38,259 |

| 122 | Comparative Study/ | 835,481 |

| 123 | exp Longitudinal Studies/ | 124,566 |

| 124 | Cross-Over Studies/ | 48,369 |

| 125 | clinical trial.tw. | 183,772 |

| 126 | latin square.tw. | 4,848 |

| 127 | (time adj series).tw. | 30,180 |

| 128 | (before adj2 after adj3 (stud* or trial* or design*)).tw. | 17,774 |

| 129 | ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj5 (blind* or mark)).tw. | 226,356 |

| 130 | placebo*.tw. | 291,972 |

| 131 | random*.tw. | 1,404,881 |

| 132 | (matched adj (communit* or school* or population*)).tw. | 3,301 |

| 133 | control*.tw. | 4,744,140 |

| 134 | (qua?iexperimental or qua?i experimental or pseudo experimental).tw. | 14,109 |

| 135 | (nonrandomi?ed or non randomi?ed or psuedo randomi?ed or quasi randomi?ed).tw. | 35,465 |

| 136 | prospectiv*.tw. | 970,850 |

| 137 | volunteer*.tw. | 248,636 |

| 138 | cohort analysis/ or cohort studies/ | 452,474 |

| 139 | 113 or 114 or 115 or 116 or 117 or 118 or 119 or 120 or 121 or 122 or 123 or 124 or 125 or 126 or 127 or 128 or 129 or 130 or 131 or 132 or 133 or 134 or 135 or 136 or 137 or 138 | 9,238,197 |

| 140 | school child/ | 343,648 |

| 141 | adolescent/ | 1,559,797 |

| 142 | (child or children or adolescen* or teen*).tw. | 1,768,364 |

| 143 | 140 or 141 or 142 | 2,887,338 |

| 144 | 4 and 31 and 112 and 139 and 143 | 4,962 |

| 145 | limit 144 to dd=20160901-20190412 | 688 |

DATABASE(S): PSYCINFO 1806 TO APRIL WEEK 2 2019 SEARCH STRATEGY:

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | schools/ | 28,501 |

| 2 | ((primary or elementary or middle or junior or high or secondary) adj (school* or student*)).mp. | 187,658 |

| 3 | kinder*.mp. | 25,418 |

| 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 | 229,493 |

| 5 | implement*.tw. | 162,915 |

| 6 | Dissemin*.tw. | 10,234 |

| 7 | adopt*.tw. | 87,104 |

| 8 | practice.tw. | 316,893 |

| 9 | organi?ational change*.tw. | 7,087 |

| 10 | diffus*.tw. | 28,195 |

| 11 | system* change*.tw. | 3,736 |

| 12 | quality improvement*.tw. | 4,661 |

| 13 | transform*.tw. | 73,504 |

| 14 | translat*.tw. | 53,620 |

| 15 | transfer*.tw. | 69,749 |

| 16 | uptake*.tw. | 14,796 |

| 17 | sustainab*.tw. | 18,291 |

| 18 | institutionali*.tw. | 16,494 |

| 19 | routin*.tw. | 44,817 |

| 20 | maintenance.tw. | 57,427 |

| 21 | capacity.tw. | 77,478 |

| 22 | incorporat*.tw. | 78,384 |

| 23 | adher*.tw. | 34,556 |

| 24 | ((polic* or practice* or program* or innovation*) adj5 (performance or feedback or prompt* or reminder* or incentive* or penalt* or communicat* or social market* or professional development or network* or leadership or opinion leader* or consensus process* or change manage* or train* or audit*)).tw. | 87,456 |

| 25 | integrat*.tw. | 216,469 |

| 26 | scal* up.tw. | 1,994 |

| 27 | Quality Control/ | 1,438 |

| 28 | quality of services/ | 6,031 |

| 29 | program evaluation/ | 12,201 |

| 30 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 | 1,137,067 |

| 31 | exp Obesity/ | 22,903 |

| 32 | Weight Gain/ | 2,925 |

| 33 | exp Weight Loss/ | 3,426 |

| 34 | obes*.tw. | 38,244 |

| 35 | (weight gain or weight loss).tw. | 19,875 |

| 36 | (overweight or over weight or overeat* or over eat*).tw. | 16,413 |

| 37 | weight change*.tw. | 2,122 |

| 38 | ((bmi or body mass index) adj2 (gain or loss or change)).tw. | 764 |

| 39 | (primary prevention or secondary prevention).tw. | 5,844 |

| 40 | (preventive measure* or preventative measure*).tw. | 2,815 |

| 41 | (preventive care or preventative care).tw. | 1,198 |

| 42 | (obes* adj2 (prevent* or treat*)).tw. | 4,884 |

| 43 | 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 | 65,396 |

| 44 | exp Exercise/ | 24,563 |

| 45 | physical activity.tw. | 31,222 |

| 46 | physical inactivity.tw. | 1,843 |

| 47 | (“physical education” or “physical training”).tw. | 6,220 |

| 48 | Physical Fitness/ | 4,077 |

| 49 | sedentary.tw. | 6,296 |

| 50 | exp Sports/ | 24,756 |

| 51 | Dance/ | 2,120 |

| 52 | (dance* or dancing).tw. | 7,867 |

| 53 | (exercise* adj2 aerobic*).tw. | 2,033 |

| 54 | sport*.tw. | 33,287 |

| 55 | ((lifestyle* or life style*) adj5 activ*).tw. | 2,255 |

| 56 | 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 | 98,946 |

| 57 | nutrition*.tw. | 24,725 |

| 58 | (health* adj2 eat*).tw. | 3,701 |

| 59 | fruit*.tw. | 17,266 |

| 60 | vegetable*.tw. | 5,508 |

| 61 | canteen*.tw. | 132 |

| 62 | food service*.tw. | 521 |

| 63 | (diet* or food habits or fat or menu*).tw. | 51,336 |

| 64 | (calorie or calories or kilojoule*).tw. | 3,936 |

| 65 | Food Intake/ | 14,041 |

| 66 | energy density.tw. | 300 |

| 67 | Eating/ | 11,764 |

| 68 | Feeding Behavior/ or feeding behavio?r*.mp. | 11,191 |

| 69 | dietary intake.tw. | 2,104 |

| 70 | Food/ | 13,443 |

| 71 | Carbonated Beverages/ or soft drink*.mp. | 684 |

| 72 | soda.tw. | 418 |

| 73 | sweetened drink*.tw. | 52 |

| 74 | confectionar*.tw. | 40 |

| 75 | (school adj (lunch* or meal*)).tw. | 538 |

| 76 | ((feeding or food or nutrition*) adj program*).tw. | 988 |

| 77 | cafeteria*.tw. | 720 |

| 78 | 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74 or 75 or 76 or 77 | 114,688 |

| 79 | smok*.tw. | 52,934 |

| 80 | Nicotine/ | 10,600 |

| 81 | Tobacco smoking/ | 29,571 |

| 82 | ((ceas* or cess* or prevent* or stop* or quit* or abstin* or abstain* or reduc*) adj5 (smok* or tobacco or nicotine)).tw. | 22,093 |

| 83 | “Tobacco Use Disorder”/ | 198 |

| 84 | ex-smoker*.tw. | 712 |

| 85 | anti-smok*.tw. | 540 |

| 86 | 79 or 80 or 81 or 82 or 83 or 84 or 85 | 60,113 |

| 87 | alcohol drinking/ or binge drinking/ | 2,226 |

| 88 | alcohol*.tw. | 125,592 |

| 89 | Alcoholic Intoxication/ or Alcoholism/ | 29,153 |

| 90 | drink*.tw. | 50,966 |

| 91 | liquor*.tw. | 890 |

| 92 | beer*.tw. | 2,708 |

| 93 | wine*.tw. | 2,634 |

| 94 | spirit*.tw. | 47,011 |

| 95 | drunk*.tw. | 3,653 |

| 96 | intoxicat*.tw. | 9,133 |

| 97 | binge.tw. | 11,559 |

| 98 | 87 or 88 or 89 or 90 or 91 or 92 or 93 or 94 or 95 or 96 or 97 | 200,599 |

| 99 | 43 or 56 or 78 or 86 or 98 | 458,108 |

| 100 | clinical trial/ or controlled clinical trial/ | 11,288 |

| 101 | placebo/ | 5,228 |

| 102 | Research Design/ | 10,996 |

| 103 | Intervention/ | 58,664 |

| 104 | exp Longitudinal Studies/ | 16,128 |

| 105 | ((Cross-Over or evaluation or comparative) adj Stud*).tw. | 17,808 |

| 106 | clinical trial.tw. | 13,637 |

| 107 | latin square.tw. | 493 |

| 108 | (time adj series).tw. | 7,680 |

| 109 | (before adj2 after adj3 (stud* or trial* or design*)).tw. | 2,286 |

| 110 | ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj5 (blind* or mark)).tw. | 24,988 |

| 111 | placebo*.tw. | 38,937 |

| 112 | random*.tw. | 187,356 |

| 113 | (matched adj (communit* or school* or population*)).tw. | 424 |

| 114 | control*.tw. | 658,383 |

| 115 | comparison group*.tw. | 12,778 |

| 116 | matched pairs.tw. | 1,272 |

| 117 | outcome stud*.tw. | 4,759 |

| 118 | (qua?iexperimental or qua?i experimental or pseudo experimental).tw. | 10,839 |

| 119 | (nonrandomi?ed or non randomi?ed or psuedo randomi?ed or quasi randomi?ed).tw. | 2,226 |

| 120 | prospectiv*.tw. | 64,156 |

| 121 | volunteer*.tw. | 37,238 |

| 122 | 100 or 101 or 102 or 103 or 104 or 105 or 106 or 107 or 108 or 109 or 110 or 111 or 112 or 113 or 114 or 115 or 116 or 117 or 118 or 119 or 120 or 121 | 945,144 |

| 123 | (child or children or adolescen* or teen*).tw. | 754,758 |

| 124 | 4 and 30 and 99 and 122 and 123 | 1,049 |

| 125 | limit 124 to up=20160901-20190412 | 184 |

CUMULATIVE INDEX TO NURSING AND ALLIED HEALTH LITERATURE

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Schools”) OR (MH “Schools, Elementary”) OR (MH “Schools, Middle”) OR (MH “Schools, Secondary”) | 20,192 |

| S2 | ((primary or elementary or middle or junior or high or secondary) n1 (school* or student*)) | 42,756 |

| S3 | kinder* | 3,121 |

| S4 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 | 54,176 |

| S5 | implement* | 163,174 |

| S6 | dissemin* | 19,963 |

| S7 | adopt* | 54,029 |

| S8 | ((polic* or practice* or program* or innovation*) n5 (performance or feedback or prompt* or reminder* or incentive* or penalt* or communicat* or “social market*” or “professional development” or network* or leadership or “opinion leader*” or “consensus process*” or “change manage*” or train* or audit*)) | 60,829 |

| S9 | “organi?ational change*” | 12,260 |

| S10 | diffus* | 40,947 |

| S11 | “system* change*” | 2,038 |

| S12 | “quality improvement*” | 52,948 |

| S13 | transform* | 37,570 |

| S14 | translat* | 47,031 |

| S15 | transfer* | 68,493 |

| S16 | uptake* | 33,290 |

| S17 | sustainab* | 15,336 |

| S18 | institutionali* | 7,551 |

| S19 | routin* | 77,827 |

| S20 | maintenance | 45,478 |

| S21 | capacity | 61,690 |

| S22 | incorporat* | 52,472 |

| S23 | adher* | 55,246 |

| S24 | practice | 565,324 |

| S25 | integrat* | 108,963 |

| S26 | “scal* up” | 3,043 |

| S27 | S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 | 1,209,243 |

| S28 | (MH “Obesity+”) | 84,796 |

| S29 | (MH “Weight Gain”) | 10,596 |

| S30 | (MH “Weight Loss”) | 18,829 |

| S31 | obes* | 113,508 |

| S32 | (“weight gain” or “weight loss”) | 45,507 |

| S33 | (overweight or “over weight” or overeat* or “over eat*”) | 26,427 |

| S34 | “weight change*” | 3,356 |

| S35 | ((bmi or body mass index) n2 (gain or loss or change)) | 2,901 |

| S36 | “Primary Prevention” | 5,678 |

| S37 | “secondary prevention” | 5,003 |

| S38 | “preventive measure*” | 4,270 |

| S39 | “preventative measure*” | 753 |

| S40 | “preventive care” or “preventative care” | 2,585 |

| S41 | (obes* n2 (prevent* or treat*)) | 18,976 |

| S42 | S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 | 162,511 |

| S43 | (MH “Exercise+”) | 98,166 |