Abstract

A cornerstone of theoretical neuroscience is the circuit model: a system of equations that captures a hypothesized neural mechanism. Such models are valuable when they give rise to an experimentally observed phenomenon -- whether behavioral or a pattern of neural activity -- and thus can offer insights into neural computation. The operation of these circuits, like all models, critically depends on the choice of model parameters. A key step is then to identify the model parameters consistent with observed phenomena: to solve the inverse problem. In this work, we present a novel technique, emergent property inference (EPI), that brings the modern probabilistic modeling toolkit to theoretical neuroscience. When theorizing circuit models, theoreticians predominantly focus on reproducing computational properties rather than a particular dataset. Our method uses deep neural networks to learn parameter distributions with these computational properties. This methodology is introduced through a motivational example of parameter inference in the stomatogastric ganglion. EPI is then shown to allow precise control over the behavior of inferred parameters and to scale in parameter dimension better than alternative techniques. In the remainder of this work, we present novel theoretical findings in models of primary visual cortex and superior colliculus, which were gained through the examination of complex parametric structure captured by EPI. Beyond its scientific contribution, this work illustrates the variety of analyses possible once deep learning is harnessed towards solving theoretical inverse problems.

Research organism: None

Introduction

The fundamental practice of theoretical neuroscience is to use a mathematical model to understand neural computation, whether that computation enables perception, action, or some intermediate processing. A neural circuit is systematized with a set of equations – the model – and these equations are motivated by biophysics, neurophysiology, and other conceptual considerations (Kopell and Ermentrout, 1988; Marder, 1998; Abbott, 2008; Wang, 2010; O'Leary et al., 2015). The function of this system is governed by the choice of model parameters, which when configured in a particular way, give rise to a measurable signature of a computation. The work of analyzing a model then requires solving the inverse problem: given a computation of interest, how can we reason about the distribution of parameters that give rise to it? The inverse problem is crucial for reasoning about likely parameter values, uniquenesses and degeneracies, and predictions made by the model (Gutenkunst et al., 2007; Erguler and Stumpf, 2011; Mannakee et al., 2016).

Ideally, one carefully designs a model and analytically derives how computational properties determine model parameters. Seminal examples of this gold standard include our field’s understanding of memory capacity in associative neural networks (Hopfield, 1982), chaos and autocorrelation timescales in random neural networks (Sompolinsky et al., 1988), central pattern generation (Olypher and Calabrese, 2007), the paradoxical effect (Tsodyks et al., 1997), and decision making (Wong and Wang, 2006). Unfortunately, as circuit models include more biological realism, theory via analytical derivation becomes intractable. Absent this analysis, statistical inference offers a toolkit by which to solve the inverse problem by identifying, at least approximately, the distribution of parameters that produce computations in a biologically realistic model (Foster et al., 1993; Prinz et al., 2004; Achard and De Schutter, 2006; Fisher et al., 2013; O'Leary et al., 2014; Alonso and Marder, 2019).

Statistical inference, of course, requires quantification of the sometimes vague term computation. In neuroscience, two perspectives are dominant. First, often we directly use an exemplar dataset: a collection of samples that express the computation of interest, this data being gathered either experimentally in the lab or from a computer simulation. Although a natural choice given its connection to experiment (Paninski and Cunningham, 2018), some drawbacks exist: these data are well known to have features irrelevant to the computation of interest (Niell and Stryker, 2010; Saleem et al., 2013; Musall et al., 2019), confounding inferences made on such data. Related to this point, use of a conventional dataset encourages conventional data likelihoods or loss functions, which focus on some global metric like squared error or marginal evidence, rather than the computation itself.

Alternatively, researchers often quantify an emergent property (EP): a statistic of data that directly quantifies the computation of interest, wherein the dataset is implicit. While such a choice may seem esoteric, it is not: the above ‘gold standard’ examples (Hopfield, 1982; Sompolinsky et al., 1988; Olypher and Calabrese, 2007; Tsodyks et al., 1997; Wong and Wang, 2006) all quantify and focus on some derived feature of the data, rather than the data drawn from the model. An emergent property is of course a dataset by another name, but it suggests different approach to solving the same inverse problem: here, we directly specify the desired emergent property – a statistic of data drawn from the model – and the value we wish that property to have, and we set up an optimization program to find the distribution of parameters that produce this computation. This statistical framework is not new: it is intimately connected to the literature on approximate bayesian computation (Beaumont et al., 2002; Marjoram et al., 2003; Sisson et al., 2007), parameter sensitivity analyses (Raue et al., 2009; Karlsson et al., 2012; Hines et al., 2014; Raman et al., 2017), maximum entropy modeling (Elsayed and Cunningham, 2017; Savin and Tkačik, 2017; Młynarski et al., 2020), and approximate bayesian inference (Tran et al., 2017; Gonçalves et al., 2019); we detail these connections in Section 'Related approaches'.

The parameter distributions producing a computation may be curved or multimodal along various parameter axes and combinations. It is by quantifying this complex structure that emergent property inference offers scientific insight. Traditional approximation families (e.g. mean-field or mixture of gaussians) are limited in the distributional structure they may learn. To address such restrictions on expressivity, advances in machine learning have used deep probability distributions as flexible approximating families for such complicated distributions (Rezende and Mohamed, 2015; Papamakarios et al., 2019a) (see Section 'Deep probability distributions and normalizing flows'). However, the adaptation of deep probability distributions to the problem of theoretical circuit analysis requires recent developments in deep learning for constrained optimization (Loaiza-Ganem et al., 2017), and architectural choices for efficient and expressive deep generative modeling (Dinh et al., 2017; Kingma and Dhariwal, 2018). We detail our method, which we call emergent property inference (EPI) in Section 'Emergent property inference via deep generative models'.

Equipped with this method, we demonstrate the capabilities of EPI and present novel theoretical findings from its analysis. First, we show EPI’s ability to handle biologically realistic circuit models using a five-neuron model of the stomatogastric ganglion (Gutierrez et al., 2013): a neural circuit whose parametric degeneracy is closely studied (Goldman et al., 2001). Then, we show EPI’s scalability to high dimensional parameter distributions by inferring connectivities of recurrent neural networks that exhibit stable, yet amplified responses – a hallmark of neural responses throughout the brain (Murphy and Miller, 2009; Hennequin et al., 2014; Bondanelli et al., 2019). In a model of primary visual cortex (Litwin-Kumar et al., 2016; Palmigiano et al., 2020), EPI reveals how the recurrent processing across different neuron-type populations shapes excitatory variability: a finding that we show is analytically intractable. Finally, we investigated the possible connectivities of a superior colliculus model that allow execution of different tasks on interleaved trials (Duan et al., 2021). EPI discovered a rich distribution containing two connectivity regimes with different solution classes. We queried the deep probability distribution learned by EPI to produce a mechanistic understanding of neural responses in each regime. Intriguingly, the inferred connectivities of each regime reproduced results from optogenetic inactivation experiments in markedly different ways. These theoretical insights afforded by EPI illustrate the value of deep inference for the interrogation of neural circuit models.

Results

Motivating emergent property inference of theoretical models

Consideration of the typical workflow of theoretical modeling clarifies the need for emergent property inference. First, one designs or chooses an existing circuit model that, it is hypothesized, captures the computation of interest. To ground this process in a well-known example, consider the stomatogastric ganglion (STG) of crustaceans, a small neural circuit which generates multiple rhythmic muscle activation patterns for digestion (Marder and Thirumalai, 2002). Despite full knowledge of STG connectivity and a precise characterization of its rhythmic pattern generation, biophysical models of the STG have complicated relationships between circuit parameters and computation (Goldman et al., 2001; Prinz et al., 2004).

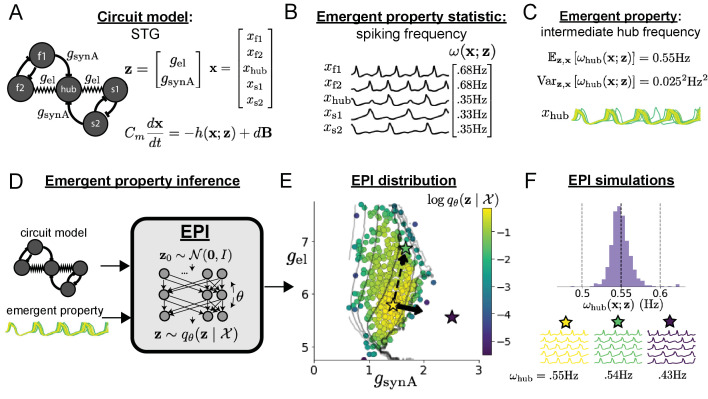

A subcircuit model of the STG (Gutierrez et al., 2013) is shown schematically in Figure 1A. The fast population (f1 and f2) represents the subnetwork generating the pyloric rhythm and the slow population (s1 and s2) represents the subnetwork of the gastric mill rhythm. The two fast neurons mutually inhibit one another, and spike at a greater frequency than the mutually inhibiting slow neurons. The hub neuron couples with either the fast or slow population, or both depending on modulatory conditions. The jagged connections indicate electrical coupling having electrical conductance , smooth connections in the diagram are inhibitory synaptic projections having strength onto the hub neuron, and nS for mutual inhibitory connections. Note that the behavior of this model will be critically dependent on its parameterization – the choices of conductance parameters .

Figure 1. Emergent property inference in the stomatogastric ganglion.

(A) Conductance-based subcircuit model of the STG. (B) Spiking frequency is an emergent property statistic. Simulated at nS and nS. (C) The emergent property of intermediate hub frequency. Simulated activity traces are colored by log probability of generating parameters in the EPI distribution (Panel E). (D) For a choice of circuit model and emergent property, EPI learns a deep probability distribution of parameters . (E) The EPI distribution producing intermediate hub frequency. Samples are colored by log probability density. Contours of hub neuron frequency error are shown at levels of 0.525, 0.53, … 0.575 Hz (dark to light gray away from mean). Dimension of sensitivity (solid arrow) and robustness (dashed arrow). (F) (Top) The predictions of the EPI distribution. The black and gray dashed lines show the mean and two standard deviations according the emergent property. (Bottom) Simulations at the starred parameter values.

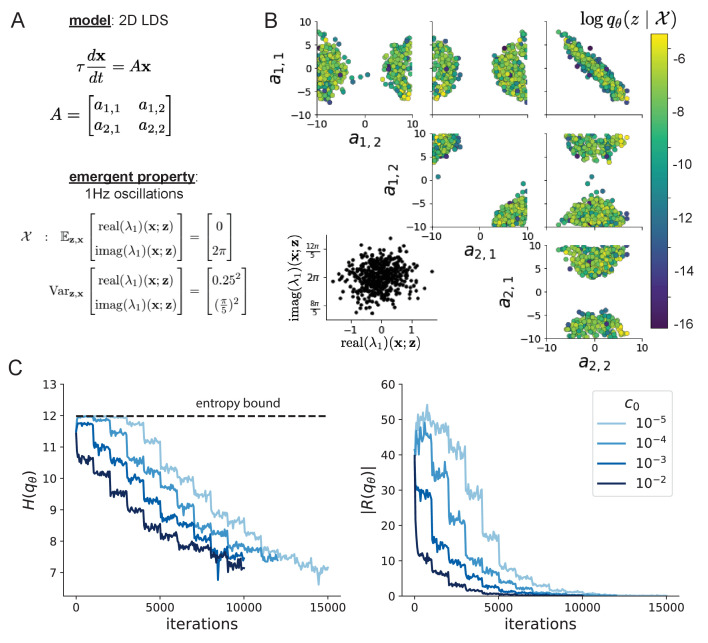

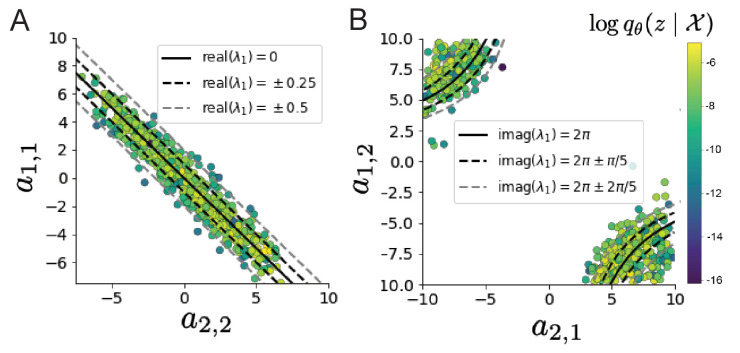

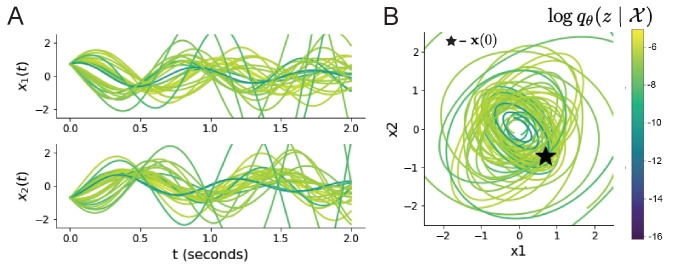

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Emergent property inference in a 2D linear dynamical system.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Analytic contours of inferred EPI distribution.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Sampled dynamical systems and their simulated activity from colored by log probability.

Figure 1—figure supplement 4. EPI optimization of the STG model producing network syncing.

Second, once the model is selected, one must specify what the model should produce. In this STG model, we are concerned with neural spiking frequency, which emerges from the dynamics of the circuit model (Figure 1B). An emergent property studied by Gutierrez et al. is the hub neuron firing at an intermediate frequency between the intrinsic spiking rates of the fast and slow populations. This emergent property (EP) is shown in Figure 1C at an average frequency of 0.55 Hz. To be precise, we define intermediate hub frequency not strictly as 0.55 Hz, but frequencies of moderate deviation from 0.55 Hz between the fast (.35Hz) and slow (.68Hz) frequencies.

Third, the model parameters producing the emergent property are inferred. By precisely quantifying the emergent property of interest as a statistical feature of the model, we use emergent property inference (EPI) to condition directly on this emergent property. Before presenting technical details (in the following section), let us understand emergent property inference schematically. EPI (Figure 1D) takes, as input, the model and the specified emergent property, and as its output, returns the parameter distribution (Figure 1E). This distribution – represented for clarity as samples from the distribution – is a parameter distribution constrained such that the circuit model produces the emergent property. Once EPI is run, the returned distribution can be used to efficiently generate additional parameter samples. Most importantly, the inferred distribution can be efficiently queried to quantify the parametric structure that it captures. By quantifying the parametric structure governing the emergent property, EPI informs the central question of this inverse problem: what aspects or combinations of model parameters have the desired emergent property?

Emergent property inference via deep generative models

EPI formalizes the three-step procedure of the previous section with deep probability distributions (Rezende and Mohamed, 2015; Papamakarios et al., 2019a). First, as is typical, we consider the model as a coupled set of noisy differential equations. In this STG example, the model activity (or state) is the membrane potential for each neuron, which evolves according to the biophysical conductance-based equation:

| (1) |

where = 1nF, and is a sum of the leak, calcium, potassium, hyperpolarization, electrical, and synaptic currents, all of which have their own complicated dependence on activity and parameters , and is white gaussian noise (Gutierrez et al., 2013; see Section 'STG model' for more detail).

Second, we determine that our model should produce the emergent property of ‘intermediate hub frequency’ (Figure 1C). We stipulate that the hub neuron’s spiking frequency – denoted by statistic – is close to a frequency of 0.55 Hz, between that of the slow and fast frequencies. Mathematically, we define this emergent property with two constraints: that the mean hub frequency is 0.55 Hz,

| (2) |

and that the variance of the hub frequency is moderate

| (3) |

In the emergent property of intermediate hub frequency, the statistic of hub neuron frequency is an expectation over the distribution of parameters and the distribution of the data that those parameters produce. We define the emergent property as the collection of these two constraints. In general, an emergent property is a collection of constraints on statistical moments that together define the computation of interest.

Third, we perform emergent property inference: we find a distribution over parameter configurations of models that produce the emergent property; in other words, they satisfy the constraints introduced in Equations 2 and 3. This distribution will be chosen from a family of probability distributions , defined by a deep neural network (Rezende and Mohamed, 2015; Papamakarios et al., 2019a; Figure 1D, EPI box). Deep probability distributions map a simple random variable (e.g. an isotropic gaussian) through a deep neural network with weights and biases to parameters of a suitably complicated distribution (see Section 'Deep probability distributions and normalizing flows' for more details). Many distributions in will respect the emergent property constraints, so we select the most random (highest entropy) distribution, which also means this approach is equivalent to bayesian variational inference (see Section 'EPI as variational inference'). In EPI optimization, stochastic gradient steps in are taken such that entropy is maximized, and the emergent property is produced (see Section 'Emergent property inference (EPI)'). We then denote the inferred EPI distribution as , since the structure of the learned parameter distribution is determined by weights and biases , and this distribution is conditioned upon emergent property .

The structure of the inferred parameter distributions of EPI can be analyzed to reveal key information about how the circuit model produces the emergent property. As probability in the EPI distribution decreases away from the mode of (Figure 1E yellow star), the emergent property deteriorates. Perturbing along a dimension in which changes little will not disturb the emergent property, making this parameter combination robust with respect to the emergent property. In contrast, if is perturbed along a dimension with strongly decreasing , that parameter combination is deemed sensitive (Raue et al., 2009; Raman et al., 2017). By querying the second-order derivative (Hessian) of at a mode, we can quantitatively identify how sensitive (or robust) each eigenvector is by its eigenvalue; the more negative, the more sensitive and the closer to zero, the more robust (see Section 'Hessian sensitivity vectors'). Indeed, samples equidistant from the mode along these dimensions of sensitivity (, smaller eigenvalue) and robustness (, greater eigenvalue) (Figure 1E, arrows) agree with error contours (Figure 1E contours) and have diminished or preserved hub frequency, respectively (Figure 1F activity traces). The directionality of suggests that changes in conductance along this parameter combination will most preserve hub neuron firing between the intrinsic rates of the pyloric and gastric mill rhythms. Importantly and unlike alternative techniques, once an EPI distribution has been learned, the modes and Hessians of the distribution can be measured with trivial computation (see Section 'Deep probability distributions and normalizing flows').

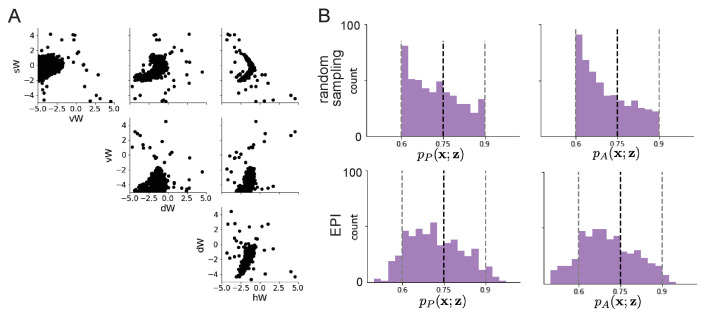

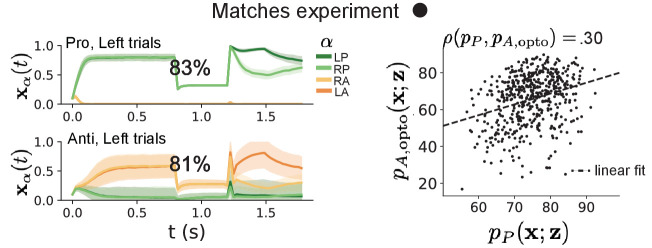

In the following sections, we demonstrate EPI on three neural circuit models across ranges of biological realism, neural system function, and network scale. First, we demonstrate the superior scalability of EPI compared to alternative techniques by inferring high-dimensional distributions of recurrent neural network connectivities that exhibit amplified, yet stable responses. Next, in a model of primary visual cortex (Litwin-Kumar et al., 2016; Palmigiano et al., 2020), we show how EPI discovers parametric degeneracy, revealing how input variability across neuron types affects the excitatory population. Finally, in a model of superior colliculus (Duan et al., 2021), we used EPI to capture multiple parametric regimes of task switching, and queried the dimensions of parameter sensitivity to characterize each regime.

Scaling inference of recurrent neural network connectivity with EPI

To understand how EPI scales in comparison to existing techniques, we consider recurrent neural networks (RNNs). Transient amplification is a hallmark of neural activity throughout cortex and is often thought to be intrinsically generated by recurrent connectivity in the responding cortical area (Murphy and Miller, 2009; Hennequin et al., 2014; Bondanelli et al., 2019). It has been shown that to generate such amplified, yet stabilized responses, the connectivity of RNNs must be non-normal (Goldman, 2009; Murphy and Miller, 2009), and satisfy additional constraints (Bondanelli and Ostojic, 2020). In theoretical neuroscience, RNNs are optimized and then examined to show how dynamical systems could execute a given computation (Sussillo, 2014; Barak, 2017), but such biologically realistic constraints on connectivity (Goldman, 2009; Murphy and Miller, 2009; Bondanelli and Ostojic, 2020) are ignored for simplicity or because constrained optimization is difficult. In general, access to distributions of connectivity that produce theoretical criteria like stable amplification, chaotic fluctuations (Sompolinsky et al., 1988), or low tangling (Russo et al., 2018) would add scientific value to existing research with RNNs. Here, we use EPI to learn RNN connectivities producing stable amplification, and demonstrate the superior scalability and efficiency of EPI to alternative approaches.

We consider a rank-2 RNN with neurons having connectivity and dynamics

| (4) |

where , , , and . We infer connectivity parameters that produce stable amplification. Two conditions are necessary and sufficient for RNNs to exhibit stable amplification (Bondanelli and Ostojic, 2020): and , where is the eigenvalue of with greatest real part and is the maximum eigenvalue of . RNNs with and will be stable with modest decay rate ( close to its upper bound of 1) and exhibit modest amplification ( close to its lower bound of 1). EPI can naturally condition on this emergent property

| (5) |

Variance constraints predicate that the majority of the distribution (within two standard deviations) are within the specified ranges.

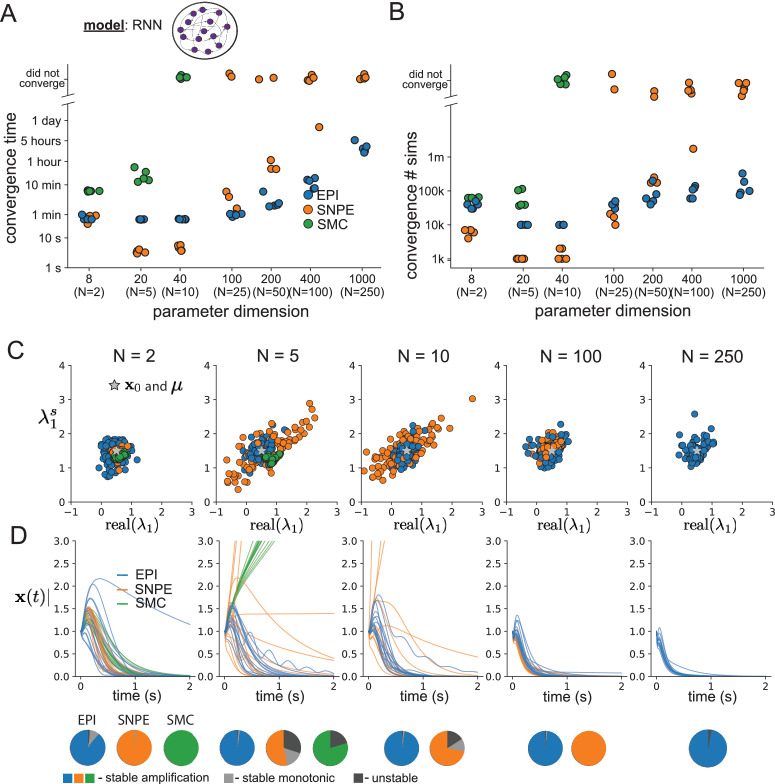

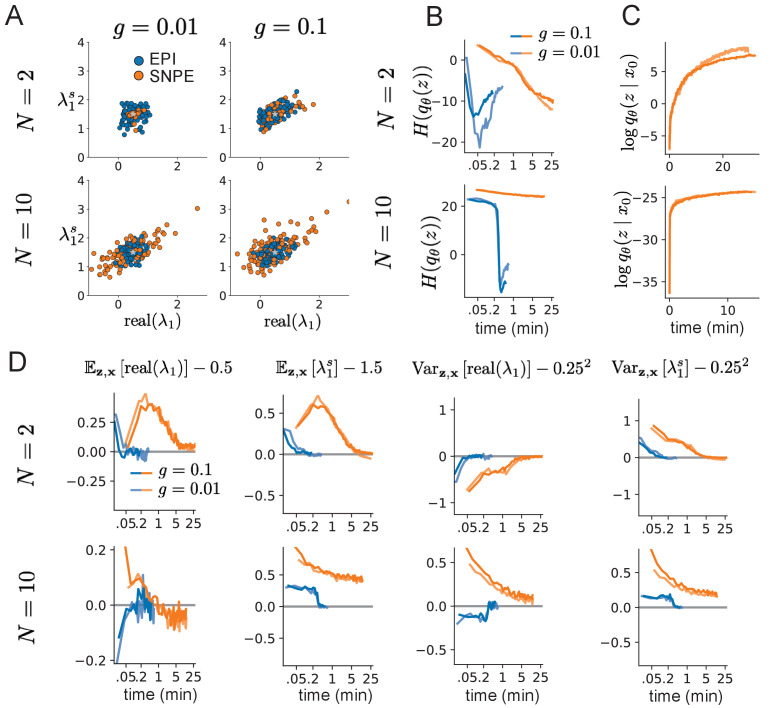

For comparison, we infer the parameters likely to produce stable amplification using two alternative simulation-based inference approaches. Sequential Monte Carlo approximate bayesian computation (SMC-ABC) (Sisson et al., 2007) is a rejection sampling approach that uses SMC techniques to improve efficiency, and sequential neural posterior estimation (SNPE) (Gonçalves et al., 2019) approximates posteriors with deep probability distributions (see Section 'Related approaches'). Unlike EPI, these statistical inference techniques do not constrain the predictions of the inferred distribution, so they were run by conditioning on an exemplar dataset , following standard practice with these methods (Sisson et al., 2007; Gonçalves et al., 2019). To compare the efficiency of these different techniques, we measured the time and number of simulations necessary for the distance of the predictive mean to be less than 0.5 from (see Section 'Scaling EPI for stable amplification in RNNs').

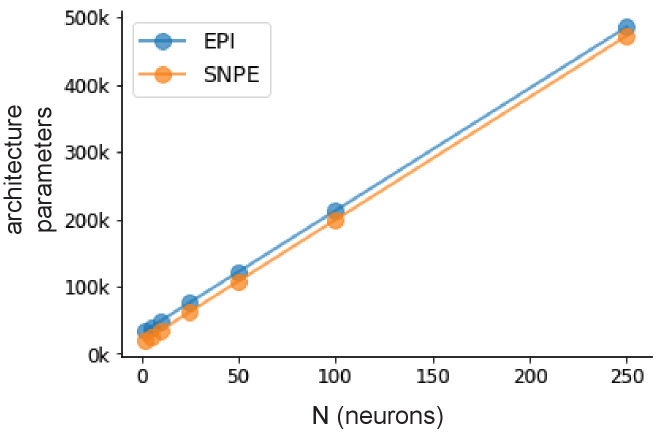

As the number of neurons in the RNN, and thus the dimension of the parameter space , is scaled, we see that EPI converges at greater speed and at greater dimension than SMC-ABC and SNPE (Figure 2A). It also becomes most efficient to use EPI in terms of simulation count at (Figure 2B). It is well known that ABC techniques struggle in parameter spaces of modest dimension (Sisson et al., 2018), yet we were careful to assess the scalability of SNPE, which is a more closely related methodology to EPI. Between EPI and SNPE, we closely controlled the number of parameters in deep probability distributions by dimensionality (Figure 2—figure supplement 1), and tested more aggressive SNPE hyperparameter choices when SNPE failed to converge (Figure 2—figure supplement 2). In this analysis, we see that deep inference techniques EPI and SNPE are far more amenable to inference of high dimensional RNN connectivities than rejection sampling techniques like SMC-ABC, and that EPI outperforms SNPE in both wall time (elapsed real time) and simulation count.

Figure 2. Inferring recurrent neural networks with stable amplification.

(A) Wall time of EPI (blue), SNPE (orange), and SMC-ABC (green) to converge on RNN connectivities producing stable amplification. Each dot shows convergence time for an individual random seed. For reference, the mean wall time for EPI to achieve its full constraint convergence (means and variances) is shown (blue line). (B) Simulation count of each algorithm to achieve convergence. Same conventions as A. (C) The predictive distributions of connectivities inferred by EPI (blue), SNPE (orange), and SMC-ABC (green), with reference to (gray star). (D) Simulations of networks inferred by each method (). Each trace (15 per algorithm) corresponds to simulation of one . (Below) Ratio of obtained samples producing stable amplification, stable monotonic decay, and instability.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Architecture parameter comparison of EPI and SNPE.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. SNPE convergence was enabled by increasing , not .

Figure 2—figure supplement 3. Model characteristics affect predictions of posteriors inferred by SNPE, while predictions of parameters inferred by EPI remain fixed.

No matter the number of neurons, EPI always produces connectivity distributions with mean and variance of and according to (Figure 2C, blue). For the dimensionalities in which SMC-ABC is tractable, the inferred parameters are concentrated and offset from the exemplar dataset (Figure 2C, green). When using SNPE, the predictions of the inferred parameters are highly concentrated at some RNN sizes and widely varied in others (Figure 2C, orange). We see these properties reflected in simulations from the inferred distributions: EPI produces a consistent variety of stable, amplified activity norms , SMC-ABC produces a limited variety of responses, and the changing variety of responses from SNPE emphasizes the control of EPI on parameter predictions (Figure 2D). Even for moderate neuron counts, the predictions of the inferred distribution of SNPE are highly dependent on and , while EPI maintains the emergent property across choices of RNN (see Section 'Effect of RNN parameters on EPI and SNPE inferred distributions').

To understand these differences, note that EPI outperforms SNPE in high dimensions by using gradient information (from ). This choice agrees with recent speculation that such gradient information could improve the efficiency of simulation-based inference techniques (Cranmer et al., 2020), as well as reflecting the classic tradeoff between gradient-based and sampling-based estimators (scaling and speed versus generality). Since gradients of the emergent property are necessary in EPI optimization, gradient tractability is a key criteria when determining the suitability of a simulation-based inference technique. If the emergent property gradient is efficiently calculated, EPI is a clear choice for inferring high dimensional parameter distributions. In the next two sections, we use EPI for novel scientific insight by examining the structure of inferred distributions.

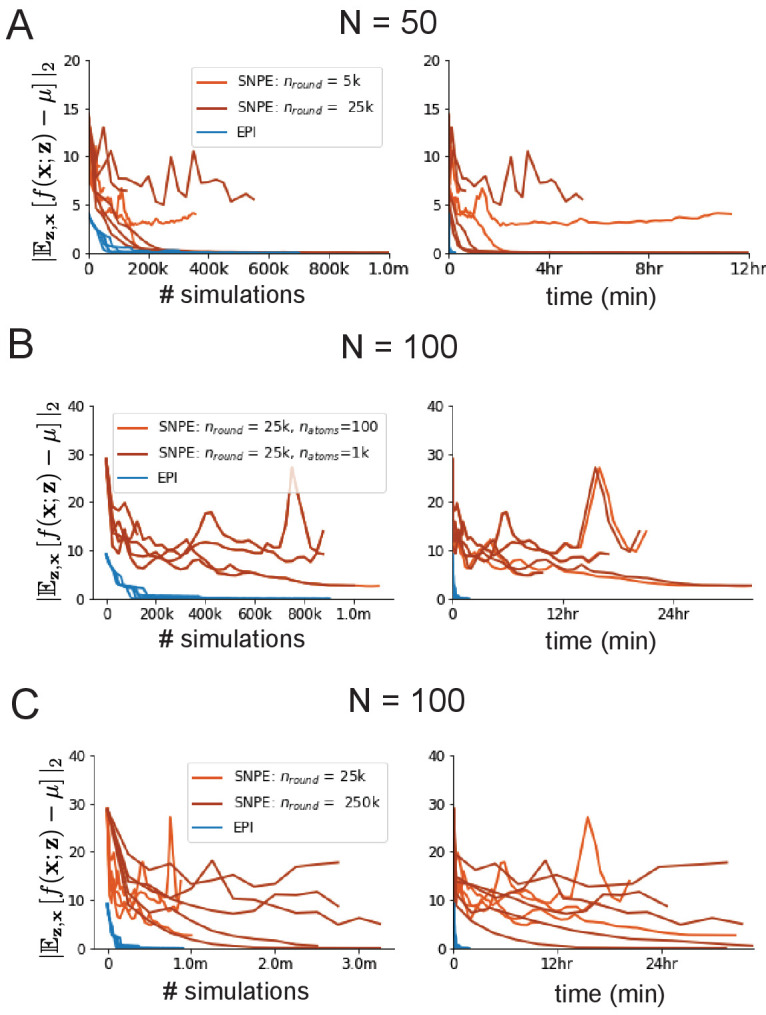

EPI reveals how recurrence with multiple inhibitory subtypes governs excitatory variability in a V1 model

Dynamical models of excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) populations with supralinear input-output function have succeeded in explaining a host of experimentally documented phenomena in primary visual cortex (V1). In a regime characterized by inhibitory stabilization of strong recurrent excitation, these models give rise to paradoxical responses (Tsodyks et al., 1997), selective amplification (Goldman, 2009; Murphy and Miller, 2009), surround suppression (Ozeki et al., 2009), and normalization (Rubin et al., 2015). Recent theoretical work (Hennequin et al., 2018) shows that stabilized E-I models reproduce the effect of variability suppression (Churchland et al., 2010). Furthermore, experimental evidence shows that inhibition is composed of distinct elements – parvalbumin (P), somatostatin (S), VIP (V) – composing 80% of GABAergic interneurons in V1 (Markram et al., 2004; Rudy et al., 2011; Tremblay et al., 2016), and that these inhibitory cell types follow specific connectivity patterns (Figure 3A; Pfeffer et al., 2013). Here, we use EPI on a model of V1 with biologically realistic connectivity to show how the structure of input across neuron types affects the variability of the excitatory population – the population largely responsible for projecting to other brain areas (Felleman and Van Essen, 1991).

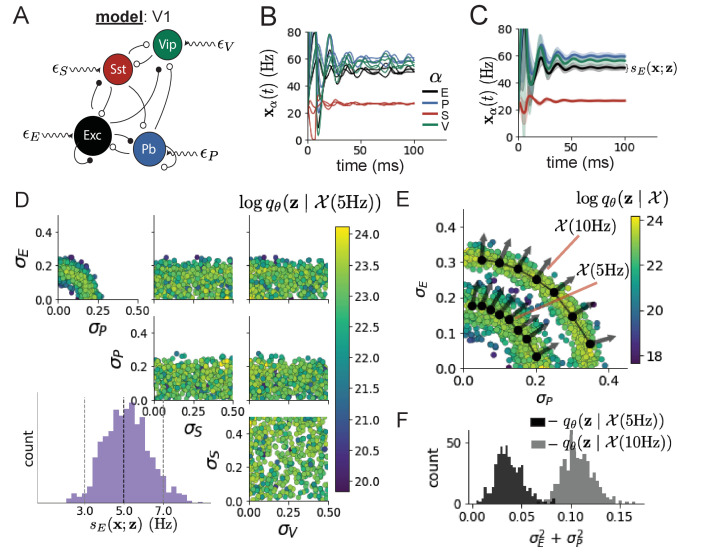

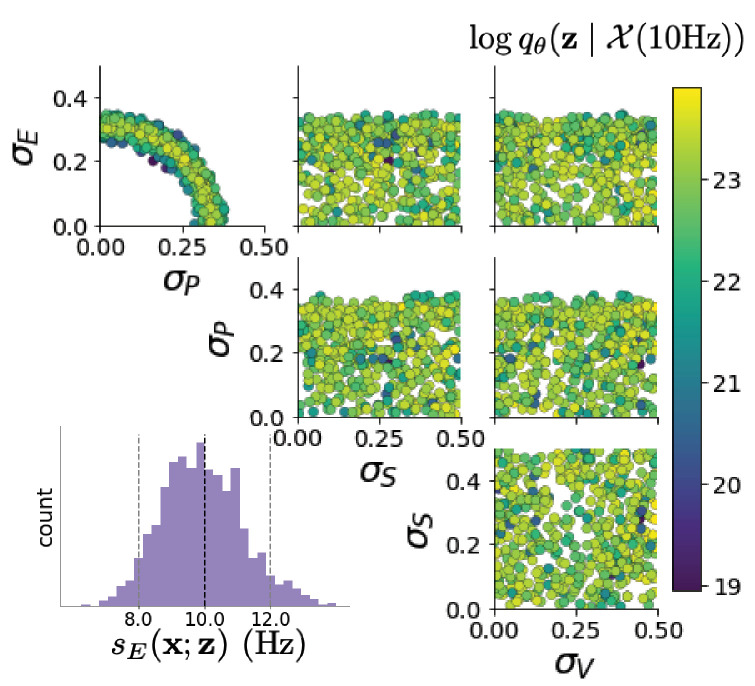

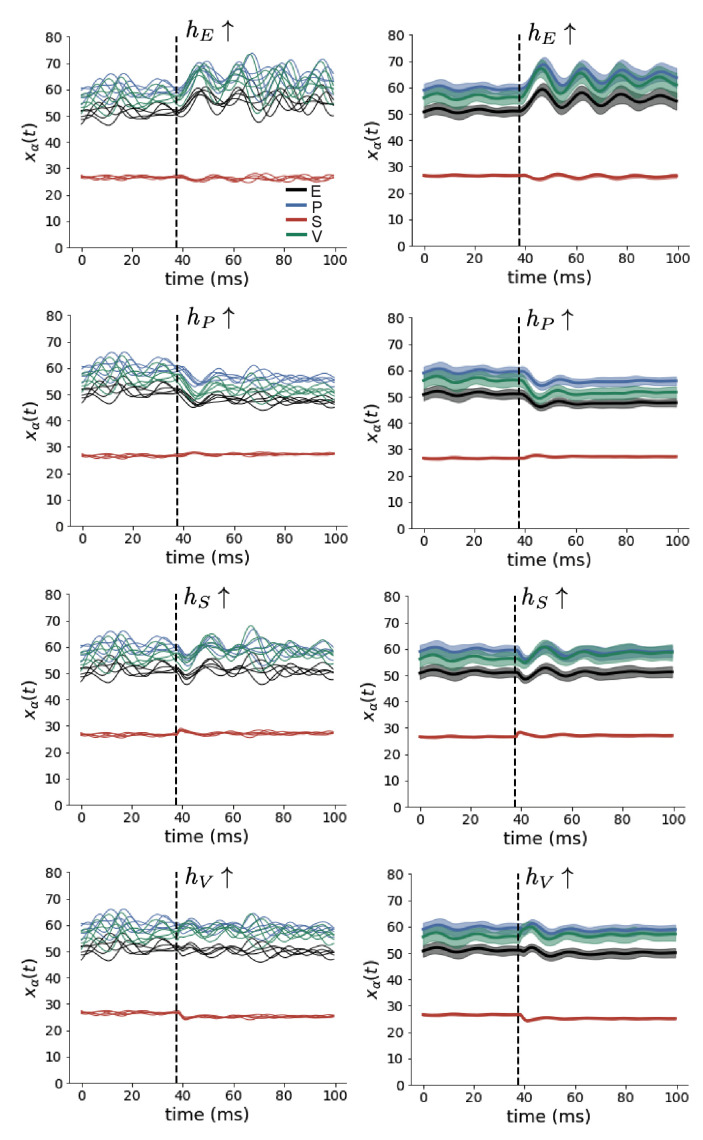

Figure 3. Emergent property inference in the stochastic stabilized supralinear network (SSSN).

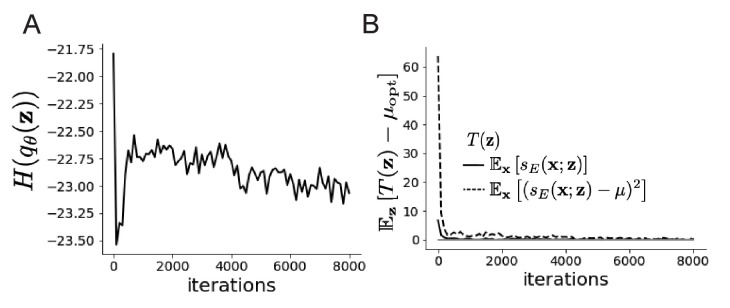

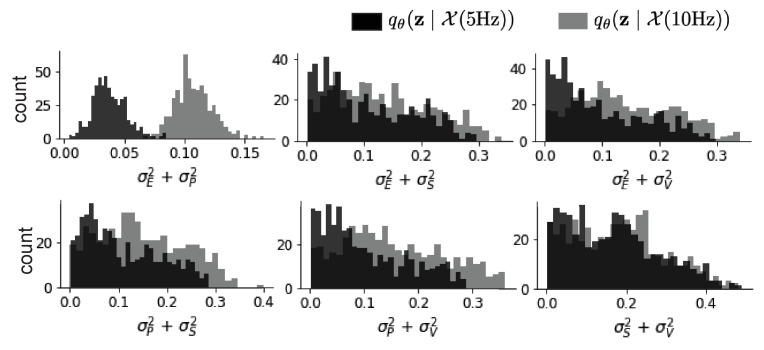

(A) Four-population model of primary visual cortex with excitatory (black), parvalbumin (blue), somatostatin (red), and VIP (green) neurons (excitatory and inhibitory projections filled and unfilled, respectively). Some neuron-types largely do not form synaptic projections to others (). Each neural population receives a baseline input , and the E- and P-populations also receive a contrast-dependent input . Additionally, each neural population receives a slow noisy input . (B) Transient network responses of the SSSN model. Traces are independent trials with varying initialization and noise . (C) Mean (solid line) and standard deviation (shading) across 100 trials. (D) EPI distribution of noise parameters conditioned on E-population variability. The EPI predictive distribution of is show on the bottom-left. (E) (Top) Enlarged visualization of the - marginal distribution of EPI and . Each black dot shows the mode at each . The arrows show the most sensitive dimensions of the Hessian evaluated at these modes. (F) The predictive distributions of of each inferred distribution and .

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. EPI optimization.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. EPI predictive distributions of the sum of squares of each pair of noise parameters.

Figure 3—figure supplement 4. SSSN simulations for small increases in neuron-type population input (left); average (solid) and standard deviation (shaded) of stochastic fluctuations of responses (right).

We considered response variability of a nonlinear dynamical V1 circuit model (Figure 3A) with a state comprised of each neuron-type population’s rate . Each population receives recurrent input , where is the effective connectivity matrix (see Section 'Primary visual cortex') and an external input with mean , which determines population rate via supralinear nonlinearity . The external input has an additive noisy component with variance . This noise has a slower dynamical timescale than the population rate, allowing fluctuations around a stimulus-dependent steady-state (Figure 3B). This model is the stochastic stabilized supralinear network (SSSN) (Hennequin et al., 2018)

| (6) |

generalized to have multiple inhibitory neuron types. It introduces stochasticity to four neuron-type models of V1 (Litwin-Kumar et al., 2016). Stochasticity and inhibitory multiplicity introduce substantial complexity to the mathematical treatment of this problem (see Section 'Primary visual cortex: Mathematical intuition and challenges') motivating the analysis of this model with EPI. Here, we consider fixed weights and input (Palmigiano et al., 2020), and study the effect of input variability on excitatory variability.

We quantify levels of E-population variability by studying two emergent properties

| (7) |

where is the standard deviation of the stochastic -population response about its steady state (Figure 3C). In the following analyses, we select 1 Hz2 variance such that the two emergent properties do not overlap in .

First, we ran EPI to obtain parameter distribution producing E-population variability around 5 Hz (Figure 3D). From the marginal distribution of and (Figure 3D, top-left), we can see that is sensitive to various combinations of and . Alternatively, both and are degenerate with respect to evidenced by the unexpectedly high variability in those dimensions (Figure 3D, bottom-right). Together, these observations imply a curved path with respect to of 5 Hz, which is indicated by the modes along (Figure 3E).

Figure 3E suggests a quadratic relationship in E-population fluctuations and the standard deviation of E- and P-population input; as the square of either or increases, the other compensates by decreasing to preserve the level of . This quadratic relationship is preserved at greater level of E-population variability (Figure 3E and Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Indeed, the sum of squares of and is larger in than (Figure 3F, ), while the sum of squares of and are not significantly different in the two EPI distributions (Figure 3—figure supplement 3, ), in which parameters were bounded from 0 to 0.5. The strong interaction between E- and P-population input variability on excitatory variability is intriguing, since this circuit exhibits a paradoxical effect in the P-population (and no other inhibitory types) (Figure 3—figure supplement 4), meaning that the E-population is P-stabilized. Future research may uncover a link between the population of network stabilization and compensatory interactions governing excitatory variability.

EPI revealed the quadratic dependence of excitatory variability on input variability to the E- and P-populations, as well as its independence to input from the other two inhibitory populations. In a simplified model (), it can be shown that surfaces of equal variance are ellipsoids as a function of (see Section 'Primary visual cortex: Mathematical intuition and challenges'). Nevertheless, the sensitive and degenerate parameters are intractable to predict mathematically, since the covariance matrix depends on the steady-state solution of the network (Hennequin et al., 2018; Gardiner, 2009), and terms in the covariance expression increase quadratically with each additional neuron-type population (see also Section 'Primary visual cortex: Mathematical intuition and challenges'). By pointing out this mathematical complexity, we emphasize the value of EPI for gaining understanding about theoretical models when mathematical analysis becomes onerous or impractical.

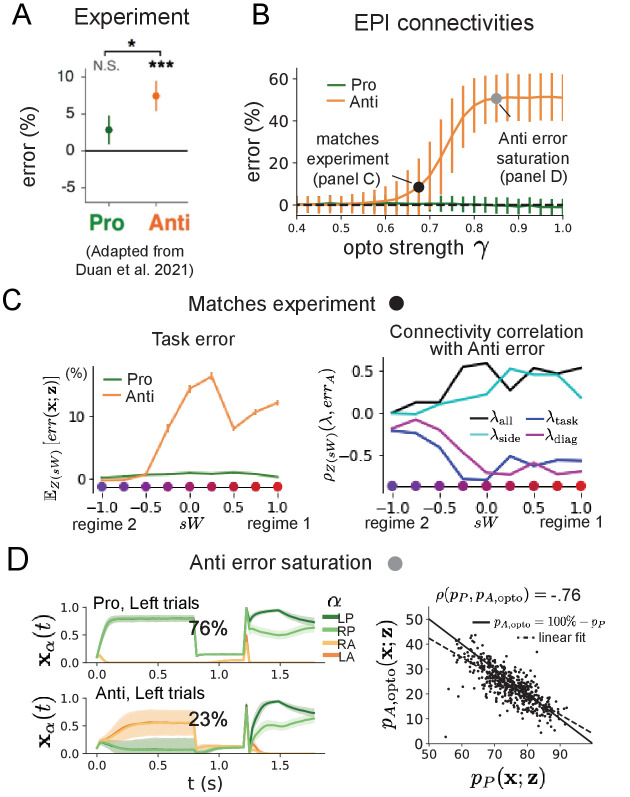

EPI identifies two regimes of rapid task switching

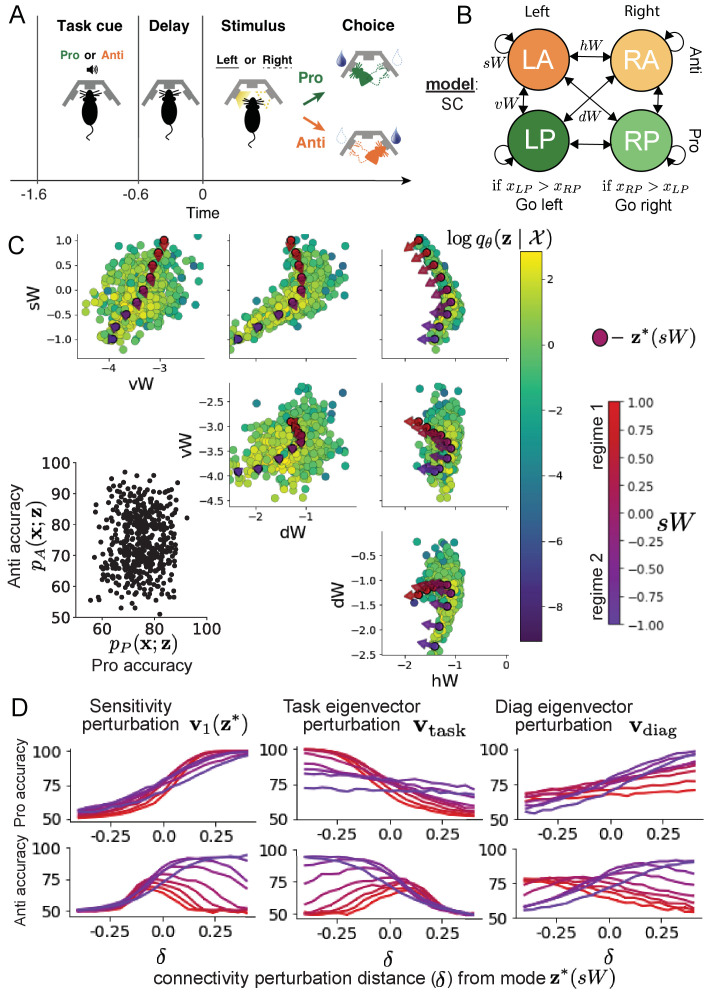

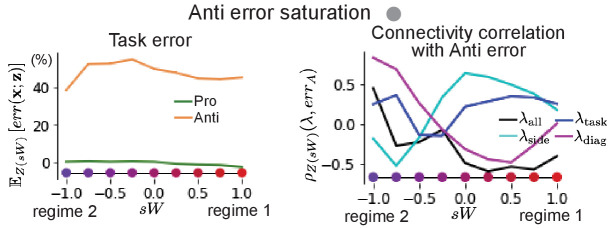

It has been shown that rats can learn to switch from one behavioral task to the next on randomly interleaved trials (Duan et al., 2015), and an important question is what neural mechanisms produce this computation. In this experimental setup, rats were given an explicit task cue on each trial, either Pro or Anti. After a delay period, rats were shown a stimulus, and made a context (task) dependent response (Figure 4A). In the Pro task, rats were required to orient toward the stimulus, while in the Anti task, rats were required to orient away from the stimulus. Pharmacological inactivation of the SC impaired rat performance, and time-specific optogenetic inactivation revealed a crucial role for the SC on the cognitively demanding Anti trials (Duan et al., 2021). These results motivated a nonlinear dynamical model of the SC containing four functionally defined neuron-type populations. In Duan et al., 2021, a computationally intensive procedure was used to obtain a set of 373 connectivity parameters that qualitatively reproduced these optogenetic inactivation results. To build upon the insights of this previous work, we use the probabilistic tools afforded by EPI to identify and characterize two linked, yet distinct regimes of rapid task switching connectivity.

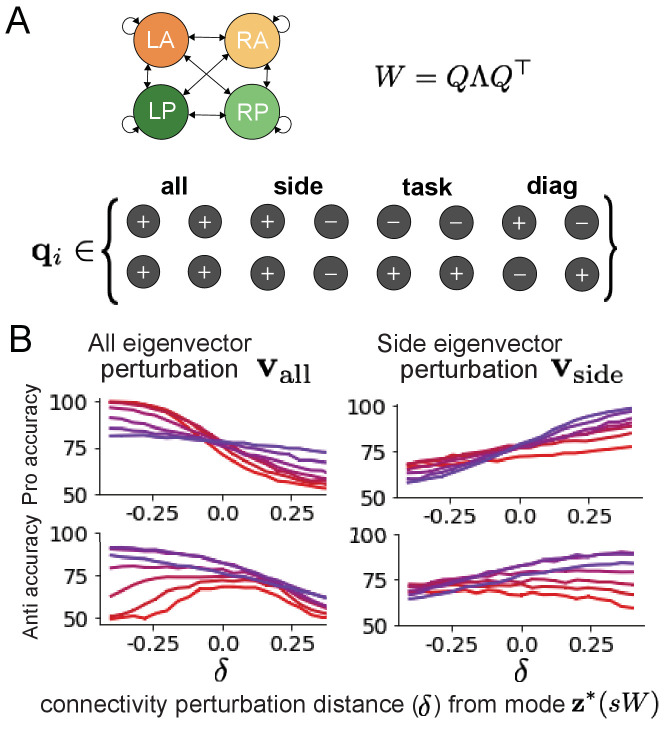

Figure 4. Inferring rapid task switching networks in superior colliculus.

(A) Rapid task switching behavioral paradigm (see text). (B) Model of superior colliculus (SC). Neurons: LP - Left Pro, RP - Right Pro, LA - Left Anti, RA - Right Anti. Parameters: - self, - horizontal, -vertical, - diagonal weights. (C) The EPI inferred distribution of rapid task switching networks. Red/purple parameters indicate modes colored by . Sensitivity vectors are shown by arrows. (Bottom-left) EPI predictive distribution of task accuracies. (D) Mean and standard error ( = 25, bars not visible) of accuracy in Pro (top) and Anti (bottom) tasks after perturbing connectivity away from mode along (left), (middle), and (right).

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Task accuracy by EPI inferred SC network connectivity.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. SC network simulations by regime.

Figure 4—figure supplement 3. Eigenmodes of SC connectivity.

Figure 4—figure supplement 4. EPI optimization of the SC model producing rapid task switching.

Figure 4—figure supplement 5. SC connectivities obtained through brute-force sampling.

In this SC model, there are Pro- and Anti-populations in each hemisphere (left (L) and right (R)) with activity variables (Duan et al., 2021). The connectivity of these populations is parameterized by self , vertical , diagonal and horizontal connections (Figure 4B). The input is comprised of a positive cue-dependent signal to the Pro- or Anti-populations, a positive stimulus-dependent input to either the Left or Right populations, and a choice-period input to the entire network (see Section 'SC model'). Model responses are bounded from 0 to 1 as a function of an internal variable

| (8) |

The model responds to the side with greater Pro neuron activation; for example the response is left if at the end of the trial. Here, we use EPI to determine the network connectivity that produces rapid task switching.

Rapid task switching is formalized mathematically as an emergent property with two statistics: accuracy in the Pro task and Anti task . We stipulate that accuracy be on average 0.75 in each task with variance

| (9) |

Seventy-five percent accuracy is a realistic level of performance in each task, and with the chosen variance, inferred models will not exhibit fully random responses (50%), nor perfect performance (100%).

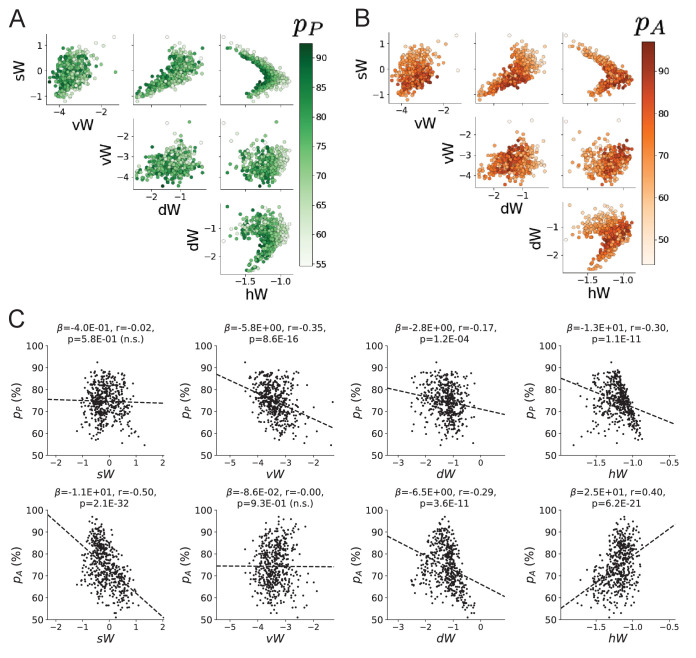

The EPI inferred distribution (Figure 4C) produces Pro- and Anti-task accuracies (Figure 4C, bottom-left) consistent with rapid task switching (Equation 9). This parameter distribution has rich structure that is not captured well by simple linear correlations (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). Specifically, the shape of the EPI distribution is sharply bent, matching ground truth structure indicated by brute-force sampling (Figure 4—figure supplement 5). This is most saliently observed in the marginal distribution of - (Figure 4C top-right), where anticorrelation between and switches to correlation with decreasing . By identifying the modes of the EPI distribution at different values of (Figure 4C red/purple dots), we can quantify this change in distributional structure with the sensitivity dimension (Figure 4C red/purple arrows). Note that the directionality of these sensitivity dimensions at changes distinctly with , and are perpendicular to the robust dimensions of the EPI distribution that preserve rapid task switching. These two directionalities of sensitivity motivate the distinction of connectivity into two regimes, which produce different types of responses in the Pro and Anti tasks (Figure 4—figure supplement 2).

When perturbing connectivity along the sensitivity dimension away from the modes

| (10) |

Pro-accuracy monotonically increases in both regimes (Figure 4D, top-left). However, there is a stark difference between regimes in Anti-accuracy. Anti-accuracy falls in either direction of in regime 1, yet monotonically increases along with Pro accuracy in regime 2 (Figure 4D, bottom-left). The sharp change in local structure of the EPI distribution is therefore explained by distinct sensitivities: Anti-accuracy diminishes in only one or both directions of the sensitivity perturbation.

To understand the mechanisms differentiating the two regimes, we can make connectivity perturbations along dimensions that only modify a single eigenvalue of the connectivity matrix. These eigenvalues , , , and correspond to connectivity eigenmodes with intuitive roles in processing in this task (Figure 4—figure supplement 3A). For example, greater will strengthen internal representations of task, while greater will amplify dominance of Pro and Anti pairs in opposite hemispheres (Section 'Connectivity eigendecomposition and processing modes'). Unlike the sensitivity dimension, the dimensions that perturb isolated connectivity eigenvalues for are independent of (see Section 'Connectivity eigendecomposition and processing modes'), e.g.

| (11) |

Connectivity perturbation analyses reveal that decreasing has a very similar effect on Anti accuracy as perturbations along the sensitivity dimension (Figure 4D, middle). The similar effects of perturbations along the sensitivity dimension and reduction of task eigenvalue (via perturbations along ) suggest that there is a carefully tuned strength of task representation in connectivity regime 1, which if disturbed results in random Anti-trial responses. Finally, we recognize that increasing has opposite effects on Anti-accuracy in each regime (Figure 4D, right). In the next section, we build on these mechanistic characterizations of each regime by examining their resilience to optogenetic inactivation.

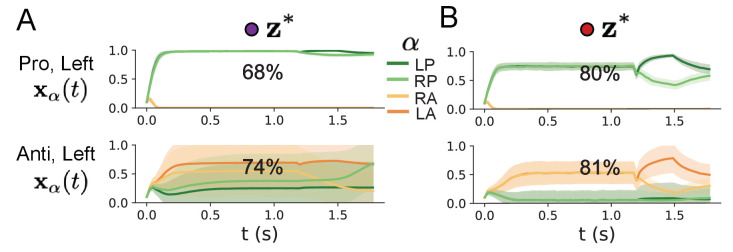

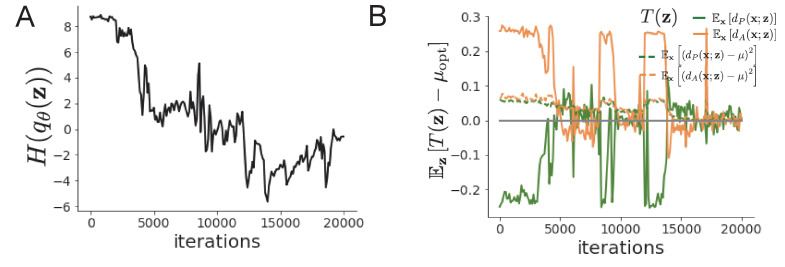

EPI inferred SC connectivities reproduce results from optogenetic inactivation experiments

During the delay period of this task, the circuit must prepare to execute the correct task according to the presented cue. The circuit must then maintain a representation of task throughout the delay period, which is important for correct execution of the Anti-task. Duan et al. found that bilateral optogenetic inactivation of SC during the delay period consistently decreased performance in the Anti-task, but had no effect on the Pro-task (Figure 5A; Duan et al., 2021). The distribution of connectivities inferred by EPI exhibited this same effect in simulation at high optogenetic strengths γ, which reduce the network activities by a factor (Figure 5B) (see Section 'Modeling optogenetic silencing').

Figure 5. Responses to optogenetic perturbation by connectivity regime.

(A) Mean and standard error (bars) across recording sessions of task error following delay period optogenetic inactivation in rats. (B) Mean and standard deviation (bars) of task error induced by delay period inactivation of varying optogenetic strength γ across the EPI distribution. (C) (Left) Mean and standard error of Pro and Anti error from regime 1 to regime 2 at . (Right) Correlations of connectivity eigenvalues with Anti error from regime 1 to regime 2 at . (D) (Left) Mean and standard deviation (shading) of responses of the SC model at the mode of the EPI distribution to delay period inactivation at . Accuracy in Pro (top) and Anti (bottom) task is shown as a percentage. (Right) Anti-accuracy following delay period inactivation at versus accuracy in the Pro-task across connectivities in the EPI distribution.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. SC responses to delay period inactivation at Anti error saturating levels.

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. SC responses to delay period inactivation at experiment matching levels.

To examine how connectivity affects response to delay period inactivation, we grouped connectivities of the EPI distribution along the continuum linking regimes 1 and 2 of Section 'EPI identifies two regimes of rapid task switching'. is the set of EPI samples for which the closest mode was (see Section 'Mode identification with EPI'). In the following analyses, we examine how error, and the influence of connectivity eigenvalue on Anti-error change along this continuum of connectivities. Obtaining the parameter samples for these analysis with the learned EPI distribution was more than 20,000 times faster than a brute force approach (see Section 'Sample grouping by mode').

The mean increase in Anti-error of the EPI distribution is closest to the experimentally measured value of 7% at (Figure 5B, black dot). At this level of optogenetic strength, regime 1 exhibits an increase in Anti-error with delay period silencing (Figure 5C, left), while regime 2 does not. In regime 1, greater and decrease Anti-error (Figure 5C, right). In other words, stronger task representations and diagonal amplification make the SC model more resilient to delay period silencing in the Anti-task. This complements the finding from Duan et al., 2021 (Duan et al., 2021) that and improve Anti accuracy.

At roughly (Figure 5B, gray dot), the Anti-error saturates, while Pro-error remains at zero. Following delay period inactivation at this optogenetic strength, there are strong similarities in the responses of Pro- and Anti-trials during the choice period (Figure 5D, left). We interpreted these similarities to suggest that delay period inactivation at this saturated level flips the internal representation of task (from Anti to Pro) in the circuit model. A flipped task representation would explain why the Anti-error saturates at 50%: the average Anti-accuracy in EPI inferred connectivities is 75%, but average Anti accuracy would be 25% (100% - ) if the internal representation of task is flipped during the delay period.This hypothesis prescribes a model of Anti-accuracy during delay period silencing of , which is fit closely across both regimes of the EPI inferred connectivities (Figure 5D, right). Similarities between Pro- and Anti-trial responses were not present at the experiment-matching level of (Figure 5—figure supplement 2 left) and neither was anticorrelation in and (Figure 5—figure supplement 2 right).

In summary, the connectivity inferred by EPI to perform rapid task switching replicated results from optogenetic silencing experiments. We found that at levels of optogenetic strength matching experimental levels of Anti-error, only one regime actually exhibited the effect. This connectivity regime is less resilient to optogenetic perturbation, and perhaps more biologically realistic. Finally, we characterized the pathology in Anti-error that occurs in both regimes when optogenetic strength is increased to high levels, leading to a mechanistic hypothesis that is experimentally testable. The probabilistic tools afforded by EPI yielded this insight: we identified two regimes and the continuum of connectivities between them by taking gradients of parameter probabilities in the EPI distribution, we identified sensitivity dimensions by measuring the Hessian of the EPI distribution, and we obtained many parameter samples at each step along the continuum at an efficient rate.

Discussion

In neuroscience, machine learning has primarily been used to reveal structure in neural datasets (Paninski and Cunningham, 2018). Careful inference procedures are developed for these statistical models allowing precise, quantitative reasoning, which clarifies the way data informs beliefs about the model parameters. However, these statistical models often lack resemblance to the underlying biology, making it unclear how to go from the structure revealed by these methods, to the neural mechanisms giving rise to it. In contrast, theoretical neuroscience has primarily focused on careful models of neural circuits and the production of emergent properties of computation, rather than measuring structure in neural datasets. In this work, we improve upon parameter inference techniques in theoretical neuroscience with emergent property inference, harnessing deep learning towards parameter inference in neural circuit models (see Section 'Related approaches').

Methodology for statistical inference in circuit models has evolved considerably in recent years. Early work used rejection sampling techniques (Beaumont et al., 2002; Marjoram et al., 2003; Sisson et al., 2007), but EPI and another recently developed methodology (Gonçalves et al., 2019) employ deep learning to improve efficiency and provide flexible approximations. SNPE has been used for posterior inference of parameters in circuit models conditioned upon exemplar data used to represent computation, but it does not infer parameter distributions that only produce the computation of interest like EPI (see Section 'Scaling inference of recurrent neural network connectivity with EPI'). When strict control over the predictions of the inferred parameters is necessary, EPI uses a constrained optimization technique (Loaiza-Ganem et al., 2017) (see Section 'Augmented lagrangian optimization') to make inference conditioned on the emergent property possible.

A key difference between EPI and SNPE, is that EPI uses gradients of the emergent property throughout optimization. In Section 'Scaling inference of recurrent neural network connectivity with EPI', we showed that such gradients confer beneficial scaling properties, but a concern remains that emergent property gradients may be too computationally intensive. Even in a case of close biophysical realism with an expensive emergent property gradient, EPI was run successfully on intermediate hub frequency in a five-neuron subcircuit model of the STG (Section 'Motivating emergent property inference of theoretical models'). However, conditioning on the pyloric rhythm (Marder and Selverston, 1992) in a model of the pyloric subnetwork model (Prinz et al., 2004) proved to be prohibitive with EPI. The pyloric subnetwork requires many time steps for simulation and many key emergent property statistics (e.g. burst duration and phase gap) are not calculable or easily approximated with differentiable functions. In such cases, SNPE, which does not require differentiability of the emergent property, has proven useful (Gonçalves et al., 2019). In summary, choice of deep inference technique should consider emergent property complexity and differentiability, dimensionality of parameter space, and the importance of constraining the model behavior predicted by the inferred parameter distribution.

In this paper, we demonstrate the value of deep inference for parameter sensitivity analyses at both the local and global level. With these techniques, flexible deep probability distributions are optimized to capture global structure by approximating the full distribution of suitable parameters. Importantly, the local structure of this deep probability distribution can be quantified at any parameter choice, offering instant sensitivity measurements after fitting. For example, the global structure captured by EPI revealed two distinct parameter regimes, which had different local structure quantified by the deep probability distribution (see Section 'Superior colliculus'). In comparison, bayesian MCMC is considered a popular approach for capturing global parameter structure (Girolami and Calderhead, 2011), but there is no variational approximation (the deep probability distribution in EPI), so sensitivity information is not queryable and sampling remains slow after convergence. Local sensitivity analyses (e.g. Raue et al., 2009) may be performed independently at individual parameter samples, but these methods alone do not capture the full picture in nonlinear, complex distributions. In contrast, deep inference yields a probability distribution that produces a wholistic assessment of parameter sensitivity at the local and global level, which we used in this study to make novel insights into a range of theoretical models. Together, the abilities to condition upon emergent properties, the efficient inference algorithm, and the capacity for parameter sensitivity analyses make EPI a useful method for addressing inverse problems in theoretical neuroscience.

Code availability statement

All software written for this study is available at https://github.com/cunningham-lab/epi (copy archived at swh:1:rev:38febae7035ca921334a616b0f396b3767bf18d4), Bittner, 2021.

Materials and methods

Emergent property inference (EPI)

Solving inverse problems is an important part of theoretical neuroscience, since we must understand how neural circuit models and their parameter choices produce computations. Recently, research on machine learning methodology for neuroscience has focused on finding latent structure in large-scale neural datasets, while research in theoretical neuroscience generally focuses on developing precise neural circuit models that can produce computations of interest. By quantifying computation into an emergent property through statistics of the emergent activity of neural circuit models, we can adapt the modern technique of deep probabilistic inference towards solving inverse problems in theoretical neuroscience. Here, we introduce a novel method for statistical inference, which uses deep networks to learn parameter distributions constrained to produce emergent properties of computation.

Consider model parameterization , which is a collection of scientifically meaningful variables that govern the complex simulation of data . For example (see Section 'Motivating emergent property inference of theoretical models'), may be the electrical conductance parameters of an STG subcircuit, and the evolving membrane potentials of the five neurons. In terms of statistical modeling, this circuit model has an intractable likelihood , which is predicated by the stochastic differential equations that define the model. From a theoretical perspective, we are less concerned about the likelihood of an exemplar dataset , but rather the emergent property of intermediate hub frequency (which implies a consistent dataset ).

In this work, emergent properties are defined through the choice of emergent property statistic (which is a vector of one or more statistics), and its means , and variances :

| (12) |

In general, an emergent property may be a collection of first-, second-, or higher-order moments of a group of statistics, but this study focuses on the case written in Equation 12. In the STG example, intermediate hub frequency is defined by mean and variance constraints on the statistic of hub neuron frequency (Equations 2 and 3). Precisely, the emergent property statistics must have means and variances over the EPI distribution of parameters () and the data produced by those parameters (), where the inferred parameter distribution itself is parameterized by deep network weights and biases .

In EPI, a deep probability distribution is optimized to approximate the parameter distribution producing the emergent property . In contrast to simpler classes of distributions like the gaussian or mixture of gaussians, deep probability distributions are far more flexible and capable of fitting rich structure (Rezende and Mohamed, 2015; Papamakarios et al., 2019a). In deep probability distributions, a simple random variable (we choose an isotropic gaussian) is mapped deterministically via a sequence of deep neural network layers (g1, . gl) parameterized by weights and biases to the support of the distribution of interest:

| (13) |

Such deep probability distributions embed the inferred distribution in a deep network. Once optimized, this deep network representation of a distribution has remarkably useful properties: fast sampling and probability evaluations. Importantly, fast probability evaluations confer fast gradient and Hessian calculations as well.

Given this choice of circuit model and emergent property , is optimized via the neural network parameters to find a maximally entropic distribution within the deep variational family that produces the emergent property :

| (14) |

where is entropy. By maximizing the entropy of the inferred distribution , we select the most random distribution in family that satisfies the constraints of the emergent property. Since entropy is maximized in Equation 14, EPI is equivalent to bayesian variational inference (see Section 'EPI as variational inference'), which is why we specify the inferred distribution of EPI as conditioned upon emergent property with the notation . To run this constrained optimization, we use an augmented lagrangian objective, which is the standard approach for constrained optimization (Bertsekas, 2014), and the approach taken to fit Maximum Entropy Flow Networks (MEFNs) (Loaiza-Ganem et al., 2017). This procedure is detailed in Section 'Augmented lagrangian optimization' and the pseudocode in Algorithm 'Augmented lagrangian optimization'.

In the remainder of Section 'Emergent property inference (EPI)', we will explain the finer details and motivation of the EPI method. First, we explain related approaches and what EPI introduces to this domain (Section 'Related approaches'). Second, we describe the special class of deep probability distributions used in EPI called normalizing flows (Section 'Deep probability distributions and normalizing flows'). Then, we establish the known relationship between maximum entropy distributions and exponential families (Section 'Maximum entropy distributions and exponential families'). Next, we explain the constrained optimization technique used to solve Equation 14 (Section 'Augmented lagrangian optimization'). Then, we demonstrate the details of this optimization in a toy example (Section 'Example: 2D LDS'). Finally, we explain how EPI is equivalent to variational inference (Section 'EPI as variational inference').

Related approaches

When bayesian inference problems lack conjugacy, scientists use approximate inference methods like variational inference (VI) (Saul and Jordan, 1998) and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) (Metropolis et al., 1953; Hastings, 1970). After optimization, variational methods return a parameterized posterior distribution, which we can analyze. Also, the variational approximation is often chosen such that it permits fast sampling. In contrast MCMC methods only produce samples from the approximated posterior distribution. No parameterized distribution is estimated, and additional samples are always generated with the same sampling complexity. Inference in models defined by systems of differential has been demonstrated with MCMC (Girolami and Calderhead, 2011), although this approach requires tractable likelihoods. Advancements have introduced sampling (Calderhead and Girolami, 2011), likelihood approximation (Golightly and Wilkinson, 2011), and uncertainty quantification techniques (Chkrebtii et al., 2016) to make MCMC approaches more efficient and expand the class of applicable models.

Simulation-based inference (Cranmer et al., 2020) is model parameter inference in the absence of a tractable likelihood function. The most prevalent approach to simulation-based inference is approximate bayesian computation (ABC) (Beaumont et al., 2002), in which satisfactory parameter samples are kept from random prior sampling according to a rejection heuristic. The obtained set of parameters do not have a probabilities, and further insight about the model must be gained from examination of the parameter set and their generated activity. Methodological advances to ABC methods have come through the use of Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC-ABC) (Marjoram et al., 2003) and sequential Monte Carlo (SMC-ABC) (Sisson et al., 2007) sampling techniques. SMC-ABC is considered state-of-the-art ABC, yet this approach still struggles to scale in dimensionality (Sisson et al., 2018; Figure 2). Still, this method has enjoyed much success in systems biology (Liepe et al., 2014). Furthermore, once a parameter set has been obtained by SMC-ABC from a finite set of particles, the SMC-ABC algorithm must be run again from scratch with a new population of initialized particles to obtain additional samples.

For scientific model analysis, we seek a parameter distribution represented by an approximating distribution as in variational inference (Saul and Jordan, 1998): a variational approximation that once optimized yields fast analytic calculations and samples. For the reasons described above, ABC and MCMC techniques are not suitable, because they only produce a set of parameter samples lacking probabilities and have unchanging sampling rate. EPI infers parameters in circuit models using the MEFN (Loaiza-Ganem et al., 2017) algorithm with a deep variational approximation. The deep neural network of EPI (Figure 1E) defines the parametric form (with weights and biases as variational parameters ) of the variational approximation of the inferred parameter distribution . The EPI optimization is enabled using stochastic gradient techniques in the spirit of likelihood-free variational inference (Tran et al., 2017). The analytic relationship between EPI and variational inference is explained in Section 'EPI as variational inference'.

We note that, during our preparation and early presentation of this work (Bittner et al., 2019a; Bittner et al., 2019b), another work has arisen with broadly similar goals: bringing statistical inference to mechanistic models of neural circuits (Nonnenmacher et al., 2018; Michael et al., 2019; Gonçalves et al., 2019). We are encouraged by this general problem being recognized by others in the community, and we emphasize that these works offer complementary neuroscientific contributions (different theoretical models of focus) and use different technical methodologies (ours is built on our prior work [Loaiza-Ganem et al., 2017], theirs similarly [Lueckmann et al., 2017]).

The method EPI differs from SNPE in some key ways. SNPE belongs to a ‘sequential’ class of recently developed simulation-based inference methods in which two neural networks are used for posterior inference. This first neural network is a deep probability distribution (normalizing flow) used to estimate the posterior (SNPE) or the likelihood (sequential neural likelihood (SNL) [Papamakarios et al., 2019b]). A recent approach uses an unconstrained neural network to estimate the likelihood ratio (sequential neural ratio estimation (SNRE) [Hermans et al., 2020]). In SNL and SNRE, MCMC sampling techniques are used to obtain samples from the approximated posterior. This contrasts with EPI and SNPE, which use deep probability distributions to model parameters, which facilitates immediate measurements of sample probability, gradient, or Hessian for system analysis. The second neural network in this sequential class of methods is the amortizer. This unconstrained deep network maps data (or statistics or model parameters ) to the weights and biases of the first neural network. These methods are optimized on a conditional density (or ratio) estimation objective. The data used to optimize this objective are generated via an adaptive procedure, in which training data pairs (, ) become sequentially closer to the true data and posterior.

The approximating fidelity of the deep probability distribution in sequential approaches is optimized to generalize across the training distribution of the conditioning variable. This generalization property of the sequential methods can reduce the accuracy at the singular posterior of interest. Whereas in EPI, the entire expressivity of the deep probability distribution is dedicated to learning a single distribution as well as possible. The well-known inverse mapping problem of exponential families (Wainwright and Jordan, 2008) prohibits an amortization-based approach in EPI, since EPI learns an exponential family distribution parameterized by its mean (in contrast to its natural parameter, see Section 'Maximum entropy distributions and exponential families'). However, we have shown that the same two-network architecture of the sequential simulation-based inference methods can be used for amortized inference in intractable exponential family posteriors when using their natural parameterization (Bittner and Cunningham, 2019).

Finally, one important differentiating factor between EPI and sequential simulation-based inference methods is that EPI leverages gradients during optimization. These gradients can improve convergence time and scalability, as we have shown on an example conditioning low-rank RNN connectivity on the property of stable amplification (see Section 'Scaling inference of recurrent neural network connectivity with EPI'). With EPI, we prove out the suggestion that a deep inference technique can improve efficiency by leveraging these emergent property gradients when they are tractable. Sequential simulation-based inference techniques may be better suited for scientific problems where is intractable or unavailable, like when there is a nondifferentiable emergent property. However, the sequential simulation-based inference techniques cannot constrain the predictions of the inferred distribution in the manner of EPI.

Structural identifiability analysis involves the measurement of sensitivity and unidentifiabilities in scientific models. Around a single parameter choice, one can measure the Jacobian. One approach for this calculation that scales well is EAR (Karlsson et al., 2012). A popular efficient approach for systems of ODEs has been neural ODE adjoint (Chen et al., 2018) and its stochastic adaptation (Li et al., 2020). Casting identifiability as a statistical estimation problem, the profile likelihood works via iterated optimization while holding parameters fixed (Raue et al., 2009). An exciting recent method is capable of recovering the functional form of such unidentifiabilities away from a point by following degenerate dimensions of the fisher information matrix (Raman et al., 2017). Global structural non-identifiabilities can be found for models with polynomial or rational dynamics equations using DAISY (Pia Saccomani et al., 2003), or through mean optimal transformations (Hengl et al., 2007). With EPI, we have all the benefits given by a statistical inference method plus the ability to query the first- or second-order gradient of the probability of the inferred distribution at any chosen parameter value. The second-order gradient of the log probability (the Hessian), which is directly afforded by EPI distributions, produces quantified information about parametric sensitivity of the emergent property in parameter space (see Section 'Emergent property inference via deep generative models').

Deep probability distributions and normalizing flows

Deep probability distributions are comprised of multiple layers of fully connected neural networks (Equation 13). When each neural network layer is restricted to be a bijective function, the sample density can be calculated using the change of variables formula at each layer of the network. For ,

| (15) |

However, this computation has cubic complexity in dimensionality for fully connected layers. By restricting our layers to normalizing flows (Rezende and Mohamed, 2015; Papamakarios et al., 2019a) – bijective functions with fast log determinant Jacobian computations, which confer a fast calculation of the sample log probability. Fast log probability calculation confers efficient optimization of the maximum entropy objective (see Section 'Augmented lagrangian optimization').

We use the real NVP (Dinh et al., 2017) normalizing flow class, because its coupling architecture confers both fast sampling (forward) and fast log probability evaluation (backward). Fast probability evaluation facilitates fast gradient and Hessian evaluation of log probability throughout parameter space. Glow permutations were used in between coupling stages (Kingma and Dhariwal, 2018). This is in contrast to autoregressive architectures (Papamakarios et al., 2017; Kingma et al., 2016), in which only one of the forward or backward passes can be efficient. In this work, normalizing flows are used as flexible parameter distribution approximations having weights and biases . We specify the architecture used in each application by the number of real NVP affine coupling stages, and the number of neural network layers and units per layer of the conditioning functions.

When calculating Hessians of log probabilities in deep probability distributions, it is important to consider the normalizing flow architecture. With autoregressive architectures (Kingma et al., 2016; Papamakarios et al., 2017), fast sampling and fast log probability evaluations are mutually exclusive. That makes these architectures undesirable for EPI, where efficient sampling is important for optimization, and log probability evaluation speed predicates the efficiency of gradient and Hessian calculations. With real NVP coupling architectures, we get both fast sampling and fast Hessians making both optimization and scientific analysis efficient.

Maximum entropy distributions and exponential families

The inferred distribution of EPI is a maximum entropy distribution, which have fundamental links to exponential family distributions. A maximum entropy distribution of form:

| (16) |

where is the sufficient statistics vector and a vector of their mean values, will have probability density in the exponential family:

| (17) |

The mappings between the mean parameterization and the natural parameterization are formally hard to identify except in special cases (Wainwright and Jordan, 2008).

In this manuscript, emergent properties are defined by statistics having a fixed mean and variance as in Equation 12. The variance constraint is a second moment constraint on :

| (18) |

As a general maximum entropy distribution (Equation 16), the sufficient statistics vector contains both first and second order moments of

| (19) |

which are constrained to the chosen means and variances

| (20) |

Thus, is used to denote the mean parameter of the maximum entropy distribution defined by the emergent property (all constraints), while is only the mean of . The subscript ‘opt’ of is chosen since it contains all the constraint values to which the EPI optimization algorithm must adhere.

Augmented lagrangian optimization

To optimize in Equation 14, the constrained maximum entropy optimization is executed using the augmented lagrangian method. The following objective is minimized:

| (21) |

where there are average constraint violations

| (22) |

are the lagrange multipliers where is the number of total constraints

| (23) |

and is the penalty coefficient. The mean parameter and sufficient statistics are determined by the means and variances of the emergent property statistics defined in Equation 14. Specifically, is a concatenation of the first and second moments (Equation 19) and is a concatenation of their constraints and (Equation 20). (Although, note that this algorithm is written for general and to satisfy the more general class of emergent properties.) The lagrange multipliers are closely related to the natural parameters of exponential families (see Section 'EPI as variational inference'). Weights and biases of the deep probability distribution are optimized according to Equation 21 using the Adam optimizer with learning rate 10−3 (Kingma and Ba, 2015).

The gradient with respect to entropy can be expressed using the reparameterization trick as an expectation of the negative log density of parameter samples over the randomness in the parameterless initial distribution ):

| (24) |

Thus, the gradient of the entropy of the deep probability distribution can be estimated as an average of gradients with respect to the base distribution :

| (25) |

The gradients of the log density of the deep probability distribution are tractable through the use of normalizing flows (see Section 'Deep probability distributions and normalizing flows').

The full EPI optimization algorithm is detailed in Algorithm 1. The lagrangian parameters are initialized to zero and adapted following each augmented lagrangian epoch, which is a period of optimization with fixed (, ) for a given number of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) iterations. A low value of is used initially, and conditionally increased after each epoch based on constraint error reduction. The penalty coefficient is updated based on the result of a hypothesis test regarding the reduction in constraint violation. The p-value of is computed, and is updated to with probability . The other update rule is given a batch size and . Throughout the study, , while β was chosen to be either 2 or 4. The batch size of EPI also varied according to application.

| Algorithm 1. Emergent property inference |

|---|

| 1 initialize by fitting to an isotropic gaussian of mean and variance

2 initialize and . 3 for Augmented lagrangian epoch do 4 for SGD iteration do 5 Sample , get transformed variable , 6 Update by descending its stochastic gradient (using ADAM optimizer [Kingma and Ba, 2015]). 7 end 8 Sample , get transformed variable , 9 Update . 10 Update (see text for detail). 11 end |

In general, and should start at values encouraging entropic growth early in optimization. With each training epoch in which the update rule for is invoked, the constraint satisfaction terms are increasingly weighted, which generally results in decreased entropy (e.g. see Figure 1—figure supplement 1C). This encourages the discovery of suitable regions of parameter space, and the subsequent refinement of the distribution to produce the emergent property. The momentum parameters of the Adam optimizer are reset at the end of each augmented lagrangian epoch, which proceeds for iterations. In this work, we used a maximum number of augmented lagrangian epochs .

Rather than starting optimization from some drawn from a randomized distribution, we found that initializing to approximate an isotropic gaussian distribution conferred more stable, consistent optimization. The parameters of the gaussian initialization were chosen on an application-specific basis. Throughout the study, we chose isotropic Gaussian initializations with mean at the center of the support of the distribution and some variance , except for one case, where an initialization informed by random search was used (see Section 'Stomatogastric ganglion'). Deep probability distributions were fit to these gaussian initializations using 10,000 iterations of stochastic gradient descent on the evidence lower bound (as in Bittner and Cunningham, 2019) with Adam optimizer and a learning rate of .

To assess whether the EPI distribution produces the emergent property, we assess whether each individual constraint on the means and variances of is satisfied. We consider the EPI to have converged when a null hypothesis test of constraint violations being zero is accepted for all constraints at a significance threshold . This significance threshold is adjusted through Bonferroni correction according to the number of constraints . The p-values for each constraint are calculated according to a two-tailed nonparametric test, where 200 estimations of the sample mean are made using samples of at the end of the augmented lagrangian epoch. Of all augmented lagrangian epochs, we select the EPI inferred distribution as that which satisfies the convergence criteria and has greatest entropy.

When assessing the suitability of EPI for a particular modeling question, there are some important technical considerations. First and foremost, as in any optimization problem, the defined emergent property should always be appropriately conditioned (constraints should not have wildly different units). Furthermore, if the program is underconstrained (not enough constraints), the distribution grows (in entropy) unstably unless mapped to a finite support. If overconstrained, there is no parameter set producing the emergent property, and EPI optimization will fail (appropriately).

Example: 2D LDS

To gain intuition for EPI, consider a two-dimensional linear dynamical system (2D LDS) model (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A):

| (26) |

with

| (27) |

To run EPI with the dynamics matrix elements as the free parameters (fixing s), the emergent property statistics were chosen to contain parts of the primary eigenvalue of , which predicate frequency, , and the growth/decay, , of the system

| (28) |

is the eigenvalue of greatest real part when the imaginary component is zero, and alternatively that of positive imaginary component when the eigenvalues are complex conjugate pairs. To learn the distribution of real entries of that produce a band of oscillating systems around 1 Hz, we formalized this emergent property as having mean zero with variance , and the oscillation frequency having mean 1 Hz with variance 0.1 Hz2:

| (29) |

To write the emergent property in the form required for the augmented lagrangian optimization (Section 'Augmented lagrangian optimization'), we concatenate these first and second moment constraints into a vector of sufficient statistics and constraint values .

| (30) |

From now on in all scientific applications (Sections 'Stomatogastric ganglion', 'Scaling EPI for stable amplification in RNNs', 'Primary visual cortex', 'Superior colliculus'), we specify how the EPI optimization was setup by specifying , , and .

Unlike the models we presented in the main text, this model admits an analytical form for the mean emergent property statistics given parameter , since the eigenvalues can be calculated using the quadratic formula:

| (31) |

We study this example, because the inferred distribution is curved and multimodal, and we can compare the result of EPI to analytically derived contours of the emergent property statistics.

Despite the simple analytic form of the emergent property statistics, the EPI distribution in this example is not simply determined. Although is calculable directly via a closed form function, the distribution cannot be derived directly. This fact is due to the formally hard problem of the backward mapping: finding the natural parameters from the mean parameters of an exponential family distribution (Wainwright and Jordan, 2008). Instead, we used EPI to approximate this distribution (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B). We used a real NVP normalizing flow architecture three coupling layers and two-layer neural networks of 50 units per layer, mapped onto a support of . (see Section 'Deep probability distributions and normalizing flows').

Even this relatively simple system has nontrivial (although intuitively sensible) structure in the parameter distribution. To validate our method, we analytically derived the contours of the probability density from the emergent property statistics and values. In the - plane, the black line at , dashed black line at the standard deviation , and the dashed gray line at twice the standard deviation follow the contour of probability density of the samples (Figure 1—figure supplement 2A). The distribution precisely reflects the desired statistical constraints and model degeneracy in the sum of and . Intuitively, the parameters equivalent with respect to emergent property statistic have similar log densities.

To explain the bimodality of the EPI distribution, we examined the imaginary component of . When (which is the case on average in ), we have

| (32) |

In Figure 1—figure supplement 2B, we plot the contours of where is fixed to 0 at one standard deviation (, black dashed) and two standard deviations (, gray dashed) from the mean of . This validates the curved multimodal structure of the inferred distribution learned through EPI. Subtler combinations of model and emergent property will have more complexity, further motivating the use of EPI for understanding these systems. As we expect, the distribution results in samples of two-dimensional linear systems oscillating near 1 Hz (Figure 1—figure supplement 3).

EPI as variational inference

In variational inference, a posterior approximation is chosen from within some variational family to be as close as possible to the posterior under the KL divergence criteria

| (33) |

This KL divergence can be written in terms of entropy of the variational approximation:

| (34) |

| (35) |