Abstract

Understanding the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for developing effective treatment strategies. Viruses hijack the host metabolism to redirect the resources for their replication and survival. The influence of SARS-CoV-2 on host metabolism is yet to be fully understood. In this study, we analyzed the transcriptomic data obtained from different human respiratory cell lines and patient samples (nasopharyngeal swab, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, lung biopsy, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid) to understand metabolic alterations in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. We explored the expression pattern of metabolic genes in the comprehensive genome-scale network model of human metabolism, Recon3D, to extract key metabolic genes, pathways, and reporter metabolites under each SARS-CoV-2-infected condition. A SARS-CoV-2 core metabolic interactome was constructed for network-based drug repurposing. Our analysis revealed the host-dependent dysregulation of glycolysis, mitochondrial metabolism, amino acid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, glutathione metabolism, polyamine synthesis, and lipid metabolism. We observed different pro- and antiviral metabolic changes and generated hypotheses on how the host metabolism can be targeted for reducing viral titers and immunomodulation. These findings warrant further exploration with more samples and in vitro studies to test predictions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Transcriptomics, Redox homeostasis, Polyamine metabolism, Warburg effect, Host-pathogen interaction

Abbreviations

- A549_0.2

A549 cell line infected with a MOI of 0.2

- A549_2

A549 cell line infected with a MOI of 2

- ACE2

ACE2 transduced A549 cell line

- ACE2_0.2

ACE2 cell line infected with a MOI of 0.2

- ACE2_2

ACE2 cell line infected with a MOI of 2

- BALF

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BCAA

Branched-chain amino acid

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CDF

Cumulative distribution function

- 25HC

Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase

- DEG

Differentially expressed gene

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- FDA

Food and drug administration

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCoV-229E

Human coronavirus 229E

- HCMV

Human cytomegalovirus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- hPPiN

Human protein-protein interaction network

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- MERS-CoV

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus

- MOM

Mitochondrial outer membrane

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- NHBE

Normal human bronchial epithelial

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- RNASeq

RNA sequencing

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

1. Introduction

The ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease is a highly infectious respiratory illness in humans caused by a strain called Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1,2]. It was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan and has spread worldwide, infecting over 188 million people, and causing over 4 million deaths by July 2021. The World Health Organization has declared this ongoing pandemic as a global public health emergency. Most patients have one or more symptoms of fever, cough, shortness of breath, headache, lack of taste/smell, chest pain, and diarrhea, while in severe cases, patients develop severe pneumonia, pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or multiple organ failure leading to death [3]. The severity is attributed to dysregulation of immune function and host factors like comorbidities; however, their relative contributions are still unclear. It is critical to understand the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 for the design of effective treatment strategies.

Viruses’ life cycle involves entering a host, evading the host cell immune response, and viral replication by taking control of host-cellular machinery for protein synthesis. The host-virus protein-protein interaction network controls these processes. The mechanism for infecting hosts may vary depending upon the viral type. SARS-CoV-2 entry into a host cell depends on spike protein (S) binding to the receptor ACE2 and S protein priming by serine protease TMPRSS2 [4]. The viral entry into host cells is shown to be blocked by the serine protein inhibitor against TMPRSS2. Further, inhibitors based on the crystal structure of the main protease (Mpro, 3CLpro) of SARS-CoV-2 have been proposed as potential treatment strategies [5,6]. In addition to viral proteins, different host proteins can also serve as drug targets. The host-virus interactome-based drug repurposing strategies have shown great promise in identifying different host protein targets [7,8]. However, there is minimal knowledge of the mechanism of the SARS-CoV-2 survival strategy.

Due to their complete dependence on host cells to replicate, viruses may have evolved different strategies to reprogram the host metabolism for their replication and survival [[9], [10], [11], [12]]. Specific host metabolic pathways, including carbohydrate, fatty acid, and nucleotide metabolism, are known to be breached by different viruses upon infection. Each viral species is likely to induce unique metabolic reprogramming of the host cell. The host transcriptomic data in response to SARS-CoV-2 is helping to decipher the changes at the level of gene expression. Studies have shown elevated inflammatory cytokine production, low innate antiviral defense, autophagic and mitochondrial dysfunctions in SARS-CoV-2 infected conditions [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. However, a comprehensive understanding of metabolic reprogramming of the host by SARS-CoV-2 is still lacking.

In this study, we explored the metabolic alterations induced by the SARS-CoV-2 using the transcriptomic data obtained from different human respiratory cell lines and samples collected from patients. We identified metabolic hot-spots and reporter metabolites under various SARS-CoV-2-infected conditions and compared them to obtain robust metabolic changes. A host-virus metabolic interactome of SARS-CoV-2 was reconstructed. We also linked our findings to available proteomics and metabolomics data obtained under SARS-CoV-2 infected conditions. This analysis generates insights into host metabolic response to SARS-CoV-2, which can be targeted for the effective antiviral response.

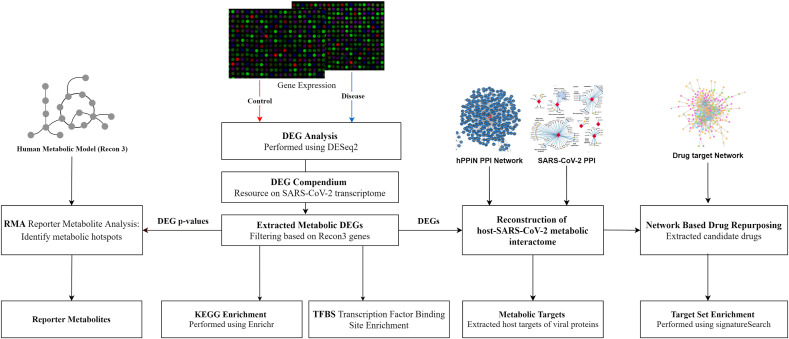

2. Methods

2.1. Host transcriptomic data

We generated insights into how the host metabolism is altered in response to SARS-CoV-2 by analyzing the RNA sequencing (RNASeq) raw read count data obtained from 4 human cell lines, including adenocarcinomic alveolar basal epithelial (A549) cells, ACE2 transduced A549 (ACE2) cells, human adenocarcinomic lung epithelial (Calu3) cells, and normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1 ) [13]. A549 and ACE2 cell lines were infected with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) equal to 0.2 and 2, whereas Calu3 and NHBE with a MOI of 2. We also used RNASeq raw read count data obtained from lung biopsy [13] and nasopharyngeal swab of healthy and SARS-CoV-2 infected human samples [16]. These datasets are available for download from the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database with accession numbers given in Table 1. The workflow used to analyze the host metabolic response to SARS-CoV-2 is shown in Fig. 1 .

Table 1.

Transcriptomics datasets used to study the metabolic response of the host to SARS-CoV-2.

|

Accession No. |

Cell Lines/Regions | Viral Load MOI | Description | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE147507 (GEO) | A549 | 0.2 | Human lung adenocarcinomic alveolar basal epithelial cells | Illumina NextSeq 500 |

| A549 | 2 | Human lung adenocarcinomic alveolar basal epithelial cells | ||

| ACE2 | 0.2 | A549 cells transduced with a vector expressing human ACE2 | ||

| ACE2 | 2 | A549 cells transduced with a vector expressing human ACE2 | ||

| Calu3 | 2 | Human adenocarcinomic lung epithelial cells | ||

| lung biopsy | N/A | Lung biopsy from human postmortem | ||

| NHBE | 2 | Primary human bronchial epithelial cells | ||

| GSE152075 (GEO) | swab | N/A | Human nasopharyngeal swab | Illumina NextSeq 500 |

| PRJCA002326 (BioProject) | BALF | N/A | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | Illumina HiSeq 2000 |

| PBMC | N/A | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells | MGISEQ-2000 and Illumina NovaSeq |

Fig. 1.

The workflow to study the host metabolic response and drug targeting.

2.2. Differential gene expression analysis

We performed differential gene expression analysis using the DESeq2 (v1.26.1) in R (v3.6.1) for various SARS-CoV-2 infected conditions (cell lines, lung biopsy, and nasopharyngeal swab) to obtain differentially expressed genes (DEGs) [17]. Further, we obtained DEGs of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) cells of SARS-CoV-2 patients from Xiong et al. (2020) (Table 1). To understand metabolism-specific alterations, we filtered the resulting DEGs based on the genes present in Recon3D, a comprehensive genome-scale network model of human metabolism [18]. We compared the DEGs across conditions and extracted key genes based on the number of occurrences to obtain robust gene signatures (“metagenes”). The KEGG pathways associated with DEGs were obtained using Enrichr (adjusted p-value < 0.05) [19]. We also identified transcription factors associated with metabolic DEGs under each condition using the TRUST transcription factor (2019) database in Enrichr (p-value < 0.05) [19] and extracted key transcription factors based on the number of occurrences.

2.3. Reporter metabolite analysis

The metabolic DEGs of SARS-CoV-2 were used to extract the reporter metabolites around which the most significant transcriptional changes occur [20]. This approach is based on the hypothesis that genes surrounding a metabolite are co-expressed to maintain homeostasis. Each metabolite is scored based on the gene expression of neighboring genes. We used the Recon3D model to identify the neighboring genes of each metabolite. The Recon3D model contains 10,600 metabolic reactions, 5835 metabolites, and 1882 unique metabolic genes spanning nine compartments. Based on the gene-protein-reaction association rules of the Recon3D model, genes associated with reactions involving a metabolite as a reactant or product were classified as the neighboring genes of that metabolite.

The p-values (p i) obtained from the differential gene expression analysis were transformed into the Z-scores (Z i) using the inverse normal cumulative distribution function (CDF). Metabolites were assigned a Z-score (Z metabolite) by aggregating the Z-scores of their ‘k’ neighboring genes (equation (1)).

| (1) |

These Z metabolite scores were corrected for the background distribution using mean (μ k) and standard deviation (σ k) of aggregated Z-scores obtained by sampling 10,000 sets of k enzymes from the network (equation (2)). Corrected Z-scores were then transformed to p-values using CDF. Metabolites with greater or equal to three neighboring genes (k ≥ 3) and p-values less than 0.05 were identified as reporter metabolites.

| (2) |

2.4. Reconstruction of host-SARS-CoV-2 metabolic interactome

We utilized a recent host-virus protein-protein interactome of SARS-CoV-2 (332 high-confidence interactions between 26 SARS-CoV-2 proteins) to extract the metabolic DEGs targeted by viral proteins [21]. In addition to direct interactions, we also retrieved the indirect metabolic targets present in the immediate neighborhood of all viral protein targets. We used high confidence and curated human protein-protein interaction network (hPPiN) containing 17,063 nodes and 208,760 interactions) to extract the immediate neighbors [22]. The final interactome size was 724 nodes (metabolic and non-metabolic) and 1018 interactions. The key metabolic processes that are targeted directly and indirectly by viral proteins were identified. Cytoscape version 3.3 was utilized to visualize the networks.

2.5. Network-based drug repurposing

Drug-target network of 2938 FDA-approved or investigational drugs constructed from databases including DrugBank database (v4.3), Therapeutic Target Database, PharmGKB database, ChEMBL (v20), BindingDB, and the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology was taken from Zhou et al. (2020) [[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]]. To identify the potential drugs, the proximity of the set of genes ‘C’ of SARS-CoV-2 metabolic interactome to the set of drug targets ‘T’ was measured as

| (3) |

where d(c,t) is the average shortest path length of the gene c ∈ C and t ∈ T [30]. The permutation test was performed with randomly selected genes with similar degree distributions of genes in C and T. Z-score was calculated as

| (4) |

where and are the mean and standard deviation obtained by sampling 1000 times. p-value was calculated based on the permutation test. Drugs with Z-score < −2.0 and p-value < 0.005 were considered significant. From these, we identified the drugs which target one or more upregulated metabolic DEGs. We further prioritized the drugs based on drug categories extracted from the DrugBank database [24] and available clinical trials information (https://clinicaltrials.gov/). Target set enrichment analysis of the identified drugs for KEGG pathways was performed by duplication adjusted hypergeometric test using Signature Search R package with q-value cut-off < 0.05 for false discovery rate control [31].

3. Results and discussion

We first compiled a compendium of all the changes that can serve as a useful resource on SARS-CoV-2 (Table S1). This information can be used to extract consensus and condition-specific genes (Fig. S1). Genes of cytokine-mediated signaling pathways are present in most infected conditions representing the adverse inflammatory condition (“cytokine storm”) as reported by different studies [13,14].

3.1. Metabolic changes in SARS-CoV-2 infected cell lines

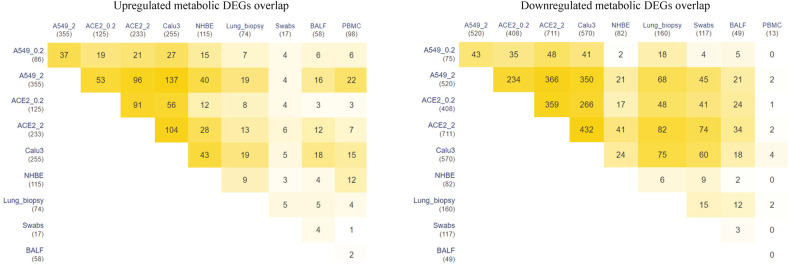

We specifically extracted metabolic alterations based on the genes in the genome-scale network model of human metabolism, Recon3D. The metabolic DEGs between normal and infected conditions (p-value < 0.05) is given in Table S2. In general, A549 and Calu3 have the most metabolic changes compared to other cell lines. The overlap of metabolic DEGs across different cell lines is shown in Fig. 2 . We observed that most metabolic DEGs are downregulated in ACE2, A549, and Calu3 cell lines compared to NHBE. There is also an increase in DEGs with an increase in MOI from 0.2 to 2 in ACE2 and A549 cell lines (ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, and A549_0.2, A549_2). Table 2 shows the top metabolic candidate genes upregulated in most infected conditions. We also identified metabolic pathways and reporter metabolites in each infected cell line.

Fig. 2.

Overlap of differentially expressed metabolic genes in different cell lines and patient samples with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Table 2.

Top metabolic genes (p-value < 0.05) upregulated in response to SARS-CoV-2. The number of occurrences of each gene in different host conditions is given along with the associated KEGG pathway.

| Gene | Occurrences | Samples | KEGG Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAMPT | 8 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy, swab | Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism |

| SAT1 | 8 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy, swab | Arginine and proline metabolism |

| SOD2 | 7 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy | FoxO signaling pathway |

| ASS1 | 6 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, Calu3, NHBE, BALF | Arginine biosynthesis |

| CMPK2 | 6 | A549_0.2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, lung biopsy, swab | Pyrimidine metabolism |

| PDE4B | 6 | A549_0.2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, lung biopsy, swab | cAMP signaling pathway |

| PTGS2 | 6 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE | Arachidonic acid metabolism |

| ABCA1 | 5 | A549_2, ACE2_2, Calu3, BALF, swab | Cholesterol metabolism |

| B4GALT1 | 5 | A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE | Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis |

| CSGALNACT1 | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE | Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis |

| DUOX2 | 5 | A549_2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, BALF | Thyroid hormone synthesis |

| EXT1 | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_2, Calu3, BALF | Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis |

| GCH1 | 5 | A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, lung biopsy | Folate biosynthesis |

| GPCPD1 | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism |

| TYMP | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE | Pyrimidine metabolism |

| KYNU | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE | Tryptophan metabolism |

| LAP3 | 5 | A549_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, PBMC | Arginine and proline metabolism |

| NT5E | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_2, Calu3, BALF | Pyrimidine metabolism |

| PTEN | 5 | A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, BALF | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway |

| SLC7A2 | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3 | – |

| SLC9A8 | 5 | A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, lung Biopsy | – |

| IREB2 | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3 | – |

3.2. Mitochondrial and glycolytic metabolism

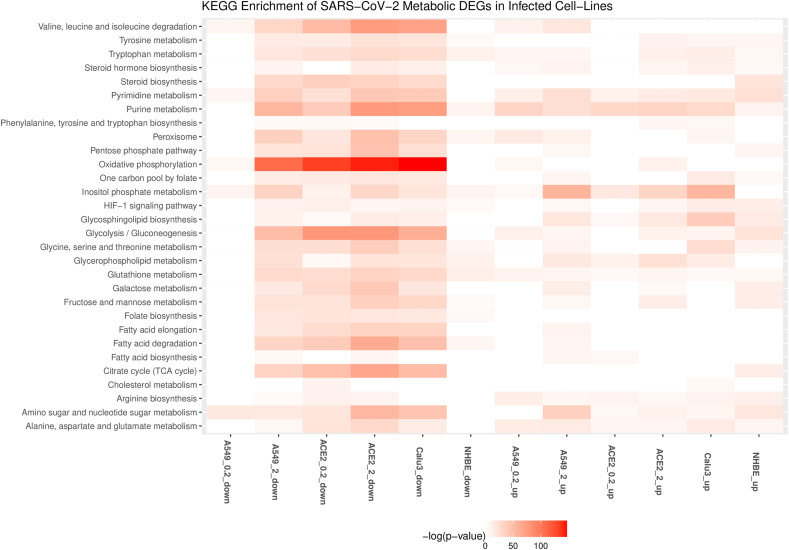

The enrichment of downregulated metabolic DEGs shows downregulation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation in most infected cell lines (Fig. 3 ). The ACE2 cell line shows mitochondrial dysfunction even at a low viral load (ACE2_0.2). Mitochondria are known to have a role in innate host immunity and can be targeted by invading microorganisms. The mitochondrial antiviral mechanism involves activation of the RLR signaling pathway and its target MAVS at the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM). MAVS recruits effectors at the MOM to form MAVS signalosome upon viral infection and control the activation of NFκB and IRF3 [32,33]. The inhibition of MAVS results in increased viral replication and the killing of host cells. MAVS is shown to be downregulated in SARS-CoV-2 infected Caco-2 cells [34]. The innate antiviral immunity is governed by the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) [35]. RLR antiviral signaling also depends on oxidative phosphorylation [36]. Many viruses that manipulate mitochondrial dynamics also alter the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway [37]. Therefore, further analysis is required to test whether mitochondrial dysfunction may lead to sustained inflammasome signaling in SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 3.

KEGG pathways associated with upregulated and downregulated metabolic genes in different cell lines with SARS-CoV-2 infection. A549 and A549-ACE2 is shown for MOI of 0.2 (A549_0.2, ACE2_0.2) and 2 (A549_2, ACE2_2). Up and down represent the upregulated and downregulated metabolic DEGs.

On the other hand, LDH family (LDHAL6A, LDHAL6B) genes involved in lactate production are significantly upregulated in ACE2_2. The lactate is a natural suppressor of antiviral RLR signaling by binding to the MAVS transmembrane domain [38,39]. In turn, RLR signaling is shown to suppress glycolysis by inhibiting the enzyme hexokinase HK2 [38]. We observed that HK2 is upregulated in A549_2, ACE2_2, NHBE, and Calu3 cell lines infected with a MOI equal to 2 (Table S2). HK2 also integrates energy metabolism and cell protection via Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and autophagy [40]. This mutual antagonism between RLR and glycolysis needs to be explored in SARS-CoV-2 infection [41] since some of the glycolytic genes TPI1, ENO1, PKM, PGAM1, GAPDH, and PFKL are downregulated in A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, and Calu3 cell lines. HKDC1, a member of the hexokinase family, and SLC2A1, a glucose transporter gene, are also upregulated in A549_2 and ACE2_2 cell lines infected with a MOI equal to 2. An inhibitor of hexokinase (2-deoxy-d-glucose) blocked SARS-CoV-2 replication in Caco-2 cells [34]. We observed that the genes of the HIF1 signaling pathway are both upregulated and downregulated in the SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome (Fig. 3). Some of its targets, such as VEGF, are upregulated in A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, and NHBE cell lines (Table S1). On the other hand, we found that VHL that targets HIF1A to degradation is also upregulated in these cell lines. HIF1A promotes a shift in mitochondrial metabolism to glycolysis [42]. It is also shown to promote SARS-CoV-2 replication in monocytes [43]. A proteo-transcriptomics analysis of SARS-CoV-2 infected Huh7 cells has shown dysregulation of Akt/mTOR/HIF1 signaling [44]. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is also known to control this switch in response to different viral infections [[45], [46], [47]]. Genes of PI3K controlled inositol phosphate metabolism are upregulated in A549_2, ACE2_2, and Calu3 cell lines infected with a MOI equal to 2 (Fig. 3). However, some genes of this pathway are also downregulated in these cell lines. We hypothesize that PI3K inhibitors Wortmannin and LY294002, which are known to have anti-cancer activity, maybe repurposed for SARS-CoV-2 antiviral therapy. These inhibitors are shown to inhibit the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) replication in vitro [48].

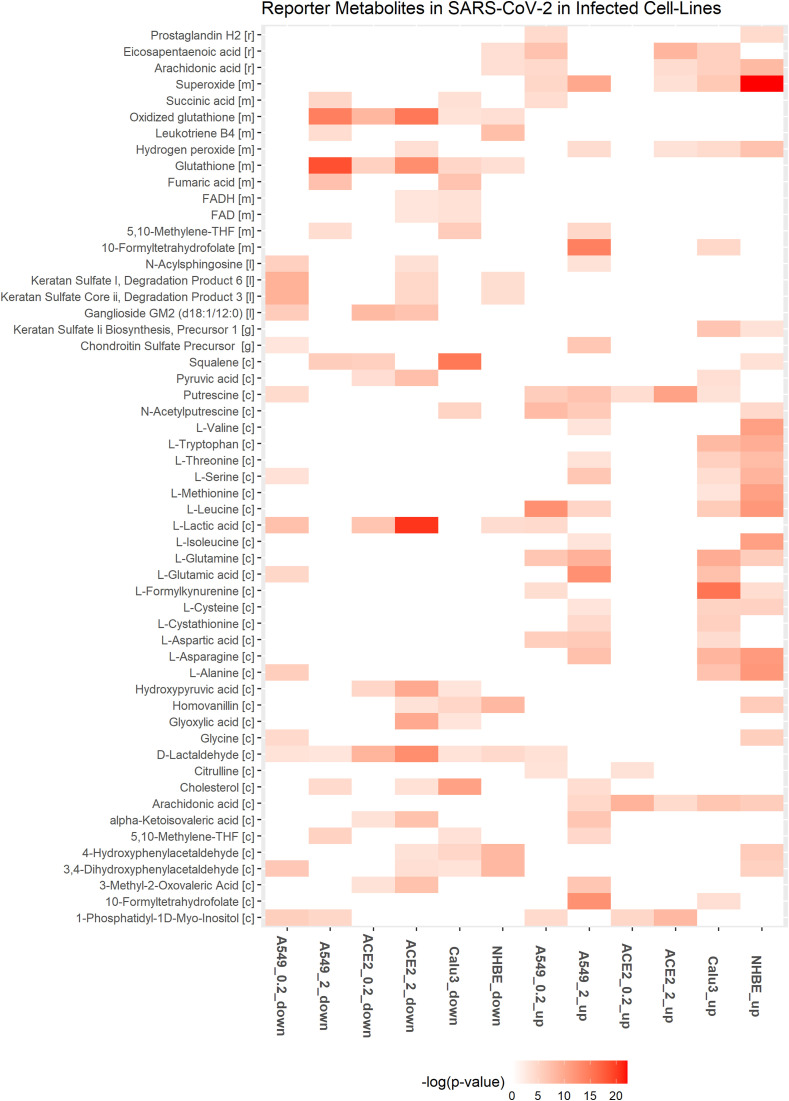

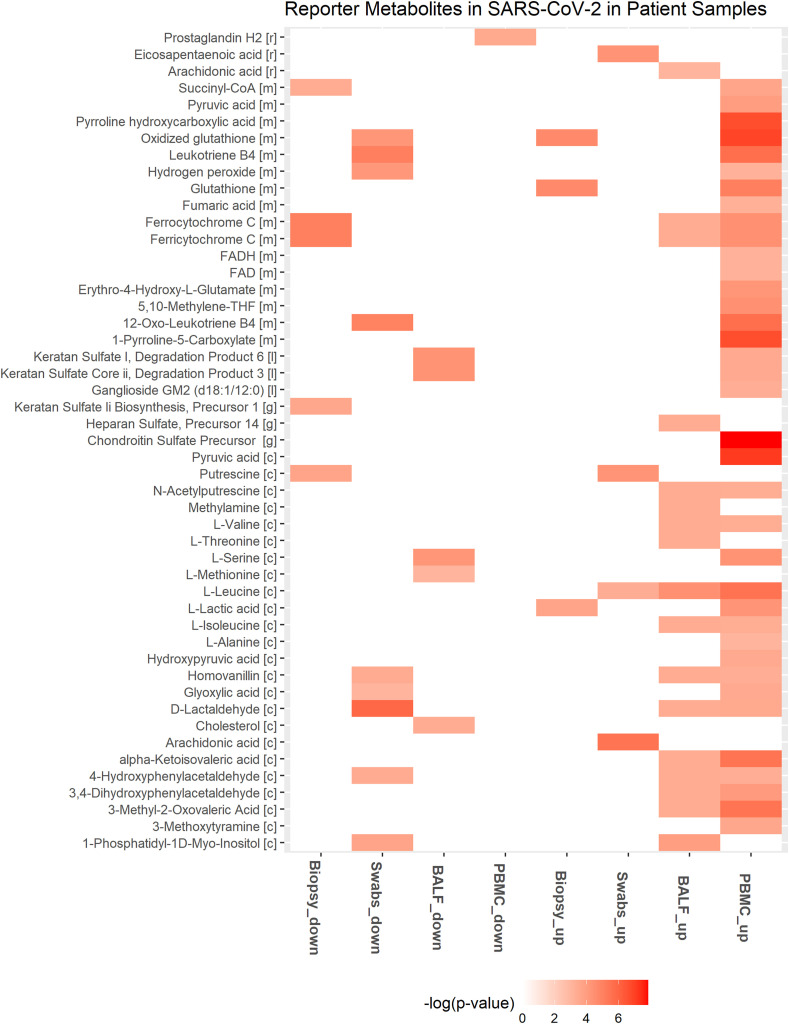

3.3. Amino acid metabolism

Genes involved in tryptophan catabolism (KYNU, KMO, IDO1) are upregulated in infected cell lines (Table 2 and Table S2). l-formylkynurenine of tryptophan metabolism is a reporter metabolite of infected conditions (Fig. 4 ). Metabolomics data from sera of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients show a decrease in tryptophan and an increase in the kynurenine pathway, which correlated with IL-6 levels [49]. IDO1-mediated tryptophan depletion, in the short term, is shown to inhibit viral replication but leads to immunosuppression in the long term [50].

Fig. 4.

Downregulated and upregulated reporter metabolites in at least two different cell lines with SARS-CoV-2 infection. A549 and ACE2 is shown for MOI of 0.2 (A549_0.2, ACE2_0.2) and 2 (A549_2, ACE2_2). Up and down represent the upregulated and downregulated metabolic DEGs.

ASS1 involved in de novo arginine synthesis from aspartate is upregulated in most infected cell lines (Table 2). Inhibition of ASS1 is shown to increase viral replication, and its deficiency affects immune cell activation [51,52]. These observations suggest that ASS1 is part of the antiviral pathway involved in the host defense. ASNS involved in the synthesis of asparaginase from aspartate is upregulated in A549 and Calu3 cell lines. Aspartic acid, asparaginase, and citrulline are reporter metabolites of infected conditions (Fig. 4). Asparaginase is found to be the novel host factor promoting the replication of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) [53]. Valine, leucine, and isoleucine (branched-chain amino acids, BCAAs) degradation pathway is also downregulated in infected cell lines (Fig. 3). The degradation of BCAAs generates CoA products that feed into the TCA cycle. l-isoleucine, l-leucine, l-valine, and alpha-ketoisovaleric acid are reporter metabolites of infected conditions (Fig. 4). BCAAs are reported to activate mTOR and interferon signaling by inactivating SOCS3 [54]. BCAA inhibits hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication and promotes infectious particle formation [55]. Serine, glutamine, and leucine are reporter metabolites in A549, Calu3, and NHBE cell lines (Fig. 4). The metabolites of homocysteine metabolism (l-cysteine and cystathionine) are also observed in A549 and Calu3.

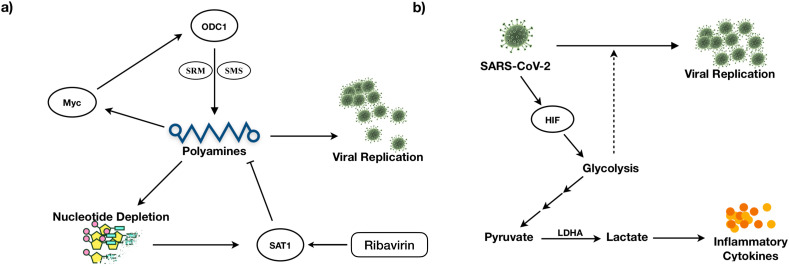

3.4. Polyamine metabolism

Genes that control polyamine levels are altered in infected cell lines (Tables 2 and S2). These include ODC1 and SAT1, which influence the polyamines’ synthesis and catabolism, respectively. SAT1 is upregulated in all the cell lines, while ODC1 is upregulated in ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, and A549_2. ODC1 is involved in the generation of putrescine, and SAT1 is involved in catabolizing spermine back to spermidine and putrescine. We found putrescine and N-acetylputrescine as reporter metabolites of infected conditions (Fig. 4). Polyamines are positively charged and bind DNA/RNA to assist in viral replication [56]. They help neutralize the negative charges of DNA and assist in packing DNA into viral particles [57,58]. Studies show that MERS-CoV is dependent on polyamines for replication [56]. Polyamines are known to control Myc expression, and Myc, in turn, controls the transcription of genes ODC1, SRM, and SMS involved in polyamine synthesis (positive feedback loop) [59] (Fig. 5 A). Therefore, the depletion of polyamines can be a strategy to reduce viral infection.

Fig. 5.

Feedback loop regulation of (A) Polyamine metabolism and (B) Glycolysis controls viral replication.

ODC1 inhibitor Difluoromethylornithine, which is in clinical trials for cancer treatment, can be tested for antiviral effects against SARS-CoV-2 [50,60]. Further, FDA-approved antiviral ribavirin depletes polyamines levels and viral titers by activating SAT1 [61]. Polyamine levels are regulated by a negative feedback loop involving SAT1 (Fig. 5A). Ribavirin is proposed as a novel coronavirus treatment strategy [62] and is also part of triple-antiviral therapy proposed for alleviating symptoms in mild to moderate SARS-CoV-2 conditions [63].

3.5. Nucleotide metabolism

Genes of purine and pyrimidine metabolism are mostly downregulated in A549_2, ACE2_2, and Calu3 cell lines (Fig. 3). GUK1 involved in converting guanosine monophosphate to guanosine diphosphate is downregulated in these cell lines. However, GUK1 is proposed as a bottleneck for the viral genome buildup and a drug target for SARS-CoV-2 [64]. CTPS genes involved in cytosine synthesis are downregulated in ACE2 and Calu3, while upregulated in A549_2 and NHBE cell lines. The proteomic study in Caco-2 cells shows that CTPS1 and CTPS2 are downregulated [34]. CDA, UPP1, UPB1, CMPK2, and TYMP involved in pyrimidine scavenging is upregulated in infected cell lines (Table S2). The compositional difference between human and SARS-CoV-2 RNA shows a deficiency of cytosine in SARS-CoV-2 [65]. CMPK2 is an interferon-stimulated gene known to restrict human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [66]. CMPK2 is found adjacent to gene RSAD2, which is well known to inhibit a wide variety of RNA and DNA viruses by synthesizing chain terminators that block DNA/RNA synthesis [67]. NT5E and XDH involved in purine catabolism are upregulated (Table S2). NT5E regulates the conversion of extracellular nucleotides to nucleosides that inhibit the immune response. In NAD metabolism, NAMPT involved in the salvage pathway for NAD synthesis is upregulated in all the infected cell line conditions. Although tryptophan catabolism is upregulated, QPRT involved in the intermediate generation for de novo synthesis of NAD synthesis from tryptophan is downregulated.

3.6. Lipid metabolism

Genes of fatty acid degradation and elongation are downregulated in most infected cell lines (Table S2). FASN involved in fatty acid synthesis is also downregulated. However, LPL involved in the hydrolysis of triacylglycerol is upregulated. Further, HMGCS1 and HMGCR involved in cholesterol synthesis from acetyl CoA are downregulated (A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, and Calu3), while the steroid hormone synthesis pathway from cholesterol is upregulated. Interestingly, CH25H involved in converting cholesterol to cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (25HC) is upregulated in ACE2_2 and Calu3 cell lines. CH25H is an interferon-regulated gene, and 25HC has an antiviral effect on HIV, Nipah virus, and Ebola by blocking the virus's membrane fusion [68]. Recently, CH25H is shown to suppress the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-mediated membrane fusion [69]. The analog of 25HC (7-hydroxycholesterol) is found to be upregulated in the sera of COVID-19 patients [70]. The distribution of cholesterol influences viral replication, entry, and budding [50]. The cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis are regulated by transcription factor SREBPs activated by a viral infection (HCV) through the PI3K/Akt pathway [71]. LDLR is also upregulated, which RNA viruses use to enter the host [72,73].

SGMS1 and SGMS2 involved in de novo synthesis of sphingolipids are upregulated in A549_2, ACE2_2, and Calu3 cell lines infected with a MOI equal to 2 (Table S2). In A549_2, SPTLC1, SPTLC2, CERS2, CERS5 and CERS6 are also upregulated. Further, genes of glycosphingolipid synthesis (B4GALT1, B3GNT5, B3GNT2) and glycerophospholipid metabolism (PLA2G4A, PLA2G4C, PLD1, PLD2) are also upregulated. Phospholipase 2 hydrolyzes membrane phospholipids to release arachidonic acid. PTGS2 involved in the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin is also upregulated. Both arachidonic acid and prostaglandin H2 are reporter metabolites of infected conditions (Fig. 4). HCV and dengue viruses depend on MAPK activated PLA2G4C to target core protein to lipid droplets [74]. Arachidonic acid is shown to suppress the replication of human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) and MERS-CoV [75].

3.7. Redox homeostasis

Genes of the pentose phosphate pathway and folate one-carbon metabolism are mostly downregulated in infected cell lines (Fig. 3 and Table S2). The cytoplasmic one-carbon metabolism genes DHFR, SHMT1, and MTHFD1 are downregulated in ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, A549_2, and Calu3, while mitochondrial genes MTHFD2 and MTHFD1L are upregulated in A549_2 and Calu3 cell lines. These pathways play an essential role in maintaining the redox balance by controlling NADPH production and nucleotide synthesis. Further, we observed that the genes of de novo synthesis of glutathione are also mostly downregulated (Fig. 3). These may reflect the oxidative stress condition of the host. Glutathione deficiency is also considered to be a severe manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 [76]. However, SOD2 involved in converting reactive oxygen species (ROS) to peroxides is upregulated in most infected cell lines (Table 2). Further, DUOX2 is upregulated in A549_2, ACE2_2, NHBE, and Calu3 cell lines infected with a MOI equal to 2. DUOX2 is usually expressed in epithelial tissues lining the respiratory and intestinal tracts and participates in the host defense against microbial infection at mucosal surfaces by the generation of peroxides [77,78]. DUOX2 is also an antiviral gene induced in response to cytokines [79,80]. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide are reporter metabolites in infected cell lines (Fig. 4).

3.8. Methyltransferases and heme catabolism

SETD2 and ASH1L that encode histone methyltransferases are upregulated in A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, and Calu3 cell lines. Methylation of STAT1 by SETD2 is shown to be critical for interferon antiviral activity [81]. Further, ASH1L also plays a role in suppressing TLR-mediated immune response [82]. The antiviral genes HMOX1 and HMOX2 are also downregulated [83,84] (Table S2). HMOX1 protects cells from programmed cell death by catabolizing free heme, and its induction can have a therapeutic effect [85]. HMOX1 knockout mice showed significantly higher cytokine responses, and its expression is required for the protection against inflammatory insult to the lung [84].

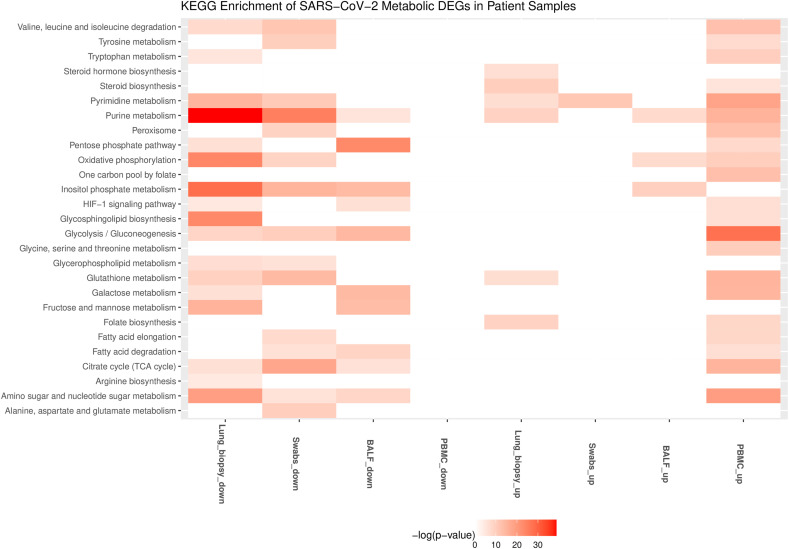

3.9. Metabolic changes in patient samples

The metabolic DEGs of lung biopsy, BALF, swab, and PBMC show some overlap with the cell line data but have a comparatively lesser overlap amongst themselves (Fig. 2). It can be noted that the patient samples may be heterogeneous with multiple cell types, including both infected and non-infected cells. The key metabolic genes (NAMPT, SAT1, SOD2, ASS1, CMPK2, DUOX2, PDE4B, ABCA1) in different SARS-CoV-2 infected cell lines are also upregulated in lung biopsy, swab, and BALF (Table 2). PDE4B modulates pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine productions by controlling cAMP levels and is proposed as an effective therapeutic target for many inflammatory diseases [86]. However, most metabolic DEGs are downregulated in swab and lung biopsy samples, while in PBMC, they are upregulated (Fig. 2). Genes of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation are downregulated in lung biopsy and swab samples and upregulated in PBMC (Fig. 6 and Table S2). We observed that glycolysis pathway (ENO1, GAPDH, TPI1, PKM, PGM2, HK1, LDHA) and primary transporter of glutamine (SLC1A5) are also upregulated in PBMC (Table S2). These alterations resemble the condition of aerobic glycolysis termed the “Warburg effect”, a hallmark of cancer. However, the observed metabolic changes in PBMC may be linked to the immune response, which is known to trigger a switch to aerobic glycolysis. Lactate is shown to influence cytokine production [87,88]. Interestingly, Codo et al. (2020) showed that SARS-CoV-2 stimulates glycolysis and that glycolysis promotes SARS-CoV-2 replication in monocytes and macrophages [43]. However, the single-cell transcriptomic data of PBMC from patients did not show viral reads [14,89]. On the other hand, SARS-CoV-2 is detected in monocytes and lymphocytes from patients, which increased over time from the onset of the disease [90]. Further study is required to understand whether the positive feedback loop between SARS-CoV-2 and glycolysis in immune cells leads to cytokine storm and disease severity (Fig. 5B). This metabolic adaptation may be mediated by mitochondrial ROS production and HIF1A stabilization, which controls the switch to aerobic glycolysis [43]. In PBMC, genes of folate metabolism (SHMT1, MTHFD2) are upregulated along with CAT, PRDX, and GPX1 involved in eliminating peroxides (Table S2). Further, genes involved in BCAA degradation are upregulated. The first step of BCAA degradation (BCAT1) is shown to induce metabolic reprogramming to combat ROS [91]. The metabolites of tyrosine metabolism (homovanillin and 3- methoxytyramine) are also upregulated in PBMC (Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 6.

KEGG pathways associated with upregulated and downregulated metabolic genes in different patient samples with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Up and down represent the upregulated and downregulated metabolic DEGs.

Fig. 7.

Downregulated and upregulated reporter metabolites in different patient samples with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Up and down represent the upregulated and downregulated metabolic DEGs.

3.10. Transcriptional regulation of metabolism

To understand the transcriptional regulation of metabolism, we identified the potential transcription factors based on DEGs’ binding site enrichment under each condition. We found that an overlapping set of transcription factors is associated with upregulated and downregulated genes in different infected conditions (Table 3, Table 4 ). These include transcription factors of the NFκB family (RELA, NFKB1), which control the transcription of host immune response. NFκB is activated by different viruses, including HCV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), HIV, and influenza virus [92], which helps in viral replication and suppressing host cell death. Transcription factors HIF1A, NFE2L2/NRF2, PPARA, and SERBF1 are also associated with differentially expressed genes. NFE2L2 is involved in oxidative stress, while SERBF1 and PPARA are involved in lipid homeostasis [93,94]. PPARA stimulation by DNA virus infection suppresses the interferon signaling and impairs immunity against the virus [95]. PPAR controls peroxisome metabolism, which is shown to be essential for different viruses. We observed that the peroxisome function is altered in different cell lines and human samples (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Transcription factor (TF) significantly (p-value < 0.05) associated with upregulated metabolic DEGs. The number of occurrences of each TF in different host conditions is given.

| TF | Occurrences | Samples |

|---|---|---|

| SP1 | 9 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy, BALF, PBMC |

| HIF1A | 8 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, BALF, PBMC |

| USF1 | 8 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, lung biopsy, BALF, PBMC |

| NFKB1 | 8 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy, swab |

| RELA | 8 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy, swab |

| PPARA | 7 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy |

| USF2 | 7 | A549_0.2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, lung biopsy, swab, BALF |

| PPARG | 7 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy |

| NR0B2 | 7 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, PBMC |

Table 4.

Transcription factor (TF) significantly (p-value < 0.05) associated with downregulated metabolic DEGs. The number of occurrences of each TF in different host conditions is given.

| TF | Occurrences | Samples |

|---|---|---|

| SP1 | 8 | A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, swab, BALF, PBMC |

| NFE2L2 | 7 | A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, NHBE, lung biopsy, swab |

| SREBF1 | 6 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3, lung biopsy |

| SMARCA4 | 5 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, BALF |

| NFYC | 4 | A549_0.2, A549_2, ACE2_0.2, PBMC |

| PPARG | 4 | A549_2, ACE2_2, NHBE, PBMC |

| NRF1 | 4 | A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3 |

| SREBF2 | 4 | A549_2, ACE2_0.2, ACE2_2, Calu3 |

| PPARA | 4 | ACE2_2, NHBE, lung biopsy, PBMC |

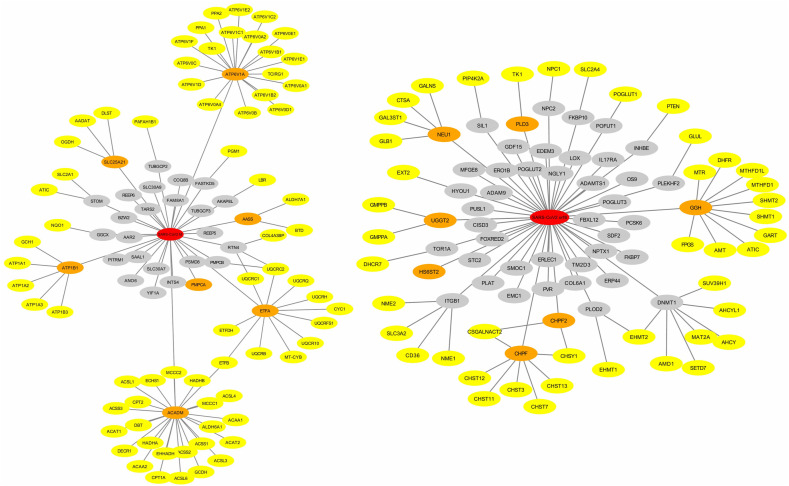

3.11. SARS-CoV-2 core metabolic interactome

The host-pathogen interactome of SARS-CoV-2 was used to identify the direct and indirect metabolic targets of viral proteins (Fig. 8 and S2). We found that viral proteins target the host mitochondrial metabolism (MPro, Nsp7, Orf9c), purine and pyrimidine synthesis (Nsp1, Nsp14), glutathione metabolism and oxidative stress (Nsp5_C145A, Orf3a), lipid metabolism (MPro, Nsp2, Nsp7, Orf10), folate metabolism (N, Orf8), chondroitin biosynthesis (Orf8) and prostaglandin biosynthesis (Nsp7). SARS-CoV-2 proteins also target a group of metabolic genes through HDAC2 (Nsp5), GNG5 (Nsp7), GNB1 (Nsp7), COMT (Nsp7), PRKACA (Nsp13), TBK1 (Nsp13), GLA (Nsp14), IMPDH2 (Nsp14), CSNK2B (N) and CSNK2A2 (N). G-protein subunits GNG5 and GNB1 control the PI3K/Akt pathway's activation by directly targeting the PI3K subunits.

Fig. 8.

Protein-protein interaction of viral proteins MPro (left) and Orf8 (right) with the host metabolic proteins. Viral proteins are shown in red color. Metabolic DEGs interacting directly and indirectly with viral proteins are shown in orange and yellow colors, respectively. Non-metabolic genes are shown in the grey color.

3.12. Drug repurposing using SARS-CoV-2 core metabolic interactome

The SARS-CoV-2 metabolic interactome was used to identify potential drugs that can have therapeutic effects against the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Drug targets that are in the vicinity of this network were identified using a network proximity measure. We identified 288 drugs (Z-score < −2.0 and p-value < 0.005) that target one or more upregulated metabolic DEGs in infected cell lines (Table S3). Targets of these 288 drugs are associated with nucleotide metabolism, amino acid metabolism (arginine, proline, histidine, tyrosine, and phenylalanine metabolism), and lipid metabolism (arachidonic acid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, and steroid hormone biosynthesis) (Table S4). We further prioritized drugs based on antiviral activity and clinical trial information.

The candidate drugs against SARS-CoV-2 include an anti-HIV agent Miglustat that inhibits UGCG, which is upregulated in A549_2, ACE2_2, and Calu3 cell lines. It encodes an enzyme involved in the synthesis of glycosphingolipids, which are membrane components. Our observation is consistent with the experiment that the inhibition of UGCG diminished SARS-CoV-2 viral entry [96]. The host glycans influence the binding to the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein on SARS-CoV-2, and a disruption in the synthesis of glycans can reduce viral infection. Further, Miglustat is also shown to have antiviral activity at the post-entry level leading to a decrease in viral proteins and the release of the virus [97]. The cellular membrane plays an important role in establishing a compartment for the synthesis of the viral genome. UGCG inhibitors Genz-123346, an analog of the drug Cerdelga, and GENZ-667161, an analog of the drug Venglustat, are shown to block SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro [98]. In addition to depleting membrane cholesterol, these observations suggest that drugs targeting glycan synthesis are promising candidates for drug repurposing.

We identified Pentoxifylline that targets NT5E in the nucleotide metabolism and PDE4 as a candidate drug against SARS-CoV-2. Eight genes encoding phosphodiesterase are upregulated in at least two infected cell lines (A549, ACE2, and Calu3) (Table S2). Pentoxifylline inhibits the replication of several viruses in vitro and has anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and bronchodilatory effects [99]. It is in clinical trials as adjuvant therapy for SARS-CoV-2 (NCT04433988) [100]. Other phosphodiesterase inhibitors identified include Ibudilast, Sildenafil, and Dipyridamole, which are in clinical trials for SARS-CoV-2 treatment (NCT04429555) [101].

PTGS1 and PTGS2 inhibitors are also candidate drugs against SARS-CoV-2. These include anti-inflammatory drugs Naproxen, Niflumic acid, Nimesulide, and Balsalazide, used in treating inflammatory bowel disease and pomalidomide, an immunomodulating antineoplastic agent. Naproxen is currently in clinical trials for treating critically ill hospitalized patients for SARS-CoV-2 infection (NCT04325633) [102]. We found drugs targeting LTA4H and ALOX5 involved in the biosynthesis of leukotriene as potential candidates. These include Captopril and Ubenimex that target LTA4H, and Zileuton, an anti-inflammatory agent that inhibits ALOX5. Captopril is currently in clinical trials for treating SARS-CoV-2 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome and pneumonia (NCT04355429) [103]. By targeting the biosynthesis of leukotrienes, these drugs may mitigate the hyperinflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 [104]. Further, Acetazolamide that inhibits carbonic anhydrases is also identified by this network approach. Inhibiting carbonic anhydrases is shown to affect the intracellular pH, which can disrupt virus-endosome fusion and lysosomal proteases [105]. However, there is a risk of multiple adverse effects using Acetazolamide for treating SARS-CoV-2 [106].

4. Conclusions

In summary, we performed a comprehensive comparison of several transcriptomic data and generated hypotheses into how the host metabolic pathway is hijacked in response to SARS-CoV-2. Our analysis based on the gene expression has revealed interesting metabolic genes and co-expression patterns that are unique, common, and depend on the viral load (MOI). We observed different pro- and antiviral metabolic changes, where a shift in this balance may play a role in disease pathogenesis. We provided a mechanistic view of how viral metabolism can be targeted for reducing viral titers. The metabolic network-based analysis helped identify interesting drugs with antiviral and immunomodulatory properties that can be repurposed to treat SARS-CoV-2. These findings warrant further exploration with the collection of more samples to increase the statistical significance and in vitro studies to test predictions. The gene expression-based prediction of metabolic changes needs to be further refined with proteomic and metabolomic data. As a first step, we have specifically explored metabolic gene expression changes in different SARS-CoV-2 infected cell lines and patient samples. Multi-omics data can be integrated with the genome-scale metabolic model to obtain cell line- and patient-specific flux level changes. The flux level change may be further constrained by a virus biomass equation that needs to be appropriately modeled for SARS-CoV-2 since it can lead to different results [64,107]. A further study with single-cell sequencing data of patients may help to refine the understanding on SARS-CoV-2 metabolic response.

Funding

PKV and UDP acknowledge financial support from the DST-Science and Engineering Research Board (CVD/2020/00034), India; Intel Corporation's Pandemic Response Technology Initiative (PRTI).

Data availability statement

All datasets reported in this study are publicly available.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105114.

Author statement

S T R Moolamalla: Data curation, Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Rami Balasubramanian: Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Ruchi Chauhan: Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - review & editing.

U Deva Priyakumar: Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Writing - review & editing.

P K Vinod: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Fig. S1: Overlap of differentially expressed genes in different cell lines and patient samples with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Fig. S2: Protein-protein interaction of viral proteins with the host metabolic proteins. Viral proteins are shown in red color. Metabolic DEGs interacting directly and indirectly with viral proteins are shown in orange and yellow colors, respectively. Non-metabolic genes are shown in the grey color.

Table S1: Differentially expressed genes in response to SARS-CoV-2 in different cell lines and patient samples (xlsx file).

Table S2: Differentially expressed metabolic genes in response to SARS-CoV-2 in different cell lines and patient samples (xlsx file).

Table S3: Drugs that target one or more metabolic DEGs (Z-score < -2.0 and p-value < 0.005) identified using the network proximity analysis (xlsx file).

Table S4: KEGG pathway enrichment of drug targets (q-value cut-off < 0.05) (xlsx file).

References

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benvenuto D., Giovanetti M., Ciccozzi A., Spoto S., Angeletti S., Ciccozzi M. The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: evidence for virus evolution. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:455–459. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Kruger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai W., Zhang B., Jiang X.M., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., et al. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science. 2020;368:1331–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mengist H.M., Fan X., Jin T. Designing of improved drugs for COVID-19: crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease M(pro) Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2020;5:67. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0178-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deisy Morselli Gysi Í.D.V., Zitnik Marinka, Ameli Asher, Gan Xiao, Varol Onur, Sanchez Helia, Baron Rebecca Marlene, Ghiassian Dina, Joseph Loscalzo, Barabási Albert-László. Network medicine framework for identifying drug repurposing opportunities for COVID-19. arXiv:200407229. 2020 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2025581118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng F., Desai R.J., Handy D.E., Wang R., Schneeweiss S., Barabasi A.L., et al. Network-based approach to prediction and population-based validation of in silico drug repurposing. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2691. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05116-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thaker S.K., Ch'ng J., Christofk H.R. Viral hijacking of cellular metabolism. BMC Biol. 2019;17:59. doi: 10.1186/s12915-019-0678-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer K.A., Stockl J., Zlabinger G.J., Gualdoni G.A. Hijacking the supplies: metabolism as a novel facet of virus-host interaction. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1533. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno-Altamirano M.M.B., Kolstoe S.E., Sanchez-Garcia F.J. Virus control of cell metabolism for replication and evasion of host immune responses. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2019;9:95. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez E.L., Lagunoff M. Viral activation of cellular metabolism. Virology. 2015;479–480:609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanco-Melo D., Nilsson-Payant B.E., Liu W.C., Uhl S., Hoagland D., Moller R., et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:1036–10345 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong Y., Liu Y., Cao L., Wang D., Guo M., Jiang A., et al. Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2020;9:761–770. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1747363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh K., Chen Y.-C., Judy J.T., Seifuddin F., Tunc I., Pirooznia M. Network analysis and transcriptome profiling identify autophagic and mitochondrial dysfunctions in SARS-CoV-2 infection. bioRxiv. 2020:2020. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.599261. 05.13.092536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieberman N.A.P., Peddu V., Xie H., Shrestha L., Huang M.L., Mears M.C., et al. In vivo antiviral host transcriptional response to SARS-CoV-2 by viral load, sex, and age. PLoS Biol. 2020;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunk E., Sahoo S., Zielinski D.C., Altunkaya A., Drager A., Mih N., et al. Recon3D enables a three-dimensional view of gene variation in human metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:272–281. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuleshov M.V., Jones M.R., Rouillard A.D., Fernandez N.F., Duan Q., Wang Z., et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:W90–W97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patil K.R., Nielsen J. Uncovering transcriptional regulation of metabolism by using metabolic network topology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:2685–2689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406811102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon D.E., Jang G.M., Bouhaddou M., Xu J., Obernier K., White K.M., et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020;583:459–468. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambarey A., Devaprasad A., Baloni P., Mishra M., Mohan A., Tyagi P., et al. Meta-analysis of host response networks identifies a common core in tuberculosis. NPJ systems biology and applications. 2017;3:4. doi: 10.1038/s41540-017-0005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y., Hou Y., Shen J., Mehra R., Kallianpur A., Culver D.A., et al. A network medicine approach to investigation and population-based validation of disease manifestations and drug repurposing for COVID-19. PLoS Biol. 2020;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wishart D.S., Knox C., Guo A.C., Shrivastava S., Hassanali M., Stothard P., et al. DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34:D668–D672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen X., Ji Z.L., Chen Y.Z. TTD: therapeutic target database. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:412–415. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorn C.F., Klein T.E., Altman R.B. PharmGKB: the pharmacogenomics knowledge base. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1015:311–320. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-435-7_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaulton A., Bellis L.J., Bento A.P., Chambers J., Davies M., Hersey A., et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D1100–D1107. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu T., Lin Y., Wen X., Jorissen R.N., Gilson M.K. BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:D198–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawson A.J., Sharman J.L., Benson H.E., Faccenda E., Alexander S.P., Buneman O.P., et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng F., Lu W., Liu C., Fang J., Hou Y., Handy D.E., et al. A genome-wide positioning systems network algorithm for in silico drug repurposing. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3476. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10744-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duan Y., Evans D.S., Miller R.A., Schork N.J., Cummings S.R., Girke T. signatureSearch: environment for gene expression signature searching and functional interpretation. Nucleic acids research. 2020;48:e124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seth R.B., Sun L., Ea C.K., Chen Z.J. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell. 2005;122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Refolo G., Vescovo T., Piacentini M., Fimia G.M., Ciccosanti F. Mitochondrial interactome: a focus on antiviral signaling pathways. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2020;8:8. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bojkova D., Klann K., Koch B., Widera M., Krause D., Ciesek S., et al. Proteomics of SARS-CoV-2-infected host cells reveals therapy targets. Nature. 2020;583:469–472. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koshiba T. Mitochondrial-mediated antiviral immunity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshizumi T., Imamura H., Taku T., Kuroki T., Kawaguchi A., Ishikawa K., et al. RLR-mediated antiviral innate immunity requires oxidative phosphorylation activity. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5379. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05808-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holley C.L., Schroder K. The rOX-stars of inflammation: links between the inflammasome and mitochondrial meltdown. Clinical & translational immunology. 2020;9 doi: 10.1002/cti2.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W., Wang G., Xu Z.G., Tu H., Hu F., Dai J., et al. Lactate is a natural suppressor of RLR signaling by targeting MAVS. Cell. 2019;178:176–189 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren Z., Ding T., Zuo Z., Xu Z., Deng J., Wei Z. Regulation of MAVS expression and signaling function in the antiviral innate immune response. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1030. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts D.J., Miyamoto S. Hexokinase II integrates energy metabolism and cellular protection: akting on mitochondria and TORCing to autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:248–257. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoolman J.S., Chandel N.S. Glucose metabolism linked to antiviral responses. Cell. 2019;178:10–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dodd K.M., Yang J., Shen M.H., Sampson J.R., Tee A.R. mTORC1 drives HIF-1alpha and VEGF-A signalling via multiple mechanisms involving 4E-BP1, S6K1 and STAT3. Oncogene. 2015;34:2239–2250. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Codo A.C., Davanzo G.G., Monteiro L.B., de Souza G.F., Muraro S.P., Virgilio-da-Silva J.V., et al. Elevated glucose levels favor SARS-CoV-2 infection and monocyte response through a HIF-1alpha/Glycolysis-Dependent Axis. Cell Metabol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Appelberg S., Gupta S., Svensson Akusjarvi S., Ambikan A.T., Mikaeloff F., Saccon E., et al. Dysregulation in Akt/mTOR/HIF-1 signaling identified by proteo-transcriptomics of SARS-CoV-2 infected cells. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2020;9:1748–1760. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1799723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mannova P., Beretta L. Activation of the N-Ras-PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway by hepatitis C virus: control of cell survival and viral replication. J. Virol. 2005;79:8742–8749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8742-8749.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin S., Saha B., Riley J.L. The battle over mTOR: an emerging theatre in host-pathogen immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su M.A., Huang Y.T., Chen I.T., Lee D.Y., Hsieh Y.C., Li C.Y., et al. An invertebrate Warburg effect: a shrimp virus achieves successful replication by altering the host metabolome via the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kindrachuk J., Ork B., Hart B.J., Mazur S., Holbrook M.R., Frieman M.B., et al. Antiviral potential of ERK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling modulation for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection as identified by temporal kinome analysis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2015;59:1088–1099. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03659-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas T., Stefanoni D., Reisz J.A., Nemkov T., Bertolone L., Francis R.O., et al. COVID-19 infection alters kynurenine and fatty acid metabolism, correlating with IL-6 levels and renal status. JCI insight. 2020;5 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raniga K., Liang C. Interferons: reprogramming the metabolic network against viral infection. Viruses. 2018;10 doi: 10.3390/v10010036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grady S.L., Purdy J.G., Rabinowitz J.D., Shenk T. Argininosuccinate synthetase 1 depletion produces a metabolic state conducive to herpes simplex virus 1 infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:E5006–E5015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321305110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarasenko T.N., Gomez-Rodriguez J., McGuire P.J. Impaired T cell function in argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015;97:273–278. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1AB0714-365R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee C.H., Griffiths S., Digard P., Pham N., Auer M., Haas J., et al. Asparagine deprivation causes a reversible inhibition of human cytomegalovirus acute virus replication. mBio. 2019;10 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01651-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Honda M., Takehana K., Sakai A., Tagata Y., Shirasaki T., Nishitani S., et al. Malnutrition impairs interferon signaling through mTOR and FoxO pathways in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:128–140. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.051. 40 e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ishida H., Kato T., Takehana K., Tatsumi T., Hosui A., Nawa T., et al. Valine, the branched-chain amino acid, suppresses hepatitis C virus RNA replication but promotes infectious particle formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;437:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mounce B.C., Olsen M.E., Vignuzzi M., Connor J.H. Polyamines and their role in virus infection. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. : MMBR (Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.) 2017;81 doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00029-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lightfoot H.L., Hall J. Endogenous polyamine function--the RNA perspective. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:11275–11290. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lanzer W., Holowczak J.A. Polyamines in vaccinia virions and polypeptides released from viral cores by acid extraction. Journal of virology. 1975;16:1254–1264. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.5.1254-1264.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Firpo M.R., Mounce B.C. Diverse functions of polyamines in virus infection. Biomolecules. 2020;10 doi: 10.3390/biom10040628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mounce B.C., Poirier E.Z., Passoni G., Simon-Loriere E., Cesaro T., Prot M., et al. Interferon-induced spermidine-spermine acetyltransferase and polyamine depletion restrict zika and chikungunya viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tate P.M., Mastrodomenico V., Mounce B.C. Ribavirin induces polyamine depletion via nucleotide depletion to limit virus replication. Cell Rep. 2019;28:2620–26233 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khalili J.S., Zhu H., Mak N.S.A., Yan Y., Zhu Y. Novel coronavirus treatment with ribavirin: groundwork for an evaluation concerning COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:740–746. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hung I.F., Lung K.C., Tso E.Y., Liu R., Chung T.W., Chu M.Y., et al. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Renz A., Widerspick L., Drager A. FBA reveals guanylate kinase as a potential target for antiviral therapies against SARS-CoV-2. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:i813–i821. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Danchin A., Marliere P. Cytosine drives evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Environ. Microbiol. 2020;22:1977–1985. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.El-Diwany R., Soliman M., Sugawara S., Breitwieser F., Skaist A., Coggiano C., et al. CMPK2 and BCL-G are associated with type 1 interferon-induced HIV restriction in humans. Science advances. 2018;4 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat0843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gizzi A.S., Grove T.L., Arnold J.J., Jose J., Jangra R.K., Garforth S.J., et al. A naturally occurring antiviral ribonucleotide encoded by the human genome. Nature. 2018;558:610–614. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu S.Y., Aliyari R., Chikere K., Li G., Marsden M.D., Smith J.K., et al. Interferon-inducible cholesterol-25-hydroxylase broadly inhibits viral entry by production of 25-hydroxycholesterol. Immunity. 2013;38:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zang R., Case J.B., Yutuc E., Ma X., Shen S., Gomez Castro M.F., et al. Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase suppresses SARS-CoV-2 replication by blocking membrane fusion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2020;117:32105–32113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012197117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shen B., Yi X., Sun Y., Bi X., Du J., Zhang C., et al. Proteomic and metabolomic characterization of COVID-19 patient sera. Cell. 2020;182:59–72 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jackel-Cram C., Qiao L., Xiang Z., Brownlie R., Zhou Y., Babiuk L., et al. Hepatitis C virus genotype-3a core protein enhances sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 activity through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-2 pathway. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:1388–1395. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.017418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Finkelshtein D., Werman A., Novick D., Barak S., Rubinstein M. LDL receptor and its family members serve as the cellular receptors for vesicular stomatitis virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:7306–7311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214441110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Molina S., Castet V., Fournier-Wirth C., Pichard-Garcia L., Avner R., Harats D., et al. The low-density lipoprotein receptor plays a role in the infection of primary human hepatocytes by hepatitis C virus. J. Hepatol. 2007;46:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Menzel N., Fischl W., Hueging K., Bankwitz D., Frentzen A., Haid S., et al. MAP-kinase regulated cytosolic phospholipase A2 activity is essential for production of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan B., Chu H., Yang D., Sze K.H., Lai P.M., Yuan S., et al. Characterization of the lipidomic profile of human coronavirus-infected cells: implications for lipid metabolism remodeling upon coronavirus replication. Viruses. 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/v11010073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Polonikov A. Endogenous deficiency of glutathione as the most likely cause of serious manifestations and death in COVID-19 patients. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Joo J.H., Ryu J.H., Kim C.H., Kim H.J., Suh M.S., Kim J.O., et al. Dual oxidase 2 is essential for the toll-like receptor 5-mediated inflammatory response in airway mucosa. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2012;16:57–70. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Geiszt M., Witta J., Baffi J., Lekstrom K., Leto T.L. Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources supporting mucosal surface host defense. Faseb. J. : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2003;17:1502–1504. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1104fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fink K., Martin L., Mukawera E., Chartier S., De Deken X., Brochiero E., et al. IFNbeta/TNFalpha synergism induces a non-canonical STAT2/IRF9-dependent pathway triggering a novel DUOX2 NADPH oxidase-mediated airway antiviral response. Cell Res. 2013;23:673–690. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grandvaux N., Mariani M., Fink K. Lung epithelial NOX/DUOX and respiratory virus infections. Clin. Sci. 2015;128:337–347. doi: 10.1042/CS20140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen K., Liu J., Liu S., Xia M., Zhang X., Han D., et al. Methyltransferase SETD2-mediated methylation of STAT1 is critical for interferon antiviral activity. Cell. 2017;170:492–506 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xia M., Liu J., Wu X., Liu S., Li G., Han C., et al. Histone methyltransferase Ash1l suppresses interleukin-6 production and inflammatory autoimmune diseases by inducing the ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20. Immunity. 2013;39:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu Y., Luo S., Sabo Y., Wang C., Tong L., Goff S.P. Heme oxygenase 2 binds myristate to regulate retrovirus assembly and TLR4 signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Soota K., Maliakkal B. Ribavirin induced hemolysis: a novel mechanism of action against chronic hepatitis C virus infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16184–16190. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gozzelino R., Jeney V., Soares M.P. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010;50:323–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dalamaga M., Karampela I., Mantzoros C.S. Commentary: phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors as potential adjunct treatment targeting the cytokine storm in COVID-19. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2020;109:154282. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haas R., Smith J., Rocher-Ros V., Nadkarni S., Montero-Melendez T., D'Acquisto F., et al. Lactate regulates metabolic and pro-inflammatory circuits in control of T cell migration and effector functions. PLoS Biol. 2015;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ratter J.M., Rooijackers H.M.M., Hooiveld G.J., Hijmans A.G.M., de Galan B.E., Tack C.J., et al. In vitro and in vivo effects of lactate on metabolism and cytokine production of human primary PBMCs and monocytes. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2564. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhu L., Yang P., Zhao Y., Zhuang Z., Wang Z., Song R., et al. Single-cell sequencing of peripheral mononuclear cells reveals distinct immune response landscapes of COVID-19 and influenza patients. Immunity. 2020;53:685–696 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pontelli M.C., Castro I.A., Martins R.B., Veras F.P., Serra L.L., Nascimento D.C., et al. Infection of human lymphomononuclear cells by SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2020:2020. 07.28.225912. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Y., Zhang J., Ren S., Sun D., Huang H.Y., Wang H., et al. Branched-chain amino acid metabolic reprogramming orchestrates drug resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2019;28:512–525 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hiscott J., Kwon H., Genin P. Hostile takeovers: viral appropriation of the NF-kappaB pathway. JCI (J. Clin. Investig.) 2001;107:143–151. doi: 10.1172/JCI11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kobayashi M., Yamamoto M. Nrf2-Keap1 regulation of cellular defense mechanisms against electrophiles and reactive oxygen species. Adv. Enzym. Regul. 2006;46:113–140. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tao L., Lowe A., Wang G., Dozmorov I., Chang T., Yan N., et al. Metabolic control of viral infection through PPAR-α regulation of STING signaling. bioRxiv. 2019:731208. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nguyen L., McCord K.A., Bui D.T., Bouwman K.M., Kitova E.N., Kumawat D., et al. Sialic acid-dependent binding and viral entry of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2021:2021. doi: 10.1038/s41589-021-00924-1. 03.08.434228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rajasekharan S., Bonotto R.M., Kazungu Y., Alves L.N., Poggianella M., Orellana P.M., et al. Repurposing of Miglustat to inhibit the coronavirus severe acquired respiratory syndrome SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2020:2020. 05.18.101691. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vitner E.B., Achdout H., Avraham R., Politi B., Cherry L., Tamir H., et al. Glucosylceramide synthase inhibitors prevent replication of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza virus. J. Biol. Chem. 2021:100470. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bermejo Martin J.F., Jimenez J.L., Munoz-Fernandez A. Pentoxifylline and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a drug to be considered. Med. Sci. Mon. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2003;9:SR29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abdallah M.S. Efficacy of pentoxifylline as add on therapy in COVID19 patients. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04433988. 2021 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04433988 [Google Scholar]

- 101.Matsuda K. Efficacy, safety, tolerability, and biomarkers of MN-166 (Ibudilast) in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and at risk for ARDS. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04429555. 2021 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04429555 [Google Scholar]

- 102.Adnet F. Efficacy of addition of naproxen in the treatment of critically ill patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04325633. 2020 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04325633 [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rahaoui M., Tandjaoui-Lambiotte Y. Efficacy of Captopril in covid-19 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) CoV-2 pneumonia (CAPTOCOVID), ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier NCT04355429. 2021 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04355429 [Google Scholar]

- 104.Funk C.D., Ardakani A. A novel strategy to mitigate the hyperinflammatory response to COVID-19 by targeting leukotrienes. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:1214. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Habibzadeh P., Mofatteh M., Ghavami S., Roozbeh J. The potential effectiveness of acetazolamide in the prevention of acute kidney injury in COVID-19: a hypothesis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020;888:173487. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Luks A.M., Swenson E.R. COVID-19 lung injury and high altitude pulmonary edema: a false equation with dangerous implications. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2020 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202004-327FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Delattre H., Sasidharan K., Soyer O.S. Inhibiting the reproduction of SARS-CoV-2 through perturbations in human lung cell metabolic network. Life science alliance. 2021;4 doi: 10.26508/lsa.202000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1: Overlap of differentially expressed genes in different cell lines and patient samples with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Fig. S2: Protein-protein interaction of viral proteins with the host metabolic proteins. Viral proteins are shown in red color. Metabolic DEGs interacting directly and indirectly with viral proteins are shown in orange and yellow colors, respectively. Non-metabolic genes are shown in the grey color.

Table S1: Differentially expressed genes in response to SARS-CoV-2 in different cell lines and patient samples (xlsx file).

Table S2: Differentially expressed metabolic genes in response to SARS-CoV-2 in different cell lines and patient samples (xlsx file).

Table S3: Drugs that target one or more metabolic DEGs (Z-score < -2.0 and p-value < 0.005) identified using the network proximity analysis (xlsx file).

Table S4: KEGG pathway enrichment of drug targets (q-value cut-off < 0.05) (xlsx file).

Data Availability Statement

All datasets reported in this study are publicly available.