Abstract

The measurement of vascular function in isolated vessels has revealed important insights into the structural, functional, and biomechanical features of the normal and diseased cardiovascular system and has provided a molecular understanding of the cells that constitutes arteries and veins and their interaction. Further, this approach has allowed the discovery of vital pharmacological treatments for cardiovascular diseases. However, the expansion of the vascular physiology field has also brought new concerns over scientific rigor and reproducibility. Therefore, it is appropriate to set guidelines for the best practices of evaluating vascular function in isolated vessels. These guidelines are a comprehensive document detailing the best practices and pitfalls for the assessment of function in large and small arteries and veins. Herein, we bring together experts in the field of vascular physiology with the purpose of developing guidelines for evaluating ex vivo vascular function. By using this document, vascular physiologists will have consistency among methodological approaches, producing more reliable and reproducible results.

Keywords: arteries, contraction, methods, relaxation, veins

INTRODUCTION

Overview of the Consensus Guidelines

Since the publication of the historical book titled, On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals, from William Harvey in 1628 (1), our understanding of the vascular regulation of blood flow and perfusion in the peripheral circulation has grown dramatically. Driven by a search for the truth, Harvey applied the scientific method and deductive logic to show to the world that vessels are functional, connected to tissues, including the lungs, and are essential for the circulation of blood (1). As with many new theories, Harvey's revolutionary idea was received with a great deal of pessimism among his colleagues (2). Personal resentments, professional “territorialism,” religious, mystical, and philosophical arguments were among the several reasons for rejecting the circulation theory. Nonetheless, the controversy was fundamental because it established the use of the scientific method (2).

As modern‐day scientists and clinicians, we are facing a new paradox: an increasing concern about irreproducible scientific results. The lack of guidelines for experimental design, inappropriate or nonrandomization methods, and inconsistencies in methodological approaches between studies contribute to unreliable data. Best practices in common experimental approaches are needed to ensure robust and unbiased methods, analysis, and interpretation of the results. Accordingly, funding agencies, reputable journals, including AJP-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, and scientists have taken substantive steps to improve scientific rigor, reproducibility, and transparency among publications. The Guidelines for Measurement of Vascular Function and Structure in Isolated Arteries and Veins is a comprehensive document detailing best practices and pitfalls for measurement of function and structure in large (conduit) and small (resistance) arteries, and veins. This document brought together experts in the field of vascular physiology with the purpose of developing a consensus guide for ex vivo vascular function. By following these recommendations, scientists will have consistency among methodological approaches, and consequently the results will be reproduced and validated by other vascular physiologists. Therefore, by using these guidelines, researchers will “get rigorous” in their scientific approach (3), collect reliable data, and enhance peer and public perception of science.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS AND COMMON CHARACTERISTICS OF STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE VESSELS

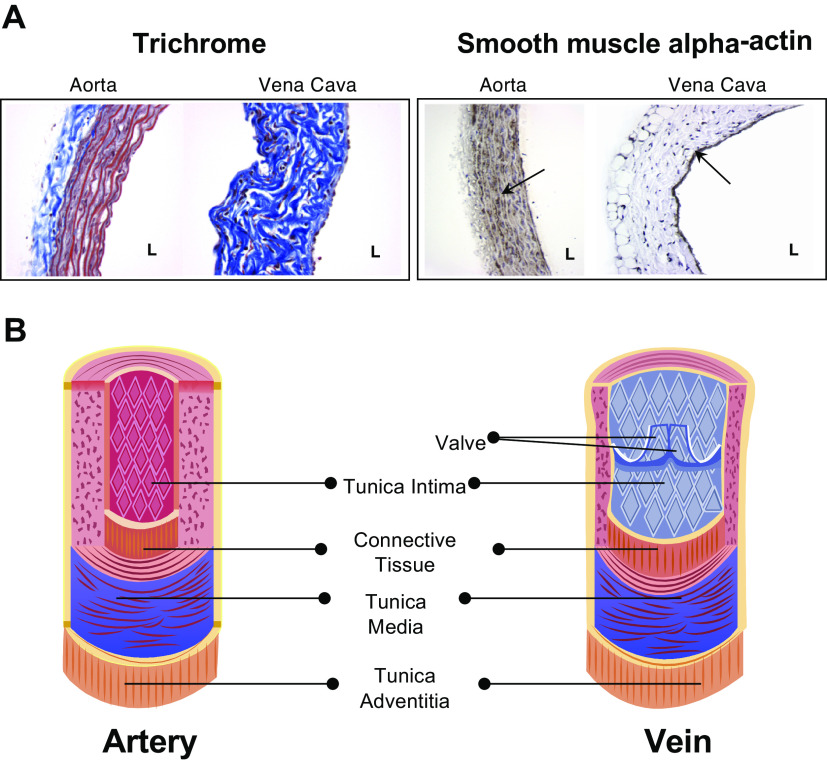

Contraction and Relaxation of Conduit and Resistance Blood Vessels

The vasculature performs multiple roles in the body, including transferring nutrients and mediators to the essential organs, exchanging them across the vascular walls, and blood pressure regulation. Large arteries serve as conduits that carry the oxygenated blood in to the smaller arteries. On the other hand, vessels that, when relaxed, measure <250 μm in lumen diameter, act as the major site of vascular resistance and include a network of resistance arteries (lumen diameter ∼150 to 250 μm) and arterioles (<150 μm). Capillaries are the major sites of exchange across the vascular walls. Capillaries consist of a single layer of endothelial cells and lack the contractile vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC). In contrast with arteries, veins are exposed to lower intraluminal pressures, carry deoxygenated blood back to the heart, and have valves that prevent backflow. Vasoconstriction is a direct result of contraction of VSMC in the vascular wall. Therefore, contractility and relaxation assays have been used in large arteries, resistance arteries and arterioles, venules and veins to obtain information on: 1) the contractile state of VSMC under basal conditions (i.e., myogenic tone); 2) increase in VSMC contractility in response to a treatment; 3) decrease in VSMC contractility in response to a treatment; and 4) endothelial function. The ultimate functional response is a consequence of VSMC signaling and intercellular communication among VSMC. The latter enables the neighboring VSMC to share small metabolites, ions, and second messengers.

The contractile state of small arteries and arterioles defines vascular resistance. Since arterial pressure is a product of cardiac output and total peripheral resistance, resistance arteries and arterioles are key determinants of blood pressure. Conduit arteries have less influence on blood pressure directly and function to convey blood flow in to the resistance vessels controlling blood flow to downstream organs and tissues. Contractility studies have been performed routinely in conduit arteries. However, the contractility of conduit arteries does not directly alter the vascular resistance. A major functional difference between conduit and resistance arteries is that the resistance arteries display pressure-induced or myogenic constriction, which is an inherent property of VSMC (4). Myogenic constriction is a physiological autoregulatory mechanism that maintains vascular resistance under resting conditions and prevents the buildup of excessive hydrostatic pressure in the capillaries. Structurally, conduit arteries such as the aorta have 10–15 layers of VSMC. In contrast, resistance arteries have one or two VSMC layers. The extracellular matrix composition of the vascular wall also differs between resistance and conduit arteries. Elastin is the main component of the extracellular matrix that allows large arteries (elastic reservoirs) to expand and relax with every cardiac cycle (5). Resistance arteries have more collagen than conduit arteries, and arteries collectively have more collagen and elastin than veins (6).

Endothelial cells line the lumen of all blood vessels, and they release mediators that relax or contract VSMC, including nitric oxide (NO), K+ (7), prostaglandins, and other hyperpolarizing factors. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation relaxes VSMC and lowers vascular resistance whereas endothelium-dependent vasoconstriction increases these parameters. The endothelial cell layer is separated from the surrounding VSMC layer by the internal elastic lamina. In resistance arteries, endothelial cells send projections to the VSMC layer through the internal elastic lamina, called myoendothelial projections (8). Myoendothelial projections electrically connect the endothelial cells and VSMC layers via myoendothelial gap junctions (MEGJs) that facilitate the communication between the two cell layers (9). Endothelial cell hyperpolarization is the predominant mechanism for endothelium-dependent vasodilation of resistance arteries (10). Endothelial cell hyperpolarization is transmitted to VSMC via MEGJs, thereby relaxing VSMC. Myoendothelial projections/junctions are either absent or found at a very low number in conduit arteries. Endothelium-dependent relaxation of conduit arteries occurs predominantly through NO release from endothelial cells and its diffusion to VSMC.

Studying vascular contractility: pressure versus wire myography.

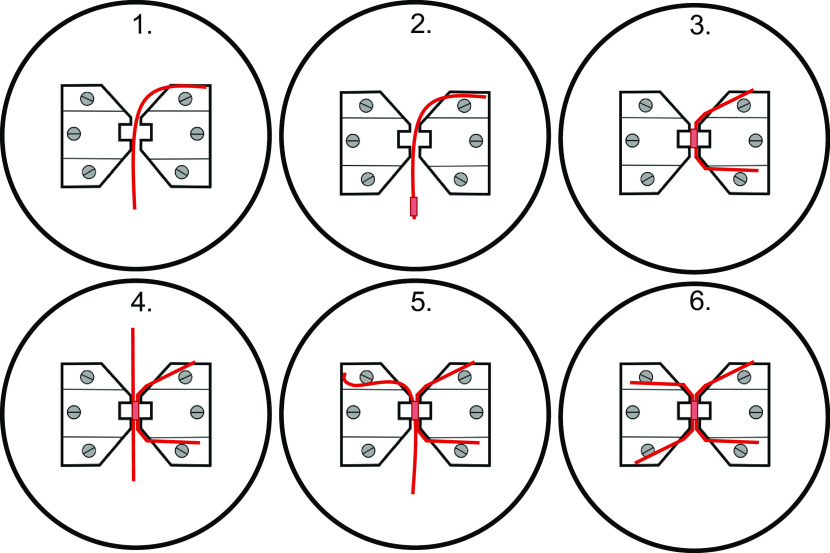

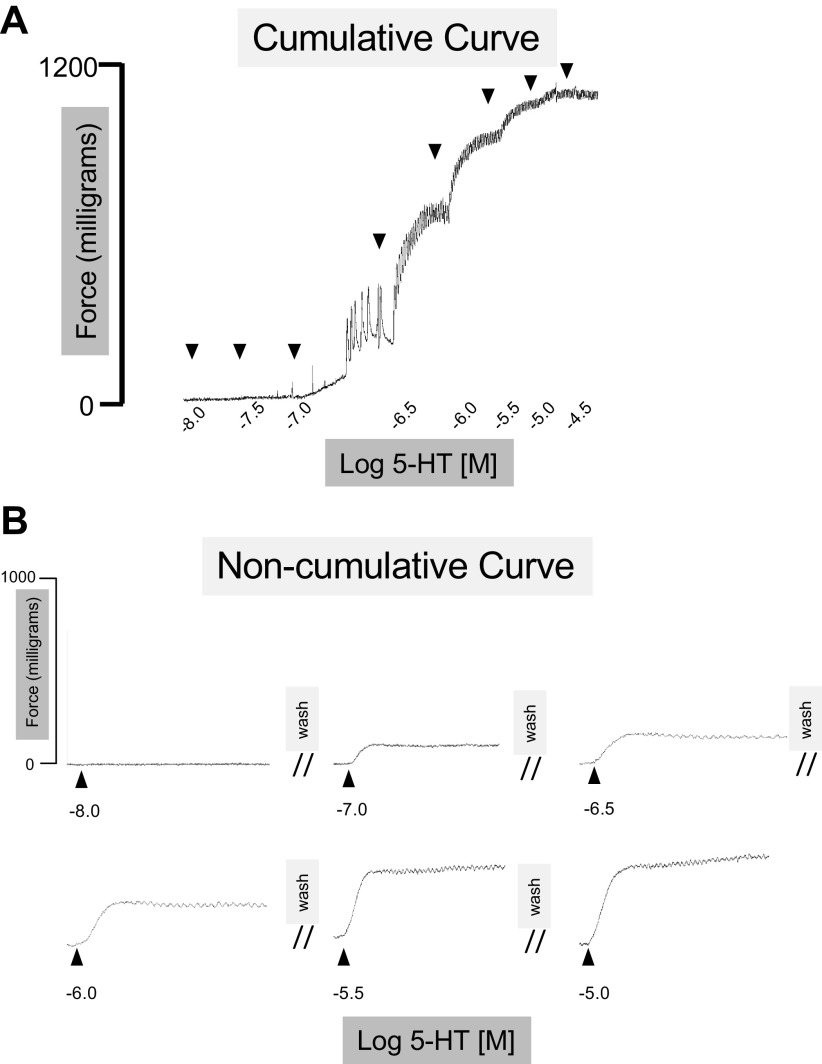

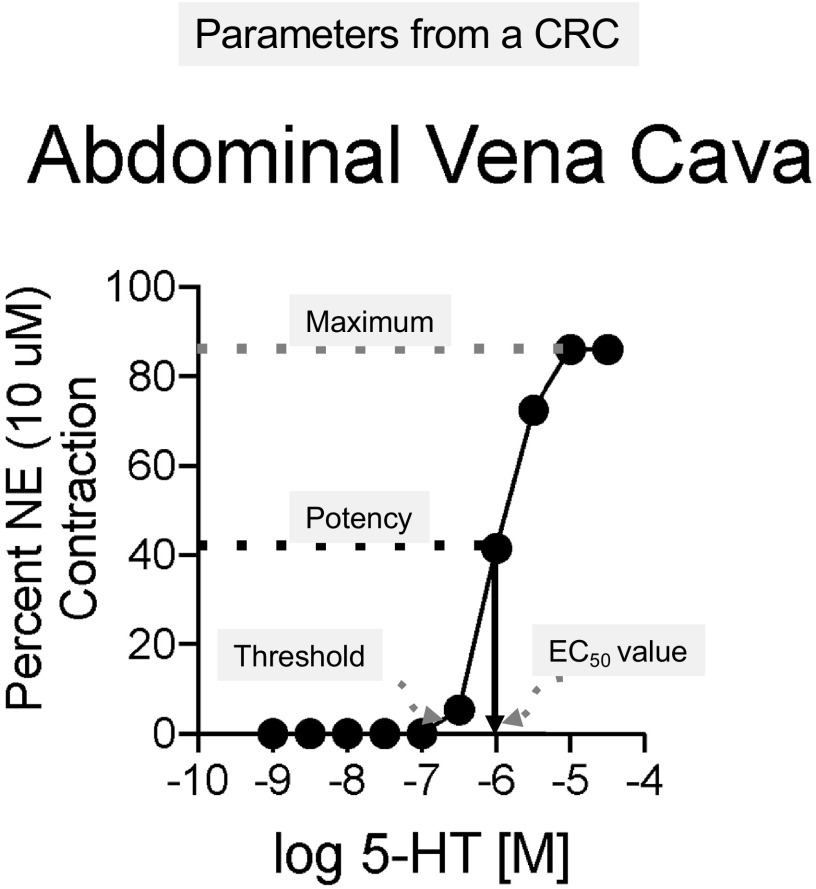

VSMC are effectors and integrators of multiple inputs (pressure, nerves, endothelial cells, vasoactive substances in blood, autacoids). A myograph is any type of device used to measure the force produced by a muscle during contraction due to the different inputs described above. The force generated by the VSMC in the walls of blood vessels is typically studied using pressure, wire, or pin myography (Fig. 1). Pressure myography and wire myography are the two most common ex vivo methods for studying vascular contractility. There is a consensus that pressure myography more closely mimics physiological conditions than wire myography, since vessels exits under pressure in vivo, not stretched between wires. Pressure myography involves cannulation of the blood vessel at one or both ends. The intraluminal pressure is set at a physiologically relevant value through the inflow cannula. It should be noted that distinct vascular beds are exposed to different intraluminal pressures in the body (e.g., 40–60 mmHg in cerebral arteries, 60–80 mmHg in mesenteric resistance arteries, 10–15 mmHg in pulmonary arteries and veins). The ability to manipulate intraluminal pressure enables the studies of the myogenic response with pressure myography. Additionally, pressure myography allows manipulation of intraluminal flow/shear stress, which is a crucial regulator of vascular contractility. Flow/shear stress can be increased by varying the pressure difference between inflow and outflow cannula to yield the appropriate shear (3–20 dyn/cm2) without changing the intraluminal pressure. Alternatively, shear stress can be elevated by increasing the buffer viscosity with dextran (11, 12). For further information about flow, please see section pharmacological and physiological assessment (Flow-Mediated Dilation) below.

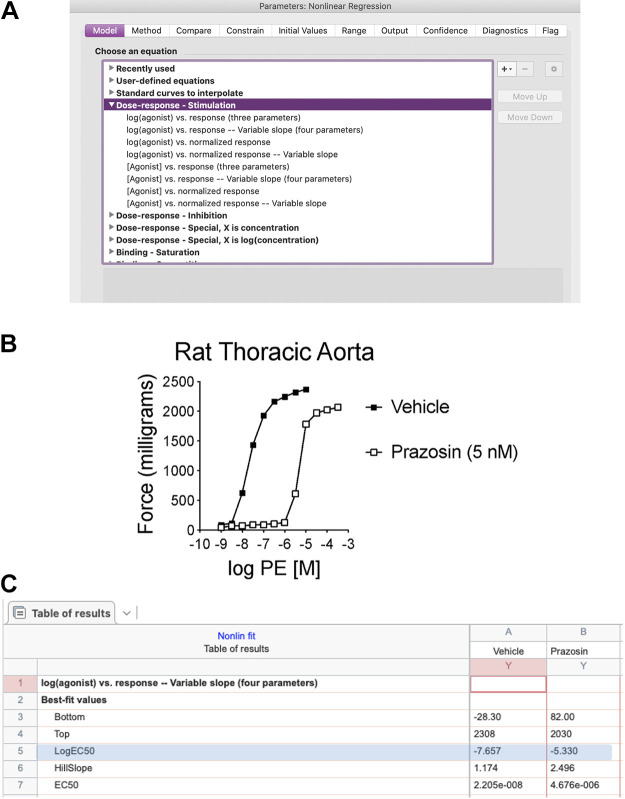

Figure 1.

In a pressure myograph system, blood vessel segments are cannulated with glass pipettes (A) to regulate the intraluminal pressure. In isometric force myograph systems, wires (B) or pins (C) are passed through the lumen of a blood vessel and is stretched to level that approximates physiological conditions.

Wire myography involves mounting a blood vessel on fine, steel wires and recording the tension generated by the vascular wall. Because wire myography does not involve pressurizing a blood vessel, flow/shear stress effects cannot be assessed using a wire-myography setup. Although, myogenic response can be assessed using wire myograph, pressure myograph is more reliable and sensitive to evaluate this parameter. In most cases, wire myography experiments require pharmacological constriction of mounted arteries with a physiological or synthetic vasoconstrictor to generate increased tension. The main strength of the method is that we can discern the contribution of different mechanisms to vascular reactivity by studying segments of the same artery and same animal. This is a strong experimental design that can reduce variability. Additionally, wire myography is a good alternative to pressure myography in instances where the blood vessel’s length is insufficient for pressure myography.

Studies suggest that the conclusions based on pressure myography data could be different from those from wire myography data. For example, the concentration-response curves for phenylephrine-induced constriction of mesenteric resistance arteries show higher sensitivity and lower EC50 values in pressure myography than wire myography (13, 14). The use of a pharmacological constrictor versus pressure for generating baseline tension could itself be a source of variability. Pharmacological constrictors may trigger VSMC signaling pathways that are different from intraluminal pressure, thereby altering the functional outcome. In this regard, pharmacological constrictors (e.g., phenylephrine) have been associated with a negative feedback activation of dilatory endothelial pathways that attempt to limit the constriction (15, 16). Moreover, endothelial pathways elicited in pressure myography experiments could differ from those elicited in wire myography experiments (14). In resistance arteries with myogenic response, endothelial cell-derived hyperpolarization plays a more prominent role than NO in vasodilation. On the contrary, in wire myography experiments in the presence of a pharmacological constrictor, NO appears to be the predominant mechanism for endothelium-dependent relaxation. Therefore, the technique used (pressure vs. wire) and the method used for generating baseline constriction (pressure vs. pharmacological constrictor) warrant particular attention when interpreting and comparing data from myography experiments.

Both pressure and wire myography have been used to determine the effect of endothelial and VSMC signaling mechanisms on vascular diameter. The effect of endothelium on VSMC contractility is studied either as endothelium-dependent vasodilation or a decrease in vascular contractility. The endothelium-dependent nature of dilation/relaxation can be confirmed by its absence when the endothelium is denuded. Endothelial denudation can be accomplished by physically disrupting the endothelial cell layer, as described in section mounting and normalization. Acetylcholine and bradykinin are the classical agonists used for eliciting endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Conclusions on VSMC contractility can be drawn by comparing the contractions in response to increased or decreased luminal pressure (pressure myography only), or a vasoconstrictor (phenylephrine, serotonin, thromboxane A2 receptor activation). High concentrations of potassium chloride (KCl, ≥60 mM) have also been used in myography studies either as a pharmacological constrictor and to determine maximal contractility. High concentrations of KCl depolarize VSMC membrane, resulting in the activation of voltage-gated calcium channels and vasoconstriction. The presence of KCl, however, can influence the myography results. High concentrations of extracellular K+ (≥ 60 mM) can prevent endothelial hyperpolarization and a vasodilatory response. Moreover, KCl-induced membrane depolarization can alter dilator or constrictor responses in VSMC. Finally, intraluminal pressure is another important source of variability in pressure myography experiments. Both VSMC and EC responses are altered by changes in intraluminal pressure (17, 18). In this case, the best practice is to use a physiologically relevant pressure for the blood vessel type and size.

Overall, pressure and wire vascular myography techniques have distinct advantages and disadvantages. Pressure myography more closely mimics physiological conditions and allows the relationship between intraluminal pressure and VSMC contractility to be evaluated directly. Wire myography allows better access to the vascular endothelium, and isometric preparation is useful for simultaneous recording of contractile force and VSMC membrane potential with intracellular electrodes because electrodes are not displaced by movement of the tissue.

Important Considerations

Variability in myography results is a significant concern in vascular biology. In this regard, the choice of myography technique appears to have a telling effect on the results and conclusions. As discussed above, the discrepancy in vascular contractility studies could be attributed to one or more of the following variables:

Myography technique (pressure vs. wire)

Vascular bed

Size of the artery (resistance vs. conduit)

Myogenic constriction vs. pharmacological constrictor

Presence or absence of endothelium

Intraluminal pressure used in pressure myography experiments.

Therefore, it is imperative that detailed descriptions of the above parameters accompany the presentation of vascular contractility data. Moreover, conclusions derived from vascular relaxation and contractility studies should always consider the above parameters.

Methodological Consideration before Starting

a. Myographs.

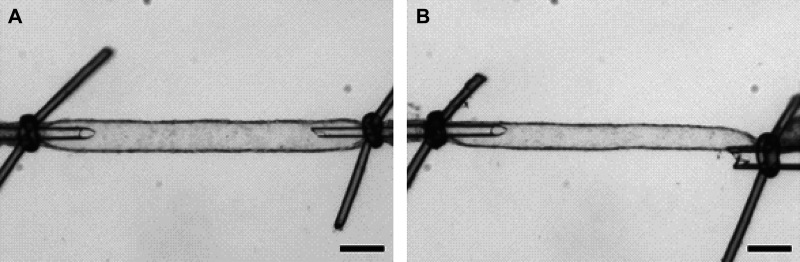

In a pressure myography system, segments of isolated blood vessels are cannulated at one end. More commonly, both ends are mounted and tied onto glass pipettes, and the intraluminal pressure is regulated by controlling the pressure at one of the cannulas (Fig. 2A). The downstream cannula may be closed off to create a “blind sack” preparation or left open for flow-through applications (Fig. 2B). It is important to cannulate branches of a sufficient length (≥ 2–3 mm) to have an undamaged segment in between the two cannulas. However, in some cases, 2–3 mm in length without branching is not possible (e.g., coronaries). Therefore, in this situation, it is important to cannulate vessels of sufficient length (at least 2–3× the luminal diameter) to have an undamaged segment in between the two cannulas. The preparation is typically superfused with physiological saline solution warmed to 37°C and aerated with an appropriate gas mixture to maintain proper oxygen levels and pH. Chemically buffered solutions (i.e., HEPES buffered saline) are occasionally used in particular circumstances (please see Composition of the physiological salt solutions section). Drugs and other substances are usually applied to the preparation in the superfusing bath. Administration of substances to the vascular lumen through one of the cannulas is also feasible but less common, as flow rates through small-diameter vessels are slow. Blood vessel diameter is commonly recorded using video microscopy and specialized software that tracks the relative positions of the inner and/or outer walls. These data can be expressed as inner (luminal) or outer diameter, and wall thickness can be calculated. The contractility of VSMC is often expressed as the active diameter normalized to the passive diameter recorded in a calcium (Ca2+)-free solution to prevent contractile responses. Preparations can be viable for hours (∼6–9 h) after they are cannulated, depending on the vessel type used. Appropriate time control experiments should be performed to ascertain this information.

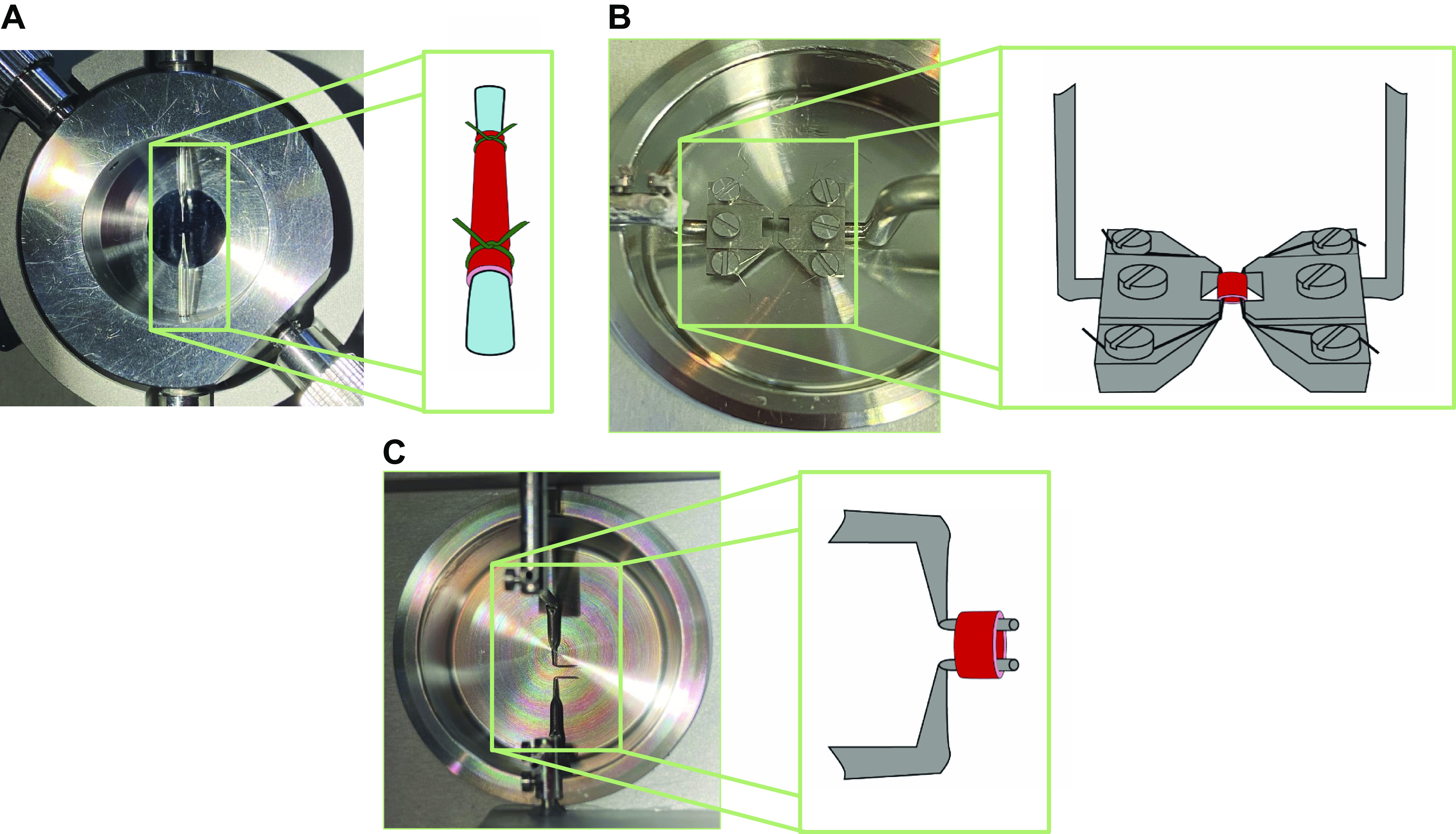

Figure 2.

Blood vessel segments can be cannulated at both ends for flow-through applications (A), or tied off and secured to the cannula at one end to create a “blind sack” (B).

During wire myography, blood vessel segments are threaded onto a pair of pins, for large arteries, or wires for muscular and resistance-sized arteries (Fig. 1, B and C). The tissue is prestretched or normalized to a level that approximates physiological conditions. The segments are bathed in warmed and aerated physiological saline to maintain appropriate pH and oxygenation levels. Drugs can be applied directly to the organ bath chamber and removed by rapid washes. The mounting wires are connected to force transducers, and isometric force generated by contracting VSMC is directly recorded. Contractility data are most frequently normalized to the force generated when the preparation is exposed to a high concentration (i.e., ≥60 mM) of KCl to directly depolarize the plasma membrane of VSMC. Preparations can be viable for hours (∼6–9 h) after they are mounted, but appropriate time control experiments should be performed to ascertain this information.

b. Dissecting microscopes.

Whether using a wire or a pressure myograph, the successful mounting or cannulation of isolated vessels often requires the use of a dissecting, or stereo microscope, particularly for smaller arteries and arterioles. Most major microscope manufacturers make dissecting microscopes, and the types and features of them are almost limitless. The successful mounting or cannulation of blood vessels does not require expensive add-on features, although they can be very useful, depending on the application. Although some larger blood vessels (e.g., conduit arteries) can be cannulated and mounted without the use of a dissecting microscope, we recommend using dissecting microscopes whenever possible so that the investigator is able to clearly visualize the vessel and prevent damage. The successful mounting/cannulation of resistance arteries and arterioles of the microcirculation (e.g., <250 µm diameter) requires the use of a dissecting microscope with at least ×5 magnification.

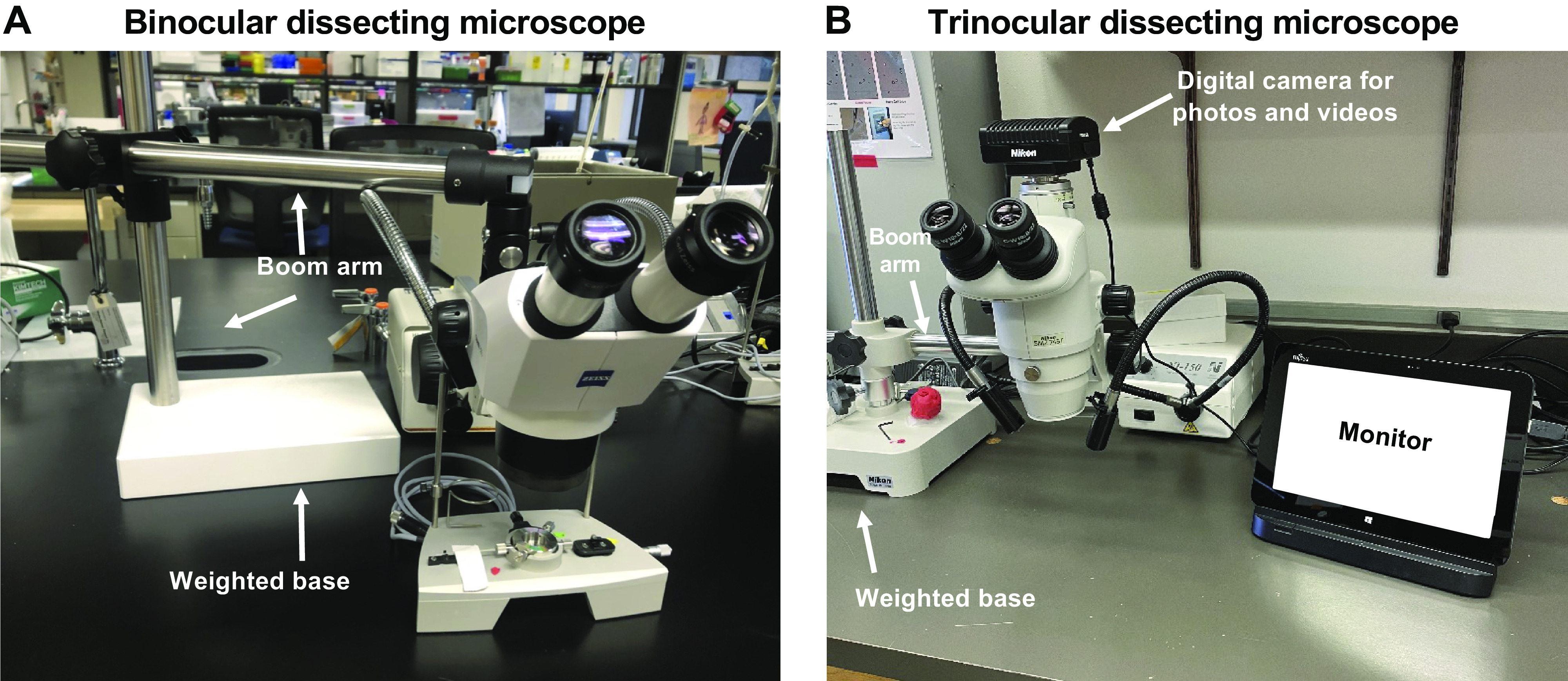

For the purposes of isolating blood vessels, we recommend using binocular or trinocular microscopes. Both types of microscope has two eyepieces for viewing the vessels and provide depth perception. A trinocular microscope also has a third eye tube for connecting a camera, which makes it useful for teaching purposes. The trinocular setup on dissecting microscopes is optimal when teaching how to successfully isolate different blood vessels. Some binocular or trinocular microscopes are situated over a weighted base on which tissue dissections can be performed. The use of these types of microscopes are probably okay for larger vessels that require microscopy for cannulation (e.g., aorta or similar sized vessels >500 µm); however, we recommend using dissecting microscopes that are connected to a weighted base via a boom arm (Fig. 3). This allows one to stabilize their hands on the laboratory bench for easier isolation and mounting/cannulation.

Figure 3.

Binocular (A) and a trinocular (B) dissecting microscope connected to a weighted base via a boom arm.

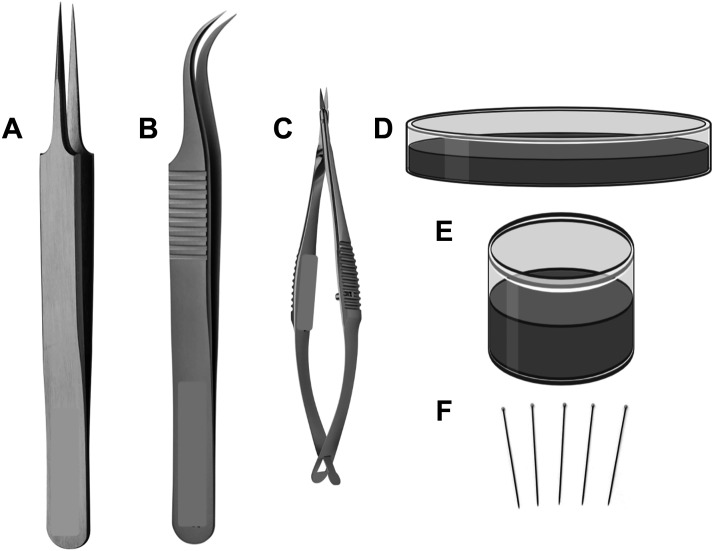

c. Tools.

Sharp and well-maintained tools are essential for careful dissection of macro- and microvessels from surrounding adipose and connective tissues before ex vivo experiments. Vannas spring scissors, glass-dissecting dishes with a smooth layer of silicone elastomer (e.g., Sylgard 184) on the bottom, and insect pins (or ∼28 gauge needles) are necessary for vessel dissection and cleaning, whereas forceps with fine tips are required for vessel dissection but also for vessel mounting and cannulation (Fig. 4). The length of the cutting edge of the Vannas scissors and the width of the tips of the forceps vary with vessel type and size. Typically, scissors with a cutting edge of 2.5 mm length are appropriate for dissection of small vessels (e.g., rodent uterine arteries, mesenteric arteries and veins, coronary arteries), whereas scissors with a longer cutting edge (∼4–5 mm) may be used for larger arteries (e.g., aorta). Vannas scissors may be made from titanium or stainless steel. Forceps with fine tips are made for high precision laboratory work under the microscope and are extremely delicate and fragile. Thus, care is required in handling these instruments. Popular styles of dissection forceps are the Dumont No. 5 (straight forceps, tip dimensions: 0.05 × 0.01 mm) and Dumont No. 7 (curved forceps, tip dimensions: 0.07 × 0.03 mm). Forceps with fine tips may be made by several materials (i.e., titanium, stainless steel, carbon). The material used determines the durability, corrosion resistance, resistance to mineral and organic acids, and ability to autoclave these instruments. Glass-dissecting dishes with silicone elastomer can be purchased by various vendors or prepared by the investigator. We recommend using black silicone elastomer to improve contrast and visualization. Availability of dissecting dishes of various sizes and depths is important to accommodate different vessels and dissection procedures. For example, a shallow dish can be used for the dissection of mesenteric arteries, whereas a deep dissection dish can be used for isolation of cerebral vessels. Insect pins are used to secure the tissue in the dissecting dish.

Figure 4.

Essential tools for dissecting macro- and microvessels for ex vivo experiments. Straight forceps with fine tips (A), curved forceps with fine tips (B), Vannas spring scissors with straight cutting edge (C) (curved scissors are also available, not shown), shallow and deep glass dissecting dishes with black silicone elastometer on the bottom (D, E), and insect pins (F). Created with Biorender.com.

d. Composition of the physiological salt solutions.

The ideal buffer for all vascular function is one that maintains pH within acceptable levels (resting intracellular pH in VSMC ranges from 7.1–7.3 regardless of vascular bed) (19) and mimics the in vivo concentration of circulating ions. Regardless of which buffer recipe is used, whether it be one described here, or another one of the many adaptations found in the literature, standardization of the buffer to your laboratory’s preparation and consistency across experiments are the most important principles to follow for scientific rigor and reproducibility of data.

Isometric force.

Presented in Table 1 are the concentration of compounds that make up classical Krebs-Henseleit buffer and an adapted recipe that we recommend for isometric vascular preparations. The recipe has been modified from the classical Krebs-Henseleit buffer in the following ways:

Table 1.

Concentrations of compounds that make up the classical Krebs-Henseleit buffer and the adapted physiological salt solution that we recommend for isometric force measurement on wire and pin myographs

| Compound (Mol wt), g/Mol | Classical Krebs-Henseleit Buffer, mM | Vascular Adaptation for Isometric Force Studies, mM |

|---|---|---|

| NaCl (58.44) | 118.0 | 130.0 |

| KCl (74.55) | 4.7 | 4.7 |

| KH2PO4 (136.09) | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| MgSO4 (246.28) | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| NaHCO3 (84.00) | 24.9 | 14.9 |

| Glucose (180.16) | 10.0 | 5.6 |

| EDTA (292.15) | - | 0.03 |

| CaCl2 (147.02) | 2.5 | 1.6 |

Less bicarbonate, which has been shown not to affect contractile responses (20).

Less glucose, because glucose concentrations approaching 10 mM are considered prediabetic.

Includes EDTA, which is added to the buffer before the addition of CaCl2 to chelate any Ca2+ that may have inadvertently ended up in the buffer.

Less CaCl2 because 1.6 mM is closer to the concentration of circulating “free” ionized calcium which could contribute to vascular contraction. Although 2.5 mM is the total concentration of circulating Ca2+, as much as ∼40% of this Ca2+ is bound to proteins (e.g., albumin) or complexed with anions (e.g., bicarbonate or phosphate) and is unavailable to contribute to contraction.

Several commonly used artificial buffers have been suggested to attenuate VSMC contractile responses (21, 22). Therefore, we recommend optimizing your preparation if you wish to incorporate an artificial buffer such as Tris, HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid], MOPS [3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid], BICINE [N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)glycine], or PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)] in isometric preparations (wire or pin myograph).

Isobaric conditions (myogenic tone).

Special considerations in preparing buffers for studies of myogenic tone are to maintain pH and osmolality near physiological levels. The small vessels studied are more sensitive to osmotic and pH shock than larger, more robust arteries. Some laboratories add glycol or albumin to the solutions to maintain buffer viscosity, but this is not an absolute requirement. The physiological saline solutions we recommend is 5% CO2–21% O2 bubbled bicarbonate buffer (see Table 2A for recipe) for superfused preparations and a 21% O2 bubbled HEPES buffer (Table 2B) for nonsuperfused preparations. In isobaric preparations, we also recommend using a buffer with a greater calcium chloride concentration (≥ 2–2.5 mM), as this enhances myogenic tone.

Table 2.

Concentrations of compounds and that make up the bicarbonate buffer, the HEPES buffer, and the calcium (Ca2+)-free bicarbonate buffer

| Compound (Mol wt), g/Mol | Bicarbonate Buffer, mM | HEPES Buffer, mM | Ca2+-Free Bicarbonate Buffer, mM |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl (58.44) | 130.0 | 134.0 | 130.0 |

| KCl (74.55) | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.4 |

| NaH2PO4 (119.98) | 0.5 | - | 0.5 |

| MgSO4 (246.28) | 0.8 | - | 0.8 |

| MgCl2 (95.21) | - | 1.0 | - |

| NaHCO3 (84.00) | 19.0 | - | 19.0 |

| Glucose (180.16) | 5.5 | 10.0 | 5.5 |

| EDTA (292.15) | - | 0.03 | 4.8 |

| CaCl2 (147.02) | 1.8 | 2.0 | - |

| HEPES (238.30) | - | 10.0 | - |

To evaluate myogenic tone, it is also important to isolate and cannulate arteries quickly, avoid stretching or damaging the arteries and to prevent “cold shock” by not using ice-cold buffers. If performed quickly, the vessels can be isolated, cleaned, and mounted at room temperature. However, for the coronary circulation, the heart will continue to beat unless placed in ice-cold solution. Thus, in the heart, room temperature dissection is not recommended, even if studying the myogenic response. Please see Coronary arteries and microcirculation described below for more information. For isolation and cannulation, we use the HEPES buffer to also avoid the high pH common in bicarbonate buffer and is not constantly bubbled with a CO2 solution.

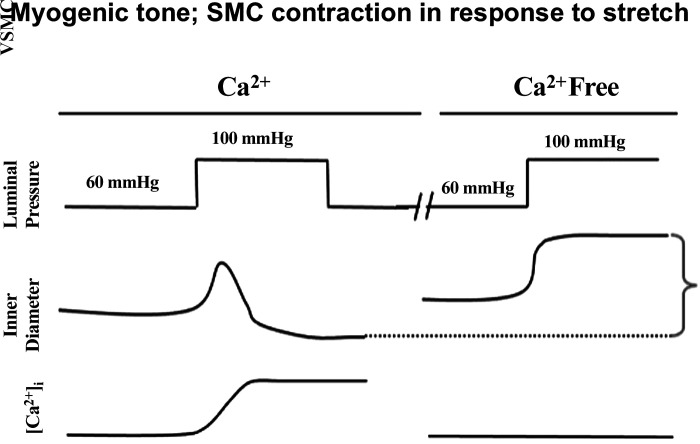

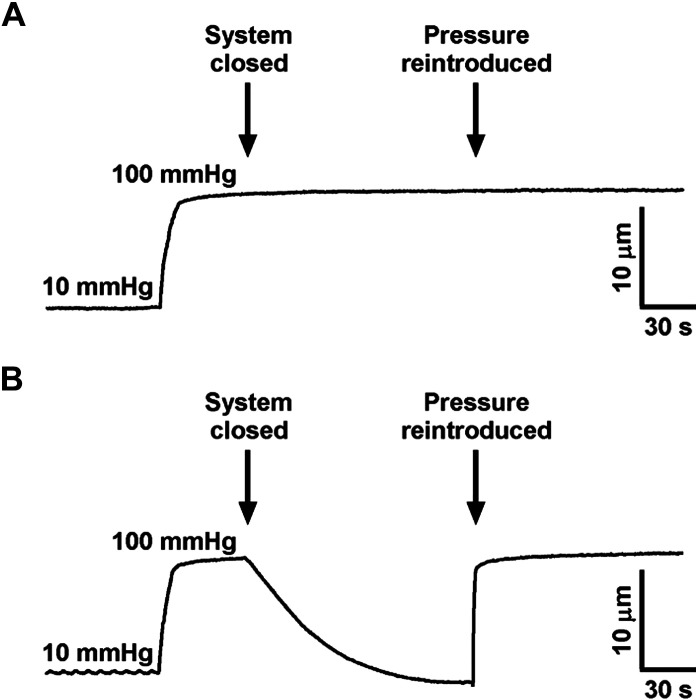

For the recording of myogenic tone and/or passive vascular measurements, it is also necessary to prepare a Ca2+-free buffer (Table 2C) to assess the passive properties of the vessel. The protocol we use to record myogenic tone is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Diagram showing method to evaluate myogenic tone in an isolated, pressurized artery. VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

VASCULAR FUNCTION IN ISOLATED VESSELS

Dissection and Isolation of the Vessels

Important Considerations:

Anesthesia

Kill the animal humanely using a method recommended by the Panel on Euthanasia from the American Veterinary Medical Association (e.g., overdose of general anesthesia isoflurane via a nose cone and thoracotomy and exsanguination via cardiac puncture).Differentiating arterioles from veins

Veins have thinner wall, more branches, and are more easily compressed and distorted by minor pressure while dissecting.Vessel dissection and cleaning

Isolating arteries and veins that remain viable throughout an experiment is a skill with a steep (weeks to months) learning curve. Even a modicum of stretching during dissection can damage a vessel sufficiently to alter normal vasomotor responses.

Dissecting time varies between vascular bed, and extricating vessels from some tissues (e.g., heart or skeletal muscle) is much more difficult than from other tissues (e.g., subcutaneous adipose). However, a general rule of thumb is that the longer you clean, the greater chance of unintended vessel damage. Many of the vascular beds described in this article can be efficiently dissected in ∼15–25 min.

“Over trimming” the adventitia and excessively “cleaning” of the perivascular adipose tissue often elicits unintended traumatic injury to the underlying media and intima.Species considerations

When working with human tissue, it is recommended to leave intact a modest layer of adventitia surrounding the vessel (enough so that the luminal edges are still easily detectable).Vessel viability and integrity testingExperimental demonstration of intact responses to known vasomotor agents is important.

With a delicate and efficient dissection, vessels can easily remain viable for the entirety of an experiment [i.e., multiple hours (∼6–9 h)].

a. Aorta.

The aorta is the largest artery in the body. The aortic arch rises from the heart's left ventricle and oxygen-rich blood flows down the thoracic cavity, through the diaphragm, and into the abdomen. Many smaller arteries branch from it, including the renal arteries and organs of the digestive system. The abdominal aorta subsequently divides into the iliac arteries.

The aorta not only serves as a conduit during systole but also acts as a reservoir for blood. Its elastic properties allow the aorta to store half of the ejected stroke volume. Aortic recoil during diastole pushes the remaining stored volume forward into the peripheral circulation. This phenomenon is known as the Windkessel function (23). This elasticity allows the aorta to absorb the force of the blood as it is pumped from the heart and subsequently propelling it to downstream organs. In some diseases however (e.g., hypertension), this elasticity is lost due in large part to aortic stiffening. Aortic stiffening is defined as decreased compliance because of elastic fiber degradation, increased fibrosis, and in the case of hypertension, increased distending pressures. Aortic stiffening can have deleterious hemodynamic consequences for delicate downstream organs and increases the risk for other terminal cardiovascular diseases (e.g., myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke).

Although the aorta is the largest, and arguably the most durable artery in the body, care needs to be applied during its isolation and cleaning to avoid mechanical damage. Generally, the thoracic aorta, as opposed to the abdominal aorta, is used in isolated vascular function studies as the thoracic aorta is primarily responsible for the propelling blood flow downstream. Increased contractility and endothelial dysfunction of the thoracic aorta are indicative of enhanced stiffness (24).

Practical tips: aorta.

Promptly following thoracotomy and exsanguination, move the dead animal into a position so that the chest cavity can be opened, allowing as much room as possible.

Next, remove the lungs and pulmonary artery by gently pulling the lungs up and opening the fibrous sheath between the pulmonary artery (which will be pulled up) and the thoracic aorta which will be running directly adjacent to the spine. The lungs can be carefully removed by cutting the pulmonary artery perpendicularly at both ends.

At this point, if exsanguination via cardiac puncture was performed, there is probably a pool of blood obscuring the view of the thoracic aorta. This blood can be gently wiped and absorbed using gauze (be careful not to touch the aorta).

Next is the extraction of the aorta itself, which can be performed with or without a dissecting microscope. First, secure the trachea or aortic arch with forceps and gently lift the aorta up. Begin cutting distally toward the abdomen, in parallel to the aorta and spine. If the surgical scissors are gently pressed against the spine of the animal, the cutting will always avoid the aortic wall and will be only cutting the surrounding perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT). The PVAT can be fully removed at a later step.

Continue cutting from the aortic arch down toward the abdomen, always maintaining slack on the aorta. A common beginner error is to pull the aorta too forcefully during this procedure and damaging it from excessive stretch. Eventually, the view of the thoracic aorta will become obscured by the liver and a perpendicular cut can be performed to remove it entirely.

Secure the aorta a Petri dish filled with ice cold physiological salt solution by pinning the PVAT at both ends. Ice-cold physiological salt solution is acceptable for the aorta, as it is less-sensitive to “cold shock” to evaluate myogenic tone in resistance arteries and arterioles. If the research question does not involve understanding intact aortic PVAT, we recommended dissecting it off at this point as a standard operating procedure due the influences of PVAT on vascular contractility (25)

Regardless of whether the PVAT is maintained or removed, using a dissecting microscope, cut the thoracic aorta into 2-mm segments for functional assessment if studying rats and 3-mm segments if studying mice.

b. Mesenteric resistance arteries.

As described in the buffer section, small arteries should be treated with care to prevent damage (<250 µm). The entire mesentery should be removed from the animal within minutes of euthanasia and transferred to a dissection chamber containing pH 7 cold physiological saline solution (e.g., Krebs, Table 1; as described above, cold solution should not be used for evaluating myogenic tone) or HEPES buffered physiological saline solution (Table 2B). The buffer should be changed as necessary to remove fecal material and adipose tissue that is released into the solution.

The mesentery can be gently pinned out to allow easier isolation of the individual branches. Isolation of resistance mesenteric arteries requires a dissecting scope with good optics (preferably ×10 magnification) and sharp, high quality microdissection tools (please see Fig. 4), as discussed earlier. For rat mesenteric resistance arteries, usually a 6th to 7th order artery (lumen diameter <150 µm) is required to achieve the desired size to evaluate myogenic tone using pressure myograph. For wire myograph studies, a third-fifth order artery (lumen diameter 150–250 µm) can be used to evaluate resistance artery function. For mouse mesenteric arteries, a fifth order artery (lumen diameter <150 µm) is usually the appropriate size to evaluate myogenic tone, and third-fourth order (lumen diameter 150–250 µm) to evaluate vascular function. Figure 6 illustrates the method we recommend to identify and isolate mesenteric resistance arteries.

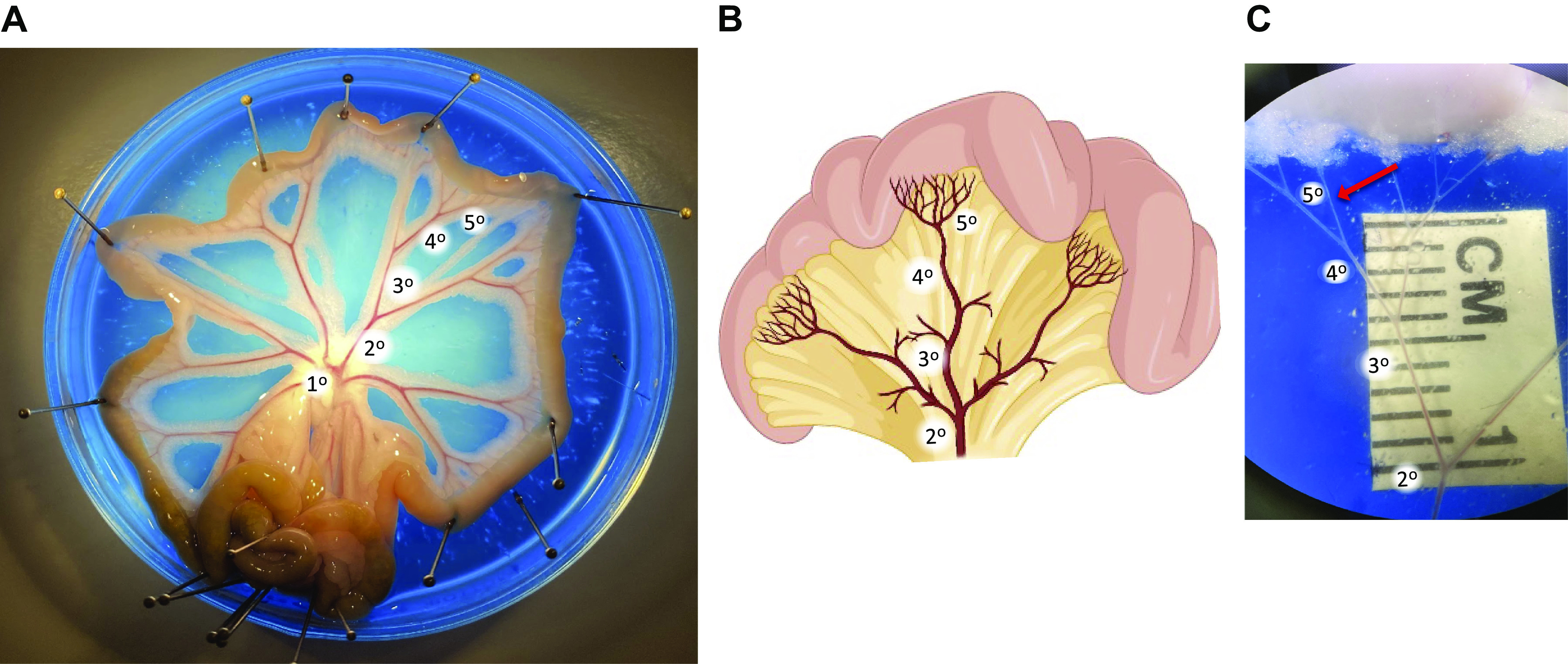

Figure 6.

Isolation of small mesenteric arteries for vascular studies. Isolated rat mesenteric bed that is pinned out in a petri dish containing colored silicon elastometer and filled with physiological salt solution (A and B). C is magnified to illustrate the 5th order artery selected for cannulation after removal of the adipose, veins, lymph vessels, and connective tissue. Figure provided by Perenkita Mendiola at the Dept. of Cell Biology and Physiology, Univ. of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

Practical tips: mesenteric resistance arteries.

The first step is to identify a vascular tree with appropriate small vessels entering the gut wall. Care should be taken to consistently isolate either jejunal arcades (proximal to the stomach) or ileal arcades (proximal to the colon), as there are subtle differences in vascular function between the different sections. Both form anastomotic arcades within the mesentery from which the small straight arteries (arteriae recta, AR) branch to enter the intestinal wall. The jejunal arteries have a slightly greater diameter than the ileal arteries of the same branches, whereas the ileal arteries have a greater number of arcades.

A 2010 study suggested that, in human mesenteric arteries (26), the small AR are more muscular than their feed arteries but that the muscularity does not differ significantly between the jejunal and ileal sections.

Because the AR are longer in the jejunal region, we recommend using this region to collect arteries for isolated artery studies using either isometric or isobaric preparations. It is also important to note that there have been conflicting reports of the degree of myogenic tone present in this bed (27–29). The endothelium provides a strong suppression of myogenic tone, and significant myogenic tone occurs after removal of the endothelium or after inhibition of endothelial dilator pathways (NO synthase, cystathionine gamma lyase, cyclooxygenase). The presence or absence of an active endothelium is therefore important to define in the methods of any study of myogenic tone in the mesentery. Please see mounting and normalization.

c. Coronary arteries and microcirculation.

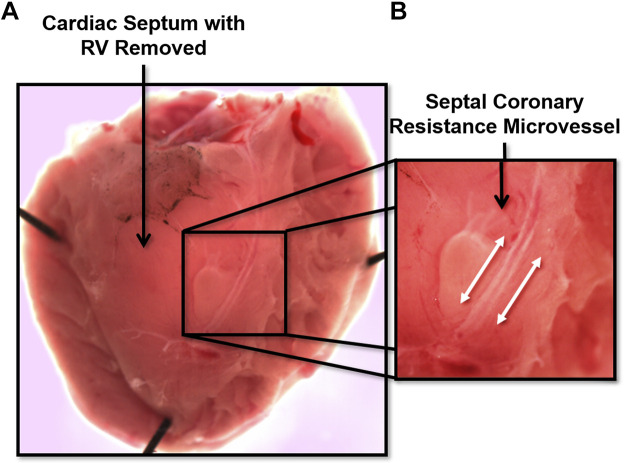

The coronary circulation supplies blood flow to the myocardium. It is unique because is the only vascular bed to flow primarily during diastole, owing primarily to extravascular compression during cardiac systole. Similar to the other vascular beds, the regulation of coronary blood flow is governed by a myriad of factors, including local metabolites, coronary perfusion pressure, myogenic tone, neurohormonal influences, VSMC and endothelial cells, structure, and biomechanics (30, 31). Much of the data gathered to date has been collected on left anterior descending (LAD) coronary arteries, left circumflex coronary artery, right coronary artery, and the arterioles and microcirculation that branches from these upstream arteries. The successful dissection and isolation of these vessels depends on the size, with varying approaches for each, mostly due to the large variation in the amount of connective tissue that must be dissected in order to isolate the vessels. In large species (e.g., pigs and humans), the LAD and other commonly used arteries are considered epicardial conduit arteries with diameters between 2–3 mm. To delicately isolate coronary arteries, we recommend a combination of curved forceps with a ∼0.5-mm tip width and Dumont SS forceps with a 45° angle to bluntly dissect large arteries free from myocardial tissue in large species that have well-developed connective tissue and PVAT (e.g., pig). During the dissection and isolation of large coronary arteries, branches must be cut with small Vannas spring scissors. If the desired experiment is pressure myography, one must leave sufficient length on branches such that they can be tied closed with suture. This is not a requirement if the vessel will be mounted in a wire or pin myograph. In rodents, these vessels are considerably smaller (∼250–400 µm in diameter). Arterioles within the coronary microcirculation are important regulators of coronary blood flow. An example is the mouse septal coronary arteriole (Fig. 7), which can be exposed by cutting off the right ventricle with a pair of Vannas spring scissors (4–5 mm cutting edge) and exposing the interventricular septum. Once exposed, this rodent vessel, and others of similar size (e.g., LAD), can be isolated using a pair of Dumont 55 or 55SF (“superfine”) forceps and removed from the tissue using very fine Vannas spring scissors (2 mm cutting edge) for mounting on a myograph of choice. In larger species such as the pig, coronary arterioles are richest in the endocardial and apical regions of the myocardium. We recommend to cut a manageable slice of myocardium (2 cm × 2 cm × 5–10 mm thick) using a razor blade or scalpel to keep it pinned to a dish, immersed in cold buffer or physiological saline solution, and to more easily identify vessels of interest. This is also true when isolating larger epicardial conduit coronary arteries.

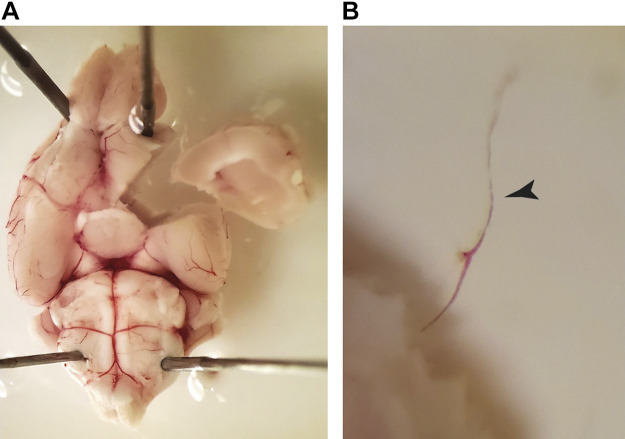

Figure 7.

Image shows a cardiac septum with right ventricle (RV) removed (A), and an amplified image for a septal coronary resistance microvessel (B).

Practical tips: coronary vessels.

Coronary arteries and arterioles are embedded within a dynamic muscle, and as such, it can take significant effort and practice to isolate them from surrounding tissue that could influence the resultant data. Significant practice is critical in the proper assessment of coronary structure, function, and biomechanics, and it is somewhat of an art to balance dissecting with risk for damaging the vessel. These practical tips can help investigators be successful in dissecting and isolating coronary vessels:

Tools: For the dissection and isolation of coronary arterioles (regardless of species), we recommend using Dumont 55 or 55SF forceps that have maintained a sharp tip. Be aware of the location of the tip at all times because it only takes one slip-up to ruin a good pair of forceps! For excision, a good pair of Vannas spring scissors with a 2-mm cutting edge work well.

Dissecting Dish: a low-profile glass dissecting dish of choice filled with an ∼5-mm-thick layer of silicone elastomer (e.g., Sylgard) on the bottom and filled with ice-cold buffer or physiological salt solution sufficient to cover the myocardial tissue from which coronary arteries or arterioles will be isolated. This setup allows one to secure either slices of tissue (in the case of large animal coronary dissection) or rodent hearts for dissection using tissue pins.

Dissection of coronary arteries: It is important for coronary arteries and arterioles to be devoid of surrounding tissue. This is best accomplished, particularly for smaller arterioles, when the vessels are still connected within the tissue. This method allows the investigator to clean the vessels from all angles (top, bottom, sides) without having to hold or secure it in place as would be the case if it was excised.

d. Skeletal muscle arteries.

Supply of oxygenated blood to skeletal muscle is essential to maintain skeletal muscle metabolic activity in a range of functional events from exercise, to contraction of the diaphragm during breathing. Indeed, active hyperemia in skeletal muscle can cause blood flow to dramatically increase from resting levels of ∼1 mL/min, up to ∼75 mL/min (dependent on muscle type). As one might expect then, the arteries in the skeletal muscle must be capable of rapid dilation and constriction many times the resting tone. Thus, skeletal muscle arteries respond to a variety of stimuli, including shear stress, pressure, hormonal, metabolic molecules, oxygen, neuronal, and blood volume.

Skeletal muscle arteries can be directly dissected from an anesthetized animal (i.e., muscles will not need to be separately dissected) or first dissecting out the muscles. This will depend on the muscle of interest as to how the resistance arteries can be visualized for dissection and removal. However, because of the large variety and location of skeletal muscle, the removal of the skeletal muscle artery requires some preplanning to ensure the animal is in the proper position for the skeletal bed desired, as well as what size artery will need to be removed. Begin at the feed artery of the skeletal muscle bed and work down as far as desired. Generally, the smaller arteries near terminal arterioles (lumen diameter <100 µm) are difficult to obtain for ex vivo preparations due to the amount of dissection of skeletal muscle required.

Practical tips: skeletal muscle arteries.

Three variables will almost always determine the efficacy of your dissected skeletal muscle arteries: time of dissection, stretch of the artery, and dampness of preparation.

Once the arteries are determined (Fig. 8), gently remove the adventitia of the muscle around the artery. Finding the artery on muscle can be difficult due to translucent nature of vessels, but the remaining blood in the artery can help orientate the branch order.

Keep muscle damp to every degree possible. This can be done simply by pipetting buffer on the muscle regularly or having a regular drip system on the muscle.

Next cut the desired artery using fine tip scissors and very gently lift with fine tip forceps. Cut the connective tissue along the length of the artery to remove from the muscle and ensure it is of proper length for cannulation or mounting before making the final cut.

With the fine tip forceps, place the artery in buffer, being careful to note the direction of blood (so that directionality can be obtained if desired).

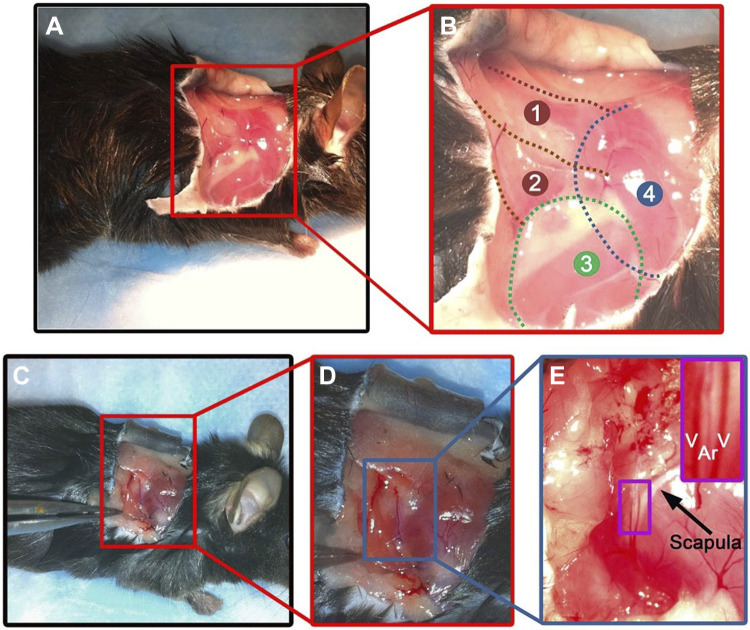

Figure 8.

Image shows a muscle artery predissection. Thoracodorsal artery (TDA; ∼200 µm in lumen diameter) from mouse lays on top of the spinotrapezius muscle. Lateral view of the right shoulder of a mouse (A). Enlargement of the red box shown in A describing the anatomy of the superficial muscles of the right shoulder of a mouse: 1: spinotrapezius muscle; 2: latissimus dorsi muscle; 3: triceps brachii muscle (forelimb); 4: position of the scapula (B). Lateral view of the right shoulder of a mouse with a forceps pulling the latissimus dorsi muscle, revealing the TDA (C). Enlargement of the red box shown in C (D). Enlargement of the blue box in D (E). The purple box on the upper right shows a zoom in view of the TDA (Ar) surrounded by two veins (V) located on the caudal boarder of the scapula (designated by the arrow). Used with permission from Billaud et al. (32).

e. Uterine arteries.

The uterine arteries (UA) are the main conduits of blood to the uterus. During pregnancy, the UA ultimately branch into specialized vessels called spiral arteries, which carry maternal blood to the placenta to support fetal development. To meet the needs of the developing fetus, the UA must undergo dynamic changes to increase blood flow to the placenta. Multiple factors regulate the remodeling of the UA and a more thorough description of species-specific remodeling has been reviewed (33, 34).

The uterine artery is located along the medial margin of the uterus (Fig. 9). Mice and rats have a bicornate uterus with the main utero-ovarian (or parametrial) arteries running parallel to, but distant from the uterine wall within a sheet of connective tissue called the mesometrium. Isolation and dissection of these vessels is dependent on multiple factors: the estrous cycle (if isolating vessels in nonpregnant animals); the degree of branching of smaller arcuate arteries; the presence of the endothelium, which has a significant role in the adaptation of the UA during pregnancy; and most notably the stage of pregnancy. During pregnancy, the diameter of the main uterine artery increases 2–3-fold, with or without changes in vascular wall thickness. Experiments on the UA will require that the readers understand how UA respond to pregnancy in the studied model.

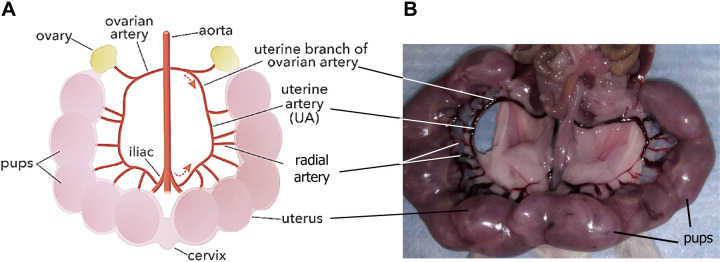

Figure 9.

Schematic of uterine artery bed from mice (A) (created with Biorender.com). Image shows uterine artery bed predissection (B). Lines indicate uterus, cervix, ovary, pups, and different arterial segments branched from ovarian arteries (A and B). Figure provided by Dr. Ramon A. Lorca at the Univ. of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus.

For the mouse model, it is recommended isolating arteries in ice-cold physiological salt solution or phosphate buffered saline using surgical tools (see description below). Although nonpregnant vessels are typically ∼250 µm in lumen diameter, UA are ∼600 µm in lumen diameter at day 18 of pregnancy (day 19.5 is day of delivery in C57BL/6 mice). For isolation of the UA, mice should be euthanized by using volatile anesthetics, or CO2 inhalation and cervical dislocation as a secondary euthanasia method. In pregnant animals, pups should be euthanized by decapitation, as they are more resistant to volatile anesthetics. After cleaning and disinfecting the abdominal skin, a midline laparotomy is performed to expose the uterus using surgical scissors. A fat pad lies along each uterine horn which contains the UA and uterine veins. Before dissecting out the UA, we identify the ovarian and cervical ends within the fat. Both UA and vein are dissected with the fat pad and placed in a petri dish with ice-cold physiological salt solution or phosphate buffered saline. To avoid damaging the vessel, pin down the vessels with two needles and using the fat tissue on each end as the anchor. Under a dissecting microscope and with the help of small forceps, the uterine veins and arteries can be identified. Generally, arteries have smaller diameters than veins and show a distinctive “white wall” surrounding them, due to the thicker VSMC layer present in the arteries. Both vessels should still contain blood in their lumen; however, only the blood in the vein should easily dissipate by gently pushing the vessel with the forceps. The distinction between uterine artery and vein may be harder in nonpregnant than pregnant animals due to the small size of the vessel. Once secured by the pins, the fat surrounding the UA can be carefully dissected from the blood vessels. Once the fat is removed, the vein can be easily separated. The UA can be cleaned by pulling and cutting away the remaining fat and connective tissue, the latter of which appears as a translucent membrane. It is recommended cleaning the entirety of the isolated UA (up to each anchoring pin) to ensure there is sufficient length for each study. Once cleaned and while still pinned down, the UA can be cut in small pieces according to their subsequent use. For pressure myography, it is recommended to cut ∼2–3-mm segments avoiding areas that contain branches of the arcuate arteries. If avoiding branches is not possible, the branches should be sutured, which could be challenging to accomplish in smaller vessels. For wire myography, 2-mm segments can be used and branches do not need to be sutured.

To study the role of endothelial factors, the endothelium can be removed before each experiment by passing air bubbles through the lumen and then flushing with Krebs buffer. Endothelial removal should be confirmed by a major loss, defined as less than 15%–10%, of vasorelaxation to 10 µM acetylcholine in vessels contracted with 15 mM KCl or 1–3 µM phenylephrine.

Practical tips: uterine arteries.

UA are highly dynamic and undergo vast changes in size and properties as pregnancy develops. Additionally, due to the role of the UA in supplying blood to the uterus, even in nonpregnant animals, it is subject to changes during the estrous cycle. Thus, if investigating the UA function in nonpregnant animals, please record the stage of estrus to better control the studies. If studies are performed on UA isolated during pregnancy, the stage of pregnancy should be recorded, as the baseline diameter will change due to the high degree of remodeling that occurs.

Tools: For dissection of uterine arteries, it is recommended to use sharp Dumont No. 5 forceps and 2-mm cutting edge Vannas spring scissors. Two ∼28–31-gauge needles are used to pin down the vessels into the dissection dish.

Dissection Dish: Due to the size of the UA, we recommend a low-profile plastic/glass petri dish with black Sylgard on the bottom. The dish should be filled with physiological salt solution at 4°C that covers the vessel. As described above, the vessels should be pinned down by the fat pad as close to the end of the vessels as possible.

Vessel Integrity: Due to the vast changes in the UA during pregnancy, great caution has to be taken to not stretch the UA or damage them by excessive manipulation.

Vessel Location during Dissection: The UA span the entirety of the uterus, and they are surrounded by fat. A helpful method of localizing them is to gently push the fat underneath the uterine horn, exposing the vessels (uterine veins will most likely be visible as they are bigger). Grab the fat and vessels with forceps and cut as close to the uterus as possible, from the top near the ovarian end of the uterus toward the cervical end, or vice versa, depending on the uterine side (left or right) and whether the researcher is right- or left-handed.

f. Pulmonary arteries.

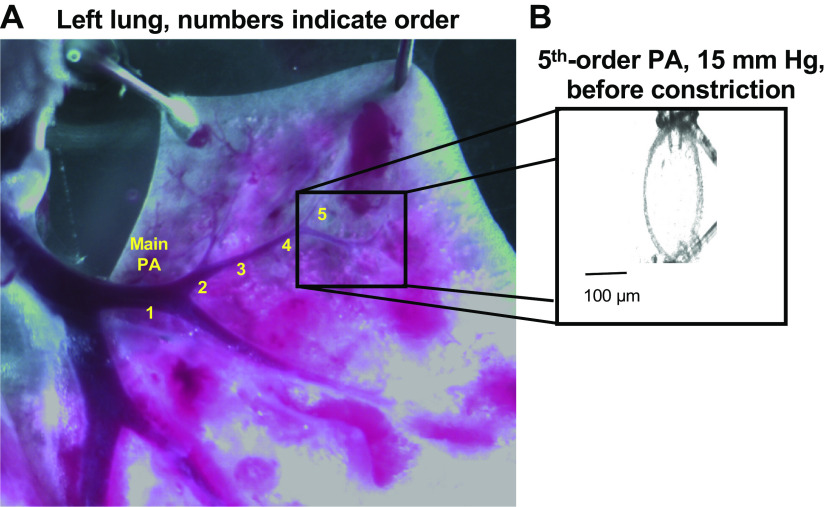

Pulmonary arteries are structurally and functionally very different from systemic arteries. They carry deoxygenated blood at a low intraluminal pressure of 10–15 mmHg. Because of the low intraluminal pressures, pulmonary arteries exhibit minimal myogenic constriction under normal conditions. As a result, most of the contractility studies on pulmonary arteries use pharmacological constrictors to generate constriction. Pulmonary arteries from rodent models of pulmonary hypertension, however, display robust myogenic constrictions. Arteries with an internal diameter of ∼50–100 μm are thought to be resistance-sized in the pulmonary circulation. In a mouse lung, this corresponds to fourth- or higher-order arteries (Fig. 10A). Most contractility studies on pulmonary arteries have been performed using wire myography. Pressure myography of pulmonary arteries is technically demanding due to several reasons. First, resistance pulmonary arteries are so well-embedded into the lung parenchyma that dissecting them out is challenging. The presence of blood inside the arteries makes it easier to visualize them. It is recommended that the heart remains connected to the lungs during the dissection. In case, your dissecting scope stage has a bottom illumination, you should turn it off to improve visibility of pulmonary arteries; only use the top illumination. The walls of resistance pulmonary arteries are thin. Therefore, the connective tissue around the arterial walls must be cleared very carefully to prevent damage to the arterial walls. To locate pulmonary arteries in a mouse lung, we first cut open the veins on the surface. This exposes the airway, which is directly underneath the veins and can be identified by air bubbles inside. Pulmonary arteries run alongside the airway. Cutting open the airway facilitates visualization of pulmonary arteries. Second, the extensive branching of pulmonary arteries means that only a short length of the artery is available for cannulation and pressurization without leaks. In a mouse lung, this corresponds to ∼200 microns between two branching points. Some of the branching points are too small to be seen during dissection. Therefore, as a standard practice, we recommend cannulating the arteries first, pressurize them to 15 mmHg (Fig. 10B), and then attempt to visualize any leaks due to branching points. After locating the leak points with this approach, the position of the ties on cannula can be adjusted to bypass the branching point.

Figure 10.

Image shows left lung and numbers indicate pulmonary artery (PA) divided into five branches (A). Please note that the lumen diameter of the fifth artery branch is ∼ 50 µm before cannulation and pressurization (A). Amplified image for a fifth-order PA cannulated at both ends (B).

Important considerations.

Resistance pulmonary arteries in pressure myography experiments display little to no dilation in response to the classical endothelium-dependent vasodilators acetylcholine and bradykinin. Moreover, they have shown significant differences in the localization patterns of endothelial vasodilator proteins in systemic and pulmonary arteries. Nitric oxide is the primary mediator of endothelium-dependent dilation in resistance pulmonary arteries. In systemic resistance arteries, endothelial nitric oxide synthase is present close to a NO scavenging protein hemoglobin α, limiting the role of NO in systemic resistance arteries. In the endothelium from pulmonary arteries, however, hemoglobin α is not observed. Moreover, endothelial calcium-activated potassium channels (KCa) are present at myoendothelial projections underling endothelium-derived hyperpolarization leading to vasodilation in systemic resistance arteries but not in pulmonary resistance arteries. This signaling arrangement explains the predominant role of NO in endothelium-dependent vasodilation in pulmonary resistance arteries but not in systemic resistance arteries.

g. Cerebral arteries.

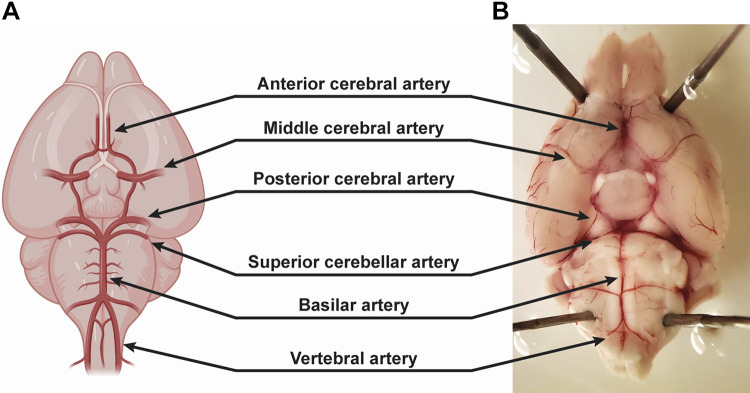

The cerebral circulation is highly specialized to support the metabolic demands of the brain. The arterial blood supply originates from the left and right vertebral arteries, and the left and right internal carotid arteries. The vertebral arteries join to form the basilar artery which supplies the cerebellum and brain stem. The basilar artery connects with the two internal carotids via intermediate communicating arteries to form a complete ring at the base of the brain known as the circle of Willis. Three pairs of major arteries arise from the circle of Willis to supply different parts of the cerebrum: the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries. These vessels further divide into progressively smaller arteries along the surface of the brain. Collectively, the surface vessels are termed pial arteries (Fig. 11). Smaller pial arteries eventually penetrate into the brain within the Virchow–Robin space to form parenchymal arterioles that feed the subsurface microcirculation. Parenchymal arterioles are a key component of the neurovascular unit, a structure that locally controls perfusion to match the metabolic activity of neurons. Parenchymal arterioles are structurally and functionally distinct from surface pial arteries. First, pial arteries contain approximately two to three layers of circumferentially oriented VSMC but parenchymal arterioles only have one layer. Functionally, parenchymal arterioles have greater myogenic reactivity but are unresponsive to certain contractile agonists (e.g., norepinephrine). Second, pial arteries are innervated by perivascular nerves of the peripheral nervous system, known as “extrinsic” innervation, whereas parenchymal arterioles are “intrinsically” innervated by surrounding neurons. Arterioles are also encased by astrocytic processes which can regulate blood flow. Lastly, unlike the surface pial arteries, parenchymal arterioles do not have a collateral system where an occlusion can result in significant reduction in blood flow and tissue damage.

Figure 11.

Anatomy of surface pial arteries (A and B). Created with Biorender.com.

Practical tips: cerebral arteries.

Most surface pial arteries are easy to remove and clean from the surrounding parenchyma. Although arteries can be peeled off the surface of the brain, this approach overstretches and damages vessels impacting the vascular response. We recommend using sharp Vannas spring scissors to cut the arteries away from the surrounding tissue, then carefully removing any excess remaining tissue. Unlike other pial arteries, the basilar artery and its branches are surrounded by an extensive amount of connective tissue and additional care is required to remove it.

Parenchymal arterioles are loosely connected to the surrounding tissue and are easy to separate from the parenchyma. For performing experiments on parenchymal arterioles arising from the middle cerebral artery, it is recommended to cut a section of the brain surrounding the middle cerebral artery (e.g., 3 mm W × 5 mm L × 3 mm D of a mouse brain), after use forceps to blunt dissect the parenchyma until the arterioles are identified and can be removed (Fig. 12). These vessels are small in diameter (∼20–70 µm) and may be difficult to identify at first. Blood trapped within the lumen can help visualize arterioles.

A separate method for isolating parenchymal arterioles is to gently peel away large surface arteries pulling the arterioles along with it. However, this method may overstretch and damage arterioles.

Figure 12.

A section of the brain cut around the middle cerebral artery and parenchymal arterioles are carefully dissected from this section (A). Image of a parenchymal arteriole (arrow) that is embedded within the parenchyma (B).

Brain slice preparation.

The use of brain slices for the study of neurovascular coupling has advanced the field by allowing investigators to address dynamic signaling events at the level of the neurovascular unit. In addition to providing direct visualization of blood vessels, this ex vivo preparation enables the use of fluorescence imaging and electrophysiological recordings, making it a powerful approach for assessing intercellular communication in health and disease. Here, we describe the steps used to assess parenchymal arteriole vascular reactivity in brain slices, focusing on the cannulated parenchymal arteriole preparation. Where applicable, we also highlight limitations of the technique.

The first studies addressing the properties of parenchymal arterioles in a brain slice were reported by Lovick et al. (35). These authors described an experimental approach in which a glass cannula was introduced into the lumen of small parenchymal arterioles, allowing them to be perfused (35). The system also included perfused arterioles with open ends. The authors concluded that the technique was challenging and cited the buildup of pressure within the perfused vascular network as a potential problem (35). Over the years, some of the limitations of the original technique by Lovick’s work were addressed. However, there are still challenges with the approach, and understanding its limitations has helped fine-tune the types of questions that can be explored using it. Below is a step-by-step description of the approach (Fig. 13), considerations that influence the success of the procedure, and discussion of data interpretation.

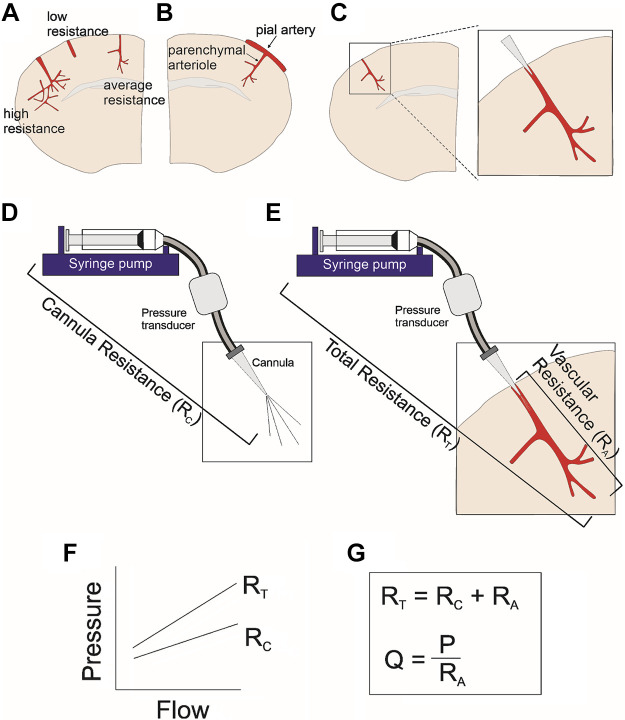

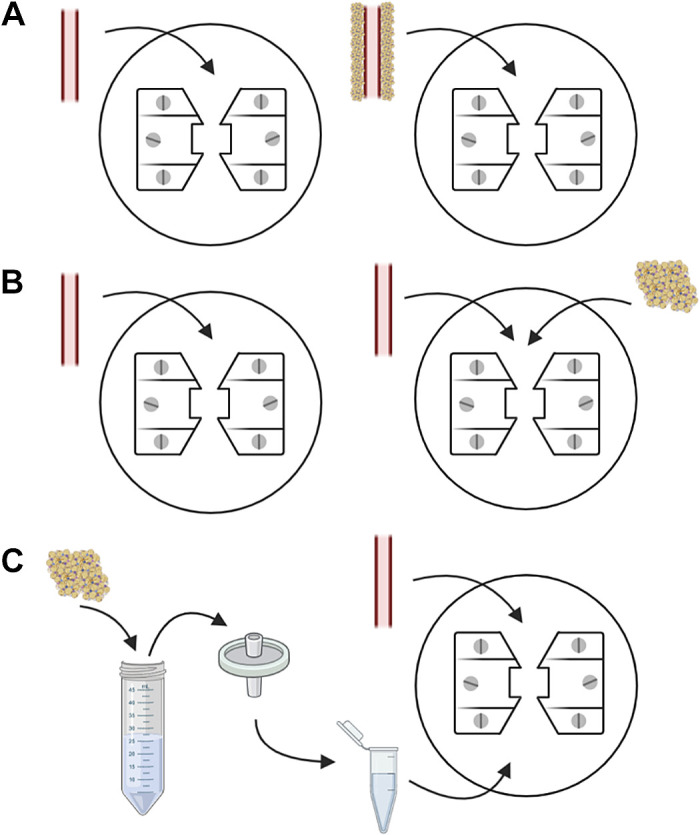

Figure 13.

Representative illustrations from a brain slice cannulation technique. A coronal brain slice with three parenchymal arteriole examples corresponding to a highly vascularized downstream network (high resistance), a short parenchymal arteriole (low resistance), and an averaged length and branched parenchymal arteriole (A). Coronal brain slice showing a pial arteriole with a branching downstream parenchymal arteriole not suitable for cannulation (B). The expanded imaged of an ideal cannulated parenchymal arteriole (C). The perfusion system which includes the syringe pump, pressure transducer, and cannula (D). Complete system which includes the perfusion system plus the vascular network (E). Example of the pressure-flow relationship corresponding to the experimental steps used to determine the resistance of the cannula (RC) as well as the resistance of the entire system (F). Equations used to determine the resistance of the vascular network (RA) as well as the equation used to determine the flow rate (Q) needed to bring the perfused system to a desired pressure (P) (G).

Brain slice cutting.

Brain slices from a region of interest must be cut in a manner that yields the highest number of arterioles. Thus, an understanding of the structural organization of the vascular bed within the brain region of interest before cutting is important. The orientation—coronal, horizontal, or sagittal—used for cutting should yield arterioles that run longitudinally with the tissue. Some of the work has mainly been performed in cortical (36–38) and hypothalamic (39) brain slices; thus, the following account focuses on cortical coronal brain slices.

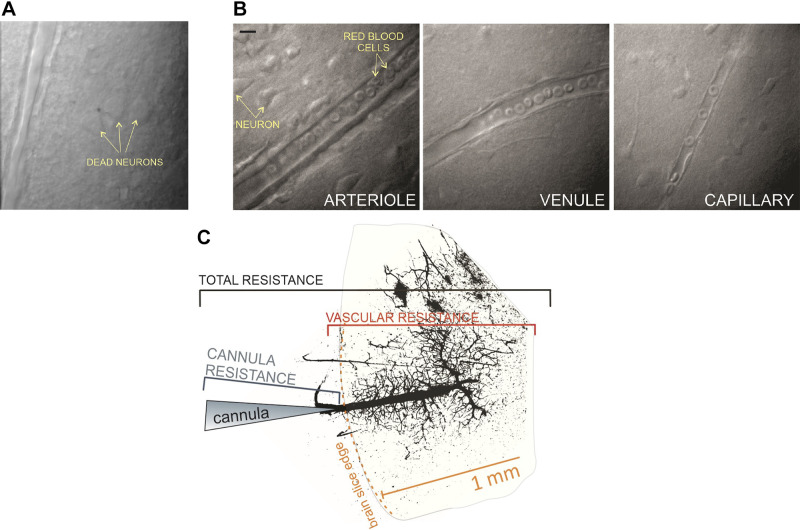

Brain slices are cut in ice-cold artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) (38) (Table 3) and placed in a chamber gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2. Immediately after cutting, slices are incubated for ∼30 min in 32–34°C gassed aCSF; this step aids in the recovery of neuronal membranes. Some laboratories use alternative solutions during cutting and/or recovery phase (40, 41). In any case, the details of these solutions should be clearly reported in each study to ensure the reproducibility of reported results. Slices are kept in the gassed chamber at room temperature (∼22°C) until they are used. For the experienced experimenter, the tissue remains viable for ∼6–9 h. Time is required to obtain good quality tissue; thus, the importance of this step should not be underestimated. Tissue viability can be determined by assessing the slice for the presence of dead neurons, which are clearly visible in the slice (Fig. 14A). Although it is normal to have a few dead cells at the surface, neurons one or more layers deeper into the tissue should appear healthy. We emphasize the importance of making these observations as the signaling modalities under investigation can be altered by the viability of the tissue. Appropriate timing of subsequent experimental assessments is also important. Most laboratories conducting brain slice experiments are equipped with an electrophysiological setup. Thus, an optimal way to determine the viability of the tissue is through neuronal electrophysiological recordings. Alternative methods could include measuring field potential in response to a known stimulus or measuring neuronal responses using imaging approaches. Although these techniques require considerable instrumentation, these positive control experiments can ensure that the tissue used throughout the experiment is viable.

Table 3.

Concentrations of compounds that make up aCSF that we recommend for the brain slice preparation

| Compound (Mol wt), g/Mol | aCSF, mM |

|---|---|

| NaCl (58.44) | 120.0 |

| KCl (74.55) | 3.0 |

| NaH2PO4 (119.98) | 1.25 |

| MgCl2 (95.21) | 1.0 |

| NaHCO3 (84.00) | 26.0 |

| Glucose (180.16) | 10.0 |

| CaCl2 (147.02) | 2.0 |

| l-Ascorbic acid (176.12) | 0.4 |

aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid.

Figure 14.

Representative image from a cortical brain slice showing the presence of dead neurons (A), and arteriole, venule, and a capillary (B). Calibration bar, 10 μm. Image shows cannulated arteriole labeled with FITC (postexperiment) to define the downstream vascular network and the factors that contribute to the total resistance of the system (C).

Temperature.

Temperature is an essential variable for physiological and homeostatic processes, including the development of tone (42); thus, room temperature experiments are discouraged. Ideally, experiments should be conducted at physiological temperatures, but this consideration is balanced against the fact that the viability of the metabolically active brain slice decreases with increasing temperature. Because a typical experimental protocol may last 1–2 h, running experiments at a slightly lower temperature (∼33 ± 1°C) can help preserve tissue viability.

Tissue oxygenation.

The use of hyperoxic conditions for experiments using brain slice preparations has been a continuing subject of discussion in the field (43–45). Notably, however, the metabolic requirements of the brain slice are different from those in vivo (44). The high PO2 used in brain slice experiments (95% O2) has been shown to maintain oxidative metabolism and thus satisfy the metabolic needs of activated neuronal populations (44). The lack of alternative energy substrates (e.g., lactate) in glucose-containing aCSF and possible alterations in the condition of the tissue and arteriolar tone due to vasoactive signals (e.g., adenosine) have proven to be important considerations in determining the role of neurons in neurovascular function. Thus, the metabolic state of the tissue, which may significantly differ from those observed in vivo, is important.

Calibration of the cannula.

Before cannulation of a parenchymal arteriole in a brain slice, the glass cannula needs to be calibrated by determining the pressure-flow relationship (Fig. 13D). The cannula is then submerged under the aCSF solution (at the microscope chamber) and subjected to stepwise increases in flow rate (four steps are recommended). The corresponding pressure at each flow rate is recorded and tracked with an acquisition system (e.g., pClamp). Successful myogenic responses are achieved when the cannula resistance (RC) is low [<25 arbitrary units (AU)]. Low cannula resistance, however, implies a larger tip opening, which makes introduction of the cannula into the small arteriole lumen (<30 µm) challenging. The success rate can be increased by beveling cannulas, and variability across experiments can be minimized by keeping RC within a narrow range (20 to 25 AU) (46).

Identification of an optimal arteriole for cannulation.

Once cannulas are calibrated, the brain slice is brought to the temperature-controlled microscope chamber. Arterioles in the slice are clearly distinguishable from venules by virtue of their single, circumferentially oriented VSMC layer. Venules and capillaries are characterized by their thin walls and considerably smaller diameters, respectively (Fig. 14B) (46). The ideal arteriole for cannulating has an opening just at the edge of the slice. Also, it is important that the parenchymal arteriole does not branch from a surface pial artery (Fig. 13B). Although it is considerably easier to cannulate the larger pial artery, the problem here is the significant decrease in flow at the distal end of these vessels, which causes a large pressure drop and thus prevents branching parenchymal arterioles from experiencing sufficient pressure to develop myogenic tone. Furthermore, an ideal arteriole is one that is long enough to cross all cortical layers, has considerable length in the same focal plane, and gives rise to a capillary network. It is also possible to visualize post-capillary venules. However, as discussed below, vascular network density/resistance considerations are important. Assuming a healthy tissue, a long arteriole and the presence of a downstream capillary network, the next step is introduction of the cannula into the lumen of the parenchymal arteriole. This is a delicate step requiring minimal arteriole manipulation. The edge of the arteriole is sticky, and the abluminal side of the vessel wall sometimes becomes stuck to the cannula; pulling the cannula away from the vessel in this situation may cause stretching of the arteriole wall and damage to the vessel. To achieve minimal contact with the vessel opening, it is helpful to provide a small amount of positive flow when approaching the arteriole opening with the cannula. When the positive flow causes the opening of the arteriole to enlarge, the tip of the cannula is moved from side to side at the open end, thereby aligning the cannula with the arteriole. At this point, the cannula is slowly introduced into the arteriole.

Determining the resistance of the vascular network.

Following the successful introduction of the cannula into the parenchymal arteriole (Fig. 13C), the next step is to determine the total resistance (RT) of the perfused system, comprising resistance of the cannula perfusion system (syringe pump + tubing + cannula), denoted RC, plus the resistance of the arteriolar network (arteriole + downstream capillaries), denoted RA (Fig. 13E). A second pressure-flow relationship is experimentally established using at least three flow rates. This step is essential because if arterioles are too short, they will not be able to maintain intravascular pressure and thus will not develop tone. This latter situation would be evidenced by a drop in pressure over time under constant flow rate conditions. On the other hand, if the cannulated arteriole has an extensive downstream vascular network, it may result in a high RT. Although arterioles with an extensive downstream vascular network are ideal, they are relatively uncommon. Thus, when such extreme conditions are encountered, it is best to continue looking for another arteriole with an RT value closer to average. An average RT value is ∼70 AU, whereas an RT value > 100 AU may indicate an extensive downstream vascular network [please see Fig. 2, A and B, in Kim et al. (46)]. Also, as noted by Lovick et al. (35), cases in which resistance progressively increases may indicate fluid buildup within the perfused network (35). Once the RT is determined and found to lie within an appropriate range, the arteriole is equilibrated to physiological pressure (∼30–40 mmHg). This step requires calculating the flow rate needed to bring the vascular network to the estimated desired pressure.

Arteriole pressurization.

After determining RC and RT, the next step is determining the resistance of the RA, defined as RT – RC. RA, calculated from Ohm’s law (P = Q·R), is used to determine the flow rate needed to bring arterioles to the desired intravascular pressure, where P is the desired pressure, RA is the resistance of the perfused vascular network, and Q is the flow rate. The same approach is used to achieve lower or higher intravascular pressure values. The flow rate is then set to the value needed and the vessel is allowed to equilibrate. Following equilibration, determined by establishment of a plateau pressure and thus diameter, the experiment can be started.

As noted above, an important limitation of the system is that the distal ends of the perfused network are open. Thus, at equilibrium, the plateau reflects the combined effects of inflow, outflow and leaks from the distal ends of the perfused network. Manipulating the intravascular flow rate will cause the pressure to fluctuate until a new equilibrium is achieved. Notably, the system cannot be used at very high flow rates because this will cause distal openings to expand, resulting in greater efflux and a drop in pressure.

Determining passive diameters.

A final step in the cannulation technique is determining the passive diameter of the cannulated arteriole. Because various flow rates may have been used depending on the protocol, at the end of the experiment, passive arteriole diameters are measured in the presence of zero Ca2+ plus papaverine at each flow rate used during the experiment. Of note, papaverine causes vasodilation for passive diameter measurement by nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibition (47).

Data analysis.

Images are acquired through video microscopy, typically at 1 frame/s. Diameter changes are extracted by processing image sequences using automated image software, such as Image J, for which share codes are now available. Automated approaches minimize experimenter bias potentially introduced during manual measurements of small diameter changes (e.g., 10%). Diameters can be measured at multiple points along the vessel wall and then averaged. The same approach is used to measure passive diameters. The passive diameter value at a given flow rate is then used to determine the active diameter or tone of the arteriole. A caveat here is that the intravascular pressures reported using this approach are estimates and not measured values (36). Equal flow rates (and not exact pressure values) are used to determine active and passive arteriole diameters. Thus, in the presence of Ca2+, the tone of the arteriole is expected to result in a slightly higher intravascular pressure than that generated by the same flow rate in zero Ca2+.

Exclusion criteria.

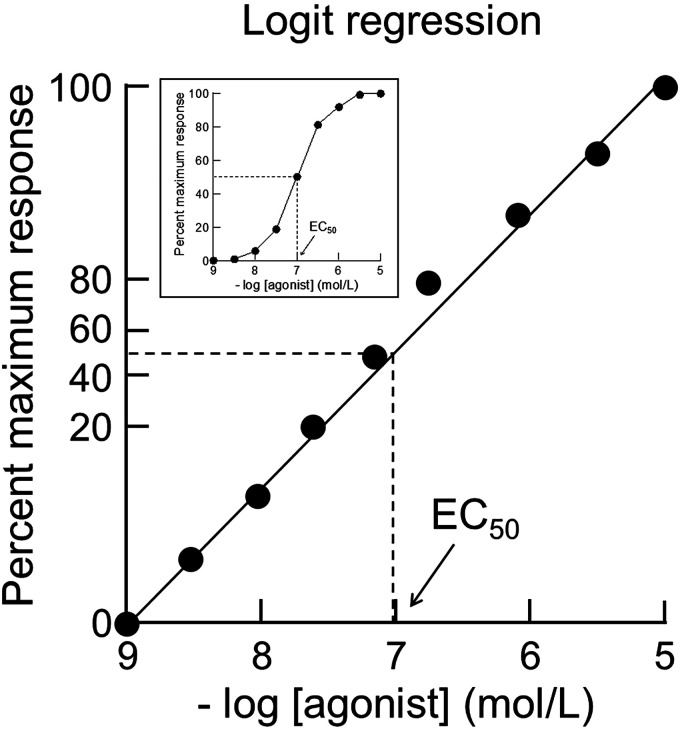

Given the challenges and limitations of the brain slice preparation, which on average yields one successful experiment per day per experimenter, it is essential that technical variabilities be minimized. For example, if the perfused arteriole network has above average RT reflecting a connected dense capillary network or below average RT owing to a short arteriole, the recommendation is to stop and look for another arteriole to cannulate before conducting the experiment. The experienced experimenter should track the length of the vessel and visually estimate the density of the perfused vascular network. Alternatively, a fluorescent dye (e.g., Alexa 488) can be added to the intraluminal solution, and the extent of the vessel network estimated based on visualization (Fig. 14C). It is important to avoid short vessels. Here, the efflux of the fluorescent solution is evident. Also, it is best to avoid arterioles with a dense vascular network as these are the exception. For quantification purposes, at the end of the experiment, the used slice with the corresponding stained perfused vasculature can be fixed, and the vascular density measured using image software (e.g., Image J, Vesselucida). Likewise, if RC is too high, the cannula would need to be changed. Conducting an experiment with a high RC requires high flow rates, which can significantly increase shear stress. In addition, in cases where RC is the main contributor to RT, the vessel might not develop tone at flow rates comparable to those that promote tone in other vessels. Thus, because many factors can result in outlier values that could significantly alter experimental conditions, care must be taken during the experiment and subsequent data interpretation. In summary, comparable RC and RT values between experiments and an RA contribution to RT greater than that of RC (preferably >50%) is recommended.