Keywords: CB1R, glucose metabolism, metabolic homeostasis, SR141716, VMH

Abstract

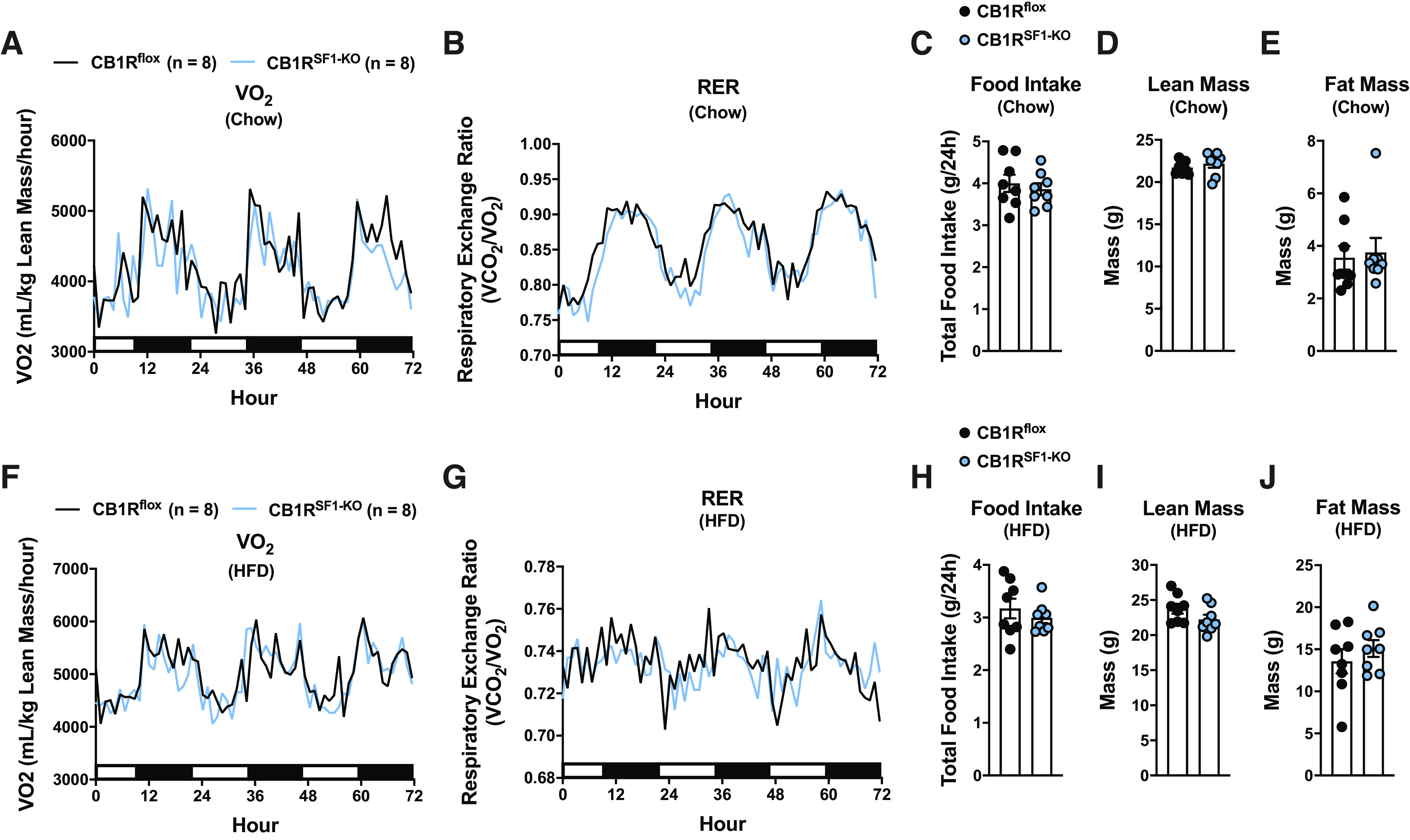

Cannabinoid 1 receptor (CB1R) inverse agonists reduce body weight and improve several parameters of glucose homeostasis. However, these drugs have also been associated with deleterious side effects. CB1R expression is widespread in the brain and in peripheral tissues, but whether specific sites of expression can mediate the beneficial metabolic effects of CB1R drugs, while avoiding the untoward side effects, remains unclear. Evidence suggests inverse agonists may act on key sites within the central nervous system to improve metabolism. The ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) is a critical node regulating energy balance and glucose homeostasis. To determine the contributions of CB1Rs expressed in VMH neurons in regulating metabolic homeostasis, we generated mice lacking CB1Rs in the VMH. We found that the deletion of CB1Rs in the VMH did not affect body weight in chow- and high-fat diet-fed male and female mice. We also found that deletion of CB1Rs in the VMH did not alter weight loss responses induced by the CB1R inverse agonist SR141716. However, we did find that CB1Rs of the VMH regulate parameters of glucose homeostasis independent of body weight in diet-induced obese male mice.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) regulate metabolic homeostasis, and CB1R inverse agonists reduce body weight and improve parameters of glucose metabolism. However, the cell populations expressing CB1Rs that regulate metabolic homeostasis remain unclear. CB1Rs are highly expressed in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH), which is a crucial node that regulates metabolism. With CRISPR/Cas9, we generated mice lacking CB1Rs specifically in VMH neurons and found that CB1Rs in VMH neurons are essential for the regulation of glucose metabolism independent of body weight regulation.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity contributes to the development of insulin resistance. Insulin resistance and the resulting impairments in glucose regulation are precursors for the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Thus, understanding the mechanisms responsible for regulating glucose homeostasis is of great importance.

The endocannabinoid system has received much attention with respect to obesity and T2DM. Cannabinoid 1 receptor (CB1R) expression is upregulated during obesity, and this increase can further exacerbate weight gain and insulin resistance (1–3). In addition, retrograde endocannabinoid signaling in the mediobasal hypothalamus is also enhanced in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice (4). Deleting CB1R, or treatment with nonspecific CB1R inverse agonists, improves insulin sensitivity and protects against diet-induced obesity (DIO) (1, 5, 6). However, drugs targeting CB1Rs have been shown to have deleterious side effects in humans (5, 7). This is likely due in part to the widespread distribution of CB1Rs throughout the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral tissues (6, 8). Further insights are required to develop next-generation CB1R-based therapies without the negative side effects of available drugs. The purpose of this study was to identify candidate sites of action that account for the beneficial effects of CB1R inverse agonists on weight loss and glucose homeostasis in DIO mice.

The ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH) regulates energy balance and glucose homeostasis (9–11). Although CB1R is highly expressed in the VMH (2, 12), VMH-specific deletions of CB1Rs have modest effects on body weight in mice (13). We set out to determine if CB1Rs of the VMH 1) are required for the weight loss effects of the CB1R inverse agonist SR141716 (a.k.a. Rimonabant) and 2) are required for the SR141716-induced improvements in glucose homoeostasis, independent of body weight.

Here, we used CRISPR/Cas9 technology to develop a mouse model allowing the conditional deletion of CB1R (CB1Rflox) in the presence of Cre-recombinase (Cre). We used this model to assess if deletion of CB1Rs from SF1-expressing neurons of the VMH is required for CB1R inverse agonist-induced improvements in glucose homeostasis mice with DIO. We found that CB1Rs of the VMH do not regulate body weight in mice when fed chow or HFD, regardless of sex. However, we did find that CB1Rs of the VMH regulate fasting glucose levels in male mice with DIO.

METHODS

Animal work was approved and conducted under the oversight of the UT Southwestern Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Male mice were housed at 23 ± 1°C and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on 0700–1900). Mice were provided with ad libitum access to standard rodent chow diet (Harlan, Teklad Global 16% Protein Rodent Diet 2016; 12% kcal from fat, 3 kcal/g), or HFD (60% kcal from fat, Research Diets D12492). For both chow- and HFD-fed mice, all experiments were performed between 15 and 20 wks of age, unless stated otherwise.

Animal Models

Generation of CB1Rflox/flox mice (CB1Rflox) on C57BL/6 background was performed as previously described (14, 15). Two CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNAs were used to target upstream (5'-tctgggtgaggagacatgcctgg-3') and downstream (5'-agtctatcgctgcagttgctcgg-3') of exon 2 of the Cnr1 allele, flanking the coding sequence. Guides were selected using the CRISPR Design Tool (http://tools.genome-engineering.org). Cas9 mRNA and gRNA complexes containing the loxP site sequences were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). The UT Southwestern Transgenic Technology Center then injected the Cas9 mRNA and each gRNA into single-cell C57BL/6N embryos, which were then implanted into pseudopregnant mice. Founders containing the dual insertion of the loxP sites were identified via PCR for the upstream (5'-agattagcacagaggcttat-3' and 5'-ataagcctctgtgctaatct-3') and downstream locations (5'-tctgggtgaggagacatgcc-3' and 5'-ggcatgtctcctcacccaga-3'), and then bred with C57BL/6J mice to validate germinal transmission. Offspring heterozygous for the Cnr1 floxed allele (CB1Rflox/–) were bred to produce mice homozygous for the floxed allele (CB1Rflox/flox = CB1Rflox). To confirm that the CRISPR/Cas9 insertion of loxP sites into the Cnr1 allele are functional, we bred CB1Rflox mice with ZP3-Cre mice to induce the whole body deletion of CB1R (CB1RΔ/Δ) (16). We then bred CB1Rflox mice with mice expressing Cre-recombinase under the control of the SF-1 promotor (SF1-Cre) (17), to delete CB1Rs from SF1 expressing neurons of the VMH (CB1RSF1-KO). To confirm site-specific deletion of CB1R in SF1-neurons, RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) was performed as previously described (18). The ISH probe for CB1R was transcribed from PCR fragments amplified using the following primers: forward, 5'-ctgcaagaagctgcaatctg-3' and reverse, 5'-tggcgatcttaacagtgctc-3'. Genotyping for CB1Rflox and CB1RSF1-KO was performed using the following primers: 5'-accaccttcctcatgttaacct-3', 5'-gaccagagacagctccaga-3', and 5'-tgagggctatattctgtttttgc-3' (WT 195 bp; Flox 233 bp; Delta 480 bp).

The effects of DIO were tested in both male and female mice. Standard chow was replaced with HFD (60% kcal fat, Research Diets: D12492) beginning at 8–12 wks of age. Male mice were fed HFD for a minimum of 7 wks before performing experiments. Duration of HFD feeding for a given experiment is indicated in the respective methods section below. Female mice began HFD feeding at 11–15 wks of age and were fed HFD for a minimum of 9 wks before performing experiments.

Glucose Tolerance Test and CB1R Inverse Agonist Treatment

Male mice were fed HFD for 8 wks before a glucose tolerance test (GTT) (intraperitoneal injection of dextrose; 1 g/kg). On the day of the GTT, mice were fasted for 5 h, beginning with lights on. Blood glucose from the tail vein was measured using a handheld glucometer (Bayer’s Contour Blood Glucose Monitoring System; Leverkusen, Germany). Blood for insulin and glucagon measurements were collected from the tail via heparinized capillary tubes (Cat. No. 22-362-566, Fisher Scientific), treated with aprotinin (Cat. No. BP2503-10, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and centrifuged at 4,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Plasma was stored at –80°C until analysis. After 11 wks of HFD, mice were given the CB1R inverse agonist SR141716 (Cat. No. 0923; Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) for 5 days intraperitoneally (10 mg/kg in saline with 3% DMSO and 1% Tween-80). On the 5th day, mice were given the fifth injection of SR141716 2 h before the start of the GTT.

Metabolic Cages (Indirect Calorimetry)

A combined indirect calorimetry system (LabMaster with CaloSys Calorimetry System, TSE Systems Inc.) was used for all metabolic studies. HFD-fed mice were 9–13 wks old at the start of HFD feeding. Mice were group housed and fed HFD for 16 wks before metabolic cage assessments. CB1Rflox and CB1RSF1-KO littermates (22–30 wks old) were fed either chow or HFD, individually housed, and acclimated for 5 days in a metabolic chamber with ad libitum access to food and water. Following the acclimation period, oxygen consumption (Vo2), carbon dioxide production (Vco2), respiratory exchange ratio (RER), food and water intake, and cage activity were measured.

Insulin and Glucagon ELISAs

Plasma insulin (Cat. No. 80-INSMR-CH01, ALPCO, Salem, NH) and glucagon (Cat. No. 10-1281-01, Mercodia Inc., Winston Salem, NC) concentrations were determined by ELISA according to manufacturers’ instructions.

Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamps

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps were performed on mice that were fed HFD for a total of 7 wks beginning at 8 wks of age. During the clamp procedure, mice were conscious and unrestrained and the glucoses were “clamped” at 170 ± 4 mg/dL as previously described (19, 20).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total hepatic mRNA was isolated as previously described (21). The RNA concentrations were estimated from absorbance at 260 nm. cDNA synthesis was performed using a High Capacity cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems). mRNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed following the manufacturers’ instructions. cDNA was diluted in DNase-free water before quantification by real-time PCR. mRNA transcript levels were measured in duplicate samples using an ABI 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The relative amounts of all mRNAs were calculated using the ΔΔCT assay. TaqMan gene expression assays for 18S (Hs99999901_s1), B2m (Mm00437762_m1), Cnr1 (Mn01212171_s1), G6pc (Mm00839363_m1), Gys2 (Mm01267381_g1), Fgf21 (Mm00840165_g1), and Pck1 (Mm01247058_m1) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Statistical Analysis

The data are represented as either mean or means ± SE as indicated in each figure legend. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t test. GraphPad PRISM (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used for the statistical analyses, and P < 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

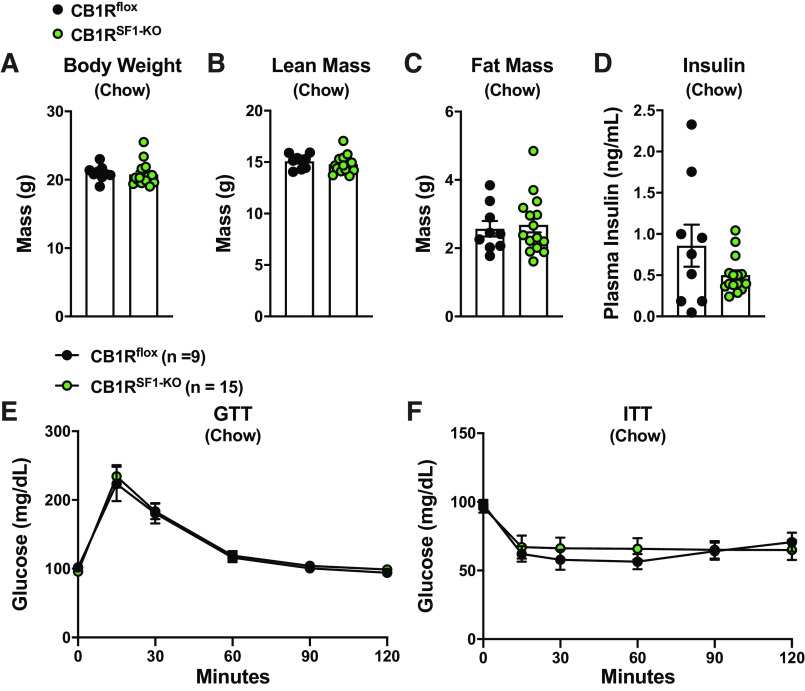

Generating CB1R Conditional Knockout Mouse

We used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to precisely insert loxP sites into the Cnr1 allele and generate a conditional CB1R knockout model (CB1Rflox). Mice with whole body deletion of CB1R (CB1RΔ/Δ) was confirmed via the absence of Cnr1 expression (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. S1; all Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14638188). CB1Rflox mice were then bred with SF1-Cre mice to delete CB1Rs from SF1-expressing neurons (CB1RSF1-KO). Compared with littermate control CB1Rflox mice, CB1RSF1-KO mice had substantial reductions in Cnr1 mRNA expression in the VMH as assessed by ISH (Fig. 1, B and C). SF1 is also expressed in other organs including the pituitary gland, adrenal gland, and gonads (22). We therefore measured Cnr1 mRNA expression in those peripheral tissues. We found no significant differences in Cnr1 mRNA expression in the pituitary gland and testis (Supplemental Fig. S2), but Cnr1 mRNA expression in the adrenal gland was significantly lower in CB1RSF1-KO mice than control mice (Supplemental Fig. S2). SF1 is expressed in the cortex of the adrenal gland (22), where corticosterone is produced. As corticosterone is important for glucose metabolism, we measured blood corticosterone and other endocrine hormones secreted from the pituitary gland, adrenal gland, and gonads. Blood corticosterone, testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone levels were comparable between CB1RSF1-KO and control WT mice (Supplemental Table S1). Further, we did not observe any gross morphological abnormalities of the pituitary gland, adrenal gland, and testis (Supplemental Fig. S3). Collectively, we concluded that the metabolic phenotypes in CB1RSF1-KO mice described in this study likely resulted from ablation of CB1R in the VMH.

Figure 1.

Generation of conditional cannabinoid 1 receptor (CB1R) knockout mice. A: validation of CB1Rflox/flox × ZP3-Cre (germline Cre) offspring resulting in global CB1R deletion (CB1RΔ/Δ) as assessed by Cnr1 expression in the brain, epididymal white adipose tissue (WATe), inguinal white adipose tissue (WATi), and gastrocnemius (GAS). CB1R-specific deletion of CB1R from SF1-neurons shown by in situ hybridization (ISH) of Cnr1 mRNA expression. ISH staining indicated by silver grains (black areas/dots) in coronal brain section from (B) CB1Rflox and (C) CB1RSF1-KO mice. The ventromedial hypothalamus is highlighted by the red dashed box. KO, knockout; WT, wild type. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE. **P < 0.01 between genotypes, assessed by unpaired Student’s t test.

Glucose Regulation

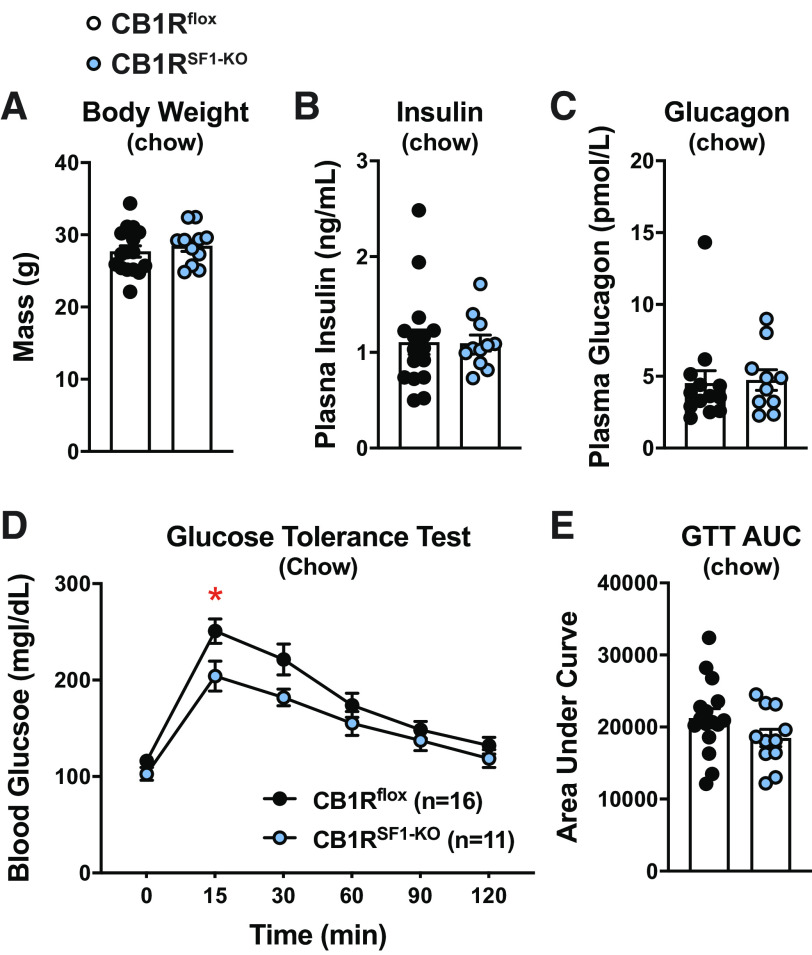

Chow-fed CB1Rflox and CB1RSF1-KO mice did not display any differences in body weight (Fig. 2A). Fasting plasma insulin or glucagon levels were also comparable between the genotypes (Fig. 2, B and C). During a GTT, CB1RSF1-KO mice had a modest improvement blood glucose compared with control CB1Rflox mice only at the 15-min time-point (Fig. 2D). However, the overall GTT was not improved in males fed HFD, as indicated by the area under the curve (AUC; Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Deletion of cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) in the ventromedial hypothalamus does not alter body weight in chow-fed male mice. Body weight (A), fasting plasma insulin (B), fasting plasma glucagon values (C), glucose tolerance test (GTT; D), and GTT area under the curve (AUC; E) from 11- to 14-wk-old males. Results shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, between genotypes, assessed by unpaired Student’s t test.

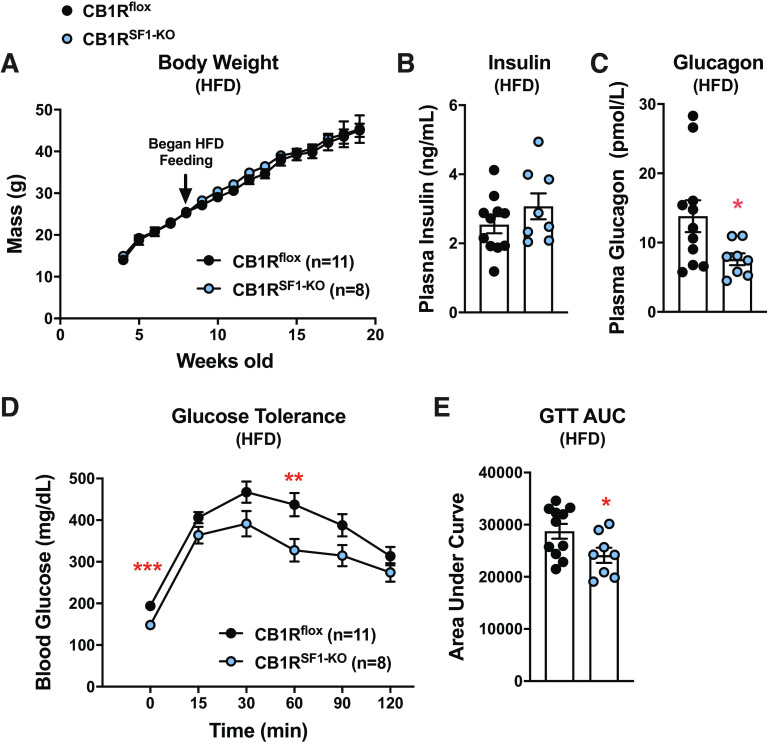

There were no differences in weight gain or plasma insulin levels between genotypes (Fig. 3, A and B). Interestingly, plasma glucagon was significantly lower in CB1RSF1-KO versus CB1Rflox mice (Fig. 3C). HFD-fed CB1RSF1-KO mice also had significantly lower basal glucose levels and improved GTT compared with CB1Rflox mice (Fig. 3, D and E).

Figure 3.

Cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) in the ventromedial hypothalamus regulate basal glucose levels independent of the body weight of male mice. A: body weight curves for CB1Rflox versus CB1RSF1-KO, start of high-fat diet (HFD) feeding indicated by arrow. Following 8–9 wks of HFD feeding, glucose tolerance tests (GTT; B), area under the curve (AUC) for the GTT (C), fasting plasma insulin (D), and fasting plasma glucagon values (E). Results shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 between genotypes, assessed by unpaired Student’s t test.

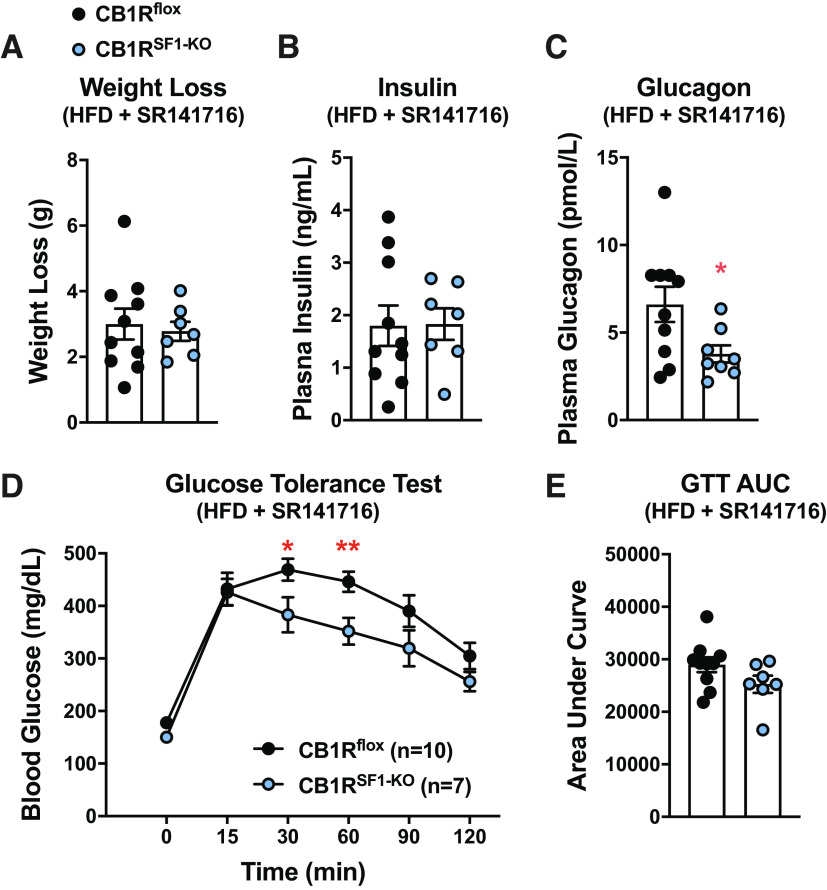

Weight loss induced by SR141716 was indistinguishable between genotypes. (Fig. 4A). Although fasting insulin was comparable between genotypes (Fig. 4B), plasma glucagon levels remained significantly lower in the CB1RSF1-KO mice following SR141716-induced weight loss (Fig. 4C). Blood glucose levels during a GTT assay also remained significantly lower in CB1RSF1-KO male mice fed HFD following SR141716 treatment (Fig. 4D). However, the overall GTT was not improved in males fed HFD, as indicated by the AUC (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Deletion of cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) in the ventromedial hypothalamus does not alter the efficacy of CB1R inverse agonist SR141716. After 11 wks of HFD, daily injections of Rimonabant (SR141716) were administered for 5 days (IP injections, 10 mg/kg). Weight loss (A), fasting plasma insulin (B), fasting plasma glucagon (C), glucose tolerance test (GTT; D), and area under the curve (AUC; E) for the GTT were determined. Results shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 between genotypes, assessed by unpaired Student’s t test. HFD, high-fat diet.

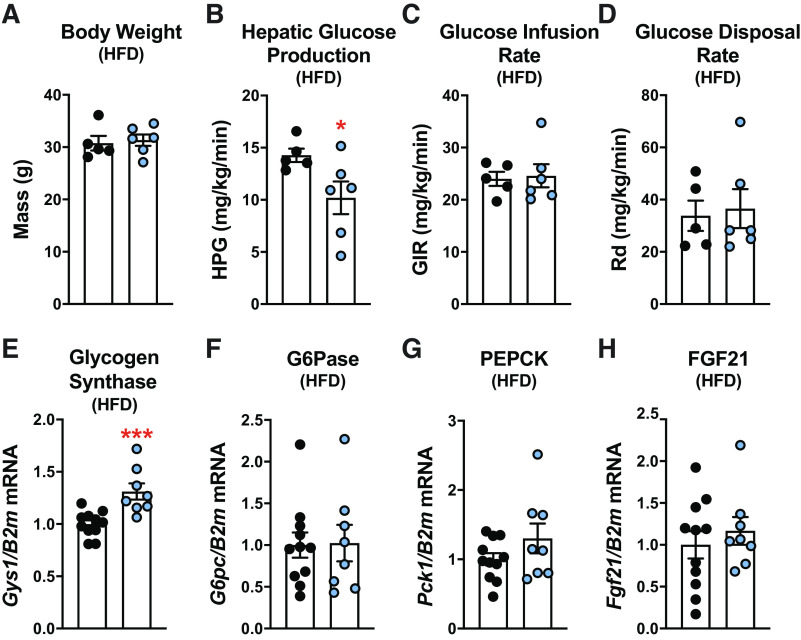

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp experiments were performed on a separate cohort of CB1RSF1-KO mice and littermate controls. We found again there was no difference in body weight between them (Fig. 5A). CB1RSF1-KO mice had significantly lower baseline hepatic glucose production (Fig. 5B). During the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, there were no differences in either the glucose infusion rate (GIR) or the rate of glucose disposal (Rd) between the groups (Fig. 5, C and D). We observed significant increases in hepatic glycogen synthase (Gys) expression, whereas glucose-6-phosphatase (G6pc), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK; Pck1), and fibroblast growth factor 21 (Fgf21) expression remained unchanged (Fig. 5, E–H).

Figure 5.

Deletion of cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) in the ventromedial hypothalamus lowers the hepatic glucose production in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed male mice. A: body weight after 8 wks of HFD feeding. B: basal hepatic glucose production (HPG). Insulin sensitivity was determined by hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps to assess the glucose infusion rate (GIR; C) and the rate of glucose disposal (Rd; D). Hepatic gene expression of glycogen synthase (Gys2; E), glucose 6 phosphatase (G6Pase; G6pc; F), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK; Pck1; G), and fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21; Fgf21; H). Mice were 16–18 wks old at the time of experiments. Results shown as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, between genotypes, assessed by unpaired Student’s t test.

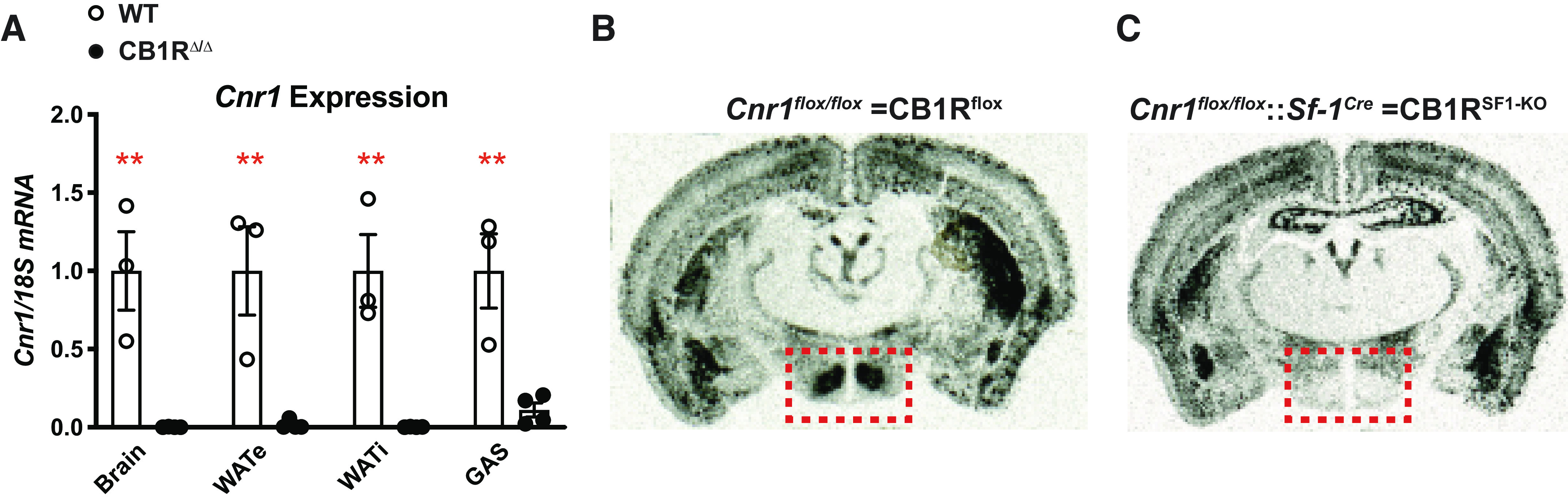

Indirect Calorimetry

Indirect calorimetry was performed on a cohort of chow-fed CB1Rflox and CB1RSF1-KO mice. Consistent with our previous cohorts, there were no differences in body weight (CB1Rflox = 29.6 ± 0.5 g and CB1RSF1-KO = 30.3 ± 0.4 g). Mice had similar oxygen consumption (Vo2) and substrate utilization (RER; Fig. 6, A and B), and there were also no differences in food intake or body composition (Fig. 6, C–E).

Figure 6.

Deletion of cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) in the ventromedial hypothalamus does not alter energy expenditure in chow- or high-fat diet (HFD)-fed male mice. Indirect calorimetry measurement of chow-fed mice: oxygen consumption (Vo2; A) and respiratory exchange ratio (RER; B). C: the mean 24 h food intake for the 72 h of indirect calorimetry measurements. Body composition for chow-fed mice: lean mass (D) and fat mass (E). The mean indirect calorimetry measurement of mice fed HFD for 8–9 wks: oxygen consumption (Vo2; F) and respiratory exchange ratio (RER; G) for mice fed HFD. H: the mean 24-h food intake for the 72 h of indirect calorimetry measurements. Body composition for HFD-fed mice: lean mass (I) and fat mass (J). Chow- and HFD-fed mice were 16–18 wks old at the time of experiments. For A, B, F, and G, the 12-h lights on (open bar) and 12-h lights off (closed bar) cycles are represented on the x-axis. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE.

Indirect calorimetry was also performed on a separate cohort of HFD-fed CB1Rflox and CB1RSF1-KO mice. Body weight was similar between genotypes (CB1Rflox = 41.7 ± 0.7 g and CB1RSF1-KO = 41.4 ± 1.2 g). HFD-fed CB1Rflox and CB1RSF1-KO mice also had similar oxygen consumption and substrate utilization (Fig. 6, F and G) and no differences in food intake or body composition (Fig. 6, H–J).

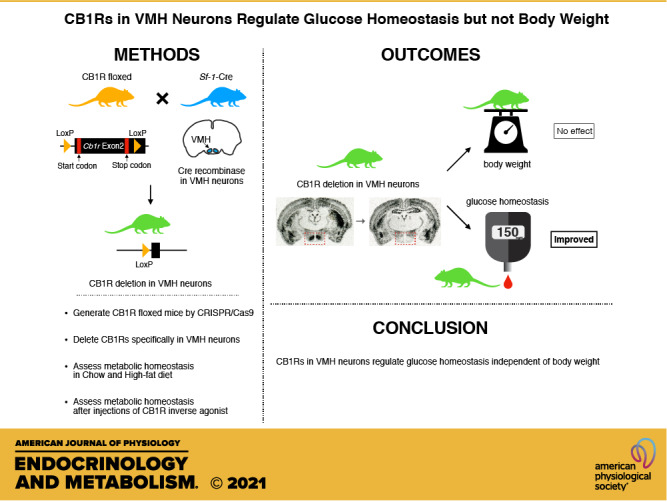

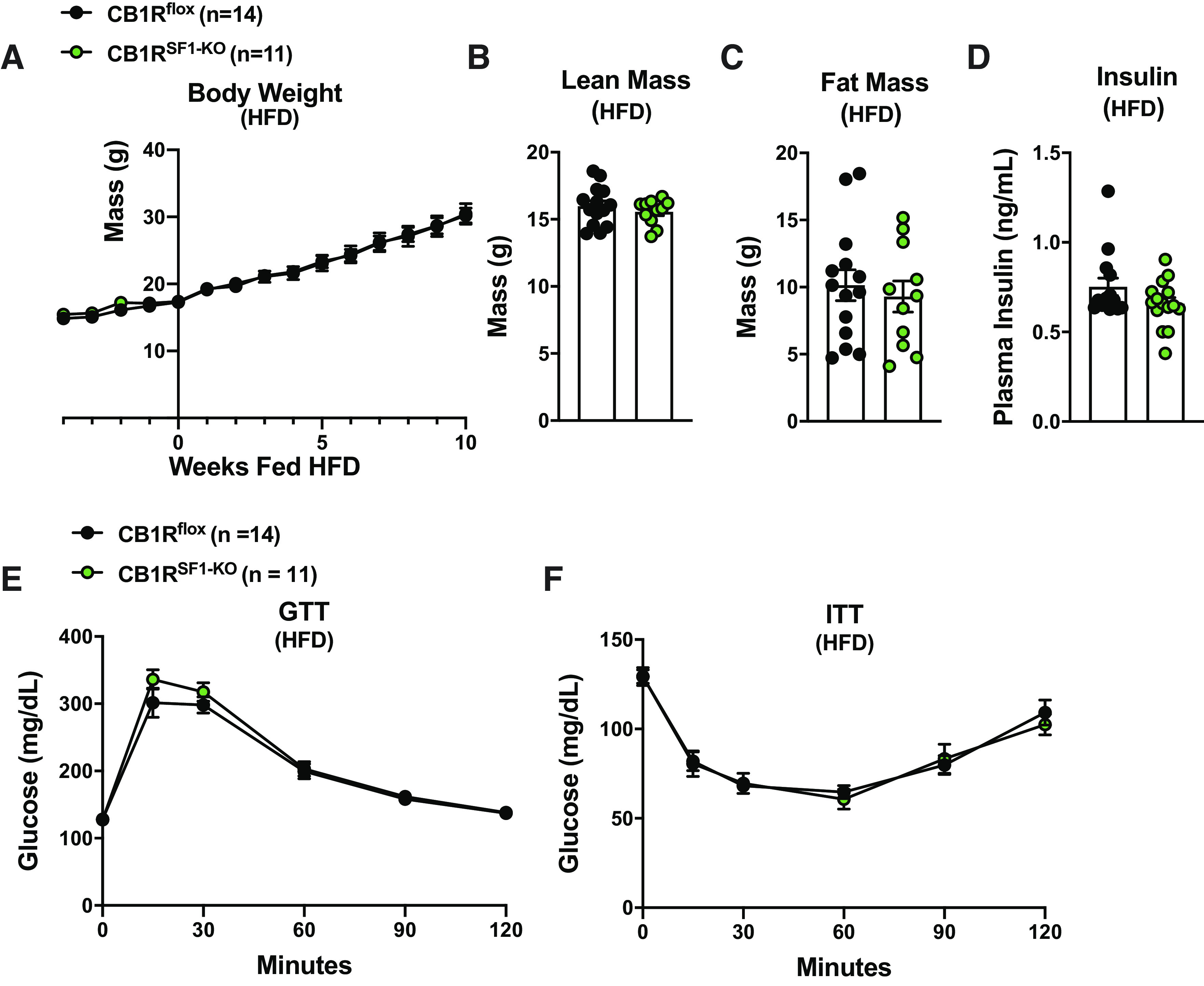

Female CB1Rflox and CB1RSF1-KO Mice

In chow-fed females, there were no differences in body weight, body composition, GTT, insulin tolerance test (ITT), or plasma insulin between CB1Rflox and CB1RSF1-KO littermates (Fig. 7, A–F). Likewise, genotype did not affect body weight, body composition, GTT, ITT, and plasma insulin (Fig. 8, A–F) in HFD-fed female mice.

Figure 7.

Deletion of cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) in the ventromedial hypothalamus does not alter body weight in chow-fed female mice. Body weight (A), lean mass (B), fat mass (C), fasting plasma insulin (D), glucose tolerance test (GTT; E), and insulin tolerance test (ITT; F) from 24- to 27-wk-old female mice. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE.

Figure 8.

Deletion of cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) in the ventromedial hypothalamus does not alter body weight in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed female mice. A: body weight curve; HFD is given starting at wk 0. Lean mass (B), fat mass (C), fasting plasma insulin (D), glucose tolerance test (GTT; E), and insulin tolerance test (ITT; F) from 20- to 24-wk-old female mice. Results shown as mean ± SE.

DISCUSSION

CB1Rs have been extensively studied with regard to the regulation of metabolism, but the role of CB1Rs within specific neuronal populations is still being deciphered. In the current study, we developed a conditional knockout of CB1R utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 technology. We found that deleting CB1R from the SF1-expressing neurons of the VMH regulates basal glucose levels independent of body weight in HFD-fed male mice. We determined that CB1Rs of the VMH do not regulate body weight in mice fed chow diet or HFD, regardless of sex, and are not required for the weight loss effects induced by the CB1R inverse agonist SR141716. From these experiments, we conclude that next-generation CB1R antagonist therapies should be focused on sites outside of the VMH to target weight loss.

Our results further confirm the importance of the VMH for regulating glucose levels (11, 23). More specifically, we provided additional evidence for SF1 neurons of the VMH in regulating glucose homeostasis independent of body weight (24–26). Consistent with the previous literature (13), we found that weight matched, HFD-fed CB1RSF1-KO male mice had significantly lower basal glucose levels compared with CB1Rflox littermate controls. This decrease in basal glucose likely accounts for the improvements in GTT seen in CB1RSF1-KO mice. This was substantiated by our findings that HFD-fed CB1RSF1-KO mice also had reduced fasting plasma glucagon and basal hepatic glucose production, yet no difference in insulin-mediated glucose disposal during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp studies. We speculate that these results may be due to altered hepatic glycogen synthesis as we found increased expression of glycogen synthase. The direct mechanism by which CB1Rs of the VMH coordinate hepatic glucose production, and why this occurs in males, but not female mice, warrants further investigation. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies showing that genetic manipulations within SF1-neurons have minimal or no effects in chow-fed mice but are exaggerated with HFD (10, 13, 17, 27–37). This further supports a role for SF1-neurons in responding to metabolic challenges.

The primary aim of this study was to determine if CB1Rs of the VMH are required for the weight loss induced by the CB1R inverse agonist SR141716. We found that the deletion of CB1R from the VMH did not alter susceptibility to DIO, nor did it affect SR141716-induced weight loss.

Although a similar study using mice generated by breeding Tg(Nr5a1-cre)7Lowl and Cnr1tm1.1Xiaz was conducted by Cardinal et al. (13), there are several notable differences between our findings. Cardinal et al. (13) reported that chow-fed mice with deletion of CB1R from SF1-neurons of the VMH had improved glucose tolerance, despite no differences in body weight. They attributed this improvement to a modest reduction in adiposity associated with increased energy expenditure. In contrast, we found no differences in body composition regardless of diet in male mice. Cardinal et al. also reported that HFD-fed mice lacking CB1Rs in the VMH had impaired glucose tolerance that was associated with increased adiposity. In contrast, we did not observe any differences body weight or composition among HFD-fed male mice and improved glucose tolerance resulting from lower basal glucose levels. Consistent with our lack of observed differences in body composition, our indirect calorimetry measurements are not different between genotypes. Although the previous study only investigated males, we found that there was no difference in susceptibly to DIO in either males or females lacking CB1Rs from SF1-neurons. However, we did identify a sex difference with respect to glucose homeostasis. We also extended the initial studies to demonstrate that CB1Rs of the VMH are not required for the weight loss effects of SR141716. The differences that we noted between the two studies may be due to the differences in diet composition, housing conditions, or genetic background. It should be noted that multiple mouse models with specific genetic manipulations of SF1-neurons have been reported (17, 28–30, 33, 34, 36–38). These studies all show that under chow-fed conditions, manipulating genes specifically in SF1-neurons of mice results in modest, or no phenotype. However, when metabolically challenged, the phenotype either becomes apparent or is exaggerated compared with the chow-fed counter parts.

In summary, our findings indicate that the loss of CB1R within SF1-neurons does contribute to the regulation of circulating glucose levels by affecting glucagon levels and resulting in reduced hepatic glucose production. CB1Rs within SF1-neurons do not play a role in the regulation of body weight, body composition, or energy expenditure in chow- or HFD-fed mice, regardless of sex. In addition, CB1Rs within SF1-neurons are not required for the Rimonabant-induced weight loss effects in DIO mice. In the context of assessing the potential roles for next-generation CB1R therapies, targeting SF1-neurons represent a potential avenue for improving glucose regulation. However, other sites of CB1R expression remain to be identified with respect to body weight regulation and insulin-stimulated glucose disposal.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Table S1 and Supplemental Figs. S1–S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14638188.

GRANTS

We thank the NIH for its support (R01 DK1006559 to J.K.E.; K01 DK111644 to C.M.C.; R01 DK114036 to C.L.). A.C. was a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Banting postdoctoral fellow (393318). C.L. was also supported by the American Heart Association (SDG27260001).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.M.C., C. Liu, T.F., and J.K.E. conceived and designed research; C.M.C., M.G., S.W., J.D.H., W.L.H., C. Lee, T.F., A.C., N.J.M., N.I.A., A.G.A., J.L., C. Limboy, C. Liu, and A.S.T. performed experiments; C.M.C., W.L.H., S.L., C. Liu, T.F., J.K.E., and A.C. analyzed data; C.M.C., T.F., J.K.E., and A.C. interpreted results of experiments; C.M.C. and T.F. prepared figures; C.M.C. drafted manuscript; C.M.C., S.L., C. Liu, T.F., J.K.E., and A.C. edited and revised manuscript; C.M.C. and J.K.E. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staff of the University of Texas Southwestern Metabolic Phenotyping Core.

REFERENCES

- 1.Engeli S. Central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors as therapeutic targets in the control of food intake and body weight. Handb Exp Pharmacol: 357–381, 2012. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24716-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunos G. Understanding metabolic homeostasis and imbalance: what is the role of the endocannabinoid system? Am J Med 120: S18–S24, 2007. Discussion S24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quarta C, Mazza R, Obici S, Pasquali R, Pagotto U. Energy balance regulation by endocannabinoids at central and peripheral levels. Trends Mol Med 17: 518–526, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabelo C, Hernandez J, Chang R, Seng S, Alicea N, Tian S, Conde K, Wagner EJ. Endocannabinoid signaling at hypothalamic steroidogenic factor-1/proopiomelanocortin synapses is sex- and diet-sensitive. Front Mol Neurosci 11: 214, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christopoulou FD, Kiortsis DN. An overview of the metabolic effects of Rimonabant in randomized controlled trials: potential for other cannabinoid 1 receptor blockers in obesity. J Clin Pharm Ther 36: 10–18, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2010.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy D, Rader D. Endocannabinoid antagonism: blocking the excess in the treatment of high-risk abdominal obesity. Trends Cardiovasc Med 17: 35–43, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg BA, Cannon CP. Cannabinoid-1 receptor blockade in cardiometabolic risk reduction: safety, tolerability, and therapeutic potential. Am J Cardiol 100: 27P–32P, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quarta C, Bellocchio L, Mancini G, Mazza R, Cervino C, Braulke LJ, Fekete C, Latorre R, Nanni C, Bucci M, Clemens LE, Heldmaier G, Watanabe M, Leste-Lassere T, Maitre M, Tedesco L, Fanelli F, Reuss S, Klaus S, Srivastava RK, Monory K, Valerio A, Grandis A, De Giorgio R, Pasquali R, Nisoli E, Cota D, Lutz B, Marsicano G, Pagotto U. CB(1) signaling in forebrain and sympathetic neurons is a key determinant of endocannabinoid actions on energy balance. Cell Metab 11: 273–285, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujikawa T, Castorena CM, Lee S, Elmquist JK. The hypothalamic regulation of metabolic adaptations to exercise. J Neuroendocrinol 29: e12533, 2017. doi: 10.1111/jne.12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KW, Sohn JW, Kohno D, Xu Y, Williams K, Elmquist JK. SF-1 in the ventral medial hypothalamic nucleus: a key regulator of homeostasis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 336: 219–223, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimazu T, Minokoshi Y. Systemic glucoregulation by glucose-sensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH). J Endocr Soc 1: 449–459, 2017. doi: 10.1210/js.2016-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsicano G, Lutz B. Expression of the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in distinct neuronal subpopulations in the adult mouse forebrain. Eur J Neurosci 11: 4213–4225, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardinal P, Andre C, Quarta C, Bellocchio L, Clark S, Elie M, Leste-Lasserre T, Maitre M, Gonzales D, Cannich A, Pagotto U, Marsicano G, Cota D. CB1 cannabinoid receptor in SF1-expressing neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus determines metabolic responses to diet and leptin. Mol Metab 3: 705–716, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8: 2281–2308, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H, Wang H, Jaenisch R. Generating genetically modified mice using CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Nat Protoc 9: 1956–1968, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Vries WN, Binns LT, Fancher KS, Dean J, Moore R, Kemler R, Knowles BB. Expression of Cre recombinase in mouse oocytes: a means to study maternal effect genes. Genesis 26: 110–112, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhillon H, Zigman JM, Ye C, Lee CE, McGovern RA, Tang V, Kenny CD, Christiansen LM, White RD, Edelstein EA, Coppari R, Balthasar N, Cowley MA, Chua S, Jr, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Leptin directly activates SF1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body-weight homeostasis. Neuron 49: 191–203, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vianna CR, Donato J, Jr, Rossi J, Scott M, Economides K, Gautron L, Pierpont S, Elias CF, Elmquist JK. Cannabinoid receptor 1 in the vagus nerve is dispensable for body weight homeostasis but required for normal gastrointestinal motility. J Neurosci 32: 10331–10337, 2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4507-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland WL, Bikman BT, Wang LP, Yuguang G, Sargent KM, Bulchand S, Knotts TA, Shui G, Clegg DJ, Wenk MR, Pagliassotti MJ, Scherer PE, Summers SA. Lipid-induced insulin resistance mediated by the proinflammatory receptor TLR4 requires saturated fatty acid-induced ceramide biosynthesis in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 1858–1870, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI43378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan T, Morgan DA, Rahmouni K, Sonoda J, Fu X, Burgess SC, Holland WL, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. FGF19, FGF21, and an FGFR1/beta-klotho-activating antibody act on the nervous system to regulate body weight and glycemia. Cell Metab 26: 709–718, 2017. e703 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caron A, Dungan Lemko HM, Castorena CM, Fujikawa T, Lee S, Lord CC, Ahmed N, Lee CE, Holland WL, Liu C, Elmquist JK. POMC neurons expressing leptin receptors coordinate metabolic responses to fasting via suppression of leptin levels. Elife 7: e33710, 2018. doi: 10.7554/eLife.33710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker KL, Rice DA, Lala DS, Ikeda Y, Luo X, Wong M, Bakke M, Zhao L, Frigeri C, Hanley NA, Stallings N, Schimmer BP. Steroidogenic factor 1: an essential mediator of endocrine development. Recent Prog Horm Res 57: 19–36, 2002. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan O, Sherwin R. Influence of VMH fuel sensing on hypoglycemic responses. Trends Endocrinol Metab 24: 616–624, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coutinho EA, Okamoto S, Ishikawa AW, Yokota S, Wada N, Hirabayashi T, Saito K, Sato T, Takagi K, Wang CC, Kobayashi K, Ogawa Y, Shioda S, Yoshimura Y, Minokoshi Y. Activation of SF1 neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus by DREADD technology increases insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. Diabetes 66: 2372–2386, 2017. doi: 10.2337/db16-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meek TH, Nelson JT, Matsen ME, Dorfman MD, Guyenet SJ, Damian V, Allison MB, Scarlett JM, Nguyen HT, Thaler JP, Olson DP, Myers MG, Jr, Schwartz MW, Morton GJ. Functional identification of a neurocircuit regulating blood glucose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113: E2073–E2082, 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521160113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang R, Dhillon H, Yin H, Yoshimura A, Lowell BB, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS. Selective inactivation of Socs3 in SF1 neurons improves glucose homeostasis without affecting body weight. Endocrinology 149: 5654–5661, 2008. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bingham NC, Verma-Kurvari S, Parada LF, Parker KL. Development of a steroidogenic factor 1/Cre transgenic mouse line. Genesis 44: 419–424, 2006. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheung CC, Krause WC, Edwards RH, Yang CF, Shah NM, Hnasko TS, Ingraham HA. Sex-dependent changes in metabolism and behavior, as well as reduced anxiety after eliminating ventromedial hypothalamus excitatory output. Mol Metab 4: 857–866, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Correa SM, Newstrom DW, Warne JP, Flandin P, Cheung CC, Lin-Moore AT, Pierce AA, Xu AW, Rubenstein JL, Ingraham HA. An estrogen-responsive module in the ventromedial hypothalamus selectively drives sex-specific activity in females. Cell Rep 10: 62–74, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujikawa T, Castorena CM, Pearson M, Kusminski CM, Ahmed N, Battiprolu PK, Kim KW, Lee S, Hill JA, Scherer PE, Holland WL, Elmquist JK. SF-1 expression in the hypothalamus is required for beneficial metabolic effects of exercise. Elife 5: e18206, 2016. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim KW, Donato J, Jr, Berglund ED, Choi Y-H, Kohno D, Elias CF, DePinho RA, Elmquist JK. FoxO1 regulates energy balance and glucose homeostasis in neurons in the ventral medial nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Clin Invest 122: 2578–2589, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI62848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim KW, Jo YH, Zhao L, Stallings NR, Chua SC, Jr, Parker KL. Steroidogenic factor 1 regulates expression of the cannabinoid receptor 1 in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Mol Endocrinol 22: 1950–1961, 2008. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim KW, Zhao L, Donato J, Jr, Kohno D, Xu Y, Elias CF, Lee C, Parker KL, Elmquist JK. Steroidogenic factor 1 directs programs regulating diet-induced thermogenesis and leptin action in the ventral medial hypothalamic nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 10673–10678, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102364108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klockener T, Hess S, Belgardt BF, Paeger L, Verhagen LA, Husch A, Sohn JW, Hampel B, Dhillon H, Zigman JM, Lowell BB, Williams KW, Elmquist JK, Horvath TL, Kloppenburg P, Bruning JC. High-fat feeding promotes obesity via insulin receptor/PI3K-dependent inhibition of SF-1 VMH neurons. Nat Neurosci 14: 911–918, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nn.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majdic G, Young M, Gomez-Sanchez E, Anderson P, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins RL, McGarry JD, Parker KL. Knockout mice lacking steroidogenic factor 1 are a novel genetic model of hypothalamic obesity. Endocrinology 143: 607–614, 2002. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tong Q, Ye C, McCrimmon RJ, Dhillon H, Choi B, Kramer MD, Yu J, Yang Z, Christiansen LM, Lee CE, Choi CS, Zigman JM, Shulman GI, Sherwin RS, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Synaptic glutamate release by ventromedial hypothalamic neurons is part of the neurocircuitry that prevents hypoglycemia. Cell Metab 5: 383–393, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y, Hill JW, Fukuda M, Gautron L, Sohn JW, Kim KW, Lee CE, Choi MJ, Lauzon DA, Dhillon H, Lowell BB, Zigman JM, Zhao JJ, Elmquist JK. PI3K signaling in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus is required for normal energy homeostasis. Cell Metab 12: 88–95, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim KW, Donato J, Jr, Berglund ED, Choi YH, Kohno D, Elias CF, Depinho RA, Elmquist JK. FOXO1 in the ventromedial hypothalamus regulates energy balance. J Clin Invest 122: 2578–2589, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI62848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]