Abstract

Removal of polyphenols from crude olive mill wastewaters (COMWW) is vital to the development of olive industries. In addition, the exploitation of the residue of the olive oil industry such as crude olive stone (COS) constitutes a valorization of this substance and makes a contribution to the fight against environmental pollution. For this purpose, this study concerns the utilization of COS as an adsorbent of polyphenols from COMWW. The characterization of COS was realized by FTIR, XRD, SEM, PZN, BET and TGA-DTA. The adsorption kinetics and isotherms of polyphenols was analyzed by pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), intraparticle diffusion models (MW) and nonlinear models of isotherms Langmuir (LM) and Freundlich (FM) respectively. This study goal at understanding the adsorption mechanism of polyphenols on COS by FTIR and XRD study. The results of adsorption kinetics demonstred that the adsorption capacity of polyphenols ‘PP’ onto COS is decreased from 381 mg g−1 to 235 mg g−1, with the increasing of the temperature, from 25 °C to 45 °C, indicating an exothermic process, which is confirmed by the negative values of enthalpy ΔH°. Moreover, the negative values of free energy ΔG° and entropy ΔS° indicate the spontaneous and ordered adsorption phenomenon. Kinetic and isotherms studies showed that polyphenols adsorption onto crude olive stone followed PSO kinetic, the FM and LM models were the best fitted. Consequently, this study indicates that crude olive stone could be used as a cheap adsorbent for removing of polyphenols from crude COMWW.

Keywords: Polyphenols, Crude olive mill wastewater, Crude olive stone, Kinetic, Isotherm, Mechanism

Polyphenols, crude olive mill wastewater, crude olive stone, kinetic, isotherm, mechanism.

1. Introduction

The region of Fez-Meknes is famous for olive oil production in Morocco. This production generates considerable volumes of liquid residue named ''crude olive mill wastewater (COMWW)'' and solid residue as ''crude olive stone''. COMWW is dark effluent rich in matter organic, tannins, lipids, and polyphenols in a high concentration [1] but the problem is that most industries store the COMWW into ponds and small industries reject the COMWW directly in the soil without any treatment, causing a negative ecological effect and a harmful to certain plants and microorganisms [2, 3].

Recently many technologies are proposed for the treatment of COMWW such as membrane separation, Fenton's reaction [4], photocatalysis [5], liquid-liquid or solid-liquid extraction [6]. These technologies are highly expensive, subsequently, a simple, inexpensive, efficient and sustainable method is needed for reducing COMWW pollution. Adsorption is one of the most able methods used to eliminate pollutants from aqueous solutions [7]. In addition, the utilization of natural adsorbent such as the agriculture byproducts presents many advantages: valorization of this material, reduction of pollution and remain sustainable chemistry and green.

Crude olive stone (COS) is a solid residue of the olive-producing industry. It is regarded a source of pollution not only in Morocco but also in Mediterranean countries for centuries. Around 90% of the olive pulp comprises of woody material, which is rich in cellulose [8]. The use of COS like adsorbent not only creates a helpful material for depollution of the environment contaminated from phenolic derivatives, but it also helps to decrease and value this solid waste. Most pollutants can be removed by the utilization of crude olive stone, for example the adsorption of iron on COS showed the maximum removal of iron was about 70% [9].

The present study intends to test the performance of COS as an adsorbent to reduce the pollution of COMWW to discharge standards. The COS was analyzed by XRD, FTIR, BET, TGA-DTA, zero charge point, and SEM. Following, foresee the experimental kinetics and isotherms data for the adsorption of polyphenols (PP) onto COS, The nonlinear and linear forms of various isotherm and kinetics models were utilized and compared with one another to obtain their corresponding parameters. The current study also concentrate on the characterization after adsorption by X-ray and FTIR analyzes.

2. Experimental

2.1. Material

The crude olive stone was obtained by Olea-Food Company in the Fez-Meknes region (Morocco). This material was cleaned with hexane, dried, and sieved with size <63μm. The natural material was called COS by reference to a crude olive stone.

The crude olive mill wastewater (COMWW) was supplied by system 2 phase in the same region. Before use, the liquid was bubbled with nitrogen in order to avoid the degradation of polyphenols, filtered by centrifugation, and diluted at 80% to reduce suspended matter. The characterization of COMWW was already done in the precedent study [10].

2.2. Characterization of COS

The characterization of COS was realized before and after adsorption of PP from COMWW by:

-

-

X ray diffraction (XRD) spectra was obtained by Philips PW 1800 apparatus equipped with a diffracted beam monochromator (Kα copper line, 40 kV, 20 mA and λ = 1.5418 Ǻ). The 2θ angle was scanned in an interval of 2θ (5°–70°) with an angular increment of 0.04°.

-

-

FTIR spectra of COS were realized utilizing Shimadzu IRAffinity-1S in absorption mode from 400 to 4000 cm−1 with the resolution of 4 cm−1.

-

-

COS surface morphology was seen by the FEI Quanta 200 device.

-

-

The determination of specific surface area was carried by apparatus ASAP 2010 with Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method.

-

-

Thermal degradation of COS was performed in a TA60 SHIMADZU simultaneous TGA-DTA thermal analyzer at a linear heating rate of 10 °C min−1 and in the range of temperature from 25 °C to 600 °C.

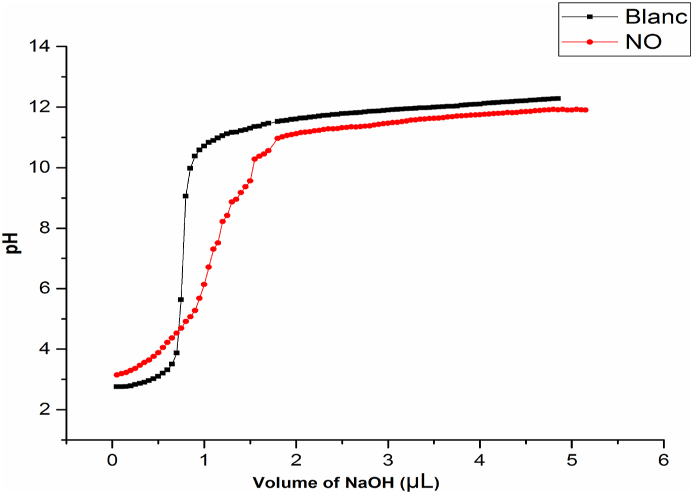

2.3. pH of point zero charge (PZN)

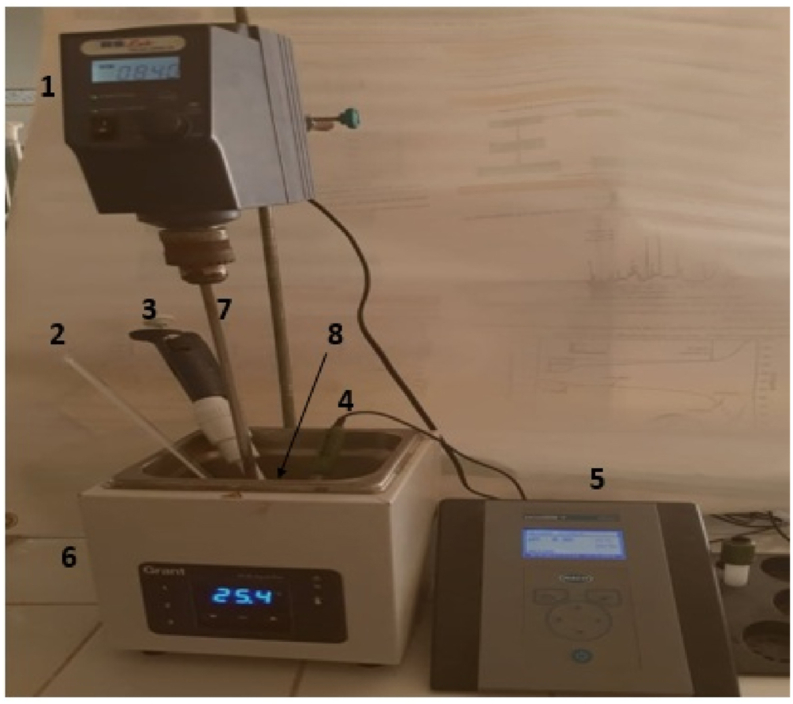

The point of zero charge (pzc) is determined by potentiometric titrations. These latter titrations were carried out at 25 ± 1 °C using the experimental device presented in Figure 1. The titration cell was filled with 100 ± 1 mL of a NaCl electrolyte solution (10−3 mol L−1) more 0.5 ± 0.01 mL of HCl (0.5 mol L−1) and 0.018 g of solid. Using a micropipette, the mixture was titrated (100 mL NaCl + solid +0.5 mL HCl) with a volume of 50 ± 0.005 μL of NaOH titrant (0.2 mol L−1), noting each times the pH value until the titration curve reaches pH around 12. The PZC was determined by plotting the pH as a function of NaOH volume. The same experimental protocol was followed for the titration of the blank (without solid).

Figure 1.

Experimental device for potentiometric titrations. 1: Agitation motor; 2: Thermometer; 3: Micropipette; 4: Combined glass ball electrode; 5: pH meter; 6: Thermostat bath; 7: Propeller agitator; 8: Solution to titrate.

2.4. Adsorption experiments

The adsorption kinetics study of polyphenols (PP) onto COS was made by mixing 50 mg of adsorbent with 50 mL of crude olive mill wastewater solution with a concentration of polyphenols C0 = 0.3 g L−1 into 50 mL black flasks. The mixture was agitated at regular times tads (30 min, 1, 1.5, 2, and 3 h) at temperature (25, 35 and 45 °C) utilizing a thermostatic water bath. In the same experimental conditions, the adsorption isotherms were carried out by increasing initial concentrations (C0) of PP from 0 to 0.58 g L-1. After each adsorption test, the solid was separated of the liquid phase by centrifugation for 30 min. The concentration of polyphenols for each supernatant was determined by Folin-ciocalteu technique [11]. At equilibrium, the residual concentration of PP Ce was determined from the equation of calibration curve (equation 1) from the UV/Visible spectrometer (Shimadzu, UV-1240) at λ = 760 nm. The following Eq. (2) was used to determine the amount adsorbed:

| A = 4. 8153 Ce, R2 = 0. 99 | (1) |

| (2) |

where, R2 is the coefficient of determination, A is the absorbance, Ce and C0 are the residual and initial concentration of PP respectively, which are expressed by mg L−1; m (g) is the mass of COS; V (mL) is the volume of COMWW solution.

2.5. Kinetic, isotherm models and thermodynamic parameters

In order to determine the adsorption mechanism of PP onto COS, the experimental data were fitted using linear kinetics models of pseudo-first order (PFO), pseudo-second order (PSO) and intraparticule diffusion using equation of Weber and Morris (WM) [12, 13, 14, 15]. The non-linear isotherm models were analyzed by Langmuir (LM) and Freundlich models (FM) [16, 17]. The thermodynamic parameters as enthalpy (ΔH0), free energy (ΔG0) and entropy (ΔS0) [18] were determined by the corresponding relations represented in Table 1.where: qm and qe are the maximum amount and the equilibrium amount of polyphenols onto COS respectively, expressed in mg g−1. Ce (mg L−1) is the equilibrium polyphenols concentration of the solution. K1 (min−1) and K2 (g mg−1 min−1) are the speed constant of PFO and PSO respectively. C and Kd are the thickness of the boundary layer and the intra-particle diffusion rate constant respectively, KF (L mg−1) and n are the Freundlich constant. KL is Langmuir constant (L mg−1).

Table 1.

The parameters of kinetic, isotherm, and thermodynamic models.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Physicochemical characterization of COS

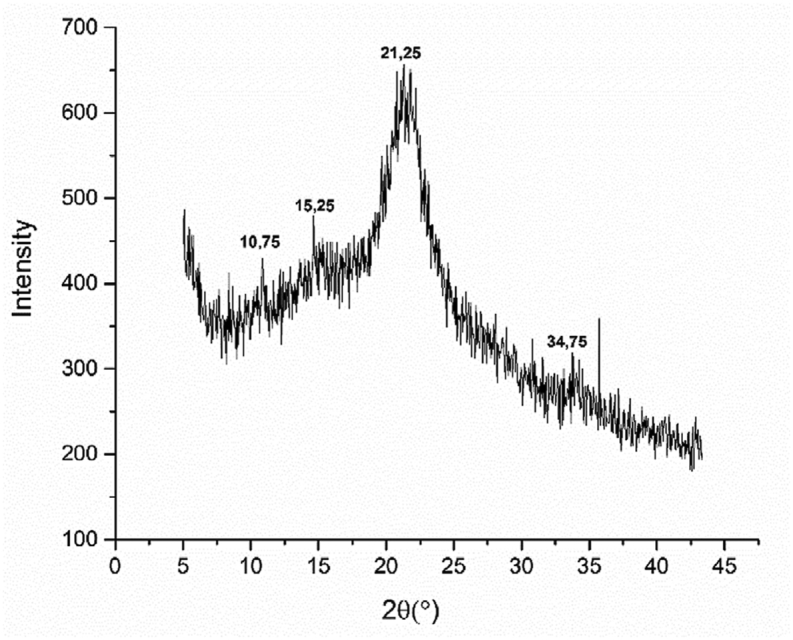

3.1.1. X-ray of COS

The X-ray of COS powder presents a crystalline structure (Figure 2), in agreement with the results of Zhang and Lynd [19], which have found that the crude olive stone contained the cellulose. This last has a crystalline structure due to hydrogen bonding interactions or van der Waals forces between adjacent molecules [20]. Similar result found the presence of peak at 2θ = 11.45°, due to the traces of hemicellulose or lignin [21].

Figure 2.

COS X-ray diffraction patterns.

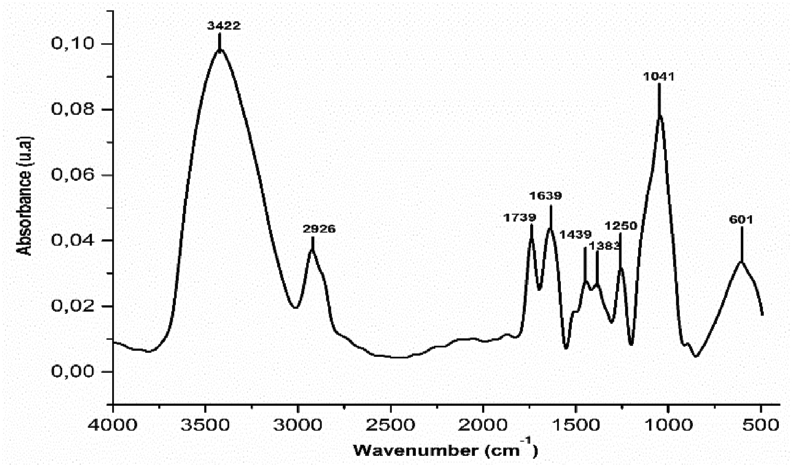

3.1.2. FTIR analysis

As indicate in Figure 3, the large band at 3422 cm−1 correspond to O–H of carboxyl, phenols and alcohols groups of cellulose and lignin in agreement with X-ray observations and also with the previous study's [22, 23]. Besides, the band at 2926 cm−1 is attributed to C–O of aliphatic alcohols, and a peak at 1739 cm−1 indicates the presence of lactones, aldehydes or ketones in cellulose and lignin. Both bands at 1439 and 1639 cm−1 present the elongation vibration of the C=C olefinic structure. Also, the bands between 1041 and 1383 cm−1 assigned to links C–O indicate the presence of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose groups [22, 24, 25, 26]. Finally the band at 601 cm−1 is intended of C–H aromatic ring [22, 25]. In the literature, the bands of OH, C–O and carboxylic acid groups were detected at 3301.54 cm−1, 1078.01cm−1 and 1725.98 cm−1 respectively [27, 28].

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of COS.

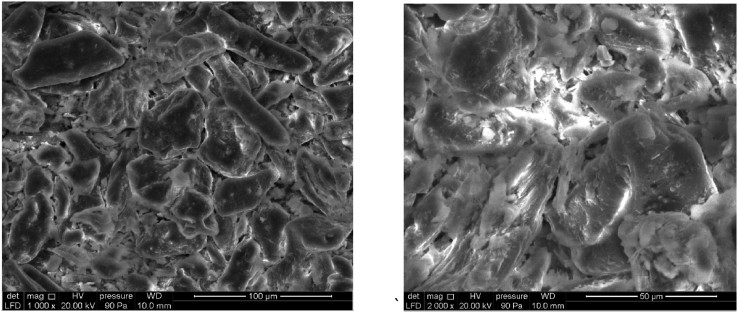

3.1.3. SEM and BET analysis

Figure 4 shows the various porosity states of the surface of COS which has a macro porous structure. The area of this latter is an irregular porous structure with average well-developed deep cavities and pores of different size and shape, the area of COS is 0.89 m2 g−1. The surface area of COS is very important compared to this obtained in the literature [29, 30], whose found values are of the order of 0.60 m2 g−1 and 0.163 m2 g−1 respectively.

Figure 4.

SEM image of COS.

3.1.4. PZN of COS

Figure 5 shows that the pHPZN = 4.60. This indicates that for the pH of the solution lower than 4.60, the surface of COS is positive and when the pH of the solution is superior to 4.60, the surface is negative. These outcomes are in concurrence with studies of A. Aziz et al. and T. Bohli et al., where they found that the pHPZN equal to 2.7 and 3 respectively [31, 32].

Figure 5.

PZN of COS.

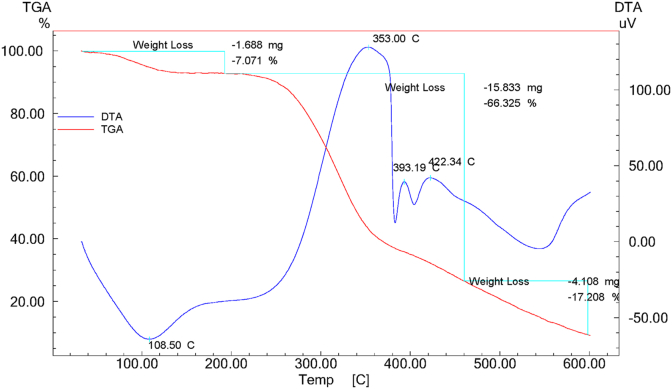

3.1.5. Thermal analysis TGA-DTA

The TGA-DTA thermograms of COS in Figure 6 shows:

-

-

An endothermic peak located at 108.50 °C, corresponding to the removal of adsorbed water molecules with a loss mass of stone olive is 7.07%

-

-

Three exothermic peaks situated at 353.4 °C, 393 °C and 422.3 °C whose total mass loss is 66.325 %. The first peak was attributed to the degradation of cellulose and the two others were due to the degradation of lignin and hemicellulose.

Figure 6.

Thermogravimetric analysis of COS.

These outcomes are in concurrence with crafted by A. Aziz et al. These authors found two weight losses, one between 200–335 °C and the other between 335 and 352 °C, which correspond to the thermal decomposition of hemicellulose with lignin and cellulose degradation respectively. The weight loss of 3.5 % between 20 and 200 °C, was attributed to departure of water [28].

3.2. Adsorption kinetics

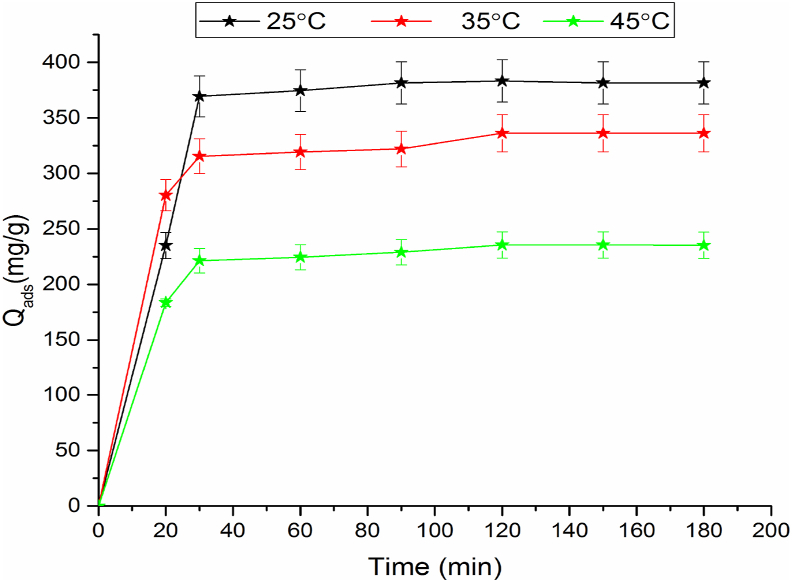

Figure 7 portrays the experimental points of adsorption kinetics of PP onto COS at various temperatures. The amount adsorbed of polyphenols increases rapidly at t > 20 min until achieved equilibrium at 120 min, thereafter it becomes constant.

Figure 7.

Kinetic of PP adsorption at different temperatures onto COS.

The adsorption is very fast during a contact time which does not exceed 3h for all temperatures. The adsorption quantities for COS at T = 25, 35, and 45 °C are 381 mg g−1, 336 mg g−1 and 235 mg g−1 respectively. It is noted that the increase in temperature decreases the adsorbed quantity, which can be explained by an exothermic process. We remark, that the treatment of industrial waste of olive oils requires a low temperature, and consequently no energy consumption.

In addition, the comparison of the adsorbed amounts of PP at equilibrium with that realized in our previous work for the adsorption of PP onto Ghassoul (Gh-B) [33], show that as an example, at equilibrium for T = 25 °C, qads = 381 mg g−1 for COS and qads = 161 mg g−1 for Gh-B. This behavior can be linked to the presence of an irregular structure of COS, that favors the retention of PP on different parts of biosorbent, also in the cavities of COS [29]. Contrarily, the pH of the solution is superior to pHpzn of COS favors the adsorption of polyphenols from COMWW contrariwise of Ghassoul, the pH of solution is lower than pHpzn of Ghassoul. The obtained qads value in this study is near of these obtained by A. Mounia et al. who found the adsorbed quantity equal to 487.3 mg g−1 [34] in the removal of phenolic compounds from olive mill wastewater.

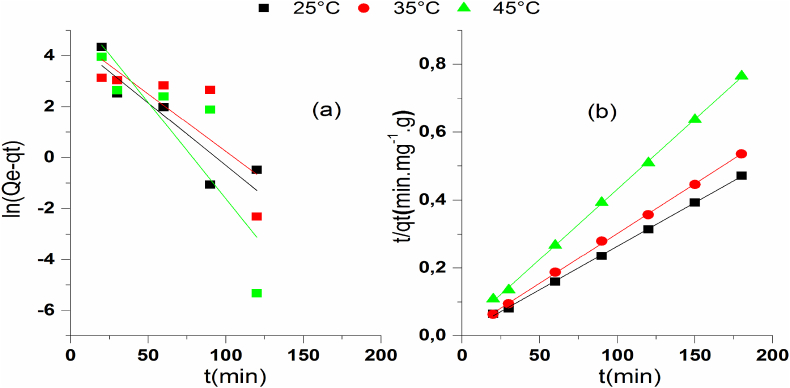

In order to explain the kinetics and the mechanism of PP adsorption onto COS (Figure 8), the experimental data were confronted to PFO and PSO kinetic models given in Table 1 whereas, the equations corresponding to PFO (Figure 8a) and PSO (Figure 8b) are represented in Figure 8. To recognize the most suitable model, the experimental data were analyzed comparing the R2 and the adsorption capacity, also, the kinetic parameters of PFO and PSO. As shown in Figure 8, a perfect agreement between the theoretical curves and the experimental points were obtained for the PSO model. According to these parameters (Table 2), we found that the model of pseudo second-order describes well the experimental points for the three adsorption temperatures. These outcomes are in concurrence with those found in the literature [33, 35, 36].

Figure 8.

PFO (a) and PSO (b) models for the adsorption kinetics of PP onto COS.

Table 2.

Parameters of PFO and PSO models.

| T (°C) | Pseudo-first order model |

Pseudo-second order model |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qads(exp) (mg g−1) | K1 (min−1) | qads(theorique) (mg g−1) | R2 | qads(theorique) (mg g−1) | K2 (g mg−1 min−1) | R2 | |

| 25 | 381.54 | 0.03 | 40.44 | 0.73 | 390.62 | 8.33 10−4 | 0.99 |

| 35 | 336.20 | 0.04 | 94.63 | 0.77 | 341.29 | 9.68 10−4 | 0.99 |

| 45 | 235.21 | 0.05 | 85.62 | 0.51 | 242.13 | 8.90 10−4 | 0.99 |

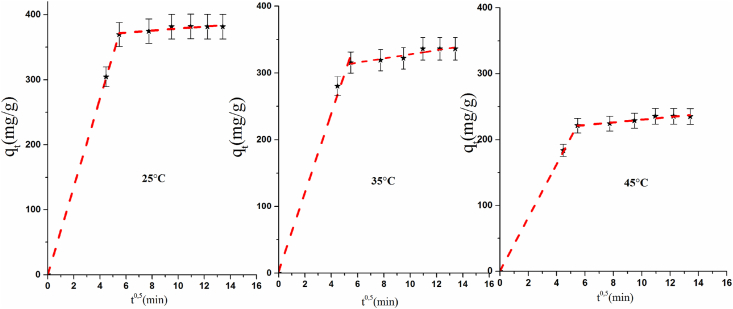

The intra-particle model show two diverse straight lines in Figure 9, which may show two-venture control of the adsorption of PP onto COS. The first step is fast where the adsorption of PP molecules was carried out onto the surface of COS. Nevertheless, the second step demonstrates that the rate of intra-particle diffusion of PP is fast, due to the increase of the number of active sites for PP adsorption on COS. Thus, the values of C are different to 0 (Table 3), which demonstrates that the intraparticle diffusion is not the only step that controls the adsorption kinetics of PP onto COS. This outcome is in concurrence with those acquired by Valderrama et al. and Lavinia et al. [37, 38].

Figure 9.

Intra-particle diffusion model for PP adsorption onto COS.

Table 3.

Parameters of the intra-particle diffusion.

| T (°C) | Etape 1 |

Etape 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Kd (g mg−1 min−1/2) | R2 | C | Kd (g mg−1 min−1/2) | R2 | |

| 25 | 0.24 | 67.67 | 0.99 | 362.77 | 1.58 | 0.74 |

| 35 | 6.02 | 61.38 | 0.94 | 297.07 | 3.08 | 0.84 |

| 45 | 0.31 | 40.61 | 0.99 | 210.19 | 2.02 | 0.88 |

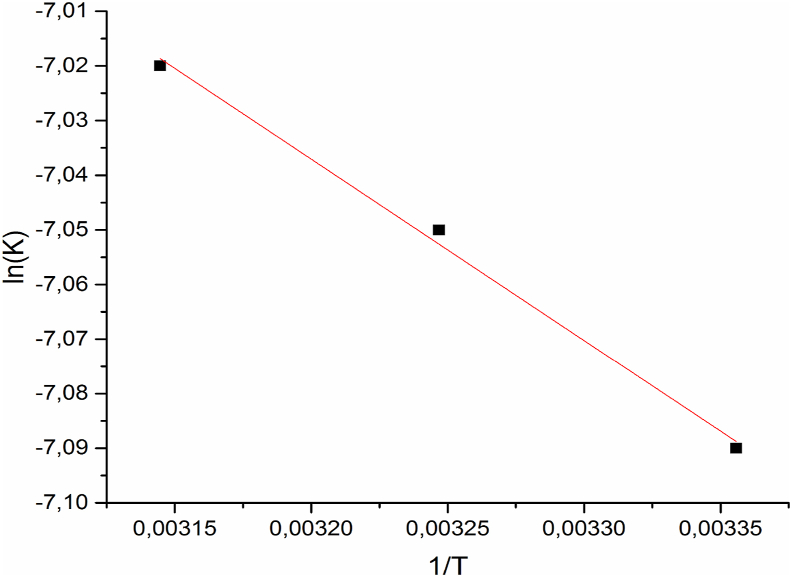

3.2 1. Activation energy

Figure 10 shows, the tracing of Ln (k2) versus 1/T for the determination of activation energy Ea from the slope of the equation line Arrhenius. The activation energy which was 2.75 kJ mol-1 and the adsorption energy was 2.21 kJ mol−1. These values are far less than 40 kJ mol−1, which suggests that the polyphenols are physically adsorbed onto COS. This result is in agreement with the bibliography study [39, 40].

Figure 10.

Arrhenius slope for adsorption of polyphenols onto COS.

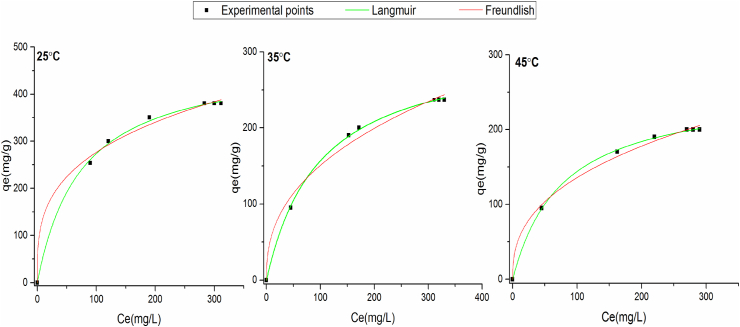

3.3. Adsorption isotherms

The experiments of adsorption isotherms of PP on the solid were carried out in the concentration range 0–0.58 g L−1 Figure 11 shows the experimental points of adsorption isotherms data obtained for Langmuir (LM) and Freundlich models (FM) at various temperatures (25–45 °C), using origin 2015. This software allows determining exactly the parameters of the isotherm models. These parameters are represent in Table 4. The comparison of the values of R2 predicted by the two models, show the values of R2 are close to 1 and the values of n are higher than 1 in the FM, for different temperatures. This uncovers that the adsorption of PP is done according this model. Also, for the Langmuir model, the theoretical adsorption amount of polyphenols is close to the experimental value for various temperatures. Therefore, the both LM and FM are well adapted for this study, with a possibility of mono and multilayer polyphenols formation on the adsorbent surface. This observation is not uncommon because the comparable results have already been reported [41, 42, 43]. This phenomenon can be better explained by the chemical composition of the surface of COS used in this study. The presence of active functional groups of different strength and irregular porous structure of the material may cause differences in the energy level of the active sites that are to say, in a higher energy level, the active sites form a blanket of multi-layered polyphenols using a strong support and with a strong chemical bond. On the other hand, active sites with lower energy levels will induce monolayer coverage due to electrostatic forces [41].

Figure 11.

Adsorption isotherm for polyphenols onto COS.

Table 4.

Parameters of adsorption isotherms.

| T (°C) | Langmuir |

Freundlich |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qmax (mg g−1) | KL (L mg−1) | RL | R2 | n | KF (L mg−1) | R2 | |

| 25 | 477.37 | 0.013 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 3.34 | 69.62 | 0.99 |

| 35 | 310.83 | 0.010 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 2.48 | 23.52 | 0.98 |

| 45t | 254.51 | 0.013 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 2.57 | 22.72 | 0.99 |

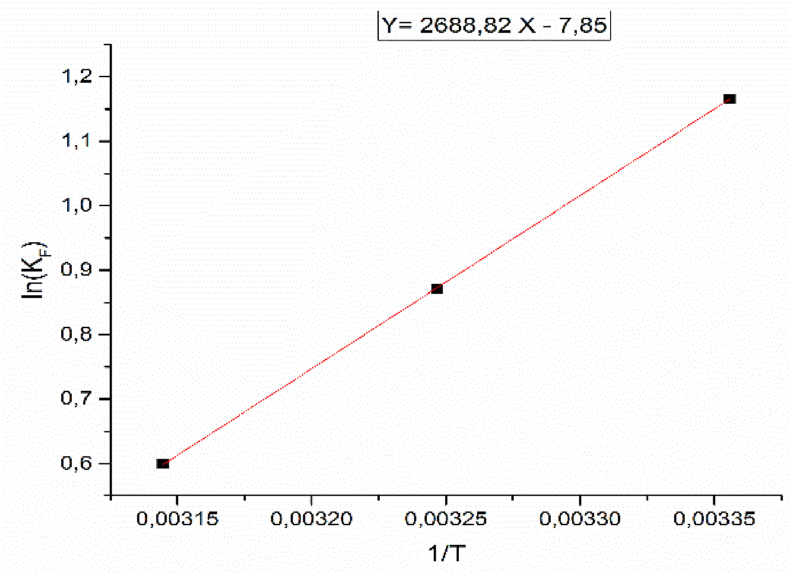

3.3.1. Thermodynamic study

Figure 12 shows the tracing of lnKF according to 1/T and allows to deduce the values of ΔH° and ΔS° which given in Table 5. The ΔH° = -22.35 kJ mol−1 is a negative worth, demonstrating the adsorption process is exothermic in concurrence with the possibility of physical adsorption. The negative value of ΔG° for all temperatures indicates that the adsorption is thermodynamically favorable and spontaneous. A negative value of ΔS° translate the adsorption of PP is ordered or else irregular at the solid-solution interface. These outcomes are identical to W. Yassine et al. [40], who have found that ΔS° = -72.91 J K−1 mol−1 and ΔH° = -105.54 kJ mol−1.

Figure 12.

LnK as a function of 1/T corresponding to the adsorption of PP onto COS.

Table 5.

Thermodynamic parameters of adsorption of polyphenols onto COS.

| Température (K) | ΔG0 (kJ mol−1) | ΔS0 (J K−1mol−1) | ΔH0 (kJ mol−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | −2.80 | −65.26 | −22.35 | 0.99 |

| 308 | −2.23 | |||

| 318 | −1.58 |

3.4. Adsorption mechanism of PP

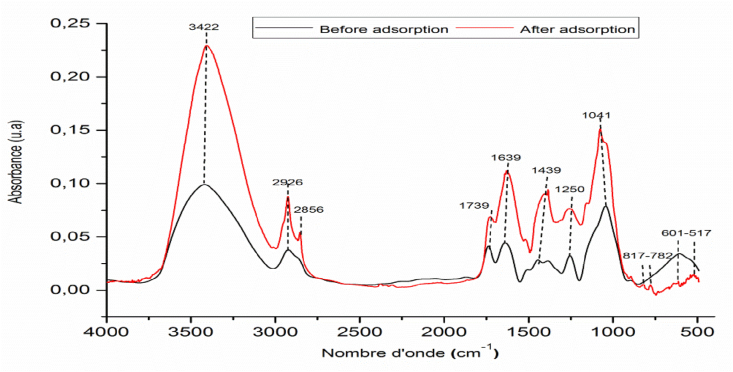

3.4.1. Study by FTIR

The analysis FTIR of the solid before and after contact with PP from OMW has been carried out (Figure 13). Examination of the FTIR spectra of COS during the adsorption of PP from OMWW (Figure 13) shows no vanishing of groups initially detected for COS only but a new band situated at 2856 cm−1 and 517 cm−1 corresponding to C–O of polyphenols and C–H out the plane of aromatic cycles respectively appear. This indicates that the PP was adsorbed onto sites of COS by van der Waals interactions (Ea = 2.75 kJ mol−1). The bands observed at 817 and 782 cm−1 can be attributed to the formation of links between the crude olive stone and the polyphenols after adsorption on account of an increase in the interaction between polyphenols and the negative surface of COS because the pH of the solution pH = 5.07 was higher than the point of zero charges of COS (pHpzc = 4.60).

Figure 13.

Infrared analysis of COS before and after adsorption.

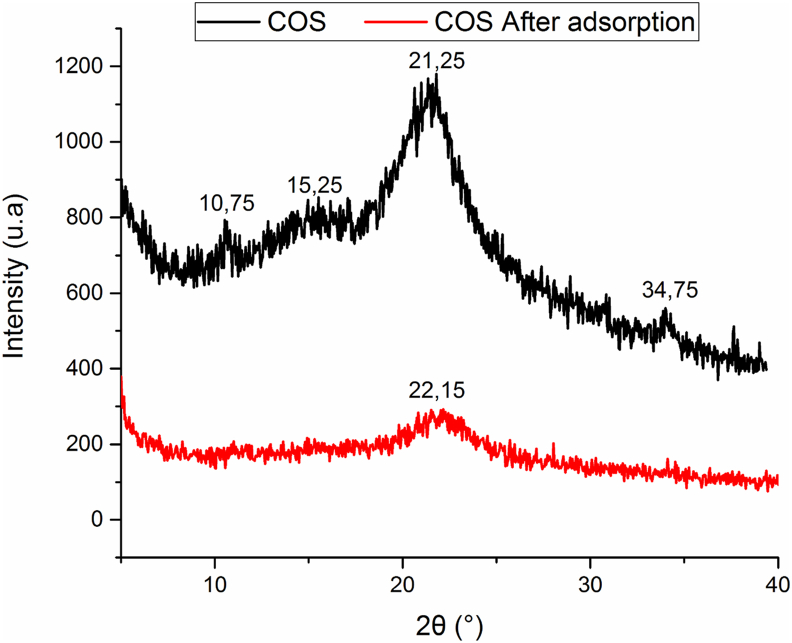

3.4.2. Study by XRD

Figure 14 presents the X-ray diffraction of COS before and after contact with polyphenols. It is noted that the structure of the material is preserved with a diminishing in the intensity of the principal peak characteristic of the cellulose phase and the disappearance of the peaks at 2θ = 10.75°, 15.25° and 34.7° probably due to a partial dissolution of the cellulose and a total dissolution of hemicellulose or lignin phases due to the acidity of the adsorption medium (pH ≈ 5).

Figure 14.

X-ray of COS before and after adsorption.

4. Conclusion

The XRD analysis showed the COS has a crystalline structure with the presence of cellulose phase and traces of hemicellulose or lignin which agrees with FTIR analysis.

The adsorption tests demonstrated that the COS has a high capacity to retain the PP. The adsorption was very fast during a contact time which does not overtake 3h for all temperatures and the amount adsorbed decrease with the increased temperature because of the exothermic interaction which was affirmed by the worth of ΔH° = -22.35 kJ mol-1. However, the adsorption follows the pseudo-second order kinetics and the isotherms of PP at different temperatures onto COS correspond both to the Freundlich, and Langmuir models. The parameters thermodynamic showed the adsorption of PP onto COS is exothermic (ΔH° < 0), ordered (ΔS° < 0), and spontaneous (ΔG° < 0). Therefore, the appearance of the new bands infra-red after adsorption confirmed that PP is adsorbed onto COS.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Safae Allaoui: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Mohammed Naciri Bennani, Hamid Ziyat, Omar Qabaqous, Hamid Ziyat, Omar Qabaqous, Najib Tijani, Najim Ittobane, Gassan Hodaifa: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of the Education and the Scientific Research ‘MENFPESRS’ and the National Center of the Scientific Research ‘CNRST’–Rabat Morocco, within the framework of the PPR2 project. Our thanks also to Olea Food Company in the Fez-Meknes region, for providing the COS sample.

References

- 1.Ron E., Biotechnolo M.L. Chemical and toxic evaluation of a biological treatment for olive-oil mill wastewater using commercial microbial formulations. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004;64:735–739. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1565-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierantozzi P., Zampini C., Torres M., Isla M.I., Verdenelli R.A., Meriles J.M., Maestri D. Physico-chemical and toxicological assessment of liquid wastes from olive processing-related industries. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012;92:216–223. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalogerakis N., Politi M., Foteinis S., Chatzisymeon E., Mantzavinos D. Recovery of antioxidants from olive mill wastewaters: a viable solution that promotes their overall sustainable management. J. Environ. Manag. 2013;128:749–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.06.027. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodaifa G., Ochando-pulido J.M., Rodriguez-vives S., Martinez-ferez A. Optimization of continuous reactor at pilot scale for olive-oil mill wastewater treatment by Fenton-like process. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;220:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sa C., Rodrigo M.A., Ca P. Costs of the electrochemical oxidation of wastewaters : a comparison with ozonation and Fenton oxidation processes. J. Environ. Manag. 2009;90:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stasinakis S., Petala V. Removal of total phenols from olive-mill wastewater using an agricultural by-product, olive pomace. J. Hazard Mater. 2008;160:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basta H., fierro V., El-saied H. 2-Steps KOH activation of rice straw: an efficient method for preparing high-performance activated carbons. Bioresour. Technol. 2009;100:3941–3947. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cellat K. Treatment of olive mill wastewater by catalytic ozonation using activated carbon prepared from olive stone by KOH. Asian J. Chem. 2019;27 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martínez L., Alami S., Hodaifa S.B.D., Faur G., Rodríguez C., Giménez S., Ochand J.A. Adsorption of iron on crude olive stones. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2010;32:467–471. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allaoui S., Bennani M.N., Ziyat H., Tijani N., Ittobane N. Remove of polyphenols on a natural clay ‘Ghassoul’ and effect of the adsorption on the physicochemical parameters of the olive mill wastewaters. RHAZES: Green. App. Chem. 2019;6:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singleton V.L., Orthofer R., Lamuela-Raventós R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152–178. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuh6shan H. Citation review of Lagergren kinetic rate equation on adsorption reactions. Scientometrics. 2004;59:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard G., Maunaye M., Martin G. Removal of heavy metals from waters by means of natural zeolites. Water Res. 1984;18:1501–1507. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho Y.S., McKay G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999;34:451–465. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Of A., Red C., Various O.N., Carbons A. Adsorption of Congo red on various actived carbon: a comparative study. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2002;138:289–305. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langmuir I. Adsorption of gases on plain surfaces of glass mica platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918;40:1361–1403. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freundlich H. 1899. Über die Adsorption in Lösungen; p. 1334. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seki Y., Yurdakoç K. Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic aspects of Promethazine hydrochloride sorption by iron rich smectite. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009;340:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tezcan Ün Ü., Uǧur S., Koparal A.S., Bakir Öǧütveren Ü. Electrocoagulation of olive mill wastewaters. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2006;52:136–141. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., yi-heng percival L., Lynd R., Lee Toward an aggregated understanding of enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose: noncomplexed cellulase systems. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004;88:797–824. doi: 10.1002/bit.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mekdad S. Moulay-Ismail University, Faculty of Sciences Meknes Morocco; April 15, 2018. Elaboration , Caractérisation et Applications de Nanocomposites Cellulose/Hydroxydes Doubles Lamellaires (HDLs) Chemistry Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohli T., Ouederni A., Fiol N., Villaescusa I. Evaluation of an activated carbon from olive stones used as an adsorbent for heavy metal removal from aqueous phases. Comptes Rendus - Chim. 2015;18:88–99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Superieur M.D.E.L.E., Scientifique E.T.D.E.L. 2014. Elimination des colorants cationiques par des charbons actifs synthétisés à partir des résidus de l’agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaya N., Atagur M., Akyuz O., Seki Y., Sarikanat M., Sever K. Fabrication and characterization of olive pomace fi lled PP composites. Composites Part B. 2018;150:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghouma I., Jeguirim M., Dorge S., Limousy L., Ouederni A. Comptes Rendus Chimie Activated carbon prepared by physical activation of olive stones for the removal of NO2 at ambient temperature. C.R.Chim. 2014;18:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaouadi M., Hbaieb S., Guedidi H., Reinert L., Amdouni N., Duclaux L. Preparation and characterization of carbons from b -cyclodextrin dehydration and from olive pomace activation and their application for boron adsorption. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2016;21:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larous S., Meniai A. Adsorption of Diclofenac from aqueous solution using activated carbon prepared from olive stones. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2016;41:10380–10390. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aziz A., Hadj E., Belhalfaoui B., Said M., Charles L., Ménorval D. Colloids and Surfaces B : biointerfaces Efficiency of succinylated-olive stone biosorbent on the removal of cadmium ions from aqueous solutions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2009;73:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hodaifa G., Ben S., Alami D., Ochando-pulido J.M., Víctor-ortega M.D. Iron removal from liquid ef fl uents by olive stones on adsorption column : breakthrough curves. Ecol. Eng. 2014;73:270–275. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calero M., Bl G. New treatment of real electroplating wastewater containing heavy metal ions by adsorption onto olive stone. J. Clean. Prod. 2014;81:120–129. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aziz A., Said M., Hadj E., Charles L., Menorval D., Lindheimer M. Chemically modified olive stone : a low-cost sorbent for heavy metals and basic dyes removal from aqueoussolutions. J. Hazard Mater. 2009;163:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.06.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohli T., Fiol N., Villaescusa I., Ouederni A. “Adsorption on activated carbon from olive Stones : kinetics and equilibrium of phenol removal from aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. Pro. Tech. 2017;4 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allaoui S., Bennani M.N., Ziyat H., Qabaqous O., Tijani N., Ittobane N. Kinetic study of the adsorption of polyphenols from olive mill wastewater onto natural Clay Ghassoul. J. Chem. 2020:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mounia A., Hafidi A., Mandi L., Ouazzani N. Desalination and Water Treatment Removal of phenolic compounds from olive mill wastewater by adsorption onto wheat bran. Desalin Water Treat. 2015;52:2875–2885. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fierro V., Torné-Fernández V., Montané D., Celzard A. Adsorption of phenol onto activated carbons having different textural and surface properties. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008;111:276–284. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A., Kumar S., Kumar S. Adsorption of resorcinol and catechol on granular activated carbon: equilibrium and kinetics. Carbon N. Y. 2003;41:3015–3025. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gómez Caravaca A.M., Carrasco Pancorbo A., Cañabate Díaz B., Segura Carretero A., Fernández Gutiérrez A. Electrophoretic identification and quantitation of compounds in the polyphenolic fraction of extra-virgin olive oil. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:3538–3551. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lupa L., Cocheci L., Pode R., Hulka I. Phenol adsorption using Aliquat 336 functionalized Zn-Al layered double hydroxide. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2017;196:82–95. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senol A., Hasdemir İ.M., Hasdemir B., Kurda İ. Adsorptive removal of biophenols from olive mill wastewaters (OMW) by activated carbon : mass transfer , equilibrium and kinetic studies. Asia Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2016;12:128–146. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yassine W., Zyade S., Akazdam S., Essadki A., Gourich B. A study of olive mill waste water removal by a biosorbent prepared by olive stones, Mediterr. J. Chem. 2019;8:420–434. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Din A.T.M., Hameed B.H., Ahmad A.L. Batch adsorption of phenol onto physiochemical-activated coconut shell. J. Hazard Mater. 2009;161:1522–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozkaya B. Adsorption and desorption of phenol on activated carbon and a comparison of isotherm models. J. Hazard Mater. 2006;129:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmaruzzaman M., Sharma D.K. Adsorption of phenols from wastewater. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;287:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.