Abstract

Objectives

To characterize the clinical course and outcomes of children 12-18 years of age who developed probable myopericarditis after vaccination with the Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine.

Study design

A cross-sectional study of 25 children, aged 12-18 years, diagnosed with probable myopericarditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination as per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for myopericarditis at 8 US centers between May 10, 2021, and June 20, 2021. We retrospectively collected the following data: demographics, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus detection or serologic testing, clinical manifestations, laboratory test results, imaging study results, treatment, and time to resolutions of symptoms.

Results

Most (88%) cases followed the second dose of vaccine, and chest pain (100%) was the most common presenting symptom. Patients came to medical attention a median of 2 days (range, <1-20 days) after receipt of Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. All adolescents had an elevated plasma troponin concentration. Echocardiographic abnormalities were infrequent, and 92% showed normal cardiac function at presentation. However, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, obtained in 16 patients (64%), revealed that 15 (94%) had late gadolinium enhancement consistent with myopericarditis. Most were treated with ibuprofen or an equivalent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for symptomatic relief. One patient was given a corticosteroid orally after the initial administration of ibuprofen or an nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; 2 patients also received intravenous immune globulin. Symptom resolution was observed within 7 days in all patients.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that symptoms owing to myopericarditis after the mRNA COVID-19 vaccination tend to be mild and transient. Approximately two-thirds of patients underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, which revealed evidence of myocardial inflammation despite a lack of echocardiographic abnormalities.

Keywords: mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, myocarditis, pericarditis

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMR, Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; IgG, Immunoglobulin G; mRNA, Messenger RNA; NSAID, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

See related articles, p 5, p 317, and p 321

The US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on December 11, 2020, for the Pfizer-BioNTech messenger RNA (mRNA) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine (BNT162b2, Pfizer-BionTech, Pfizer Inc) in individuals 16 years of age and older.1 On May 10, 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration expanded the Emergency Use Authorization of the same vaccine to children 12-15 years of age.2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) subsequently recommended the COVID-19 vaccine for children 12 years and older via a notification issued on May 12, 2021. As of June 26, 2021, 322 million doses of various COVID-19 vaccines have been administered, of which 4 521 732 children aged 12-15 years (5% of the US population) and 3 213 339 adolescents aged 16 and 17 years (2.5% of the US population) had received at least 1 dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.3 Since April 2021, an increase in myopericarditis has been reported temporally associated with COVID-19 vaccination, particularly among adolescents. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Heart Association have endorsed the CDC recommendations and reiterated the potential benefits of COVID-19 vaccination, which outweigh the apparent small risk of myopericarditis in children 12 years of age and older.4 , 5 We summarize our findings in 25 adolescents 12-18 years of age with vaccine-associated myopericarditis from 8 centers across the US.

Methods

A multi-institutional group of pediatric cardiologists, pediatric intensivists, and pediatric infectious disease physicians from 8 centers across the US pooled their data for this retrospective case series. Children were included in the study if they presented with probable myopericarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination between May 10, 2021, and June 20, 2021, and were aged 12-18 years. Clinical and laboratory data were collected free of personal identifiers except for age, race, and sex—and submitted by collaborating authors via secure email. We collected the data retrospectively according to the institutional review board policies of each of the participating institutions. Detailed cardiac abnormalities of 8 cases are the subject of another publication.6

Patient data included age, sex, race and ethnicity, history, or evidence of prior severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (ie, either rapid COVID-19 test or polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2), and symptoms at presentation (ie, chest pain, fever, shortness of breath, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or any other unusual symptoms). The laboratory data included testing to detect other viral causes of myocarditis, serum concentrations of an inflammatory marker (C-reactive protein) and cardiac biomarker (troponin), electrocardiographic findings, echocardiographic findings, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) findings. Results of serologic testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies as performed at the discretion of, and using tests available to, the reporting sites were collected. Additional data included the duration of hospitalization and details of the therapy administered.

Results

The Table summarizes the characteristics of 25 adolescents, 12-18 years of age, who had probable myopericarditis as per the CDC-defined criteria for diagnosis of myocarditis and pericarditis.7 Twenty-two (88%) were males, and 22 (88%) presented after the second dose of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Three adolescents (approximately 10%) (patients 4, 8, and 20) had probable myopericarditis after the first dose. One of these patients (patient 4) had evidence of probable myopericarditis 20 days after the first dose, with complete clinical resolution. He again presented with chest pain and was diagnosed with probable myopericarditis 1 day after the second dose of the vaccine.

Table.

Characteristics of 25 adolescents with probable myopericarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine administration

| Patients | Age | Sex | Race | mRNA vaccine dose | Days from vaccination to symptoms | Symptoms | CRP (mg/dL) Normal: <0.3 mg/dL |

Tn (ng/mL) Normal ≤ .04 ng/mL |

ECG | ECHO | CMR | Rx | Hospital days and clinical course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 15 | M | C | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath | ↑ (8.9) | ↑ (24.6) | ST ↑ | LV Fx ↓ (LVE F 49%) |

LGE+ | Ibuprofen | 5 (LV function normal on discharge) |

| 2. | 15 | F | C | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain | ↑ (25.4) | ↑ (41.9) | ST ↑ and T wave inversion in lateral leads | NL LV Fx |

LGE+, edema | Ibuprofen | 3 |

| 3. | 15 | M | C | 2nd | Few hours | Fatigue, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, vomiting | ↑ (23.5) | ↑ (12.9) | T wave inversion in lateral leads, PVCs | NL LV Fx |

LGE+, edema | Ibuprofen | 3 |

| 4. | 17 | M | H | 1st | 20 | Chest pain | ND | ↑ (5.6) | Non specific ST changes | NL LV FX | ND | Ibuprofen | Outpatient management only |

| 5. | 17 | M | H | 2nd | 1 | Chest pain | ↑ (1.5) | ↑ (11.3) | ST ↑ NS VT | NL LV Fx |

LGE+ | Ibuprofen, IVIG | 3 |

| 6. | 17 | M | H | 2nd | 4 | Chest pain | ND | ↑ (4.8) | ST ↓ | NL LV Fx |

ND | Ibuprofen | 2 |

| 7. | 16 | M | H | 2nd | 4 | Chest pain | ↑ (1.8) | ↑ (4.5) | ST ↑ PR ↓ | NL LV Fx |

LGE+ | Ibuprofen | 3 |

| 8. | 15 | M | H | 1st | 3 | Chest pain | ↑ (2.8) | ↑ (11.8) | Normal 2 episodes of NS VT |

NL LV Fx |

LGE+ | None | 3 |

| 9. | 16 | M | H | 2nd | 1 | Chest pain | ND | ↑ (2.42) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

ND | Ibuprofen | 2 |

| 10. | 12 | M | C | 2nd | 4 | Chest pain | ND | ↑ (1.7) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx | ND | Ibuprofen | Outpatient management only |

| 11. | 15 | M | H | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain | ND | ↑ (5.1) | Normal | NL LV Fx |

ND | Ibuprofen | 2 |

| 12. | 15 | M | H | 2nd | 3 | Chest pain | ND | ↑ (23.5) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

ND | Ibuprofen | 2 |

| 13. | 17 | M | C | 2nd | 1 | Chest pain | ND | ↑ (5.1) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

ND | Ibuprofen | 1 |

| 14. | 17 | M | H | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain, fever, chills | ↑ (5.56) | ↑ (2.1) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

LGE+, small PE | Ibuprofen | 2 |

| 15. | 14 | M | A | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain, shortness of breath, shoulder and neck pain | ↑ (2.36) | ↑ (1.1) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

LGE+ | Ibuprofen | 4 |

| 16. | 14 | M | O | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain | ↑ (4.25) | ↑ (2.1) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

LGE+ | Ibuprofen | 2 |

| 17. | 12 | M | C | 2nd | 3 | Chest pain, diaphoresis, tingling of fingers | ↑ (.94) | ↑ (1.1) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

LGE+ | Ibuprofen | 2 |

| 18. | 17 | M | H | 2nd | 4 | Chest pain. myalgia headache | ↑ (8.4) | ↑ (3.6) | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

LGE+, edema | Ibuprofen | 3 |

| 19. | 16 | M | C | 2nd | 3 | Chest pain fever headache | ↑ (9.5) | ↑ (5.4) | ST ↑ NSVT | NL LV Fx |

LGE+, Edema | Naproxen, enalapril, spironolactone | 4 |

| 20. | 16 | F | AA | 1st | 5 | Chest pain, syncope | ↑ (0.4) | ↑ (1.2) | LBBB, junctional rhythm, first-degree AV block, T wave inversion | LV Fx ↓ (LVEF 48%) |

LGE+, edema, small PE | Lasix, Ibuprofen | 5 |

| 21. | 13 | F | AA | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain | ↑ (4.4) | ↑ (0.6) | Nonspecific ST changes | NL LV Fx, small PE |

LGE -, small PE | Ibuprofen | 4 |

| 22. | 16 | M | C | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain, fever | ↑ (8.4) | ↑ (18.5) | Normal | NL LV Fx |

LGE+, edema | Enalapril, spironolactone | 1 |

| 23. | 15 | M | H | 2nd | 2 | Chest Pain | ↑ (2.1) | ↑ (13.1) | Normal, SVT 4 beats | NL LV Fx |

ND | Ibuprofen | 5 |

| 24. | 15 | M | C | 2nd | 2 | Chest pain, nausea, vomiting, tactile fever | ↑ (26.2) | ↑ (6.4) | Diffuse nonspecific ST change s | NL LV Fx |

LGE+ | Ketorolac, IVIG, methyl prednisolone, low-dose aspirin | 7 |

| 25. | 16 | M | AA | 2nd | 2 | Fever, chest pain | NL | ↑ | ST ↑ | NL LV Fx |

ND | Ibuprofen | Outpatient management only |

A, Asian; AA, African American; AV, atrioventricular; C, Caucasian; CRP, C-reactive protein; ECG, electrocardiogram; ECHO, echocardiogram; F, female; Fx, function; H, Hispanic; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricle; M, male; ND, not done; NL, normal; NS VT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; O, others; PE, pericardial effusion; PVC, premature ventricular contractions; Rx, treatment; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; Tn, serum troponin concentration; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

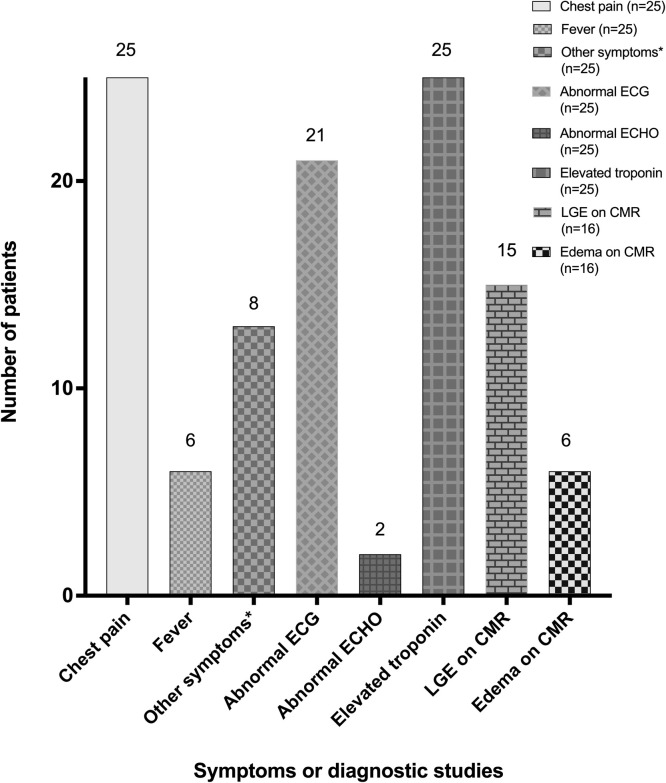

The most common presenting symptom was chest pain. A few patients had additional symptoms, including fever, shortness of breath, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain (Table ). After the second dose of the vaccine, 60% and 72% of patients reported onset of symptoms within 2 and 3 days, respectively (median, 2 days; range, <1-4 days). Time to onset of symptoms after a first dose of vaccine in 3 patients (patients 4, 8, 20) was 20, 3, and 5 days, respectively. All 25 patients had elevated plasma troponin concentration (Figure 2). Serum C-reactive protein concentration was measured in 18 patients (72%) and was elevated in all except 1 (patient 25).

Figure 2.

Common clinical presentation and diagnostic test results of 25 adolescents with probable myopericarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine administration. ∗Other symptoms included shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, chills, fatigue, headache, myalgia, sore throat, neck pain, diaphoresis, and syncope.

Only 1 adolescent (patient 8) in the series had a prior history of symptomatic COVID-19 infection (4 months before presentation), but a COVID antibody test was negative at presentation with myopericarditis. COVID-19 antinucleocapsid antibody testing was performed in 15 patients; only 4 tests (patients 5, 6, 9, and 18) were positive. SARS-CoV-2 anti–spike protein Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody enzyme immunoassay was performed in 8 patients (all presenting after the second dose) and all tests were positive. One patient (patients 4 and 5 [Table]), had myopericarditis after both the doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Antibody testing was not performed after the first episode of myocarditis. He tested positive for COVID-19 antinucleocapsid antibody after the second episode. COVID-19 anti–spike antibody testing was not performed on this patient. COVID-19 reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction was performed on respiratory tract specimens in 88% of patients at presentation and was negative in all except 1 patient (patient 23). Viral respiratory panel was negative in 19 patients tested (76%). One adolescent had positive serum parvovirus B-19 IgM antibody (patient 20).

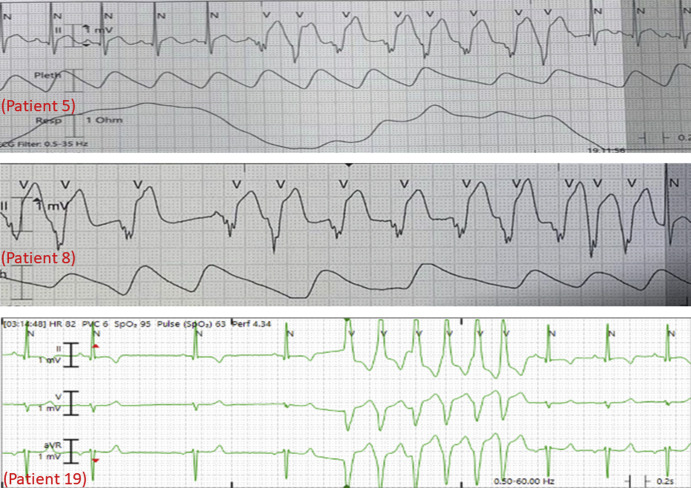

Electrocardiographic abnormalities were common (84%). Abnormal electrocardiographic findings included ST-segment elevation (60%), isolated nonspecific ST changes (24%), ST-segment depression (4%), and PR-segment depression (4%). Three patients (patients 5, 8, and 19) had asymptomatic nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com), 1 had asymptomatic nonsustained supraventricular tachycardia (patient 23); additionally, 1 patient (patient 3) was noted to have frequent premature ventricular contractions on telemetry during hospitalization.

Figure 1.

Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia noted in patients 5, 8, and 19.

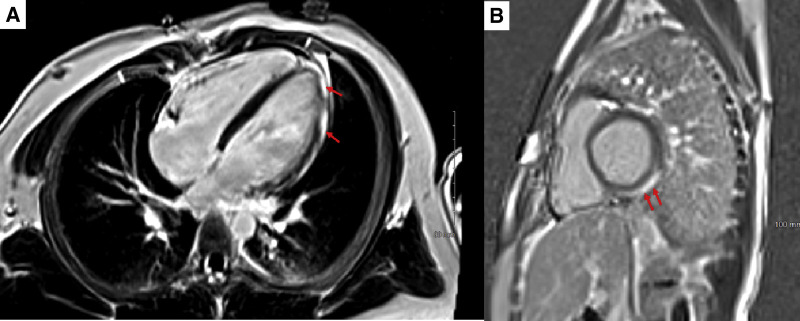

Echocardiography was performed in all patients and showed normal left ventricular systolic function in the majority (23 patients [92%]). Two patients (patients 1 and 20) had mildly diminished ventricular function with abnormal left ventricular ejection fractions ranging from 48% to 49% (Figure 2 ). A few patients were noted to have a trivial or small amount of pericardial fluid; none of the patients had a substantial pericardial effusion. In contrast, CMR, which was performed in 16 of 25 patients (64%), revealed late gadolinium enhancement in 15 (94%) (Figure 3 ). The pattern of enhancement was subepicardial in 5 (33%), subepicardial and midmyocardial in 6 (40%), midmyocardial and subendocardial in 1 (7%), midmyocardial in 2 (14%), and transmural in 1 (7%) patients. Additional findings included myocardial edema on T2 mapping in 6 (37.5%) and a small pericardial effusion in 3 (19%) patients, one of whom did not have late gadolinium enhancement.

Figure 3.

A, Phase-sensitive inversion recovery sequence showing a 4-chamber slice with subepicardial late gadolinium enhancement involving basal, mid, and distal anterolateral left ventricular wall segments. B, Phase-sensitive inversion recovery sequence showing short axis basal slice with subepicardial late gadolinium enhancement involving inferior and inferolateral left ventricular wall segments.

Hospitalized patients had stays of 2-7 days (median, 3 days). All recovered clinically and were discharged home in less than 7 days. Three patients (patients 4, 10, and 25) did not require hospitalization and were followed as outpatients. Most patients were treated with ibuprofen or an equivalent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and responded well; 1 patient was treated with a corticosteroid after initial ibuprofen or NSAID administration owing to an increasing troponin concentration; 2 patients (patients 5 and 24) also received intravenous immune globulin in addition to other therapies, which was based on physician and family preference than specific clinical criteria. All afflicted adolescents made a complete clinical recovery in 1 week and were doing well at the most recent follow-up.

Discussion

Our report represents a large series of adolescents with myopericarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination.7 , 8 The US Food and Drug Administration added a warning about the risk of myocarditis and pericarditis to the fact sheet of both mRNA vaccines on June 25, 2021.9 Our findings suggest that, in many instances, myopericarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination tends to be mild and resolves within a few days. Elevation of plasma troponin concentration and abnormalities on CMR are common in these patients; however, overt abnormalities on echocardiography are unusual and mild if present. Furthermore, given the large number of doses mRNA COVID-19 vaccine administered to adolescents at this writing, this newly recognized complication is very infrequent and the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risk of vaccination for adolescents 12 years of age or older. Careful observation for reporting of myopericarditis after second doses of vaccine is warranted especially in 12- to 15-year-olds as at the time of this writing, less than 6 weeks after the recommendation, very few of the approximately 4.5 million doses administered would have been second doses.

Thus far, 79 children aged 16 or 17 years, and 196 young adults aged 18-24 years have been confirmed by the CDC as having myocarditis/pericarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination after analyzing vaccine adverse event reporting system data; many more cases are under review currently.10 The preliminary estimated risk of myocarditis after administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA vaccine is 1.2 and 10.4 per million after the administration of the first and second dose, respectively, among those 16-39 years of age.11 In a report from the Israeli Ministry of Health, 1 in 3000 to 1 in 6000 men aged 16-24 years who received the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine developed myocarditis or pericarditis.12 Ninety percent of affected individuals in Israel were young men. Although the background rate of myocarditis in this population is high, the rate after vaccination seemed to be 5-25 times higher than the background rate.12 The European Medicines Agency also has reported myocarditis/pericarditis related to mRNA vaccination, but concluded no indication of a causal relation with the vaccine.13 The striking male preponderance in our cohort is consistent with reports in young adults and small series of adolescents.7 , 12

A similar increase in myocarditis and pericarditis has not been reported after administration of non-mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, such as the Janssen Vaccine (Ad.26.COV2.S) (Johnson & Johnson). Continuing reports after the administration of mRNA platform-based vaccines suggest a unique risk, and several mechanisms have been hypothesized. It has been speculated from data reported in the initial trials of mRNA vaccine in adults14 , 15 that mRNA vaccines might generate a very high antibody response in a small subset of young people, thus eliciting a response similar to multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-CoV-2. However, anti-spike IgG antibody titers in a small subset of our patients, were variable (data not shown) and did not correlate with the extent of cardiac injury. Furthermore, Muthukumar et al conducted detailed immunologic investigation in a 52-year-old man who developed myocarditis 3 days after receiving the second dose of Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and reported that his antibody responses to 18 different SARS-CoV-2 antigens did not differ from (and were lower for some antigens) vaccinated controls who did not develop complications.16 Other hypothesized mechanisms include induction of anti-idiotype cross-reactive antibody-mediated cytokine expression in the myocardium, leading to aberrant apoptosis, resulting in inflammation of the myocardium and pericardium.17 Induction of a nonspecific innate inflammatory response by the mRNA vaccine or a molecular mimicry mechanism between viral spike protein and an unknown cardiac protein also has been postulated.18 The mRNA in the vaccine is a potent immunogen and produces bystander or adjuvant effects by cytokine activation of preexisting autoreactive immune cells.19

The complication of mRNA vaccine-related myopericarditis has predominantly been reported in males. Whether hormonal or other differences play a role in expression of this disease has not been evaluated systematically.

The definitive diagnosis of myocarditis is established by histologic criteria, including acute myocyte injury with inflammatory cell infiltration, especially lymphocytes.20 In most patients, myocarditis is transient and self-limited; therefore, endomyocardial biopsy is not justified. An elevated serum troponin concentration may indicate acute cardiac injury, but is neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of myocarditis. Because of variable clinical manifestations of myocarditis, it is helpful to follow the CDC definition of acute myocarditis and acute pericarditis. As demonstrated by our data, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with tissue characterization using T1 and T2 mapping is a useful noninvasive modality for diagnosing mRNA COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis or pericarditis, especially in patients with normal echocardiographic findings.21

Treatment considerations for non–vaccine-associated myocarditis include anti-inflammatory medications and guideline-directed medical therapy if left ventricular function is diminished.22 There are no systematic data on specific treatment of COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis. As shown in our study, ibuprofen or equivalent NSAIDs seem to provide a beneficial response and could be prudent initial management. The role of corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin remains unclear, but these agents could decrease the immune response triggered by the vaccine and have a role in NSAID-unresponsive patients.

There are several limitations to our study. We do not have the data on the total number of children vaccinated during the study period; therefore, the incidence of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine-associated myocarditis and pericarditis cannot be determined. Moreover, although the patients who were symptomatic and sought medical care were evaluated and diagnosed, several COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis episodes could be subclinical or have trivial symptoms that did not lead to seeking medical care. Reported cases could underestimate the true incidence of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis and pericarditis. Because the Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) vaccine is the only mRNA vaccine currently approved in individuals at 12-15 years of age, we have presumed that all patients received this vaccine (without verifying vaccination cards). Not all laboratory tests, including testing for other causes of viral myocarditis, serologic testing for COVID-19, and CMR, were available for each patient owing to variability in practice among individual physicians and centers. The typical occurrence of non–COVID vaccine-associated myocarditis in children and adolescents is approximately 10-20/100 000 annually.23 After the initiation of COVID-19 vaccination and relaxation of restrictions, there has been an increase in overall mobility after a prolonged period of lockdown. Therefore, there might have been an increase in non–mRNA COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis of undetermined viral cause, which could have been misdiagnosed as COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis.

The long-term impact of myopericardial inflammation after COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, especially in those with extensive myocardial involvement on CMR, remains unknown and needs to be systematically evaluated. Further studies are required to elucidate the pathophysiology that underlies this complication to seek mitigation strategies and to delineate optimal therapy.

Data Statement

Data sharing statement available at www.jpeds.com.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Data

Appendix

References

- 1.Oliver S.E., Gargano J.W., Marin M., Wallace M., Curran K.G., Chamberland M., et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' interim recommendation for the use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1922–1924. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace M., Woodworth K.R., Gargano J.W., Scobie H.M., Blain A.E., Moulia D., et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine in Adolescents Aged 12-15 Years — United States, May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:749–752. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7020e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Demographic characterisics of people receiving COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographic

- 4.AAP News. www.aappublications.org/news/2021/06/10/covid-vaccine-myocarditis-rates-061021

- 5.AHA Statement on May 23, 2021. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/covid-19-vaccine-benefits-still-outweigh-risks-despite-possible-rare-heart-complications-

- 6.Tano E., San Martin S., Girgis S., Martinez-Fernandez Y., Sanchez Vegas C. Perimyocarditis in adolescents after Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2021 doi: 10.1093/jpids/piab060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall M., Ferguson I.D., Lewis P., Jaggi P., Gagliardo C., Collins J.S., et al. Symptomatic acute myocarditis in seven adolescents following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination. Pediatrics. 2021;148 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052478. e2021052478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snapiri O., Rosenberg Danziger C., Shirman N., Weissbach A., Lowenthal A., Ayalon I., et al. Transient cardiac injury in adolescents receiving the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021 doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recent update on mRNA Vaccine. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/slides-2021-06.html

- 10.CDC confirms 226 cases of myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination in people 30 and under. American Academy of Pediatrics (aappublications.org). Accessed June 30, 2021. https://aappublications.org/news/2021/06/10/covid-vaccine-myocarditis-rates-061021

- 11.Vaccine and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC), June 10, 2021, Meeting Presentation. https://www.fda.gov/media/150054/download

- 12.Vogel G., Couzin-Frankel J. Israel reports link between rare cases of heart inflammation and COVID-19 vaccination in young men. Science. 2021 doi: 10.1126/science.abj7796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meeting highlights from the pharmacovigilance risk assessment committee (PRAC) 3-6 May 2021. ema.Europa.eu

- 14.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novack R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthukumar A., Narasimhan M., Li Q.Z., Mahimainathan L., Hitto I., Fuda F., et al. In depth evaluation of a case of presumed myocarditis following the second dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Circulation. 2021;144:487–498. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimaud M., Starck J., Levy M., Marais C., Chareyre J., Khraiche D., et al. Acute myocarditis and multisystem inflammatory emerging disease following SARS-CoV-2 infection in critically ill children. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:69. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00690-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segal Y., Shoenfeld Y. Vaccine-induced autoimmunity: the role of molecular mimicry and immune crossreaction. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15:586–594. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Root-Bernstein R., Fairweather D. Unresolved issues in theories of autoimmune disease using myocarditis as a framework. J Theor Biol. 2015;375:101–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das B.B. Role of endomyocardial biopsy for children presenting with acute systolic heart failure. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;35:191–196. doi: 10.1007/s00246-013-0807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radunski U.K., Lund G.K., Saring D., Bohnen S., Stehning C., Schnackenburg B., et al. T1, and T2 mapping cardiovascular resonance imaging technique reveal unapparent myocardial injury in patients with myocarditis. Clin Res Cardiol. 2017;106:10–17. doi: 10.1007/s00392-016-1018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ammirati E., Frigerio M., Adler E.D., Basso C., Birnie D.H., Brambatti M., et al. Management of acute myocarditis and chronic inflammatory cardiomyopathy: an expert consensus document. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13:e007405. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tschope C., Ammirati E., Bozkurt B., Caforio A.L.P., Cooper L.T., Felix S.B., et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy; current evidence and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:169–193. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-00435-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.