To the editor:

Rare cases of renal disease flares after vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have been reported, including IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, or pauci-immune vasculitis.1 Here, we describe an original case of scleroderma renal crisis following mRNA vaccination against SARS-CoV-2.

A 34-year-old woman was referred to our nephrology department for hypertensive emergency and acute kidney injury. Her past medical history included an uncomplicated pregnancy, asthma with annual exacerbations, Raynaud phenomenon since the age of 18 years, and an episode of pericarditis 5 years earlier. The patient had no history of previous coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

One week before admission, she had received a first dose of the BNT162b2 (Pfizer) vaccine. Twenty-four hours after injection, she developed persistent headaches and nausea, and then suddenly suffered from acute vision loss. A consultation in the ophthalmic emergency ward found evidence of stage I hypertensive retinopathy and high blood pressure (220/110 mm Hg). A chest computed tomography scan and brain magnetic resonance imaging scan excluded aortic dissection, pulmonary lesions, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, and cerebral venous thrombosis.

On admission, her blood pressure was 210/120 mm Hg, but her other vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed thickened skin on the face and the back of both hands and wrists—sclerodactyly and oral telangiectasia.

Laboratory studies identified acute kidney injury (serum creatinine [SCr] level of 183 μM; it was 80 μM 1 year earlier), and thrombocytopenia (platelets 92.000/microm3) and anemia (Hb 11.9 g/dl). Lacticodehydrogenase level was increased (368 UI/l, N < 250), haptoglobin was under the detection level (<0.1 g/l), schistocytes were not detected, and a direct antiglobulin test was negative. ADAMTS 13 activity was 97% (N 50–150). Proteinuria was 0.80 g/d, without hematuria. Anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies were positive (53 UI/l, N < 10), whereas anti-dsDNA, anti-SCl 70, anti-centromere, and anti-fibrillarin antibodies were negative. Complement was normal. Lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, and anti-β2GP1 antibodies were absent. A search for shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli in stools was negative. SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike IgG antibody level was 475 AU/ml (positive if > 50), with no anti-nucleocapsid antibody.

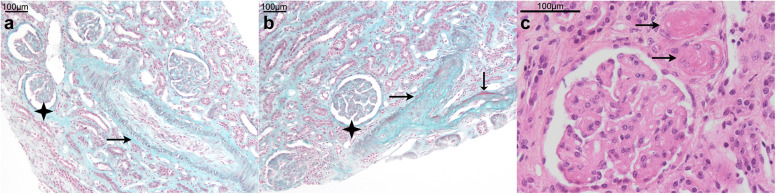

A renal biopsy was performed (Figure 1 ) and contained 50 glomeruli, including 2 globally sclerotic glomeruli. Medium-size artery changes predominated, with mucoid intimal thickening leading to severe narrowing of the vascular lumen. Secondary ischemic glomerular changes were observed, but there was no sign of glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy (no thrombosis, mesangiolysis, or double contouring of the capillary wall). Immunofluorescence staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C1q, Kappa, and Lambda was negative.

Figure 1.

Renal biopsy:(a)interlobular artery with pale mucoid intimal hyperplasia (arrow) leading to severe reduction of the vessel lumen and ischemic glomerular collapse (black star); Masson’s trichrome, original magnification ×100. (b) Arterial occlusion with fibrin deposition (arrows) and ischemic glomeruli (black star); Masson’s trichrome, original magnification ×100. (c) Arteriolar thrombosis (arrows); hematein eosin saffron; original magnification ×400. Bars = 100 μm. To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

Both clinical and biological findings were consistent with the diagnosis of scleroderma renal crisis revealing undiagnosed, preexisting diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis.

One week after the initiation of antihypertensive drugs, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, the patient was discharged with normal blood pressure, no sign of biological hemolysis, and stable renal function. Given this life-threatening complication, no second injection of mRNA vaccine was planned.

In this case, vaccination was temporally associated with hypertensive emergency and acute kidney injury leading to the diagnosis of biopsy-proven scleroderma renal crisis. Renal biopsy features were highly suggestive of this diagnosis, with thrombotic microangiopathy lesions predominating in medium-size vessels.2

According to current guidelines,3 our patient had a typical presentation of scleroderma renal crisis, with hypertensive emergency, ophthalmologic and neurologic involvement, hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, and compatible renal histopathologic changes. Moreover, no other cause of renal thrombotic microangiopathy was identified, including shiga-toxin–induced typical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), other infectious agents (pneumococcal infection, HIV infection), antiphospholipid syndrome, or drug-induced HUS. Finally, the close temporal relationship (7 days) between the first administration of the BNT162b2 vaccine and the appearance of hypertensive symptoms emphasizes the potential role of immune response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination as a trigger of scleroderma renal crisis.

Whether other diseases associated with HUS/thrombotic microangiopathy (such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, complement-mediated atypical HUS, chemotherapy-associated HUS, or organ transplant–associated HUS) can be triggered by mRNA vaccination remains to be determined.

Our case does not modify the favorable safety profile of mRNA vaccination in patients with systemic sclerosis, given the potential occurrence of severe COVID-19 forms in this population.4 Growing experience from large cohorts of patients with systemic sclerosis may provide additional information and allow more robust conclusions to be drawn regarding the vaccination safety profile in this specific population.

Nevertheless, our observation underscores the need for close monitoring of vascular complications in patients with systemic sclerosis after vaccination against COVID-19.

References

- 1.Bomback AS, Kudose S, D’Agati VD. De novo and relapsing glomerular diseases after COVID-19 vaccination: what do we know so far [e-pub ahead of print]? Am J Kidney Dis. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Lusco M.A., Najafian B., Alpers C.E., Fogo A.B. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: systemic sclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:e19–e20. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler E.-A., Baron M., Fogo A.B. Generation of a core set of items to develop classification criteria for scleroderma renal crisis using consensus methodology. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:964–971. doi: 10.1002/art.40809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferri C., Giuggioli D., Raimondo V. COVID-19 and systemic sclerosis: clinicopathological implications from Italian nationwide survey study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e166–e168. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]