Abstract

trans-Bicyclo[4.4.0]decane/decene (such as trans-decalin and trans-octalin)-containing natural products display a wide range of structural diversity and frequently exhibit potent and selective antibacterial activities. With one of the major factors in combatting antibiotic resistance being the discovery of novel scaffolds, the efficient construction of these natural products is an attractive pursuit in the development of novel antibiotics. This highlight aims to provide a critical analysis on how the presence of dense architectural and stereochemical complexity necessitated special strategies in the synthetic pursuits of these natural trans-bicyclo[4.4.0]decane/decene antibiotics.

1. Introduction

Antibiotics have played an integral role in treating bacterial infections for thousands of years; Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928 marked the beginning of a revolution in modern medicine, known as the “Golden Age of Antibiotics”.1 During this time, mankind’s arsenal against pathogenic bacteria grew exponentially, whereby the discovery of a diverse array of antibiotics, including vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, and doxycycline, enabled the treatment of severe, and in some cases, previously untreatable bacterial infections.2 Although these monumental discoveries have saved innumerable lives, this success may be short-lived. Our ability to treat bacterial infections has been compromised by the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which kills 19 000 patients per year in the United States alone.3 This issue is further exacerbated by the misuse and overuse of antibiotics.4 The structural homogeneity of current antibiotics is further hindering our ability to combat resistant pathogens. In fact, the majority of antibiotics currently prescribed are derived from scaffolds introduced between 1935 and 1967,5 with just four of these classes – penicillins, cephalosporins, quinolones, and macrolides – comprising 73% of the new antibacterial compounds filed for patent protection between 1981 and 2005.2 The compounding effect of increasing resistance to antibiotics alongside the declining discovery of novel antibiotics means we are now encountering the post-antibiotic era head-on, and are thus faced with the daunting task of developing efficacious new therapies based on novel antibiotic scaffolds.

The trans-bicyclo[4.4.0]decane/decene (TBD) motifs (including, but not limited to, trans-decalins, trans-octalins, trans-hexahydronaphthalenes and trans-octalones) (Scheme 1a, blue) are found in a variety of natural products which often display promising antibiotic activity and are derived from a wide range of producing organisms.6 Several fungal species produce TBD antibiotics decorated with a tetramic acid motif (Scheme 1a, green), including (−)-equisetin,7 (−)-hymenosetin,8 and (−)-myceliothermophins,9 all of which exhibit differing levels of potency against (methicillin-resistant) S. aureus and Bacillus subtilis. Fungus and bacteria-derived clerodane diterpenoids (Scheme 1a, orange) such as clerocidin,10 and (−)-terpentecin11 display broad-spectrum antibiotic activity as well as antitumor activity. In addition, recent work by Quave and Melander showed that a natural product containing this scaffold plays a critical role in resensitizing MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics. 12 (−)-Aldecalmycin (1)13 and (−)-anthracimycin (2),14 both derived from Streptomyces sp., exhibit potent activity against MRSA as well as Bacillus anthracis, a major threat as a bioterrorism agent.15 Also active against these two species is (+)-kalihinol A (3), isolated from the marine sponge Acanthella sp.16 The diversity in both origin and functionalization of these TBD antibiotics highlights the importance of Nature as a source of inspiration in the search for novel antibiotic scaffolds.

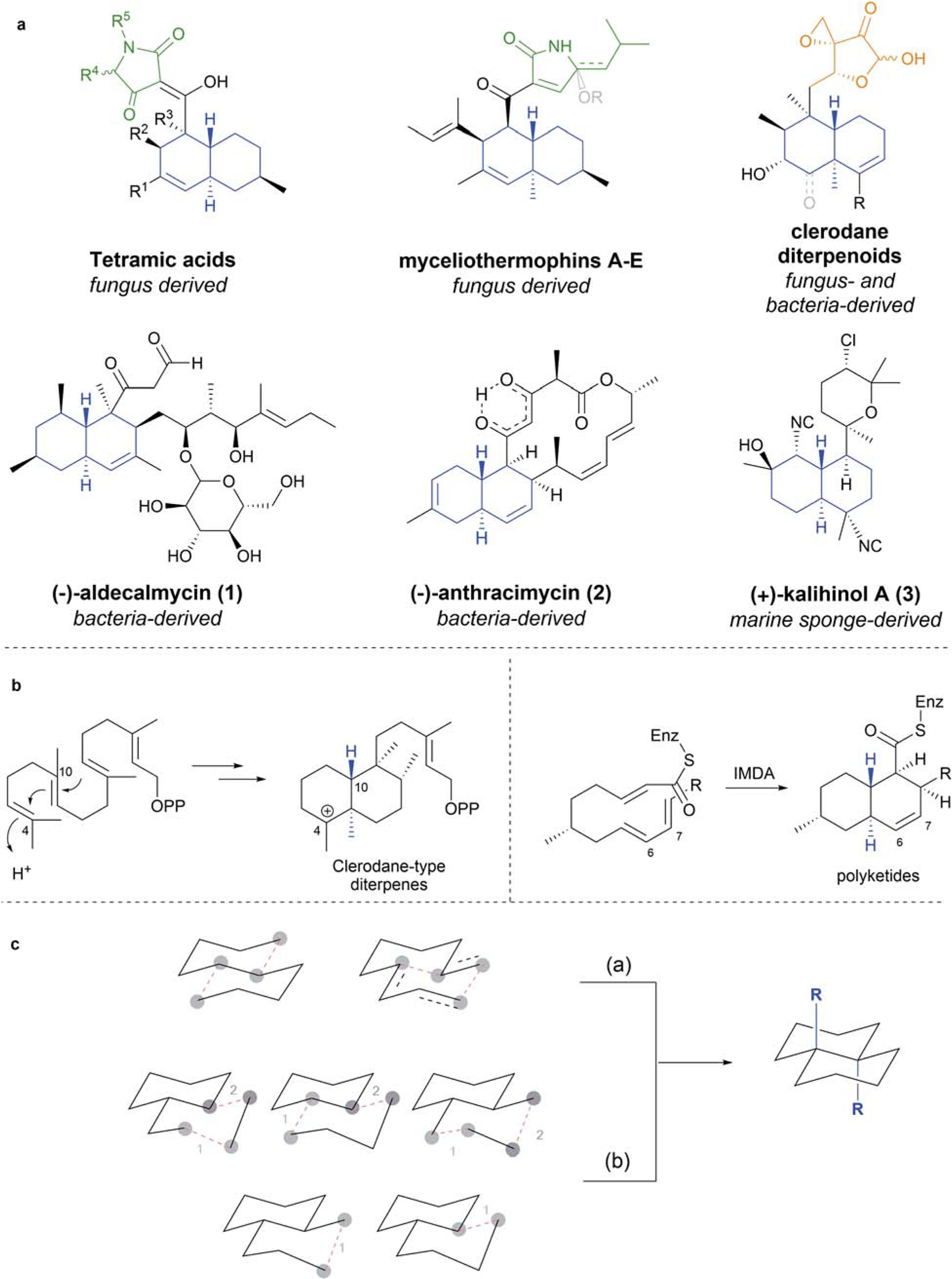

Scheme 1.

(a) Representative examples of TBD-containing antibiotic natural products (TBD motifs highlighted in blue); (b) common biosynthetic pathways to TBDs; (c) general approaches to the synthesis of TBD skeletons; path (a) designates the simultaneous construction of TBD scaffolds and path (b) designates their stepwise construction.

Diterpene skeletons like those found in clerodane diterpenoids are thought to form biosynthetically through cationic polycyclizations followed by C4 and C10 methyl migration,17 while the bicycle of polyketide secondary metabolites are widely thought to originate from intramolecular Diels–Alder cycloadditions (IMDA) (Scheme 1b).18 Indeed, the prevalence of C6–C7 unsaturation in many such natural products would appear to corroborate the IMDA proposal.6 Enzyme-mediated IMDA processes have been identified, for example in the case of lovastatin,19 while other naturally occurring bicyclic terpenoids are postulated to undergo spontaneous (i.e. via non-enzymatically assisted) IMDA reactions when still bound to the polyketide synthase (PKS) machinery.20 It must be stated that additional mechanistic pathways, particularly nonenzymatic, for formation of TBD frameworks should not be excluded.

Syntheses of the TBD scaffold generally employ one of two key approaches: (a) establishing two rings simultaneously and stereospecifically; and (b) establishing each ring in a stepwise fashion, relying on the thermodynamic stability of equatorial substituents on the bridgehead carbons to guide the formation of the trans isomer (Scheme 1c). The TBD skeletons of the aforementioned natural products are characteristically multifunctional with various complex pendant moieties that pose unique synthetic challenges. Thus, devising new and efficient strategies for selectively constructing these highly decorated TBD systems has been important in their pursuit by synthetic chemists.

Previous reviews have specifically discussed annulation approaches to TBDs, the syntheses of cis-bicyclo[4.4.0]decane/decenes, and the construction of bicyclo[4.4.0]decane/decene containing natural products with a focus on isolation or specific functionalities.6,21–25 However, there are no reviews primarily focused on the diverse synthetic approaches required to access the complex scaffolds of TBD containing natural products. The focus of this review is to highlight the strategies utilized to access densely functionalized naturally occurring TBD antibiotics. The target natural products assessed in this review occupy similar chemical space, and their complex frameworks contribute to the bottleneck in their development as novel therapeutics. By shedding light on the various methods that have been successfully employed to access these TBD scaffolds, we hope to inspire further use of these established methods to construct more TBD containing antibiotics and analogous, as well as the development of new methods to efficiently access TBD frameworks. If these scaffolds can be constructed in a more efficient manner, then this will allow for a more streamlined discovery of their mechanism of action and potentially new antibiotic targets, which has been a major bottleneck in the development of effective new antibiotics.

Recent strategies utilized to synthesize the densely substituted TBD scaffold in naturally occurring antibiotics have been primarily limited to two main strategies, namely, IMDA cyclizations and nucleophilic cyclizations, with several miscellaneous approaches also being reported. These strategies will be further elaborated on in the following sections.

2. IMDA cycloadditions

2.1. Introduction

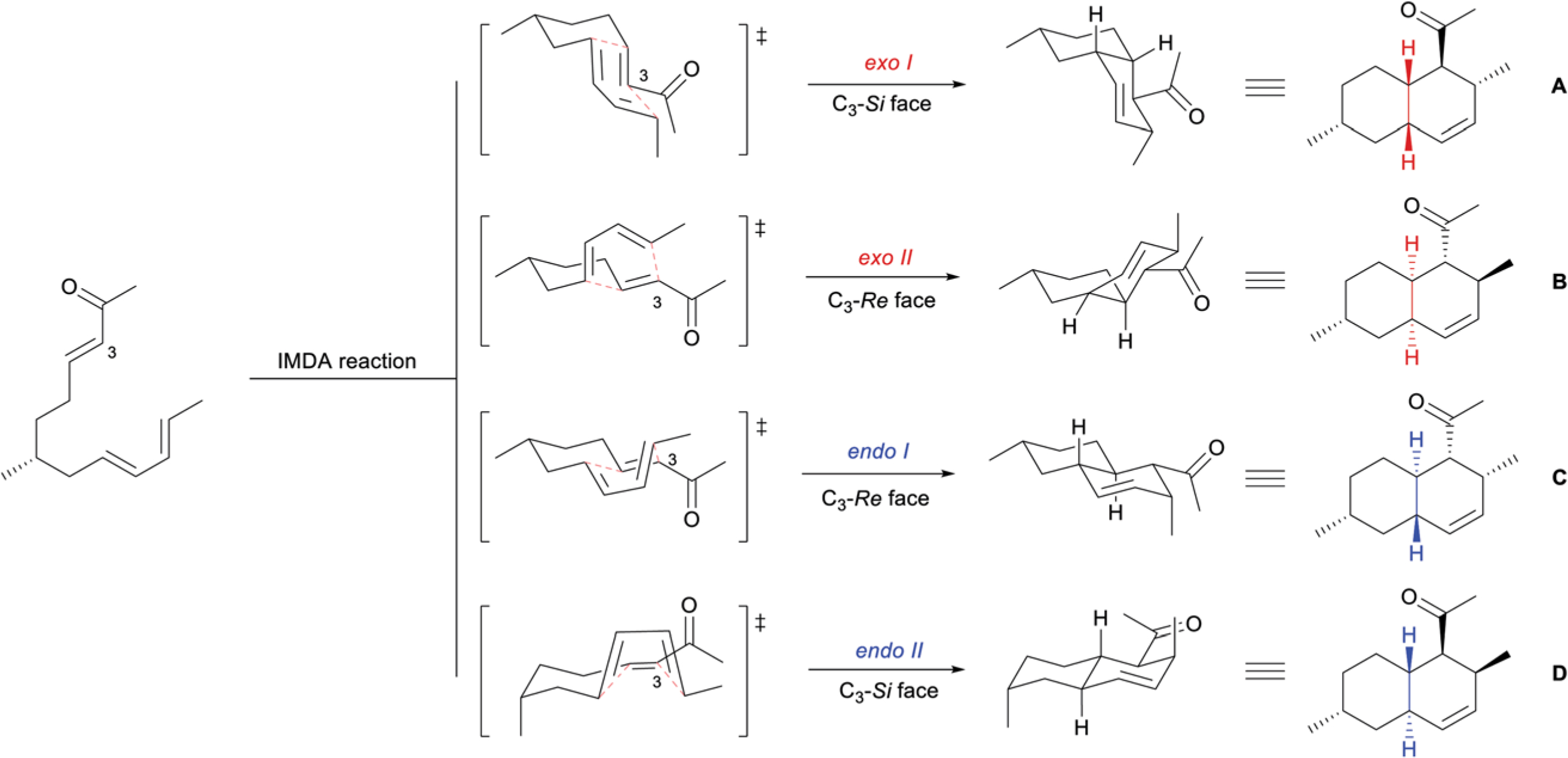

Since its discovery by Otto Diels and Kurt Alder in 1928,26 the Diels–Alder cycloaddition has proven to be a robust method to assemble polycyclic systems efficiently, and with high chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity.27 The relative configuration of the TBD system is dictated by the transition state through which the IMDA reaction proceeds. While the thermodynamically favored exo-transition states deliver corresponding cis-octalin products, A and B, the kinetically favored endo-transition states afford trans-octalin products, C and D (Scheme 2). Additional considerations surrounding substrates and/or reaction conditions can be made to enhance facial selectivity and afford a single enantiomer of these four possible products. This powerful, bioinspired methodology has seen numerous applications for TBD complex syntheses.

Scheme 2.

Possible diastereomeric octalin products produced by IMDA reactions.

2.2. Substrate-controlled IMDA syntheses

Inspired by Nature, substrate-controlled IMDA reactions are a powerful technique used to rapidly build complexity in natural product systems when the inherent preference of the substrate complements the desired configuration of the TBD motif. These reactions are particularly useful, as they can set up to four stereocenters in a single step. The power of this methodology has been exemplified by the recent syntheses of the naturally occurring antibiotics (−)-hymenosetin (4) and (+)-apiosporamide (5).

(−)-Hymenosetin (4), containing the aforementioned tetramic acid moiety, was isolated in 2014 from a virulent strain of the ash dieback fungal pathogen, Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus.8 It displayed strong activity against a series of Gram-positive bacteria, including Micrococcus luteus (DSM 20030, MIC 1.0 μg mL−1), Nocardioides simplex (DSM 20130, MIC 0.52 μg mL−1), and MRSA (N315, MIC 0.83 μg mL−1).8 In 2015, the Opatz group reported the first total synthesis of (−)-4, featuring an IMDA reaction to construct the TBD motif (Scheme 3a).28 Tetraene 6, accessed in four steps from (+)-citronellal, was subjected to the key IMDA reaction, utilizing BF3·Et2O at −78 °C. The facial selectivity of the IMDA reaction was controlled by the preference for the chiral methyl substituent to position pseudo-equatorially in the IMDA transition state 7, giving rise to TBD 8 with a high degree of diastereoselectivity (dr > 10 : 1). A subsequent series of 11 steps, including a Reformatsky reaction and Lacey–Dieckmann cyclization yielded the target tetramic acid, (−)-hymenosetin (4).

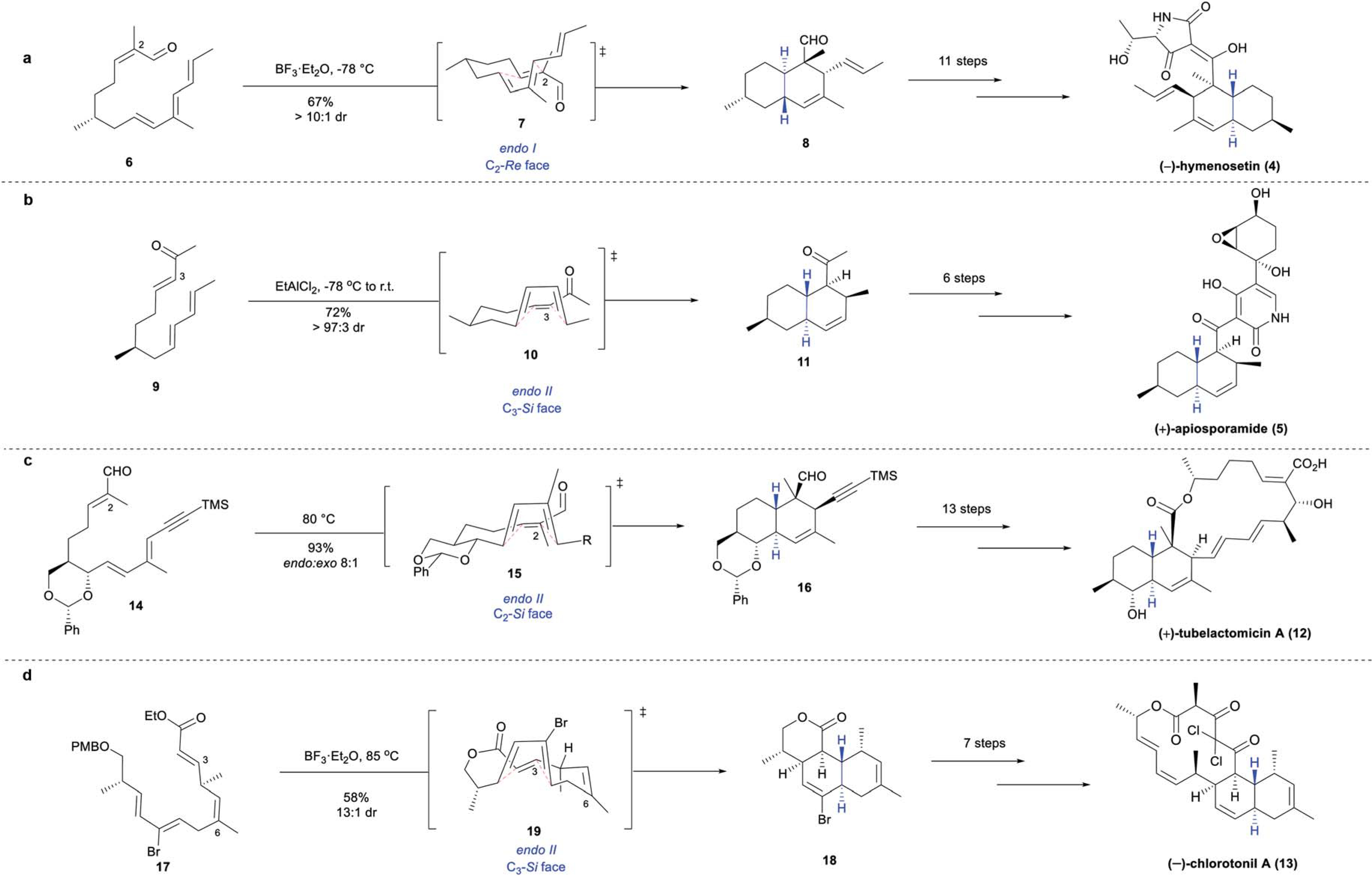

Scheme 3.

Substrate-controlled IMDA syntheses: (a) Opatz’s total synthesis of (−)-hymenosetin (4);28 (b) Williams’ total synthesis of (+)-apiosporamide (5);30 (c) Tadano’s total synthesis of (+)-tubelactomicin A (12);32,33 (d) Kalesse’s total synthesis of (−)-chlorotonil A (13).35

(+)-Apiosporamide (5), containing a unique scaffold in which a 4-hydroxy-2-pyridone moiety is appended to the TBD fragment, was isolated from the coprophilous fungus Apiospora montagnei in 1994.29 While preliminary investigations were motivated by its antifungal properties, it was also found to have antibacterial activity against B. subtilis (ATCC 6051, 32 mm zone of inhibition at 200 μg per disk) and S. aureus (ATCC 29213, 21 mm zone of inhibition at 200 μg per disk).29 The total synthesis of (+)-apiosporamide (5) was completed by the Williams group in 2005,30 and an IMDA reaction was used to construct the TBD core (Scheme 3b). The desired TBD framework was accessed from triene 9, which was obtained from (−)-citronellol in 6 steps. Studies of the key cyclization step revealed that higher temperatures significantly diminished stereocontrol. Thus, the Lewis-acid mediated IMDA reaction of 9 was conducted at −78 °C, proceeding through endo II transition state 10. The diene approached from the C3-Si face of the dienophile, guided by the single methyl stereocenter, similar to (−)-hymenosetin (4), to provide the target TBD 11 with excellent stereoselectivity (dr > 97 : 3). Six additional transformations were performed to afford (+)-5.

The importance of substituents on the linear IMDA substrates in controlling the facial selectivity of IMDA reactions has been highlighted by the syntheses of macrolides (+)-tubelactomicin A (12) and (−)-chlorotonil A (13). In these examples, the IMDA substrates were fine-tuned to obtain the desired the TBD diastereomer.

(+)-Tubelactomicin A (12), isolated in 2000 from a culture broth of actinomycete MK703–102F1 collected in Suwashi (Japan), is a 16-membered macrolide natural product bearing an appended TBD ring system.31 (+)-Tubelactomicin A (12) was found to display potent and genus-specific activity against numerous Mycobacterium strains, including M. smegmatis (ATCC607, MIC 0.10 μg mL−1), M. vaccae (MIC 0.10 μg mL−1) and M. phlei (MIC 0.20 μg mL−1).31 Importantly, (+)-12 was active against drug-resistant Mycobacterium strains, with no cross-resistance to other anti-tuberculosis drugs observed, suggesting a novel mechanism of growth inhibition.31 In 2005, the Tadano group reported the total synthesis of 12, noting that the TBD unit, bearing six contiguous stereocenters, presented a particularly formidable synthetic challenge (Scheme 3c).32,33 Their strategy utilized an IMDA reaction to forge the complex bicyclic system, leveraging an important benzylidene acetal ring appendage to enforce π-facial stereocontrol. Heating 14 to 80 °C facilitated the intramolecular cycloaddition via transition state 15, to provide TBD 16 with high diastereoselectivity (8 : 1 endo : exo). It was proposed that the high π-facial control and endo-selectivity arose from minimization of nonbonding interactions in transition state 15 through the conformational restraint imposed by the benzylidene acetal ring. 13 additional transformations including a Stille coupling and Mukaiyama macrolactonization afforded (+)-tubelactomicin A (12).

Isolated from myxobacterium Sorangium cellulosum, So ce1525, (−)-chlorotonil A (13) was characterized as a TBD-fused 14-membered macrolide bearing a gem-dichloride moiety.34 (−)-Chlorotonil A (13) exhibited strong antibiotic activity against a series of Gram-positive bacteria including M. luteus (DSM-1790, MIC 0.0125 μg mL−1), B. subtilis (DSM-10, MIC ≤ 0.003 μg mL−1), and S. aureus (Newman, MIC 0.006 μg mL−1).20 The total synthesis of (−)-13 was realized by Kalesse and coworkers in 2008, utilizing a strategic IMDA reaction of 17, which promoted formation of the desired TBD adduct 18 through a halogen-directing effect (Scheme 3d).35 Accessed in 10 linear steps from (R)-Roche ester, tetraene 17 was treated with BF3·Et2O at 85 °C to facilitate the IMDA cyclization simultaneously with PMB removal and transesterification to afford 18 with high diastereoselectivity (dr 13 : 1). Analysis of the proposed cyclic reaction intermediates uncovered the significant effect of steric repulsion between the bromide and C6 methyl group, thereby favoring intermediate 19 with the diene approaching the C3-Si face of the dienophile, leading to predominant formation of 18. With the desired TBD scaffold 18 formed, an additional 7 steps completed the total synthesis of (−)-chlorotonil A (13).

2.3. Chiral auxiliary-controlled IMDA syntheses

In many cases, the structure of the substrate does not lend itself to favorable facial control and endo selectivity required to construct the desired trans-bicyclic systems through an IMDA approach. Chiral auxiliaries are useful pendant moieties which are applied to invert the inherent undesirable facial selectivity of certain substrates in the formation of complex TBDs using IMDA reactions.

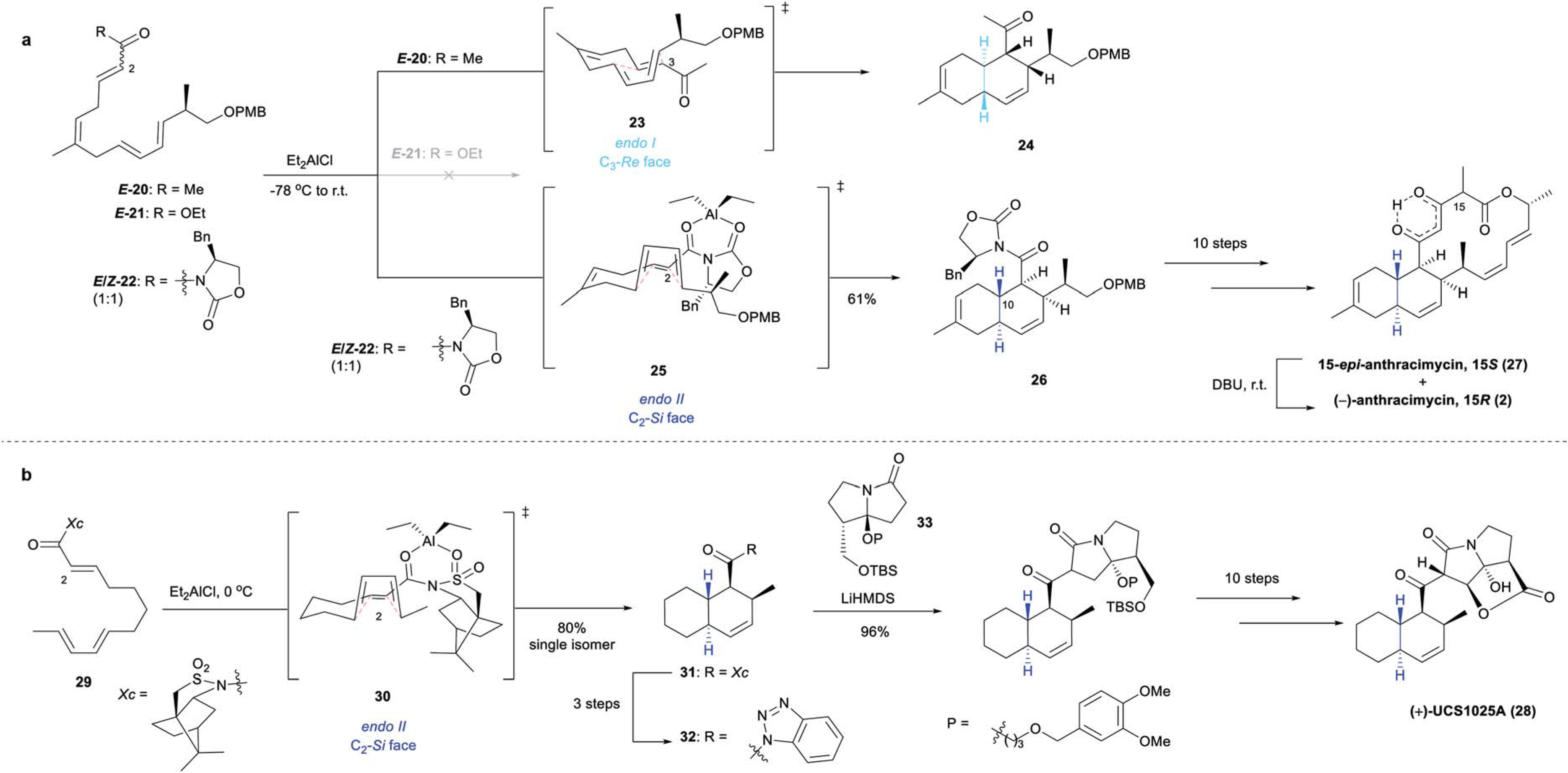

The tricyclic macrolide (−)-anthracimycin (2) was isolated from Streptomyces sp. CNH365 in 2013.14 (−)-Anthracimycin (2) shows remarkable structural similarities to the aforementioned (−)-chlorotonil A (13). (−)-Anthracimycin (2) demonstrated potent in vitro activity against a series of MRSA strains (MIC 0.03–0.0625 μg mL−1), and exhibited in vivo protection against MRSA-induced mortality in mice (single dose, 1 mg kg−1).36 Significant activities were also found against the bioterrorism agent B. anthracis (UM23C1–1, MIC 0.031 μg mL−1) as well as against M. tuberculosis (H37Ra, MIC 1–2 μg mL−1).14,36 The minimal toxicity of (−)-2 to human cells (IC50 70 mg L−1) makes it a valuable lead in the development of novel antibiotics to combat MRSA.36 The first total synthesis of this potent naturally occurring antibiotic has recently been realized through a collaborative effort between the Brimble and Wuest groups (Scheme 4a).37,38 A series of tetraene substrates (20–22), accessed in 8 steps from (S)-Roche ester, were tested in the key IMDA reaction. Cyclization of ester IMDA substrate, E-21, similar to that reported by Rahn and Kalesse35 during their aforementioned synthesis of (−)-13, proved unproductive. Enone E-20 proceeded through the endo I transition state 23, affording the undesired diastereomer 24 as the major IMDA adduct under all conditions tested. However, the inherent facial selectivity of the cycloaddition can be inverted through application of a chiral auxiliary. Lewis acid mediated IMDA reaction of tetraene 22 (1 : 1 mixture of E/Z-isomers) proceeded through the endo II transition state 25 and yielded IMDA adduct 26, possessing the desired stereochemistry, albeit as a 1 : 1 mixture with its C10 epimer (resulting from cycloaddition of C2-Z-22 via the same transition state). These epimers were separated following PMB deprotection, which was followed by an additional 9 steps, affording 2 as a 1 : 1 mixture with 15-epi-anthracimycin (27). Base-mediated epimerization of the mixture provided (−)-anthracimycin (2) as a single diastereomer.

Scheme 4.

Auxiliary controlled IMDA syntheses: (a) Evans’ oxazolidinone facilitated IMDA based total synthesis of (−)-anthracimycin (2);37,38,62 (b) Oppolzer’s camphor sultam enabled IMDA approach to (+)-UCS1025A (28).63

(+)-UCS1025A (28), comprised of a TBD skeleton linked to a pyrrolizidine motif by an acyl bond, was isolated from the fungus Acremonium sp. KY4917 in 1999.39 (+)-UCS1025A (28) displayed micromolar antibiotic activities against Gram-positive S. aureus (ATCC 6538P, MIC 1.3 μg mL−1), B. subtilis (No. 10707, MIC 1.3 μg mL−1), Enterococcus hirae (ATCC 10541, MIC 1.3 μg mL−1), and Gram-negative Proteus vulgaris (ATCC 6897, MIC 5.2 μg mL−1). In 2012, Kan and coworkers reported the second total synthesis of (+)-28 40 (the first of which will be discussed in the next section). Triene 29, bearing a chiral Oppolzer’s sultam auxiliary underwent Lewis acid-mediated cycloaddition via transition state 30 to afford desired TBD 31 as a single diastereomer (Scheme 4b). Blocking of the C2-Re face of the dienophile by the sultam auxiliary promoted cycloaddition at the opposite face lending to high stereoselectivity. Further transformations, including coupling of benzotriazole 32 with pyrrolizidinone 33 provided (+)-UCS1025A (28).

2.4. Miscellaneous IMDA syntheses

While auxiliary-controlled IMDA reactions have proven extremely useful in the stereoselective construction of complex TBD systems in natural products, removal of the auxiliary can sometimes be problematic. As such, organocatalyzed IMDA reactions are emerging as an attractive alternative, as aldehyde substrates can be activated chemoselectively, and the directing group established in situ is also cleaved after promoting the desired transformation.

The efficiency of this methodology was highlighted in the first total synthesis of (+)-UCS1025A (28) by the Danishefsky group in 2005,41 who utilized an enantioselective IMDA reaction promoted by an organocatalyst developed by MacMillan and coworkers42 (Scheme 5a). Reversible condensation of the imidazolidinone catalyst with aldehyde 34 formed iminium ion 35 in situ, (lowering the LUMO energy to activate the dienophile), which underwent Diels–Alder cyclization through endo II transition state 35, followed by iminium hydrolysis, to afford TBD (+)-36.42 Importantly, all four stereocenters were set in a single step with excellent stereoselectivity. Using this same methodology, the Danishefsky group prepared the enantiomer (−)-36, which was transformed in 3 additional steps, including incorporation of the pyrrolizidine moiety, to the natural product (+)-28.

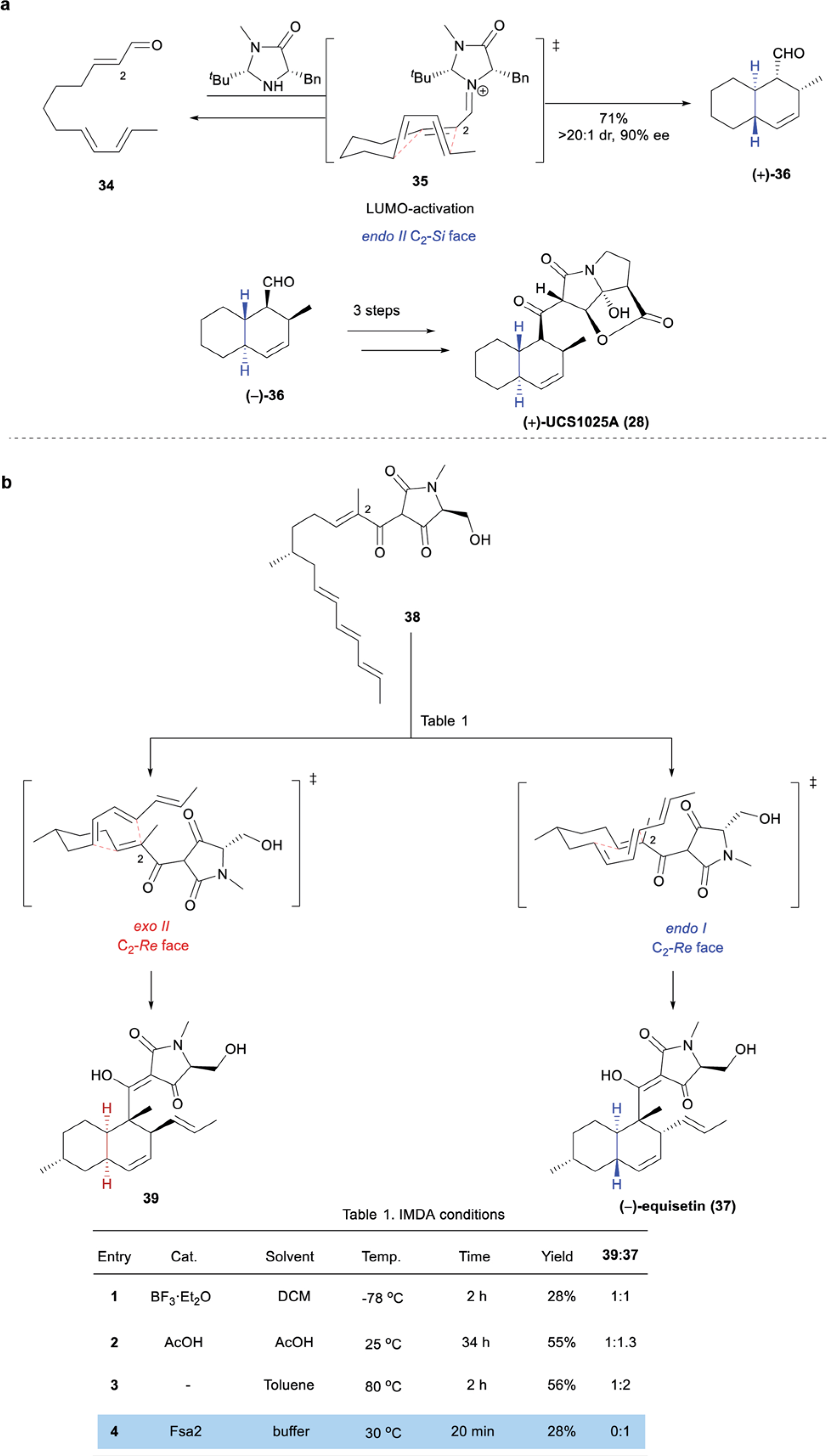

Scheme 5.

Miscellaneous IMDA syntheses: (a) Organocatalytic synthesis of (+)-UCS1025A (28) by Danishefsky;41 (b) chemo-enzymatic IMDA synthesis of (−)-equisetin (37) by Gao and coworkers.43

Chemo-enzymatic IMDA reactions are valuable in the late-stage construction of densely functionalized TBD systems. This methodology provides a high degree of stereoselectivity without the need for directing groups, and has the additional benefit of elucidating elements of the biosynthetic pathway to the desired natural products, as exemplified by the recent synthesis of (−)-equisetin (37) by Gao and coworkers.

(−)-Equisetin (37) was originally isolated from the white mold Fusarium equiseti in 1974.7 This fungal metabolite displayed potent antibiotic activity (B. subtilis B-543, MIC 0.5 μg mL−1, and S. aureus B-313, MIC 0.5 μg mL−1).7 In 2017, Gao and coworkers reported the chemo-enzymatic synthesis of 37 employing the Diels-Alderase enzyme Fsa2 to selectively form the TBD moiety (Scheme 5b).43 Tetraene 38, obtained in 7 steps from (+)-citronellal, was subjected to a series of conditions in an attempt to access (−)-37. Both Lewis acid-catalyzed and thermally-promoted Diels–Alder conditions failed to facilitate stereoselective conversion of 38 to the desired TBD natural product (Table 1, Scheme 5b). Lewis acid-mediated IMDA reaction of 38 delivered (−)-37 and its cis-fused epimer 39 in a 1 : 1 ratio (entry 1). Marginal improvements in this ratio were observed upon treatment of 38 with AcOH or simply heating 38 in toluene (entries 2 and 3). Opportunely, treatment of 38 with the Diels-Alderase enzyme, Fsa2, expressed and purified from E. coli, resulted in complete conversion of 38 to (−)-37 with no detectable formation of epimer 39 (entry 4). This bioinspired synthesis showcases the power of enzymatic catalysis in conducting late-stage diastereoselective Diels–Alder cyclizations for the construction of TBD scaffolds.

3. Nucleophilic cyclizations

3.1. Wieland–Miescher ketones

As illustrated herein, IMDA cycloadditions have seen wide usage in the pursuit of TBD systems, and this methodology provides these bicyclic motifs with a reactive pendant carbonyl moiety at C1 for further functionalization (Scheme 6a). However, the bicyclic ring structures of clerodane diterpenoids possess additional structural elements that are poorly accessible through this methodology, in particular, the congested C5 quaternary center. The Wieland–Miescher ketone (40) is accessed through a nucleophilic cyclization/dehydration sequence of tricarbonyl 41, to forge this C5 quaternary center (Scheme 6b).44,45 The different reactivity of the two carbonyls in 40 can then be exploited for the selective incorporation of various structural moieties at positions such as C9 (Scheme 6a and b).

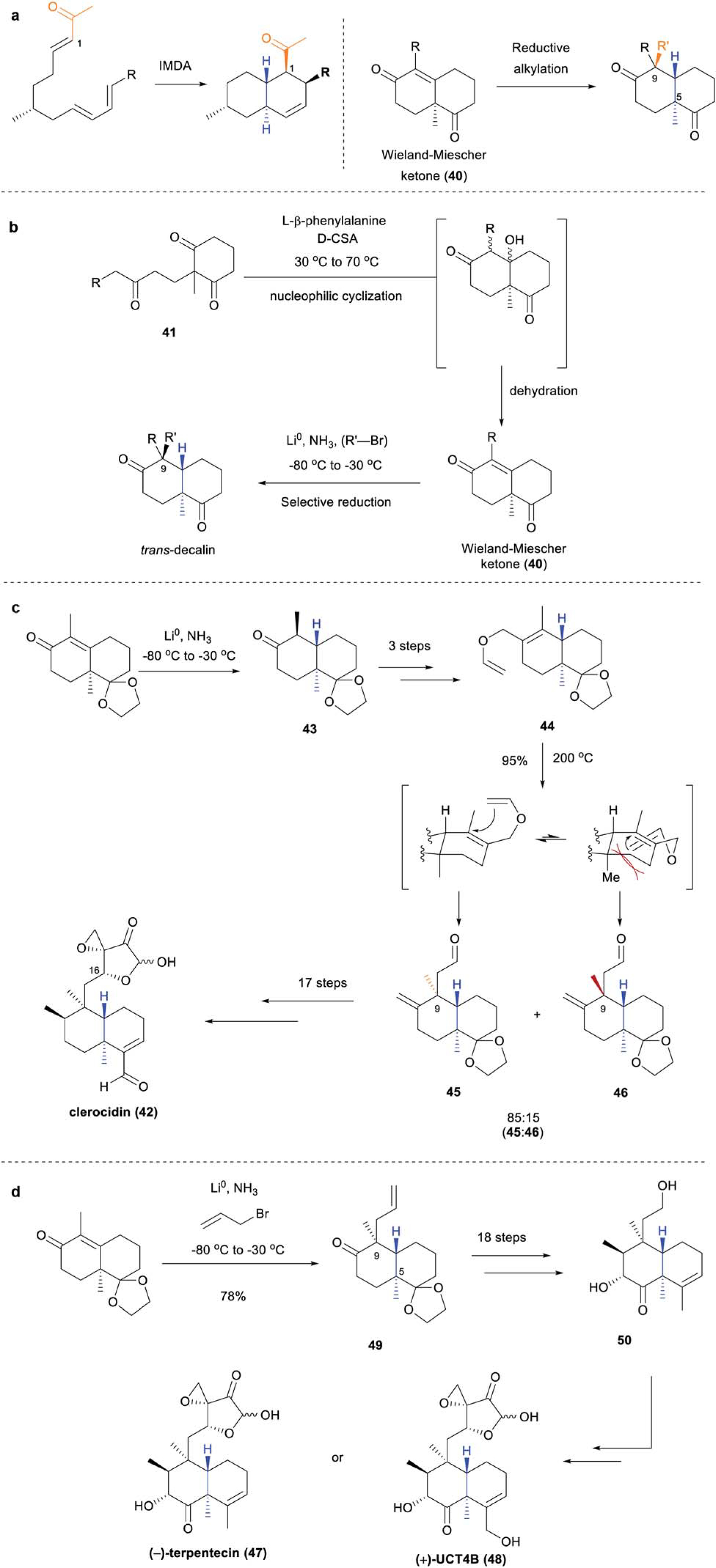

Scheme 6.

Use of Wieland–Miescher ketone (40) in the synthesis of TBD natural products: (a) incorporation of reactive functionalities at different positions on the TBD scaffold; (b) general construction of TBD scaffolds through Robinson annulation; (c) Theodorakis’s total synthesis of clerocidin (42);47 (d) Theodorakis’s formal synthesis of (−)-terpentecin (47) and (+)-UCT4B (48)51

The clerodane diterpenoid clerocidin (42), previously called PR-1350, was isolated in 1983 from the fungus Oidiodendron truncatum, and displays a wide range of activity against Gram-positive (M. luteus 2495, MIC < 0.05 μg mL−1, and S. aureus 1276, MIC 0.1 μg mL−1) and Gram-negative bacteria (Bacteroides fragilis 9844, MIC < 0.05 μg mL−1, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa 9545, MIC 0.8 μg mL−1).46 Further biological studies elucidated DNA topoisomerase II inhibition as the mechanism by which this natural product exerts its antibacterial and antitumor effects.46 Intrigued by its unique biological activity, Theodorakis and coworkers embarked on the first total synthesis of 42 in 1998 (Scheme 6c).47 Stereoselective construction of the trans-decalin framework was achieved via the aforementioned Robinson annulation–dehydration–stereoselective reduction sequence and site-selective acetalization to give TBD 43, which was then converted to allyl vinyl ether 44 in 3 steps.48,49 Claisen rearrangement was then performed to stereoselectively install the C9 quaternary center. Facial preference for top face attack was derived from the steric repulsion between the angular methyl and vinyl group on the bottom face, thus predominant formation of aldehyde 45 was observed (85 : 15, 45 : 46). An additional 17 steps, including a novel asymmetric homoallenylboration reaction to install the C16 chiral alcohol, were undertaken, affording 42 as a single enantiomer.

The highly oxygenated natural product, (−)-terpentecin (47) bears significant structural similarity to clerocidin (42), and was originally isolated in 1985 from the bacteria Kitasatosporia sp. MF730-N6,11 and again from Streptomyces sp. along with (+)-UCT4B (48) in 1992.50 Akin to the biological profile of (−)-clerocidin (42), these two compounds displayed broad-spectrum antibiotic activity ((−)-47: B. subtilis PCI 219, MIC < 0.05 μg mL; S. aureus Smith, MIC < 0.05 μg mL; E. coli K-12, MIC 3.12 μg mL; Shigella dysenteriae JS 11910, MIC < 0.05 μg mL. (+)-48: B. subtilis No. 10707, MIC 8.3 μg mL; S. aureus ATCC 6538, MIC 4.1 μg mL; K. pneumonia ATCC 10031, MIC 2.1 μg mL−1).11,50 Similar to clerocidin, these two compounds also captured the attention of the Theodorakis group, however, a more direct approach was taken to set the C9 stereocenter and construct the TBD core of (−)-47 and (+)-48 (Scheme 6d).51 Stereoselective Birch reductive alkylation of Wieland–Miescher ketone with allyl bromide afforded the desired TBD 49. The stereoselectivity was proposed to arise from the steric clash with the C5 methyl group rendering bottom-face approach of the electrophile unfavorable, thus resulting in predominant formation of 49. The fully functionalized core fragment 50 was afforded after 18 additional steps. Core fragment 50 could then feasibly be elaborated to both (−)-47 and/or (+)-48 using established protocols.473.2 Nucleophilic cascade sequences

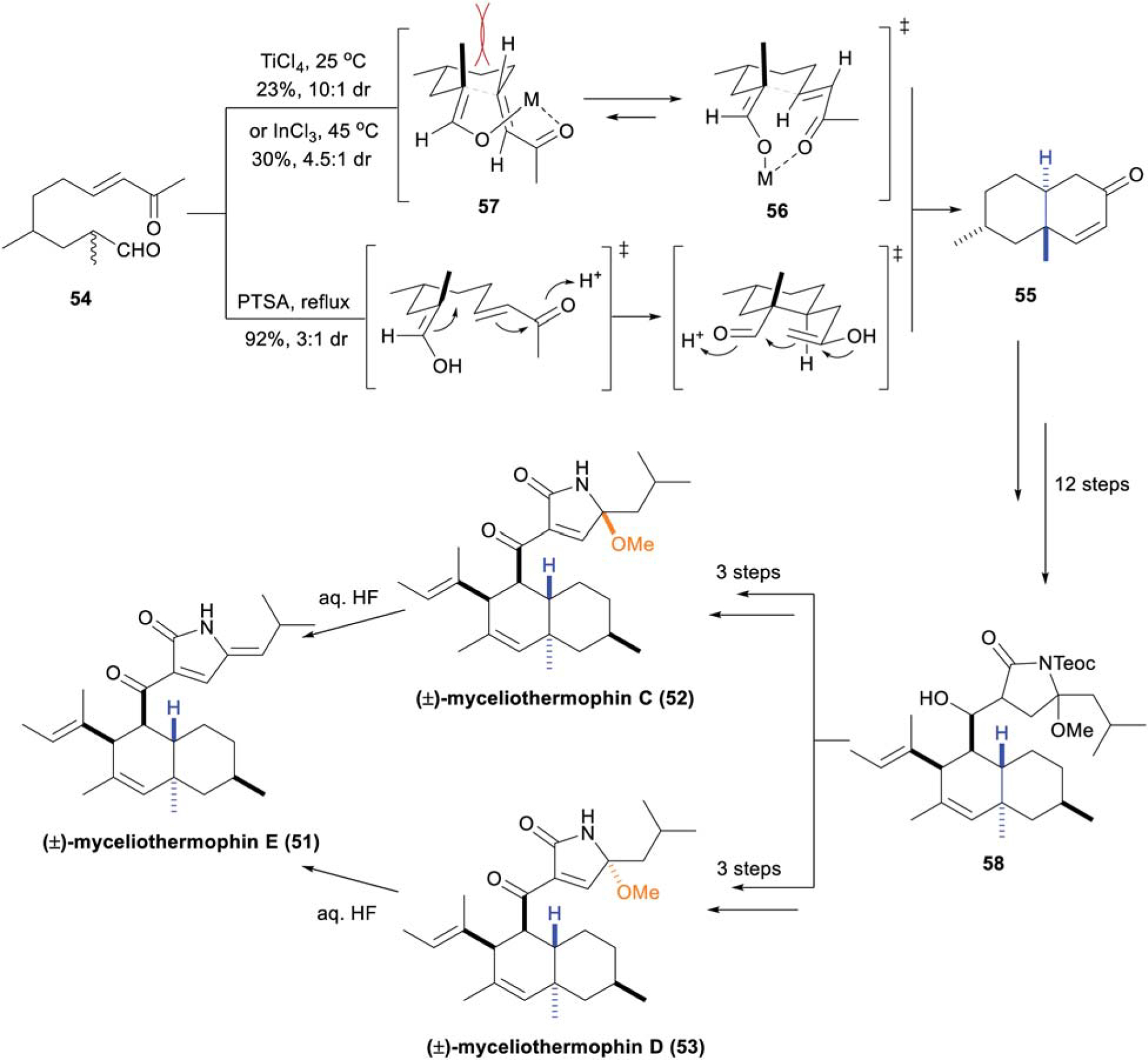

Five tetramic acid polyketide natural products, myceliothermophins A–E were originally isolated from the thermophilic fungus Myceliophthora thermophila in 2007.9 Although these natural products are more potent against various cancer lines, (−)-myceliothermophin E (51) has moderate antibacterial activity against MRSA (MIC 15.8 μM).52 The first total synthesis of myceliothermophins C–E (51–53) was accomplished by Uchiro and coworkers in 2012 utilizing an IMDA approach to construct the trans-octalone framework.53 Recognizing the challenges arising from construction and reaction of the complex polyene IMDA substrates, Nicolaou and coworkers sought an alternative approach, employing what they termed an “unusual cascade sequence of reactions” to access the TBD system (Scheme 7).54 Ketoaldehyde 54, synthesized from (±)-citronellal over 3 steps (although both enantiomers are commercial available, the authors commenced the synthesis from racemic materials for cost effectiveness), was extensively screened under a variety of reaction conditions to access octalone 55. This led to the initial discovery that Lewis-acidic conditions, namely TiCl4 and InCl3, favored formation of the desired octalone 55 with good diastereoselectivity (dr 10 : 1 and 4.5 : 1, respectively). The presence of these metals enhanced preference for transition state 56, wherein favorable overlap of the enolate HOMO and enone LUMO are observed, compared to the unfavorable steric clash between the methyl group and the vinylic proton in transition state 57. Significantly higher yields for the biscyclization cascade were observed using catalytic p-toluenesulfonic acid (PTSA), albeit with decreased diastereoselectivity (dr 3 : 1). With the desired TBD 55 in hand, an additional 12 steps gave intermediate 58 (as a mixture of diastereomers), which was then further elaborated to (±)-51–53. This synthesis highlights the importance of developing novel methods of TBD construction when access to suitable IMDA substrates is challenging.

Scheme 7.

Nicolaou’s divergent total synthesis of (±)-myceliothermophins C–E (51–53).54

4. Miscellaneous reactions

4.1. Sigmatropic rearrangements

Sigmatropic rearrangements have found use in the efficient construction of some of the most densely functionalized TBD natural products, such as (−)-tetrodecamycin (59) and (−)-equisetin (37), making it an important method for synthesizing these particularly formidable targets.

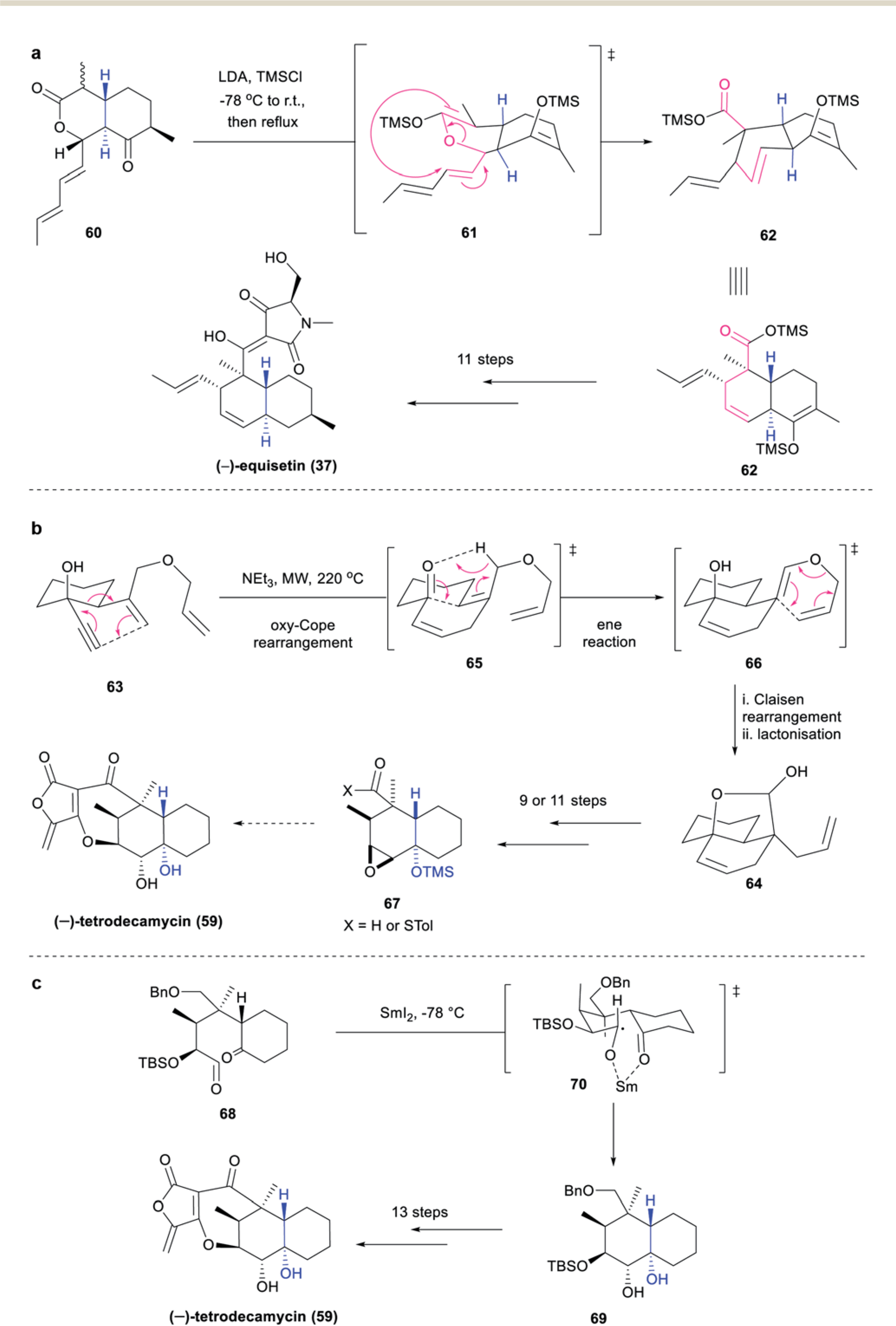

Danishefsky employed an intramolecular lactonic Claisen rearrangement for the formation of the TBD system of aforementioned natural product (−)-equisetin (37) (Scheme 8a).55 Treatment of 60 with lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) and trimethylsilyl chloride (TMSCl) gave the corresponding silyl dienol ether, which then underwent intramolecular lactonic Claisen rearrangement. Due to the constrained nature of the cyclic system, stereospecific [3,3]-rearrangement through boat-like transition state 61 occurred, furnishing the desired TBD 62 as the major product.56 Conversion of 62 to (−)-37 was then accomplished in 11 additional steps.

Scheme 8.

Miscellaneous approaches to the synthesis of naturally occurring TBD antibiotics: (a) Danishefsky’s intramolecular lactonic Claisen rearrangement enabled total synthesis of (−)-equisetin (37);54 (b) Barriault’s oxy-Cope/ene/Claisen rearrangement approach to the TBD framework of (−)-tetrodecamycin (59);58 (c) Tatsuta’s SmI2-mediated radical cyclization process to (−)-tetrodecamycin (59).59

(−)-Tetrodecamycin (59), an antibiotic compound featuring a 6,6,7,5-tetracyclic skeleton, was isolated from the culture broth of Streptomyces sp. MJ885-mF8 in 1994.57 Along with its moderate activity against several Gram-positive (S. aureus FDA 209P, MIC 6.25 μg mL; B. anthracis, MIC 6.25 μg mL−1) and Gram-negative pathogens (Xanthomonas oryzae, MIC 12.5 μg mL−1), it exhibited distinct activity against Pasteurella piscicida (sp. 6395, MIC 1.56 μg mL−1), a pathogen responsible for causing pseudotuberculosis in cultured fish. A key challenge in the synthesis of (−)-59 is accessing its densely substituted central cyclohexane ring, containing two quaternary centers, a trans-fusion in the decalin scaffold and six contiguous stereocenters. In 2005, Barriault and coworkers reported the synthesis of the TBD scaffold of (−)-59 through a tandem oxy-Cope/ene/Claisen rearrangement (Scheme 8b).58 The oxy-Cope precursor 63, obtained in 5 steps from cyclohexene oxide, was subjected to microwave irradiation, affording 64 in excellent yield and stereoselectivity. The transformation was proposed to occur via initial oxy-Cope rearrangement to intermediate 65, followed by ene reaction to 66, then a Claisen rearrangement and lactonization to furnish the desired TBD 64. This was then further elaborated to 67, however incorporation of the tetronic acid moiety to complete this synthesis has yet to be disclosed.

4.2. Radical cyclizations

Radical cyclizations offer an attractive alternative reactivity mode by which to access sterically congested products, such as those commonly seen in TBD systems. In 2006, Tatsuta and coworkers became the first group to complete the total synthesis of (−)-tetrodecamycin (59) utilizing a stereoselective SmI2-mediated pinacol cyclization to construct the TBD core (Scheme 8c).59 Ketoaldehyde 68, derived from (S)-(−)-5-hydroxymethyl-2(5H)-furanone in 13 steps was treated with SmI2, promoting the critical pinacol cyclization and affording the desired TBD 69 as a single isomer. The excellent stereoselectivity was believed to arise from the preference for the more stable chair-like transition state 70 through O–Sm chelation. Further manipulations, including formation of the tetronic acid motif, ultimately completed the synthesis of (−)-59 in a total of 27 steps.

5. Conclusions

The significance of TBD containing natural products as inspiration in the development of novel antibiotics is made evident through the diversities in their chemical structures and often potent biological activities. Synthetic pursuits have led to the construction of several promising antibiotics containing these densely functionalized scaffolds. Many top synthetic groups have achieved elegant syntheses of these compounds utilizing a variety of approaches to access the TBD motif.

IMDA reactions continue to be the most robust and frequented method to access densely substituted TBD scaffolds, as has been made evident through the successful syntheses of a plethora of complex TBD-containing natural products. While substrate controlled-IMDA reactions are appealing for the inherent simplicity of the reaction, the application of chiral auxiliaries is a useful means for reversing undesired facial selectivities in these reactions. The use of organocatalysts and enzymes are also attractive alternatives since they enable the stereospecific synthesis of TBD scaffolds without the necessary appendage of chiral auxiliaries which are frequently difficult to remove. The use of Cope and Claisen rearrangements and Wieland–Miescher-type ketones demonstrate the significant value of classical chemical reactions in forming TBDs possessing strategically placed functional handles and congested quaternary centers. Finally, Tatsuta’s59 synthesis of (−)-tetrodecamycin (59) displayed the value of radical cyclizations in the assembly of densely functionalized TBD systems.

We encourage the readership to consider two paths forward when pursuing these scaffolds to combat antibiotic resistance. The first is the continued development of new methods to enable the construction of these densely functionalized scaffolds. For example, in a recent review, Baran and coworkers highlighted the potential of radicals as reactive intermediates in the stereoselective construction of complex natural products,60 Electrochemical, photochemical, and other radical-based methods indeed hold a great deal of potential in the construction of TBD systems. This bolsters the case for syntheses like that of (−)-tetrodecamycin (59). Additionally, arene dearomatization could be further developed to access structurally complex trans-fused bicycles.61 The second involves a collaborative effort between synthetic chemists and biologists, wherein efficient access to these TBD systems will enable more comprehensive biological studies including SAR, target identification, and deducing mechanism of action. The latter approach will hopefully inform the rational design of more potent derivatives unavailable in Nature. Nevertheless, with the plethora of powerful synthetic tools available to chemists, the synthesis of novel TBD antibiotics and derivatives is a promising and powerful pursuit for the development of next-generation antibiotics.

7. Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge funding support from the National Science Foundation (CHE1531620 to ARK; CHE2003692 to WMW), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM119426 to WMW), Royal Society of New Zealand Te Apārangi for a Rutherford Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (EKD), the Kate Edger Educational Charitable Trust for a Post-Doctoral Research Award (EKD) and the Maurice Wilkins Centre for Molecular Biodiscovery and the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (5000449 to MAB) for financial support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

8 Notes and references

- 1.Lobanovska M and Pilla G, Yale J. Biol. Med, 2017, 90, 135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischbach MA and Walsh CT, Science, 2009, 325, 1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies J and Davies D, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev, 2010, 74, 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipsitch M and Samore MH, Emerging Infect. Dis, 2002, 8, 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman DJ and Cragg GM, J. Nat. Prod, 2007, 70, 461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li G, Kusari S and Spiteller M, Nat. Prod. Rep, 2014, 31, 1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burmeister HR, Bennet GA, Vesonder RF and Hesseltine CW, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother, 1947, 5, 634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halecker S, Surup F, Kuhnert E, Mohr KI, Brock NL, Dickschat JS, Junker C, Schulz B and Stadler M, Phytochemistry, 2014, 100, 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y-L, Lu C-P, Chen M-Y, Chen K-Y, Wu Y-C and Wu S-H, Chem.–Eur. J, 2007, 13, 6985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen NR, Lorck HOB and Rasmussen PR, J. Antibiot, 1983, 36, 753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamamura T, Sawa T, Isshiki K, Masuda T, Homma Y, Iinuma H, Naganawa H, Hamada M, Takeuchi T and Umezawa H, J. Antibiot, 1985, 38, 1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dettweiler M, Melander RJ, Porras G, Risener C, Marquez L, Samarakoon T, Melander C and Quave CL, ACS Infect. Dis, 2020, 6, 1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawa R, Takahashi Y, Itoh S, Shimanaka K, Kinoshita N, Homma Y, Hamada M, Sawa T, Naganawa H and Takeuchi T, J. Antibiot, 1994, 47, 1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang KH, Nam SJ, Locke JB, Kauffman CA, Beatty DS, Paul LA and Fenical W, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2013, 52, 7822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer RC, J. Clin. Pathol, 2003, 56, 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang CWJ, Patra A, Roll DM and Scheuer PJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1984, 106, 4644. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li R, Morris-Natschke SL and Lee K-H, Nat. Prod. Rep, 2016, 33, 1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stocking EM and Williams RM, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2003, 42, 3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auclair K, Sutherland A, Kennedy J, Witter DJ, Van den Heever JP, Hutchinson CR and Vederas JC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2000, 122, 11519. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jungmann K, Jansen R, Gerth K, Huch V, Krug D, Fenical W and Müller R, ACS Chem. Biol, 2015, 10, 2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varner MA and Grossman RB, Tetrahedron, 1999, 55, 13867. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokoroyama T, Synthesis, 2000, 611. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh V, Iyer SR and Pal S, Tetrahedron, 2005, 61, 9197. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhambri S, Mohammad S, Buu ONV, Galvani G, Meyer Y, Lannou M-I, Sorin G and Ardisson J, Nat. Prod. Rep, 2015, 32, 841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akita H, Heterocycles, 2013, 87, 1625. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diels O and Adler K, Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem, 1928, 460, 98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takao K-I, Munakata R and Tadano K-I, Chem. Rev, 2005, 105, 4779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kauhl U, Andernach L, Weck S, Sandjo LP, Jacob S, Thines E and Opatz T, J. Org. Chem, 2016, 81, 215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alfatafta AA, Gloer JB, Scott JA and Malloch D, J. Nat. Prod, 1994, 57, 1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams DR, Kammler DC, Donnell AF and Goundry WRF, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2005, 44, 6715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Igarashi M, Hayashi C, Homma Y, Hattori S, Kinoshita N, Hamada M and Takeuchi T, J. Antibiot, 2000, 53, 1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Motozaki T, Sawamura K, Suzuki A, Yoshida K, Ueki T, Ohara A, Munakata R, Takao K-I and Tadano K-I, Org. Lett, 2005, 7, 2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motozaki T, Sawamura K, Suzuki A, Yoshida K, Ueki T, Ohara A, Munakata R, Takao K-I and Tadano K-I, Org. Lett, 2005, 7, 2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerth K, Steinmetz H, Höfle G and Jansen R, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2008, 47, 600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahn N and Kalesse M, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2008, 47, 597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hensler ME, Jang KH, Thienphrapa W, Vuong L, Tran DN, Soubih E, Lin L, Haste NM, Cunngingham ML, Kwan BP, Shaw KJ, Fenical W and Nizet V, J. Antibiot, 2014, 67, 549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davison EK, Freeman JL, Zhang W, Wuest WM, Furkert DP and Brimble MA, Org. Lett, 2020, 22(14), 5550–5554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freeman JL, Brimble MA and Furkert DP, Org. Chem. Front, 2019, 6, 2954. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakai R, Ogawa H, Asai A, Ando K, Agaisuma T, Maisumiya S, Akinaga S, Yamashita Y and Mizukami T, J. Antibiot, 2000, 53, 294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uchida K, Ogawa T, Yasuda Y, Mimura H, Fujimoto T, Fukuyama T, Wakimoto T, Asakawa T, Hamashima Y and Kan T, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2012, 51, 12850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambert TH and Danishefsky SJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2006, 128, 426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson RM, Jen WS and MacMillan DWC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2005, 127, 11616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Zheng Q, Yin J, Liu W and Gao S, Chem. Commun, 2017, 53, 4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rapson WS and Robinson R, J. Chem. Soc, 1935, 1285. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradshaw B and Bonjoch J, Synlett, 2012, 337. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCullough JE, Muller MT, Howells AJ, Maxwell A, O’Sullivan J, Summerill RS, Parker WL, Wells JS, Bonner DP and Fernandes PB, J. Antibiot, 1993, 46, 526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiang AX, Watson DA, Ling T and Theodorakis EA, J. Org. Chem, 1998, 63, 6774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagiwara H and Uda H, J. Org. Chem, 1988, 53, 2308. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takahashi S, Kusumi T and Kakisawa H, Chem. Lett, 1979, 515. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawada S-Z, Yamashita Y, Uosaki Y, Gomi K, Iwasaki T, Takiguchi T and Nakano H, J. Antibiot, 1992, 45, 1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ling T, Rivas F and Theodorakis EA, Tetrahedron Lett, 2002, 43, 9019. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X, Zhao L, Liu C, Qi J, Zhao P, Liu Z, Li C, Hu Y, Yin X, Liu X, Liao Z, Zhang L and Xia X, Front. Microbiol, 2020, 10, 2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shionozaki N, Yamaguchi T, Kitano H, Tomizawa M, Makino K and Uchiro H, Tetrahedron Lett, 2012, 53, 5167. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicolaou KC, Shi L, Lu M, Pattanayak MR, Shah AA, Ioannidou HA and Lamani M, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2014, 53, 10970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turos E, Audia JE and Danishefsky SJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1989, 111, 8231. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Danishefsky SJ, Funk RL and Kerwin JF Jr, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1980, 102, 6889. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuchida T, Sawa R, Iinuma H, Nishida C, Kinoshita N, Takahashi Y, Naganawa H, Sawa T, Hamada M and Takeuchi T, J. Antibiot, 1994, 47, 386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Warrington JM and Barriault L, Org. Lett, 2005, 7, 4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tatsuta K, Suzuki Y, Furuyama A and Ikegami H, Tetrahedron Lett, 2006, 47, 3595. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan M, Lo JC, Edwards JT and Baran PS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 12692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wertjes WC, Southgate EH and Sarlah D, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2018, 47, 7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans DA, Bartroli J and Shih TL, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1981, 103, 2127. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oppolzer W, Pure Appl. Chem, 1990, 62, 1241. [Google Scholar]