Abstract

Abuse and neglect among older adults impact everyone and are recognized internationally as significant and growing public health issues. A systematic review of reviews was conducted to identify effective strategies and approaches for preventing abuse and neglect among older adults. Eligible reviews were systematic or meta-analyses; focused on the older population as reported in the publications; reviewed prevention interventions; included relevant violence and abuse outcomes; written in English; and published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2000 and May 2020. Eleven unique reviews (12 publications) met the eligibility criteria, including one meta-analysis. Included reviews mainly focused on general abuse directed toward older adults; and educational interventions for professional and paraprofessional caregivers, multidisciplinary teams of health care and legal professionals, and families. Interventions were implemented in a variety of community and institutional settings and addressed primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. The reviews indicated weak or insufficient evidence of effectiveness in preventing or reducing abuse, yet several promising practices were identified. Future research is needed to evaluate emerging and promising strategies and approaches to prevent abuse among older adults. Effective interventions are also needed to prevent or reduce abuse and neglect among older adults.

Keywords: older people, elder abuse and neglect, systematic review, evidence base, prevention

Introduction

Wolf (1997) published a seminal review article in 1997 exploring the state of the science on the abuse and neglect of older adults in community settings. Results of this review demonstrated research on the effectiveness of prevention interventions was chiefly limited to quasi-experimental studies and program evaluations “… with small numbers of clients and produced ambiguous results” (p. 181). Nearly a quarter century later, abuse and neglect among older adults continue to be recognized as a significant and growing public health issue worldwide. Leading researchers in the field continue to emphasize the imperative to develop, evaluate and scale-up potentially effective prevention intervention strategies and approaches to reduce or prevent elder abuse (Connolly et al., 2014; Rosen, Elman et al., 2019; Rosen, Makaroun et al., 2019; Van Den Bruele et al., 2019). To inform the field, findings of several published systematic reviews of prevention strategies and approaches can be synthesized to identify the best available evidence, inform promising prevention practices ready for more rigorous evaluation, and uncover research gaps.

Both the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2018) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a; Hall et al., 2016) define abuse directed at older adults aged 60 years and older as an intentional single or repeated act, or failure to act, by a person in a relationship with an expectation of trust. These acts cause or create a risk of harm or distress to the older person. Abuse among older adults includes acts of commission and omission, and the five widely recognized forms of abuse include emotional or psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial abuse or exploitation, and neglect or abandonment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a; Dong, 2015; Hall et al., 2016; Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; World Health Organization, 2018). According to the World Health Organization (2018), nearly 1 in 6 people aged 60 years and older experience some form of abuse in community-based settings. Further, abuse among older adults is quite prevalent in institutional settings and often leads to serious physical injuries and long-term psychological consequences (World Health Organization, 2018). As populations continue to age worldwide over the next several decades, abuse and neglect among older adults are predicted to increase exponentially (Mohd Mydin et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2018).

Studies report high rates of abuse and neglect among older adults. A study based on data from 52 studies conducted in 28 countries, including 12 low-and middle-income countries, reported nearly 16% of persons aged 60 years and older reported being subjected to some form of abuse over the past year in community settings (Yon et al., 2017). In the U.S., published prevalence estimates of abuse among older adults were a bit lower (range 4.6% to 10%; Acierno et al., 2010; Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; Laumann et al., 2008), and a recent study examining 15-year trends in nonfatal assaults and homicides among U.S. adults aged 60 years and older from 2002 to 2016 found significant increases in estimated nonfatal assault rates among older men (75.4% from 2002 to 2016) and women (35.4% from 2007 to 2016), and an increase in the estimated homicide rate for older men (7.1% from 2010 to 2016) (Logan et al., 2019). The aforementioned statistics are likely to be underestimated due to limited reporting by abuse victims to authorities, surveys do not always represent abuse within relationships of trust, and reliance on self-reports of mistreatment in surveys and other measures (Yon et al., 2017; Young, 2014). The majority (58%) of perpetrators of violence against older adults had a familial relationship or acquaintanceship with the victim (Rosen et al., 2017).

Several studies have identified demographic characteristics and risk and protective factors of abuse and neglect among older adults to inform the development of prevention strategies and approaches. For instance, older women are more likely than men to report abuse (Laumann et al., 2008), and risk factors for victimization occur across the social ecology, including factors related to the older person (e.g., cognitive impairment; behavioral, functional, or psychological impairment; poor physical health; prior trauma or abuse); their relationships (e.g., shared living environment with a spouse, adult children, or other caretakers; family disharmony with poor relationships); and their environments (e.g., social isolation and lack of social supports; low income or wealth; cohabitating due to economic hardship (Acierno et al., 2010; Johannesen & LoGuidice, 2013; Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; Wang et al., 2015)). Known risk factors for perpetration include, but are not limited to, emotional or financial dependence on the older adult (including a spouse and adult children), misuse of drugs or alcohol, stress, and use of ineffective coping strategies, history of trouble with the police, lack of social support, lack of training on caring for an older adult, and other mental or physical health problems (Anetzberger, 2005; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a; Lachs & Pillemer, 2015). Although protective factors for abuse among older adults have not been extensively studied, previous studies have suggested possible protective factors include availability of social supports and community-based resources; services offered to older populations and their caregivers; high levels of community cohesion; and greater collective efficacy to support older adults (Acierno, Hernandez-Tejada, Anetzberger, Loew & Muzzy, 2017; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a; Wilkins et al., 2014).

Strategies are needed to prevent older adult abuse and neglect from occurring in the first place. Fortunately, several systematic reviews seeking to identify effective strategies and approaches for preventing violence directed toward older adults have been published over the past two decades. The aim of this systematic review of reviews is to synthesize the best available evidence on the effectiveness of programs, policies, and practices to reduce and prevent abuse and neglect of community-dwelling older adults, and to identify gaps in the literature.

Methods

Search strategy & inclusion and exclusion criteria

A comprehensive search was initially conducted in September 2018 and updated in May 2020 to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses that sought to evaluate strategies and approaches to prevent abuse and neglect among older adults. Both searches were conducted in consultation with a specialist from the CDC Library. The search included the following electronic databases: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and Scopus (see Appendix A). The keyword search included “elder” with the following words: abuse, maltreatment, neglect, and mistreatment AND review, meta-analysis, or metaanalysis. The top journals identified from the comprehensive searches were the Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, the Journal of Adult Protection, and Trauma, Violence, and Abuse.

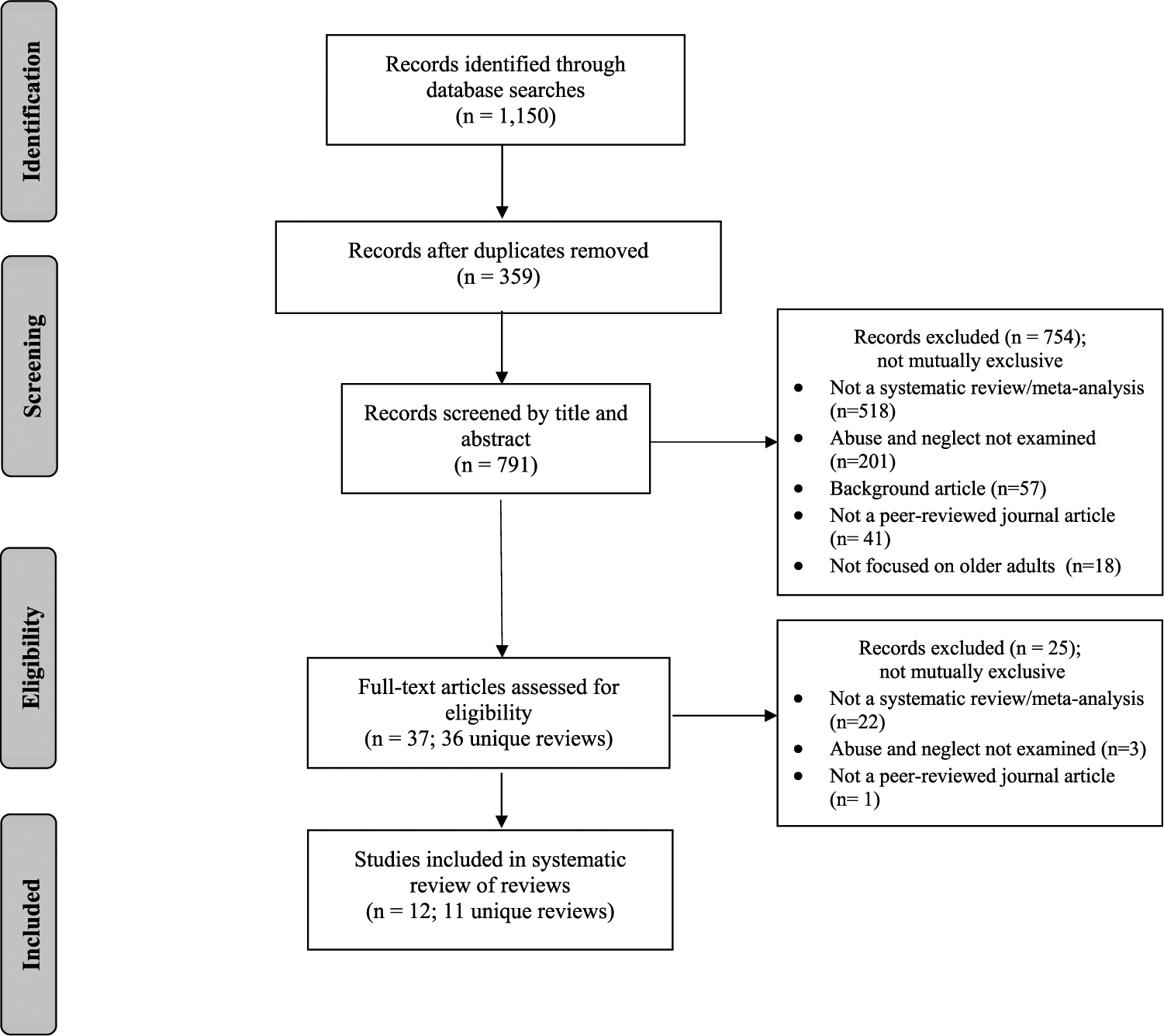

Eligible studies included systematic reviews or meta-analyses; focused on the older population as reported by the authors (typically age 60 years and older); reviewed prevention interventions; included relevant abuse and neglect outcomes (e.g., physical, sexual, and emotional/psychological violence; neglect; and financial exploitation); written in English; and published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2000 and May 2020. We excluded reviews that were not systematic (e.g., critical reviews, narrative reviews, scoping reviews); meta-reviews; and primary research studies of any methodology. This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Systematic review flow diagram: interventions to prevent or stop abuse and neglect among older adults.1

The systematic searches yielded 1,150 records (see Figure 1). Once 359 duplicates were removed, 791 titles and abstracts were screened using Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016; see: www.rayyan.qcri.org) and Covidence (see: https://www.covidence.org/) systematic review web applications. After reviewing the title and abstracts for the inclusion criteria, 754 records were excluded for various reasons listed in Figure 1 (e.g., not a systematic review/meta-analysis, not a peer-reviewed journal article, not focused on older adults). This resulted in 36 unique reviews reported in 37 articles. After reviewing these 37 articles, 25 were excluded (not a systematic review/meta-analysis, abuse, and neglect not examined, and not a peer-reviewed journal article). This resulted in 12 full-text articles reporting on 11 unique reviews, which were included in this review (Alt et al., 2011; Ayalon et al., 2016; Baker et al., 2016, 2017; Day et al., 2017; Fearing et al., 2017; Hirst et al., 2016; Mohd Mydin et al., 2019; Moore & Browne, 2017; Ploeg et al., 2009; Rosen, Elman et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2015).

Data extraction and analysis

A data extraction coding tool was created and pilot tested among the four study coauthors (K.M., C.G., F.A., and J.H.). Each published review was coded by independent coder pairs using the final coding tool (available from the first author). If discrepancies or inclusion and exclusion criteria were straightforward, coder pairs discussed until agreement was reached. The coding tool captured for each published review: study location (U.S. or international); number of studies; type of review (systematic review and/or meta-analysis); focus of the systematic review and/or meta-analysis; and target population. The coding tool also captured characteristics of the studies included in the review; including setting(s); study type (randomized control trial, non-randomized control trial, pre-post); strategies (i.e., educational, psychoeducational, motivational interviewing, family-based, clinician/provider, and other [e.g., case management, legal services, social support]); and outcomes (e.g., emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial abuse/exploitation, neglect, restraint, and other [e.g., abandonment, medical abuse, resident-to-resident abuse/aggression]).

Quality assessment of reviews

To assess the quality of the reviews, the Quality Assessment Tool for Reviews guided coding (Micucci et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2005). This tool was used in prior published review of reviews, and comprises seven questions coded as “yes,” “no,” or “unknown/undetermined.” Based on the coding, each review was rated as strong (total score 6–7), moderate (total score 4–5), or weak (total score 3 or less; Micucci et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2005). The seven questions asked about search strategy, comprehensiveness of the search, relevant criteria (i.e., participants, interventions, outcome, and design), strengths, weaknesses, integrating findings beyond describing or listing the main study results, and making sure the reported data are adequate to support the review’s conclusions. In addition, assessing the inclusion of the following criteria (a minimum of 3/6): study design, study sample/population, confounders, intervention, outcome measures, and follow-up. Similar to the data extraction coding tool, each published review was independently coded by two study authors using the Quality Assessment Tool for Reviews. Discrepancies were discussed until an agreement was reached.

Results

Intervention characteristics

The 11 systematic reviews were published between 2009 and 2019 and included evaluations of interventions and programs implemented in the U.S. and internationally (e.g., Australia, Canada, Germany, Iran, Israel, Spain, Taiwan, the United Kingdom). Among the reviews that reported the years study data were collected, 1982 was the earliest year of data collection and the most recent year of data collection was 2017. The number of studies included in the reviews ranged from 6 to 116, with 187 total studies included across the 11 reviews. Eight of the eleven reviews were published between 2016 and 2019, but there was little overlap between the studies included across the nine reviews. One study was included in six reviews, two studies in five reviews, and five in four reviews. The remaining studies were included in only one (149 studies), two (16 studies), or three (14 studies) reviews.

All reviews used a systematic search strategy (Alt et al., 2011; Ayalon et al., 2016; Baker et al., 2016, 2017; Day et al., 2017; Fearing et al., 2017; Hirst et al., 2016; Mohd Mydin et al., 2019; Moore & Browne, 2017; Ploeg et al., 2009; Rosen, Elman et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2015), and one included a meta-analysis of intervention effectiveness (Ayalon et al., 2016). One review (Hirst et al., 2016) summarized the effects of two types of interventions reported separately in Table 1: educational interventions addressing abuse and neglect, and interventions involving prevention and health promotion strategies. Moore and Browne (2017) reviewed the effects of 28 evidence-based practices and 22 best practices. In addition, Mohd Mydin et al. (2019) reviewed three randomized controlled trials and 10 observational studies. Randomized controlled trials (e.g., randomized parallel groups or stepped-wedge designs) were included in all but two reviews (Moore & Browne, 2017; Wang et al., 2015). One review included studies that had not undergone a rigorous evaluation (Rosen, Elman, et al., 2019). Consistent with our inclusion criteria, all reviews focused on abuse of older adults in general. In addition, all of the reviews included educational interventions for professional caregivers, health-care settings and families (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Eleven Systematic Reviews to Prevent or Stop Abuse and Neglect among Older Adults.

| Author (year) | Number of studies included | aType of Review | Focus of Systematic Review/ Meta-Analysis | Setting | bStudy Type | cStrategies | dOutcomes | eQuality Rating (Total Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ploeg et al. (2009) | 8 | SR | Abuse of persons 60 years and older | Community-based, hospital, mental health centers, social work aging services/social services, state abuse among older adults demonstration programs | RCT, pre-post | E, P, F, C, O | E, P, S, F, N, O | Strong (7) |

| Alt et al. (2011) | 14 | SR | Educational programs for allied health professionals, aging service providers and first responders, nurses, care assistants and social workers | Community-based, nursing home, hospital | RCT, non-RCT, pre-post, survey | E, C, O | O | Strong (7) |

| Wang et al. (2015) | 10 | SR | General elder population | Community-based, nursing home, forensic centers/Adult Protective Services, dementia clinic | non-RCT, pre-post | E, P, O | E, P, F, N, R, O | Strong (7) |

| Ayalon et al. (2016) | 24 | SR & MA | General elder population | Community-based, nursing home, hospital, university setting, long-term care facility, group-dwelling units for people with dementia, psychogeriatric wards, municipalities | RCT, non-RCT, pre-post, group comparison | E, P, Ml, F, C, O | E, P, N, R | Strong (7) |

| Baker et al. (2016) & Baker et al. (2017) | 7 | SR | Reduce or prevent abuse among older adults in their home, in organizational or institutional and community settings | Community-based, nursing home, university setting, home health care organizations, state government department for the aging, neurological outpatient dementia service, housing projects, institution | RCT, controlled before- and-after | E, P, O | E, N, O | Strong (7) |

| fHirst et al. (2016) | 23 Education Needed to Effectively Address Abuse & Neglect of Older Adults | SR | Nurses and health care providers | Nursing home, long-term care facility | RCT, mixed methods, cross-sectional | E, C | O | Moderate (5) |

| 10 Prevention & Health Promotion Strategies | SR | Older adult, the abusive caregiver, and the public | Faith-based organization | non-RCT, cross-sectional | E, O | E, O | ||

| Day et al. (2017) | 8 | SR | Elder abuse victims (60 years and older) | Community-based, university setting, long-term care facility, dental office, in-home assessment of Adult Protective Services, Forensic Center | RCT, non-RCT, pre-post, qualitative methods, referrals to program | E, P, F, C, O | E, P, S, F, N, O | Strong (6) |

| Fearing et al. (2017) | 9 | SR | Community-based older adults at-risk for abuse (dementia patients) | Community-based, clinical | RCT, non-RCT, pre-post, mixed method, surveys, interviews, observations, retrospective secondary data analysis/national e-survey | E, P, Ml, O | E, P, F, N, O | Strong (7) |

| gMoore and Browne (2017) | 28 Evidence-Based Practices | SR | Perpetrators, professionals, people who care for older persons, education for older adults | Community-based, hospital, long-term care facility, community mental health centers | RCT, non-RCT, pre-post, non-experimental | E, P, F, C, O | E, P, S, F, N, O | Moderate (4) |

| 22 Best Practices | SR | Professionals (Adult Protective Service workers, nurses, case managers) | Long-term care facility | Non-experimental | E, O | O | ||

| Mohd Mydin et al. (2019)h | 13 | SR | Elders in primary health-care providers (physicians, nurses, medical assistants, allied health, midwife, pharmacist, dentist, social workers) | Community-based, nursing home, hospital, university setting, physician offices | RCT, non-RCT, pre-post, case control, cohort & cross-sectional | E, C | F,0 | Strong (7) |

| Rosen, Elman, et al. (2019) | 116 | SR | Abuse and neglect programs for older adults in acute-care hospitals and low resource environments | Community-based, nursing home, hospital, university setting, law enforcement/legal/ district attorney’s office/court, victim’s home/telephone, Adult Protective Service | RCT, non-RCT, pre-post, case series, mixed methods, nonequivalent comparison group, & cross-sectional | E, P, F, C, O | E, P, S, F, N | Strong (6) |

SR = Systematic Review; MA = Meta-Analysis

RCT = Randomized control trial

E = Educational; P = Psychoeducational; MI = Motivational interviewing; F = Family based; C = Clinician/provider; O = Other (e.g., case management, legal services, social support)

E = Emotional/Psychological abuse; P = Physical abuse; S = Sexual abuse; F = Financial abuse/Exploitation; N = Neglect; R = Restraint; O = Other (e.g., abandonment, medical abuse, resident-to-resident abuse/aggression)

The Quality Assessment Tool for Reviews was used to assess the quality of each review (Micucci et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2005). This tool comprises seven questions coded as “yes,” “no,” or “unknown/undetermined.” Based on the coding, each review was rated as strong (total score 6–7), moderate (total score 4–5) or weak (total score 3 or less)

The studies included are not mutually exclusive. An additional 58 studies did not have outcome data and are not reported.

An additional 17 emerging/innovative practices did not have outcome data and are not reported.

The 13 studies include 3 randomized controlled trials and 10 observational studies.

Interventions were implemented in various locations. All reviews included interventions implemented in community-based settings, eight in nursing homes, seven in hospitals, five in a university-based setting, and four in long-term care facilities. Additional settings included faith-based organizations, social services, forensic centers, physician offices, and collaboration with Adult Protective Service (APS) programs. Most reviews included educational or family-based interventions, and most included studies reporting outcomes involving emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, neglect, and financial abuse/exploitation. Only four reviews included studies reporting sexual abuse (Day et al., 2017; Moore & Browne, 2017; Ploeg et al., 2009; Rosen, Elman, et al., 2019). According to the quality rating scale, nine reviews had strong quality (Alt et al., 2011; Ayalon et al., 2016; Baker et al., 2016, 2017; Day et al., 2017; Fearing et al., 2017; Mohd Mydin et al., 2019; Ploeg et al., 2009; Rosen, Elman, et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2015) and two had moderate quality (Hirst et al., 2016; Moore & Browne, 2017); none received a weak quality rating.

Review findings

The reviews reported few statistically significant intervention effects for abuse and neglect outcomes, and review authors consistently did not identify specific evidence-based interventions for wide-spread implementation in Table 2. However, the meta-analysis reported by Ayalon et al. (2016) found that the pooled effect of nine cluster RCTs targeting restraint use by long-term paid caregivers significantly reduced use of restraints on older patients with dementia (standardized mean difference = −0.24; 95% confidence interval = −0.38 to −0.09). There was mixed or insufficient evidence of intervention effectiveness in preventing or reducing abuse and neglect outcomes in Table 2; however, promising prevention practices were identified.

Table 2.

Overview, Findings, and Author Conclusions/Implications from Eleven Systematic Reviews.

| Author (year) | Overview, Findings, and Author Conclusions/Implications |

|---|---|

| Ploeg et al. (2009) | Overview: Systematic review of 8 studies focused on abused older adults, perpetrators, caregivers that were at risk of abusing older family member, and healthcare professionals who provide care to abused older adults. Study settings included the community and healthcare. Study outcomes included emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial abuse/exploitation, neglect, and self-neglect. |

| Findings: Evidence is insufficient to support interventions focused on clients, perpetrators, or health care professionals. | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: High quality research on effectiveness of interventions to address elder abuse are limited. Therefore, research focusing on implementing more rigorous evaluations (e.g., randomized control trials or experimental designs) at all levels of the socioecological model (individual, family, community, and system-wide) are needed. | |

| Alt et al. (2011) | Overview: Systematic review based on 14 studies describing 22 interventions. The interventions focused on educating health professionals and paraprofessionals to recognize and report abuse and neglect. Study settings included the community, nursing home, and healthcare. Study outcomes included increasing awareness, collaboration, and case-findings. |

| Findings: Educational programs to improve recognition and reporting of abuse and neglect among older adults are limited. | |

| Elder abuse prevention (10 studies) | |

| Physicians and hospital staff (four studies): Three studies describing six education programs reported statistically significant findings for improved self-assessment of geriatrics ability (e.g., capacity evaluation, home environment, and abuse). Interventions resulted in improvements in “knowledge and perceived ability to manage and appropriately refer elder abuse cases.” | |

| Allied health professionals, aging service providers, and first responders (three studies): Three studies focused on educational sessions to prevent abuse and neglect among older adults. Two studies showed improvements in knowledge-based questions and referrals from Alzheimer Association to Adult Protective Services. Mixed audiences (nurses, care assistants, and social workers) (three studies): These studies focused on education and training sessions to raise awareness and educate on abuse among older adults. Two studies showed statistically significant increases on knowledge-based and management questions after exposure to interactive educational interventions. | |

| Broader training programs (4 studies) | |

| Experiential domestic violence training program (one study): One study focused on physician volunteers participating in workshops focused on abuse among older adults as well as other forms of abuse (i.e., intimate partner violence and child abuse). The program resulted in significant increases in routine screening frequency and reporting case management as well as perceived knowledge and skills. | |

| Training program for dental professionals (two studies): Two programs focused on PANDA (Prevent Abuse and Neglect through Dental Awareness) for dental professionals, which included family violence across the lifespan. These training programs showed statistically significant improvements in knowledge-based questions, including awareness of regulating and reporting abuse among older adults.Note: Information is only included for the studies with evaluation data. Data not reported for one study. | |

| Author conclusions/implications Several published studies evaluated educational interventions for health professionals and paraprofessionals. While most interventions aimed to increase participant awareness and knowledge of abuse among older adults, studies need to focus on using the CIPP (Context, Input, Process, and Product) evaluation model for adequate reporting for program replication. Reporting may include implementation barriers, program outcomes, and attendance. | |

| Wang et al. (2015) | Overview: Systematic review based on 10 studies of interventions for management of elder abuse in a clinical setting. Study outcomes included emotional/ psychological abuse, physical abuse, financial abuse/exploitation, neglect, restraint, resident-to-resident abuse, and other (e.g., social support, self-esteem, anger management, coping). |

| Findings: There was insufficient evidence for the authors to recommend interventions or screening for abuse among older adults. Although multidisciplinary teams (health care providers, nurses, mental health care providers, protective services and justice system professionals) show the most promise for preventing abuse among older adults, there is only one study that used a multidisciplinary team with a statistically significant abuse-related outcome (i.e., increased rates of prosecution for financial abuse; Navarro et al., 2013), and it only addressed financial abuse. | |

| Author conclusions/implications: There should be a focus on the efficacy of interventions, examination of risk factors for various types of abuse among older adults, description of outcome measures that work, and conduct testing the efficacy of interventions that are feasible. According to the authors: “The best intervention strategy at this time appears to be education targeted at increasing awareness of elder abuse among health care professionals, analogous to the incorporation of child abuse training into the medical school curriculum” (p. 580). | |

| Ayalon et al. (2016) | Overview: Systematic review of 24 intervention studies designed to delay or stop abuse among older adults. Studies were conducted in the community, healthcare, nursing homes, universities, long-term care facilities, psychogeriatric wards, municipalities, and group-dwelling units for people with dementia. Study outcomes included emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, neglect, and restraint. |

| Findings: Overall, there were mixed effects on abuse outcomes for older adults. | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: “The most effective place to intervene on elder abuse at the present time is by directly targeting physical restraint by long-term care paid carers” (p. 226). Future research should focus on neglect, cognitive status, and home care of older adults as well as public awareness. In addition, there should be a focus on the three categories of interventions (i.e., professionals responsible for preventing or stopping elder maltreatment, older adults who experience elder maltreatment, and caregivers who maltreat). | |

| Baker et al. (2016) & Baker et al. (2017) | Overview: Cochrane systematic review based on 7 intervention studies to prevent the occurrence or reoccurrence of elder abuse. Study settings included organizations, institutions, and homes in high-income countries (e.g., US, United Kingdom, and Taiwan). Study outcomes included emotional/psychological abuse, neglect, restraint, and other (e.g., depression, anxiety, crisis management, suicide, self-esteem). |

| Findings: The results did not provide evidence for preventing the occurrence or reoccurrence of abuse among older adults. | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: Inadequate evidence to assess the effects of elder abuse interventions on occurrence or recurrence of abuse, with some evidence suggesting interventions may change combined measures of anxiety and depression of caregivers. Need to focus on identifying the best strategies and approaches to prevent or reduce abuse among older adults, and to use high-quality trials with adequate statistical power and appropriate study characteristics to determine effectiveness. Strategies and approaches should concentrate on specific policies, legislation, and rehabilitation programs for older persons. The evidence is lacking in these important areas and the field is unable to guide practice and policy to prevent or reduce abuse. | |

| Hirst et al. (2016) | Overview: Systematic review of intervention approaches within healthcare settings that focus on identifying, assessing, and responding to abuse and neglect of older adults; education, prevention and health promotion strategies; and organizational and system-level supports to prevent and respond to abuse and neglect. Study outcomes included emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, financial abuse/exploitation, neglect, restraint, and other (e.g., depression, anxiety, connections with the community). |

| Findings: The results indicated more research is needed to address approaches within healthcare settings. | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: Focus on rigorously evaluating interventions that prevent abuse. More research is needed on the effectiveness of screening to reduce abuse among older adults. Using the social determinants of health framework might be beneficial to prevent abuse and neglect because of the financial and societal factors that play a role in this type of abuse. | |

| Day et al. (2017) | Overview: Systematic review of 8 studies focused on risk factors that tarqet abuse amonq adults amonq older adults that have experienced abuse. Study settinqs included community-based, universities, long-term care facilities, elder abuse centers, dental professional office. Study outcomes included emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial/exploitation, neglect, resident-to-resident abuse, and other nonviolent outcomes (pain/sensory impairment, guardianship actions). |

| Findings: The results showed significant intervention effects. | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: Future research should focus on usinq an experimental or quasi-experimental desiqn, have clear and specific outcomes of interest, and testing for reliability. Focused attention should be placed on creating comprehensive and multimodal interventions that examine various risk factors. | |

| Fearing et al. (2017) | Overview: Systematic review of 9 studies focused on community-based interventions to reduce abuse and neglect among older adults or perpetrators living in noninstitutional settings. These studies included psychological interventions for dementia family caregivers, multidisciplinary teams, Forensic Center, and interventions for caregivers. Study outcomes included emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, financial abuse/exploitation, neglect, and other nonviolent outcomes (e.g., anxiety and depression, social support, coping). |

| Findings: The results showed that overall, there were mixed effects for community-based interventions. | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: Future research should focus on elder neglect specifically and include more rigorous study designs (e.g., randomized control trial, quasi-experimental, mixed-methods designs). It is also important to have larger same sizes, incorporate theory, and examine individual and broader systemic factors. | |

| Moore and Browne (2017) | Overview: Systematic review of 67 studies focused on perpetrators, professionals and people who care for older persons, and the ‘the community.’ There were 28 evidence-based practices, 22 best practices, and 17 emerging/innovative practices. Study settings included the community, healthcare, universities, and long-term care facilities. Study outcomes included emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial abuse/exploitation, neglect, resident-to-resident, and reports of abuse to police. |

| Findings: The results showed that these evidence-based and best practices resulted in mixed effects. | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: There needs to be a focus on abuse and neglect perpetrators (e.g., caregivers), more research on elder maltreatment and working with the older population after abuse has occurred. An important component of future interventions will be to focus on cultural diversity and informing the research field about programs through dissemination and translation efforts. | |

| Mohd Mydin et al. (2019) | Overview: Systematic review of 13 studies (three randomized controlled trials and 10 observational studies) focused on educational interventions for primary health-care providers’ (physicians, nurses, medical assistants, allied health professionals, midwives, pharmacists, dentists, and social workers) knowledge, identification, and management of abuse and neglect among older adults. Study settings included the community, nursing home, hospital, university, and physician offices. Study outcomes included financial abuse/exploitation, knowledge, attitude, comfort levels, reporting of elder abuse, and screening of violence. |

| Findings: The results showed increases in primary healthcare service providers’ knowledge and awareness of abuse, but didactic educational training alone was insufficient in impacting elder abuse behaviors. | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: There needs to be a focus on randomized controlled trials that are of higher quality, especially in countries that are of low- and middle-income. This also includes having a measurement tool that is validated and standardized and measuring practices and attitudes. A diverse array of education interventions should include a variety of delivery methods (e.g., face-to-face teaching, role-play) and be problem-based. In addition, there should be a focus on increasing communication skills, providing training on dealing with abuse and neglect among older adults, and not including other types of interpersonal violence. | |

| Rosen, Elman, et al. (2019) | Overview: Systematic review of 116 studies focused on abuse and neglect programs for older adults in acute-care hospitals and low resource environments. Study settings included the community, nursing home, hospital, university, law enforcement/legal/district attorney’s office/court, victim’s home/telephone, and Adult Protective Service. Study outcomes included emotional/psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial abuse/exploitation, and neglect. |

| Findings: The results were limited and showed mixed effects. Only 57% of the programs evaluated the program for impact and of those, two and six programs respectively used higher-tier and middle-tier quality study designs (based on a specific set of limitations). | |

| |

| Author conclusions/implications: There needs to be a focus on reducing the healthcare and other costs that are associated with abuse and neglect among older adults due to programs that might be resource-intensive. Researchers should consider incorporating programs in acute care hospitals. In addition, it may be beneficial to work with Adult Protective Services (APS). APS will have the ability to fulfill the umbrella of prevention, identification, and intervention. The field still needs to identify the appropriate abuse and neglect outcomes to measure and the best way to measure program success. |

Some reviews reported education-based interventions were associated with improvements in knowledge of abuse among older adults, recognition and reports of abuse, and prevention of resident-to-resident abuse (e.g., Alt et al., 2011; Day et al., 2017; Ploeg et al., 2009). These reviews explored the effectiveness of educational interventions on health-care services providers’ knowledge, identification, and management of abuse and neglect among older adults. The authors found an increase in primary healthcare service providers’ knowledge and awareness of abuse, but didactic educational training alone was insufficient in impacting elder abuse behaviors (Mohd Mydin et al., 2019).

The included reviews also identified gaps in the literature regarding strategies and approaches that may reduce abuse directed toward older adults, particularly strategies that address risk factors for caregivers and other community and societal-level risks. Caregivers are more likely to experience work-related impairments and mental health symptoms, including anxiety and depression, resulting from the time and effort needed to care for an older family member (Hopps et al., 2017). To address these and other risk factors, one potential prevention strategy with evidence of preventing multiple forms of violence involves strengthening economic supports for families (Fortson et al., 2016; Niolon et al., 2017; Stone et al., 2017). Moreover, studies suggest policies and practices that improve household financial security and work-family supports may reduce rates of abuse among older adults (Dong, 2012). Knickman and Snell (2002) suggest social and policy changes are needed to address the financial and social service burdens of growing numbers of older adults. Other policy approaches that might have an impact on abuse against older adults at the community or societal levels involve increased subsidies through tax credits and policies created to prevent other forms of violence (Dong, 2012; Knickman & Snell, 2002). For example, the California Earned Income Tax Credit in 2019 was increased from $500 USD to $2,000 USD, comparable to the 2018 child tax credit, to include older adult dependents in addition to children (California Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC), 2020; Shurtz, 2018). Future researchers are encouraged to investigate the effectiveness of community- and societal-level strategies to prevent abuse and neglect among older adults.

Discussion

Limitations and strengths of this review of reviews

This systematic review of reviews is the first paper to synthesize findings reported in several published reviews on the effectiveness of strategies and approaches to prevent abuse directed toward older adults. There are challenges limiting the utility of reviews on this topic, including limitations inherent in the primary studies, limitations of the published systematic reviews, and limitations in our review of reviews study procedures. A recognized limitation of the primary studies involves the use of self-report measures to assess knowledge, attitude, and behavior change. Evaluations of prevention strategies commonly rely on self-reported behavioral data, and studies use validated measures to assess outcomes. However, objective measures of abuse and neglect outcomes have many challenges including underreporting to law enforcement, institutions, and other officials empowered to launch investigations (Wang et al., 2015). Additional limitations include non-rigorous study designs and study methods, variations in definitions of elder abuse and neglect, and variations in focus on family and institutional caregivers and community-dwelling and institutionalized older adults.

A general criticism of systematic reviews of reviews is that the included reviews include the same primary studies. However, for this review, only 20% of the individual studies were included in two or more of the reviews. This low level of overlap is likely due to the 11 reviews varying in study aims, research questions, and guiding frameworks, thus influencing the inclusion criteria for primary studies. For example, Alt et al. (2011) and Mohd Mydin et al. (2019) reviewed the effectiveness of educational programs to improve identification, reporting, and management of abuse and neglect among older adults, while Moore and Browne (2017) reviewed emerging innovations, best practices, and evidence-based programs for preventing abuse among older adults. Another limitation involves the possibility that relevant primary studies were not included in a published review and not considered in this review. Our review findings include 149 unique individual studies, enabling a synthesis of implementation issues across a variety of settings and populations. Furthermore, the primary studies included in the published reviews were conducted in geographically diverse settings thereby enhancing the generalizability of review findings, and the findings of our review of reviews. Included reviews also varied in study quality, with nine of the eleven included reviews rated as having strong research methods, further enhancing the strength of our synthesized findings. Finally, due to a paucity of publications reporting intervention effectiveness using rigorous study methods, only one published review meta-analyzed an abuse outcome (i.e., use of restraints; Ayalon et al., 2016). Therefore, it is not possible to quantitatively synthesize findings across the 11 reviews.

In accordance with standard review procedures, we ensured our study search process and selection criteria had the greatest rigor possible; and data extraction and review quality assessment procedures were performed by two independent coders. A high rate of agreement occurred between coders indicating consistency in review methods. Despite our extensive database searches, it is possible we may have missed relevant reviews, including unpublished reports and those not reported in the English language. Therefore, our results may not be representative of non-English language studies, the unpublished literature, or literature published in non-peer-reviewed sources. Only information reported in the published reviews was included; we did not contact the authors of the published reviews or primary studies for additional information or to clarify information reported in their publications. While there was consensus across reviews regarding minimum age of older adults, the definition of “elders” varied across the primary studies and reviews. For example, several primary studies used the term “elder” without specifying ages, while others used a minimum age (e.g., 55, 60, or 65 years and older) for inclusion (Baker et al., 2016; Moore & Browne, 2017). Finally, our unit of analysis was the reviews themselves rather than the individual primary studies. This review is reliant on how comprehensively the included reviews extracted information on program implementation from the primary studies.

Despite these limitations, this systematic review of reviews has several strengths. The review provides a comprehensive summary of 11 unique reviews published since 2000. All of the included reviews involve evidence of prevention interventions from international settings, which confirms the consistent finding that there are a lack of rigorous evaluation studies designed to test the effectiveness of prevention strategies and approaches on abuse and neglect outcomes. After decades of research, this appears to still hold true. Moreover, this review highlights how addressing key limitations can help advance the field.

Research gaps and future directions

Future research is needed to develop strategies and approaches, in conjunction with more rigorous evaluation methods, to prevent abuse and neglect among older adults. This is increasingly important as the population of older adults continues to increase in the U.S. and worldwide. Few studies in the literature address protective factors for abuse and neglect (e.g., social support, community cohesion, community-based resources, and services). However, reported risk and protective factors are congruent with other forms of violence (Wilkins et al., 2014). A future direction for research may be to highlight the connections between violence types and interventions on the root causes of violence across the life course as opposed to focusing on more siloed outcomes (Wang & Dong, 2019; Wilkins et al., 2014). It is also important for future research to identify and integrate modifiable risk and protective factors into prevention strategies and approaches (National Research Council, 2003).

Our review findings highlight a need for future research to evaluate emerging innovative strategies and approaches (Moore & Browne, 2017), and to develop and rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of prevention interventions at the community and societal level (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2014). Mohd Mydin et al. (2019) systematic review points to a need for outer layer strategies and approaches of the socioecological model, including policies and programs that support entire communities. In addition, Wang et al. (2015) encourage the field to determine what works to prevent and stop the abuse of older adults by implementing community-level (e.g., cultural norms) and societal-level (e.g., policies, social norms) strategies. An expert panel convened by the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research concluded that future interventions should target the perpetrator-victim dyad, screen persons at risk for elder abuse perpetration, involve multi-disciplinary and multi-dimensional approaches to prevention, and build upon existing programs including senior-targeted events, shelters, and helplines (National Institutes of Health, 2016).

It is vital to understand and examine implications related to prevention efforts. The authors of the eleven systematic reviews describe a variety of future implications in Table 2. These include the implementation of more rigorous study designs (e.g., randomized controlled trials, mixed methods; Baker et al., 2016, 2017; Day et al., 2017; Fearing et al., 2017; Hirst et al., 2016; Mohd Mydin et al., 2019; Ploeg et al., 2009); increasing the sample size, public awareness, and funding of prevention studies, and health care costs to older adults that have experienced abuse and neglect (Ayalon et al., 2016; Fearing et al., 2017; Rosen, Elman et al., 2019); testing the reliability and validity of commonly used surveys and assessments (Day et al., 2017; Mohd Mydin et al., 2019); incorporating behavior change theory in intervention development (Fearing et al., 2017); incorporating training and increasing communication skills (Mohd Mydin et al., 2019); working with APS (Rosen, Elman et al., 2019); and focusing on specific policies (e.g., housing, transportation), legislation (e.g., mandatory reporting, adult protection statutes), and rehabilitation programs (e.g., counseling, legal assistance; Baker et al., 2016, 2017). In addition, two reviews encourage greater cultural diversity and the use of social determinants of health framework to inform prevention approaches (Hirst et al., 2016; Moore & Browne, 2017). Finally, future studies should address adequate reporting of abuse and neglect, implementation issues, and dissemination and translation activities (Alt et al., 2011; Moore & Browne, 2017). Like other forms of violence, abuse and neglect among older adults are preventable (Wilkins et al., 2014). Rosen, Makaroun et al. (2019) acknowledge that despite the significance of abuse and neglect among older adults, the literature does not show an increase in the number of new programs. It is important to recognize that the field holds great promise, and future researchers have an opportunity to incorporate the prevention efforts noted above to prevent and stop abuse and neglect among older adults.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Appendix A. Database and Search Strategy

| Database | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Medline (OVID) 1946- | (Elder* ADJ5 abus*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 maltreat*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 neglect*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 mistreat*) AND (review* OR meta analys? OR metaanalys?).pt,ti. Limit 2000 -; English |

| Embase (OVID) 1996- | (Elder* ADJ5 abus*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 maltreat*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 neglect*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 mistreat*) AND (review* OR meta analys? OR metaanalys?).pt,ti. Limit 2000 -; English |

| PsycInfo (OVID) 1987- | (Elder* ADJ5 abus*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 maltreat*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 neglect*) OR (Elder* ADJ5 mistreat*) AND (review* OR meta analys? OR metaanalys?).ti Limit 2000 -; English |

| CINAHL (Ebsco) | (Elder* N5 abus*) OR (Elder* N5 maltreat*) OR (Elder* N5 neglect*) OR (Elder* N5 mistreat*) AND (PT (review* OR meta analys? OR metaanalys?)) Limit 2000 -; English |

| Cochrane Library | ((Elder* NEAR/5 abus*) OR (Elder* NEAR/5 maltreat*) OR (Elder* NEAR/5 neglect*) OR (Elder* NEAR/5 mistreat*)):ti,ab AND Limit 2000 -; English |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY((Elder* W/5 abus*) OR (Elder* W/5 maltreat*) OR (Elder* W/5 neglect*) OR (Elder* W/5 mistreat*)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(review* OR “meta analys?” OR metaanalys?) AND NOT INDEX(medline) Limit 2000 -; English |

Footnotes

The searches (initial search conducted in September 2018 and updated search conducted in May 2020) were combined in the flow diagram.

References

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, & Kilpatrick DG (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The national elder mistreatment study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 292–297. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada MA, Anetzberger GJ, Loew D, & Muzzy W (2017). The National Elder Mistreatment Study: An 8-year longitudinal study of outcomes. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 29(4), 254–269. 10.1080/08946566.2017.1365031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt KL, Nguyen AL, & Meurer LN (2011). The effectiveness of educational programs to improve recognition and reporting of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 23(3), 213–233. 10.1080/08946566.2011.584046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anetzberger GJ (2005). The reality of elder abuse. Clinical Gerontologist, 28(1/2), 1–−25. 10.1300/J018v28n01_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L, Lev S, Green O, & Nevo U (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions designed to prevent or stop elder maltreatment. Age and Ageing, 45(2), 216–227. 10.1093/ageing/afv193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PR, Francis DP, Hairi NN, Othman S, & Choo WY (2016). Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (8), Art. No.: CD010321, 1–104. 10.1002/14651858.CD010321.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PR, Francis DP, Mohd Hairi NN, Othman S, & Choo WY (2017). Interventions for preventing elder abuse: Applying findings of a new Cochrane review. Age and Ageing, 46(3), 346–348. 10.1093/ageing/afw186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC). (2020). Adults age 65 and older are now eligible for Cal EITC. CalEITC4ME. Retrieved from https://www.caleitc4me.org/older-californians-are-eligible-for-caleitc/ [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019a, May 28). Elder abuse: Definitions. Atlanta, GA: Author. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/definitions.html [Google Scholar]

- Connolly MT, Brandl B, & Breckman R (2014). The elder justice roadmap: A stakeholder initiative to respond to an emerging health, justice, financial and social crisis. National Center on Elder Abuse, US Department of Justice. Retrieved May 20, 2020, from https://www.justice.gov/file/852856/download. [Google Scholar]

- Day A, Boni N, Evert H, & Knight T (2017). An assessment of interventions that target risk factors for elder abuse. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(5), 1532–1541. 10.1111/hsc.12332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XQ (2012). Advancing the field of elder abuse: Future directions and policy implications. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(11), 2151–2156. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04211.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XQ (2015). Elder abuse: Systematic review and implications for practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(6), 1214–1238. 10.1111/jgs.13454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearing G, Sheppard CL, McDonald L, Beaulieu M, & Hitzig SL (2017). A systematic review on community-based interventions for elder abuse and neglect. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 29(2–3), 102–133. 10.1017/S0714980816000209/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortson BL, Klevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, & Alexander SP (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE, Karch DI, & Crosby AE (2016). Elder abuse surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended core data elements for elder abuse surveillance, Version 1.0 National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst SP, Penney T, McNeill S, Boscart VM, Podnieks E, & Sinha SK (2016). Best-practice guideline on the prevention of abuse and neglect of older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging, 35(2), 242–260. 10.1017/S0714980816000209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopps M, Iadeluca L, McDonald M, & Makinson GT (2017). The burden of family caregiving in the United States: Work productivity, health care resource utilization, and mental health among employed adults. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 2017(10), 437–444. 10.2147/JMDH.S135372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesen M, & LoGuidice D (2013). Elder abuse: A systematic review of risk factors in community-dwelling elders. Age and Ageing, 42(3), 292–298. 10.1093/ageing/afs195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickman JR, & Snell EK (2002). The 2030 problem: Caring for aging baby boomers. Health Services Research, 37(4), 849–884. 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.56.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, & Pillemer KA (2015). Elder abuse. The New England Journal of Medicine, 373 (20), 1947–1956. 10.1056/NEJMra1404688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Letsch SA, & Waite LJ (2008). Elder maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. Journal of Gerontology B: Psychological Science and Social Science, 63(4), S248–S254. 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JE, Haileyesus T, Ertl A, Rostad WL, & Herbst JH (2019). Nonfatal assaults and homicides among adults aged ≥ 60 years – United States, 2002–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(13), 297–302. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6813a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micucci S, Thomas H, & Vohra J (2002). The effectiveness of school-based strategies for the primary prevention of obesity and for promoting physical activity and/or nutrition, the major modifiable risk factors for type 2 diabetes: A review of reviews. Ontario, USA: Public Health Research, Education and Development Program. http://old.hamilton.ca/phcs/ephpp/Research/Full-Reviews/Diabetes-Review.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Mydin FH, Yuen CW, & Othman S (2019). The effectiveness of educational intervention in improving primary health-care service providers’ knowledge, identification, and management of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1–17. 10.1177/1524838019889359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ-British Medical Journal, 339(b2535). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Group. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, & Browne C (2017). Emerging innovations, best practices, and evidence-based practices in elder abuse and neglect: A review of recent developments in the field. Journal of Family Violence, 32(4), 383–397. 10.1007/s10896-016-9812-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (2016, February 4). Developing effective elder abuse interventions. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/developing-effective-elder-abuse-interventions/ [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (2003). Elder mistreatment: Abuse, neglect, and exploitation in an aging America. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/10406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro AE, Gassoumis ZD, & Wilber KH (2013). Holding abusers accountable: An elder abuse forensic center increases criminal prosecution of financial exploitation. Gerontologist, 53(2), 303–312. 10.1093/geront/gns075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niolon PH, Kearns M, Dills J, Rambo K, Irving S, Armstead T, & Gilbert L (2017). Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: A technical package of programs, policies, and practices. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, & Elmagarmid A (2016). Rayyan — A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg J, Fear J, Hutchison B, MacMillan H, & Bolan G (2009). A systematic review of interventions for elder abuse. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 21(3), 187–210. 10.1080/08946560902997181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. (2014, July). Preventing and addressing abuse and neglect of older adults: Person-centred, collaborative, system-wide approaches. https://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/Preventing_Abuse_and_Neglect_of_Older_Adults_English_WEB.pdf

- Rosen T, Elman A, Dion S, Delgado D, & Demetres M (2019). Review of programs to combat elder mistreatment: Focus on hospitals and level of resources needed. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67 (6), 1286–1294. National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment Project Team. 10.1111/jgs.15773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Lachs D, Clark S, Bloemen E, Udow E, Varki V, & Yonashiro-Cho J (2017, September). Violence against older adults: Perpetration and mechanisms of geriatric physical assault injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2006–2014. Paper presented at the SAVIR 2017 Conference, Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Makaroun LK, Conwell Y, & Betz M (2019). Violence in older adults: Scope, impact, challenges, and strategies for prevention. Health Affairs, 38(10), 1630–1637. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurtz NE (2018). Long-Term care and the tax code: A feminist perspective on elder care. Journal of Gender and the Law, 20(1), 107. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/gender-journal/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2019/01/GT-GJGL180036.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Stone DM, Holland KM, Bartholow B, Crosby AE, Davis S, & Wilkins N (2017). Preventing suicide: A technical package of policies, programs, and practices. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H, Micucci S, Ciliska D, & Mirza M (2005). Effectiveness of school-based interventions in reducing adolescent risk behaviours: A systematic review of reviews. Ontario, USA: Public Health Research, Education and Development Program. http://old.hamilton.ca/phcs/ephpp/Research/Summary/2005/AdolescentRiskReview.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bruele AB, Dimachk M, & Crandall M (2019). Elder abuse. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 35(1), 103–113. 10.1016/j.cger.2018.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, & Dong X (2019). Life course violence: Child maltreatment, IPV and elder abuse phenotypes in a US Chinese population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(S3), S486–S492. 10.1111/jgs.16096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XM, Brisbin S, Loo T, & Straus S (2015). Elder abuse: An approach to identification, assessment and intervention. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(8), 575–581. 10.1503/cmaj.141329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins N, Tsao B, Hertz M, Davis R, & Klevens J (2014). Connecting the Dots: An overview of the links among multiple forms of violence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Oakland, CA: Prevention Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf RS (1997). Elder abuse and neglect: An update. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 7(2), 177–182. 10.1017/S0959259897000191P [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2018, June 8). Elder abuse. Author. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse [Google Scholar]

- Yon Y, Mikton CR, Gassoumis ZD, & Wilber KH (2017). Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health, 5(2), e147–e156. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LM (2014). Elder physical abuse. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 30(4), 761–768. 10.1016/j.cger.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]