Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate fidelity of delivery of a nurse-led non-pharmacological complex intervention for knee pain.

Setting

Secondary care. Single-centre study.

Study design

Mixed methods study.

Participants

Eighteen adults with chronic knee pain.

Inclusion criteria

Age >40 years, knee pain present for longer than 3 months, knee pain for most days of the previous month, at least moderate pain in two of the five domains of Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index pain scale.

Interventions

Nurse-led non-pharmacological intervention comprising assessment, education, exercise, use of hot/cold treatments, footwear modification, walking aids and weight-loss advice (if required).

Outcome(s)

Primary: fidelity of delivery of intervention, secondary: nurses’ experience of delivering intervention.

Methods

Each intervention session with every participant was video recorded and formed part of fidelity assessment. Fidelity checklists were completed by the research nurse after each session and by an independent researcher, after viewing the video-recordings blinded to nurse ratings. Fidelity scores (%), percentage agreement and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated. Two semi-structured interviews were conducted with the research nurse.

Results

Fourteen participants completed all visits. 62 treatment sessions took place. Nurse self-report and assessor video rating scores for all 62 treatment sessions were included in fidelity assessment. Overall fidelity was higher on nurse self-report (97.7%) than on objective video-rating (84.2%). Percentage agreement between nurse self-report and video-rating was 73.3% (95% CI 71.3 to 75.3). Fidelity was lowest for advice on footwear and walking aids. The nurse reported difficulty advising on thermal treatments, footwear and walking aids, and did not feel confident negotiating achievable and realistic goals with participants.

Conclusions

A trained research nurse can deliver most components of a non-pharmacological intervention for knee pain to a high degree of fidelity. Future research should assess intervention fidelity in a routine clinical setting, and examine its clinical and cost-effectiveness.

Trial registration number

Keywords: knee, rheumatology, musculoskeletal disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This mixed methods study used a combination of techniques to assess treatment fidelity.

We triangulated the fidelity scores with the findings from interview study and found convergence providing internal validity.

We identified the components not delivered as intended.

A single nurse was involved in delivery of the intervention.

Lack of formal assessment of nurse knowledge of managing knee osteoarthritis.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis and is managed predominantly in primary care in the UK. The knee is commonly affected, with approximately one in four adults over the age of 50 years in the UK self-reporting chronic knee pain, defined as pain for 3 months or longer within the previous 12 months.1 In the presence of activity related joint pain, no or minimal morning stiffness, and age≥45 years, a clinical diagnosis of OA may be reached without the need of investigations (e.g. blood tests or radiography) as per the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.2 These guidelines2 also recommend a patient-centred approach when managing OA, with a focus on non-pharmacological interventions including education, strengthening, and aerobic exercise, and weight loss if required. However, this can be difficult for general practitioners (GPs) to deliver for several reasons such as time constraints and core non-pharmacological treatments are underused.3 4 Nurse-led care gives similar or better outcomes than GP-led care for other chronic diseases.5–8 However, the fidelity of delivery of nurse-led care has not been examined for the management of knee OA.

Fidelity, defined as the degree to which an intervention is delivered as intended,9 regulates the relationship between interventions and outcomes, and determines the extent to which an intervention affects the outcome.10 Inferences regarding treatment effect of a complex intervention should therefore not be made without assessing fidelity, because lack of efficacy of an intervention may be due to inadequate implementation.11 Thus, the fidelity of intervention delivery influences the internal and external validity of a study.12 If fidelity is not assessed, effective interventions may be rejected due to poor delivery.13 14

There are several methods to assess treatment fidelity, including direct observation, patient self-report questionnaires and provider self-report checklists, and indirect observation using audio or video-recordings,13 which may be used singularly or in combination. Direct observation is considered the gold-standard; however, it can be intrusive and may affect patient practitioner interaction,15 16 and may not be feasible in large randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Provider self-report methods are simple and inexpensive but can be inaccurate,17 and patient report methods are even less reliable.13 Video-recording the delivery of intervention and independent assessment of fidelity may provide a robust alternative to direct observation.18 Indeed, it has been shown previously that assessing fidelity using independently rated recordings and provider self-report checklist is feasible and acceptable.19–21 A combination of provider self-report and independent assessed video recording was used in the current study to provide an in-depth fidelity assessment.22 Video recordings were chosen as this is less intrusive than direct observation and provide an opportunity to assess reliability.

Medical Research Council guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions23 have highlighted the importance of conducting process evaluation. Its purpose is to assess the quality and quantity of the implementation of intervention, and trials that collect rich qualitative data may identify potential barriers and facilitators to intervention implementation. However, collecting only qualitative or quantitative data to assess treatment delivery would not unearth a comprehensive picture to understand complex constructs within the intervention.24 For this reason, a mixed methods approach was used.25

The present study is part of the East-Midlands Knee Pain Cohort RCT study,26 the overall purpose of which is to evaluate the feasibility of a nurse-led package of care for knee pain due to OA. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the fidelity of delivery of a nurse-led non-pharmacological package of care for knee pain during the package development phase of the RCT.

Methods

Study design

A mixed methods study with an explanatory sequential and convergent design. This form of mixed methods approach was used to produce additional insights of the issue at hand. In this design, qualitative and quantitative data are collected and complementary results arise from the use of different methods.27 In the current study, the quantitative data informed the collection of qualitative data and a convergence approach was followed.

Setting

Academic Rheumatology, City Hospital Nottingham.

Participants and recruitment

The participants were adults self-reporting knee pain. Community dwelling adults participating in the Investigating Musculoskeletal Health and Wellbeing cohort,28 self-reporting knee pain were sent a postal invitation to participate in this study. People who responded underwent telephone screening to assess eligibility. The inclusion criteria were: age>40 years, ability to read and write in English, knee pain present for longer than 3 months, pain in or around the knee on most days of the previous month, and at least moderate pain in two of the five domains of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index pain scale.29

Research nurse training

A training programme to enable a nurse to deliver the current NICE guidelines for OA management was developed and an educational manual produced.26 The training included face-to-face learning, case-studies, on-line resources and simulated patients. Practical sessions on assessing the participant, delivering and modifying exercise, weight loss advice and use of strategies to encourage adherence were also included. The nurse delivering the intervention was working as a research nurse previously and did not have prior knowledge of musculoskeletal diseases, had not worked in rheumatology or allied specialties such as orthopaedics, rehabilitation or sports medicine, and had never delivered treatments for arthritis.

Patient and public involvement

Three patient and public involvement members with hip and/or knee OA provided input into the content of the non-pharmacological treatment package, and volunteered for nurse training. They advised that video recording of treatment sessions would be acceptable to participants.

Intervention

The template for intervention description and replication checklist30 has been used to describe the intervention and its key features (online supplemental file 1). In brief, the intervention consisted of a holistic assessment of the participant, providing education about the nature of OA and self-management strategies including advice on the role of exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and use of adjunctive treatments such as application of heat or cold, foot-wear modification and use of walking aids. At the first visit, the nurse took a medical history, examined the knee joints and explained to the participant that they had knee pain due to OA. Investigations and radiographs were not undertaken as per NICE guidelines.2 The chief investigator (AA) was available for advice if a clinical diagnosis of OA could not be reached. In that case, the participant would be deemed ineligible for the study. All participants were given an Arthritis Research UK leaflet on knee OA. The nurse explained aerobic and strengthening exercises and advised each participant on an individualised regimen that was mutually agreed. If required, weight-loss advice was provided. Behaviour change strategies31 such as goal setting, action planning, assessment of participant confidence to achieve goals, discussion of barriers and facilitators and the use of exercise diaries were used to improve adherence. Functional goals were agreed and were used to facilitate the exercise prescription with goals being specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and timely (SMART). SMART weight loss goals were agreed also with overweight participants. The intervention is described in more detail in the protocol.26 After the training period, the nurse delivered the intervention in four sessions over a 5-week period.

bmjopen-2020-045242supp001.pdf (95.6KB, pdf)

Consent

All study participants including the research nurse gave their written informed consent prior to treatment delivery, including the consent to video record the sessions. Participants had the right to pause or stop the video recording at any point without giving any reasons.

Fidelity assessment

The study followed the National Institutes of Health Behaviour Change Consortium (NIHBCC) guidelines for fidelity assessment.13 The fidelity checklist was developed a priori26 and comprised eight components, each with specific tasks: materials; introduction; assessment; education; exercise; weight loss; advice on adjunctive treatments; and review and planning. However, not all components of the intervention were intended to be delivered in each session.26 For example, advice on the adjunctive treatments could be provided in any of the four sessions. The fidelity checklist was iteratively developed using a five-step methodology.32 These were: reviewing previous measures, analysing intervention components and developing an intervention framework (intervention manual), developing the fidelity checklist, obtaining feedback about the content and wording of checklist and piloting and refining the checklist to assess and improve reliability. The responses of the fidelity checklist were categorical and rated as completed, partially completed, not completed or not applicable. Partially completed scores were given for any task that was not delivered to the full extent in the context of that particular consultation. The scoring criteria of the fidelity checklist followed that of previous published strategies for assessing fidelity in RCTs of complex interventions.33

Eighteen participants received the non-pharmacological intervention and all (n=62) sessions were video-recorded. After every session with the participant, the nurse completed the fidelity checklist. Sixty-two checklists, 18 for session 1, 16 for session 2 and 14 each for sessions 3 and 4 were completed. Blinded to the nurse ratings, the video-recording of every session was independently reviewed and rated by PAN. A second-rater (MH) independently rated 20% (n=12) of the sessions. Both raters were familiar with the intervention. The refinement, reliability and feasibility of the fidelity checklist were established during the initial phases of the data collection process.

Quantitative data analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD), median and inter quartile range (IQR), and n (%), were calculated for descriptive purposes. Within a component, tasks rated as ‘completed’ were given a score of 2, ‘partially completed’ a score of 1, and not completed, a score of 0. To obtain fidelity score for a component of the intervention, individual scores for each task within the component were added and divided by the maximum possible score for that component and converted to a percentage. Any tasks that were rated as not-applicable were excluded from the calculation.

Median fidelity scores (%) and IQR were calculated for the entire intervention, per participant, per session and per component of the intervention. Fidelity was classified as previously reported: 80%–100% ‘high’, 51%–79% ‘moderate’ and 0%–50% ‘low’ fidelity.34 Where fidelity was moderate or low in a particular component, we further explored this by examining the fidelity of delivery of the individual tasks.

Percentage agreement with 95% CI was used to estimate the level of agreement between self-report and video-record methods, and for inter-rater agreement.

Qualitative phase

One week after the final session, the nurse took part in a semistructured interview conducted by PAN (PhD student) and AF (trained qualitative researcher). The interview guide (online supplemental file 2) contained open-ended questions developed by the study team, which included a rheumatologist (AA), physiotherapists (MH, PAN), psychologist (RdN) and qualitative researcher (AF). The guide covered the nurse’s view on their training, confidence in and experience of delivering the individual components of the non-pharmacological intervention, perceived barriers to delivering it as planned and opportunities to improve the non-pharmacological package of care. An iterative process was used for data collection, so an additional interview was conducted 45 weeks later to capture any salient points raised from the initial quantitative and qualitative data collected.

bmjopen-2020-045242supp002.pdf (164.5KB, pdf)

Before starting the interview, it was explained that the nurse’s responses would remain confidential and that any quotes included in future publications would not identify them. The nurse was informed of the right to withdraw from the interview at any time. We have not provided demographic details in order to protect the anonymity of the individual nurse. All interviews were conducted in a private room in Academic Rheumatology, City Hospital, Nottingham. The qualitative findings were mapped onto the fidelity checklist to assess convergence between the quantitative and qualitative findings. Any areas of uncertainty or gaps were then explored in the second interview with the nurse.

Qualitative data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim by an external transcription company. The interviewer removed any identifiers and ensured transcripts were accurate. Transcripts were analysed following the principles of the general inductive approach.35 The latter is a simple straightforward approach, which is used to derive findings from raw qualitative data, condense them into a brief summary format and link the research objectives with the summary findings.

The first transcript was read several times before data related to the research objectives were identified, labelled and categorised. The categories were discussed between the interviewer and a second researcher (AF). This process identified gaps and led to the second interview and the transcript was analysed in the same way. Following agreement that the categories reflected the overall account reported by the nurse, extracts were taken from the transcripts to exemplify the findings.

Convergence

A meta-matrix was developed to explore convergence between the findings. This approach enhances study validity by increasing the probability that our findings and interpretations are credible and reliable.24 Convergence was defined as agreement between both sets of data, and discrepancy as disagreement between them.

Reporting guidelines

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence guidelines36 were used to improve the quality of reporting of this study.

Results

Quantitative findings

Eighteen participants (33% women) with knee pain for longer than 3 months, with a mean age of 68.7 (SD 9.0) years and body mass index of 31.2 (SD 8.4) kg/m2, respectively, took part in the study. Of these, 14 completed all four visits. The reasons for dropping out were other commitments (n=3), reluctance to lose weight (n=1) and inadequate understanding of the nature of the intervention (n=1).

In total, 62 intervention sessions were delivered. The median (IQR) duration of the initial and follow-up sessions was 87 (81–101) and 46 (37–52) min, respectively. Overall fidelity was rated high for both nurse self-report (97.7%) and video-rated scores (84.2%) (tables 1 and 2). Inter-rater agreement for the video-recording checklist was 70.3% (95% CI 64.4 to 74.2).

Table 1.

Nurse self-reported fidelity scores*

| Intervention component | Session 1 (n=18)† | Session 2 (n=16)† | Session 3 (n=14)† | Session 4 (n=14)† |

| Materials | 100 (100, 100) | – | – | – |

| Introduction | 100 (100, 100) | – | – | – |

| Assessment | 100 (98.3, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) |

| Education | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) |

| Exercise | 100 (97.5, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (97.5, 100) | 100 (75, 100) |

| Weight loss | 100 (88.9, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (66.7, 100) | 100 (79.2, 100) |

| Adjunct treatments | 87.5 (33.3 100) | 87.5 (0, 100) | 66.7 (45.8, 100) | – |

| Review and planning | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) |

*Values are median% (IQR).

†Number of sessions.

Table 2.

Fidelity scores using video-recordings of the sessions*

| Intervention component | Session 1 (n=18)† | Session 2 (n=16)† | Session 3 (n=14)† | Session 4 (n=14)† |

| Materials | 100 (100, 100) | – | – | – |

| Introduction | 100 (75, 100) | – | – | – |

| Assessment | 91.4 (85, 93.3) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) |

| Education | 78.1 (74.1, 93.8) | 87.5 (50, 100) | 87.5 (50, 100) | 100 (93.8, 100) |

| Exercise | 94.4 (88.9, 100) | 88.9 (75, 94.4) | 86.1 (72, 100) | 75 (67.6, 82.8) |

| Weight loss | 100 (87.5, 100) | 90 (60, 100) | 100 (68.9, 100) | 80 (49.2, 100) |

| Adjunct treatments | 50 (45.8, 100) | 0 (0, 50) | 50 (0, 100) | – |

| Review and planning | 75 (75, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 75 (37.5, 100) |

*Values are median% (IQR).

†Number of sessions.

For the nurse self-report checklist, median fidelity scores for each session ranged from 94.4% to 100% (table 1). Individual components received high ratings except for adjunctive treatments, that is, use of heat/cold therapy and advice on footwear where the fidelity score was moderate in many sessions.

For the video-rated checklists, overall median fidelity scores for each session ranged from 77.7% to 87.2% (table 2). Fidelity for education was lower in the first session (78.1%, IQR 74.1–93.8) but increased in the follow-up session (87.5%, IQR 50, 100). Fidelity for review and planning was lower in the first and last sessions. Fidelity scores were low for adjunctive treatments across all sessions, and varied from 0% to 50%. Fidelity of delivery for exercise goal-setting was moderate at 66% and fidelity for reviewing goals during follow-up sessions was low, ranging between 44% and 50%. Additionally, assessment of patients’ level of confidence to achieve their exercise goal was low in the follow-up sessions, ranging between 7% and 40%.

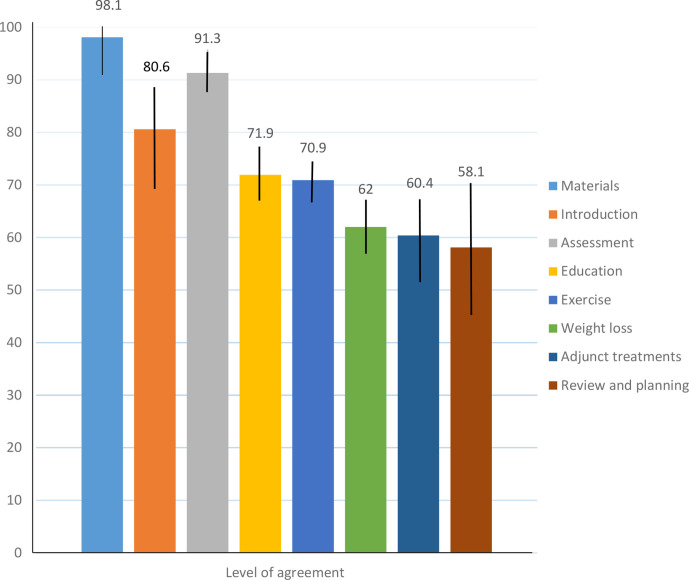

The overall agreement between nurse-rated and video-rated methods was 73.3% (95% CI 71.3 to 75.3). The level of agreement for individual components is shown in figure 1. Excellent agreement was found for materials, introduction and assessment. Agreement was below the cut-off point of 80% for education, exercise, weight loss and adjunctive treatment. The level of agreement for review and planning component was 58.1% (95% CI 44.8 to 70.5). For individual participants, overall fidelity across the four sessions ranged from 75% to 100% indicating that for most patients the intervention was delivered as intended (table 3).

Figure 1.

Agreement between nurse-rated and video-rated methods for the components of the intervention. Values shown are % agreement and error bars indicate the 95% CI.

Table 3.

Fidelity scores assessed using video-recordings across participants*

| Participant number | Overall sessions |

| Participant 1 | 88.9 (75, 100) |

| Participant 2 | 83.3 (41.7, 100) |

| Participant 3 | 100 (67.5, 100) |

| Participant 4† | 96.7 (88.9, 100) |

| Participant 5 | 75 (45, 100) |

| Participant 6 | 100 (80, 100) |

| Participant 7 | 100 (89.9, 100) |

| Participant 8† | 100 (95.8, 100) |

| Participant 9 | 92.9 (50, 100) |

| Participant 10 | 93.7 (77.5, 100) |

| Participant 11† | 75 (50, 97.2) |

| Participant 12 | 73.8 (18.8, 100) |

| Participant 13 | 100 (67, 100) |

| Participant 14 | 100 (79, 100) |

| Participant 15 | 85 (56, 100) |

| Participant 16 | 100 (75, 100) |

| Participant 17 | 100 (80, 100) |

| Participant 18† | 100 (81, 100) |

*Values are median% (IQR).

†Participants dropped out. The percentage fidelity score is calculated using scores from the sessions attended.

Qualitative findings

The duration of the initial and follow-up interview with the nurse was 94 minutes, and 34 minutes respectively. The nurse reported feeling nervous when delivering the intervention for the very first time, but felt more comfortable as the sessions progressed.

‘Very nervous… to start with… I don't think after a few sessions I was uncomfortable, I was probably more comfortable delivering the intervention…after few sessions, got better at getting feedback from patient as well so I think that boosted my confidence’.

The nurse felt that patient assessment was easy to deliver considering their previous experience of assessing patients for other diseases.

‘I would say some of them were easy to find pinpoint the problems…as a nurse we always been asking these questions to patients… in this case but had previous experience in that area’.

The nurse felt that education was not always delivered as well in the first few sessions as in the follow-up sessions. They felt that there was a lot of information for the participants to take on board during that first initial assessment session and recommended that the advice could be spread over two or three sessions.

‘First few sessions I didn’t think of as very good to tell them about the information and then later on, I built that …’

‘I think that session could be divided, erm, the very first one at least in two sessions… so first session, you just get to know the patient and they get their feedback and, don’t give them any, too much of a diet and weight loss information’.

The nurse described how they initially lacked confidence in prescribing exercise, which was a new skill, to the patients.

‘I had to decide after the assessment which exercise I'm going to assign them and I didn’t feel comfortable…“I wasn’t sure that whatever assessment I have done and the exercise I choose, that’s going to make it any better …I wasn’t 100% sure’.

On the other hand, it was easier to determine and link the exercises for patients who already had obvious problems in their knees.

‘When there are obviously problems in the knee you can see, you can link what exercise… when you can’t see the obvious problems, then it was difficult to determine what exercise you are going to assign’.

They felt more confident and were able to adapt the exercises as they became more familiar with the exercises and having received feedback from the patients.

‘I felt comfortable altering the exercise for them,… knowing that obviously, if it’s painful for them then switching to a different exercise’.

The nurse delivered the weight loss advice with ease compared with the exercise and was able to explain to patients why it is good to lose weight where required.

‘For the weight loss, you easily do that… I didn’t feel too much uncomfortable…so positive from that is that I managed to tell everyone’.

Even though they felt it was not difficult to deliver or incorporate the adjunctive treatments, they occasionally forgot to mention them or felt it was not necessary to repeat this in a subsequent session.

‘I do not think it was difficult to ask that or incorporate… it was probably as a human error or that you forgot to mention it…with some patients if you already mentioned once or twice, so with the first session, that if you need to you can use hot and cold therapy, and then they refuse it … then there is no point [mentioning it again]’.

The nurse found it challenging to negotiate realistic goals with some patients, especially those who had high expectations but rated their confidence in achieve their goals as low.

‘The difficulty is that the goal setting they would expect high but then they when you ask them how likely you are going to achieve this goal their rating will be low… their rating will be like 4 or 5 and how you motivate them to go up to 8 or 7, 8, 9, that one’s kind of difficult’.

However, the nurse was able to reduce the expectation that was initially set for that particular goal for those patients.

‘Obviously there was a previous goal…yes would reduce the expectation when they came back, I would be able to do this, so I am sure you would be able to see through the videotape’.

Integrating findings

Convergence was found between the fidelity scores and nurse interview (table 4). The excellent fidelity scores for the holistic assessment by the nurse was reflected in their confidence of assessing patients more generally. The moderate fidelity findings for education in the first session that increased in subsequent sessions were confirmed by the nurse and explained in terms of moderating the amount of information that was given to participants in the first session. Weight loss advice was delivered with high fidelity and the nurse also felt confident in being able to deliver weight loss advice fully. A perceived lack of confidence in delivering the exercise component is consistent with lower fidelity scores for the exercise component. The adjunctive treatments were not always delivered as intended and that was consistent with the interview findings. Goal setting was challenging for the nurse which was reflected in the fidelity findings. Finally, convergence was found for review and planning as the nurse found it easy to summarise patient goals at the end of each session. There were no divergent findings.

Table 4.

Convergence between fidelity observed using video recordings and the results from the semi-structured nurse interview

| Intervention components | Median (%) IQR fidelity* | Qualitative interview findings | Convergence |

| All components | 84.2 | ‘I find myself that … that I can deliver the care…I was probably more comfortable delivering the intervention…after few sessions’ | Yes |

| Materials | 100 (100, 100) | ‘I had to show them the booklet every patient so I don’t think I have forgotten to do that’ | Yes |

| Introduction | 100 (75, 100) | ‘I explain all the study and then explain that whole process again for the purpose of the session’ | Yes |

| Assessment | 100 (100, 100) | ‘I would say some of them were easy to find pinpoint the problems…as a nurse we always been asking these questions to patients… in this case but had previous experience in that area’ | Yes |

| Exercise | 88.9 (72.7, 94.4) | ‘We practiced and demonstrated exercises… I felt comfortable altering the exercise for them…I just couldn’t think how to link that, erm, goal setting I didn’t deliver it good… I don't think I could have delivered it any better than that either… some did actually achieve the goal’ | Yes |

| Education | 87.5 (74.1, 100) | ‘first few sessions I didn’t think of as very good to tell them about the information and then later on, I built that’ | Yes |

| Weight loss | 100 (77.8, 100) | ‘Positive from that is that I managed to tell everyone that, ‘you need to lose weight’, so I think it was kind of structured in a way… I didn’t feel too much uncomfortable’ | Yes |

| Adjunct treatments | 50 (0, 50) | ‘it was probably as a human error or that you forgot to mention it…with some patients if you already mentioned once or twice so with the first session that you need to you can use hot and cold therapy and then they refuse it and then there is no point’ | Yes |

| Review and planning | 100 (25, 100) | ‘Not difficult… we always talked about it this is what we discussed it today this is the exercise we, have assigned you and if you feel that you can progress into further do so’ | Yes |

*Median fidelity scores of the individual components across the four sessions.

Discussion

This study evaluated fidelity of delivery of a nurse-led non-pharmacological package of care for knee pain due to OA and validated the findings in an interview with the nurse that delivered it. The majority of the non-pharmacological components of the intervention were delivered with good fidelity. Excellent fidelity was found for patient assessment, education, demonstration and advice on exercise and weight loss advice. Tasks that demonstrated lower fidelity within the exercise component included goal setting and review. These were also perceived as difficult by the nurse. Advice around the use of adjunctive treatments such as the use of hot or cold treatments, walking aids and footwear, was also not always delivered as planned. Agreement between the nurse and independent rater was below the cut-off point of 80% for education, exercise, weight loss, adjunctive treatment and review and planning, which is reported as the minimum acceptable agreement between raters.37 Fidelity scores across different participants were high overall with the lowest score being 74%.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that has assessed fidelity of a nurse-led non-pharmacological intervention for knee pain due to OA and integrated the findings. Our study is based on a fidelity checklist that has been previously validated in complex interventions delivered in a research setting.21 We tailored the checklist according to the intervention and further refined it. Moreover, the reliability of the fidelity checklist was established when two independent viewers scored the video recordings of the sessions.

From the interview transcripts, factors that influenced fidelity of delivery are identified. The nurse was less confident to identify appropriate patient goals and prescribe exercise in the first few sessions, but this improved thereafter. This is not a barrier per se, but suggests that some further training and additional support for nurses in this new role would be needed to ensure fidelity at the start of the study. The nurse was able to draw on her previous experience working with other patient groups to discuss and assess complex issues. Nurse’s previous experience assessing patients, therefore, facilitated fidelity of delivery. Although the fidelity for education appeared to be lower in the first session, this was because the nurse recognised and responded that participants were being given a lot of information. These findings are not surprising as we aimed to train a nurse with no prior experience of managing musculoskeletal diseases to deliver a complex non-pharmacological package of care for knee pain. Where the nurse identified difficulties in delivering the intervention as intended, she was able to seek additional advice and training from MH. This experience has allowed us to further improve the nurse training programme for use in the feasibility RCT.

Previous studies using mixed methods have explored factors that influenced fidelity and found good fidelity of delivery of a physiotherapist-led complex package of care for chronic low-back pain and OA.21 22 They report on the factors that influenced fidelity on three levels: provider, participant and programme. Williams et al38 demonstrated good fidelity of delivery of a walking intervention when delivered by nurses and healthcare assistants in primary care. Even though they used a mixed methods approach to assess fidelity, they did not integrate the findings. In our study, the research nurse rated themselves higher than the independent rating using the video recordings consistent with previous studies.32 39 Similar findings on barriers and facilitators have been identified in two complex interventions, one for people with dementia and one for people with chronic low back pain.22 32 In fact, Walton et al32 extended over the factors that influenced fidelity of delivery reported by Toomey et al22 and recognised that knowledge, providers’ attributes, ease of adaptation of the intervention in relation to participants’ needs influenced fidelity. Based on the findings, it was challenging to address adaptation and determine the appropriate balance between fidelity and adaptation in this study. This may indicate some key overlapping themes that may limit fidelity of delivery despite the different types of intervention and conditions.

There are a number of limitations to this study. A key caveat is that only one nurse was involved in delivery of the intervention. In a larger trial, there would be more nurses to deliver the intervention across multiple sites, which increases the likelihood of variation in fidelity. This study lasted 17 weeks and this is a short period of time over which fidelity may not fluctuate much. However, this can be an issue with longer studies.40 The nurse who delivered the intervention was interviewed but in the absence of data from additional participants, emerging categories could not be revised and refined into fully realised themes; however, an inductive approach to analysis was taken to reflect the views of the intervention provider. A second interview with the nurse was conducted to capture any salient points not discussed during the first interview. We did not consider to capture engagement of the participants in the study. Complex interventions are often a dynamic interplay between patient and healthcare professionals. While checklists can be helpful in determining whether an intervention has been delivered they do not allow for or capture the flexibility that is required when tailoring an intervention to the individual.

The intervention was delivered by a research nurse with no background knowledge of musculoskeletal diseases and no previous experience delivering treatment for arthritis. This is a particular strength as we were able to assess the effectiveness of our nurse training programme and its shortcomings. Additionally, we video-recorded and evaluated all the consultations that were delivered. One of the key strengths of our study was that we identified the specific components of the intervention not delivered as intended. Moreover, we triangulated the findings and found convergence providing internal validity. The nurse was interviewed to address some of the NIHBCC components (study design, provider training) that have not been examined previously.22

In conclusion, we found that nurse-led delivery of a complex package of care is feasible within a research setting. The research nurse delivered care for patients with knee pain due to OA with high fidelity for most of the components of the intervention except for advice about the use of hot/cold treatments, walking aids, footwear and goal setting. We believe that upskilling nurses to deliver complex non-pharmacological components for the management of knee pain due to OA is feasible. Nurses would have more time to spend with patients and educate them about the condition. The training package for delivery of the intervention will need to ensure that the nurses are confident in delivering the behavioural change strategies such as goal setting. Follow-up training sessions and support during the start of the feasibility when nurses are first delivering the intervention may be helpful in order to improve confidence and delivery. Future work will need to consider fidelity where there will be more than one nurse delivering the intervention in a clinical setting where other factors will also influence fidelity. Our results, nevertheless, show that it is feasible to apply the non-pharmacological package of care in a future feasibility RCT.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @lll_millar

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design and conception of the study. PAN conducted the quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. MH was the independent rater for video assessment of fidelity. AF and RdN provided guidance in the qualitative data collection and analysis. RO, AA and MH provided guidance in the quantitative analysis. BM contributed to the study set up and recruitment. PAN wrote the first draft. All authors have read, provided critical feedback and approved the final manuscript. PAN has access to qualitative and quantitative data and vouches to the accuracy of data analysis.

Funding: This work was supported and cofunded by the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre and the Pain Centre Versus Arthritis (Internal funding 2017- 2022). The views expressed are those of author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The study is sponsored by the University of Nottingham, UK.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. TIDieR checklist, and interview topic guides have been included as supplementary files. Quantitative fidelity checklists are included as supplementary files in the published protocol. Please email the corresponding author at Polykarpos.nomikos@nottingham.ac.uk whether further information is required.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

Ethics approval

The study received ethical approval by the East Midlands-Derby Research Ethics Committee (REC) (18/EM/0288).

References

- 1.Jinks C, Jordan K, Ong BN, et al. A brief screening tool for knee pain in primary care (KNEST). 2. results from a survey in the general population aged 50 and over. Rheumatology 2004;43:55–61. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Osteoarthritis: care and management, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egerton T, Nelligan RK, Setchell J, et al. General practitioners' views on managing knee osteoarthritis: a thematic analysis of factors influencing clinical practice guideline implementation in primary care. BMC Rheumatol 2018;2:30. 10.1186/s41927-018-0037-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porcheret M, Jordan K, Jinks C, et al. Primary care treatment of knee pain--a survey in older adults. Rheumatology 2007;46:1694–700. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2018;392:1403–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32158-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saffi MAL, Polanczyk CA, Rabelo-Silva ER. Lifestyle interventions reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014;13:436–43. 10.1177/1474515113505396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strömberg A, Mårtensson J, Fridlund B, et al. Nurse-Led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure: results from a prospective, randomised trial. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1014–23. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00112-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welch G, Garb J, Zagarins S, et al. Nurse diabetes case management interventions and blood glucose control: results of a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;88:1–6. 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen JD, Linnan LA, Emmons KM. Fidelity and its relationship to implementation effectiveness, adaptation, and dissemination. In: Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice, 2012: 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, et al. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci 2007;2:40. 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moncher FJ, Prinz RJ. Treatment fidelity in outcome studies. Clin Psychol Rev 1991;11:247–66. 10.1016/0272-7358(91)90103-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colditz GA, Emmons KM. The promise and challenges of dissemination and implementation research. In: Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice, 2012: 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borrelli B. The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fidelity in public health clinical trials. J Public Health Dent 2011;71:S52–63. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00233.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker MF, Hoffmann TC, Brady MC, et al. Improving the development, monitoring and reporting of stroke rehabilitation research: consensus-based core recommendations from the stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Int J Stroke 2017;12:472–9. 10.1177/1747493017711815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change Consortium. Health Psychol 2004;23:443–51. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French SD, Green SE, Francis JJ, et al. Evaluation of the fidelity of an interactive face-to-face educational intervention to improve general practitioner management of back pain. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007886. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jobe JB. Cognitive psychology and self-reports: models and methods. Qual Life Res 2003;12:219–27. 10.1023/A:1023279029852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulte AC, Easton JE, Parker J. Advances in treatment integrity research: multidisciplinary perspectives on the conceptualization, measurement, and enhancement of treatment integrity. School Psychology Review 2009;38:460–75 https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-00081-002 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huijg JM, Dusseldorp E, Gebhardt WA, et al. Factors associated with physical therapists' implementation of physical activity interventions in the Netherlands. Phys Ther 2015;95:539–57. 10.2522/ptj.20130457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKenna JW, Flower A, Ciullo S. Measuring fidelity to improve intervention effectiveness. Interv Sch Clin 2014;50:15–21. 10.1177/1053451214532348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toomey E, Matthews J, Guerin S, et al. Development of a feasible implementation fidelity protocol within a complex physical Therapy-Led self-management intervention. Phys Ther 2016;96:1287–98. 10.2522/ptj.20150446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toomey E, Matthews J, Hurley DA. Using mixed methods to assess fidelity of delivery and its influencing factors in a complex self-management intervention for people with osteoarthritis and low back pain. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015452. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farmer T, Robinson K, Elliott SJ, et al. Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qual Health Res 2006;16:377–94. 10.1177/1049732305285708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall M, Fuller A, Nomikos PA, et al. East Midlands knee pain multiple randomised controlled trial cohort study: cohort establishment and feasibility study protocol. BMJ Open 2020;10:e037760. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. 5 edn. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millar B, McWilliams DF, Abhishek A, et al. Investigating musculoskeletal health and wellbeing; a cohort study protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2020;21:1–10. 10.1186/s12891-020-03195-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellamy N. WOMAC osteoarthritis index user guide. vol. 5. Brisbane, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michie S, Rumsey N, Fussell A. Improving health: changing behaviour. In: Nhs health trainer Handbook, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walton H, Spector A, Roberts A, et al. Developing strategies to improve fidelity of delivery of, and engagement with, a complex intervention to improve independence in dementia: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020;20:1–19. 10.1186/s12874-020-01006-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ang K, Hepgul N, Gao W, et al. Strategies used in improving and assessing the level of reporting of implementation fidelity in randomised controlled trials of palliative care complex interventions: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2018;32:500–16. 10.1177/0269216317717369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borrelli B, Sepinwall D, Ernst D, et al. A new tool to assess treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of health behavior research. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:852–60. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 2006;27:237–46. 10.1177/1098214005283748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. Squire 2.0 (standards for quality improvement reporting excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:986–92. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med 2012;22:276–82. 10.11613/BM.2012.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams SL, McSharry J, Taylor C, et al. Translating a walking intervention for health professional delivery within primary care: a mixed-methods treatment fidelity assessment. Br J Health Psychol 2020;25:17–38. 10.1111/bjhp.12392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardeman W, Michie S, Fanshawe T, et al. Fidelity of delivery of a physical activity intervention: predictors and consequences. Psychol Health 2008;23:11–24. 10.1080/08870440701615948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radford K, Sutton C, Sach T, et al. Early, specialist vocational rehabilitation to facilitate return to work after traumatic brain injury: the fresh feasibility RCT. Health Technol Assess 2018;22:1–124. 10.3310/hta22330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045242supp001.pdf (95.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-045242supp002.pdf (164.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. TIDieR checklist, and interview topic guides have been included as supplementary files. Quantitative fidelity checklists are included as supplementary files in the published protocol. Please email the corresponding author at Polykarpos.nomikos@nottingham.ac.uk whether further information is required.