Abstract

Coordination of primary care is essential to improving care delivery within health systems, especially for older adults with increased health/social needs. A program jointly funded by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement and Canadian Frailty Network, was implemented in a nurse practitioner-led clinic to address the gap in frailty care for older adults. The clinic was situated within a health and social services organization with a mandate to enhance the quality of life of older adults living in the community. Through this program, a frailty assessment pathway and social/clinical prescriptions were implemented with necessary adaptations as a result of COVID-19.

Keywords: frailty, pilot, older adults, primary care, social needs, health promotion

Introduction

Patients with complex care needs, including older adults, suffer from multiple chronic conditions; cognitive, functional, and mental health impairments; drug interactions; or social vulnerabilities.1-3 Healthcare expenditure on average for older adults living in Canada was approximately 4 times more than that of the general population between 2017 and 2018, at $12 000 per person. 4 Yet, 45% of older adults cannot access timely appointments with primary care providers, 32% struggle to secure transportation needed to access services, 39% visited an emergency room in the last 2 years, and only 16% of those with chronic conditions have received comprehensive follow-up. 5

The Government of Alberta reports that 4000 Albertans turn 65 every month with a projected steady increase to more than 1 million by 2035, placing a further strain on primary care. 6 Calls-to-action for primary care highlighted that better coordination of health and social services, effectively managed transitions across care settings, and implementation of team-based care models with professionals working to their full scope of practice were imperative.7-10 An example of this model is at Sage, where a Nurse Practitioner (NP) led clinic (herein referred to as Sage clinic) was established alongside social care services, senior-driven programming, and community-based outreach in Edmonton, Alberta. NPs are registered health professionals who assess, diagnose, treat, order diagnostic tests, prescribe medications, make referrals to specialists, and manage overall care. 11 In 2019, 741 older adults who were under resourced including those with low income, facing housing issues, without a primary care provider, or living with multiple comorbidities accessed the Sage clinic for health and social services. They received ad-hoc frailty assessments and inconsistent follow-up. Therefore, implementing standardized frailty assessments and follow-up care for older adults became an organizational priority. The builDing Resilience And respondinG tO seNior FraiLtY (DRAGONFLY) pilot program was conceived and implemented at Sage clinic with successful funding from the Advancing Frailty Care in Community (AFCC) Collaborative (2019-2022).

The aim of DRAGONFLY was to develop an innovative collaborative model to implement frailty care for older adults in the community. However, an unprecedented challenge with the abrupt emergence of 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) necessitated an immediate restructuring of the DRAGONFLY program. In the following sections, we describe the methods, results, and implications of establishing and adapting the DRAGONFLY program within a pandemic context.

Methods

Experience-Based Co-Design

The DRAGONFLY program was developed to benefit older adults living with frailty using the experience-based co-design quality improvement (QI) approach 12 that enabled Sage staff, senior healthcare professionals, a Canadian Frailty Network (CFN) fellow, a patient advisor (older adult living in the community), end-users, and other stakeholders from community programs to co-design the care pathway together. Exclusion criteria to DRAGONFLY were older adults: (1) <50 or >94 years of age and (2) identified cognitive concerns.

DRAGONFLY Pilot Program

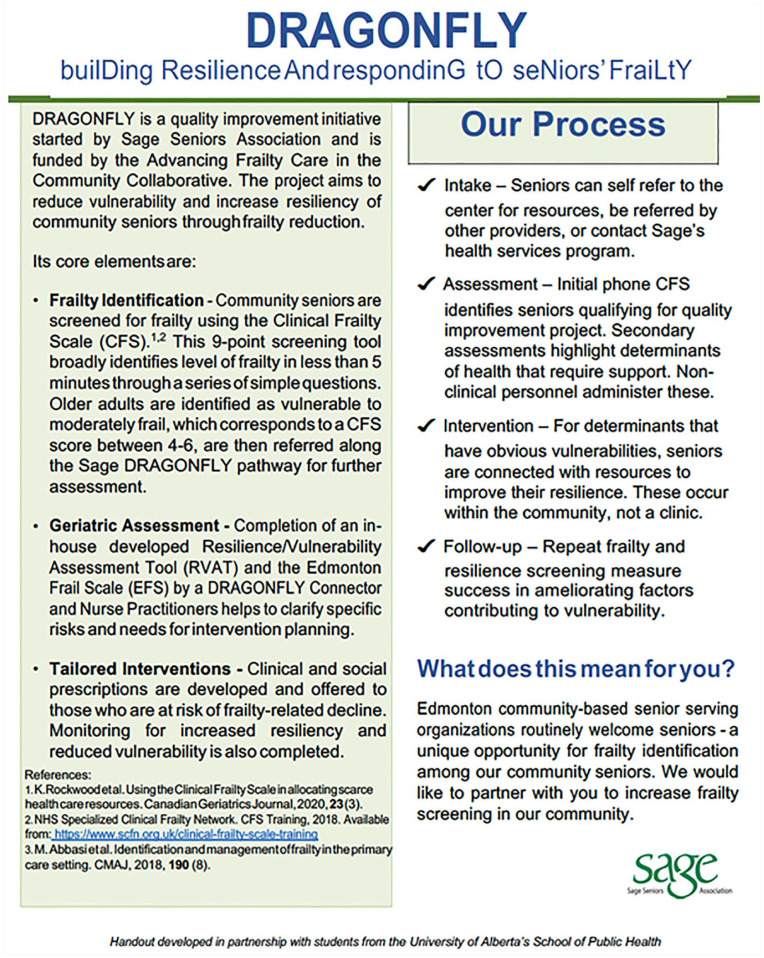

The DRAGONFLY program was launched in mid-February 2020 with the following objectives: (1) standardize frailty identification; (2) improve comprehensive geriatric assessment pathway for older adults with moderate frailty (see definition below); and (3) implement social/clinical prescriptions (see Figure 1). The expected outcome of the program was to obtain lower frailty or the same frailty assessment scores at follow-up (3-, 6-, and 12-months), as a result of implementing social/clinical prescriptions.

Figure 1.

DRAGONFLY program.

However, in March 2020, the pandemic took effect, and in-person visits at the Sage clinic ceased. In response, the DRAGONFLY team adapted all in-person assessments in the original pathway to a virtual/phone format. The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) and Resilience and Vulnerability Assessment Tool (RVAT) (see Supplemental Appendix A) were administered by phone, but the Edmonton Frailty Scale (EFS) could only be administered in-person. 16 An article about the RVAT development and validation will be published elsewhere. The CFS is validated for in-person frailty screening based on clinical judgment 13 but adaptations were allowed for self-report assessments of frailty (see Supplemental Appendix B), and this version of the CFS is not validated.

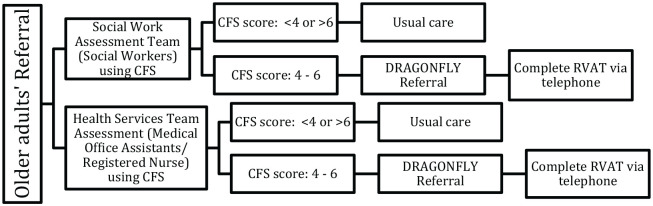

Referral, Assessment, and Intervention Pathway

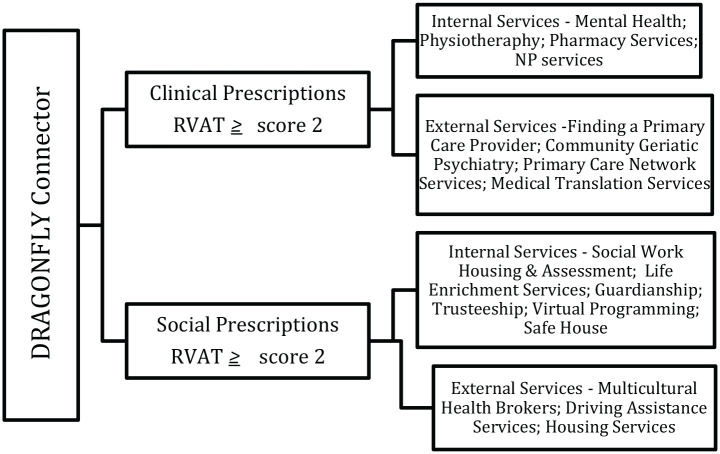

As shown in Figure 2, older adults either self-referred or were referred by external/internal service providers for an assessment where 9 CFS questions were asked to assess older adults’ frailty levels (see Table 1). If older adults scored between 4 and 6 (vulnerable to moderate level of frailty), they were referred to the DRAGONFLY Connector who completed additional assessments using the RVAT. The identified vulnerabilities using the RVAT triggered social/clinical prescriptions based on severity criteria on a continuous scale with a cumulative total of 66. The minimum cut off of 2 out of 66 was determined as a trigger for at least 1 social or clinical prescription based on prior administration of the RVAT (will be described in detail in the subsequent publication on the development/validation of the RVAT). Social prescriptions included services targeted at recreation, financial or housing limitations, or to increase older adults’ resilience (see Figure 3). Older adults paneled with the Sage Clinic or those without a primary care provider were managed by NPs for clinical prescriptions. If older adults had pre-existing primary care providers, the DRAGONFLY Connector referred them back to their provider for additional assessment of noted concerns.

Figure 2.

Assessment pathway.

Table 1.

Adapted CFS Items.

| Screening CFS statement | Score |

|---|---|

| I am terminally ill and at the end of my life | 9 |

| I am completely dependent for all of my personal care | 8 |

| I need help with all of my personal care | 7 |

| I need assistance with out of home activities, require help with bathing or medications, or struggle with stairs | 6 |

| I need physical or practical assistance with finances, transportation, or heavy housework | 5 |

| I am more tired than I used to be, and have more trouble obtaining supports than before, but can still coordinate things myself | 4 |

| My health conditions are well managed, but I am generally inactive. I may require advice on how to obtain supports with finances, transportation, or heavy housework | 3 |

| I am well, but only occasionally active. I can manage finances, transportation, and heavy housework on my own | 2 |

| I am active, energetic, and exercise regularly | 1 |

Figure 3.

Intervention pathway.

Preliminary Results and Analysis

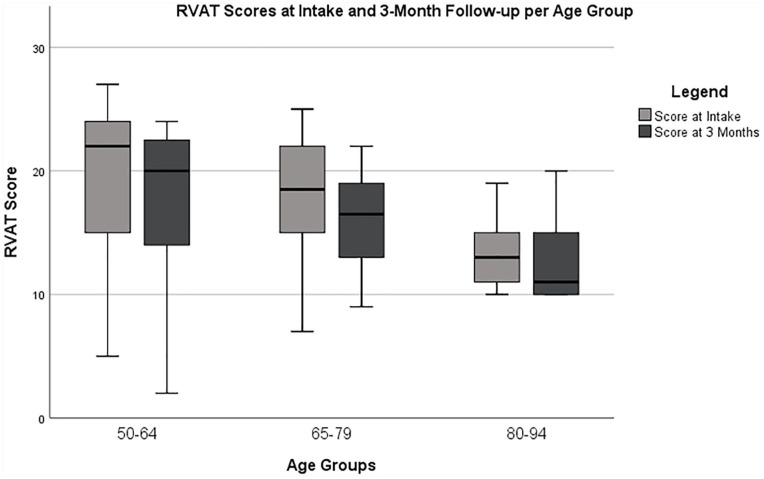

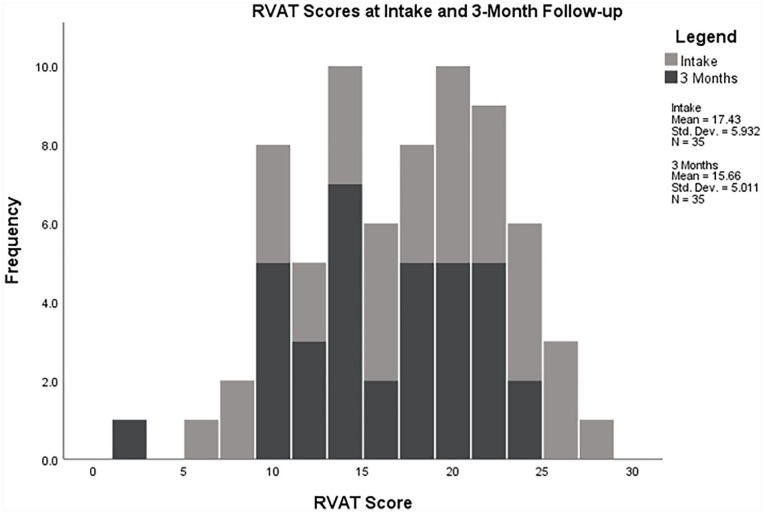

As of April 2021, 61older adults were identified as vulnerable to moderately frail as per the CFS, of which 54 proceeded with the intake RVAT assessment. Seven older adults opted for usual care to address psychosocial needs through Sage in place of the RVAT assessment. Of the 54 who completed an initial RVAT, only 35 completed the follow-up assessment because 5 have not yet reached the 3-month follow-up mark, 5 have experienced significant cognitive decline after the initial RVAT, and 4 were lost to follow-up. At follow-up, there was a decrease in level of frailty and an improvement in resiliency denoted by lower RVAT scores across the age groups between 1.06 and 2.67 (see Table 2; Figure 4). All 54 older adults had RVAT scores between 5 and 30 (see Figure 5) which triggered the need for social/clinical prescriptions based on individual needs identified through the RVAT. The majority of the social prescriptions were related to life enrichment services (n = 63), housing (n = 45), and home supports (n = 27) at intake and follow-up (see Table 3). Most of the clinical prescriptions were related to NP services (n = 31), mental health services (n = 23), and primary care provider attachment (n = 18) at intake and follow-up (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for CFS and RVAT.

| Age groups | CFS* |

RVAT |

RVAT |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intake (N = 61) | Intake (N = 54) | 3-Month Follow-up (N = 35) | |||||||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | Variance | IR | N | Mean | SD | Variance | IR | N | Mean | SD | Variance | IR | |

| 50-64 years | 13 | 4.62 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 1 | 12 | 19.67 | 9.54 | 90.97 | 16 | 7 | 17.00 | 7.96 | 63.33 | 12 |

| 65-79 years | 35 | 4.63 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 1 | 31 | 17.06 | 6.26 | 39.20 | 7 | 22 | 16.00 | 3.98 | 15.81 | 6 |

| 80-94 years | 13 | 4.92 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 2 | 11 | 15.18 | 3.66 | 13.36 | 6 | 6 | 12.83 | 3.97 | 15.77 | 6 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IR, interquartile range.

CFS* score between 4 and 6 indicative of vulnerable to moderate levels of frailty.

Figure 4.

RVAT scores per age group.

Figure 5.

Distribution of RVAT scores.

Table 3.

Social and Clinical Prescriptions at Intake and Follow-up.

| Social prescriptions | Referrals (n) | Clinical prescriptions | Referrals (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing and financial assistance | 45 | NP services | 31 |

| Home supports | 27 | Mental health services | 23 |

| Virtual programming and life enrichment | 63 | Primary care provider attachment | 18 |

| Safe house for elder abuse | 3 | Health navigation | 13 |

| Transportation services | 10 | Physiotherapy | 10 |

| LGBTQ2S+ programming | 1 | Referral to primary care provider | 5 |

| Caregiver supports | 5 | Community geriatric psychiatric services | 7 |

| Support groups | 1 | Pharmacist | 3 |

| Hoarding supports | 1 | Home care | 3 |

| Multicultural health brokers’ services | 1 | ||

| Volunteer services | 3 |

Implications

Despite current pandemic challenges, DRAGONFLY was able to take flight. In keeping with QI objectives, older adults with moderate levels of frailty received assessments and social/clinical prescriptions aimed at improving their resilience. However, challenges were present during the first year of operations for DRAGONFLY. Funding loss for the NP-led clinic at Sage was to take effect on April 1st, 2020 but was superseded by COVID-19 in March. It was unclear what capacity Sage had to implement DRAGONFLY without a health program at Sage.

The restrictions as a result of the pandemic, such as no access to in-person health and social care services at Sage and only urgent home visits meant that the DRAGONFLY team had to modify the program. The DRAGONFLY budget was reallocated. Two full-time DRAGONFLY Connectors (social workers) were hired, to provide stability after the health clinic funding drew to a close. One NP was seconded from a partner academic institution 1 day a week, so that oversight of the program continued. The electronic medical record was redesigned to allow for management of social needs and processes, thereby improving access to timely information across disciplines and comprehensive reporting to support research.

Concurrent validation of the tools to assess frailty and resilience/vulnerability was no longer possible because the CFS was adapted to be administered over the phone, the EFS was not administered, and the RVAT development and validation study was yet to be published. At best, face validity is evident in these tools that were used. As well, EFS-AC (for acute care) was developed and can be administered via telephone as performance-based items were replaced based on previous work by Hilmer et al 14 and Rose et al. 15 The EFS-AC will be considered as part of the assessment pathway within the program in the near future and will need to be validated in the community setting.

The DRAGONFLY team collaborated with a variety of stakeholders along the way, including academic institutions, students, patient advisors, community organizations, and the larger Sage team. Although the original aim of this program was to develop an innovative collaborative model to implement frailty care for older adults in the community, the challenges were so significant that the program had to be modified and tool validity and data collection were compromised. Preliminary results do show that the overall RVAT scores were reduced by 1.06 to 2.67 points at 3-month follow-up across age groups, which implies improved resilience and decreased frailty. As well, data has to be stratified further to determine and report on which clinical/social prescriptions can be attributed to this improvement. Automated reports generated from the electronic medical record on clinical/social prescription data are limited due to a lack of differentiation between intake and follow-up. These preliminary data interpretations are limited and not generalizable because the RVAT is not validated and the CFS has been modified as we described above. Yet, our team believes it is important to publish findings from a pilot study like this, to describe real world challenges with research in clinical practice environments and highlight pragmatic decisions that were taken. Solutions to these limitations are being explored and modifications planned, so that more accurate and meaningful data can be reported to measure the impact of the DRAGONFLY project.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501327211034807 for Customizing a Program for Older Adults Living with Frailty in Primary Care by Jananee Rasiah, Tammy O’Rourke, Brian Dompé, Darryl Rolfson, Beth Mansell, Rachel Pereira, Titus Chan, Karen McDonald and Anne Summach in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jpc-10.1177_21501327211034807 for Customizing a Program for Older Adults Living with Frailty in Primary Care by Jananee Rasiah, Tammy O’Rourke, Brian Dompé, Darryl Rolfson, Beth Mansell, Rachel Pereira, Titus Chan, Karen McDonald and Anne Summach in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-jpc-10.1177_21501327211034807 for Customizing a Program for Older Adults Living with Frailty in Primary Care by Jananee Rasiah, Tammy O’Rourke, Brian Dompé, Darryl Rolfson, Beth Mansell, Rachel Pereira, Titus Chan, Karen McDonald and Anne Summach in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Jananee Rasiah, PhD Candidate, Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta held and was supported by a Canadian Frailty Network Interdisciplinary Fellowship from 2019-2020.

ORCID iDs: Jananee Rasiah  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2987-1200

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2987-1200

Titus Chan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0252-8856

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0252-8856

Anne Summach  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9174-697X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9174-697X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Grant RW, Ashburner JM, Hong CS, Chang Y, Barry MJ, Atlas SJ. Defining patient complexity from the primary care physician’s perspective: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:797-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schaink A, Kuluski K, Lyons R, et al. A scoping review and thematic classification of patient complexity: offering a unifying framework. J Comorb. 2012;2(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, Hudon C, O’Dowd T. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ. 2012;345:e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gibbard R. Meeting the Care Needs of Canada’s Aging Population—July 2018. The Conference Board of Canada; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canadian Medical Association. The State of Seniors Health Care in Canada. Canadian Medical Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Government of Alberta. Population Projections: Alberta and Census Divisions, 2020–2046. Treasury Board and Finance; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rudoler D, Peckham A, Grudniewicz A, Marchildon G. Coordinating primary care services: a case of policy layering. Health Policy. 2019;123(2):215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Starfield B. The future of primary care: refocusing the system. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2087-2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Starfield B. Toward international primary care reform. CMAJ. 2009;180(11):1091-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shortell SM. Bridging the divide between health and health care. JAMA. 2013;309:1121-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta. Scope of Practice for Nurse Practitioners. College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. The King’s Fund. Experience-Based Co-Design. Working With Patients to Improve Health Care. The Kings Fund; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rockwood K, Theou O. Using the clinical frailty scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23(3):254-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S, et al. The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28(4):182-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rose M, Yang A, Welz M, Masik A, Staples M. Novel modification of the Reported Edmonton Frail Scale. Australas J Ageing. 2018;37(4):305-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing. 2006;35:526-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501327211034807 for Customizing a Program for Older Adults Living with Frailty in Primary Care by Jananee Rasiah, Tammy O’Rourke, Brian Dompé, Darryl Rolfson, Beth Mansell, Rachel Pereira, Titus Chan, Karen McDonald and Anne Summach in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jpc-10.1177_21501327211034807 for Customizing a Program for Older Adults Living with Frailty in Primary Care by Jananee Rasiah, Tammy O’Rourke, Brian Dompé, Darryl Rolfson, Beth Mansell, Rachel Pereira, Titus Chan, Karen McDonald and Anne Summach in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-jpc-10.1177_21501327211034807 for Customizing a Program for Older Adults Living with Frailty in Primary Care by Jananee Rasiah, Tammy O’Rourke, Brian Dompé, Darryl Rolfson, Beth Mansell, Rachel Pereira, Titus Chan, Karen McDonald and Anne Summach in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health