Abstract

Background:

Drug promotional literature (DPL) forms a major marketing technique of pharmaceutical companies for propagating information regarding a drug. Many a times, it is the only source on which treating physicians depend for updating their knowledge about the existing and novel drugs.

Aims and Objectives:

This study was conducted to understand the clinicians’ perceptions about DPL and its critical appraisal so that relevant interventions can be made.

Materials and Methods:

It was a cross-sectional questionnaire based study. A self-administered validated questionnaire was administered to 125 clinicians working in a medical college, which sought responses on their perception of various aspects including interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference and decision making based on the DPL which they encounter in their day-to-day practices. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results:

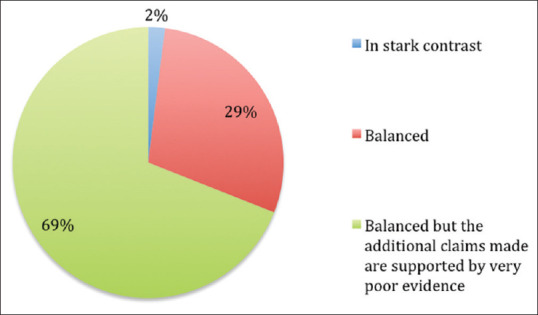

A total of 100 clinicians reciprocated with complete questionnaire. 99% of the clinicians were exposed to pharmaceutical promotional activities and around 79% clinicians accepted that drug promotion has a considerable bearing on their prescribing practices. Majority (79%) of the clinicians felt that the accuracy of the claims in the various forms of DPL was between 50-75%. Amongst the various forms of DPL, brochures were adjudged as the most useful followed by interactions with medical representatives, advertisements in medical journals and direct mailers. a majority of the clinicians (69%) felt that, though the claims in the DPL are balanced but are supported by poor evidence. Around 75% clinicians perceived the primary intention of drug promotional literature was to boost company sales. Around 84% clinicians felt that doctors’ integrity can be compromised by accepting gifts from medical representatives. Over 75% of clinicians believed that training in interacting with medical representatives and assessing other forms of drug promotional literature should be imparted to undergraduates in medical colleges.

Conclusion:

Physicians need to be aware that the pharmaceutical industry may use drug advertisements to influence prescription patterns even when this results in distortion of scientific facts. The pharmaceutical industry should be more responsible and more meticulous in making sure that pharmaceutical claims referring to scientific studies are quoted accurately.

Keywords: Critical appraisal, drug promotional literature, pharmaceutical marketing

INTRODUCTION

In this era of aggressive marketing of pharmaceutical products, promotion plays a critical role. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines drug promotion as “All the information and persuasive activities of manufacturers and distributors, the effect of which is to induce prescription, supply, and purchase and/or use of medicinal drugs.”[1] Pharmaceutical companies use different modes of drug promotions, which include activities of medical representatives (MRs); drug advertisements; provision of gifts and free drug samples to prescribers; drug package inserts; direct-to-consumer advertisements; periodicals; telemarketing; holding of conferences, symposium, and scientific meetings; sponsoring of medical education; and conduct of promotional trials.[2] Pharmaceutical companies spend around one-third of all sales’ revenue on marketing their products, which is twice that spent on research and development.[3] In order to maintain the sales volume, there exists “an inherent conflict of interest between the legitimate business goals of manufacturers and the social, medical, and economic needs of providers and the public to select and use the drugs in the most rational way.”[3]

Drug promotional literature (DPL) forms a major marketing technique of pharmaceutical companies for propagating information regarding product name, its pharmacological characteristics, price, marketing claims, and references cited in support of these claims. Many a time, it is the only source on which the treating physicians depend for updating their knowledge about the existing and novel drugs.[4] DPL can be highly instructive when the information provided by them is authentic, provided it has been critically appraised and reviewed.[5] However, there is evidence that prescribers using DPL as the primary source of new information tend to prescribe less appropriately, leading to irrational use of medicines.[6]

There are universally applicable baseline standards coded by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations for marketing practice, which are to be complied with, during promotional communications. In India, promotional activities by pharmaceutical companies are governed by the Organization of Pharmaceutical Producers of India, Self-regulatory Code of Pharmaceutical Marketing Practices, January (2007), and by national legislation, which includes the Drug and Cosmetics Act, 1940, and the Drugs and Magic Remedies Act, 1954.[7] However, many studies have illustrated that information disseminated through drug advertisements is inconsistent with the code of ethics.[8] References are often cited in support of the claims, in order to increase the credibility and authenticity, but studies have shown that these claims may be misleading, distort the reporting of scientific data or fail to provide enough information to accurately interpret the data they present.[9] The prescriber must be able to comprehend the pharmaceutical promotional ploys in a meticulous manner. Various studies indicate that very few physicians are equipped with the necessary skills, patience, and knowledge to critically assess the information delivered in DPL.[10]

Previous literature has also focused on the provision of samples, gifts, and invitations to company-sponsored programs to doctors.[11] They have the potential to bias the judgment of clinicians and are associated with increased prescribing of new medicines[12,13], which might not necessarily be the most appropriate choice in all cases, also unnecessarily adding to the cost of treatment. The lack of stringent guidelines in our country makes it particularly important that individual clinicians critically analyze the promotional material of the drugs in concurrence with the growing popularity of evidence-based medicine before prescribing the drug to the patient population.[14] Hence, this study was conducted to understand the clinicians’ perceptions about DPL and its critical appraisal so that relevant interventions can be made.

METHODOLOGY

This is a cross-sectional study in which a questionnaire was used, after approval from the institutional ethics committee.

A self-administered validated questionnaire was administered to 125 clinicians working in a teaching hospital in Pune, Maharashtra, India. The questionnaire sought responses from the clinicians on their perception of various aspects including interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, and decision-making based on the DPL which they encounter in their day-to-day practices. The responses were anonymous. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

A total of 100 clinicians completed the questionnaires, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics (n=100)

| Characteristics | Number of participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Broad specialty | |

| Medical | 65 (65) |

| Surgical | 28 (28) |

| Other | 7 (7) |

| Age (years) | |

| 30-40 | 50 (50) |

| 40-50 | 36 (36) |

| 50-60 | 14 (14) |

| Professional experience | |

| <7 | 5 (5) |

| 8-15 | 49 (49) |

| 16-25 | 28 (28) |

| >25 | 18 (18) |

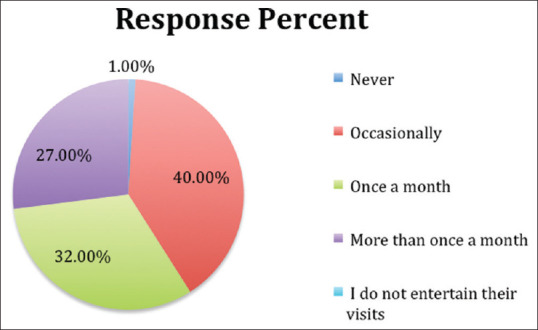

Out of the 100 clinicians, all except one clinician (99%) reported encountering drug promotional activities in some form of the other during their clinical practice [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Exposure of clinicians to pharmaceutical promotional activities

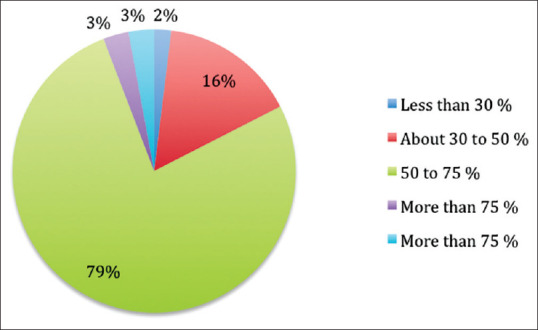

Further, a majority (79%) of the clinicians felt that the accuracy of the claims in the various forms of DPL was between 50% and 75% [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Accuracy of claims made by pharmaceutical companies

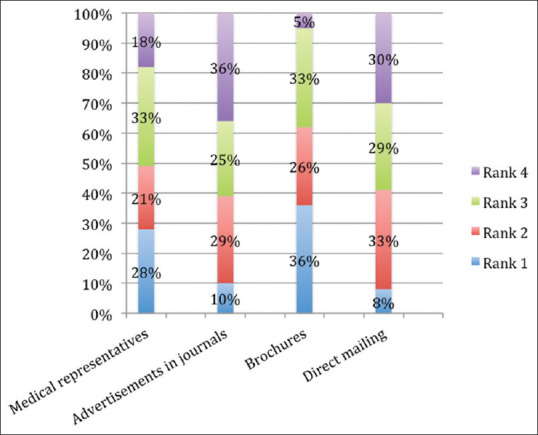

Among the various forms of DPL, brochures were adjudged as the most useful followed by interactions with MRs, advertisements in medical journals, and direct mailers [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Usefulness of various means of drug promotions

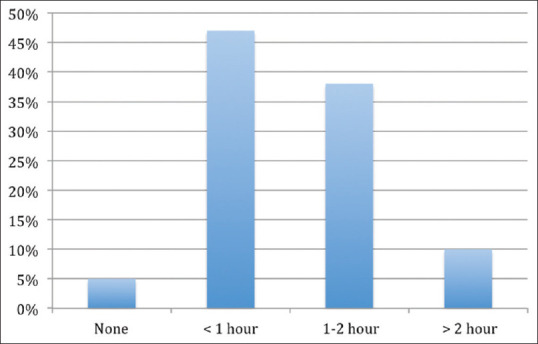

Moreover, as depicted in Figure 4, a majority (95%) reported spending time in researching about the drugs after exposure to a DPL, with the time varying from <1 h (47%) to >2 h (10%).

Figure 4.

Time spent by clinicians researching the drugs after their promotion

Further, most of the clinicians (69%) felt that, although the claims in the DPL are balanced, they are supported by poor evidence [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Evaluation of claims made in drug promotional literature

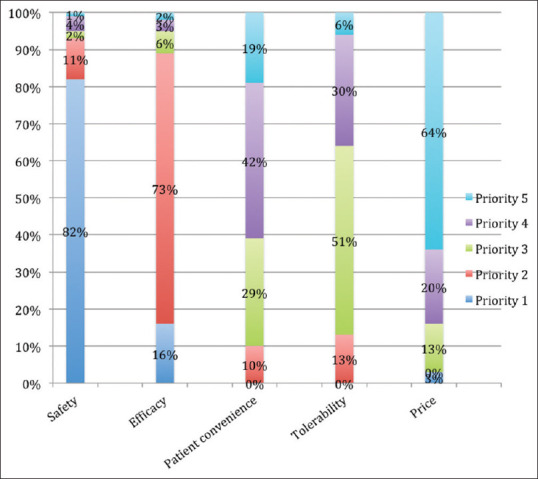

The importance of various parameters about a drug on prescribing was also studied. It was found that before prescribing, safety of the drug was the prime factor considered by the clinicians followed by its efficacy, tolerability, patient convenience, and price [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Priority of factors considered by clinicians before drug prescription

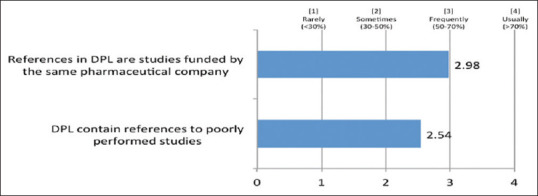

A large percentage of the clinicians (71%) felt that a majority of references in DPL are studies funded by the same pharmaceutical company, whereas around 84% of the clinicians stated that DPL contain references to poorly performed studies [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Perception of clinicians regarding references in drug promotional literature

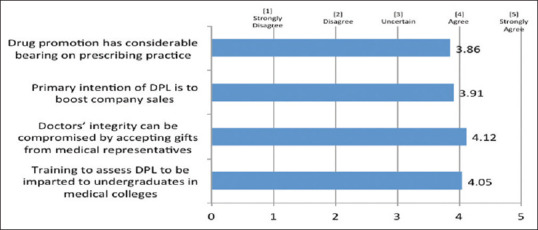

Around 75% of the clinicians perceived that the primary intention of DPL was to boost company sales. The study also examined the influence of DPL on the decision-making of the clinicians, and around 79% of the clinicians accepted that drug promotion has a considerable bearing on their prescribing practice. Furthermore, around 84% of the clinicians felt that doctors’ integrity can be compromised by accepting gifts from MRs. Over 75% of the clinicians believed that training in interacting with MRs and assessing other forms of DPL should be imparted to undergraduates in medical colleges [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Influence of drug promotional literature on prescribing practices and perceived need for training in drug promotional literature

DISCUSSION

DPL are a source of information about the novel drugs or newer implications of using the existing drugs. In our study, majority of the clinicians (99%) were exposed to DPL at least once every month; similar observations were made in other studies,[15] which proposes the assertiveness of direct-to-physician pharmaceutical promotions. A majority of the clinicians believed that drug promotion has a considerable bearing on their prescribing practices, concurring with other studies.[16] This further enhances the importance of critically evaluating these DPL by the prescribing clinicians.

It is significant to note that in our study, a majority of the clinicians seemed to realize that that drug promotions are conducted with the primary motive of increasing drug sales and not for educating the health professionals. The result of this study will help clinicians to critically examine the DPL and ensure that they are not easily swayed by the claims of the pharmaceutical companies. Further, according to our study, more than 3/4th of the clinicians claimed that 50%–75% of the claims are accurate, which is similar to the findings observed by Villanueva et al.[17]

Based on the perception of the usefulness of DPL, most clinicians believed that brochures were most useful followed by interactions with the MRs, whereas drug advertisements and direct mailing were not perceived to be useful. Brochures usually contain comprehensive information about the drug being promoted including detailed data about indications, contraindications, precautions, and adverse effects. This is the reason why clinicians tend to rank them higher as compared to other means of drug promotion. However, the promotional brochures may often contain misleading and unbalanced information, which cannot be relied on solely by the practicing health-care providers.[18] Communication with MRs was also considered to be quite useful as most of the time, MRs seem to have exhaustive knowledge about the drugs and can elucidate clinicians’ queries. It is not surprising that the advertisements were ranked lowest as they are frequently sketchy and comprise vague terms such as “most efficacious” and “highly safe,” with their main objective being increasing the drug sales.

It is also quite heartening to observe that more than 95% of the clinicians in our study spent time in researching the information provided by DPL. This could be because the study was conducted in a tertiary care academic setup with undergraduate and postgraduate teaching ally center. However, around 47% of the clinicians reported devoting <1 h for this activity, which might not be sufficient in case of totally new drugs, new classes, and guideline-based research.

Out of the various parameters, for most clinicians, safety of the drug was the most important factor considered while prescribing followed by its efficacy, tolerability, patient convenience, and price. Surprisingly, it was observed from previous studies that the claims in 70% of the cases laid emphasis on the efficacy and superiority while clinically relevant safety outcomes were negligibly (1%) highlighted.[19,20] Hence, clinicians are forced to explore elsewhere in order to fill in the inadequate information. The fact that the safety of the drug has been prioritized topmost, expresses the ethical concerns of nonmaleficence on the part of clinicians. In our study, clinicians rated drug cost to be of lower influence, which is consistent with other studies.[21] Cost seemed to be only moderately influential when comparing medications; interventions to increase the awareness of cost may have only limited effect in changing the prescribing pattern. This factor may not be of much importance in government hospitals, where medications are provided free of cost, but may add to the overall financial burden on the society and patient care in private hospitals. As per the WHO, rational drug use requires that patients receive medicine appropriate to their needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements, for an adequate period of time and at lowest cost to them and the community.[22] India being a resource-poor country, it is important that clinicians should be mindful regarding the financial limitations on the part of the patient and should be acutely aware of optimum resource management.

In our study, we observed that many clinicians realized that references in DPL are studies funded by same pharmaceutical company and DPL frequently contain references to poorly performed studies.[23,24] Reference citation is usually done to earn credibility. A large number of the references, which are cited to increase the credibility of the DPL, were found to be unjustified when they are critically analyzed.[23] Even if the citations are provided, these are from unpublished data and not peer-reviewed references.[24] The DPL may contain various marketing claims with references, which at times may be inadequate, deceptive, and of poor educational value. Given the potential for misinterpretation, health-care professionals should be able to examine the cited reference to determine whether the manufacturers’ claims are justified.[25]

Pharmaceutical companies should make an effort to quote standard references with higher strength of evidence which can be easily accessible to the clinician. In addition to providing information, pharmaceutical representatives can employ persuasive techniques that aim to influence doctors such as reciprocity acts through provision of gifts which include drug samples, stationery, personal gifts, invitation to launches of products, symposia, or educational events. Conferring from our study, around 84% of the clinicians state that doctors’ integrity can be compromised by accepting gifts from MRs. Various studies also direct that the provision of gifts may create indebtedness[13] that may result in inappropriate changes in prescribing drugs.[26]

Majority of the clinicians strongly believed that training in interacting with MRs and assessing other forms of DPL should be imparted to undergraduates in medical colleges, which is possibly not done adequately in the current curriculum. Appropriate curriculum of future health professionals is crucial to get them to play their role as clinicians, in making or influencing drug-related decisions in the face of medication promotion as well as to prepare them for ethical interaction with drug companies or MRs as per the WHO guidelines.[27] In this regard, the Medical Council of India has incorporated the critical evaluation of the DPL in the new curriculum, which is likely to train the undergraduate students regarding the same.[28]

Clinicians may lack expertise to accurately assess the quality of information granted by pharmaceutical promotions. This concern regarding critical appraisal skills has led to several initiatives to train doctors in scrutinizing information on medicines.[29,30] The WHO and the Health Action International have collaborated to produce a manual that provides practical training for medical and pharmacy students to recognize a variety of promotional techniques.[29] The US Food and Drug Administration introduced a “Bad Ad Program” that educates health-care professionals to recognize misleading or inaccurate promotions and report them to the agency.[30] These programs are essential to encourage health professionals to be skeptical about medical information provided by commercial sources.

CONCLUSION

DPL is an invaluable source of information and can serve to advance the knowledge of the busy clinicians, helping them to remain abreast of the latest developments in the medical field. However, clinicians need to be aware that the pharmaceutical industry may use drug advertisements to influence prescription patterns even when this results in the distortion of scientific facts. To this end, physicians should empower themselves and critically appraise all DPL to ensure that they can segregate the wheat from the hay and strive to achieve the highest standards of rationality in the treatment they provide to the patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Venkat Shashidhar, a medical student, for helping in preparing some of the tables and figures in the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Criteria for Medicinal Drug Promotion, World Health Organization. Endorsed by the 33rd World Health Assembly. Resolution No. WHA21.41. Criteria for Medicinal Drug Promotion, World Health Organization. 1986. May, [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 04]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js16520e/6.html .

- 2.Lal A. Pharmaceutical drug promotion: How it is being practiced in India? J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:266–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trade, foreign policy, diplomacy and health, World Health Organization. [Last accessed on 2019 Ma 04]. Available from: http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story073/en/#main .

- 4.Phoolgen S, Kumar SA, Kumar RJ. Evaluation of the rationality of psychotropic drug promotional literatures in Nepal. J Drug Discov The. 2012;2:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper RJ, Schriger DL, Wallace RC, Mikulich VJ, Wilkes MS. The quantity and quality of scientific graphs in pharmaceutical advertisements. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:294–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Understanding and Responding to Pharmaceutical Promotion-Health Action International. Haiweb.Org. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 05]. Available from: http://haiweb.org/what-we-do/pharmaceutical-marketing/guides/

- 7.Indiaoppi.Com. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 05]. Available from: https://www.indiaoppi.com/sites/all/themes/oppi/images/OPPI-Code-of-Pharmaceutical-Practices-2012.pdf .

- 8.Mali SN, Dudhgaonkar S, Bachewar NP. Evaluation of rationality of promotional drug literature using world health organization guidelines. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:267–72. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.70020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villanueva P, Peiró S, Librero J, Pereiró I. Accuracy of pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals. Lancet. 2003;361:27–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shetty VV, Karve AV. Promotional literature: How do we critically appraise? J Postgrad Med. 2008;54:217–21. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.41807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groves KE, Sketris I, Tett SE. Prescription drug samples – Does this marketing strategy counteract policies for quality use of medicines? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2003;28:259–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2003.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: Is a Gift Ever Just a Gift? Obstetrica Gynecol Survey. 2000;55:483–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marco CA, Moskop JC, Solomon RC, Geiderman JM, Larkin GL. Gifts to physicians from the pharmaceutical industry: An ethical analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:513–21. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lexchin J. Enforcement of codes governing pharmaceutical promotion: What happens when companies breach advertising guidelines? Can Med Assoc J. 1997;156:351–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaki NM. Pharmacists’ and physicians’ perception and exposure to drug promotion: A Saudi study. Saudi Pharm J. 2014;22:528–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khakhkhar T, Mehta M, Sharma D. Evaluation of drug promotional literatures using World Health Organization guidelines. J Pharm Negative Results. 2013;4:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villanueva P, Peiró S, Librero J, Pereiró I. Accuracy of pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals. The Lancet. 2003;361:27–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardarelli R, Licciardone JC, Taylor LG. A cross-sectional evidence-based review of pharmaceutical promotional marketing brochures and their underlying studies: Is what they tell us important and true? BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lankinen KS, Levola T, Marttinen K, Puumalainen I, Helin-Salmivaara A. Industry guidelines, laws and regulations ignored: Quality of drug advertising in medical journals. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:789–95. doi: 10.1002/pds.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutknecht DR. Evidence-based advertising? A survey of four major journals. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denig P, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Zijsling DH. How physicians choose drugs. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:1381–6. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santiago MG, Bucher HC, Nordmann AJ. Accuracy of drug advertisements in medical journals under new law regulating the marketing of pharmaceutical products in Switzerland. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:61. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randhawa GK, Singh NR, Rai J, Kaur G, Kashyap R. A critical analysis of claims and their authenticity in Indian drug promotional advertisements. Adv Med. 2015;2015:469147. doi: 10.1155/2015/469147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Othman N, Vitry A, Roughead EE. Quality of pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carandang ED, Moulds RF. Pharmaceutical advertisements in Australian medical publications – Have they improved? Med J Aust. 1994;161:671–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibbons RV, Landry FJ, Blouch DL, Jones DL, Williams FK, Lucey CR, et al. Acomparison of physicians’ and patients’ attitudes toward pharmaceutical industry gifts. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:151–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ethical Criteria for Medicinal Drug Promotion. World Health Organisation. 1988. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 05]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/whozip08e/whozip08e.pdf .

- 28.Medical Council of India; Competency based undergraduate curriculum. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 04]. Available from: https://www.mciindia.org/CMS/information-desk/for-colleges/ug-curriculum .

- 29.Health Action International. Understanding and Responding to Pharmaceutical Promotion-A Practical Guide. Netherland: HAI. 2010. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 04]. Available from: http://www.haiweb.org/11062009/drug-promotion-manual-CAP-3-090610.pdf .

- 30.Food and Drug Administration. ‘Bad Ad Program’ to help health care providers detect, report misleading drug ads. USA: FDA. 2010. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 04]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm211611.htm .