Abstract

Polyphosphate salts, such as sodium hexametaphosphate (PPi), are effective in the attenuation of collagenase and biofilm production and prevention of anastomotic leak in mice models. However, systemic administration of polyphosphate solutions to the gut presents a series of difficulties such as uncontrolled delivery to target and off-site tissues. In this article a process to produce PPi-loaded poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) hydrogel nanoparticles through miniemulsion polymerization is developed. The effects of using a polyphosphate salt, as compared to a monophosphate salt, is investigated through cloud point measurements, which is then translated to a change in the required HLB of the miniemulsion system. A parametric study is developed and yields a way to control particle swelling ratio and mean diameter based on the surfactant and/or initiator concentration, among other parameters. Finally, release kinetics of two different crosslink density particles shows a sustained and tunable release of the encapsulated polyphosphate.

Keywords: drug delivery, hydrogel nanoparticles, miniemulsion polymerization, phosphate salts, polymerization reaction engineering

1. Introduction

The human intestinal flora consists of numerous symbiotic and opportunistic micro-organisms. Routine injury to the intestinal tract may lead to loss of normal microbiota. In these situations, the gastrointestinal tract becomes a hostile and nutrient-scarce environment which activates colonized hospital pathogens to express virulent phenotypes and cause life-threatening inflammation, in a process commonly known as sepsis.[1-3] Currently, the treatment to prevent proliferation of such pathogenic bacteria is through oral supplementation of antibiotics.[6,7] However, this practice often leads to further complications as this results in the elimination of normal intestinal microbiota and its replacement with multi-drug resistance and potentially virulent associated pathogens.[7]

Several studies from the Alverdy group[1-3] have shown that local depletion of phosphate nutrients is one of the main cues that triggers bacterial transition to virulence and that the maintenance of phosphate abundance in the post-surgical intestinal tract attenuates virulence expression and collagenase activity of certain pathogens.

Investigation into the administration of polyphosphate salt, such as sodium hexametaphosphate (PPi), demonstrated significant in vitro attenuation of collagenase and biofilm production as well as swimming and swarming motility of gram-negative pathogens (S. marcescens and P. aeruginosa) while supporting their normal growth.[7] However, the systemic administration of aqueous phosphate solutions to the GI tract is susceptible to rapid clearance, loss of availability in the colon, with excessively high dosages for increasing its local delivery result in impaired kidney functions.[7] Therefore, there is a need for development of carrier systems that enable localized delivery of extracellular phosphate to the GI tract in a way to fully replenish phosphate levels in a controlled and sustained manner.

Controlled delivery of therapeutics from nanoparticles provides a promising approach for maintaining a phosphate-rich environment required for attenuation of bacterial phenotypes that complicate healing, such as collagenase and virulence expression. Our group has focused on the production of nanoparticles composed of a polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA)–n-vinyl pyrrolidone (NVP) crosslinked hydrogel matrix encapsulated with phosphate salts and synthesized using an inverse miniemulsion polymerization process.[8-10] Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-coated nanoparticles, or PEGylated nanoparticles have demonstrated significant promise in drug delivery research as their surface does not promote non-specific tissue binding while allowing for deeper penetration and longer circulation times especially in mucosal tissues.[11,12] However, it must be noted that in these prior studies the nanoparticles investigated were composed of different material structures (linear polymers[11] or crystalline materials [12]) and subsequently surfacecoated with PEG. The development of crosslinked hydrogel PEG nanoparticles for drug delivery applications is rare.

In previous studies[8-10] we have developed and tested several variants of phosphate-loaded PEG hydrogel nanoparticles (NP). Specifically, we have studied two formulations, one using a monophosphate salt, potassium phosphate monobasic (NP-Pi),[8] and another with a polyphosphate salt that was proven more efficient in vitro,[9,10] sodium hexametaphosphate (NP-PPi). As the NP-Pi particles were tested and characterized, they showed good encapsulation of the phosphate salt and a slow and controlled phosphate release over time. Furthermore, in vitro studies showed the effectiveness of these particles in controlling virulence expression in gram-negative bacteria.[9]

The production of PPi-loaded nanoparticles through inverse miniemulsion polymerization was initially formulated similarly to the NP-Pi production process after accounting for differences in solubility and molecular weight of the two salts.[9] However, the process was found to lack reproducibility. A significant batch-to-batch variability was observed when dealing with the new formulation. The PPi salt, as its name suggests, is a larger and more complex molecule with six phosphate ions, which are known to be strong structure-forming ions in water.[13] In a previous study, we were able to show how such a property can affect the polymerization kinetics of water-soluble monomers, such as NVP.[14]

In fact, a change in the molecular structure of water could have major implications on the stability of miniemulsion polymerization systems and could be the main cause of the observed reproducibility issues. The effect of added salts in the cloud point of nonionic surfactant has been extensively studied[15-22] and a lower surfactant cloud point would be intrinsically connected with a loss of emulsion stability. Previous research by Schott et al.[17] showed that depending on the salt added, the cloud point would either increase or decrease, in phenomena that became known as “salting-in” or “salting-out”, respectively, and that phosphate salts were one of the strongest salting-out agents. Furthermore, follow-up studies[18] proved that the “salting effect is mainly due to the prominent influence of the anions as compared to that of the cations.”

Besides, studies by Shinoda et al.[19] and by Florence et al.[20] looked at how the addition of inorganic salts would influence the HLB of an emulsion system. The Hydrophilic–Lipophilic Balance, or HLB, is a classification system developed by ICI Americas INC. to assign to an emulsifier an expression of the balance of strength and size between its hydrophilic and lipophilic groups.[24] Their results showed that salts that tend to salt-out the surfactants lower the HLB value of the surfactant and, therefore, increase the required HLB to of the emulsion, giving it a way to counteract the salting-out effect. However, even though it has been reported that a decrease in cloud point causes an increase in the required HLB of the system,[19-22] no explicit mathematical correlation exists between the two, to the knowledge of the authors.

Therefore, we herein present our efforts to design a reproducible formulation through the exploration of various saltrelated effects, such as surfactant cloud point and change in the “required HLB” of the emulsion, and conducting a parametric study aimed at understanding the effect of process variables on the production of NP-PPi. Once formed, the particles were characterized by mass recovery yield of nanoparticles, but mainly by particle swelling ratio and particle size distribution. Finally, we look at release kinetics of two different formulations to confirm the suitability of these for sustained phosphate ion delivery.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Inhibited 1-Vinyl-2-pyrrolidone >99%, inhibited poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (575 Da), potassium persulfate (KPS) >99%, Tween 20, SPAN 80 and sodium hexametaphosphate crystalline, +200 mesh, 96% were bought from Sigma Aldrich. Potassium phosphate monobasic, ACS, crystals, cyclohexane 99%+ and 2,2,-Azobis(2-methylpropionamidine)dihydrochloride (V-50) 98% were bought from Acros Organics. Sodium Chloride, >99.5% and acetone, HPLC grade were bought from Fisher Chemical. 2,2′-Azobis[2-(2-imidazolin-2-yl)propane]dihydrochloride (VA-044) was bought from Wako Chemicals and 2,2′-Azobis(2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile) (V-65) was bought from Fujifilm. Sodium hexametaphosphate, potassium monophosphate, Tween 20, SPAN 80, KPS, V-50, VA-044, V-65, and the solvents cyclohexane and acetone were used as received. The NVP was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter to remove the sodium hydroxide inhibitor present, while the PEGDA was passed through an inhibitor removal column to remove the hydroquinone monomethyl ether (MEHQ) inhibitor.

2.2. Cloud Point Experiments

For cloud point measurements, 15 mL Eppendorf tubes were prepared with 10 mL of DI water, a tween concentration of 0.024 mm, based on previous research[9] and varying concentration of Pi, PPi, or NaCl. The tubes were then immersed in a water bath programmed with an increasing temperature protocol, with a thermometer measuring the water bath temperature. The water bath temperature at which each individual tube first turned “cloudy” was recorded. After all the tubes had turned “cloudy” they were individually taken out of the water bath and put in an ice bath to cool down with a thermometer measuring the temperature inside the tube. The temperature at which the tubes started clearing out (stopped being “cloudy”) was then recorded. This was believed to be a more accurate measurement of the cloud point temperature for each tube. If the “clouding” temperature from heating up and cooling down diverged by a big margin, a second heating up cloud point was obtained, this time with the thermometer measuring the temperature inside each individual tube.

2.3. Nanoparticle Production Process

2.3.1. Emulsion Phase Precursors

The aqueous precursor consisted of a solution of 282 mm of the crosslinked agent PEGDA, 121 mm of the co-monomer NVP, and 50 mm of the encapsulated salt, sodium hexametaphosphate (PPi). To this solution, varying amounts of the aqueous phase surfactant Tween 20 and of different azo-type initiators were added depending on the desired formulation. Previous studies in the group have used potassium persulfate (KPS) as the initiator for producing hydrogel nanoparticles.[8] However, recent studies[14] have shown that KPS is not effective in initiating aqueous-phase solutions of NVP and various literature studies stated that a water-soluble azo-initiators are more recommended for these types of applications. The precursor volume was then always filled up to 16.5 mL with DI water.

The organic phase consisted mostly of cyclohexane. Depending of the desired formulation, different amounts of the oil-phase surfactant Span 80 were added to the cyclohexane solution. The volume of the organic phase was generally kept at 250 mL, even though some formulations used 300 mL.

2.3.2. Emulsification and Reaction

After both precursors were prepared, the oil-phase precursor was put in ice bath before being homogenized using a rotor–stator homogenizer with a 10 mm saw-tooth generator (IPRO 250, Pro-Scientific) at 20 000 rpm. The water phase precursor was then slowly pipetted into the oil-phase precursor and the emulsion formed was homogenized for 15 min in an ice bath.

The emulsion was then sonicated using an ultrasonic horn (SONICS Vibracell VCX750) for five cycles of 1 min at 90% amplitude, with a 30 s interval between them to ensure that the emulsion temperature did not go over 15 °C. Temperature control is important at this step to prevent pre-polymerization of the monomers.

The formed miniemulsion was then transferred to a glass reactor vessel. The reactor was set up as a stirred batch reactor as can be seen in Scheme 1. An oil bath was used to heat up and control the reactor temperature. A nitrogen blanket was necessary throughout the reaction to prevent oxygen inhibition. A condensation column was also attached to prevent cyclohexane loss due to the constant flow of nitrogen.

Scheme 1.

Miniemulsion polymerization reactor setup.

After the miniemulsion was added to reaction vessel, it was bubbled with nitrogen for 45 min to remove any oxygen that might inhibit the reaction. The vessel was then lowered into the already hot oil bath and let react. Reaction time, as well as reactor temperature and stirring speeds, were adjusted throughout the experiments and changed depending of the formulation used.

2.3.3. Purification

Once the reaction time was reached, the reaction setup was broken down and the emulsion containing the polymeric nanoparticles was transferred into a 500 mL jar. The emulsion was then added with ≈150 mL of acetone for particle precipitation, before the mixture was put in the fridge and left overnight. The next day, a layer of precipitated particles could be seen in the bottom of the vial. The liquid supernatant on top was discarded through decantation and another 120 mL of acetone were added to the precipitated particles. The mixture was then sonicated at 90% amplitude until all agglomerates were broken and complete re-suspension of the nanoparticles in acetone was achieved (≈20 s). The suspension was centrifuged at 3220 × g and 4 °C for 90 min. Following centrifugation, a second cycle of removal of the supernatant, addition of 120 mL of acetone and centrifugation at 3220 × g and 4 °C for 90 min was done. Upon removal of the supernatant after the end of the second cycle, the rinsed particulate material was dried under vacuum for 48 h. Fully dried agglomerates were transferred to a mortar and crushed with a pestle into a fine white powder. The produced nanoparticles were stored dry at room temperature.

2.4. Particle Characterization

2.4.1. Mass Recovery Yield

After purification, drying, and gridding, the particles were collected in a weighting paper and the final particle mass weighted. The nanoparticle mass recovery yield was calculated based on the amount of monomer and solids added to the precursor, according to Equation (1). The other components of the precursors are assumed to be removed through the purification process.

| (1) |

2.4.2. Swelling Ratio

In order to obtain the swelling ratios of the different particles produced, 1.5 mL of DI water was added to 20 mg of nanoparticles and vortexed for mixing. The mix was then allowed to sit on the counter for 48 h at room temperature. After which, the nanoparticle solution was centrifuged and the supernatant was removed through decantation followed by removal of the last droplets with a paper wipe. The weight of the wet nanoparticles was then measured and the swelling ratios were calculated by dividing the wet weight by the dry weight originally added to the tube.

2.4.3. Particle Size Distribution

Particle size distribution was measured using a nanosizer (NanoSight LM10, Malvern, UK) equipped with nanoparticle tracking analysis software (NanoTracking v 3.0). 1 mg of nanoparticle mass was added to 1 mL of DI water in a 2 mL eppendorf tube and then diluted 100 times. In case the nanoparticle concentration was too high, a more dilute solution was made. The nanoparticle solution was then run through the nanosizer and three 60 s videos were recorded and pooled to determine particle size distributions and nanoparticle diameter.

2.5. Release Kinetic Experiments

Release kinetics experiments for PPi release from the nanoparticles were done under perfect sink conditions and at 37 °C to simulate body temperature. A solution of 10 mg mL−1 of dry nanoparticles in water was produced and put it in the incubator at 37 °C. At the desired time of measurement, the solution was taken out of the incubator, centrifuged at 3000 rcf for 30 s so the particles would precipitate and 10 uL of the supernatant were taken out and added to 1 mL of a phosphate detection solution, according to the instructions of the kit (need name). The phosphate concentration was determined via absorbance at 340 nm using a SpectraMax 190 Microplate Reader and making use of a standard calibration curve. The nanoparticle solution was then replenished with 10 uL of water, vortexed for re-mixing and incubated at 37 °C until the next sampling point.

3. Results and Discussion

This section first presents an exploration of the effects associated with the added salts and surfactants on the emulsion characteristics, followed by a parametric study aimed at achieving process improvements to produce stable nanoparticle emulsions.

3.1. Effect of Phosphate Salts on Tween 20 Cloud Point

A solution of TWEEN 20, the water phase surfactant, at the same concentration used in the water precursor, was supplemented with different salt concentrations. As seen in Figure 1, both Pi and PPi significantly affect the cloud point of TWEEN 20. Sodium chloride was also tested and used as a reference for comparison. Figure 1 also clearly shows that the polyphosphate salt has a more drastic effect on the cloud point than the monophosphate salt. For example, small increases in PPi concentration of about 0.1 m cause a drop in the cloud point of more than 10 °C. The differences in magnitude of the effects of PPi and Pi explain why the switch from one salt to the other becomes challenging.

Figure 1.

a) Cloud point (°C) of aqueous solutions of Tween 20 as a function of molar salt concentration for the two different salts studied, Pi (■) and PPi (•), and for NaCl (▲), b) expanded view of the cloud point curves with the two operating points for the production processes for the Pi-loaded (+) and PPi-loaded (*) nanoparticles, are included. Arrows are added to help show the difference between both operating points and the cloud points of Pi and PPi at that specific molar concentration.

The effect seen in Figure 1 can be explained by the higher degree of order in the water molecules induced by the presence of additional phosphate ions in solution. As observed in previous studies,[14] the presence of high concentrations of these ions in solution can lead to a more defined water structure, causing a weaker interaction between water and surfactant molecules. As that interaction decreases, so does the potential of the surfactant to stay in solution, eventually coming out of solution at a lower molar salt concentration. As for the miniemulsion system, a weaker interaction between surfactants and the water molecules will clearly lead to a less stable system. Based on these experiments and previous published studies,[17-22] it is clear that the higher concentration of phosphate ions in solution causes a stronger salting-out effect, lowering the cloud point of the surfactants, and making the miniemulsion system less stable.

In previous studies, we have successfully prepared Pi-loaded nanoparticles using a 0.086 m concentration of Pi.[8] Figure 1b shows that the measured cloud point at these conditions is approximately 93 °C, which is almost thirty degrees higher than the reactor operating temperature of approximately 64 °C. Noting that the cloud point measured here is only for an aqueous solution of TWEEN 20 and salt, one should expect the actual cloud point of the complete aqueous precursor to be lowered even further. If the same molar concentration is used for PPi in our experiments, the measured cloud point, according to Figure 1b, would be approximately 80 °C and could possibly lead to salting out under reaction conditions. We have thus decided to limit the PPi concentration to 0.045 m (yielding a measured cloud point of ≈88 °C) in order to avoid this phenomenon when producing NP-PPi. This concentration is still significantly higher than the concentration shown to be effective in attenuating virulence and collagenase in vitro, proving to be a good value for our sustained release particles. Lower PPi concentrations were also tested but had low stability due to a weaker lipophobe effect to prevent Ostwald ripening.[23]

3.2. Effect of Phosphate Salts on the Hydrophilic–Lipophilic Balance of the Emulsion

In order to test the required HLB of the system (the HLB value at which the emulsion is the most stable), a screening experiment was conducted where small-scale inverse miniemulsions (20 mL) were produced with varying ratios of Tween 20/Span 80 while keeping the total surfactant concentration constant. For a mixture of non-ionic surfactants, the HLB can be calculated by the weighted sum of HLBs of each surfactant in the blend. Equation (2) shows how to calculate the HLB of our specific system.

| (2) |

Based on previous experimentation[8] and on literature considerations,[25] we have established the required HLB for the Pi-loaded miniemulsion to be approximately 5. However, after such a strong effect was seen in the cloud point of Tween 20 when switching from Pi to PPi, one could assume that the required HLB of our emulsion system might have been affected as well. Figure 2 shows how the droplet size from the different emulsions changes with the different HLB values. A second order polynomial fit was added simply as a guide.

Figure 2.

Mean droplet size in nanometers as a factor of the miniemulsion hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) value. A second-order polynomial trend line was added to help guide to eye to the approximate minimum in droplet size present between HLB values of 6–7.

In Figure 2, a minimum in the mean droplet size is observed in the range between HLB 6 and 7. Obtaining smaller particles while using the same amount of surfactant indicates more efficient coverage of the nanoparticles by the surfactants, which leads to more stable emulsions. Thus, we could hypothesize that the required HLB of the PPi-loaded emulsion is somewhere between 6 and 7. We elected to use a value of 6.5 for the NP-PPi production and the new formulation significantly improved the reproducibility of the process.

3.3. Parametric Study of the Inverse Miniemulsion NP Production Process

Based on the findings presented in Figure 1 and 2 we developed a base formulation believed to lead to more reproducible operation for the PPi-loaded emulsion system. The formulation details are presented in Table 1. Preliminary experimentation confirmed the expected process improvements. Note that the PPi concentration in Table 1 was selected based on the cloud point measurements of Figure 1. Also note that the used concentrations of SPAN 80 and TWEEN 20 lead to an HLB value of 6.5 based on Equation (2).

Table 1.

Base formulation for PPi-loaded miniemulsion process.

| Phase volume ratio | 1:15 v/v |

|---|---|

| Oil phase precursor | |

| Solvent | Cyclohexane |

| Span 80 concentration | 64 mm |

| Water phase precursor | |

| Tween 20 concentration | 80 mm |

| PPi concentration | 45 mm |

| Total monomer concentration | 0.4 m |

| Initiator concentration | 1% (based on total DB) |

| Initiator type | V-50 |

| Process parameters | |

| Reactor temperature | 64 °C |

| Stirring speed | 10 rpm |

| Reaction time | 4.5 h |

Aiming at gaining a better understanding of the process conditions and parameters on the properties of the emulsion and the nanoparticles produced, eight different parameters were varied throughout the different experiments, namely: HLB, Total Surfactant Concentration, Reaction Time, Reactor Temperature, Initiator Concentration, Initiator Type, Phase Volume Ratio, and Reactor Stirring, accounting for a total of 18 different formulations, as listed in Table 2. In the next sections we present an overview of the results obtained, followed by a more in-depth discussion of the parameters that most affected the emulsion process.

Table 2.

Summary of PPi loaded nanoparticles production formulations tested.

| Formulation Number | HLB | Reaction Time [h] | Surfactant conc [% w/v] | Temperature [°C] | Initiator conc [% DB] | CHx volume [mL] | Stirring | Initiator name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 64 | 1 | 300 | No | V-50 |

| #2 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #3 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #4 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #5 | 6.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #6 | 6.5 | 2 | 5.5 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #7 | 6.5 | 2 | 1.2 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #8 | 6.5 | 2 | 1.75 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #9 | 6.5 | 2 | 1.75 | 64 | 1.5 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #10 | 6.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 64 | 1.5 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #11 | 6.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 64 | 0.5 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #12 | 6.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 69 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #13 | 6.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | VA-044 |

| #14 | 6.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-65 |

| #15 | 7.5 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 64 | 1 | 250 | Yes | V-50 |

| #16 | 7.5 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 64 | 1 | 250 | No | V-50 |

| #17 | 7.5 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 64 | 1 | 300 | No | V-50 |

| #18 | 7.5 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 56 | 1 | 250 | No | V-50 |

3.3.1. Overall Considerations

After production and separation of the particles, the mass recovery yield, particle size, and swelling ratios were measured for each formulation and are plotted in Figures 3-5, respectively.

Figure 3.

Summary of percentage mass recovery yields for all 18 formulations tested. The formulation numbers and parameters are described in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Summary of swelling ratio for all 18 formulations tested. The formulation numbers and parameters are described in Table 2.

Even though the mass recovery yields presented in Figure 3 are highly affected by our separation process it still gave us a good comparison parameter between all the different formulations. Our particle separation process is constrained by the fact that water cannot be used (to avoid the release of salts out of the NP) and the necessity for removing all traces of cyclohexane and SPAN 80 to minimize the cytotoxicity of the NP. As a result, the separation process results in a loss of nanoparticles during separation, which explains the relatively low mass recovery yields (<40%). We are currently in the process of developing a more efficient separation protocol and will report on it in future publications.

We observe from Figure 3 that formulations #2 and #5 result in the highest mass recovery yields. Interestingly, both of these formulations use the base conditions identified in Table 1, except that the reaction time for #5 has been reduced to 2 h. This finding confirms that the conditions determined based on cloud point and HLB are suitable for the emulsion process improvements, and further show that the reaction time used could be shortened without loss of performance.

In a similar way Figure 4 shows that the formulation that had the highest recovery yield, that is, formulation #5, also had one of the lowest particles size. However, with the exception of formulations #5 and #11, which had high recovery yields and low particle size, there does not seem to be a clear trend between the mass of particles recovered and their size.

Figure 4.

Summary of mean particle diameter in nanometers for all 18 formulations tested. The formulation numbers and parameters are described in Table 2.

Figures 4 and 5 also show that by changing the parameters in the formulation we were able to achieve a broad distribution of particle sizes, ranging from 108 to 201 nm, and of swelling ratios, ranging from 3.18 to 6.69. This is probably the most useful result for our application because it gives us a way to reverse-engineer our particles by knowing the necessary particle properties to achieve a desired release profile.

The variations in swelling ratio presented in Figure 5 are intrinsically connected to the polymerization kinetics of the system. Vadlamudi et al.[8] showed that for the synthesis of Pi-NP, the experimentally calculated swelling ratio of the produced particles was directly correlated with their gelation time as predicted by a pseudo-bulk model. The formulations that displayed faster kinetics, and gelled sooner, also resulted in lower swelling ratios, that is, tighter crosslinking. Even though that process made use of KPS as the initiator and Pi as the encapsulated salt, it is fair to assume similar qualitative effects and trends in the NP-PPi system studied here.

Furthermore, Vadlamudi et al.[8] also reported that the presence of surfactants directly affected the initiator efficiency in the miniemulsion system. Higher surfactant concentrations accounted for lower “apparent” initiator efficiency and thus, slower reaction kinetics, which in turn resulted in higher swelling ratios. They offered two hypotheses to explain this effect: 1) “degradative chain transfer and side reactions with the oxidation products of the surfactants” or 2) “the reduced droplet size, caused by the higher surfactant concentrations, leads to a stronger cage effect and an increased rate of radical exit.”

To further investigate these findings, Figure 6 plots the particle size versus swelling ratio for all our formulations which were produced with V-50 as the initiator. Similarly to what was predicted by Vadlamudi et al.[8] Figure 6 shows a general inverse trend/correlation between these two NP properties. In general, we observe that the lower the particle size of particles made with a specific formulation, the higher its swelling ratio will be. While their findings were based on gel time, or faster kinetics, one should note that smaller particles in our work are either obtained because of higher surfactant levels, which by hypothesis 1 leads to a reduction in the “apparent” initiator efficiency, or result from other condition changes. In the latter cases, the confinement effect in smaller particles will also lead to a lower “apparent” efficiency. It is clear form Figure 6 that the relationship between swelling ratio and particle size is not absolute as other factors are at work in the polymerization process, but generally holds within reasonable limits. This general trend will be seen in some of the graphs presented in the following subsections as well where controlled factor effects are discussed.

Figure 6.

Mean particle diameter in nanometers versus particle swelling ratio for all 16 formulations formed using V-50 as the initiator. Data seems to show that there might exist a general correlation between increasing swelling ratios and decreasing particle size.

3.3.2. Effect of Emulsion HLB

In Figure 2, a minimum in droplet size for our system was observed around 6.5. In order to further confirm that, we tested the process with this HLB value and also compared it to results of formulations run at HLB 7.5 (formulations #15–18).

It is important to mention that emulsion formulations with lower HLB values (namely HLB = 4 and 5) were also performed, but (as expected) failed to yield stable and reproducible results. Higher HLB values were not tested since the screening experiments (Figure 2) had already shown that these would be less stable than when using HLB values in the range of 6–8.

Figure 7 shows a comparison between the measured properties of swelling ratio and particle diameter for nanoparticles formed using formulation #2 and formulation #15. The only difference between these two formulations is their HLB values (6.5 for #2 and 7.5 for #15).

Figure 7.

Comparison between similar formulations with an HLB value set to 6.5 (#2) and 7.5 (#15). a) Comparison between the swelling ratio of particles produced with the two formulations, b) Comparison between the particle size in nanometers obtained with the two formulations.

While formulation #2 showed a lower swelling ratio and a higher particle size, neither of these values are significantly different from the values for formulation #15. It is difficult to ascertain whether one of these formulations is better than the other, or even different at all. Looking back to Figure 2, we see that, according to the trend line, we expect the mean droplet size for both of these formulations is similar, so similar particle sizes after polymerization are to be expected. The reversal of the relative direction of these two formulations between emulsion droplets and polymerized NP is probably related to other processes like coagulation and Ostwald ripening. The HLB 7.5 value was not run at a reaction time of 2 h. However, the better mass recovery yield obtained at HLB 6.5 (Figure 3) led us to retain that value for the base formulation. Notice that other formulations (#16–18) at HLB 7.5 either resulted in very low mass recovery or larger particle diameter.

3.3.3. Effect of Total Surfactant Concentration

Different total surfactant concentrations were used based on the total volume of the miniemulsion system, while keeping the ratio between the surfactants constant to yield an HLB of 6.5, in a way to decouple the effect of surfactant concentration and emulsion HLB. Based on previous studies,[8] we decided to use four different total surfactant concentrations, 1.2% w/v, 1.75% w/v (only for 2 h of reaction time), 3.1% w/v and 5.5% w/v.

Figures 8 and 9 show the results of changing the total surfactant concentration on both the swelling ratios and the particle sizes of the produced nanoparticles. The difference between the two figures is only the reaction time.

Figure 8.

Comparison between similar formulations with varying total surfactant concentrations of 1.2% w/v (#4), 3.1% w/v (#2) and 5.5% w/v (#3) for 4.5 h of reaction time. a) Comparison between the swelling ratio of particles produced with the three formulations, b) Comparison between the particle size in nanometers obtained with the three formulations.

Figure 9.

Comparison between similar formulations with varying total surfactant concentrations of 1.2% w/v (#7), 1,75% w/v (#8), 3.1% w/v (#2) and 5.5% w/v (#3) for 2 h of reaction time. a) Comparison between the swelling ratio of particles produced with the four formulations, b) Comparison between the particle size in nanometers obtained with the four formulations.

Very interesting trends can be seen in both of these figures, especially Figure 8. At 4.5 h of reaction time, as expected, we see that an increase in surfactant concentration causes a steady decrease in particle size, and an accompanying increase in swelling ratio. This further agrees with the results from Vadlamudi et al.[8] and from Figure 6, where the increase in surfactant concentration slows down the kinetics of the miniemulsion system because of interference with the radicals and increased confinement in smaller nanoparticles, causing less crosslinked networks to be formed. At 2 h of reaction time, a similar trend is observed for particle size, but not as clearly for the swelling ratio. We should note that in formulation #6, because of the high amount of surfactant used, the particles turned out sticky and aggregated instead of grinding into a fine powder, which might have affected the particle size and swelling ratio measurements. At this shorter reaction time, as well, it is possible that the system is still developing and may have not reached full conversion yet.

Comparison between Figure 8 with Figure 9 seems to indicate that coagulation or Ostwald ripening leads to an increase in particle diameter during the additional 2.5 h of polymerization time. Since this is not accompanied by any considerable increase in mass recovery (Figure 3), we must conclude that the long reaction time is detrimental, and that future work should use a modification of the base formulation of Table 1 where the reaction is stopped after 2 h.

The overall trend of decreasing particle size with increasing surfactant concentration seen in both Figures, however, is expected as higher surfactant concentration should be able to stabilize smaller droplets and, therefore, produce smaller particles. The effect on the swelling ratio is in agreement with an overall trend observed throughout our experiments as shown in Figure 6, where a smaller particle size is generally associated with a lower swelling ratio and a higher crosslink density.

3.3.4. Effect of Initiator Concentration

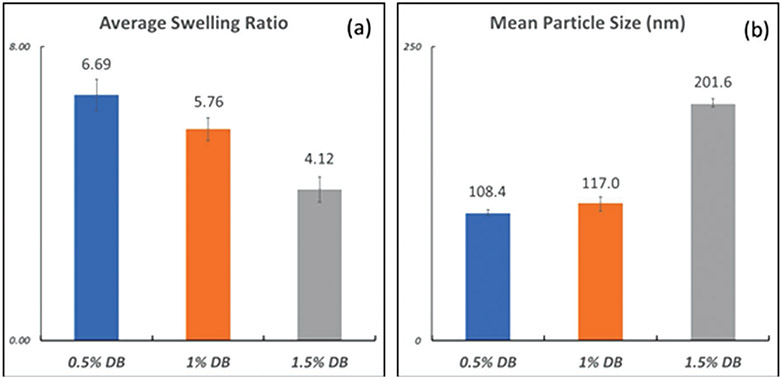

Figure 10 presents results for swelling ratios and particle size obtained at different initiator concentrations. The initiator concentration was based on the amount of double-bonds present in the system. Since the crosslinker PEGDA has two double-bonds per molecule, this value will be different than the total monomer concentration. The previously used[8] value of 1% of the double-bond concentration (DB) was compared with 1.5% DB and 0.5% DB.

Figure 10.

Comparison between similar formulations with varying initiator concentrations of 0.5% double-bond (DB) concentration (#11), 1% DB concentration (#5) and 1.5% DB concentration (#10) for 3.1% w/v of total surfactant concentration. a) Comparison between the swelling ratio of particles produced with the three formulations, b) Comparison between the particle size in nanometers obtained with the three formulations.

We see that the increase in initiator concentration causes a decrease of the particles swelling ratio, or an increase of its crosslink density. The trends in Figure 10 are very interesting as it presents us with a useful way of controlling the crosslink density of the particles. The increase in initiator concentration will lead to the formation of shorter primary chains, and since there is no reason to believe that the composition of these chains (PEGDA/NVP) would be significantly different, this would lead to a higher crosslink density.

The results presented in Figure 10, once again, fall in accordance with the findings of Vadlamudi et al.[8] By increasing the initiator concentration and, therefore, speeding up the reaction kinetics, lower swelling ratios are obtained. Furthermore, the trend observed in Figure 6 also holds true in Figure 10, where higher crosslinked particles, or particles with lower swelling ratios, would also have higher particle sizes.

3.3.5. Other Considerations

In addition to the three parameters investigated in the previous subsections, five other parameters were also varied in the various formulations of Table 1.

Reaction time changes showed no significant improvement in the particle characteristics or the recovery yields by reacting for a longer time.

The reactor temperature value used for the base formulation, 64 °C, was found to be the best operating point from the perspective of product recovery after separation. The particle characteristics showed slight differences. We should also note that at the higher reactor temperature (#12) excessive cyclohexane evaporation and condensation on the reactor walls was observed.

Formulations at lower water phase to oil phase ratio (#17) showed lower particle sizes and lower swelling ratios. With the higher phase ratio formulations (#16), however, we were able to achieve a higher mass recovery of particles.

The necessity of reactor stirring was investigated by comparing a formulation with no stirring (#16) to a formulation with the minimum achievable stirring of 10 rpm (#15). The formulation with no stirring showed slightly higher particle sizes, while no significant difference was observed in the swelling ratios or the recovery yields.

Finally, a couple of different initiators were tested, namely VA-044 (#13), a water-soluble initiator with 10-h half-life at 44 °C, and V-65 (#14), an oil-soluble initiator with 10-h half-life at 51 °C, and compared to a formulation using V-50 (#7), which has a 10-h half-life at 56 °C. Both resulted in more crosslinked particles, but also significantly higher particle sizes, in accordance with the findings of Vadlamudi et al.[8] and the trend of Figure 6. It is important to note, however, that by using these other initiators, we obtained the lowest swelling ratios of the whole study, with the formulation with V-65 (#14) having the lowest swelling ratio of 3.18. This initiator could be used whenever highly crosslinked particles are desirable.

3.4. Phosphate Release Kinetics from PPi-NP

Phosphate release experiments were conducted at 37 °C under perfect sink conditions up to 28 days in order to demonstrate that the particles are effective in releasing the encapsulated polyphosphate salt.

Figure 11 shows the cumulative release from particles produced using formulation, #5. It is clear from Figure 11a that there is an initial burst of release that occurs right after dilution of the nanoparticles. This is probably caused by a high concentration of phosphate salts near or at the surface of the nanoparticles. From Figure 11b, however, it is clear that after the initial burst, a slow and controlled release of PPi is obtained, lasting up to about 20 days. This sustained release of the encapsulated salt is very interesting and the reason why the usage of PEG hydrogel nanoparticles for drug-delivery is promising.

Figure 11.

Percentage of maximum loading released from PPi-NP made using formulation #5 as a function of time for a) the first 24 h and b) 28 days. After the initial burst shown in a), a sustained release of PPi from the NPs is observed up to 20 days. A trend line is used to help guide the eye. Data points exceeding 100% release are observed and attributed to experimental error.

Even though successful sustained release of PPi was shown for formulation #5, various applications could predicate the need for an even slower, and more extended, release profile. We selected a formulation (#8) that produces NPs with a higher crosslink density and quantified its release kinetics at 37 °C over 30 days. Figure 12 gives a comparison between the release from these two formulations.

Figure 12.

Comparison of percentage of maximum loading released from PPi-NP made using formulation #5 and formulation #8 as a function of time in days. Particles produced with formulation #8, which had a lower swelling ratio, show a small initial burst and slower sustained release when compared to particles formed with formulation #5, releasing for up to 28 days compared to 20 days for formulation #5.

Figure 12 shows that formulation #8 also results in an initial burst, but at much lower values, probably because of lower amounts of PPi near the surface of these more tightly crosslinked particles. After the initial burst, as expected, a slower sustained release of the encapsulated salt is seen, only reaching full release at about 30 days.

Figure 12 thus confirms that various release profiles could be achieved by varying the NP production parameters. Knowing the end goal and the release kinetics desired out of the nanoparticles, one can now adjust the production process in order to obtain those desirable NP characteristics. By changing parameters such as the total surfactant concentration or the initiator concentration, for example, one could obtain particles with higher or lower crosslink densities, which would then release the encapsulated material slower or faster. This type of control is crucial in being able to advance the usage of this technology.

4. Conclusions

In this article, we studied the differences associated with encapsulating a polyphosphate salt, sodium hexametaphosphate, and a monophosphate salt, potassium phosphate monobasic, in hydrogel nanoparticles produced through an inverse miniemulsion polymerization system. Besides, we used systematic empirical observations in a parametric study to understand how the different process variables affect the properties of the nanoparticles produced.

Through cloud point measurements, we were able to demonstrate the effect a strong structure-inducing ion such as phosphate ions has on the structure of water and its interactions with the surfactants in solution. The cloud point experiments also showed how stronger this effect is when a hexametaphosphate salt is in solution compared to a monophosphate salt and a simpler salt like sodium chloride. Using literature references, we were able to determine that for a two-surfactant system like ours, the main effect of the observed decrease in cloud point would be in the required HLB of the emulsion. An HLB screening experiment was then designed and the required HLB was found to be 1.5 points higher than for the system with the monophosphate salt. Once the HLB was adjusted, a much more stable and reproducible system for the production of PPi-loaded nanoparticles was obtained.

After a reproducible process had been obtained, a parametric study was developed by using eighteen different formulations and comparing them against each other. By varying different parameters, we were able to achieve a broad range of characteristically different particles, with sizes ranging from 108 to 201 nm and swelling ratios ranging from 3.18 to 6.69. Analysis of the parametric study was able to help us understand how the different process variables affect the system and extend the findings from Vadlamudi et al.[8] to generate a general correlation between faster polymerization kinetics and higher crosslink density and particle size. Parameters that increased the speed of the reaction, such as higher initiator concentration or the use of initiators with faster dissociation kinetics, resulted in lower swelling ratios and higher particle sizes, while parameters that decreased the speed of the reaction, such as higher surfactant concentration, which decreases the initiator efficiency, resulted in higher swelling ratios but lower particle sizes. More importantly, however, the parametric study provided us with a way to better engineer the particles for our specific needs. Knowledge gained in adjustments of parameters that impact physical nanoparticle characteristics such as particle size and swelling ratio allows us to more readily utilize this carrier system for targeted and sustained delivery of different therapeutics for various biomedical applications.

Finally, release kinetics experiments showed a rapid burst of phosphate salts, probably associated with phosphate located at, or near, the particle surface. However, after the initial burst, a sustained and controlled release of the salt is seen to occur until 20 days. For the sake of comparison, release kinetics were quantified for a higher crosslinked particles and showed a similar, but smaller, initial burst, followed by delayed release kinetics and a prolonged period of release for up to about 28 days.

As noted previously, the mass recovery yields never exceeded 40%. This is believed to be primarily due to our separation and purification process. Further studies are being conducted to improve the separation/purification process in order to obtain higher, or complete, recovery of the initial mass of solids. The nanoparticles presented in this work are also currently being tested for their efficacy in preventing bacterial virulence, collagenase and biofilm activity in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant no: 1R21AI124037-01) awarded to Georgia Papavasiliou (PI), Fouad Teymour (Co-I)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Fernando T. P. Borges, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL 60616, USA

Georgia Papavasiliou, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL 60616, USA.

Fouad Teymour, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL 60616, USA.

References

- [1].Zaborin A, Romanowski K, Gerdes S, Holbrook C, Lepine F, Long J, Poroyko V, Diggle SP, Wilke A, Righetti K, Morozova I, Babrowski T, Liu DC, Zaborina O, Alverdy JC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 6327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Romanowski K, Zaborin A, Valuckaite V, Rolfes RJ, Babrowski T, PLoS One 2012, 7, e30119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zaborin A, Gerdes S, Holbrook C, Liu DC, Zaborina O, Alverdy JC, PLoS One 2012, 7, e34883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shogan BD, Belogortseva N, Luong PM, Zaborin A, Lax S, Bethel C, Ward M, Muldoon JP, Singer M, An G, Umanskiy K, Konda V, Shakhsheer B, Luo J, Klabbers R, Hancock LE, Gilbert J, Zaborina O, Alverdy JC, Sci. Transl. Med 2015, 7, 286ra68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Olivas AD, Shogan BD, Valuckaite V, Zaborin A, Belogortseva N, Musch M, Alverdy JC, PLoS One 2012, 7, e44326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wiegerinck M, Hyoju SK, Mao J, Zaborin A, Adriaansens C, Salzman E, Hyman NH, Zaborina O, van Goor H, Alverdy JC. Br. J. Surg 2017, 105, 1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hyoju SK, Klabbers RE, Aaron M, Krezalek MA, Zaborin A, Wiegerinck M, Hyman NH, Zaborina O, Van Goor H, Alverdy JC. Ann. Surg 2018, 267, 1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vadlamudi S, Nichols D, Papavasiliou G, Teymour F, Macromol. React. Eng 2018, 1, 1800066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yin Y, Papavasiliou G, Zaborina OY, Alverdy JC, Teymour F, Ann. Biomed. Eng 2017, 45, 1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nichols D, Hyoju SK, Pimentel MB, Teymour F, Hong SH, Zaborina O, Alverdy JC, Papavasiliou G, Frontiers in Biotechnology 2018, unpublished. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Maisel K, Reddy M, Xu Q, Chattopadhyay S, Cone R, Ensign LM, Hanes J, Future Medicine 2016, 11, 1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wagner RD, Johnson SJ, Danielsen ZY, Lim JH, Mudalige T, Linder S, PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Eiberweiser A, Nazet A, Hefter G, Buchner R, J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 779, 5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Borges FTP, Papavasiliou G, Murad S, Teymour F, Macromol. React. Eng 2018, 12, 1800012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shinoda K, Arai H, J. Phys. Chem 1964, 68, 3485. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Balmbra RR, Clunie JS, Corkill JM, Goodman JF, Trans. Faraday Soc 1962, 58, 1661. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schott H, Royce A, J. Colloid Interface Sci 1995, 173, 265. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Holtzscherer C, Candau F, J. Colloid Interface Sci 1988, 125, 97. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shinoda K, Takeda H, J. Colloid Interface Sci 1970, 32, 642. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Florence AT, Madsen F, Puisieux F, J. Pharm. Pharmacol 1975, 27, 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Opawale FO, Burgess DJ, J. Colloid Interface Sci 1998, 197, 142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kent P, Saunders BR, J. Colloid Interface Sci 2001, 242, 437. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tadros T, Encyclopedia of Colloid and Interface Science, Springer, Heidelberg, Germany: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [24].ICIHLB Booklet, http://www.firp.ula.ve/archivos/historicos/76_Book_HLB_ICI.pdf.

- [25].Landfester K, Bechtold N, Tiarks F, Antonietti M, Macromolecules 1999, 32, 5222. [Google Scholar]