Abstract

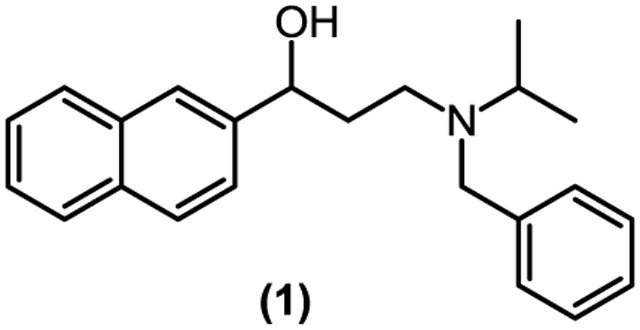

One therapeutic approach for Alzheimer's disease is to inhibit the cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by γ-secretase. At the beginning of a series of studies from our laboratories, a series of novel γ-amino alcohols (1) were found to possess γ-secretase inhibitory activity and Notch-sparing effects. A new one-pot synthesis of γ-amino alcohols and the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of these analogs will be discussed.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, γ-secretase inhibitors, γ-amino alcohols, Notch-processing, Aβ production

Graphical Abstract

Oligomerization of the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) is a key step in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1 The production of Aβ is a result of sequential cleavages of the amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases.2 Inhibitors targeting these two enzymes have been intensely pursued as potential disease-modifying therapeutics for AD.3 γ-Secretase is a multifunctional protease. It degrades a number of substrates, including APP and the Notch receptors, the latter being essential cell signaling proteins.4 One fundamental requirement for AD therapeutics that target γ-secretase is to selectively inhibit the proteolysis of APP without altering the γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of the Notch receptors, in particular Notch1.5 Our research to identify novel ‘Notch-sparing’ γ-secretase modulators and inhibitors has led to several chemical series of small molecules that can modulate γ-secretase to decrease Aβ production without alternation of Notch receptor processing. The work presented here is a series of γ-amino alcohols (1) that possess this selective inhibitory profile.

In our early work, two known Janus tyrosine kinase 3 (JAK3) inhibitors, ZM39923 and ZM449829 (Figure 1), were identified as γ-secretase inhibitors that showed Notch-sparing properties.6 However, the N-benzyl isopropyl-amino fragment of ZM39923 undergoes a facile elimination to yield ZM449829, which contains a reactive vinyl ketone. The unstable and reactive liabilities of these two compounds prevented them from being potential lead molecules. A simple conversion of the carbonyl of ZM39923 into a hydroxyl group by standard reduction methodology retained the selective profile of ZM39923 in inhibiting γ-secretase and provided a novel lead compound, 3-(benzyl (isopropyl)amino)-1-(naphthalen-2-yl)propan-1-ol (1).

Figure 1.

Conversion of ZM39923 to ZM449829 by elimination and to compound 1 by reduction using sodium borohydride.

To synthesize analogs of compound 1, a straightforward way would be to prepare the β-amino ketone precursor (e.g., ZM39923) followed by reduction of the ketone group to give the corresponding amino alcohols. The Mannich reaction is well suited procedure for synthesizing β-amino ketones in one pot. However, when formaldehyde, N-isopropyl benzylamine and phenyl methyl ketone were used to perform the one-pot reaction, very little desired product was obtained.

Thereafter, a Michael addition reaction was utilized, coupling benzylisopropyl amine and naphthalene-2-yl vinyl ketone in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of solid LiClO4 under solvent-free conditions. The resultant β-amino ketone (ZM39923) was reduced with NaBH4 to yield the desired β-amino alcohol (1) in high yield (Scheme 1). Alcohol 1 was evaluated for some drug-like properties (e.g., solubility, LogD, plasma protein binding, permeability, and human and rodent microsomal stability – See Supplemental Data) and these results supported a reasonable profile to begin synthesizing analogs of 1.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of 1 by Michael addition

To facilitate structural modification of 1, we developed a synthetic method toward substituted vinyl ketones (IV) from various aldehydes, which could be subsequently converted to β-amino alcohol analogs (I) as shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Method A for synthesis of γ-amino alcohols I

The addition of the readily available vinyl Grignard reagent to aryl aldehyde (II) gave the desired vinyl alcohol (III). The resulting crude vinyl alcohol was dissolved in dichloromethane and oxidized with tert-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP) in the presence of chromium (III) oxide as catalyst to give the α,β-unsaturated ketone (IV). Michael addition of disubstituted amines to aryl vinyl ketone (IV) in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of solid LiClO4 led to β-amino ketone (V) in high yield. However, subsequent purification of the Michael reaction product (V) by silica gel chromatography resulted in its decomposition to vinyl ketone (IV). Hence, the crude adduct (V) was directly reduced with sodium borohydride to yield the desired β-amino alcohol (I) in good yield (Scheme 2). The syntheses of these β-amino alcohols and some selected amines have been reported previously by our laboratory.7

Alternatively, we prepared some of the desired product (I) from another synthetic route, which employed acrolein (VI) and secondary amines (VII) in a Michael addition catalyzed by 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) to give β-amino aldehydes (VIII). These aldehydes were then treated with Grignard reagents in situ to form the desired γ-amino alcohols (I) in good yield. Notably, the Michael addition did not work well when primary amines were employed. However, this route (Method B, Scheme 3) consumed a shorter time and less purification steps in comparison with Method A (Scheme 2) to obtain product (I).

Scheme 3.

Method B for synthesis of γ-amino alcohol I

The compounds (I) reported in Tables 1-3 were synthesized either by Method A or Method B and then evaluated 8,9 for inhibitory effects on γ-secretase-mediated Aβ production using purified human γ-secretase complexes10 and a commercial ELISA for human β amyloid 1-40 (Invitrogen).11 The effects of the synthesized compounds on γ-secretase-mediated Notch processing were examined by Western Blot analysis using a method previously described.6 Compounds with at least a 50% inhibition in the Aβ40 ELISA were evaluated for their effect on the Notch processing. Testing at a high concentration was implemented in the early stages of lead identification so that no compound with any significant activity and desired selectivity was overlooked. All amino alcohol analogs exemplified in Tables 1-5 are in racemic form. Selected amino alcohol analogs of this chemical series were evaluated for additional biological data, such as %inhibition of Abeta 42 and also inhibition of Abeta 42 and the Notch receptor in cells (see Supplemental Data). Overall, Abeta 42 inhibition was similar to the Abeta 40 inhibition and in general, compounds tend to be less potent in cellular assays.

Table 1.

Alkyl Linker and Methyl Alcohol Analog of 1

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | n | Aβ40 (%) Inhibition a |

Notch 1 Processing b |

| 1 | H | 1 | 81 | No change |

| 2 | H | 0 | 0 | Inhibition |

| 3 | H | 2 | 18 | Inhibition |

| 4 | Me | 1 | 51 | No change |

See References and Notes sections for assay description

Table 3.

Variation of the amino group of I

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R2 | R3 | Aβ40 (%) Inhibition a |

Notch 1 Processing b |

| 1 | i-Pr | Bzl | 81 | No change |

| 18 | CH3 | Bzl | 15 | No change |

| 19 | CH3CH2 | Bzl | 15 | n.t. |

| 20 | cyclic-Pr | Bzl | 36 | n.t. |

| 21 | i-Butyl | Bzl | 0 | n.t. |

| 22 | t-Butyl | Bzl | 0 | n.t. |

| 23 | Bzl | Bzl | 32 | n.t. |

| 24 | i-Pr | Ph | 68 | Inhibition |

| ---------NR2R3-------- | ||||

| 25 |  |

0 | No change | |

| 26 |  |

0 | n.t. | |

| 27 |  |

38 | No change | |

| 28 |  |

61 | No change | |

| 29 |  |

15 | No change | |

Bzl:Benzyl

See References and Notes section for assay description; n.t.= not tested

Table 5.

Dialkyl analogs of compound (1)

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R7 | R8 | R9 | Aβ40 (%) Inhibition a |

Notch 1 Processing b |

| 1 | H | H | H | 81 | No change |

| 38 | Me | H | H | 72 | No change |

| 39 | Et | H | H | 82 | No change |

| 40 | Et | F | F | 69 | No change |

| 41 | Et | Cl | Cl | 59 | No change |

See References and Notes section for assay description

We first looked into the influence of the linker length between the amino and hydroxyl groups, and the importance of the free hydroxyl group. As shown in Table 1, shortening (2) or increasing (3) the linker by one methylene group significantly decreased the inhibitory effects on γ-secretase-mediated Aβ40 production and altered the Notch-sparing feature seen in compound 1. In contrast, methylation of the hydroxyl group (4) did not change the Notch-sparing profile whereas inhibition on Aβ40 production was somewhat reduced.

Analogs in which the naphhyl ring of compound 1 replaced with various aryl groups (R1) are shown in Table 2. The results indicate that the presence of two aromatic rings in the aryl moiety (R) appears to be critical for preserving the Notch-sparing property. Although substituted mono-aryl analogs (e.g., 12-17) did show a range of low to moderate potency, the Notch-sparing effects were abolished.

Table 2.

Aryl variations of naphthyl β-amino alcohol I

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | Synthesis Method |

Aβ40 (%) Inhibition a |

Notch 1 Processing b |

| 1 |  |

A/B | 81 | No change |

| 5 |  |

A | 46 | No change |

| 6 |  |

B | 30 | No change |

| 7 |  |

B | 24 | No change |

| 8 |  |

A | 0 | n.t. |

| 9 |  |

A | 0 | n.t. |

| 10 |  |

A | 0 | n.t. |

| 11 |  |

A | 31 | No change |

| 12 |  |

A | 10 | Inhibition |

| 13 |  |

A | 72 | Inhibition |

| 14 |  |

B | 20 | Inhibition |

| 15 |  |

B | 30 | Inhibition |

| 16 |  |

B | 15 | Inhibition |

| 17 |  |

B | 29 | Inhibition |

See References and Notes section for assay description; n.t. = not tested

The data on these aryl substituted β-amino alcohols illustrated in Table 2 indicated that the original naphthyl analog 1 was still the most potent analog with the strongest inhibition on γ-secretase-mediated Aβ40 production. We investigated the activity of each enantiomer of analog 1 by reducing ZM39923 (Figure 1) with (R)-(+)-2-methyl-CBS oxazaborolidine and also with (S)-(+)-2-methyl-CBS oxazaborolidine to give the respective (R)- and (S)-enantiomers of Entry 1. Neither of these stereoisomers showed an improvement in Abeta 40 activity. Hence, our attention was then focused on introducing various γ-amino groups (Table 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Variation of the substitution on benzyl group of 1

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R4 | R5 | R6 | Aβ40 (%) Inhibition a |

Notch 1 Processing b |

| 1 | H | H | H | 81 | No change |

| 30 | F | H | F | 54 | Inhibition |

| 31 | H | F | F | 64 | No change |

| 32 | H | Cl | Cl | 60 | No change |

| 33 | H | OMe | H | 55 | No change |

| 34 | H | CN | H | 19 | n.t. |

| 35 | H | H | CN | 7 | n.t. |

| 36 | OMe | H | OMe | 17 | No change |

| 37 | H | F | Cl | 38 | n.t. |

See References and Notes section for assay description; n.t.=not tested.

The results shown in Table 3 suggested that alkyl substitution on the amino group significantly influences inhibitory effects on γ-secretase. Notably, replacing the isopropyl of R2 with larger alkyl groups (e.g. isobutyl, 21) abolished the activity on inhibition of Aβ40 production. The isopropyl group (R2) is by far the best substituent within the simple alkyl groups investigated.

Interestingly, replacing the benzyl group with a phenyl ring (24) maintained similar potency on inhibition of γ-secretase-mediated Aβ40 production, but the Notch-sparing property was lost. Further, replacing the entire amino group of (1) with phenyl substituted piperizinyl groups (25-29) seemed tolerated, but the potency varied and highly relied on the substitution of the phenyl ring. The aforementioned structural modifications indicated the importance of several fragments, including the naphthalene-2-yl, iso-propyl and benzyl functionalities.

We further introduced some substituents on the benzyl group of the amino moiety (Table 4). The results suggested that fluoro- and chloro- groups are well-tolerated. Although no significant improvement in potency was observed, halogen substitutions could potentially help brain penetration and effect metabolic stability.

As previously mentioned, conversion of the ketone group of ZM39923 into a hydroxyl group in compound 1 (Scheme 2), we reduced the chemical instability of this β-aminoketone skeleton. However, it is also possible that the hydroxyl group of I may not be very stable in vivo. Hence, we intentionally introduced two alkyl groups (R7) at the α-position to prevent the possible elimination of the β-amino group. These compounds (Table 5) were synthesized via the Mannich reaction, using our new one-pot reaction, coupling acrolein (37% in water) and isopropyl benzyl amine in ethanol at 90~92°C for 40 h to form an amino-aldehyde intermediate. After evaporation of all solvents and drying (oil pump), the amino-aldehyde residue was dissolved in anhydrous THF at 0°C, and the corresponding Grignard reagents were added to give the desire products.

It was found that introducing two geminal alkyl groups (i.e., methyl and ethyl) at the β-position of compound 1 did not abolish the inhibition on γ-secretase-mediated Aβ40 production, while Notch-sparing effects were preserved (e.g., 38-41). The most interesting dialkyl substituted analog 39 showed very good inhibition in cells against Abeta 40 and 42 (80% and 100% @ 100 μM, respectively) as well as very good selectivity for the Notch receptor with an IC50 >75 μM.

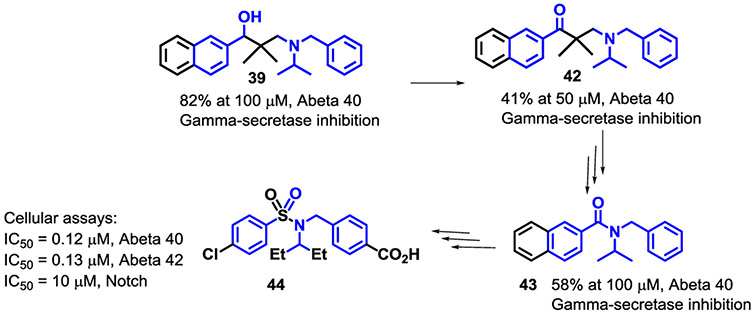

Oxidation of the hydroxyl group of 39 gave the keto-analog 42 which showed modest inhibition (40% @ 50 μM). Studies ongoing in our laboratories at this time were investigating aryl amides (e.g., 42) and various size linkers.

These studies converged and led to more potent and selective sulfonamide analogs like 44 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Evolution of Naphthyl Amino Alcohols

In summary, based on the structure of JAK3 inhibitor, ZM39923, an unstable β-amino ketone, we synthesized a series of γ-amino alcohol analogs (I). Within this class of compounds, the presence of two aromatic rings, such as naphthalene-2-yl and phenoxy-phenyl, in the immediate proximity of the alcohol functionality, consistently provided Notch-sparing effects. The benzyl group seemed to be another important feature that affected the inhibition of γ-secretase-mediated Aβ40 production and Notch-sparing properties. Additionally, substitution of the two β-protons did not alter the overall profile of Notch-sparing inhibition of γ-secretase, but should add chemical stability to the framework in that the amino functionality cannot be eliminated by retro-Michael addition. Compounds of this type provided a valuable template that led to sulfonamide analogs for animal studies and potential differentiation from failed clinical candidates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jian Chen and Katherine M. Brogan for their assistance with the biological testing. We acknowledge the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, the Harvard NeuroDiscovery Center and members of the Center for Neurologic Diseases for funding support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Aβ ELISA. Human γ-secretase complex was purified from Chinese hamster ovary cells stably overexpressing all four human components of the enzyme.10 In vitro γ-secretase assays, using the recombinant APP-based substrate C-100 FLAG and Aβ ELISAs, were performed as reported previously.8,9 The tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO; final drug concentration was 100 μM and final DMSO concentration was 1%. The proteolytic reaction mixtures contained C-100 FLAG substrate, and purified γ-secretase complex in 0.2% CHAPSO/HEPES at pH 7.5, and were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. All reactions were stopped by adding 0.5% SDS, and the samples were assayed for Aβ40 by ELISA using a commercial kit (Invitrogen);11

Western Blot Analysis.6 Compounds showing inhibition of Aβ production of at least 50% from the γ-secretase activity assays were selected and run on 10-20% Tris-Tricine gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes to detect AICD-FLAG with anti-FLAG M2 antibodies (1:1000, Sigma) and NICD-FLAG with cleaved Notch 1 (Val1744) antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) that is selective for the N-terminus of the Notch intracellular domain.

References and Notes

- 1.Selkoe DJ Science 1997, 275, 630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe MS Neurotherapeutics 2008, 5, 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangialasche F; Solomon A; Winblad B; Mecocci P; Kivipelto M Lancet Neurology 2010, 9, 702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe MS Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2009, 20, 219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imbimbo B; Giardina G Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2011, 11, 1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraering PC; Ye W; LaVoie MJ; Ostaszewski BL; Selkoe DJ; Wolfe MS J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 41987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Augelli-Szafran CE, Wolfe MS; Wei H-X WO2009051661 A2. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esler WP; Kimberly WT; Ostaszewski BL; Ye W; Diehl TS; Selkoe DJ; Wolfe MS Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2002, 99, 2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimberly WT; Esler WP; Ye W; Ostaszewski BL; Gao J; Diehl T; Selkoe DJ; Wolfe MS Biochemistry 2003, 42, 137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraering PC; Ye W; Strub JM; Dolios G; LaVoie MJ; Ostaszewski BL; van Dorsselaer A; Wang R; Selkoe DJ; Wolfe MS Biochemistry 2004, 43, 9774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia W; Zhang J; Ostaszewski BL; Kimberly WT; Seubert P; Koo EH; Shen J; Selkoe DJ Biochemistry 1998, 37, 16465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.