Approximately 4 million surgical procedures are performed annually in older adults aged 65 years and older.1 Older surgical patients are different from younger counterparts due to baseline geriatric conditions such as frailty, cognitive impairment, and multimorbidity, among others. Older adults also value different health outcomes than younger patients. Studies suggest that 70% of older adults would not choose treatments that would lead to loss of independence, functional decline, or cognitive impairment, even if the treatment would prolong life.2,3 Despite this fact, most surgical research in older adults is designed to evaluate traditional outcomes such as one-year mortality or healthcare utilization rather than patient-centered outcomes. Data are lacking on how surgical interventions impact outcomes valued by older adults, and on how baseline geriatric conditions such as frailty may influence these outcomes following surgery. The study by Thillainadesan et al in this issue addresses this knowledge gap for the burgeoning population of older adults undergoing vascular surgery.4 The authors had two objectives: 1.) to evaluate the associations between frailty and multiple hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes, and 2.) to measure the utility of two validated frailty indices in predicting the hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes of delirium and functional decline.

The authors conducted a prospective observational cohort study of 150 older adults (>=65 years) consecutively admitted to a vascular surgery service in 2019.4 Exclusion criteria included same day procedures, surgery conducted while admitted to another service, or expected admission length of stay of less than two days. The study cohort underwent a variety of vascular surgery procedures ranging from endovascular to open revascularizations, amputations, and debridement. Important geriatrics-focused baseline data points were collected and included two frailty indices (Clinical Frailty Scale5 and Rockwood Frailty Index6,7) as the primary predictors, as well as multimorbidity, falls, functional status, and cognition. The primary outcome measures were hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes including delirium, functional decline at discharge, constipation, pressure injury, and falls. The secondary outcomes were more traditional measures such as mortality and readmissions, but also polypharmacy and high-risk prescribing at discharge. The authors found that up to one-third of admitted older vascular surgery patients were frail, depending on the measure used. Of 150 patients enrolled, 65% experienced at least one hospital-acquired geriatric syndrome. Constipation was the most common (53%), followed by functional decline (19%), and delirium (10%). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, both the Rockwood FI (adjusted OR 5.64, 95% CI 1.47–21.7) and CFS (adjusted OR 4.21, 95% CI 1.14–15.5) were significantly associated with delirium. The authors also found that the Rockwood FI and CFS had acceptable discrimination when predicting for delirium.

As the authors note, this study had some limitations including a single hospital experience with a limited number of outcome events in a smaller cohort, which is reflected in wide confidence intervals for the primary outcomes. Despite these limitations, the authors demonstrate the feasibility of a prospective study designed to measure frailty and hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes in older surgical patients. Additionally, the findings highlight the importance of measuring associations between baseline frailty and relevant geriatric-focused outcomes in hospitalized surgical patients.

Prior large studies of older adults undergoing surgery have been designed to primarily measure traditional outcomes such as postoperative mortality.8 For example, a recent study of over 2.7 million surgical patients found that frailty was significantly associated with both 30-day and 180-day postoperative mortality. Surgical specialties were categorized from low to high intensity, and the relationship between frailty and mortality held even for low intensity specialties such as plastic surgery.9 In vascular surgery, a high intensity specialty, a designation of “very frail” as measured by the Risk Analysis Index was closely associated with 30-day mortality (adjusted OR 12.66, 95% CI 10.31–15.55).10 Similarly, another recent study retrospectively evaluated 1341 older adults from the Health and Retirement Study undergoing 3 types of major surgery. The study objective was to evaluate the association between several geriatric conditions (functional dependence, cognitive impairment, and depression) and 1-year mortality. The authors found a monotonic relationship between an increasing number of impairments and increasing risk of 1-year mortality following major surgery. In particular, dependence in at least one activity of daily living was significantly associated with 1-year mortality (adjusted HR 2.76, p=0.001).11

Understanding the relationship between frailty and mortality can be helpful when counseling older adults considering surgery, but there are limitations to only considering mortality as an outcome. In our surgical urology practice, older adults display less interest in length of life, and instead ask probing questions about the hospitalization itself in the short-term and the chances of returning to baseline preoperative function in the long-term. In response to this practical need for more data about geriatrics-focused predictors and outcomes for older surgical patients, the current study and other recent studies have focused on important patient-centered outcomes. For example, two recent publications studied the new patient-oriented outcome of time spent away from home following emergency general surgery and high-risk cancer surgery.12,13

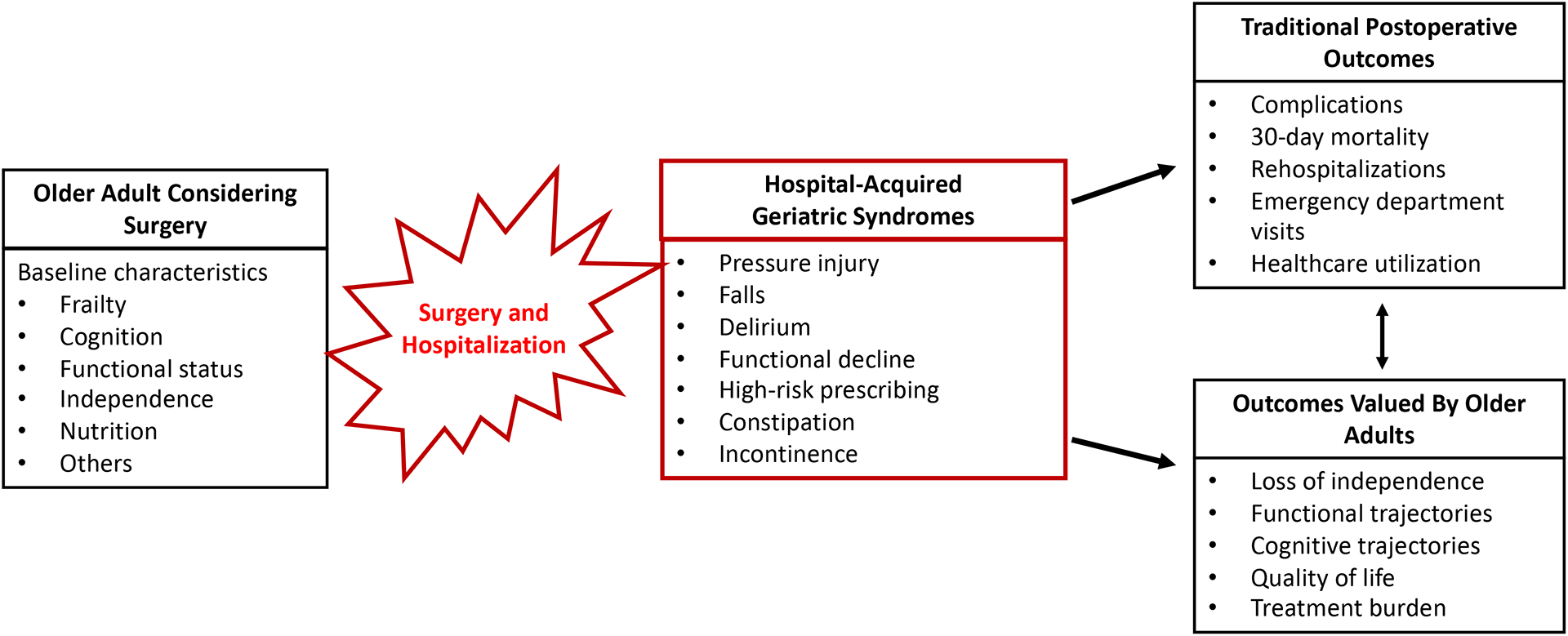

The authors of the current study demonstrated the utility of baseline frailty measures for predicting hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes. Hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes are detrimental to both traditional outcomes such as mortality and longer-term outcomes valued by older adults such as maintaining independence (Figure 1).14 Unfortunately, there are few existing criteria to define the cadre of hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes. For example, the current Centers for Medicare and Medicaid list of hospital-acquired conditions only refers to falls and Stage III and IV pressure ulcers.15 The current study included these as key outcomes, as well as validated measures for delirium, functional status at discharge, constipation, and high-risk prescribing.4 Although postoperative and post-hospitalization trajectories were beyond the scope of the current study, identifying and preventing hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes has potential to improve longer-term postoperative quality of life for the population of older surgical patients. Ongoing large cohort studies such as Successful Aging after Elective Surgery are beginning to provide long-term data on patient-centered outcomes following hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes such as delirium.16 Additionally, implementing frailty measures in surgical clinics and inpatient services may help to predict which older adults are at risk for hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes and longer-term functional decline and cognitive impairment after surgery.

Figure 1:

Interaction Between Baseline Geriatric Conditions, Surgery, and Traditional and Patient-Centered Outcomes in Older Surgical Patients

Multiple organizations have recognized the need for specialized preoperative assessment and postoperative management of older surgical patients.17,18 Guidelines issued jointly by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the American Geriatrics Society have called for routine preoperative measurement of frailty, cognitive function, nutrition, and other geriatric conditions.19 The ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) Surgical Risk Calculator now has an input for functional status as a predictor and provides risk estimates for discharge to nursing home or rehabilitation facility.20 Data from the ACS Geriatric Surgery Pilot Program will further enrich the ACS NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator for both geriatric risk factors and patient-centered outcomes. The ACS Geriatric Surgery Pilot Program was launched in 2014 with over 35,000 older surgical patients from 21 hospitals. The project measured new preoperative geriatric risk factors in the domains of cognition and decision-making, mobility, and functional factors.21 The new models predict postoperative risk for the outcomes of pressure ulcers, delirium, new mobility aid use, and functional decline.22

Now and in the future, all surgeons caring for adult patients will need to embrace surgical care with a geriatrics lens. While there is increasing recognition of the need for a specialized approach to preoperative and postoperative evaluation and management of older patients undergoing surgery, uptake remains low and there are significant barriers towards implementation. Time and resource constraints remain in surgical practices especially in community settings, but newer tools like the enhanced NSQIP calculator, efficient frailty assessments like the Risk Analysis Index, and wearable technology hold promise for overcoming these barriers.23,24 Multiple evidence-based interventions exist to reduce delirium, functional decline, falls, and other hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes. Implementation research, human-centered design, and consideration of hospital built environments is needed to incorporate these interventions into perioperative settings.

Hospitals and health systems remain focused on traditional outcomes such as mortality, rehospitalizations, and emergency room visits likely due to current payment models. Health system leaders and policymakers should also consider the total societal cost benefits of optimizing preoperative geriatric conditions to improve both traditional and patient-centered outcomes for this large and growing high-risk group. Loss of independence, high-risk prescribing, and functional decline resulting from the combination of surgery and prolonged hospitalization may lead to increased healthcare utilization and costs to patients, caregivers, and payors. We need to build goal-concordant perioperative care for older adults that optimizes pre-existing geriatric syndromes, prevents new or worsening syndromes during hospitalization, and maximizes quality of life and functional recovery.

In summary, the study by Thillainadesan et al found that up to one-third of older vascular surgery inpatients have frailty, and that baseline frailty is associated with hospital-acquired geriatric syndromes, most notably delirium.4 This study highlights the critical need for surgical research to incorporate geriatrics-focused predictors and patient-centered outcomes. Understanding how surgery impacts outcomes valued by older adults will inform future perioperative care re-design efforts to address the unique needs and goals of older surgical patients.

Funding Sources:

Dr. Garg was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R03AG064382).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Tullika Garg served as a paid consultant to WebMD and reports an immediate family member is an employee of DRPLZ and is a stockholder. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Sponsor’s Role: The authors declare no role for any sponsor in the preparation of this editorial.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schwarze ML, Barnato AE, Rathouz PJ, Zhao Q, Neuman HB, Winslow ER, et al. Development of a List of High-Risk Operations for Patients 65 Years and Older. JAMA Surg [Internet]. 2015. April 1;150(4):325–7. Available from: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, O’Leary JR, Towle V, Van Ness PH. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med [Internet]. 2011. November 14;171(20):1854–6. Available from: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archinternmed.2011.424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the Treatment Preferences of Seriously Ill Patients. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2002. January 1;346(14):1061–6. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMsa012528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thillainadesan J, Mudge AM, Aitken SJ, Hilmer SN, Cullen JS, Yumol MF, et al. The Prognostic Performance of Frailty for Delirium and Functional Decline in Vascular Surgery Patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Cmaj. 2005;173(5):489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridda I, Lindley R, MacIntyre RC. The challenges of clinical trials in the exclusion zone: The case of the frail elderly. Australas J Ageing. 2008; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitnitski A, Song X, Skoog I, Broe GA, Cox JL, Grunfeld E, et al. Relative fitness and frailty of elderly men and women in developed countries and their relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2184–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper Z, Scott JW, Rosenthal RA, Mitchell SL. Emergency Major Abdominal Surgical Procedures in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Mortality and Functional Outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(12):2563–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwarze ML, Barnato AE, Rathouz PJ, Zhao Q, Neuman HB, Winslow ER, et al. Development of a List of High-Risk Operations for Patients 65 Years and Older. JAMA Surg [Internet]. 2015. April 1;150(4):312–25. Available from: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George EL, Hall DE, Youk A, Chen R, Kashikar A, Trickey AW, et al. Association between Patient Frailty and Postoperative Mortality across Multiple Noncardiac Surgical Specialties. JAMA Surg. 2020;94305:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang VL, Jing B, Boscardin J, Ngo S, Silvestrini M, Finlayson E, et al. Association of Functional, Cognitive, and Psychological Measures With 1-Year Mortality in Patients Undergoing Major Surgery. JAMA Surg [Internet]. 2020. March 11;1–7. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/2762522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KC, Streid J, Sturgeon D, Lipsitz S, Weissman JS, Rosenthal RA, et al. The Impact of Frailty on Long-Term Patient-Oriented Outcomes after Emergency General Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):1037–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suskind AM, Zhao S, Boscardin WJ, Smith A, Finlayson E. Time Spent Away from Home in the Year Following High-Risk Cancer Surgery in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(3):505–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti M, Kuchel G. Geriatric Syndromes: Clinical, Research and Policy Implications of a Core Geriatric Concept in older adults related to primary and secondary prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc [Internet]. 2007;55(5):780–91. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2409147/pdf/nihms46888.pdf%0Ahttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62074/?part= [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital-Acquired Conditions [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalAcqCond/Hospital-Acquired_Conditions

- 16.Schmitt EM, Saczynski JS, Kosar CM, Jones RN, Alsop DC, Fong TG, et al. The Successful Aging after Elective Surgery Study: Cohort Description and Data Quality Procedures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(12):2463–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald SR, Heflin MT, Whitson HE, Dalton TO, Lidsky ME, Liu P, et al. Association of Integrated Care Coordination With Postsurgical Outcomes in High-Risk Older Adults. JAMA Surg [Internet]. 2018. January 3;1–12. Available from: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Urological Association. Optimizing Outcomes in Urological Surgery: Pre-Operative Care for the Patient Undergoing Urologic Surgery or Procedure [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/optimizing-outcomes-in-urological-surgery-pre-operative-care-for-the-patient-undergoing-urologic-surgery-or-procedure

- 19.ACS NSQIP/AGS Best Practice Guidelines: Optimal Preoperative Assessment of the Geriatric Surgical Patient [Internet]. 2012. October. Available from: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/nsqip/acsnsqipagsgeriatric2012guidelines.ashx

- 20.American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) Surgical Risk Calculator.

- 21.Berian JR, Zhou L, Hornor MA, Russell MM, Cohen ME, Finlayson E, et al. Optimizing Surgical Quality Datasets to Care for Older Adults: Lessons from the American College of Surgeons NSQIP Geriatric Surgery Pilot. J Am Coll Surg [Internet]. 2017;225(6):702–712.e1. Available from: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hornor MA, Ma M, Zhou L, Cohen ME, Rosenthal RA, Russell MM, et al. Enhancing the American College of Surgeons NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator to Predict Geriatric Outcomes. J Am Coll Surg [Internet]. 2020;230(1):88–100.e1. Available from: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah R, Borrebach JD, Hodges JC, Varley PR, Wisniewski MK, Shinall MC, et al. Validation of the Risk Analysis Index for Evaluating Frailty in Ambulatory Patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1818–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Najafi B, Veranyan N, Zulbaran-Rojas A, Park C, Nguyen H, Nakahara QK, et al. Association Between Wearable Device-Based Measures of Physical Frailty and Major Adverse Events Following Lower Extremity Revascularization. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3(11):e2020161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]