Abstract

Little evidence exists about the emotional experiences of mothers with HIV, and a better understanding is essential to support their emotional health and treatment adherence. We describe the emotional experiences of eight mothers who initiated antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy or within a few years of childbirth in Lima, Peru. An interpretive phenomenological approach was used, and the following themes emerged: (a) emotions involved in diagnosis and disclosure, (b) the meaning of motherhood with HIV, (c) the mothers’ roles in seeking and maintaining relationships with partners and families, and (d) mechanisms for resilience and emotional recovery. Participants experienced sadness and denial after diagnosis, which gave way to emotional recovery. Participant abilities to find refuge in caring for children and coordinating support from loved ones proved to be essential. Participants recognized that intense emotions motivated them to seek creative solutions and cited personal growth as an important outcome.

Keywords: emotions, HIV, motherhood, postpartum, pregnancy, recovery

HIV is a public health issue of great importance that disproportionately affects vulnerable populations (World Health Organization, 2018). At the global level, official statistics show that the number of women living with HIV (WLWH) has increased at an alarming rate, with women making up 50% of the total population of people living with HIV (PLWH) and 880 million adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years are diagnosed with the infection (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014). In Peru, approximately 70,000 persons were living with an HIV diagnosis in 2016, and new HIV infections have increased by 24% since 2010 (UNAIDS, 2018). Although the gap between male and female HIV case notifications in the country has decreased considerably from 11.8–1.0 in 1990 to 3.4–1.0 in 2012 (Castro & Sandesara, 2009), still an estimated 790 pregnant women were taking antiretroviral drugs, with another 1,000 in need, and 100 infants were born with HIV in Peru in 2016 (UNAIDS, 2018). No data are available about the experience of mothers with HIV in Peru.

Various studies have identified that PLWH cycle through a series of emotional phases while dealing with the diagnosis, the first of which was described by Reeves, Merriam, and Courtenay (1999). When initially diagnosed with HIV, infected individuals undergo intense emotions that can destabilize everyday life. During this phase, many feel loss, affliction, and uncertainty about the future, including internalized stigma and withdrawal from social life (Demmer, 2010). PLWH may progress to optimism and adaptation or to isolation, mania, and pathological hiding of the diagnosis (Demmer, 2010; Withell, 2000). One study described three distinct predictable phases: (a) intense emotional experiences and denial, (b) gaining control and addressing the illness directly, and (c) acceptance (Reeves et al., 1999).

Existing literature related to pregnant and postpartum WLWH has focused on the description of these phases. In particular, past research has highlighted how the progression through these phases affects maternal activities, such as providing care for their children and breastfeeding (Hebling & Hardy, 2007; Sanders, 2008; Trocmé, Courcoux, Tabone, Leverger, & Dollfus, 2013), and how external mechanisms such as socioeconomic status and social supportaffect thetransition between these phases (Fords, Crowley, & van der Merwe, 2017; Waters et al., 2017). A meta-synthesis structured the experience of pregnant women diagnosed with HIV into four themes: (a) the initial shock of the diagnosis, (b) intense loneliness, (c) hope, including the desire to see their children grow, and (d) limited social support (Leyva-Moral, Piscoya-Angeles, Edwards, & Palmieri, 2017). However, there is a curious absence of literature on its counterpart, that is, the internal capacities of pregnant and postpartum WLWH to confront the emotional burden of the disease as active participants in the recovery process.

Coping is a related topic in the literature and is often described as a series of skills that are learned and applied in emotionally threatening or demanding situations and characterized as active or passive, healthy or unhealthy, emotion or problem based, or inward or outward focused (Martz, & Livneh, 2007). The health-related literature on coping comes from the behavioral science school of thought and has focused on the ability to conduct certain behaviors that tolerate or minimize the effects of stress (Snyder, 1999). Coping is central to effective human function and is a critical skill, particularlyfor peopleliving with chronic or stigmatizing diseases (Martz & Livneh, 2007). A growing body of literature has described coping strategies used by mothers with HIV. One study, conducted with 20 pregnant and postpartum WLWH in Uganda, found that the women used self-reliance and acceptance as coping strategies and drawing on support from interpersonal sources, such as family, and community support systems, such as the church (Ashaba et al., 2017). A quantitative study followed 293 pregnant WLWH in South Africa for 24 months and found that active coping strategies (e.g., concentrating efforts to make things better and taking action to improve the situation) were used more often as time passed after the diagnosis and that inward-focused coping strategies were used more at first (e.g., acceptance and positive reframing), whereas outward strategies were common as the infant grew older (e.g., information seeking, helping others; Kotzé, Visser, Makin, Sikkema, & Forsyth, 2013).

However, for our study, the research team felt strongly that the concept of coping would be a restrictive conceptual framework. Coping tends to focus on a prescriptive action as a pragmatic solution to a negative reality or set of emotions. In contrast, we were interested in the depth of the journey to recovery and the singularity of the women’s resolutions. We felt as though classifying experiences into coping strategies would not advance knowledge or tools in new ways to help mothers with HIV confront their challenges. Instead, we chose to use an interpretive phenomenological approach. Interpretive phenomenology, termed by psychologist Jonathan Smith, focuses on studying a phenomenon through lived experience and seeks to describe subjects’ lifeworlds (Smith, 1996). Interpretive phenomenology has been used to study significant disruptions in life due to illness, which requires a nuanced and contextualized understanding, or with underrepresented groups, whose daily lived experiences are little understood or historically excluded from main-stream research. We argue that both of these scenarios apply to women diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy or soon after and living in poverty in Lima, Peru.

Our study, which draws data from the Community-based Accompaniment with Supervised Antiretrovirals (CASA) study, used interpretive phenomenological methods to understand the experience of mothers diagnosed with HIV in Lima, with particular attention paid to their emotional experiences as mothers and their active roles in emotional recovery.

Methods

Participants

From 2010 to 2014, the nongovernmental organization, Partners In Health Peru (PIH Peru), implemented the CASA study, the parent study within which this study is nested. CASA included directly observed therapy of 356 PLWH living in extreme poverty who had recently started antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Lima. CASA collaborated with the Peruvian Ministry of Health to train community health workers to administer medications while simultaneously providing social support and a connection to clinical care as needed for a year (Shin, Munoz, Caldas, et al., 2011; Shin, Munoz, Zeladita, et al., 2011; Waters et al., 2017).

The broader study included 129 WLWH who were living in extreme poverty in Lima, Peru. Of the 129 women, eight matched the inclusion criteria of our study. Participants (a) received their HIV diagnosis during pregnancy or the postpartum period and (b) had at least one child younger than 3 years. Selection was unbiased by the serostatus of their children.

Study participants provided verbal informed consent to participate in in-depth recorded interviews. Teams of two researchers conducted interviews in participants’ homes. One person led the interview while the second researcher took written notes; the interview was also audiotaped. Interviews ranged from 60 to 90 minutes. Two individuals carried out interviews to ensure the safety of research staff.

Ethical Concerns

The ethics committees of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Peruvian National Institute of Health in Lima, Peru (Ministerio de Salud del Perú), approved the study. All women signed informed consent forms. Audio files were downloaded onto a local password-protected computer and then removed from the recording device. Once transcribed and de-identified, audio files were deleted. Names were changed to protect participant identity.

Interview

We created an in-depth interview guide with questions addressing broad themes about participant’s health care and lifestyles, including childhood, HIV diagnosis, treatment initiation, stigma, family dynamics, and forms of social support (e.g., How did you find out about your diagnosis? Who did you tell first and why? What was the reaction of this person and other people in your social group? Did you feel rejection or mistreatment? Who were the people who you felt closest to? Did anyone help you, who did you go to when you needed support? How did HIV change your life, your plans, and your dreams? How has it affected your family?). A Peruvian team was trained in Spanish by a U.S. medical anthropologist who spoke Spanish as a first language, on qualitative data collection methods. We used open-ended questions in all interviews, which allowed us to capture a wide range of emotions during different stages of life. Interviews sought to identify emotions that participants experienced related to their roles as mothers living with HIV.

Data Analysis

For data analysis, study members de-identified, transcribed, and edited interviews for errors or omissions and then coded all interviews. The analysis team consisted of a U.S. researcher from the CASA project with extensive qualitative experience; three employees from the PIH Peru organization, who were external to the study and trained in qualitative analysis; and two U.S. medical students. We applied open coding to first create a list of all emerging themes, which we then grouped according to similarities and discarded unrelated themes. The overarching themes and subthemes were articulated into a codebook with three main themes containing 9–10 subthemes each, capturing emotions related to HIV and motherhood. Using the codebook, two evaluators coded each interview independently, and interpretation differences were resolved by a third evaluator. Despite the small sample size, we reached theoretical saturation when themes were confirmed by at least two new interviews and no new themes emerged.

Themes were summarized, considered in terms of relevance to the research question, and analyzed using interpretive phenomenology analysis (Cassidy, Reynolds, Naylor, & De Souza, 2011; Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009). First, we created concepts such as reframing the role of mother and mechanisms for resilience with particular attention to the participants’ lived experiences, motherhood, and their active roles in recovery. Next, we wove these concepts together to create a narrative. We employed analysis triangulation to ensure credibility by including contributions from the study coordinator and field team, who were intimately familiar with the participants’ lived experiences. To supplement interview results, we collected sociodemographic data from the clinical trial database CASA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and HIV Data of Participant Mothers With HIV (N = 8)

| Variables | Median [Range] or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, year | 23.5 [22–26] |

| Children prior to pregnancy at time of study | 2 [2–5] |

| Violence during childhood | 7 (87.5%) |

| Age of first sexual relations, year | 17 [15–25] |

| Diagnosed | |

| During pregnancy | 6 (75%) |

| After pregnancy | 2 (25%) |

| Years living with diagnosed HIV at interview | 1.6 [0.1–7.06] |

| Salvage ART regimena | 1 (12.5%) |

| At least one child with HIV, n = 5b | 3 (60%) |

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Due to previous treatment failure.

In five cases, participant’s children were all old enough to receive a definitive HIV test. The other three participants had at least one child too young to accurately determine their HIV status.

Results

Participants

We investigated a group of eight WLWH. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of study participants. The range between HIV diagnosis and the interview was 35 days to 9.11 years (median = 1.58 years).

Themes

Data analysis revealed three themes: (a) participants’ emotional experiences upon receiving the diagnosis, including feelings involved in sharing the diagnosis with family members; (b) emotions unique to the experiences of motherhood and HIV, including breastfeeding, vertical transmission, and childcare; and (c) participants’ emotional responses related to family and partner relationships. In particular, these data highlighted the women’s abilities to actively seek and provide support in reciprocal relationships that nurtured their own emotional recovery. Finally, we outline mechanisms of resilience that the women used to overcome the emotional burden of the disease. The context of motherhood and the lived experience of the participant as an active participant in her own life are highlighted as being central to the emotional recovery process. Exemplars from the interviews are identified with a pseudonym and the participant’s age.

Diagnosis: A time of extreme emotions.

On receiving the diagnosis, participants experienced sadness, especially when considering consequences the disease could have on their children’s future. Denial was also common, particularly for newly diagnosed pre-symptomatic cases. Given that all participants reported acquiring HIV sexually from their partners, they discussed conflicting feelings toward the partners. Worry about the strength of family relationships and the well-being of their children were also a concern.

On receiving the diagnosis, seven participants verbalized feeling sadness. For these paarticipants, the experience was comparable to receiving a diagnosis of a terminal illness, generating feelings of the certainty of death and total hopelessness. “… I did not know very well at the time what the disease was, and I told myself that after 1 year, I was going to die …. At that time, I was thinking about my death” (Rosa, 36).

Additionally, participants expressed fear that they would not be alive to take care of their children.

… Obviously when I found out, I began to cry and cry, nothing more. I said, “Well now that I am not well, now my little girl, so small, who will watch her?” I thought like that, you know? Who was going to raise my little girl? This was my idea.

(Romina, 36)

Three participants avoided accepting their diagnoses. All three received the diagnosis during a routine gestational test before the onset of HIV-associated symptoms.

I ignored it [the HIV test result], everything. I ignored it because I felt healthy. If I feel fine, then why is it an issue? “All of it is nonsense,” I said. I ignored it

(Andrea, 25).

Feelings of depression and fear were accompanied by feelings of isolation or impulses to distance themselves and protect their children from others. “… I did not want anybody to ever touch me. I only grabbed my baby and took him somewhere where I could feed him. There, I cried. I did not talk with anyone” (Esme, 24). Two participants expressed specific rejection or indignation toward their partners. The impulse of mothers to isolate themselves while protecting their children was done by instinct, spontaneously, and as a reaction to the perception of being under attack. This was a common reaction and served as a response to the intense emotions related to their diagnoses.

Reaching out: Sharing an HIV diagnosis with loved ones.

Many participants found themselves in a dilemma, in need of family support and, at the same time, fearful of their families’ responses. Six participants expressed fear of sharing the diagnosis with their families; two who intended to share their diagnosis never reached the point of actually carrying out the action, but four ultimately disclosed. Participants mentioned that the main factors causing this fear were (a) lack of knowledge about the disease, (b) fear of being discriminated against by family members or of suffering additional violence from them, and (c) intention to reduce emotional strife to the family.

No, I never [thought of telling my siblings my diagnosis] … because if I had to say, there is no telling how they would distance themselves from me. I say this—that they would throw me out—… because I have seen how they discriminate against a girl, they speak about her …there’s a girl here on the other side of the street that has it, and because of it they talk about her to me. No, I prefer not to say anything.

(Selma, 26)

… Yes, I wanted to tell them, but sometimes it scared me that they were going to get depressed or suddenly change their emotional state …. Because right now I see that they are doing well. However, after touching on it, or explaining it, or even telling them what I have, they are going to think—just like I did—that I am going to die or something.

(Rosa, 36)

Six participants expressed sadness and worry for the well-being of their families, which became an obstacle to receiving family support and delayed the search for medical attention in health centers.

Of course I don’t tell my parents because I know that it will bother and worry them. My mother will get depressed in addition to her already not doing well. I don’t want her to have more to worry about.

(María, 22)

In María’s case, her own experience as a mother fearful of having a child with HIV discouraged her from sharing the diagnosis with her family because she did not want her mother to experience the same pain that she had gone through. “… I didn’t tell my mother because I knew that it was going to impact her …. Only after a month did I tell her because I couldn’t do it anymore. I couldn’t bear it and I was very desperate” (María, 22).

Women imagined the worst when contemplating their families’ reactions, further exaggerating fear and isolation. This was a time of great loneliness, sadness, and self-doubt.

At first, no. I was quiet. I was scared that my family would find out or that they would discriminate, but no. At the time, I thought they would, but my family recently found out, when I was pregnant with my little girl. If I hadn’t had this baby, nobody in my family would have known, right? Until that day because he [partner] also was a little scared that my family would find out, that they would discriminate against me, and that they would blame me, but no they didn’t.

(Lucy, 23)

In Lucy’s case, however, feelings of guilt and fear about disclosing the diagnosis to her family resolved after she was surprised by their acceptance and support.

HIV diagnosis and motherhood.

Overall, being diagnosed with HIV brought about mixed feelings intimately related to protecting their children and fulfilling their roles as mothers. Participants grieved after their diagnoses and at times isolated themselves with their children.

Two participants said that they were sad about not being able to complete certain behaviors associated with motherhood; one of which was not being able to breastfeed her child, a medical recommendation to prevent perinatal transmission. For Rosa, breastfeeding was symbolically tied to being a mother, and, therefore, she felt incomplete or was a bad version of a mother, despite her child’s health and growth suggesting otherwise.

It gives me sorrow. They tell me he (my child) has a good weight, that he has a good height, that he is overall healthy, but upon seeing other mothers breastfeeding their children, and knowing that I can’t. I have to use a feeding bottle. Sometimes, it gives me a lot of sorrow.

(Rosa, 36)

One mother, however, remained positive despite her inability to breastfeed, an act she also associated with motherhood. This mother was able to reframe bottle feeding as part of life for an independent, working woman, effectively removing the stigma attached to it.

It’s almost like a person who has to work and cannot breastfeed because of it, because she works. In other words, I always try to think of the positive, and not the negative, because sometimes I do. But with this baby, I cannot get depressed. For me that’s it, and I can’t let it hurt me.

(Lucy, 23)

A particularly powerful theme surfaced among six women about the uncertainty they felt about their children acquiring HIV and the potential consequences that it would have on their lives. This uncertainty, especially in the two cases in which mothers passed the virus to their children, included feelings of guilt for having infected their children, sadness for not being able to explain to their children the circumstances they lived with, and fear of their children experiencing discrimination.

… (My child) did not have a negative result or a positive one, nothing, nothing, it didn’t give any results, and they had to do it again. She asked me, “Why are they taking out my blood?” “No,” I told her, “they are only doing it for your cough my darling.” But when they told me no about my youngest and yes about her, I experienced an unbearable pain. I cried and I became very depressed.

(Andrea, 25)

For Romina, a woman who learned of her diagnosis after the birth of her child and after the virus had already been passed to her daughter, frustration and anxiety led to more intense feelings of guilt and impotence.

(There are days that) I see my little girl, and I ask, “Why God? Why did we have to go through this”? It comes to me like this, from one time to another, this idea comes to me, and I simply say, “God, I leave this with you,” as if somebody had said it. I say, “Please father help us, do not abandon us citizens,” I tell him, “with this illness that has appeared to us.”

(Romina, 36)

For many women, seeking faith in God and reinforcing their belief in a larger, divine plan or destiny eased their pain during its most intense moments.

Family and partner relationships.

Once the initial shock of the diagnosis settled in, participants’ family members and partners elicited a wide array of emotions in the women, often presenting as sources of anguish or inspiration. Some women shared the devastatingly personal impacts that the virus had on their lives, even leading to the breakdown of family ties. Identified emotions included mistrust and abuse, as well as adaptation, inspiration, love, and deep appreciation. It was common for participants to manifest all of these emotions over various stages of their emotional recovery.

Four women for whom family support was lacking, when partners or families showed indifference toward the illness and did not provide support to push forward, conveyed feelings of loneliness and emotional abandonment. “[I told them that I had cancer, and] they didn’t even come, not even if I asked for just a can of milk. What would you have done if you wanted to eat?” (Selma, 26)

[My husband isn’t mature] and isn’t about what has happened to us either, just as the head of a household should be, right? A father of a family is more dedicated to his children, works for his children, for the wellbeing of the family, but he … even when I was hospitalized this week, he didn’t even want to come near the hospital. And why not? I could have died, and he doesn’t even have the decency to come visit me or even care about money. When a man worries about his woman and when the woman about the man, it works! … I have lived 4 years with him. He says he will change, he will change, but after a month he goes back to what it was; back to the same.

(María, 22)

Three women felt stigma from their families. This included families expressing stigma because participants had HIV and because they were afraid about becoming infected, although the fear was often not merited.

For example, even with earrings. One day I put on my sister’s earring, which the doctor said would transmit the disease, with the earring when you put it on. But … I asked a nurse and she told me that you couldn’t transmit the disease with earrings, right? … My ear is dry, and has had a hole in it for many years, no? I told her, but she is how she is, no? She has that fear. I saw well then that’s that. Sometimes it impacts me, no? It exists because of this disease, even to the point that they are disgusted by me, no?

(Maŕıa, 22)

Two participants rejected their partners for infidelity and lack of trust. In the case of Esme, rejection was amplified by the fact that some of her children were infected. As a mother, Esme was angry about the challenges that her children with HIV would have to face because of the perceived irresponsibility of her partner.

Yes, I said to him. “Now, I have paid for everything that you have done to me,” and I humiliated him. I told him, “Devil! You have AIDS! You are sick!” I insulted him, “Go off with your bitch! That girl that also has AIDS! … One day you will know the truth, I tell my little boy,” and he tells me, “What are you telling my child, don’t tell him those things.” Yes, I am going to do what he hates. I am going to take revenge on all that he has done to me. He always cries, cries, and cries, and only drinks, nothing more.

(Esme, 24)

Some of the participants had conflicted feelings toward their partners. The example below from Andrea shows that she considered her partner and her illness part of her destiny, a destiny that also included the blessings of her children. Ultimately, Andrea accepted her partner because she was able to have children with him, and this series of events was part of her religious journey within what she considered God’s plan for her.

But, Miss, if it was his fault, what am I going to do? I can’t blame him or myself. I will only say that there is one God. I can’t recognize why my partner is the father of my children, but God calls upon us. God calls upon us, and what are we supposed to do?”

(Andrea, 25)

Most women’s feelings toward their partners moved toward compassion, even if they were unable to forgive the partners completely. Reinforcing their faith allowed many women to transcend negative emotions such as anger, impotence, and fear.

Transformation and transcendence: Overcoming the emotional burden of HIV.

With the passage of time, between diagnosis and study interview, seven participants presented with a positive and sequential transition to feelings of acceptance, adaptation, and self-motivation about the disease and/or treatment. Although the time with diagnosis and circumstances varied, the majority of women ultimately achieved emotional stability, and many manifested feelings of transcendence and personal growth.

(The illness is) there for better or for worse … because I carry on, nothing more. It isn’t because I have it (HIV), no … my thoughts are the same, I carry on, nothing more. Nothing has changed in a bad way, in a bad way, no. For the better, actually, I have made myself stronger, I live at peace.

(Lucy, 23)

A surprising theme that arose in three women was a positive change and/or positive outcomes from having received an HIV diagnosis. With this outlook, they showed maturity in trying to make their relationships with their partners or families more united.

For my family, it has never mattered whether I had it or not. It’s always the same and continues that way (clears her throat). In fact, our communication has actually gotten better. It has, how would I say this, brought something good, you know? We have become more united as a family. Yes.

(María, 22)

After accepting their HIV status, seven participants no longer considered HIV to be a negative factor in their lives, which included comments such as “there is no point in blaming anybody” (Lucy, 23) and “I no longer feel ashamed of myself” (Esme, 24). At the same time, participants were cognizant of the stigma they experienced and attributed it to the ignorance that others had about the disease.

If they show discrimination toward me, it wouldn’t change anything. It wouldn’t change anything because if they discriminate against me, if they know my HIV status, the thing is no … no, I wouldn’t harm anybody, and I wouldn’t affect anybody. If they discriminate, it is only because of their ignorance.

(Andrea, 25)

Many attributed this change to strength they found in their love and commitment to their children. They were able to effectively use this strength to overcome sadness, fear, and anger. “(At first) I cried and cried because I didn’t know what to do. But, over time, I began adjusting, for my children, and for my mother too, but mostly because of my kids, for my kids” (María, 22).

Six of the eight women were able to channel emotional strength from their children, families, and environment. Five women reported receiving emotional or economic support from their immediate families, including from their children.

Yes, sometimes my husband when he is here, or even my little girl, say, “Take it so that you get better. Take it and do not throw it up.” My little girl motivates me. She tells me, “Take it mom so that you can get better and we can go out for a walk ….” She tells me, “The pills mom! The pills … quickly, quickly!” And she brings me water, “Ok darling.” And now that my husband isn’t here, “Dad has brought your pills?” “Yes darling.” “And when he arrives you will have taken your pills?” “Yes darling, yes.” and so on and so forth. She worries about me, my amazing little child ….

(Andrea, 25)

Some women found motivation in offering a better future for their children. In particular, the women learned how to reformulate their fears and worries into positive forces that gave them strength to take care of themselves, continue with their treatment, and not get depressed. “I am going to push onwards, for my life, but more for my children, because my children are who give me meaning in life” (Andrea, 25). In six cases, participants mentioned feeling motivated to care for themselves, so their children or family would not be left without their source of support.

If God allows me … (until I arrive to the moment of my death) … (I hope) to leave my daughter with something good: with her little room, with her little things … Whatever I couldn’t give her before, I want to give her now.

(Patricia, 26)

Participants cited the positive emotions derived from these relationships as feeling motivated to continue treatment, a determination that the illness would not take control of their lives, and a desire to continue living as before.

… It is my own decision to get healthy. Sometimes, I tell myself that and it makes me stronger. In front of my father and mother, I tell them that they are my ideas to be well. I know that I am going to get healthy. I am going to get up and do something whether it be buying a food cart to sell food, or buying a plot of land, even if it is just for a house made out of clay. That’s how we will be.

(Andrea, 25)

In some situations, it was just as important to give support to the family as it was to receive it. Seven interviews highlighted how maternal instincts to care for their families, despite the burden of disease, served as a mechanism of motivation. The family’s mere presence gave participants purpose and allowed them to focus on what mattered most to them.

… I couldn’t blame him [husband] because he would feel bad. He is very good to me, and I’m not going to tell him that he is guilty because he could get depressed, and lower his defenses to the sickness. Now, I think about those things much more, as much for him and my little daughter.

(Romina, 36)

In a particularly illustrative case, Patricia was the only participant interviewed who continued to feel significant shame. However, like other participants, her dedication toward her children served as a mechanism of resilience. It is important to highlight that, in this case, Patricia received her diagnosis only 6 months before the interview, which was shorter than the majority of the cohort. Although she claimed to have a long way to go in recovering emotionally, it was her role as a mother that helped her find solace.

(After the diagnosis) I couldn’t even leave (my house) in shame towards others. Now, I dedicate myself to my children. (I thought of) getting out of my house, (participant sobs) … I couldn’t bear to have others see my child with me. I thought my life was over and didn’t have a solution.

(Patricia, 26)

Within their environments, the women illustrated abilities to extend emotional support to their peers with HIV, while simultaneously continuing their own emotional recoveries. La casa hogar (a home for battered women) and the hospital waiting room (where women decompressed after receiving an HIV diagnosis) emerged as places that were invaluable for emotional development. In the hospital, one of the women was able to take advantage of the space to connect with other individuals and thereby create a new support network where she could simultaneously provide support and share her own experiences, a process which was at once therapeutic to her and to others.

Sometime, for example, I have made many friends in the same hospital. This includes all of us going to a house; we go on Wednesdays … every Wednesday … Therefore, it is there that they help people with a diagnosis, including those cases with babies as well. In other words, the babies can be positive or negative, and they help them, you know?”

(María, 22)

Many wanted to dedicate themselves to expanding public knowledge of HIV, and five of the women wanted to help PLWH overcome the difficulties that they had faced. “I give advice to others, but not by telling them that I am ill. Right now, with the girl that I see, I speak to, [I say] ‘Take your pill, your treatment, for your little boy, always’” (Selma, 26). Support to other women was part of the recovery process and provided meaning and strength to the women who provided the support.

Discussion

In our cohort of eight women living in poverty and with HIV, we intended to connect emotions to action and emphasized the mother’s own role in her emotional recovery. Although various studies have discussed the emotions of PLWH, a few of them have investigated the emotional experiences of mothers with HIV, and even fewer have explored the role of the mother in her own emotional recovery (Fords et al., 2017; Withell, 2000). No studies in Peru have explored the experiences of mothers living with HIV.

The findings from our study were consistent with studies in which mothers with HIV manifested emotions symptomatic of depression, such as anguish, guilt, chronic sadness, and feelings of isolation, particularly during the early time after diagnosis (Demmer, 2010; Fords et al., 2017; Hejoaka, 2009; Murphy, Marelich, Armistead, Herbeck, & Payne, 2010; Nelms, 2005). For the women in our study, the diagnosis was interpreted as if it were a terminal illness, and their initial reactions were either denial or profound sadness and hopelessness. Being diagnosed during a routine pregnancy test without being symptomatic may have increased the shock associated with the diagnosis. This has also been discussed in the literature (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018).

The findings from our study were consistent with those from other studies that suggest that mothers with HIV fear discrimination and feel a considerable emotional burden when revealing the diagnosis to family (Madiba, 2012; Nelms, 2005). Women in our study grappled with their own fears and the need for support; many ultimately reached out to family to seek hope, motivation, and inspiration to continue. Our study found that five participants eventually received family support, with most emotional support derived from their immediate environments. This was consistent with our previous study, which found that women with HIV shared their diagnoses with their families and ultimately received material and emotional support (Waters et al., 2017).

The inability to fulfill certain aspects of motherhood was a principal source of worry for our mothers: Examples of this included being unable to breastfeed their children and uncertainty about supporting their children in the future. Research corroborated these results with findings that intense feelings of worry returned in future postdiagnosis pregnancies (Sanders, 2008). We add to the existing literature by demonstrating concrete ways in which mothers living with HIV successfully reframed their roles as mothers from one characterized by lacking and fault to one characterized by love, support, and independence.

New findings from our study show how mothers artfully orchestrated relationships to obtain the emotional support they needed. Some channeled love and dedication for their children, even when very young, into strength to overcome negative emotions. During intense periods of emotional pain, the mothers protected themselves and their children by seeking isolation and retrospection. Many of the mothers shared concrete information about HIV with their families, thereby directing the families’ reactions toward acceptance and providing practical emotional support.

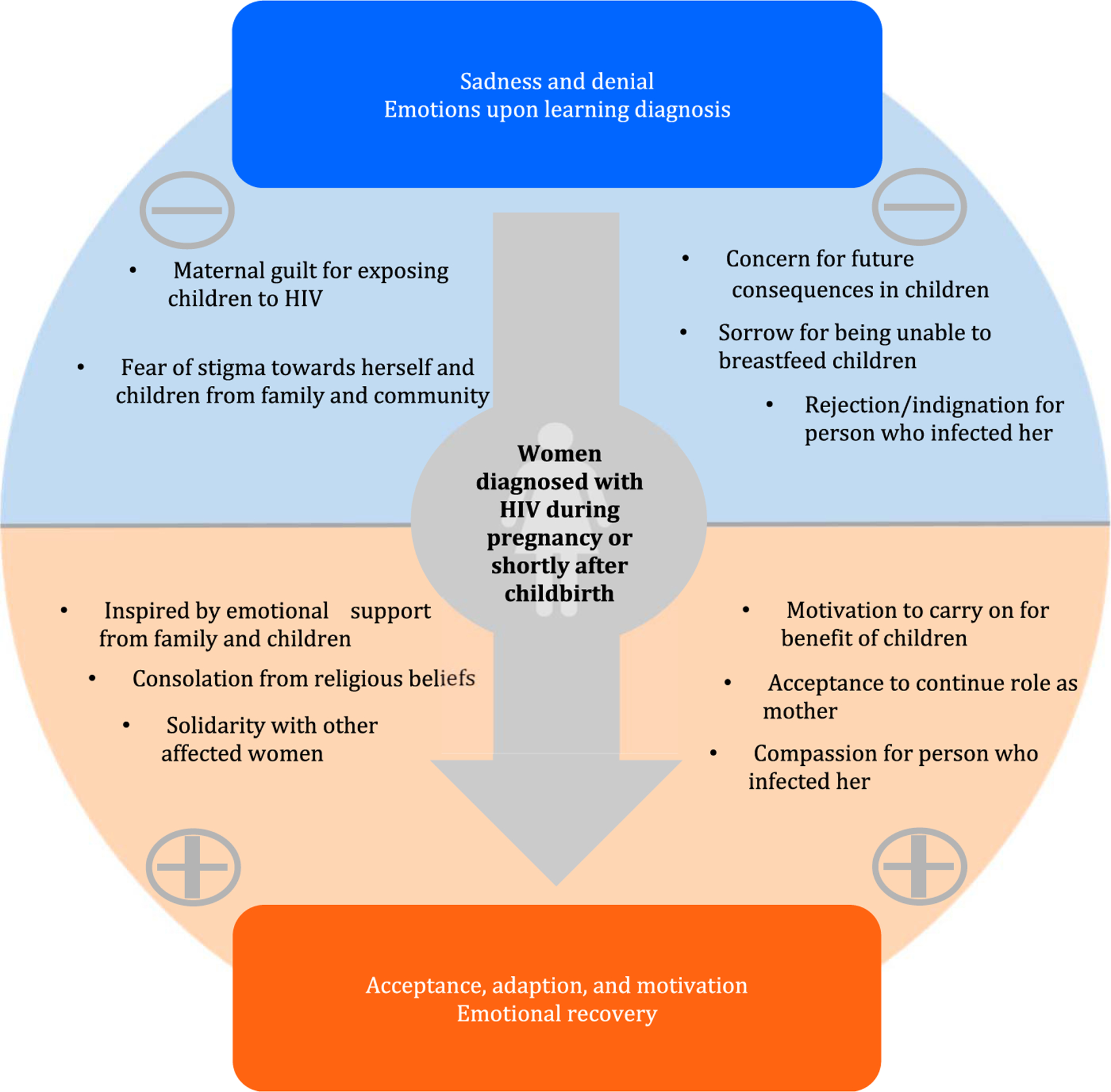

With the exception of one woman in our study, all participants were able to create their own emotional transformation; it began with fear and sadness associated with the certainty of death and transitioned to acceptance, adaptation, and feelings of transcendence. Intense emotions brought about by the illness not only led mothers to accept the illness but also often put them on a path to become stronger, take active roles in their lives, and collaborate with women in similar situations. A key part of this was a sense of hope brought about by cultivating love for their children and being able to see them grow into healthy adults. Women have described this transformation in terms of personal growth, even demonstrating gratitude for changes in their lives resulting from the challenges they faced from the illness (Castro, Khawja, & González-Núuñez, 2007). Figure 1 describes our primary contribution to the literature, which involves the process of transformation from diagnosis to recovery. Mothers living with HIV achieve emotional recovery through experiences related to receiving and sharing the diagnosis, relationships with their partners and families, and self-identified mechanisms of resilience. Some experiences provoke negative emotions (−), such as depression and denial. Others elicit positive emotions (+) such as acceptance, adaptation, and motivation. Although influenced by families and communities, the mothers were the principal agents in interpreting their experiences and overcoming the emotional burden of HIV.

Figure 1.

Emotional recovery of women diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy or postpartum period.

Limitations

Our study had certain limitations. Our cohort only provided information during the start of ART, which meant that conversations could not explore the ways in which emotions changed over the long term. Variations in the cohort were related to the time since HIV diagnosis; some women had started ART irregularly, which made our cohort very diverse and could have impacted the intensity and memory recall of their emotions (such as the denial of the illness). To avoid this bias, our analysis took into account the amount of time that had passed from the diagnosis and did not compare relative intensities of emotions.

Conclusion

As ART becomes more available and HIV management is accepted as a chronic disease, it is important for caregivers who are involved in long-term care to understand the emotional processes women with children are likely to experience. Based on evidence from our study, we recommend training health personnel in emotional support, which may help mothers more readily tap into their own sources of strength and personal growth. Health professionals should initially empathize with a patient’s intense emotions, rather than hastily seeking solutions, because these data suggest that the emotions themselves aid in motivating recovery.

Several studies have found that HIV peer counseling can be an effective tool to provide emotional stability and hope, and it can also result in better treatment adherence and outcomes (Abdulrahman et al., 2007; Harris, & Larsen, 2007; Kellett, & Gnauck, 2016; van Luenen et al., 2017). Community-based interventions that incorporate patient support groups have shown promise in improving ART adherence and viral suppression (Muñoz et al., 2011). In the future, more formal mechanisms for women with HIV to support each other could have significant impact on the emotional recovery of the whole group. Formal and informal support groups, such as those led by peers, particularly in low-resource settings, could be powerful tools to increase the emotional well-being of mothers living with HIV and have far-reaching impact in improving partner notification, uptake of ART, and HIV vertical transmission.

Key Considerations.

Mothers diagnosed with HIV during or after pregnancy experience a unique set of emotional challenges to which health care professionals should be sensitive.

Emotional challenges are different for each mother; however, they can be described in terms of predictable stages of recovery and many experiences are shared, such as regret and guilt for not being able to breastfeed.

Mothers with HIV carry tools, which, if encouraged by their families and health care providers, can be put to use to overcome the emotional burden of daily life with HIV.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Socios En Salud team who contributed to this project. Additionally, we would like to thank the community health workers, patients, and their families for their participation in the CASA study. We are incredibly grateful for the Lima health center personnel who aided in the study and the Peruvian Ministry of Health for their help in the execution of this project. Finally, we would like to extend our sincerest thanks to those who graciously offered their time to transcribe interviews. This study was made possible by the NIMH R01 grant #1-R01-MH83550-01A2 (PI: Sonya Shin).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests related to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

References

- Abdulrahman SA, Rampal L, Ibrahim F, Radhakrishnan AP, Shahar HK, & Othman N (2017). Mobil phone reminders and peer counseling improve adherence and treatment outcomes of patients on ART in Malaysia: A randomized clinical trial. Plos One, 12(5), e0177698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, (2018). Pregnancy book: Your pregnancy and childbirth, month to month (6th ed.). Retrieved from https://www.acog.org/Patients/ACOG-Pregnancy-Book [Google Scholar]

- Ashaba S, Kaida A, Burns BF, O’Neil K, Dunkley E, Psaros C, … Matthews LT (2017). Understanding coping strategies during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A qualitative study of women living with HIV in rural Uganda. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 138. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1321-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy E, Reynolds F, Naylor S, & De Souza L (2011). Using interpretative phenomenological analysis to inform physiotherapy practice: An introduction with reference to the lived experience of cerebellar ataxia. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 27(4), 263–277. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2010.488278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro A, Khawja Y, & González-Núñez I (2007). Sexuality, reproduction, and HIV in women: The impact of ART in elective pregnancies in Cuba. AIDS, 21(S5), S49–S54. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298103.02356.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro A, & Sandesara U (2009). Integration of prenatal care with the testing and treatment of HIV and syphilis in Peru. Retrieved from https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/2009_Prenatal_Care_HIV_and_Syphilis_in_Peru.pdf

- Demmer C (2010). Experiences of women who have lost young children to AIDS in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: A qualitative study. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 13(1), 50. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fords GM, Crowley T, & van der Merwe AS (2017). The lived experiences of rural women diagnosed with the human immunodeficiency virus in the antenatal period. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 14(1), 85–92. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2017.1379430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GE, & Larsen D (2007). HIV peer counseling and the development of hope: Perspectives from peer counselors and peer counseling recipients. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21(11), 843–860. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebling EM, & Hardy E (2007). Feelings related to motherhood among women living with HIV in Brazil: A qualitative study. AIDS Care, 19(9), 1095–1100. doi: 10.1080/09540120701294294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejoaka F (2009). Care and secrecy: Being a mother of children living with HIV in Burkina Faso. Social Science & Medicine, 69(6), 869–876. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2014). People living with HIV: The Gap Report. Retrieved from http://files.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf

- Kellett NC, & Gnauck K (2016). The intersection of antiretroviral therapy, peer support programmes, and economic empowerment with HIV stigma among HIV-positive women in West Nile Uganda. African Journal of AIDS Research, 15(4), 341–348. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2016.1241288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotzá M, Visser M, Makin J, Sikkema K, & Forsyth B (2013). The coping strategies used over a two-year period by HIV-positive women who had been diagnosed during pregnancy. AIDS Care, 25(6), 695–701. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.772277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Moral JM, Piscoya-Angeles P, Edwards JE & Palmieri PA (2017). The experience of pregnancy in women living with HIV: A meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 28(4), 587–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madiba S (2012). The impact of fear, secrecy, and stigma on parental disclosure of HIV status to children: A qualitative exploration with HIV positive parents attending an ART clinic in South Africa. Global Journal of Health Science, 5(2), 49. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n2p49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martz E, & Livneh H (Eds.). (2007). Coping with chronic illness and disability:Theoretical, empirical, and clinical aspects. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz M, Bayona J, Sanchez E, Arevalo J, Sebastian JL, Arteaga F … Shin S (2011). Matching social support to individual needs: A community-based intervention to improve HIV treatment adherence in a resource-poor setting. AIDS and Behavior, 15(7), 1454–1464. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9697-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Armistead L, Herbeck DM, & Payne DL (2010). Anxiety/stress among mothers living with HIV: Effects on parenting skills and child outcomes. AIDS Care, 22(12), 1449–1458. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.487085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms TP (2005). Burden: The phenomenon of mothering with HIV. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 16(4), 3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PM, Merriam SB, & Courtenay BC (1999). Adaptation to HIV infection: The development of coping strategies over time. Qualitative Health Research, 9(3). doi: 10.1177/104973299129121901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LB (2008). Women’s voices: The lived experience of pregnancy and motherhood after diagnosis with HIV. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 19(1), 47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Munoz M, Caldas A, Ying W, Zeladita J, Wong M … Bayona J (2011a). Mental health burden among impoverished HIV-positive patients in Peru. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, 10(1), 18–25. doi: 10.1177/1545109710385120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Munoz M, Zeladita J, Slavin S, Caldas A, Sanchez E … Bayona J (2011b). How does directly observed therapy work? The mechanisms and impact of a comprehensive directly observed therapy intervention of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Peru. Health & Social Care in the Community, 19(3), 261–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00968.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology & Health, 11, 261–271. doi: 10.1080/08870449608400256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Flowers P, & Larkin M (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR (Ed.). (1999). Coping: The psychology of what works. New York, NY: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Trocmé N, Courcoux MF, Tabone MD, Leverger G, & Dollfus C (2013). Impact of maternal HIV status on family constructions and the infant’s relational environment during the perinatal period. Archives de Pediatrie, 20(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. (2018). Peru: Overview. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/peru

- van Luenen S, Garnefski N, Spinhoven P, Spaan P, Dusseldorp E, & Kraaij V (2017). The benefits of psychosocial interventions for mental health in people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 22(1), 9–42. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1757-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters C, Wong M, Nelson AK, SantaCruz J, Beeson A, Pfeiffer J … Shin S (2017). From HIV diagnosis to initiation of treatment: Social transformation among people starting antiretroviral therapy in Peru. Qualitative Social Work, 16(1), 113–130. doi: 10.1177/1473325015597996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withell B (2000). A study of the experiences of women living with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 6(5), 234–244. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2000.6.5.8925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2018). HIV/AIDS key facts. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids