Given the success of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing death and severe disease in adults1 and their impact on community transmission,2 use in children and young people (CYP) inevitably requires consideration. Although severe COVID-19 is rare in CYP,3 they are affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including education, mental health, and general wellbeing.4

As of late July, 2021, no COVID-19 vaccine is recommended for children younger than 12 years and safety and efficacy data from phase 3 clinical trials are so far limited: 1131 CYP aged 12–15 years received the Pfizer–BioNTech mRNA vaccine5 and safety data are available from phase 1 and 2 trials of Sinovac's inactivated CoronaVac vaccine in 438 children aged 3–17 years.6 Safety data have been reassuring, with published data confirming excellent immunogenicity.5 There is no reason to believe the vaccines should not be equally protective against COVID-19 in CYP as they are in adults. More than 30 international trials are now recruiting CYP as young as 6 months to assess safety, immunogenicity, dosing, and scheduling questions.7 Safety data from the Pfizer–BioNTech mRNA vaccine trial proved sufficient for regulatory authorities in the EU, Israel, and North America to issue approval for use of this vaccine in CYP aged 12–15 years. Safety data from the real-life roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines are continuously collected through surveillance systems in high-income countries (HICs)8, 9 and are generally reassuring, although a rare vaccine-associated signal of transient inflammation of the heart muscle in some young adults has raised concerns.10 On balance, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that benefits outweigh the risks.11

Countries are also still calculating what indirect benefits for reduced SARS-CoV-2 transmission in schools and the wider community could be achieved by vaccinating CYP. With children now recognised as part of the chains of community transmission,4 the discussion about a CYP vaccine programme was perhaps inescapable. Yet the impacts of COVID-19 vaccination in CYP on transmission dynamics will vary nationally, since epidemiological circumstances, novel SARS-CoV-2 variants, and contact mitigation strategies will have different roles in different places.

Most countries have yet to decide whether to include CYP in COVID-19 vaccination programmes. Canada, Israel, some European countries, and the USA have introduced the vaccine for all young people older than 12 years. By contrast, countries such as Germany and the UK are focusing on groups most at risk of severe COVID-19, but are not universally rolling out COVID-19 vaccination to CYP older than 12 years.12

Unsurprisingly, low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) have not yet introduced COVID-19 vaccines for CYP. WHO guidance from July 14, 2021, states: “Children and adolescents tend to have milder disease compared to adults, so unless they are part of a group at higher risk of severe COVID-19, it is less urgent to vaccinate them than older people, those with chronic health conditions and health workers…WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) has concluded that the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine is suitable for use by people aged 12 years and above. Children aged between 12 and 15 who are at high risk may be offered this vaccine alongside other priority groups for vaccination. Vaccine trials for children are ongoing and WHO will update its recommendations when the evidence or epidemiological situation warrants a change in policy.”13

Further data from LMICs will aid risk assessments of SARS-CoV-2 in CYP, both for personal health and transmission roles. A recent meta-analysis indicated that the outcome of children admitted to hospital with acute COVID-19 is worse in LMICs than in HICs (case fatality rates 0·29% [95% CI 0·28–0·31%] vs 0·03% [0·03–0·03%]).14 Vaccinating CYP in LMICs may ultimately have more benefit to their health status compared with CYP in HICs.

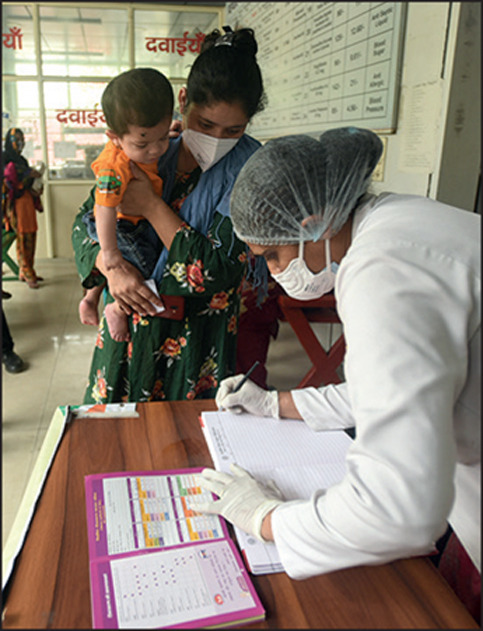

© 2021 Hindustan Times/Getty Images

All vaccines should be given to those who need them most, particularly in the context of a pandemic with limited vaccine supply. Of the more than 4 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines administered globally in the past 8 months, less than 2% have been given in Africa;15 on a continent that cannot vaccinate its most vulnerable populations (eg, older people and those with chronic conditions) and highly exposed health-care workers, introducing vaccines for CYP remains a luxury. This gross inequity prevents LMICs from not only preventing death and serious illness, but also from deploying vaccines as tools to interrupt SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The inclusion of CYP will not be a priority in LMICs for a long time because of the serious shortfalls of vaccines.

What of the WHO motto that “No one is safe till everyone is safe”? HICs have unlimited stocks of COVID-19 vaccines.16 If a key reason for the use of the COVID-19 vaccines in CYP in HICs is reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission, surely CYP in LMICs should also be vaccinated? We are far from the vision of the African Union (AU) to vaccinate two-thirds of its members' population. In addition to COVAX, the AU has now partnered with additional vaccine suppliers through the AU's African Vaccine Acquisition Trust, including UNICEF.17 However, even vaccinating 66% of individuals is unlikely to be sufficient to interrupt transmission chains.

In addition to supply issues and logistics that prevent the use of COVID-19 vaccines in CYP in LMICs, the success of any plans to roll out the vaccines must also ride on the back of acceptance and confidence. Parents in LMICs need reassurance they are doing the right thing for their children, just as has been found in HICs.18

During deliberations on the potential benefits of COVID-19 vaccines for CYP, it is important to recognise that this pandemic has already deprived more than 8 million children, primarily in LMICs, from life-saving, routine childhood vaccines.19 Immunisation services are preoccupied with the implementation of COVID-19 vaccine programmes for adults. At present, greater benefit for children's health globally will be derived by delivering the health interventions we already know will save their lives, such as vaccines against measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases, than by focusing on delivering COVID-19 vaccines to part of a population that does not currently represent a strategic priority in the response to this pandemic. Although maybe not equitable, we believe this approach is more important for the health of CYP at this point in time.

Acknowledgments

BK has received institutional grants from Pfizer for a maternal immunisation study unrelated to COVID-19; and received personal fees for services to a Data and Safety Monitoring Board from Johnson & Johnson for a COVID-19 vaccine study and for scientific advisory boards from Pfizer, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline for non-COVID-19-related vaccines for use in pregnancy. UO declares no competing interests.

References

- 1.Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397:1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris RJ, Hall JA, Zaidi A, et al. Effect of vaccination on household transmission of SARS-CoV2 in England. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2107717. published online June 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irfan O, Muttalib F, Tang K, et al. Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes of paediatric COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:440–448. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ismail SA, Saliba V, Bernal JL, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission in educational settings: a prospective, cross-sectional analysis of infection clusters and outbreaks in England. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:344–353. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frenck RW, Jr, Klein NP, Kitchin N, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han B, Song Y, Li C, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in healthy children and adolescents: a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00319-4. published online June 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine LSHTM Vaccine Tracker. 2021. https://vac-lshtm.shinyapps.io/ncov_vaccine_landscape/

- 8.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency MHRA Coronavirus Yellow Card reporting. 2021. https://coronavirus-yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk

- 9.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/vaers/index.html

- 10.Montgomery J, Ryan M, Engler R, et al. Myocarditis following immunization with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in members of the US military. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2833. published online June 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gargano JW, Wallace M, Hadler SC, et al. Use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine after reports of myocarditis among vaccine recipients: update from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:977–982. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7027e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Public Health England JCVI issues advice on COVID-19 vaccination of children and young people. July 19, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/jcvi-issues-advice-on-covid-19-vaccination-of-children-and-young-people

- 13.WHO COVID-19 advice for the public: getting vaccinated. July 14, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/advice

- 14.Kitano T, Kitano M, Krueger C, et al. The differential impact of pediatric COVID-19 between high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of fatality and ICU admission in children worldwide. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.African Union COVID-19 vaccination—latest updates from Africa CDC on progress made in COVID-19 vaccinations on the continent. 2021. https://africacdc.org/covid-19-vaccination/

- 16.Wouters O J, Shadlen K C, Salcher-Konrad M, et al. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UNICEF The African Union's African Vaccine Acquisition Trust (AVAT) initiative. 2021. https://www.unicef.org/supply/african-unions-african-vaccine-acquisition-trust-avat-initiative

- 18.Bell S, Clarke R, Mounier-Jack S, et al. Parents' and guardians' views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. 2020;38:7789–7798. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Causey K, Fullman N, Sorensen RJD, et al. Estimating global and regional disruptions to routine childhood vaccine coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01337-4. published online July 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]